Stockholm Resilience Centre

Sustainability Science for Biosphere Stewardship

Master’s Thesis, 60 ECTS

Social-ecological Resilience for Sustainable Development

Master’s programme 2019/21, 120 ECTS

Coming back to our senses:

Exploring the potential of guided forest bathing

as an intervention for human-nature connection

Annelie Vårhammar

“The land is the real teacher. All we need as students is mindfulness.

Paying attention is a form of reciprocity with the living world,

receiving the gifts with open eyes and open heart.”

― Robin Wall Kimmerer

2

ABSTRACT

Fostering human-nature connection (HNC) relates to the inner worlds of humans as a realm of

influence for sustainability and is considered a deep leverage point for system transformation.

Both direct nature experiences and states of mindfulness are significant for influencing the

development of HNC. Therefore, in this thesis, I explore the potential of guided forest bathing

– an originally Japanese practice of mindfully immersing one’s senses in the atmosphere of a

forest – as an intervention for HNC. I do so by applying a mixed methods approach and a

relational, multidimensional assessment of the qualities and effects of a guided forest bathing

session, as conducted in the methodology of the Scandinavian Nature and Forest Therapy

Institute. While not able to establish causality, the study results suggest that participation in

just one guided forest bathing session may positively influence the development of HNC,

primarily in participants new to the experience. The results also suggest that several qualities

of guided forest bating are important for influencing HNC, including mindfulness,

engagement of senses, and self-restoration. These qualities and others related to the specific

structure and social setting of the experience can provoke thoughts that meaningfully shift

how individuals perceive and interact with nature. This leads the thesis to conclude that

guided forest bathing represents a novel nature experience with promising potential as an

intervention for HNC.

Keywords:

Human-nature connection, guided forest bathing, assessment, mindfulness in nature,

interventions, sustainability transformation, deep leverage point

Main thesis supervisor:

Matteo Giusti, Gävle University

Thesis co-supervisors:

Vanessa Masterson, Stockholm Resilience Center,

Petra Ellora Cau Wetterholm, Scandinavian Nature and Forest Therapy

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express huge gratitude to all the study participants who answered the two online

surveys and especially to those who took the time to be interviewed. Your eloquent, rich

responses to my interview questions and your admirable openness about your thoughts and

experiences are what gave additional life and richness to this thesis.

Many persons contributed greatly to making this thesis project possible. A massive thanks to

my external supervisor and collaborator Petra Ellora Cau Wetterholm for the support, long

discussions and for granting me access to the SNFTI methodology, internal network of

guides, and your immense wisdom about guided forest bathing. A particular thank you to the

ten amazing forest bathing guides who joined the study and made data collection possible:

o Petra Ellora Cau Wetterholm, Scandinavian Nature & Forest Therapy Institute and

Shinrin-Yoku Sweden, https://www.scandinaviannatureandforesttherapyinstitute.com/

o Annette Öhrn, SaktaIn, http://www.saktain.se

o Kerstin Ulbing Ponnert, Shinrin-Yoku Lund/Ängelholm

o Kristina Olsson, Gröna samtal, http://gronasamtal.se/

o Lotta Ihse, Urban Balance club, http://www.urbanbalanceclub.se

o Margit Melin, Melins Ord, http://www.melinsord.se

o Maria Moody Källberg, Nätverkskompaniet MMK AB Skogsvaro,

https://natverkskompaniet.se/skogsvaro/

o Marie Rosén, NaturStark AB, https://www.naturstark.se/

o Peter Amling, MindChange, https://www.facebook.com/mindchangesweden/

o Susanna Bävertoft, True by You, https://truebyyou.se/

Of course, a warm thank you to my supervisors Matteo Giusti at Gävle University and

Vanessa Masterson at Stockholm Resilience Center for believing in me and this thesis idea.

You both provided invaluable feedback and support, particularly when we were faced with

having to pause the thesis due to the COVID-19 pandemic and then quickly recoup a few

months later. Last but not least, I want to say thank you to my thesis group classmates for the

feedback and encouragement in the writing process, and to my beloved friends and family for

cheering me on.

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 8

1.1. Research questions ................................................................................................................ 10

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK................................................................................................. 11

2.1. Human-Nature Connection (HNC)........................................................................................ 11

2.1.1. ACHUNAS – An embodied approach to human-nature connection............................. 11

2.1.2. New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) .................................................................................. 12

2.2. Mindfulness and sustainability .............................................................................................. 13

2.2.1. Mindfulness and HNC ................................................................................................... 14

2.2.2. Mindfulness in nature and HNC .................................................................................... 14

2.3. Forest Bathing ....................................................................................................................... 15

2.3.1. Origin............................................................................................................................. 15

2.3.2. Guided forest bathing in the West ................................................................................. 15

2.3.3. Guided forest bathing and mindfulness ......................................................................... 16

2.3.4. Guided forest bathing and HNC .................................................................................... 16

3. METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 18

3.1. Ontological position .............................................................................................................. 18

3.2. Mixed-methods research design ............................................................................................ 18

3.3. Guided forest bathing sessions .............................................................................................. 18

3.4. Quantitative surveys .............................................................................................................. 20

3.4.1. Participant selection method.......................................................................................... 20

3.4.2. Data collection procedure.............................................................................................. 20

3.4.3. Survey measures ............................................................................................................ 21

3.4.4. Quantitative data analysis.............................................................................................. 23

3.5. Qualitative semi-structured interviews.................................................................................. 23

3.5.1. Sampling and data collection procedure........................................................................ 23

3.5.2. Qualitative analysis strategy .......................................................................................... 23

4. RESULTS...................................................................................................................................... 25

4.1. Descriptive and statistical survey results............................................................................... 25

4.1.1. Sample description ........................................................................................................ 25

4.1.2. Validity and reliability of ACHUNAS .......................................................................... 25

4.1.3. HNC scores.................................................................................................................... 25

4.1.4. NEP scores .................................................................................................................... 26

4.1.5. Qualities of SNS ............................................................................................................ 26

4.2. Explanatory insights from interviews.................................................................................... 27

4.2.1. Guided forest bathing as significant nature situation .................................................... 27

4.2.2. Thought provocations .................................................................................................... 30

5

4.2.3. Negative aspects ............................................................................................................ 34

5. DISCUSSION ............................................................................................................................... 36

5.1. Effect of guided forest bathing on HNC................................................................................ 36

5.2. Qualities of guided forest bathing influencing HNC ............................................................. 37

5.3. Assessing the influence of nature experiences ...................................................................... 38

5.4. Methodological reflections and future directions .................................................................. 38

5.5. Implications of study ............................................................................................................. 39

6. CONCLUSIONS ........................................................................................................................... 41

7. REFERENCES .............................................................................................................................. 42

8. APPENDICIES ............................................................................................................................. 46

8.1. Appendix 1: Plain language statement .................................................................................. 46

8.2. Appendix 2: Consent form .................................................................................................... 47

8.3. Appendix 3: Interview guide ................................................................................................. 48

8.4. Appendix 4: Summary of subthemes for each quality of SNS .............................................. 49

8.5. Appendix 5: Note on methodology ....................................................................................... 53

8.6. Appendix 6: Ethical review – final review............................................................................ 54

6

LIST OF TABLES & FIGURES

TABLE 1 | The 16 qualities of significant nature situations in the ACHUNAS………………………12

TABLE 2 | The ten abilities of human-nature connection in the ACHUNAS………………………...13

TABLE 3 | Names and descriptions of the nine forest locations………………………………………10

TABLE 4 | The survey items used for the ten abilities of human-nature connection………………….21

TABLE 5 | The 8-item version of the New Ecological Paradigm Scale………………………………21

TABLE 6 | The survey items used for the 16 qualities of significant nature situations……………….22

TABLE 7 | Summary of the six themes for the quality thought provocation………………………….31

TABLE 8 | Summary of themes for the category “negative aspects”…………………………………35

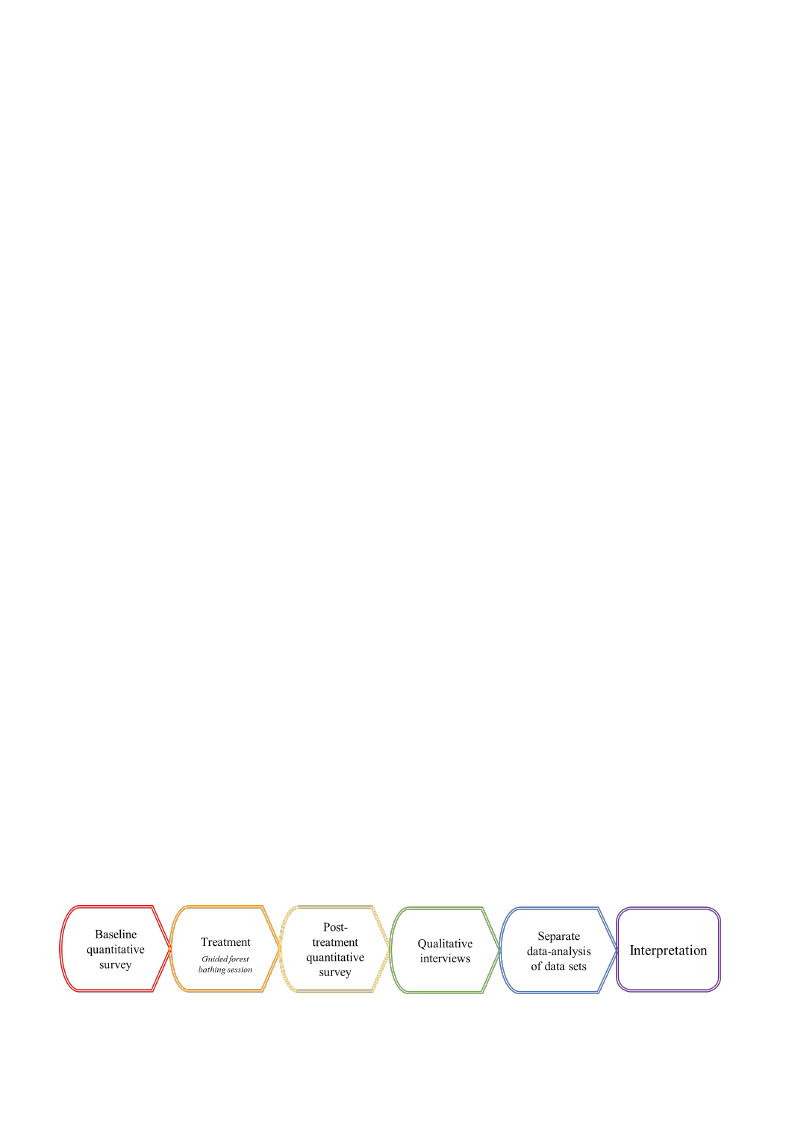

FIGURE 1 | Illustration of the sequential mixed methods research design……………………………18

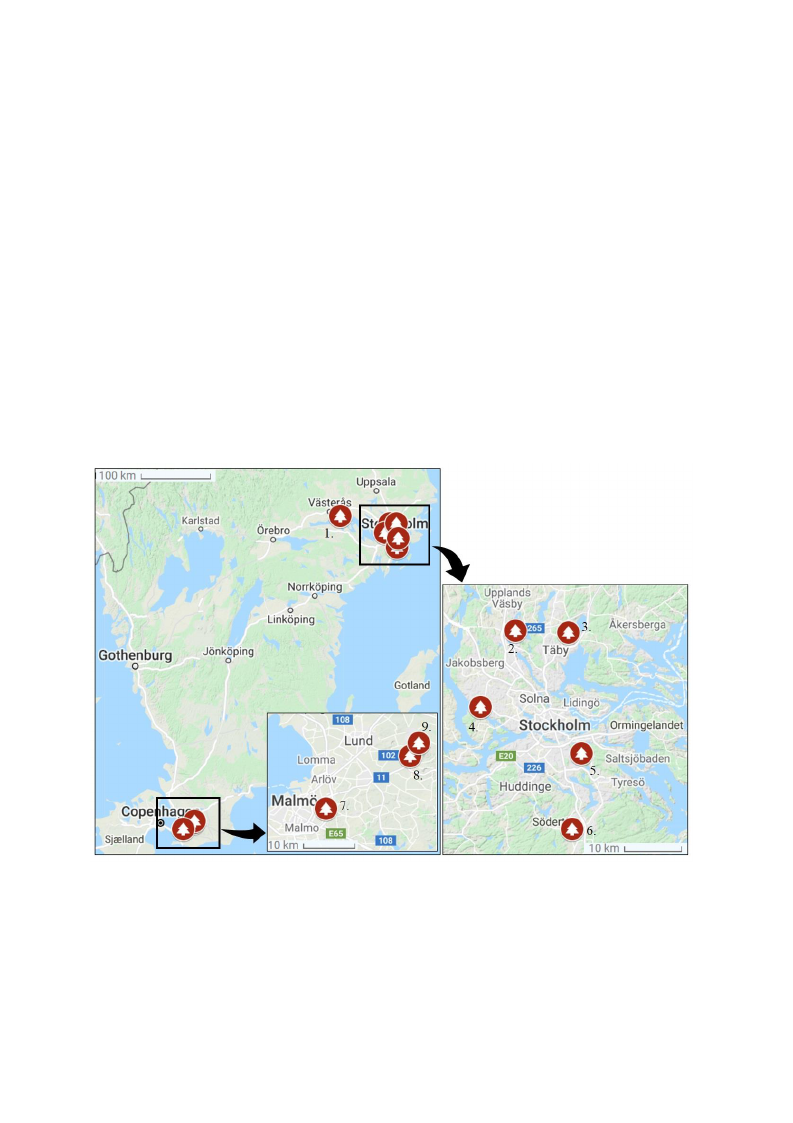

FIGURE 2 | Map of southern Sweden showing the nine forest locations……………………………..19

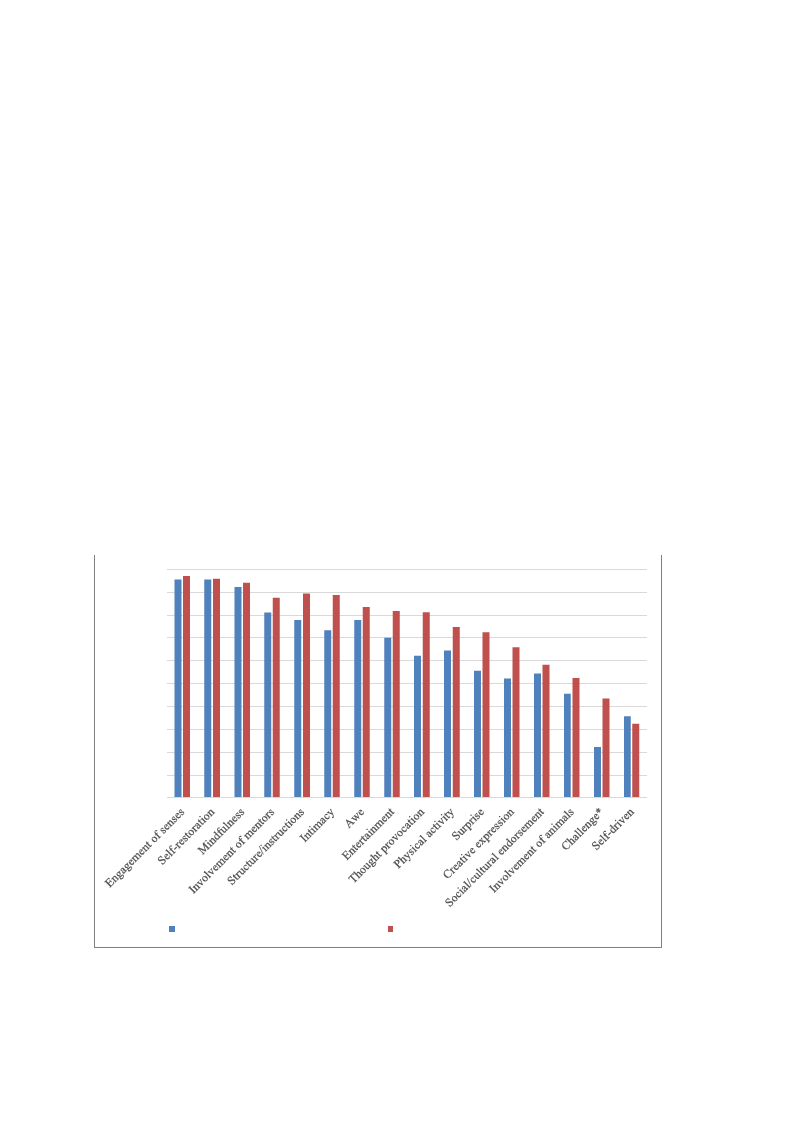

FIGURE 3 | Graph of the results for the 16 qualities of significant nature situations…………………26

ACRONYMS

ACHUNAS – Assessment framework for Children’s Human Nature Situations

HNC – Human-Nature Connection

SNS – Significant Nature Situation

NEP – New Environmental Paradigm

SNFTI – Scandinavian Nature and Forest Therapy Institute

Word count: 9 948 words

(Including footnotes, excluding tables, figures, and appendices)

7

1. INTRODUCTION

Humanity is facing great social and environmental challenges. These challenges are part of

the same social-ecological system that has kept us on a trajectory of unsustainability during

the past decades (Steffen et al. 2011). A commonly argued cause of today’s unsustainability is

the dominant Western paradigm of anthropocentrism – a human-centered environmental ethic

and worldview of separation that places only instrumental value on nature1 (Katz 1999). This

way of thinking has been suggested as a driver for the current economic growth model that

frames negative environmental impacts as externalities and nature as solely a never-ending

resource from which to exploit and profit (Katz 1999; Strang 2017). Scholars suggest that the

cognitive disconnection and lack of understanding of the interdependence between humans

and nature is not just a cause of unsustainability but a symptom of the larger changes in

society (Seppelt & Cumming 2016; Pyle 2003), such as urbanization (Cumming et al. 2014;

Giusti 2019) and a general “extinction” of direct nature experiences (Soga & Gaston 2016;

Giusti et al. 2014).

The call for humanity to “reconnect with nature” is growing stronger among both citizens and

scholars (e.g. Folke et al. 2011; Zylstra et al. 2014). Reconnecting with nature is about

shifting the relationship between humans and the rest of nature. It is a shift away from the

current unsustainable use of natural resources for short-term benefit, to a relationship in which

there is a mutually beneficial co-evolution and an acknowledgment of the interconnectedness

of people and nature (Abson et al. 2017). An umbrella term for the characterization and

analysis of people’s connection with nature is “human-nature connection” (HNC).

Interventions focused on fostering individuals’ HNC may contribute to sustainability

transformation. For example, Ives et al (2018) argue that interventions that develop

individuals’ HNC can act as deep leverage points with potential to transform the underlying

values, worldviews, and overall direction of the current societal system. There is also growing

evidence and consensus that strengthened HNC in individuals is linked to pro-environmental

concern and sustainable behaviors (e.g. Geng et al. 2015; Kals et al. 1999; Zaradic et al. 2009;

Conrad & Hilchey 2011). Fostering HNC is thus related to the “inner worlds” of people as a

realm of influence for sustainability.

1 The word nature here and throughout this thesis is conceptualized and defined as formulated by Lumber (2016,

p.8), i.e. nature is the phenomena of the physical world, including plants, animals (including humans), the

landscape, and other features of the earth and cosmos. These phenomena exist in all environments and include

phenomena shaped or managed by humanity. The creations and artefacts of humans that fall outside of the remit

of natural phenomena are not considered to be nature.

8

Acknowledging the potential of the inner dimensions of people, scholars are increasingly

discussing and exploring the potential of contemplative practices for sustainability such as

mindfulness (e.g. Wamsler 2018; Ericson et al. 2014). Mindfulness is the intentional non-

judgmental attentiveness to the present moment and is believed to be an inherent human

capacity that can be trained and developed (Buss 1980; Condon et al. 2013; Baer 2003;

Kabat-Zinn 1990). In addition to improvements in qualities such as awareness and pro-

sociality, it is theorized that mindfulness as a state and contemplative practice has the

potential to positively influence the development of individuals’ HNC (Thiermann & Sheate

2020), particularly when performed and practiced in nature (Unsworth et al. 2016). One such

mindfulness-based nature experience that is becoming popular in Europe and the US is the

Japanese therapeutic practice of ‘shinrin-yoku’, literally translated to ‘forest bathing’ (Li

2010). It typically entails a slow walk in a forested area where the senses are mindfully

allowed to “bathe” in the forest atmosphere. Forest bathing has since the 1980’s been a big

part of the national health programme in Japan (Li 2010) and currently 62 certified forest

therapy bases with guided forest bathing activities have been established in Japan with the

purpose to promote wellbeing and protect forests (Farkic et al. 2021).

In Western contexts, a key idea of guided forest bathing sessions is that the mindful, sensory

contact with nature enables a reciprocal relationship and healing process to develop between

the person being guided and the surrounding environment (SH 2019). This emphasis on

fostering mindfulness and reciprocal human-nature relationships has led several scholars to

suggest that forest bathing may affect people’s connection to nature (Lumber et al. 2017;

Kotera et al. 2020; Clarke et al. 2021). To my knowledge, however, only one study has

experimentally assessed the effects of guided forest bathing on a measure of HNC (McEwan

et al. 2021). These authors found indicatory evidence of a significant influence on nature

connection but could not draw firm conclusions. Therefore, the potentially significant effect

of guided forest bathing on individuals’ HNC warrants further investigation. Indeed,

increased scientific understanding of this effect can provide valuable insight into what

qualities of the nature experience are significant for HNC, and thus for interventions aimed at

cultivating HNC at large. In fact, the most recent review of forest bathing literature explicitly

calls for future research on the link between forest bathing and HNC (Kotera et al. 2020). This

thesis seeks to answer that call.

9

1.1. Research questions

The purpose of this thesis is to explore the potential of guided forest bathing as an

intervention for HNC. I do this by using a mixed methods approach to investigate how guided

forest bathing may influence HNC. My exploration is therefore guided by the following

research questions:

RQ 1: How does participation in guided forest bathing influence individuals’ HNC?

RQ 2: Which qualities of guided forest bathing influence HNC?

10

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1. Human-Nature Connection (HNC)

Research on the relationship between humans and nature is a large field of study with a

diversity of disciplinary perspectives, research approaches, and conceptualizations. To

consolidate, Ives et al (2017) conducted a systematic review of the literature and found that

HNC is often approached from one of three dimensions: HNC as mind, HNC as experience,

or HNC as place. Research from the first dimension understands HNC as a psychological

entity and tends to use an objectivist epistemology and quantitative methods such as

psychometric scales (e.g. Nisbet et al. 2009; Mayer & Franz 2004). HNC as experience uses

more qualitative and subjectivist approaches to describe individuals’ unique interactions and

relationships with nature (e.g. Cosquer et al. 2012). Finally, HNC as place looks at human-

nature relationships as primarily contextual using a constructionist epistemology and tries to

understand the interactions of people and specific places or landscapes (e.g. Clan et al. 2016).

To bridge these disciplinary differences, Ives et al (2017) suggest an interdisciplinary lens for

future HNC research where several of these dimensions are integrated rather than explored in

isolation. As a response to this call, Giusti et al (2018) adopted an embodied ontological

approach when exploring children’s HNC. Instead of viewing HNC as only a psychological

entity, the authors drew inspiration from the relational ontology of ‘embodied ecosystems’

(Raymond et al. 2018), which highlights the dynamic and relational values that emerge

between humans and nature. Nature experiences and the relationship humans have with their

surrounding environments are, in this view, in dynamic co-creation. The interactions between

mind, body, culture, and the environment create over time a pathway of HNC development

for the individual that has either sustainable or unsustainable properties (Giusti et al. 2019).

For the current thesis, I follow this embodied ontological approach to HNC by applying the

“Assessment framework for children’s human nature situations” (ACHUNAS).

2.1.1. ACHUNAS – An embodied approach to human-nature connection

The ACHUNAS framework (Giusti et al. 2018) was designed as a tool to assess where and

how children connect to nature. It uses two lists of criteria. The first set of 16 criteria qualifies

the kind of nature experiences people have (table 1). These criteria aim to understand how

nature experiences significantly impact the development of HNC. This serves the purpose of

understanding if a nature experience is a significant nature situation (SNS) for HNC or not.

11

The second set of criteria characterizes individuals’ HNC. In the framework, ten cognitive,

affective, and behavioral abilities define the depth and breadth of people’s HNC (table 2). The

development of these ten abilities follows a natural progression of three phases, from being

comfortable and curious in nature (“being in nature”), to being able to act in nature (“being

with nature”), to being able to care and act for nature (“being for nature”). This embodied

approach to HNC recognizes that people’s HNC is a complex set of learned abilities that

develops over time through routinization in a specific socio-cultural context (Giusti et al.

2014, Giusti 2019).

2.1.2. New Ecological Paradigm (NEP)

A conceptually related construct commonly studied together with HNC within environmental

psychology is environmental attitude. One of the most widely used instruments for measuring

people’s environmental attitude is the New Ecological Paradigm scale (Dunlap et al. 2000).

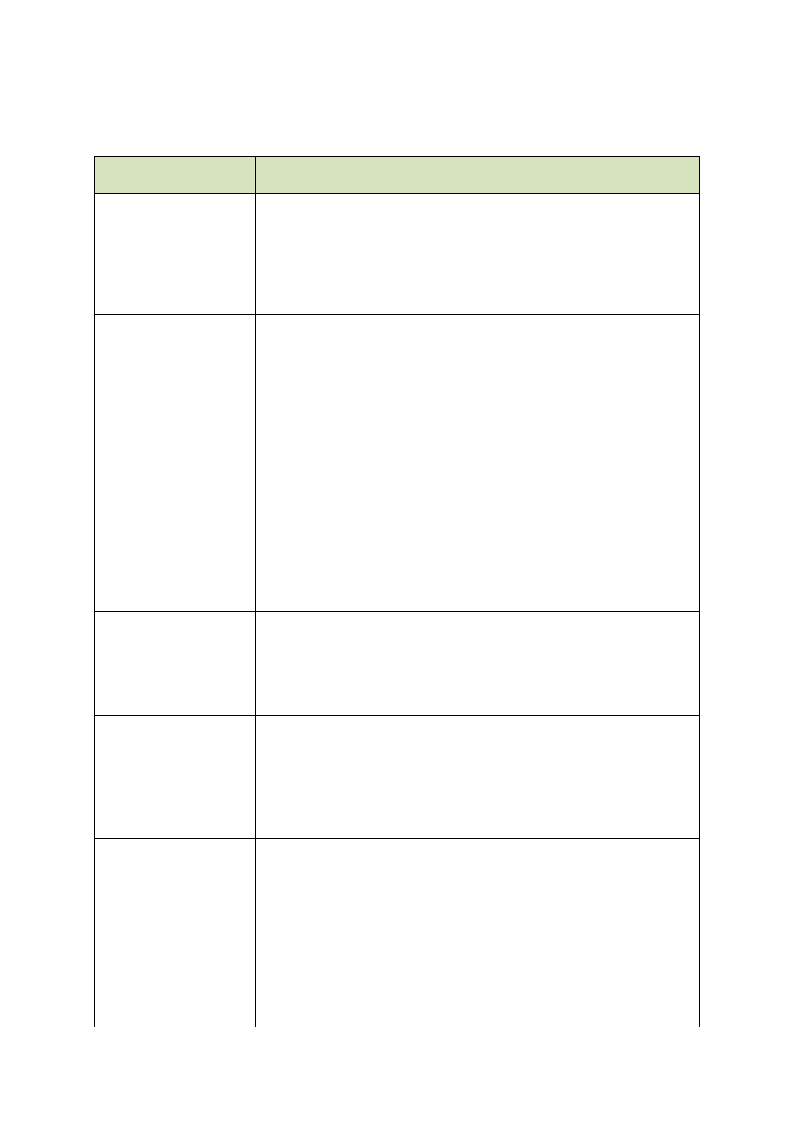

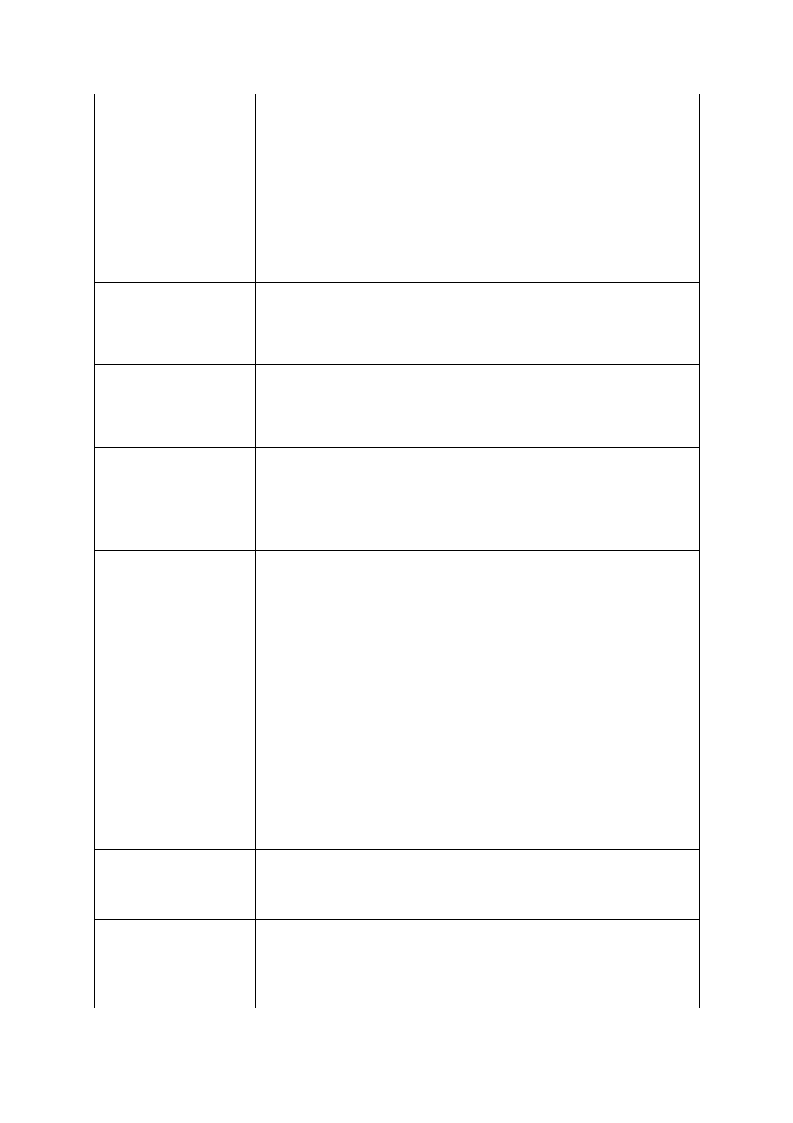

TABLE 1 | The 16 qualities of significant nature situations of the ACHUNAS, as described in Giusti et al (2018).

Quality of SNS

Entertainment

Thought provocation

Intimacy

Awe

Mindfulness

Surprise

Creative expression

Physical activity

Engagement of senses

Involvement of mentors

Involvement of animals

Social/cultural endorsement

Structure/instructions

Self-driven

Challenge

Self-restoration

Description of quality

Nature situations that are fun, joyful, amusing, or enjoyable.

Nature situations that create new ways of conceiving human-nature interaction.

Nature situations that feel private or intimate and allow a personal experience with nature.

Nature situations that are amazing, of overwhelming attraction, or mesmerizing, that create a “wow effect.”

Nature situations that grasp children’s focus and alertness, that make the child “be in the flow”.

Nature situations that are unpredictable or unexpected. In these situations children’s line of thought is

interrupted and nature draws their attention.

Nature situations that involve arts, myths, stories, music, or role-play.

Nature situations that require body movement or any form of physical activity.

Nature situations that activate children’s senses (smell, touch, hearing, etc)

Nature situations that involve persons, such as teachers, experts, or relatives, who are capable of inspiring,

encouraging, or leading the nature experience for the child.

Nature situations that involve interaction with animals.

Nature situations that involve positive peer pressure, support from significant others, social acceptance, or

cultural reinforcement.

Nature situations characterized by a set of rules that define the frame within which the child can act.

Nature situations that are chosen by the child, child-initiated (children autonomously decide when to begin

the nature activity), and open-ended (children autonomously decide when to conclude the nature activity).

Nature situations in which children overcome challenges psychologically or physically adverse conditions,

such as fear or cold.

Nature situations of psychological, physical, or social relief. For example, relief from stress, fatigue, or

gender stereotypes.

12

TABLE 2 | The ten abilities of human-nature connection and three phases of progression in the ACHUNAS as

described in Giusti et al (2018). Original descriptions are changed from “The child” to “The person”.

Phases of HNC Abilities of HNC

Description of ability

Being in nature

Feeling comfortable in

natural spaces

Being curious about nature

The person demonstrates ease in natural spaces and feels comfortable with natural

elements in the outdoors (e.g. dirt, mud, rain, or the sun).

The person shows interest and motivation in exploring nature.

Reading natural spaces

Acting in natural spaces

Being with nature

Feeling attached to natural

spaces

Knowing about nature

Recalling memories about

nature

The person is able to see the possibilities for action in natural spaces that are not

purposefully designed by man.

The person is able to perform activities in nature, for example, nature playing,

camping, or outdoor sports in nature.

The person shows a sense of belonging to specific natural spaces, to which they feel

part of.

The person demonstrates knowledge of animals, plants, and ecological dynamics.

The person is able to recall past nature experiences and tell stories of lived life with

nature.

Taking care of nature

Being for nature

Caring about nature

Being one with nature

The person is able to be responsible for nature and feels empowered to act for the

wellbeing of nature.

The person is able to feel care, concern, sensitivity, empathy, and respect for nature.

The person is able to identify with nature and has a sense of profound personal

attachment to nature that can be described as spiritual. Love for nature, humbleness in

relation to nature, and assuming to be a small part of the immensity of nature are

manifestations of this ability.

The NEP scale is designed to measure the person’s held beliefs about humanity’s relationship

with nature in order to reflect endorsement of an ecological worldview. Although both HNC

and NEP positively influence ecological behavior (e.g. Dunlap et al. 2000; Derdowski et al.

2020; Geng et al. 2015; Kals et al. 1999), the two are considered distinctly different in that

NEP is a knowledge-based cognitive construct (Mayer & Franz 2004).

2.2. Mindfulness and sustainability

Traditional mindfulness is an ancient Buddhist practice or state of being in which one is

“paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-

judgementally” (Kabat-Zinn 1994, p.4). When being mindful, “thoughts and feelings are

observed as events in the mind, without over-identifying with them and without reacting to

them in an automatic, habitual pattern of reactivity” (Bishop et al. 2004, p.232). In Buddhist

psychology, cultivation of mindfulness is known to nurture qualities such as kindness and

compassion, as well as the development of an ethical stance toward both the animate and

inanimate world (Grossman 2015). Mindfulness is also related to reduced anxiety and stress,

combined with the potential for greater awareness of one’s thoughts, emotions, and actions

13

(Chambers et al. 2009). For these reasons, many scholars are discussing and exploring the

potential of mindfulness for sustainability (e.g. Wamsler 2018; Ericson et al. 2014).

Thiermann & Sheate (2020) recently conducted an extensive review of the literature and

could find six main theoretical arguments with backing in empirical work for the benefits of

mindfulness on sustainability: 1) increased awareness and reduced automaticity in behavior,

2) enhanced personal health and subjective well-being, 3) improved pro-social tendencies

such as compassion for others and the environment, 4) stronger intrinsic and transcendental

values (altruistic and biospheric) combined with moral decision-making, 5) increased

openness to new ideas, experiences and behavior-changes, and finally 6) stronger HNC.

2.2.1. Mindfulness and HNC

There is considerable literature confirming the correlational effects between various

measurements of HNC and mindfulness. Howell et al (2011) found that mindfulness was

significantly correlated with HNC and that observing and having an attentive mind were the

strongest predictors of HNC. This suggests that mindfulness activities that involve slowing

down and actively paying attention might play an important role in the development of HNC.

The significant associations between HNC and mindfulness have also been consolidated by a

recent meta-analytic investigation including 2435 individuals by Schutte & Malouff (2018).

The authors suggest that the non-judgmental and present-moment awareness qualities of

mindfulness may “encourage individuals to more fully engage with nature experiences and

develop a sense of connectedness to nature” (Schutte & Malouff 2018, p.13).

2.2.2. Mindfulness in nature and HNC

Although studies on mindfulness in nature are quite scarce, there are indications of the

benefits. Unsworth et al (2016) recruited students to participate in a 3-day nature trip where

they were randomly assigned to either a treatment that included formal meditation and

informal mindfulness practice or a non-meditation control condition. The study results

showed that meditating and being mindful in nature had larger significant effects on HNC

than simply being in nature. Djernis et al (2019) suggest from their systematic review of

nature-based mindfulness that the significance of nature as context may be explained by the

Attention Restoration Theory’s concept of ‘soft fascination’ (Kaplan & Kaplan 1989). The

effortless attention cultivated in nature thus encourages a “letting go” and disengagement

from thoughts and compulsions, which is a common aim in mindfulness practice. However,

14

the authors conclude by stating that although nature-based mindfulness appears superior to

mindfulness in non-natural contexts, there is still a need for more research to understand what

constitutes a mindfulness intervention in nature and how to best design such interventions.

2.3. Forest Bathing

2.3.1. Origin

‘Shinrin-yoku’, literally translated to ‘forest bathing’, is a Japanese mindfulness-based

practice where people “immerse themselves in nature, while mindfully paying attention to

their senses” (Kotera et al. 2020, p.1). The concept was originally coined and implemented by

the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in the early 1980s, in an attempt

to encourage the Japanese people to use forests for improved wellbeing and to regulate work-

related stress (Li 2010). It has since become a big part of the national health programme in

Japan where it is also referred to as ‘forest therapy’, or ‘shinrin-ryoho’ in Japanese. Today,

the Japanese Forest Therapy Association has established 62 certified forest therapy bases and

trails where guided forest bathing is offered to promote wellbeing while also protecting the

forests and revitalizing rural tourism (Farkic et al. 2021). The concept and popularity of forest

bathing by Japanese people is said to have its roots in the animistic beliefs and reverence for

nature that is part of the Shinto and Buddhist tradition (Li 2018). Thus, recognizing the forest

as a source of wellbeing and a place of connecting with the spirits of nature made sense in the

local cultural context, and the practice was quickly embraced by Japan and surrounding

countries such as China.

2.3.2. Guided forest bathing in the West

In recent years, the practice of forest bathing has spread to the Western world, primarily the

U.S. and Europe, where it has inspired independent frameworks and methodologies for

guided forest bathing sessions adapted for Western contexts. The way guided forest bathing is

conducted varies, but a key idea in many Westernized forest bathing frameworks is that a

deepened relationship and reciprocal healing process develops between the person and the

environment (SH 2019). Indeed, in Sweden, a framework for guided forest bathing sessions

has been developed by the Scandinavian Nature and Forest Therapy Institute (SNFTI) with

the purpose of promoting increased well-being and a deepened connection and relationship to

nature. A guided session by SNFTI consists of a 2 to 3-hour slow forest walk with a certified

forest bathing guide. The structure of the session follows a process of four distinct phases that

15

aims to move the participant from separation to a state of deepened connection through

invitations to sensory opening activities and ends with integration (Petra Ellora Cau

Wetterholm, personal communication, November 12, 2021).

2.3.3. Guided forest bathing and mindfulness

A fundamental concept within the methodology of guided forest bathing by SNFTI is

Naturvaro®2. The word, loosely translated from Swedish to “natural presence”, describes a

form of natural mindfulness; a mindful state of being that is believed to arise and deepen

progressively during a guided forest bathing session (Petra Ellora Cau Wetterholm, personal

communication, November 12, 2021). According to Wetterholm (ibid), the state and practice

of naturvaro differ from traditional mindfulness in that it does not use any specific approach

or technique to felt sensations, emotions, or thoughts. Instead, the participants are invited and

encouraged by the guide during the session, yet free to follow and allow what feels right and

comfortable or natural to them. Indeed, this adaptability was also noticed by Clarke et al

(2021) when comparing the practices of forest bathing and mindfulness in their recent paper.

The authors found that while mindfulness emphasizes focused awareness and acceptance of

the internal environment, forest bathing may be more accessible by shifting the attentional

focus to the external environment. In this way, forest bathing may suit and benefit a broader

range of people through its gentle and accommodating approach to mindfulness.

2.3.4. Guided forest bathing and HNC

Most existing research on forest bathing has focused on the health benefits (Kotera et al.

2020), which include therapeutic effects on the cardiovascular, immune, and respiratory

system, as well as increased mental relaxation, reduced anxiety, and feeling of selflessness

and gratitude (Hansen et al. 2017). More recently, the potential influence of guided forest

bathing on HNC has received attention among scholars (e.g. Lumber et al. 2017; Kotera et al.

2020; Clarke et al. 2021). To my knowledge, only McEwan et al (2021) have included a

measure on HNC in their recent pilot study investigating the effects of guided forest bathing

on wellbeing measures on participants in the UK. The authors used the Inclusion of Nature

with Self scale (INS; Schultz 2001), a single-item measure assessing the level of inclusion of

nature in a person’s self-concept, to measure HNC and found a significant increase after

guided forest bathing. This evidence is indicative of a possible effect on HNC. However,

2 The word and methodology of Naturvaro is trademarked by SNFTI-founder Petra Ellora Cau Wetterholm.

16

given the methodological limitations of single-item measures (Diamantopoulos et al. 2012)

and the call for a multidimensional approach to HNC (Ives et al. 2017), additional research is

important to validate this potentially significant effect.

17

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Ontological position

My methodological approach in this thesis is grounded in the relational ontology of embodied

ecosystems as operationalized in the ACHUNAS framework (Giusti et al. 2018). Through this

lens, HNC is understood as a dynamic outcome of an interaction between mind, body, culture,

and environment – encompassing all three dimensions of HNC: psychological, experiential,

and contextual (Ives et al. 2017; Giusti et al. 2019).

3.2. Mixed-methods research design

This study employed a sequential mixed methods design (figure 1). Chronologically, the

study began with quantitative surveys that all participants answered before and after attending

a guided forest bathing session. Afterward, I conducted semi-structured interviews with a

random selection of the participants to explain and triangulate the survey results. The

quantitative and qualitative data sets were then analyzed separately, and their insights were

combined during interpretation. This research design allowed me to compare quantitative and

qualitative results and to qualitatively deepen the meaning and understanding of the variables

being studied quantitatively (Creswell & Clark 2006). This design is also compliant with the

multidimensional conceptualization of HNC and produced a nuanced understanding of how

guided forest bathing influences participants’ HNC.

3.3. Guided forest bathing sessions

The guided forest bathing sessions in this study were conducted in collaboration with the

Scandinavian Nature and Forest Therapy Institute (SNFTI). In Sweden, SNFTI is the main

structural platform for standardizing guided forest bathing in the region and its research-based

methodology is taught to certify new forest bathing guides through the institute. The SNFTI

methodology is thus considered the most consistent, repeatable, and controlled and was for

this reason chosen for the study.

FIGURE 1 | Illustration of the sequential mixed methods research design used for this study.

18

All data collection took place in Sweden during a nationwide guided forest bathing day

organized by the SNFTI on March 20th, 2021, with ten certified guides leading guided

sessions in nine different forest locations. The ten locations were mixed forests and situated

around the cities Stockholm, Malmö, Lund, or Västerås (figure 2). The forest environments

differed in characteristics (see summary in table 3). All sessions allowed a maximum of 5

participants excluding the guide, were two to three hours long, and took place between 9am

and 2pm. The sessions followed the confidential SNFTI methodology and a specific routine

consisting of invitations including slow walking, guided sensory-activating exercises, short

group sharings, and a closing tea ceremony.

FIGURE 2 | Map of southern Sweden showing the nine locations of where the guided forest bathing

sessions took place (Google, n.d.). Two of the sessions took place in Törnskogen nature reserve

(location number 2).

19

TABLE 3 | Names and descriptions of the nine forest locations used for the guided forest bathing sessions.

The list numbers correspond to the numbers in figure 2.

Locations

1. Solviksskogen

nature reserve

2. Törnskogen nature

reserve

3. Skavlöten outdoor

courtyard

4. Grimstaskogen

nature reserve

5. Nacka nature

reserve

6. Rudan nature

reserve

7. Gyllins garden

8. Dalby Norreskog

nature reserve

9. Måryds nature

reserve

Characteristics of forest

Urban nature reserve located 15 km southeast of city Västerås, about 100 km west of the capital

Stockholm. Hilly landscape dominated by older pine and spruce forest.

Nature reserve close to the northern Stockholm suburb Sollentuna. Hilly landscape with a lot of pine and

wetlands, elements of deciduous forest and some open cultivated land.

Recreational area within a nature reserve, close to the northern Stockholm suburb Täby. Areas with older

pine forests, some mixed forest and open land. Next to a lake.

Nature reserve close to the western Stockholm district Hässelby. Mostly mixed and deciduous forests, with

small patches of pine and rocky ground.

Nature reserve close to the southern Stockholm district Bagarmossen. Varied area with open ground, some

mixed forest, pine trees, rocky outcrops, and wetlands with small brooks.

Nature reserve with recreational area close to Stockholm, located next to a train station. Forested parts

with coniferous trees, deciduous and wetland forest elements. Previously used for mowing and as pasture.

Urban nature park in the Husie district of the city Malmö in southern Sweden. Was formerly used as

commercial garden. Mix of open land with forested areas of beech, coniferous and oak trees.

Semi-urban nature reserve close to the suburb Dalby, located about 10 km east of the city Lund in southern

Sweden. Mix of young and old oak forest, beech forest, wetlands, and pastures.

Rural nature reserve located about 14 km east of the city Lund in southern Sweden. Mostly open heathland

and pastures with smaller patches of deciduous forest.

3.4. Quantitative surveys

3.4.1. Participant selection method

The study employed convenience sampling by recruiting participants from the public who had

already signed up to join the ten guided forest bathing sessions included in the study.

Interested persons applied by filling out a screening survey with a plain language statement

(see appendix 1). Only persons over 18 years were accepted as study participants and so

persons who fulfilled this criterion were contacted and asked to give consent for participation

before finally being accepted as study participants (see appendix 2). In the end, a total of 26

participants completed both surveys. The incentive to participate in the study was a 50 SEK

discount on the guided forest bathing session fee (original value 350 SEK).

3.4.2. Data collection procedure

Study participants were asked to answer two online surveys created using Google Forms. The

pre-treatment survey was sent out via email to the study participants one day before the

guided forest bathing sessions and the post-treatment survey was sent out on the day of the

sessions. Participants were asked to answer the surveys as soon as possible before and after

the session to reduce potential limitations to internal validity. Both surveys were available in

two language versions (English and Swedish) to ease comprehension.

20

3.4.3. Survey measures

HNC was assessed using a scale composed of ten items (table 4). Each item corresponded to

one of the ten abilities of HNC as formulated in the ACHUNAS framework (Giusti et al.

2018). The surveys also included the shorter, 8-item version of the New Ecological Paradigm

(NEP) scale (table 5; Zhu & Lu 2017) to measure the effect on environmental attitude in order

to compare with the HNC results. Lastly, the qualities of guided forest bathing affecting HNC

were assessed in the post-treatment survey using a scale with the list of 16 qualities of

significant nature situations as developed in the ACHUNAS (Giusti et al. 2018). The original

descriptions of the qualities were slightly modified to fit adults and the context of guided

forest bathing. Each quality was represented by one item (table 6). All measures employed

10-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (“Do not agree at all”) to 10 (“Agree completely”).

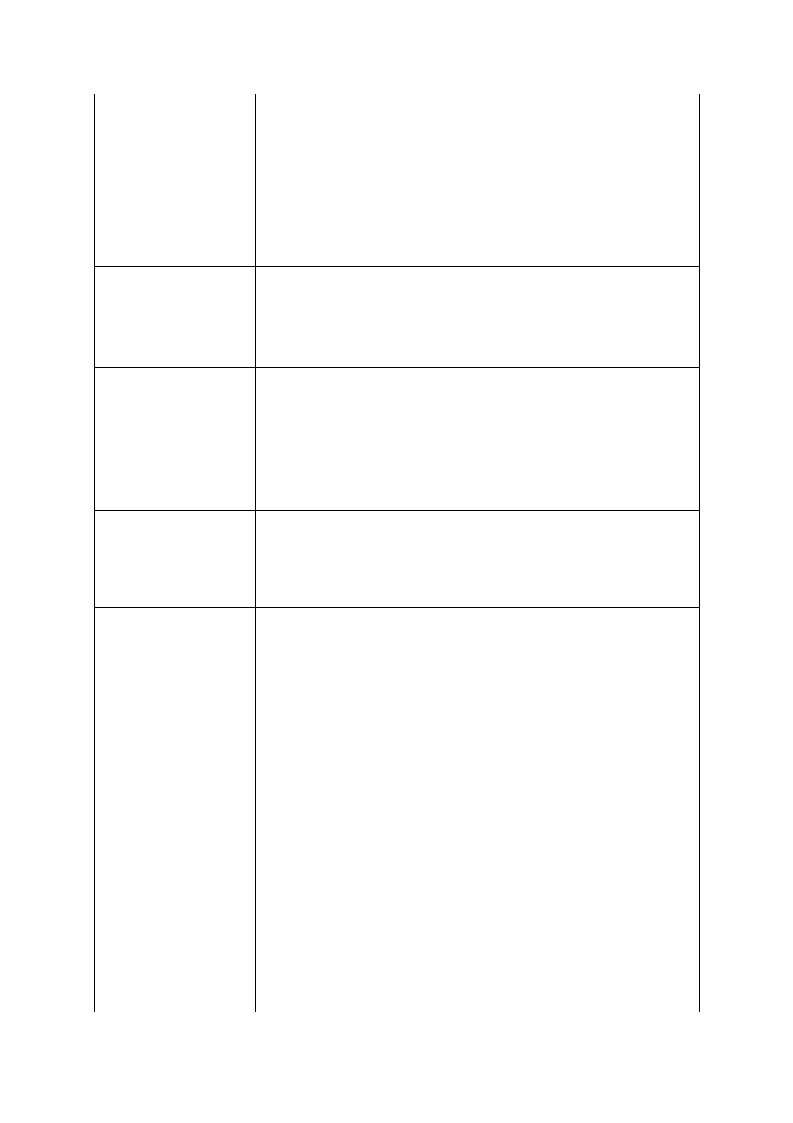

TABLE 4 | The survey items used for each of the ten abilities of HNC.

Ability of HNC

Feeling comfortable in natural spaces

Being curious about nature

Reading natural spaces

Acting in natural spaces

Feeling attached to natural spaces

Knowing about nature

Recalling memories about nature

Taking care of nature

Caring about nature

Being one with nature

Survey item

1. I am comfortable being outdoors, even in unpleasant weather.

2. I am curious about how different plants, animals, and ecosystems look and work.

3. I can find something to do everywhere in nature.

4. There is an infinite number of activities that I can do in or with nature.

5. I feel attached to certain places in nature as they are special to me.

6. I can tell if plants, animals, and ecosystems surrounding me are healthy or not.

7. I have vivid memories in or with nature that have shaped who I am.

8. I know how to take care of plants, animals, and ecosystems around me.

9. I am concerned, care profoundly, and respect all plants, animals, and ecosystems around me.

10. I feel a deep connection and love for the plants, animals, and ecosystems around me.

TABLE 5 | The 8-item version of the New Ecological Paradigm Scale as by Zhu & Lu (2017).

New Ecological Paradigm Scale items

1. We are approaching the limit of the number of people the Earth can support

2. When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences

3. Humans are seriously abusing the environment.

4. Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist.

5. Despite our special abilities, humans are still subject to the laws of nature

6. The Earth is like a spaceship with very limited room and resources.

7. The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset.

8. If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe.

21

TABLE 6 | The survey items used for each of the 16 qualities of significant nature situations, with adapted

descriptions to fit the context of the study.

Quality of SNS

Entertainment

Description

The guided forest bathing experience felt fun, joyful,

amusing, or enjoyable.

Survey items

1. I had a lot of fun during the session.

Thought provocation

The guided forest bathing experience provoked thoughts

and new ways of conceiving human-nature interaction.

2. The session made me think about nature in a new

way.

Intimacy

The guided forest bathing experience felt private or

intimate and allowed a personal experience with nature.

3. The session felt intimate, it was a very personal

experience with nature.

Awe

The guided forest bathing experience felt amazing or

mesmerizing, created a “wow effect.”

4. The session was amazing and mesmerizing.

Mindfulness

The guided forest bathing experience grasped my focus 5. The session grasped my focus and made me feel

and alertness and made me feel present and “in the flow”. present “in the moment”.

Surprise

The guided forest bathing experience interrupted my line

of thought and drew my attention to nature.

6. The session was surprising.

Creative expression

The guided forest bathing experience involved arts,

myths, stories, music, or role-play.

7. The session involved stories, music, and other art

forms.

Physical activity

The guided forest bathing experience included some body

movement or physical activity.

8. The session involved physical activity.

Engagement of senses

The guided forest bathing experience activated my senses

(smell, touch, hearing, etc).

9. The session engaged all my senses.

Involvement of

mentors

The guided forest bathing experience involved a person

who inspired, encouraged, or led me through the

experience.

10. The session was together with people who

inspired, encouraged, or led me through the

experience.

Involvement of

animals

The guided forest bathing experience included physical

or non-physical interaction with animals.

11. The presence of and/or interaction with animals

was a central part of the session.

Social/cultural

endorsement

The guided forest bathing experience involved positive

peer pressure, support from significant others, social

acceptance, or cultural reinforcement.

Structure/instructions

The guided forest bathing experience was characterized

by a set of rules or instructions that formed the structure

of the experience.

12. My surrounding social community of people

was central to making this session memorable.

13. The session was structured by a clear set of

instructions and guidelines.

Self-driven

The guided forest bathing experience was self-initiated

and open-ended (I autonomously decided when to begin

and conclude the nature experience).

14. I decided when to start and when to finish the

session.

Challenge

The guided forest bathing experience challenged me or

made me overcome psychologically or physically adverse

conditions, such as fear or cold.

15. The session was challenging for me physically

and/or mentally.

Self-restoration

The guided forest bathing experience gave me

psychological, physical, or social relief. For example,

relief from stress, fatigue, or gender stereotypes.

16. The session was relaxing or restorative for me

both physically and mentally.

22

3.4.4. Quantitative data analysis

The quantitative data analyses tested the hypotheses that the guided forest bathing sessions

positively influenced HNC and NEP scores. Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted

using Excel and all statistical tests were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.

Independent samples t-tests were used to test baseline differences in the abilities of HNC.

NEP, and the 16 qualities of SNS within the sample between participants with and without

previous experience of guided forest bathing. Paired-samples t-tests were then conducted to

determine significant differences before and after in 1) HNC, 2) each of the three phases of

HNC, 3) each of the ten abilities of HNC, and 4) NEP. The scores for each quality of SNS

were analyzed descriptively. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was then used to

determine which quality of guided forest bathing had the highest predictive power to change

HNC.

3.5. Qualitative semi-structured interviews

3.5.1. Sampling and data collection procedure

A random selection of the study participants was invited to be interviewed post-treatment,

resulting in a total of 16 interviews. The interviews were semi-structured and took place

within one week following the guided forest bathing sessions. A set of open-ended

interviewing questions were formulated in advance to guide the conversation and covered two

main areas: 1) questions about the interviewee’s subjective experience of the guided forest

bathing session, and 2) questions about thought-provocation and if insights and learnings

were derived from the experience (see interview guide in appendix 3). Participants were given

the choice to conduct the interview in Swedish or English and to be interviewed via Zoom

(with or without video) or via telephone call. All interviews ended up being conducted in

Swedish, were 45 to 60 minutes in length, and recorded with consent. As compensation for

participating, each interviewee received 200 SEK.

3.5.2. Qualitative analysis strategy

All interviews were transcribed manually and then coded and analyzed using MAXQDA Plus

2020. Analysis followed the 6-phase process of thematic analysis as described by Braun &

Clarke (2006). Analysis began with phase 1: becoming familiar with the data, through the

transcribing and then re-reading of the transcripts several times and taking notes on the way.

This was followed by an iterative cycle of phase 2: inductively generating initial codes and

23

phase 3: searching for themes. The analysis then moved into a new iterative cycle consisting

of phase 3: searching for themes, and phase 4: reviewing themes, where relevant candidate

themes were identified and the codes and each data segment were reviewed, refined, and

collated several times, checking for consistency and aiming for internal homogeneity and

external heterogeneity. Here, the themes were organized and placed into one of three broad

categories: the first containing the 16 qualities of SNS as overarching themes, the second

containing themes relating specifically to the quality thought provocation, and the third

containing aspects expressed or interpreted as negative or having a negative influence. Lastly,

the analysis moved into phase 5: defining and naming the themes within the broad categories,

which included translating the themes, codes, and quotes from Swedish to English, before the

last phase where the results are reported.

24

4. RESULTS

4.1. Descriptive and statistical survey results

4.1.1. Sample description

Within the sample (n=26), there were 24 females and 2 males. More than half (56%) were

between the age of 46-65 years old, followed by an age group of 30-45 years old (31%). All

participants reported living in or near urban environments. 17 participants did not have

previous experience of guided forest bathing and both males belonged to this group. The pre-

treatment survey suggests that the study sample had a relatively high baseline HNC (M=8.2 of

max 10). When analyzing differences within the sample, independent samples t-tests suggest

that the participants without previous experience of guided forest bathing had significantly

higher baseline HNC than those with previous experience (t(9.565)=-.995, p=.002, d=.515).

There was no significant difference in baseline NEP score between the two groups (p=.81).

4.1.2. Validity and reliability of ACHUNAS

The 10-item HNC measure and the subscale with the 16 qualities of SNS developed for this

study both had high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.9 and 0.84, respectively),

suggesting high reliability of the scales.

4.1.3. HNC scores

When analyzing the entire sample, a paired-samples t-test suggests that HNC after guided

forest bathing is significantly higher than the score before the session (t(25)=-3.521, p=.002).

The effect size of the difference is medium to large (d=.69). However, this result is

misleading in the light of the results from separately analyzing the participants with and

without previous experience of guided forest bathing. For the participants with previous

experience in guided forest bathing, there are no significant increases for neither HNC (p>.1),

its phases (p>.05), or any of the abilities of HNC (p>.05). For participants without previous

experience in guided forest bathing, a paired-samples t-test suggests that their HNC

significantly increased after the session (t(16)=-3.417, p=.0035) and the effect size here is

large (d=.829). Specifically, the increase was in the second and third phase of HNC: “being

with nature” (t(16)=-3.558, p=.003, d=.863) and “being for nature” (t(16)=-2.167, p= .046,

d=.526). For these participants, the abilities of HNC affected by guided forest bathing were:

“recalling memories about nature” (t(16)=-2.864, p=.011, d=.695), “reading natural spaces”

(t(16)=-1.426, p=.027, d=.588) and “being one with nature” (t(16)=-2.293, p=.029, d=.580).

25

4.1.4. NEP scores

Paired samples t-tests suggest that NEP was not affected by guided forest bathing (p>.1). This

is true both for participants with and without previous experience of guided forest bathing

(p>.1).

4.1.5. Qualities of SNS

The survey result for the qualities of guided forest bathing is presented in figure 3 and shows

that engagement of senses, self-restoration, and mindfulness were especially important for the

participants (M>9 of max 10). The group of participants without previous experience of

guided forest bathing rated the quality “challenge” significantly higher than those with

previous experience (t(24)= -2.208, p=.001, d=.91). The final model from the stepwise

multiple regression analysis suggests that the qualities of SNS reported by the participants

predict 25% of the variance in HNC (F(1.24)=7.961, p=.009, R2=.249). Yet, only one

predictor variable, mindfulness, contributes significantly to the model (B=.26, t=2.82,

p=.009). This means that HNC increased with 0,26 units for each unit increase in the quality

mindfulness.

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Participants with previous experience

Participants without previous experience

FIGURE 3 | Graph showing the survey results of the mean scores for each of the 16 qualities of SNS,

comparing the participants with and without previous experience of guided forest bathing. There is

only a significant difference between the two groups of participants in the quality challenge (p=.001,

marked with *).

26

4.2. Explanatory insights from interviews

The results from thematic analysis of the interview data are presented here in three broad

categories: 1) Guided forest bathing as significant nature situation, 2) Thought provocations,

and 3) Negative aspects. All interviewees expressed a pre-existing affinity for spending time

in nature. Of the 16 conducted interviews, ten interviewees did not have experience of guided

forest bathing prior to the study. To maintain anonymity, all exemplar quotes are labeled

P.01- P.16 to represent the 16 interviewees and the label ends with either “n” for persons new

to guided forest bathing or “e” for those with previous experience.

4.2.1. Guided forest bathing as significant nature situation

This category contains the qualities of SNS as overarching themes, except for the quality

thought provocation which is presented separately in 4.2.2. Each quality has several

subthemes with mentions by interviewees either interpreted or expressed as having a positive

influence on their experience. A complete list of subthemes for all SNS qualities is available

in appendix 4. Subthemes were found for all qualities of SNS except for the quality “self-

driven”, which also had the lowest rating in the survey results. Other qualities less commonly

mentioned in the interviews were “involvement of animals”, “creative expression”, and

“challenge”, thus also consistent with the ratings in the survey results. No distinction could

however be found in the interview data between participants with and without previous

experience of guided forest bathing for the quality “challenge”. This is contradictory to the

significant difference found in the rating of this quality in the survey.

Qualities that were frequently expressed by the interviewees as important to their guided

forest bathing experience were primarily “engagement of senses”, “self-restoration”,

“mindfulness”, “structure/instructions” and “involvement of mentors”. Again, this aligns with

the findings in the quantitative survey and the interview data help explain how these qualities

were expressed in the nature experience.

4.2.1.1. Engagement of senses

The quality of engagement of senses was rated among the most important in the survey and

was also continually mentioned by all interviewees, regardless of previous guided forest

bathing experience or not. Interviewees said that engagement of the senses contributed to

feelings of calm, relaxation, mindfulness, and a deeper experience of the forest compared to

other nature experiences. Some interviewees expressed it as:

27

“You take in the forest in a better way, by engaging all the senses… not just by

looking for mushrooms!” [P.08n]

“With the sense of hearing we had one [invitation] where we sat still … I thought that

was … that was very calming and relaxing.” [P.14n]

Being guided into activating and using one sense at a time was especially impactful for the

interviewees: “It created a sense of security to check in with the sense of sight first, like, well

now it is safe so I feel ready to close my eyes” [P.13e]. The other subthemes for engagement

of senses include being quiet in order to listen better, developing specific senses (for example

by smelling moss and touching tree bark), and activating a wide-angle perspective to take in

the whole forest in sight.

4.2.1.2. Self-restoration

Related to the previously presented quality, the guided forest bathing experience felt

restorative to all the interviewees mainly by taking in the forest with all the senses. For

example, one interviewee again compared it to mushroom-picking: “When you pick

mushrooms, you are not relaxed with all your senses. Instead you are very extremely focused

with your vision and perhaps sense of smell, to find that mushroom” [P.16e]. Interviewees

linked the calming effect to aspects related to the structure of the session, such as the slow

pace, being guided, and closing of the eyes. One interviewee expressed being so relaxed that

they “ended up in microsleep for a while” [P.06n]. The self-restorative quality was also

expressed as being related to social relief, where feelings of not having to perform and getting

alone-time were frequently mentioned:

“I did not feel that I was supposed to accomplish anything … It makes you calm and

able to focus on being here and now. There were no demands. That was nice.” [P.04n]

“It was very relaxing and wonderful to take these moments to lie down or sit ... and be

in silence in solitude for a while. You were not supposed to talk to each other … I

think that was good and helped me see nature in a different way.” [P.15n]

4.2.1.3. Mindfulness

Mindfulness was indicated by the statistical analysis to be the quality significantly predicting

the positive influence on HNC. In the interviews, the quality was mainly conveyed as

different expressions of being present in the moment and as a consequence of taking in the

forest with all the senses. For example, some interviewees explained how the sensory

activation took away focus from thoughts about work, the past or the future. Another

28

highlighted being in nature in a way not usually practiced: “When you go for a walk in nature,

you might listen to a podcast… But here your mobile was turned off and you were just being

here, in nature” [P.11n]. There was a noticeable emphasis among many of the interviewees

that the guided forest bathing session helped them become mindful in a way that is

reminiscent yet different from other mindfulness and meditation practices, as illustrated in

these quotes:

“You have thoughts that come and go, but you were allowed to have that.” [P.08n]

“It was good that I got to try walking and being mindful. Because meditation for me

can be a bit challenging, when you have to sit for a long time and observe the breath

… It was nice to like, yes now I will observe how that leaf moves in the wind and then

just stand and look at it for 10 seconds [laughs]” [P.11n]

“To be in the present moment can also be to actually notice a much larger part of the

stimulus that your mind gets from the environment you are in … To stop and let the

impressions come just as they are and open up to all impressions.” [P.12e]

4.2.1.4. Structure and involvement of mentors

Aspects related to the structure of the guided forest bathing session were often mentioned by

the interviewees as having a meaningful impact on their experience. For the interviewees who

were new to the experience of guided forest bathing, the group setting was particularly

impactful as it created a safe space where unusual activities are acceptable. One interviewee

shared: “Lying down in the woods… you don’t do that otherwise. And above all not in a

smaller area like this where people run past you, then they would think you are crazy”

[P.09n]. They continued by saying: “It is easier to do it in a group, because then [people

running by] understand that there is a purpose to lying there”.

Having a guide and being guided enhanced the qualities of self-restoration and mindfulness

by making the interviewees feel taken care of and not having to be in control: “I think it's so

nice that somewhere in the corner of my eye I can see the guide … oh there she goes so I’ll

just follow. I do not have to think so much… I think it is absolutely wonderful” [P.02e].

Importantly, the involvement of a guide appears to have triggered significant thought

provocations for the interviewees who were new to the experience, particularly the symbolism

and terminology used by the guide: “What gave the biggest impression on me really, was that

[our guide] said … that we should think of the trees as living beings… they are still growing.

It is easy to not think of them as living beings” [P.06n].

29

4.2.1.5. Social-cultural endorsement

Although the quality social-cultural endorsement was not among the highest rated qualities in

the survey, the interviewees without previous experience commonly mentioned the

importance of the short group sharings. These created a socially supporting and allowing

setting where “if there was something you wanted to share you could say it, but it did not feel

forced to do it” [P.04n]. Hearing the other participants share their perspectives enriched the

experience and also triggered thought provocation, as illustrated by this interviewee:

“It's always cool to like… Someone discovers this and someone else thought about this

and a third think like this. To take part in other people's thoughts and reflections that I

do not think about at all.” [P.06n]

4.2.2. Thought provocations

Thought provocation is presented as its own broad category although it was not among the

highest rated qualities of SNS in the survey results. This is due to the depth and breadth of

thought provocations mentioned by the interviewees when asked about it during the

interviews. Six overarching themes were identified for this quality (see table 7 and appendix

4). Many of the thought provocations also enable valuable comparison and potential

explanation of the survey results, as further described for each theme below.

4.2.2.1. Connectedness with nature

This theme reveals how interviewees thought about the impact of the guided forest bathing

experience on their own perceived feeling of HNC. It is interesting to note that the clear

distinction in baseline HNC and in the effect of guided forest bathing on HNC found in the

survey results between participants with and without previous experience of the practice is not

evident in the interview data. Instead, three subthemes of responses were identified. The first

illustrates how about half of the interviewees, including persons new to the experience,

perceive that their relationship or connection with nature has not changed. Instead, they

explain how just one session is not enough to change how they feel and highlight that they

already felt strongly about nature before: “Since the forest bathing, you mean? No, I can’t say

that… I feel the same as before, for nature. There's no difference” [P.04n].

30

TABLE 7 | Summary of the six themes for the SNS quality thought provocation. A complete list of

subthemes for these themes is available in appendix 4.

Theme

Brief description

Exemplar quotes

Connectedness with

nature

Participants’ perceived

connectedness with nature.

"To be a little more in harmony with nature instead of… that the

forest is something you just walk in and have coffee in and then

leave. That this became a new experience in itself, to sit in the forest

and just breathe." [P.11n]

Guided forest bathing Experience and methodology "It's like something you did when you were younger, playing in the

as a method and

of guided forest bathing.

forest… I have not done it in many years, but it is clear that it… you

experience

get closer to nature." [P.05e]

Shifts in perception of Shifts and changes in the

nature

perception of nature.

"That before drinking the tea you pour a little bit back to nature. So

it is an insight that we are dependent on each other; if I take

something, I must also give something back, so I think there is a

great symbolism in that." [P.13e]

Rediscovery of nature Rediscovery of nature and

forests.

"You are reminded of … the importance of the forest. It's not like

every time I go into the forest, I think about all these things. But

maybe I will do next time I go to the forest." [P.06n]

Human impact on

nature

Self-inquiry &

personal changes

Noticing environmental

"I felt sad to see that there was a lot of littering in some places.

issues or human's negative People had pulled out carpets, thrown beer cans, yes lots of plastic

impact on nature and forests. items…" [P.11n]

Changes or inquiry about the "I was actually reminded that... being in the forest gives… That it

self.

gives me something. And that I should prioritize it [being in the

forest]." [P.14n]

The second subtheme captures the response from one interviewee with previous experience of

the practice who emphasized that the guided forest bathing session is more about connecting

to the self: “Forest bathing is more something that is inward than outward for me. Not in

relation to nature perhaps but more into myself” [P.12e]. The third subtheme however

illustrates that several interviewees, regardless of previous experience of guided forest

bathing, did indeed express that the session influenced their relationship to nature, especially

in terms of feeling closer to nature:

“You feel extra closeness with nature and how important nature is and how can I

nurture it, and so on. And what can it give me and what should I give it? It [the guided

forest bathing session] definitely reinforces that.” [P.03e]

“It has become… closer to me, through this forest bathing session. Nature has come

closer, the forest has come closer... It's weird that it can be like that but… yes, it

actually has. It has become a stronger love in some way.” [P.10n]

31

4.2.2.2. Guided forest bathing as a method and experience

This theme captures thought provocation about guided forest bathing. This includes insights

about the restorative benefits, the need to attend guided forest bathing regularly to “refill”

before “the hamster wheel starts spinning again” [P.12e], and wanting to share about guided

forest bathing with others: “I think I will actually mention it during the parent/teacher

meeting next week” [P.10n]. The most prevalent comment among interviewees new to the

guided forest bathing experience was however related to learning new activities to do when

visiting a forest next time, such as moving at a slower pace, stopping occasionally, and using

more senses. One interviewee shared: “I was thinking that this, this [activity] I want to do

when we are out and about on our hikes. To stop and… just close the eyes and feel the

moment and the surroundings” [P.04n]. This thought provocation indicates a developed

ability to see possibilities for action in nature and could thus explain the significant increase

in the ability of HNC “reading natural spaces” found in the survey results. The experience

also seemed to provoke thoughts about past memories for the interviewees without previous

experience of guided forest bathing, especially from childhood where they remember

spending time in nature in a similar way, as illustrated by this interviewee:

“When I was out with my mother or maybe with older relatives… you were out in

nature and you kind of sat by a stream and looked at the stream or you felt the moss

and how different mosses felt and so on. So it was a bit like that… something that you

may have done as a child and that you have forgotten a bit and lost in general society

as well, this type of contact with nature.” [P.14n]

Similarly, this could explain the significant increase in the ability of HNC “recalling

memories about nature” found in the survey results for these participants.

4.2.2.3. Shifts in perception of nature

This theme shows how the guided forest bathing session provoked shifts in perception of

nature and specifically of trees. This was primarily among interviewees without previous

experience in guided forest bathing. The shift was attributed to the symbolism and

terminology used by the guide which contributed to seeing the animateness of the forest. As

one interviewee put it: “I think I will look at the trees more like … Look up at their canopy,

put on a smile and take my hat off to them… when I go by on my walk in the forest" [P.07n].

In general, hearing the guide and interacting with trees as living beings rather than just objects

seemed to trigger feelings of awe and respect and new perspectives on HNC in the

interviewees:

32

“It gives a perspective that there is a life cycle going on, which is separate from my

job and everyday life. It is there no matter what I do. I think there is a humility in that,

somehow. To have contact with that part that I do not have contact with on a daily

basis in the same way” [P.12e].

“I think [guided forest bathing] can help me to feel less like a stranger… and instead

to feel more with the forest, in a way. Like, I'm an animal too.” [P.10n]

This thought provocation and subtle shift in perception of nature may therefore explain the

significant increase in the ability of HNC “being one with nature” found in the survey results.

4.2.2.4. Rediscovery of nature

The interviewees, especially those with previous experience, expressed that the guided forest

bathing session became a rediscovery of nature rather than a discovery of something

completely new. The session made them realize how much being in nature positively affects

them both physically and mentally, and how they wish to spend more time in nature: “My

God, how nice that I spent time in the forest this weekend. I want to do it again. I want more”

[P.16e]. A revived awe and fascination for nature was evident by several interviewees with

previous experience of guided forest bathing who eagerly highlighted features and details that

they remember from the session, for example: “I found a mountain that had this amazing

moss! … It was a fantastic moss that you could kind of pat on that was a bit like… hairy …

with a cool sound when you hit it. God, I would never have discovered that if I had not been

to a guided forest bathing session” [P.16e].

4.2.2.5. Human impact on nature

Several interviewees, regardless of previous experience of guided forest bathing, mentioned

noticing impacts on the forests by human activity, primarily littering and very trampled paths.

In most cases, this was not due to the guide making them aware of it. However, in general, the

interviewees expressed that the session had not impacted how they think or feel about

environmental issues or human impact on nature. Rather, responses reveal a clear pre-existing

environmental concern, as illustrated by these quotes:

“Sometimes I wish it was untouched. I mean, if I go to Tyresö National Park, it's so

badly trampled… I can almost get a little angry, because it has almost been destroyed

just because the availability is too high.” [P.16e]

33

“We talked about the spruce bark beetle and of course it is a bit scary if we have a