Journal of Business Ethics (2022) 178:571–595

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04800-9

ORIGINAL PAPER

Corporate Accountability Towards Species Extinction Protection:

Insights from Ecologically Forward‑Thinking Companies

Lee Roberts1 · Monomita Nandy1 · Abeer Hassan2 · Suman Lodh3 · Ahmed A. Elamer1

Received: 8 September 2020 / Accepted: 18 March 2021 / Published online: 10 April 2021

© The Author(s) 2021

Abstract

This paper contributes to biodiversity and species extinction literature by examining the relationship between corporate

accountability in terms of species protection and factors affecting such accountability from forward-thinking companies.

We use triangulation of theories, namely deep ecology, legitimacy, and we introduce a new perspective to the stakeholder

theory that considers species as a ‘stakeholder’. Using Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML) regression, we examine a

sample of 200 Fortune Global companies over 3 years. Our results indicate significant positive relations between ecologically

conscious companies that are accountable for the protection of biodiversity and species extinction and external assurance,

environmental performance, partnerships with socially responsible organizations and awards for sustainable activities. Our

empirical results appear to be robust in controlling for possible endogeneities. Our findings contribute to the discussion on

the concern of species loss and habitat destruction in the context of corporate accountability, especially in responding to

the sixth mass extinction event and COVID-19 crisis. Our results can also guide the policymakers and stakeholders of the

financial market in better decision making.

Keywords Biodiversity · Species extinction · Deep ecology · Legitimacy · Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood ·

Stakeholders

Introduction

In recent years, policymakers, NGOs, academics, and com-

panies have devoted greater attention to the strategic impli-

cations of biodiversity loss and species extinction (hereafter

* Monomita Nandy

monomita.nandy@brunel.ac.uk

Lee Roberts

Lee.Roberts@brunel.ac.uk

Abeer Hassan

abeer.hassan@uws.ac.uk

Suman Lodh

s.lodh@mdx.ac.uk

Ahmed A. Elamer

ahmed.elamer@brunel.ac.uk

1 Brunel University London, Uxbridge UB8 3PH, UK

2 University of the West of Scotland, G226, Gardner Building,

Paisley PA1 2BE, UK

3 Middlesex University, The Burroughs, Hendon,

London NW4 4BT, UK

B/E). Yet, the relationship between corporate accountability1

in terms of species2 protection and factors affecting such

accountability (assurance, environmental performance,

country, partnerships, etc.) remains underexplored in

accounting and business literature (Atkins & Atkins, 2018;

Gaia & Jones, 2019; Reade et al., 2015). Biodiversity and

species extinction are part of wider global environmental

challenges facing humanity (Sobkowiak et al., 2020), with

the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),

specifically SDGs 14 and 153 the most recent call to action

1 In this paper, we refer to accountability as companies’ disclosure

on how to protect species to eliminate biodiversity loss in the future.

2 We identify species as the variety of plants (flora) and animals

(fauna) that provide balanced ecosystems essential for human survival

and welfare (Sandifer et al., 2015).

3 We refer to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs) 14 ‘Life below water—Conserve and sustainably use the

oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development’ and

SDG 15 ‘Life on Land—Protect, restore and promote sustainable use

of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertifi-

cation and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss’.

1 3 Vol.:(0123456789)

572

L. Roberts et al.

to develop solutions and protect the planet from further bio-

diversity loss4 (UN, 2020a).

It is acknowledged that business activities are recognized

as one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss and species

extinction (Hassan et al., 2020a; Maroun & Atkins, 2018;

Roberts et al., 2020a). Thus, we contribute to the extant lit-

erature and examine how the accountability of ecologically

conscious/forward-thinking5 (hereafter EC/FT) companies

can prevent further species and biodiversity loss in the future

and align with SDGs 14 and 15. Our motivation for this

paper is to respond to the recent calls to contribute to devel-

oping solutions for the B/E crisis (Gibassier et al., 2020).

This research is significantly timely, as experts suggest that

pandemics such as COVID-19 are a result of habitat loss,

wildlife trafficking, and humanity’s destruction of biodiver-

sity (Ceballos et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2020). Potentially,

COVID-19 may not be an isolated pandemic; therefore, there

must be a seismic shift from companies in valuing and pro-

tecting nature. In addition, biodiversity loss is now recog-

nized as one of the top five global risks (WEF, 2020)6 with

severe implications for society if transformational changes

are not made (WHO, 2020).

The above discussion motivates us to examine how EC/

FT companies that initiated efforts in conserving and pro-

tecting species before the current pandemic can influence

companies’ reporting in the post-COVID-19 era. Therefore,

we would expect corporates to consciously make tremen-

dous efforts in conserving biodiversity and protecting spe-

cies from extinction as companies realize their dependence

on nature. Thus, our findings can guide and encourage com-

panies to improve future reporting to achieve SDGs 14 and

15 targets by 2030, as “accounting academics can and should

play a substantial role helping embed policy and action at

an organizatinal level in a way that contributes towards the

4 We define biodiversity loss as the decline of the infrastructure of

ecosystems caused by the abuse from human and business overex-

ploitation (Hassan et al., 2020a; Roberts et al., 2020a).

5 We define ecologically conscious or forward-thinking companies as

those companies that realize the importance of biodiversity and spe-

cies extinction and have provided disclosure on how to protect both

biodiversity and species before the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, we

use ecologically conscious and forward-thinking companies inter-

changeably.

6 The recent Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform and Ecosys-

tem Services Global Assessment Report (IPBES, 2019) outlines one

million species which are under threat from extinction within dec-

ades if transformational changes are not made. Such species decline

challenges organizational viability as they are dependent on healthy

ecosystems providing natural assets for sustainable economic activity

(European Business and Biodiversity Campaign, 2020). Although no

monetary value can be placed on natural assets (Jones & Solomon,

2013), the value ecosystems provide in resources is estimated to be

between $125 to $145 trillion per year (Costanza et al., 2014), high-

lighting the intrinsic worth of natural resources to businesses.

achievement of the SDGs” (Bebbington & Unerman, 2018,

p. 2). The findings of this study will extend the existing

academic findings on emerging issues about B/E account-

ing (e.g., Adler et al., 2018; Atkins & Maroun, 2018; Has-

san et al., 2020a, b). The combination of the theoretical

framework along with robust empirical findings will assist

academics in advancing this stream of emerging literature,

and help companies to understand how to consider various

factors to be sustainable in the future. Additionally, this

will give a clear indication to regulators about the changes

required to motivate companies for preventing further B/E

loss.

Furthermore, extant B/E literature is limited. Specifically,

most studies employed one theoretical construct to explain

the companies’ accountability towards the extinction of spe-

cies, which contains several caveats. We respond to the pre-

vious call (Gaia & Jones, 2019) that a single theory is not

adequate in explaining B/E disclosure, by adopting a trian-

gulation of deep ecology, legitimacy, and stakeholder theo-

ries. By applying deep ecology and stakeholder concepts, we

support the argument of Roberts et al. (2020b), who suggest

that species are of fundamental value to business survival

and are main stakeholders in society; therefore, companies

should consider species as an important stakeholder of their

business. Legitimacy theory can explain how a company’s

legitimacy can be achieved by considering species as impor-

tant as other stakeholders in company operations. The com-

prehensive theoretical model allows us to contribute to the

limitation of the extant literature theoretically. To date, semi-

nal contributions in literature stimulate the development of

species protection by providing extinction accounting frame-

works (Atkins & Maroun, 2018; Hassan et al., 2020b) and

examination of organizational accountability for biodiversity

(Adler et al., 2018; Maroun et al., 2018). Emerging studies

(e.g., Raar et al., 2020) open a debate on how the incorpora-

tion of biodiversity accountability can assist in the preven-

tion of further species loss. Flowing from extant literature,

this paper builds on these bodies of work to empirically

examine company disclosure on species and what factors

motivate relationships for such disclosure. This research

responds to Roberts et al. (2020b) who identify the urgency

in B/E literature for the examination of species protection

disclosure to extend knowledge in the field and contribute

to advancing solutions.

Based on the above discussion, the objective of this paper

is to investigate factors affecting the relationship between cor-

porate accountability and species protection of EC/FT compa-

nies. We believe that providing disclosure on species protec-

tion enhances stakeholders’ trust and accountability (Hassan

et al., 2020b). To empirically test our idea, this study uses a

sample of the top 200 companies from Fortune Global in 2012,

2014, and 2016, to highlight how EC/FT companies reported

on the protection of species before the recent pandemic and

13

Corporate Accountability Towards Species Extinction Protection: Insights from Ecologically…

573

provide a springboard to develop solutions after the pandemic.

These companies directly or indirectly make significant use

of ecosystems, and therefore gain the most public attention

(Adler et al., 2018; Hassan et al., 2020b). Our justification is to

present how EC/FT companies report on conserving and pro-

tecting biodiversity and species, which could influence report-

ing in the recent and coming years. By applying advanced

empirical analysis, we find that companies that are disclosing

responsibly about species and are actively protecting against

extinction, for which these companies are recognized by

awards, have extended partnerships with species protection

organizations and are also getting favorable assurance for their

business.

The study makes several contributions to the extant B/E

literature. First, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have

examined the relationship between species disclosed by organ-

izations and its determinant factors. Therefore, this paper aims

to close this gap by contributing to the extant B/E literature

and demonstrate how EC/FT companies are displaying signifi-

cant efforts on species protection and restoring habitats. Sec-

ond, theoretically, we adopt a triangulation of theories; deep

ecology, legitimacy and stakeholder theories. We also suggest

that species should be considered as one of the main stake-

holders’ categories in addition to customers, employees, etc.,

as businesses have a two-way relationship with biodiversity

and species, including both the impact of companies on bio-

diversity and the impact of biodiversity on companies (Adler

et al., 2018). Third, our paper has an empirical contribution.

Instead of adopting OLS regression that is commonly used by

previous studies (Adler et al., 2018; Hassan et al., 2020b), we

test and create Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML)

regression with a multi-way fixed effects model. We believe

the PPML model is more relevant to explore the relationship

between the species disclosed by companies and determinant

factors because our disclosure index includes positive count

values only. Fourth, our study has a number of implications for

policymakers. The proposed empirical model and theoretical

framework in this study will allow policymakers to process a

post-2020 framework to reshape the global relation with nature

(UN, 2020b) and support the United initiatives and achieve the

SDGs 14 and 15 objectives. The study will guide decision-

makers to understand how disclosure of species protection by

companies can assist society to mitigate further B/E loss in

the future. Finally, our paper responds to recent calls (Gaia

& Jones, 2019; Lambooy et al., 2018) to develop solutions by

showing how the potential for reporting for B/E can mitigate

the further risk of ecological collapse.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: the next sec-

tion covers the literature review. Section three discusses the

theoretical literature. Section four discusses empirical litera-

ture and hypothesis development. Section five illustrates the

research design. Section six presents the empirical analysis.

Finally, a discussion of findings and limitations is exhibited

in the last section.

Corporate Accountability, Ecology,

and Species Extinction Protection Around

the World

Research on corporate accountability for B/E is in its

infancy (Addison et al., 2019; Adler et al., 2017) and is

an emerging strand of literature (Haque & Jones, 2020).

To date, academics have been relatively silent on examin-

ing the role of companies in conserving biodiversity and

species protection (Adler et al., 2018) and thus, there is

a huge call for company awareness from stakeholders of

businesses (Hassan et al., 2020b). To provide context,

B/E accounting emerges from biodiversity reporting and

this extends to include the ‘extinction’ element due to the

severity of the decline of nature (Atkins & Maroun, 2018).

The early seeds of biodiversity reporting were set by Jones

(1996) who suggested that organizations are stewards of

natural capital and have a moral duty to protect and to

publicly disclose their efforts (Atkins et al., 2014). Early

empirical studies began to explore reporting of compa-

nies on biodiversity issues at country level (Boiral, 2016;

Rimmel & Jonäll, 2013; van Liempd & Busch, 2013)

and industry level (Adler et al., 2017; Boiral & Heras-

Saizarbitoria, 2017). Prior studies are consistent in finding

that most companies provide poor disclosure, vague state-

ments, and are generally unimpressive with their efforts to

manage and protect biodiversity. Literature suggests that

companies fail to recognize the risk of biodiversity loss,

leaving them unconvinced that conservation warrants their

efforts (Skouloudis et al., 2019). It seems to be only when

endeavors provide rewards of stakeholder impressions or

reputational advantage that companies will pay attention

(Bhattacharya & Managi, 2013; Hassan et al., 2020b).

It is argued that biodiversity reporting on its own is

insufficient (Atkins & Maroun, 2018; King & Atkins,

2016). The widely adopted Global Reporting Initiative

(GRI) standards only make some reference to biodiversity

(Jones & Solomon, 2013), and therefore company account-

ability is limited. Companies following the GRI frame-

work are found to be indulging in impression management

(Gray & Milne, 2018; Solomon et al., 2013), with a lack of

consistent, transparent reporting. Atkins and Atkins (2018)

suggest that continuing to report in this method will lead

to a fossil record of species. Haque and Jones (2020) sup-

port the previous arguments and mention that companies

are using GRI standards as a mechanism to refer to bio-

diversity, providing symbolic statements and failing to

provide clarity on operational impact to natural capital.

13

574

L. Roberts et al.

In response to the limitation mentioned above, extinc-

tion accounting evolves from biodiversity reporting by

critically recognizing the need to address the current

extinction crisis (Atkins & Maroun, 2018). Incorporating

GRI biodiversity principles, extinction accounting aims

to promote change by companies and reverse species loss

(Atkins & Atkins, 2018; King & Atkins, 2016), providing

companies opportunity to disclose how they are acting to

prevent further extinctions (Hassan et al., 2020b).

The framework provides the opportunity to include nar-

rative detail and self-reflection, and to further articulate

extinction prevention measures with the hope that this

will lead to changes in company behavior (Hassan et al.,

2020b). Furthermore, companies should seek to consolidate

numerical data and narrative and pictorial evidence to com-

prehensively communicate conservation efforts (Atkins &

Maroun, 2020). Atkins (2020) argues that companies should

be integrating extinction accounting into annual reports to

trigger change and would have to “assess the populations

of threatened species living near their operations; work

out whether their business puts them at risk; come up with

plans to protect them; and explain them to investors”. Stud-

ies from extinction accounting give evidence of a genuine

concern for nature and represent the need for compassion

for species (Atkins et al., 2018; Buchling & Maroun, 2018);

they support the idea that companies begin to acknowledge

their dependence on natural capital. Motivated by extinction

concern, evidence of species names emerges in corporate

reports (Adler et al., 2018; Atkins et al., 2014). However,

an argument builds that certain alluring or desirable species

may attract more attention from companies than others, as

Weir (2018) observed that mammals and birds warranted

greater conservation efforts than insects and invertebrates.

Atkins et al. (2014) reinforce this theory, reporting that

favoritism may be shown towards certain species, especially

species which are beneficial to humans.

Smith et al. (2019) found that the corporate motiva-

tion to engage in conservation efforts is unclear. However,

the existing studies assist companies to recognize that the

threat of extinction is a material risk (Addison et al., 2019).

Global policymakers are also taking the initiative to encour-

age companies to be accountable towards the extinction of

species. For example, The Natural Capital Coalition (2020)

urges companies to realize that their success is driven by

ecosystems; the loss of any species to extinction is devas-

tating, but species which provide such intrinsic worth to

industries is frightening.7 Indeed, the global Aichi targets

7 For example, crop production which has an estimated annual

valuation of $577 billion, is under threat from pollination loss and

bee decline (The World Bank, 2020), threatening the food industry.

Approximately 70% of cancer drugs are derived from plant spe-

cies, consequently threatening the pharmaceutical industry (PWC &

WWF, 2020).

of the ‘Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020’ have been

considered a failure as biodiversity decline is accelerating at

an unprecedented rate, with humanity’s legacy of biodiver-

sity at a crossroads for future generations (CBD, 2020). The

most recent call to action is the United Nations SDG targets

‘The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. Global

governments have agreed on a vision of ‘Living in harmony

with nature’ by 2050, and it is imperative lessons are learned

from the past decade if the SDGs are to be met. The UN

Biodiversity Conference in September 2020 emphasizes the

need for “Urgent action on biodiversity across all sectors

and from all actors” to meet the SDG target of 2030 (CBD,

2020). Furthermore, the post-2020 biodiversity initiatives

must be achieved, or humanity could potentially face future

pandemics.

The current COVID-19 crisis provides forewarning to

further encroachment between natural capital and humans

that can have detrimental impacts (Carrington, 2020). Cor-

porates must make transformational changes to restore their

relationship with nature and engage in sincere stewardship

of natural capital, as it is their moral duty to protect future

generations (Gaia & Jones, 2019). Turning a blind eye to

warning signs could be catastrophic for business prosper-

ity and survival. There is no extensive literature to explain

the accountability of companies towards species extinction.

Therefore, in this study, we discuss how the disclosure of

species by global companies can assist them in achieving

environmental awards, gain assurance from Big 4,8 and

allow companies to expand biodiversity partnerships lead-

ing to a financially sustainable company. The findings of

this study will be an example for stakeholders of companies

and will encourage academics to extend the studies on B/E

to assist companies to be more accountable towards B/E.

Furthermore, to meet SDGs 14 and 15, we offer a solution

that can assist in preventing further decline by advocating

that companies transform their reporting practice to include

information on their efforts to protect biodiversity and

species.

Theoretical Literature Review

Prior B/E research applies various theories to explain com-

pany viewpoints including impression management (Boiral,

2016), greenwashing (Hassan et al., 2020b), and legitimacy

(Adler et al., 2017; Bhattacharyya & Yang, 2019). However,

we observe that companies have not done enough to protect

species from extinction, and, as experts explain, it may be

that this is one of the reasons for zoonotic disease spillover

8 Big4—one of the big four accounting firms: Deloitte, Ernst &

Young, KPMG, PwC.

13

Corporate Accountability Towards Species Extinction Protection: Insights from Ecologically…

575

such as COVID-19 (Ceballos et al., 2020). Lack of a com-

prehensive theoretical model cannot motivate companies

to identify a strategy for species protection. Therefore, we

introduce a triangulation of theories, namely deep ecology,

legitimacy, and stakeholder theories. Deep ecologists are of

the view that nature has intrinsic value, and all nonhuman

life should be preserved (Naess, 1989, 2008), thus rejecting

anthropocentric shallow ecology, which places humans of

most importance, believing nature has value because of what

it contributes to human satisfaction (Callicot, 1990, 1994;

Thompson & Barton, 1994). Deep-ecologists debate whether

environmental and extinction crises are human-induced

(Samkin et al., 2014) and support the suggestion that the

crisis is the result of dominating anthropocentric bias in cor-

porate behavior (Atkins et al., 2014). Absolute deep ecol-

ogy would reject business use of natural assets as a com-

modity. However, to mitigate corporate financial risk and

prevent societal collapse, a middle ground must be reached.

Companies must consider embedding an ecological culture

and stewardship (Jones, 1996) by protecting and investing

in nature. For example, Gaia and Jones (2019) found that

elements of deep ecology must be ethically rooted to enable

a sustainable society. Similarly, Samkin et al. (2014) found

deep ecology embedded in biodiversity disclosures and men-

tion that the approach requires a long-term commitment.

Embracing deep ecology is not to put a financial value on

species as this would be refuted by deep-ecologists; rather,

companies must evaluate their behavior and engage in a

balanced perspective to mitigate the risk of financial loss,

together with responsibly protecting species and habitats.

The relationship with nature must be realigned and eliminate

the arrogant profit-seeking objectives, which have driven us

to a planetary emergency (Gray & Milne, 2018).

Empirical evidence considers corporates to be rife in

legitimizing activities (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2017;

Cho & Patten, 2007; Milne & Gray, 2013; Patten, 2002).

Extant literature considers B/E accounting as a continua-

tion of corporate social responsibility (CSR) research into

corporate disclosure practices (Bebbington & Larrinaga,

2014; Hassan et al., 2020b). Legitimacy theory is one of the

most applied theories to explain the increasing CSR report-

ing over the past two decades (Hassan & Guo, 2017) and it

“involves the selective disclosure of positive actions result-

ing in misleading and biased reporting” (Mahoney et al.,

2013, p. 352). Extant literature uses legitimacy theory to

explain that dishonest companies misreport their CSR efforts

to capitalize on their face value to influence stakeholders’

perceptions and gain legitimacy (Lyon & Maxwell, 2011;

Zijl et al., 2017).

Adler et al. (2018) argue that biodiversity and threat-

ened species information is provided in order to fulfil the

desires and expectations of stakeholders. Bhattacharyya

and Yang (2019) specifically note that considering the

current planetary emergency, for businesses to gain soci-

etal legitimacy, they must increase biodiversity disclosure.

Lewis (2016) explains that legitimacy is a practice that is

deceivingly used to endorse that organizations’ policies

or practices are environmentally friendly, when arguably

they are not. Patten (2015), for example, explains that an

organization with specific environmental adversity intensi-

fies the extent of CSR reporting to signal to stakeholders

that the organization is addressing the concern. This con-

tinues a tradition of impression management-oriented lit-

erature in environmental accounting (Hassan et al., 2020a,

b). This research argues that companies provide disclosure

to legitimize companies’ concerns for B/E issues (Adler

et al., 2018; Cho et al., 2015a; Lyon & Maxwell, 2011).

As the species extinction crisis intensifies, it can be

expected that companies must meet external pressures

(Rimmel & Jonäll, 2013) and enhance reputation to main-

tain their “licence to operate” (Adler et al., 2017, p. 1714).

Research highlights that stakeholder and legitimacy theo-

ries overlap in social and environmental studies (Deegan,

2002; Gaia & Jones, 2017, 2019). Stakeholder theory has

been used to explain the needs and expectations of human

groups and individuals affected by the company (Boiral

& Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2017; Gaia & Jones, 2019). The-

oretically, we recognize a limitation within stakeholder

literature that prior studies have failed to recognize or

explain for the prevention of further species loss. Roberts

et al. (2020b) argue that species should be included as a

main stakeholder with the established groups of employ-

ees, NGOs, government agencies, environmental groups,

and customers (Jones, 1995; Schaltegger et al., 2017). We

believe that for deep ecology to be embedded in corporate

strategy, species of flora and fauna should be considered

as one of the main stakeholders’ categories, discarding

human hierarchy, for companies to protect and restore

species and their habitats. In this vein, we focus on a tri-

angulation of deep ecology, legitimacy, and stakeholder

theories, which can explain the relationship between spe-

cies numbers and determinant factors. We recognize that

corporates may be disclosing species-specific informa-

tion for legitimizing purposes, but we are also hopeful

that those companies who are disclosing species numbers

have started to realize the intrinsic worth of natural capital

and are consequently embedding ecological culture and

displaying a genuine concern for the extinction crisis by

identifying species as stakeholders. We hope that provid-

ing disclosure on species protection will be the new norm

for other companies to follow. Societal health is under-

pinned by nature (Roberts et al., 2020a); we expect that by

application of the triangulation of theories, we can assist

companies to explain the underlying motivation to reform

B/E impact, which will reduce potential future pandemics

(Ceballos et al., 2020).

13

576

L. Roberts et al.

Empirical Literature Review and Hypotheses

Development

B/E accounting is considered as an extension of CSR (Beb-

bington & Larrinaga, 2014; Bhattacharyya & Yang, 2019;

Hassan et al., 2020b). From the existing literature, we

identified that the assurance by leading assurance provid-

ers, presence of partnerships, environmental performance,

and environmental award are some important factors that

will assist the stakeholders to assess the accountability of

the companies towards nature. In the following section, we

discuss these factors in detail to develop the hypotheses

related to the research question, which is supported by the

comprehensive theoretical model explained previously.

Species and Assurance

Sustainability reporting is established in mainstream

practice to meet the needs of societal expectations (Junior

et al., 2014; Kolk & Perego, 2010). However, it is argued

in the literature that the reliability and quality of informa-

tion falls short (Cho et al., 2015a). Boiral et al. (2018)

imply that information can be biased and reporting by

companies is used as a window-dressing activity (Boiral,

2016), and thus, the credibility of information is ques-

tioned (Gray, 2010). To enhance the quality and credibility

of sustainable reporting in literature, we find that compa-

nies prefer to use third-party assurance from accounting

firms (Maroun, 2018). Involvement of third parties can

increase the confidence of the stakeholders in disclosure

(Simnettt et al., 2009). Human stakeholders perceive the

professionally audited reports from the external assurance

provider as a confident and legitimate report of the com-

pany performance (Cho et al., 2015a).

Because of the immense presence of independence in

the report prepared by the external assurance provider,

companies who are under public pressure due to poor per-

formance may prefer to seek external independent assur-

ance to indicate a better performance to the stakeholders

(Boiral et al., 2018; Maroun, 2018). But external assurance

is also required to identify which companies are better

in addressing the B/E risk, which is prominent (IPBES,

2019) and related to human behavior. The external assur-

ance report can help the stakeholders to understand how

the companies are following deep ecology principles by

engaging in the stewardship of natural capital (Bhattacha-

ryya & Yang, 2019). Legitimacy theory has been domi-

nant in the social and environmental accounting litera-

ture (Belal & Owen, 2015; Giordano-Spring et al., 2015).

Many studies (e.g., Ball & Craig, 2010; Cho, 2009; Cho &

Patten, 2007; Hassan & Guo, 2017; Patten, 2015; Tilling

& Tilt, 2010) empirically examine legitimacy theory and

support the argument that companies voluntarily provide

environmental information to gain legitimacy. The theory

also predicts that organizations who are more likely to

be subject to public pressure and legitimacy threats due

to negative CSR performance may hire third parties to

provide assurance to indicate favorable performance

(Boiral, 2016; Cho et al., 2014; Maroun, 2018). Conse-

quently, independent third-party assurance can help to

deflect attention from negative B/E performance, lessen

legitimacy risks, and install improved confidence among

stakeholders (Gürtürk & Hahn, 2016; Perego & Kolk,

2012). More specifically, these firms actively hire third

parties that provide limited assurance to portray that the

B/E information released in CSR reports is credible, in

order to improve stakeholders’ confidence and enhance

corporate reputation and perceived legitimacy (Cho et al.,

2014; Odriozola & Baraibar-Diez, 2017). Nevertheless,

as companies must comply with reporting standards, they

may prefer the ‘low-quality assurance’ with less scrutiny,

and thus they have opportunity to dissociate their revealed

from their actual performance.

However, it is also evident in the literature that assur-

ance providers deliver cautious rhetoric, failing to explic-

itly address issues around the report on biodiversity (Boiral

et al., 2019). Companies may prefer to buy less scrutinized

‘low-quality’ assurance options to deflect from their poor

performance (Hassan et al., 2020b), and are expected to

select limited assurance (Braam & Peeters, 2018) outside

of the accounting profession to focus on selected sec-

tions of the performance. In post-pandemic reporting, we

expect companies to engage in stewardship of protecting

species and habitats, embedding a deep-ecological culture

by regarding species as a main stakeholder. In the future,

assurance providers will scrutinize the company impact

on biodiversity. Our motivation for this hypothesis is to

extend existing literature which finds a positive relation

between B/E disclosure and external assurance (Hassan

et al., 2020b). Therefore, we examine whether external

assurance is an influencing factor in protecting species.

By applying deep ecology and stakeholder theory, compa-

nies are expected to commit to protecting species (Samkin

et al., 2014) and valuing them as stakeholders. The contra-

dictory findings of the importance of external assurance

motivated us to examine the influence of external assur-

ance on companies’ accountability towards the extinction

of species. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 There is a positive relationship between the

number of species and buying assurance from an external

assurance provider.

13

Corporate Accountability Towards Species Extinction Protection: Insights from Ecologically…

577

Species and Environmental Performance

Legitimacy theory helps to explain why companies with

poor environmental performance have higher environmental

scores (Mahoney et al., 2013). In the literature, we find that

the more extensive disclosure companies provide, the more

the firm’s reputation is enhanced (Cho & Patten, 2007; Cho

et al., 2012). Poor performers are anticipated to disclose in

order to gain legitimacy and enhance societal perception

(Clarkson et al., 2008). Hassan et al. (2020b) classify com-

panies into poor and better performers and find companies

with poor environmental performance disclose more and

offer justification to defend legitimacy. Based on this argu-

ment, we expect that poor performers will disclose more

species information to maintain legitimacy, and as a result,

the companies can be more accountable in mitigating the

extinction of species. If species are accepted as one of the

main stakeholders, we expect EC/FT companies to propose

long-term value creation and suppress demand on natural

capital, committing to achieving SDGs 14 and 15. Our moti-

vation is to extend B/E literature (Hassan et al., 2020b) and

contribute to it by empirically examining, in support with

legitimacy theory, the relationship between species and poor

environmental performers. Thus, we propose the following

hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 There is a positive relationship between the

number of species and poor performers.

Species and Environmental Award

Gaining an environmental award is an excellent way of dis-

playing positive practices to stakeholders (Cho et al., 2015b;

Deegan, 2002), and motivates other companies to disclose

CSR practices (Hassan & Ibrahim, 2012). Acquiring awards

can show the true commitment of the company to natural

capital and confirm their deep ecological perspective (Clark-

son et al., 2008). Such awards influence investors to make a

positive decision about the company, which leads to favora-

ble future financial performance (Clarkson et al., 2011).

Prior B/E literature suggests that companies should report

on prizes and awards relating to conservation efforts (van

Liempd & Busch, 2013). Awards provide an opportunity to

signal genuine concern for nature (Adler et al., 2018; Atkins

et al., 2014) and showcase efforts. Hassan et al. (2020b)

exclusively find a positive association between B/E disclo-

sure and companies gaining environmental awards. Based on

this discussion, our motivation is to extend extant literature

and expect companies who disclose species to gain environ-

mental awards, and by doing so, deep ecology supports that

they have considered species as stakeholders (Roberts et al.,

2020b) in their reporting in order to address the extinction

crisis responsibly.

Hypothesis 3 There is a positive relationship between the

number of species and getting an environmental award.

Species and Partnerships

Prior literature finds a positive relationship between B/E

disclosure and partnership engagement (Adler et al., 2018;

Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2017; Hassan et al., 2020b).

Here, partnership refers to when a company discloses a rela-

tionship with at least one conservation or wildlife organi-

zation. This can be viewed as a display of good corporate

practice (Adler et al., 2018) and a means of seeking pub-

lic trust (Deegan, 2002). Collaborating with organizations

such as WWF (World Wildlife Fund) or IUCN (International

Union for Conservation of Nature) can help companies to

engage in conservation efforts, and companies are therefore

more likely to minimize the extinction crisis (Adler et al.,

2018). Partnership engagement will motivate companies to

consider species as stakeholders (Atkins et al., 2018; Buch-

ling & Maroun, 2018; Zhao & Atkins, 2018). By supporting

this concept, EC/FT companies can commit to achieving

SDGs 14 and 15 and can align with long-term value crea-

tion. Thus, our motivation is to enhance B/E literature (Adler

et al., 2018; Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2017) by empiri-

cally examining the relationship with species and partner-

ship engagement. Theoretically, deep ecology perspective

and regarding species as stakeholders, demonstrates that

companies are preserving nature (Atkins et al., 2018) and

showing genuine concern for the B/E crises. Thus, we expect

that companies which engage in partnerships will disclose

more species.

Hypothesis 4 There is a positive relationship between

the number of species and companies who engage in

partnerships.

Research Design

Sample Selection

The sample for this research consists of the top 200 compa-

nies from the Fortune Global list of 2016. Purposefully, we

considered these companies as they are typically leaders in

CSR (KPMG, 2017), make significant use of ecosystems,

and therefore gain the most public attention (Adler et al.,

2018; Hassan et al., 2020b). These companies represent a

variety of industries exposed to different levels of biodi-

versity risk (Addison et al., 2019; Bhattacharya & Managi,

2013) from diverse geographic locations (Hassan et al.,

2020b). The top 200 companies are selected from the For-

tune Global 500 list as literature supports that the remaining

companies rarely disclose biodiversity information (Adler

13

578

L. Roberts et al.

et al., 2018; Hassan et al., 2020b). The investigation period

is 3 years: namely, 2012, 2014, and 2016, as one of the vari-

ables, environmental performance, is calculated every 2

years. Corporate annual and sustainability reports are down-

loaded from company websites. Sustainability reports can

be referred to as environmental, corporate social responsi-

bility, citizenship, or such reports. Where these reports are

missing, we manually collected relevant information from

the annual reports. Following prior studies (Addison et al.,

2019; Adler et al., 2017), websites were not included in the

search. In total, 600 annual and sustainability reports were

downloaded (which are accessible on their corporate web

pages). After controlling for an outlier, our final sample

comprised of 599 companies. Following prior studies (Adler

et al., 2018), we used content analysis, and by searching key-

words,9 we counted for species information. Keyword search

and manual collection are followed in this paper to identify

companies from 22 countries10 and 19 sectors.11

Research Variables

Dependent Variable: Number of Species

The number of species count was comprised of species

numbers presented in quantitative terms or by naming in

qualitative terms. A manual count of all species disclosed on

reports were collected and recorded. The number of species

counted was protected or conserved or noted as threatened

with extinction by the company. Where companies disclosed

a group of species, for example, 10 birds, we counted these

as 10 species and so on. In the counting of species, duplicate

references were eliminated; in other words, species referred

to on more than one occasion were counted once.

9 The 28 keywords are "Extinct", "Extinction", "EN11", "EN12",

‘EN13", "EN14", "Wildlife", "Habitat", "Species", "Biodiversity",

"Biodiversity offset", "Forest", "Ecosystem", "Flora", "Fauna",

"Endangered", "Threatened", "Vulnerable", "Accident" (relating to

B/E), "Conservation", "Biological diversity", "Protected", "Floral/

Faunal wealth", "Rehabilitation", "Groundwater", "Marine", "Vegeta-

tion", "Wetlands" (Adler et al., 2018).

10 Countries are Australia (9), Brazil (12), China (120), France (45),

Germany (48), India (3), Italy (12), Japan (57), Luxembourg (3),

Malaysia (3), Mexico (6), Netherlands (12), Norway (3), Russia (12),

Singapore (3), South Korea (15), Spain (6), Switzerland (15), Taiwan

(3), Thailand (3), United Kingdom (24), and USA (186).

11 The 19 sectors are Aerospace (21), Apparel (3), Chemicals (6),

Energy (99), Construction (18), Financial (144), Food & Beverage

and Tobacco (15), Food & Drugs (33), Health care (30), Household

products (6), Industrial (18), Materials (12), Media (3), Motor Vehi-

cles and parts (48), Retails (21), Technology (42), Telecommunica-

tion (33), Transportation (15), and Wholesalers (33).

Independent Variables

We used assurance, environmental award, presence of part-

nerships, and environmental score as independent variables

(see Table 1). The environmental score was measured by the

environmental well-being score from the Sustainable Soci-

ety Foundations website (Adler et al., 2018; Hassan et al.,

2020b). The scores are available per country every 2 years

and following Hassan et al. (2020b), we classified the sample

into poor performers (score 0–2.9) and better performers

(score 3–5). The sample consisted of 290 poor performers

and 309 better performers.

Control Variables

For this research, we considered leverage, firm size, and rev-

enue as control variables. In addition, we used country-level

variables. Following Hassan et al. (2020b), we classified the

sample into developing and developed countries, according

to the United Nations classification. There are 177 develop-

ing and 422 developed firm-year observations in our sample.

The industry was controlled in the study and was classified

by risk exposure according to the three categories of the F

& C Asset Report (2004) risk level (red is high risk; amber

is medium risk and green is low risk).12 In accordance with

Hassan et al. (2020b), we grouped red and amber to “high

risk” classification, and green remained “low-risk” classifi-

cation. The total sample consisted of 219 high-risk firm-year

observations and 380 low-risk firm-year observations. Gov-

ernance indicators are widely used in multi-country studies

(Nguyen et al., 2015; Waldron et al., 2017) with empirical

evidence finding a positive correlation of company perfor-

mance with country-level governance (Luo et al., 2012).

Therefore, we added seven regularity governance level indi-

cators (see Table 1) developed by Kaufmann et al. (2011)

collected from the World Governance Indicator dataset. In

addition, we added World Development Indicators, like GDP

growth, inflation, the log of forest area, and C 02 emissions

(Spaiser et al., 2017; Stephan et al., 2015).

12 High-risk sectors (red zone) are Construction & Building Mate-

rials, Electricity, Food & Drug Retailers, Food Producers & Proces-

sors, Forestry & Paper, Leisure & Hotels, Mining, Oil & Gas, and

Utilities. Medium risk sectors (amber zone) are Beverages, Chemi-

cals, Financial Services, General Retailers, Household Goods &

Textiles, Personal Care & Household Products, Pharmaceuticals &

Biotech, Support Services, Tobacco, and Transport. Low risk sectors

(green zone) are Aerospace & Defence, Automobiles & Parts, Diver-

sified Industrials, Electronic & Electrical Equipment, Engineering

& Machinery, Health, Information Technology Hardware, Media &

Entertainment, Software & Computer Services, Steel & Other Metals,

and Telecom Services.

13

Corporate Accountability Towards Species Extinction Protection: Insights from Ecologically…

579

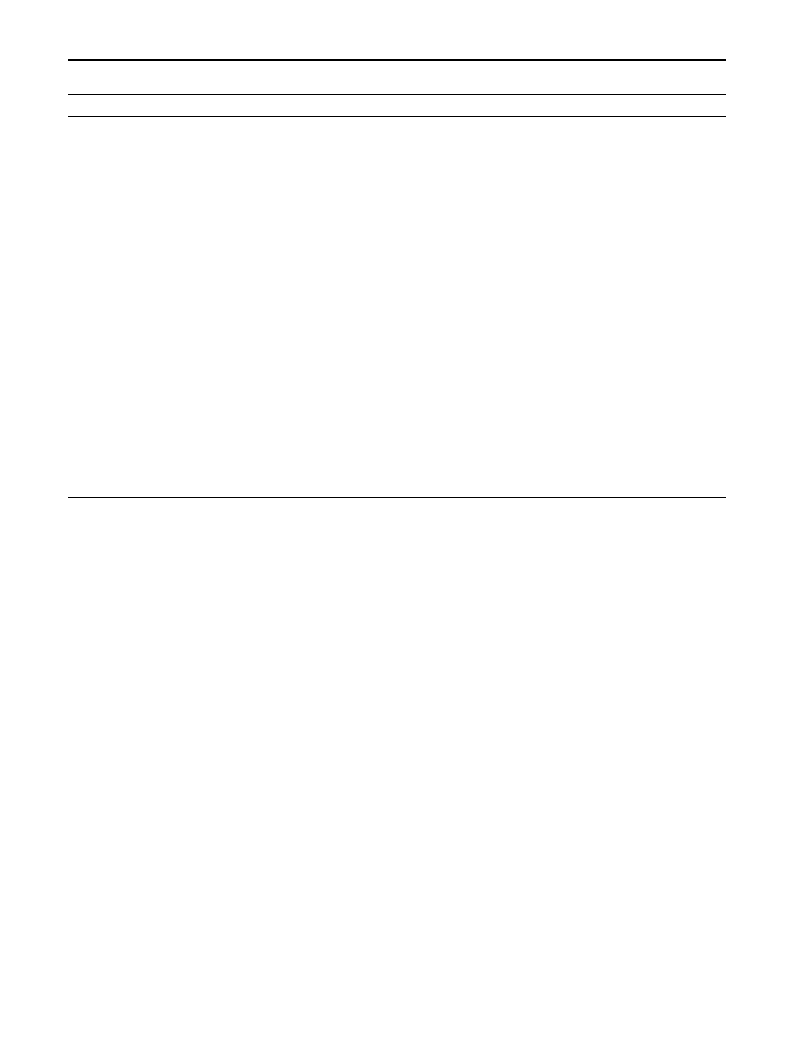

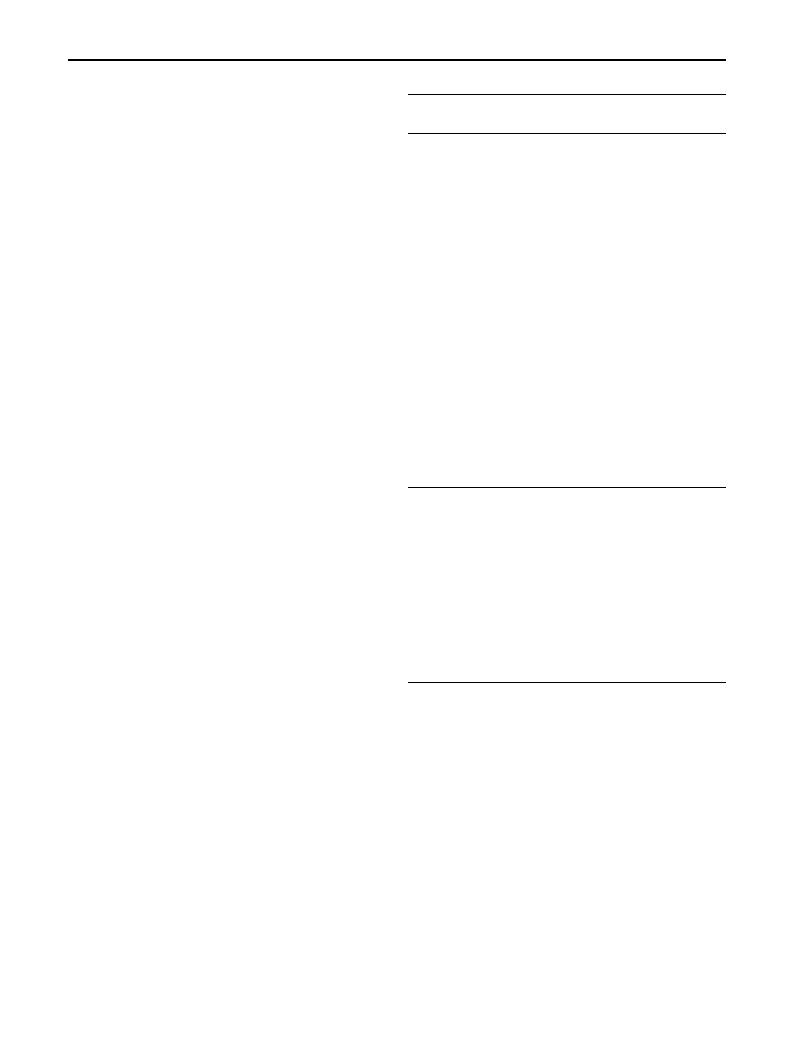

Table 1 Research variables

Definition and coding

Dependent variable Number of species—Total count of number of species collected from published annual reports

Independent variable Assurance—has a value of “1” if the company has assurance and a value of “0” if not. Data collected from published

annual reports

Assurance by Big4—Company has a value of “1” if assured by one of the big four accounting firms (KPMG, E&Y, PwC,

or Deloitte), and a value of “0” if not. Data collected from published annual reports

Environmental Award—value of “1” if award is given, value of “0” if not. Data collected from published annual reports

Environmental Score—Company is given a value of “1” if classified a ‘poor performer’ and a value of “0” if classified

a better performer. Data collected from Sustainable Society Foundation (SSF). Score is calculated every 2 years and is

used in prior studies (Adler et al., 2018; Hassan et al., 2020a, b)

Presence of Partnerships—Presence of biodiversity/wildlife partnerships, value of “1” given if one or more present, value

of “0” if none. Data collected from published annual reports

Control variables

Country—Value of “1” given if the country is classified as developed and a value of “0” if developing. Data retrieved

from United Nations website

Industry—Company has a value of “1” if classified as red/amber-risk zone, and a value of “0” if classified as a green risk-

zone. Classification recommended by F & C Asset Report (2004)

Governance—Is the average score of voice & accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regularity qual-

ity, rule of law, control of corruption and corruption index taken from Worldbank.org

GDP growth—(annual%)—World Development Indicator. Data collected from Worldbank.org

Inflation—GDP deflator (annual%) World Development Indicator. Data collected from Worldbank.org

Log (Forest area)—Forest areas (sq. km)—World development indicator. Data collected from Worldbank.org

CO2 emission—(metric tonnes per capita)—World Development Indicator. Data collected from Worldbank.org

Log (Revenue)—Data collected from published annual reports

Leverage—Total debt/total assets. Data collected from published annual reports

Firm size—Natural logarithm of total assets. Data collected from published annual reports

Empirical Results and Discussion

Summary Statistics

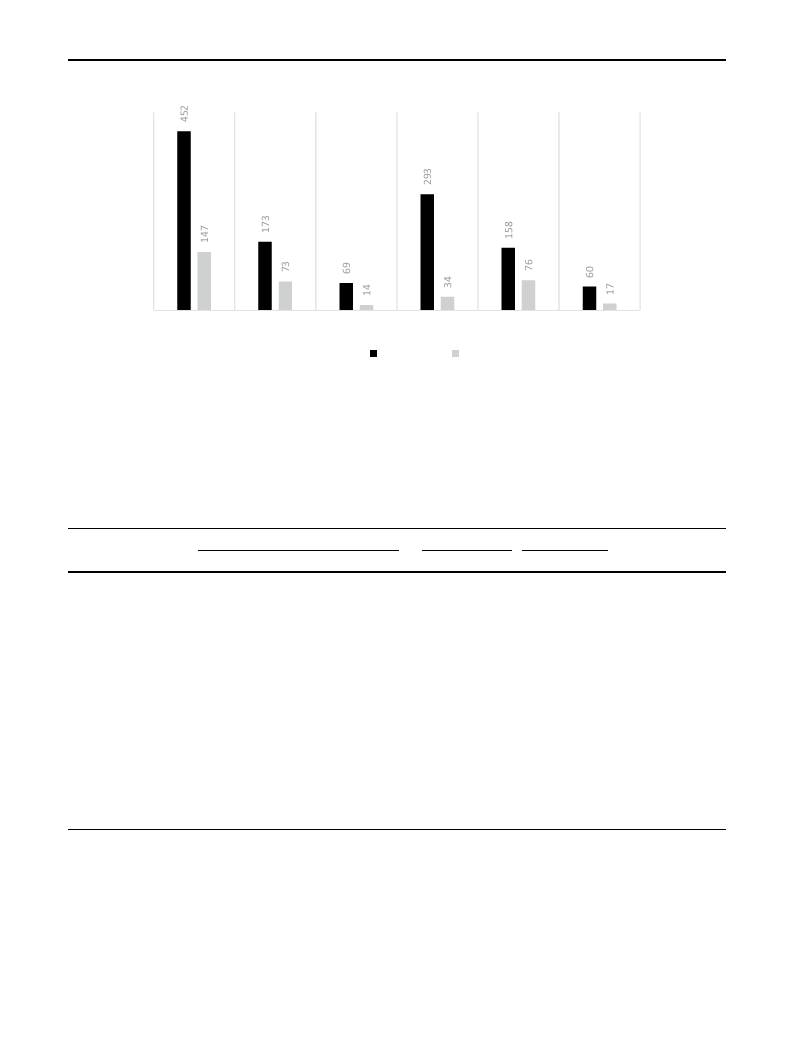

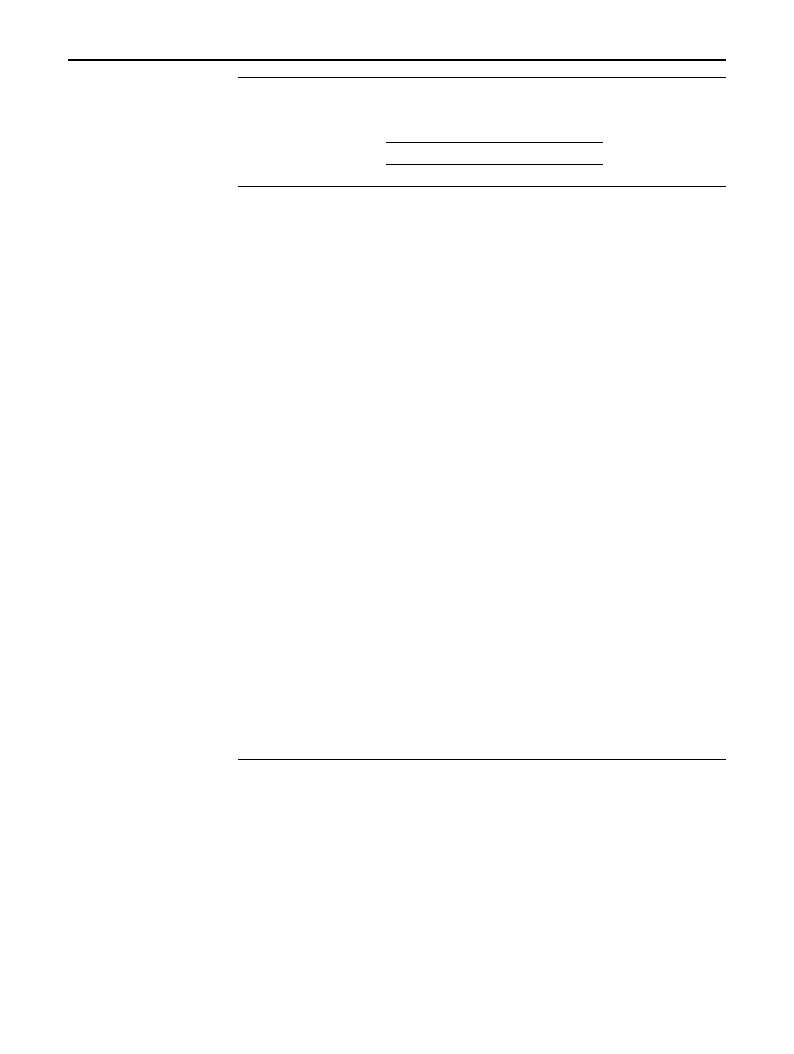

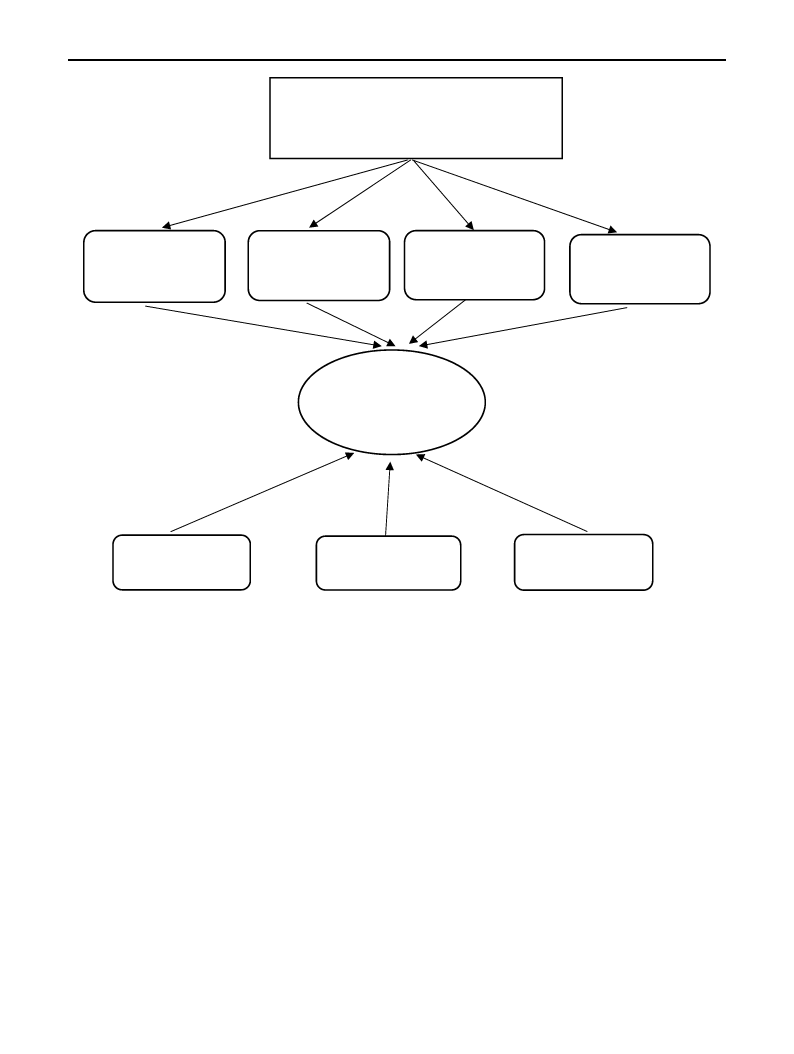

Our results show that 452 out of 599 reports (75%) failed

to disclose any species numbers (refer to Fig. 1). These

findings support prior literature (Adler et al., 2018; Bhat-

tacharya & Managi, 2013) and suggest a call for awareness

among companies (Rimmel & Jonäll, 2013; Hassan et al.,

2020b). However, the remaining EC/FT companies, 147

out of 599 (representing 25%), provided species numbers,

demonstrating ecological awareness by engaging in con-

servation efforts to protect and restore species and habi-

tats, valuing species as stakeholders. We found a slight

increase in species numbers over years which optimis-

tically displays a deep-ecological view with companies

being self-aware of the fundamental value of the planet

(Hassan et al., 2020b). The declaration of the SDGs in

2015 may also explain the increase. We acknowledge that

this is a small proportion of the sample. However, these

EC/FT companies provide seminal knowledge in establish-

ing relationships between species and developing solu-

tions to meet SDGs 14 and 15. These disclosures may be

a reporting exercise to manage impressions. However, we

expect post COVID-19 that there will be a seismic shift in

company reporting and committing to protecting nature,

and therefore justify the significance of our results.

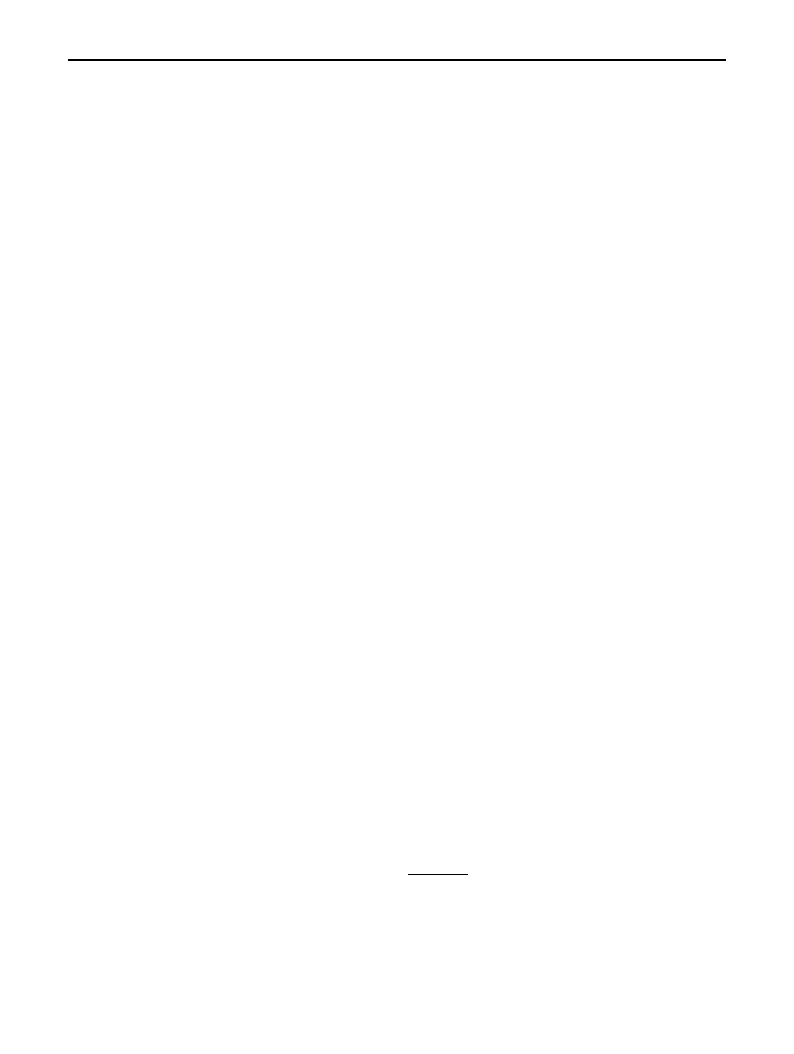

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for all vari-

ables used in the study. The average number of species

disclosed by companies is about 3 species with a standard

deviation of 21. This implies that there is a significant

difference in the reported species among the companies.

We further nalysed by country and found developing coun-

tries have a higher mean score for the number of species

(i.e., 3.458) than developed countries (i.e., 2.614). This

supports the recent arguments, where experts believe that

developing countries are to blame for the COVID-19 pan-

demic due to illegal wildlife trade and wet markets and

call for enforcing the banning of such trades to prevent

further pandemics and extinctions and forcing companies

to become socially responsible (Ceballos et al., 2020; Ma

et al., 2020). Legitimacy theory explains that develop-

ing countries provide more species to maintain societal

legitimacy and reputation (Adler et al., 2018; Bhattacha-

ryya & Yang, 2019). We found developed countries have

a higher mean score for assurance, environmental award,

partnerships, Big4, leverage, governance, industry, and

CO2 emissions, which is similar to prior studies on CSR

(Bouten et al., 2011; Tagesson et al., 2009). Furthermore,

the developing countries had a higher mean score for

environmental score, firm size, GDP, and inflation which

13

580

DistribuƟon of Key InformaƟon

L. Roberts et al.

REPORTS

FIRMS

AWARD ASSURANCE

BIG4

POP

Series1

Series2

Fig. 1 This figures shows a distribution of key information of our

data from 599 annual reports of 200 firms. Series 1 represents the

reports where firms did not report any species and Series 2 docu-

ments the reports in which firms included the names of species (we

counted the number of species as explained in the data description).

REPORTS is the number of reports in our data. FIRMS is the num-

ber of firms (during 2012–2016) in each set of Series. AWARD is the

number of reports indicating the firms received environment award.

ASSURANCE is the number of reports which mention whether the

firms receive assurance. BIG 4 is a subset of ASSURANCE indicat-

ing whether the assurance received from BIG 4. POP represents the

number of reports which mentions the presence of biodiversity/wild-

life partnerships

Table 2 Summary statistics of the variables used in our models

Full sample

Obs Mean

Median St.Dev

Number of species

599

Buying assurance

599

Environment score

599

Green

599

Environment award

599

Presence of partnership 599

Big 4

599

Firm size

590

Log (revenue)

593

Leverage

596

Governance

599

CO2 emission

400

Log (forest area)

596

GDP growth

596

Inflation

596

2.863

0.679

0.065

0.658

0.199

0.237

0.391

12.494

11.346

6840.108

0.839

10.426

13.322

2.820

1.552

0.000

1.000

0.000

1.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

11.809

11.234

0.383

1.232

9.200

14.527

2.200

1.400

21.552

0.467

0.250

0.475

0.399

0.425

0.488

2.512

0.545

167,000

0.785

4.645

2.014

2.528

1.504

Developing country Developed country

Obs Mean

Obs Mean

177

3.458 422

2.614

177

0.599 422

0.714

177

0.170 422

0.021

177

0.588 422

0.687

177

0.186 422

0.204

177

0.147 422

0.275

177

0.367 422

0.401

171 13.276 419

12.175

174 11.276 419

11.375

174 16.66

422 9653.568

177 − 0.246 422

1.294

116

7.545 284

11.602

174 14.100 422

13.002

174

5.681 422

1.641

174

2.344 422

1.226

Difference in means

t-test

0.844

− 0.115**

0.148***

− 0.100**

− 0.018

− 0.128***

− 0.033

1.101***

− 0.099**

− 9636.907

− 1.540***

− 4.058***

1.098***

4.040***

1.118***

supports the literature that finds a positive relation with

CSR disclosure (Chiu & Wang, 2014; Huang & Kung,

2010).

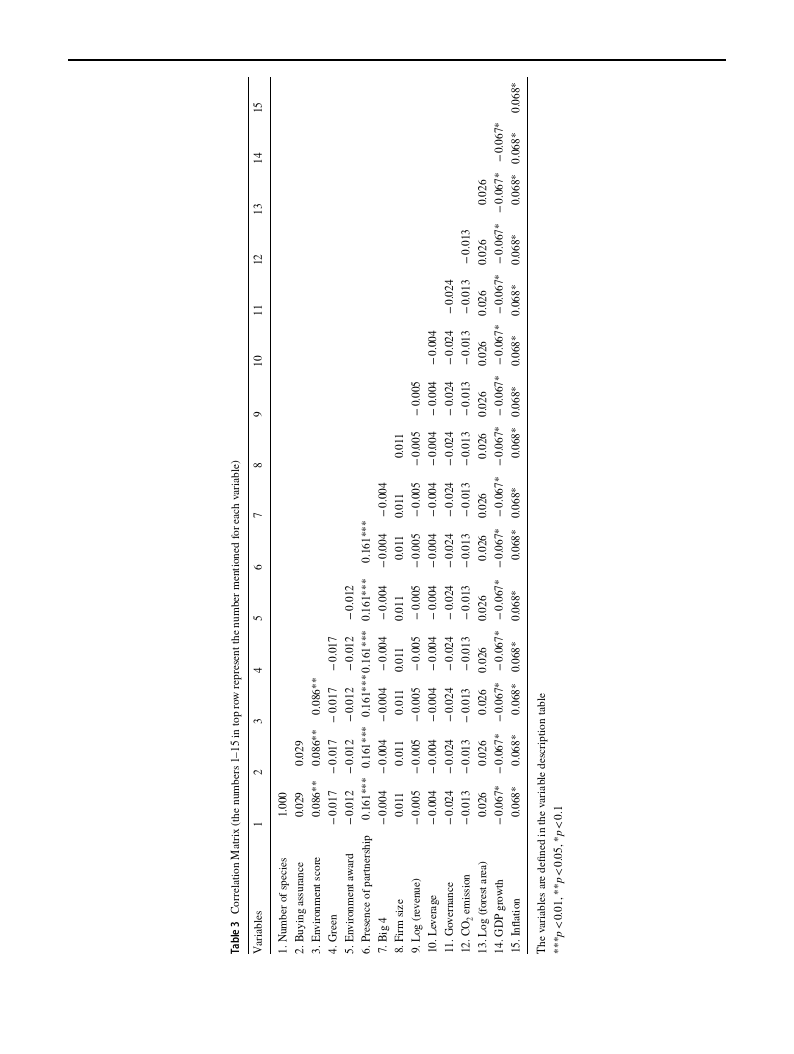

Table 3 provides the correlation matrix of all variables

included in the study. To identify any multicollinearity prob-

lems, we followed prior studies (Bhattacharyya & Yang,

2019; Haniffa & Cooke, 2005) and found a maximum of

0.161 as a correlation coefficient.

We tested the presence of multicollinearity by calculating

the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance values for

each of the explanatory and control variables, as presented in

Appendix A. The VIF indicates how much the variance of a

13

Corporate Accountability Towards Species Extinction Protection: Insights from Ecologically…

13

581

582

L. Roberts et al.

coefficient is inflated because of the linear dependence with

other variables, and the tolerance is the extent of variability

of selected regressors not explained by the other regressors.

The threshold values for VIF and tolerance are less than 10

and more than 0.1, respectively (see Gujarati, 2003; Hair

et al., 2013). Appendix A shows that the VIFs are below 5

(except the Governance variable, which is 5.88). So, multi-

collinearity is not a problem for our estimations of models.

Empirical Models

To test our hypotheses, we started with OLS regression by

using the natural logarithm of the number of species as our

dependent variable. However, the coefficients of the regres-

sion led to inconsistent estimators of the parameters of our

model. Following Gourieroux et al. (1984), therefore, we

used the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML)

regression with multi-way fixed effects model, since our

dependent variable—the number of species—is a non-neg-

ative count variable. In other words, the number of species,

a Poisson random variable, has a discrete probability distri-

bution that indicates the probability of a given number of

species reported in a fixed interval of time. In related simu-

lation results by Santos Silva and Tenreyro (2011), it shows

that the PPML model provides better results even when the

dependent variable contains a large number of zeros. So, we

believe that the Poisson distribution model is appropriate for

our data. This is because 75% of our sample did not provide

disclosure on species protection. In general, we write our

empirical model as

unlikely to follow a negative binomial distribution. So, in

accordance with Cameron and Trivedi (1990), we tested for

over-dispersion. We failed to reject the null hypothesis of

mean–variance equality in all the estimations. This justifies

the use of Poisson for our sample.

Empirical Results

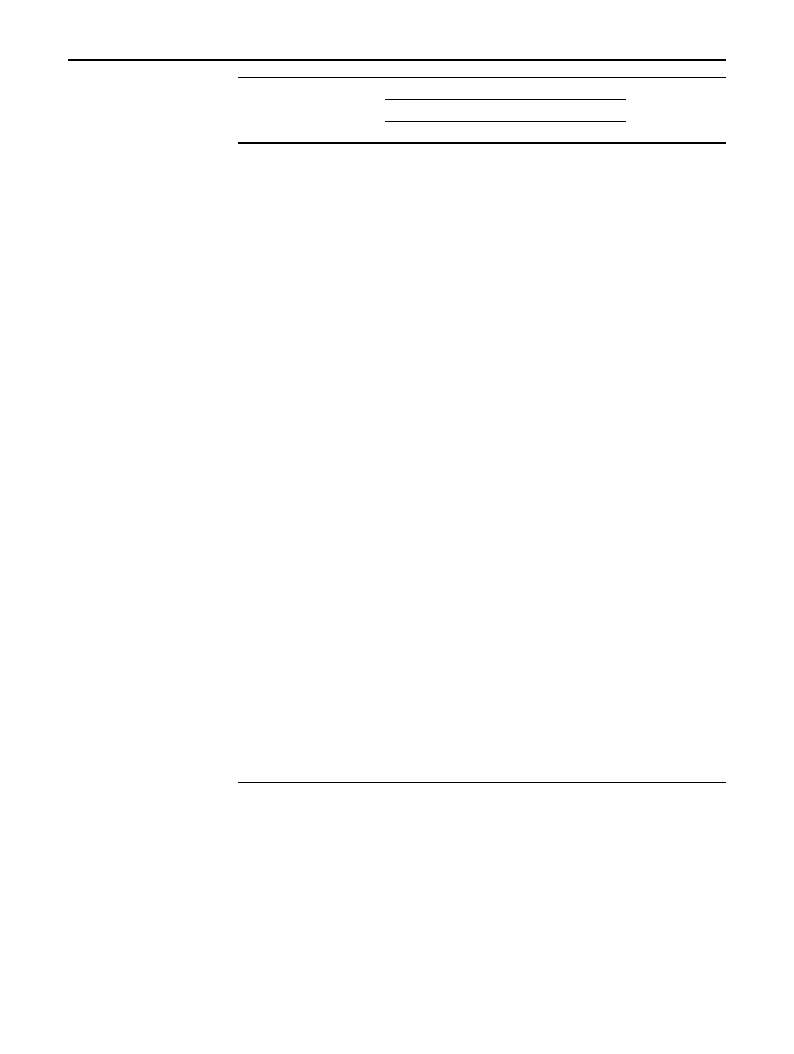

In Table 4, we report the results of the Poisson regression,

to explain the results for the likelihood of the number of

species disclosed by the companies. In addition to the coef-

ficients, we also show White’s heteroscedasticity robust

standard errors in parenthesis.13 In Model 1 of Table 4, the

model is estimated by traditional Poisson regression with

year and country fixed effects. In Model 2, we report the

Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML) regression

with multi-way fixed effects.

Based on the deep ecology concept, in this paper, we

consider species as a stakeholder (Samkin et al., 2014), and

therefore, in Hypothesis 1, we propose that there is a posi-

tive relationship between the number of species and buy-

ing assurance. The proposition in Hypothesis 1 is proven

in Models 1 and 2, which show positive and statistically

significant coefficients (Model 1: β = 1.129, p < 0.05; Model

2: β = 1.131, p < 0.10, respectively) of buying assurance.

It implies that firms with assurance are likely to report a

greater number of species than those firms without assur-

ance. Hypothesis 1 reinforces empirical studies which have

found that assured information is viewed as more cred-

ible and reliable, narrowing the legitimacy gap (Cho et al.,

Yit = f (Buying Assurance, Environment Score, Environment Award, Green, Presence of Partnership,

(1)

Big 4, Firm- and Country-level control variables)

where, Y is the number of all species disclosed on financial

reports of sample firm i in year t.

In particular, for our Poisson model, the conditional mean

of Y in Eq. (1) is written as E(Y|X) = exp(X )

where X is the vector independent variable (shown in

Eq. 1) and a constant. The maximum likelihood estima-

tor of , the coefficients of relevant independent variables,

is calculated by maximizing the following log-likelihood

function:

∑

L( ) = Ytlog t − t − log(Yt)

(2)

where t = exp(xt� ) shows a model for the conditional

mean of the number of species. However, there may exist

a problem with the model as it imposes an assumption of

mean–variance equality in its empirical application. Thus, an

alternative model could be a negative binomial model. But

our outcome variable, i.e., the number of species, seemed

2015a; Maroun, 2018). Theoretically, our results support

deep ecology, legitimacy, and stakeholder theories as the

overall increase in disclosure optimistically displays a deep-

ecological view with companies being aware of the funda-

mental value of the planet. Our results support Hassan et al.

(2020b), which found a positive relationship between assur-

ance and biodiversity disclosures. Theoretically, our results

align with deep ecology, evidencing that companies are

committed to protecting species (Samkin et al., 2014), and

valuing them as stakeholders. Additionally, these findings

have implications for policymakers in developing solutions

with companies providing assurance on species information.

13 To adjust for the differences between variance and mean score,

we use a bootstrapping method in the Poisson regression using 500

replications (not reported). The resampling procedure with replace-

ment creates simulated datasets for the estimation. Our results remain

qualitatively similar.

13

Corporate Accountability Towards Species Extinction Protection: Insights from Ecologically…

583

Table 4 Poisson regression results for the likelihood of number of

species disclosed

Dependent variable: number of species

Poisson regression with

year and country FE

PPML with

multi-way

FE

(1)

(2)

Buying assurance

Presence of partnership

Environment Score

Environment award

Big 4

Green industry

Firm size

Log (revenue)

Leverage

Governance

CO2 emission

Log (forest area)

GDP growth

Inflation

Constant

Observations

Pseudo R2

Country fixed effects

Year fixed effects

1.129**

(0.498)

4.093***

(0.446)

1.533*

(0.800)

− 1.948***

(0.455)

− 1.675***

(0.552)

0.226

(0.454)

0.059

(0.069)

− 0.283

(0.366)

− 0.000***

(0.000)

3.991*

(2.193)

− 1.033*

(0.625)

0.727*

(0.384)

− 0.559*

(0.315)

0.546*

(0.285)

− 15.481

(9.832)

394

0.776

Yes

Yes

1.131*

(0.601)

4.111***

(0.477)

1.530**

(0.701)

− 1.937***

(0.454)

− 1.663***

(0.543)

0.233

(1.093)

0.062

(0.085)

− 0.313

(0.418)

0.020

(0.025)

3.912**

(1.865)

− 1.055

(0.822)

0.726**

(0.283)

− 0.561**

(0.274)

0.546*

(0.308)

1.021

(13.564)

373

0.773

Yes

Yes

The table reports the effects of assurance, environment award, pres-

ence of partnership and red Industry on the number of reported spe-

cies in firm’s annual report in each year. The data consists 599 firm-

year observations of top 200 firms listed in Global 500 firms for the

year 2012, 2014 and 2016. Green industry is a dummy equal to 1 if

the industry belongs to green industry and 1 if it is in red or amber

industry. Natural logarithm of total assets as a proxy for firm size is

used. Model 2 reports Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPL)

regression with multi-way fixed effects. Robust standard errors are

clustered at the industry level and reported in parenthesis

***Denotes 1%, **denotes 5% and *denotes 10% significance level

We expect that assurance will become an integral part of

companies committing to SDGs 14 and 15. This result is

in line with prior studies’ stream of literature that empiri-

cally examines the assurance of a company’s CSR report.

These studies note that stakeholders place more confidence

in CSR reports where the level of assurance provided is rea-

sonably high (Casey & Grenier, 2015; Kolk & Perego, 2010;

Mahoney et al., 2013; Peters & Romi, 2015; Pflugrath et al.,

2011; Simnett et al., 2009).

In addition, we consider the assurance provider as Big4.

Big4 is a binary variable equal to 1 if the sample company

has an auditor from one of the Big4 audit firms. The coef-

ficients in Models 1 and 2 show a negative and statistically

significant coefficient (Model 1: β = 1.675, p < 0.001; Model

2: β = 1.663, p < 0.001, respectively). This implies the num-

ber of species in reporting increases if the company is not

audited by one of the big four accounting firms. This addi-

tional result confirms that auditors from the Big4 account-

ing firms may be failing to address the B/E crisis or can-

not generate awareness in the company. A deep-ecological

concern would expect Big4 providers to relate to the need

for uniformed reporting guidelines on species and habitat

protection (Atkins & Atkins, 2018). Auditors from the Big4

must regard species as a main stakeholder post-pandemic.

To achieve SDGs 14 and 15, assurance providers like Big4

must encourage companies to develop long-term sustain-

ability and their consultancy must include advocating the

protection of species environmental recovery.

The coefficients of environment score in Models 1 and 2

are positive and statistically significant (Model 1: β = 1.533,

p < 0.10; Model 2: β = 1.530, p < 0.05, respectively). This

supports our Hypothesis 2, which states that poor environ-

mental performers are likely to report a greater number of

species compared to better environment performers. This

result is consistent with prior literature that these compa-

nies disclose more to defend legitimacy (Cho et al., 2012;

Clarkson et al., 2008). Our results support empirical studies

that have found a positive relationship between poor envi-

ronmental performers and biodiversity disclosure (Hassan

et al., 2020b). Theoretically, our results support legitimacy

theory, which explains that these poor performers may dis-

close more species as they negatively impact biodiversity

through illegal wildlife trade and lack robust regulations, and

therefore, our results may benefit regulators with assisting

in preventing further species loss. Deep ecology explains

that to achieve SDGs 14 and 15, these poor performers must

begin to consider species as a stakeholder to prevent further

extinctions. This implies that poor environmental perform-

ers are more likely to seek environmental legitimacy and

more stakeholders’ satisfaction by reporting useful B/E

information.

In Hypothesis 3, we predict that to get an award to nar-

row the legitimacy gap and prove a deep concern for nature,

13

584

L. Roberts et al.

firms report a higher number of species. But, in Table 4,

our empirical result shows an opposite sign in coefficients

(Model 1: β = − 1.948, p < 0.001; Model 2: β = − 1.937,

p < 0.001, respectively). These results are surprising as

empirical B/E studies have found a positive relationship

with companies gaining an award (Hassan et al., 2020b).

Our results do not support prior literature (Adler et al., 2018;

Atkins et al., 2014) that companies should showcase con-

servation efforts in protecting species and calls for further

academic examination. Theoretically, this evidence suggests

companies are disregarding species as stakeholders and

neglecting deep ecology. Such a lack of sensitivity towards

B/E will make it difficult in achieving the policymakers’

target of B/E prevention. Our justification for such results is

due to lack of awareness and so far, there is no mandatory

requirement to disclose on the number of species. This high-

lights that there is a huge call for awareness for species to

be regarded as stakeholders by companies. Furthermore, our

results suggest a shift in corporate governance consciousness

to embed deep-ecological concern by protecting species and

their habitats and to prevent future pandemics like COVID-

19. By viewing species as stakeholders post-pandemic, they

are responsibly committing to achieving SDGs 14 and 15.

Thus, if companies become ecologically conscious of the

biodiversity crisis, environmental awards will demonstrate

their commitment to sustainable development.

Further, we test the association between the presence

of wildlife conservation partnership and number of spe-

cies. Models 1 and 2 show positive and statistically signifi-

cant coefficients (Model 1: β = 4.093, p < 0.001; Model 2:

β = 4.111, p < 0.001, respectively). This implies that firms

which have a wildlife conservation partnership are likely

to disclose a greater number of species. This gives evi-

dence in favor of Hypothesis 4. Our results support prior

studies (Adler et al., 2018; Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria,

2017; Hassan et al., 2020b) and highlight that wildlife

partnerships are a key driver of companies protecting spe-

cies. This also implies additional empirical support for our

multi-theoretical perspective that integrates insights from

legitimacy, stakeholder, and deep ecology theories. Specifi-

cally, deep ecology explains how companies engaging in

partnerships are preserving nature (Atkins et al., 2018), and

confirms that companies view species as stakeholders by

protecting their habitats and realizing their intrinsic worth.

Our finding implies that companies respond to increased

stakeholder expectation by proactively engaging in compre-

hensive wildlife conservation partnerships, which leads to

better B/E-related activism and B/E reporting. Companies

may indeed be showcasing conservation efforts to protect

species and habitats to gain legitimacy (Adler et al., 2018).

However, partnership engagement increases knowledge and

can address the extinction crisis and prevent future pan-

demics. To meet SDGs 14 and 15, collaboration and shared

knowledge are encouraged (Jones & Solomon, 2013). Our

results imply that partnership association can help develop

solutions (Bebbington & Unerman, 2018; Gibassier et al.,

2020) and achieve a sustainable future. This evidence is also

in line with our multi-theoretical framework that implies

that companies use these mechanisms as public relationships

instruments to legitimize their existence (e.g., Adler et al.,

2018; Hassan et al., 2020b) and oversee the perceptions of

the pertinent stakeholders (Bhattacharyya & Yang, 2019).

Finally, regarding control variables, we find Governance,

Forest area, and Inflation are statistically significant and

positively related to the number of species, suggesting that

country-level variables are key determinants of disclosure on

the number of species. Overall, our hypotheses are mostly

supported by our empirical findings.

Robustness Tests

In the previous section, we use Poisson regression to inves-

tigate the relationship between company-level variables

(such as assurance, presence of partnerships, firm size) to

the number of species. In this section, we analyze our data

in three phases: (1) dividing the data into two sub-samples,

based on the firms headquarter, in developed and develop-

ing countries; (2) analyzing the full sample by taking care

of over-dispersion of the data by reclassifying the sample

into four groups based on the number of species disclosed,

and (3) dividing the sample into financial and non-financial

companies.

In our first test, we report the results of the variables that

influence companies to commit to a greater number of spe-

cies disclosure and how those variables work among firms

operating in developed and developing countries. The results

of Poisson regression at the firm-level data for developed

and developing countries are reported in Table 5.

Our findings in Table 5 mostly support our hypotheses.

Table 5 reveals that Environment Score and Environment

Award have a significant impact on disclosure of the number

of species protected in companies that operate in developing

environments compared with their counterparts that oper-

ate in developed countries. These findings are supported

by the legitimacy theory expectation that companies from

13

Corporate Accountability Towards Species Extinction Protection: Insights from Ecologically…

585

Table 5 Robustness tests:

Poisson regression

Dependent variables

Developed country

Poisson regression

Number of species

(1)

Developing country

(2)

Full sample (ZIP)

Zero-inflated

Poisson regres-

sion

nSpecies

(3)

Buying assurance

Presence of partnership

Environment score

Environment award

Big 4

Green industry

Firm size

Log (revenue)

Leverage

Governance

CO2 emission

Log (forest area)

GDP growth

Inflation

Constant

Observations

Pseudo R2

Country fixed effects

Year fixed effects

0.427

(0.541)

4.029***

(0.466)

− 0.486

(2.572)

− 2.110***

(0.685)

− 1.867***

(0.549)

n.a.

0.156**

(0.075)

− 0.871*

(0.489)

− 0.000***

(0.000)

− 6.800

(6.130)

− 0.588

(0.671)

0.399

(0.463)

− 0.193

(0.541)

1.268**

(0.565)

9.234

(11.970)

282

0.807

Yes

Yes

2.314***

(0.560)

2.765***

(0.431)

2914.660***

(630.495)

1.854***

(0.469)

− 1.951**

(0.821)

n.a.

− 0.743***

(0.169)

1.481***

(0.246)

− 0.057***

(0.015)

9.205***

(2.300)

2.534*

(1.317)

− 266.271***

(58.215)

− 1.078***

(0.334)

− 1.196***

(0.310)

3191.847***

(696.727)

112

0.924

Yes

Yes

0.100*

(0.059)

0.070**

(0.030)

− 0.109**

(0.046)

0.139**

(0.062)

− 0.066

(0.102)

0.054

(0.039)

− 0.004

(0.013)

− 0.029

(0.049)

− 0.001

(0.001)

0.001

(0.246)

n.a.

0.027

(0.030)

− 0.037**

(0.018)

− 0.019

(0.043)

0.005

(0.420)

587

n.a.

Yes

Yes

The table reports the effects of assurance, environment award, presence of partnership and green Industry

on the number of reported species in firm’s annual report in each year. The data consists 599 firm-year

observations of top 200 firms listed in Global 500 firms for the year 2012, 2014 and 2016. nSpecies-coded

from 0 to 4–0 if the number of species is 0, and 1–4 if the number of species is in the range of 1–99, 100–

199, 200–299, 300 and more respectively. Green industry is a dummy equal to 1 if the industry belongs to

green industry and 1 if it is in red or amber industry. Natural logarithm of total assets as a proxy for firm

size is used. Column 3 reports Zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression. Robust standard errors are reported

in parenthesis

***Denotes 1%, **denotes 5% and *denotes 10% significance level

13

586

L. Roberts et al.

developing countries want to portray a positive corporate

image and influence stakeholder perception (Hassan et al.,

2020b; Tagesson et al., 2009). Similarly, we find that assur-

ance has a significant positive effect on disclosure of the

number of species protected in companies that operate in

developing environments, compared to their counterparts

operating in developed countries. Overall, the results support

our claim that institutional context has a moderating effect