Original Article

A Review of Field Experiments on the

Effect of Forest Bathing on Anxiety

and Heart Rate Variability

Marc R Farrow, PT1 and Kyle Washburn, RN, BSN, CEN2

Global Advances in Health and Medicine

Volume 8: 1–7

! The Author(s) 2019

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals-permissions

DOI: 10.1177/2164956119848654

journals.sagepub.com/home/gam

Abstract

Many studies have explored the physiological and psychological benefits of the Japanese nature therapy practice of “shinrin-

yoku,” known in the West as forest bathing. This review article has narrowed its focus to include the most recent literature

about the beneficial effects of forest bathing on heart rate variability, expressed as an increase in InHF, indicating activation of

the parasympathetic nervous system and also its effect on reducing anxiety.

Keywords

forest bathing, shinrin-yoku, anxiety, heart rate variability

Received January 3, 2019; Revised received April 3, 2019. Accepted for publication April 8, 2019

Introduction

Urbanization continues to increase worldwide, and

by 2050, 68% of the population is projected to live in

an urban environment.1 This trend has a negative

impact on physical and emotional health. “Overall,

urbanicity seems to be linked to a higher risk of

mental health disorders.”2

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric

disorders. According to epidemiological surveys, one-

third of the population is affected by an anxiety disorder

during their lifetime. They are more common in women.

During midlife, their prevalence is highest. These disor-

ders are associated with a considerable degree of impair-

ment, high health-care utilization and an enormous

economic burden for society.3

This review aims to consider if the practice of forest

bathing may be a valuable intervention to treat anxiety

and boost parasympathetic responses.

scientific rationale for forest walks. Most of the guided

walks I’ve been on in Japan begin and end with measure-

ments of blood pressure and salivary amylase, which are

indicators of stress and relaxation.” For the purposes of

this article, the forest bathing model entails an average

of 2 to 4 hours in a forest and includes a combination of

various activities such as walking, standing, lying, sit-

ting, and deep breathing. This practice is facilitated by

a trained forest bathing guide to focus participants’

attention with meditative concentration on sensory expe-

riences, engaging sight, sound, touch, smell, and some-

times taste to explore the surrounding forest.6 Forest

bathing can be defined as immersion in nature with

mindful use of all 5 senses; studies on physical and

mental health benefits report reduced stress, anxiety,

and depression symptoms as well as improved mood

and relaxation.7

Background

Forest bathing is a nature therapy originally developed

in Japan as shinrin-yoku, a term coined in 1982 by

Tomohide Akiyama of the Japanese Forestry Agency.4

This therapeutic technique can be described as “bathing

in the forest atmosphere, or taking in the forest through

our senses.”5 Clifford notes “the Japanese emphasize the

1Winston-Salem Forest Bathing, Lexington, North Carolina

2Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem,

North Carolina

Corresponding Author:

Marc R Farrow, Winston-Salem Forest Bathing, Lexington, NC, USA.

Email: wsforestbathing@gmail.com

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and dis-

tribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.

sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

2

Global Advances in Health and Medicine

Methods

A broad review of the available literature was conducted

using the PubMed and ScienceDirect databases with the

keywords: “shinrin-yoku,” “forest therapy,” “forest

walking,” and “nature therapy”; 631,953 references

were found with this search. The results were narrowed

to recent field experiments with dates ranging from 2008

to 2018 that also used a formalized forest bathing

program affecting anxiety levels and heart rate variabil-

ity; however, other studies using similar methods of

exposure to natural settings were also included due to

the limited amount of recent research specifically related

to a formalized forest bathing program. Inclusion crite-

ria for these additional field experiments are defined as

walking in a forest for a determined amount of time.

Some studies were excluded in which surveys were

given or lab experiments were conducted where

participants were presented with images or other natural

stimuli versus actually walking in natural surroundings.

Nine articles were selected for this review.

Effects on Parasympathetic Nervous

System Activity

Research observing the effects of forest bathing/forest

therapy on the autonomic nervous system (measuring

an increased heart rate variability as an indicator) were

found with 2 studies.

The first study analyzed the heart rate variability

(HRV) of 485 young male participants while walking

in forest versus urban environments. HRV data were

obtained while groups walked “in a forest or an urban

environment for approximately 15 minutes. On the

second day, the participants switched field sites.”8

During forest walking, larger parasympathetic indica-

tor of HRV (InHF) and smaller sympathetic indicator of

HRV (In(LF/HF)) were observed compared with those

walking in urban environments. As the InHF and In

(LF/HF) are indicators of parasympathetic and sympa-

thetic activity, the results implied that the autonomic

relaxation occurred during walking in forest environ-

ments. Parasympathetic activation (using HRV as an

autonomic nervous system indicator) while walking in

forest environments has been established in previous

field experiments by the same authors and are confirmed

by this study. It is important to note that increased InHF

indicates an increase in parasympathetic activation

response: lowered heart rate and blood pressure, and a

calm mood state. Conversely, increased In(HF/LF) indi-

cates a heightened state, or “fight or flight” response.

In addition, previous studies suggest that InHF differs

between viewing and walking, with an increase in InHF

evident with walking.8

In the second study, “autonomic responses to urban

and forest environments were studied in 625 young male

subjects.”9 The participants were randomly divided into

2 groups that viewed either a forest or urban landscape

for 15 minutes each in a seated position. HRV was mon-

itored continuously. “The experiment was performed at

each experimental site over 2 consecutive days.”9 On day

2, the subjects switched environments, repeating the

protocol from the first day.

“Approximately 80% of the subjects showed an

increase in the parasympathetic activity”9 in a forest set-

ting and the urban subjects exhibited the opposite effect.

The measured variations in InHF between forest and

urban locations measured reveal that 79.2% of the 625

subjects experienced an increase in InHF when exposed

to a forest setting; conversely, 20.8% of the 625 subjects

experienced a decrease in InHF. In addition, difference

in the InHF mean values is statistically significant,

although minute. Similar results were found for ln

(LF/HF) values, indicating HRV may be a more sensi-

tive tool for measuring parasympathetic activation in

this experiment.9

In this third study evaluating the cardiovascular

effects of nature on women, 36 female subjects, aged

30 to 50 years, were selected. In randomly changing

groups of fours, the subjects were exposed to an urban

area, an urban park, or an urban forest. Seated exposure

time was 15 minutes and walking exposure time was

30 minutes. Measurements gathered include blood pres-

sure, heart rate, and electrocardiogram to determine

HRV. Breathable particulate matter and noise levels

were also recorded in each setting. Substantially reduced

levels of particulate air pollution and noise levels were

recorded in natural areas, while higher levels of noise

and breathable particulate matter were found with city

exposures. The data analysis revealed that exposure to

natural settings shows increased high frequency (HF)

power and a lower heart rate, indicating an increase in

parasympathetic nervous activity. Viewing natural set-

tings compared to viewing city areas yields similar

results as well as reduced systolic blood pressure.

In general, the results of this study indicate that even

brief exposure to a natural setting may result in reduced

cardiovascular risk. Furthermore, high noise levels and

increased levels of air pollution outdoors appear to have

a negative effect on cardiovascular benefit. The authors

noted that the combined measures of HRV and heart

rate are a more sensitive measure of stress response in

short-term field experiments in comparison to similar

studies using cortisol levels as a stress indicator.

Limitations noted in this field experiment include a

small sample size and the absence of male subjects in

this study.10

Farrow and Washburn

3

Effects on HRV and Anxiety Levels

Several other articles consider the effects of forest bath-

ing/forest therapy on anxiety-tension using The Profile

of Mood States (POMS) subscale scores and the seman-

tic differential (SD) method.

One such study measured changes in autonomic ner-

vous system activity and emotions after a 2-hour forest

bathing program in 128 middle-aged and elderly partic-

ipants. Physiological measurements were taken; pulse

rate, blood pressure, HRV, and POMS subscale scores

were recorded.

The POMS “subscale scores for ‘tension-anxiety’,

‘anger-hostility’, ‘fatigue-inertia’, ‘depression-dejection’,

and ‘confusion-bewilderment’ were significantly lower,

whereas the positive mood subscale score of ‘vigor-activ-

ity’ was higher.”11 In addition, participants reported sig-

nificantly lower levels of anxiety using the Spielberger

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. This study determined

that a forest bathing program causes significantly

lower pulse rate, systolic, and diastolic blood pressure

after a 2-hour walk. In addition, reduced tension, anger,

fatigue, depression, confusion, anxiety and improved

positive emotions were reported. Surprisingly, sympa-

thetic and parasympathetic nerve activity measures

revealed no significant changes. In summary, a 2-hour

forest bathing program appears to yield physiological

and psychological benefits with middle-aged and elderly

individuals.

In another study, 20 Japanese men were screened and

10 were selected for 2 groups of 5. Each participant had

been diagnosed with stage 1 hypertension (having a sys-

tolic 140–159 mm Hg or diastolic 90–99 mm Hg) and 5

had stage 2 hypertension (having a systolic 160–179 mm

Hg or diastolic 100–109 mm Hg). Each group alternated

walking in a forest setting for 17 minutes one day fol-

lowed by walking for 17 minutes in an urban setting the

next day. Heart rate and HRV were used to quantify

autonomic nervous system responses. Subjects complet-

ed 2 questionnaires measuring mood states using the

modified SD method referencing 3 pairs of adjectives

on 13 scales: “comfortable to uncomfortable,” “relaxed

to awakening,” and “natural to artificial.” A modified

30-question POMS was set for 6 subscales: “tension-

anxiety,” “depression,” “anger-hostility,” “fatigue,”

“confusion,” and “vigor.”

Results indicated that walking in a forest elicited both

physiological and psychological relaxation for middle-

aged individuals with hypertension; there was a signifi-

cant increase in parasympathetic nerve activity and a

significant decrease in heart rate. In addition, a signifi-

cant increase in “comfortable,” “relaxed,” and “natural”

mood, and reduced “tension-anxiety,” “depression,”

“anger-hostility,” “fatigue,” “confusion,” and “vigor”

were reported. The authors point out this study’s

limitations, including an inability to generalize these

results for the female population and for people of vary-

ing ages, and thus a more comprehensive study is rec-

ommended in the future.12

A third article investigated the influence of forest

therapy on cardiovascular effects. “Forty-eight young

adult males participated in the two-day field research”13

comparing physiological and psychological changes

during forest walking and urban walking. Changes in

HRV, heart rate, and blood pressure were measured

and questionnaires recorded changes in mood states

following walking. Subjective measures such as

“comfortable-uncomfortable,” “natural-artificial,” and

“soothed-aroused” were recorded using a 13-scale SD

method. The modified 30-question version of the

POMS questionnaire was used to measure mood.

Anxiety was measured using the Spielberger State-Trait

Anxiety Inventory questionnaire. Each group walked for

14 minutes in each environment.

The study found forest walking significantly increased

In(HF) values and significantly decreased In(LF/HF)

values compared to urban walking. Heart rate during

forest walking was significantly lower than the urban

walking control group. Reported subjective measures

indicated that “negative mood states and anxiety levels

decreased significantly by forest walking compared with

urban walking.”12 “Walking in a forest environment

may promote cardiovascular relaxation by facilitating

the parasympathetic nervous system. In addition,

forest therapy may be effective in reducing negative psy-

chological symptoms.”13

Another study examined the effects of walking in a

forest on HRV and mood states, comparing natural set-

tings to city environments. Over the course of 2 years, 24

field experiments were done with 280 Japanese male par-

ticipants to compare the findings regarding the physio-

logical effects of forest walking with corresponding

results from previous research. Each experiment was

comprised of 12 subjects divided into 2 groups of 6.

One group was assigned to walk in a city while the alter-

nate group walked in a forest environment. Each group

walked approximately 14 minutes. On the following day,

the groups alternated settings. Blood pressure, heart

rate, HRV, and salivary cortisol levels were recorded

prior to and following each walk. All cardiac data

were collected with a portable electrocardiograph, and

both HF and low frequency (LF) power level compo-

nents were calculated each minute during walking.

Psychological status was measured using the POMS

recording 6 dimensions of mood: tension-anxiety,

depression-dejection, anger-hostility, fatigue, confusion,

and vigor.

Results indicated reduced salivary cortisol levels after

walking or viewing natural environments, with a 2.4%

decrease when walking is compared to viewing.

4

Global Advances in Health and Medicine

Significantly lower average pulse rates were recorded in a

natural setting versus a city environment, and walking

resulted in lower rates than viewing. Comparable results

were also seen in the reduced average diastolic blood

pressure after walking in versus simply viewing nature.

In addition, a 102% increase in InHF after walking and

a 56% increase after viewing with a corresponding

reduction in In(LF/HF) were measured. POMS score

results indicate that natural settings (versus urban envi-

ronments) reduce tension/anxiety, depression, anger,

confusion, as well as increase vigor, and that walking

in nature yields significantly greater effects as compared

with viewing natural settings.

In summary, exposure to forest bathing, when com-

pared to exposure to urban settings, may reduce heart

rate, cortisol levels, blood pressure, and increase parasym-

pathetic nervous system activity indicating a lower stress

response. These findings, along with past studies, establish

a strong case that exposure to nature has a positive

impact on human physiology and mental health.14

Effects on Anxiety

Additional studies considered the influence of forest

bathing/forest therapy on anxiety levels in participants.

One study recorded the effects of forest bathing on

cardiovascular function and mood states in 19 middle-

aged hypertensive subjects while walking in a forest

versus during urban walking. Forest park walking for

80 minutes “significantly reduced the pulse rate in

middle-aged males with higher blood pressure, com-

pared with walking in an urban area.”15 Pulse rate is

an index of autonomic nervous system activity indicating

a state of relaxation.

Results included decreased pulse rate, a decrease in

urinary dopamine, tendency toward decreased urinary

adrenaline, a decrease in adiponectin in serum, in addi-

tion to a significantly increased score for vigor, and

decreased scores for depression, anxiety, fatigue, and

confusion (using POMS). In contrast, urban walking sig-

nificantly increased scores for fatigue and reduced scores

for vigor. As found in previously discussed studies, the

cumulative effect suggests a forest bathing program

induces a significant physiological and psychological

state of relaxation.15

Two studies authored by Ochai et al. explored the

physiological effects of a forest therapy program on

middle-aged females and males, respectively. In the

first study, 17 middle-aged Japanese females were select-

ed to determine the effects of a formalized forest therapy

regimen on both physiological and psychological status.

Subjects took a 4-hour 41-minute walk; systolic, diastol-

ic BP, and pulse rates were recorded, and salivary sam-

ples were taken to obtain a reliable measure of cortisol

levels, as an increase in cortisol indicates stress.

Data were gathered the day before the walk and follow-

ing forest therapy. Urinary adrenaline, noradrenaline,

and salivary cortisol levels were measured to determine

sympathetic activity. The SD method and short form of

the POMS were used to measure psychological status.

The SD method used 3 pairs of adjectives on 7-point

scales: “comfortable to uncomfortable,” “relaxed to

awakening,” and “natural to artificial”. The short form

of POMS included 3 subscales: “tension–anxiety,”

“fatigue,” and “vigor.”

Pulse rate was shown to be notably lower following

forest therapy versus the prior day, while salivary corti-

sol levels were also significantly lower. Significantly

higher SD scores were reported for “comfortable,”

“relaxed,” and “natural” following forest therapy than

on the prior day. In addition, the POMS scores revealed

a significant improvement in mood; the negative sub-

scale “tension–anxiety” was significantly lower and the

positive range of the emotional subscale “vigor” was sig-

nificantly higher following forest therapy. The mean

pulse rate was significantly lower as well after forest

therapy when compared to the prior day, indicating a

state of relaxation. Lab results also revealed that salivary

cortisol levels were significantly lower following forest

therapy than the day before. The authors conclude

that forest therapy also reduces stress in middle-aged

females but recognize that this study had the limitation

of excluding an urban walk control group in order to

compare results with the forest therapy group.16

In the second study, 9 Japanese males ranging in age

from 40 to 72 years were selected as participants in a

study to assess the physiological and psychological

effects of forest therapy on middle-aged males with

high-normal blood pressure (systolic 130–139 mm Hg

and/or diastolic 85–89 mm Hg). Each participant

engaged in a 4-hour 35-minute forest therapy walk.

Blood pressure and several physiological and psycholog-

ical indicators of stress were measured at the same time

of day on the day prior to and following forest therapy.

Urine and blood samples were also taken, measuring

adrenaline, cortisol, and creatinine. Questionnaires

were completed by subjects the day before and following

forest therapy. The SD method, POMS subscale scores,

and combined POMS Total Mood Disturbance (TMD)

score were used to evaluate psychological responses

to forest therapy. The SD method used 7-point scales

for 3 pairs of adjectives, such as “comfortable to

uncomfortable,” “relaxed to awakening,” and “natural

to artificial”. The short-form POMS scores used 30 ques-

tions with the following 6 subscales: “tension-anxiety,”

“confusion,” “anger-hostility,” “depression,” “fatigue,”

and “vigor.” The TMD score was calculated by using the

POMS 6 subscales values, and a high TMD score corre-

lates with a negative psychological state.

Farrow and Washburn

5

This study demonstrated that forest therapy facili-

tates a significant decrease in blood pressure and a

decrease in serum cortisol levels and urinary adrenaline.

Also reported were an increase in “natural” and

“relaxed” feelings measured by the modified SD

method, “a decrease in POMS negative subscales ‘ten-

sion-anxiety’, ‘confusion’, and ‘anger-hostility’, as well

as the TMD score in middle-aged males with high-

normal blood pressure.”17 The authors recognize the

limitations of this study due to lack of a control group

walking in an urban setting.17 The results of the above

discussed studies are summarized in Table 1.

Analysis

It is evident that more research is required to further

explore the beneficial health effects of a formalized

forest bathing program as only 3 of the 10 articles

reviewed here chose an accepted forest bathing model

in their experimental design (Yu and Ochiai). One

study (Lanki) closely approximated a forest bathing

program, during which subjects were guided through

numerous activities engaging the 5 senses. The remaining

6 research articles relied only on walking in and/or view-

ing a forest environment. A consistent use of a formal-

ized forest bathing program would ensure more reliable

outcomes in further research in this area.

Of the reviewed studies, 40% of the researchers select-

ed young participants in their 20s, while the majority

chose subjects aged 30 to 69 years. This is a limitation;

it will be advantageous for future researchers to include

a broader range of ages, equally represented, in order to

generalize results across the population.

It is notable that only 1 study included both male and

female subjects in their experimental design. This may be

of importance as there is evidence there may be physio-

logical differences in how men and women respond to

stress.18 Studies reviewed included 70% male partici-

pants, 20% female participants, and 10% mixed group.

It is advisable to consider a more heterogeneous sample

in the experimental design with regard to gender. It is

also of interest to note that 60% of the reviewed studies

had sample sizes less than 100 participants.

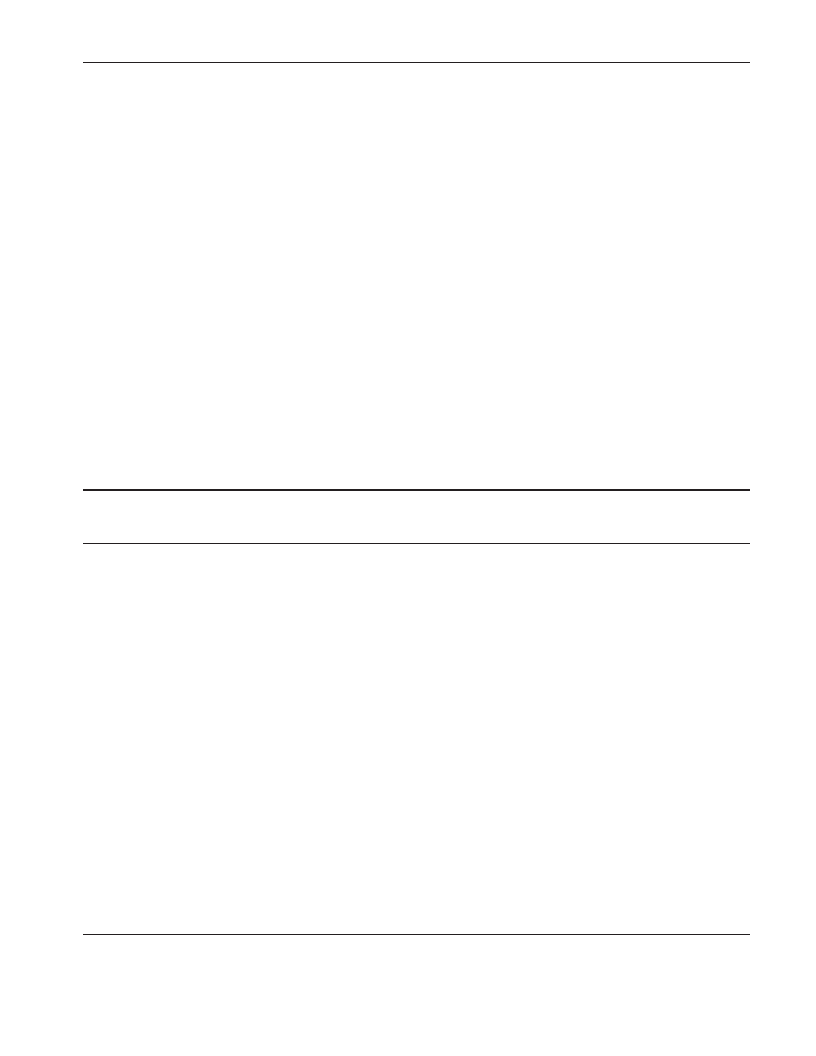

Table 1. A Summary of Research Studies.

Study Author

Kobayashi et al.8

Kobayashi et al.9

Lanki et al.10

Yu et al.11

Song et al.12

Lee et al.13

Park et al.14

Li et al.15

Location

Japan

Japan

Finland

Taiwan

Japan

Japan

Japan

Japan

Number

of Subjects

485

625

36

43/85

20

48

280

19

Gender of

Subjects

M

M

F

M/F

M

M

M

M

Age of Subjects

(Mean Æ Standard

Deviation)

21.7 Æ 1.6

21.6 Æ 1.6

30-60

(age range)

60.0 Æ 7.44

58.0 Æ 10.6

21.1 Æ 1.2

21.7 Æ 1.5

51.2 Æ 8.8

Exposure

Time in

Minutes

15

15

30

120

17

14

16 Æ 5

14 Æ 2

80

Stimuli vs

Control

F vs U

F vs U

F vs U

Before FB

vs after FB

F vs U

F vs U

F vs U

F vs U

Follows

FB Model

No

No

Closely

approximates

Yes

No

No

No

No

Results

" INHF

" INHF

" INHF

# Anxiety

# HR

# BP

# Anxiety

" INHF

# Anxiety

" INHF

# Anxiety

" INHF

# Anxiety

# HR

# SC

# Anxiety

# HR

Ochiai et al.16 Japan

17

F

62.2 Æ 9.4

281

FB vs control Yes

Ochiai et al.17 Japan

9

M

56.0 Æ 13.0

275

FB vs control Yes

# Anxiety

# HR

# SC

# Anxiety

# BP

# SC

# UA

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; F, forest; FB, forest bathing; HR, heart rate; INHF, average power of the high-frequency component of heart rate

variability; SC, salivary cortisol; U, urban; UA, urinary adrenaline.

6

Global Advances in Health and Medicine

Another result of this review highlights that the inci-

dence of increased InHF occurred in all 6 articles eval-

uating the effect of HRV while exposed to a natural

environment. These provide strong evidence that forest

bathing may elicit parasympathetic nervous activity.

Based on the studies reviewed here, it is evident that

forest bathing and exposure to nature approximating

this model, even for as little as 15 minutes, may be of

benefit in reducing anxiety and stress. However, there

were wide variances in exposure time across these stud-

ies, from 15 minutes to over 4 hours. Fifteen minutes

was the most frequent exposure time used (55% of stud-

ies reviewed). It would be of interest if future research

could determine if longer times result in stronger results,

or perhaps additional health benefits. It is also notable

that significant physiological benefits were also found by

simply viewing a forest setting; however, the effect has

been less than with walking.14

Limitations

This review raises questions regarding what would be con-

sidered a minimal as well as an optimal therapeutic dose

for time spent forest bathing in order to maximize physi-

ological and mood benefits. Further field experiments

would be justified to determine if longer exposure times

would yield even more health benefits yet to be deter-

mined. It should be considered whether benefits are depen-

dent on specific amounts of exposure time, as there

appears to be no standard used for research purposes cur-

rently. In addition, a standardized forest bathing program

would improve the reliability of future research studies.

For results to apply to broader populations, it would

also be of benefit to select a more heterogeneous mix of

participants, as several studies referenced here chose either

male or female subjects within a determined age range.

Moreover, larger sample sizes would also contribute to

more reliable results, improved precision, and a better

understanding of the potential benefits of forest bathing.

Conclusions

The field experiments referenced here provide limited but

strong and consistent evidence that exposure to forest

bathing/forest therapy results in an increase in InHF

associated with activation of the parasympathetic ner-

vous system and also reduced anxiety. Additional ther-

apeutic benefits include positive mood states and

improved mental coordination, with a reduction in

stress levels and lower blood pressure.

Future Studies

The results from the inclusion criteria in this review

yielded a very low sample of articles on the effects of

forest bathing/forest therapy on anxiety levels and HRV.

Ongoing exploration of the practice of forest bathing is

needed in order to better understand the mechanisms

activating the parasympathetic nervous system and

how this may be used as a safe, economic, and effective

method of treating anxiety as an adjunct therapy to med-

ication and cognitive-based therapy. Additional field

experiments are recommended to establish a standard

for exposure time, a standardized forest bathing pro-

gram, and appropriate subject selection criteria to be

used in future studies.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with

respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of

this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

1. 2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects|

Multimedia Library—United Nations Department of

Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/develop

ment/desa/publications/2018-revision-of-world-urbaniza

tion-prospects.html. Published 2018. Accessed December

22, 2018.

2. Kovess-Masfe´ ty V, Alonso J, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere

K. A European approach to rural—urban differences in

mental health: the ESEMeD 2000 comparative study.

Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(14):926–936.

3. Bandelow B. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st

century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(3):327–335.

4. Miyazaki Y. Shinrin Yoku: The Japanese Art Of Forest

Bathing. Portland, OR: Storey Publishing, LLC; 2018:9.

5. Li Q. Forest Bathing. New York, NY: Viking Press; 2018:12.

6. Clifford M. Your Guide To Forest Bathing. Newburyport,

MA: Conari Press; 2018:8–9, 63.

7. Hansen M, Jones R, Tocchini K. Shinrin-Yoku (forest

bathing) and nature therapy: a state-of-the-art review. Int

J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):851.

8. Kobayashi H, Song C, Ikei H, et al. Forest walking affects

autonomic nervous activity: a population-based study.

Front Public Health. 2018;6:278.

9. Kobayashi H, Song C, Ikei H, Kagawa T, Miyazaki Y.

Analysis of individual variations in autonomic responses

to urban and forest environments. Evid Based Complement

Alternat Med. 2015;2015:1–7.

10. Lanki T, Siponen, T, Ojala A, et al. Acute effects of visits to

urban green environments on cardiovascular physiology in

women: a field experiment. Environ Res. 2017;159:176–185.

11. Yu C, Lin C, Tsai M, Tsai Y, Chen C. Effects of short

forest bathing program on autonomic nervous system

activity and mood states in middle-aged and elderly indi-

viduals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):897.

Farrow and Washburn

7

12. Song C, Ikei H, Kobayashi M, et al. Effect of forest walk-

ing on autonomic nervous system activity in middle-aged

hypertensive individuals: a pilot study. Int J Environ Res

Public Health. 2015;12(3):2687–2699.

13. Lee J, Tsunetsugu Y, Takayama N, et al. Influence of forest

therapy on cardiovascular relaxation in young adults. Evid

Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:1–7.

14. Park BJ, Tsunetsugu Y, Kasetani T, Kagawa T, Miyazaki

Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the

forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field

experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ Health

Prev Med. 2009;15(1):18–26.

15. Li Q, Kobayashi M, Kumeda S, et al. Effects of forest

bathing on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters in

middle-aged males. Evid Based Complement Alternat

Med. 2016;2016:1–7.

16. Ochiai H, Ikei H, Song C, et al. Physiological and

psychological effects of a forest therapy program on

middle-aged females. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

2015;12(12):15222–15232.

17. Ochiai H, Ikei H, Song C, et al. Physiological and psycho-

logical effects of forest therapy on middle-aged males

with high-normal blood pressure. Int J Environ Res

Public Health. 2015;12(3):2532–2542.

18. Kajante E, Phillips D. The effects of sex and hormonal

status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial

stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(2):151–178.