International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Article

Forest Manners Exchange: Forest as a Place to Remedy Risky

Behaviour of Adolescents: Mixed Methods Approach

Karolina Machácˇková 1,* , Roman Dudík 1 , Jirˇí Zelený 2 , Dana Kolárˇová 3, Zbyneˇk Vinš 2 and Marcel Riedl 1

1 Department of Forestry and Wood Economics, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Faculty of Forestry

and Wood Sciences, Kamýcká 129, 6-Suchdol, 16500 Praha, Czech Republic; dudik@fld.czu.cz (R.D.);

riedl@fld.czu.cz (M.R.)

2 Department of Hotel Management, Institute of Hospitality Management in Prague, Svídnická 506,

18200 Prague, Czech Republic; zeleny@vsh.cz (J.Z.); vins@vsh.cz (Z.V.)

3 Department of Languages, Institute of Hospitality Management in Prague, 18200 Prague, Czech Republic;

kolarova@vsh.cz

* Correspondence: machackovak@fld.czu.cz

Citation: Machácˇková, K.; Dudík, R.;

Zelený, J.; Kolárˇová, D.; Vinš, Z.;

Riedl, M. Forest Manners Exchange:

Forest as a Place to Remedy Risky

Behaviour of Adolescents: Mixed

Methods Approach. Int. J. Environ.

Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725.

https://doi.org/10.3390/

ijerph18115725

Abstract: This paper evaluates the impact of the forest environment on aggressive manifestations in

adolescents. A remedial educative programme was performed with 68 teenagers from institutions

with substitute social care with diagnoses F 30.0 (affective disorders) and F 91.0 (family-related

behavioural disorders), aged 12–16 years. Adolescents observed patterns of prosocial behaviour

in forest animals (wolves, wild boars, deer, bees, ants, squirrels and birds), based on the fact that

processes and interactions in nature are analogous to proceedings and bonds in human society. The

methodology is based on qualitative and quantitative research. Projective tests (Rorschach Test, Hand

Test, Thematic Apperception Test) were used as a diagnostic tool for aggressive manifestations before

and after forest therapies based on Shinrin-yoku, wilderness therapy, observational learning and

forest pedagogy. Probands underwent 16 therapies lasting for two hours each. The experimental

intervention has a statistically significant effect on the decreased final values relating to psychopathol-

ogy, irritability, restlessness, emotional instability, egocentrism, relativity, and negativism. Forest

animals demonstrated to these adolescents ways of communication, cooperation, adaptability, and

care for others, i.e., characteristics without which no community can work.

Keywords: forest fauna community; communication; social behaviour; aggression; projective tests;

Shinrin-yoku; forest pedagogy

Academic Editor: Takahide Kagawa

Received: 9 April 2021

Accepted: 24 May 2021

Published: 26 May 2021

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Copyright: © 2021 by the authors.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

1. Introduction

Every living organism manifests itself in relationship with other organisms in the

environment. However, sometimes relationships are disrupted by aggression and social

maladaptation, which is more serious when this concerns children and adolescents [1–3].

Every individual has aggression of varying intensity and to a different extent, and it

cannot be entirely ruled out of our lives. At the same time, aggression is an adaptation

mechanism that helps us survive and overcome various obstacles. [4,5]. The difference

between the concepts of aggression and aggressiveness can be summarised in two areas: (1)

aggressiveness is a specific trait, a character trait. It is determined biologically (heredity),

cognitively (learning) and psycho-socially (emotional, along with the influence of the

external environment) [6,7]. This property is within each person to a greater or lesser

extent [8]. (2) Aggression is understood as any form of behaviour intended to harm

someone intentionally [9,10] Aggression can be suppressed (without external expression),

verbal (swearing, writing complaints), against things (destruction, tearing, breaking objects

and things) and against animals and people [11–13]. According to the World Health Report

(WHO 2010) [14], in that period, 1.6 million people lost their lives in the world due to

violent behaviour. Half committed suicide, a third were murdered, and a fifth were lives

lost in armed conflict.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115725

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

2 of 20

Aggressive tendencies are created in humans in the first years of life based on heredi-

tary dispositions, instinctive equipment, upbringing, learning, previous experience, and

environmental influence [15]. Aggression must be controlled, cultivated, regulated and

directed in a pro-socially effective direction so that relations between people and society’s

norms are not disrupted [16].

Many young people cannot integrate properly into society, often accompanied by con-

flicts and personality problems, including increased aggressive behaviour [17]. Prevention

of undesirable behaviour in children and adolescents is one of the necessities for achieving

a certain quality of life in adulthood. In modern society, Kagan [18] identifies adolescence

as the riskiest period on the path to adulthood, and it is a sensitive period for the devel-

opment of risky and problematic behaviour. At the forefront of the interest in preventive

and corrective activities, there is the syndrome of risky and problem behaviour, which

includes truancy, bullying, extreme manifestations of aggression, racism and xenophobia,

the negative effect of sects, sexually risky behaviour, and addictive behaviour [19,20].

Adolescents try to cope with the developmental tasks of the transition from childhood

to adulthood through risky behaviour. Therefore, it is necessary to help them find healthy

alternatives, such as remedial educative programmes, to fulfil the same function [20–22].

The family, peers, and the immediate surroundings of the adolescent have a significant

protective role. Schools and other educational facilities have a special status, operating

across the board in an interdisciplinary, long-term, and continuous manner [23].

1.1. Youth Behavioural Strategy

In this research, attention was focused on the manifestations of aggressive behaviour

in adolescents. The standard procedure for managing aggressive manifestations is to limit

external irritant stimuli, to provide space for the patient to express his/her feelings, or

pharmacological intervention. The recommended methods to manage aggression include

creative activity, physical activity and relaxation exercises. Aggression can also be mastered

by direct experience or observation of other people’s social interactions, i.e., observational

learning [24–26]. The learning model could be family members, people from the immediate

circle, symbolic models from the mass media and virtual reality, or computer games with

violent and brutal themes.

An emerging treatment that utilises wilderness therapy to help adolescents struggling

with behavioural and emotional problems is considered here, i.e., outdoor behavioural

healthcare (OBH) [27]. Wilderness treatment is one option of care that effectively treats chil-

dren and adolescents presenting aggressive behaviour [28]. Wilderness therapy combines

traditional therapy techniques with group therapy in a wilderness setting, approached

with therapeutic intent [29]. Adolescents demonstrated marked improvements in the

following areas: anxiety and depression, substance abuse and dependency, disruptive

behaviour, defiance and opposition, impulsivity, suicidality, violence, sleep disruption,

school performance, and interpersonal relationships. Russel [29] conducted a study last-

ing for 45 days. Adolescent client well-being was evaluated using the Youth Outcome

Questionnaire (Y-OQ) and the Self Report-Youth Outcome Questionnaire (SR Y-OQ) [30].

Complete data sets at admission and discharge were collected for 523 client self-reports and

372 parent assessments. Results indicated that, at admission, clients exhibited symptoms

similar to inpatient samples, which were, on average, significantly reduced at discharge.

Outcomes had been maintained at 12-months post-treatment. [30,31]. Russel [31] evaluated

youth well-being 24-months after the conclusion of outdoor behavioural healthcare (OBH)

treatment and explored youth transition to various post-treatment settings. The results

suggest that 80% of parents and 95% of youths perceived OBH treatment as practical, the

majority of clients were doing well at school, and family communication had improved.

Aftercare was utilised by 85% of the youths and was perceived as a crucial component

in facilitating the transition from an intensive wilderness experience to family, peer and

school environments.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

3 of 20

Other studies also show that participants who had walked in nature reported less

anger and more positive emotions than those who engaged in other activities (walking in

an urban area, sitting quietly while reading magazines or listening to music) [32–35]. The

time spent in nature improves physiological relaxation and the immune function recovery

response [36,37]. Nature therapy can provide emotional healing, decrease blood pressure,

improve a person’s general sleep-wake cycle, improve relationship skills, reduce stress,

and reduce aggression [38,39]. Research studies included in the Stanford analysis [40] have

also found that the natural environment develops potential, and participants gain both

tacit knowledge and necessary depth of knowledge.

1.2. Study Design Based on Forest Programme

Prosocial behaviour is a successful strategy used by human and non-human individu-

als living in stable, long-lasting social groups [41,42]. The human’s limbic system allows

us to experience joy, sadness, fear, and pleasure; these brain structures are common to

humans, mammals, birds, and fish at a significantly lower evolutionary stage [43]. This

finding is followed by several studies dealing with animal emotions [44–46]. The authors

concluded that animals show affection, care for their species, can mourn and face danger

together. Another point of view is provided by Pavlík and Kopcˇaj [47–49], claiming that

processes and interactions in nature are analogous to human social interactions. Rösler [50]

introduces the term “Nature Ideas Exchange”: nature offers many analogies applicable to

practice, via which the principles of prosocial, positive emotional behaviour and coopera-

tion can be presented uniquely, as caring for others, coexistence, cooperation, adaptation,

and innovation occur every day in nature. The constant pressure towards assimilation

has led to high-level specialisations, sophisticated survival strategies, and collaborative

models [50].

We, therefore, assumed that this could work the other way around: if young people

with risky behaviour could not acquire prosocial behaviour patterns such as care, fidelity,

compassion, cooperation and adaptation in their families, this tacit knowledge could be

gained by observation in nature of forest fauna examples. In the forest environment, the

effects of therapy on reducing aggression can be combined with observational learning.

1.3. The Aim of the Research

Eisikovits [51] states that residential education should include the best possible educa-

tion methods, re-education, and psychotherapy. Without these, alternative institutional

care would merely consist of isolation of the child from society. Therefore, an unorthodox

remedial educative programme was performed for adolescents from institutions offer-

ing substitute social care, suffering mental problems with severe risky behaviour (abuse,

criminality, truancy, aggression, early sex life). The established diagnoses of adolescents

are given in chapter 2.1. The research aimed to verify the transformation in adolescents’

attitudes and behaviour based on forest therapy focused on forest animals’ emotional

lives. This research aimed to identify whether probands’ teamwork and social adaptation

would increase. The following question has guided the study: is it possible to reduce

aggressive behaviour with forest therapies based on observing the social behaviour of

forest animals with the simultaneous therapeutic action of Shinrin-yoku and Outdoor

Behavioural Therapy (OBH)?

The following hypothesis was established: Experimental intervention in the form of

forest therapy in groups “A” and “B” will reduce manifestations of aggression compared

to the original values measured before forest therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

Although the idea of OBH and wilderness therapies is remarkable and the study

by Russell [29–31] yields positive results, he admits that OBH and wilderness therapy’s

effectiveness reveals a consistent lack of theoretical basis, methodological shortcomings and

problematic results difficult to replicate [31]. Therefore, we have focused on the primary

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

4 of 20

tool for influencing attitudes and behaviour: remedial educative programmes [52] based on

Shinrin-yoku, observational learning and forest pedagogy methods. Standardised psycho-

diagnostic instruments (projective tests) were used to evaluate adolescents’ aggressiveness

before and after taking part in the remedial educative programme.

2.1. Forest Therapy and Shinrin-Yoku

Forest therapy is a scientifically based method, the results of which are confirmed

by independent research. Its foundations are based on the Japanese Shinrin-yoku tech-

nique [53,54]. It has been reported that forest environments have beneficial effects on

human health: increased natural killer (N.K.) cell activity and in the number of N.K. cells;

increase in intracellular anti-cancer proteins; blood pressure lowering and decrease in

stress hormones (urinary adrenaline, noradrenaline, salivary cortisol). Up-to-date studies

show that, after a few hours in the forest, the level of stress hormones falls sharply, and

the immune system’s activity increases. The parasympathetic nervous system is activated

due to phytoncides-chemicals released into the air mainly by conifers, auditory stimuli of

wild birds singing, and visual stimuli of sunlight shining through the leaves [55–61]. In the

Profile of Mood States (POMS) test, forest environments reduce anxiety, depression, anger,

fatigue, confusion and increase the score for vigour [53], and especially for anxiety [62].

It is a therapeutic method that can be used to prevent the treatment and rehabilitation of

stress disorders and civilisation diseases and help treat mental disorders such as anxiety-

depressive disorders [53]. Kotera and Fido [63,64] demonstrated that the mean scores for

mental well-being, self-compassion, common humanity, and mindfulness had increased

significantly from pre-retreat to post-retreat.

2.2. Forest Pedagogy

Forest pedagogy is forest-related environmental education [65] based on the experien-

tial method, using senses, i.e., based on experiences and feelings. According to Pestalozzi’s

concept of learning with head, heart, and hand, forest pedagogy’s basic principle is the

perception of nature by all senses [66]. Understanding ethical values emerge through the

perception of situations, nature, and other people. Forest pedagogy develops emotional

intelligence, supporting cooperation and teamwork, self-awareness and co-responsibility.

The programme is carried out in groups; the individual is part of the group and is con-

stantly exposed to many social stimuli. Forest pedagogy deals with methods such as

interview, brainstorming, brainwriting, discussion, demonstration, practical activities,

thematic games, competitions, simulation, situational methods and dramatisation, buzz

groups, incident resolution method, maze method, aquarium method, role-playing, stag-

ing, dramatisation, themed games, and competitions [65,67–69]. The following activities

were selected from the PAWS textbook for teenagers: name tag and symbol; animal rights;

eco-audit; desert island.

2.3. Projective Tests as a Diagnostic Tool for Aggressive Manifestations

Projective tests are used to diagnose aggressive tendencies [6]. Doctors use these

tests to determine patients’ aggressive potential as part of a psychological examination.

Projective methods show implicit personality motives, and their results are challenging to

distort by intentional dissimulation. We focused on three projective methods, which have

been standardised as administration, evaluation, and interpretation: the Rorschach test,

the Hand test, and the Thematic Apperception Test, used to examine patients with risky

behaviour [70–72].

Projective techniques confront the tested person with an indefinite situation, to which

he/she will subjectively react according to the interpretation of its meaning. The ambiguity

of the situation can reveal latent personality components that the individual is unaware

of [73]. Projective tests show the examined person’s psychological presentation and relation

to the surrounding world by confronting the individual with a stimulating situation. Indi-

viduals perceive and interpret the tested material to reflect their psychological functioning

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

5 of 20

because they project onto the situation their thinking processes, emotions, needs, anxieties,

and intrapsychic conflicts [6,73].

2.3.1. The Hand Test

The Hand test is a projective technique that should predict aggressive behaviour

and map interpersonal tendencies [70,74–76]. A hand symbol is an essential tool of social

contact and a means of controlling the material world; the hand plays a vital role in body

language and can be a source of pleasure and pain [72]. The Hand test consists of nine

cards on which the shape of a human hand is drawn, and the tenth card is empty. The

respondent should tell what emotion the picture expresses: “What can this hand do”?

Whether the answers express affection, communication, exhibition, acquisition, failure,

reciprocity, dependence, showing off, directive, aggression, activity, passivity, fear or

tension is assessed [77]. These categories are grouped into: (1) interpersonal responses

related to other people; (2) environmental responses related to the impersonal area and the

impersonal environment; (3) maladaptive responses, including formulations exhibiting

weakness, external inhibition, failure to meet needs; (4) answers expressing distance. In

this research, the Hand test was administered, evaluated, and interpreted according to

Lecˇbych [78].

2.3.2. The Rorschach Test (ROR)

The test consists of ten differently coloured boards: black and white, colourful (dark +

red), and coloured boards. The purpose of the test is to determine the projection of thought

processes and personality traits on indefinite objects, which have the form of ink stains

of various colours and shapes [72,79–83]. After presenting the board, the tested person is

asked the question, “What could it be, what is it like?” From the ROR answers, it is possible

to deduce several variables: emotion, aggressive tendencies, personality, interpersonal

relationships, the subject’s relationship to himself, and cognitive functions. The IQ band

can be approximately estimated from the test.

Aggression can be assessed in ROR according to (1) how the stain is interpreted in

terms of its integrity, (2) according to the determinant’s experience, (3) according to the

content of interpretation of humans, animals, and other objects and (4) according to the

occurrence of standard and original answers [84]. For example, the red parts of the card

are often perceived as blood; their reaction will indicate how the test taker manages the

feelings associated with anger or physical harm. The dark and shadowy parts of the card

can cause a situation in which the test taker feels depressed. Pure colour interpretations

are an indicator of affective and extroverted focus. Hue answers indicate the dominance

of the intellect over emotions and affective adaptability. Chiaroscuro responses indicate

moods (mostly dysphoric), suggesting a lack of tendency to control moods and an inability

to control dysphoric reactions. The interpretation of stain shows the intensity and the

importance of social bonds for the patient. Interpretations of animals are the most frequent

content category, and if this value increases, it indicates stereotypes, unproductivity of

thinking, and cumbersomeness or rigidity of thinking.

The answers were evaluated according to the frequency of banal (usual) and original

responses. Banal responses occur in 30% of healthy population protocols. They are

considered an indicator of intellectual contact and social adaptation of thinking. A higher

incidence of these responses may also indicate rigidity or anxious–depressive syndrome.

Administration and scoring in clinical practice were implemented according to Exner’s

Comprehensive System. Individual scores were evaluated based on a quantitative basis,

thus allowing statistical verification [85,86]. A structured procedure characterises the Exner

system for signing and interpreting results. It is a sophisticated system based on detailed

research, extending the perceptual-cognitive basis of the Rorschach method, which affects

diverse aspects of the responses (Exner and Harsa).

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

6 of 20

2.3.3. The Thematic Apperception Test (TAT)

The TAT involves a series of picture cards depicting various ambiguous characters,

scenes, and situations. Respondents must come up with a story for each of them. TAT is

suitable for assessing or capturing the degree of interpersonal conflict and behavioural

disorder [87–89]. The test consists of 31 pictures (boards) on which people (women, men,

children) are drawn in many different life situations. One picture (number 16) consists of

only a white area. Here, the subject has the task of projecting an idea of his arbitrary image

and story: how the story goes and how it ends, what individuals think and feel, why the

situation occurred, and the story’s resolution.

It is assumed that the examined person identifies with the characters and interprets the

situation depending on his/her experience and conscious and unconscious needs [90–92].

2.4. Focus Groups

A focus group was interviewed to obtain the most valuable data from respondents

through their mutual interaction [93], using group dynamics. Interaction structures re-

flected the division of social status (superiority, equivalence, subordination) and relation-

ships between communicators (friendship, indifference, antagonism). The focus of the

discussion was on the self-regulation of behaviour, cognition of emotions, and attention.

The focus group sessions lasted 45 min, and 12 persons participated in each group. The

group members were acquainted with the rules (all interviews take place in the forum, all

members present can participate in the discussion, everyone has the right to express their

opinion, everyone has the right to refuse an answer). There was an effort made for only

one participant to speak in the group at a time, i.e., so that participants could take turns in

expressing their opinions. For critical statements, transcription was performed (including

substandard expressions).

The probands were asked the following questions:

1. Do you think that the social bonds of animals are transferable to the human world?

2. Which animal trait is the least transferable to the human world?

3. Does any animal community remind you of a similar bond in your family? (For

example, the dominant father, like the wolf, is the pack leader.)

4. Which animal community do you like the most and why?

5. In which animal community would you like to be a cub?

6. In which community do you see the most substantial internal ties? Where does a pack

member deploy their own life for the sake of their species? Is there a stronger bond

between a wolf and a wolf cub, a female wild boar and a piglet, or a roe deer and a

fawn?

7. Which animal community offers the best living conditions in packing status, access to

food, safety?

8. Which community is the smartest?

9. Which warning system do you consider the most perfect, and which is the most

altruistic?

The Focus Group aimed to discover attitudes towards the given issues and the most

critical aspects influencing the answers. The moderator (one of the researchers) encouraged

the probands to explain their points of view.

2.5. The Research Group

In the research group were adolescents from three institutions offering substitute

social care with severe behavioural disorders, for which institutional treatment was ordered.

Probands were selected by a specialist in psychiatry and a psychologist based on their

documentation and anamnestic data, from which it was realistic to assume aggressive

behaviour. The research group consisted of 68 probands (43 boys and 25 girls) 12–16 years

old (average age was 14.8 years) along with (1) adolescents from the diagnostic range F

30.0—mood disorders, affective disorders (n = 37); (2) adolescents from diagnostic range F

91.0—behavioural disorders related to family relationships (n = 31) [94]. The entry criterion

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

7 of 20

was aggressive behaviour or tendency (manifest, latent, auto-aggressive, hetero-aggressive).

The research group also consisted of: (3) a control group of 1st-year high school students

with a medical focus, without diagnosed behavioural disorders, aged 15 years (n = 34). In

the control group, the presence of a mental disorder was the exclusion criterion. The control

group was chosen to obtain a homogeneous group and because it was simple to motivate

medical school students for a voluntary psychological examination. In all volunteers from

the control group, the attending physician required a psychological examination focusing

on aggression assessment. Members of the control group participated only in psychological

testing; they did not undergo forest therapy.

2.6. The Research Course, Data Collection and Research Instruments

We used the therapeutic effect of Shinrin-yoku therapy, which was supplemented

with forest pedagogy and observational learning focusing on principles of adaptation,

partnership, and cooperation in forest animals. Forest therapies took place twice a week

for two months (January–February 2020, two hours of therapy), and probands underwent

16 therapies lasting for two hours each in the forest, accompanied by a forest pedagogue

(forester, graduate of a certified course in forest pedagogy), warden, and one of the authors

of this paper. Adolescents were under the constant supervision of experienced mental

health professionals (wardens), who could immediately intervene if any aggressive out-

burst occurred. The maximum group size was eight people according to the internal

guidelines of the institution.

First, the forest pedagogue explained how individual animals in the forest behave

and their specifics. He used demonstration and showed strategic partnerships, coopera-

tion, adaptation, care, loyalty, courage and care using living bees, ants, deer, wild boars,

squirrels, wolves, and birds. Probands worked in teams, searching for parallels between

the forest ecosystem’s commonality and human society through observation, discussion,

brainstorming, mind maps, educational games, and experiences using forest pedagogy

methods [65,67–69].

Probands were examined with a battery of selected standardised diagnostic methods.

The test battery consisted of three standardised projective tests described above. The testing

was part of a comprehensive psychological examination, which also included personality

questionnaires and inventories. Testing was performed in the following order: The Hand

Test, 10 min, Rorschach Test (ROR), 20 min, and Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), 20 min.

For TAT, it is also permissible to select a certain number of boards (for example, 10) suitable

for a certain problem area, and these are exposed during the examination. We also chose

this variant and selected boards for which a higher incidence of aggressive tendencies or

responses was assumed. Selected boards were included: 3 BM, 7 BM, 8 BM, 14, 15, 16

(blank board), 17 GF, 18, BM, 18 GF, 20. The boards were chosen to reflect the patient’s

characteristics and feelings such as suicidality, aggression, depression, feelings about

death, fear, tension, and relationships with parental or important authorities. On the 16th

freeboard, the patient had to create the scene and describe the story in it.

Parametricity was detected by the Shapiro-Wilk test (α = 5%) in both groups for

all questions. The measured values indicated a “continuous variable” character, which

corresponds to the descriptive statistic. Where parametricity was detected, a T-test for

dependent samples was used (α = 5%), and where parametricity was not detected, the

Wilcoxon test (α = 5%) was used [95]. The state of the values before the experimental

intervention and after the experimental intervention were compared. Therefore, two tests

comparing dependent samples were used because an experimental intervention took place

in each examined case.

3. Results

3.1. Parallels found between Prosocial Behaviour of Forest Animals and Human Society

In the example of bee and plant, where bees collect pollen and guarantee the flower’s

reproduction, the probands understood the essence of mutually beneficial cooperation.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

8 of 20

Probands discovered the interconnected and functional system of teamwork and care

for others, in which everyone has a role and place and is willing to accept a part in the

community of beehive and anthill, where the workload of each member of the community

is given (some are responsible for protection and safety; others care for larvae; others

forage). Based on the wolf pack and deer community (Canis lupus, Cervidae), probands

understood that those who can learn from the older generation could expect longer life;

and how teamwork and solidarity work in real-time: the pack or tribe must be collaborative

and pull together. Conformity, tolerance and the necessity to adapt to the environment

was conceived via the swarm and meadow grasshopper (Conocephalus discolour): a flock

of animals behaves and moves like one living organism with a certain logic, without

anyone commanding them. Insects blend in colour with their surroundings or mimic

the appearance of wasps, bees, and bumblebees. Probands detected the principle of

beneficial exchange based on ants (Lasius niger), termites (Isoptera) and aphids (Aphidoidea).

A warning signal of the common jay (Garrulus glandarius) and great tit (Parus major) to

which other animals responded by hiding in safety was understood as worrying about

others. Adolescents summarised that altruism increases in value when we must consciously

and actively deny something to help someone else, e.g., the great tit, who warned others,

found herself in danger because she drew attention to the predator. The fact that energy

invested into social cohesion creates remarkably resilient communities to external threats

was perceived in the examples of communities of wild boars (Sus scrofa). After detecting

that that common squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) takes foreign orphaned cubs into their care,

adolescents stated that there are more variations of maternal love, and whether maternal

feelings arise from a subconscious stimulus or originate in conscious thinking is not critical

to its quality. Probands discovered partnerships based on exchange, liaison and tolerance

between wolves (Canis lupus) and ravens (Corvus frugilegus). They realised that there is

nothing wrong with disparate relationships between predator and blackbirds.

Examples from forest fauna were intentionally described simply, adapted to the age

and mental skills of the probands.

3.2. Evaluation of the Rorschach Test

The findings presented in this section result from psycho-diagnostic evaluations in 68

probands and a control group, examined by a battery of three projective tests before and

after forest therapy. These results emerge from individual measurements for individual

tests.

Group A includes probands with diagnosis F 30.0. affective disorders, 37 persons.

Group B includes probands with diagnosis F 91.0. family-related behavioural dis-

orders, 31 persons. Table 1 presents group averages of ROR test before and after forest

therapy.

Table 1. Group averages of ROR test before and after forest therapy.

ROR

Control

Group

Group A 1

Before

Therapy

After

Therapy

Statistical

Test Results

Group B 1

Before

Therapy

After

Therapy

Statistical

Test Results

Pure colour

answers

0.41

0.83 ± 0.06

0.79 ± 0.05

3 p < 0.01 *

z = 4.62

0.59 ± 0.13

0.51 ± 0.10

2 p < 0.01 *

t = 4.75

Interpretation

of animals

4.99

6.26 ± 0.77

5.87 ± 0.64

3 p < 0.01 *

z = 4.27

6.87 ± 1.14

5.91 ± 0.83

3 p < 0.01 *

z = 4.80

Interpretation

of blood

0.04

0.19 ± 0.05

0.11 ± 0.04

2 p < 0.01 *

t = 8.44

0.13 ± 0.06

0.08 ± 0.02

3 p < 0.01 *

z = 4.11

Contact with

reality

4.72

5.09 ± 0.88

5.01 ± 0.89

2 p = 0.01 *

t = 2.19

4.72 ± 0.79

3.99 ± 0.87

3 p < 0.01 *

z = 3.62

1 Values represent mean values ± standard deviations. 2 T-test for dependent samples (α = 5%). 3 Wilcoxon matched pairs test (α = 5%).

Both tests were used to detect statistically significant differences before and after the experimental intervention. The * character means a

statistically significant difference.

t = 2.19

z = 3.62

1 Values represent mean values ± standard deviations. 2 T-test for dependent samples (α = 5%).3 Wilcoxon matched pairs

test (α = 5%). Both tests were used to detect statistically significant differences before and after the experimental interven-

tion. The * character means a statistically significant difference.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

9 of 20

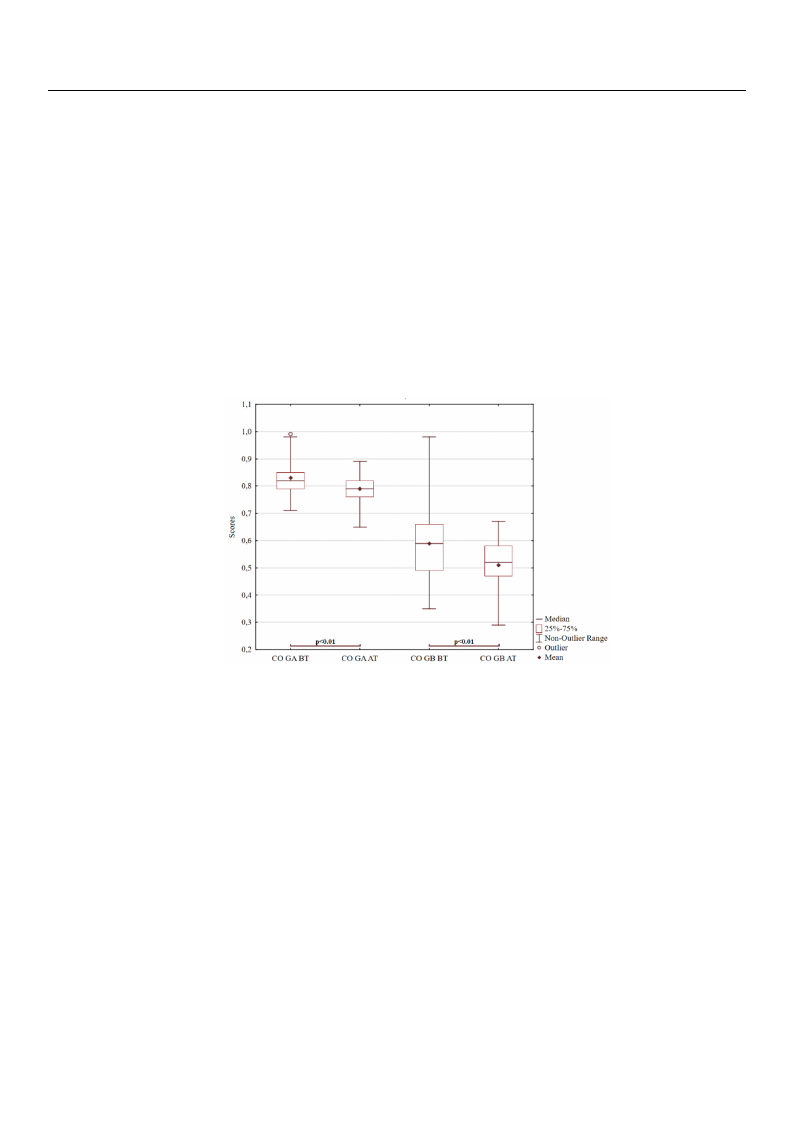

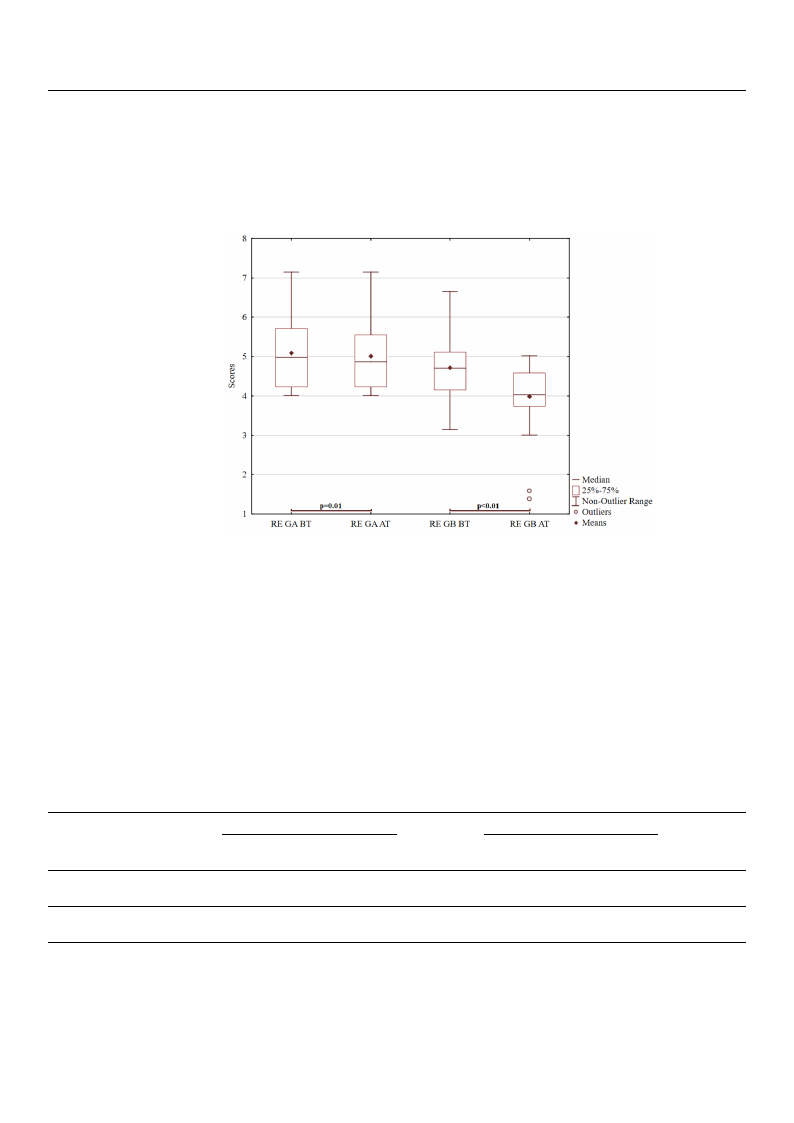

The results show that the experimental intervention has a statistically significan

fect (p < 0.01) on the achieved final values without exception. The experimental inter

tionTrheedruecseusltsvsahluowesthinatbthoethexgpreoruimpesnAta,l Bin,taernvdenatliol nfohuars taessttasti(sctioclaolluyrssig, nainfiicmanatlesf,fbeclot od, rea

(p < 0.T01h)eorne tihseaanchoiteivcedabfilneadl veaclrueeasswe itnhobuotthextchepetfioirns.tTahnedexsepceorinmdenptaliri,natesrvshenotwion in Figu

rIendugcreosuvpaluBe,sfionrbeostththgreoruappsieAs, Bre, danudceadll fvoualruteesstsp(rceovloiuorus,salyniampaplse, abrloinodg, irneatlihtye).upper qua

andTinhecrreeiassaednoltoicweaebrleqdueacrrteialesevinalbuoeths t(hpe<fir0s.t0a1n; dt s=ec4o.7n5d)p. aTihr,iassfsahcotwisn rinefFliegcutreed1.by a sig

IicnnacgnrretoalyusepldoBlw,ofwoerreeersdtqtuhsaterartanilpdeieavsrardleudedusec(vepdi<avt0ia.ol0un1e;sftop=rre4gv.7iro5o)uu.sTplyhBaisp.fpaFecoatrriisntrgheeiflneAtchteegdurobpyupepar,sqitguhnaerifitiocleuanatlntildeyr value

leolwimeriendastteadndbayrdthdeevtriaetaiotnmfeonr tgr(opu<p0B.0. F1o; rzt=he4A.62g)r.oFurpo, mthetohuetlfiierrsvt arlouuenwdasoeflRimOinRatteedsting res

bityisthceletareratthmaetnatd(opl<es0c.e0n1;tszw=it4h.6d2)i.agFnromsedthme fiorosdt rdoiusnodrdoefrsROanRdteasftfiencgtirveesudlits,oirtders had

ims oclsetarsitghnatifiacdaonletsdceinfftiscuwlittyh mdiagnnaogsiendgmimoopduldsiisvoerdteernsdaenndciaeffse.cItnivethdeiisroradnesrws hearsd, purely

tohuermedosatnsisgwniefircsawntedrieffirceuplteyatmedan, argeipnrgeismenptuilnsgiveimtepnudlesnicviietsy. ,Iwn thhiecihr awnsaws ehrasr, dpuerretloy control

cacapoondomldoanpupaeordntenattdeponptatsrntopoesrcdwseioodaecmrolisamnilwnoinneraoarmtrteeemssrs.e,,spi.Ti..eeThe.ah,.it,tsiehstdiehin,netrdedentiipeccdraaneettndesecesesynrntretcioednydudgucitiseomccdehdpdaruiarsgtrlcsieaoihvteniafioatfryelng,ccaetwoslnehactfnirofcodenhlc,utwtrwnsoabhlasr,eanhrwkedaerhtddhueeeenrmreibntoortsthaticiokenonenciadnttlirivsotetyelim.ncottiivoenac

TThheeuunnbablaalnacnedceadffeacftfievcetcivome cpoomnepntodnoemntindaotemd,inwahtiechd,mwaihnilcyhshmowaisntlhyesuhnocwonstrtohlelabulnecontrol

aannxxieietytyefefeffcet.ct.

FFiigguurere1.1R. ORROfRorfpourrpe ucorleoucroalonuswr earns.sNwoetress.fNoroGtreaspfho1r–G6:rBaTpbhe1fo–r6e:trBeTatmbeefnot;rAeTtraefatetrmtreenattm; AenTt; after tre

GmAenGtr;oGupAAG; GroBuGproAu;pGBB; CGOropuurpe Bco;lCouOr apnuswreercso;lAoNurinatnesrpwreetrast;ioAnNofianntiemrpalr;eBtLatiinotenrporfeatantiiomnal; BL in

opfrbeltoaotdio; nREofcobnltoaoctdw; RithErceoalnittya.ct with reality.

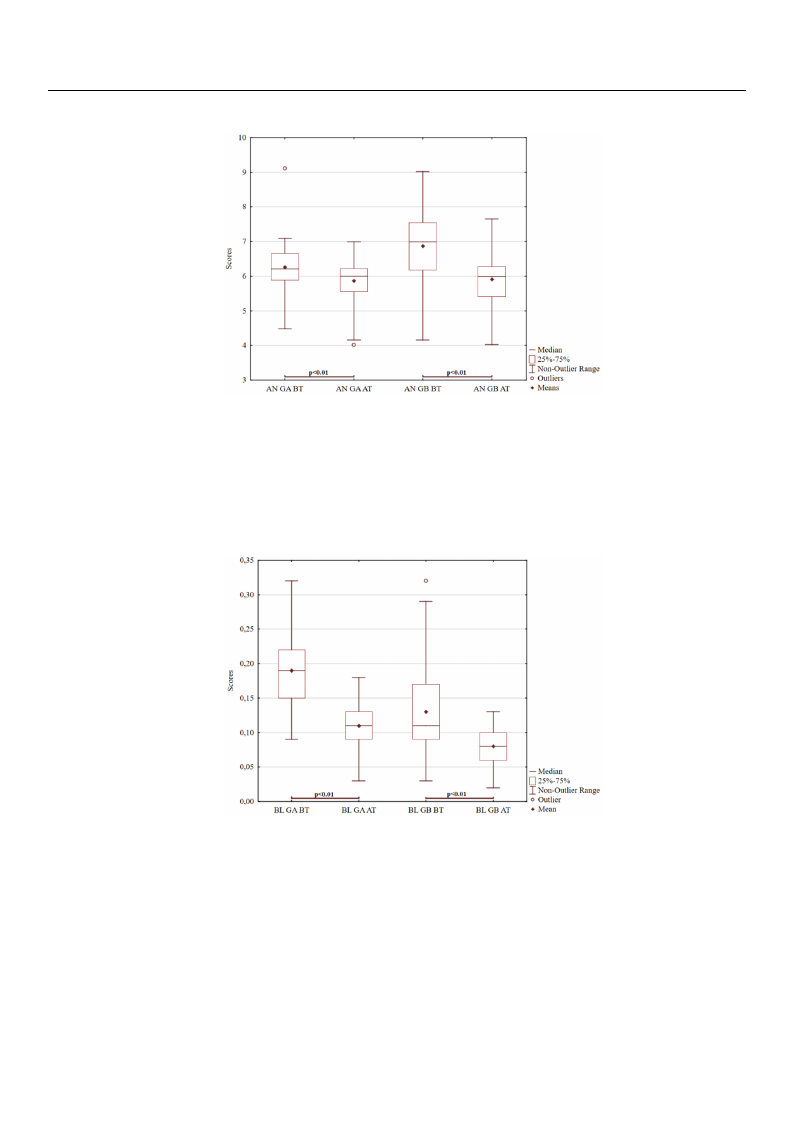

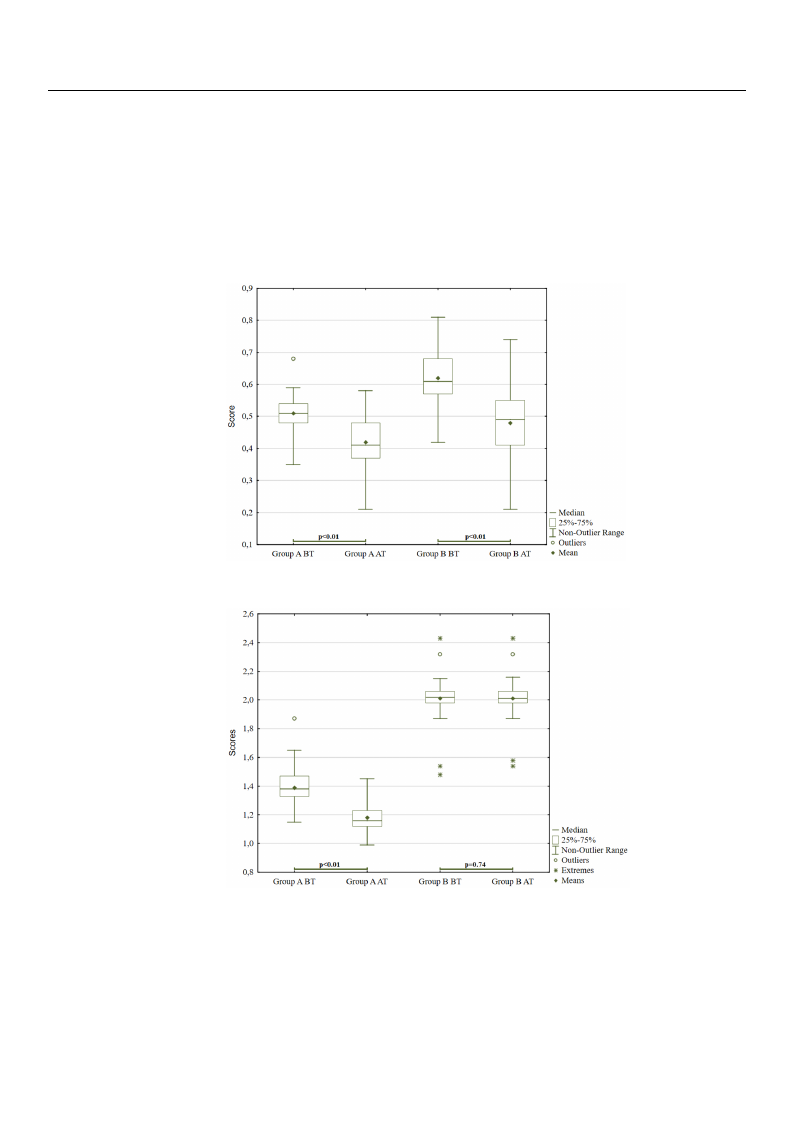

In probands with a family-related behavioural disorder, animal interpretation re-

sponsIens apprpoebaarenddms owstitfhreqauefanmtlyi,lays-rsehloawtendinbFeihgauvreio2u. rIfatlhde iasnoirmdaelrr,esapnoinmseasl eixncteeerdpretation

tshpeonnosrems(a30p%p)e,athreeydamreoosfttefnreasqsuoecinattelyd,waisthsthhoewdenprinessFivigeusyrend2r.oImf ethreelaatendimtoatlhirneksipnognses ex

itnhfleenxiobrilmity(, 3st0e%re)o,ttyhpeeys, aorremoofnteontoansysoofcaiassteodciawtioitnhptrhoecedsesepsr[e6s]s. iTvheesreynisdaronmotieceraeblaleted to th

decrease in both the first and second pair. In the second pair, the positive effect is even

higher because the value decrease is higher than in the first pair. There is also a significant

reduction in the group’s standard deviation in the second pair that became more constant

(p < 0.01; z = 4.80). For group A, an outlier previously appearing as a very high value was

reduced by the experimental intervention. Instead, a new outlier appeared, representing

the low value of evaluation (p < 0.01; t = 4.27).

hbilgehdeercbreeacsaeuisne bthoethvtahlueefidrsetcarenadseseicsohnigdhpearitrh. Ianntihnetsheecfoinrsdt pair., Tthheepreoissitaivlseoeaffseicgtniisfi

rheidghuecrtiboencianutsheethgerovuaplu’sesdtaencrdeaarsde disehvigathieorntihnatnhienstehceofnidrspt paiarirth. Tathbereecaismaelsmo oarseigcnonifsi

(rped<u0c.t0i1o;nzin= 4th.8e0g).rFoourpg’srostuapndAa,radndoeuvtilaiteiropnrienvtihoeusleycoanpdpepaariirntghast baevcearmyehmigohrveaclounes

r(ped<u0c.e0d1;bzy=t4h.e80e)x.pFeorrimgreonutapl Ain,taenrvoeunttliioenr.pIrnesvteioauds,lay napewpeoauritnligerasapapveearryedh,igrhepvraelsueen

Int.

J.

Environ.

Res.

Public

Health

2021,tr1he8de, 5u7lo2c5wedvbayluteheofeexvpaelruimatieonnta(lpi<nt0e.r0v1e;ntt=io4n.2. 7In).stead,

a

new

outlier

10 of 20

appeared, represen

the low value of evaluation (p < 0.01; t = 4.27).

Figure 2. ROR for animal interpretation.

FFiigguurree2.2R. ROOR Rforfoanr iamnailminatleripnrteetraptiroent.ation.

Another item tested was blood interpretation, as demonstrated in Figure 3.

iacssncphpvuoiootcnenlAvtsAdseineeninsnossgtstorhiibetnnoeslhorsvnve,oio,oatrdeallnvvmicidntiiuenntatetemnggersxptdbiebretdelliteoostywsa.toottrVaieddeosadsnrbiisisnnol,woattuaoeersanedrrsipdporirnfrrbitaeetteelanttnortaaxipoanttiriisdegeoosttosnnayitctsnis.iimoaVtaatenuerrar,ldeeirpaifswrooreodffuimtttehaseemtnntaiihornoenraaniesssstxt,ussarcoorataeritccssoneiisudaagdonttifeesndtdidminFinmitgwwogrsauuniipqrtltsesuihhtyrif3ccraa.khotnnRliemycedeesatpxexctnihtoccnisenevisssaosFestneusi,oogrffuroirinnuettnrr3daa.

aqcghugiicrcektselsynivsaeicoitmniv,pautclesueatseg[9gd6ri–se1tsr0se2is]v.seT, ahimnerdpe uiaslnsaxeniseot[ty9ic6.e–Va1ba0lre2iod].ueTcsrheiraersrieetaiintsibnaogtnhsotttihmieceufiarlbistlferaondmdescterhceoeansdeurinrobuontdh

pfqiaurisritc(kpaln<yd0a.s0ce1tic;vota=ntde8.a4p4ga)g.irTeh(spesid<vee0c.ri0em1as;petui=nlsv8ea.s4lu[49e)6.fl–Tu1hc0teu2]ad.teiTocnhres ariseseivsiindaevnnatolitunicebeofaltbuhlcegtrudoauetpciorse,nabssueitsinevbidoethn

ebfivorestnht magnordoreuscpeoscn,osbtnaudnttlpeyvaiienrng(rmpou<opr0eB.0c(1po;n<ts0t=.a0n81;.t4lzy4=)i.n4T.1gh1r)eo. udpecBre(aps<e 0in.01v;azlu=e4f.l1u1c)t.uations is evide

both groups, but even more constantly in group B (p < 0.01; z = 4.11).

FFiigguurree3.3G. Grarfa3fR3ORROfoRr ftoher itnhteripnrteetarptiorentoaftibolonoodf. blood.

sFiiggnuiTfirTehchae3ne.ltGaldsartaisfftifte3eirtmeRenmOcteeRstwetfeosdatrsetwdhobaewssienacrtosvenerctpdoarcnientttaawgtciriotothnuwproieftBahbli(lrtopyeo,<adal.0ict.cy0o1,r;dazicnc=go3rtd.o6i2Fn)i,ggbuturote Fn4io.gtuSintraegtir4sot.iucSpatlalAytistically

(npif=ic0a.T0n1ht;edt l=iaff2se.t1ri9et)neimcnetwtheesactseoodnbtrwsoelarosvfecrdoeanilntiatygc,trwowhuiipcthhBirs(epaan<liet0ys.s0,e1an;ctzciao=lrm3d.ie6nd2gi)a,ttbooruFbtiengtowutreeienn4g.nreSoetudatspisAtic(apl=ly

atnn=ifd2icm.a1on9t)tividneisftfhienertechnoecnseutrwbojelacost’fosrbiensateelrirtvayce,tdiwoinhnsigcwhriotihus tpahneBee(xspstee<rnn0ta.i0la1eln;mzvie=rdo3ni.am6t2oe)nr,tb. euTthtweneroaetnnignnegeoerfodthusepanAd(mp =o

ritne=alt2he.s1et9as)teuinibnjtdehecext’cissoinnnttrehorelarocaftnirgoeenaoslfitw1y–i,8twhpohtihinctehs.eiTsxhtaeenrnneoasrmsleeonnftvitahileromrenaemldeeisanttatot.erTibnhedetewxraiesne5ng–e7npeooefidntshtsae. nrdeaml oe

Winedatekhxeeniisnugibn(jsetihcgten’isrfiacinantgetelryaobcfeti1loo–wn8s4pwpoointinhttss.t)hTieshcehxantroearcnmtearliosetfincthvoefirmroenoarmle eseesnvttae.treeThmineednretaaxnl idgsies5oo–rdf7etprhsoe.inrtesa.lWe

WoreWeienfnntedefaiiaannraekndggkxntanaeti((sissesosyssiin,ggcsni,arnnicnrt.iieaahffb.tnii,eicceofaaorbnfannroeanutttlhlilfngtyyooydeu,sbbeoionneerwfdllpao1ohusi–wwonyt8ic“sphdp4t4iosocoysppinetcnhoosoh,toiitsnonsus.estthgvTsseah))eshrtre,sieie.sstphneAccsevonhyhewrcaaimrhnorreocaralorppccdefattsaeewtytshrrheciiiitseeshhststioiri,goccepcntaohaioofilgetffhrncesaisimm”tentiavsbtool,tueyrrecteedaohiebngsasfiodeevncvvveeiietteexstih7rrvoieeeespriromm5mdwi–neeee7otnfnnsirtpclttaidiaasoltllsinddotiisrss.oomWrredd

arWelsteoaarpkdanathetoisolsongc,aiicn.ael..b, Iefnocfroretuahnsoedsdeicnwonphtsrooyl“codhforseneaosli,ttysehmvaaeryre,eftohpreseywxcahomroplpdlaew,thbieitehdsu,oecthotoegrnasim”tiobvrueetdsheevafeivcreeittshoerirmwe

dretparredssaivtieodni,sio.red.,efrowrithoasperwedhoom“indaoncneootfsshtearreeottyhpeywanodrlrdigwidityhiontthheinrsk”inbguotr hoathveer their w

of fantasy, irrationality, or autistic thoughts. An increase significantly above 7 points i

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021,a1l8s, o572p5athological. Increased control of reality may, for example, be due to a11mof o20re severe

depressive disorder with a predominance of stereotypy and rigidity in thinking or othe

neurotic features, e.g., incredibly obsessive. Depressive and the lowest psychotic pro

nbeaunrdotsichfaedatuthreesh, eig.gh.,eisntcraevdeibralygoebvsaeslusievse.oDnetphriessssicvaelean. Ad tfhteerlofowreessttptshyecrhaoptiyc,ptrhoebraenwdsas a pos

hitaivdethienchriegahseestianvethraegeinvdailcuaetsoronofthtihs escdaleeg. rAeefteorffaodreaspt ttahteiroanpyo, fthtehrienwkiansgatpoossoitciviael reality

iwnchriecahseisininthdeiciantdeidcabtoyrcoofmthme doengarenesowfeardsa[p1t0a3ti]oannodf tchoirnrkeisnpgotnodsosctioaltrheealuitsyu, walhsiochciiasl rules o

isnodciiceattye,dubsyuacollmyma ognuanraswnteeres o[1f0c3o] nanfodrmcoirtryestpootnhdes etonvthireounsmuaelnstoncieaclersuslaesryoffosorchieutym, an inte

ugsruaatilolyna. guarantee of conformity to the environment necessary for human integration.

FFiigguurree44. .GGrarfa4f 4RORROfRorfocornctoancttawcitthwrietahlirtey.ality.

33..33..EEvvaaluluataitoinonofotfhtehHe aHndanTdesTt est

of resFFprrooonmmsetshthbeeeHfHoarnaednfodTreeTssettstrtheserueralstpusyl(t,psinr(ecpslureendstieendngtirenedaTciatniboTlneas2be)l,xepw2ree),snswoinetigcneinodtteiacrephdeigrashoehnriagflrhedeqisruteafrnneccqyeuency o

arnesdpaonnsinescrbeeafsoerdedfoegrereset tohferpaspycyh, oinpcaltuhdolionggyr. eaRcetsipoonnsseexsperxepsrseinssginigntderisptaenrscoeneaxlpdreisstsance and

naonn-inadcraepatisveedfodremgsreoef boefhapvsiyocuhroinpcartehaoselodgfyee. liRnegsspoofnsstreessse, xwperaeksnsienssg, odrisatvaonidceanecxeporfess non

iandtearppteivrseonfoarlmorseonfvbireohnamveionutarl icnocnrteaacstse.dTfheeesleinagnswofersstraersesc,hwareaacktnereises,dobryawvoeaidkaenecde of inter

cpoenrtsaoctnwalitohrreenalvitiyr.oAnmhiegnhtsaclocroenistaaclwtsa.yTshpeastehoalnosgwicaelrsanadrerecflheacrtascptreorbisleemdsb[y6]w. Aeaftkerentheed contac

sweciothndreraoluintyd. oAf thesigtihngscinortheeisacatilnwgaoyust praattihoo(AloOgRic)ailnadnexd, aredfeleccretsasperionbbluelmlysin[g6,]t.hArefattesr, the sec

doensdtruroctuionndooffptreosptienrgty,inlyitnhge, aecstcianpgeso,urat criaatlidois(AcrOimRin) aintiodne,xs,paradyeicnrge,aasbeuisne bouf olltyhienrgs,, threats

pidinnretetosodtlliercerutraecandtncioaecg,enag, noraedfnsdspnieronotnhepo[te6hl,rio1stm0lyi4,s,wm1ly0ai5wsn].fgao,suenfsodcu.anTpdhei.ss,Tirhnadicseixainlidsdecioxsncirssiimdcoeirnnesaditditooenrbe,edsaptvroaablyiedinaign,vdaaicblaiudtosirenodofficoatthoerros

Table 2. Group averages forpTrheedHiacnteddTeasgt gcarteegssoiroiens r[e6la,1te0d4t,o10th5e].distance from reality and the level of pathology before

and after forest therapy.

Table 2. Group averages for The Hand Test categories related to the distance from reality and the level of pathology before

and after forest thCeroanptryo.l

Hand Test

Group

Hand Test

Non-adaptive

behaviour

Control

0.G38roup

Group A 1

Group B 1

Statistical

Statistical

Before

After

Therapy GrouTpheAra1py

Test Results

Before

Statistical TeTstherapy

After

GrTohueprapBy1

Test Results

Statistical Test

Before Ther- After Ther-2

0.51 ± 0.a0p6y 0.42 ± 0.a0p8y

p

t

<

=

0.0R1e*sults

6.35

0.62

Before Ther-

± 0.09apy 0.48

±

A0.f1t1earpTyhe2rpt-

<

=

0.01

5.38

*Results

Non-maPadanathiipfooetulsiotvragetiicboanelhs av-

0.910.38

1.39

±0.501.15±

0.06

1.18

±0.402.0±9

0.08

2

p

t

<

=

02.0p1<* 0.01

7.1t2= 6.35

*

2.01

±

00.1.672

±

0.029.01

±

00..1468

±

0.131zp==00.3.7324pt

<

=

0.01

5.38

*

Patholo(1tαgaVi=tacilao5u%lnesm)s.rBeapontrhiefseteesns-ttstwheeraeri0uth.s9em1dettoicdmeteeacnt 1s±t.a3ts9itsat±nicd0aal.l1ryd5sdigenviifiac1tia.on1nt8.d2±ifTf0e-.rt0eens9tcefosrbdefeop2reeptnad=<ned70n..at10fs2t1aemr*tphleesex(pαe2=ri.m50%1en)±.ta30lW.i1ni7tlecrovxeonnt2iom.n0a.1tTc±hhee0d*.1pc6haairrsactetesrt

3 p = 0.74

z = 0.33

1 Vmaelaunessarsetaptrisetisceanllyt tshigeniafirciatnhtmdieffteircenmcee.an ± standard deviation. 2 T-test for dependent samples (α = 5%). 3 Wilcoxon matched

pairs test (α = 5%). Both tests were used to detect statistically significant differences before and after the experimental

intervention. The * character meaTnhseaesxtpaetirsitmiceanlltyalsiignnteifrivcaenttidoinffehraesnaces.tatistically significant effect on the achieved

final values, except for pathological manifestations in group B (p = 0.74). Statistically

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, x FOR PEER REVIEW

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, x FOR PEER REVIEW

12 o

12 of 2

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 572T5 he experimental intervention has a statistically significant effect on12thofe2a0 chieved

nal vTahlueeesx, pexecriemptenfotarlpianttherovloengtiicoanl mhaasnaifestsatatitsitoicnaslliyn sgirgonuifpicBan(tpe=ff0e.c7t4o).nStthaetisatcihcaiellvyedsigfi

nicaalnvtadluifefes,reenxcceepst(pfo<r 0p.a0t1h)owloegriecoalbmsearnviefdesitnatgioronus pinAgrinouvpalBue(ps =fo0r.7n4o)n. S-atadtaispttiicvaellybeshiganviif

siaicgnandnifitpcdaaitnfhfteodrleiofnfgecirecesanl(cpmes<a(0np.i0<f1e)0swt.0a1et)iroewnoesbr(esteo=rbv6see.3dr2vi;endt g=irn7o.ug1rp2o)uA, painnAdviainnluvgaerlsuofeuosprfnoBor innn-oavnda-aludpateipsvtfeiovberenhoanv-iaodu

bateinvhdeavpbioaeuthhraoavlnoidogupicraat(lhtom=loa5gn.i3icfa8el)s.mtaTathnioeifnreest(aitsti=onn6os.3s(2tta;=tti6=s.3t7i2c.;1at2l=l)y, 7as.n1i2gd)n,iainfnigcdarionnutgpdroeBucpirneBavsianeluvianelsuvfeaoslrfuonerosni-nadpaapt

isBFnnFtlnlFgneooiio—igiroovcpnggggooueia-iuiunnussracctbierirdhadpagtgeeehlola5,nnphi6lpm.6msioaiaftfFosgisgiiaviarvhicmihcrngincaeonoaoouaiineuofnwbulfwretpeeetmrpsssshs,ic6tr(ctgastaahttaohhonsnvthath=bimaiaiiiaofnfioooatne5ten,gucwnsn,g.aistepr3dinseasnn;8r((t;st(ottp)ittphot.hb=cthah=ahnhaTe=er5tesnea0eh,r.f0nrd3(e.ifie7pe.rni8gs7rr4si)ae=e4sagtt.)a;rhtr)Tn0preiietesnpei.hhia7nsfsfiaeeni4gisprrgrcir)gor,peresaenior,ttnecnsiiaohutfispictrhtugfeapceinlairferyaptciooiesiBrrncs,pueBaspt.titelptsibpTh.ayiaccsoTaetatBhaiahifirvatl.shibnelhcostTeyoiinoloiscpfhvostoaaasliaifegosialcntcatlgiiatgheyfcdccnnanaoiiteaossccidblaeliifttaogsgliixbeilgeccpnrstgxleaiahriepdctgarfinerpaeabherdectmlnahpclmaeeedpproinnhecceehhedmtlroiaalycieceeydclmsrnealcaaeeeybnbrollsce,aelelmeareyiynabslell,osleoeauaiiiuwbelnnlswltil,suueianuitbnosgtnrisituotnvanrhitrgtttnorataevhhegaritulranteuedeortwphlodereuutsieiwudhsenesipBnpeescsiii—FsonenBeicng—iFpodnauiangvirptdnteuheharorp5ii

agvvraeolruuagepes,;vseaovlmueenes;ipnervotehbniasinngdtrhsoisuagrper,otsuhipge,nrteihfeiacrreaenadtrleeyvdaieavbnioatvnietnidnandividvidieduxuatarllses.m. ely below otherwise averag

values; even in this group, there are deviant individuals.

FFFiigigguuurerree5.55T.. hTTehhHeeHaHnadannTddesTTtefesostrtfnfooornrn-naodonan-pa-tadidvaeappbtietvihveaevbibeoheuhar.vaivoiuoru.r.

FFFiigigguuurerree6.66T.. hTTehhHeeHaHnadannTddesTTtefesostrtfpfoaortrhppoalatohtghoicolaollogbgiecihacalavlbibeoheuharavalviopiuohureanrloapml hpeenhnae.onmomenean.a.

333.4..44. ..ETEEvovvalaaeullvuauataailottuinioaonotnef otothffhetethTheTheTehTmehhmaeetmimacataiAtctipciAcpAepArppcppeeppertrecicroeecnppetTptiieotosinnot nTTeTessett,stwe decided to use an interpretation

systemTToobeeefvovraaelluusacaottereintthghe.eITtThchaeenmmbaeatitcciocnAAcpluppdpeeerdcrectephpatittoiionnnpTrTeosebts,atn,wdwes ewdeditcheicdpiededresdotontaoulistuyesdeainsaonirndtieenrrtsperrpetraettiaot

aaaassaagnyynggngdssgdgdrtteprreepespermmssosrrisospvoiibbpeevpveneeeteefesfnnotointstersedryineinetetytdyndsosecctectdnyoonooercbrcdpiydiynyreneegbp1gbpsy.8rsy.r%eIi1eItos1t.8snsc8s%ic,a%oiaton.nhn.ne,b,btfehtreheecqecofuonrfenercneqlccuqluyuduedoenefdencrdycetyhsotphafootafrntiersnsieenpsspopdrpnooersncboersabesenaasddsneedsddceswrbcewryiatesh2iaet7shdp%eedpbrayesnbordy2sn7oha2%nel7itat%eaylrinotadyd-nisdhdoiershtdoeeerrtdore

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

13 of 20

3.5. Evaluation of the Hypothesis

Based on the evaluation of projective tests by statistical methods, it is possible to

confirm that the experimental intervention in the form of forest therapy combined with

observational learning in groups “A” and “B” led to reduced aggressive behaviour.

3.6. Evaluation of Focus Groups

Results of focus groups discovered the attitudes to the given issues and the most criti-

cal aspects impacting newly identified knowledge. The alternation of agents’ statements

indicates group dynamics. Individual agents are marked with the abbreviation A + No.

(A32) “I understood that human babies and animal pups need the education to master

the rules in adulthood.”

(A5) “I felt sorry that squirrels also take care of foreign cubs when my mother did not

take care of me.”

(A18) “I understood it in mimicry; who wants to survive must adapt to the environ-

ment.”

(A17) “I liked how wolves could make friends with ravens; it is an entirely different

species.”

(A9) “I thought nature was cruel, and only the predator won. I did not expect animals

to help each other. I always thought that in nature, it works who with whom.”

(A21) “I was surprised that the bonds between the animals are similar to family life.”

(A9) “It seemed strange to me to compare us to animals, but finally, I enjoyed it.”

(A3) “Even in animals, there are inferior members of the tribe who get to eat only at

the end, which is similar to humans; when an individual is weak, he will never be the

pack leader.”

(A2) “I liked that even a tiny weak individual (tit) can protect species from a predator,

which can be much larger and more robust.”

Probands discovered some parallels between their own and forest animals’ behaviour.

For example, when a warden approaches, one warns the others. If they are caught in

the act, the youngest weakest individual is sacrificed because he/she receives the lowest

punishment. In case of damage, they try to camouflage it like that found in nature. They

can also come together as a pack and speak with one voice when needed. The crucial out-

come of focus groups is the finding that probands positively evaluated the compassionate

manifestations of animals and reported advantages, such as reduction of anxiety.

4. Discussion

Institutions providing substitutional social care are not a frequent place of research.

They are closed communities and are therefore demanding to obtain data. What is happen-

ing inside is not sufficiently researched. This research had the ambition to understand the

social reality better examined, even if only to a small extent, given its modest scope.

4.1. Evaluation of Projective Tests

TAT is more associated with social adjustment, and ROR more associated with thought

disorders. Both methods describe the personality in its entirety and can be used to assess

instinctual component, emotions, complexes or repressed tendencies. In the first round

of testing before forest therapy, a more significant increase in average values was found

for responses related to emotional instability and less controlled impulses in responses

involving animals, blood, and social reality checks. These interpretations are very often

associated with an excess of intrapsychic tension, acute distress and anxiety. Against the

background of tension, there are often insufficiently assimilated and integrated aggressive

impulses, easily activated by various irritating stimuli from the environment. Comparing

these research results with the conclusions of Gacono and Meloy [106], similar results were

obtained in the monitored traits (colour and chiaroscuro responses). This suggests the good

validity of this projective test, especially when assessing the affective component.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

14 of 20

Similarly, in his research, Morávek [107] found statistically significant values (0.1%) in

the number of aggressive responses. These were primarily responses containing offensive

animals or humans. Interestingly, the Zw responses (interpretations of white spaces and

interfaces that can be considered a sign of an aggressive or negative attitude) proved to be

statistically insignificant, despite the literature and practice experience. In this research,

similar outcomes were found.

In the projective Hand Test, statistically significant differences between groups for

some items, including non-adaptive behaviour and pathological manifestations, were

observed. These categories were associated with an increased incidence of psychopatho-

logical features and weakened contact with reality. No significant values were found

in the predictor of aggression (AOR) or AGG (number of aggressive responses). The

aggressiveness index expresses the relative weight of socially positive cooperative atti-

tudes compared to directives and aggressiveness. Some authors, such as Klicperová [108],

Morávek [107], Volkova [109] and McGill [110], consider that this index is an accurate

evaluation of predicted aggression. In her research, Klicperová [108] focused on two moni-

tored traits, AGG-aggressiveness and CRIP-damage. She evaluated the answers containing

the monitored features on a three-point scale. So-called “percentage of aggression from

the obtained gross scores”, which had a significant value, was calculated. In his research,

Morávek [107] also focused on selected traits (AGG, number of aggressive responses; CRIP,

responses involving damage to the object; and DIR, responses involving directive direction,

regulation or control of others) and found statistically significant values on the scale of

aggression. Probands on the AOR or AGG scale did not achieve statistically significant dif-

ferences due to many factors, such as calming of the situation. Besides, the manifestations

of aggression change over time and circumstances.

In the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), statistically significant differences between

the groups when assessing hetero-aggressive, auto-aggressive tendencies or topics were

not observed. Responses in which hetero-aggressive tendencies predominated were most

common in psychotic probands. Auto-aggressive tendencies predominated in probands

with personality disorders and depressed probands. However, activated defence mecha-

nisms that change the assessed patients’ experience and behaviour play a role, significantly

suppressing aggressive tendencies.

4.2. Evaluation of Forest Therapy

Forest therapy has been modified with elements from wilderness therapy and OBH,

Shinrin-yoku and forest pedagogy. We must distinguish between wilderness therapy and

wilderness experience programmes, boot camps similar to military recruit training in a

wilderness environment [111]. Actual wilderness therapy occurs under the supervision of

a licensed mental health professional (psychologist, psychiatrist) who works with partici-

pants and can provide individualised treatment plans regularly monitored and evaluated.

Due to the physical, cognitive, and social demands of wilderness therapy, this form of

treatment may not be effective with older adults, young children, or people with specific

physical disabilities. The approach may also be ineffective or unsafe for people experi-

encing severe or chronic mental health issues such as dementia, schizophrenia, and other

similar conditions.

Due to these limitations, OBH was combined with Forest therapy based on the Shinrin-

yoku methodology, observational learning and forest pedagogy. Our outcomes correspond

to scientific findings by other authors [55–61] concerning anxiety, depression, anger de-

crease, and mental well-being. In this research, the positive influence of the forest envi-

ronment on the development of potential acquisition of tacit knowledge was confirmed.

Contemporary studies of Shinrin-yoku present fewer participants’ results than this research

(12 male university students, 14 adolescent sexual offenders, 22 participants, 25 Japanese

students, 27 girls aged 12 to 14 years) [56,57,62]. Furuyashi [57] conducted a more extensive

study with 155 participants classified into two groups: those with and without depressive

tendencies. Shinrin-yoku therapy’s length also varied: three-day retreat [64], six times a day

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

15 of 20

for 15 min [55]. Before and after forest therapies, reduced items related to psychopathology,

irritability, restlessness, emotional instability, egocentrism, relativity, and negativism were

evaluated.

4.3. Limitations and Possible Follow-Up Research

This research has potential limitations relating to the application of projective tests

application and the number of probands due to the institutes’ capacity. The question is

whether the Rorschach test reveals the patient’s psychological centre and the process of

their thoughts because probands can censor their thoughts before utterance. The evaluation

can also be skewed by the evaluator’s personality, classifying the patient’s answers into

predetermined categories. All three tests place significant demands on the experience and

correct interpretation of the person testing the probands, i.e., the evaluator (psychologist or

psychiatrist). The tests are sensitive to the immediate mental state of the subject, so a whole

battery of tests is carried out, which is evaluated by an experienced doctor-psychiatrist or

psychologist, who has the anamnestic data of patients in order to assess progress. However,

selected projective tests seem to be a suitable tool for predicting aggressive behaviour.

These methods can be recommended if trained personnel are used in a broader test battery,

mainly due to the test’s high reliability and validity (especially for detecting aggressive

behaviour). Therefore, based on a single projective test, there should be no clear conclusions

or even a diagnosis (for example, the test subject’s immediate mental state). Projective tests

should be compared with other methods (observation, questioning, objective personality

tests, etc.).

Focus groups also generate certain limits. Focus group participants can censor re-

sponses according to their demands; they can respond differently under the weight of these

circumstances than they would have done if they had been alone with the researcher. The

respondents may also conveniently conform to the majority’s opinion or, conversely, may

rebel against it. In both cases, however, misleading data could be provided.

Prior research studies relevant to this paper are limited (i.e., no study would show

the principles of cooperation to reduce aggressive behaviour on the examples of forest

animals). This limitation can be considered a challenging opportunity to identify gaps and

present further development in the field. This article aimed to compare the effectiveness

of methods and approaches to reduce the rate of aggressive manifestations, which is a

possible topic for further research via a longitudinal study with a more significant number

of probands.

This research is complemented by several studies that have already examined the

effect of wilderness therapy or Shinrin-yoku on reducing aggressiveness. So far, no study

has combined wilderness therapy, Shinrin-yoku, forest pedagogy, observational learning

and the use of projective tests in one piece of research, compared to previous ones. The

contribution of this research can be seen in the purposeful connection of the mixed methods

approach and testing probands before and after forest therapy by selected projective tests.

The paper’s novelty can be found because forest animals’ emotional life has become a

mirror with an educational aspect for young people with aggressive behaviour. Science

tends to degrade animal emotional manifestations as mere instincts [112], although several

scientific works are based on similar animal emotional expressions [113,114], covering only

selected partial aspects.

5. Conclusions

The importance of this research is evident due to the increasing number of aggressive

manifestations of adolescents. This paper aimed to verify the transformation in adolescents

‘attitudes and manners based on a mixed-methods approach and identify whether probands’

teamwork and social adaptation has improved while simultaneously reducing aggressive

manifestations. Thanks to the triangulation of methods, we obtained interesting empirical

material that would not have been reached by using only one data collection technique.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

16 of 20

Projective tests provided information about the personality’s internal structure, balance

and maturity, perceptual-cognitive level, and reality contact.

The assessment or measurement of aggression is very complex. Projective tests evalu-

ate personality traits, reliably differentiating predispositions to aggressive manifestations

rather than aggressive behaviour as such. Projective tests are less transparent, so it is

difficult for the tested person to respond deceptively to cover up his/her antisocial and

aggressive tendencies. The results suggest that the combination of forest therapy and pro-

jective methods appears appropriate and complementary and improves clinical knowledge

in assessing aggressive behaviour.

These results can be relevant for policymakers and stakeholders involved in medicine

and education to utilise these proposals to design and develop successful strategies and

tools to promote this innovative approach. Forest animals showed adolescents ways of

communication, cooperation, and adaptability, care for others, i.e., characteristics without

which no community can work.

Author Contributions: Conceptualisation, K.M., J.Z. and R.D.; Methodology, K.M., J.Z. and R.D.;

Validation, J.Z., M.R. and K.M.; Formal analysis, J.Z., Z.V. and K.M.; Data curation, J.Z.; Writing—

original draft preparation, K.M. and R.D.; Writing—review and editing, K.M. and J.Z.; Supervision,

D.K., R.D., M.R., Translation, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the

manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by National Agency for Agricultural Research of the Czech

Republic NAZV, grant numbers QK1920272.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of

the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Institute of

Hospitality Management in Prague (protocol code HTV19-01 from 9 September 2019).

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the

study.

Data Availability Statement: The data presented in this study are available on request from the

corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to further evaluation within the

research.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank M. Kadlecova, Psychiatrist, in memoriam, for her kindly

help by evaluating projective tests.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Bandura, A.; McDonald, F.J. Influence of social reinforcement and the behavior of models in shaping children’ s moral judgment.

J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 274–281. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

2. Geller, B.; Greydanus, D.E. Aggression in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health Care 1981, 1, 236–243. [CrossRef]

3. Cubbin, C.; Santelli, J.; Brindis, C.D.; Braveman, P. Neighborhood context and sexual behaviors among adolescents: Findings

from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2005, 37, 125–134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. Routt, G.; Anderson, L. Adolescent Violence towards Parents. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2011, 20, 1–19. [CrossRef]

5. Benson, M.J.; Buehler, C. Family Process and Peer Deviance Influences on Adolescent Aggression: Longitudinal Effects Across

Early and Middle Adolescence. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 1213–1228. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

6. Harsa, P.; Žukov, I.; Csémy, L. Possibility of Aggressiveness Evaluation by Means of Projection Tests. Cˇ eská A Slov. Psychiatr. 2009,

105, 20–26.

7. Rahayu, N.A.; Hamid, A.Y.S. Relationship of verbal aggresiveness with self-esteem and depression in verbally aggressive

adolescents at public middle school. Enfermería Clínica 2021, 31, S281–S285. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

8. Hutami, N. Death Instinct Manifested through Passive Aggresiveness and Its Social Effects in Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener”.

NOBEL J. Lit. Lang. Teach. 2017, 8, 1–8. [CrossRef]

9. Garandeau, C.F.; Cillessen, A.H.N. WITHDRAWN: From indirect aggression to invisible aggression: A conceptual view on

bullying and peer group manipulation. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2006, 11, 641–654. [CrossRef]

10. Wilson, L.; Mouilso, E.; Gentile, B.; Calhoun, K.; Zeichner, A. How is sexual aggression related to nonsexual aggression? A

meta-analytic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 24, 199–213. [CrossRef]

11. Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. Human Aggression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 27–51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

17 of 20

12. Miczek, K.A.; Almeida, R.M.M.; Kravitz, E.A.; Rissmann, E.F.; Boer, S.F.; Raine, A. Neurobiology of Escalated Aggression and

Violence. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 11803–11806. [CrossRef]

13. De Bono, A.; Muraven, M. Rejection perceptions: Feeling disrespected leads to greater aggression than feeling disliked. J. Exp.

Soc. Psychol. 2014, 55, 43–52. [CrossRef]

14. World Health Report WHO Home Page. Available online: https://www.who.int/whr/2010/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2020).

15. Morel, K.M.; Haden, S.C.; Meehan, K.B.; Papouchis, N. Adolescent Female Aggression: Functions and Etiology. J. Aggress.

Maltreat. Trauma 2017, 27, 367–385. [CrossRef]

16. Tripathi, N. Aggression among School Adolescent and its Association with Socio-Demographic Characteristics: A Cross Sectional

Study. Indian J. Youth Adolesc. Health 2020, 6, 7–13. [CrossRef]

17. Detullio, D.; Kennedy, T.D.; Millen, D.H. Adolescent aggression and suicidality: A meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2021,

101576. [CrossRef]

18. Kagan, J. Etiologies of adolescents at risk. J. Adolesc. Health 1991, 12, 591–596. [CrossRef]

19. Donovan, J.E.; Jessor, R.; Costa, F.M. Syndrome of problem behavior in adolescence: A replication. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988,

56, 762–765. [CrossRef]

20. Hamanová, J.; Csémy, L. Rizikové Chování v Dospívání a Jeho Vztah ke Zdraví; Triton: Prague, Czech Republic, 2014; ISBN

9788073877934.

21. Jessor, R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J. Adolesc. Health 1991, 12,

597–605. [CrossRef]

22. Jessor, R.; Turbin, M.S. Parsing protection and risk for problem behavior versus prosocial behavior among US and Chinese

adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1037–1051. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

23. Costa, F.M.; Jessor, R.; Turbin, M.S.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C. The Role of Social Contexts in Adolescence: Context Protection

and Context Risk in the United States and China. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2005, 9, 67–85. [CrossRef]

24. Sasaki, S. Observational Learning and Conformity: Experimental Evidence. SSRN Electr. J. 2014. [CrossRef]

25. MacDonald, J.; Ahearn, W.H. Teaching observational learning to children with autism. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2015, 48, 800–816.

[CrossRef]

26. Tye, K.M.; Allsop, S.A. The Amygdala and Observational Learning. Sci. Trends 2018. [CrossRef]

27. Russell, K.C. What is Wilderness Therapy? J. Exp. Educ. 2001, 24, 70–79. [CrossRef]

28. Gass, M.; Russell, K.C. Adventure Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-

1-130-58443-3.

29. Russell, K.C. An Assessment of Outcomes in Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Treatment. Child Youth Care Forum 2003, 32, 355–381.

[CrossRef]

30. Wells, M.G.; Burlingame, G.M.; Lambert, M.J.; Hoag, M.J.; Hope, C.A. Conceptualization and measurement of patient change

during psychotherapy: Development of the Outcome Questionnaire and Youth Outcome Questionnaire. Psychother. Theory Res.

Pract. Train. 1996, 33, 275–283. [CrossRef]

31. Russell, K.C. Two Years Later: A Qualitative Assessment of Youth Well-Being and the Role of Aftercare in Outdoor Behavioral

Healthcare Treatment. Child Youth Care Forum 2005, 34, 209–239. [CrossRef]

32. Alvarsson, J.J.; Wiens, S.; Nilsson, M.E. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Nature Sound and Environmental Noise. Int. J.

Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 1036–1046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

33. Pinto, R.; de Jonge, V.N.; Marques, J.C. Linking biodiversity indicators, ecosystem functioning, provision of services and human

well-being in estuarine systems: Application of a conceptual framework. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 36, 644–655. [CrossRef]

34. Jordan, M. Ecotherapy as Psychotherapy—Towards an Ecopsychotherapy. In Ecotherapy; Palgrave: London, UK, 2016; pp. 58–69.

[CrossRef]

35. Song, C. Physiological Effects of Nature Therapy: A Review of the Research in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13,

781. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

36. Browning, M.H.E.M.; Shipley, N.; McAnirlin, O.; Becker, D.; Yu, C.-P.; Hartig, T.; Dzhambov, A.M. An Actual Natural Setting

Improves Mood Better Than Its Virtual Counterpart: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Data. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

37. Lymeus, F.; Ahrling, M.; Apelman, J.; Florin, C.d.M.; Nilsson, C.; Vincenti, J.; Hartig, T. Mindfulness-Based Restoration Skills

Training (ReST) in a Natural Setting Compared to Conventional Mindfulness Training: Psychological Functioning After a

Five-Week Course. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

38. Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J.

Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

39. Phillips, L. Using Nature as a Therapeutic Partner. Couns. Today 2018, 60, 26–33.

40. Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Roth, N.W.; Holthuis, N. Environmental education and K-12 student outcomes: A review and

analysis of research. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 49, 1–17. [CrossRef]

41. Kummer, H. Analogs of morality among non-human primates. In Morality as a Biological Phenomenon; Stent, G.S., Ed.; University

of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978; pp. 31–47. ISBN 978-3820012118.

42. Broom, D.M. Sentience and Animal Welfare; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781780644035.

43. Oschinsky, L. The Problem of Parallelism in Relation to the Subspecific Taxonomy of Homo Sapiens. Anthropologica 1963, 5, 131.

[CrossRef]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725

18 of 20

44. Bekoff, M. Animal Emotions: Exploring Passionate Natures: Current interdisciplinary research provides compelling evidence

that many animals experience such emotions as joy, fear, love, despair, and grief—We are not alone. BioScience 2000, 50, 861–870.

[CrossRef]

45. Palagi, E. Sharing emotions builds bridges between individuals and between species. Anim. Sentience 2019, 3. [CrossRef]

46. Dawkins, M.S. Animal Minds and Animal Emotions. Am. Zool. 2000, 40, 883–888. [CrossRef]

47. Pavlík, J.F.A. Hayek and the Spontaneous Order Theory, 1st ed.; Profesional Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2004; ISBN 80-

86419-57-6.

48. Kopcˇaj, A. Rˇ ízení Proudu Zmeˇn; Silma: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 1999; ISBN 80-902358-1-6.

49. Kopcˇaj, A. Spirálový Management; Alfa: Praha, Czech Republic, 2007; ISBN 8086851710.

50. Rösler, S. Naturschutz am Ende. Naturwirtschaft als Zukunftsstrategie. In Land Nutzen—Natur Schützen: Von der Konfrontation zur

Kooperation; Evangelischer Presseverband: Karlsruhe, Germany, 1995; pp. 34–79. ISBN 978-3872101136.

51. Eisikovits, R.A. The Future of Residential Education and Care. Resid. Treat. Child. Youth 1991, 8, 5–19. [CrossRef]

52. Hewstone, M.; Stroebe, W. Introduction to Social Psychology: A European Perspective; Portál: Praha, Czech Republic, 2006; ISBN 80-

7367-092-5.

53. Li, Q. Effets des forêts et des bains de forêt (shinrin-yoku) sur la santé humaine: Une revue de la littérature. Rev. For. Française

2018, 135. [CrossRef]

54. Miyazaki, Y. Shinrin-Yoku: Lesní Terapie pro Zdraví a Relaxaci—Inspirujte se Japonskem, 1st ed.; Grada: Praha, Czech Republic, 2018;

ISBN 978-80-271-0778-0.