religions

Article

Is Sacred Nature Gendered or Queer? Insights from a Study on

Eco-Spiritual Activism in Switzerland

Irene Becci * and Alexandre Grandjean

Institute for Social Sciences of Religions, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland;

alexandre.grandjean@unil.ch

* Correspondence: irene.becci@unil.ch

Abstract: Among eco-spiritual activists in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, gendered notions

such as “Mother Earth” or gendered “nature spirits” are ubiquitous. Drawing on an in-depth

ethnographic study of this milieu (2015–2020), this article presents some of the ways in which these

activists articulate gender issues with reference to nature. The authors discuss the centrality of the

notion of the self and ask what outputs emerge from linking environmental with spiritual action.

We demonstrate that activists in three milieus—the New Age and holistic milieu, the transition

network, and neo-shamanism—handle this link differently and thereby give birth to a variety of

emic perspectives upon the nature/culture divide, as well as upon gender—ranging from essentialist

and organicist views to queer approaches. The authors also present more recent observations on

the increasing visibility of women and feminists as key public speakers. They conclude with the

importance of contextualizing imaginaries that circulate as universalistic and planetary and of relating

them to individuals’ gendered selves and their social, political, and economic capital.

Keywords: eco-spirituality; holistic practices; New Age; eco-psychology; neo-shamanism; Switzerland;

ecofeminism

Citation: Becci, Irene, and Alexandre

Grandjean. 2022. Is Sacred Nature

Gendered or Queer? Insights from a

Study on Eco-Spiritual Activism in

Switzerland. Religions 13: 23.

https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010023

Academic Editors: Catrien

Notermans and Anke Tonnaer

Received: 11 July 2021

Accepted: 26 November 2021

Published: 28 December 2021

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Copyright: © 2021 by the authors.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

1. Introduction

The scholarly literature on contemporary spirituality has often highlighted that beyond

the large variety of practices, beliefs, and views that can be observed, there is a core set of

ideas that is shared. As early as the 1990s, Paul Heelas (1996, p. 22), for instance, studied the

centrality of the “self” within New Age practices and Françoise Champion (1995) pointed

to the primary importance that is given to personal experience, in particular to bodily felt

emotions, and optimism in what she termed the “mystico-esoteric nebulae”. Moreover,

some notions such as “cosmic” or “healing energies”1 are particularly used in the realm of

spirituality that refers to Earth or to nature as a sacred entity. It is in this realm that what is

termed “eco-spirituality” emerged; that is, a set of ideas, discourses, and practices articulating

religious and environmental considerations in reference to authors calling for a holistic

understanding of societies, the human mind, and their environment, such as Ernst Haeckel,

Rudolf Steiner, Arne Naess, and Gregory Bateson (Choné 2016). A considerable number of

studies have concentrated on the tendency of eco-spiritual initiatives to dichotomize into male

and female and essentialize this distinction (Rountree 1999). In this article, we shall contribute

to these debates and the literature by offering an analysis of observations made between

2015 and 2020 among Swiss eco-spiritual activists, concentrating on those who commonly

use notions such as “Mother Earth” (Grasseli Meier 2018) or “nature spirits” (Chautems and

Bressoud 2013; Di Marco and Cruz 2018). We deepen some reflections we have elaborated on

previously regarding the way essentialist ideas were reproduced despite subversive claims

by eco-spiritual activists (Becci et al. 2020) in the public space. We also rely on more recent

findings by authors who have documented emerging “queer spiritual places” in this context

(Browne et al. 2010; Lepage 2018; Pike 2001). Their analysis brings nuanced insights into the

way gender is performed or subverted by practitioners of contemporary spirituality. These can

Religions 2022, 13, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13010023

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions

Religions 2022, 13, 23

2 of 15

subvert conventional gender categories, roles, and boundaries, as well as reproduce them in

many ways. Along with existing studies on contemporary spirituality and ecological activism,

the present article elaborates on the multiple articulations observed in the field between three

core notions: the self, nature, and gender. In order to go beyond the simplistic accusations that

often concern ecofeminist views such as essentializing biological and cultural attributes, the

analysis is here extended to a large variety of empirically found actors who consider one or the

other of the three notions sacred. We shall see that there is a link between a gendered view of a

sacred nature and of one’s self. To clarify our point, we shall firstly introduce our methodology

and the empirical material used. The article then proposes to map the different postures

ranging from essentialism to queer approaches according to three milieus found within our

fieldwork that are not neatly separated: (1) the New Age and holistic milieu; (2) the transition

network; (3) neo-shamanism. It then offers some insights into empirical hubs and contexts

where these actors actually meet with feminist key speakers, giving rise to new popular

ecofeminist expressions. In the concluding discussion, the importance of contextualizing

imaginaries that circulate as universalistic and planetary will be stressed and a link established

with individuals’ gendered selves and their social, political, and economic capital.

2. The Gendered Dimension of the “Spiritualization of Ecology” in Switzerland

Since 2015, in the context of the COP21 Summit in Paris and the diffusion of the Laudato

Sì encyclical by Pope Francis, a high number of conferences, public demonstrations, urban

festivals, and cultural productions in Switzerland have started to contain new forms of

eco-activism that include spiritual aspects. Among their different inspirational sources, we

found frequent references to neo-shamanism, neo-paganism, green theologies, and holistic

approaches. Emotional, subjective, and sensitive ways of being environmentally active

have also received growing public attention. We identify this process as a “spiritualization

of ecology” (Becci and Grandjean 2021), which is a notion that comes close to what Hubert

Knoblauch has termed “the popularization of religion”; that is:

Religious symbols and forms of religious communication that belonged predom-

inantly or exclusively to the “sacred” religious sphere have been disseminated

into other cultural spheres and used in non-religious cultural contexts, most

importantly in popular commercial media and leisure culture. (Knoblauch 2008,

p. 147)

Through this process, certain symbols, metaphors, or practices become disaffiliated

from specific institutions and sometimes become so strongly integrated into an existing

cultural setting that they appear as “banal” (Griera and Clot-Garrel 2015). In the case of a

spiritualization of ecology, this term refers to the popularization of motives, practices, and

symbols (previously present in a narrow circle of environmentalists inspired by esoteric,

oriental, or ancient traditions) within a larger semantic and practical field of environmen-

talism. Interestingly, these motives, practices, and symbols imply gender attributes and

references linked to a sacralized Nature.

During public events organized within the milieu of Swiss ecological activists, we

observed, between 2015 and 2020, that numerous key speakers articulated religious and

spiritual issues with calls for sustainable and societal transformations. By placing emphasis

on what they call “spirituality”, aiming to, as they state, reconnect with nature and adopt

a new posture of articulating the practice of meditation with militancy (Monnot and

Grandjean 2021), these key speakers offered discursive and practical tools for individuals

to transform themselves in order to change the world.2 They consider nature and local

biotopes at times sacred, harmonious, or even motherly/caring and opposed to humanity,

which is presented as being responsible for the current collapse in the Anthropocene.

At the beginning of our ethnographic observations of this eco-spiritual milieu, we found

that although these approaches joyfully embraced a gendered language, by referring, for

instance, to feminine and masculine values, there was no feminist emancipatory agenda in

this eco-spiritual sub-milieu (Becci and Grandjean 2018).

Religions 2022, 13, 23

3 of 15

During the subsequent four years, we continued our ethnography and have since

observed new trends and social innovations appearing in this realm. We therefore com-

plement our initial research conclusions with an analysis of more recent observations that

show that militant and affirmative claims about feminism have now arisen in this milieu.

The variety of eco-spiritual activism we have observed seems to span from essentialist to

queer approaches, all putting forward emic views on what is termed “the feminine” or “the

masculine”. In order to offer a broader understanding of this oscillation, we refer to the

writings of the English philosopher Timothy Morton. Morton has extensively commented

upon what he calls “ecological thought” (Morton 2012, p. 19); a perspective that considers

all dimensions of life as being ecologically entangled. In that manner, we shall summa-

rize our informants’ views and postures about nature, knowing that it is a “promiscuous

concept used daily in a multitude of situations by a diverse array of individuals, groups,

and organizations” (Castree and Braun 2001, p. 5), paying particular attention to how

these are gendered. We also refer to Timothy Morton’s reflections on a queer ecology

(Morton 2010), providing a non-essentialist and non-binary approach to ecology, also ob-

served in the field. Morton argues that, at a philosophical level, there cannot be any entity

such as “Nature” (with a capital “N” to stress its exterior and constructed character) sepa-

rated from other elements of life (Morton 2010, p. 16). The representation of an allegorical

and fantasy Nature is, according to Morton, anchored in Romanticism. Taking up his idea

that the more we know about a subject, the less we are actually able to develop a simplistic

understanding of it as a discernible whole, we consider that such a view of Nature is

eminently metaphorical and rarely tangible. In our discussion, we aim to ground this

philosophical insight in our sociological data. We consider that the way the entity called

“nature” is gendered or queered mirrors worldviews held within society and social milieus.

3. Methodology

We carried out two successive research projects on eco-spiritual activism in Romandie

(the French-speaking part of Switzerland) between 2015 and 2020—more precisely in the Le-

manic Region (the region surrounding Lake Geneva). We interviewed or had ethnographic

conversations with over 70 key eco-spiritual activists in agriculture, holistic spiritualities,

environmental advocacy, or Christian Church organizations and observed over 50 public

eco-spiritual events. We observed that due to the social vivacity of the area, the social

“stocks of knowledge” (Schütz et al. 1974) and practices regarding gender, ecology, and

contemporary forms of spirituality that circulate are mixed up with and integrated into

each other after having been partly challenged or contested. Our first outline of the concept

of a “spiritualization of ecology” arose out of these multisited expressions, together forming

a set of ecological references, ideas, and framings that intertwine, gaining public visibility

and audibility because they were present in many different milieus, one echoing the other.

In this article, we focus particularly on those public key figures and events entangling

spirituality, ecology and gender in visible ways—across books, conferences, workshops,

theater plays, street mobilizations, exhibitions, concerts. We rely on the triangulation of the

observations and the biographical insights of 18 key public figures, which we can roughly

subdivide into three types of spiritual eco-activism: holistic practitioners close to a New

Age spirituality, the transition or eco-spiritual network, and neo-shamanic practitioners.

A common feature of their sociological profiles is that they have privileged socio-cultural

capital and academic diplomas. Their ages range from early thirties to retirement age (over

65 years). Moreover, they often practice liberal or caretaking professions. Most of our infor-

mants are also authors of numerous books and other publications, some academic, some

belonging to the literature on self-development, eco-spirituality, eco-psychology, Chris-

tian contemplation, creative rituality, sacred places, etc. They practice eco-psychological

coaching and New Age rituals related to the earth or neo-shamanic rituals.3 Interestingly,

the majority of these key figures are men. At first sight, this finding is surprising as the

literature indicates that contemporary spirituality is a milieu where women are most ac-

tive and predominant (Sointu and Woodhead 2008). It is less surprising, however, if we

Religions 2022, 13, 23

4 of 15

consider that at the public events we attended, the speakers were invited as experts on

ecological issues, and that in the realm of scientific expertise, a gender gap is still at work

and women are strongly underrepresented (Schwaiger et al. 2021). Introducing spiritual

views into scientific expertise during public communication is, moreover, an aspect that

might diminish scholarly legitimacy, a risk that established senior men take more easily.

As we argue in the following, however, since the year 2017, women have become

increasingly present in these milieus as key speakers in public workshops and at confer-

ences. Their increased presence comes in the wake of ecofeminism and goddess spirituality

being raised in a number of crucial texts translated into French during the intervening

years.4 New practices and interests such as rituals revolving around menstruation are also

more commonly found in these milieus, in mainstream cultural productions, as well as in

feminist organizations. The concern over gender issues, addressed in critical or ritualized

guises, is yet another recent stance in the eco-spiritual milieu that we have studied.

In addition to semi-structured interviews, we conducted observations at publicly

accessible conferences, round-table events, urban festivals, workshops, and spiritual guided

tours in parks where these key figures participated. In our ethnographic fieldwork, we

paid attention to the broad environment the key figures had access to; that is, we took

into account the realm of cultural production, training and education days, workshops,

conferences, festivals, etc., they were involved in and documented through notes, photos,

and recordings what we observed.

4. Theoretical Considerations: The Entanglement between Gender, Nature and the Self

We adopt a constructivist perspective upon what counts as spirituality and religion

(Beckford 2003), considering emic discourses and practices as well as controversies arising

out of their social definitions. We specifically consider that what is often referred to as

spirituality in Western societies is part of a language about “expressive selfhood” and an

“attempt to reconcile individuality with relationships in a way that can do justice to both”

(Sointu and Woodhead 2008, p. 267). In a similar manner, we analytically consider nature

as a polysemic and controversial notion whose study needs empirical grounding in the

discourses and practices of social actors. Taking Philippe Descola’s considerations about

Western ontologies into account, within our analysis we try to avoid sharply dicotomising

between what is named nature and what is named culture (Descola 2005). We follow a

more phenomenological view, such as that elaborated by Tim Ingold. In particular, we

empirically translate his idea that nature and the environment also rely on a “sentient

ecology”, “consisting of the skills, sensitivities and orientations that humans develop

through a life-long experience in a particular environment” (Ingold 2000, p. 24). If the

category of nature is a cultural construct, it is also an experiential and relational approach to

biotopes, which humans learn to pay attention to and integrate into their local cosmologies.

In our pluralistic societies, these cosmologies are made of secular and religious cultures that

interlace. Therefore, there is not one eco-spirituality but a multitude of ways to understand

and practice the link between what is considered spirituality and what is considered ecology

or nature.

Following Linda Woodhead, we consider gender as a “constitutive element of social

relations based on the perceived differences between the sexes” and as “a complex and

interwoven set of historically constructed relations of domination” (Woodhead 2012, p. 31).

Furthermore, following Marylin Strathern, we consider that the common anthropolog-

ical dichotomy of male and female “provides models of boundaries and relationships”

(Strathern 2016, p. 330). Firstly, in relation to such gender boundaries, social actors define

something called “the feminine” in stark contrast, sometimes in a complementary way,

to what stands as the masculine. Secondly, when objects, symbols and social actors are

attributed a specific gender, they are set in relational models and are given ontological limi-

tations: for instance, gendering the planet Earth by calling it “Mother Earth” usually places

emphasis on its reproductive and nurturing value while excluding its “dark” (Morton 2018),

uncanny, and dreadful dimensions. The notion of “queer” entered scholarly debate through

Religions 2022, 13, 23

5 of 15

Teresa De Lauretis’s (1991) proposal to reclaim a derogatory term that initially referred to

people not falling into one of the two categories proposed by a binary vision of gender.

This notion provided an impetus, to scholarly and militant milieus alike, to go beyond a

binary categorization and deconstruct the notion of gender in order to avoid confining

criticism to the opposition between men–women on the one hand and gays–lesbians on the

other. In the realm of ecological critics, “queer” has nonetheless added to the multiplicity

of voices, be they human or not, from the Global South or not, that are stuck and are

victims, in a non-normative and anti-essentialist manner, of what is often referred to as the

Anthropocene (Bauman 2015; Tola 2018). We shall see to what extent the term “queer” does

this when it appears in the field of ecological discourses we have observed and analyzed,

especially regarding seemingly essentialist and constructivist stances.

5. Varieties of Gendered Eco-Spirituality: From Gender Polarity to Queer

In the public spaces of the two main cities where our enquiry took place, Lausanne and

Geneva, the presence and circulation of iconographies, discourses, and slogans entangling

references to gender, ecology, and spirituality are overwhelming. Roughly every week a

new book, public event, or invitation to what is called a “women’s circle” or a “holistic treat-

ment” mentioning masculine or feminine energies in relation to nature or the environment

is published or circulated. Some of the ecologically committed actors within the milieu of

contemporary spirituality were part of the New Age trend, although often stressing the

particularity of their own practices. Others explicitly referred to neo-shamanism, while a

large number of persons belonged to a loose so-called “transition network” articulating

gender issues with spirituality and ecology. We shall discuss which gender views arise

within these three eco-spiritual milieus.

5.1. The New Age and Holistic Milieu: Gender Complementarity in Nature

We met a number of holistic ecologists during the urban eco-festivals taking place in

Lausanne and Geneva over several years (Becci and Okoekpen 2021). We then followed

some of them in their activities that drew on gender notions and conducted longer in-

terviews. When analyzing their life-course narratives, we noticed that they had entered

the “holistic milieu” (Sointu and Woodhead 2008) smoothly, often after having worked

for years in the realm of diplomacy, banking, or in social or international organizations,

toward which they had adopted a critical stance and ended up quitting. Quite early on,

they had also distanced themselves from the religious traditions they had loosely been

socialized in. They have thus passed from a situation of a “distanced” to an “alternative”

(Stolz et al. 2016) religious profile in their life course. After having spent some years “seek-

ing” (Sutcliffe 2000, p. 19) different religious expressions, they shared an understanding,

as Sutcliffe writes, of “spirituality [ . . . ] as an expressive and holistic mode of personal

behavior encouraging strategic interaction on the part of the practitioner between natural

and supernatural realms”. The “fuzzy boundaries and malleable praxis” this notion of

spirituality entails allow them to “occupy ambiguous, multivalent ground between realms

elsewhere more clearly categorisable (and hence potentially open to stigma) as ‘religious’

and ‘secular’”(Sutcliffe 2000, p. 20), for instance in the therapeutic or musical realm. They

first started their own spiritual practice and, with increasing ecological awareness, they

added more explicitly environmental thoughts and metaphors to their practices and refer-

ences. The figure of nature became important in assessing what they called an “authentic

self” as well as in elaborating on gendered and bodily analogies between the planet, animals

or plants, and human beings.

In line with most of the literature on the New Age subculture, which insists on an

emphasis put on “a higher self” and “on spiritual experience” (Hanegraaff 2002, p. 259),

these practitioners are “encouraged to draw inspiration and guidance from within their

own minds and bodies rather than from external texts, traditions, or human authorities”

(Hedges and Beckford 2000, p. 172). Often considered the achievement of the individualism

of modern societies, New Age features the self in its “symbolic center” (Heelas 1996, p. 22).

Religions 2022, 13, 23

6 of 15

In the particular context of ecological activism, however, the “authentic self” so constituted

would reveal itself in interaction with the environment, “as naturally [ . . . ] attuned to

the rhythms of the natural world” (Hedges and Beckford 2000, p. 172). Thereby, if this

ecologically-oriented holism has a universalizing tendency, it is meant to “foster a sense of

compassion for others, rather than individualistic self-improvement” (ibid.).

To illustrate how gender comes into play in this context, we take the example of a Swiss

group active in spirituality rooted in geomantic ideas. The members regularly organize

visits to what they call “sacred places” to allow people to “reconnect with themselves

through the spirits of nature” (Di Marco and Cruz 2018, p. 10). In their book Nature Spirits

in the Parks, Steeve Di Marco and Gorka Cruz describe the various spirits they have sensed

in a great number of public parks in the Lemanic Region. In a Geneva park, they have

identified, among numerous other spirits, the presence of Isis, the Egyptian goddess, which

they describe as follows: “Isis produces an oscillation in the region of the belly. It opens

the access to the deep femininity present in us. She allows us to feel the rhythms of the

nature that surrounds us.” (Di Marco and Cruz 2018, p. 46) In another nearby park, there

is, according to them, a “ram man” described as follows: “This ram-man invites us to tilt

our heads forward: the eyes focus on a goal. A will to achieve a goal emerges. Our mind

is focused and we cannot be disturbed by what is happening around us.” (Di Marco and

Cruz 2018, p. 48).

When we participated in one of the visits to the spirits in this park on a Sunday

afternoon, the guide showed us how to position ourselves and to be attentive to the

energies we felt; that is, we had to stop controlling our bodies and watch what shape they

would spontaneously take. He clearly exhorted our little group not to think but to listen

to our sensations. This way we could experience the energies that were present and were

traversing our bodies. In order to identify what type of spirit it was, he suggested attributes.

He asked us whether we were sensing a feminine or a masculine energy. Some participants

would go along with these lines, while others would not really follow these categories,

sometimes even answering that they felt both or felt androgynous energies. The guide

would then explain that a feminine energy was airy, light, and bright and that a masculine

energy was strong, focused, and rooted. In an interview, one of the guides told us how he

identified these spirits:

I scan a place, I will feel I will connect, ah, I will feel the feminine vibration and I

will say to myself, ah, it is perhaps a fairy who is there. Ah, there it is surely an

elf considering that it is straight. (Fieldwork interview, Lausanne, March 2019)

These practitioners consider that nature spirits are present at precise positions all

over the world and fulfill specific functions there; some are “cosmic”, others are “telluric”

(Di Marco 2017). They take care of daisies, they support the growth of trees, they watch

and care for the natural order and its balance. For them, humans can enter into contact

with these spirits, and the latter can move in time and space if needed. In this cosmology, a

spiritualized nature easily entangles with gendered considerations about the self, either

through the adoption of binary and stereotypical attributes or in a more nuanced and

subtle way. While feminine or masculine energies are not individualized (i.e., attributed to

individual persons), the association of the categories with specific contents still reproduces

essentialized notions of gender. What characterizes this view most is that the spirits are not

standing in tension or power relations to each other. The feminine and masculine energies

constitute a polarity without being hierarchically ordered. The spirits are rather active

against human drifts such as a so-called “disenchantment of the world” led by Western

modernity with its cold rationalism and colonialism. In our informants’ views, if humans

become tuned to the Nature spirits, they can operate a counter-cultural return to authentic

and enchanted selves through spiritual motives. Such ideas appeal to a larger public

that participates regularly on the tours and visits without necessarily adopting the whole

cosmology. Gender complementarity and nature harmony remain at the core of this view.

Religions 2022, 13, 23

7 of 15

5.2. The Transition Network: The Neutralization of Gender through Organic Metaphors

We also observed a tendency toward spiritualizing an ecological “self” among prac-

titioners of the transition movement, which calls for an “inner transition”, “voluntary

sobriety” and economic degrowth. Composed of mostly institutionally established actors,

these practitioners operate as ecologists and environmentalists in the first place. They rely

on institutional scientific validation and a high level of education (often PhD and profes-

sorial level) and are recognized as experts in the realm of ecology. Positions in academia,

politics, Christian organizations, and NGOs fostered these key speakers by also providing

them with a title offering institutional resources and public legitimacy. Concerning their

religious upbringing, these informants have in common a primary Christian socialization,

but they had distanced themselves from religious belonging in their early adulthood. The

distance from institutional religion resulted in particular from the experience of biographi-

cal ruptures, such as divorce or illness. Our informants also shared a grounding of what

they called their current “spiritual rediscovery” in something they said had already been

present in their childhood, such as nature experiences or specific encounters or trips to

Asia or North America. When talking about nature, they delineate symbolic and operative

boundaries to distinguish what is not natural but artificial or cultural.

This group gathers around several emblematic authors, such as eco-activist and eco-

spiritualist Joana Macy, who has theorized rituals and group exercises known as the “Work

that Reconnects” (Macy and Brown 2014). According to this author, who is close to Califor-

nian figures and radical ecologists like Starhawk, John Seeds, and Gary Snyder, the current

state of ecological and social crisis is leading individuals into a state of despair, helplessness,

and anxiety about the future, which the techniques of the “Work that Reconnects” are meant

to remedy. In a similar fashion to the holistic milieu, this rhetoric calls for a re-enchantment

of the whole world:

Now, in our time, three rivers, anguish for our world, scientific breakthroughs

and ancestral teachings, flow together. From the confluence of these rivers we

drink. We awaken to what we once knew: we are alive in a living earth, the

source of all we are and can achieve. Despite our conditioning by the industrial

society of the last two centuries, we want to name, once again, this world as holy.

(Macy and Brown 2014, p. 14)

These authors propose an eco-psychology explicitly interlacing references to exotic

ancestry and to new modes of human relations to nature conceived as sacred or holy.

Because of these references, the terms “eco-psychology” and “eco-spirituality” are used

in an interchangeable way depending on the audience. Their approach stands on the

fringes of the modernist distinction between what counts as religious and what counts as

secular, thus promoting an encompassing category that mediates and negotiates the values

and languages of these two spheres (Fedele and Knibbe 2020, pp. 13–16). This allows

institutional actors of secular organizations to bring eco-spiritual references into “what

may be called the new, global ‘knowledge class’” (Knoblauch 2014, p. 98). In Switzerland,

some authors, inspired by Joanna Macy’s work, are mediators between eco-spirituality and

eco-activism and participate, on the one hand, in blurring the categories between religion

and the secular while, on the other hand, reinforcing the religion and ecology nexus.

As in Macy’s work, gendered dimensions are contained in the practices and discourses

of the eco-spiritual activists we met, although they do not publicly elaborate on them.

For instance, key speakers of the transition movement often explained how they tried to

articulate an “internal transition” with an “external” one, thus advocating for a radical

transformation of the self, while in return also affecting societal structures, moral and

political norms, and means of production and consumption. The emphasis was then placed

upon every individual self, a non-gendered self, promoting practices such as the “Work

that reconnects”, in which individuals, regardless of whether they were men or women,

religious, spiritual or overtly non-religious, had to express their deep feelings regarding

the degradation of the environment. Instead of elaborating on gender issues, key speakers

of the transition network inserted them into larger philosophical considerations tending

Religions 2022, 13, 23

8 of 15

toward universalization. The value given to self-expression or to emotion was not framed

as a gendered, that is, cultural, issue here.

For instance, on the stage of one of the main theaters of Lausanne in March 2019, two

authors, a Swiss philosopher we had already met and interviewed and a French author and

biologist, were invited for a public conversation. The French author writing about what he

calls “collapse”, Pablo Servigne, started crying while detailing a video that struck him of an

orangutan trying to resist bulldozers razing its habitat on the Island of Borneo. During that

evening, he also asked the audience, 300 persons, including us, to undertake a brief exercise

inspired by Macy’s ”Work that Reconnects”: we had to greet our neighbor, look him/her in

the eyes, and for two minutes describe in detail how we felt every time we thought about

the loss of biodiversity worldwide. The other person had to remain silent, but be receptive

and empathetic toward our words and feelings. Then, we exchanged roles for another

round of two minutes. During that evening, Pablo Servigne also gave a description of the

enchantment of the “Web of Life”:

The Web of Life has not unwoven for nearly 3.8 billion years, billions of years that

[have spawned] the first bacteria, which are our ancestors. It is more than a string,

it has woven a web, abounding, bushy and multicolored for billions of years.

We are interdependent. We all have here strong interdependency with other

living organisms outside this room. We are more than this room, and this radical

interdependency is magnificent, she is moving and touching us. Additionally, in

fact, it leads us toward something that is beyond us. That we even have a hard

time imagining. It is something similar to sacred, what the Anglophones call

“Wholeness”, the feeling of unity with the Whole. (Our translation)

These observations and the quote illustrate how the key speakers valued and general-

ized specific forms of gendered attitudes, such as emotionality or showing that men can

cry, yet without necessarily addressing overtly the gender issues at stake. They perform

an inversion of gendered stereotypes through the identification with an animal, thereby

conveying the idea as being beyond mere gender issues. Some of these key figures, though

they did not mention it during conferences or workshops, did write about gender comple-

mentarity or about a so-called feminine side of the ecological transition (Egger 2017, p. 45).

By relying on an apprehension of nature as a place of enchantment, or of “wholeness”,

these key figures were adopting a universalizing perspective. Just a few months later, a free

film5 projection was promoted by the same network on a popular cultural beach in Geneva.

The movie documented the story of a social initiative in which adolescents living in suburbs

were encouraged to disconnect from digital media in order to communicate with trees.

Before and after the much-appreciated movie, a discussion took place with wood scientist

Ernst Zürcher who featured in the film. The audience asked numerous questions about

trees, their capacity to produce water and regulate urban heat, their relation to earth and to

humans. The discussion contained a number of organicist metaphors, such as considering

trees as organisms and forests as organs of the earth. The claimed aim of the organizers

of the event was to raise awareness about the value of trees, which took different forms.

While Zürcher explained complex processes performed by trees, such as photosynthesis,

in scientific terms, he often used the word ”cosmic” and followed others in referring to

trees as male or female. When we asked him at the end of the event to elaborate further,

he immediately pointed out that to consider trees male or female was indeed scientifically

inaccurate. He added that speaking of male and female trees was, however, a way to

communicate with people at what he called a ”spiritual level”. Here, it appeared that

communicating at a spiritual level with urban dwellers meant attributing human gendered

features to nature.

Within this network, gender was neutralized, while interdependency in the Anthro-

pocene was universalized. Indeed, through the claims of holism, and by stating that every

living organism was part of a “Whole”, some elements of criticisms were side-stepped in

the public communications. The rhetoric of self was inscribed into a wider view of interde-

pendency between humans and non-humans, thereby marginalizing a critique based on

Religions 2022, 13, 23

9 of 15

gender. In that regard, the use of organic metaphors when relating to nature, as Timothy

Morton argues, neither encourages ecological views nor fosters subversive gender roles

and models. For Timothy Morton, “Organicism is not ecological. In organic form the whole

is greater than the sum of its parts [ . . . ] The teleology implicit in this chiasmus is hostile to

inassimilable difference”, inasmuch as “organicism polices the sprawling, tangled, queer

mesh by naturalizing sexual differences.” (Morton 2010, p. 278) This remark leads us to the

last profile we found in the field, a profile revolving around a perception and conception of

nature as uncanny and challenging toward a dominant, binary, gendered moral order.

5.3. Neo-Shamanism: Queering Natureculture

It is among some neo-shamanic practitioners that we found the idea of a non-organic

and ”queer mesh”; that is, what Morton describes as ”a non-totalizable, open-ended con-

catenation of interrelations that blur and confound boundaries at practically any level:

between species, between the living and the non-living, between organism and envi-

ronment“ (Morton 2010, p. 275). We shall focus on one practitioner in particular who

integrated views on naturecultural patchworks in an explicit way by encouraging not only

the sensing of spirits to connect with but also to discover the animal reflecting one’s self.

In the realm of neo-shamanic practitioners, we met mostly artists who had been initiated

into neo-shamanism many years ago and even trained in Michael Harner’s Foundation

for Shamanic Studies. Those active in the ecological realm adopt sentient dimensions to

frame ecological or nature-related issues. They offer what they call “forest baths”, “vision

quests”, or ”drum circles in the forest” (all expressions we found on leaflets or websites),

for instance, and participate in ecological festivals. The practitioner we concentrate on, an

artist photographer and journalist, was offering “queer yoga” classes in Geneva. In the

long exchange we had with her, she elaborated on the way she thinks of nature and what

“queer” means for her:

We can make a direct link between neo-shamanism and queer. This link is

situated in the relation to magic, in the relation to movement which is not fixed,

not written, not stopped, not defined and in the porosity of the real, the porosity

between the worlds . . . the relation to the spirits. To think that there are entities.

There we enter into spirituality. To think that there is something other than just

me and to think that there are energies of the entities of the gods [and] goddesses,

it does not matter, we will say the word “spirit”, if we imagine that there are the

spirits and the human. Additionally, that we imagine that it’s not separated and

that it’s possible to dialogue and to trade. Additionally, therefore a space where

human and nature are not dissociated, where . . . human is nature. (Fieldwork

interview, Lausanne, April 2019)

We can clearly recognize in this quote how the self is no longer at the center of the

worldview or cosmology; on the contrary, there appears to be a hybrid whole—close

to what Morton would call a mesh. According to Morton’s notion of ”dark ecology”

(Morton 2018), when a deep connection with the earth develops, a sense of solitude appears.

This solitude comes from the fact that humans realize that today, “contemporary capitalism

and consumerism cover the whole Earth and reach deep into the forms of the living”

and that “we actively and passively destroy life-forms inhabiting and constituting the

bio-sphere, in Earth’s sixth mass extinction event” (Morton 2010, p. 273). The neo-shamanic

practitioner we quoted did indeed not favor a harmonious or colorful view of nature. The

photographs she exhibited evoke a sense of mysticism, of cold fairyism with smoothed

contrasts between soil, trees and sky (Figure 1).

Religions 2022, 13, 23

solitude comes from the fact that humans realize that today, “contemporary capitalism

and consumerism cover the whole Earth and reach deep into the forms of the living” and

that “we actively and passively destroy life-forms inhabiting and constituting the bio-

sphere, in Earth’s sixth mass extinction event” (Morton 2010, p. 273). The neo-shamanic

practitioner we quoted did indeed not favor a harmonious or colorful view of nature. The

photographs she exhibited evoke a sense of mysticism, of cold fairyism with smo1o0tohfe1d5

contrasts between soil, trees and sky (Figure 1).

FFiigguurree11.. PPhhoottoo ffrroommhhttttppss::////wwwwww.c.ceeuuxxddicici.ic.chh/j/ejuexu-xd-ed-ela-l-ab-abllael/le(/re(prreipnrtiendtefdrowmitChapreinrme Risostihon from

C(2a0r2in0e).Racocthes(s2e0d20o)na3ccNesosveedmobner3 2N0o2v1)ember 2021).

TTooaaccttuuaalllyy bbee iinnssiiddee aammeesshh aannddttaallkk aabboouutt iittppuuttsshheerrnneecceessssaarriillyy iinn aann iimmppoossssiibbllee

ppoossiittiioonn that is tthheennrreefflleeccteteddininththeecocnovnovloultuetdedlanlagnugaugaegseheshueseuss.eIsn. thIne trhiteuarlistutahlis sthias-

smhamnicanpircapctriaticotinteiornperropproospeos,seshs,esdhoeedsoneostnaovtoaidvopiduzpzuliznzglianngdansodmseowmheawt hwaot rwryoirnrgyienng-

ecnocuonutnertesr. sH. eHrenronno-nc-ocnofnofromrmisitsltolokokinintetremrmssooffccloloththeessaannddggeennddeerreedd aesthetic contriibbuutteedd

ttoo tthhiiss.. TThhrroouugghh hheerr sshhaammaanniicc aass wweellll aass ddaaiillyy pprraaccttiicceess aanndd tthhrroouugghh hheerr ddiissccoouurrssee aabboouutt

““ssppiirriittuuaalliittyy”” aanndd ““qquueeeerr””,, tthhiiss iinnffoorrmmaanntt ccoonnssttaannttllyy ppeerrffoorrmmeedd aa bblluurrrriinngg ooff ccoommmmoonn

ccaatteeggoorriieess.. Wee ccoonncclluuddee tthhaatt sshhee eennaacctteedd nnaattuurreeccuullttuurraall vviieewwss iinn tthhee sseennssee ppiinnppooiinntteedd bbyy

DDoonnnnaa HHaarraawwaayy ((22000033))..

66.. TThhee EEmmeerrggeennccee ooff CCrriittiiccaall SSttaanncceess aatt tthhee HHuubbss ooff EEccoo--SSppiirriittuuaalliittyy

TThheessee tthhrreeee wwaayyss ooff aarrttiiccuullaattiinngg nnoottiioonnss ooff sseellff,, eeccoollooggiiccaall aawwaarreenneessss,, aanndd ggeennddeerr

ccoonnssttiittuuttee aa ccoonnttiinnuuuumm ffrroomm aann eesssseennttiiaalliisstt ppoollee wwiitthh ppoollaarriizziinngg aanndd hhaarrmmoonniioouuss ggeennddeerr

eenneerrggiieess ttoo tthheepprrooggrreessssiviveeddisiasappppeaeraarnanceceofotfhtehgeegnednedreedresdelsfealnf da,nfdin,afillnya,lolyf,thoef cthoreecsoerlef.

sTehlfe.sTehthesreeethproeseitpioonssitlieoanvseleliattvlee slipttalceesfpoarcpeafrotricpipaarntitcsiptoanfrtasmtoefaradmisecuasdsiiosncuosfstihone poof wtheer

pisoswueers iasstusetsakaet srteagkaerrdeignagrdhionwg hgoewndgeerndaenrdanthdetheecoelcoogliocgailcaclricsriissirserlealtaetetotoeeaacchhootthheerr,, aass

CChhrriissttiinnee BBaauuhhaarrddtt ddooeess,, ffoorr iinnssttaannccee ((BBaauuhhaarrddtt 22001133)).. NNeevveerrtthheelleessss,, ggiivveenn tthhee tteerrrriittoorriiaall

pprrooxxiimmiittyy ooff tthheesseeaaccttoorrss,, ssoommeessiittuuaattiioonnss aarriissee wwhheenn ssuucchhaassppaacceeiissccrreeaatteedd.. OOnnee ssuucchh

asstiinitvtuduiasalttotiinoaongnn-dosotcaclconcunudrgrrienr-edsgdtaipnnirnodJumiJnluyoglty2ep0r21ro0o8f1mw8goohwdteehdnreeSnsotsfaSsrgtphaoiarrdwhitdaukewa,sltksiht,yest,p6fhaiewrmifatoausumaisnloivCtuyiats,el6idCfwoafarolnisrfioaairnntnwvfiieaotmne-ddifnaefyimoswtrienoacirsoktt-wsaehccootoi-pvd-aiaiscnyt-

Lwaourskasnhnoep. TinheLeavuesnant wnea.sTohregaenvieznetdwbaysaocrogaalnitiizoendfobrymaedcobaylitaioloncfaolrsmoceido-bcyulatulroaclaalcstoivciitoy-

cceunltteurr,aal aCchtirvisittiyanceNntGerO, ,auCnhivriesrtsiaitny NchGaOpl,auinnsi,vaerpseitdyacghoagpiclafianrsm, appreodmaogtoinggicpfaerrmmapcruolmtuoret-,

ainngd paenramsasocucilatutiroen, aonf dthaendaesgsroocwiatthiomn oovf ethmeednet.gArowhitghhmnouvmebmeernotf. pAerhsiognhsnfurommbethr eofNpeewr-

AsognesafnrdomhotlhisetiNc mewiliAeug,ethaendtrahnosliitsitoicnmneiltiweuo,rkth, eantrdanthseitiqounonteedtwnoeork-s,haanmdatnhiec qpuraoctteidtionneeor-

asthteanmdaendicthpereavcteintito,nmearkainttgenfodreda vthereyehveetnert,ogmeankeionugs faourdaienvceer.yWhoemteerongoefnaelol uags easufdoiremnecde.

wttWhheeeoremmtraaaelnnjsoosroiitpftiyorae,nllsyemaengtotev.vsaIenfrmoiooremuunsretfidmwetaelhdlreeenkmoaetlsaeyosjofiwprgirteueyswr,eeyrnseotott.efvI:ntahroieuoiurnsfnimeelrdaclneiorkcteleesyowffigetuhwreertosrtaoenf: sthiteioinnnmerovciermcleenotf

It is a Friday evening when we attend together with hundreds of interested

people of all ages a public conference on ecofeminism featuring the key speaker

Starhawk. The attending crowd has quickly filled the 200 seats in the space rented

for the occasion near the main railway station, and more chairs need to be found

to seat everybody. During half of the conference, an attentive and silent audience

listens to Starhawk explaining her alternative archeological and mythological

views on a pre-Christian matrifocal society. She argues that ancient Caucasian

societies were “focused on the power of nurturing, of nourishment, of bringing

life into the world of life-itself, and that the sacred [ . . . ] was embodied, imminent,

Religions 2022, 13, 23

11 of 15

in life-itself, in nature itself, in the natural world”. We are seated next to young

women artists from the area who are very excited about meeting Starhawk in

person as well as older scientists known from the university. Starhawk sums up

her life-long posture upon spirituality and gender issues:

“You know, if we only see the divine and the sacred in male form, then it becomes

very hard again as a woman, or as a gender-fluid person, or person who does

not fall into these nice and neat binary categories, to feel that sacred connection

to your own body and to your own life. To feel that you are an inherent carrier

of value and that it also becomes difficult in society again to hold that we must

value all of us. All of our images of who is really sacred and divine again only

reflect one gender or one race or one color or one way of being.”

She then introduced the audience to the alternative agronomy of permaculture, offer-

ing some basic organic farming principles and referencing such science as pedology—the

study of the rhizosphere and the formation of arable soils. The audience raised several

questions and praised the speaker and the organizers.

The particularity of Starhawk with regard to the actors quoted so far is that she

explicitly elaborated on a feminist posture. She articulated a critique of the dominant

patriarchal system with environmentalism and identified as a woman:

[It is] very important as women that we also look at the impact of the environment

on us as women, and on how environmental degradation impacts women around

the world, in ways that I think are even more extreme sometimes than how they

impact men. Because, again, of this unequal structure of power. So if you have

a society or you have a culture where women have less power, and less power

in the home and less money and less resources, and less access to knowledge

and education, you add to that environmental degradation. Then, it is often the

women who go hungry to feed their family. It is the women who end up walking

miles and miles and hours and hours each day to collect wood when the supplies

around the home are used up, or to get water when there is no access to clean

water. Therefore, we have to look at these issues, together. (Lausanne Fieldwork

notes July 2018)

The theme of care and the conception of nature as a place of re-enchantment are clearly

central to Starhawk, and mythological, ethical, spiritual, and scientific framings are easily

entangled in her discourse. Although Starhawk emphasized idealized feminine values, a

prehistoric matrifocal past or even the counter-cultural figure of the witch, she explicitly

mentioned that she addressed women as much as “gender-fluid persons” or “persons who

do not fall into these nice and neat binary categories”, a statement loudly applauded in the

room. The attendance of Starhawk, but also the popularity of this event, shed light upon

the growing—in size, in visibility and in cross-references—number of feminist critics within

eco-spiritual activism. In our case, Starhawk’s conference brought some gender trouble into

the local eco-spiritual milieu that was largely composed, as indicated, of a variety of actors

promoting different views and practices with regard to ecology, gender, and spirituality.

Starhawk’s counter-cultural voice professed subversive considerations regarding gender

identities as well as the nature/culture dichotomy. Starhawk indeed operates a subversion

of gender attributes while still using gendered rhetoric, yet in a self-reflexive manner. Her

speech entailed a common call to global ecofeminist and queer ecologists to have their

voices heard and to value multiple codes in expressing gender and sexual orientation,

especially when mediating critics related to the depletion of local biotopes.

Starting with Starhawk’s conference, we observed that the articulation of the links

between spirituality, ecology, and gender was becoming more and more popular. This

articulation served communicative purposes within different social movements seemingly

distant from the eco-spiritual network we studied. For instance, in June 2019, a historical

mobilization of “women*”7 took place all over the country. In the city of Lausanne, the

women*’s strike started in an unsuspected manner: at midnight a walk was organized

Religions 2022, 13, 23

der and sexual orientation, especially when mediating critics related to the depletion of

local biotopes.

Starting with Starhawk’s conference, we observed that the articulation of the links

between spirituality, ecology, and gender was becoming more and more popular. This

articulation served communicative purposes within different social movements seem-

ingly distant from the eco-spiritual network we studied. For instance, in June 2019,12aohf i1s5-

torical mobilization of “women*”7 took place all over the country. In the city of Lausanne,

the women*’s strike started in an unsuspected manner: at midnight a walk was organized

rreessoonnaattiinngg wwiitthh aa wwiittcchheess’’ ““WWaallppuurrggiiss””nniigghhtt.. IItt ggaatthheerreedd hhuunnddrreeddss ooff wwoommeenn** aarroouunndd aa

bboonnfifirreewwhheerreetthheeyyrriittuuaalllyybbuurrnneeddbbrraass..IInn 22002200,, tthhee eevveenntt wwaass rreeppeeaatteedd,, bbuutt tthhee ddiiffffeerreenntt

eevveennttss were ssccaatttteerreeddaaccrroossssesveverearlapl lpalcaecseds udeuteo tCoOCVOIDV-I1D9-1re9strreiscttriiocntiso. nAs.feAw dfeawysdaaftyesr

athfterstrhiekes,triinketh, ienbtahcekbsatcrkeesttroefeat ogfeantgreifnietrdifineedignhebigohrhboorhdooofdLoafuLsaunsnaen, noen,eosniegnsibgonabrodared-

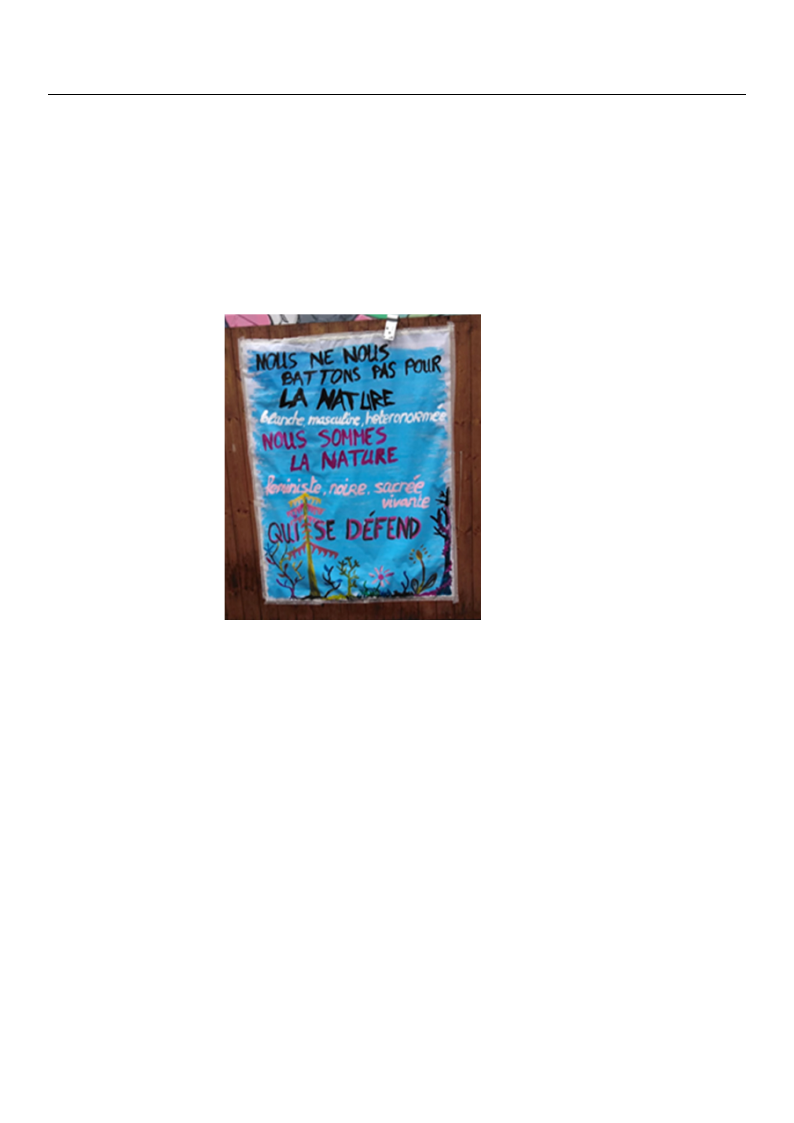

rmemaianiendedfofroreveevreyryoonneetotoseseeoonnththeewwaallslsooffaannaauuttoonnoommoouuss ssoocio-cultural center.. IItt ssttaatteedd

((iinnFFrerennchch) )thtahta“tW“eWaereanroetnfiogthftignhgtfionrgafworhiatew, mhiatsec,umlinaesc, uanlidneh,eatenrdonhoertmeraotnivoernmaatutirvee/wnae-

aturerea/wfeemairneisat,febmlaicnki,sts,abclraecdk,,lsivacinregdn, alitvuirnegdneafteunrdeindgefeitnsdelifn”g. iTtsheelfi”c.oTnhoegricaopnhoygirsapsohbyeirs,

fseoabtuerr,infegaatupriinnge tarepei,nwe eteredes,, wanededesv,eannda deevaedn taredee,aadll torfeeit, eanllcoofmipt aesnsceodmbpyasthseedgebnyetrhice

cgaetnegeroircycoaftengaoturyreo(fFnigauturere2()F. iTghuerree2is).aT“hdearerkisecao“lodgayrk” epcroesloegnyt ”inptrheissesnitgninbothairsdsaigsnnbaotuarred

iassanlsaoturereprisesaelnsoterdepbryeistesnmteidsfibtys aitnsdmuisnfaitesstahnedticunwaieldsthweeteicdws. ild weeds.

FFiigguurree22.. PPhhoottoo bbyy AAlleexxaannddrreeGGrraannddjjeeaann,,LLaauussaannnnee,,1166JJuunnee22002200..

TThheeppoosstteerriinn Lauussaannnnee clearllyy contrasttss a “masculine” ethos with a wider “feminist”

eetthhooss,, tthheerreebbyyeennccoouurraaggiinnggwwoommeennttooggoo bbeeyyoonnddaa vviieeww ooff ggeennddeerr eeqquuaalliittyy aanndd ttoo eennggaaggee

iinniinntteerrsseecctitoionnaal lmmililtiatnancyc.yB. yByquqauliaflyiifnyginNg aNtuarteuares saascrseadcr,ethdi,stphoisstpeor satlesro ahlisnotshaint tsheatidtehae

tihdaeta“tgheantd“egreenddreirteudalrcitounatlactonwtiatcht twheithotthheerwotohreldrwdoorelsdidnoseosmine csiormcuemcsirtacunmcesstaenmcpesowemer-

wpowmern”w(oGmreeenn”w(Goordee2n0w00o,opd. 2104080)., Fpu. 1rt4h8e)r.mFuorteh, ethrmeroeries,nthoteroenilsynaovtioenwlyofagveinewdeor fpgoelanrditeyr

bpuotlaarlistoycbleuatralylsoancliedaeralyl oafnthideefaelmofintihneefbemeininginmeobreinpgowmeorrfue lptohwanertfhuel mthasncuthlienme.aSsucuchlinane.

eScuocfhemanineisctovfeimewindisotevsiecwondtaoiensacfoonrtmainofatfhoermnewof “thsuebntelewsp“siruibtutlaelistpyi”ritthuaatliitsyl”otchaalltyisstlioll-

sceaelklyinsgtiiltlssseoeckiianl,gcuitlstusroacli,apl,ocliutilctualraaln, dpodliistcicuarlsiavnedlodciastciounrs(iBveeclcoiceattaiol.n20(B2e1c).ciInetterael.st2in02g1ly),.

tIhnetedreifsfteirnegnlty,vtiheewdsitfhfeartesnetevkietwo sret-heantcsheaenkttoNraet-uernec,hbaunttaNlsaotuprreo,vbiudteaalscorpitriocavlidsteaancceri,taicrael

asltsaonacew, aaryeoaflrseo-eancwhaayntoinfgreth-eenmchilaintatnintgsetlhf eanmdilsittraenntgsthelefnainngdtshterepnoglitthiceanlinabgiltihtye opfosloitciciaall

maboivlietymoenf tssotcoiaelnmgaogveemineinnttsertsoecetniognaaglesitnruigngtelerssewcthioenrealclsitmruagtegilmespwerhilemreenclti,msoactiealimjupsteirciel-,

amnedngt,esnodceiarlejuqsutaicliet,ieasndgogehnadnedr-ienq-uhaalnitdie. sTghoishsamnda-lline-xhaamndp.leThailssosmillaullsterxaatmesppleosaslisboiliiltliuess-

ttoragtoesbpeoysosnibdiltihtieesestsoengtoiabliesytoonrdqutheeeresesnednetaiavloisrtwore qhuaeveerpernedseenavteodr iwnethhiasvaertpicrleesienntoerddeinr

to form new militant coalitions. It is, however, too soon to draw conclusions on the social

dynamics and impacts of such intersectional views on nature.

7. Conclusions: Gender, Nature, Religion, and the Anthropocene

Our findings point to a variety of ways by which a nature referred to as “sacred” is

gendered, ending either in essentialist views or in queer perspectives. In this article, we

have considered the notion of nature as a surface on which to project views and represen-

tations about one’s self, others, and the environment. Yet, as we have carefully shown,

if it is possible to delineate three distinct postures relating to holistic spiritualities, inner

transition and neo-shamanism, we have also shown how these different postures tend not

Religions 2022, 13, 23

13 of 15

to be isolated. On the contrary, as shown by the ethnographic vignette of Starhawk’s confer-

ence presentation in Lausanne in 2018, these eco-activists frequently encounter each other

during public events. Eventually, with regard to what we have termed a “spiritualization”

of ecology (Becci and Grandjean 2021), these key figures are important as they promote

practices and worldviews in which the self, gender and nature entangle in various ways.

Yet, in the public domain, these eco-spiritual registers tend to be popularized; that is, they

are adapted to the communication codes of secular culture and even contemporary political

movements, such as feminism.

In summary, beyond the great variety of forms of spirituality that appear on the

ground at first sight, with disparate references and the incessant assertions of actors

aiming to differentiate themselves from each other, an anthropological perspective allows

us to distinguish a series of analogies that construct a new vision of the social order.

In the observations we made, thinking in analogies constitutes a holistic thinking that

tends toward universalization and a neutralization of cultural differences. The recurring

principles are the holistic beliefs in harmony and the values of gratitude, non-violence,

fluidity, and economic sobriety. Through our empirical observations and analysis of the eco-

spiritual milieu in Switzerland, we found that the change in representations of nature, and

the introduction of new religious expressions also redraw gender norms and stereotypes.

We have shown that universalistic and planetary imaginaries such as the “Web of Life” can

be contextualized and related to individuals’ gendered selves. Such a contextualization is

necessary to consider the so-called “Anthropocene” in sociological terms and identify, as

Donna Haraway (2003) suggests, the location of social, political, and economic capital in

ecological action.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, I.B. and A.G.; funding acquisition, I.B.; investigation, I.B.

and A.G.; methodology, I.B. and A.G.; project administration, I.B.; supervision, I.B.; writing—original

draft, I.B. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, I.B. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to

the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: Swiss National Science Foundation. Project 169823.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as

no sensitive data were used and the observed events were public.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the editors of this issue for their insightful comments, advice,

and critiques of previous versions of the text.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

1 These notions often have an ambivalent status as they are used by scientists as well as by practitioners of contemporary spirituality

(see for instance Narby (1995), p. 68 or Zürcher (2016), p. 41, for “cosmic” (serpent, tree), and Glowczewksi and Pruvost (2021) for

the notion of “healing energies”).

2 For instance, https://painpourleprochain.ch/transition.interieure/ (accessed on 21 November 2021).

3 For further insights into these analytical research categories the reader may refer to the different contributions made in the edited

book Secular Societies, Spiritual Selves? by Fedele and Knibbe (2020).

4 The book which contributed enormously to the introduction of international ecofeminist texts to a Francophone context was

Emilie Hache’s collection Reclaim (Hache 2016), published in 2016.

5 The movie shown was entitled “Connectés” (Schinasi 2018). For more information on that day, see https://aux-arbres.com/les-

solutions/ (accessed on 21 November 2021).

6 See Salomonsen (2002) for a close description of this network. Starhawk’s political writing on eco-activism had recently been

translated into French (Starhawk 2015), though her writing on religious and gender creativity, such as the bestseller The Spiral

Dance (Starhawk 1979), still remains unavailable in French.

7 For this event celebrating a historical women’s strike in 1991, numerous debates occurred around the presence of an official

asterisk to mark inclusion of transgender and non-binary persons.

Religions 2022, 13, 23

14 of 15

References

Bauhardt, Christine. 2013. Rethinking gender and nature from a material(ist) perspective: Feminist economics, queer ecologies and

resource politics. European Journal of Women’s Studies 20: 361–75. [CrossRef]

Bauman, Whitney A. 2015. Climate Weirding and Queering Nature: Getting Beyond the Anthropocene. Religions 6: 742–54. [CrossRef]

Becci, Irene, and Alexandre Grandjean. 2018. Tracing the Absence of a Feminist Agenda in Gendered Spiritual Ecology: Ethnographies

in French-speaking Switzerland. Anthropologia 5: 23–38.

Becci, Irene, and Alexandre Grandjean. 2021. Toward a ‘spiritualization’ of ecology? Sociological perspectives from francophone

contexts. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 15: 287–96.

Becci, Irene, Christophe Monnot, and Boris Wernli. 2021. Sensing ‘Subtle Spirituality’ among Environmentalists: A Swiss Study. Journal

for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 15: 344–67.

Becci, Irene, Manéli Farahmand, and Alexandre Grandjean. 2020. The (B)earth of a Gendered Eco-Spirituality: Globally Connected

Ethnographies Between Mexico and the European Alps. In Secular Socieities, Spiritual Selves?: The Gendered Triangle of Religion,

Secularity and Spirituality. Edited by Anna Fedele and Kim E. Knibbe. London and New York: Routledge.

Becci, Irene, and Salomé Okoekpen. 2021. Staging Green Spirituality in the Parks of Lausanne and Geneva: A Spatial Approach to

Urban Ecological Festivals. In Urban Religious Events: Public Spirituality in Contested Spaces. Edited by Paul Bramadat, Mar Griera,

Marian Burchardt and Julia Martinez-Ariño. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

Beckford, James A. 2003. Social Theory & Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Browne, Kath, Sally R. Munt, and Andrew Kam-Tuck Yip. 2010. Queer Spiritual Spaces: Sexuality and Sacred Places. Oxfordshire:

Routledge.

Carine Roth. 2020. Jeux de la Balle. Available online: https://www.ceuxdici.ch/jeux-de-la-balle/ (accessed on 3 November 2021).

Castree, Noel, and Bruce Braun, eds. 2001. Social Nature: Theory, Practice, and Politics. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Champion, Françoise. 1995. Religions, approches de la nature et écologies. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 90: 39–56. [CrossRef]

Chautems, Joëlle, and Mathieu Bressoud. 2013. Guide des lieux enchantés de Suisse romande: 30 balades à la rencontre des esprits de la nature.

Lausanne: Favre.

Choné, Aurélie. 2016. Ecospiritualité. In Guide des Humanités environnementales. Edited by Aurélie Choné, Isabelle Hajek and Philippe

Hamman. Villeneuve d’Ascqu: Presses universitaires du Septentrion, pp. 59–71.

De Lauretis, Teresa. 1991. Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities. Differences, a Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 3: iii–xviii.

Descola, Philippe. 2005. Par-delà nature et culture. Paris: Gallimard.

Di Marco, Steeve. 2017. Dialogue avec les esprits de la nature: Leur habitats, leurs actions, leurs enseignements et leurs révélations. Paris:

Temps présent.

Di Marco, Steeve, and Gorka Cruz. 2018. Les esprits de la nature dans les parcs de Suisse romande: Guide d’éveil au ressenti. Bière: Cabédita.

Egger, Michel Maxime. 2017. Ecopsychologie: Retrouver notre lien ave la Terre. Genève: Editions Jouvence.

Fedele, Anna, and Kim E. Knibbe, eds. 2020. Secular Societies, Spiritual Selves?: The Gendered Triangle of Religion, Secularity and Spirituality.

New York and London: Routledge.

Glowczewksi, Barbara, and Geneviève Pruvost, eds. 2021. Des énergies qui soignent ne Montagne limousine. Enquête collective. Lamazière-

Basse: Maiade.

Grasseli Meier, Marianne. 2018. Le réveil des gardiennes de la terre: Guide pratique d’écothérapie. Paris: Courrier du Livre.

Greenwood, Susann. 2000. Gender and Power in Magical Practices. In Beyond New Age: Exploring Alternative Spirituality. Edited by

Steven J. Sutcliffe and Marion Bowman. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 137–54.

Griera, Mar, and Anna Clot-Garrel. 2015. Banal is not Trivial: Visibility, Recognition, and Inequalities between Religious Groups in

Prison. Journal of Contemporary Religion 30: 23–37. [CrossRef]

Hache, Emilie, ed. 2016. Reclaim: Recueil de textes écoféministes. Paris: Cambourakis.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 2002. New Age Religion. In Religion in the Modern World. Edited by Linda Woodhead, Paul Fletcher, Hiroko

Kawanami and David Smith. London and New York: Routledge.

Haraway, Donna. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: The University of

Chicago Press.

Hedges, Elli, and James A. Beckford. 2000. Holism, Healing and the New Age. In Beyond New Age: Exploring Alternative Spirituality.

Edited by Steven J. Sutcliffe and Marion Bowman. Edimburgh: Edimburgh University Press.

Heelas, Paul. 1996. The New Age Movement: The Celebration of the Self and the Sacralization of Modernity. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London and New York: Routledge.

Knoblauch, Hubert. 2008. Spirituality and Popular Religion in Europe. Social Compass 55: 140–53. [CrossRef]

Knoblauch, Hubert. 2014. Popular Spirituality. In Present-Day Spiritualities: Contrasts and Overlaps. Edited by Elisabeth Hense, Frans

Jespers and Peter Nissen. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 81–102.

Lepage, Martin. 2018. Religiosités queer néo-païennes et la question de l’authenticité dans la Wicca. Religiologiques 36: 195–221.

Available online: https://www.religiologiques.uqam.ca/no36/36_195-221_Lepage.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2021).

Macy, Joanna, and Molly Young Brown. 2014. Coming Back to Life. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

Monnot, Christophe, and Alexandre Grandjean. 2021. Advocating in Ecology Through Meditation: A Case Study on the Swiss

‘Inner Transition’ Network. In Religion, Law and the Politics of Ethical Diversity. Edited by Claude Proeschel, David Koussens and

Francesco Piraino. London and New York: Routledge.

Religions 2022, 13, 23

15 of 15

Morton, Timothy. 2010. Guest Column: Queer Ecology. PMLA 125: 273–82. [CrossRef]

Morton, Timothy. 2012. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Morton, Timothy. 2018. Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence, Wellek Library Lectures in Critical Theory. New York City: Columbia

University Press.

Narby, Jeremy. 1995. Le serpent cosmique l’ADN et les origines du savoir. Geneva: Georg Editeur.

Pike, Sarah M. 2001. Earthly Bodies, Magical Selves: Contemporary Pagans and the Search for Community. Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Rountree, Kathryn. 1999. The politics of the Goddess: Feminist Spirituality and the Essentialism Debate. Social Analysis: The International

Journal of Anthropology 43: 138–65.

Salomonsen, Jone. 2002. Enchanted Feminism: Ritual, Gender and Divinity among the Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco. London:

Routledge.

Schinasi, Jane. 2018. Connectés. France. Available online: https://www.cinelux.ch/2019/03/11/programmation-du-13-au-19-mars-

2019/ (accessed on 6 November 2021).

Schütz, Alfred, Thomas Luckmann, and Richard M Zaner. 1974. The Structures of the Life-World. London: Heinemann.

Schwaiger, Lisa, Daniel Vogler, Silke Fürst, Sabrina Heike Kessler, Edda Humprecht, Corinne Schweizer, and Maude Rivière. 2021.

Darstellung von Frauen in der Berichterstattung Schweizer Medien. In Jahrbuch Qualität der Medien. Zurich: Forschungszentrum

Öffentlichkeit und Gesellschaft (fög).

Sointu, Eeva, and Linda Woodhead. 2008. Spirituality, Gender, and Expressive Selfhood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47:

259–76. [CrossRef]

Starhawk. 1979. The spiral dance. New York: Harper & Row.

Starhawk. 2015. Rêver l’obscur: Femmes, magie et politique. Paris: Cambourakis.

Stolz, Jörg, Judith Könemann, Mallory Schneuwly Purdie, Thomas Englberger, and Michael Krüggeler. 2016. (Un)Believing in Modern

Society: Religion, Spirituality, and Religious-Secular Competition. New York and London: Routledge.

Strathern, Marilyn. 2016. Before and After Gender: Sexual Mythologies of Everyday Life. Chicago: Hau Books.

Sutcliffe, Steven J. 2000. ‘Wandering Stars’: Seekers and Gurus in the Modern World. In Beyond New Age: Exploring Alternative

Spirituality. Edited by Steven J. Sutcliffe and Marion Bowman. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Tola, Miriam. 2018. Between Pachamama and Mother Earth: Gender, Political Ontology and the Rights of Nature in Contemporary

Bolivia. Feminist Review 118: 25–40. [CrossRef]

Woodhead, Linda. 2012. Gender Differences in Religious Practice and Significance. Travail, Genre et Sociétés 27: 33–54. [CrossRef]

Zürcher, Ernst. 2016. Les Arbres, entre visible et invisible. Arles: Actes Sud.