A GESTALT ORIENTED PHENOMENOLOGICAL AND PARTICIPATORY STUDY

OF THE TRANSFORMATIVE PROCESS OF ADOLESCENT PARTICIPANTS

FOLLOWING WILDERNESS CENTERED RITES OF PASSAGE

ADAM H. ROTH

Bachelor of Arts in Art

Cleveland State University

June, 1996

Master of Arts in Psychology

Cleveland State University

May, 2001

submitted in partial fulfillment of requirement for the degree

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN URBAN EDUCATION

at the

CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY

MAY, 2010

©Copyright by Adam H. Roth, 2010

This dissertation has been approved for

the Office of Doctoral Studies,

College of Education

and the College of Graduate Studies by

________________________________________________________________

Sarah Toman, Chairperson

02/04/2010

Counseling, Administration, Supervision, and Adult Learning

________________________________________________________________

James C. Carl, Methodologist

02/04/2010

Curriculum and Foundations

________________________________________________________________

Ann Bauer, Member

02/04/2010

Counseling, Administration, Supervision, and Adult Learning

________________________________________________________________

Kathryn MacCluskie, Member

02/04/2010

Counseling, Administration, Supervision, and Adult Learning

_______________________________________________________________

Lynn Williams, Member

02/04/2010

Bellefaire JCB

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND GRATITUDE

Transformation: I let you see me and began to see more of myself. Being different and

being seen while standing with and belonging. I am standing in my heart; from this I am

not moved. I went out to the edge and you held me, so I did not look away. I have

experienced myself. I have experienced relationships. I experience gratitude.

(Adam Roth, 2005, www.natural-passages.com)

My deepest gratitude and appreciation to my Lady Bear for all the love you‟ve

given me. To my parents, for growing me from a seed and providing fertile soil so I may

thrive in life. To Jackie and Herb Stevenson for all the guidance, support, sanctuary, and

community. To Herb, the Natural Passages Program, and all the Men of Medicine for

standing with me and holding me up as I walk this path. To Ken Chapin for our

friendship and the dissertation research assistance. To the research participants. To the

Gestalt Institute of Cleveland for the training. To Sarah Toman, my dissertation chair and

doctoral program advisor, you are awesome. Mother Earth, Father Sky, Great Spirit

Mystery. I hold to my heart. The learning and experience that has led me to write this

dissertation, to actualize my soul work. I am a very fortunate man.

A GESTALT ORIENTED PHENOMENOLOGICAL AND PARTICIPATORY STUDY

OF THE TRANSFORMATIVE PROCESS OF ADOLESCENT PARTICIPANTS

FOLLOWING WILDERNESS CENTERED RITES OF PASSAGE

ADAM H. ROTH

ABSTRACT

This dissertation, addresses intervention and phenomenological and participatory

research methodology, through a lens of Gestalt Therapy Theory. The intervention, a

wilderness-centered rites of passage, included experiential components of: (1) emersion

in nature, (2) nature-based activities and challenges, (3) alone time in wilderness, (4)

exposure to nature-based archetypes, elementals, and folklore, and (5) participation in

community that supports connection through in ritual, ceremony, dialogue, and reflection.

The participants included three early adolescent males and one adult male, a parent-

participant. Data collection methods included participant observation, journal entries,

photo documentation, photo elicited interviews, processing groups, and field notes. A

multiple case narrative format, each focusing on a program activity component, was

utilized to present data and findings representing the transformative process of the

participants.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………….. v

CHAPTER

I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………….

1

Reflexive Statement………………………………………………..

2

Terms, Constructs, Context and Theoretical Background…………

3

Rites of Passage……………………………………………

4

Wilderness Therapy………………………………………..

6

Ecopsychology……………………………………..

8

Adventure Based Counseling……………………… 10

Gestalt Theory and the Change Process………………….. 12

Holism……………………………………………... 12

Field Theory……………………………………….. 13

Phenomenology……………………………………. 13

Awareness and Figure/Ground……………………. 15

The Gestalt Cycle of Experience…………………... 16

Paradoxical Theory of Change……………………. 18

Gestalt, Adolescent Development, and Wilderness Centered Rites of

Passage…………………………………………………….. 19

Disembedding……………………………………… 21

Interiority………………………………………….. 22

vi

Integration…………………………………………. 23

A Gestalt Methodological Research Approach……………………. 24

Research Questions………………………………………………... 25

Predicted Limitations of the Research…………………………….. 26

Potential Significance of the Study………………………………… 27

Summary…………………………………………………………… 28

II. REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE AND RESEARCH………. 29

Rites of Passage……………………………………………………. 29

Wilderness Therapy………………………………………………... 31

Research Literature Aligned With This Study……………………... 35

Gestalt Relationship to Theoretical Foundation and Methodology… 38

Rites of Passage…………………………………………….. 38

Wilderness Therapy………………………………………… 39

Methodology………………………………………………… 41

Researcher as Instrument…………………………... 41

Participatory/Collaborative Research……………… 42

Foundations of Gestalt Therapy Theory in

Phenomenological Theory……………………. 43

Summary…………………………………………………………….. 45

III. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY………………………………………... 47

Theoretical Framework……………………………………………… 49

Intentionality………………………………………………… 50

Noema and Noesis…………………………………………... 51

vii

Intersubjectivity……………………………………………… 51

Epoche………………………………………………………... 52

Phenomenological Reduction………………………………… 52

Imaginative Variation………………………………………… 53

Research Questions…………………………………………………… 54

Quality, Trustworthiness, and Credibility of Qualitative Research…... 55

Research Methods…………………………………………………….. 57

Participatory Research……………………………………….. 57

Case Narratives………………………………………………. 59

Participant Selection………………………………………….. 61

Participants…………………………………………………… 62

Protection of the Rights of Participants………………………. 62

Data Collection……………………………………………….. 63

Participant Observation……………………………… 63

Journal Entries……………………………………….. 66

Photo Documentation and Photo Elicited Interview… 68

Processing Group……………………………………. 70

Data Analysis………………………………………………… 72

Conclusion……………………………………………………………. 75

IV. DESCRIPTIVE NARRATIVE and DATA ANALYSES……………….. 76

Applied Methods……………………………………………………... 77

Prior Beliefs, Contexts, and Experiences…………………………….. 79

Case Narratives of the Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage Program 88

viii

Group Program………………………………………………. 89

Orientation……………………………………………. 90

Drumming Circle……………………………………... 91

Hike and Snowball Fight……………………………... 96

Horse Facilitated Challenge…………………………. 103

Hay Bale Fort………………………………………… 114

Hike to the River……………………………………… 122

Medicine Pouch and Closing…………………………. 128

Individual Program…………………………………………... 134

The River……………………………………………... 136

Solo in the Cave……………………………………… 141

Tree…………………………………………………... 144

Summary……………………………………………………………... 150

V. SUMMARY, IINTERPRETATIONS, and SUBSTANTIVE ISSUES....... 152

Purpose and Intentions……………………………………………….. 152

Review of Methods and Methodology……………………………….. 154

Quality and Limitations of Qualitative Research…………………….. 155

Revisiting the Research Questions…………………………………… 158

Prior Beliefs, Contexts, and Experiences…………………….. 158

Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage……………………….. 162

Group Program………………………………………. 164

Drumming…………………………………….. 164

Hike and Snowball Fight……………………... 165

ix

Horse Facilitated Challenge…………………. 167

Hay Bale Fort………………………………… 169

Hike to the River……………………………… 171

Medicine Pouch………………………………. 173

Individual Program…………………………………... 174

River………………………………………….. 175

Hike…………………………………………... 177

Solo in the Cave……………………………… 178

Tree…………………………………………... 180

Further Research and Applications…………………………………... 182

The Research Process………………………………………... 182

Further Research of the Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage

Model ……………………………………………….. 184

Contributions to Gestalt Therapy Theory…………………… 185

Progressive Contributions, Furthering Research and Practice 187

Final Thoughts, Reflections, and Conclusions………………………. 188

Reflexive Statement………………………………………….. 188

REFERENCES………………………………………………………………. 191

APPENDICES………………………………………………………………. 202

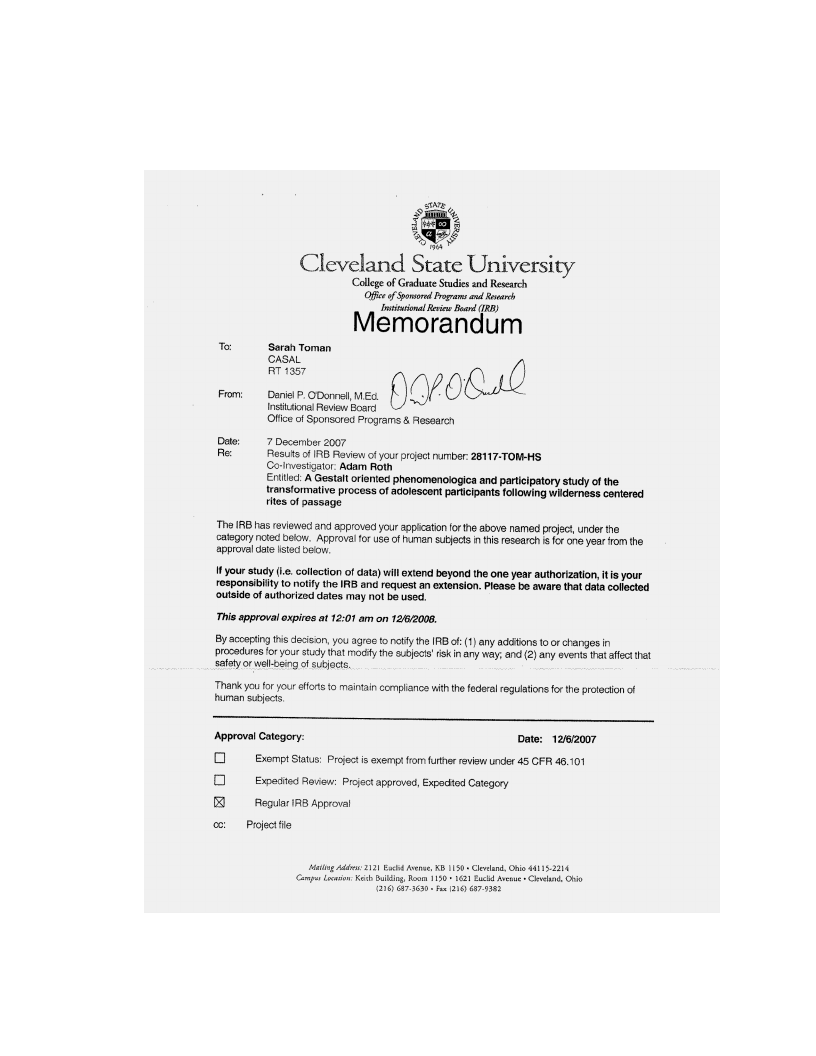

A. IRB Approval Letter……………………………………….... 203

B. Parental Consent Form.……………………………………... 204

C. Assent to Participate in Research………………………….... 206

x

D. Tree Bear‟s Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage Permission

Slip ………………………………………………….. 208

E. Waiver of Liability for the Tree Bear Institute and Its Facilitator

Associates…………………………………………… 210

xi

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Today‟s adolescents lack experience with healthy rites of passage to support their

development and life transitions. For many, the inner strength achieved in the reflective

process of soul searching, the positive self-concept that is empowered from challenging

one self in new experiences, and the relational support received from heart-felt

discussions have given way to drinking, driving, sex and other risky behaviors as

marking the passage to adulthood.

The loss of ritual rites of passage contributes to the societal ills we have

come to know either personally, professionally, or through the media. The

need youth have for some kind of initiation is so strong that it will happen

with or without a healthy blueprint. Throughout history, the less

complicated societies have provided blueprints for children to obtain adult

status and to contribute to their communities.

(www.soulawakening.org)

The intention of this study was to gain further understanding of healthy blueprints and to

further inform psychological practice of the medium of wilderness centered rite of

passage in supporting and facilitating the transformative and developmental process of

adolescence. I begin with one of my own experiences of the outdoors.

1

Reflexive Statement

In the years of my early twenties, I used to visit an elder tree. This tree was one of

four in front of the elementary school close to my home. I would visit every few days. I

would walk around, sit or stand with my back up against or stand facing the tree, or lie at

the base looking up into this tree. Often I would hug this tree. Sometimes I would bring

this tree a gift of tobacco, corn meal, or sage. The presence of this tree evoked within me

a voice that taught me of myself and the natural world of which I am part. The voice

would reveal to me awareness at the depths of my being in the physical, emotional,

mental, spiritual, creative and relational fields. I consider this tree to be one of the great

teachers of my life.

I experienced healing, transformation, development, creativity, generativity, and

relationship with this tree. After having moved to a new home, a distance away from the

tree, my visits became infrequent. Recently, I was strongly drawn to visit this tree again;

a lot of time had passed since my last visit. When I finally did return to the tree, I came

upon a scene to which I had a deeply visceral reaction. His branches were gone, a large

portion of his trunk lay on the ground, about ten feet of trunk remained attached to the

tree‟s base and roots, and there was sawdust everywhere. I gasped; that preceded a primal

scream from which I collapsed into weeping. I honor the passing from this world of a

being with great presence, a being that has and will continue, through the rippling

resonance of that presence, to influence generations.

I chose to include this personal narrative with the intention of orienting the reader

to this dissertation, to my perspective as a researcher and my relationship to what is being

studied. The fields of Wilderness Therapy and Rites of Passage in both theory and

2

practice are something in which I have immersed myself over the last 15 years. This

immersion has significantly supported my personal growth. It has significantly influenced

my academic and career development. As a researcher of this field of study, I hold an

emic perspective. My significant personal and professional experiences and trainings in

the field have helped me to create, design, and facilitate the wilderness centered rites of

passage. This experience has shaped both the way this research was organized and

written, as well as influenced the way I collected, viewed, and interpreted the data. My

involvement in both Wilderness Therapy and Rites of Passage experiences also informed

my desire to combine the two fields into one term; wilderness centered rites of passage,

for the purposes of this dissertation.

Terms, Constructs, Context and Theoretical Background

The theoretical foundation of the intervention, wilderness centered rites of

passage, that mediates the subject of this study came from components of Wilderness

Therapy Theory and Rites of Passage Theory. Both the intervention and the research

methodology of this study are addressed in the context of Gestalt therapy theory. This

dissertation research focused on participants‟ experiences of the change process from the

lens of their therapeutic wilderness experiences. This research takes its definition of the

change process from Gestalt therapy theory, most notably the concepts of awareness and

meaning, as facilitated by experience. The Gestalt theoretical framework also guided the

choice of research methodology in this study. First, Rites of Passage and Wilderness

Therapy are described, followed by a description of the study‟s theoretical Gestalt

3

framework. Chapter One concludes with a declaration of the research questions, the

limitations, and the potential significance of this research.

Rites of Passage

A Rite of Passage both signifies and facilitates transformation in one‟s life. Rites

of Passage, as ceremony, ritual, and practice, are often bound within specific cultural

bases. Traditionally, Rites of Passage are present in all stages of life (Wall and Ferguson,

1998). The concept first emerged as a topic in western academic literature with the 1909

book by Albert van Gennep, titled Rites of Passage. The following section introduces

several models of Rites of Passage experiences that have guided this study.

Van Gennep (1909, 1960) studied the South Italian Carboneria and the Kwakiutl

Hamatsa Society initiations. The study described a series of passages from one stage of

life to another, all involving a ceremonial or ritual structure representative of a transition

of status within the society/community. Van Gennep (1960) asserted a three stage rites of

passage model:

Separation - from the familiar (from previous status)

Transition - from old state to new state (a marginal or liminal period)

Reintegration - into one‟s original social structure (reincorporation of those

passing into new statuses) (p. vii)

(www.wilderdom.com)

Maddern (1990) studied Rites of Passage of adolescents within the Australian

Aboriginal culture and asserted a 5 stage rites of passage model:

Symbolic Journey - Initiation, in this model, involves a journey which takes place

on both real and symbolic levels. The meaning and power of the journey can be

4

intensified by placing it within the context of a ritual. Symbolic acts can be used

to signify the departure from home, the various stages of the journey and the final

return of the successful initiate.

The Challenge - This stage includes real challenges which have to be faced, and

which may result in feelings of confusion, moments of intense fear, experiences

of real pain and occasions when pressing needs cannot be satisfied. This stage

includes times, therefore, of coming to terms with difficult emotions, of

developing the ability to cope with hardship. The love and guidance of older

people are key ingredients in helping the initiates pull through.

Opening the Door to the Dreaming - Initiations are times when doors are opened

to Adult Knowledge – the various words used to describe the complex, many-

layered systems of human society.

Responsibility - With the Adult Knowledge, and after transcending the emotional

and physical tests of initiation, comes public recognition of new responsibilities.

Community Participation - The final stage of initiation is returning to the

community with one‟s new status. This is a transformation which, though

regretted and grieved for at first, is now respected and celebrated.

(www.wilderdom.com)

Dunham, Kidwell, and Wilson (1986) presented an interdisciplinary paradigm

with which to conceptualize Rites of Passage in adolescent development. Their paradigm

includes constructs from cultural anthropology, developmental theory, psychology,

sociology, and theology. Their model presents a 14 step ritual Rites of Passage process.

5

The conceptual steps within their Rite of Passage process model covers the: (1) old

support group, (2) old identity, (3) old identity completion, (4) new environmental

demands, (5) liminality of the individual in transition, (6) activation of adaptive capacity,

(7) agony of developmental passage, (8) awe with respect to fate, (9) accommodation of

new role, (10) ecstasy of neurophysiological deactivation following accommodation, (11)

transcendence upon entry into the new identity, (12) new identity, (13) new support

group, and (14) reinforcement of the new identity.

From my experiences with adolescents, the above models provide developmental

explanations of change within culture while Wilderness Therapy provides the

opportunities. Wilderness therapy offers another model or structure which functions as a

rite of passage. One potentially initiates such ritual by crossing an environmental

threshold into the unfamiliar by immersing one‟s self in nature or facing challenge by

pushing forward through rough wilderness terrain. One‟s safe return to a supportive

community after a time of wilderness solo, or the sharing of the story and experience with

fellow seekers around a campfire, is supporting the integration and transition process of

the rite of passage experience.

Wilderness Therapy

Wilderness therapy has been defined as a therapeutic experience that takes place

in a wilderness setting where the focus is placed on naturally occurring challenges and

consequences (www.wilderdom.com). Wilderness therapy is designed to be a positive

growth experience where participants are immersed in naturally occurring circumstances,

face challenges, and experience structured risk that lead to self-examination, learning of

communication and cooperation, contribution to group well-being, and opportunity and

6

encouragement to succeed (www.wilderness-therapy.org). Wilderness therapy practices

also recognize the restorative and healing capability of experience in natural

environments.

Historically, the influence of romanticism of the nineteenth century, its writing on

the experience of nature, and the conservation movement have culturally shaped the

change in the view of wilderness from something to be feared and conquered to

something to be protected and revered. Wilderness therapy can be traced back in its

origins to the camping and recreation movements serving youth from urban areas in the

mid 1800‟s. The tent therapy programs of the psychiatric hospitals in the early 1900‟s

further highlighted the healing and restorative capability of outdoor experiences. In the

first half of the 1900‟s, there was significant development of the therapeutic camping

movement, which would employ psychiatrists and social workers as consultants, to focus

programs on behavioral change and emotional growth. Since the mid 1900‟s, programs

such as Outward Bound were developed, employing ropes courses, climbing,

backpacking, camping, and physical conditioning to encourage personal growth and

interpersonal skills. As these programs developed in the later 1900‟s, the program‟s focus

also included reflection, processing or debriefing of the experiences. Currently,

wilderness therapy programs have further advanced to include specific courses for at risk

and identified risk populations. As a measure of quality, and in support of outcome

efficacy, many of the current programs employ mental health clinicians as program

facilitators or require non-clinical instructors to have specific training (Berman and

Davis-Berman, 1999).

7

The theoretical framework from which this dissertation aligns with Wilderness

Therapy is rooted in a synthesis of Ecopsychology and Adventure-Based Counseling. The

combination of these therapeutic modalities provides a field of interaction to access the

intrapsychic realm, the relational field in therapeutic experiences, and developmental

growth. Through this foundation, a practice can be created that addresses the human

experience both immersed in a natural environment and actively engaging that

environment. The following paragraphs further describe the theoretical contributions of

Ecopsychology and Adventure-Based Counseling.

Ecopsychology

Ecopsychology suggests that there is a synergistic relation between planetary and

personal well being; the needs of the one are relevant to the other (Metzner,1999;

Roszak, Gomes, & Kanner, 1995; www.ecopsychology.org). This approach does not just

address broad environmental issues, but individual experiences in outdoor environments.

Ecopsychology theory comes from, but is not limited to, the fields of environmental

philosophy, psychology, and ecology.

Biophilia theory (Kellert & Wilson, 1984) states that humans have a genetic

disposition toward being attracted to nature and that exposure to nature supports physical

and mental well being. Neill‟s (2004) theory, Intra-Indigenous Consciousness, states that

the cumulative psychological knowledge of human evolution is genetically stored

(www.wilderdom.com). It is the indigenous psyche within each person that can be

activated through direct experiences with nature, natural elements and natural systems.

These concepts within Ecopsychology are different than traditional views of

human-environment interaction, in that the impact of the natural environment remains

8

largely unaddressed by traditional psychology. Metzner (1998) criticized traditional

psychology in saying:

The fact that we live in these particular kinds of ecosystems, in biotic

communities with these kinds of species of animals and plants, in these

particular kinds of geographical and climatological surroundings, appears

to be irrelevant to our psychology. Yet our own personal experience, as

well as common sense contradicts this self-imposed limitation. (p. 36)

Metzner (1998) further stated that:

Ecopsychology is concerned with revisioning our understanding of human

identity in relationship to place, to ecosystem, and to the cycles of nature.

Indigenous people have a much closer relationship to place and

ecosystem. We need to learn to understand ourselves in relationship to a

place and to the story of that place. (p.37)

Roszak, Gomes, and Kanner (1995) provided an overview of the topics addressed

by the field of Ecopsychology through a collection of essays. In summary:

Ecopsychology goes beyond traditional therapeutic models, which rarely

look beyond the individual, family, and social dimensions of the human

personality, to embrace a planetary view of mental health.

Ecopsychologists recognize that a capacity to live in balance with nature is

essential to human emotional and spiritual well-being, a view that is

consistent with the healing traditions of indigenous peoples past and

present, which is lacking in present-day Western psychological theory.

Ecopsychology explores environmental issues at multiple levels of system.

It explores how the destruction of the biosphere results from irrational

human behavior and how irrational behavior results from a damaged

environment. It delves into our most intimate fantasies and fears. It probes

our most repressed anxieties and depressions seeking the foundations of

our destructive environmental behavior. It asks such crucial questions as:

How can we redefine mental health within an environmental context?

What underlies the irrational consumption habits of modern society? Why

is it that when environmentalists speak of the need to reduce consumption

they arouse such anxiety, depression, rage, and panic? How can the

environmental movement find more effective ways to win the hearts and

minds of the public than by endlessly scaring, shaming, and blaming?”

(abstract, PsychINFO database)

9

Ecopsychology turns around these global/societal/community issues and explores

their influences on intrapsychic and interpersonal well being and how the issues are then

acted out in the individual, family, and social dimensions.

Adventure Based Counseling

Adventure Based Counseling takes outdoor experiential models and combines

them with psychotherapeutic disciplines. It differs from traditional counseling in that the

approach includes the natural setting, the use of real and perceived risk, additional

required skills, additional ethical considerations, an emphasis on processing and

metaphor, and the transfer of learning to psychological, educational, sociological,

physical, and spiritual benefits. Adventure Based Counseling can be used as a primary

treatment or as an adjunct to more traditional types of counseling (Fletcher & Hinkle,

2002).

Itin (2001) identified Adventure-Based Counseling as both the use of specific

activities (i.e., games, initiatives, trust activities), high adventure (i.e., rock climbing,

white water) and wilderness (i.e., backpacking, canoeing, hiking, ect.) in conjunction

with a philosophy that actively embraces the unknown, in which the challenges

encountered are seen as opportunities, and the group is seen as an essential element of

individual success and opportunities or genuine community are promoted.

Adventure Based Counseling is a therapeutic tool that can be adapted to almost

any setting and is a mixture of experiential learning, outdoor education, group

counseling, and intrapersonal exploration (Schoel, Prouty, & Radcliffe, 1988). The

theoretical base of adventure-based counseling includes, but is not limited to,

Experiential Learning and Outward Bound principles. Dewey (1938) offered foundational

10

work in experiential learning, with the basic concepts that learning is based in the

experience of the present moment. Experiences of greater significance facilitate more

significant learning.

The Outward Bound Model was created by Kurt Hahn in the 1930‟s and became

formalized as Outward Bound School in 1941. Outward Bound is the leading wilderness-

adventure/outdoor education organization in the world. It has been in existence for over

60 years. The Outward Bound Model includes five components that facilitate

opportunities and expand principles of lived experience (James, 1980). The components

of facilitated experience are: 1) students pledge themselves to personal goals; 2) control

of time and activity; 3) adventure and risk in order to cultivate a passion for life; 4)

operating in small groups to develop the natural leadership present in most people but

often suppressed by other facets of modern life; 5) a dedication to community service.

The expanded principles of lived experience are: fitness, initiative and enterprise,

memory and imagination, skill and care, self-discipline, and compassion. The Outward

Bound model has 5 core values: 1) adventure and challenge enhances leadership; 2)

learning by doing results in confidence; 3) teamwork leads to compassion and service; 4)

stewardship through social and environmental responsibility, and 5) time for perspective

and reflection supports character development (www.outwardboundwilderness.org).

The assessed interventions offered to the adolescent participants for the purposes

of this research followed the models and principals of ecopsychology and adventure

based counseling. The most significant link between the interventions and the models and

principles was based in the interventions‟ foci on emersion, experience, and challenge

within the natural environment. Further, the interventions supported a developmental

11

process through an emphasis on participants‟ experiences of intrapsychic exploration,

relationship with the environment, community building, and service. One intent was for

participants to experience a deepening of awareness of relationship between self and

environment, deepening their recognition of the influence of environmental issues upon

personal and interpersonal wellbeing that is acted out in individual, family, social, and

community dimensions.

Along with such principals as learning by doing, challenge promotes leadership,

and reflection supports development, Gestalt therapy theory offers additional theoretical

concepts which supported this research. The following paragraphs highlight several such

Gestalt therapy theory concepts.

Gestalt Theory and the Change Process

Gestalt therapy theory (Perls, Hefferline, & Goodman, 1951) is experientially

based. It is rooted in the fundamental concepts of field theory, phenomenology, and

holism. In working with an individual toward therapeutic and developmental change, the

work is focused at the center of the individual‟s experience. Experience is based on the

convergence of interpersonal, relational, and environmental forces. The individual, in his

or her development, is recognized as a phenomenon of body, mind, emotion, spirit,

relationship, and creativity.

Holism

Gestalt therapy theory views nature and existence as a unified whole, “greater

than the sum of its parts.” Human experience and our related perceptions are seen as a

process of development of a fuller awareness, becoming meaningful wholes, or gestalts

12

(Perls et al, 1951; Crocker and Philipson, 2005). The holistic approach of Gestalt therapy

theory is described, stating;

We see that meaningful wholes exist throughout nature, in physical and

conscious behavior both, in the body and the mind. They are meaningful

in the sense that the whole explains the parts; they are purposive in that a

tendency can be shown in the parts to complete the wholes.

(Perls et al, 1951, p.34)

Field Theory

Field theory (Lewin, 1951) strongly influenced the holistic perspective of Gestalt

therapy theory (Perls et al, 1951). The term field is taken from physics, describing a

configuration of forces. Applied to psychology “the field” is describing the complex

interrelationship of forces, effects, influences and events forming a unified interactive

whole (Parlett & Lee, 2005). The “field” is inclusive of;

The many environmental conditions and influences that conceptualize our

existence relating to all or specific elements… the parts of our field are not

separate. They are intimately intertwined, inextricably interwoven into

wholes of perception and involvement.

(Parlette & Lee, 2005, p.44)

As a fundamental construct of Gestalt therapy theory, Field theory brings to light

the unit of inquiry as the interaction of organism and environment or the

organism/environment field (Perls et al, 1951). Adolescent development and the

transformative process is;

Understood as a progressive unfolding of the comprehensive field, an

unfolding that includes-structuring of childhood unity, expansion and

differentiation of life-space, and the transformation of the boundary

processes that organize and integrate the field. (McConville, 2001, p.38)

Phenomenology

The self in experience is a phenomenon of the organism/environment field. This

phenomenon of interaction between organism and environment further defines the unit of

13

work in Gestalt therapy (Perls et al, 1951). The Phenomenological Method in Gestalt

therapy structures intervention goals to develop and deepen awareness of self in

interaction with environment as both internal and external phenomenon. In applied

practice the Phenomenological Method in Gestalt therapy moves the practitioner to value

description over interpretation and to seek to know the clients‟ lived experience over an

“objective truth” (Crocker & Philipson, 2005).

Central to Gestalt theory‟s explanation of the change process is the foundation of

developing awareness. Fodor (1998) described a model of change through experience that

facilitates awareness, awareness that initiates a process of meaning making:

A holistic view of awareness process includes sensory, emotional, and

conceptual processes operating together to create the individual‟s

phenomenological perspective of the world. Making meaning of these

moment to moment experiences is an intrinsic piece of the process.

Another aspect of this process is the awareness of how am I becoming

aware - how am I creating my story and enhancing awareness of other

possibilities for experiencing. (p. 69)

The Gestalt change model of experience that facilitates awareness, awareness that

initiates a process of meaning making, has guided this dissertation in inquiry as a

foundation for the research questions, the research process, and as a strong influence in

the analyses and presentation of the qualitative data.

The Gestalt change model has two additional components that are most relevant

to this dissertation. First, the process of experience and awareness occurs in sequence, as

depicted in the Gestalt Cycle of Experience. This is represented by Perls (1976) as a

continuum of phases, “where awareness emerges into a foreground, is experienced,

changed, assimilated, and then falls into the background as the next awareness emerges”

(Fodor, 1998, p.54). Second, the Paradoxical Theory of Change (Beisser, 1970, 2001)

14

offers that the more one becomes fully who they are and embodies authentic experience,

the greater is the potential for change. It is through this authenticity of self in the

experience that the ground develops for change to occur. The concepts of awareness,

figure/ground, the Cycle of Experience, and the paradoxical theory of change are

described in more detail in the following paragraphs.

Awareness and Figure/Ground

Yontef (1993) stated that “the word Gestalt refers to the shape, configuration or

whole, the structural entity, that which makes the whole a meaningful unity different

from a mere sum of parts. Nature is orderly, it is organized into meaningful wholes. Out

of these wholes, figures emerge in relation to a ground and this relationship of figure and

ground is meaning” (p.182). Nevis (1987) described figure/ground through a metaphor of

walking through a forest (ground), then noticing and attending to a single tree (figure).

Awareness is the process of increasing focus on a figure that is emerging from the

background through increasing attention and deepening interest. Fodor (1998) described

awareness as “a central concept in Gestalt therapy. It focuses on experiencing one‟s

sensed impressions of the world, and highlighting of the awareness process is a central

feature of therapeutic work” (p. 50).

For the participants in this dissertation research, an example of an emerging figure

may have been a sense of personal strength in facing a perceived fear or risk with a horse

or while experiencing a cave challenge, coming forward from the ground or background

of their adventure experience. Emerging figures may lead participating individuals to

become aware of an increased sense of self-efficacy after overcoming the challenge. The

concept of awareness is apparent in the Cycle of Experience.

15

The Gestalt Cycle of Experience

The Gestalt Cycle of Experience has been described as a continuum of phases

(Woldt and Toman, 2005), (Nevis, 1987), (Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman, 1951).

Together these phases and the movement between them constitute the process of

experience. The experiential phases of the cycle presented in order are sensation,

awareness, mobilization of energy, action, contact, integration or assimilation, and

closure or withdrawal. Sensation is the ground that is becoming figural as it moves into

awareness. It is the information of the senses and lived processes that are moving into

consciousness. The transition from sensation to awareness involves a sensation

experienced in the ground becoming figural, of concern or importance. “True awareness

is the spontaneous sensing of what arises or becomes figural, and it involves direct and

immediate experience.” (Nevis, 1987, p.23). Nevis (1987) related the work of self-

development as being largely devoted to improving and expanding one‟s available

awareness. The transition from awareness to energy mobilization is the stimulation

related to the emerging figure. Deepening awareness, deepening concern, deepening

importance is the motivation to enact the effort related to the figure. Mobilized energy is

the “springboard” of experience into the action and contact phases. Action is the

beginning manifestation of interest and intention. It draws together the attention and

aroused energy to an active response, “an aggressive response to a figure of interest, a

form of active participation in which the figure is literally transformed through work to

comprehend and assimilate it” (Nevis, 1987, p. 27). Contact is the phase when one

touches the boundary of self and other. It is the phase “in which a fully developed

experience emerges from working with a figure of great interest” (Nevis, 1987, p. 28).

16

Learning and change occurs when one leans into their boundary. “It is

acknowledgement that to make contact of any kind is to learn something about the

present state of affairs” (Nevis, 1987, p. 29). Integration and assimilation is “a form of

active participation in which the figure is literally transformed through work to

comprehend and assimilate it … in that the perceiver changes his or her perceptual

cognitive awareness” (Nevis, 1987, p. 27). Resolution and closure is to withdraw from

the figure. It is to acknowledge the experience and the learning, to recognize completion

of a unit of work.

In completing the outdoor experiences of this research, the participants moved

through the cycle of experience as they hiked on rough terrain. By exemplifying the cycle

through this experience, the cycle began with a sensation of unsteadiness or imbalance.

The awareness may be a need to be more present, to attend to the physical ground, or to

have more intentioned movements and a wider stance. Mobilization of energy may be a

deepening of need as one continues to stumble and a focusing attention on their physical

body and creating a mental picture of their intended physical changes. Action may be

making the shift in their physical body. Contact may be a fuller shift of their attention to

the interaction between their body and the ground and recognizing and deepening of

experience of themselves in a fuller embodied presence attaining better balance and

stability as they continue to hike. Integration and assimilation may be an enjoyment and

reflection on their experience of heightened ability and self-efficacy with a fuller

embodied presence and considerations of the potential applications and benefits of

embodied presence in other aspects of their lives. Closure and withdrawal may be a shift

from embodiment to something in the natural environment that catches their attention.

17

Movement through the cycle is one way to describe the process of change.

Another change model in Gestalt therapy theory is the Paradoxical Theory of Change.

Paradoxical Theory of Change

Change occurs when one becomes what they are, not when they try to become

what they are not. Change does not take place through a coercive attempt by the

individual or by another person to change. The more one becomes fully who they are and

embodies their authentic experience, the greater is the potential for change. It is through

this authenticity of self in any experience that the ground develops for change to occur.

Change does take place if one takes the time and effort to be what they are, to be

fully invested in one‟s current positions. Change is the natural state of humankind, is

movement towards wholeness where there is constant change based on the dynamic

transactions between the self and the environment (Beisser, 1970, 2001).

Gestalt therapy and the Wilderness-Centered Rites of Passage are experiences

where emersion in nature brings a person to their natural or authentic state. This is a

mirroring process of observing and experiencing an environment in its natural state. The

experienced serenity of the natural world can alleviate structures of social conformity and

obligation that diverge one from their authentic self. From the adventure-based

perspective, a person on their edge in a nature challenge or one that finds adaptation

through overcoming wilderness obstacles is accessing the fullness of their being,

manifesting their authentic self. Achievement in such an experience is a process of

awareness of self, in one‟s capacity, in one‟s limitations, in knowing the self from which

adaptation is occurring because of desire or necessity.

18

The methodology of Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage is to create or access

experiences that heighten awareness. Through experience, one is moved to introspection,

making meaning and recognizing the self in new ways. One is drawn into environment,

experiencing the person-environment or person-person(s)-environment in new, different,

broader, deeper, and more expansive ways.

Gestalt, Adolescent Development, and the Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage

This dissertation focuses on transformative process as experienced by the

adolescent participants. Adolescence is a time of significant developmental

transformation in the human lifespan. In Gestalt Therapy theory, the developing child, in

their adolescence, is a product of the organismic-environmental and intersubjective fields.

Development, from a Gestalt perspective, involves both the organization

of interpersonal relationships and the differentiating of internal

experience. But in the Gestalt approach, no domain or change is prior to

another: both of these are expressions of a more comprehensive

organization of the field, an evolution of the contact functions, and

boundary processes that define the very meaning of self.

(McConville, 1995, p.7)

Prior to adolescence, the child is embedded in the family field. Introjects that the

child makes originating from the family system, phenomenon of culture, beliefs,

constructs, and behaviors, completely influence and structure the child‟s reality. At the

time of adolescence, the embedded self configuration is more subject to the modeling and

adaptations brought by the environment and family system than by a sense of agency and

autonomous self that emerges later.

To describe the child self as embedded is to say that its relationship to its

milieu is an essential part of its very nature. The child self is precisely a

self of the family field. … To say the child self is embedded is essentially

to say that our earliest experiences of self are configured according to the

19

relational field of childhood. As adolescence gets under way, the

experience of self includes more and more separateness, ownership, and

organizational integrity. The self becomes more of a gestalt- a segregated,

coherently organized whole. (McConville, 1995, p. 28-29)

In Gestalt therapy theory, the self is located at the contact boundary. The

developmental process of self is occurring through deepening contact occurring at the

boundary between self, other, and environment. This is described as the place of creative

tension experienced between self and other, organism and environment, intrapsychic and

interpersonal worlds (McConville, 1995). Polster and Polster (1973) described “the

contact boundary is the point at which one experiences the „me‟ in relation to that which

is „not me,‟ and through this contact, both are more clearly experienced” (p. 102).

Contact functions are emerging and evolving throughout the adolescent

developmental process. A deepening and more defined awareness of the intrapsychic and

interpersonal processes, the interrelatedness of the interior and outer worlds, are figural to

the emergent self throughout the adolescents‟ development. As explained by McConville

(1995);

developing the capacity for contact (that is, for developing boundary

conditions that support both joining and separating) is what adolescence is

all about. …The capacity for contact is the primary underlying

organizational and motivational purpose of adolescent development. (p.5)

Through a clearer sense of boundary the adolescent is defining and refining

themselves in relationship to their family, peers, other adults, and their forming social

world. McConville also explained that;

The term boundary expresses the fundamental dialectical structure of

contact itself: it is a two stroke process: one stroke is the capacity to

merge, give out and take in, influence and be influenced; the other is the

capacity to separate and bound, resist influence and maintain one‟s unique

and essential characteristics.

20

(1995, p. 5)

The polarities between the child-self and the adolescent-self create a condition of

tension and ambivalence in the internal experience; through the developmental process

the adolescent develops a more balanced self.

The field where full and satisfying contact is possible is one in which a

dynamic balance is achieved between the organism‟s organizational

integrity and its capacity to interact with its environment. The maturation

of the field is the goal of adolescent development, the dynamic

equilibrium toward which adolescent development tends.

(McConville, 1995 p.102)

Adolescent development is presented by McConville (1995) in a 3 phase model of

disembedding, interiority, and integration. These phases of adolescent development align

with the 3 stages of rites of passage separation, transition, and reintegration. (vanGennep,

1909;1969)

Disembedding

The disembedding phase is identified as the adolescent beginning a process of

differentiation, emerging from the introjects of the family system and other social

influences. Orienting toward the individuated self, the adolescent develops a stronger

sense of boundary, taking on ownership of self and authorship of experience. The

deepening of the intrapsychic and interpersonal awareness supports the adolescent in

regulating and grading the contact process. This further initiates for the adolescent the

intrapsychic and interpersonal struggles and conflicts at the polarity of dependence and

independence, having need for adult support while wanting to disengage from adult

influence. Disembedding is described as a separation of the adolescent from the family

and other social systems. In the rites of passage process this disembedding is supported

through the separation phase as a structured ritual occurs which provides the adolescent

21

with experience and distinction to distance and differentiate from the former embedded

structure and identity. The developmental growth provides recognition of the emerging

autonomous self.

Interiority

In the interiority phase the adolescent explores the differentiated intrapsychic and

interpersonal fields, actualizing their sense of agency and authorship. The intensified

inner landscape accessible to the adolescent provides deeper capacity for reflection and

unique self-expression.

The developmental work at this stage is to expand the boundaries of the

self to include aspects of experience previously relegated to ground, or

projected onto environment. In this way the adolescent becomes more

interior, more reflective, and more conflicted within himself. Issues

previously wrestled out with parents or peers now become struggles within

the boundaries of the self. This is the phase when polarities, previously

mapped across the self-environment contact boundary, emerge as inner

divergences that the self recognizes as its own.

(McConville, 1995 p.115)

Interiority is supported through the transition phase of the rites of passage process

with specific ritual and challenge that provides direct experience of liminality. Liminality

is a period of transition, a place in between, where one is transforming. The initiate

experiences opportunities for self reflection, achievement through overcoming obstacles,

creative individuation, and recognizing strength within and beyond self. The liminal

practices in the transition stage of rites of passage bring the struggles of interiority to the

surface through direct experience in a structured and supported container. The adolescent

is directed to deepened intrapsychic experiences, enlightening the path toward their

actualized and autonomous self.

22

Integration

The developmental process of the integration phase is movement toward a

comprehensive and inclusive self from a partial and fragmented self.

The self emerges progressively through adolescent development as a

higher-order gestalt that integrates increasingly diverse aspects of self and

promotes an ever-growing sense of ownership of experience. …The

boundaries of the psychological self have attained enough resilience and

sturdiness to support mature contact (interchange with others that allows

mutual influence without risk of disintegration).

(McConville, 1995, p.117)

Adolescents through this phase are gaining a cohesive self, capable of joining and

standing with in their difference. McConville (1995) explained that, “older adolescents

become truly complex beings in their own experience and can identify not just with a

specific impulse or want in a specific situation but also with the need to literally be a

framework sufficiently broad to encompass and integrate discordant shards of

experience” (p.117). Integration is supported through the reintegration stage of the rites

of passage process specifically through the ritual return to community that affirms

attained identity and cohesive sense of self. The adolescent is recognized as an individual

that is part of a community or family system through ceremonial recognition. As

McConville (1995) stated, “the goal of adolescent development is not independence but

rather interdependence” (p.118). In rites of passage the initiate is both supported in their

individuality and directed to a place of belonging.

The wilderness-centered rites of passage model advocates for providing structures

to support adolescents through developmental transformations. Through each of the

phases of adolescent development described above, an organization of experience is

offered which holds up the adolescent in healthy transformation and can redirect

23

vulnerable children from maladaptive patterns and self-destructive behaviors when

organized rites of passage are absent. Rites of passage experiences provide ritual

separation as opposed to secretive behavior; opportunities for reflection and challenge as

opposed to drugs, alcohol, and other risk taking behavior; and ways to experience

acceptance and be upheld in community as opposed to relying on maladjusted peers for

validation. Structure and guidance through rites of passage can address the turmoil of

adolescence and support wellbeing through this time of transformation.

A Gestalt Methodological Research Approach

Phenomenology, as stated earlier, is a foundational thread of Gestalt therapy

theory. These foundational roots of Gestalt therapy include the phenomenological and

existentialist work of Husserl (1931), Marleau-Ponty (1962), Heidegger (1927/1962), and

Bubber (1914), Van De Reit (2001), McConville (2001), Blaize (1998). Crocker and

Philipson, (2005) stated;

the phenomenological method in Gestalt therapy involves a process that

seeks to discover how the client‟s beliefs, and her understanding of events

and persons in her life, function in the client‟s own organization of

experience, and therefore how they function as the ground of her

cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses to current and ongoing

situations. (p.69)

The theoretical framework, from which this dissertation research was approached,

was Phenomenological Research. Phenomenological research theory is aligned with the

study of an individual‟s internal change process facilitated by experience. The

methodology of this study was generated from the Phenomenological research

methodology of Spinelli (2005, 1989), Polkinghorne (1989), Giorgi (1985), and Van

Kaam (1969). These authors identified phenomenological research as descriptive and

24

qualitative, an inquiry leading to the participants‟ and the researcher‟s description of

experiences. It asks how meaning presents itself in experience. Researchers attend to

what is present and in awareness, focusing on the meeting of person and world.

The research goals and Gestalt therapy theory principles align, in that the learning

is in the doing, the participants‟ need to describe their experiences will enhance

awareness and those awarenesses will enhance the meaning each makes of their

experiences. Change is predicted to occur when participants are free to become more of

who they really are and when enhanced awareness encourages movement through the

subsequent phases of the Cycle of Experience. The analysis of change and assessment of

the change process are further delineated in the research questions.

Research Questions

The research process centered on group participation in a wilderness-centered rite

of passage experience. Based on the phenomenological research approach the following

questions guided this study:

Q1: What are the intentions and expectations of participants in the wilderness

centered rites of passage experience? (What prior beliefs, contexts, experiences

are influencing these intentions and expectations?)

Q2: What awarenesses did the participants‟ experience?

Q3: How did those awarenesses occur within the framework of the wilderness-

centered rites of passage experience?

Q4: What meaning do participants make of these awarenesses?

25

Q5: What meaning do participants make in translating and applying their

experiences and awarenesses to their life experiences?

Q6: (a) What change or transformation do participants recognize from the

experience?

(b) How did that change/transformation occur?

Q7: What prior beliefs, contexts, experiences are influencing the outcomes of

Research questions 2-7?

Predicted Limitations of the Research

This study was conducted with a limited number of participants, four participants.

With this number of participants, the research can not be generalizable, but can provide

examples of individual experiences and processes. Subjectivity is taken into

consideration and addressed through the use of collaborative and participatory research

methods and a strong emphasis on researcher/participant reflexivity is incorporated into

the research process. This is accomplished through researcher/participant partnership in

the research process, emphasizing reflexive processes and the utilization of participant

generated data in representation and description of experience and transformative

processes (Marrow, 2005; Tolman & Brydon-Miller, 2001).

My strong positive bias toward Wilderness Therapy Theory and Rites of Passage

Theory is based in my personal and professional experience. This could also be

considered a limitation, in that it also may have influenced the analyses and presentation

of this work. These limitations were ameliorated by adherence to the representation of

26

participants‟ authentic experiences by staying close to the participants‟ words, letting

their own voices be presented in the description of their experiences.

Potential Significance of the Study

The results of this study form a narrative description and representation of the

experience and transformative process of the participants. Such examples can be used to

support practitioners in designing, facilitating, and the processing of such experiences. It

is important that we continually invest efforts to develop structures that support the

developmental process of our youth. Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage can provide a

therapeutic and developmental experience that is different from traditional modalities.

This difference can provide a qualitative connection for a participant that is not bridged in

traditional therapeutic modalities. Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage, as an alternative

or adjunct modality, can make a difference and open new avenues of transformation for

participants in which traditional modalities may not have been nor will be effective.

Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage, as a means of supporting our struggling youth,

deserves our attention and effort. It provides a possible means to develop positive

qualities, by strengthening the existing structure and foundation and opening a door of

new possibilities and potential. Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage is a means of

addressing at-risk behaviors before they become damaging. It can be reparative once such

behaviors have had a damaging impact. It offers an experience that is both nurturing and

supportive while holistically challenging. Wilderness Centered Rites of Passage can

support the development of resilience that reduces the impact of the multi-systemic issues

27

faced by our youth in society as a whole, and can provide a healthier more positive

experience of growing up.

Summary

This first introductory chapter offered an overview of Rites of Passage,

descriptions of types of outdoor adventure, along with theoretical foundations from

Gestalt therapy theory.

The next chapter provides an overview of the relevant literature and research

pertaining to this study. This includes research about rites of passage and wilderness

therapy. A portion of the next chapter describes the literature which illustrates a

relationship of rites of passage and wilderness therapy to Gestalt therapy theory. Lastly

Chapter 2 focuses on the literature that links qualitative research methodology to Gestalt

therapy theory.

28

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE AND RESEARCH

The following literature review summarizes research and publications in the

existing theories and models related to this study. This review is intended to provide and

develop support for a conceptual framework in which to place this study. This literature

review also includes studies related to bridging this dissertation‟s theoretical foundations

and methodology with existing literature from Gestalt therapy theory. The purpose of

addressing this study from a Gestalt lens is threefold: to provide a theoretical context for

this study, to support expansion of the field of Gestalt research in theory and practice, and

to inform qualitative researchers of the utility of Gestalt therapy theory. First the

reviewed literature in this chapter addresses Rites of Passage in general, Wilderness

Therapy and related outdoor adventure studies, then the relevant Gestalt therapy

literature.

Rites of Passage

Rites of Passage, as described in the literature, include both culturally centered

and universal aspects of transitional rituals. The literature also addresses the critical

29

component of growth in a society lacking in such structured ritual. Delany (1995),

through examining Rites of Passage in different cultures, found certain elements to be

common to all Rites of Passage and those Rites of Passage, in some form, are universal to

the experience of adolescence. Quinn, Newfield, and Protinsky (1985) reported that

culturally defined and accepted Rites of Passage have given way to a more vague and

meaningless set of adolescent expectations and affirmations. They described how the loss

of Rites of Passage has interfered with the mission of the family to promote functional

adolescent development and with the ability of the family during this life cycle stage to

operate with a sense of community attachment. Scott (1998) evaluated Rites of Passage

as a means of understanding and working with adolescents in a contemporary context

asserting that Rites of Passage assist us, as mentors and guides, to support adolescents in

their development, sense of values, and connectedness.

Indigenous cultures have traditionally utilized Rites of Passage to support the

adolescent‟s transition to adulthood. Correal (1976), in a comparative study of adolescent

Rites of Passage in indigenous cultures, found a commonly proscribed series of

experiences, mainly magical and ritual, by which a child is given the rights and

responsibilities of an adult. Correal concluded that such rituals tie the people to the past

history of the cultural group and also delineate their future roles as adults. Markstrom and

Iborra (2003) examined identity formation of Navajo adolescents in the context of

traditional ceremonial Rites of Passage. Their methods included analysis of literature,

observations of ceremony, and discussions with experts. Findings showed that the Rites

of Passage rituals supported an optimal identity formation that was gender based and

immersed in Navajo culture.

30

Merkur (2002) examined the vision quest experience of adolescents from the

Ojibwa culture from a Psychoanalytic perspective. Merkur analyzed six narrative self

reports of the adolescents‟ vision quest experiences. Findings indicated that vision quests

supported healthy development through manifestations of ego ideals, leading in most

cases to improved ego-superego integration.

From the above articles it can be concluded that the healthy development of our

youth can be supported through Rites of Passage rituals. Additional studies were

identified which address rites of passage specifically in the context of wilderness therapy.

Wilderness therapy is defined as a therapeutic experience that takes place in a wilderness

setting where focus is placed on naturally occurring challenges and consequences

(www.wilderdom.com). The following section provides a summary of publications which

merge Rites of Passage and Wilderness Therapy.

Wilderness Therapy

In limiting the scope of this chapter, the representation of Wilderness Therapy in

this literature review focuses on its use with the adolescent population. Wilderness

Therapy, as a medium of intervention, has shown efficacy in the achievement of positive

growth and change for many adolescent populations in multiple dimensions (Bettman,

2007; Russell, 2003; Gass, 1993). These applications are demonstrated through review of

the following literature.

Carson and Gillis (1994), in examining 43 wilderness adventure oriented studies

of programs serving adolescents, found that participants had a more internal locus of

control, better grades, more positive attitudes, and increased self concepts following the

31

wilderness interventions. Hattie, Marsh, Neill and Richards (1997), in a meta-analysis

about the impact of wilderness adventure programs, found that participants experienced

positive changes that remained stable after follow up in the dimensions of self-concept,

leadership, academic, personality, interpersonal, and adventure orientation.

Wilderness Therapy has been used with experiential family counseling for

families with adolescents in a multifamily group format. Research by Bandoroff and

Scherer (1994) is a comparison study with 27 participant families in a four day program

designed to combine wilderness therapy interventions with intensive experiential family

therapy. This study found greater positive outcomes in the measures of family

functioning, behavior, and self-esteem among the 27 participant families as compared to

39 non-participant families.

Wilderness therapy interventions have been used with clients diagnosed with

psychopathology and/or behavioral disorders. Kelly, Coursey and Selby (1997)

conducted a study with 57 people diagnosed with serious and persistent mental illness,

receiving outpatient treatment, who participated in a weekly, day long wilderness therapy

program for nine weeks. They found significant increases in self-efficacy, self-esteem,

trust and cooperation, as well as significant decreases in anxiety, depression, hostility,

and interpersonal sensitivity in the 57 adolescent participants compared to a 19

participant control group. Sachs and Miller (1992) in a study of 16 behaviorally

disordered adolescents evaluated the impact of a wilderness therapy program on

participants‟ cooperative and aggressive behaviors. Utilizing both standardized measures

and direct observations, they found significant positive changes in both aggressive and

cooperative behaviors after completion of the wilderness therapy program.

32

Bruyere (2002) reviewed the literature regarding utilization of wilderness therapy

as an intervention for male juvenile delinquent offenders. This article presented

appropriate benefits and realistic outcomes on which wilderness program design

components could be based for this population. According to Bruyere, design using a

benefits-based management approach aligns desired outcomes with program itinerary and

emphasis. These include building connection to communities, equipping youth with skills

to overcome obstacles, enhancing self esteem, providing healthy and facilitated

opportunities to take risks, being physically active, and support defining personal

identity. Necessary program aspects are maintaining an informal environment, inclusion

of participants in planning, employing dedicated and sincere staff, long term follow up to

sustain and build upon the benefits received.

Parker and Stoltenberg (1995) examined the efficacy of wilderness adventure

programs used as an adjunct to traditional counseling with boys identified as displaying

difficulties including classroom behavior problems, inadequate social skills, academic

difficulties, or environmental issues putting them at risk for delinquency. Eighty four

boys (aged 12-18 yrs) were divided into 4 groups: counseling and wilderness adventure,

counseling only, wilderness adventure only interventions and a no-intervention control.

Participants completed assessments measuring apathetic isolation, adolescent turmoil,

dependence and inhibition, locus of control, and self-esteem. Participants were assessed

at pre- and post- treatment and at 6 month follow-up. Findings indicated significant long-

term influence of the adventure interventions alone occurred only in areas of reducing

apathetic isolation and increasing internal locus of control. Outcomes improved when

adventure was integrated with on-going counseling to demonstrate decreases in apathetic

33

isolation, adolescent turmoil, and increase in self-esteem. For counseling alone, long term

gains were more limited demonstrating no change in areas of locus of control and self-

esteem, less positive change than treatment in apathetic isolation, same amount of change

in adolescent turmoil, and greater long term positive change than adventure and

counseling in dependence and inhibition. Findings indicated most significant change

occurred when adventure was integrated with on-going counseling. This study

demonstrates that wilderness therapy programming as a counseling adjunct has greater

efficacy to improve outcomes than the treatment of counseling alone.

Gills and Simpson (1991) studied an adventure based counseling intervention and

treatment with court-referred adolescent drug abusers. The authors studied the

experiences of 29 adolescents attending an 8-wk residential treatment program for drug-

abusing, adjudicated adolescents. The interventions used an adventure-based counseling

model to instill change. Counselors rated the participants using the Revised Behavior

Problem Checklist (Quay & Peterson, 1987). The participants also rated themselves and

were rated by peers regarding behavior change and underwent random urine screenings

for drug use. Participants completed the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory

(MMPI; Hathaway & McKinley, 1982) and the Battle Culture-Free Self-Esteem

Inventory (Battle, 1981). Statistical analyses of the instruments and reports from this

group indicated that the program had a significant positive effect on participants‟

behaviors.

The previous sections have separately reviewed Rites of Passage research and

Wilderness Therapy research. This next section of studies focuses on research that

34

combines both Rites of Passage and Wilderness Therapy. The following studies are most

aligned with the research topic and methods of this dissertation.

Research Literature Aligned with this Study

This review highlights specific examples of research on Rites of Passage,

Wilderness Therapy interventions, and specific studies of the use of Wilderness Centered

Rites of Passage with adolescents that utilized qualitative methods. The studies have

shown that, similar to indigenous ceremony and ritual, contemporary adolescents are

being supported in development and connection to self, others, and community through

Rites of passage, wilderness therapy, and the Wilderness-centered Rites of Passage.

Doucette (2004) conducted a qualitative study with eight students (aged 9 to 13

years) that explored the question: “Do preadolescent and adolescent youths with

behavioral challenges benefit from a multimodal intervention of walking outdoors while

engaging in counseling?” (p. 373). For eight weeks, students from a middle school in

Alberta, Canada participated weekly in the Walk and Talk intervention. Students' self-

reports indicated that they benefited from the intervention. Research was triangulated

with reports from involved adults who supported findings that indicated the students were

making prosocial choices in behavior, and were experiencing more feelings of self-

efficacy and well-being. The results of the Walk and Talk intervention study showed that

the youth felt better about themselves, explored alternative behavioral choices, and

learned new coping strategies and life skills by engaging in a counseling process that

included the benefits of mild aerobic exercise, and that nurtured a connection to the

outdoors.

35

Quamina (2003) examined five young adolescent men of color who underwent a

spiritual rite of passage and experienced a series of dialogues with an emphasis on Self-

Awareness, Self-Determination, Identity, and Spirituality. This study examined how

meaning and purpose can be restored through the implementation of a spiritually based

rite of passage. A qualitative participatory research methodology was utilized to generate

the topics of rediscovery through the collective of participants, and provide actual voice

to clarify and create a renewed understanding of the benefits of a rite of passage.

Members participated in a four-week indigenous model of intense learning that imitated a

model similar to their original ethnic heritage. In this study, conclusions indicated that by

going through a spiritual Rite of Passage and by reclaiming their indigenous voices, the

participants experienced a reintroduction to their mission and purpose in life, their

intricate connection with nature and spirituality, reinvigoration of their human orientation

and stewardship, their intrinsic value and worth as human beings, and preparation for the

anticipated stages of adult life and living.

Hunter (2000) studied 8 adolescent Caucasian participants in a wilderness based

Rites of Passage program, five females and three males from diverse socioeconomic

backgrounds. The researcher interviewed each participant 3 times: before the wilderness

rite, immediately following, and 1 year later. During these interviews the researcher

recorded the participants' current life issues, reasons for participation, the experience

itself, and their incorporation of the experiences over the following year. This

transpersonal research focused on 3 critical aspects of the youths' experiences: the issues

young people face as they transition into adulthood, the impact of the rite of passage on

that transition, and the resulting wisdom. Using organic inquiry, the treatment of data

36

included (a) presentation of the individual stories, (b) thematic analysis, and (c)

transformative change in the researcher resulting from the study. Findings showed that

participants attributed the following to the wilderness based Rites of passage experience:

increased self-esteem, clarity, self-understanding, responsibility for environmental and

social issues, spirituality, insight into the lived experience, and movement from

masculine to feminine values. Themes of their work included separation from family,

importance of community, psychological healing, sexuality and relationship, education

and work, drugs, and creativity. The author expressed the importance of wilderness rites

of passage in the critical task of reversing the prevailing cultural perception which

discredits the voices of young people to one which empowers youth to become capable

messengers of personal and collective wisdom.

Foster (1998) conducted a descriptive study of the initiatory experiences of 9

adolescents (aged 16-19 yrs) engaged in a wilderness rite of passage experience. The

study utilized participant observation, experiential narrative, and researcher reflection to

generate description. The structure for the 10 day vision quest program included: four

days of intensive preparation, three days of alone time and fasting in the Sierra Nevada

Mountains, and three days of story telling in the elders‟ council. Findings of this study

asserted that adolescents‟ “hunger for experiences that heal childhood wounds and bring

them face to face with their true nature, as is reflected in the mirror of the wilderness” (p.

213). The author argued that the adolescent drive to "grow up" is the same drive that