SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

published: 06 March 2020

doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

The Impact of Climate Change

on Mental Health: A Systematic

Descriptive Review

Paolo Cianconi 1*, Sophia Betrò 2 and Luigi Janiri 1,3

1 Department of Neurosciences, Institute of Psychiatry, Catholic University, Rome, Italy, 2 Institute of Psychopathology, Rome,

Italy, 3 Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Rome, Italy

Edited by:

Konstantin Loganovsky,

National Academy of Medical Science

of Ukraine, Ukraine

Reviewed by:

Maria Teresa Avella,

University of Pisa, Italy

Batul Hanife,

Azienda Provinciale per i Servizi

Sanitari, Italy

*Correspondence:

Paolo Cianconi

pcianco@gmail.com

Specialty section:

This article was submitted to

Public Mental Health,

a section of the journal

Frontiers in Psychiatry

Received: 07 August 2019

Accepted: 28 January 2020

Published: 06 March 2020

Citation:

Cianconi P, Betrò S and Janiri L (2020)

The Impact of Climate Change on

Mental Health: A Systematic

Descriptive Review.

Front. Psychiatry 11:74.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

Background: Climate change is one of the great challenges of our time. The

consequences of climate change on exposed biological subjects, as well as on

vulnerable societies, are a concern for the entire scientific community. Rising

temperatures, heat waves, floods, tornadoes, hurricanes, droughts, fires, loss of forest,

and glaciers, along with disappearance of rivers and desertification, can directly and

indirectly cause human pathologies that are physical and mental. However, there is a clear

lack in psychiatric studies on mental disorders linked to climate change.

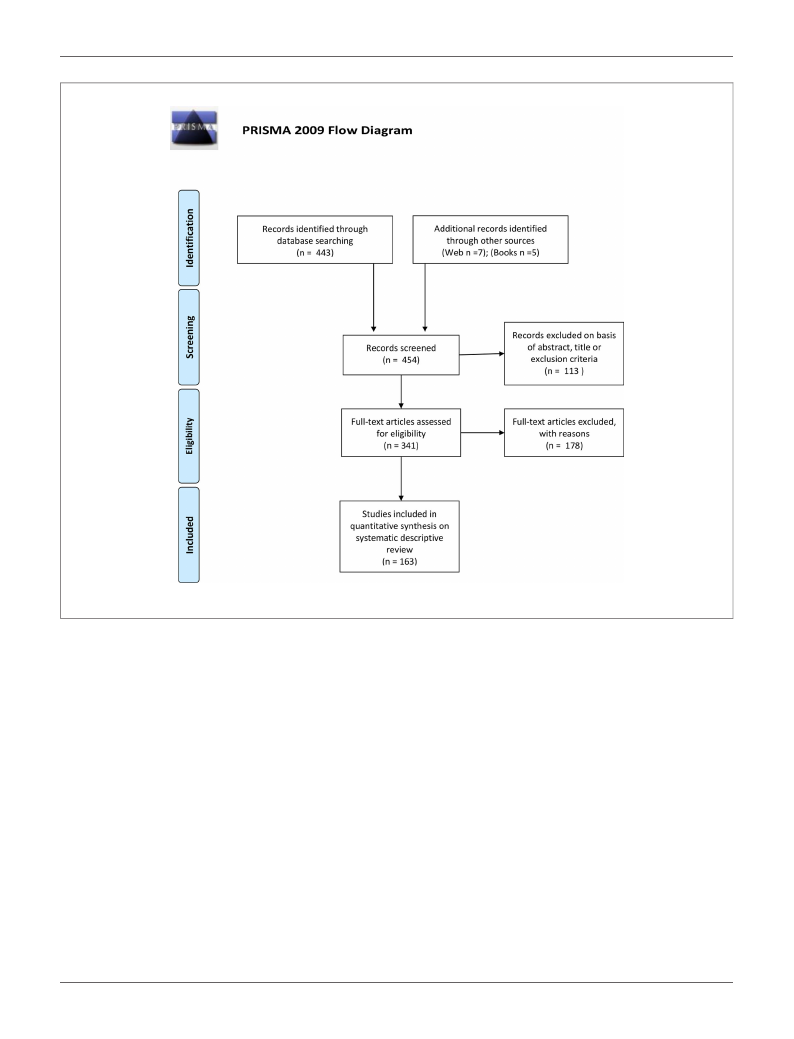

Methods: Literature available on PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane library until end of

June 2019 were reviewed. The total number of articles and association reports was 445.

From these, 163 were selected. We looked for the association between classical

psychiatric disorders such as anxiety schizophrenia, mood disorder and depression,

suicide, aggressive behaviors, despair for the loss of usual landscape, and phenomena

related to climate change and extreme weather. Review of literature was then divided into

specific areas: the course of change in mental health, temperature, water, air pollution,

drought, as well as the exposure of certain groups and critical psychological adaptations.

Results: Climate change has an impact on a large part of the population, in different

geographical areas and with different types of threats to public health. However, the delay

in studies on climate change and mental health consequences is an important aspect.

Lack of literature is perhaps due to the complexity and novelty of this issue. It has been

shown that climate change acts on mental health with different timing. The

phenomenology of the effects of climate change differs greatly—some mental disorders

are common and others more specific in relation to atypical climatic conditions. Moreover,

climate change also affects different population groups who are directly exposed and

more vulnerable in their geographical conditions, as well as a lack of access to resources,

information, and protection. Perhaps it is also worth underlining that in some papers the

connection between climatic events and mental disorders was described through the

introduction of new terms, coined only recently: ecoanxiety, ecoguilt, ecopsychology,

ecological grief, solastalgia, biospheric concern, etc.

Conclusions: The effects of climate change can be direct or indirect, short-term or long-

term. Acute events can act through mechanisms similar to that of traumatic stress, leading

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

1

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

to well-understood psychopathological patterns. In addition, the consequences of

exposure to extreme or prolonged weather-related events can also be delayed,

encompassing disorders such as posttraumatic stress, or even transmitted to later

generations.

Keywords: climate change, mental health, resilience, migration, vulnerability, climatic and economic turmoil,

extreme events

INTRODUCTION

Since the 1970’s scientists have been trying to understand

processes related to environmental factors that lead to climate

change. Our climate is changing, with an unequivocal regional

effect such as heath waves, floods, and droughts. Human

activities have altered the atmospheric composition, producing

a greenhouse effect leading to global warming. These activities

produce a flux of complex variance with setbacks related also to

mental health (1). Scientists argue that they still have to

understand what kind of transformations can be expected

depending on the temperature, how pervasive theses

transformations will be in the various environments, when and

what points of no return can be identified, which short and long-

term consequences may be foreseen, and who are the most

exposed biological subjects and most vulnerable societies. A

part of climate change is due to the conditions of the planet

that are independent of human activities (solar irradiance,

autonomous activity of the planet such volcanic eruptions).

Most studies are focus on the chain of events occurring in the

biosphere primarily due to global warming. Global warming is in

part attributable to the anthropogenic activity through the use of

fossil fuels, deforestation, and pollution (1).

Global warming is likely to cause widespread emergencies in

the future (2). These emergencies are real phenomena when

extreme climatic events have an impact on local territories. These

events are: extreme heat (increased global mean surface

temperature, heat waves); climate change–related water

disasters (CCRWDs) (sea level (3)—flooding, hurricanes, and

coastal storms); droughts; wildfires; winter storms, extreme

snow, and severe CAPE (convective available potential energy)

thunderstorms (4) (supercells, derechos, and tornados).

When can we consider a climatic event as “extreme”? In

science, the term “extreme” is used in several contexts. By

definition, “extremes” are events that are rare or outside the

normal range. A definition of extreme has been already deeply

discussed in Seneviratne et al. report (5). Devastating natural

weather phenomena are not exclusively caused by climate

change. Some seasonal change or annual means temperature

may be “extreme”. Therefore, extremes are understood within

the context in which they take place. People and communities

judge events as “extreme” by comparing them with personal

experiences, when these events are unprecedented or divergent

from previous phenomena (6). In the area affected by sudden and

extreme climatic events, it is not rare to hear from the elderly that

“nothing like this has ever happened”. However, focusing on a

single climatic extreme and extraordinarily event does not allow

to understand the bigger picture. Nonetheless, recently extremes

are becoming more evident, even when a longer time arc

is considered.

All weather events are affected by climate change. Higher

global temperatures and differences in humidity compared to

previous eras have been registered in recent years (6). There is

some degree of uncertainty regarding climate change and the

scientific community has not yet been able to fully link climate

change to the increase of extreme weather events (7). However,

many authors strongly believe extreme climatic events have

important influence on ecosystems and societies. Shifts and

trends of mean temperatures and precipitation have been

directly correlated to the increases of hurricanes, droughts,

heat waves, and heavy precipitation (8). Scholars have

confidence that the anthropogenic influence has contributed to

the increase of extreme events with disastrous outcomes on

global scale (9).

The Katowice Climate Change Conference, held in Poland at

the end of 2018, was the last conference concerning global

change in an effort to commit each state to reduce emissions,

trying to keep the global temperature change below 1.5°C. An

increase of average global temperature over 1.5°C has been

linked to a global rise in the frequency and intensity of

extreme weather events (10, 11). Moreover, the greenhouse

effect has already altered global climate dynamics (12). A vast

amount of information supports that anthropogenic activity is

responsible for extreme events, such as the heat waves in Europe

and Russia (13), and the devastating floods in Pakistan (14, 15).

Understanding how climate change relates to extreme events is a

current scientific challenge. There are different explanatory

experimental models (16). Each method must be able to

explain the consequences of human activity and how they are

linked to natural climatic variations.

Models on how global climate has evolved throughout the

eras can be useful in order to give a context to current extreme

events (17, 18). Such studies have increased over the past

decades. Historical models and earth surface temperature

readouts suggest that there is a strong connection between

anthropogenic warming and the increased persistence of

extreme weather (14). These approaches allow us to quantify

the influence of historical global warming on the probability and

the severity of individual events (19). All extreme climatic events

are associated with large scale changes in the thermodynamic

environments (12). For example, increases of mean temperature

lead to heat waves (20); decreases in ground humidity and higher

evaporation trends lead to higher incidence and severity of

droughts (21) or changes in soil-moisture (22); high sea

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

2

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

surface temperature and anomalies in humidity are linked to

storms and the melting of Arctic ice fields (23).

Statistical methods link extremes to an observed climatic trend.

This has proven to be challenging. The satellite era (1979–present)

coincides with a rapid increase of Arctic surface temperatures.

There is a high statistical confidence that links the anthropogenic

action to the current minimum extension reached by Arctic

glaciers, caused by the alteration of atmospheric circulation,

atmospheric humidity, and thermodynamic factors in general

(24). Authors strongly believe that some types of extreme event,

most notably heat waves and precipitation extremes, will increase as

an effect of the global warming (25). The frequency and the

intensity of extreme climate events are unprecedented in global

history (2). The debate is still open and, despite substantial

progresses, achieving an accurate analysis of local events,

evaluating all the involved thermodynamic processes, has proven

to be difficult (24). Some studies already suggest that a more

complex mechanisms may be involved in unprecedented

extremes climate events (25).

However, our climate does not act as a linear system (26), but

rather as a complex system (27), characterized by regime shifts,

oscillations, and chaotic fluctuations in all timescales (26), so that

predictions are impervious. Climate change will inevitably impose

alterations in our lifestyles and consequences in terms of human

losses and social readjustments. That said, it is not clear how many

people on the planet will be affected by extreme phenomena

caused by climate change, and to what extent and when these

phenomena will compromise the quality of their life. People could

be at risk for their survival, either directly (during, for example, an

extreme event) or indirectly (reduction of food, famine, water

scarcity, decrease in places to cultivate or hunt, displacement). In

order to advise societies on how to cope and adapt to these

phenomena, specialized international agencies have produced

reports on climate change and the extreme events suggesting

strategies and remedies (9, 28). Climatology, once a sub-field of

physical geography, has now grown in relevance throughout the

scientific community. Extreme events are the point of interaction

between climate change and the human world (29).

Moreover, our ecosystem will face plant and animal

extinction due to failure to adapt or migrate (30) leading to an

increased risk of an “extinction domino effect” (31). Climate

change can redistribute the strength of ecological interactions

between predator and prey (32). Moreover, effects of global

warming such as droughts and soil dry out (33) could have

amplified effect especially in rural areas (34) such as difficulties in

farming, starvation, forced migration (35); the consequent

overcrowding of coastal and delta areas could also lead to

physical illness by vector-borne disease. Global warming could

pose a risk to ecosystems with decreased biodiversity, modifying

fishing, and hunting activities (36). Famines can also be caused

by abnormal insects’ populations and consequent increased use

of pesticide or GMOs (37) with a change in biodiversity. Eighty

percent of global population is affected by water and food

insecurity due to climate change effects (38).

Environmental factors are becoming increasingly important

in psychiatry due to the fact that they can induce congenital

defects, impair neurodevelopment, even trigger endogenous

mental disorders as well arouse psychosomatic and

neurological disorders (39). Climate can produce strong

phenomena with a disastrous impact among human societies.

Disasters create a different kind of psychological and

psychopathological distress compared to normal seasonal

weather changes, as seen in tornados, floods, and droughts.

Furthermore, other climatic events, usually overlooked in

studies on mental health of exposed populations (e.g. ocean

acidification, acid rain, superfog (40), glacier melting, biomass

extinction), could also have a broader impact on mental health.

Psychiatry has only recently begun to deal with climate

change, albeit specific literature concerning the climate events

in relation to psychiatric disorders is still lacking and rather

undefined (41–43).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All papers available on PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane

published from 1996 until June 2019 were reviewed. Searched

terms included “PTSD” or “anxiety” or “depression” or “mental

health” or “psychiatric disorder” or “psychosis” or

“schizophrenia” or “suicide” or “mood disorder” combined

with “climate change” or “extreme events” or “disaster events”

or “surface air temperature” or “heath waves” or “rise

temperature” or “floods” or “flooding” or “increased waters” or

“hurricanes” or “tornado” or “drought” or “wildfires” or “vector

borne disease” or “deglaciation” or “deforestation” or “river

disappearance” or “increased of desert” or “extinction” or

“solastalgia” or “ecoanxiety” or “ecomigration” or “resilience”

or “adaptation”. The search included all languages and we focus

on articles written in English or Italian. Studies related to both

human and animal conditions were selected, including data

available from government and non-governmental

organizations, reports, and books.

Screening was made on the basis of abstract and title.

Exclusion criteria are:

• Even in the event that direct effect on mental health was

proven, articles on urbanization (n = 3), air and water

pollution (n = 66), chemical pollution (n = 7), and ionizing

radiation (n = 22) were excluded, insofar as they were not

directly related to the focus of our study.

• Articles dealing exclusively with transmission of infectious

diseases (n = 3) or physical-medical pathologies were

excluded.

The following articles was eligible for analysis based on their

specific topic. Exclusions (n = 178) were made in order to avoid

redundancy of cited material (Figure 1).

• 100 articles on climate change in general—34 articles were

selected;

• 18 articles on heat waves and temperature increase—six

articles on heat waves and seven on temperature increase

were selected;

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

3

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

FIGURE 1 | PRISMA flow diagram.

• 31 articles on flooding and sea-level increase—20 were

selected on flooding and 6 on sea-level increase;

• 20 articles on hurricanes—13 were included in this research;

• 10 articles on deforestation—seven were selected;

• 18 articles on drought—15 were selected;

• 25 articles on indigenous communities, vulnerability, and

migration—18 were selected;

• 23 articles on economic impact—two were selected;

• 16 articles on wildfires—10 articles were selected;

• 84 articles on psychiatric disorders connected with global

climate change—27 general articles were selected. Moreover,

28 association reports (WHO; IPCC; APA etc.) were studied

—15 reports were selected.

In each category, only pivotal studies included in the range of

the publication years were selected.

A total of 97 articles were analyzed, covering various extreme

weather events and their effects on psychiatric illness. We examined

7 reports and 28 reviews; among these, 3 were about communities, 1

about migrations; one studied event and consequences in 157

countries, one summarized the interviews performed on 105,549

patients. We analyzed 8 articles with regression time studies

(concerning 29 countries and data about surveys performed on

1,9 million citizens). Authors of 14 articles have given self-reported

questionnaires or surveys (range of scrutinized results went from 30

to 381,916 people in internet questionnaires). Nine articles reported

results from interviews, mainly about communities and children

studies, ranging from 14 to 342 people interviewed. One of the

selected articles is a population based retrospective study with 9

million data collected; one experimental study use statistic to

analyze 344,957 twitters, another analyzed 600 million social

media updates and reactions for a longitudinal and country scale

evidence study. Four of the selected articles were case-studies with

17 people interviewed and 1,526 questionnaires completed.

Excluding other minor selected categorized, other articles were

longitudinal or cross-sectional studies.

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

4

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

RESULTS

Course of Mental Health Changes

Following Extreme Events

A vast body of works on mental health and climate change is now

emerging (43, 44). Impacts on mental health can occur after or

even before an extreme event (45). Mental health outcomes of

climate change range from minimal stress and distress symptoms

to clinical disorders, ranging from anxiety and sleep disturbances

(46) to depression, post-traumatic stress, and suicidal thoughts

(10, 47). Other consequences might include the effect on

individuals and communities in their everyday life, perceptions,

and experiences, having to cope, understand, and respond

appropriately to climate change and its implications (10). A large

number of people exposed to climate or weather-related natural

disasters experience stress and serious mental health consequences.

Some natural disasters are possibly going to be more frequent

because of climate change. Notoriously, reactions to extreme events

that involve life disruption, such as loss of life, resources, social

support and social networks, or extensive relocation, are post-

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and general anxiety,

increased substance use or misuse, and suicidal thoughts (48).

Research has shown that peritraumatic experience is highly

related to acute stress during and immediately after a disaster,

which is expected to lead to the onset of PTSD (49). Later on, other

consequences come out for survivors, such as reduced daily life

activities and the loss of their “sense of place”. These conditions

could have an impact and exacerbate mental health risks. News

regarding climate change makes people uncertain and stressed, even

depressed and with a sense of powerlessness. The concrete impact of

those changes in life brings different types of psychopathological

reaction to these events. Briefly, acute impacts refer to all the

extreme events (e.g. floods, hurricanes, wildfires, etc.) that

immediately expose undefended and helpless people to mental

injuries. Subacute impacts involve intense emotions experienced

by people who indirectly witness the effects of climate change,

anxiety related to uncertainty about surviving of humans and other

species and, finally, sense of being blocked, disorientation, and

passivity. Long-term outcomes come in the form of large-scale social

and community effects outbreaking into forms of violence, struggle

over limited resources, displacement and forced migration (35, 50),

post-disaster adjustment, and chronic environmental stress (51). In

our study we considered the consequences for mental health for

each single extreme event. We also considered mental health

adaptation to environment changes.

Heat Waves

As a part of the Climate and Health Profile Report, both direct

and indirect impact on health with regard to extreme heat and

extreme precipitation were identified. Health risks caused by

these factors has significantly risen in recent years (52). Heat

weaves are spikes of high temperatures lasting some days that

range outside the normal temperature for a specific season (20).

This phenomenon is connected with climate change as they have

increased in frequency and intensity. Moreover, the frequency

and intensity of heat waves are considered extreme events linked

to climate change, with a regional effect.

Physical health, mental health, human well-being, and heat

waves appear to be specifically interconnected. Heat stress

directly caused by heat waves has been associated with mood

disorders, anxiety, and related consequences (53). People with

mental illness were three times more likely to run the risk of

death from a heat wave than those without mental illness (45).

During pregnancy, especially in the second and third trimester,

exposure to heat waves has been showed to be related to a lower

average birth weight and increase of incidence of preterm birth.

Effects during childhood and adulthood comprised reduced

schooling and economic activity, other than behavioral and

motor problems and reduced IQ (45). Some evidence seems to

hint a different vulnerability between genders. The percentage of

deaths were higher in women than men during the European

heat wave. Negative outcomes of heat waves are also related to

social factors. Women, young people, and people with low

socioeconomic status have shown to be more vulnerable to

anxiety and mood disorders related to disasters (54). Heat-

related illnesses and waterborne diseases are also connected

(52). It could also be noted that people are outside more

during the summer, and this could increase the opportunity

for conflicts. In hot temperatures, increase in discomfort leads to

increase feelings of hostility and aggressive thoughts and possibly

actions. Hotter cities were more violent than cooler cities. The

increase in heat-related violence are greater in hot summers and

showed increased rates in hotter years (55). Indeed, being

exposed to extreme heat can lead to physical and psychological

fatigue (53)—there is a clear association between warming

temperatures and rising suicide rates, especially in an early

summer ‘peak’ (56). Alcohol is likely to be involved in

increasing aggression. Higher temperatures than usual,

especially in June and July, were associated with an outbreak of

aggressive crimes. The co-occurrence of hot summer days and

weekends is therefore a perfect mix, resulting in a massive

increase in shootings (57). Preventive measures should be

taken against extreme temperatures to protect health, planning

targeted public health monitoring, expanding the availability of

air conditioning and providing countermeasures for what is

known as the “urban heat island” effect (52).

Water

Global warming will lead to CCRWDs such as an increase in

both intensity and global number of tropical cyclones (58, 59),

frequency and severity of hurricanes, and flooding (60).

Floods

Floods are an overflow of water, usually from the ocean, submerging

land areas. Flooding is one of the most frequent types of major

disaster, leading to 53,000 deaths in the past decade (61). CCRWDs

generate flooding in urban areas on the coasts, like those in Asian

deltas rivers (62, 63). These events could potentially have a negative

effect on the health of vulnerable populations. Moreover, CCRWDs

have a devastating impact on communities and the health of

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

5

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

residents, for example by exposing people to toxins, precipitating

population susceptibility, and creating crises for healthcare

infrastructures (60). There are direct impacts in terms of

morbidity and mortality related to water (such as drowning,

electrocution, cardiovascular events, nonfatal injuries, and

exacerbation of chronic illness); waterborne diseases (due to

contamination of drinking water); infectious diseases (64); and

psychiatric and mental health disorders. The principal effect after

flooding seems to be located in the mental health area, leading

especially to PTSD. A direct correlation between the intensity of the

disaster and the severity of the mental health effects was noted (65).

After the acute emergency phase, a number of members of the

affected populations are subjected to some level of psychological

distress and mental health problems (61). As studied all around the

world (i.e. India and Bangladesh (61); Dakota USA (66); Italy (67);

Venezuela (68) etc.) floods bring mourning, displacement, and

psychosocial stress due to loss of lives and belongings, as a direct

outcome of the disaster or of its consequences. All these are risk

factors for PTSD, depression, and anxiety (69). With specific

reference to flood victims, 20% had been diagnosed with

depression, 28.3% with anxiety and 36% with PTSD (70).

Consequences are still present well after the flood is over, due to

the presence of mourning, economic problems, and behavioral

problems in children (71, 72). Moreover, some cases show an

increase in substance abuse, domestic violence, as the calamity

exacerbates and precipitates previous existing people’s mental health

problems (70, 73–75). Contradictory evidence was obtained

regarding suicide following a flooding. In addiction there are

aspects of vulnerability such as poverty (60, 76), living in

makeshift housing solutions, and the lack of access to healthcare.

Flooding disrupts infrastructure, causing problems for the standard

systems of care, including mental health care that could assist and

mitigate the psychological outcome for victims. Other susceptibility

factors for mental illness related to these events include: women, the

young or elderly age, having a disability, being part of an ethnic or

linguistic minority, living in a household with a female head and

having lower level of schooling. Among residents and relief workers,

having limited resources or living in lower income countries are

additional risk factors (77). The disaster can only exacerbate any

existing barriers in the access of mental health care in the population

(78). The focus of many articles is on PTSD occurring immediately

after the disaster, when vulnerable people are more at risk and

fragile (61). This part of the population can develop mental health

problems and mental disorders in the short-, medium- or long-term

(78). In addition, even families not residing nearby the affected area

shown high levels of post-traumatic stress, due to the fact that they

still bear the charge of the disruption of community cohesion (76).

People who are affected by flooding could show remarkable

resilience, however they still need organizations to support them,

in order to recognize and cope with the distress, while also

providing assistance to avoid any possible additional mental

health problem or disorder arising from the situation.

Psychosocial resilience, due to its personal and collective

components, makes it fundamental to mitigate the distress of

flooding together with the social and health risks caused by the

event. Restoring social cohesion of communities and families

immediately after calamities is crucial in order to reduce suffering

and promote effective recovery (73). Community resilience also has

a preventive effect, as it prepares the population for future events

while also helping them to cope with the current situation (76).

Air

Tornadoes, hurricanes, and storms have all increased in

intensity, frequency, and duration over recent decades. Data on

tornadoes and mental health issues came from the latest kind of

this disasters, such as hurricane Katrina in Florida and Louisiana

in 2005 and Sandy in 2012 in Cuba, Jamaica, and Haiti (79–81).

There is still uncertainty regarding how much humanity is at

fault for this increase (82). Based on information provided by the

United Nations Development Program, nations like the United

States, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand and other twenty-nine

developing nations have been greatly exposed to hurricanes,

cyclones, and typhoons (83). The damage suffered by health

care infrastructure and the interruption of public health service

due to hurricanes leads to an increase in serious illness, injuries,

disability, and death (84). As in extreme events, there are health

issues that emerged or worsened after hurricanes due to

psychological stress: increase in rates of cardiovascular diseases

(85), prenatal maternal stress and depression, infants more likely

to experience anxiety, fear and sadness, and less responsive to

pleasant stimuli (86), lack of insurance possibly increasing

chronic illnesses with no access to medical care during a

disaster (87, 88), population exposures to contaminated

floodwaters (88). Many people experienced PTSD, stress,

depression, anxiety (87), and suicide (79). Consequences of

material damages lead to substance abuse (45, 89). The

incidence of PTSD, that has been studied most extensively, was

consistently associated with several factors. Severity of exposure

and previous mental health problems has shown to be stable

predictors of development of distress (84). Other vulnerability

factors are represented by: age, women, low education level, low

socioeconomic status, being unemployed or disabled before

hurricane disaster, and being single (54). People living in an

affected area showed high levels of suicide and suicidal ideation,

one in six people developed PTSD, and half of them developed an

anxiety or mood disorder, including depression (45). Additional

consequences are the loss of social support, job insecurity, and

loss of belongings, as well as disruption of medical health system,

displacement, and relocation are related to the onset of

psychological distress. Mental health disorders are often seen

even one year after the disaster or event (90). A strategy for

coping immediately after a hurricane is a successful evacuation of

vulnerable areas by reducing the number of victims.

Displacement to shelters often results in separation from social

support networks and creates a disruption in normal

psychological processes, particularly familiarity, attachment

and identity, and decrease in perceived social support in the

months following the hurricane, which in turn has been shown

to be associated with increased symptoms of general

psychological distress. Being moved from one shelter to

another is traumatic, compounded by the limited amount of

healthcare services (91).

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

6

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

Drought

Historically, a natural drought lasts about a decade. Due to

climate change, there will be droughts lasting around three

decades, also known as “megadroughts”. From a current

historical frequency of 12%, these events may increase up to

60% (92) due to possible changes in future anthropogenic

greenhouse gas emissions and atmospheric concentrations

measured in CO2-equivalents (93). A combination of high

temperatures and low precipitation increases the frequency of

drought over the world (94). A temperature fluctuation is

correlated with agricultural loss by affecting crop productivity

and yields. This loss is linked to a decrease on economic growth

leading to a long-term economic disadvantage and promoting

political instability and conflicts (95). Farmers all over the world

are more vulnerable to environment-induced mental health risks

carried by drought. Long-term droughts and erratic rain fall have

been associated with deterioration of economic conditions,

reduced social functioning, and psychological distance to

perception of negative climatic conditions (96). The regulation

and adjustment of emotion is disrupted by depression,

demoralization, fatalism, passively resigning to fate, especially

in women and adolescents or people with lower socioeconomic

status, showing feelings of distress and helplessness (52, 53).

Drought has been often connected to suicide (97–101), especially

in older people (102). In semi-arid and peri-urban areas,

adaptive capacity is necessary to cope with an increased

temperature and a reduced rainfall. In this case, vulnerability is

seen as the degree to which people are susceptible by events that

disrupt their lives—events that are beyond their control. Resilient

systems cope with extreme events in order to create a response

that maintains essential function, identity, and structure, and the

capacity for adaptation. Consequently, local communities

strongly perceive the impact of climate change. Negative events

stimulate feelings of alertness, constant monitoring of current

and future events, mental distress, anxiety, depression, and

suicide (103), as well as prolonged emotional stress, inevitably

provoking high job insecurity (51) and other psychological

issues (104).

Drought and migration are related through an assessment of

crop yields (105). The landscape changes with periodical drought

impact for example on the Turkana’s ability to gain access food,

water, health, and security. These indigenous people are farmers

that have grown dramatically in number in the last decades with

a majority living below the poverty line. Prolonged and more

frequent droughts and unpredictable rainy seasons have

exacerbated the difficult access to potable water or food.

Consequently, changes in water availability, temperature or

other environmental variables can have a truly devastating

impact on their daily life. Many extreme weather events and

famine lead to displacement of entire communities and forced

migration, within and outside national borders, with onset on

conflicts over natural resources (106). In northern Ghana’s

savanna (an arid zone with severe droughts), climate change

exposes farmers to adverse climatic conditions that include low

rainfall, forest fires, soil erosion, loss of soil fertility, poor harvest,

and destruction of property and livestock. In this region, farmers

with small plots are at a higher risk of suffering acute, sub-acute,

and long-term problems caused by extreme climate change (51).

Wildfires

The term “wildfire” refers to large-scale fires, generally occurring

in forests and jungles. These phenomena have involved Siberia,

Central Africa, and the Amazon in the present times. The areas

affected by the wildfire may be sparsely populated or nearby the

city boundaries. The greatest concerns are those related to the

climate. The effects on the ecosystem are devastating, as a forest’s

carbon dioxide storage capacity is forever lost (107). Once burnt,

forest tend to become savannah, scarcely covered by deciduous

trees or cultivation. Vast decline of forests will have

reverberations for the world’s climate, as anticipated by many

government administrations and institutions all over the world.

A “business as usual” scenario will lead to a rise in temperature of

about 4 degrees Celsius by 2100 and plants will have to find new

strategies to survive.

In the past, a more local phenomenon has been described as

bush-fire. These involved urban areas in proximity with

bushlands or forests and could affect residential

neighborhoods, suburbs or slums in different ways, albeit

devastating for farmers and people in the area. Firestorms

generated by bush-fires led to destruction and evacuation of

residents. Wildfires have a heterogeneous impact on property

damage, physical injuries, and mental health (108). During the

years following the disaster, an increase of mental health issues

was observed, such as general mental health problems, post

traumatic disorders (109), psychosomatic illness, and alcohol

abuse (110). Effects can be delayed in onset and can persist over

at least several years. Proximal populations, not directly affected

by the bush-fires, can also be involved (111). Studies performed

in areas hit by Australian bush-fires observed that a year after the

events 42% of the population exposed was classified as potential

psychiatric cases (109). Californian wildfires also offer a rather

dramatic picture, with 33% showing symptoms of major

depression and 24% showing symptoms of PTSD. A similar

effect was observed in Greek wildfires (112), with an increased

somatization symptoms, depression, anxiety, hostility, and

paranoia (113). Post-disaster mental health issues observed

were PTSD, physiological hyperarousal, chronic dissociation,

sadness and depression, detachment (114) disorganized

thinking and behavior, numbing or avoidance, poor

concentration, and behavioral problems. In the youth

population, connections have been found between the young

age and the experience of personal life threat (115). Children

were also affected by bush-fires, showing posttraumatic

phenomena such as anxiety disorders and panic attacks,

problems sleeping, acute stress disorder, compulsively

repetitive play, flashbacks, and psychotic disorders (116).

Wildfires could become quite frequent with climate change.

Addressing such phenomena on a global scale will prove

challenging. It is also difficult to predict how populations will

react once the anthropogenic role of this type of event takes hold.

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

7

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

Long-Term Environment Changes

and Critical Psychological Adaptations

Climate change leads to extreme events that bring an immediate

and direct impact on the population in terms of mental health.

However, changes also occur slowly, as in the case of temperature

increase. Climate change will also modify the representation of

territories as historically and traditionally known and lived by the

populations. This loss of spatial and cultural parameters is not

favorable to the people’s life in terms of changes of lifestyle that they

might undergo. People may also become less familiar with places

and usual products (resources) of the environment. Landscape

changes are brought about by deforestation, deglaciation, river

disappearance, desertification, water shortage, increase of

infectious diseases, and biomass extinction. On its own,

desertification (117) may cause resource-based conflicts (106).

Increase of Average Land Surface Air Temperature

The earth could become very hot due to the anthropogenic effect

of greenhouse gases that alters the dynamics of CO2. Moreover,

recent studies have highlighted how climate change and global

warming are nonlinear trends (118).

The increase in environmental temperature can notoriously

compromise the functioning of the central nervous system,

similar to insolation and heat stroke. The correct temperature

for proper functioning is around 22°C (119). Outside

temperature can affect the risk of onset or continuous mental

disorders in different ways. For example, temperature stress can

influence psycho-physiological functions by directly affecting

bio-chemicals levels, (e.g. altering the production of serotonin

and dopamine) (120) or by disrupting the homeostasis of

thermoregulation (121, 122). Additionally, direct heat could

result in sleep disturbance, exhaustion, and heat stress

associated with suicide (56, 123). Moreover, the correlation

between mental illness and increase of temperature depends on

latitude and factors that go beyond geography, such as cultural,

political, and socio-behavioral factors (120). In the tropics,

temperature fluctuations show a clear connection to negative

agricultural, economic, and political situations. This is clearly

seen in poor countries, which are more vulnerable to weather

and climate fluctuation than wealthier countries (95). As

described above, a single disaster, like a hurricane or flooding,

has profound effects on mental health, in direct and acute

manners. Furthermore, heat waves and extremely high

temperatures expose the population to the possible onset of

mental disorders. Sensitivity of mental disorders to temperature

should not be underestimated when compared to other heat-

related physical diseases that are commonly studied. Naturally,

the levels of exposure to high temperatures can vary, affecting

populations in different geographical areas, thus leading to

greater challenges in the study of risks (120). Studies show higher

risks of mental-disorder correlated to warmer temperatures,

specifically mania in the elderly, as well as a positive association

with transient mental disorders and episodic mood disorders and an

increase in hospital admissions for mental illness within a few days

after warmer temperatures. When temperature rose over a

threshold of about 20°C, there is an increase in drug-related

mental disorders. Furthermore, there is also a correlation with

increased mortality and morbidity risks among people with

mental and behavioral disorders (120). Increases in hospital

emergency room visits are also shown for many of mental

illnesses such as mood disorders (124), substance abuse, behavior

disorders, neurotic disorders, and schizophrenia and schizotypal

disorders. People are more affected by high temperature especially if

they have schizophrenia, schizotypal disorders, and mood disorders

(121). During the increase of temperature, there is a risk of mental

states of aggression resulting in violence and self-harm, inflicted

injury/homicide, and self-injury/suicide (122). Many studies found

no significant associations with cold temperatures (51, 120).

Increase in Sea Level

Global sea level is projected to rise between 30 to 121 centimeters

by 2100, due to the influx of water from melting glaciers and the

expansion of seawater as it warms (125). There are many factors

that contribute to the increase of water (melting glaciers

specifically in Greenland and Antarctic as well as worldwide),

as well as changes in rainfall patterns and increasing frequency of

severe weather such as flooding (126–129). Countries with low-

lying areas, small islands like those in the Indian or Pacific

Oceans, are concerned that their land areas might decrease due

to flooding and coastal erosion. Consequently, many people

could be forced to migrate to other countries leading a

persistent worry and thoughts of relocation (128). Specific fears

of encirclement or siege by the sea would replace the population’s

normal relationship with the sea or ocean (130).

Deforestation

Deforestation occurs due to the loss of plant biomass caused by

climatic events and the direct action of mankind, driven by

agriculture, animal grazing, and mining (131). There has been an

enormous loss of forests due to human activity. News regarding

such events have a stressogenic impact on western populations,

due to the increased ecological awareness. People believe that an

important world heritage has been damaged and lost. This

feeling is now known as a biospheric concern. On the other

hand, for indigenous populations, deforestation has a deeper

impact, leading to profound maladaptive disorders and

depression. In general, people believe that forests are a source

of health and protection from various types of stress (132).

Urban green areas help maintain low temperatures in the city

during the summer months, improve air quality, and reduce

people’s stress level (133). An ever-increasing number of studies

shown that living in green urban spaces leads to health benefits,

including better physical and mental health and a longer life

expectancy (134). Studies suggest that the positive influence of

nature on health can be observe especially between vulnerable

groups such as the elderly, those in rehabilitation for mental

disorders, and individuals in crisis rehabilitation (135). In the

older population, contact with parks and green areas has been

linked with slower cognitive decline. Moreover, children benefit

from living in greener urban areas, such as better spatial working

memory, improved attentional control and capacity, and higher

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

8

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

academic achievement, particularly in mathematics (136), as well

as improved behavior and emotional development, and positive

structural changes in the brain (134). Moreover, green areas and

parks in childhood have a preventive effect on the risk of

developing various mental disorders later in life. More

greenery in urban areas creates higher social cohesion and

increases people’s physical activity level, therefore improving

children’s cognitive development (137). In general, subjects

living more urban green areas have a better quality of life.

Unfortunately, those people who could get more benefits from

a change of exposure often do not have sufficient resources or

capacity to move to more healthy environments (138).

Landscape modification: landscape modification can induce

individuals to develop a profound sense of loss of connection and

detachment from the environment they know. Solastalgia is a

term that describes this type of loss, especially when a person

finds it difficult to adapt to environmental changes, possibly

creating risks for mental health (53). Solastalgia describes a

complex phenomenon that can have an impact on

psychological levels, similar to that experienced by people who

are forced to migrate (139). Biospheric concern refers to a type of

stress that people feel when they see vulnerable nature such as

plants or animals and the environment (140). Daily life can

undergo variation due to climate change and when people lose

their autonomy and control, they could experience a deep

psychological change. For example, the loss of employment

related to environmental changes can lead to a loss of

individual identity. Immediately after a disaster, damages on

social or community sources, or lack on food and medical

services, could results in many acute consequences for the

psychological well-being (139). In contrast, slow change of the

environment due to climate change, like changes in usual

weather or rising sea levels, will cause acute and chronic

psychopathologic trauma and shock, PTSD, depression,

anxiety, suicide, substance or alcohol abuse, aggressiveness and

violence, difficulties in social and interpersonal relationships, loss

of personally important places, alteration of social ties, loss of

autonomy, and control, as well as personal and professional

identity, leading to the emergence of feelings of helplessness and

fear, solastalgia, and eco-anxiety (45).

Economic Impact

After ecological and environmental changes in a country,

economic crises can occur and lead to an increase in suicide

rates and other mental and behavioral disturbances especially

working men (141). This type of stress, when associated with low

socioeconomic status, paired with limited access to resources and

reduced health, can lead to a diminished ability to cope.

Economic difficulties that last over time or in conjunction with

other factors, lead to a physical, cognitive, psychological, and

social malfunction with a decrease in well-being and health

(142). Both economic and climatic variables are strongly

correlated with suicide, with 62.4% of male and 41.7% of

female suicide rate variability across the continent (141).

Exposure Groups

Certain people are indeed more vulnerable to the potential

impacts of climate change on mental health. There are

communities that are more vulnerable to such events. This

impact implies psychological effects (45) especially in

vulnerable groups like children, the elderly, the chronically ill,

people with mobility impairments, pregnant and postpartum

women, people with mental illness, and those with lower

socioeconomic status. Consequently, climate change has

worsened global economic inequality (143). The more

temperature shifts from optimum levels, the more there will be

groups that cannot cope. A striking example is the traditional

native populations. Different studies have considered the effect of

climate change on native communities (such as first nations and

aborigines), highlighting aspects of vulnerability and resilience

(144, 145). Among these populations, the elderly is a clear

example of difficulty in re-adaptation. These minorities and at-

risk groups, such as the Inuit communities, first nations, and

aborigines (146), are experiencing rapid change in climatic

conditions (132, 147, 148). In the Canadian arctic, the Inuit

refer to having a protective factor for their mental health and

well-being in “being on the land”. Melting ice and change in

weather conditions are strongly linked to the impairment of

these protective factors due to a decrease in access to land with

some of the highest rates of youth suicide that have been

documented among Inuit youth (149).

Climate change is a social determinant for mental health

(150). Strong impact has been noted on refugees and migrants

(151), ethnic minorities, the homeless or vulnerable populations

such as the poor in countries like India, China, and Brazil (152).

Women, those with low socioeconomic status, living in poverty,

with scarce economic and social resources, reduction of social

support, and mental health problems existing before the events,

along with traumatic experiences (death or life risk, serious

injury or sexual assault) and stressors, represent vulnerable

groups that tend to develop new mental disorders or see their

previous problems worsen (49). After climate disasters, children

typically show more severe disturbances than adults, with more

severity and prevalence with regard to the onset of PTSD and

depression. (71).

Residential populations in changing territories are subjected to

new environmental conditions. For these people, this violation of

the usual context is experienced with passivity and a sense of

powerlessness. Many studies show that when people experience

feelings of loss, helplessness, and frustration caused by their inability

to cope with climate change, a term today coined as ecoanxiety (45,

153). People may also experience feelings of uncertainty and

anticipation of the unknown regarding climate change. This leads

to a psychological distance, a perception of distance, when a climatic

event occurs as near or far, at a temporal, spatial, and s ocial level

(51). In response to growing ecoanxiety and various type of

biospheric concern, psychotherapists are pioneering a new field of

treatment, termed “ecopsychology”. It is important for doctors to

teach patients to accept their own powerlessness. For example, when

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

9

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

it starts raining, some patients have episodes of anxiety because they

think of the past flooding with fear of losing the house again due to

the flood. “Ecological grief” is a recorded grief and anxiety spread

among the native Inuit to describe what they have seen (154).

These new words are emerging from recent observations on

the impact and power that climate change has on mental health.

It will certainly take time and further studies in order to identify

these new diseases and disorders. The DSM-5 and ICD-10 offer

no specific references to mental disorders related to climate

change. The chapter “Other conditions that may be a focus of

clinical attention” in the DSM-5 contains the section “Economic

Problems” where the following conditions are listed: lack of

adequate food or safe drinking water, extreme poverty, low

income, insufficient social insurance, or welfare support. In the

section “Problems Related to other Psychosocial, Personal and

Environmental Circumstances” the following conditions are

listed: exposure to disaster, war, or other hostilities (155).

Certain groups and communities are now beginning to

experience disruptions with regard to social, economic, and

environmental determinants. When exposed to climate change,

a population experiences constant uncertainty, anxiety, loss,

disruption, displacement, and fear even before a disaster has

even occurred. Climate change negatively impact on mental

health and wellbeing with unequal distribution within and

among communities (156). After a natural disaster has

occurred, damage and efforts to repair it have increased the

disparity of wealth between races (this has been shown in United

States). There has been a clear-cut increase with regard to

inequality in countries that are frequently hit by extreme

events. When certain areas receive more redevelopment aid,

racial inequality is going to be amplified (157). When farmers

in various parts of the world perceive the psychological pressure

of climate change, they are motivated to engage in different

strategies in order to adapt to climate change (51).

DISCUSSION

Summary of Main Findings

There is a strong link between natural disasters and mental

disorders. In the future, climate change will bring about an

increasing frequency of extreme weather. We know that

weather changes may induce psychopathological phenomena

such as seasonal affective disorders to weather sensitivity and

meteoropathic conditions. Specific symptom patterns, below the

pathological threshold, may be devised in reaction to various

atmospheric changes and perturbations: temperature, humidity,

rain, barometric pressure, brightness, rate of air flow, air

ionization, thunderstorms, and sudden shifts of some of these

factors (158). What is also seen as a temperamental trait has been

called “meteorosensitivity”. Living organisms may be biologically

more prone to suffer the effect of atmospheric events on mind

and body. On the other hand, meteoropathic subjects are those

individuals who develop a specific illness or the worsening of an

existing disease as a consequence of climatic changes. Psycho-

physical symptoms include: mood disturbances, irritability,

anxiety, mental and physical weakness, hypertension,

headache, hyperalgesia and pains, and autonomic symptoms

(159). Moreover, air pollution can induce neural instability

(158). Scarce rain and low average temperature have been

found to lead to psychiatric visits in emergency departments

(160). Hippocrates himself wrote: “Whoever wishes to

investigate medicine properly, should proceed a so: in the first

place to consider the seasons of the year … then the winds, the

hot and the old … we must also consider the qualities of the

water …” (161). Weather can impact everyday activity and

changes in the behavior result from physical characteristics of

the environment. With global climate change, these

psychopathological phenomena due to sensitivity to normal

weather conditions can today be studied within a

wider dimension.

Climate change can lead to extreme weather, which include

large storms, flooding, droughts, and heat waves, and it has

effects not only on physical health (e.g. degraded air quality)

through the spread of diseases and the reemergence of existing

diseases, but also on mental health. Mental health consequences

of natural disasters cover a wide range of disorders.

The connection between climate change and its consequences

on mental health is far from reaching a clear conclusion. The

complexity of current studies highlights this challenge. This

difficulty is largely due to the heterogeneity in what to measure

and how to measure the impact of climate change. Attempts to

discover the underlying mechanisms of adaptation, as well as the

definition of deviations from normality in extreme climate

events, and finally attempts to define direct cause-effect

relationships are all challenging tasks. Socio-behavioral factors,

culture, information, and preparedness all play a relevant role in

peri-traumatic experience, determining collective resilience or

psychological disruption and exhaustion. Studies that empirically

established connections between climate change and mental

health consequences are now coming forth in literature.

Impact of climate change on mental health can occur either

directly with immediate effect (heat waves), or indirectly in the

short term during extreme events (floods, tornadoes, hurricanes),

or indirectly in the long term (changes in the territory such as

prolonged droughts, increase in the sea levels, deforestation,

forced migration). All these events affect the mental health of a

population, with the appearance of psychiatric conditions such

as PTSD, mood disorders such as depression, anxiety, increased

suicide rate and substance use, as well as increased aggressive

behavior. Climate change will also exert the greatest impact on

groups of vulnerable populations that therefore have an

increased probability of developing psychopathologies: women,

the elderly, children, people with previous psychiatric illnesses

who can consequently worsen their mental condition, and people

with low income or poor social network, as well as indigenous

and native communities. Extreme weather events seem to have

the power to also destroy social ties (162). Vulnerable

communities are those located in exposed regions (e.g. coastal

regions, where windstorm or extreme heat can occur).

Climate change will produce profound changes in the

environment and alter lifestyles, while also generating

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

10

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

environmentally-motivated migration (random asylum seekers

and climatic refugees). These groups of people, forced to migrate,

already have their own psychological vulnerabilities (162). They

may find it difficult even to identify the appropriate emotional

control for specific climate changes. Moreover, extreme events

produce different types of psychopathological reactions over

time, as there are acute, sub-acute, and long-term impacts on

mental health. Mental adaptation and certain behavioral patterns

will develop following the chronology of events: in the pre-alert

phase, during the disaster and after the event (163). Long-term

consequences are difficult to define. Consequences of climate

change, such as economic and social difficulty, contribute not

only to the increase in the incidence of mental illnesses in the

affected population, but also in the subsequent generations.

Literature analyzes single types of climatic events, since certain

consequent disorders are specific while others generally occur in

different extreme events (162). Being able to understand what

this change entails makes it possible to program early

interventions and actions for a population’s mental health.

Limitations

Studies on the consequences that climate change has on mental

health are still at their very beginning. In the future, it would be

useful to further investigate the correlation between psychiatric

diseases and extreme events. We did not find any study on how

people react to the changes in landscape such as deglaciation,

disappearance of rivers, desertification, fires, and water

shortages. A greater understanding of the characteristics of

acute, sub-acute, and long-term consequences is an also

desirable goal. Furthermore, we believe that future research in

climate change and mental health will include multi-disciplinary

studies. Scholars should focus on how different vulnerable

groups can be affected by natural disasters and climate change,

as well as how to make use of the available protective measure

and healthcare resources. A limitation of the present descriptive

review is the lack of a meta-analysis as a methodological

completion of the systematic review. This could be useful in

the upcoming research in order to establish specific causal

associations between climate change and mental health

consequences (symptoms and disorders).

Conclusions

Based on the studies and literature reviewed in this paper, there

appears to be strong evidence of the influence that the climate

change exerts on mental health.

This study examined the effects of global climate change on the

general population, as well as at-risk groups and vulnerable

communities. We chose to focus on extreme events, such as

those produced by temperature increase, heat waves, floods,

drought, tornadoes, hurricanes, and wildfire. Consequences have

been described in terms of distress symptoms, suicide rates, and

clinical disorders (depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, PTSD,

etc.). Even though some of these events may occur in a slower and

less acute manner (e.g. temperature increase or droughts), most of

these events are rapid in their onset and manifest themselves in the

form of disasters, the reactions to which often see PTSD as a

prototypical model. On the other hand, we could support that

people who are more sensitive to weather and atmospheric

phenomena may be more affected by gradually occurring global

climate changes and their consequences, such as global warming,

rising sea levels, landscape changes, and loss of familiar

environmental landmarks.

Moreover, the disappearance of animal and plant species may

bring about feelings of hopelessness and depression. When a

person’s feelings about their environment are considered, it

should be clear that we are moving toward a cultural and

contextual dimension. The wound inflicted to this symbolic

domain causes more complex psychopathological

consequences, such as identity disorders (164) or long-term

personality changes (119), as seen in trauma related to extreme

weather events and loss of familiar landscape, or dissociative

syndromes (165) as seen in trauma related to extreme events or

in migratory syndromes. Lastly, we also need to learn how

meteoropathy and weather sensitivity, paired with

environmental and climate changes, deeply influence the

psychosomatic sphere of mankind, activating mechanisms of

somatization and conversion, and inducing somatic disorders

and physical illnesses or worsening previously existing distress at

the body level. These psychiatric disorders, in quality and

quantity, are linked to the type of evolution of post-modern

societies. In short, all of these issues need to be more extensively

studied and clinical experience should be gained in order to

support our provisional conclusions. The challenge of climate

change will be protracted in the upcoming years. Therefore, this

branch of “ecopsychiatry” will surely be supported by new data

sets and further studies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

PC, SB, and LJ all contributed to the brainstorming, writing, and

critical review of this manuscript. LJ edited the manuscript.

FUNDING

Funding for this study was provided by Fondazione Policlinico

Gemelli - Institute of Psychiatry, Catholic University, Rome, Italy.

The funders had no role in this study design, data collection and

analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the World Psychiatric Association,

Section on Ecology Psychiatry & Mental Health for the

scientific support.

Frontiers in Psychiatry | www.frontiersin.org

11

March 2020 | Volume 11 | Article 74

Cianconi et al.

Climate Change and Mental Health

REFERENCES

1. Cianconi P, Tarricone I, Ventriglio A, De Rosa C, Fiorillo A, Saito T, et al.

Psychopathology in postmodern societies. J Psychopathol (2015) 21:431–9.

2. Diffenbaugh NS, Scherer M. Observational and model evidence of global

emergence of permanent, unprecedented heat in the 20(th) and 21(st)

centuries. Clim Change (2011) 107:615–24. doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0112-y

3. Church JA, Clark PU, Cazenave A, Gregory JM, Jevrejeva S, Levermann A,

et al. 2013: Sea Level Change. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science

Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom

and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press (2013).

4. NASA Global climate change. Severe thunderstorms and climate change. .

[Online] April 7, 2013. [Cited: May 26, 2019.] https://climate.nasa.gov/news/

897/severe-thunderstorms-and-climate-change/.

5. Seneviratne SI, Nicholls N, Easterling D, Goodess CM, Kanae S, Kossin J, et al.

Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical

environment. Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge

University Press (2012). A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of

the IPCC.

6. Trenberth KE. Framing the way to relate climate extremes to climate change.

Clim Change (2012) 115:283–90. doi: 10.1007/s10584-012-0441-5

7. Jentsch A, Kreyling J, Beierkuhnlein C. A new generation of climate change

experiments: events, not trends. Front In Ecol Environ (2007) 5:365–74. doi:

10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[365:ANGOCE]2.0.CO;2

8. Jentsch A, Beierkuhnlein C. Research frontiers in climate change: Effects of

extreme meteorological events on ecosystems. C R Geosci (2008) 340:624–8.

doi: 10.1016/j.crte.2008.07.002

9. IPCC. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance

Climate Change Adaptation. Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA:

Cambridge University Press (2012). A Special Report of Working Groups I

and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

10. WHO. Mental health action plan 2013-2020. Geneva: WHO Document

Production Services (2013).

11. Steffen W, Grinevald J, Crutzen P, Mcneill J. The Anthropocene: conceptual

and historical perspectives. R Soc (2011) 369:842–67. doi: 10.1098/

rsta.2010.0327

12. Trenberth KE, Fasullo JT, Shepherd TG. Attribution of climate extreme

events. Nat Clim Change (2015) 5:725–30. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2657

13. Christidis N, Jones GS, Stott PA. Dramatically increasing chance of

extremely hot summers since the 2003 European heatwave. Nat Clim

Change (2014) 5:46–50. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2468

14. Mann ME, Rahmstorf S, Kornhuber K, Steinman BA, Miller SK, Coumou D.

Influence of Anthropogenic Climate Change on Planetary Wave Resonance

and Extreme Weather Events. Sci Rep (2017) 7:45242. doi: 10.1038/

srep45242

15. Petoukhov V, Rahmstorf S, Petri S, Schellnhuber HJ. Quasiresonant

amplification of planetary waves and recent Northern Hemisphere weather

extremes. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2013) 110:5336–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222000110

16. Berry HL, Waite TD, Dear KB, Capon AG, Murray V. The case for systems

thinking about climate change and mental health. Nat Clim Change (2018)

8:282–90. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0102-4

17. Mimura N, Pulwarty RS, Duc DM, Elshinnawy I, Redsteer MH, Huang HQ, et al.

Adaptation planning and implementation. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts,

Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Cambridge,

UK, and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press (2014) Contribution

of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC.

18. Rosenzweig C, Karoly D, Vicarelli M, Neofotis P, Wu Q, Casassa G, et al.

Attributing physical and biological impacts to anthropogenic climate

change. Nature (2008) 453:353–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06937

19. Rahmstorf S, Coumou D. Increase of extreme events in a warming world.

Proc Natl Acad Sci (2011) 108:17905–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101766108

20. Meehl GA, Tebaldi C. More Intense, More Frequent, and Longer Lasting

Heat Waves in the 21st Century. Science (2004) 305:994–7. doi: 10.1126/

science.1098704

21. Dai A. Drought under global warming: a review. WIRES Clim Change (2011)

2:45–65. doi: 10.1002/wcc.81

22. Fischer EM, Seneviratne SI. Soil Moisture–Atmosphere Interactions during

the 2003 European Summer Heat Wave. J Climate (2007) 20:5081–99. doi:

10.1175/JCLI4288.1

23. Petrie RE, Shaffrey LC, Sutton RT. Atmospheric response in summer linked

to recent Arctic sea ice loss. Q J R Meteorol Soc (2015) 141:2070–6. doi:

10.1002/qj.2502

24. Diffenbaugh NS, Singh D, Mankin JS, Horton DE, Swain DL, Touma D, et al.

Quantifying the influence of global warming on unprecedented extreme

climate events. PNAS (2017) 114:4881–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618082114

25. Coumou D, Rahmstorf S. A decade of weather extremes. Nat Climate

Change (2012) 2:491–6. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1452

26. Scheffer M. Critical transitions in nature and society. New Jersey: Princepton

University Press (2009).

27. Rahmstorf S. Anthropogenic climate change: the risk of unpleasant

surprises. In: Brockmann KL, Stronzik M, editors. Flexible mechanisms for

an efficient climate policy (2000). p. 7–11.

28. IPCC. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge, United

Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press (2007)

Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

29. Peterson TC, Heim Jr. RR, Hirsch R, Kaiser DP, Brooks H, Diffenbaugh NS,

et al. Monitoring and understanding changes in heat waves, cold waves,

floods and droughts in the United States: State of knowledge. Bull Am

Meteorol Soc (2013) 94:821–34. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00066.1

30. Nogués-Bravo D, Rodríguez-Sánchez F, Orsini L, de Boer E, Jansson R,

Morlon H, et al. Cracking the Code of Biodiversity Responses to Past

Climate Change. Trend In Ecol Evol (2018) 33:765–76. doi: 10.1016/

j.tree.2018.07.005

31. Strona G, Bradshaw CJA. Co-extinctions annihilate planetary life during

extreme environmental change. Sci Rep (2018) 8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-

018-35068-1

32. Romero GQ, Gonçalves-Souza T, Kratina P, Marino NAC, Petry WK,

Sobral-Souza T, et al. Global predation pressure redistribution under

future climate change. Nat Climate Change (2018) 8:1087–91. doi:

10.1038/s41558

33. Humphrey V, Zscheischler J, Ciais P, Gudmundsson L, Sitch S, Seneviratne

SI. Sensitivity of atmospheric CO2 growth rate to observed changes in

terrestrial water storage. Nature (2018) 560:628–31. doi: 10.1038/s41586-

018-0424-4

34. OBrien LV, Berry HL, Coleman C, Hanigan IC. Drought as a mental health

exposure. Environ Res (2014) 131:181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.03.014

35. Abel GJ, Brottrager M, Cuaresma JC, Muttarak R. Climate, conflict and

forced migration. Global Environ Change (2019) 54:239–49. doi: 10.1016/

j.gloenvcha.2018.12.003

36. IPCC. Global warming of 1.5°C. Switzerland: Technical Support Unit (2018).

37. Deutsch CA, Tewksbury JJ, Tigchelaar M, Battisti DS, Merrill SC, Huey RB,

et al. Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science

(2018) 361:916–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aat3466

38. Climate Council. Climate Change, Security and Australia"s Defence Force.

Australia: Climate Council of Australia Limited (2015).

39. Loganovsky KN, Loganovskaja T, Marazziti D. Ecological psychiatry/

neuropsychiatry: is it the right time for its revival? Clin Neuropsychiatry

(2019) 16:124.

40. Bartolome C, Princevac M, Weise DR, Mahalingam S, Ghasemian M,

Venkatram A, et al. Laboratory and numerical modeling of the formation

of superfog from wildland fires. Fire Saf J (2019) 106:94–104. doi: 10.1016/

j.firesaf.2019.04.009

41. Wight J, Middleton J. Climate change: the greatest public health threat of the

century. BMJ (2019) 365:I2371. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2371

42. Silverman GS. Systematic Lack of Educational Preparation in Addressing

Climate Change as a Major Public Health Challenge. Am J Public Health

(2019) 109:242–243. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2018.304818

43. Bourque F, Willox AC. Climate change: The next challenge for public mental

health? Int Rev Psychiatry (2014) 26:415–22. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.925851

44. Berry HL, Bowen K, Kjellstrom T. Climate change and mental health: A

causal pathways framework. Int J Public Health (2010) 55:123–32. doi:

10.1007/s00038-009-0112-0