Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-019-0800-1

(2019) 24:46

Environmental Health and

Preventive Medicine

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Open Access

A comparative study of the physiological

and psychological effects of forest bathing

(Shinrin-yoku) on working age people with

and without depressive tendencies

Akemi Furuyashiki1* , Keiji Tabuchi2, Kensuke Norikoshi3, Toshio Kobayashi4 and Sanae Oriyama1

Abstract

Background: In recent years, many of Japanese workers have complained of fatigue and stress, considering them as risk

factors for depression. Studies have found that “forest bathing” (Shinrin-yoku) has positive physiological effects, such as

blood pressure reduction, improvement of autonomic and immune functions, as well as psychological effects of

alleviating depression and improving mental health. In this study, we investigate the physiological and psychological

effects of “forest bathing” on people of a working age with and without depressive tendencies.

Methods: We conducted physiological measurements and psychological surveys before and after forest bathing with

subjects who participated in day-long sessions of forest bathing, at a forest therapy base located in Hiroshima

Prefecture. After excluding severely depressed individuals, the participants were classified into two groups: those with

depressive tendencies (5 ≤ K6 ≤ 12) and those without depressive tendencies (K6 < 5) for comparative study. The

evaluation indices measured were systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse rate (PR),

autonomic functions, and profile of mood states (POMS).

Results: Of the 155 participants, 37% had depressive tendencies, without any differences observed between males and

females. All participants showed significant decrease in SBP, DBP, and in negative POMS items after a forest bathing

session. Before the session, those with depressive tendencies scored significantly higher on the POMS negative items than

those without depressive tendencies. After forest bathing, those with depressive tendencies demonstrated significantly

greater improvement in many of POMS items than those without depressive tendencies, and many of them no longer

differed between those with and without depressive tendencies.

Conclusions: Examining the physiological and psychological effects of a day-long session of forest bathing on a

working age group demonstrated significant positive effects on mental health, especially in those with depressive

tendencies.

Not applicable; this is not a report of intervention trial.

Keywords: Forest bathing, Depressive tendencies, Working age, Physiological effects, Psychological effects

* Correspondence: fyasiki@tiara.ocn.ne.jp

1Institute of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3,

Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 2 of 11

Introduction

In Japan, approximately 60% of workers complain about

strong feelings of anxiety, worry, and stress related to work

and occupation [1], so fatigue and stress are regarded as

strong risk factors for depression [2, 3]. According to the

WHO’s World Mental Health Survey, about 10% of people

with mild depressive symptoms develop clinical depression.

The initial response to this has been identified as being im-

portant because there is a danger of more severe symptoms

developing, as well as an increasing risk of suicide when

symptoms are neglected [4, 5]. Many of the increased in-

stances of depression are reported as mild depression, with

sub-threshold depressive symptoms and mood disorders

that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for depression, as

well as non-clinical depression [6–8]. Approaches other

than drug-based therapy for depression, including cognitive

behavioral therapy (CBT), psychotherapy, and other inter-

personal therapies, are recommended for mild depression

[6–8]. The UK’s depression treatment guidelines identify

that exposure to the outdoors and a forest environment

promotes resilience, and aerobic exercise due to physical

activities such as walking alleviates depressed states, and

improves mental health for those with sub-threshold de-

pressive symptoms [7, 9, 10]. Moreover, it has been re-

ported that CBT in a forest environment demonstrates

lower rates of recurrence of depressive symptoms and so-

cial maladjustment, and higher rates of remission than

treatment in hospital [11].

The effects of exposure to a forest environment include

recovery from stress [12], and alleviation of the effects of

reduced attention resulting from fatigue [13]. In Japan,

“forest bathing” (Shinrin-yoku) was first advocated by the

Forestry Agency in 1982, identified as a form of recreation

involving walking and inhaling the fragrant substances re-

leased by trees. The act of “forest bathing” has been

regarded as a natural remedy that brings about improve-

ments in terms of human physical and mental health [14].

Studies have reported relaxation and the effects on organ-

isms arising from terpene components such as phyton-

cide, which are emitted from trees [15, 16]. Miyazaki [17]

conducted a physiological and psychological investigation

on young males in various locations across Japan, compar-

ing the short-term effects of forest bathing, with the same

in suburban areas. The study reported greater physio-

logical effects from forests than urban areas, such as a

decrease in blood pressure, the activation of parasympa-

thetic nervous activity, and the suppression of sympathetic

nervous activity, as well as biochemical effects such as de-

creased salivary amylase and blood cortisol concentra-

tions, and increased immune function [18, 19]. Moreover,

improvement in psychological functioning, such alleviat-

ing negative emotions and increasing positive emotions

were identified [20]. Forest bathing has been demon-

strated to improve negative mood using the profile of

mood states (POMS) mood scale [20, 21], as well as im-

provements in depressive symptoms [22].

While systematic review of forest therapy pointed that

forest therapy may play an important role in health promo-

tion and disease prevention, the lack of high-quality studies

limits the strength of results, rendering the evidence insuf-

ficient to establish clinical practice guidelines for its use

[23]. Further, there has been insufficient consideration of

the physiological and psychological effects of forest bathing

on workers with high stress and depressive tendencies. In

particular, there have been a few studies that have used de-

pression scales to examine changes in depressive tenden-

cies [24–26]. Since depressive tendencies that do not meet

the criteria for depression indicate a higher risk of becom-

ing depression [5, 8], it is important to consider the effect

of forest bathing on Japanese workers with high stress and

depressive tendencies to prevent the deteriorating mental

health of working age people.

In this study, a group of working age people who par-

ticipated in forest bathing were classified into two

groups based on the presence or absence of depressive

tendencies, to conduct an investigation into the physio-

logical and psychological effects of forest bathing, and

compare and examine any changes observed.

Methods

Participants

In the day-long sessions of forest bathing, which were

held a total of 16 times during the 3-year period from

October 2012 to November 2014 at the Akiota town

Forest Therapy Base in Hiroshima Prefecture, the infor-

mation on forest bathing was distributed to working age

people, living in the Hiroshima city areas, who mainly

worked in companies. Then, 219 people applied and

their written consent was acquired for this study.

Inclusion criteria for the participants were working

people aged between 18 and 60. Exclusion criteria were

pregnant women, suspicion of severe depression (13 ≤

K6), and history of depressive and/or cardiovascular dis-

eases. Out of the total participants, 165 participants (19–

59 years old) consented to participate in this study. Ten

participants who had a history of cardiovascular disease or

mental illness, or who were undergoing medical treatment

at the time were excluded. The rest of the 155 participants

(94%) were included in the analysis. Eighty-seven of these

also participated in the evaluation of autonomic nervous

activity, who were assessed before and after forest therapy.

Experimental design

The forest therapy base used for our field research is lo-

cated within a national park in a valley in the region

around the source of the Ota River, in the northwestern

part of Hiroshima Prefecture with mountains in the

1000 m range. The vegetation mainly comprises mixed

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 3 of 11

natural forests, with a temperate climate typical of the

Setouchi region. The Ryuzukyo Forest Therapy Road

used in this study is 3.5 km in length and 335–490 m in

altitude (altitude difference of 155 m).

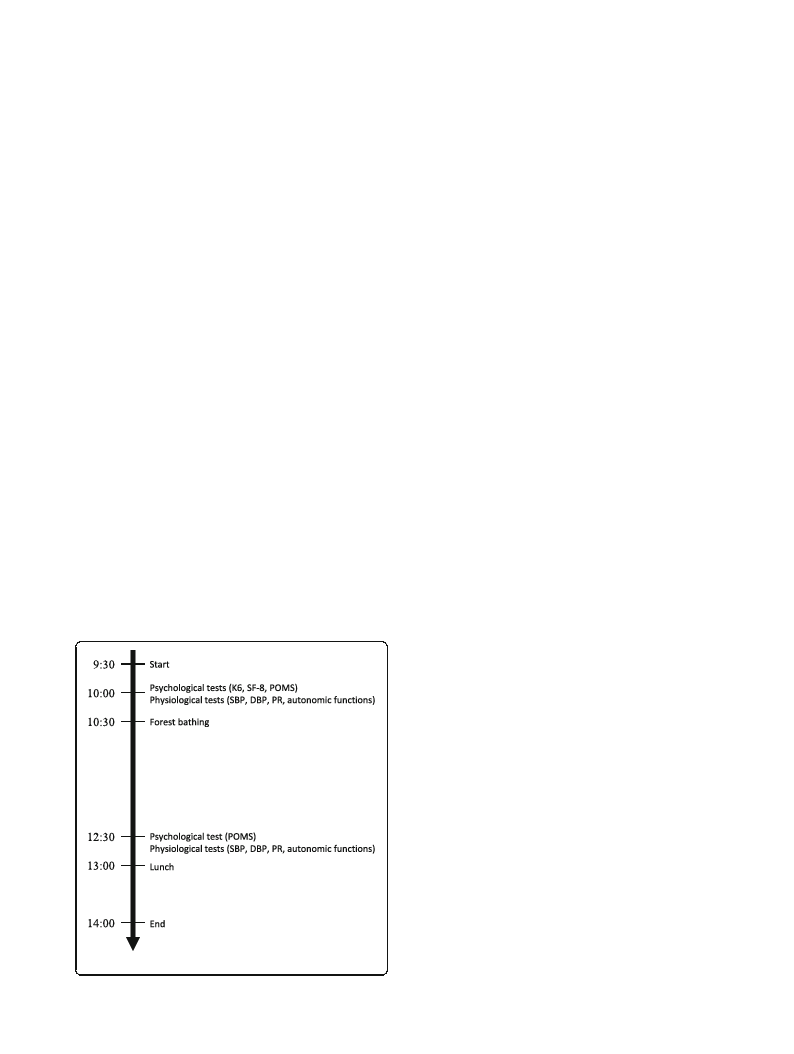

Figure 1 shows the protocol for forest bathing as fol-

lows: participants were gathered at 9:00 am, the nature

of the research was explained, and psychological surveys

and physiological measurements were conducted after

gaining consent from the participants. Participants were

placed into groups of either four or five people for forest

bathing, which involved slowly walking around the forest

for about 2 h, initially with one or two guides. In

addition to explaining the natural environment of the

forest, the guides demonstrated breathing methods,

yoga, hammock experiences, etc. at each point, encour-

aging communication among the participants through-

out the forest bathing. After forest bathing, the same

surveys and measurements were conducted again. All

the participants carried out forest bathing in the autumn

(86.5%) or spring (13.5%) season. The weather was gen-

erally sunny or cloudy, with a temperature of 12–25 °C

and humidity of 40–80% without any environmental

noise. The participants walked 5710 ± 620 steps on aver-

age during 2-h forest bathing, consuming 337–445 kcal.

This research was registered by the Ethics Committee

of Hiroshima University (H25–29 30/04/2014).

Evaluation scales and measurement methods

Psychological measures

Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler

Psychological Distress Scale K6 [4, 5, 27] which evaluates

six items on a scale ranging from (0) “not at all” to (4)

Fig. 1 The protocol for forest bathing

“always,” with a maximum total score of 24 points. The

evaluation of depressive tendencies by K6 score is set in

relation to certain cutoff points; a K6 score of 13 or

more indicates that mental health treatment is required,

while the cutoff point for mental distress is a K6 score

of 5 or more [25, 28]. In this study, those whose K6

score was 13 or more were excluded, and participants

were classified into two groups based on depressive ten-

dencies: those with depressive tendencies (a K6 score of

5 to 12 inclusive) and those without depressive tenden-

cies (a K6 score of 4 or less).

Health-related quality of life was measured with SF-8

[29], which comprises eight items as follows: general

health, physical functioning, physical roles, bodily pain,

vitality, social functioning, mental health, and emotional

roles. It also evaluates a physical component summary

(PCS) and mental component summary (MCS). These

are standardized as Japanese national standard values of

50 points and their standard deviations are 10 points. A

higher score indicates better health [29].

Emotional profiles were measured with the Japanese

edition of POMS [21]. This scale comprises 30 items in

six subscales as follows: Tension-Anxiety (T-A), Depres-

sion-Dejection (D-D), Anger-Hostility (A-H), Fatigue (F),

Confusion (C), and Vigor (V). T-scores standardized by

age and sex were calculated. Additionally, the total mood

disturbance (TMD) score was calculated [TMD = (T-A)

+ (D-D) + (A-H) + F + (C-V)].

Physiological measures

The circulatory functions of systolic blood pressure

(SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and pulse rate

(PR) were measured using an oscillometric monitor

(Omron HEM-1011, Omron Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan).

Autonomic nervous activities were measured using a

finger-tip volumetric pulse wave meter (Pulse Analyzer

Plus View TAS-9, YKC, Tokyo, Japan) [30]. Using the

pulse meter waveform synchronized with the heartbeat

as an index, a fast Fourier transform and spectrum ana-

lysis were performed to measure the power of low fre-

quency (LF: 0.04–0.15 Hz) components and high

frequency (HF: 0.15–0.4 Hz) components. HF was used

as an indicator of parasympathetic activity, and LF/HF

was used to assess the balance between sympathetic and

parasympathetic nervous activity [31].

Circulatory function (SBP, DBP, PR), autonomic nerve

function, and POMS were examined and compared be-

fore and after the forest bathing session. Additionally,

the participants were classified into two groups accord-

ing to the presence or absence of depressive tendencies,

and a comparison was made between the two groups be-

fore and after the forest bathing session.

This study was conducted with the approval of the De-

partment of Nursing Development Science Ethics Review

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 4 of 11

Committee of the Integrated Health Sciences, Institute of

Biomedical and Health Sciences at Hiroshima University

(approval numbers: H 24–27 and H 25–29). We explained

that cooperation with the study was based on participants’

free will and their cooperation could be withdrawn even

after consent to participate in the study had been pro-

vided. Additionally, since forest bathing is conducted in a

natural environment, medical staff also participated in for-

est bathing session to attend to any emergency.

Statistical analysis

The 155 participants’ circulatory function and POMS

were compared and analyzed before and after a forest

bathing session. Changes in autonomic functions were

also compared in the 87 subjects who were measured

correctly. Participants were also classified into two

groups according to the presence or absence of depres-

sive tendencies, and a comparison of the two groups was

conducted. During the analysis, the correlation between

SF-8 and K6, and the normality of data were confirmed

using a Shapiro–Wilk test. Then, t tests, a Wilcoxon

signed rank test, a Chi-square test, a Mann–Whitney U

test, simple regression analysis, and Spearman’s rank

correlation coefficient were used (SPSS ver. 24). The

value for significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Summary of participants

As Table 1 demonstrates, the 155 participants encom-

passed an age range of 19–59 and their mean age was

44.0 ± 3.2. The participants were classified into four

groups: those under 30, those in their 30s, those in their

40s, and those in their 50s. Further, 55.5% of the subjects

were female (Table 1).

The mean K6 score was 3.66 ± 3.24. Fifty-eight partici-

pants (37.4%) evinced depressive tendencies (K6 of 5–12)

and 97 participants (62.6%) did not demonstrate depres-

sive tendencies (K6 of 4 or less). The mean values of K6

score for those with depressive tendencies by age were

also shown in Table 1. Those under 30 years old and those

in their 40s exhibited higher depressive tendencies. How-

ever, there was no significant difference between age

groups. The proportions and mean values for those with

depressive tendencies by sex were 40.6% of males, with an

average of 3.68 ± 2.86 points, and 34.9% of females, with

an average of 3.64 ± 3.52, which was no significant differ-

ence in depressive tendencies in terms of gender.

The health-related quality of life (QOL) mean SF-8

scores for all 155 participants revealed that the PCS

score of 51.2 ± 4.5 was slightly higher than the aver-

age compared to the Japanese standard value of 50.

Table 1 Characteristics of the subjects

All subjects (n = 155)

Non-depressive

tendencya (n = 97)

Mean ± SD

n (%)

n (%)

Age

44.0 ± 9.6

155 (100)

45.0 ± 9.7

Age groups

≤ 29

5.33 ± 3.60 (K6 score)

12 (7.7)

5 (41.7)

30–39

3.40 ± 3.27 (K6 score)

40 (25.8)

26 (65.0)

40–49

4.35 ± 3.28 (K6 score)

52 (33.5)

28 (53.8)

50–59

2.76 ± 2.83 (K6 score)

51 (32.9)

38 (74.5)

Sex

Male

3.68 ± 2.86 (K6 score)

69 (44.5)

41 (59.4)

Female

3.64 ± 3.52 (K6 score)

86 (55.5)

56 (65.1)

Body mass index

22.3 ± 3.2

101 (100)

22.5 ± 2.9

Medication

no

3.45 ± 3.23 (K6 score)

127 (81.9)

84 (66.1)

yesd

4.51 ± 3.17 (K6 score)

28 (18.1)

13 (46.4)

Health-related QOL

PCS

51.2 ± 4.5

155 (100)

51.3 ± 3.8

MCS

47.9 ± 6.0

155 (100)

50.6 ± 4.7

K6 score

3.66 ± 3.24

155 (100)

1.56 ± 1.50

QOL quality of life, PCS physical component summary, MCS mental component summary

aNon-depressive tendency: K6 ≤ 4

bDepressive tendency: 5 ≤ K6 ≤ 12

cChi-square test or Mann–Whitney U test (non-depressive tendency vs. depressive tendency)

dMedication: hypertension (n = 6), dyslipidemia (n = 5), diabetes mellitus (n = 3), others (n = 14)

Depressive

tendencyb (n = 58)

n (%)

42.3 ± 9.3

7 (58.3)

14 (35.0)

24 (46.2)

13 (25.5)

28 (40.6)

30 (34.9)

22.0 ± 3.4

43 (33.9)

15 (53.6)

51.1 ± 5.5

43.2 ± 5.0

7.17 ± 2.10

P valuec

0.470

0.068

0.507

0.816

0.056

0.916

< 0.001

< 0.001

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 5 of 11

On the other hand, the MCS was 47.9 ± 6.0, slightly

lower than the average (Table 1). Additionally, while

there was no significant difference between those with

depressive tendencies and those without depressive

tendencies in terms of PCS, the MCS scores were sig-

nificantly lower (p < 0.001) for the depressive group.

There was also no significant difference between the

PCS and MCS scores in the group without depressive

tendencies, but the MCS score was significantly lower

(p < 0.001) than the PCS score in the depressive ten-

dencies group. The values obtained from the depres-

sive tendencies group were significantly lower than

those obtained from the group without depressive

tendencies (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001) for all measures of

the QOL subscales, apart from physical functioning

(data was not shown).

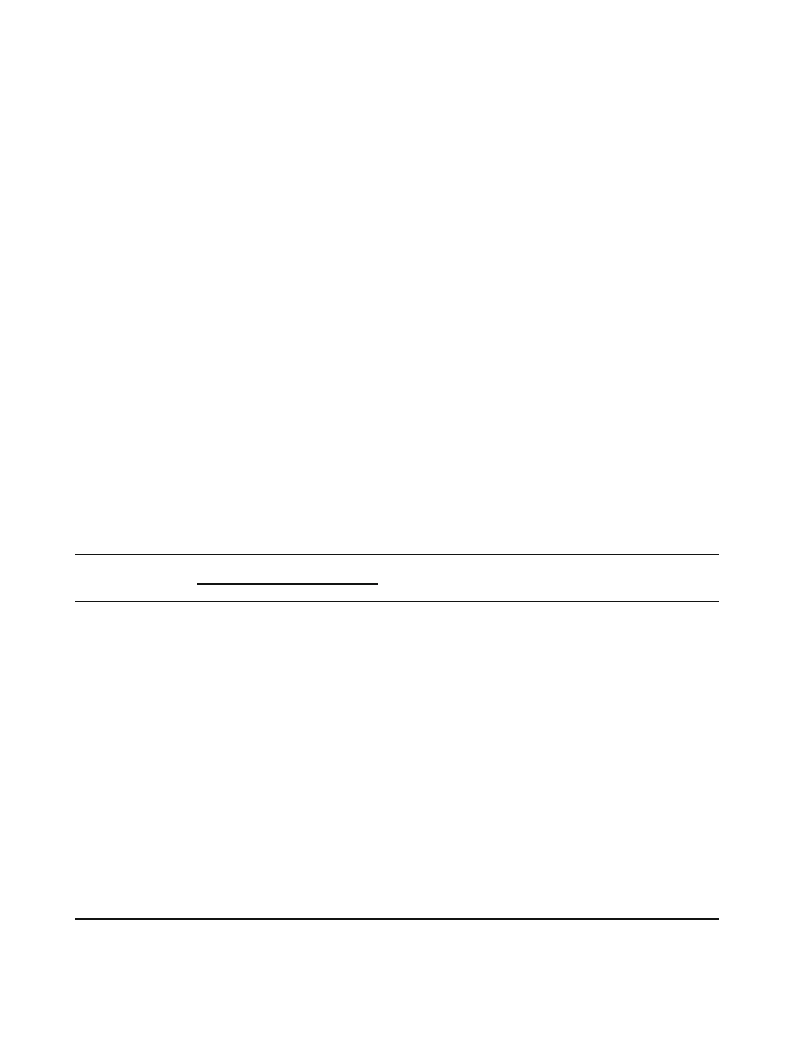

Changes in physiological indicators based on depressive

indicators for all participants and for the two groups

Changes in circulatory function before and after forest

bathing were assessed by measuring the blood pressure

of all subjects, revealing that SBP was 129.8 ± 20.4 mmHg

before forest bathing and 121.5 ± 19.3 mmHg after the

activity was undertaken (Table 2). DBP was 79.0 ±

15.0 mmHg before forest bathing and 74.6 ± 13.8 mmHg

after the activity. Hence, all participants recorded a sig-

nificant decrease in both SBP and DBP (p < 0.001) after

the forest bathing. Measurements of autonomic nervous

function revealed that neither parasympathetic nerve ac-

tivity (ln HF) nor sympathetic nerve activity (ln LF/HF)

registered any significant change.

A comparison of the data for the depressive tendencies

group and without depressive tendencies group before

and after the forest bathing yielded no difference in

blood pressure, in either SBP or DBP levels. Both groups

registered a significant decrease in blood pressure, both

SBP and DBP after forest bathing (p < 0.001). However,

the depressive tendencies group exhibited a significant

rise (p < 0.05) in the PR after forest bathing, and this in-

crease was notably higher than the escalation found in

the without depressive tendencies group (p < 0.05). Add-

itionally, no significant differences were found between

the two groups for ln HF and ln LF/HF before and after

forest bathing (Table 2).

Table 2 Changes of circulatory functions and autonomic functions by Forest bathing in the subjects with and without depressive

tendencies

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, PR pulse rate

*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, paired t test (before vs. after)

aNon-depressive tendency: K6 ≤ 4

bDepressive tendency: 5 ≤ K6 ≤ 12

cWilcoxon signed–rank test (non-depressive tendency vs. depressive tendency)

dLogarithmically transformed value of HF

eLogarithmically transformed value of LF/HF

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 6 of 11

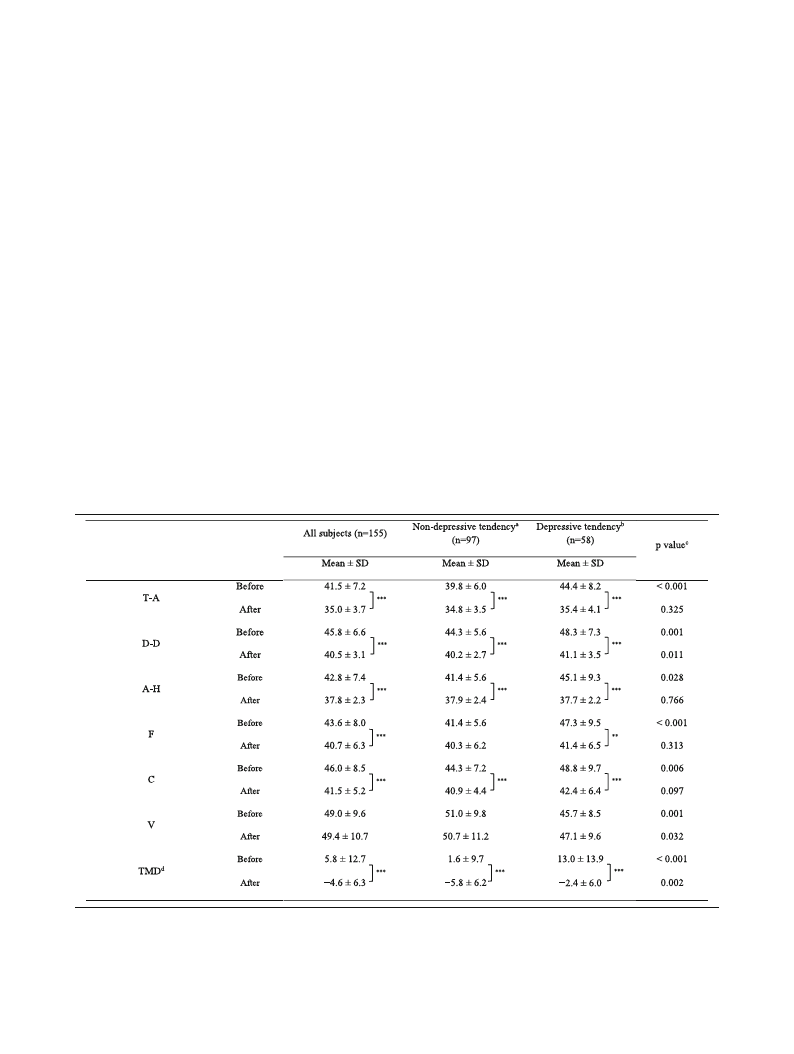

Changes in psychological indicators for all participants

and for the two groups based on the presence or

absence of depressive tendencies

After forest bathing, the POMS scores for all participants

in the five negative subscales decreased significantly:

Tension-Anxiety (T-A); Depression-Dejection (D-D);

Anger-Hostility (A-H); Fatigue (F); and Confusion (C)

(p = 0.001 to p < 0.001) (Table 3). Additionally, the TMD

recorded a negative mood state at 5.8 ± 12.7 before forest

bathing, and changed to a positive mood state at − 4.6 ±

6.3 after forest bathing (p < 0.001).

When comparing the depressive tendencies group and

the without depressive tendencies group, the former

evinced significantly higher negative mood subscales (T-

A, D-D, A-H, F, and C) before forest bathing than the

latter (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001). The positive mood subscale

(V) was also significantly lower in the depressive tenden-

cies group (p = 0.001). After forest bathing, both the de-

pressive tendencies group and the without depressive

tendencies groups demonstrated a significant decrease

in their scores on the negative subscales, but the degree

of improvement was largest for those with depressive

tendencies. In fact, after forest bathing, the multiple

negative scales (T-A, A-H, F, and C) for the depressive

tendencies group decreased to levels equal to those re-

corded by the without depressive tendencies group, to

the extent that any significant difference between the

groups disappeared. Meanwhile, TMD measurements re-

vealed that negative mood states were significantly

greater (p < 0.001) before forest bathing in the depressive

tendencies group than in the without depressive tenden-

cies group, and this score decreased significantly after

forest bathing. Additionally, the degree of modification

in the POMS scales before and after forest bathing was

computed as T-A (− 8.97), D-D (− 7.16), A-H (− 7.40), F

(− 5.88), and C (− 6.41) for the depressive tendencies

group; and T-A (− 5.03), D-D (− 4.09), A-H (− 3.56), F

(− 1.03), and C (− 3.40) for the without depressive ten-

dencies group. Thus, the changes observed in the de-

pressive tendencies group were significantly larger than

those witnessed in the without depressive tendencies

group (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The TMD modifica-

tion was also significantly greater in the depressive ten-

dencies group (p < 0.001).

Table 3 Changes in POMS and TMD scores before and after Forest bathing in the subjects with and without depressive tendencies

T-A tension-anxiety, D-D depression-dejection, A-H anger-hostility, F fatigue, C confusion, V vigor, TMD total mood disturbance

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, paired t test (before vs. after)

aNon-depressive tendency: K6 ≤ 4

bDepressive tendency: 5 ≤ K6 ≤ 12

cWilcoxon signed–rank test (non-depressive tendency vs. depressive tendency)

dTMD Score = (T-A) + (D-D) + (A-H) + F + C – V

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 7 of 11

Discussion

Depressive tendencies of participants and health-related

QOL

Of the 155 participants in this study, 37% presented with

depressive tendencies (K6 of 5–12 inclusive), with the

greatest number among younger and middle-aged people.

For health-related QOL (SF-8), the PCS was close to the

average (50 points), but the MCS was below average. Ac-

cording to the results of the WHO’s World Mental Health

survey, and the World Mental Health Japan Survey, one

in four people reported that they had experienced some

kind of mental health problem in their lifetime [5]. De-

pressed individuals requiring treatment (K6 of 13 or more)

comprised 2.7% of the sample, while 31.3% evinced de-

pressive tendencies (K6 of 5–12) [4, 28]. The proportion

of depressed individuals according to the CES-D (a score

of 16 or more) was 30.6%, indicating that the results of

the K6 are equivalent to those of the CES-D [25, 32]. In

this study, the PCS before forest bathing for those with de-

pressive tendencies was 51.1 and the MCS was 43.2; there-

fore, it appears that the level of physical health-related

QOL in this group was about average, while psychological

health-related QOL was lower than average.

Changes to physiological indicators as a result of forest

bathing

SBP and DBP of the participants showed a significant de-

crease as a result of the forest bathing for about 2 h. How-

ever, no change was observed in PR, HF, and LF/HF,

which are indicators of autonomic nervous activities. This

contrasts with an observational study that was conducted

over 2 days in several forest regions throughout Japan [18,

19]. This study of young males walking and sitting for

short periods reported the physiologically relaxing effects

of walking in forested areas compared to urban cities.

These results were associated with reduced SBP and DBP,

as well as decreased HR and LF/HF, and an increase in HF

[17, 19, 22]. However, research into the effects of multiple

strolls before and after walking for 2 to 3 h in a forest en-

vironment over the course of a day revealed that although

SBP decreased, DBP and PR did not change, and auto-

nomic nervous activity was not measured [33]. The drop

in blood pressure reported in the present study was the

same as in previous studies, and this outcome may result

from the physiologically relaxing effect derived from ex-

posure to fragrance from the trees, and the bodily sensa-

tions of being in the forest [15–17]. It is also possible that

changes in PR and autonomic nervous activities were not

observed in the present study due to the difference in the

age of participants, and the time they spent sitting [14,

34]. Additionally, this study observed single sessions of

forest bathing of working age people, which lasted about

2 h. It is possible that participants did not reach a satisfac-

tory state of relaxation due to the effects of physical activ-

ity during forest bathing [35].

Furthermore, no significant difference in circulatory func-

tion and autonomic nervous function was observed before

forest bathing between participants with and without de-

pressive tendencies. Both SBP and DBP showed a signifi-

cant decrease in both groups after forest bathing, and only

those with depressive tendencies showed a significant rise

in PR. Other studies have found that those with depressive

tendencies are less active in their daily lives and that they

engage in fewer leisure activities [36]. This lack of activity

lowers their physical fitness [37], and fatigue due to walking

may reduce parasympathetic nervous activity [38]. In the

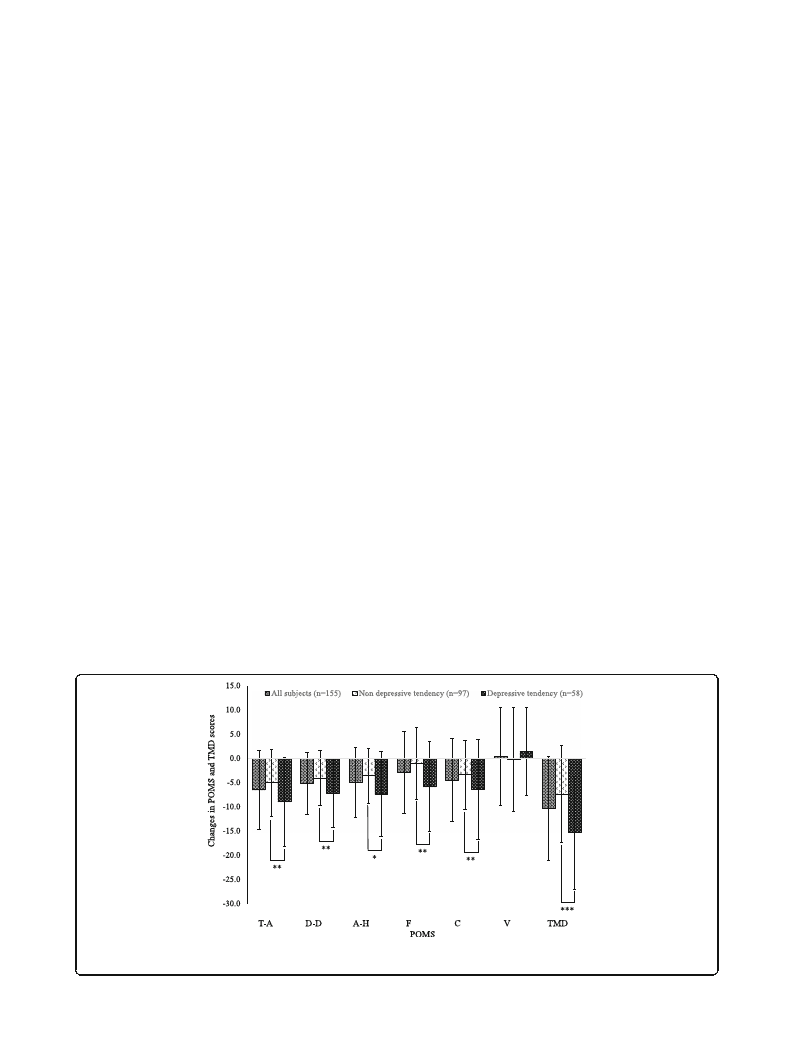

Fig. 2 Changes in POMS and TMD scores by forest bathing (after-before value). T-A Tension-Anxiety, D-D Depression-Dejection, A-H Anger-

Hostility, F Fatigue, C Confusion, V Vigor, TMD Total Mood Disturbance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, paired t-test

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 8 of 11

present study, it is possible that the physical load and feel-

ings of fatigue were greater for those with depressive ten-

dencies, even only slow walking over about 2 h.

Changes to psychological indicators as a result of forest

bathing

Changes in psychological indicators (POMS), including

the negative mood states (T-A, D-D, A-H, F, and C) and

TMD scores were significantly improved for all partici-

pants following forest bathing. However, no alteration to

the positive mood state (V) was observed. On this issue,

studies of short-term walking over a period of 2 days

and one night conducted in multiple areas took mea-

surements when participants were walking or engaging

in seated viewing [14, 21]. These investigations reported

a significant decrease in T-A, D-D, AH, F, and C, and a

noteworthy increase in V in forested areas compared to

urban locations [17, 20, 22]. Additionally, improvements

to negative mood due to reduced negative scales and

TMD in POMS were observed, and there was only a

slight increase in positive mood (V) after multiple forest

bathing activities were undertaken, such as walking for

1–2 h in forested areas [33, 34]. In contrast to this,

Ulrich found that emotions such as fear, anger, and dis-

gust initially appeared in the bodies and expressions of

humans upon contact with nature, followed by a prompt

reaction of recovery from these negative emotions. After

the negative emotions dissipated, positive emotions such

as joy were subsequently found to gradually increase

[12]. The present study’s findings are similar to those

mentioned above: there were improvements in the nega-

tive mood scales but not in the positive scales after forest

bathing. This outcome suggests that similar changes to

POMS due to forest bathing can be obtained even if the

ages and walking times of participants differ across studies

[14, 20]. However, it has been suggested that the expres-

sion of a positive mood after forest bathing may be af-

fected by the waking time and background of participants.

In this study, significant changes in psychological indi-

cators were greater in those with depressed tendencies

than in those without depressive tendencies. Corres-

pondingly, the improvement recorded after forest bath-

ing was also greater for the depressive tendencies group,

to the extent that after forest bathing, there was no sig-

nificant difference in negative mood state values re-

corded for the two groups.

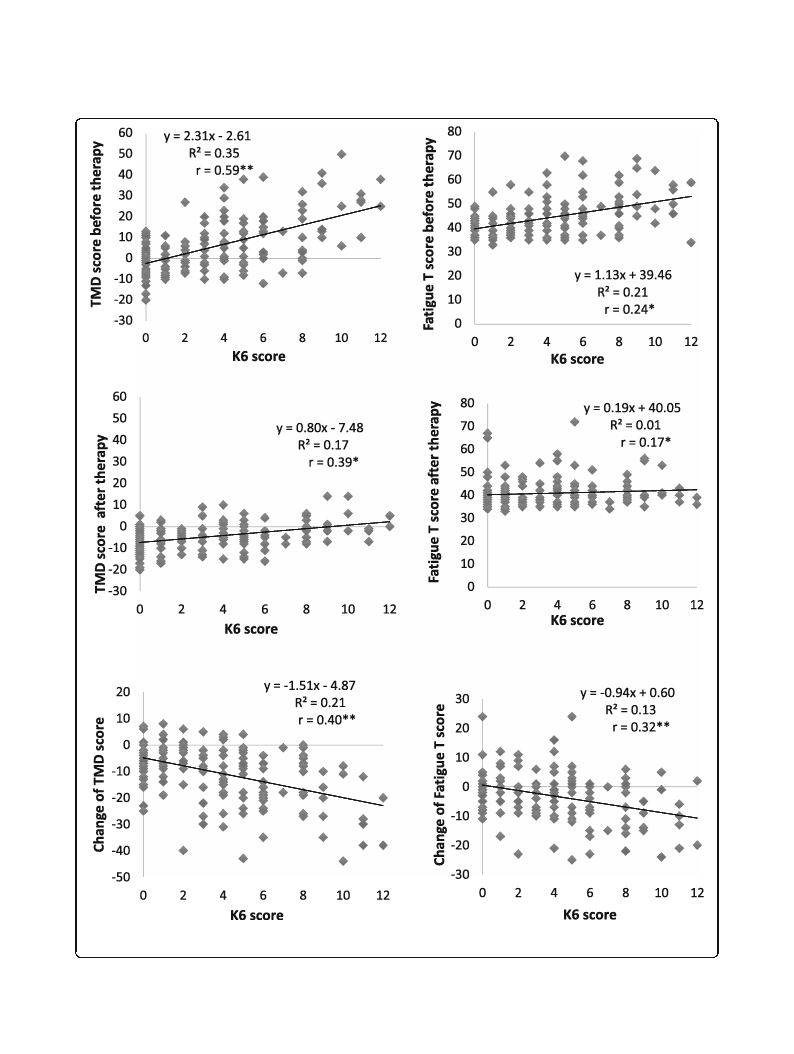

The POMS values before and after forest bathing were

individually examined, as were the K6 scores, and the re-

lationship between changes recorded before and after

forest bathing. Figure 3 illustrates the relationship be-

tween the TMD scores, the fatigue (F) score of the sub-

scale, and the K6 score. Before forest bathing, both the

TMD and F scores showed an upward trend as K6

scores increased. After forest bathing, both TMD and F

scores converged to a nearly constant range regardless

of K6 scores, such that higher K6 scores were associated

with a greater decrease in TMD and F scores as a result

of forest bathing. Thus, a negative correlation was found

between the change in TMD and F scores before and

after forest bathing, and K6 scores. In this study, higher

K6 values were associated with greater improvements to

the TMD scores of the negative POMS mood states after

forest bathing, and also linked to an improvement (de-

crease) of the t values of the negative scales. Studies have

found that individuals with high blood pressure or high

stress levels are more likely to exhibit improvement after

forest bathing than healthy individuals [24, 34]. In this

context, Damasio defines homeostasis as a state that is

maintained within a preset range [39] and posits that

homeostasis has two aspects: physiological and psycho-

logical. Thus, improvements in POMS negative emo-

tions in those with depressive tendencies may have

occurred due the action of psychological homeostasis.

Meanwhile, Kaplan’s [13] study of the improvement of

depressive tendencies through CBT incorporated the

practice of mindfulness in a forest environment. This

study revealed that the act of focusing one’s attention on

the forest through meditation and breathing facilitated

an attention recovery process, where feeling contented

in one’s body and becoming aware of one’s inner self led

to the acquisition of the ability to self-heal. Okamoto [2]

and Yoshimura [40] reported the alleviation of depres-

sive symptoms and psychosocial dysfunctions through a

CBT intervention, as well changes to brain regions ob-

served using functional image analysis methods. It is

possible that CBT may effect changes in both the neural

basis of negative cognitive-emotional interactions and in

the higher order mental functions of cognition and be-

havior [2]. In the current study, participants mentioned

positive experiences with guides and colleagues follow-

ing forest bathing. Improvements observed in depressive

symptoms and psychosocial functions may be linked to

the possible activation of neural networks through posi-

tive emotional reflection [32], and improved social cog-

nitive functions through the stimulation of mirror

neurons, leading to a better understanding of the

intended actions and emotions of others [41].

Previous study also reported that psychological and so-

cial stimulation occurs through interaction with the envir-

onment [23, 42]. Participants with depressive tendencies

in this study became relaxed, and negative emotions that

were strong before forest bathing were greatly reduced

after forest bathing activity. This outcome confirms the

physiological and psychological health benefits of forest

bathing and implies potential stress reduction and recov-

ery from fatigue for those of working age with depressive

tendencies. Additionally, this study demonstrates that the

use of a forest environment can enhance recovery from

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 9 of 11

Fig. 3 Correlation coefficient between K6 and TMD score, fatigue T score (POMS subscale). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, Spearman’s rank correlation co-

efficient, and their changes before and after forest therapy

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 10 of 11

stress and fatigue in all participants, regardless of whether

they evince depressive tendencies. Hence, forest bathing is

an activity that can assist in the prevention of depression

and stress-related health problems, leading to improve-

ment in the mental health of working individuals.

However, it is possible that “regression to the mean”

have influenced the results of this study demonstrating

significantly greater improvement in many of POMS

score for those with depressive tendencies. It is import-

ant that the improvement in POMS score for those with

depressive tendencies was much greater than for the

non-depressive tendencies after forest bathing, and that

no more significant differences were identified in many

of POMS scores between the two groups. Hence, we

think that it is difficult to explain the greater improve-

ment of POMS score in depressive tendencies simply by

“regression to the mean.”

Moreover, as we did not measure sex hormones in this

study, we cannot discuss the influence of the menstrual

cycle of the female subjects. However, there is no differ-

ence in the ratio of males and females among the two

groups. Additionally, the menstrual cycle is randomly

assigned to the two groups, and no intentional bias is

recognized. As this study focused on short-term changes

such as examining physiological and psychological

changes before and after forest bathing for individuals, it

is considered that sex hormones may have little influ-

ence on the results of this study.

In this study, the improvement of mental health was

statistically significant, especially in the participants with

depressive tendencies. Changes were sufficiently large to

be clinically meaningful. However, it will be necessary to

conduct further studies to validate the efficacy of forest

bathing for working age people with depressive tenden-

cies, since other outcomes, such as autonomic functions,

did not change significantly. Additionally, this study was

limited to results obtained from a single day’s activity

over about 2 h, and, thus, can only confirm a short-term

effect. The study was also limited by the paucity of

cross-sectional research to corroborate its effects. Mov-

ing forward, a more detailed examination of the benefi-

cial health effects of forest bathing is required, through

the establishment of control groups and the implemen-

tation of overnight forest bathing sessions.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that a session of ap-

proximately 2 h of forest bathing as part of a 1-day out-

ing in a forest environment can lead to improvements in

physiological and psychological health in people of

working age, as demonstrated by the decrease in blood

pressure and the alleviation of negative psychological pa-

rameters after forest bathing.

Moreover, participants with depressive tendencies

showed a greater improvement in many of the

POMS items after forest bathing compared to those

who did not display depressive tendencies. This out-

come is evidence that a 1-day forest bathing activity

was particularly effective at enhancing the psycho-

logical wellbeing of working age people with depres-

sive tendencies.

Abbreviations

A-H: Anger-Hostility; C: Confusion; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; D-

D: Depression-Dejection; F: Fatigue; HF: High frequency; LF: Low frequency;

MCS: Mental component summary; PCS: Physical component summary;

POMS: Profile of mood states-brief form; PR: Pulse rate; SBP: Systolic blood

pressure; T-A: Tension-Anxiety; TMD: Total mood disturbance; V: Vigor

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank everyone who participated in this study,

including the staff members involved in the conduction of this research project

at Akiota town and the Satoyama guides who worked with the authors.

Funding

Funding for the implementation of forest bathing was provided by Akiota

town and funding for reporting the research results was provided by

Hiroshima University. Additionally, Akiota town was involved in the

implementation of forest bathing, but it was not involved in the research

design, analysis and data reporting.

The authors of this study did not receive funds from any funding institution.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available upon request to the first author.

Authors’ contributions

AF contributed to the experimental design, data acquisition, statistical

analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. KT and KN

contributed to the whole process of research design, experimental design,

interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. TK was involved in the

overall research. SO participated in study design and manuscript preparation.

All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects gave their informed consent to participate after agreeing to the

purpose, method and importance of the study. The study conformed to the

Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and was approved by the ethics

Committee of Hiroshima University (H24–27 and H25–29).

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data; we agree to

the disclosure.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author details

1Institute of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3,

Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan. 2Research and Education

Faculty, Medical Sciences Cluster, Nursing Science Unit, Kochi University,

Kohasu Okocyo, Nankoku, Kochi 783-8505, Japan. 3Faculty of Nursing,

Hiroshima International University, 5-1-1, Hiro koshingai, Kure, Hiroshima

737-0112, Japan. 4Department of General Internal Medicine, Ishii Memorial

Hospital, 3-102-1, Tada, Iwakuni, Yamaguchi 741-8585, Japan.

Furuyashiki et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:46

Page 11 of 11

Received: 23 January 2019 Accepted: 30 May 2019

References

1. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Title of conditions such as physical

fatigue and mental stress. Healthy situation survey, Labor Survey; 2012.

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/dl/h24-46-50_01.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar

2017.

2. Okamoto Y. Functional brain basis of pathophysiology in depression.

Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;111(11):1330–44. (in Japanese).

3. Kaji T, Mishima K, Kitamura S, Enomoto M, Nagase Y, Li Q, et al. Relationship

between emergence of depressive symptoms in mature and stress on

lifestyle-cross-sectional study in a large-scale group representing the

general population of Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;113(7):633–61.

(in Japanese).

4. Kawakami N, Takashima T, Ono Y, Uda H, Hata Y, Nakane Y, et al. Twelve-

month prevalence, severity, and treatment of common mental disorders in

communities in Japan: preliminary finding from the world mental health

Japan survey 2002–2003. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(4):441–52.

5. Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Bromet E, Cuiten M, et al.

Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6

screening scale: results from the WHO world mental health (WMH) survey. J

Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(S1):4–22.

6. Japan Depression Association. Production guidelines preparation

Committee for Mood Disorder Production. Title of chapter 2 mild

depression. In: Japan depression society treatment guidelines. Depression

(DSM-5)/major depressive disorder; 2016. p. 20–34. (in Japanese).

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington: Am Psychiatric Assoc; 2013.

8. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health commissioned. Depression in

adults: the treatment and management of depression in adults. London: National

Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, University College; 2010. p. 536–64.

9. Social and Economic Research Group. Mindfulness practice in woods and

forests: an evidence review. In: Bianca Ambrose-Oji report to the Mersey

forestry; 2012. p. 1–56.

10. Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: theoretical foundation and

evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol Inq. 2007;18(4):211–37.

11. Kim W, Lim SK, Chung EJ, Woo JM. The effect of cognitive behavior

therapy-based psychotherapy applied in a forest environment on

physiological changes and remission of major depressive disorder.

Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6(4):245–54.

12. Ulrich RS. Title of aesthetic and affective response to natural environment.

In: Human behavior and environment. New York: Plenum; 1983. p. 85–125.

13. Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative

framework. J Environ Psychol. 1995;15(3):169–82.

14. Takeda A, Kondo T, Takeda N, Okada R, Kobayashi I. Good mind-healing and

health keeping effects in the forest walking. Heart. 2009;41(4):405–12. (in

Japanese).

15. Independent Administrative Agency Forestry Research Institute. Comparison

of therapy effects in different natural environments and research on familiar

forest therapy effect. In: Forestry Research Institute Grant Project Research

Outcome Collection, vol. 46; 2011. p. 1–42. (in Japanese).

16. Matsubara E, Kawai S. Gender differences in the psychophysiological effects

induced by VOCs emitted from Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica).

Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-018-

0700-9.

17. Miyazaki Y. Science of nature therapy. Center for environmental, health, and field

sciences Chiba University Science of nature therapy. Center for environment,

health, and field sciences Chiba University. https://www.marlboroughforestry.org.

nz/mfia/docs/naturaltherapy.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2017.

18. Park BJ, Tsunetsugu Y, Kasetani T, Kagawa T, Miyazaki Y. The physiological

effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing):

evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ Health

Prev Med. 2010;15:18–26.

19. Tsunetsugu Y, Park BJ, Miyazaki Y. Trends in research related to “Shinrin-

yoku” (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing) in Japan. Environ

Health Prev Med. 2010;15(1):27–37.

20. Tsunetsugu E, Park BJ, Lee J, Kagawa T, Miyazaki Y. Psychological relaxation

effect of forest therapy—results of field experiments in 19 forests in Japan

involving 228 participants. Jpn J Hyg. 2011;66(4):670–6. (in Japanese).

21. Yokoyama K et al. Profile of mood states-brief form. Kaneko Shobo, Tokyo;

2005. (in Japanese).

22. Li Q, Kawada T. Possibility of clinical application of forest medicine. Jpn J

Hyg. 2014;69(2):117–21. (in Japanese).

23. Oh B, Lee KJ, Zaslawski C, Yeung A, Rosenthal D, Larkey L, Back M. Health and

well-being benefits of spending time in forests: systematic review. Environ

Health Prev Med. 2017;22:71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-017-0677-9.

24. Morita E, Fukuda S, Nagano J, Hamajima N, Yamamoto H, Iwai Y, et al.

Psychological effects of forest environments on healthy adults Shinrin-yoku

(forest-air bathing, walking) as a possible method of stress reduction. Public

Health. 2007;121(1):54–63.

25. Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K, Yanagida K, Kawakami N. Screening

performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and

anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65:434–41.

26. Cuijpers P, Smit F. Subthreshold depression as a risk indicator for major

depressive disorder: a systematic review of prospective studies. Acta

Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:325–31.

27. Prochaska JJ, Sung HY, Max W, Shi Y, Ong M. Validity study of the K6 scale

as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health

treatment need and utilization. J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(2):88–97.

28. Inoue A, Kawakami N, Tsuno K, Tomioka K, Nakanishi M. Organizational justice

and psychological distress among permanent and non-permanent employees

in Japan: a prospective cohort study. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20(2):265–76.

29. Fukuhara S, Suzukamo Y. Health related QOL SF - 8 TM Japanese edition

manual: NPO Health Medical Evaluation Research Organization, Kyoto; 2004.

(in Japanese).

30. Sawada Y, Kato Y. Hemodynamics of ther finger photo-plethysmogram:

Examinations with emphasis on normalized pulse volume. J J Physiol

Psychol Pshychophysiol. 2014;32(3):157-72. (in Japanese).

31. Yoshida N, Asakawa T, Hayashi T, Matsuno-matumoto Y. Evaluation of the

autonomic nervous function with plethysmography under the emotional

stress stimuli. Biomed Eng. 2011;49(1):91–69.

32. Matsunaga M, Okamoto Y, Suzuki S, Kinoshita A, Yoshimura S, Yoshino A, et

al. Psychosocial functioning in patients with treatment- resistant depression

after group cognitive behavioral therapy. BMS Psychiatry. 2010;10:22. https://

doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-22.

33. Ochiai H, Ikei H, Song C, Kobayashi T, Miura T, Takamatsu A, et al.

Physiological and psychological effects of a forest therapy program on

middle-aged females. J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(3):2532–42.

34. Horiuchi M, Endo J, Akatsuka S, Uno T, Hasegawa T, Seko Y. Influence of

forest walking on blood pressure, profile of mood states and stress markers

from the viewpoint of aging. J Aging Gerontol. 2013;1:9–17.

35. Cooper SJ. From Claude Bernard to Walter Cannon. Emergence of the

concept of homeostasis. Appetite. 2008;51:419–27.

36. Kai Y, Nagamatsu T, Shiga T, Sugimoto M, Komatsu Y, Suyama Y. Association

of leisure time physical activity on depressive symptoms with job strain. Bull

Phys Fit Res Inst. 2009;107:1–10. (in Japanese).

37. Kubota A, Takeuchi R, Harada K. Longitudinal study on relationship between

depressed state and physical fitness in workers. Welf Indic. 2011;58(4):15–

22. (in Japanese).

38. Tsujiura Y, Toyoda K. Physical and mental reactions to forest relaxation

video studies on gender differences. Jpn J Hyg. 2013;68(3):175–88. (in

Japanese).

39. Damasio A, Damasio H. Exploring the concept of homeostasis and considering

its implications for economics. J Econ Behav Organ. 2016;216:125–9.

40. Yoshimura S, Okamoto Y, Onoda K, Mitsunaga M, Okada G, Kunisako K, et al.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression changes medial prefrontal and

ventral anterior cingulate cortex activity associated with self-referential

processing. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(4):487–93.

41. Ishida H. Brain mechanisms for prediction of other’s perception and

emotion. Emot Stud. 2016;2(1):31–7. (in Japanese).

42. Roe J, Aspinall P. The restorative benefits of walking in urban and rural settings

in adults with good and poor mental health. Health Place. 2011;17:103–13.