The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy

Volume 10

Issue 1 Winter 2022

Article 7

January 2022

Ecospirituality in Forensic Mental Health: A Preliminary Outcome

Study

Clark Patrick Heard

The University of Western Ontario - Canada, clark.heard@sjhc.london.on.ca

Jared Scott

The University of Western Ontario - Canada, jared.scott@sjhc.london.on.ca

Stephen Yeo

Martin Luther University College, Laurier University - Canada, stephen.yeo@sjhc.london.on.ca

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot

Part of the Occupational Therapy Commons, Other Mental and Social Health Commons, and the Other

Rehabilitation and Therapy Commons

Recommended Citation

Heard, C. P., Scott, J., & Yeo, S. (2022). Ecospirituality in Forensic Mental Health: A Preliminary Outcome

Study. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 10(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1708

This document has been accepted for inclusion in The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy by the editors. Free,

open access is provided by ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu-

scholarworks@wmich.edu.

Ecospirituality in Forensic Mental Health: A Preliminary Outcome Study

Abstract

Background: In this study, the personal experience of spirituality in nature (the concept of ecospirituality)

was supported by occupational therapy and spiritual care staff enabling a community-based group for

persons affiliated with a forensic mental health system in Ontario, Canada. Spirituality is a key, though

debated, tenet in occupational therapy practice. At the same time, immersive participation in nature has

been linked to positive health outcomes.

Methods: A qualitative method consistent with Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis was employed.

Data was collected via the completion of semi-structured interviews (n = 9). Collected data was

transcribed verbatim and then coded for themes by multiple coders. Several methods were employed to

support trustworthiness.

Results: Results identified that participation in the ecospirituality group enabled the participants to feel an

enhanced connection with nature and an opportunity for unguarded reflection and relaxation. The

participants described a regenerative and restorative experience, including a sense of peace and

connection with the personally sacred. Enhanced resiliency and meaningful connection with others also

were identified.

Conclusion: Recommendations related to outcomes are identified. These include a focus on enhanced

access to natural environments for individuals involved in mental health systems. Just as importantly, the

opportunity for personal agency and autonomy in those settings appears indicated.

Comments

The authors declare that they have no competing financial, professional, or personal interest that might

have influenced the performance or presentation of the work described in this manuscript.

Keywords

ecotherapy, nature therapy, forensic, mental health, spirituality

Cover Page Footnote

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of several individuals who supported this

project. At the Southwest Centre for Forensic Mental Health Care in St. Thomas, ON: Sarah McCallum,

social worker; Allan Tetzlaff, RN/coordinator (Retired); Kent Lewis, occupational therapist/coordinator;

and Janice Vandevooren, occupational therapist/director. At St. Joseph's Health Care London, Spiritual

Care Coordinator Ciaran McKenna (Retired) and Spiritual Care Coordinator Dale Nikkel.

Credentials Display

Clark Patrick Heard, OTD, OT Reg. (Ont.); Jared Scott, MScOT, OT Reg. (Ont.); Rev'd Stephen Yeo, M.Div, RP,

CSCP

Copyright transfer agreements are not obtained by The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy

(OJOT). Reprint permission for this Applied Research should be obtained from the

corresponding author(s). Click here to view our open access statement regarding user rights

and distribution of this Applied Research.

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.1708

This applied research is available in The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/

ojot/vol10/iss1/7

Heard et al.: Ecospirituality in forensic mental health

Nature and participation in natural environments have markedly influenced the health care milieu

for centuries. These influences range broadly from concepts of hospital and care facility design to day-

to-day clinical application in treatment planning (Codinhoto, 2017; Wagenfeld et al., 2013). The impact

of nature as a care informer has been considered over time using various terms, but most commonly in

the modern era the terms nature or eco are used as a prefix related to various therapeutic approaches or

interventions (Hansen et al., 2017; Song et al., 2016; Summers & Vivian, 2018).

Like nature and natural environments, the unique and personal experience of spirituality has also

significantly influenced the provision of health care over time. In the occupational therapy profession,

interest in spirituality as a professional and care informer has particularly enhanced over the past 5

decades (Egan & Delaat, 1994; Newbigging et al., 2017; Townsend & Brintnell, 1990; Wilson, 2010).

Although spirituality is a topic of much professional discourse, the centrality of spirituality in the

profession has compelled its inclusion in occupational therapy practice models defining professional

practice (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2014; Townsend & Polatajko, 2013).

This qualitative study considers the outcomes of participation in a community-based

ecospirituality (the personal experience of spirituality in nature) group for nine (n = 9) individuals

affiliated with the Forensic Mental Health System in Ontario, Canada. Such individuals have come into

contact with the criminal justice system in the Province of Ontario, have been found not criminally

responsible for their offense(s) and, via legal disposition order, have been instructed to reside at the

Southwest Centre for Forensic Mental Health Care. Over a 16-week period and with a +/-120 min

duration, the group enabled the participants to visit local and freely accessible community nature spaces

proximal to the forensic hospital facility.

One factor possibly differentiating the group from more conventional therapist-driven and skill-

building groups was that it did not, specifically, focus on remediating deficits. Rather, the participants

were empowered to have personal agency and self-determination in the varied nature spaces they

attended, pending staff forensic disposition and security accountabilities to the Ontario Review Board

(Hamilton, 2017; Heard et al., 2015; Ontario Review Board, 2011). More importantly, this study

considers the outcomes of a participant experience that the participant both determines and narrates.

Review of the Literature

Conceptualizing Ecospirituality

The concept of ecospirituality as advanced by the authors (two occupational therapists and a

spiritual care professional) speaks to the intersection of the personal experience of spirituality with the

concurrent participation in nature. This is broadly consistent with more modern approaches related to

ecospirituality in health care application. In the nursing context, Lincoln (2000) speaks to an

“interconnection between human beings and the environment” (p. 228) while Delaney and Barrere

(2009) describe ecospirituality as the “spiritual dimension between human beings and the environment”

(p. 365). This study advances an immersive and participatory approach related to the ecospirituality

concept consistent with current occupational therapy and spiritual care theory.

In conceptualizing this group, the authors drew from current occupational therapy and spiritual

care theory to support development. In particular, the authors considered the Canadian Model of

Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E), noting that this model conceptually places

spirituality at the core or center of each individual. As well, the CMOP-E advocates for the concept of

occupational engagement that, beyond occupational performance, speaks specifically to concepts of

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2022

1

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 10, Iss. 1 [2022], Art. 7

meaning making and self-efficacy that arise from occupational performance, participation, or in

reflection (Townsend & Polatajko, 2013).

The authors also specifically considered Law’s (2002) work on participation in her American

Occupational Therapy Association Distinguished Scholar Lecture, “Participation in the Occupations of

Everyday Life.” In that work, Law specifically linked the institutional environment with limited

participation outcomes for persons with disability. One factor Law noted was “issues of poverty, costs of

programs” (p. 644). In considering the ecospirituality group, one key element in its design was that it

would be practical, generalizable, and cost-efficient, enabling individuals to attend and participate in

community-based nature spaces that would be freely accessible to them during their hospital tenure (if

and when eligible for community pass participation) and also following discharge.

Theory employed in the provision of spiritual care also informed the group development. In

particular, the spiritual care professional supporting the group approached development though a lens

that first accounted for spiritually integrated psychotherapy concepts in considering how spirituality can

contribute to wholeness and wellness for each individual (Pargament, 2011). As well, Fisher’s (2011)

Four Domains Model of Spiritual Health and Well Being was considered. This model, which describes

spiritual health as a “dynamic state of being,” includes among its four domains: “the

personal…communal…environmental…transcendental” (p. 17). In particular, the authors adopted

Fisher’s position that spirituality is innate and unifies the whole person.

Concepts of ecopsychology, as informing spiritual care, also influenced the group development.

One example of this is work by Jordan (2015) who indicates: “ecopsychology has attempted to position

the psyche as both needing to connect with the environment and suffering from the results of this

disconnection” (p. 14). The articulation and examination of each participant’s experience at the

conclusion of each session enabled dialogue about what Jordan (2015) calls “the reciprocal effects of

human and natural world interaction” (p. 14). Finally, Perriam’s (2015) conceptual work on the concept

of sacred spaces informed the group development, as participation in these enables individuals to have

“active involvement in determining one’s well-being” (p. 29).

Historical Context and Informers

While a focus on “eco” or “nature” concepts may seem more prevalent today, history tells us that

the natural environment has long held a key place in the mental health care milieu. The inclusion of

accessible nature and outdoor spaces have been key tenets informing hospital and care facility design

and care application dating back more than two centuries. Indeed, these concepts came to define care

provision and hospital design for much of the 19th and early 20th century. Psychiatric facility designers

of that era, adherents to the concept of Moral Treatment, sought to create environments (then called

asylums) that enabled wellness with the natural environment as a key component. In York, English

philanthropist and mental health reformer Samuel Tuke (1815) wrote about his design for the York

Retreat:

There is not a shadow of a reason for insane persons, in general, being subjugated to the misery

of gloom as well as confinement; and when it is considered how many hours patients of this

description commonly spend in their bed-rooms, the absence of light must be, to many, a serious

privation. (p. 39)

Charland (2007), in analysis of Tuke’s influential York Retreat, noted: “location and healthy activities

were important ingredients of this healing environment (p. 66).

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol10/iss1/7

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.1708

2

Heard et al.: Ecospirituality in forensic mental health

In the United States, psychiatrist and designer Thomas Story Kirkbride was significantly

influenced by Tuke’s work. Kirkbride (1880), in writing about construction and organization of

hospitals for persons with mental illness, supported grounds of “at least one hundred acres of land” and

of those:

from thirty to fifty acres immediately around the buildings, should be appropriated as pleasure

grounds, and should be so arranged and enclosed as to give the patients the full benefit of them,

without being annoyed by the presence of visitors or others. It is desirable that several acres of

this tract should be in groves or woodland, to furnish shade in summer. (p. 7)

In On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane (1880),

Kirkbride defined mental health facility construction in North America for more than half a century.

In New Zealand in the late 19th century Sir Frederic Truby King followed a similar

philosophical approach. At the Seacliffe Asylum he linked agricultural and outdoor participation with

positive psychiatric outcomes. Stock and Brickell (2013) noted that “King shared a belief in the

importance of fresh air and sunshine—the environment, if you will; if mental instability did set in, these

elements offered the main route to recovery” (p. 109).

Outdoor occupational participation in agricultural tasks and farming has been co-occurring with

mental health facilities and prisons for centuries. Of this, Sempik (2010) noted that “opportunities for

physical labour, rehabilitation and often a pleasant pastime in the company of other people . . . the

gardens and farms satisfied physical, social and productive needs of patients” (p. 16).

Modern Context and Informers

Participation in nature has been a significant historical informer in mental health care; it also has

notable currency in the modern era. Several modern theoretical approaches have markedly influenced

what seems a renewed centrality for nature/eco inputs in health care. First, the emergence of Wilson’s

(1984) Biophilia Hypothesis identified that humans, inherently, have a fundamental and genetically

informed need to affiliate and connect with other living organisms. Another influential approach,

Kaplan’s (1995) Attention Restoration Theory, posited that participation in nature can promote wellness

via restoration of a limited cognitive resource, directed attention. Another currently influential approach

is the concept of Shinrin-Yoku (forest bathing). Originating in the 1980’s, forest bathing “is a traditional

Japanese practice of immersing oneself in nature by mindfully using all five senses” (Hansen et al.,

2017, p. 1). In application, research has identified some benefits for participants in reduction of stress,

anxiety, and depression symptoms (Hansen et al., 2017; Oh et al., 2017). Interest in this approach has

also included some evolution of and modification in mental health care settings to include walking in

nature proximal to care facilities with some reasonable outcomes in symptom mediation for individuals

with affective disorders and psychosis (Bielinis et al., 2019).

Interest and application of these concepts has, much like societal interest in “green” or “eco”

concepts, increased over time. This appears to correlate with reasonable evidence that participation in

green spaces and nature may potentially enable wide-ranging health benefits (Soga et al., 2020; Twohig-

Bennett & Jones, 2018) and has led to the modern conceptualization of green prescription or spending

time in nature to support wellness and mediate illness. Indeed, current generation smart phone apps have

even been developed to support this purpose (McEwan et al., 2019). Despite the centrality of these

concepts, there remain many unexplored questions about potential application and efficacy. Robinson et

al. (2020), perhaps presciently, noted, “It is important to recognize that our complex societies have

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2022

3

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 10, Iss. 1 [2022], Art. 7

evolving views, social behaviours, and health-related needs, and it is unrealistic to view spending ‘time

in nature’ as a panacea” (p. 2).

Given the relative centrality of nature and eco concepts it is perhaps not surprising that clinical

application in mental health care has been notable. For example, research has examined participation in

nature via walking to both mediate stress (Marselle et al., 2019) and reduce rumination (Lopes, 2020).

Other applications have included applied outdoor mindfulness (Djernis et al., 2019) and even using

nature participation as an adjunct to traditional return-to-work rehabilitation (Sahlin et al., 2015).

Occupational therapy has mirrored this enhanced focus on nature and eco inputs. The profession

has a lengthy and diverse history of using nature in assessment and intervention and, in particular, via

gardening and horticulture (Wagenfeld & Atchison, 2014). This has included, but not been limited to,

supporting participant well-being and inclusion (Diamant & Waterhouse, 2010); considering

participation impacts for urban office workers (Schefkind et al., 2019); and accounting for the unique

influence and impact of spirituality (Unruh, 1997; Unruh & Hutchinson, 2011). Interdisciplinary work,

involving occupational therapy inputs, has also been published in application of gardening and

horticulture in supporting incarcerated females (Toews et al., 2018) and in several design applications in

correctional settings (Toews et al., 2020; Wagenfeld & Winterbottom, 2021).

The use of nature, and horticulture in particular, in supporting care for varied conditions has also

informed the occupational therapy literature. Among such work are studies that consider the impact of

therapy involving nature application and sensory garden design for individuals with autism spectrum

disorders (Singley et al., 2016; Wagenfeld et al., 2019). Design of outdoor spaces for individuals with

PTSD has also been specifically considered (Wagenfeld et al., 2013).

Several studies have specifically noted the impact of horticulture therapy in mental illness.

Sempik et al. (2014) identified positive changes in social interaction scoring following such

participation. Kam and Siu (2010) reported significantly decreased anxiety, depression, and stress

following a short (2 week) participation in a structured horticultural activity program. Cipriani et al.

(2018) reported positive outcomes from participation in a greenhouse program, including feelings of

accomplishment for participants. Summary analysis via systemic review shows participation in nature

via horticulture therapy to “improve client factors and performance skills” (Cipriani et al., 2017, p. 47).

The Forensic Mental Health Context

The built forensic mental health environment is secure and supports a somewhat externally

structured social and participatory environment (Manual of Operating Guidelines, 2019). Security

measures, both active and passive, further define the space and each individual’s ability to navigate in it

(Eggert et al., 2014). Often, in such designs there are purposefully constructed nature spaces or “therapy

courtyards” and interior spaces offering enhanced natural light exposure (Behavioral Healthcare, 2015).

Immersive and self-determined participation outdoors and in nature, as may be common for non-

hospitalized individuals, is not typically viable or available in those settings (Heard et al., 2015).

While modern facility design compassionately prioritizes purpose-built nature courtyards, access

to natural light, and enhanced views of nature, these offer neither an immersive nor a community-

consistent opportunity for normative personal interaction with nature (Karlin & Zeiss, 2006; Sine &

Hunt, 2009). Helsel (2018), in the context of providing spiritual care, has indicated that “land and person

are tied up in an inextricable relationship” (p. 23). It is that relationship that inspired the ecospirituality

group and this study.

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol10/iss1/7

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.1708

4

Heard et al.: Ecospirituality in forensic mental health

This qualitative study considers the research question: What is the meaning and experience

associated with participating in the ecospirituality group for persons with serious and persistent mental

illness who reside in a forensic mental health setting

Method

This study employed a qualitative research method that is consistent with Interpretative

Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) in supporting data analysis and related coding (Smith, et al., 2009).

This approach seemed the most reasonable as the purpose of this study was to enable some

understanding of the experience and meaning of immersive and autonomous participation in nature

spaces for individuals affiliated with a forensic mental health facility (Creswell, 2007; Smith et al.,

2009). Smith (2011) has identified that “IPA is concerned with the detailed examination of personal

lived experience, the meaning of experience to participants and how participants make sense of that

experience” (p. 9). Prior to implementation of the study, institutional approval was obtained from the

Research Ethics Board at the University of Western Ontario.

Participants

IPA is “an idiographic approach, concerned with understanding particular phenomena in

particular contexts, IPA studies are conducted on small sample sizes” (Smith et al., 2009, p. 49). In this

study, a process was put in place to obtain a sample consistent with an IPA approach. First, potential

participants were identified by the group facilitators (occupational therapist and spiritual care

professional). Following identification, the actual recruitment, consent, and interview process was

facilitated by a third member of the research team, occupational therapist Jared Scott. Scott was a

member of the community mental health team affiliated with the hospital. It is notable that this clinician

and research team member did not have any role in the actual facilitation of the ecospirituality group.

Scott also did not have any clinical contact with any of the participants prior to initiation of the

recruitment, consent, and interview processes. Application of a recruitment and consent process of this

nature mediated potential for coercion and enhanced the potential credibility of the data set. Given this

context and approach, nine (n = 9) individuals residing at a large forensic mental health facility in

Ontario, Canada, were recruited for participation.

In effecting of the above plan, individuals who indicated potential interest in participation were

initially met by the co-investigator responsible for recruitment, consent, and interview. At that time, a

letter of information was provided and follow-up arranged regarding study related questions. Following

this process, informed consent could be obtained. It is notable that no payment, benefits, or other

incentives were provided to any participant. While this approach to recruitment did, potentially, enable a

convenience sample, it is important to note that research consistent with IPA requires both purposive

and homogeneous sampling (Smith et al., 2009).

In working with the sample, an inclusion and exclusion criteria consisting of several parts was

applied. The first component of the inclusion criteria required that all participants be persons with a

diagnosis of serious and persistent mental illness and reside at the Southwest Centre for Forensic Mental

Health Care under the jurisdiction of the Ontario Review Board secondary to their being found not

criminally responsible because of commission of a serious criminal offense. Second, all participants

included in the research must have participated in the Occupational Therapy/Spiritual Care

Ecospirituality group program. In terms of exclusion criteria, any participant could be excluded from the

study if the assessment of their clinical treatment team and/or the study investigators determined they

could not safely participate.

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2022

5

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 10, Iss. 1 [2022], Art. 7

The participants in this study were representative of the demographic characteristics of patients

at the hospital. The sample (n = 9) was comprised of seven males and two females, and this was broadly

consistent with gender ratios in the facility at the time of study completion. In terms of age, the sample

ranged between 32 and 67 years with a mean age of 51.6 years and a median age of 54 years. Tenure in

the forensic mental health system ranged between 2.5 and 16 years with a mean of 8.0 years. The sample

was diagnostically diverse with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and delusional

disorder representing the majority of the primary diagnoses.

Procedures

The participants in the study took part in a group called the ecospirituality group. This group was

supported once per week over a 16-week period with a +/- 120 min duration. The group was facilitated

by occupational therapy and/or spiritual care staff at each session with support from hospital nursing

staff, as clinically indicated, in considering forensic mental health responsibilities to the Ontario Review

Board. This approach enabled forensic client attendance at various nature and green spaces in the

community accessible to the Southwest Centre for Forensic Mental Health Care. While forensic

responsibilities were taken into account, the participants were maximally enabled to experience the

nature setting as autonomously as possible (i.e., group facilitators maintained observation of participants

over lines of sight enabling, typically, several thousand square meters, or more, for individuals to

independently access). In application, this enabled the participants to experience the nature settings via

their own preferences. This meant that individual participants could choose to access the nature space

independently and to sit quietly and reflectively on their own. It also meant that individuals might

choose to sit with peers or to walk some distance with them apart from other group members. Each

individual participant was granted the agency to choose how they wished to participate and, accordingly,

to define and narrate their own unique experience. At the conclusion of each group session spiritual care

or occupational therapy staff supported a short group reflection exercise of +/- 15 min. Participation in

the reflection was voluntary, not recorded, and included three questions:

• How was this experience for you?

• What did you notice (both internally, thoughts and feelings, and around you, externally)?

• What will you take away from this experience?

Data Collection

After consent was obtained and documented, a brief interview with each participant was

undertaken. This interview occurred in the secure hospital setting at a time and location of the

participant’s choosing and was facilitated by co-investigator Scott. The interview consisted of the

collection of limited demographic information and several standardized questions. Responses were

documented, verbatim, onto the interview form. The interview form did not contain any data that could

specifically identify the research participant.

Standardized questions on the interview form related specifically to participation in the

Occupational Therapy/Spiritual Care Ecospirituality group. They read as follows:

• How would you describe the experience of participating in the Occupational Therapy/Spiritual

Care Ecospirituality group?

• How did you feel while participating in the Occupational Therapy/Spiritual Care Ecospirituality

group?

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol10/iss1/7

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.1708

6

Heard et al.: Ecospirituality in forensic mental health

• How did participation in the Occupational Therapy/Spiritual Care Ecospirituality group impact

or affect your stay in the hospital?

Interview participation time ranged from +/- 25 min on the low end to +/- 60 min in total. The

transcribed data from each interview ranged between 2 and 4 pages.

Data Analysis

The collected data was immediately transcribed following the completion of all nine interviews.

A coding process was then initiated. The coding team included the principal investigator, a spiritual care

co-investigator, and a staff social worker. The first step of the coding process was completed using an

editing style of analysis whereby each coder independently analyzed the transcribed interview data and

emergent themes were identified (Jongbloed, 2000; Smith & Osborn, 2008). The three members of the

coding team then met to collaboratively determine overarching or superordinate themes. After reaching

agreement on definitions for each of the superordinate or overarching themes, these were tested for

consistency. Accordingly, coding team members independently coded one transcript using the final

coding scheme and definitions. Final coding agreement was found to be 87.1%.

Trustworthiness

Rodham, Fox, and Doran (2015) have published specifically on the concept of analytical

trustworthiness in IPA. They note that, “typically authors explain how they conduct interpretative

phenomenological analysis (IPA), but fail to explain how they ensured that their analytical process was

trustworthy” (p. 59). Aware of Rodham et al.’s (2015) work, our team has prioritized the same concepts

highlighted in their article, including a sensitivity to context, a focus on rigor, evident transparency, and

documentation of impact.

Rodham’s team focuses on a process that advocates data coding at a team level (consistent with

our own). Rodham’s team advocates that all analysts participate in listening to the recordings (our team

transcribed the data and our analysts reviewed all of that content). Second, they advise sharing of any

fieldwork notes made from each interview (our team included this content, as indicated). Third, they

advise some inclusion of reflexive content in transcripts (our team specifically named our approaches to

trustworthiness, provided a rationale for the same, and maintained a field journal). Finally, Rodham’s

team “emphasize the importance of establishing a supportive environment where colleagues engaged in

a shared analysis of the data can question and critically engage in one another’s interpretations” (p. 69).

Our research team takes these processes seriously. Using multiple coders on our teams from

different professions and backgrounds enabled the shared analysis Rodham et al. (2015) advocate. Our

team, using three professionally diverse coders, identified that this approach supports triangulation by

theory and perspective (Hammell & Carpenter, 2000). We also used peer review as “this enables a

further instance of triangulation” (Hammell & Carpenter, 2000, p. 111). Perhaps most importantly, our

team employed member checking, as this supports “enhancing credibility and the ability for participants

to meaningfully contribute to the research process” (Doyle, 2007, p. 894). Finally, we will securely store

our records for 15 years enabling our team the ability to revisit the content, if indicated.

Results

The data analysis supported the identification of several unique themes for each interview

question. These themes described the meaning and experience associated with participating in the

ecospirituality group program for persons residing at a forensic mental health care facility.

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2022

7

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 10, Iss. 1 [2022], Art. 7

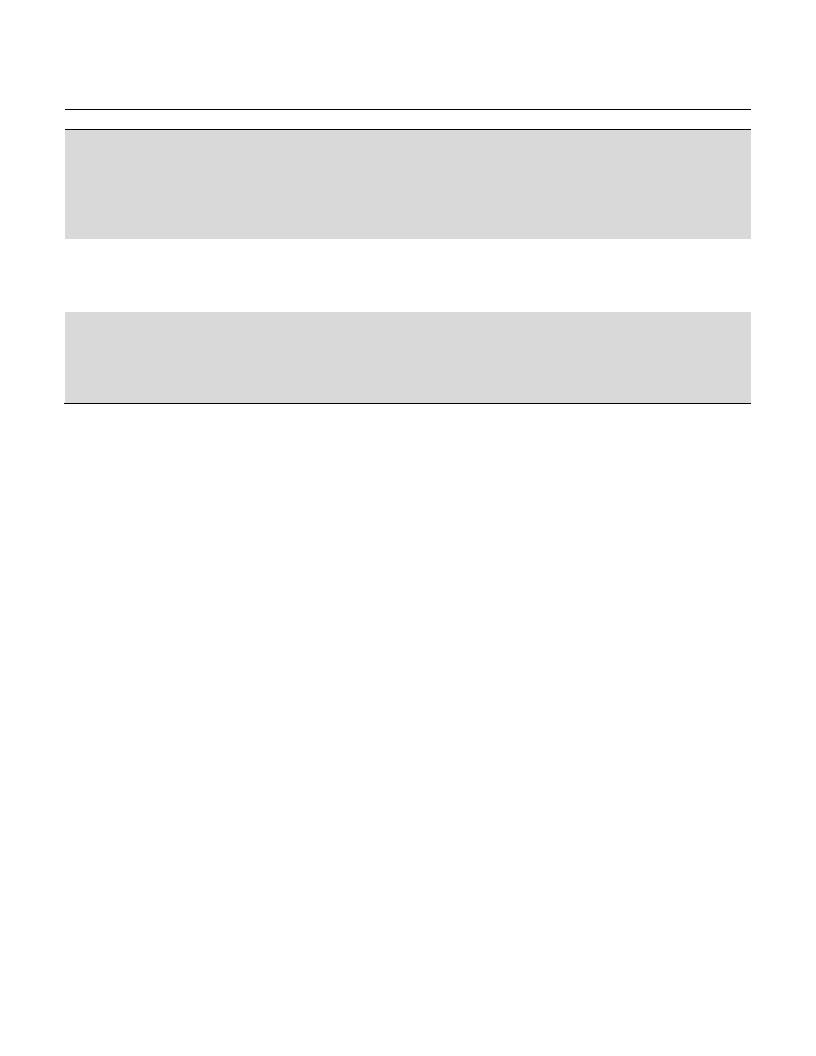

Table 1

Superordinate and Overarching Themes

Question

How would you describe the experience

of participating in the Occupational

Therapy and Spiritual Care

Ecospirituality group?

Superordinate/Overarching Themes

• A sense of communion and connection with nature

• An opportunity for open and unguarded reflection and

relaxation

• A strengthened human connection and a sense of

camaraderie though shared experience in nature

How did you feel while participating in • A sense of peace, comfort, serenity, and accomplishment

the Occupational Therapy and Spiritual • A feeling of freedom, autonomy, and personal agency

Care Ecospirituality group?

• A connection to the personally sacred

How did participation in the

Occupational Therapy and Spiritual

Care Ecospirituality group impact or

affect your stay in the hospital?

• Regenerative and restorative participation

• Easy and accessible stress relief

• Supported resiliency and meaningful connection with

others

The Experience of Ecospirituality

The participants described several outcomes related to their participation in the Occupational

Therapy/Spiritual Care Ecospirituality group. An overarching theme described the experience as

enabling a sense of communion and connection with nature. One participant, in positing this view,

stated: “I describe it as being surrounded by nature. It’s always interesting to get fresh air and to observe

the animals and trees and everything to do with nature” (Participant 3). Several other participants

similarly reflected this type of immersive and personal connection with nature: “the entire time I was out

in nature and things were balanced at the time. It was a very precious moment for me. I was out

observing nature being one with nature” (Participant 9). Another noted, succinctly: “some people need it

more than others; you feel like you’re at home” (Participant 1).

While connection with nature was identified as important, the participants in the group also

identified the opportunity for unguarded reflection and relaxation. One participant noted that the group

enabled them, stating: “You can think about you. It’s time for that and it’s nice because it’s peaceful”

(Participant 8). A second followed this line of thinking, noting: “I was absorbing all the positive energy

given to me by the surroundings I was in, by the people I was with. Everything was very organized and

put together so I could just be and think and not worry” (Participant 9). Several of the participants

reported on the opportunity to be in nature: “it was relaxing” (Participant 7) and “I love the outdoors, I

like to be outdoors, it helps me think” (Participant 5).

Being in nature and sharing an experience with a group of peers enabled the participants to

identify feelings of an enhanced human connection and a sense of camaraderie. A participant spoke to

this shared experience: “Overall, very good. It was relaxing. I think there was a bonding between

individuals who went, to take a look at nature and reflect on it. To discuss it as a group with other people

in a group setting” (Participant 4). Others reflected positively on the supportive facilitation: “I also find

it a very friendly atmosphere with your fellow patients and the staff. It’s very relaxing and I enjoy the

camaraderie we have together” (Participant 3). Another similarly noted: “it was very serene and the

spiritual care staff was inspiring in their discussions about nature. It was an enjoyable experience”

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol10/iss1/7

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.1708

8

Heard et al.: Ecospirituality in forensic mental health

(Participant 6). A participant summarized their feelings of the group influence, noting: “it is different

than just going for a walk because you are with the group. You can be with other people and think about

things. You can share with others and talk to them about your thoughts” (Participant 8).

The Effect of Ecospirituality

A key question in this study looked at how the participants considered the effect of participation

or how they felt while immersed in nature via a supported group context. The participants identified

themes that spoke to important personal outcomes. The first of these related to feeling a sense of peace,

comfort, serenity, and accomplishment. These findings were reflected in various personal narratives: “I

was going through a pretty rough time in my life at the time so it felt pretty good. Just the staff and

being in the environment, and being around people who care about you. It was really good” (Participant

2). Another spoke to the relevance of being outside: “when I’m outside I am comforted. I feel good

when I’m outside or in nature. Both in a group or own my own. It’s about being outside – it makes me

feel better” (Participant 6). The peaceful nature of the outdoors spoke to some participants: “it was a lot

more therapeutic being outside. Being somewhere special” (Participant 2). Finally, a participant spoke

specifically to the personal value of participation: “you learn stuff and I feel like you have accomplished

something. It’s a good feeling” (Participant 1).

Each participant narrative was unique but spoke to their connection with nature and with the

group:

When you walk along with other people you have to carry on a conversation or you can walk

along in silence, too. They say silence is golden. I like the company of walking with others and I

feel like that’s assistance, too. But I also want to do things on my own and be independent.

(Participant 3)

The opportunity to participate independently, with peers or staff, informed some of the participants: “we

all shared our ideas and thoughts about nature and the spirituality of nature and the balance of the

universe and I learned a lot” (Participant 9). Another indicated: “when I walk by myself I say a few

poems to myself or pray a little bit” (Participant 3). One participant summarized their experience:

“Peaceful. The different venues, for example, we saw turtles and saw a crane and different animals and

insects and it was a great experience to share that with people. I really enjoyed it” (Participant 4).

The Impact of Ecospirituality

The participants in the Occupational Therapy/Spiritual Care Ecospirituality group discussed the

impacts of the group and how it affected their stay in the hospital. These impacts, it seems, were multi-

faceted and spoke to three fairly discrete themes. The first of these spoke to the concept that

participation in the group was both regenerative and restorative. One participant noted:

I do look forward to the group being in nature but sometimes I have to be persuaded to go.

Sometimes I feel aches and pains through my body and I have to be careful so sometimes I’m not

sure if I want to go. But when I go, I always feel better inside. (Participant 3)

Another participant reflected: “well, it was good to get out of the hospital. To go for a ride in the van

and I felt good after we got back. The walks made me feel good” (Participant 7). Finally, a participant

spoke to a more personal impact: “it created memories for me because I didn’t know the forensic

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2022

9

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 10, Iss. 1 [2022], Art. 7

hospital offered groups like that. I was very happy to get out and get to the outside world, in nature,

more” (Participant 9).

Beyond supporting regenerative and restorative outcomes, the participants’ experiences also

spoke to an overarching theme of easy and accessible stress relief. The participants described this

content in varied ways with some quite explicitly identifying this feature of the group:

I feel less stressed out. The time is helpful to break my daytime down. I feel more rested.

Overall, it was a good experience. Everyone in the hospital could do it and it would help them. It

is nice to be outside the hospital. (Participant 8)

Others were less explicit but noted a similar sentiment: “it made me a lot happier. It brought me back to

myself a little bit and I was able to focus on myself more” (Participant 2). Some participants spoke to

more of a long-term applicability in terms of stress relief and application of eco concepts in their own

day-to-day living: “I can go outside and find a quiet place or park or trees and walk on my own to help

me calm down, to just be out in the open” (Participant 7). Other participants spoke to more immediate

application, noting: “You get rid of pressure. In your body and in your head. You get rid of all the stress,

all your pressures. You feel good about yourself. You relieve the stress” (Participant 5).

The final overarching theme in terms of impact related to how participation supported resiliency

and connection to others. Several of the participants spoke to a more practical view of connection and

related resiliency development: “It’s good programs. It helps people connect with each other in new and

different ways” (Participant 1). Another participant reflected this same concept: “In the group you are

not by yourself, you have other people with you who experience the same thing, nature, and they can

share that experience with you” (Participant 7). Other participants took a broader view of the group and

related connection and resiliency outcomes:

It changed my memories of the hospital. It built up my emotions and trust with the hospital. It

showed me there was some sort of care and connection to nature and the world. To make people

feel valued and connected. To have hope and faith, to recognize how we celebrate that – our

connection to nature as people, as humans. (Participant 9)

Perhaps most importantly, the group supported a real connection between peers: “it was something that I

talked to and with my peers about. I would tell other people where we went and what we saw and the

different questions that were asked of us and my reflections” (Participant 4).

Discussion

Ecospirituality Group Participation in Context

The results of this study identify a number of compelling narratives. Among these, the

participants in the Occupational Therapy/Spiritual Care Ecospirituality group described an experience

that enabled both personal autonomy and self-determinism. They described this participation experience

as enabling success and feelings of achievement. This would be consistent with those elements of

empowerment that are a core concept of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) vision of health

promotion. Indeed, the WHO (2010) note that:

For the individual, the empowerment process means overcoming a state of powerlessness and

gaining control of one’s life. The process starts with individually defined needs and ambitions

and focuses on the development of capacities and resources that support it. The empowerment of

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol10/iss1/7

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.1708

10

Heard et al.: Ecospirituality in forensic mental health

individuals is intended to help them adopt self-determination and autonomy, exert more

influence on social and political decision-making processes and gain increased self-esteem. (p. 1)

The participants spoke plainly to these concepts when describing the participation experience of the

ecospirituality group. This concept of empowerment appears particularly relevant in the forensic mental

health milieu where opportunities for autonomy and self-determination in occupational participation

cannot always be part of the recovery journey secondary to those legal aspects that inform care (Ontario

Review Board, 2011).

In reviewing the outcomes of this study in consideration of current literature related to mental

health care, it appears that many existing approaches do not tend toward privileging the autonomy and

personal agency of each individual. Rather, it appears that much of this work is targeted toward enabling

the client to meet some externally defined wellness or discharge related criteria. Hamilton (2017)

describes this situation as secondary to “deficit-centric discourses” defining care interactions (p. 2). As

an example of this concept, the high volume of literature supporting group interventions related to social

skill development, anger management, and assertiveness speak directly to this narrative. This is not to

minimize the potential clinical relevance, perhaps, of such groups, but it is compelling to consider the

influence of externally defined, deficit informed care.

For individuals residing in secure mental health facilities, or secure settings more generally,

concepts of autonomy, determinism, and success experience may not always be common informers in

care participation (Heard et al., 2015). As such, participation in the ecospirituality group, as described in

this study, does mark a fairly significant departure from the existing deficit informed hegemony. For

health care providers considering this type of group it may feel like there is some tension in supporting a

more open-ended participant-defined experience versus supporting an outcome driven group answerable

to some type of deficit. If such tensions can be accepted, then the ecospirituality group offers a

particularly practical and cost-effective approach to care that speaks to real-world applicability in terms

of leisure participation, relaxation, stress relief, and connection with the personally sacred.

Ultimately, health care providers have at their disposal a domain, nature, in which spirituality

and spiritual health can be nurtured and promoted. This domain, according to Fisher (2011), moves

“beyond care and nurture for the physical and biological, to a sense of awe and wonder…[and]…for

some…the notion of unity with the environment” (p. 22). Fisher argues that spiritual health is the

“fundamental dimension of people’s overall health and well-being, permeating and integrating all the

other dimensions of health,” describing spiritual health as a “dynamic state of being, reflected in the

quality of relationships that people have in up to four domains of spiritual well-being: personal

domain…communal domain…environmental domain… transcendental domain” (p. 17). To assist in

explaining the interrelationship between the four domains, Fisher refers to the notion of progressive

synergism, stating it “implies that the more embracing domains of spiritual well-being not only build on,

but also build up, the ones they include” (p. 23). The authors of this study did observe multiple

occurrences where a participant’s sense of self, connection to others, and to the personally sacred were

maximized because of their accessing local nature spaces and their capacity to self-author these

experiences.

Implications for Practice

This study describes the significant impacts that access to natural environments, and the ability

to self-author those experiences, can have in the lives of individuals residing in a forensic mental health

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2022

11

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 10, Iss. 1 [2022], Art. 7

system. While the sample was comprised of individuals affiliated with a forensic mental health hospital,

it may be reasonable to posit that the most powerful impacts of participation would be optimal in any

care setting or context. Indeed, the potential to support feelings of freedom, autonomy, personal agency,

stress relief, and relaxation is a compelling driver for any clinical work. Given that narrative, the results

of this study identify several important implications for mental health practice and, perhaps, clinical

practice more generally:

• Enabling immersive experiences in nature supports participants to access, learn, and potentially

replicate cost-efficient opportunities for stress relief.

• Unlike deficit informed approaches, these experiences (where individuals have the autonomy to

determine the scope of their participation in the nature space) privilege the personal agency,

experience, and wisdom of each participant.

• The results of this study speak to the centrality of nature as an informer in care. At a practical

level it appears that enhancing access to such spaces may have a significant and positive impact

on occupational performance, wellness, and the personal experience of spirituality. Accordingly,

it may be relevant to consider how accessible nature and immersive nature spaces might play an

enhanced role in the care paradigm via building and facility design, supported community

access, or programmatic focus.

• Participation in ecospirituality group creates space or allows for theological and spiritual

reflection and enables the development of personal wisdom.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

It is important to note that this study does have limitations. First, while the sample correlates

fairly reasonably with the demographic norms for the facility, the study did occur at a single forensic

hospital in Ontario, Canada. This sample size, at n = 9, is relatively small and, at some level, this may

limit potential generalizability. That said, it should be noted that in employing a design consistent with

IPA, it is required that the sample is more or less homogeneous and purposefully selected (Smith et al.,

2009). In considering future research, further study may be compelling in considering the varied

potential benefits that self-authored and autonomous participation in nature might enable for different

clinical populations. It is not difficult to forecast that this type of easily accessible and inexpensive

spirituality-focused intervention may well have clinical applicability with a wide array of clinical

populations.

Conclusion

The outcomes of this study speak to the centrality of personal interaction with nature and its

implication for health, wellness, and connection to the personally sacred. The opportunity to narrate this

interaction via personal agency in those nature spaces, and to allow what Kirkbride (1880) might refer to

as “the full benefit of them,” also appears relevant (p. 7). In a practical way, supporting and enabling

immersive personal interaction with nature for those who are mentally ill, incarcerated, or otherwise

vulnerable may offer an important pathway to wellness. Compellingly, it appears that this pathway was,

historically, quite explicitly acknowledged and accounted for in the works of Tuke (1815) and Kirkbride

(1880) and in the practice of Truby King (Stock & Brickell, 2013). Perhaps the wisdom of past

generations regarding the value of immersive participation and personal autonomy in natural

environments may hold a key to future healing, wellness, occupational performance, and experience of

the personally sacred.

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol10/iss1/7

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.1708

12

Heard et al.: Ecospirituality in forensic mental health

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014).

Occupational therapy practice framework

domain and process. American Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 68 (Suppl. 1), S1–S48.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.682006

Behavioral Healthcare. (2015). Design showcase:

Southwest centre for forensic mental health care.

http://cdn.coverstand.com/36947/263804/7d4c19

e46171f890787e0fc92513bac962d80975.1.pdf

Bielinis, E., Jaroszewska, A., Lukowski, A., & Takayama,

N. (2019). The effects of a forest therapy

programme on mental hospital patients with

affective and psychotic disorders. International

Journal of Environmental Research and Public

Health, 17(1), 118.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010118

Charland, L. C. (2007). Benevolent theory: Moral

treatment at the York retreat. History of

Psychiatry, 18(1), 61–80.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0957154X07070320

Cipriani, J., Benz, A., Holmgren, A., Kinter, D.,

McGarry, J., & Rufino, G. (2017). A systematic

review of the effects of horticultural therapy on

persons with mental health conditions.

Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 33(1),

47–69.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2016.1231602

Cipriani, J., Georgia, J., McChesney, M., Swanson, J.,

Zigon, J., & Stabler, M. (2018). Uncovering the

value and meaning of a horticulture therapy

program for clients at a long-term adult inpatient

psychiatric facility. Occupational Therapy in

Mental Health, 34(3), 242–257.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2017.1416323

Codinhoto, R. (2017). Healing architecture. In R. Cooper

& E. Tsekleves (Eds.), Design for health (p.

111–156). Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research

design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd

ed.). Sage.

Delaney, C., & Barrere, C. (2009). Ecospirituality: The

experience of environmental meditation in

patients with cardiovascular disease. Holistic

Nursing Practice, 23(6), 361–369.

https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0b013e3181bf381c

Diamant, E., & Waterhouse, A. (2010). Gardening and

belonging: Reflections on how social and

therapeutic horticulture may facilitate health,

wellbeing and inclusion. The British Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 73(2), 84–88.

https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X1265806279

3924

Djernis, D., Lerstrup, I., Poulsen, D., Stigsdotter, U.,

Dahlgaard, J., & O’Toole, M. (2019). A

systematic review and meta-analysis of nature-

based mindfulness: Effects of moving

mindfulness training into an outdoor natural

setting. International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, 16(17), 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173202

Doyle, S. (2007). Member checking with older women: A

framework for negotiating meaning. Health Care

for Women International, 28(10), 888–908.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330701615325

Egan, M., & Delaat, M. (1994). Considering spirituality in

occupational therapy practice. Canadian Journal

of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 95–101.

https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749406100205

Eggert, J. E., Kelly, S. P., Margiotta, D. T., Hegvik, D.

K., Vaher, K. A., & Kaya, R. T. (2014). Person–

Environment interaction in a new secure forensic

state psychiatric hospital. Behavioral Sciences &

The Law, 32(4), 527–538.

https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2127

Fisher, J. (2011). The four domains model: Connecting

spirituality, health and well-being. Religions, 2,

17–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2010017

Hamilton, S. A. (2017). Clients’ experiences of recovery-

oriented care for schizophrenia: A qualitative

research study [Unpublished doctoral

dissertation]. Duquesne University.

Hammell, K. W., & Carpenter, C. (2000). Evaluating

qualitative research. In K. W. Hammell, C.

Carpenter, & I. Dyck (Eds.), Using qualitative

research: A practical introduction for

occupational and physical therapists (pp. 107–

119). Churchill Livingstone.

Hansen, M. M., Jones, R., & Tocchini, K. (2017).

Shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy:

A state-of-the-art review. International Journal

of Environmental Research and Public Health,

14(8), 851.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080851

Heard, C. P., Scott, J., & Yeo, R. S. (2015). Walking the

labyrinth: Considering mental health consumer

experience, meaning making, and the

illumination of the sacred in a forensic mental

health setting. Journal of Pastoral Care &

Counseling, 69(4), 240–250.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1542305015616102

Helsel, P. B. (2018). Loving the world: Place attachment

and environment in pastoral theology. Journal of

Pastoral Theology, 28(1), 22–33.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10649867.2018.1475977

Jongbloed, L. (2000). Choosing the methodology to

explore the research. In K. W. Hammell, C.

Carpenterm & I. Dyck (Eds.), Using qualitative

research: A practical introduction for

occupational and physical therapists (pp. 13–

21). Churchill Livingstone.

Jordan, M. (2015). Nature and therapy: Understanding

counselling and psychotherapy in outdoor

spaces. Routledge.

Kam, M., & Siu, A. (2010). Evaluation of a horticultural

activity programme for persons with psychiatric

illness. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 20(2), 80–86.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-1861(11)70007-9

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature:

Toward an integrative framework. Journal of

Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Karlin, B. E., & Zeiss, R. A. (2006). Environmental and

therapeutic issues in psychiatric hospital design:

Toward best practices. Psychiatric Services,

57(10), 1376–1378.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.57.10.1376

Kirkbride, T. S. (1880). On the construction, organization

and general arrangements of hospitals for the

insane with some remarks on insanity and its

treatment. (2nd ed.). J.B. Lippincott.

Law, M. (2002). Participation in the occupations of

everyday life. The American Journal of

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2022

13

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol. 10, Iss. 1 [2022], Art. 7

Occupational Therapy, 56(6), 640–649.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.56.6.640

Lincoln, V. (2000). Ecospirituality: A pattern that

connects. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 18(3),

227–244.

https://doi.org/10.1177/089801010001800305

Lopes, L. (2020). Nature can get it out of your mind: The

rumination reducing effects of contact with

nature and the mediating role of awe and mood.

Journal of Environmental Psychology, 71,

101489.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101489

Manual of Operating Guidelines – Provincial Psychiatric

Hospitals. (1995). Wording of custodial

disposition orders.

http://www.orb.on.ca/scripts/en/legal/psych-

hosp-guidelines.pdf

Marselle, M., Warber, S., & Irvine, K. (2019). Growing

resilience through interaction with nature: Can

group walks in nature buffer the effects of

stressful life events on mental health?

International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, 16(6), 986.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060986

McEwan, K., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., Ferguson, F.,

& Brindley, P. (2019). A smartphone app for

improving mental health through connecting

with urban nature. International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public

Health, 16(18), 3373.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183373

Newbigging, C., Stewart, D., & Baptiste, S. (2017).

Spirituality in occupational therapy: Enhancing

our practice through the use of the four domains

model. Occupational Therapy Now, 19(1), 13–15.

Oh, B., Lee, K. J., Zaslawski, C., Yeung, A., Rosenthal,

D., Larkey, L., & Back, M. (2017). Health and

well-being benefits of spending time in forests:

Systematic review. Environmental Health and

Preventive Medicine, 22(1), 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-017-0677-9

Ontario Review Board. (2011). About us.

http://www.orb.on.ca/scripts/en/about.asp#infor

mation

Pargament, K. I. (2011). Spiritually integrated

psychotherapy: Understanding and addressing

the sacred. The Guilford Press.

Perriam, G. (2015). Sacred spaces, healing places:

Therapeutic landscapes of spiritual significance.

Journal of Medical Humanities, 36(1), 19–33.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-014-9318-0

Robinson, J., Jorgensen, A., Cameron, R., & Brindley, P.

(2020). Let nature be thy medicine: A

socioecological exploration of green prescribing

in the UK. International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public Health,

17(10), 1–24.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103460

Rodham, K., Fox, F., & Doran, N. (2015). Exploring

analytical trustworthiness and the process of

reaching consensus in interpretative

phenomenological analysis: lost in transcription.

International Journal of Social Research

Methodology, 18(1), 59–71.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2013.85236

Schefkind, S., Hock, N., & Wagenfeld, A. (2019).

Measuring emotional response to a planting

activity for staff at an urban office setting: A

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol10/iss1/7

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.1708

pilot study. The Open Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 7(2), 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1532

Sahlin, E., Ahlborg, J., Tenenbaum, A., & Grahn, P.

(2015). Using nature-based rehabilitation to

restart a stalled process of rehabilitation in

individuals with stress-related mental illness.

International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, 12(2), 1928–1951.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120201928

Sempik, J. (2010). Green care and mental health:

Gardening and farming as health and social

care. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 14(3),

15–22. https://doi.org/10.5042/mhsi.2010.0440

Sempik, J., Rickhuss, C., & Beeston, A. (2014). The

effects of social and therapeutic horticulture on

aspects of social behaviour. The British Journal

of Occupational Therapy, 77(6), 313–319.

https://doi.org/10.4276/030802214x1401872313

8110

Sine, D. M., & Hunt, J. M. (2009). Following the

evidence toward better design. Behavioral

Healthcare, 29(7), 45.

Singley, K., Griner, C., DeDominic, T., & Wagenfeld, A.

(2016). Therapy in the natural environment:

Growing solutions for autism spectrum

disorder. OT Practice, 21(11), 21–24.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009).

Interpretative phenomenological analysis:

Theory, method and research. Sage.

Smith, J. A. (2011). Evaluating the contribution of

interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health

Psychology Review, 5(1), 9–27.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2010.510659

Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2008). Interpretative

phenomenological analysis. In J. Smith (Ed.),

Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to

research methods (pp. 53–80). Sage.

Soga, M., Evans, M., Tsuchiya, K., & Fukano, Y. (2020).

A room with a green view: The importance of

nearby nature for mental health during the

COVID-19 pandemic. Ecological Applications,

e2248–e2248. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2248

Song, C., Ikei, H., & Miyazaki, Y. (2016). Physiological

effects of nature therapy: A review of the

research in japan. International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public Health,

13(8), 781.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13080781

Stock, P. V., & Brickell, C. (2013). Nature's good for you:

Sir Truby King, Seacliff Asylum, and the

greening of health care in New Zealand, 1889–

1922. Health and Place, 22, 107–114.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.03.002

Summers, J. K., & Vivian, D. N. (2018). Ecotherapy – A

forgotten ecosystem service: A review. Frontiers

in Psychology, 9, 1389.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01389

Toews, B., Wagenfeld, A., & Stevens, J. (2018). Impact

of a nature based intervention on incarcerated

women. International Journal of Prisoner

Health, 14(4), 232–243.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-12-2017-0065

Toews, B., Wagenfeld, A., Stevens, J., & Shoemaker, C.

(2020). Feeling at home in nature: A mixed

method study of the impact of visitor activities

and preferences in a prison visiting room

garden. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation,

14

Heard et al.: Ecospirituality in forensic mental health

59(4), 223–246.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2020.1733165

Townsend, E., & Brintnell, S. (1990). Developing

guidelines for client-centred occupational

therapy practice. Canadian Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 57(2), 69–76.

https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749005700205

Townsend, E., & Polatajko, H. (2013). Enabling

occupation II: Advancing an occupational

therapy vision for health, well-being & justice

through occupation. CAOT.

Tuke, S. (1815). Description of the Retreat, an institution

near York, for insane persons of the Society of

Friends: Containing an account of its origin and

progress, the modes of treatment, and a

statement of cases. Pierce, Isaac.

Twohig-Bennett, C., & Jones, A. (2018). The health

benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic

review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure

and health outcomes. Environmental Research,

166, 628–637.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.030

Unruh, A. (1997). Spirituality and occupation: Garden

musings and the Himalayan blue poppy.

Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy,

64(1), 156–160.

https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749706400112

Unruh, A., & Hutchinson, S. (2011). Embedded

spirituality: Gardening in daily life and stressful

life experiences: Embedded spirituality.

Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 25(3),

567–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-

6712.2010.00865.x

Wagenfeld, A., & Atchison, B. (2014). ‘Putting the

occupation back in occupational therapy’: A

survey of occupational therapy practitioners’ use

of gardening as an intervention. The Open

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2(4), 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1128

Wagenfeld, A., Roy-Fisher, C., & Mitchell, C. (2013).

Collaborative design: Outdoor environments for

veterans with PTSD. Facilities, 31(9/10), 391–

406.

https://doi.org/10.1108/02632771311324954

Wagenfeld, A., Sotelo, M., & Kamp, D. (2019).

Designing an impactful sensory garden for

children and youth with autism spectrum

disorder. Children, Youth and Environments,

29(1), 137–152.

https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.29.1.0137

Wagenfeld, A., & Winterbottom, D. (2021). Coping on

the inside: Design for therapeutic incarceration

interventions - A case study. Work, 68(1), 97–

106. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-203360

Wilson, E. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press.

Wilson, L. (2010). Spirituality, occupation and

occupational therapy revisited: Ongoing

consideration of the issues for occupational

therapists. British Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 73(9), 437–440.

https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X1283936752

6219

WHO Regional Office for Europe, European

Commission. (2010). User empowerment in

mental health. World Health Organization.

http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0

020/113834/E93430.pdf

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2022

15