International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Article

Analysis of Urban Forest Healing Program Expected Values,

Needs, and Preferred Components in Urban Forest Visitors with

Diseases: A Pilot Survey

Kwang-Hi Park

Department of Nursing, College of Nursing, Gachon University, Incheon 21936, Korea; parkkh@gachon.ac.kr;

Tel.: +82-32-820-4204

Citation: Park, K.-H. Analysis of

Urban Forest Healing Program

Expected Values, Needs, and

Preferred Components in Urban

Forest Visitors with Diseases: A Pilot

Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public

Health 2022, 19, 513. https://

doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010513

Academic Editors: Won Sop Shin and

Bum-Jin Park

Abstract: Although the effectiveness of urban forest therapy has been studied and proven, most

people are not well aware of the positive healing effects of urban forests that are easily accessible in

daily life compared to the known healing effect of forests located outside urban areas. In addition,

there has been a study on the analysis of urban forest healing program needs in the general population,

but there is a lack of evidence on the expected values and needs of urban forest healing for people

with diseases. Therefore, this pilot survey aimed to investigate the expected values, needs, and

preferred components of urban forest healing programs in urban forest visitors with disease via an

online user survey and see if there were any differences in the purpose of the urban forest visits and

expected values of urban forest healing depending on the type of disease. The survey was conducted

on 294 urban forest visitors with diseases. About 79% of respondents agreed with the healing effects

of urban forest, however most respondents expected healing effects on mental health rather than on

physical health (“mood change” was the highest with score of 4.43/5, followed by “reliving stress”

(4.35/5) and “mental and physical stability” (4.31/5)). In addition, more than 82.0% of respondents

agreed to participate in the program if a healing program for disease was developed. The results of

the current pilot survey indicate that the purpose of the urban forest visits and expected values of

urban forest healing were largely not different by the type of disease, and people with disease had

a relatively lower awareness and lower expected values of urban forest healing effects on physical

health, but high demand for the program. Urban forest therapy programs should be developed based

on the specific clinical characteristics of the disease to maximize the effectiveness of the program.

Additionally, policies should be implemented to promote the beneficial effects of urban forest healing

not only for mental health but also for physical health.

Keywords: urban forest; disease; healing effect; survey

Received: 3 December 2021

Accepted: 31 December 2021

Published: 4 January 2022

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Copyright: © 2022 by the author.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

1. Introduction

Forest healing, which is a practice comprising of activities utilizing forests to improve

immunity, mental health and physical health has been established as a culture in South

Korea, with annual visits to forests exceeding one million in 2014 [1]. The number of visitors

to forest healing centers has rapidly increased over time to reach 76,000 in 2010, 1.15 million

in 2014, and 2.27 million 2019 in South Korea. Similarly the number of users of forest healing

programs in the country has surged to 1067 in 2009, 1.7 million in 2015, and 1.8 million

in 2019 [1]. In addition, it is predicted that the demand for forest healing will continue to

increase with time due to the escalation in environmental health related risk factors, such

as particulate matter in the air, as well as increased economic development and demand for

leisure [2–4]. However, most of the healing forests are located in the suburbs, making it

difficult to obtain healing benefits of forests in everyday life. In South Korea, most of the

national and public healing forests are located on average 90 min away from metropolitan

cities, by car. Moreover, it is particularly difficult for the mobility disabled, elderly, pregnant

women, and those with diseases affecting movement, to use the healing forests due to the

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010513

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

2 of 14

lack of accessibility [5]. In addition, the country has become an aging society with an aging

rate of 7.2% in 2000. This rate increased to 14.3% in 2018, and is forecast to rise to 42.5% by

2065, making it the highest in the world [6]. As the national population continues to age,

the interest in benefits of urban forests is also soaring. Therefore, interest in urban forests

with high accessibility is increasing [7].

Urban forests were first defined by Jorgensen in 1974 as “a specialized branch of

forestry, and it has in its objective the cultivation and management of trees for their present

and potential contribution to the physiological, sociological, and economic well-being

of urban society”. Thereafter, Deneke defined urban forestry in 1993 as “the sustained

planning, planting, protection, maintenance, and care of trees, forests, greenspace, and

related resources in and around cities and communities for economic, environmental, social,

and public health benefits for people [7]”. Preserving forest cover as urban populations

grow into surrounding rural areas, as well as trying to restore essential aspects of the urban

environment after construction, are all part of the definition. Continued growth at the

urban front increases environmental and public health concerns, as well as the possibility of

generating educational and environmental links between nature and urban people. Urban

and community forestry is composed of development of citizen engagement coupled with

aid for investment in sustained tree planting, protection, and care programs. A multitude

of definitions have been proposed over the years, but they all acknowledge that urban

forests do not end at the limits of the city.

Nowadays, the main focus of primary health care practices is the identification of

risk factors for preventing diseases and aims to improve the quality of life through this

and the prevention of chronic conditions, which is different from the past that focused

on diagnosing and treating diseases [8]. In particular, it is becoming important for most

people living in cities to establish and implement long-term care plans to promote health

as chronic diseases related to stress from their daily lives increase [9]. As such, the various

therapeutic effects of urban forests have been proven. Especially in South Korea, where

about 89% of the population lives in metropolitan areas, forest recreation and healing in

urban forests that can be easily accessible by the people are needed [10].

Many previous studies have summarized the relationship between the natural envi-

ronment and human health [11–15]. Recent trends indicate a growing interest in urban

forests, as these are seen as a mechanism to encourage physical activity, facilitate social

cohesion, and promote both psychological and physiological restoration [1,14]. Various

studies have shown the benefits of urban forest therapy programs and their effects in a

forest environment [11,12,15–17]. The Korean government is also promoting public health

by designating the living areas and surrounding lands as urban forests for healing effect on

stress caused by urban life [18]. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously develop various

healing programs and related facilities for preventing disease and health in urban forests,

and for this, the need for an evaluation of the multiple functions of urban forests, including

healing benefits, is a prerequisite.

1.1. Operational Definition of “Urban Forest”

Referring to previous studies [19–21], in this study we defined urban forests as “Trees,

forests, and greenspaces that are located within urban living area and play a plethora

of ecological and social roles in the lives of local residents”. These are limited to places

with an infrastructure for hiking trails and fitness facilities. Ecological functions include

particulate matter reduction, noise reduction, furnishing animal and plant habitats, and

providing green spaces, while social functions include exercise, rest, leisure, experience,

and education.

1.2. Healing Effects of Forest

1.2.1. General Benefits of Urban Forest

Urbanization, advancements in technology, crowding, and fast-paced life have dra-

matically decreased the time humans spend in natural surroundings. The lifestyle of people

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

3 of 14

living in cities has been shown to produce negative emotions such as depression, pain

and anxiety [22]. Ulrich, through his stress reduction theory, has described the need for

urban residents to experience nature. This explains that interaction with nature helps in

stress reduction as well as enhancing the physiological functioning of humans [11]. Forest

healing or forest therapy is one of the therapies provided by nature for improving mental

and physical health and includes many environmental factors such as landscape, phyton-

cides, sounds, lights, and negative ions [21]. Then, healing effect of urban green areas may

provide feasible health benefits, as they are easily accessible [11]. Although it is relatively

less than natural forests, the healing effects of urban forest have been proven in many

studies [23–25]. As stated by Han et al., urban forests vary from one region to another, have

several spaces and plantations as well as infrastructure for various forest activities, and

therefore, they can be utilized by urban dwellers as a ‘healing space’ [17]. Social scientists

have also established that urban forests and green spaces improve mental well-being [26].

Previous studies observed that forest healing programs in urban forests enhance

mental health such as resilience, stress reduction [17,27]. Lee et al. concluded that the

therapeutic effect of urban forest therapy on the psychological healing of middle-aged

women thought focus group interview [11]. Furthermore, another study found that urban

green space improved children’s emotional happiness and behavior resilience [28]. Urban

forests have been found to be effective not only for mental health but also for physical health

such as decreasing pulse rate, blood pressure, variability of heart rate, nervousness, tension,

depression in middle-aged and elderly subjects [12,13,15,29]. A study on the association

between urban tress and various health benefits revealed that more urban tree canopy were

mainly associated with lower incidence of obesity, high blood pressure, asthma, and type

2 diabetes [30].

1.2.2. Healing Effects of Forest Therapy for Chronic Diseases

Forest healing is not considered as a remedy for diseases, rather it’s a healing activity

that aids in the maintenance of patients’ health and the enhancement of both physiological

and psychological functions [1]. As such, many studies have been conducted that says

that the healing effects of forest has a positive effect on various types of chronic diseases.

Recent study have shown that forest therapy improves depression and anxiety in addition

to reducing blood pressure by stabilizing the autonomic nervous system in elderly subjects

with dementia [20]. Lee et al. examined the biophysical and psychosocial effects of different

types of forest on middle-aged women with metabolic syndrome and found that wild

forest had a positive effect on insulin responses, pulse rate, oxidative stress markers, and

stress hormone level [31]. Chun et al. also demonstrated that forest therapy was beneficial

for treating depression and anxiety symptom in patients with chronic stroke; therefore,

forest therapy can be specifically used for chronic patients who cannot receive standard

treatment [32]. In addition, many studies have shown that forest healing is effective in

cardiopulmonary disease patients [33–35]. Direct evidence was provided by Mao et al.

in favor of forest therapy being beneficial for patients with chronic heart failure and

therefore it was considered that it has the potential to be used as an adjuvant therapy

for cardiovascular disorders [34]. With regard to cancer patients, previous studies have

stated that forest healing therapy not only increased physiological factors such as natural

killer cell activity [36–39], but also psychological status such as depression, anxiety, and

sleep quality [36,40–42].

1.3. Aim of the Study

Despite the studied and proven effectiveness of urban forest therapy, most people

are not completely aware of the positive healing effects of urban forests compared to the

healing effects of forests located outside urban areas.

Employing an Evidence-based practice (EBP) which is a problem-solving strategy

that incorporates the best evidence of well-designed studies, experts’ opinion and patients’

value or preference is important to be established as a healthcare program which can lead

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

4 of 14

to better patient outcome for individuals with diseases [43]. A lot of evidence already

supports that forest healing program has a positive effect on improving physiological and

psychological functions and many experts assured that the importance of forest healing

program should be highlighted. However, although there has been a study on the analysis

of urban forest healing program needs in the general population [44] there is still a lack

of evidences to infer the needs and expected value of urban forest healing programs for

individuals with diseases. Therefore, the purpose of this pilot survey was to investigate

the purpose of the urban forest visits, expected values, and preferred components of urban

forest healing programs based on developed questionnaires by expertise for urban forest

visitors with known diseases in South Korea. The secondary purpose of the study was to

see if there were any significant differences in the purpose of the urban forest visits and

expected values of urban forest healing depending on the type of disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of

Helsinki and approved by the Gachon University Institutional Review Board (1044396-

202106-HR-136-01). The purpose of this study was fully explained before the survey was

conducted. All participants who agreed to participate in the survey were required to sign

an informed consent form before beginning the survey.

2.2. Participants

A total of 294 urban forest visitors who had visited urban forests within the last two

years with disease (aged between 15 and 69 years), residing in two metropolitan cities

in South Korea participated in an online survey conducted by a research institution with

a panel composed of the same distribution as the Korean population sensor and secure

representation. A non-probability sample extraction was used to select 294 subjects with

diseases classified in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in

2019. Three thousand seven hundred thirty-five emails were distributed to the panel,

1239 checked their emails and 407 participated in the survey. Among them, 15 respondents

who did not meet the inclusion criterion and 98 respondents who did not complete the

survey were excluded, then, a total of 294 were included as a valid sample for this pilot

survey. The respond rate was 32.8%.

2.3. Questionnaire

A questionnaire was created for this study in order to investigate the awareness of

urban forest visitors with regard to the effects of urban forest healing. A survey titled

“Questionnaire on expected values and needs of urban forest healing effects” was developed

through systematic literature reviews of previous studies [19,44,45] and consultation with a

panel of experts. A draft questionnaire was prepared after several meetings with reference

to the literature review. Next, the validity of the draft questionnaire was investigated by a

panel of experts to determine whether it included appropriate components for the purpose

of the study and was suitable for the patients. The questionnaire consisted of four sections:

(1) general characteristics of the respondents, (2) purpose of urban forest visit, (3) expected

values of the urban forest healing effect, (4) needs of urban forest healing programs,

and (5) preferred components of urban forest healing programs. General population

characteristics included age, sex, education level, marital status, income, occupation, and

presence of disease. The purpose of the urban forest visits, expectation values of the urban

forest, and needs of the urban forest healing program were rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

2.4. Data Collection

An online survey was conducted between 21 to 29 July 2021. The questionnaire was

distributed to residents of two metropolitan cities with urban forests in South Korea via

email with an online survey link. The purpose of the study was described in the first part

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

5 of 14

of the questionnaire, and all valid questionnaires collected during the survey period were

used for the analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows,

version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Frequency analysis was performed according

to the characteristics of each item. Quantitative variables were calculated as mean and

standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as frequency and

percentage. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test for the normality of the data.

A chi-squared test was used to compare the distribution of preferred components of

urban forest healing program in the age and disease categories. One-way repeated analysis

of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the expected values among type of disease.

Additionally, one-way analysis of covariance (ANOCA) test with Bonferroni-adjusted post

hoc test was used to explore the influences of any variables over the dependent variables.

The level of significant was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

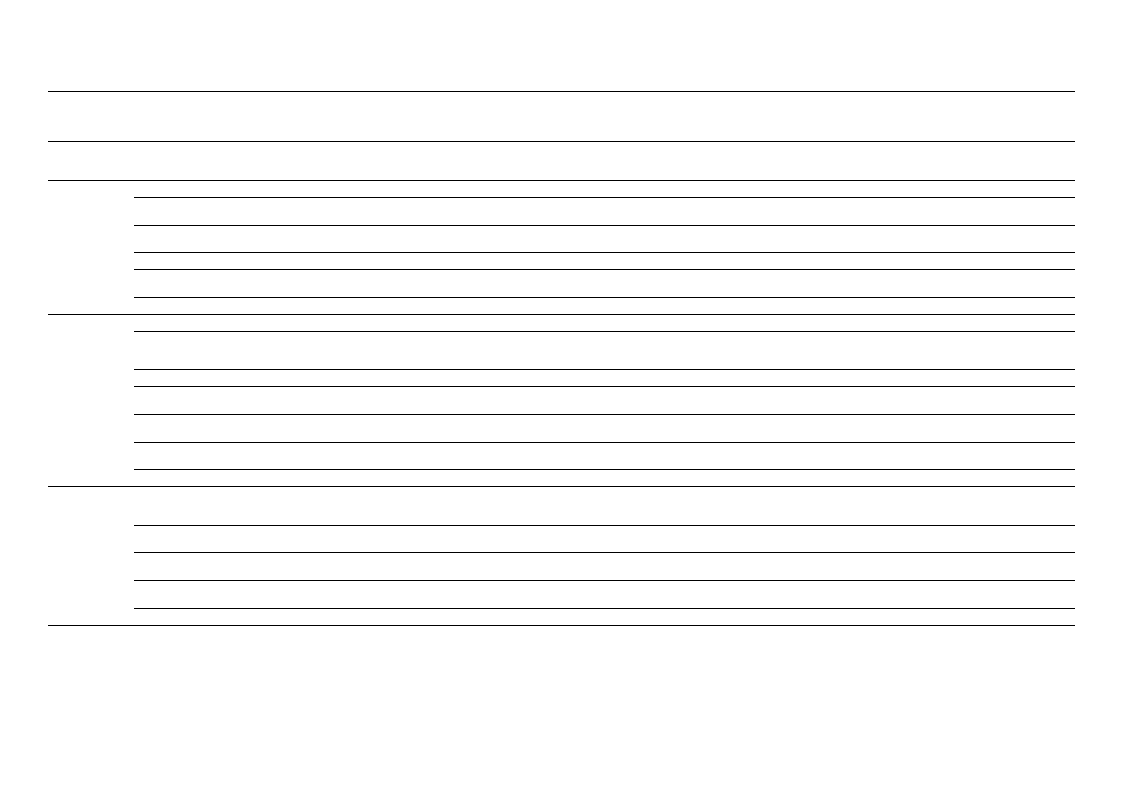

Demographic characteristics of the respondents are described in Table 1. Among the

respondents, 50.5% were women, and the average age was 50.3 ± 14.5 years. The most

common primary diseases reported were circulatory system diseases (55.4%), followed by

respiratory system diseases (11.6%), and musculoskeletal system diseases (9.5%). Multiple

responses were available if there were more disease other than the primary disease, and

83 respondents had more than two diseases. Including multiple responses, a total of 294 re-

spondents had 398 diseases. The most common diseases were circulatory system disease

(43.7%), followed by endocrine system and metabolic diseases (17.1%), respiratory sys-

tem diseases (12.6%), musculoskeletal system diseases (10.8%), depression (8.8%), cancers

(5.0%), and others (2.5%). Other diseases included atopic dermatitis, Parkinson’s disease,

and prostate disease.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the respondents (n = 294).

Characteristics

Age (year), mean ± SD

Gender (women), n (%)

Education level, n (%)

No education or elementary school or middle school

High school

Undergraduate

Graduate school

Marital status, n (%)

Single

Married

Divorced

Economic status, n (%)

Low (below KRW 3,000,000)

Middle (KRW 3,000,000–7,000,000)

High (above 7,000,000)

Missing

Type of primary disease, n (%)

Circulatory system diseases

Musculoskeletal system diseases

Respiratory system diseases

Endocrine system and Metabolic diseases

Cancers

Depression

Others

Total (n = 294)

n (%) or Mean ± SD

50.3 ± 14.5

134 (45.6)

5 (1.7)

82 (27.9)

167 (56.8)

40 (13.6)

78 (26.5)

206 (70.1)

10 (3.4)

79 (26.9)

156 (53.1)

45 (15.3)

14 (4.8)

163 (55.4)

28 (9.5)

34 (11.6)

27 (9.2)

14 (4.8)

24 (8.2)

4 (1.4)

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

6 of 14

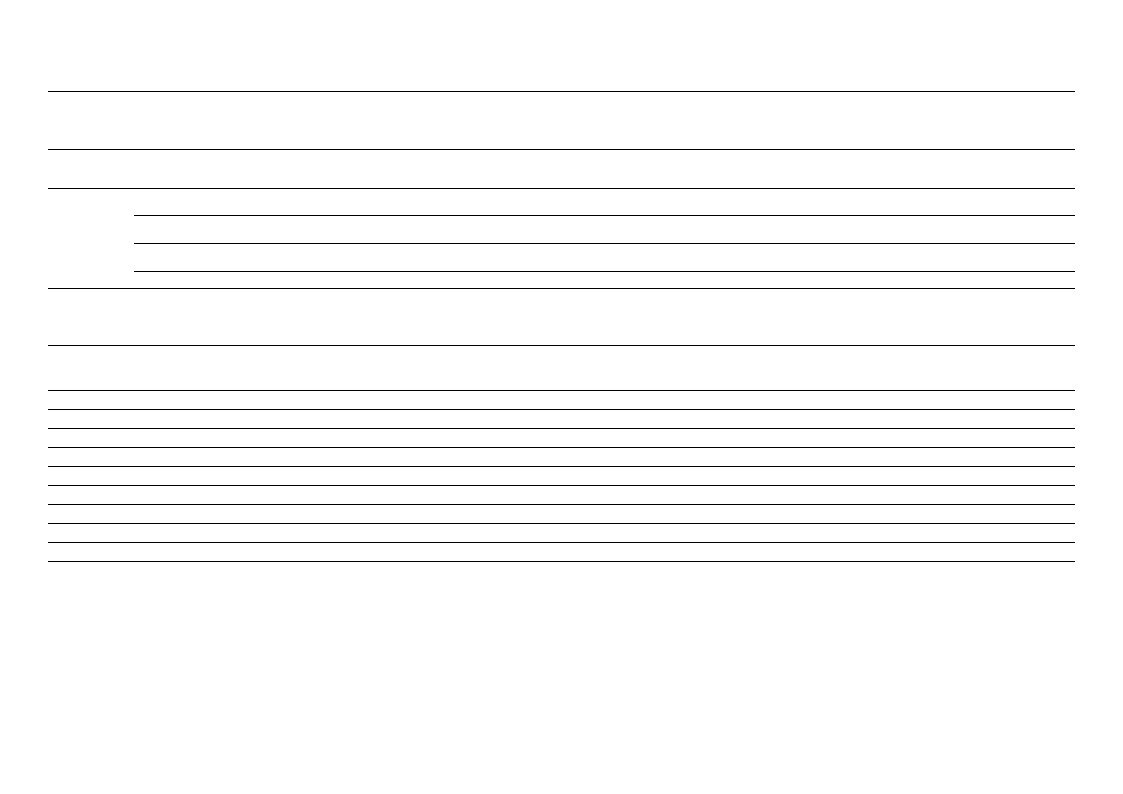

3.1. Purpose of Urban Forest Visit

“Purpose of the urban forest visit” section of the questionnaire contained 18 sub-

objectives under four major categories, all of which could be scored between 1 and 5 points

(1 point: least, 5 points: best). Among the four major categories, “rest/healing” was the

highest scored with 3.97 out of 5, followed by “nature-friendly” (3.70). “risk aversion” was

the least common purpose of the urban forest visit (3.52). Among the sub-objectives, “taking

a walk” under “healthcare” section had the highest score of 4.40 and “maintaining health”

followed closely at 4.09. However, the overall score of “healthcare” was low because of

the low scores of “healing a disease” (2.80) and “participating in healing program” (3.06)

sub-objectives (Table 2).

The purpose of the urban forest visit was significantly different among type of disease

in “healthcare” in the major category, as well as “healing program participation” and “main-

taining health” under “healthcare” section (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant

difference in the purpose of the urban forest visit after controlling for the effect of age

(p > 0.05).

3.2. Expected Values of the Urban Forest Healing Effect

Table 3 shows expected values of the healing effect of urban forest. Before, asking

the expected values of the urban forest healing, the respondents were asked whether they

agreed with the fact that urban forests have healing effects. Two hundred thirty-four (79.6%)

respondents agreed with the healing effects of urban forest. The agreement of the urban

forest healing effect was significantly different depending on the type of disease (p < 0.001).

Only those who agreed were given the follow-up questionnaire. Among the healing

effects provided by urban forest, “mood change” scored the highest with 4.43 out of 5,

followed by “relieving stress” (4.35) and “mental and physical stability” (4.31). “Prevention

of diseases” scored the lowest with 3.73 points followed by “Improving immunity” (3.93).

Expected value of the urban forest healing effect was significantly different among

type of disease in “healthcare”, “improving immunity”, “prevention of diseases”, and

“rejuvenation” (p < 0.05). However, only the expected values of “improving immunity”

differed significantly on types of disease after controlling for the effect of age (F(5227) = 2.208,

p = 0.047). Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc test showed that respondents with circulatory

system diseases had significantly higher expected value of the urban forest healing effect

than those with endocrine system and metabolic diseases in terms of “improving immunity”

(p = 0.035).

3.3. Needs of Urban Forest Healing Programs

Before proceeding with this part of the survey, the respondents were asked whether

they needed an urban forest healing program. Of the total respondents, 81.3% agreed on

the need for an urban forest healing program, and only 3.7% disagreed (Table 4).

When asked the question, “Would you like to participate in the program if healing

program is established in an urban forest for diseases?” 82.0% respondents “agreed” to

participate, while 5.4% did not want to participate in the program.

The necessity and the intention to participate in the urban forest healing program

participation were not significantly different depending on the type of disease (p > 0.05).

The most appropriate time duration of the healing program was 60 min for 121 respon-

dents (50.2%), followed by 120 min for 51 patients (21.2%), and 90 min for 38 respondents

(15.8%). Among the respondents, 106 (44.0%) thought that the appropriate cost of the heal-

ing program in urban forest per visit was “less than KRW 5000 (USD 4.2)” and 78 (32.4%)

thought it should be within “KRW 10,000 (USD 8.4)” (Table 4).

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

7 of 14

Table 2. Questionnaire derived data on the purpose of visit to urban forest in urban forest visitors (n = 294).

Purpose of Visit to Urban Forest

Rest

/Healing

Healthcare

Risk

Aversion

Rest/healing

Spending time

in nature

Escaping from

daily routine

Relieving stress

Physical/mental

rejuvenation

Overall

Taking a walk

Healing

program

participation

Simple exercise

Maintaining

health

Prevention of

disease

Healing a

disease

Overall

Avoiding

particulate

matter

Breathing in

fresh air

Avoiding noise

in the city

Avoiding heat

island phenom

Overall

Circulatory

Diseases

(n = 163)

4.16 ± 0.63

4.02 ± 0.75

3.84 ± 0.82

3.99 ± 0.75

4.15 ± 0.70

4.03 ± 0.56

4.42 ± 0.62

3.24 ± 1.14

3.87 ± 0.90

4.20 ± 0.75

3.55 ± 0.96

2.87 ± 1.04

3.69 ± 0.65

3.02 ± 1.01

3.86 ± 0.88

3.53 ± 0.94

3.80 ± 0.86

3.55 ± 0.78

Musculo-Skeletal

Diseases

(n = 28)

3.94 ± 0.96

4.16 ± 0.88

3.70 ± 1.09

3.66 ± 0.76

3.94 ± 0.71

3.88 ± 0.77

4.53 ± 0.51

3.35 ± 1.25

3.94 ± 0.74

4.29 ± 0.61

3.63 ± 0.91

2.89 ± 0.85

3.77 ± 0.57

3.14 ± 0.93

4.01 ± 0.88

3.57 ± 0.94

4.01 ± 0.85

3.68 ± 0.80

Respiratory

Diseases

(n = 34)

4.19 ± 0.55

3.83 ± 0.89

3.64 ± 1.00

3.79 ± 0.96

4.02 ± 0.83

3.90 ± 0.65

4.45 ± 0.52

2.38 ± 1.15

3.83 ± 0.69

3.90 ± 0.77

3.00 ± 1.08

2.40 ± 0.91

3.33 ± 0.56

2.69 ± 1.04

3.69 ± 1.11

3.07 ± 1.27

3.64 ± 0.98

3.27 ± 0.94

Endocrine &

Metabolic Diseases

(n = 27)

3.91 ± 0.88

4.07 ± 0.66

3.82 ± 0.93

3.79 ± 1.00

3.94 ± 0.96

3.91 ± 0.71

4.53 ± 0.63

2.92 ± 1.05

3.70 ± 0.90

4.10 ± 0.58

3.54 ± 0.87

2.95 ± 1.02

3.62 ± 0.60

3.01 ± 0.78

3.79 ± 0.82

3.70 ± 0.80

3.91 ± 0.83

3.60 ± 0.69

Cancers

(n = 14)

3.90 ± 1.04

3.79 ± 1.22

3.74 ± 1.28

4.01 ± 0.75

3.96 ± 0.80

3.88 ± 0.70

4.12 ± 0.97

3.13 ± 1.19

3.30 ± 1.15

3.90 ± 1.22

3.30 ± 1.22

2.91 ± 1.07

3.44 ± 0.69

2.86 ± 0.93

3.85 ± 1.07

3.35 ± 1.03

3.74 ± 0.93

3.45 ± 0.89

Depression

(n = 24)

4.04 ± 0.81

3.89 ± 0.41

3.93 ± 0.88

3.89 ± 0.88

4.04 ± 0.84

3.96 ± 0.77

4.07 ± 0.70

2.50 ± 1.32

3.46 ± 1.04

3.61 ± 1.05

3.21 ± 1.02

2.75 ± 1.07

3.27 ± 0.84

2.82 ± 0.91

3.68 ± 1.07

3.61 ± 1.10

3.93 ± 0.91

3.51 ± 0.85

Others

(n = 4)

3.39 ± 0.68

3.93 ± 0.41

2.86 ± 1.17

3.57 ± 0.58

3.75 ± 0.90

3.50 ± 0.59

4.46 ± 0.68

3.39 ± 0.68

3.75 ± 0.90

3.39 ± 0.68

2.86 ± 1.17

2.14 ± 0.58

3.33 ± 0.51

2.14 ± 1.01

2.68 ± 1.58

3.39 ± 1.22

3.39 ± 0.36

2.90 ± 0.40

Overall

4.09 ± 0.72

3.99 ± 0.81

3.79 ± 0.91

3.91 ± 0.81

4.07 ± 0.76

3.97 ± 0.63

4.40 ± 1.27

3.06 ± 0.64

3.80 ± 1.19

4.09 ± 0.80

3.45 ± 0.99

2.81 ± 1.01

3.60 ± 0.66

2.96 ± 0.98

3.81 ± 0.94

3.49 ± 0.99

3.81 ± 0.87

3.52 ± 0.81

F(p)

1.549 (0.163)

0.598 (0.732)

1.034 (0.404)

0.944 (0.464)

0.671 (0.673)

0.845 (0.536)

1.725 (0.115)

3.463 (0.003)

1.496 (0.180)

2.915 (0.009)

1.971(0.070)

1.332 (0.243)

2.781 (0.012)

1.159 (0.329)

F(p) †

-

0.215 (0.972)

-

-

-

-

1.379 (0.223)

1.300 (0.257)

-

1.152 (0.333)

0.607 (0.724)

-

0.701 (0.649)

0.330 (0.921)

1.353 (0.234)

1.217 (0.298)

0.659 (0.683)

1.116 (0.353)

0.842 (0.538)

-

-

0.478 (0.824)

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

8 of 14

Table 2. Cont.

Purpose of Visit to Urban Forest

Nature

Friendly

Enjoying the

natural scenery

Using nature

and green space

Communicating

with nature

Overall

Circulatory

Diseases

(n = 163)

3.75 ± 0.87

Musculo-Skeletal

Diseases

(n = 28)

3.73 ± 0.78

Respiratory

Diseases

(n = 34)

3.71 ± 1.03

Endocrine &

Metabolic Diseases

(n = 27)

3.70 ± 0.74

Cancers

(n = 14)

3.79 ± 0.68

3.89 ± 0.79

3.91 ± 0.77

3.95 ± 0.89

3.98 ± 0.64

3.96 ± 0.55

3.51 ± 0.96

3.42 ± 0.91

3.36 ± 1.03

3.42 ± 0.99

3.02 ± 1.34

3.70 ± 0.77

3.69 ± 0.71

3.67 ± 0.84

3.70 ± 0.62

3.59 ± 0.74

† After controlling the covariate (age) which was significantly related to the dependent variables.

Depression

(n = 24)

3.89 ± 0.91

3.79 ± 0.77

3.61 ± 1.07

3.76 ± 0.76

Others

(n = 4)

3.39 ± 0.68

3.93 ± 0.41

2.86 ± 1.54

3.39 ± 0.63

Overall

3.74 ± 0.86

3.90 ± 0.76

3.45 ± 1.01

3.70 ± 0.75

F(p)

F(p) †

0.235 (0.965)

0.151 (0.989)

0.859 (0.526)

0.197 (0.977)

-

-

0.859 (0.526)

0.308 (0.933)

Table 3. Expected values of urban forest healing effect in urban forest visitors who agreed with the urban forest healing effect (n = 234).

Expected Values of Urban

Forest Healing Effect

Healthcare

Increasing exercise effects

Maintaining vitality

Relieving stress

Mental and physical stability

Mood change

Improving immunity

Prevention of diseases

Rejuvenation

Circulatory

Diseases

(n = 133)

Musculo-Skeletal

Diseases

(n = 26)

Respiratory

Diseases

(n = 31)

Endocrine & Metabolic

Diseases

(n = 22)

Cancers

(n = 9)

Depression

(n = 13)

Overall

F(p)

F(p) †

4.38 ± 0.55

4.15 ± 0.54

4.03 ± 0.70

4.32 ± 0.60

4.44 ± 0.60

4.34 ± 0.62

4.30 ± 0.59

2.343 (0.042) 1.293 (0.268)

4.35 ± 0.57

4.18 ± 0.63

4.06 ± 0.62

4.16 ± 0.61

4.05 ± 0.80

4.29 ± 0.71

4.26 ± 0.61

1.771 (0.120)

-

4.38 ± 0.53

4.09 ± 0.62

4.15 ± 0.54

4.29 ± 0.54

4.37 ± 0.56

4.23 ± 0.46

4.30 ± 0.55

1.932 (0.090) 1.318 (0.257)

4.40 ± 0.50

4.37 ± 0.68

4.24 ± 0.52

4.32 ± 0.60

4.13 ± 0.69

4.34 ± 0.62

4.35 ± 0.55

0.770 (0.573)

-

4.34 ± 0.55

4.23 ± 0.60

4.12 ± 0.66

4.38 ± 0.60

4.44 ± 0.48

4.45 ± 0.31

4.31 ± 0.56

1.192(.314)

-

4.47 ± 0.50

4.23 ± 0.64

4.33 ± 0.58

4.48 ± 0.50

4.52 ± 0.51

4.40 ± 0.49

4.43 ± 0.53

1.253 (0.285)

-

4.40 ± 0.63

3.90 ± 0.65

3.73 ± 0.84

3.60 ± 0.52 *

4.21 ± 0.56

4.07 ± 0.84

3.93 ± 0.68

2.328 (0.044) 2.208 (0.047)

3.84 ± 0.74

3.63 ± 0.57

3.36 ± 0.96

3.57 ± 0.73

3.97 ± 0.81

3.79 ± 0.94

3.73 ± 0.79

2.399 (0.038) 1.359 (0.241)

4.31 ± 0.57

3.93 ± 0.84

3.96 ± 0.66

4.12 ± 0.73

4.29 ± 0.51

4.29 ± 0.51

4.20 ± 0.64

2.844 (0.016) 2.029 (0.062)

* Significant difference from those who with circulatory system diseases after controlling the covariate (age). † After controlling the covariate (age) which was significantly related to the

dependent variables.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

9 of 14

Table 4. Needs of urban forest healing programs with preferred duration and cost.

Items

Total (n = 294)

n (%)

Necessity of urban forest healing program

Strongly agree and agree

Strongly disagree and disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Will you participate in urban forest healing program?

Strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree

Strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Preferred duration of urban forest healing program *

30-min

60-min

90-min

120-min

More than 120-min

Preferred cost of urban forest healing program *

Free

Below KRW 5000 (USD 4.2)

KRW 10,000 (USD 8.4)

KRW 10,001—20,000 (USD 8.4—16.8)

Above KRW 20,000 (USD 16.8)

239 (81.3)

11 (3.7)

44 (15.0)

241 (82.0)

16 (5.4)

37 (12.6)

25 (10.4)

121 (50.2)

38 (15.8)

51 (21.2)

6 (2.5)

1 (0.4)

106 (44.0)

78 (32.4)

50 (20.7)

6 (2.5)

* Duration and cost of urban forest healing program were asked from only those respondents who were willing to

participate in the urban forest healing program (n = 241).

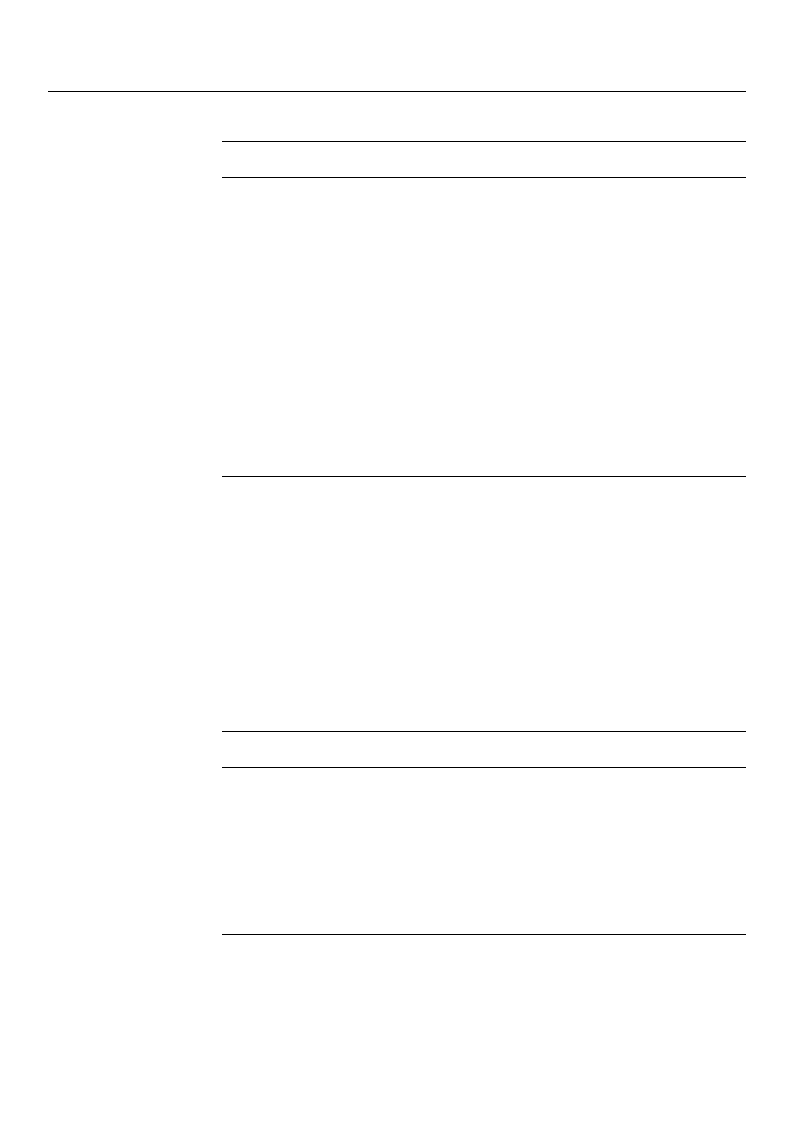

3.4. Preferred Components of Urban Forest Healing Program

Table 5 shows the preferred components of the urban forest healing program for

urban forest visitors with disease. This part of questionnaire was required to be completed

by the respondents who were willing to participate in the program. Multiple responses

were provided. The most preferred component of the urban forest healing program as

reported by the respondents was, “taking a walk” (73.8%). “meditation” (57.7%) and “wind

bath” (50.2%), were also selected as components of high preference by 57.7% and 50.2% of

the respondents, respectively. On the other hand, only 23.1% agreed to inclusion of “art

therapy” in the program; “forest recreation” (24.9%) and “tea ceremony” (31.1%), were

selected as components that were less preferred.

Table 5. Preferred components of urban forest healing program.

Items

Meditation

Taking a walk

Mental and physical reinforcement

Forest gymnastics

Forest recreation

Ecological experience

Wind bath

Performance in the forest

Tea ceremony

Art therapy

Aroma therapy

Multiple answers were available.

Total (n = 241)

n (%)

139 (57.7)

178 (73.8)

117 (48.5)

109 (45.2)

60 (24.9)

88 (36.5)

121 (50.2)

95 (39.4)

75 (31.1)

65 (22.1)

84 (34.9)

4. Discussion

This pilot survey aimed to investigate the expected values, needs, and preferred

components of urban forest healing programs in urban forest visitors with disease and see

if there were any significant differences depending on the type of disease through a user

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

10 of 14

survey. Respondents were classified on the basis of disease types, and circulatory system

disease was reported by 55.4%, respiratory system diseases by 11.6%, and musculoskeletal

system diseases by 9.5% of the respondents in our study. About 70% of the participants had

diseases that demanded lifestyle improvements, including exercise and diet modifications.

This is confluent with the recent observations that people with various types of disease

are visiting urban forests and indicates that the need as well as demand for urban forest

healing programs is expected to rise in the future.

In the present study the most common purpose of visit to the urban forest was reported

as “resting and healing” followed by “nature-friendly” and “healthcare”. The “taking a

walk” sub-objective of the “healthcare” section scored high but “prevention of disease”

and “healing a disease” scored relatively low. These results are similar with the findings

of the previous study on the use of urban forests by visitors with or without diseases,

showing “change of mood” and “mental health promotion” as the highest stated purposes

of urban forest visits with “healthcare” being the least common reported purpose [44]. The

purposes of visit to the urban forest were not significantly different by type of disease after

controlling ‘age’. This shows that urban forest visitors with the purpose of “healthcare” are

more affected by age than type of diseases.

Many studies on forest healing effects have consistently shown psychological benefits

such as reduction in depression and anxiety, as well as physical effects such as decreased

blood pressure and increased NK cell activity [1,11,13,40,46]. However, people without

disease and even with disease were only aware of the psychological effects of forest healing

and were relatively unaware of the effects of forest healing on physical aspects of diseases.

In the current study 79.6% of the respondents agreed on the healing effect of urban

forest, which is similar to the results of a survey in Germany where 77.2% of respondents

were positive of the healing effect of urban forests, of which 45.5% were very confident

about the healing effect [10].

However, it was seen that the agreement with regard to physical healing effects such

as “improving immunity”, and “prevention of disease” was relatively low compared to

psychological healing effects such as ‘mood change’ and “reliving stress”. This shows that

the expectation of physical healing related to urban forest visits is low among people, which

is also reflected in the purpose of urban forest visits. This is in a similar to the previous

study, which reported that the artificial landscape beauty of urban forests is relatively less

evaluated for the healing function of forests than ecologically well-cultivated forests [9]. In

the result of the present survey, the expected values of “improving immunity” significantly

higher in patients with cardiovascular system disease after controlling for the effect of age.

This is believed to be due to the fact that urban forest visitors with cardiovascular disease

expect more to promote immunity because the immune system plays an essential role in

the development and progression of cardiovascular diseases [47].

About 81% of respondents agreed on the necessity of urban forest healing programs,

and 82% of them were willing to participate in the program and it did not differ by the

types of disease. The intention to participate in the programs was much higher in the

current study than in previous surveys showing that 47.2% of the national population [48]

and 58.3% of urban forest visitors [44] were willing to participate in the forest healing

programs. However, as Park et al. [44] did not analyze the intention to participate in the

urban forest healing program based on the presence or absence of disease, this study cannot

be directly compared with our study. It can be assumed that the respondents included in

the current study had a higher intention to participate in these programs because they had

diseases. Applying the program in combination with the conventional treatment in people

with diseases who are understood to have higher needs for forest healing programs could

have the effect of reducing social and economic costs of diseases or other health related

conditions on the healthcare system.

The preferred activities for urban forest healing programs in the decreasing order were

walking, meditation, wind bathing, and forest gymnastics. These results are somewhat

different from the previous studies on forest healing program preferences, where forest

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

11 of 14

gymnastics, wind bathing, and meditation were the highest rated activities [49,50]. ‘Walk-

ing’ was the highest preferred activity as part of the healing program in the present study

and the biggest purpose of urban forest visits, but the expected effect on physical health

was relatively low. This might be due to a relatively lack of understanding of the fact that

walking in the forest has a positive impact on physical health. In general, people are well

aware of the physical benefits of ‘walking’, but the connection to physical fitness seems

to be relatively insignificant because they think that ‘walking’ in the forest has greater

impact on psychological aspect than ‘walking’ in the concrete. This is supported by a

previous study analyzing big data on forest walking showed that walking in the forest

tends to be perceived as leisure activities that taking a walk in the forest [51]. In addition,

our results indicated that visitors with diseases had higher demands for physical activities

such as ‘walking’ and ‘gymnastics’ than people without diseases, as part of urban forest

healing programs, and this should be considered when developing suitable urban forest

healing programs for people with diseases. Moreover, since it is important to constantly

participate in these healing programs at places which are easily accessible in daily life,

urban forests may be more suitable in terms of use for people with diseases than forests

located outside urban areas. Furthermore, it was noted that except ‘walking’, the preference

for physical health-related activities was low, and further studies should be conducted in

order to promote the physical health benefits of urban forests, such as ’health promotion’

and ‘improving immunity’ in addition to the mental health benefits.

According to a Delphi survey conducted on forest healing by 19 experts in medicine,

psychology, and forestry, to predict the preferred targets and diseases that can be applied to

forest healing programs [52], the suitability was reported in the following order: moderate

respiratory, endocrine, nutritional and metabolic, cardiovascular, and digestive diseases.

Specifically, asthma, diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, myocardial

infarction, and indigestion were identified as the target diseases. Expectations for forest

healing effects and urban forest utilization can be promoted in daily life through efforts to

clearly distinguish whether it is a competitive or complementary approach to the existing

treatment methods.

In our study, about 81.6% participants responded that they would participate in the

urban forest healing program for disease and considering the cost that these respondents

were willing to pay for the program as per the results of the survey, it would be quite

valuable to develop and publicize these healing programs. Correspondingly, the Korean

government is actively making efforts to provide forest healing effects within living areas.

At this point, it is very encouraging that awareness of the healing effect of urban forests is

positive. Therefore, efforts will be needed to clearly present the effectiveness of forest heal-

ing programs by developing individualized healing programs for patients and expanding

these to urban forests that are easily accessible in daily life.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the expected values,

needs, and preferred components of urban forest healing programs in urban forest visitors

with diseases. However, the limitations of this study must also be acknowledged. First,

the study was at risk of selection bias, as only those interested in the topic would have

participated in the survey. Further research should use probability sampling methods to

reduce this selection bias. Second, this pilot survey included only urban forest visitors with

diseases; therefore, it is difficult to confirm whether our results were due to the presence

or absence of diseases. Therefore, further studies are warranted to compare urban forest

visitors with and without diseases to obtain meticulous results. In addition, the sample size

of each disease was unequal so that type I error levels may not be guaranteed. Therefore,

further research should include equal sample sizes considering age distribution for each

disease to find out the difference depending on the type of disease and see their relationship

to the degree of awareness or preference of urban forest healing effects, due to various

clinical and pathological characteristics of these diseases. Future studies should focus on

the detailed clinical characteristics of visitors to improve or develop customized urban

forest healing programs for people with various types of diseases.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

12 of 14

5. Conclusions

About 82% of urban forest visitors with disease agreed on the need for urban forest

healing programs and wanted to participate in these programs. The results of the present

survey showed that the purpose of the urban forest visits and expected values of urban

forest healing were mostly not different for each disease and although people with diseases

had relatively lower awareness and expected values of urban forest healing effects on

physical health, the demand for these programs was still high.

Urban forest therapy programs should be developed based on the medical characteris-

tics of the individual disease to maximize the effectiveness of the program. Additionally,

policies should be made to inform general population that urban forest healing is beneficial

not only for mental health but also for physical health. Moreover, our results can be used

as basic data for the development of such programs for people with diseases.

Funding: This research was supported by ‘R&D’ program for Forest Science Technology (Project No.

2021393A00-2123-0103) provided by Korea Forest Service (Korea Forestry Promotion Institute).

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of

the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Gachon University Institutional Review Board

(1044396-202106-HR-136-01).

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated during this study are available from the corre-

sponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Park, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Choi, Y.; Kim, E.; Paek, D. Evidence-Based Status of Forest Healing Program in South Korea. Int. J.

Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10368. [CrossRef]

2. Jeong, D.-Y.; Choi, Y.-E.; Chon, J.-H. Analysis of Importance in Available Space for Creating Urban Forests to Reduce Particulate

Matter—Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 47, 103–114. [CrossRef]

3. Oku, H.; Fukamachi, K. The differences in scenic perception of forest visitors through their attributes and recreational activity.

Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 34–42. [CrossRef]

4. Blazevska, A.; Miceva, K.; Stojanova, B.; Stojanovska, M. Perception of the Local Population toward Urban Forests in Municipality

of Aerodrom. South-East Eur. For. 2012, 3, 87–96. [CrossRef]

5. Nam, E.K.; Lee, S.K.; Research, H. The influences of the tourism motivation on the perceived value and satisfaction of healing

forest visitor. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 29, 79–93.

6. Lee, Y. An Outlook for Social Changes in an Aged Korea: Implications from the Japanese Case Health and welfare policy forum.

Health Welf. Policy Forum 2017, 254, 9–17.

7. Deneke, F. Urban Forestry in North America: Towards a Global Ecosystem Perspective. In Proceedings of the First Canadian

Urban Forests Conference, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 30 May–2 June 1993.

8. Levine, S.; Malone, E.; Lekiachvili, A.; Briss, P. Health Care Industry Insights: Why the Use of Preventive Services Is Still Low.

Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E30. [CrossRef]

9. Chae, Y.-R.; Kang, S.-Y.; Jo, Y.-M.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, S.-Y.; Cheon, I.-S. An Analysis of Needs and Preferences of Forest Healing

Programs in patients with Chronic Diseases. J. Korean Soc. Rural. Plan. 2021, 27, 29–41.

10. Lee, J.-H.; Burger-Arndt, R.J. Understanding the healing function of urban forests in German cities. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat.

2011, 15, 81–89.

11. Lee, H.J.; Son, Y.-H.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.K. Healing experiences of middle-aged women through an urban forest therapy program.

Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 383–391. [CrossRef]

12. Ochiai, H.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Takamatsu, A.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; et al. Physiological

and Psychological Effects of Forest Therapy on Middle-Aged Males with High-Normal Blood Pressure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public

Health 2015, 12, 2532–2542. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

13. Mao, G.-X.; Cao, Y.-B.; Lan, X.-G.; He, Z.-H.; Chen, Z.-M.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Hu, X.-L.; Lv, Y.-D.; Wang, G.-F.; Yan, J. Therapeutic effect

of forest bathing on human hypertension in the elderly. J. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 495–502. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

14. Vujcic, M.; Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J. Urban forest benefits to the younger population: The case study of the city of Belgrade, Serbia.

For. Policy Econ. 2018, 96, 54–62. [CrossRef]

15. Yu, C.-P.; Lin, C.-M.; Tsai, M.-J.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-Y. Effects of Short Forest Bathing Program on Autonomic Nervous System

Activity and Mood States in Middle-Aged and Elderly Individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 897. [CrossRef]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

13 of 14

16. Lanki, T.; Siponen, T.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Pennanen, A.; Tiittanen, P.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T.; Tyrväinen, L. Acute effects of

visits to urban green environments on cardiovascular physiology in women: A field experiment. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 176–185.

[CrossRef]

17. Han, I.D.; Koo, C.-D. The Effect of Forest Healing Program on the Resilience of Elderly People in Urban Forest. J. People Plants

Environ. 2018, 21, 293–303. [CrossRef]

18. Service, K.F. Urban Forest Policy Report; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Korean, 2007.

19. Kim, D.-S.; Lee, B.-C.; Park, K.-H. Determination of Motivating Factors of Urban Forest Visitors through Latent Dirichlet Allocation

Topic Modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9649. [CrossRef]

20. Kim, S.Y.; Kim, B.H.S. The Effect of Urban Green Infrastructure on Disaster Mitigation in Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1026.

[CrossRef]

21. Lee, H.J.; Son, S. Qualitative assessment of experience on urban forest therapy program for preventing dementia of the elderly

living alone in low-income class. J. People Plants Environ. 2018, 21, 565–574. [CrossRef]

22. Yu, C.-P.S.; Hsieh, H. Beyond restorative benefits: Evaluating the effect of forest therapy on creativity. Urban For. Urban Green.

2020, 51, 126670. [CrossRef]

23. Byun, H.-J.; Lee, B.-C.; Kim, D.; Park, K.-H. Market Segmentation by Motivations of Urban Forest Users and Differences in

Perceived Effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 114. [CrossRef]

24. Kim, S.-Y. The effect of choice attribute of forest healing culture affects user expectation value and satisfaction. Cult. Exch.

Multicult. Educ. 2016, 5, 5–29.

25. Deng, J.; Arano, K.G.; Pierskalla, C.; McNeel, J. Linking Urban Forests and Urban Tourism: A Case of Savannah, Georgia. Tour.

Anal. 2010, 15, 167–181. [CrossRef]

26. Poe, M.R.; McLain, R.J.; Emery, M.; Hurley, P.T. Urban Forest Justice and the Rights to Wild Foods, Medicines, and Materials in

the City. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 409–422. [CrossRef]

27. Kim, J.Y.; Shin, C.S.; Lee, J.K. The effects of forest healing program on mental health and melatonin of the elderly in the urban

forest. J. People Plants Environ. 2017, 20, 95–106. [CrossRef]

28. Flouri, E.; Midouhas, E.; Joshi, H. The role of urban neighbourhood green space in children’s emotional and behavioural resilience.

J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 179–186. [CrossRef]

29. Kardan, O.; Gozdyra, P.; Misic, B.; Moola, F.; Palmer, L.; Paus, T.; Berman, M.G. Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large

urban center. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11610. [CrossRef]

30. Ulmer, J.M.; Wolf, K.L.; Backman, D.R.; Tretheway, R.L.; Blain, C.J.; O’Neil-Dunne, J.P.; Frank, L.D. Multiple health benefits of

urban tree canopy: The mounting evidence for a green prescription. Health Place 2016, 42, 54–62. [CrossRef]

31. Lee, K.J.; Hur, J.; Yang, K.-S.; Lee, M.-K.; Lee, S.-J. Acute Biophysical Responses and Psychological Effects of Different Types of

Forests in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 298–323. [CrossRef]

32. Chun, M.H.; Chang, M.C.; Lee, S.-J. The effects of forest therapy on depression and anxiety in patients with chronic stroke. Int. J.

Neurosci. 2017, 127, 199–203. [CrossRef]

33. Jia, B.B.; Yang, Z.X.; Mao, G.X.; Lyu, Y.D.; Wen, X.L.; Xu, W.H.; Lyu, X.L.; Cao, Y.B.; Wang, G.F. Health Effect of Forest Bathing Trip

on Elderly Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseas. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2016, 29, 212–218. [CrossRef]

34. Mao, G.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Xing, W.; Ren, X.; Lv, X.; Dong, J.; et al. The Salutary Influence of Forest

Bathing on Elderly Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 368. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

35. Kang, H.; Chae, Y.; Health, P. Effects of Integrated Indirect Forest Experience on Emotion, Fatigue, Stress and Immune Function

in Hemodialysis Patients. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1701. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

36. Nakau, M.; Imanishi, J.; Imanishi, J.; Watanabe, S.; Imanishi, A.; Baba, T.; Hirai, K.; Ito, T.; Chiba, W.; Morimoto, Y. Spiritual Care

of Cancer Patients by Integrated Medicine in Urban Green Space: A Pilot Study. Explore 2013, 9, 87–90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

37. Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Nakadai, A.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Shimizu, T.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; et al.

Forest Bathing Enhances Human Natural Killer Activity and Expression of Anti-Cancer Proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol.

2007, 20, 3–8. [CrossRef]

38. Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Li, Y.; Wakayama, Y.; et al.

Visiting a Forest, but Not a City, Increases Human Natural Killer Activity and Expression of Anti-Cancer Proteins. Int. J.

Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2008, 21, 117–127. [CrossRef]

39. Kim, B.J.; Jeong, H.; Park, S.; Lee, S. Forest adjuvant anti-cancer therapy to enhance natural cytotoxicity in urban women with

breast cancer: A preliminary prospective interventional study. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 7, 474–478. [CrossRef]

40. Kim, H.; Lee, Y.W.; Ju, H.J.; Jang, B.J.; Kim, Y.I. An Exploratory Study on the Effects of Forest Therapy on Sleep Quality in Patients

with Gastrointestinal Tract Cancers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2449. [CrossRef]

41. Chang, Y.-C.; Tseng, T.A.; Chiu, S.-C. The effect of nature therapy for stress, anxiety, depression and demoralization on breast

cancer patients. GSTF J. Nurs. Health Care 2018, 5.

42. Lee, I.; Choi, H.; Bang, K.-S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Lee, B. Effects of Forest Therapy on Depressive Symptoms among Adults: A

Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 321. [CrossRef]

43. Melnyk, B.M.; Gallagher-Ford, L.; Long, L.E.; Fineout-Overholt, E. The Establishment of Evidence-Based Practice Competencies

for Practicing Registered Nurses and Advanced Practice Nurses in Real-World Clinical Settings: Proficiencies to Improve

Healthcare Quality, Reliability, Patient Outcomes, and Costs. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2014, 11, 5–15. [CrossRef]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 513

14 of 14

44. Suk-Hyeon Park, C.-D.K. Needs Analysis for the Development of Forest Therapy Program Utilizing the Urban Forest-Focused on

the Visitors of Incheon Grand Park. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2018, 22, 11–24.

45. Kim, Y.-H.J.; Joung, D.; Park, B.J. A Study on Analyze Contents of Forest based Therapeutic Programs in Korea. Korean Inst. For.

Recreat. Welf. 2019, 23, 43–58.

46. Stier-Jarmer, M.; Throner, V.; Kirschneck, M.; Immich, G.; Frisch, D.; Schuh, A. The Psychological and Physical Effects of Forests

on Human Health: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021,

18, 1770. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

47. Ruiz, I.F. Immune system and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 503. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

48. Report on ‘Three National Parks in the City, Including Bukhansan Mountain, Have Increased the Number of Visitors; Korea National Park

Service: Wonju, Korea, 2020.

49. Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, E.-J.; Kim, D.-J.; Yeoun, P.-S.; Choi, B.-J. The preference analysis of adults on the forest therapy program with

regard to demographic characteristics. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2015, 104, 150–161. [CrossRef]

50. Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, D.; Yeoun, P.; Choi, B.J. The analysis of interests and needs for the development of forest therapy program in

adults. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2014, 18, 45–59.

51. Kim, G.-H.; Lee, S.-G. An analysis of user perception regarding trail related cafes and blogs using big data collected over 10 years.

J. Hosp. Tour. Stud. 2021, 23, 34–52. [CrossRef]

52. Park, S.; Woo, J.; Kim, W.; Lee, Y.J. Sub-populations and disorders that can be applied to forest therapy. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat.

2012, 16, 35–42.