International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Article

The Psychological Effects of a Campus Forest

Therapy Program

Jin Gun Kim 1, Tae Gyu Khil 1, Youngsuwn Lim 1, Kyungja Park 1, Minja Shin 1 and

Won Sop Shin 2,*

1 Department of Forest Therapy, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju 28644, Korea;

jingun0308@naver.com (J.G.K.); ktg0704@hanmail.net (T.G.K.); suwnmail@naver.com (Y.L.);

parkaous@hanmail.net (K.P.); yeamolove@hanmail.net (M.S.)

2 Department of Forest Sciences, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju 28644, Korea

* Correspondence: shinwon@chungbuk.ac.kr; Tel.: +82-43-261-2536

Received: 15 April 2020; Accepted: 11 May 2020; Published: 14 May 2020

Abstract: This study aimed to examine the psychological effects of a campus forest therapy

program. To evaluate these, pre-test and post-test control group design was employed. A total

of 38 participants participated in this study (19 in the campus forest therapy program group,

and 19 in control). The Profile of Mood State (POMS) questionnaire and Modified form of the Stress

Response Inventory (SRI-MF) were administered to each participant to assess psychological effects.

The results of this study revealed that participants in the campus forest therapy program group had

significantly positive increases in their mood and stress response compared with those of control group

participants. In conclusion, the campus forest therapy program is an efficient strategy to provide

psychological health benefits to university students and our study can inform decision-makers on the

priority of the campus forest program in societal efforts to promote psychological well-being among

university students.

Keywords: forest healing; campus forest; profile of mood state; stress response inventory; university

students’ stress

1. Introduction

Psychological health problems among university students is an important topic. University

students face many of the stressors, including academic demands, social challenges, and uncertainty

about the future, which are linked to increased levels of stress and psychological health problems [1,2].

Regehr et al. [3] reported that more than 50% of college students experience significant levels of anxiety

and depression. The American College Health Association [4], also reported in study results using

80,000 college students that 62% of students suffered overwhelming levels of anxiety and 40% of the

students suffered depression.

The college students with psychological health problems reported negative academic impact [5,6],

relationship dysfunction [7], high rate of drinking [8,9] and substance use [10–12], and high incidence

of suicide [13]. College is an important time, in which young people can adopt lasting healthy lifestyle

habits but is associated with increased chronic disease risk [14,15]. In the absence of a healthy means

to cope or proper support networks, this increase in psychological problems can be extremely taxing

on the body. It is therefore not surprising that maladaptive coping strategies and unhealthy lifestyle

choices are both prevalent and problematic in this population [16]. Therefore, it is important to cope

with psychological problems during the critical university stage. The use of forest and forest therapy is

increasingly recognized as an effective intervention for dealing with psychological problems [17,18].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the effects of using the forest in relieving stress levels and

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409; doi:10.3390/ijerph17103409

www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409

2 of 11

inducing psychological relaxation [19–22]. Spending time in a forest environment has also been shown

to enhance immune function by promoting the activity of Natural Killer (NK) cells [23], to reduce the

stress hormone cortisol concentration [24,25]. Visiting the forest is also increasingly recognized for

its potential to manage stress, and to promote mental, psychological, and physical health. Based on

the empirical research evidence, The Korea Forest Service (KFS) facilitated “Forest Therapy” to utilize

forests for enhancing people’s health and quality of life. The KFS has legitimized the concept of forest

therapy and launched a forest therapist system to develop and manage forest therapy programs [26].

“Forest therapy program” is a set of structured activities and cognitive-behavioral therapy-based

interventions using various elements of the forest environment to mitigate stress and to promote

health [27]. Regarding the psychological effectiveness of forest therapy programs, many previous

studies have reported improvement in depression, self-esteem, and anxiety [28–31]. For example,

Jang et al. [32] also reported that an after-school forest therapy program for infant participants was

effective in improving pro-social behavior and efficiency of expressing themselves. For the office

workers, Shin et al. [33] reported that the two-day forest therapy program provided significantly

positive changes in workers’ job stress and moods.

The campus forest represents a preexisting, accessible, and effective resource for enhancing

psychological health [34]. For example, Lee and Shin [35] reported that the forest therapy program,

performed at a university campus forest using university students, provided significantly positive

emotional improvement. Using 558 voluntary college students, Ibes et al. [34] also reported that

the campus forest provided a significant psychological impact on students, most commonly relief

from stress. Bang et al. [36] conducted a campus forest-walking program targeting university and

graduate students during their lunchtime and reported improvement in participants’ depression and

physical function.

To date, many empirical research results show that forest therapy programs provide a wide

range of psychological health benefits to the program participants [37–39]. However, few studies

on the psychological effects of campus forest therapy have yet been reported. Therefore, this study

was conducted to verify the psychological effects of campus forest therapy programs for university

students and to provide basic data for the development of various forest therapy programs for

university students in the future. Through this study, we hope to inform decision-makers on the

priority of the campus forest program in societal efforts to promote psychological well-being among

university students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants in this study were 38 university students, 24 males (63%) and 14 females (37%),

with a mean age of 22 years. Recruitment posters were posted throughout the university buildings to

recruit volunteers. No incentives were provided to the volunteers. The inclusion criteria required the

participants to be current students at the specified university. More than that, participants who met the

following inclusion and exclusion criteria were considered eligible for the study: (1) no diagnosis of

reaction to severe stress and/or a depressive episode; and (2) could not be suffering from any drug or

alcohol abuse.

We employed the “pretest-posttest control group design” and used a control group because it is

practically impossible to eliminate all of the bias and outside influence that could alter the results of

the experiment. To secure homogeneity between the forest therapy program and the control group,

the participants were randomly distributed into the two groups (i.e., 19 campus forest therapy program

group and 19 control group).

The experiment was conducted during the second semester of 2019 (September–November).

A total of eight sessions’ campus forest therapy program delivered by therapists was performed.

The participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose and signed an agreement.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409

3 of 11

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University

(IRB number: CBNU-201910-SB-945-01).

2.2. Experimental Sites

The field experiment was conducted in the Chungbuk National University campus forest in

Korea. The dominant species in the campus forest are Metasequoia (Metasequoia glyptostroboides),

Cypress (Chamaecyparis pisifera), and other broad-leaved tree species. The study area was a suitable

place for conducting a forest therapy program in terms of accessibility, distribution of a variety of

vegetation, and a low lope of topography. During the eight-sessions, the weather was clear, and the

mean temperature was 16.2 ◦C ± 1.3 ◦C.

2.3. Experimental Design

Forest Therapy Program

To collect data, an eight-session forest therapy program was performed. Once a week, each session

was delivered by a trained forest therapist for one and a half hours. During the eight sessions of the

program, participants were involved in many forest therapy activities such as forest dance, forest

meditation, forest exercise, walking, and others under the instruction of the therapist (see Table 1).

The forest therapy activities were developed and distributed according to each appropriate sessions’

theme based on consultation with researchers in forest therapy/forest recreation and forest therapists

(see Figure 1). The main theme of the program was to reduce stress and improve self-esteem for the

participants. The participants in the control group did not receive leaflets, lectures, or any forest

therapy activities and were asked to follow their routine activities during the experimental period.

Table 1. Themes and Activities of the Forest Therapy Program.

Theme

Rapport building

Stress reduction

Improvement of sense of

belonging and self-esteem

Cooperation and trust

Session

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Program Activities

Ice breaking introduction; familiarity with forest; lecture on

stress management

Clapping exercise; Forest folk dance

Forest orienteering (using natural objects to solve group

mission); Physical stimulation for relaxation

Group gaming activities using natural objects (drawing natural

objects, hit the target with an acorn)

Forest exercise (Forest walking, stretching)

Barefoot walking in forest; Talking to Nature

Natural object five senses game; Photo healing (taking pictures

of nature and story-telling)

Forest band exercise; rope game

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, x

4 of 11

4 of 11

(a)

(b)

FiFgiugurere11. . CCaammppuussfofroersetstthtehrearpaypypropgroragmraminteinrvteernvtieonnt.io(na). fo(rae)stfoforelkstdfaonlcke;d(abn)clee;ct(ubr)e loenctsutrreesson

stmreasnsamgeamnaegnetm. ent.

2.24..4.PPsyscyhcohlogloicgailcaMl eMaseuarseumreenmtent

ToTommeaesausurereththeeppssyycchhoollooggiiccaalleeffffeeccttss ooff the experimmeennttss,,tthhrreeeessccaalelesswweerereaaddmmininisitsetreerdedtotoeaecahch

papratritciicpipanant tbbefeoforereaannddaaftfeterrtthheeiinntteerrvveennttiioonn..

TTooasassessessththeeeefffefeccttoofffoforreesstttthheerraappyy oonn emotionaall ssttaattee,, tthheeKKoorreeaannvveersrisoionnoof fthtehePrPorfoilfieleofof

MMoooddSStatatetess(P(POOMMSS))wwaasseemmppllooyyeedd [[4400]. The POOMMSSiissaarreelliiaabblleeaannddvvaalildidininstsrturummenent tfofrorasassessessisnigng

pspyscyhchoolologgicicaallddisisttrreessss[[4411,,4422]] aanndd hhaas bbeen used prevviioouussllyyttooeessttimimaateteththeeininflfluuenenceceofofbrbireifefofroersetst

exepxpereireiennccee[1[199––2211]]aasswweellllaasslloonngg--tteerrmm ffoorreesstt tthheerraappyy pprrooggrraamm oonnmmooooddssttaatetess[4[433,4,444].].TThehePOPOMMS S

mmeaesausurersessisxixmmooododstsattaetse:s“: t“etnesnisoino–na–naxnixeiteyty(T(–TA–A)”)”“d“edperpersessisoino-nd-edjeejcetciotinon(D(D)”),”“,a“nagnegre–rh–ohsotsiltiitlyity(A(A–H– )”

“fHat)i”gu“efa(tFig)”u,e’ “(cFo)”n,f’u“scioonnf(uCs)io”,na(nCd)”“,vaignodr“(vVi)g”o[r4(1V,4)2”].[4A1,4fi2v]e. -ApofiinvteL-pikoeinrtt sLciakleert(0sc=alsetr(o0n=glsytraognrgeelyto

4 a=grsetreotnog4ly= dstirsoanggrelye)dwisaasgruesee)dwfaosruesaecdh fiotermeatcoheitveamlutaoteeveaalcuhapteaeraticchippaanrtt’iscimpaonotd’ssmtaoteosd. sTtahteesK. oTrheean

veKrosiroenanovf ePrOsiMonSohfaPsOaMreSlahtaivsealyrehlaigtihverleylihabigilhitryel(iCabroilnitbya(cChr’osnαb=ac0h.’8s5α) [=405.]8.5) [45].

ToTommeaesausurereppaartritcicipipaanntt’’ss ssttrreessss rreessppoonnssee lleevveellss,, TThhee MMooddiiffiieeddfoforrmmoof fththeeSStrtersesssRResepsopnosnese

InIvnevnentotroyry(S(RSRI-IM-MFF) )wwasasuusesded. .TThheeSSRRI-IM-MFFwwasasoorirgigininaalllylyddeveveleoloppeeddbbyyKKoohhetetala.l[.4[64]6]anadndrerveivsiesdedby

CbhyoiCeht oail.e[t47a]l.. [T4h7e].STRhIe-MSRFIi-sMaFkiesyamkeeaysumreemaseunret mtoeonltwtoitohl rwesipthecrtetsopesctrtetsos,sptraerstsi,cuplaarrtliycutlhaerlmy ethnetal

hemaeltnhtaalnhdeaplthhyasnicdapl hsyymsicpatlosmyms pretolamtesdretloatsetdretsoss[t4r8es]sa[n4d8]haansdbheaesnbueesnedusperdevpiroeuvsiolyustloy etosteimstiamteattehe

efftheecteofffefcotroefstfothreesrtapthyeprarpoygrparmogornamstroensss[t4re9s]s. T[4h9e].sTcahlee sacsasleessaesssepsasertsicpiparatnicti’psasntrte’sssstrreesspsornesspe olenvseels

rihneahliltecsiielvagumaebhdli5slhri-inetpialnygsioac(iaslbnCuoi5tdlrm-ioLtipnynaiokgtb(iieCnazsrtcarothotLmsi’niocskabanαteali,rezct=aha(ns1t’0csigoa.=9αenl3er=s,,)0t(aar1[.no94n3g=n7d)e]gs.r[dtl4,yre7oapd]nn.ridgselasydsgeidropeinsreea.;sg5Tsri=ehoeens;.tS5rTRo=hnIes-gMtrSlyoRFnaIhg-gMlaryseFeaa)hg.traoTestehaa)e.ltToSohRftae2Il-2SMoRfitFI2e-2MmhaisFts,ehrmaeanlssad, traieevnlaaedctlhiyevaehictlieyhgmh

2.25..5.DDaatataAAnanlaylsyissis

DsocpUecorsSimeocAsTr-pedi)Thpn.aehettrmDieedsveooadespcgtacaiasrortrtaaci-atppoditcctlhieoilisvmeipltclceiaecotincenssgttdtfrescaoa’dfotrpoimmpsfrhtostiiapyrcchtrsciitiioshhnscnoseifosotdlaumorsnmgdtmpudiyacrdeiatowasiyluoenendtwesrcfe,oaefmesanmrtcendeateaasanolnvnydubsaazat,erlceryitsodadwztmbaeuedlndeeesedisnvnvu.aagisrTparidnShitraiePgeodb-SnpleSSeav,aPsn1iifS.arrd8TSete.id0hqo1peuWn8to-.p,est0ineatnf-sWricdtreteyseoqi,sdnwwutasdetnse-ontfrd(weoceSsyrPpsct,sSoee(aSnrwSanc,dPceeCdhSurnhSectpgi,tacceerCgoadorenghcuteodipotcn,ouatIccga(Lpotfgo,eomre,UderepIsStLtseaooAt.nre)t.

pathrteircaippaynptrso’ gprsaymchaonlodgcicoanltreofflegcrtsoubpetsw). eAelnl sptraeti-satincdalpteosstts-twesetrsefuorseedacaht agrpo-uvaplu(feoorefs<t0t.h0e5rsaipgynipfircoagnrcaem

anledveclo.ntrol groups). All statistical tests were used at a p-value of < 0.05 significance level.

3.3.RReessuultlsts

3.1. Profile of Mood States (POMS)

3.1. Profile of Mood States (POMS)

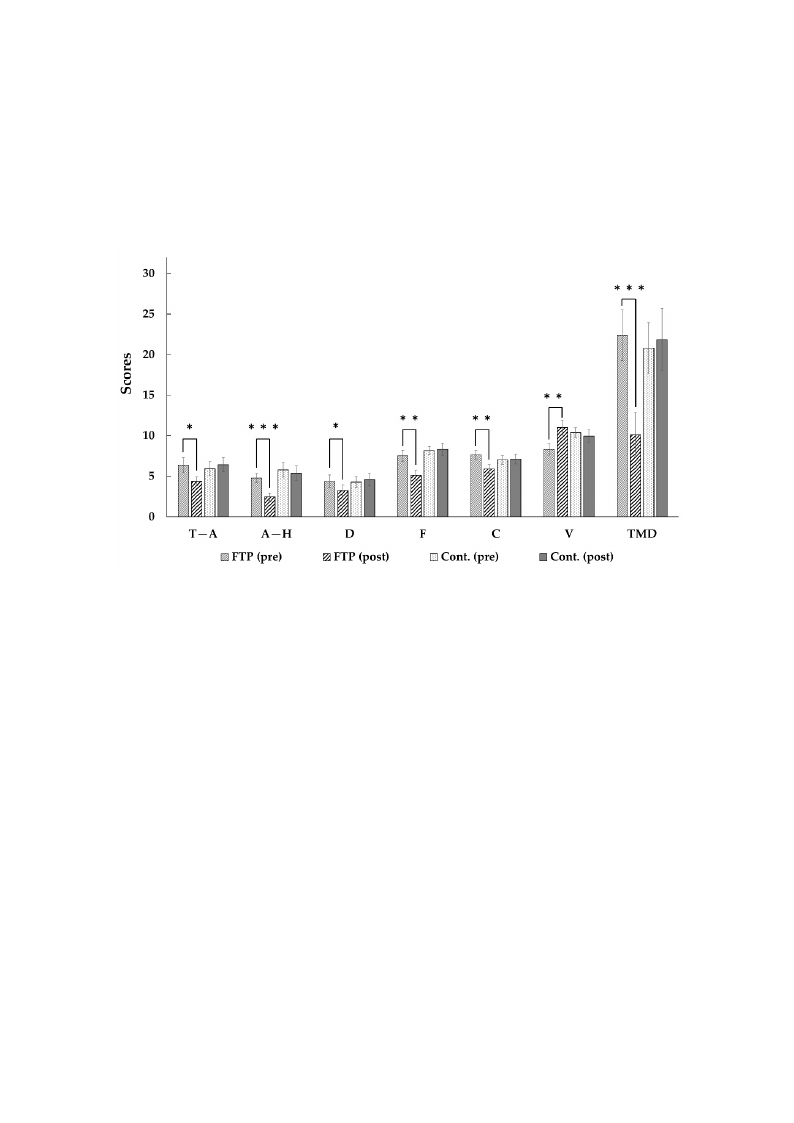

The results of paired t-tests between pre- and post-tests POMS scores for each group are

presenTthede irnesFuilgtsuroef 2p. aAirsedcatn-tebsetssebeent,wteheenrepwrea-s aansdigpnoifistc-atensttsdePcOreMasSesicnorTeostafloMr eoaocdh Dgirsotuuprbaarnece

(spcps(orpcreroreeer2ssee22sn.f23ot.f73eord7r±c±aci3nam3.m.1F1p3pi3u,g,upsupsorfoeofssotrt2re11.es00sAt..t11tst1h1hce±±earrn2a2a.p.7pb7y3ye3,,gstgter=ro=eo4nuu4.,p3p.36tha68aef8,fttr,peeeprr=w=ee0iia.0gg0s.hh00a0t0t)0sss.)eeiT.gsshTsnsieiihoofreinncesrasseunoostlfuftsdflftooeosrcfreorepsfestaaptitsartheheierdeiernradtap-Tpttye-oytsteptapssrltorisMnogidgnroaridocamiadmctaeiDntdienitdsetthtreutvarhretvabntetahtntniehotcrieneeorne

5.90 ± 0.52, t = 3.067, p = 0.007),” and “vigor (pre 8.32 ± 0.71, post 11.00 ± 0.94, t = −2.661, p = 0.016)”.

However, no significant changes were found in the control group in Total Mood Disturbance

(pre 20.79 ± 3.12, post 21.84 ± 3.85, t = −0.355, p = 0.726), nor in all six sub-scales of the POMS: “tension-

anxiety (pre 5.95 ± 0.84, post 6.42 ± 0.87, t = −0.590, p = 0.563),” “anger-hostility (pre 5.79 ± 0.90, post

Int5. .J3. 7En±vi0ro.9n.2R, tes=. P0u.6bl7ic1H, peal=th02.502101,)1,7”, “34d0e9pression-dejection (pre 4.26 ± 0.68, post 4.58 ± 0.74, t = −0.4805, opf=11

0.637),” “fatigue-inertia (pre 8.16 ± 0.53, post 8.32 ± 0.77, t = −0.221, p = 0.828),” “confusion-

wpp o=epbbsreeot0ewts.w4t0si.i0T9l3egd0.e7o9ne)n5”±ritfiem,±ts“hc0te0da.en5.ene74tqtpt6w,lu(r,ypteiotvrsp==esagoil07r2oes.o..nn5i03tu2-c0i8dpv2e7±,ees,o’jpe0fcppc=.hp5t=rai04aeon.,r-06nttgp.0ie0c(eo8spi2sts)pr8”tiaes).n7cn”4.o,t1s.s3ri1“ex7fas±o±sn.ru0gT0f.be6oh.7-r0res-9e,rhc,setaoptl=sowetthss−ietle0oirr3.tef2ay.24ptn6h4(yop,e±arpsPen0i=O.gd46n0.5Mc7i.,8of9tiS1nc=:±0at“r)n2,o0t”t.el.2,5nd0ga5s7irn,fio,fodppeunrop“=-esVsant0,nic.gw20xe.o4si4eer17itp)(ny”p±e,r(rp“pfe0rof.rae14ret-m09it6g.e,3e.sut37dte7=±-sti±-cn40toee..0r62sr.et039tssi,82a,,

(pbreet7w.5e3en±t0h.e68g,ropuopsts,5e.1x1ce±pt0f.o6r4“, vtig=o3r”.0s2u8b, -psc=ale0.(0t0=7−)”2,.2“1c2o; npf=us0i.o03n3-b).eIwn ioldrdeerrmteonstu(ppproert7.s6ta3ti±sti0c.a5l2,

povsatl5id.9it0y±, w0e.5e2v, atlu=at3e.d06re7l,iapbi=lit0y.0o0f 7th)”is, saunbd-s“cavlieg.oCrro(pnrbeac8h.3a2lp±ha0o.7f10,.8p1o3sfto1r1th.0is0s±ub0-.s9c4a,letin=d−ic2a.t6e6d1,

p =re0la.0ti1v6e)l”y. high reliability.

FigFiugruere2.2. TThhee rreessuullttssoof fpapiareirdedt-tet-stteasnt aalnyaselyssoefsPoroffPileroofiflMe ooofdMSotaotdesS(PtaOteMs S()PsOcoMreSs). Tsc–oAre=st.enTs–ioAn–=

tenasnixoine–tya;nCxie=tyc;oCnfu=scioonn;fuAs–ioHn;=Aa–nHge=r–ahnogsetirl–ithyo; sDtil=ityd;eDpr=esdsieopnr;eFss=iofna;tiFgu=ef;aVtig=uve;igVor=; TviMgoDr;=TTMoDtal=

ToMtaol oMdoDodistDuirsbtaunrcbea.nFcTeP. F=TFPo=resFtoTrehsetraTphyerParpoygrParmogGrarmouGp;roCuopn;t.C=oCnot.n=troCloGnrtoroulpG. *r*o*upp<. *0*.*00p1<, *0*.p00<1,

** 0p.0<1,0*.0p1,<*0p.0<5.0.05.

3.2.HMoowdeifvieedr,Fnoromsoigf nthiefiScatrnetsscRhaesnpgoenssewInevreenftooruyn(dSRinI-MthFe)control group in Total Mood Disturbance

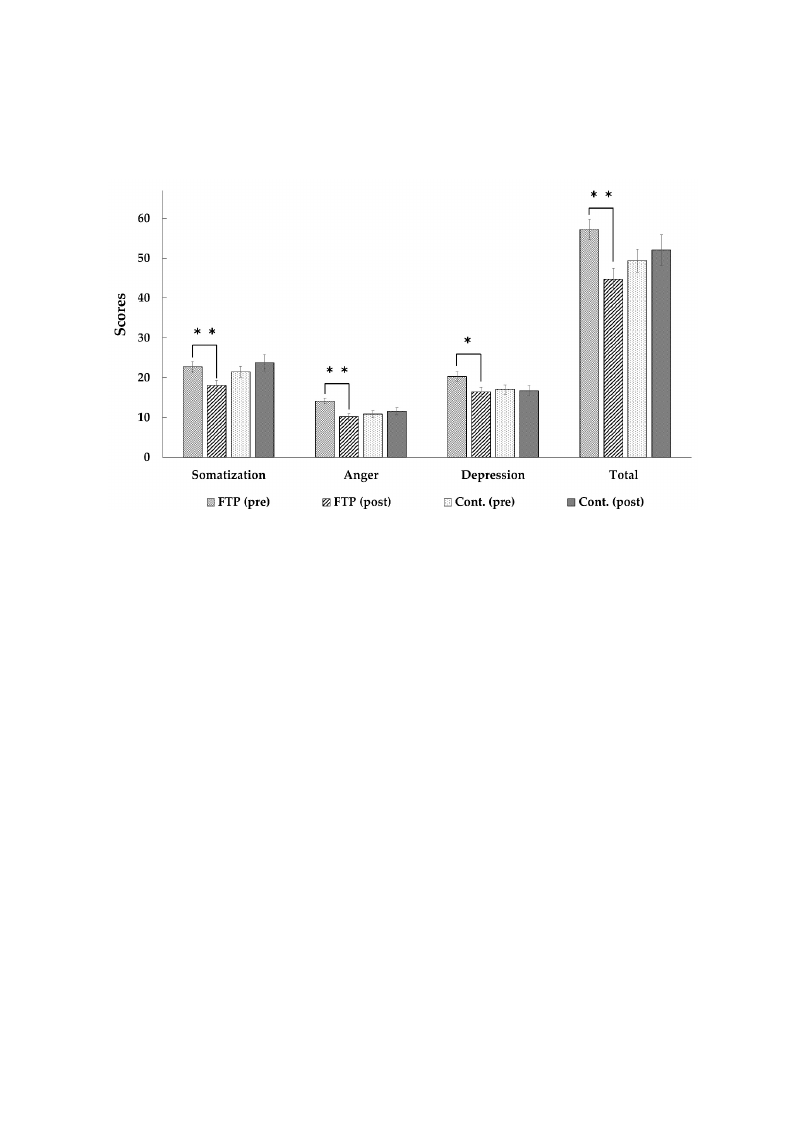

(pre 20T.7o9 e±v3a.l1u2a,tepothste 2e1ff.8e4cti±ve3n.e8s5s, ot f=th−e0.p3a5r5t,icpip=an0ts.7’ 2s6tr)e, snsorresinpoanlsl esiaxftseurbt-hsecaeleigshot fstehsseioPnOs MofS:

“tecnasmiopnu-sanfoxireetsyt (tphreera5p.9y5e±xp0e.8ri4e,npcoesst,6a.4s2e±t o0f.8t7-t,ets=ts−w0.e5r9e0,ppe=rf0o.r5m63e)d”,w“aitnhgperr-eh-oasntidlitpyo(sptr-tee5st.7S9R±I-M0.9F0,

posscto5r.e3s7. ± 0.92, t = 0.671, p = 0.511)”, “depression-dejection (pre 4.26 ± 0.68, post 4.58 ± 0.74,

t = −0.4F8o0r,thpe=pa0r.6ti3c7ip)”a,nt“sfaintigcaume-pinuesrftoiare(sptrtehe8r.a1p6y±p0ro.5g3r,ampogstro8u.3p2, t±he0re.7w7,etre=si−g0n.i2fi2c1a,npt d=ec0r.e8a2s8e)s”,

“coinntfhuesirotno-tbaelwstirledsesrrmesepnotn(spesre(p7r.e0057±.210±.524.,65p,opsots7t .4141.7±4 ±02.6.706, ,tt ==3−.609.02,4p4,= p0.0=020).,8a1n0d)”a,llaontdhe“rVsuigbo-r

(psreca1le0s.3o7f±th0e.6S0R, Ip-MosFt :9“.9s5om±a0t.i7z6a,tito=n 0(p.5r2e22, 2p.7=40±.610.383)”, .post 18.11 ± 1.21, t = 2.903, p = 0.009)”, “anger

(prTeo14te.1s6t e±q0u.7iv0,apleonscte10o.f21pa±r0ti.c7i9p,atn=ts3.f9o8r0f,opr=es0t.0th01e)r”a,payndan“ddecpornetsrsoilognr(opurpes2,0w.3e2 p±e1r.f2o1r,mpoesdt t1-6te.4s2ts

be±tw1.e2e0n, th=e2t.w86o6g, pro=u0p.s0’1p0r)”e-(tSeestesFciogruerse. T3)h.ere were no significant differences in pre-test scores between

the groups, except for “vigor” sub-scale (t = −2.212; p = 0.033). In order to support statistical validity,

we evaluated reliability of this sub-scale. Cronbach alpha of 0.813 for this sub-scale indicated relatively

high reliability.

3.2. Modified Form of the Stress Response Inventory (SRI-MF)

To evaluate the effectiveness of the participants’ stress response after the eight sessions of campus

forest therapy experiences, a set of t-tests were performed with pre- and post-test SRI-MF scores.

For the participants in campus forest therapy program group, there were significant decreases

in their total stress responses (pre 57.21 ± 2.65, post 44.74 ± 2.76, t = 3.690, p = 0.002), and all other

sub-scales of the SRI-MF: “somatization (pre 22.74 ± 1.33, post 18.11 ± 1.21, t = 2.903, p = 0.009)”,

responses (pre 49.42 ± 2.90, post 52.05 ± 3.90, t = − 0.795, p = 0.437), and all other sub-scales of the SRI-

MF: “somatization (pre 21.47 ± 1.37, post 23.74 ± 2.07, t= −1.320, p = 0.203)”, “anger (pre 10.89 ± 0.78,

post 11.58 ± 0.88, t = −0.646, p = 0.527)”, and “depression (pre 17.05 ± 1.19, post 16.74 ± 1.33, t = 0.317,

p = 0.755)”.

Int. J. ETnvoirotne.sRt eesq. PuuibvlaiclHeneaclteh o20f2p0,a1r7t,i3c4ip09ants for forest therapy and control groups, we performed 6t-otfe1s1ts

between the two groups’ pre-test scores. There were no significant differences in pre-test scores

“abnegtweree(pnrteh1e4g.1ro6u±ps0,.7e0x,cpepotsto1n0“.2a1ng±er0”.7s9u, bt-=sca3l.9e8(0t ,=p−=3.101.090; 1p)=”,0a.0n0d4)“.dIneporredsesirotno (spurpep2o0r.t3s2ta±ti1s.t2ic1a,l

pvoasltid16it.y42, w±e1e.2v0a,lut a=te2d.8r6e6l,iapb=ili0ty.0o10f )t”hi(sSseuebF-isgcuarlee.3C).ronbach alpha of 0.730 for this sub-scale indicated

relatively high reliability.

FFigiguurere33. . TThhee rreessuullttssooffppaairiereddt-tt-etsetsat naanlaylsyesseosfoMf oMdoifdieifideFdorFmoromf tohfetshtreesstsrreesssproenspseoInnsveeInntvoerynt(oSrRyI-

(SMRFI-)MscFo)rsecso.rFeTs.PF=TFPo=reFsot rTehsterTahpeyraPpryogPrraomgraGmroGupro; uCpo;nCt.o=ntC. o=nCtroonl tGrorol Gupro. u**pp. *<*0p.0<1,0*.0p1,<*0p.0<5.0.05.

4. DHisocwusesvieorn, no significant changes were found in the control group participants’ total stress responses

(pre 4T9.h4i2s ±stu2d.9y0,epvaolsuta5t2e.d05th±e 3p.s9y0c,hto=log−i0c.a7l9e5f,fepc=tiv0e.n43es7s),, easnpdecailallloythreergasrudbi-nsgcaelmesootifotnheanSdRIs-tMreFss:,

“soofmthateizcaatmionpu(sprfeor2e1s.4t 7th±er1a.3p7y, pporostgr2a3m.7.4 I±t 2re.0v7e,atl=ed−1th.3a2t0,ppar=tic0ip.2a0n3t)s”,in“ancagmerp(upsrefo1r0e.s8t9 t±he0r.a7p8,y

pionstte1rv1e.5n8ti±on0.h88a,dt s=ig−n0i.f6ic4a6n, tply= p0o.5s2i7ti)v”e, acnhdan“gdeesprienssthioenir(pmreoo1d7.0s5ta±te1s.1a9n,dpostsrte1s6s.7r4es±po1n.3s3e,st a=ft0e.r31t7h,e

pi=nte0r.7v5e5n)t”i.on. The result of this study indicated that campus forest therapy provides improvements

in pTaortitceisptaenqtus’ivpaslyecnhcoeloogfipcaalrthiceiapltahn.tTshfoerrefosurelstst othfetrhaispystuanddy acolsnotrporlogvrioduepasr,awtieonpaelrefotormuseedcta-mtesptuss

bfeotwreesetsnttoheprtwomo ogtreouppsys’cphroel-otgesictaslcowreelsl.-bTehienrge awmeroenngousnigivneifirsciatnytsdtuiffdeernetnsc.es in pre-test scores between

the groTuhpesr,eesxucletps toofnth“iasnsgteurd”ysustba-nscdalien(tth=e−s3a.m11e9;lipne= o0f.0a0n4)e. xInteonrsdiveer tnousmubpeprorotfssttautidsiteicsapl vroavliiddiitny,g

weeveidveanlucaetefodrrealniadbisluitpypoofrtthoisfsAubtt-esncatiloen. CRreosntboarachtioanlphTaheoofr0y.7(3A0RfoTr).thAisRsTubp-rsocaploesiensdtihcaattedexrpeolastuivreelyto

hnigahturreel,iasbuiclhitya.s forests, reduces mental fatigue or psychological stress. A theory attempting to explain

4t.hDesiseceufsfseicotsnwas proposed by Kaplan [50]. According to Kaplan’s ART, prolonged use of directed

attention leads to fatigue of neural mechanisms. The recovery of effective functioning is enabled by

settiTnhgiss stthuadty hevaavleuacteerdtathine pkseyychpolroogpiecratlieeffs,ecstuivcehneasss, e“sbpeeincigallaywreagya”r,d“inegxteemnot”t,io“nfaanscdinstarteisosn, ”o,f tahned

ca“cmopmupsafroarbeisltittyh”e.rTahpeyseprcoogmrapmon. eInt trsevreefaelredtotthhaotspeakretiycippraonptesritniecsaomf fpoursesftosrtehsattthtreirgagpeyr pinstyecrhvoelnotgioicnal

hsatdatseisgcnoifintcrainbtultyinpgostoitirveestcohraatnigveeseixnpethrieeinrcme o[5o0d,5s1t]a.tTesheasnedsstutrdeisessrienscpluodnseetshaofsteerofthKeaipnltaenrv[e5n0]tiaonnd.

TShoenrgeseutlatlo. f[5t2h]i.sTshtuedryesiunldtsicoaftethdisthsatut dcaymaplsuossfuoprepsotrthbeiroapphyilpiaro[5v3id] easndimhpurmovaenmeevnotlsutiniopnartyictihpeaonrtise’s

p[s5y4c]h; ohluomgiacanlshheaavltehs.pTehnet rmesaunlytstohfotuhsiasnsdtusdoyf aylesaorps raodvaipdteinagratotiothnealneattouurasleecnavmirpounsmfoernets,tysetot hparvoemoontely

pisnyhcahboiltoegdicuarlbwaenllo-bneeisngfoarmroelnagtivuenliyvefreswitygsetnuedreantitosn. s [55]. Evolutionary perspectives premise that,

The results of this study stand in the same line of an extensive number of studies providing

evidence for and support of Attention Restoration Theory (ART). ART proposes that exposure to nature,

such as forests, reduces mental fatigue or psychological stress. A theory attempting to explain these

effects was proposed by Kaplan [50]. According to Kaplan’s ART, prolonged use of directed attention

leads to fatigue of neural mechanisms. The recovery of effective functioning is enabled by settings

that have certain key properties, such as “being away”, “extent”, “fascination”, and “comparability”.

These components refer to those key properties of forests that trigger psychological states contributing

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409

7 of 11

to restorative experience [50,51]. These studies include those of Kaplan [50] and Song et al. [52].

The results of this study also support biophilia [53] and human evolutionary theories [54]; humans

have spent many thousands of years adapting to the natural environment, yet have only inhabited

urban ones for relatively few generations [55]. Evolutionary perspectives premise that, because humans

evolved over millions of years in natural environments, we are to some degree physiologically and

psychologically adapted to nature rather than to urban settings.

The rapid increase in the urban population worldwide is one of the important global health

issues of the 21st century. According to the projections of the United Nations Population Division,

by 2030 more people in the developing world will live in urban than rural areas; by 2050, two-thirds

of its population is likely to be urban [56]. Urban dwellers face stressful situations in their living

environments, such as work, school, and even home. Therefore, restoration from everyday stress is

essential for their healthy lives. Therefore, the psychological benefits of forest therapy through campus

forests are important, and the campus forest, which is easily accessible to students, is expected to have

very important roles in promoting psychological health.

The results of this study revealed that the eight sessions of campus forest therapy

program provided significant positive changes in the participants’ total mood, and other

mood states such as “anger-hostility”, “tension-anxiety”, “depression-dejection”, “fatigue-inertia”,

“confusion-bewilderment” and “vigor”. The results of this study are consistent with previous

findings using a diverse population of participants such as middle-aged males [37], adults [39], senior

citizens [57], and mental hospital patients with affective and psychotic disorders [58].

The advantage of explicitly studying forest induced mood is that mood has relevant and

long-lasting consequences on such things as the immune system, physiological responses to the stressor,

cognitive skills, and helping behavior. Thus, forest therapy and its consequent moods should be

considered as socially relevant and deserving of public attention, especially for university students

who suffer and face many stressors, including academic demands, social challenges, and uncertainty

about the future. A forest therapy program using campus forests would be an effective and economic

strategy, in terms of time and money, to cope with such stressors for university students.

Positive changes in university students’ mood states provide benefits beyond “feeling good”.

According to Izard [59], mood state influences what is attended to in the environment and therefore can

have a profound impact on subsequent cognition and behavior. Mood change, and mood in general,

have physiological correlates. Mood is an integral part of many forest therapy studies [37,39,57,58]

and is likely to be a product of forest therapy experiences. The significance of mood was demonstrated

by noting the impacts of mood on cognition, behavior, and physiology These impacts include learning,

task performing, helping behavior, socialization, and health [60]. The benefits resulting from improved

mood induced by forest therapy experiences may be one of the major justifications to the university for

the expenditure of its resources on the provision and management of campus forests.

This study also found that the eight sessions of campus forest therapy program provided a

significant decrease in total stress responses, and other sub-scales of the SRI-MF such as “somatization”,

“anger”, and “depression”. This study also confirms the results of previous empirical studies

indicating the forest therapy programs’ effectiveness on stress reduction and coping with stress/stress

response [61–68]. For example, Song et al. [65] reported forest therapy was effective for female

nursing students’ stress reduction. Using participants who were office workers [64], middle-aged

population [49], elementary students [66], and cancer patients [67], most of the studies have reported

participants’ stress level decreases after taking forest therapy programs. Findings from scores of

studies indicate that various stress mitigation benefits are consistently rated by forest therapy as

very important consequences of their participation. The stress response is the process whereby a

person responds physiologically, psychologically, and often with specific behaviors, to a situation that

threatens well-being and health [68].

However, the study had several limitations. Firstly, the participants for this study were limited

to healthy university students in their 20 s. To generalize the findings, further studies are needed

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409

8 of 11

using different groups of the population with different socio-demographic characteristics. Secondly,

this study was conducted in a campus forest to validate the psychological effect of forest therapy.

Effects according to the various characteristics of the greenspace must be examined in the future.

Thirdly, participants’ prior expectations, preferences for nature and experiences of forest may influence

the results. Fourth, in this study the control group conducted their usual activities. Some of the

participants in the control group may use forests for their leisure, and those experiences may influence

the results of this study. Therefore, further studies are needed with participants who spend time

in forests without giving them any instructions. In sub-scales of “vigor” (Figure 2), and “anger”

(Figure 3), there were significant differences in pre-test scores between the forest therapy and control

groups. The differences indicated that the participants in both groups had different baselines of “vigor”

and “anger” levels. These differences may influence the results of this study. Lastly, we recruited

participants for this study as volunteers, using so called self-selection. So self-selection might influence

the results of this study for generalizability. These limitations should be considered in future research.

Despite these limitations, this study provides notable evidence of the effect of forest therapy in a

campus forest, which is easily accessible to students.

5. Conclusions

This study showed that campus forest therapy intervention provided significant psychological

effects. More specifically, there were significant positive changes in participants’ emotional states and

stress responses. These results of study indicated the campus forest therapy program as a strategy

to promote student’s mental health, thereby the effectiveness of forest therapy is suggested as a

complementary therapy in modern urbanized society.

Author Contributions: J.G.K. performed data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation of the results, and

manuscript preparation. T.G.K., Y.L., K.P., and M.S. were involved with the forest therapy program. W.S.S. had an

important role in the overall performance of this research, particularly in experimental design and research idea.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments: We thank the forest healing lab members of Chungbuk National University for their help.

We also gratefully thank forest therapists for their valuable guidance.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Kadison, R.; Di Geronimo, T. College of the Overwhelmed: The Campus Mental Health Crisis and What to Do

about It; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004.

2. Eisenberg, D.; Gollust, S.E.; Golberstein, E.; Hefner, J.L. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety,

and suicidality among university students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 2007, 77, 534–542. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

3. Regehr, C.; Glancy, D.; Pitts, A. Interventions to reduce stress in university students: A review and

meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 148, 1–11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment II: Undergraduate Executive Summary

Spring 2017; American College Health Association: Hanover, MD, USA, 2017.

5. Hartley, M. Increasing Resilience: Strategies for Reducing Dropout Rates for College Students with Psychiatric

Disabilities. Am. J. Psychol Rehab. 2010, 13, 295–315. [CrossRef]

6. Bruffaerts, R.; Mortier, P.; Kiekens, G.; Auerbach, R.P.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Green, J.G.; Nock, M.K.;

Kessler, R.C. Mental health problems in college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. J. Affect.

2018, 225, 97–103. [CrossRef]

7. Kerr, D.; Capaldi, D. Young men’s intimate partner violence and relationship functioning: Long-term

outcomes associated with suicide attempt and aggression in adolescence. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 759–769.

[CrossRef]

8. Geisner, I.; Mallett, K.; Kilmer, J.R. An examination of depressive symptoms and drinking patterns in first

year college students. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 280–287. [CrossRef]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409

9 of 11

9. Pedrelli, P.; Borsari, B.; Lipson, S.K.; Heinze, J.E.; Eisenberg, D. Gender differences in the relationships among

major depressive disorder, heavy alcohol use, and mental health treatment engagement among college

students. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2016, 77, 620–628. [CrossRef]

10. Halperin, A.C.; Smith, S.S.; Heiligenstein, E.; Brown, D.; Fleming, M.F. Cigarette smoking and associated

health risks among students at five universities. NicoTine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 96–104. [CrossRef]

11. Primack, B.; Land, S.; Fan, J.; Kim, K.; Rosen, D. Associations of mental health problems with waterpipe

tobacco and cigarette smoking among college students. Subst. Use Misuse 2013, 48, 211–219. [CrossRef]

12. Keith, D.; Hart, C.; McNeil, M.; Silver, R.; Goodwin, R. Frequent marijuana use, binge drinking and mental

health problems among undergraduates. Am. J. Addict. 2015, 24, 499–506. [CrossRef]

13. Keyes, C.L.; Eisenberg, D.; Perry, G.S.; Dube, S.R.; Kroenke, K.; Dhingra, S.S. The relationship of level

of positive mental health with current mental disorders in predicting suicidal behavior and academic

impairment in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2012, 60, 126–133. [CrossRef]

14. Nelson, M.C.; Story, M.; Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Lytle, L.A. Emerging adulthood and college-aged

youth: An overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity 2008, 16, 2205–2211. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

15. Reynolds, E.K.; Magidson, J.F.; Mayes, L.C.; Lejuez, C.W. Risk-Taking Behaviors Across the Transition from

Adolescence to Young Adulthood. In Young Adult Mental Health; Grant, J.E., Potenza, M.N., Eds.; Oxford

University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 40–63.

16. Schmidt, L.; Sieverding, M.; Scheiter, F.; Obergfell, J. Predicting and explaining students’ stress with the

Demand–Control Model: Does neuroticism also matter? J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 35, 449–465. [CrossRef]

17. Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.; Miyazaki, Y. Trends in research related to “Shinrin-yoku” (taking in the forest

atmosphere or forest bathing) in Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 27. [CrossRef]

18. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, T.; Li, Q.; Kagawa, T.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Effects of

viewing forest landscape on middle-aged hypertensive men. Urban. For. Urban. Gree. 2017, 21, 247–252.

[CrossRef]

19. Park, B.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of shinrin-yoku

(taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across

Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18. [CrossRef]

20. Lee, J.; Park, B.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Ohira, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of forest bathing on physiological

and psychological responses in young japanese male subjects. Public Health. 2011, 125, 93–100. [CrossRef]

21. Tsunetsugu, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, B.; Tyrväinen, L.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological

effects of viewing urban forest landscapes assessed by multiple measurements. Landsc. Urban. Plann. 2013,

113, 90–93. [CrossRef]

22. Lee, J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Takayama, N.; Park, B.; Li, Q.; Song, C.; Komatsu, M.; Ikei, H.; Tyrväinen, L.;

Kagawa, T.; et al. Influence of forest therapy on cardiovascular relaxation in young adults. Evid. Based

Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 834360. [CrossRef]

23. Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimitzu, T.; Li, Y.;

Wakayama, Y.; et al. A forest bathing trip increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer

proteins in female subjects. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2008, 22, 45–55.

24. Park, B.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Hirano, H.; Kagawa, T.; Sato, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects

of shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest)—Using salivary cortisol and cerebral activity as

indicators. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 123–128. [CrossRef]

25. Sung, J.; Woo, J.; Kim, W.; Lim, S.; Chung, E. The effect of cognitive behavior therapy-based “forest therapy”

program on blood pressure, salivary cortisol level, and quality of life in elderly hypertensive patients.

Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2012, 34, 1–7. [CrossRef]

26. Shin, W. Forest Policy and Forest Healing in the Republic of Korea. Available online: https://www.infom.org/

news/2015/10/10.html. (accessed on 2 February 2020).

27. Jung, W.; Woo, J.; Ryu, J. Effect of a forest therapy program and the forest environment on female workers’

stress. Urban. For. Urban. Gree. 2015, 14, 274–281. [CrossRef]

28. Shin, W.; Yeoun, P.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Joo, J. The relationships among forest experience, anxiety and depression.

J. Korean Ins. For. Recreat. 2007, 11, 27–32.

29. Cho, Y.; Kim, D.; Yeoun, P.; Kwon, H.; Cho, H.; Lee, J. The influence of a seasonal forest education program

on psychological wellbeing and stress of adolescents. J. Korean Ins. For. Recreat. 2014, 18, 59–69.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409

10 of 11

30. Lim, Y.; Kim, D.; Yeoun, P. Changes in depression degree and self-esteem of senior citizens in a nursing home

according to forest therapy program. J. KIFR 2014, 18, 1–11.

31. Park, S.; Yeoun, P.; Hong, C.; Yeo, E.; Han, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Kang, J.; Cho, H.; Kim, Y. A study on the effect

of the forest healing programs on teachers’ stress and PANAS. Korean J. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 31, 606–614.

[CrossRef]

32. Jang, C.; Koo, C. Effects of after-school forest healing program activities on infant’s pro-social behavior and

self-efficacy. Korean J. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 31, 595–605. [CrossRef]

33. Shin, C.; Yeoun, P.; Kim, Y.; Eum, J.; Yim, Y.; Yoon, S.; Park, S.; Kim, I.; Lee, S. The influence of a forest healing

program on public servants in charge of social welfare and mental health care workers’s job stress and the

profile of mood states (POMS). J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2015, 104, 294–299. [CrossRef]

34. Ibes, D.; Hirama, I.; Schuyler, C. Greenspace ecotherapy interventions: The stress-reduction potential of

green micro-breaks integrating nature connection and mind-body skills. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 137–150.

[CrossRef]

35. Lee, J.; Shin, W. The Effects of Campus Forest Therapy Program on University Students Emotional Stability

and Positive Thinking. Korean J. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 33, 748–757. [CrossRef]

36. Bang, K.; Lee, I.; Kim, S.; Lim, C.; Joh, H.; Park, B.; Song, M. The effects of a campus forest-walking program on

undergraduate and graduate students’ physical and psychological health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health

2017, 14, 728. [CrossRef]

37. Ochiai, H.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Takamatsu, A.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.;

et al. Physiological and psychological effects of forest therapy on middle-aged males with high-normal

blood pressure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2532–2542. [CrossRef]

38. Shin, C.; Yeon, P.; Jo, M.; Kim, J. Effects of forest healing activity on women’s menopausal symptoms and

mental health recovery. J. People Plants Environ. 2015, 18, 319–325. [CrossRef]

39. Park, C.; Kim, D.; Park, K.; Shin, C.; Kim, Y. Effects of yoga and meditation-focused forest healing programs

on profile of mood states (POMS) and stress response of adults. Korean J. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 32, 658–666.

[CrossRef]

40. Kim, E.; Lee, S.; Jeong, D.; Shin, M.; Yoon, I. Standardization and Reliability and Validity of the Korean

Edition of Profile of Mood States (K-POMS). Sleep Med. Psychophysiol. 2003, 10, 39–51.

41. McNair, D.; Lorr, M. An analysis of mood in neurotics. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1964, 69, 620–627. [CrossRef]

42. McNair, D.; Lorr, M.; Droppleman, L. Manual for the Profile of Mood States; Educational and Industrial Testing

Service: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992.

43. Kim, M.; Wi, A.; Yoon, B.; Shim, B.S.; Han, Y.; Oh, E.; An, K. The influence of forest experience program on

physiological and psychological states in psychiatric inpatients. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2015, 104, 133–139.

[CrossRef]

44. Park, C.; Kang, J.; An, M.; Park, S. Effects of Forest Therapy Program on Stress levels and Mood State in Fire

Fighters. Fire Sci. Eng. 2019, 6, 132–141. [CrossRef]

45. Yeun, E.; Shin-Park, K.K. Verification of the profile of mood states-brief: Cross-cultural analysis.

J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 1173–1180. [CrossRef]

46. Koh, K.; Park, J.; Kim, C. Development of the Stress Response Inventory. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc.

2000, 39, 707–719.

47. Choi, S.; Kang, T.; Woo, J. Development and Validation of a Modified form of the Stress Response Inventory

for Workers. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2006, 45, 541–553.

48. Im, S.; Choi, H.; Song, M.; Kim, W.; Woo, J. Comparison of Effect of Two-Hour Exposure to Forest and

Urban Environments on Cytokine, Anti-Oxidant, and Stress Levels in Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res.

Public Health 2016, 13, 625. [CrossRef]

49. Hong, J.; Park, S.; Lee, J. Changes in depression and stress of the middle-aged and elderly through

participation in a forest therapy program for dementia prevention. J. People Plants Environ. 2019, 22, 699–709.

[CrossRef]

50. Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15,

169–182. [CrossRef]

51. Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press:

New York, NY, USA, 1989.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3409

11 of 11

52. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Igarashi, M.; Takagaki, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological effects of a walk

in urban parks in fall. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14216–14228. [CrossRef]

53. Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984.

54. Ulrich, R.S. Natural versus urban scenes: Some psychophysiological effects. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 523–556.

[CrossRef]

55. Maller, C.; Townsend, M.; Pryor, A.; Brown, P.; St Leger, L. Healthy Nature Healthy People: ‘Contact with

Nature’ as an Upstream Health Promotion Intervention for Populations. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 45–54.

[CrossRef]

56. Srivastava, K. Urbanization and mental health. Ind. Psychiatry. J. 2009, 18, 75. [CrossRef]

57. Yu, C.; Lin, C.; Tsai, M.; Tsai, Y.; Chen, C. Effects of short forest bathing program on autonomic nervous

system activity and mood states in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health

2017, 14, 897. [CrossRef]

58. Bielinis, E.; Jaroszewska, A.; Łukowski, A.; Takayama, N. The Effects of a Forest Therapy Programme on

Mental Hospital Patients with Affective and Psychotic Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020,

17, 118. [CrossRef]

59. Izard, C.; Kagan, J.; Zajonc, R. (Eds.) Emotions, Cognition and Behavior; Cambridge University Press: New York,

NY, USA, 1984; pp. 17–37.

60. Hull, R.B., IV. Mood as a product of leisure: Causes and consequences. J. Leis. Res. 1990, 22, 99–111.

[CrossRef]

61. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Igarashi, M.; Miwa, M.; Takagaki, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological

responses of young males during spring-time walks in urban parks. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2014, 33, 8.

[CrossRef]

62. Lee, B.; Lee, H. Effects of occupational and social stresses after forest therapy. J. Nat. Med. 2013, 2, 108–114.

63. Jang, S.; Koo, C.; Joo, S. Effects of forest prenatal education program on stress and emotional stability of

pregnant women. J. Korean Soc. People Plant. Environ. 2014, 17, 335–341. [CrossRef]

64. Lee, J.; Yeon, P.; Park, S.; Kang, J. Effects of Forest Therapy Programs on the Stress and Emotional Change of

Emotional Labor Workers. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. Welf. 2018, 22, 15–22.

65. Song, J.; Cha, J.; Lee, C.; Choi, Y.; Yeoun, P. Effects of forest healing program on stress response and spirituality

in female nursing college students and there experience. J. KIFR 2014, 18, 109–125.

66. Morita, E.; Nagano, J.; Fukuda, S.; Nakashima, T.; Iwai, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Hamajima, N. Relationship

between forest walking (shinrin-yoku) frequency and self-rated health status: Cross-sectional study of

healthy Japanese. Jpn. J. Biometeorol. 2009, 46, 99–107.

67. Nakau, M.; Imanishi, J.; Imanishi, J.; Watanabe, S.; Imanishi, A.; Baba, T.; Hirai, K.; Ito, T.; Chiba, W.;

Morimoto, Y. Spiritual care of cancer patients by integrated medicine in urban green space: A pilot study.

Explore 2013, 9, 87–90. [CrossRef]

68. Baum, A.; Fleming, R.; Singer, J.E. Understanding environmental stress: Strategies for conceptual and

methodological integration. Adv. Environ. Psychol. 1985, 5, 185–205.

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access

article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution

(CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).