THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF LOW-INCOME SINGLE MOTHERS IN THE U.S. AND THE

EFFECTS OF NATURE AS A PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC TOOL IN THEIR TREATMENT

A dissertation presented to the faculty of

ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA

in partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the

degree of

DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY

in

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

By

Suzanne L. Frost

May, 2019

ii

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF LOW-INCOME SINGLE MOTHERS IN THE U.S. AND THE

EFFECTS OF NATURE AS A PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC TOOL IN THEIR TREATMENT

This dissertation, by Suzanne L. Frost; has been approved by the committee members signed

below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in

partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY

Dissertation Committee:

________________________________________________

Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D.

Dissertation Chair

________________________________________________

Bella DePaulo, Ph.D

Second Faculty

________________________________________________

Thomas Doherty, PsyD,

External Expert

iii

© Suzanne L. Frost, 2019

iv

Abstract

This dissertation describes current research on the lived experience of low-income single

mothers and explores the potential validity of utilizing exposure to natural settings as a

psychotherapeutic intervention for this population. In 2014, 4,764,000 single mothers in the U.S.

were living in poverty. A large percentage of this population suffers from poverty, hunger,

social stigma, as well as mental illnesses associated with these conditions, such as anxiety, stress,

and depression. A qualitative influential research study was performed that included interviews

with eight low income White single mothers and one Biracial Turkish and Chaktau Native

American low-income single mother in predominantly rural Arizona. In these interviews,

participants were asked to describe both causes and mitigating factors in their lived experience of

being low-income single mother including the effects of regularly experiencing nature. Results

indicated predominant financial distress, physical and mental illnesses of mothers and children,

and social stigma and discrimination, as well as other lived experiences. All participants

currently or in the past had found developmental, physical, and mental benefits from nature

contact. Various successful ecotherapy self-care interventions and types of nature experiences

were reported by project participants and validated by ecotherapy research. A proposed model

of ecotherapy for low-income single mothers was theorized. Based on the results of this project,

recommendations for educational and policy change regarding this population and the promising

and often conclusive research on the efficacy of ecotherapy are presented. This dissertation is

available in open access at AURA: Antioch University Repository and Archive,

http://aura.antioch.edu and OhioLink ETD Center, http://www.ohiolink.edu/etd

v

Acknowledgments

This dissertation is dedicated to the many people who encouraged me to take this enriching

academic journey. I wish to thank my mother for making this road easier with her support, and

my dissertation committee members who were enthusiastic, supportive, and reliable. In

particular, I dedicate my dissertation and will always be grateful to the participants in my

research study who graciously volunteered to give their time and share their experiences with

honesty, kindness, and generosity. I wish to thank the many talented and inspiring professors

and staff in the clinical psychology doctoral program at Antioch in Santa Barbara who made

themselves available for consultation whenever I needed it, especially Dr. Ron Pilato’s support

and encouragement in my decision to perform a feminist research project on poverty in the U.S.

for my dissertation. I also wish to thank Stephanie Holland for her patience and kind service to

this doctoral program for many years. Lastly, I am also grateful to the professors with whom I

worked in the doctoral program in clinical psychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute before I

entered this program who first introduced me to this dynamic, transformative, and innovative

field.

vi

Table of Contents

List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. ix

List of Figures .................................................................................................................................x

Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1

Literature Review............................................................................................................................ 4

Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4

Systemic limitations of choice ................................................................................................ 4

Nature as a psychotherapeutic tool ......................................................................................... 5

Definition of “Single” ............................................................................................................. 6

Prejudice, Stigma, and Trends Regarding Single People in General ...................................... 6

Characteristics of Single Mothers ........................................................................................... 7

Child centrality........................................................................................................................ 8

Systemic challenges ................................................................................................................ 8

Stigma and single mothers .................................................................................................... 11

ௗFinancial Hardship and the Hunger of Low-Income Single Mothers .................................. 13

Food insufficiency ................................................................................................................ 14

Womanhood and motherhood wage penalties ...................................................................... 14

African-American single mothers......................................................................................... 16

Latina single mothers............................................................................................................ 17

Asian single mothers............................................................................................................. 18

White single, low-income mothers ....................................................................................... 18

Oppressive Social-Economic Environments and Reported Poor Mental Health of Low-

Income Single Mothers ..................................................................................................... 19

Environment.......................................................................................................................... 21

Physical health effects........................................................................................................... 21

Isolation and lack of social support ...................................................................................... 22

Potential Mitigating Factors and Intervention Strategies ...................................................... 22

The Effects of Nature on Mental Health ............................................................................... 24

Discussion ............................................................................................................................. 34

Method .......................................................................................................................................... 35

Interview Process and Protocol ............................................................................................. 35

vii

Recruitment Criteria and Data Collection ............................................................................. 36

Case Selection and Analyses Methodology .......................................................................... 39

Results........................................................................................................................................... 43

Question 1: What can you tell me about your life in general as a single woman with a child

(or children) living on a small income? ............................................................................ 43

Summary and interpretation of findings ............................................................................... 44

Description of the Qualitative Research Modalities that Were Used.................................... 45

Thoughts and Feelings of the Researcher and Overall Possible Researcher Biases ............. 48

Question 2: Where are you from originally? What town do you currently live in?............ 51

Question 3: How much education have you received (degrees, training?) ........................... 53

Question 4: How many children do you have? What age are they? Do you and your family

have any health issues that you feel comfortable sharing with me about? ....................... 58

Question 5: If you feel comfortable sharing, have you ever been married? How many

times? ................................................................................................................................ 58

Questions 6 and 7: If you are comfortable talking about it, what is your relationship with the

child or your children’s father like? Do you believe the relationship (or lack of

relationship) with the father of your child/children affect(s) you and how you parent?

How? In what ways? Can you give me an example?....................................................... 60

Question 8: Would it be okay with you to talk about your employment status? Part time?

Full time? Work from home? Unemployed? Are you happy with your employment

status? In what ways, if any, does being a single mother affect your employment status?

How about having low income? Do you think this affects your employment, and if so, in

what ways?........................................................................................................................ 62

Question 9: If you feel like talking about it, what has your experience regarding housing? Is

it or has it been stable?...................................................................................................... 64

Question 10: If you feel okay talking about it, what is your experience regarding finances?

........................................................................................................................................... 67

Effects of having low income................................................................................................ 68

Question 11: If you wish to share about it, what is your experience regarding family and

extended family? ............................................................................................................... 71

Question 12: If you feel comfortable sharing about this, what is your experience regarding

the legal system? In other words, have you had any legal issues that you feel like sharing

with me about?.................................................................................................................. 72

My Thoughts and Feelings About the Theme of Divorce and Child Custody Disputes ...... 73

Question 13: If you don’t mind talking about this, what is your ethnic background? To what

extent do you believe that cultural background and ethnicity play a part in your

experience as a single mother? ......................................................................................... 74

viii

Question 14: What benefits and/or obstacles have you noticed as a single mother? ............ 76

Question 15: What have you observed to be your biggest stressors as a single mother? ..... 77

Question 16: Who do you rely on for support? ..................................................................... 77

Thoughts and Feelings about Sharing Time with Research Participants .............................. 77

Survival Strategies of Participants ........................................................................................ 78

Themes in the Narratives of Low-Income Single Mothers ................................................... 80

Question 17: So, switching now to the topic of nature, you’ve told me you enjoy nature.

What types of nature to you enjoy? Do you have a favorite? How often? Do you bring

your child/children? How do you think experiencing this nature affects you and your

children?............................................................................................................................ 81

Nature as a survival strategy for low-income single mothers............................................... 82

Discussion and Conclusions ......................................................................................................... 89

Limitations of the Research................................................................................................... 90

References..................................................................................................................................... 94

Appendix A–Participant Interview Protocol............................................................................... 109

Appendix B—Poster Used to Recruit Research Participants ..................................................... 112

Appendix C—Permissions to Reuse Figures and Table from Authors ...................................... 113

ix

List of Tables

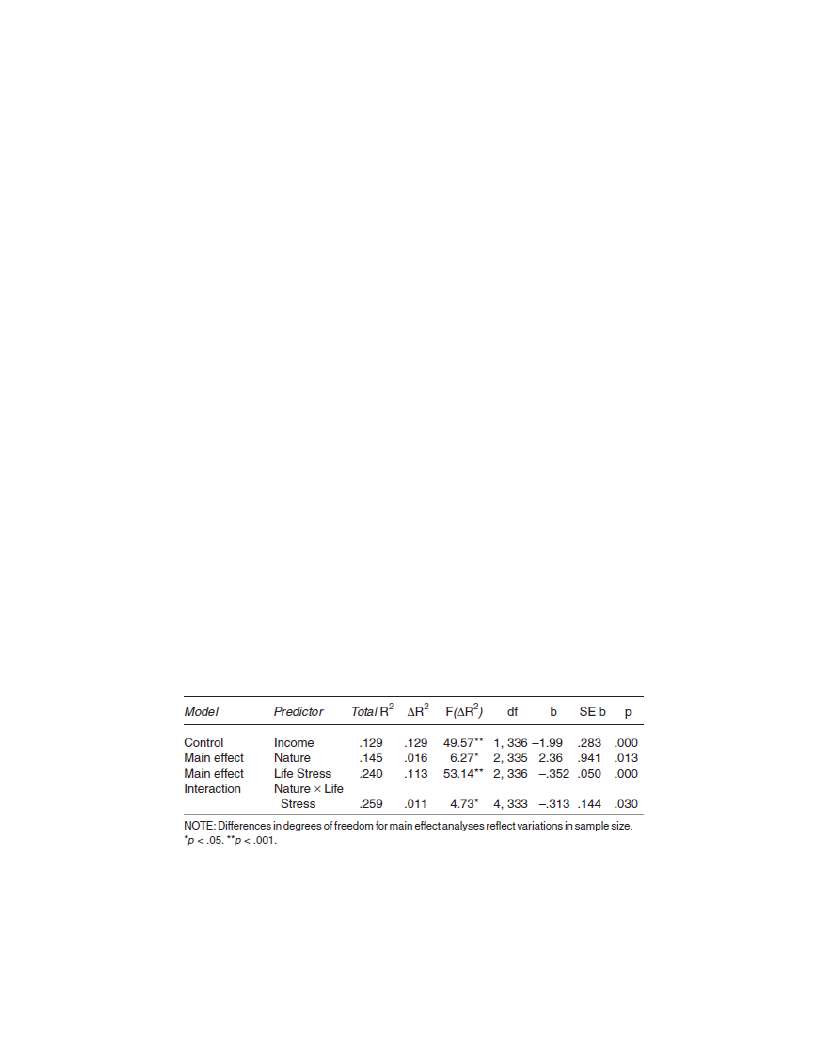

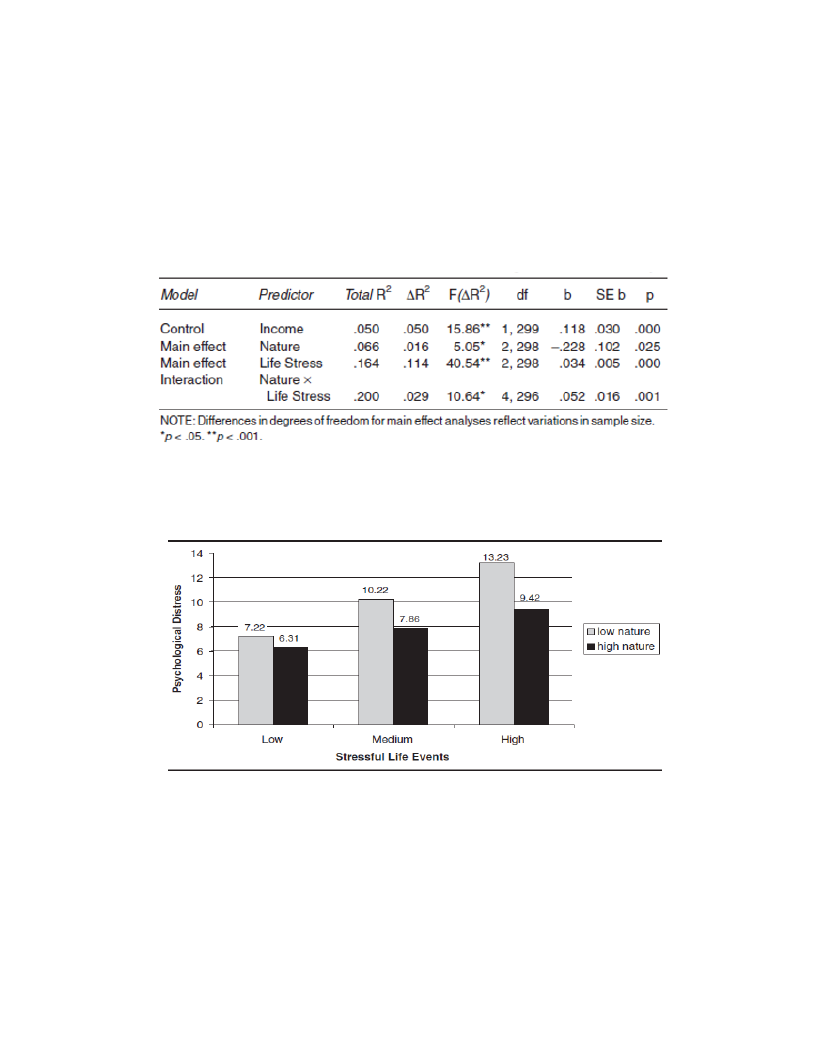

Table 1. Regression of Children’s Psychological Distress (Rutter) Onto Nature, Life Stress, and

the Interaction of Stress x Nature, Controlling for Income (Wells & Evans, 2003)............... 31

Table 2. Regression of Children’s Global Self-Worth Onto Nature, Stressful Life Events, and

Interaction of Stress x Nature, Controlling for Income of Family (Wells & Evans, 2003).... 32

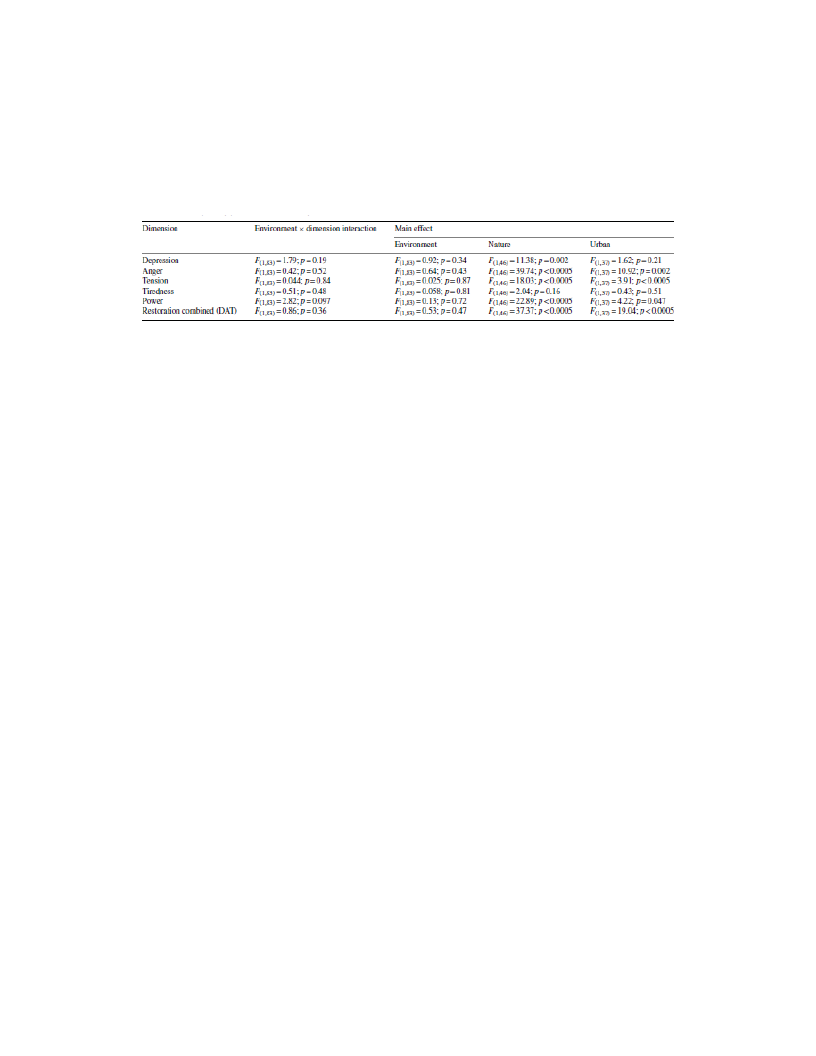

Table 3. The effects of natural and urban environments on dimensions of affective restoration

(Karmanov & Hamel, 2008) ................................................................................................... 34

Table 4. City Where Participants Lived and Whether They Are Happy Living in Their Town in

Their Situation as a Low-Income Single Mother.................................................................... 51

Table 5. Statistics of Mother’s Age, Children, Education, and Health Issues in Participant

Families................................................................................................................................... 53

Table 6. Statistics of Participants Regarding Family, Legal System, Ethnic Background,

Benefits/Obstacles/Stressors, and Support Network............................................................... 70

Table 7. Statistics of Participants Regarding Question 17 about the Effects of Nature in Their

Lives........................................................................................................................................ 81

x

List of Figures

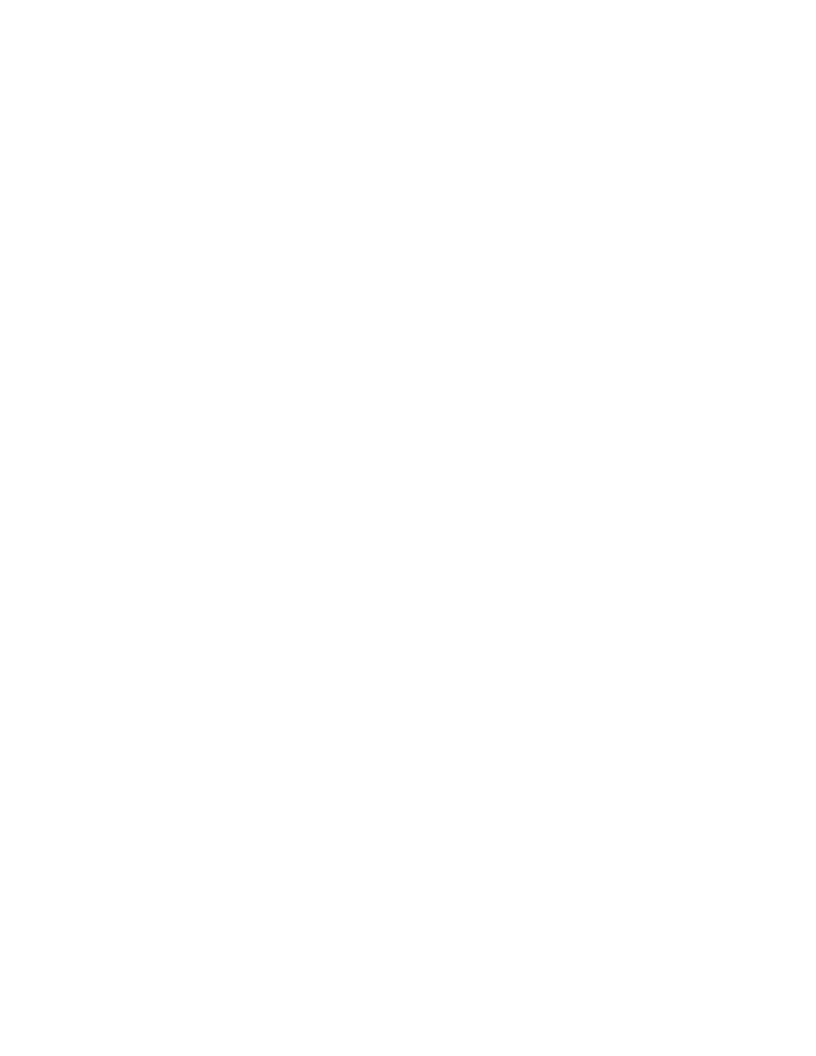

Figure 1. Alterations in Skin Conductance (SCR) in stress and recovery (Ulrich et al., 1991). 27

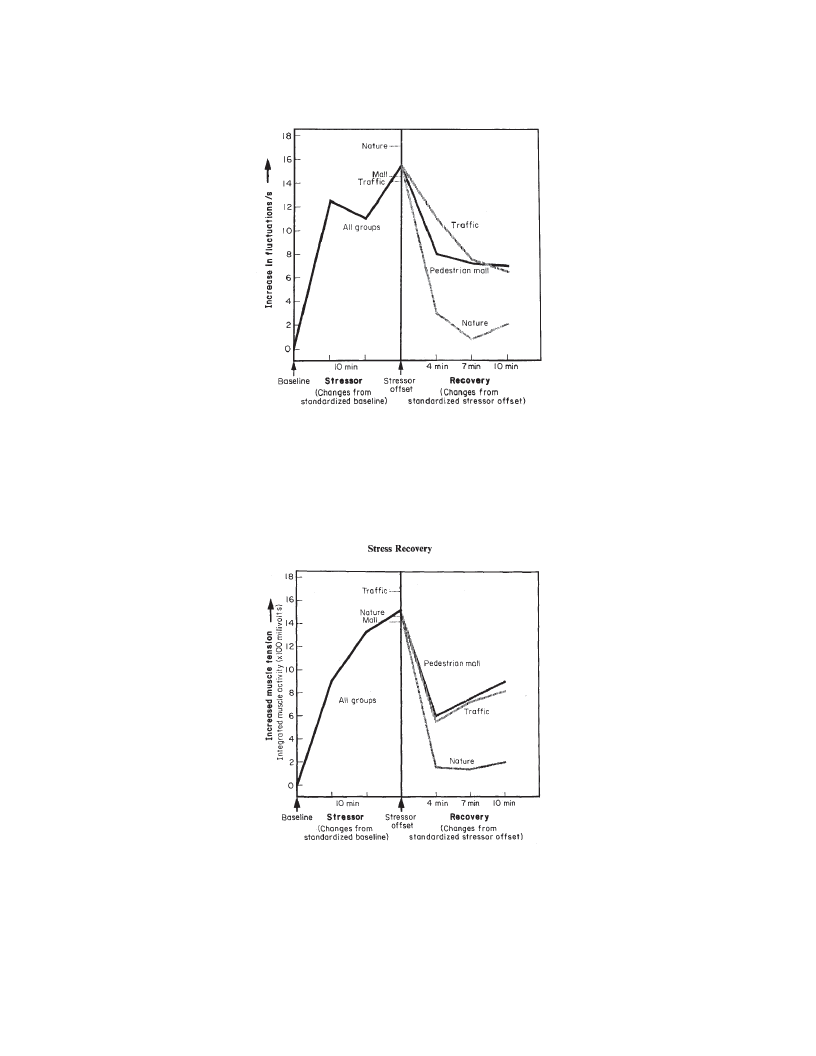

Figure 2. Alterations in Pulse Transit Time (PTT) During Stress and Recovery (Ulrich et al.,

1991). . ................................................................................................................................... 27

Figure 3. Alterations in muscle tension (EMG) during stress and recovery (Ulrich et al., 1991).

Figure 4. Alterations in heart period during stress and recovery (Ulrich et al., 1991). ............... 28

Figure 5. Nature moderated effects of stressful life events on psychological distress ................ 32

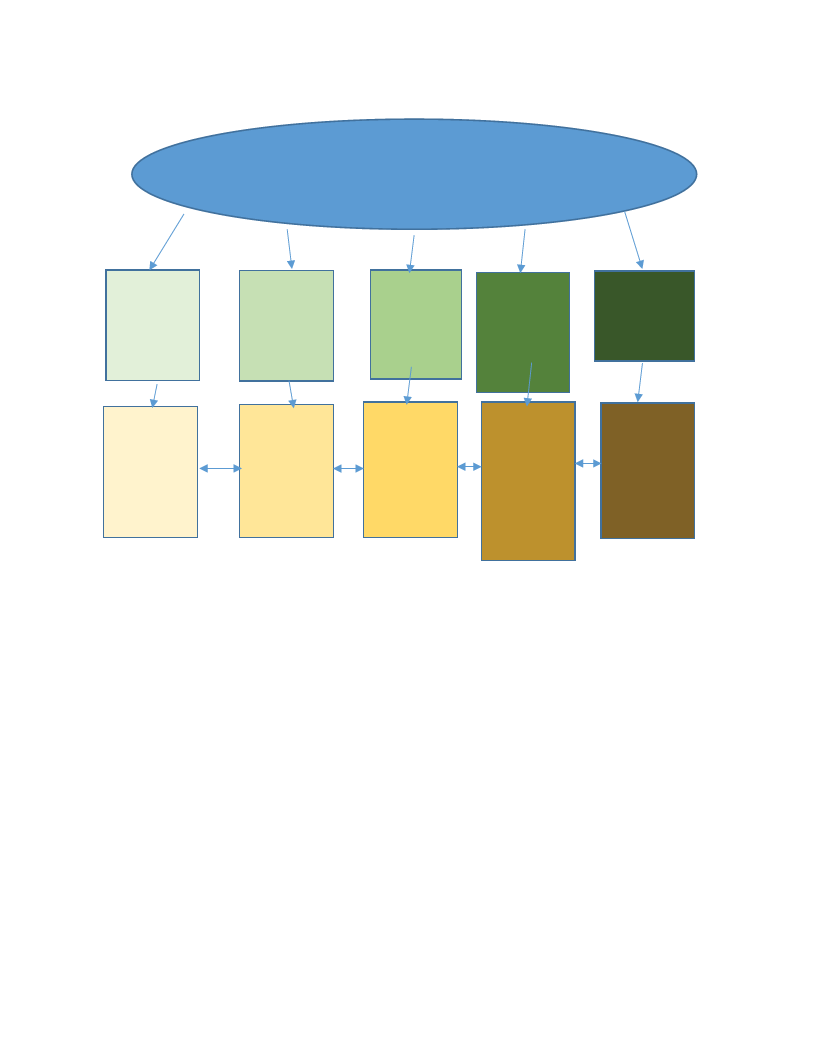

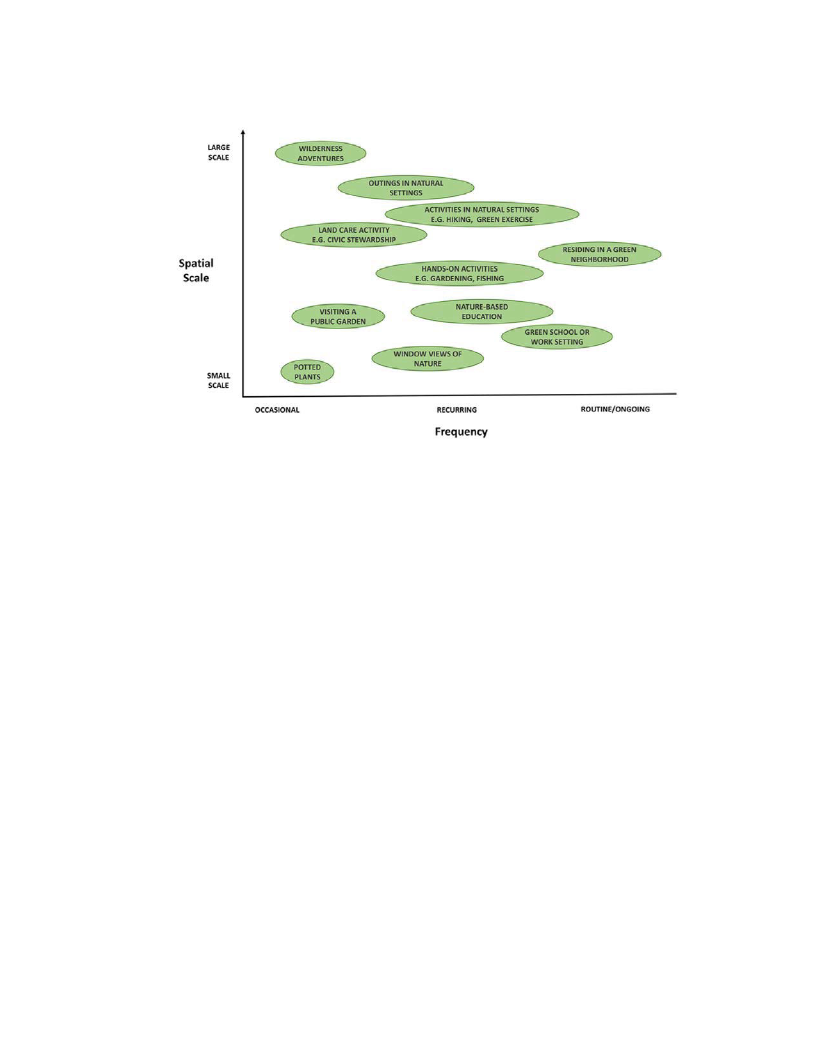

Figure 6. New model of the spectrum of self-care ecotherapy for low-income single mothers and

their children. .......................................................................................................................... 87

1

Introduction

Low-income single mothers in the U.S. face several types of social, economic, familial,

and psychological hurdles in their quests to raise their children safely in a healthy way and gain

greater financial success. In 2014, 4,764,000 single mothers in the U.S. were in living in poverty

(DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015). Current research shows that a large percentage of this

population, more than likely because of poverty (Belle &Doucet, 2003) and the wage disparity

between women and men in society (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015), suffers from and may

have a propensity toward hunger, discrimination, and social stigma, as well as mental illnesses

associated with these conditions, such as substance abuse, anxiety, stress, trauma, distress, and

depression (Platt, Prins, Bates, & Keyes, 2016; Crosier, Butterworth, and Rodgers, 2007;

Rousou et al., 2013; Avison, Davies, Willson, & Shuey, 2008; Broussard et al., 2012;

Baranowska-Rataj, Matysiak, & Mynarska (2014); Zima, Wells, Benjamin, & Duan, 1996). As a

group, these women struggle to maintain housing, feed and clothe themselves and their children,

keep a job, find quality childcare, as well as many other daily living challenges that others who

are married or who are in higher economic situations may not understand or even empathize

with. "Only by acknowledging the bleak reality of poor women's lives, especially the high rates

of traumatization, can we improve their mental health and well-being” (Bassuk, Buckner,

Perloff, & Bassuk, 1998, p. 1564).

This dissertation includes reviews of recent research on the status of low-income single

mothers in the U.S as well as historical and current ecotherapy clinical research, and reports the

findings of a qualitative research study that interviewed nine low-income single mothers in early

2019 in Arizona, the majority of whom live in rural Northern Arizona. Results concluded that

2

current aid and other mitigating factors are apparently not effective enough to counter the

problems of this population.

In the U.S., the poorest type of household is led by single women with no children living

with them (13% of all U.S. households [DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015]), and on average 40%

of all births are to unmarried women (Hamilton, Hoyert, Martin, Strobino, & Guyer, 2013,

p. 552). Half of all children born to unmarried women are poor. The next poorest type of

household besides households led by single women are households led by single mothers, who

represent approximately 12.5% of all types of U.S. households (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015).

Therefore, when addressing the problem of poverty in the U.S., one of the biggest and possibly

most vulnerable population that would be served by an intervention would logically be low-

income single mothers and their children.

This dissertation investigated the possible causes of distress and common mental illnesses

among this population, as well as known mitigating factors in an overall study of the lives of

low-income single mothers. This research project attempted to determine whether some low-

income single mothers currently mitigate short- or long-term mental health illnesses associated

with low income single motherhood by purposely experiencing nonthreatening natural settings.

Results of this study describes participant-reported effectiveness of their various forms of self-

directed ecotherapy as a possible self-caring or clinical psychotherapeutic intervention.

Participant responses about their current status in light of their use of self-directed ecotherapy are

analyzed, and the efficacy of ecotherapy for use with this population is evaluated based on

existing research and analysis of the participant data. Limitations of this study are also

examined, and suggestions are given about future studies that expand the literature regarding

their status and treatment for low-income single mothers in the U.S.

3

The research questions of this study are the following: (1) What are the current lived

experiences of low-income single mothers in the U.S., and (2) what interventions or resources

have been found to be helpful? A hypothesis has been developed that exposure to

nonthreatening natural settings could be a valid mental health intervention for this population.

This leads to the third research question: (3) Does exposure to indoor or outdoor natural settings

improve the mental health of low-income single mothers?

4

Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter explores the possible causes and ramifications of the high poverty rate on

these mothers, their illnesses, and even the high homelessness percentage of specifically low-

income single mothers, as well as the many current mitigating factors that exist, such as cultural

and nuclear family ties, work, quality childcare, child support, and public assistance. Based on

the review of the literature, current mitigating factors are not enough to sustain this population.

Several possible causal systemic factors may have contributed to the high number of low-income

single mothers in the U.S: divorce, unplanned pregnancy, gender inequality between mothers

and fathers in the U.S. and internationally, high U.S. and international poverty rates, and many

other factors. U.S. women from many cultures and their children are associated with poorer

socio-economic outcomes who have either by accident or for whatever reason, become pregnant

and find themselves raising children alone outside of marriage (Monea & Thomas, 2011).

Mitigating factors and supportive clinical interventions for common mental illnesses of this

population are also discussed. Research on ecotherapy and its validity and efficacy are also

reviewed. Few previous studies have looked specifically at ecotherapy as an intervention with

this population. Research on ecotherapy does show that ecotherapy could be a viable valid self-

care or clinical rehabilitation intervention with this population.

Systemic limitations of choice. It is useful to look first systemically at the fact that for

these women in the U.S., motherhood, singlehood, or poverty may or may not have been by

choice. On average, 40 to 50% of married couples in the United States divorce. The divorce rate

for subsequent marriages is even higher. Also, today in the U.S., half of all pregnancies are

unintentional (Monea & Thomas, 2011). In addition to the high risk of divorce and unplanned

5

pregnancy, the costs of pregnancy and childrearing in relationships fall heaviest on the mother

(Budig & England, 2001, p. 205), which could lead to lower economic levels for women in

general. Besides the added expense of children for women as compared to men, women overall

earn lower wages (79%) often for the same or similar work as men (Platt, Prins, Bates, & Keyes,

2016; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Mothers in particular also suffer from a motherhood wage

penalty in the workplace (Budig & England, 2001; Killewald & Bearak, 2010). This literature

review describes the major systemic and cultural factors in the U.S such as the overall high

divorce rate, unintentional pregnancy rates, costs of childrearing and motherhood wage penalty

that all create external societal and cultural pressures that increase the risk of women becoming

low-income single mothers.

Another possibility as to the cause of these women and mothers’ generally lower income

levels is the feminist perspective that women’s lower economic status could be caused by

prejudicial and rigid gender roles (Wood, 2009). Oppressive syntax in language perpetuates

dysfunctional and unrealistic gender roles that, in turn, result in the oppression of women and

nature in culture (Warren, 2015). This prejudice against women, as well as the high rate of

alcoholism and drug abuse in the U.S., may have also contributed in the high rate of domestic

violence against women in the U.S. One in four women in the U.S. have been physically or

sexually assaulted by an intimate partner (Tjaden and Thoennes, 2000). Surely in response to

domestic violence, some women may be forced to choose singlehood if only to protect

themselves and possibly their children.

Nature as a psychotherapeutic tool. This review of the literature did show, however,

that increasing and improving the natural living and work environments in which families reside

may possibly help improve mental and physical illnesses that may plague single mothers. Studies

6

show that the calming and improved cognitive effects of viewing nature may relieve the

debilitating but common stress, distress, depression, and other mental illnesses that low-income

single mothers may endure. Improving the mental health of low-income single mothers may

ultimately result in increasing their own abilities to self-help and self-care, or to seek out and

secure the help that they may need.

Definition of “Single”

Singlehood in the U.S. has its own common social and psychological pressures and

financial burdens, such as social stigma, as well as employment and social discrimination for

both women and men. To escape a deep cultural bias that DePaulo (2005) calls the “Ideology of

Marriage and Family,” this study defines singlehood as an identity in which the individual is not

coupled with another person nor is in a “nonconventional” coupled status (Budgeon, 2008,

p. 302). Furthermore, this study particularly targets single mothers who are not cohabiting with

the father, or another mother, as in a lesbian couple cohabitation. Studies show that financial

benefits and some possible social and mental drawbacks are particular to parental cohabitation

without marriage which, for the sake of clarity, were chosen to be out of the scope of this study,

when possible. However, cohabiting, unmarried single parents and single parents either not-

cohabiting or not in a relationship are combined in census data as “nonmarried family

households.” It is, therefore, often difficult to differentiate these two populations, but the

methodology in this study is to do so when it is possible.

Prejudice, Stigma, and Trends Regarding Single People in General

In her study of Jewish single people, Shachar noted that diversity now exists in terms of

types of relationships amongst people and lifestyles (Shachar et al., 2013). Greater acceptance of

singleness may now exist due to the inability to find the right person or due to personal or

7

economic restraints, though being single raises questions about the possible reasons why people

have “not attained the valued state of marriage” (Shachar et al., 2013, p. 262; Budgeon, 2008;

and Koropeckyj-Cox, 2005). Single adults in society are seen to lead sad, less exciting lives than

those people who are coupled (DePaulo & Morris, 2005). According to several prominent

psychological development models, marriage is considered an achievement that is accessible to

anyone and should be obtained by a certain time in one’s life (DePaulo & Morris, 2005). Even

adults who are divorced are perceived more positively than someone who has never married—

they have not apparently crossed this “developmental milestone” (DePaulo & Morris, 2005).

Most cultures elevate and privilege couple relationships (Budgeon, 2008; DePaulo &

Morris, 2005). Though single identity may be strong in some individuals, Budgeon (2008) found

in her study of 51 individuals of both sexes that “…heteronormativity bounds the telling of

intimate lives because the idealized relationship form of coupledom operates as a central

reference point, albeit one that is critiqued, resisted, and at times, subverted" (Budgeon, 2008,

p. 319). Therefore, even defining the state of singlehood as “not married” refers back to “an

idealized relationship form of coupledom” in society.

Characteristics of Single Mothers

In general, in all societies, a percentage of pregnant women or mothers with children

have been single mothers. Many experiences can lead women to become single mothers,

including personal choice, widowhood, intimacy before marriage or without marriage, divorce,

domestic violence, reduced access and social support for abortion and birth control medical

services, casual sex, partner abandonment, a single motherhood personal preference,

homosexuality, or possibly rape.

8

Census data reveal that the percentage of single women with recent births in 2011

decreased with increased income: 68.9 % of recent mothers making less than $10,000 were

single, whereas 9% of recent mothers making more than $200,000 were single. These data

suggest that low-income single women are having more pregnancies recently than higher income

single women despite their vulnerable financial situation. A topic for future research would be to

determine whether having a middle-class or wealthy lifestyle and income made it too difficult to

do both, and for what reasons.

Child centrality. Edin and Kefalas (2011) argue that low-income single mothers have a

cultural “childhood centrality” that is in sharp contrast with higher income mothers who appear

to put “education, career, and life goals” first resulting in delayed or lower pregnancies. “While

the poor women we interviewed saw marriage as a luxury, something they aspired to but feared

they might never achieve, they judged children to be a necessity, an absolutely essential part of a

young woman’s life, the chief source of identity and meaning,” which contrasts significantly to

attitudes expressed by middle-class single women across all ethnicities (Edin & Kefalas, 2011,

p. 6).

Systemic challenges. Systemic factors contribute to the high numbers of single low-

income mothers. The U.S. has the highest poverty rate among all wealthy nations (Gould &

Wething, 2012; Belle & Doucet, 2003). In 2017, the official U.S. poverty rate dropped to 12.3%

(1 in 8 Americans) and is part of a Census-reported, three-year trend in a downward national

poverty rate from 2014, when a little over 46 million people (1 in 7 Americans) in the U.S. were

in poverty (14.8% of the U.S. population) (Fontenot, Semega, & Kollar, 2018; Semega,

Fontenot, & Kollar, 2017; DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2014). “In 2017, there were 39.7

9

million people in poverty, not statistically different from the number in poverty in 2016”

(Fontenot et al., 2018, p. 11).

The income gap between woman and men living with family has not been closing.

Eighty-three million families (9.8%) of all primary U.S. families with a minimum of one other

family member living at home were reported to be living in poverty in 2017, of which

approximately 25.7% were female heads households with no husband present; 4.9% married

couples, and 12.4% male householders, with no wife present (Fontenot et al., 2018).

Approximately half of all children who live in women-lead households live below the poverty

level (Pressman, 2018). The prevalence of poverty in the U.S. makes it likely that vulnerable

populations would possibly have more difficulty in the intensely competitive U.S. culture. Yet

to compete economically, gender income inequality would need to be remedied.

Adding to the prevalence of poverty in the U.S., the number of women in poverty (13%

of 18- to 64-year-old women in the general population) is greater than the number of poor men in

the U.S. (9.4% of 18- to 64-year-old men in the general population) (Fontenot et al., 2018;

DeNavas-Walt et al., 2012). The 2017 poverty rate of female and male children under 18 were

not statistically different at 17.7 and 17.3%, respectively (Fontenot et al., 2018). Minority

women in general have far greater poverty in general than White or Asian minority women, as

well as both minority and nonminority men. “In 2013, approximately 21% of school-age

children were in families living in poverty. The percentage of school-age children living in

poverty ranged across the U.S. is from 9% in New Hampshire to 33% in Mississippi,” according

to the U.S. Department of Education (Aud, Wilkinson-Flicker, Nachazel, & Dziuba, 2013). No

doubt, this prevalence of poverty and its variation by region contribute to some single mother’s

apparent temporary or permanent inability to become economically successful. The systemic

10

challenges of the poor in the U.S. cannot help but adversely affect low-income single mothers

who have complex vulnerabilities.

As mentioned earlier, the high rate of unintentional pregnancy, the higher rate of

childcare expense born by women, lower overall economic advantages of women as compared to

men, and prejudice against women in general all contribute to systemic low income single

mother’s inequality and prejudice against low-income single mothers that is part of singlism

against all single women and men (DePaulo, 2006). In addition, low-income single mothers as

women in society must not only contend with their nonconventional status and subsequent

stigma as a single mother outside of a conventional nuclear family and full responsibility of

raising their children, but also the general prejudices that exists culturally in an often sexist world

that tends to value men over women. This dissertation describes and analyzes poverty as a form

of violence against low-income single mothers that may result from the sexist, racist, and singlist

patriarchal order in the U.S. (Roschelle, 2017, p. 1000; DePaulo, 2014) and throughout the world

(Kabeer, 2015). As A. R. Roschelle summed up in her article, “Our Lives Matter: The

Racialized Violence of Poverty Among Homeless Mothers of Color,” “[R]ace, class, and gender

discrimination intersect and result in communities plagued by inadequate educational

opportunities, high rates of unemployment, excessive crime, and poor physical and mental

health” (Roschelle, 2017, p. 1001).

Increasing birthrates. The number of single mothers in the U.S. is increasing. Among

White women in the U.S., the birthrates of single women doubled between the midyears of the

1970s-1990s (Shachar et al., 2013). In 2005 in the U.S., one out of three White children were

born into single women households and for African Americans, the birthrate was two out of three

children born to single women households (Shachar et al., 2013). In 2011, 40% of all births were

11

to unmarried women (Hamilton et al., p. 552).

A staggeringly large portion of the U.S. household population are now led by low-income

single mothers. According to data provided by the U.S. Census, in 2012, 24.9% of U.S.

households were headed by a single mother (U.S. Census, 2013), and approximately 1.5% of the

U.S. population are low-income single mothers: 4,764,000 (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015).

The percentage of single father households with children under the age of 18 from 2001 to 2007

ZDV%ODFNZHOOௗ7KLVODUJHSHUFHQWDJHRIKRXVHKROGVKHDGHGE\\DVLQJOHPRWKHULVD

significant change in U.S. society (Rousou, Kouta, Middleton, & Karanikola, 2013) because the

number of single parent households has grown 10% from 1970 to the 2012 rate of 27% (U.S.

&HQVXVௗ

Stigma and single mothers. Recently, studies are mixed as to whether stigma against

single mothers is still prevalent with low-income women, though all indications are that single

motherhood is often perceived as costlier, not optimal, and may illicit suspicion. On the one

hand, deep stereotypes and the reality of economics have stigmatized women’s singleness as not

being a desired state regardless of the fact that some women do choose this as their preferred

lifestyle, while others do not and come upon singleness by default (Shachar et al., 2013). Single

mothers are breaking two of traditional society’s cultural taboos: remaining single and having

children out of wedlock. Single mothers in society may internalize the social stigma around them

from negative stereotypes placed on single mothers by society (such as being seen mistakenly as

promiscuous, rebellious, or disrespectful of cultural norms). They may experience stigma as a

result of a fear from being treated poorly by others (Broussard et al., 2012).

Though many women either have chosen or have found themselves in the state of single

motherhood, studies show that having a child as a single parent as compared to having a child

12

while married may bring more cost than benefit to one’s life (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003).

“Those [parents] who have been continuously unmarried are most disadvantaged in terms of the

effects of parental status on self-efficacy” (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003, p. 363). Nomaguchi &

Milkie (2003) also found that continuously unmarried parents may be more depressed than

continuously married adults who become parents (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003, p. 365). To the

contrary, married women experienced a positive effect of parental status. Woo and Riley (2005)

point out in Nomauchi and Milkie’s study that they did not isolate cohabiting single parents in

their analyses. Furthermore, as Bumpass & Lu (2000) reported from the National Survey of

Family Growth, 39 % of single mother births were to nonmarried, cohabiting couples. As stated

previously, it would be useful for future studies to differentiate the characteristics of single, co-

parenting, cohabiting couples.

Yet studies reveal that some low-income single mothers may view divorce as more

stigmatizing than being a single mother and, therefore, would rather have their first child while

single and then wait and see whether a marriage with the father or another man would work out

(Edin & Kefalas, 2005). In the 21st century, some African Americans, Non-Hispanic Whites, and

Puerto-Rican low-income single mothers were found to choose to have children before they were

married rather than making a marriage mistake, which indicated that the stigma of motherhood

had waned somewhat for these groups (Edin & Kefalas, 2005). Though they did not have the

same findings as Edin & Kefalas regarding the desire for early unmarried pregnancy, Cherlin,

Cross-Barnet, Burton, & Garrett-Peters (2008) found that single mothers do not feel stigmatized

for having a child out of wedlock in low-income neighborhoods. overall, “the social climate in

which our mothers’ lives treats births outside of marriage as events that may not be optimal, but

which carry little stigma” (Cherlin et al., 2008, p. 11).

13

Nevertheless, being a single mother can have several disadvantages that can be observed

across culture and socioeconomic status (Baranowaska-Rataj, Matysiak, & Mynarska, 2014;

5RXVRXHWDOௗ Disadvantages that single mothers have identified can be grouped into four

main categories: financial hardships, psychological health, physical health, and social stigma

(e.g., Baranowska-Rataj et al., 2014; Kingston, 2013; Broussard, Joseph, & Thompson, 2012;

Cairney, Boyle, Offord, & Racine, 2003).

Taylor describes single women status as “the allowed, endorsed, even celebrated; yet

simultaneously disavowed as that which must be pitied, scorned, and emptied of her oppositional

potential” (Taylor, 2012, p. 13). Furthermore, single women portrayed and reflected in media

culture are often depicted prejudicially with a tragic dichotomy that holds that for them

“public/professional competency equals private/personal incompetency” (Taylor, 2012, p. 14).

Low income does not necessarily reflect incompetency, just lack of financial success.

ௗFinancial Hardship and the Hunger of Low-Income Single Mothers

Financial hardship is the most common disadvantage that single mothers report. Single

mother families have much higher poverty rates than any other type of household, except those

of single women. Mothers often report difficulty in meeting their own and their child/children’s

needs on one salary (Baranowaska-5DWDMHWDOௗ'XULQJWKHHFRQRPLFUHFHVVLRQRI

the percentage of single mothers receiving food stamps increased from 28 to 39% (U.S. Census,

2013). However, this assistance is not always enough and is often time-limited (Broussard et al.,

2012).

Single women in all ethnicities have much lower incomes than single men (U.S. Census,

2014). U.S. census population studies show that in 2014 the median personal income of single

women and men was $26,673 and $39,181, respectively (U.S. Census, 2014). U.S. single

14

women’s income in 2011 was 32% less than single men, and the lowest income of any other type

of household studied (U.S. Census, 2014). This included overall family and nonfamily

households, family households with married couples, and female- or male-lead family

households. Also, single people in the U.S. in general have lower incomes than married people

with or without children: median incomes of all family households were $68,426 in 2014

compared to median nonfamily male or female-lead single household incomes of $32,047, and

the median married-couple with children income of $81,025 (U.S. Census, 2014).

Low-income single mothers with children are more likely to find housing help from

government or nonprofit organizations than homeless low-income single men with no children

(Passaro, 2014). People with children may more likely not remain homeless if they fall into

homelessness because of government housing organizations such as Aid to Families of

Dependent Children (Passaro, 2014).

Food insufficiency. Studies show that 31% of single mothers have food insufficiency

(Heflin et al., 2005). Heflin et al. (2005) define food insufficiency as not being able to acquire or

have certainty about having enough food to sustain oneself sufficiently to meet basic needs at

least one time during the year due to lack of enough resources. Lack of food is known to be

higher in people’s lives that remain under the poverty line and households headed by single

mothers. Hunger in one’s life may cause stress, self-blame, thinking oneself as not efficacious,

and loss of a sense of mastery, (Heflin et al., 2005), which are all factors that can lead to clinical

depression.

Womanhood and motherhood wage penalties. Wages of mothers in general are less

than other women (Budig & England, 2001). Having children may cause women to lose time at

work, be somewhat less productive due to family concerns, and to choose lower paying, family

15

friendly jobs. In addition, employers may discriminate against mothers (Budig & England,

2001). Overall, studies show that the wage penalty for motherhood is 7% and is higher for

married versus single women (Budig & England, 2001, p. 205). Budig and England (2001)

argue that mothers disproportionately bear the costs of child rearing in general in our society.

Furthermore, women in general have a gender wage penalty. For example, one recent study

showed that women who were one year out of college earned 89% of what men earned in

education, 86% of what men earned in business and management, and just 77% of what men

earned with the same circumstances in sales occupations (Corbett & Hill, 2012).

Cultural Characteristics of Single Mothers in the U.S.

The population of single mothers varies greatly by culture. In 2012 in the U.S., birthrates

for single mother households were 68% of African Americans, 43% of Latino children, 26% of

White children, and 11% of Asian children (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C.,

2012). In contrast, the percentage of single father households with children under the age of 18

IURPWRZDV%ODFNZHOOௗMany minority single mothers have low income

possibly due to the greater minority women’s poverty levels in general in the U.S. In 2011

“[w]ith regard to race and ethnicity, non-Hispanic White women were least likely to experience

poverty (10.6 percent), followed by non-Hispanic Asian women (11.9 percent). Relative to

White and Asian women, about one-quarter of Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic

American Indian/Alaska Native women lived in poverty” (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, B. D., &

Smith, J. C., 2012). “Relative to White and Asian single-mother households, Black and Hispanic

women (and their children) living in single-parent households are at high risk [40% higher] of

being in poverty” (Damaske, Bratter, & Frech, 2016, pp. 3 and 11; Lichter and Crowley, 2004;

and McLanahan and Percheski, 2008).

16

The median earnings of single female head of households with children was $31, 032

(DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C., 2012). Male-led family households without

wives earned $49,718. According to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, in 2015

the poverty level for single people is $11, 770; for two people, $15, 930; for three people,

$20,090, and so on. In 2010, 42.2 % of single mothers were under the poverty line. This was

close to three times the 15.1% poverty rate for the whole population. These statistics vary by

racial and ethnic group in 2010: 32.7%, 47.1%, and 50.3% of White, Black, and Latino single

mothers, respectively, lived below the poverty line (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

African American single mothers. Discrimination is widespread towards Black as well

as Latino Americans, who are the largest minority groups in the U.S. One study showed that

98.1% of Black participants had been the victim of racial discrimination within the past year,

64.2% had experienced discrimination from banks and universities, 54.8% from social workers,

medical doctors and counselors, and almost half of participants had been called a racist name

(Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). Black low income single moms may be more likely to live in

poverty due to “an accumulation of disadvantages” and “a lack of employment opportunities for

women of color in urban environments” (Damaske et al., 2016).

Possibly to couch socioeconomic and prejudicial systemic pressures, African American

family membership often goes beyond the nuclear family, one household, or even beyond blood

relatives. “Several generations of extended family members and fictive kin may live together to

maintain a strong network of social and economic support” (Murry, Bynum, Brody, Willert, &

Stephens, 2001, p. 136).

Despite economic difficulties and social prejudice, Black mothers who have high self-

esteem and believe that they are able to be good parents are more likely to have positive

17

parenting strategies that improve economic, mental health, and employment status (Murry,

Bynum, Brody, Willert, & Stephens, 2001).

Latina single mothers. These mothers may have become parents due to teenage

pregnancy or spousal abandonment, or the fact that motherhood is a “promise they can keep” due

to the stigma and real threat of common divorce (Falicov, 2014; Edin & Kefalas, 2011). Second

and third generation Latino people may have the same high divorce rate of 40 to 50% as the

national average, though first-generation families divorce far less (Falicov, 2014).

Racism and prejudice cast a shadow on the Latino experience in the U.S. Entrenched

negative stereotypes by the mainstream U.S. population include poverty, low levels of education,

and poor talents. These stereotypes undoubtedly result in often severe segregation at work,

home, and school (Suarez-Orozco & Paez, 2002; Falicov, 2014).

One common characteristic of first-generation Latina single mothers involved in

immigration is that Latina single mothers may suffer from transnational relationship stress,

which may even have resulted in their single low-income motherhood status. Spouses or

divorced fathers of children may not be able to enter or reenter the U.S. leaving single mothers to

find family, friends, and (hopefully) gainful employment to sustain themselves and their family.

These mothers try to make meaning out of these separations and actively seek to preserve these

relationships, with varying levels of success. However, Falicov (2014) holds that

communications and expressions of emotions by parents separated from their children

transnationally make a substantial contribution to existing and future family well-being (Falicov,

2014).

Incidentally, Latinas may choose abortion in more cases than in the past due to its more

prevalent legitimization in Latin America. This may result in smaller family sizes (Llana, 2007).

18

The right to abortion is spreading in Latin America but continues to be most intensely opposed in

all forms by Evangelicals (Llana, 2007). Alternative Latino family forms that differ from the

conventional heterosexual two-parent headed household recently include single parent, divorced,

remarried, same-sex, consensual unions, or living apart configurations (Falicov, 2014).

Asian single mothers. One recent study of Japanese single women found that reasons

for their singlehood stemmed from a male intimate partner’s reluctance to marry as well as

mixed feelings about men and relationships (Maeda & Hecht, 2012, p. 57). The women in this

study (the same group were sampled twice: once in 2003 [n=30] and in 2007 [n=20] three years

apart) were all over 30 and never been married with mean ages of 39 and 42. In this study, 93%

worked, 70% did not have intimate partners, and 27% had university or graduate degrees. Asian

women’s ability to achieve self-acceptance of their identity as single women and mothers over

time helps them cope with their alternative, nontraditional cultural lifestyle (Maeda & Hecht,

2012).

White single, low-income mothers. Though studies of specifically White single low-

income mothers appear to be sparse, one study with a primarily White sample concentrated on

the struggles that these women had to keep their jobs in the face of the challenges of single

parenting. Four main areas of concern were identified that appears to be fairly universal

regardless of ethnicity: “(a) demands from family and work, (b) resources the mothers used to

maintain their employment, (c) work-family conflict, and (d) strategies to retain employment”

(Son & Bauer, 2010).

Childcare was performed by extended family primarily. Some women received money

from older children who also cared for the household and younger brothers and sisters. Other

important though informal resources were neighbors, coworkers, and supervisors. Flexibility in

19

the workplace was key to a feeling of control over their family and work lives. Conflicts arose

due to their limited time to spend with their children, especially when they were ill. Job

insecurity arose when mothers missed work due to unexpected family demands. Fatigue resulted

from the combination of work and family demands (Son & Bauer, 2010).

Oppressive Social-Economic Environments and Reported Poor Mental Health of Low-

Income Single Mothers

Some researchers have claimed that in general married people are happier than unmarried

people. However, such cross-sectional research cannot support causal claims that married people

are happier because they got married. In fact, a review of 18 methodologically superior

longitudinal studies showed that people who marry do not become any happier than they were

when they were single, except occasionally for a brief increase in happiness around the time of

the wedding (Luhmann, Hofmann, Eid, & Lucas, 2012; DePaulo, 2013).

In addition, even the cross-sectional finding of marital advantage is a qualified one:

single people are generally as happy as married people when the local, regional, or national

communities and governments in which they live support alternative cohabitation or single adult

living; i.e., communities without singlism (stereotyping or stigmatizing of single adults)

(Vanassche, Swicegood, & Matthijs, 2013).

Common mental illnesses of low-income single mothers are substance abuse, anxiety,

stress, trauma, poor self-efficacy, distress, trauma and depression (Rousou, Kouta, Middleton, &

Karanikola, 2013; Goodman, Smyth, Borges & Singer, 2009; McLanahan, 2004; Nomaguchi &

Milkie, 2003). Brief or prolonged episodes of discrimination have been found in research to

have quantifiable, short term effect on victims (Dion & Earn, 1975). Study subjects performed

more poorly on cognitive tasks, behaved less generously to peers, and reported heightened levels

20

of “stress, aggression, sadness, egotism, and anxiety” (Dion & Earn, 1975). The widespread

cultural beliefs in the inferiority of Blacks and women, for example, have been shown to have

“insidious effects” called the “stereotype threat” (Steele, 1997). When Blacks and/or women are

reminded of these negative stereotypes shortly before attempting a difficult task, the fear that one

will prove the negative stereotype true may result in a major obstruction in performance levels

leading exactly to the consequences that the individual feared (Steele, 1997). Many single

mothers express being “looked down [on]” (Broussard et al., 2012, p. 193) as a result of the

challenges they face. These types of feelings evoked in an oppressive social-economic

environment may make single mothers more prone to depression and other mental illnesses

(Broussard et al., 2012).

Along with recovering from the possible trauma of domestic violence so prevalent in

lower income families, depression is common among people experiencing humiliation or

entrapment within “severe” lifetime events (Brown & Moran, 1997). These severe experiences

are more common in women suffering from financial difficulties (Brown & Moran, 1997).

Parents who report financial hardships appear to be at greater risk of depression (Kingston,

2013).

High occurrences of common mental disorders are found in 45% of single mothers as

compared to 23.6% of partnered mothers (Crosier, Butterworth, and Rodgers, 2007). Examples

of these disorders are anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder. Many of the possible

consequences of the disadvantages of being low income single mothers are possibly the result of

the long hours and chronic stress that single mothers may IDFH5RXVRXHWDOௗ

“…[W]omen who have been single mothers throughout a significant portion of their life course

are more likely than others to have trajectories of severe distress” (Avison et al., 2008, p. 248).

21

Trajectories of severe distress appear to be correlated with higher risk of depression earlier in the

life cycle, with depression in single mothers commonly being a relapse (Avison et al., 2008).

Raising children and having to play both father- and motherhood roles for their children

is exhausting. Additionally, single mothers tend to be young, which may intensify difficulties

(Cairney et al., 2003). In general, single mothers often report feeling tired, stressed, and

overwhelmed (Baranowaska-Rataj et al., 2014). Homeless mothers tend to suffer from

depression and substance abuse with greater severity than the general population (Bassuk et al.,

1998). Research also has shown that homeless mothers have a 72% probability of a substance

disorder, a mental disorder, or both (Zima, Wells, Benjamin, & Duan, 1996).

Environment. A common consequence of this low income are the neighborhoods in

which single mothers can afford. Low socioeconomic status may result in a single mother and

her children living in an unsafe area with minimal healthy and affordable recreational options for

children, and poor schooling (Kingston, 2013). Additionally, as a result of the economic

disadvantage that single mothers face, pursuing their own higher education becomes difficult

(Cairney et al., 2003).

Physical health effects. Physical health concerns are often present along with financial

stressors that a single mother goes through (Rousou et al., 2013). Single mothers often report

high and chronic levels of stress (Cairney et al., 2003). These mothers express consistent worry

regarding housing, food insecurity, and safety (Broussard et al., 2012). In tandem with chronic

stressors faced, single mothers may be more prone towards an impaired immune system,

diabetes, joint pains, and obesity (Broussard et al., 2012). However, as a result of the need to

address the hardships at hand (particularly if they impact the children), single mothers report

ignoring their own health (Broussard et al., 2012).

22

Isolation and lack of social support. Unless single parents are cohabitating or in

significant relationship, they often lack the support that would be provided by a partner

(Kingston, 2013). Lack of social support and their perceived social support that a single mother

encounters appear to influence their mental health as well (Kingston, 2013). One possible factor

that may contribute to lack of social or familial support is the mother’s cultural background

(Kingston, 2013). While cultural background may hamper the social support that is received, the

high demands that a single mother faces may also impede a mother’s ability to socialize, and

therefore, they may become socially isolated (Cairney et al., 2003). In addition to financial

stressors, health concerns, and social stigma, single mothers may struggle when attempting to

engage in romantic relationships (Baranowaska-Rataj et al., 2014). In conclusion, the social

inequality of women in general, higher poverty rates, and high levels of traumatization of low-

income single mothers all may lead to higher rates of substance use and the difficulties of

divorce with children.

Potential Mitigating Factors and Intervention Strategies

Mitigating factors in the literature that may be a part of effective clinical interventions are

helping to foster cultural and nuclear family ties, the recognition of motherhood as a sustaining

factor, and validating the positive effects of work, quality childcare, fathers who care, and public

assistance. In addition, Damaske et al. (2016) found that public assistance may or may not help

improve economic status in that it may not raise these families above low-income levels, but

public assistance such as food stamps, and health and childcare can “buffer” the ill effects of

poverty.

Cairney et al. (2003) found that many single mothers had a significant amount of

childhood adversity. As a result, Cairney et al. (2003) argued that single mother’s exposure to

23

dealing and coping with adversities throughout their life allows them to be less affected by their

negative experiences. This argument adds to the consistent theme that although single mothers

face several disadvantages and challenges as a single parent, they enjoy the benefits of being a

parent (Baranowaska-Rataj et al., 2014). For many, even if the pregnancy is unplanned, it

becomes a motivating factor to take positive steps in their life (Baranowaska-Rataj et al., 2014).

Zabkiewicz (2010) found that full-time, or consistent long-term employment improves

mental health of poor single mothers. The sample location used in this study has been used

consistently in population-based research. Of the 1,510 low-income mothers on aide in Northern

California that participated in the study, 77% were not married or cohabitating and more than

half said that they received no family support. One-third of these mothers had more than three

children, and 61% had a child younger than 4 years old. The ages of the women were almost

equally divided: 19-24 (34%), 25-34 (39%), and 35+ (27%). Most beneficiaries were Black

(38.2%), followed by White (29%), Latina (19%), and other minorities (13.7).

McCartney, Dearing, Taylor, & Bub (2007) studied the effects of mediocre and quality

childcare on the well-being of low-income single mothers and their children. This study found

that high quality childcare can buffer the deleterious effects of poverty. The positive children’s

outcomes were school readiness, receptive language, and expressive language. For low-income

children, even poor quality childcare was shown to improve language outcomes.

Though co-resident low income fathers typically spend more time with their children, one

cannot over stress the important benefits that a nonresident low income father can provide their

children (and, therefore, indirectly to their mother) by way of formal and informal financial

support and positive interactions with them (Carlson & Magnuson, 2011). Unmarried fathers

typically provide informal, but not formal (mandated), financial support particularly around

24

childbirth, but in five years, 47% of mothers may have child support in place (Nepomnyaschy &

Garfinkel, 2008). Child support has been shown to positively affect child outcomes (Carlson &

Magnuson, 2011). Encouraging mothers to reach out to the fathers of their children for help if

they can be reasonable interpersonally, may aide the family greatly. Therapists can encourage

mothers by pointing out these mitigating factors that can greatly ameliorate the struggles of low-

income families headed by single mothers, but statistics show that this population and their

poverty are growing.

The Effects of Nature on Mental Health

Ecotherapy techniques may also mitigate the mental illnesses that are typical of low-

income single mothers. For example, time spent experiencing or viewing natural settings, such as

viewing gardens or gardening or experiencing wilderness, may foster better psychological well-

being (Doherty, 2016; Doherty & Chen, 2016; Grahn & Stigsdotter, 2010; Berman, Jones, and

Kaplan, 2008; Berto, 2005; Kaplan, 1973). Viewing natural settings has also been associated

with improved cognitive functioning (Tennessen & Cimprich, 1995), and may speed recovery

from illnesses (Verderber & Reuman, 1987). Because stress is an overarching dependent

variable that adversely effects both mental and physical health, Ulrich et al. (1991) researched

the effects of viewing natural and urban environments on stress. Several theoretical perspectives

converged to stimulate Ulrich’s hypothesis that views of nonthreatening natural settings would

allow for greater recovery from stress than views of urban settings.

Many Western cultural beliefs dating back to Roman times allude to the value of nature

to counteract the loud noises, crowdedness, and other stressors of city life (Glacken, 1967). In

Western modern cultures, the tendency to revere nature and dislike cities could be influenced by

the tendency to recreate in rural areas. Natural settings may have lower levels of overt

25

complexity and other arousing attributes than urban areas, thus making natural views or settings

more recuperative following a stressor (Cohen, 1978). Evolutionary theories postulate that

humans evolved for a long period of time in the natural environment and that, therefore, we may

in general have an instinctual positive response to nonthreatening natural content such as flora

and water (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Ulrich, 1983; and Orians, 1986).

In the psychology field, the therapeutic fields of ecotherapy, ecopsychology,

environmental psychology, and adventure therapy all have incorporated the healing properties of

nature into various treatments for mental and physical illnesses with varying degrees of

successful results (For a comprehensive survey of studies, theoretical perspectives, and

commentaries, see Doherty & Chen (2016) and Doherty (2016).

Evidence-based studies on the healing properties of natural settings generally substantiate

the efficacy of nature-related mental health treatments. In addition, studies suggest that further

research is needed to determine whether certain mentally ill populations would benefit from

psychotherapy combined with nature as an added tool. Very few empirical studies currently

exist that study the effects of exposure to nature on the mental health of specific populations

(Chalquist, 2009).

The subjects of Ulrich’s study were 120 undergraduate volunteers of equal gender at the

University of Delaware who were diversified as far as their current course of study. The study

was done in a laboratory setting. Participants were first shown a stressful movie and then one of

six videos of urban and natural settings. The use of video instead of live experience in this

instance has been shown to be statistically similar enough for research purposes (Zube, Vining,

Law, and Bechtel, 1985). Physiological measures of EKG, pulse transit time (PTT), spontaneous

skin conductance responding (SCR), and frontalis muscle tension (EMG) were recorded from all

26

subjects. Participants were asked to verbally rate their feelings before and after the stressor and

recovery tapes using the Zuckerman Inventory of Personal Reactions (ZIPERS) (Zuckerman,

1977). Both physiological and self-reported feelings measures indicated that recovery from

stress was much quicker and more thorough when participants viewed natural settings rather than

a pedestrian mall or street traffic environments (see Figures 1-4). One significant result was the

rapid speed of recovery while viewing natural settings to a higher level than the original baseline

level, which suggest that further nonlaboratory studies of short-term real contexts with nature or

viewing nature out a window may show positive results as well.

In 1995 a study confirmed Ulrich’s hunch that even modest exposure to natural settings

could have substantial mental benefit. Tennessen & Cimprich (1995) measured the effects that

all-natural views out of a window could have on students versus students without all-natural

views. Researchers hypothesized from several theoretical perspectives that having an all-natural

or partially natural view would aid in restoring attention fatigue far greater than a view of other

buildings.

Directed attention is defined as the extent to which people can block competing input or

distractions during intentional activity (Posner & Snyder, 1975; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1982). This

capacity is essential for performing many mental tasks: selecting and retrieving information,

planning, and responding and behaving in ways that allow for meeting goals. Lack of directed

attention abilities could lead, in the worst case, to an inability to be effective in daily life.

Kaplan & Kaplan (1989) theorized that four factors are involved in an attention-restoring

experience: fascination, a sense of being away, sufficient extent, and compatibility.

27

Figure 1. Alterations in Skin Conductance (SCR) in stress and recovery (Ulrich et al., 1991).

There is a temporary drop during the stress and also in the recovery phase when stress is turned

off. (Permission to reuse this figure was received from the author.)

Figure 2. Alterations in Pulse Transit Time (PTT) During Stress and Recovery (Ulrich et al.,

1991). The pedestrian mall and traffic views are seen to arouse rather to restore during the

recovery phase. (Permission to reuse this figure was received from the author.)

28

Figure 3. Alterations in muscle tension (EMG) during stress and recovery (Ulrich et al., 1991).

The pedestrian mall and traffic views are seen to arouse rather to restore during the recovery

phase. (Permission to reuse this figure was received from the author.)

Figure 4. Alterations in heart period during stress and recovery (Ulrich et al., 1991). This

measure is an indicator of intake/attention, unlike the other measures. (Permission to reuse this

figure was received from the author.)

29

Seventy-two undergraduate students were categorized into four similar groups that

ranged from all-natural views to all built views at a large Midwestern university, with most of

the students being juniors or seniors. Participants were administered tests once in their rooms

with neurocognitive and directed attention measures: the Digit Span Forward (DSFT) and

Backward (DSFT) and Symbol Digit Modalities (SDMT) (Lezak, 1983), the Necker Cube

Pattern Control Test (NCPC) (Cimprich, 1993), and a subjective rating using the Attentional

Function Index. Data that showed sample size of all-natural view with n = 10 should not be

considered because of the low sample size.

This study concluded that university students with views of natural settings may have

benefited from increased ability and capacity to direct attention. The only measures that showed

significant effects were the SDMT (All and Mostly Natural = 68.95; Mostly & All Built = 62.29)

and the NCPC (All & Mostly Natural = - 62.35%; Mostly & All Built = -35.87%). All others

had probability that was higher than 0.05. In addition, the sample size of 20 is low that grouped

All & Mostly Natural statistics. Nevertheless, SDMT measures directed attention when the

subject is performing complex tasks, and NCPC measures the ability to block out competing

stimuli. These measures are key in directed attention and when combined, validate the

hypothesis that for these university students, their natural views promoted greater directed

attention ability.

In 2012, Raanaas, Patil, and Hartig studied the effects of windows to natural settings on

patients in a rehabilitation center with similar, but not as comprehensive, results. In a quasi-

experimental study, they hypothesized that based on past studies such as by Ulrich et al. (1991)

and Tennessen & Cimprich (1995) a private room with a window view to a natural setting would

30

have healthy effects on rehabilitation patients and their general well-being. Three types of

window views were used in the study with blocked, medium, and high nature views. Patients

were tested at five different time points from arrival at the center to two weeks after returning

home, with 250 lung patients and 345 heart patients used 52 rooms. Outcome measures were

self-reports.

Clients with panorama views were most satisfied and in blocked-view rooms, least

satisfied. Patients with panoramic views used their room to withdraw for privacy possibly

alleviating the demands of the center and their difficult health issues. Findings supported

Ulrich’s view that passive contact with natural settings may help patients cope better with the

difficulties of illness. This study did differ from Ulrich’s study in that a blocked view did not

adversely affect the mental health of women as it did men during their stay, but women were

more positively impacted by a panoramic view than men. Also, no effect was shown on

emotional states or subjective well-being (Raanaas et al., 2012, p. 31). This could have been due

to a greater emphasis on health perceived in the preceding week. Lung patients had more

positive effects than heart patients. The researchers hypothesized that this could have been due

to greater restraints that patients must undergo in their treatment which would lend themselves to

greater appreciation of views due to their forced stationary situations. The recommendation

based on this study is that particularly vulnerable patients should be given the nicest views.

To find buffers for the toils and adversity in the lives of children, researchers in 2003

studied 337 children who lived in rural areas (Wells & Evans, 2003). Though many studies

found that adult time spent in natural environments is associated with better mental wellbeing,

researchers were beginning to substantiate these findings in children. Children’s preference for

running free in the outdoors could stem from an evolutionary bias and an affinity for places

31

where they may not only enjoy but thrive. Nature as a hypothesized buffer could attenuate

adverse effects of stress or other large, negative effects that degrade good health or well-being.

Socio-economic levels of the children were controlled because it is another independent variable

due to its potential effect on children’s health and well-being. Their mean age was 9.2 years.

Findings showed in Table 1 that the effect of life stress and life stress with nature on

psychological stress was 53.14 to 4.73 F, respectively, which was a very large decrease in stress

levels as a result of association with natural surroundings. (Permission to reuse this table was

received from the author. See Appendix C) In Table 2, the effect of life stress and life stress

plus natural surroundings on the children’s global self-worth were also considerably positively

impacted: 40.54 to 10.64 F, respectively. Figure 5 indicates the effects of low to high nature on

psychological stress revealing that nature was particularly beneficial for highly stressful life

events (Wells & Evans, 2003).

Table 1.

Regression of Children’s Psychological Distress (Rutter) Onto Nature, Life Stress, and the

Interaction of Stress x Nature, Controlling for Income (Wells & Evans, 2003). (Permission to

reuse this table was received from the author.)

32

Table 2

Regression of Children’s Global Self-Worth Onto Nature, Stressful Life Events, and Interaction

of Stress x Nature, Controlling for Income of Family (Wells & Evans, 2003). (Permission to

reuse this table was received from the authors.)

Figure 5. Nature moderated effects of stressful life events on psychological distress.

(Permission to reuse this figure was received from the author.)

33

Karmanov & Hamel (2008) argued that urban environments could meet the same

standards that Kaplan & Kaplan (1989) identifies for the four restorative environmental qualities

of the feeling being away, fascination, sufficient extent, and compatible with human needs. In

this way, they hypothesized and attempted to show empirically that well-designed and attractive

urban environments may have a stress-ameliorating and mood regulating quality equal to a

nonthreatening natural setting. To do this, he compared Amstellan in The Netherlands with a

newly developed area of excellent architectural quality with front gardens, lots of water, and

canals of different shapes with various levels of traffic. He also added cultural information as an

independent variable to show the impact of knowledge, or narrative, on the experience of places.

He hypothesized that a well-designed urban area with its own narrative would have the same

effect as natural surroundings on mental states.

Participants in the study were 86 freshman and sophomore psychology students from the

University of Amsterdam (63.5% females and 36.5% males, with an average age of 21.5 (S.D. =

5.1). They were randomly assigned to four groups: two natural setting groups with or without

narratives, and urban settings with or without narratives. The number of participants in these

groups was 26, 21, 19, and 19, respectively. Researchers controlled for equal types of

participants in both groups, verifying that the natural environment selected was indeed

considered such, and ruled out any effect of the commentary on the videos that were shown to

depict natural and urban environments. Results are shown in Table 3. (Permission to reuse this

table was received from the author.) These researchers theorized that a combination of water,

green spaces, and design in the urban space selected lead to raising its positive mental effects as

high as a natural setting in most ways. The exception was that the urban setting did not restore

depression as well as the natural setting, based on the data shown in Table 3.

34

Table 3