ORIGINAL RESEARCH

published: 26 March 2021

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.580992

A Thematic Analysis of Multiple

Pathways Between Nature

Engagement Activities and

Well-Being

Anam Iqbal and Warren Mansell*

Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, School of Health Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Edited by:

Eric Brymer,

Australian College of Applied

Psychology (ACAP), Australia

Reviewed by:

Kathryn Jane Hoffmann Williams,

The University of Melbourne, Australia

Sonia Maria Guedes Gondim,

Federal University of Bahia, Brazil

*Correspondence:

Warren Mansell

warren.mansell@manchester.ac.uk

Specialty section:

This article was submitted to

Environmental Psychology,

a section of the journal

Frontiers in Psychology

Received: 07 July 2020

Accepted: 26 February 2021

Published: 26 March 2021

Citation:

Iqbal A and Mansell W (2021) A

Thematic Analysis of Multiple

Pathways Between Nature

Engagement Activities and Well-Being.

Front. Psychol. 12:580992.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.580992

Research studies have identified various different mechanisms in the effects of nature

engagement on well-being and mental health. However, rarely are multiple pathways

examined in the same study and little use has been made of first-hand, experiential

accounts through interviews. Therefore, a semi-structured interview was conducted with

seven female students who identified the role of nature engagement in their well-being

and mental health. After applying thematic analysis, 11 themes were extracted from

the data set, which were: “enjoying the different sensory input,” “calm nature facilitates

a calm mood,” “enhancing decision making and forming action plans,” “enhancing

efficiency and productivity,” “alleviating pressure from society’s expectations regarding

education,” “formation of community relations,” “nature puts things into perspective,”

“liking the contrast from the urban environment,” “feel freedom,” “coping mechanism,”

and “anxious if prevented or restricted.” The results indicate complementary mechanisms

for how nature-related activities benefit mental health and well-being that may occupy

different levels of experience within a hierarchical framework informed by perceptual

control theory.

Keywords: nature engagement, eco psychology, mental health, environment, well-being, mechanisms of change

INTRODUCTION

It has become increasingly recognized that nature engagement activities provide a convenient,

effective, community-wide means to support mental health and well-being, especially during

childhood (Bragg and Atkins, 2016). A recent Delphi study of 19 experts from seven countries

collated the diverse range of nature engagement interventions and their potential well-being and

health outcomes (Shanahan et al., 2019). They encompass ways to change people’s surroundings

(e.g., parks, workplaces), and widespread types of activities (e.g., adventure sports, wilderness play,

outdoor therapy). Well-being has been conceptualized from a range of perspectives, including

subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1999), social well-being (Larson, 1993), and psychological

well-being (Ryff and Keyes, 1995). Each of these perspectives on well-being presents multifaceted

constructs. For example, subjective well-being includes the phenomena of pleasant and unpleasant

affect, life satisfaction and satisfaction in specific domains (e.g., work, family, health) (Diener

et al., 1999). Social well-being combines social adjustment (including relationship satisfaction) and

social support from one’s network of contacts (Larson, 1993). Psychological well-being is also a

multifaceted construct (Ryff and Keyes, 1995) and includes autonomy, environmental mastery,

personal growth, positive relations, purpose in life and self-acceptance; these elements are generally

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

1

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

considered to hold value (also known as eudaimonic well-being)

but not necessarily pleasure (hedonic well-being). A wide range

of inter-related mechanisms through which nature engagement

may have its effects on well-being have been put forward, but

rarely are they studied together, nor have the mechanisms been

analyzed in the context of different perspectives on well-being.

The current study aimed to discover the first-hand experience

of potential mechanisms by interviewing seven people who

identified as utilizing nature engagement for their well-being

and mental health. We did not impose a specific well-being

perspective but allowed participants to generate the facets of

well-being that were meaningful to them.

A number of theories are grounded in evolution theory,

pointing to the natural affinity of humans for natural

environments, animals and plants—commonly described as

the biophilia hypothesis (Wilson, 1984; Kellert and Wilson,

1995; Ewert et al., 2014). The sensory input from nature

itself may reduce anxiety, owing to an innate drive to seek

sensory experiences that eminate from nature (Ewert et al.,

2014). These experiential properties may allow the individual

to meet fundamental needs (Landon et al., 2020) such as

autonomy, competence and relatedness, as specified by Self-

Determination Theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan, 1985). The visual

qualities of natural scenes are the focus of Stress Reduction

Theory (Ulrich, 1983; Ulrich et al., 1991) that specifies the

“preferenda”—the aesthetic qualities of natural scenes—that

entail specific affective, cognitive and physiological states.

These include the textures, depth cues, level of complexity, and

configurations within a natural environment, and they engage

specific psychoevolutionary modes, such as the pleasant affect

linked to exploration and approach throughout an environment

containing depth and complexity.

There is consistent evidence from early studies that the visual

perception of natural environments can improve indices of well-

being, such as reduced anxiety, pro-social behavior and reduced

physiological symptoms of stress (Berto, 2014). A meta-analysis

of 32 studies found that contact with natural environments was

associated with a moderate increase positive affect and a smaller,

but statistically robust, decrease in negative affect (McMahan

and Estes, 2015). Specifically, there is emerging evidence for the

proposal that it is the fractal geometry of visual scenes of nature

that is unique, provides aesthetic pleasure, and may specifically

engage this mode of attention (Purcell et al., 2001). In turn,

it is proposed that when a person becomes aware of these

perceptual qualities of nature, they experience a connectedness

to nature that is part of their identity (Heerwagen and Orians,

2002; Schultz, 2002). The Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS)

is a standardized self-report scale to assess this construct (Mayer

and Frantz, 2004). It correlates with overall life satisfaction and

various facets of well-being (Mayer and Frantz, 2004; Howell

et al., 2011; Wolsko and Lindberg, 2013). Consistent with this

view, engagement with natural beauty has been found to mediate

the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being

(Zhang et al., 2014).

Attention restoration theory (ART) suggests that spending

time perceiving nature helps to improve focus and concentration

levels through replenish an attentional resource required to

focus and inhibit distractions (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989; Kaplan,

1995). Emerging evidence from the beneficial effects of nature on

cognitive task performance supports this proposal (Berto, 2014),

including a meta-analysis of 42 studies in which improvements

in working memory and cognitive flexibility were identified

(Stevenson et al., 2018). It is claimed that nature engagement

creates these effects by engaging a model of attention known

as “fascination” that is effortless, thereby allowing attentional

resource to be restored.

A distinct but related approach points to the role of nature

engagement in helping to balance the biological systems for

managing threat, pursuing reward and seeking comfort to restore

homeostasis and allow self-reflection (Richardson, 2019). This

approach links nature engagement to the understanding of

compassion and mindfulness. For example, there is also emerging

evidence that nature connectedness correlates with other factors

involving attention–particularly mindfulness, as supported by a

recent meta-analysis of 12 studies (Schutte and Malouff, 2018).

The relationships vary depending on the facet of mindfulness

assessed, and there are indications that reflective self-attention

may indeed be the closer correlate (Richardson and Sheffield,

2015). The self-regulation approach builds on evidence of this

kind, in describing the processes through which many aspects

of the self—mastery, attitudes, values—are regulated (Korpela,

1995). Yet a further strand of research goes beyond self-

reflection, to assess the role of awareness of a superordinate

perspective on the world, akin to mysticism or spirituality

(ecological-self theory, Bragg, 1996; transpersonal psychology,

Ferrer, 2002; general sense of connectedness, Passmore and

Holder, 2017), and there is evidence that this also mediates

between connection to nature and well-being (Kamitsis and

Francis, 2013; Trigwell et al., 2014). Most recently, drawing upon

Gibson’s work (e.g., Gibson, 1979), an ecological stance toward

nature connection has been described to explain the capacity

for nature to enable healthy actions through its wide variety

of affordances and niches, such as trees to climb and a wide

expanse to explore (Araújo et al., 2019; Brymer et al., 2020).

This ecological stance has been encapsulated within a broader

humanistic and existential approach to explain, for example, the

benefits of extreme sports in natural environments (Immonen

et al., 2018). A related conceptualization utilizes attachment

theory and phenomenology to describe the way that people’s

fundamental relationships with nature (e.g., as a secure base; as

an embodied interaction) contribute to, and support, the sense of

self (Schweitzer et al., 2018).

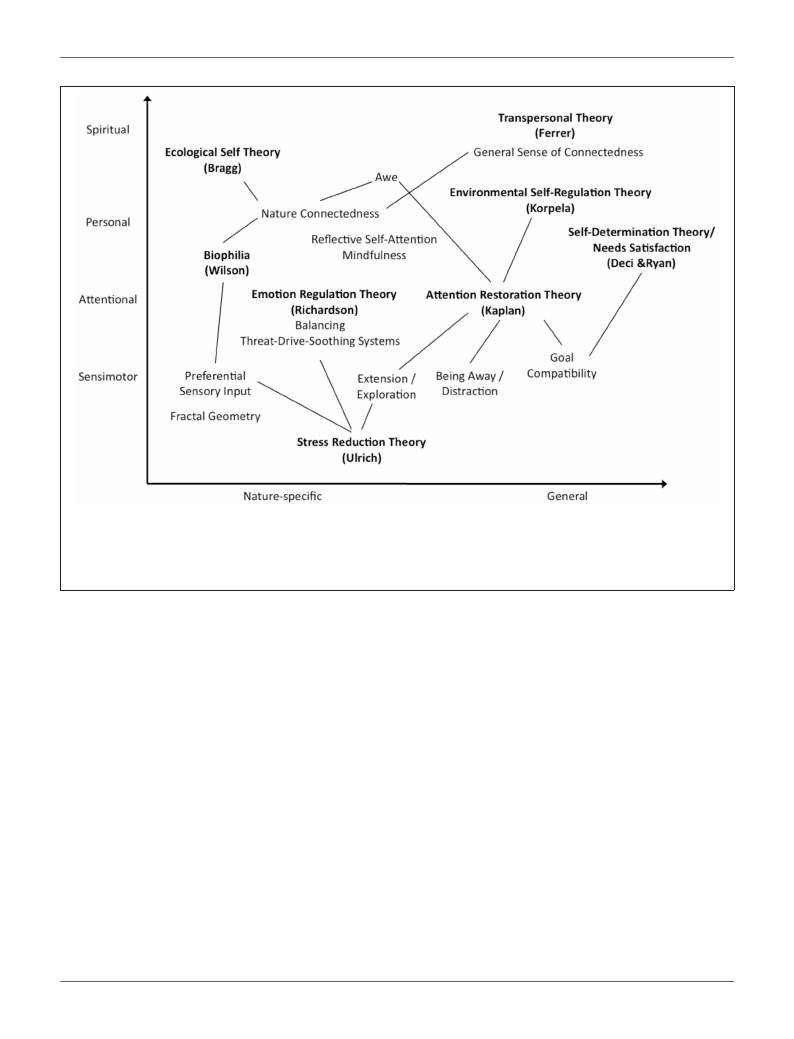

In order to attempt to organize this literature, Figure 1

displays the main theories of nature engagement alongside the

main mechanisms of action that they specify. Provisionally, these

can be organized in two dimensions to show their approximate

relationship. They vary in the level of process that they tend to

describe–sensimotor control, attention, self, spiritual—and they

vary in terms of the degree to which their mechanisms are specific

to nature or more widely applicable. There is however no formal

assessment of their overlap, and it is the aim of the current study

to focus on specifying mechanisms from the perspective of the

individual engaging with nature.

The research literature clearly points to a number of

mechanisms. Whilst theories such as ART and ecological-self

theory clearly presume a complex inter-relationship between

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

2

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

FIGURE 1 | A visualization of the relationship between theories of the well-being benefits of nature engagement. The x-axis represents the degree to which the theory

tends to focus on mechanisms that are specific to the biological affinity of humans with natural environments (e.g., evolved biological systems, ecological identity), vs.

more general psychological mechanisms that are nonetheless facilitated by nature (e.g., attention, self-regulation), and the y-axis represents the level of abstraction of

the components of the theory, from sensimotor processes, through attentional, personal (self-related), and spiritual (transpersonal) components. The

ecological-existential/phenomenological-psychoanalytical approach by Brymer et al. encompasses the full spectrum of both axes.

mechanisms at multiple levels—sensory, attentional, self-

concept, spiritual—this provides a challenge for quantitative

research and statistical modeling. In contrast, this challenge may

be addressed by an interdisciplinary framework grounded in

biology and engineering, known as perceptual control theory

(PCT; Powers et al., 1960a,b; Powers, 1973, 2008). It may

be more productive to utilize a theory that is universal and

interdisciplinary so that: (a) the biopsychosocial domains of

nature engagement can be integrated, and (b) the benefits of

nature engagement can be integrated with other interventions

such as psychological therapy (e.g., Greenleaf et al., 2014; Jordan,

2014), sports (Barton and Pretty, 2010; Allan et al., 2020), and

the arts (Case, 2005).

PCT proposes that organisms control their sensory input

through a process that is an extension of homeostasis, mediated

externally. Humans, and other organisms, achieve and maintain

internal reference values for sensory input at their desired

states by acting against disturbances in the environment. These

controlled perceptions of the self and the environment are

organized hierarchically such that more abstract, long-term

experiences are maintained through setting the reference values

of the next level down. For example, a person who wants to

live a worthwhile life may uphold principles regarding their

affinity with nature, which entails that they go for regular hikes,

during which time they search out and attend to configurations

of the natural world that they find calming and pleasurable.

Table 1 illustrates 11 levels of perception in PCT and provides

examples within nature engagement. Note that in PCT, action

is used to control sensory input via “feedback functions” in the

environment; this contrasts with the view that affordances in the

environment provide sensory input to drive action, as proposed

within ecological psychology (Gibson, 1979).

PCT proposes that chronic disruptions in well-being can

emerge from internal conflict; this is the attempt to make

an experience match two or more, incompatible reference

values. When this occurs, attention needs to be directed and

sustained above the systems in conflict so that an intrinsic,

trial-and-error learning process, known as reorganization, can

adjust neural strengths and connections until the conflict

is resolved. Thus, PCT provides a biologically grounded

framework for human decision making, conflict resolution,

well-being enhancement and maintenance (Carey et al., 2014);

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

3

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

TABLE 1 | The perceptual levels within PCT (Powers, 1998) and examples of how

they may be involved during nature engagement.

Name of Level Definition

The perceptual levels

within one example of

nature engagement

System concepts

Principles

Programs

Sequences

Categories

Relationships

Events

Transitions

Configurations

Sensations

Intensities

Conceptual organizations of

principles

Abstracted rules, values and

standards

Nested structures of test

and choice points regarding

sequences

Experiences that occur in a

specific temporal order

Classes of perceptions that

have shared characteristics

The ways in which two or

more lower level perceptions

relate to one another

A short, immediate,

succession of transitions

A change in configuration

over time, e.g., closing,

extending

A combination of sensations

that is perceived as a

distinct object

A vector of intensities

A signal directly from a

sensory organ

Being a nature lover

Getting the most of being

outdoors

Tree climbing

Get up the tree; sitting on

branch; looking at view

Seeing many different trees

Getting on top of a branch

A “step” upwards

The bending of the

branches

The shape of the branches

The green color of leaves

The brightness of reflected

sunlight from the tree

This table is organized with the higher levels at the top, but it is best read from the bottom

upwards because each higher level perception is formed from the perceptual levels below.

The hierarchy is branched rather than linear, but for ease of explanation, just one example

is provided at each level.

it also provides a framework for computational modeling of

psychological pathways (Mansell and Huddy, 2020). Notably,

PCT has influenced the development of theories used within the

nature engagement field such as choice theory (Glasser, 1981)

and wild system theory (Jordan, 2008). PCT also has an evidence

base across the disciplines most relevant to nature engagement,

including ethology (Pellis and Bell, 2020), neuroscience (Yin,

2017), mental health (Alsawy et al., 2014), and sociology

(McClelland, 2020).

Whilst an advanced quantitative research design might model

and test potential pathways from nature to well-being specified

by PCT in the future, an empirical bridge can be provided

by qualitative research. Within open self-reports, people who

perceive improvements in well-being from engaging with nature

can, within the limits of introspection, provide multiple themes

regarding the mechanisms they notice as important.

Examples of the most relevant qualitative research studies that

have explored the pathways from nature engagement to well-

being are summarized in Table 2. There are many more examples

of studies that have focused on specific activities, such as various

hobbies and sports, which are not summarized here.

The qualitative studies to date have echoed the findings

within the quantitative research, but this small number of

TABLE 2 | Examples of earlier qualitative studies and their findings regarding the

pathways between nature engagement and well-being.

References Methods

Key findings

Windhorst and 12 students prompted to Participants chose environments

Williams (2015) photograph the elements of that were familiar, an escape, and

their natural environment enabled self-reflection

that they felt contributed to

their well-being and mental

health

Martyn and

Brymer (2016)

305 students. Analysis of

text-based answers to the

question of “what being in

nature means to you”

Seven themes: sensory

engagement, expanse, connection

(including social and nature

connectedness), time out,

relaxation, enjoyment (including

feelings of restoration), and a

healthy perspective

McCree et al.

(2018)

11 disadvantaged children

given highly interactive,

child-centered interviews

A meta-theme of “establishing

self-regulation and resilience

through emotional space.”

Additional themes of autonomy,

freedom, meeting basic needs,

engaging in physically adventurous

activity, free social play, discovering

about nature, becoming socially

confident learners, making choices,

and gaining independence

Coventry et al. 45 adults engaging in

(2019)

conservation activities in

public green spaces

Degree of personal meaningfulness

and control over the specific activity

related to a sense of satisfaction

Birch et al.

(2020)

24 young multi-ethnic urban Three themes of relational felt sense

residents

within nature were described:

self-acceptance, escape, and

connection and care

Brymer et al.

(2021)

15 people who reported

enhanced well-being from

leisure activities in nature

Three overarching themes were “a

sense of perspective,” “mental and

emotional sanctuary,” and “being

immersed in the moment,”

supporting an interactive

relationship between people and

the natural environment

studies has also expanded the scope of mechanisms at

multiple levels of experience (sensory, attentional, self-concept,

etc), and across intrapersonal, interpersonal and systemic

(e.g., school) domains. The most prominent strand running

through them appeared to be how natural environments

provide a spectrum of opportunities for people of all ages

to meet their multiple biological and psychological needs:

independence/autonomy/control, physical activity, emotional

expression and problem resolution, play, discovery, personal

growth, self-reflection, self-acceptance, and social connectedness.

Given the limited number of studies, but their wide scope and

limited integration to date, we designed an interview study that

aimed to identify and organize the potential pathways within an

interdisciplinary framework.

In order to meet the above aim, we required a methodology

that met the following criteria: (1) a sample who identified

that nature engagement activities had benefited their well-being

and/or mental health and were therefore motivated to talk in

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

4

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

detail about potential mechanisms; (2) a convenient sample

that were articulate, available to devote the time, and able to

reflect on the benefits that nature had during their lives—

therefore undergraduate university students were recruited; (3)

a semi-structured interview that focused on identifying potential

pathways that emerged from the participants themselves, rather

than specific questions regarding specific pathways. We aimed

to compare our findings with the wider empirical literature to

interpret them within the context of theories of the benefits

of nature engagement and the nature of subjective, social and

psychological well-being. In order to do so, we adopted an

inductive approach, guided by the idiosyncratic experiences of

the clients. Following this we examined existing gaps in theory

and explored whether PCT might help integrate the pathways

within an analytical model, specific to the findings of the

current study.

bottom-up approach to identify themes. The first step the first

author took in generating themes was by familiarizing and

understanding the data set. The first author read the transcripts

multiple times to get to know the data set and to think if there are

any common answers or patterns thought all the interviews. Then

the first author started to code the transcripts, which allowed

her to develop an understanding of the data set further. The

first author then grouped the common codes into meaningful

categories, narrowing the choices for themes. The next step was to

make potential themes, which resulted in 11 themes. Finally, the

second author reviewed the themes and their associated quotes.

After discussion, it was decided that the previous names did not

accurately capture the essence of each theme and so these were

updated and finalized.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

METHODS

Design

This study used qualitative research methods, through a semi-

structured interview.

Participants

The study was advertised through an email from the university

communication email service, requesting for undergraduate

students who have experiences with nature engagement in their

childhood and adolescence, and who are willing to talk about the

role of experience with nature in their mental health and well-

being. Table 3 shows the participants demographics and what

nature-related activities they engaged in.

Materials

The topic guide was developed by the first author, reviewed

and discussed with the second author, and piloted with two

individuals reporting benefits of nature engagement before being

refined as the study version (Table 4), The interviews were

recorded using an encrypted audio recorder.

Procedure

After establishing email contact, the participants were emailed

an information sheet about the study, explaining the aims of

the study and what was required of them. The interviews took

place in a testing cubicle in the Psychology department of the

university. When the participant arrived at the interview, they

were asked to complete a consent form and a short demographic

form. The semi-structured interviews was conducted, the

participants were thanked for taking part in the study and they

had the opportunity to ask any questions.

All the interviews were transcribed. After the recordings were

fully transcribed, each audio recording was deleted from the

encrypted file. The first author carried out a thematic analysis

using Braun and Clarke’s guidelines (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Thematic analysis is a technique to categorize themes and

patterns across a dataset about the research question (Braun

and Clarke, 2013). Thematic analysis is flexible, allowing the

researcher to answer a research question with ease. It uses a

After applying thematic analysis to the transcriptions, 11 themes

emerged from the data set. These will be explained in a

hierarchical order from sensory experiences upwards, similar to

the vertical dimension of Table 1 and Figure 1, culminating in

the themes that illustrate the apparent overall function of nature

engagement in participants’ lives. Each theme is discussed in

relation to the wider theory and evidence, and a complementary,

integrative role of PCT is introduced.

Theme 1: Enjoy the Different Sensory

Inputs

This theme is about how the participants enjoyed the sensory

input they received from nature, such as visual, auditory, tactile,

and olfactory. The sensory input gave the participants a pleasing

sensory experience. The participants explained how they highly

appreciated different sensory contributions. Some participants

explained that they valued a broad horizon and the different

colors from the natural environment, other valued the quietness

and the sounds that came from natural sources such as trees, or

the smell of nature, or even the feeling of grass. Polly said:

“When I go home, I just feel so much better and as much as

I enjoy being at uni and it’s a whole new different lease of

life, going home, seeing the stars again because there’s no light

pollution, lying on the ground feeling the grass.”

This demonstrated that the participants liked the simple effects

that nature gave them, possibly due to the minimal effort

for mental processing. It was easy for them to take in the

different sensory experiences; it does not involve feelings of stress

or anxiety. In the natural environment, there are no proper

requirements. Therefore, it enabled individuals to take in the

different modes of sensory input. It could be that an individual’s

subconscious allowed them to experience how peaceful and quiet

nature is. Harper said:

“I’d say on a concrete level, literally the fresh air, like when I

breathe in, I think it tastes different. . . the feeling the fresh air

and seeing and I feel like there are a lot of colors are going

on with it and you get the smells of flowers and plants and its

quite sensory.”

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

5

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

TABLE 3 | Participants’ characteristics.

Pseudonyms

Age range

Gender

Marian

Polly

18–25

F

18–25

F

Liz

Anne

Harper

Nina

Aimen

40–50

F

18–25

F

18–25

F

18–25

F

18–25

F

Ethnicity

Italian/Romanian

White British

White British

Belgian

White British

Indian

Pakistani

Nature-related activities engaged with

Climbing, walking dogs, pet therapy, playing with animals

Hiking, scouts (hiking, camping, fires, learning about nature), gardening, tree planting,

walks, outdoor yoga, bug hunts, painting/art, canoeing, swimming, feeding animals,

cleaning animals

Walking in the countryside, farming/harvesting, caring for animals, swimming in the

sea, playing on the beach, surfing

Hiking, walking, running, climbing

Forest walks, playing in the park, looking for birds, animal engagement, feeding

animals

Walking, nature-based craft activities

Gardening, walking, playing with sand, farming

TABLE 4 | Topic guide for the semi-structured interview questions.

Please could you start by telling me about the nature-related activities you

liked as a child. Which of these activities do you still engage in?

What was it about these activities that you liked?

How would you say that these activities impacted your well-being or mental

health as a child? Why do you think it impacted you in this way? Does it still

affect you?

Can you describe an example of when these nature-related activities

benefited your well-being? How do you think it helped?

If you were not able to engage in these activities, how do you think it would

affect your well-being? Was there a time when you weren’t able to do them?

How did it make you feel? Why?

Do you think that any of these activities has affected you as an individual?

now? If so, could you explain to me how you think it has had this effect on

you?

Is there anything else you would like to cover that I may have missed?

Do have any question you would like to ask?

Participants described how nature allowed them to explore the

scene, and there were diverse experiences they could get from

their environment. As Harper explained, the sensory input is on

a concrete level. Therefore, the eyes, ears, nose, and hands have

to a specific degree, evidence, that their senses were fulfilled with

what they subconsciously enjoy. Participant reported the natural

sounds such as rain, leaves rustling, and the sea that had a calming

effect, and described how that this effect brought joy. Similarly,

with the other sensory inputs, they had other positive effects, for

e.g., smelling flowers and freshly cut grass, or looking at a vast

horizon was aesthetically pleasing to the eye, which in turn led to

participants’ reports of enjoyment.

The increase in positive affect and the reduction of unpleasant

affect encapsulate a facet of subjective well-being (Diener et al.,

1999), and the role of sensory input from nature in affect

regulation nature has been a key theme of earlier research (e.g.,

Ulrich, 1979; Martyn and Brymer, 2016). Indeed, the theme of

“immersion in the present moment” in a recent qualitative study

described the role of the richness of perceptual experience within

a natural environment that facilitates absorption (Brymer et al.,

2021). Moreover, the engagement with natural beauty has been

found to mediate the relationship between nature connectedness

and happiness (Richardson and McEwan, 2018). As mentioned in

the Introduction, the biophilia hypothesis explains these sensory

preferences for nature as evolutionary in origin (Wilson, 1984),

their facilitation of evolved affective systems are described in

SRT (Ulrich, 1983) and these are operationalised as goal-directed

sensory the preferences within ART (Kaplan, 1995). These

theories make the fair assumption that humans have sensory

preferences, and PCT has the grounding within engineering

and mathematics to describe the working mechanism in detail.

According to PCT, the behavior of humans and other animals

is the manifestation of controlled sensory input and this can be

modeled as a negative feedback control system (Powers, 1973).

Taken together, our participants’ expression of the enjoyment

of sensory input from nature may provide neurophysiological

balance precisely because it permits them to act, freely, to control

the input to their senses as they observe and navigate through a

natural environment.

Theme 2: Feel Freedom

This theme is about how nature-related activities made people

feel as if they were free and liberated, often because they did not

need to conform with the expectations of others. Marian said:

“You can get to be yourself because no one is judging you and

is looking at you, like animals don’t care about the way you

look or whatever you’re doing, they’re just there with you. And

you don’t have to force it.”

The participants described feeling free to roam around and

explore, and they seemed to link this to some of the other benefits

of nature. For example, Nina said:

“I would feel a lot more free and you can separate yourself from

the things that are stressing you and allows to problem solve.”

The autonomy facet of psychological well-being (Ryff and Keyes,

1995) comes closest to the feeling of freedom theme described

here, and it has emerged in other qualitative studies (e.g.,

Martyn and Brymer, 2016; McCree et al., 2018). Given the

subjective nature of this theme, it is hard to assess objectively,

yet there is a small but robust benefit in attentional control—the

ability to orient and sustain attention of one’s own volition—

measured after nature engagement (Stevenson et al., 2018). The

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

6

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

feeling of freedom is implicit within theoretical accounts of

nature engagement, such as the goal compatibility feature of

ART describes the benefits of experiences that are self-selected,

also a component of self-regulation theory (Korpela, 1995) and

self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985). PCT echoes

this self-regulatory function; the intrinsic need to control one’s

sensory experiences through freedom of action is at the heart of

PCT, guiding psychological development throughout the lifespan

(Plooij, 2020). Method of Levels, a therapy based on PCT,

provides clients with the freedom to control their own access to

therapy and the choice of problem to discuss, and the therapist

uses questioning to facilitate the client’s ability to shift and sustain

attention to various facets of the experiences they choose to

discuss (Carey, 2006; Mansell, 2018).

Theme 3: Calm Nature Facilitates a Calm

Mood

Participants explained that nature is calm in terms of sounds and

the overall atmosphere; it influenced the individual’s feelings. The

atmosphere corresponded to their emotions. The participants

described various specific examples of how experiences of nature

enabled their calm and relaxed mood. Marian said:

“It can change your mood, definitely. Like the calmness of the

trees helps you to be calm as well.”

Similarly, Nina said:

“The feeling of breeze and fresh air on your skin and the

sounds in nature are softer so trees rustling and animals and

those more gentle sounds. So they are very calming for me.

And also the feeling of grass, laying on the grass.”

In each case, there was a confluence between the gentle nature

of the experiences of nature and the calming, relaxed mood the

participants experienced.

The feeling of calmness and relaxation form a component of

subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1999). The capacity for the

aesthetic qualities of natural scenes to faciliate calm mood forms

one of the affective reactions described in SRT (Ulrich, 1983).

More recently, Richardson’s emotion regulation theory describes

a neurophysiological pathway for this effect in substantial detail,

via the balancing of the parasympathetic (PNS) and sympathetic

(SNS) nervous systems (Richardson, 2019) and it builds upon

research indicating that the majority of individuals experience

an increase in PNS and a decrease in SNS activation when

engaged with nature [reviewed by Richardson (2019)]. There is

convergent evidence that the PNS sustains a reflective mindset

that in itself is an aid to well-being via its impact on self-

reflection, perspective-taking and decision-making (Kok and

Fredrickson, 2010); this links the current theme with additional

themes extracted in the study, as discussed later. Yet, it is

important to recognize that individuals in certain circumstances

experience a perceived danger within natural environments, and

this may be experienced as undesirable (e.g., animal phobias) or

even as desirable (e.g., in outdoor risk-taking pursuits; Lupton

and Tulloch, 2002). Thus, the potential for nature engagement

to be calming may be one, albeit important, function regarding

emotion regulation (Richardson, 2019). The role of “calming”

mood within a PCT framework is described as it emerges in

later themes.

Theme 4: Enhancing Decision Making and

Forming Action Plans

This theme refers to how nature-related activities allowed

individuals to make a concrete action plan and make decisions.

The participants explained how they found it easier to make plans

when they engaged with nature relative to when they were inside.

Anne said:

“I’m working and I’m inside, all these different thoughts pop

up and I can get a bit disorganized and then when I’m outside I

think it’s much easier to organize my thoughts a little bit more

and come up with an action plan. And then really come back

inside and get back to what I need to do. . . it allows me to see

the different things that I need to do and organize them.”

Engaging with nature helped the participants to clear their mind.

It helped to stop thinking about unnecessary thoughts, that was

previously on the participant’s mind, which led to more excessive

unhelpful thinking patterns, and enabled them to contemplate on

the essential factors. For example, Liz said:

“A platform to solve problems. . . if I take myself out of a

situation and I can look at it more objectively and that’s what

nature gives to me... To overcome the panic that instilled and

with that clarity, you can start to put plans in place to work

with the challenge.”

This theme clearly reflects the pathway to well-being described

within ART and in particular the importance of “being away”

to escape from distraction, reduce urgency, and engage a more

reflective mode of thought (Kaplan, 1995). Decision-making and

action planning are mental processes that are also integral to self-

regulation (Korpela, 1995). The benefit of natural environments

for reflective processing have been identified in earlier qualitative

studies (e.g., Windhorst and Williams, 2015). Indeed recent

years have seen an emergence of studies finding improvement

in sustained attention (Pasanen T. et al., 2018) and creative

problem-solving after periods of immersion in nature (Atchley

et al., 2012; Ferraro, 2015) and there is evidence from structural

equation models that the attentional focus facilitated by the

natural environment contributes to these benefits (Pasanen T.

P. et al., 2018). Our participants did not specifically describe

creativity as a benefit of nature engagement, but they did describe

the capacity to contemplate their priorities and solve problems.

On the face of it, the social, subjective and psychological

perspectives on well-being do not describe the capacity to make

decisions and action plans as a facet of well-being. Nonetheless,

they might be expected to contribute to autonomy and personal

growth (Ryff and Keyes, 1995). PCT may complement the above

approaches by specifying in more detail the state required for

decision-making; it is a neurophysiological state that allows

allows conflicted goals to be held in awareness to explore the

potential decisions for long enough, and in sufficient detail, to

come to a solution through reorganization (Mansell, 2020).

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

7

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

Theme 5: Enhancement of Efficiency and

Productivity

Participants explained that after they engaged with nature-

related activities, they were much more productive and efficient

in their work, relative to before engaging with the activity.

Nina said:

“I am much more productive if I take out some time to go out.”

Participants described engaging with nature as a positive

distraction from working because when the individual

was working, they focused on one thing for a significant

amount of time such as an essay, thus when the individual

engaged with nature they had many different things

they could divert their attention to for example the sky,

the horizon, or an animal. This made the individual feel

revitalized, which enabled them to become productive later.

Aimen said:

“During exams you say you’re going to revise from this time

to this time, so you need a break, best thing you can do it that

break, is to go spend some time with the natural environment,

in nature, with fresh air. It freshens your mind, it gives you

more energy, it motivates you, like okay I should go back to

what I was doing.”

Participants reported that when they studied but could not

focus, and they decided to engage with nature, after the

activity, they noticed that their efficiency and productivity

levels had increased, allowing them to study more than

before they had engaged with nature. Some used it as

an effective strategy to use for a break; they can exert

some energy, feeling refreshed, as Aimen said “it freshens

your mind.”

This theme appears to represent an overarching benefit from

the enhanced decision-making and restoration provided by

nature, and maps onto aspects of subjective well-being such as the

pleasant feeling of energy and refreshment, and work satisfaction

(Diener et al., 1999). To some degree, it appeared to also feed

into the sense of environmental mastery and autonomy, facets of

psychological well-being (Ryff and Keyes, 1995), that participants

experienced. Maybe because this theme represents the tail-end

of the pathway from nature to well-being, it is not captured as

a component of nature engagement theories, but it would be

consistent as an outcome of them, especially ART (Kaplan, 1995)

and self-regulation theory (Korpela, 1995). There is emerging

evidence, building the pathway from creative problem-solving,

that dispositional nature engagement is associated with a more

innovative cognitive style, which is regarded as a benefit for

educational and commercial organizations (Leong et al., 2014).

From the perspective of PCT, “productivity” and “efficiency”

represent principles within a perceptual hierarchy. Immediately

above the level of principles are system concepts, including

concepts of the self, others, organizations and the wider world.

Thus, to the extent that an individual pursues and upholds the

principles of efficiency and productivity within their self-concept,

they will experience benefits in well-being from the properties of

nature engagement that have these effects.

Theme 6: Alleviating Pressure From

Society’s Expectations Regarding

Education

Many participants explained how nature-related activities helped

them through the difficult education system. The demands

of education appeared to be profound in the case of some

participants, but the amount of stress varied depending on the

individual. Liz said:

“I’m in the cohort of the first people to do GCSE’s. . . the

pressure on us was extraordinary. . . so that 2 years, that 14–

16 years was very stressful and I identified a walk that I would

go on. . . because of having that degree of connection, reduced

my stress. . . in a way it continues now, I think at that point

things felt like they were going very fast and in nature things

don’t go fast and they go very slow. . . . So, it was certainly that

morning walk that set me on course to maintain my mental

health during school day, it sort of gave me that reflection and

preparation time.”

The participants described how the positive effects described

within earlier themes helped to lessen the pressure of education.

When the individual stepped out of a place that was causing them

anxiety and which created a great deal of pressure, nature enabled

them not to become overwhelmed. Nina said:

“I was doing my GCSE exams, so when I was about 15, the

I would go take breaks at the weekend and go outside for a

long walk and because it was a stressful time and I felt very

confined when I was inside surrounded by work and they were

the biggest exams I had done at that stage in my life, going

outside would calm me down and I would feel a lot more free

and you can separate yourself from the things that are stressing

you and allows to problem solve.”

When the participants got the opportunity to go out, they felt as

if they could do things at their time, there was a sense of ease and

control. This contrasted with how they described the education

system, where control is taken away from students because they

are told what to so and when to do it.

This theme may have been specific to the current sample

because they were young adults reflecting on their life, which

was largely dominated by academic work. Within the domain of

employment there is emerging evidence that nature engagement

breaks reduce job stress (de Bloom et al., 2017) and there is also

evidence that nature engagement in schools leads to improved

engagement with classroom education in primary school children

(Kuo et al., 2018). The theme involved participants experiencing

a break from the pressure of societal expectations regarding

education, and the experience of a lack of control over such

requirements. This theme therefore points to the importance

of understanding multiple levels of experience—including the

system concept of society’s expectations—which an individual

can choose to conform to, or not, at any moment in time. Thus,

the facets of psychological well-being such as autonomy and

purpose in life may benefit via this pathway. The theme also

dovetails with the focus of PCT of the importance of control in

well-being, and the necessity to shift awareness to higher levels of

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

8

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

perception to achieve change through a shift in perspective. This

links the current theme to later themes of both feeling freedom

and nature putting life into perspective.

Theme 7: Formation of Community

Relations

This theme is about how individuals formed community

relationships through nature engagement activities. The activities

were a way toward a strong bond with one another. Polly said:

“Cause I’ve got a real community there it is obvious that like

it’s a supplement for my well-being so if I don’t have time

for it then it doesn’t help with the stressful situations at all. . .

scouting is just, has completely shaped my life, the skills that

you get there and the people that you meet.”

Not only were these activities a way to build relationships, but

these relationships helped to deal with stressful life events that

occurred. These types of relationships last a very long time

because there is a strong foundation of how the relationship

formed, through the mutual enjoyment of a particular activity.

Marian said:

“We were out with all the people, we didn’t spend time inside,

like playing video games or watching television, we literally

had to go outside. . . we kind of like created a team.”

Participants reported that interacting with others improved their

mood, and they helped to form tight-knit communities because

they could relate with each other through a shared interest.

This theme describes an element of social well-being,

especially the sense of connectedness and social support (Larson,

1993). It is also a facet of subjective well-being as satisfaction

with one’s social group (Diener et al., 1999), and psychological

well-being as positive relations (Ryff and Keyes, 1995). The

community relations pathway has been noted as a theme

in earlier qualitative research (O’Brien et al., 2010; Genter

et al., 2015), yet theories of nature engagement have tended

to focus on connectedness with nature itself (Bragg, 1996) and

spiritual connectedness (Ferrer, 2002), and their interrelationship

(Kamitsis and Francis, 2013). Nonetheless, there is evidence

that even a 2-week nature-based intervention can promote pro-

social orientation and connectedness to other people (Passmore

and Holder, 2017), thus potentially improving social well-being

and helping to draw upon others as a source of support. From

the perspective of PCT, communities are system concepts—the

highest level of perception in PCT—and so being part of a

community may be fundamental to well-being for many people.

Theme 8: Nature Puts Things Into

Perspective

This theme is about how nature-related activities allowed the

participants to improve their viewpoint on a negative situation

and enabled them to realize the severity of a situation and how

significant, or insignificant, it truly was. Through the change

in thought process, they felt better after engaging with nature-

related activities. Liz said:

“It’s about putting things into perspective quality it seems to

have. . . a period when myself and my other half were looking

for a house and we were spending most weekends driving

around houses, so we weren’t doing our normal leisure stuff at

the weekend and moving houses is stressful anyway and I felt

my enjoyment in it going down and my frustration in it going

up. . . let’s go to the peak district instead and using it again to get

things into perspective, get them to a manageable state. . . I’d

sort of thing well the trees don’t care; the river doesn’t care. It

would help me retain perspective, having that calm beginning

to the day.”

Engaging with nature allowed the individual to have a

connection, by appreciating how amazing nature is and how

everything is meant to be in life, and a link was made by putting

the negative situation into perspective. For some, it enabled the

individual to believe that things would fall into place, giving a

sense of hope. Marian said:

“I mean you feel like your problems are so small compared

to like how big the forest is like the view from the mountain

and everything.”

A comparison was made with nature to the problem, realizing

that it was not as significant as they previously thought. The

participants tended to treat the problem as an animate object

when comparing it to the natural environment. For example,

Marian said “your problems are so small compared to like how

big the forest is.” This comparison was then used to help the

individual understand that they could manage their hardships.

This theme appeared to illustrate how nature could help

people re-establish their purpose in life, a facet of psychological

well-being (Ryff and Keyes, 1995). The capacity for nature to

provide a beneficial higher level perspective on one’s life struggles

is a feature of a number of theories, including the spirituality

of transpersonal theory (Ferrer, 2002), the perspective of an

ecological self (Bragg, 1996), and the role of the awe experienced

through witnessing natural environments as described within

ART (Kaplan, 1995). This pathway was elucidated by a recent

qualitative study of leisure engagement in nature that described

the theme of “a sense of perspective” to include a sense of

oneness with nature, and feelings of humility and gratitude in

the face of the awe of nature. The perspective provided by

nature also receives support from studies indicating that nature

connectedness mediates the benefits of nature (Kamitsis and

Francis, 2013; Trigwell et al., 2014). Interestingly, the sustained

awareness of a higher level perspective on one’s conflicting

goals at any level, is the mechanism of recovery from the

distress experienced by chronic goal conflict as described by PCT

(Powers, 1973); thus the perspective-widening capacity of nature

may be another fundamental pathway to well-being.

Theme 9: Liking the Contrast From the

Urban Environment

Participants made a clear contrast between the natural

environment and the urban environment. They reported

that the urban environment can be hectic, where an individual

needs to watch out for cars, bikes and general traffic, whereas

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

9

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

when in nature there is no need to be as cautious because such

things are not an issue. Liz said:

“Leaving behind man-made noise and entering an

environment where there is only natural noise has a

distinct neurological effect on you. It seems to calm you and

make you more alert at the same time.”

The participants reported that the natural environment brings

about a sense of peacefulness, possibly because there is not much

pressure on cognitive functioning; for example, Liz said “seems to

calm you.” Participants reported that in the urban environment,

people have to pay attention to their surroundings to look out for

danger, even for simple tasks such as changing buses in the city

center. Harper said:

“I feel like when you live in the city, when the cars zoom past it

subconsciously causes a bit of anxiety in you, whereas in nature

the calmness and stillness, like the contrast between the city

and natural environment, you feel less anxious subconsciously

because of the difference.”

The contrasting features of the urban and natural environment

are integral to the many theories of nature benefits and implicit

within qualitative studies. The reasons for this contrast relates to

the various nature engagement pathways (e.g., the contrasting

sensory input). Nonetheless, we extracted this theme because

the participants overtly stated and elaborated upon the contrast.

Indeed there is evidence within research on self-regulation

theory that people hold “place identities” for natural locations—

places where they feel an emotional bond or strong sense of

attachment (Ratcliffe and Korpela, 2018) and these may be

the natural locations that they realize meet their psychological

needs (Landon et al., 2020). Within PCT, this choice of current

surroundings would involve programs (e.g., routines, plans such

as hikes, fishing trips, forest school, etc) that are situated in the

middle of a goal hierarchy between the higher levels of principles

and system concepts, and the lower levels that control more

immediate experiences such as the choice of landscapes, plants

and animals to attend to. Controlling programs of this kind

would enable them to experience the desired qualities of natural

environment over the urban environment.

Theme 10: Coping Mechanism

Many of the participants explicitly used nature as a coping

mechanism. If they were stressed out or going through a difficult

time, they engaged in nature-related activities, which helped

them cope with their emotion. Polly said:

“I just have to go in nature to feel a bit better. So I can literally

go lie on the ground and look at the sky and even though it

won’t solve the problem, it will temporarily make me feel a bit

better, so I can go back practically deal with the situation.”

This theme drew upon the earlier themes of sensory input

as enjoyable, and nature as calming, because the process of

coping drew upon these qualities of nature-related activities. For

example, participants described how they would seek out nature

when stressed and it would help them to relax. For example,

in some cases, attention was diverted to something aesthetically

pleasing such as stars in the sky; for example, Polly said “go in

nature to feel a bit better.” Therefore, being around a pleasing

aspect of nature enabled the individual to place their attention

to something enjoyable to look at, thus resulted in positive

psychological changes in the body. Anne said:

“I get really stressed, so I’ll go outside and go for a walk for

a few minutes. . . So being able to go outside and clear my

head really helps. . . It’s both a coping mechanism and also

preventative because I know that if I don’t do it influence me.”

Nature engagement as coping is a theme within earlier studies

(e.g., Chawla, 2020). Coping has some overlap with the facets

of psychological well-being such as autonomy and the concept

of environmental mastery (Ryff and Keyes, 1995). It is also a

key process within self-regulatory theories of nature engagement

(Korpela, 1995), and “coping” as a construct may link together

the fields of ART, emotion regulation and self-regulation, in that

the choice to engage with nature to cope with stress may enable

restore the balance of the PNS and SNS systems, and through

its impact on attentional processes, also restore concentration

(Berto, 2014). PCT may be able to integrate the themes described

earlier to specify a specific pathway for long-term coping–the

reduction of chronic unresolved goal conflict (Powers, 1973). It

pinpoints the reason for a misbalance in physiological systems

as chronic suppression of “action-ready” bodily systems that

are thwarted by conflicting goals (Mansell, 2020). Therefore,

long-term coping emerges when people can select the kinds of

environments that allow them to engage with and reflect upon

their goal conflicts and resolve them through reorganization.

Reduction in arousal and improvement in concentration then

may emerge as the conflict is reduced. It is possible that this

property of natural environments leads them to be considered

by some as a “mental and emotional sanctuary” (Brymer et al.,

2021).

Theme 11: Anxious if Prevented or

Restricted

Participants explained how if the participants were prevented

from engaging in nature-related activities, they would become

anxious. Liz said:

“I’d notice anxiety going up, yeah. And it could creep up on

you, if you spend a couple of months and for some reason

you’ve not managed to do it and haven’t managed to get out

of town, I just find myself more worried about everything.”

The participants were aware that because their nature

engagement activities were used as a stress release, when

their means to release stress was taken away, anxiety increased.

Harper said:

“I feel like I would get antsy. . . I would be more stressed out

and like anxious and I just wouldn’t be enjoying it.”

It is a logical conclusion that anxiety and stress may resurface

when access to nature is limited, given its benefits for stress

reduction. Nonetheless, the participants’ were particularly aware

of this dependence on nature in their accounts and its effect on

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

10

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

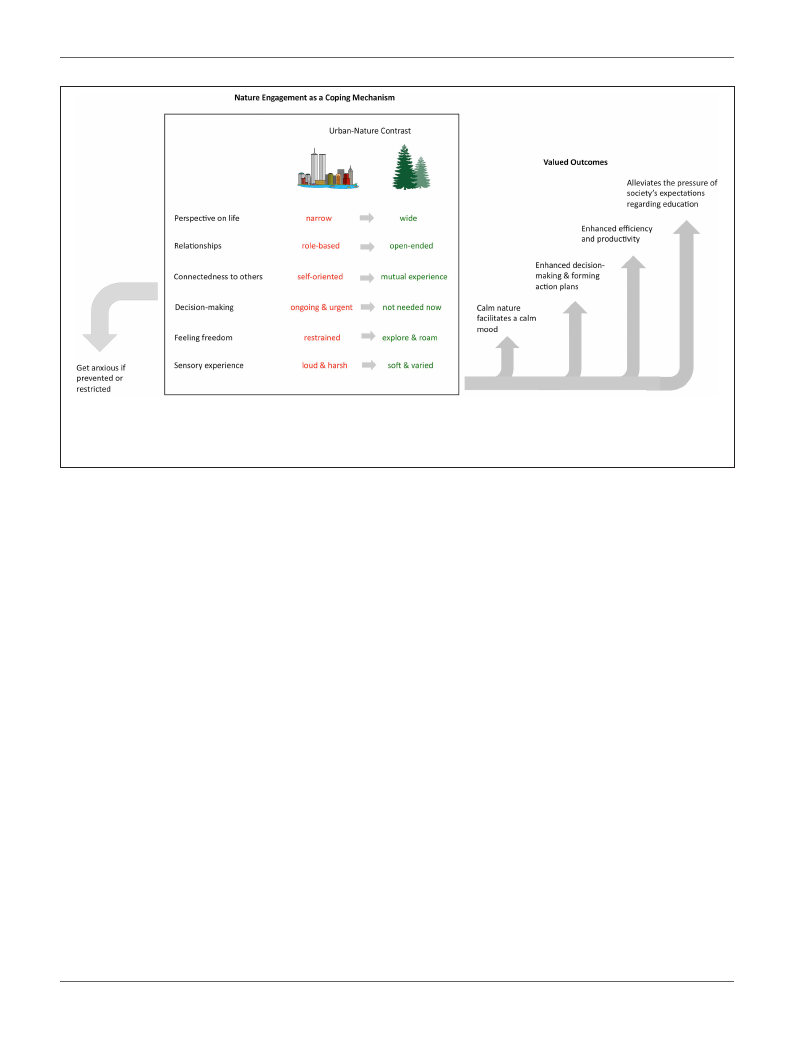

FIGURE 2 | A diagram of the themes in the study, organized to illustrate the multi-level pathways through which nature engagement as a coping mechanism leads to

multi-level benefits to well-being. The themes outside the box are worded as in the Results and Discussion. However, within the box, the rest of the themes have been

organized hierarchically, and the Urban vs. Nature theme has been used to contrast each of these perceptions between the two environments using material from

participants’ accounts.

their subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1999). Their experience

could be interpreted as a validation of the view that access to

nature is a basic need owing to our biological heritage (Wilson,

1984). Alternatively, it could be claimed that using a “dose”

of nature to “cope” is insufficient, in a similar way to the

resurgence of anxiety during withdrawal from medication for

emotional disorders. A potential integrative stance is that nature

engagement has a unique and intrinsic capacity to combine

multiple pathways to well-being, yet it is not always sufficient

in facilitating benefits that sustain. Future research could explore

whether certain forms of nature engagement, possibly those that

facilitate higher-level perspectives on conflicting aspects of the

self, as described in PCT, have long-term benefits.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The combination of themes in the current study is novel, and

also somewhat comprehensive, seeming to encompass many of

the themes from earlier qualitative studies, many of which also

have an empirical basis within quantitative research. Therefore,

we attempt to fully integrate them here (see Figure 2).

The bottom line inside the box in Figure 2 describes the lower

levels of perceptual experiences within the natural environment.

These levels of perception would include intensities, sensations,

configurations and transitions within the PCT hierarchy. The

specific aesthetic qualities of these perceptions within the natural

environment and how they facilitate adaptive neurophysiological

modes of action are well-described by SRT, ART and Emotion

Regulation Theory. Key examples of their beneficial pathways

emerging from the analysis are a calm mood (a valued outcome

in Figure 2), and a free exploration of experience (going up a

level in Figure 2), which in turn enables creative problem-solving

(a further valued outcome in Figure 2) which in turn leads

to further valued outcomes including improved efficiency and

productivity (Figure 2). Interestingly, the perceptual hierarchy

in PCT can short-circuit the exterm environment and enter an

imagination mode whereby stored perceptions are experienced

“as if ” real to the brain (Powers, 1973). This capacity has been

used to explain the role of imagery in psychological interventions

(e.g., Mansell and Hodson, 2009), and there is evidence that

mental imagery of natural scenes may be particularly beneficial,

for example in reducing state anxiety (Nguyen and Brymer,

2018).

As well as providing a hierarchical framework, PCT describes

the nature of a “problem” and how it is solved. A person is primed

to act on a goal, entailing physiological arousal, yet becomes stuck

with these feelings, which are now experienced as stress owing

to thwarted goal progress, and this requires a creative solution

(Mansell, 2020). PCT proposes that the solution will emerge if

attention is directed and sustained above the systems in conflict

until the process of reorganization allows spontaneous, trial-and-

error changes that resolve it. It is notable therefore that there

are higher levels of perception in Figure 2—connection with a

community and a wider view on one’s life from the perspective

of one’s connection with the natural world. In order to resolve

issues relating to one’s own conflicting standards or social roles,

PCT would indicate that a person needs to shift and sustain their

awareness above these levels to eventually resolve them, and one

of these resolutions includes alleviation from the pressures of the

education system (the final valued outcome in Figure 2). The

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

11

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

additional themes in Figure 2 are outside the box because they

indicate that, owing to the above benefits, natural environments

themselves are a controlled perception, to be used as a coping

strategy (a “program” in PCT terms), and anxiety is experienced

when this control of environment is restricted or not possible.

Importantly, this model is analytical rather than formal, and

the aim of future research will be to formalize these components

within a PCT architecture and construct individualized models

that can be tested for their fit with real world data within

natural environments. This methodology is challenging, but it

provides a particularly robust test of a psychological theory

(Mansell and Huddy, 2020). The functional specification of a

model will also facilitate the research and translational impact

within new technology, such as smartphones and augmented or

virtual reality, which is a burgeoning area in nature engagement

research (Wooller et al., 2018; MacIntyre et al., 2020; Yin

et al., 2020). Arguably, the closest conceptualization to date

to encompass the multi-layered benefits of nature engagement

is the phenomenological-psychoanalytic, ecological-existential

framework of Brymer and colleagues (e.g., Immonen et al., 2018;

Schweitzer et al., 2018). One clear distinction is that perceptual

control theory provides a single theoretical framework, in

contrast to a pluralistic integration of multiple theories.

There were a number of limitations of this study. First,

although the sample were of the desired age range and

showed some ethnic diversity, only university-educated female

participants were recruited. Therefore, different themes may have

emerged with a larger sample of a wider range of education and

a representative balance of genders. Second, the semi-structured

interview format was retrospective. This was an advantage in that

the research captured a historic overview of the most personally

meaningful aspects of nature. However, it relied on memory and

focused on general themes rather than idiosyncratic, dynamic

experiences. In future, using distributed ethnographic models

with participants self-coding would increase the granularity of

the findings and provide mode detail on the context of the

findings for future research.

Overall, this study has replicated and extended the themes

from earlier qualitative studies exploring the pathways of benefit

from nature engagement. These themes have been parsed into a

multiple levels and analyzed in the context of constructs of well-

being, a range of theories of nature engagement benefits, and

perceptual control theory to generate an integrative account to

guide future research and practice.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be

made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The studies involving human participants were reviewed

and approved by UREC, University of Manchester. The

patients/participants provided their written informed consent to

participate in this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

WM conceived of the study and co-designed it. AI ran

the study and the data analysis. Both authors wrote

the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Allan, J., Hardwell, A., Kay, C., Peacock, S., Hart, M., Dillon, M., et al. (2020).

Health and wellbeing in an outdoor and adventure sports context. Sports 8:50.

doi: 10.3390/sports8040050

Alsawy, S., Mansell, W., Carey, T. A., McEvoy, P., and Tai, S. J. (2014). Science and

practice of transdiagnostic CBT: a perceptual control theory (PCT) approach.

Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 7, 334–359. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2014.7.4.334

Araújo, D., Brymer, E., Brito, H., Withagen, R., and Davids, K. (2019).

The empowering variability of affordances of nature: why do exercisers

feel better after performing the same exercise in natural environments

than in indoor environments? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 42, 138–145.

doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.020

Atchley, R. A., Strayer, D. L., and Atchley, P. (2012). Creativity in the wild:

Improving creative reasoning through immersion in natural settings. PLoS

ONE 7:e51474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051474

Barton, J., and Pretty, J. (2010). What is the best dose of nature and green exercise

for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44,

3947–3955. doi: 10.1021/es903183r

Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological

stress: a literature review on restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 4, 394–409.

doi: 10.3390/bs4040394

Birch, J., Rishbeth, C., and Payne, S. R. (2020). Nature doesn’t judge you–how

urban nature supports young people’s mental health and wellbeing in a diverse

UK city. Health Place 62:102296. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102296

Bragg, E. A. (1996). Towards ecological self: deep ecology meets constructionist

self-theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 16, 93–108. doi: 10.1006/jevp.1996.0008

Bragg, R., and Atkins, G. (2016). A Review of Nature-Based Interventions for Mental

Health Care. Natural England Commissioned Reports.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res.

Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research a Practical Guide

for Beginners. London: SAGE.

Brymer, E., Araújo, D., Davids, K., and Pepping, G.-J. (2020). Conceptualizing

the human health outcomes of acting in natural environments: an ecological

perspective. Front. Psychol. 11:1362. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01362

Brymer, E., Crabtree, J., and King, R. (2021). Exploring perceptions of how nature

recreation benefits mental wellbeing: a qualitative enquiry. Ann. Leisure Res.

doi: 10.1080/11745398.2020.1778494

Carey, T. A. (2006). The Method of Levels: How to do Psychotherapy Without Getting

in the Way. Hayward, CA: Living Control Systems Publishing.

Carey, T. A., Mansell, W., and Tai, S. J. (2014). A biopsychosocial model

based on negative feedback and control. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:94.

doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00094

Case, C. (2005). Imagining Animals: Art, Psychotherapy and Primitive States of

Mind. London; New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Chawla, L. (2020). Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: a review of

research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People

Nat. 2, 619–642. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10128

Coventry, P. A., Neale, C., Dyke, A., Pateman, R., and Cinderby, S. (2019). The

mental health benefits of purposeful activities in public green spaces in urban

and semi-urban neighbourhoods: a mixed-methods pilot and proof of concept

study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:2712. doi: 10.3390/ijerph1615

2712

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org

12

March 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 580992

Iqbal and Mansell

Nature Engagement Pathways

de Bloom, J., Sianoja, M., Korpela, K., Tuomisto, M., Lilja, A., Geurts, S., et al.

(2017). Effects of park walks and relaxation exercises during lunch breaks on

recovery from job stress: two randomized controlled trials. J. Environ. Psychol.

51, 14–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.006

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations

scale: self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 19, 109–134.

doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Diener, E., Suh, E., Lucas, R., and Smith, H. (1999). Subjective

wellbeing: three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 125, 276–302.

doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Ewert, A. W., Mitten, D. S., and Overholt, J. R. (2014). Natural Environments and

Human Health. CABI. doi: 10.1079/9781845939199.0000

Ferraro, F. M. III. (2015). Enhancement of convergent creativity

following a multiday wilderness experience. Ecopsychology 7, 7–11.

doi: 10.1089/eco.2014.0043

Ferrer, J. N. (2002). Revisioning Transpersonal Theory: A Participatory Vision of

Human Spirituality. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Genter, C., Roberts, A., Richardson, J., and Sheaff, M. (2015). The contribution

of allotment gardening to health and wellbeing: a systematic review of the

literature. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 78, 593–605. doi: 10.1177/0308022615599408

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Glasser, W. (1981). Stations of the Mind: New Directions for Reality Therapy. New

York, NY: Harper Collins.

Greenleaf, A. T., Bryant, R. M., and Pollock, J. B. (2014). Nature-Based counseling:

integrating the healing benefits of nature into practice. Int. J. Adv. Counsel. 36,

162–174. doi: 10.1007/s10447-013-9198-4

Heerwagen, J. H., and Orians, G. H. (2002). “The ecological world of children,” in

Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural and Evolutionary Perspectives,

eds P. H. Kahn. Jr, and S. R. Kellert (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 29–64.

Howell, A. J., Dopko, R. L., Passmore, H. A., and Buro, K. (2011). Nature

connectedness: associations with wellbeing and mindfulness. Pers. Individ. Dif.

51, 166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037

Immonen, T., Brymer, E., Davids, K., Liukkonen, J., and Jaakkola, T. (2018).

An ecological conceptualization of extreme sports. Front. Psychol. 9, 1274.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01274

Jordan, J. S. (2008). Wild agency: nested intentionalities in cognitive neuroscience

and archaeology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 363, 1981–1991.

doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0009

Jordan, M. (2014). Nature and Therapy: Understanding Counselling

and Psychotherapy in Outdoor Spaces. London: Routledge.

doi: 10.4324/9781315752457

Kamitsis, I., and Francis, A. J. (2013). Spirituality mediates the relationship

between engagement with nature and psychological wellbeing. J. Environ.

Psychol. 36, 136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.07.013

Kaplan, R., and Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological

Perspective. New York, NY: CUP Archive.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: toward

an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 15, 169–182.

doi: 10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Kellert, S. R., and Wilson, E. O. (1995). The Biophilia Hypothesis. Covelo, CA:

Island Press.

Kok, B. E., and Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). Upward spirals of the heart: autonomic

flexibility, as indexed by vagal tone, reciprocally and prospectively predicts

positive emotions and social connectedness. Biol. Psychol. 85, 432–436.

doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.005

Korpela, K. (1995). Developing the Environmental Self-Regulation Hypothesis.