Mental Vitality: Assessing the Impact of a

Walk in the Woods

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the

Professional Doctorate in Education at

London South Bank University

August 2015

Revised April 2016

by

Mark F. Bowen

Dissertation Committee:

Prof. Stephen Lerman

Prof. Paula Reavey

i

DEDICATION

Dedicated to the furtherment of Ecopsychology.

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Professors Lerman and Reavey for their expert and tireless

guidance in this dissertation process. Additionally, the entire team of professors at

LSBU who instructed us illuminated my path and opened up new ways of thinking

during the programme and for that I am very grateful.

Additionally, I would like to thank my focus group of students who provided feedback

and advice on my initial research proposal and helped shape my final research

project: Amilee Bishop, Julia Colleluori, Emma Imbert and Yunting Huang.

And finally, I thank my ever-so-patient partner, Gabriel English, who ended up with

many, many weekends of my household chores so that I could focus on completing

this dissertation.

iii

ABSTRACT

As pressures mount in the world, they take a toll upon our mental and physical

capacities. A foundational principle of ecopsychology is that connection with nature

positively impacts our mental and psychological health and well-being. While much

research has focused on children and adults, no research into the influence of nature

specifically targeting 16-18 year olds has been conducted. Additionally, this doctoral

dissertation addressed the calls from literature and the gaps in the knowledge base

regarding employing just one independent variable and one dependent variable in

ecopsychology nature walk research. Existing commentaries are critical of many

extant research projects which have sought to measure too many outcomes (in their

opinion) in one study. Mixed methods research was justified and employed based

upon the researcher’s philosophy and the goals of the research project. This

investigation examined the effect of nature walks on a population of 16-18 year olds -

- students at an international school, or Third Culture Kids (TCKs), defined as a child

living outside of their parents’ native culture, a further novel innovation in this area of

research. This study measured one aspect of mental vitality, that of mental acuity.

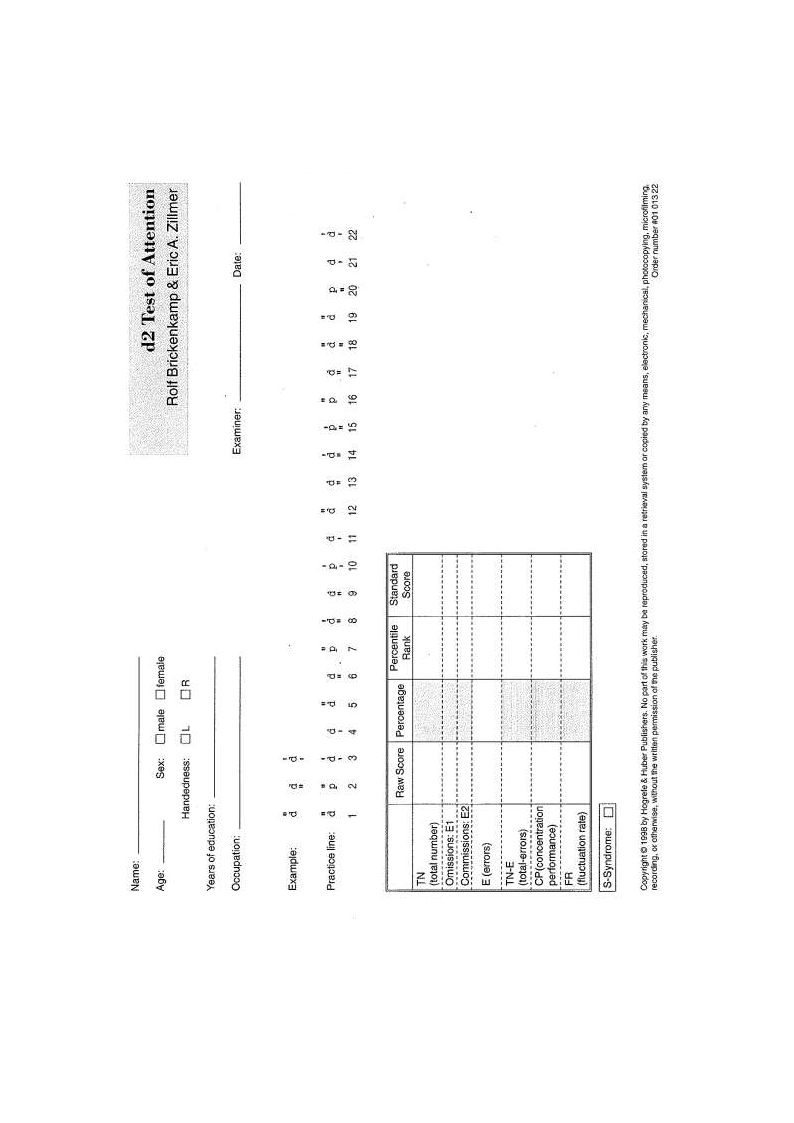

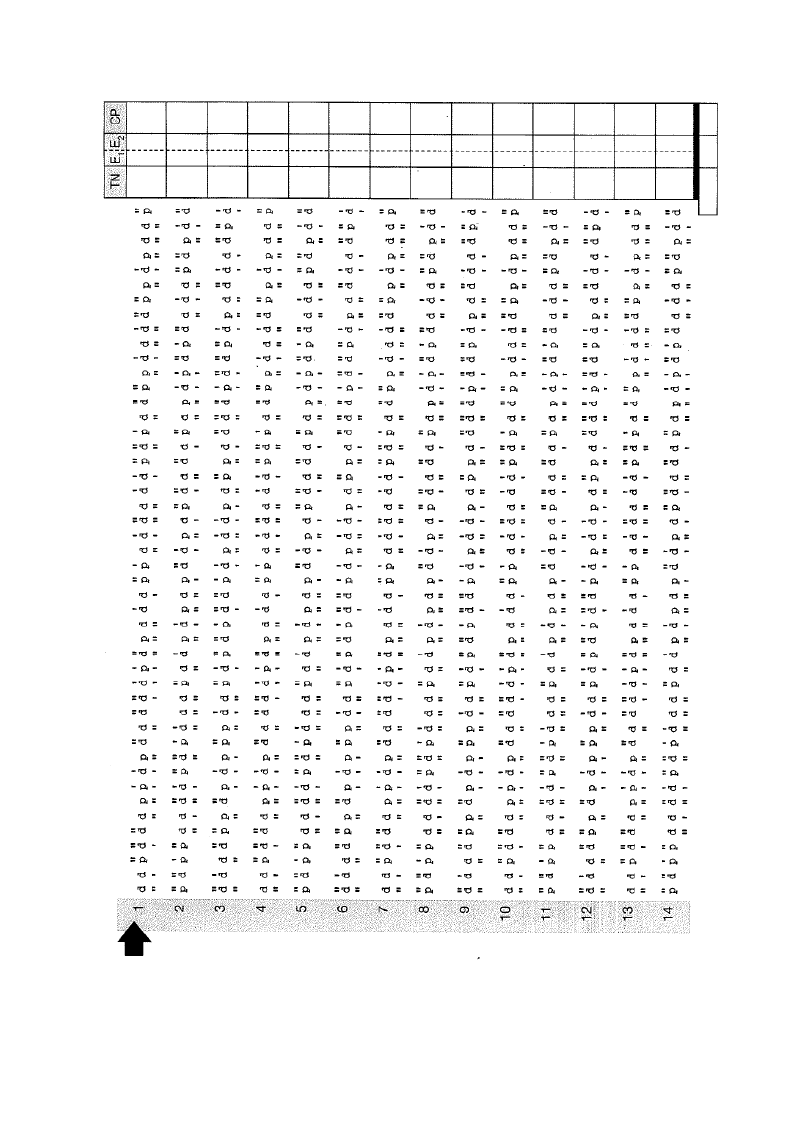

Using the d2 Test of Attention as a quantitative measure to evaluate the impact of

regular nature walks and personal reflection journals as a qualitative measure, this

study found a significant improvement in participants’ mental acuity in both the

quantitative and qualitative results after a regular, twice weekly, 40 to 60 minute

duration nature walk intervention. Implementation of nature walks into schools is

highly recommended to benefit students’ psychological health and well-being.

Recommendations for additional research are also suggested.

iv

Table of Contents

Dedication………….………………………………………………………………………...i

Acknowledgments..……………………………………………………………………...ii

Abstract……………….………………………………………………………….…………...iii

Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………..iv

Chapter 1: Introduction………………………………………………………………...1

Chapter 2: Literature Review………………………………………………………...13

Chapter 3: Methodology………………………………………………………...…....72

Chapter 4: Results………………………………………………………………………….100

Chapter 5: Discussion…………………………………………………………..…….....123

Chapter 6: Conclusion……………………………………………………………....…..131

List of References……………………………………………………………………….….135

Appendix I: Publicity Poster…………………………………………………..……….144

Appendix II: Initial Information Sheet……………………………………………..145

Appendix III: Informed Consent……………………………………………………...146

Appendix IV: Weekly Theme Handouts……………………………………..…...149

Appendix V: Debriefing Document……………………………………………..…..151

Appendix VI: d2 Answer Sheet…………………………………………………….….152

Appendix VII: d2 Instructions…………………………………………………….…...154

Appendix VIII: Word Analysis………………………………………………………....157

Appendix IX: Raw Data/Inferential Statistics…………………………..………162

Appendix X: Two Participants’ Full Journal Entries………………………….165

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

"As long as this exists," I thought, "and I may live to see it, this

sunshine, the cloudless skies, while this lasts, I cannot be unhappy."

The best remedy for those who are afraid, lonely or unhappy is to go

outside, somewhere where they can be quite alone with the heavens,

nature, and God. Because only then does one feel that all is as it

should be and that God wishes to see people happy, amidst the simple

beauty of nature. As long as this exists, and it certainly always will, I

know that then there will always be comfort for every sorrow, whatever

the circumstances may be. And I firmly believe that nature brings

solace in all troubles.

-- Anne Frank, excerpt from The Diary of a Young Girl.

So wrote Anne Frank during her ordeal before she and her family were discovered

by the Nazis. Her insight and analysis reflects the common wisdom shared by

humans regarding the positive effects nature can have on the human psyche and

well-being. As with many other subjects of “common knowledge,” until the past 40 to

50 years, these ideas were not subjected to scientific methodology. But the concept

of nature influencing not only mental, but physical, health has had a long intuitive

influence even in the absence of empirical evidence over time.

As recently as 2003, for example, a comprehensive UK government White Paper

could reliably note: “Intuition and experience seem to support the notion that nature

contact should be seen as a positive health intervention, yet health professionals

have not yet widely adopted horticulture, wilderness, nature or animal therapy….It is,

in other words, insufficiently evidence-based”. (Pretty, Griffin, Sellens & Pretty, 2003,

p. 21). The report continues with a critique of much of the published research in this

2

area as being not well designed and therefore not reliable enough to establish a

cause and effect relationship.

This present research project sought to examine the specific effect of nature walks

on the participants’ psychological health and well-being by examining cognitive

functioning using both quantitative and qualitative measures.

Historical Precedent

Restorative gardens and natural areas were key parts of infirmaries and hospitals

going back to the Middle Ages in Europe. Marcus and Barnes (1999) recount the

inclusion of these features beginning with the writings of Saint Bernard as far back

as the twelfth century CE to illustrate the origins in Western culture in places of

healing. (Marcus and Barnes, 1999). Marcus, writing alone the following year states:

“In past centuries, green nature, sunlight and fresh air were seen as essential

components of healing in settings ranging from medieval monastic infirmaries, to

19th century pavilion-style hospitals, to early 20th century asylums and sanatoria”.

(Marcus, 2000, p. 461).

As Enlightenment and scientific revolution ideals took hold and spread, the approach

to treating the mentally ill, then known as the “insane,” affected treatment protocols.

Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride, who served as Superintendent of the Pennsylvania

Hospital for the Insane from 1841 to 1883 believed that surroundings and

environment could have a complementary effect on the healing process:

Kirkbride’s principles of design for moral treatment of the insane came to be

known as the Kirkbride Plan, and influenced the design of virtually all

3

American mental institutions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries…...And he believed in beauty. In his 1854 On the Construction,

Organization and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane, he wrote,

‘The surrounding scenery should be of varied and attractive kind and the

neighborhood should possess numerous objects of an agreeable and

interesting character.’ The hospital building had to be situated so as to assure

views from every window, especially from the parlors and rooms where

patients congregated during the day. Flowers were to be grown in

greenhouses, and picked daily to decorate the halls and common areas of the

hospital. (Sternberg, 2009, p. 232).

But as the 19th century progressed into the 20th century and society became less

comfortable with the visibility of those with mental health issues, these principles

were abandoned. Mental institutions returned to the status of near prison like

conditions.

However, there has been a resurgence of these healing principles through

Ecopsychology in the 21st century which affirms that Kirkbride’s basic principles

should still be followed for maximum complementary benefits which have been found

to improve emotional outlook and mood. It is noted that these design features should

be included in all health care facilities be it for mental or physical health. More and

more research is acknowledging that simply attending to the physical parts of healing

is not enough but that there is a psychological component to any injury which the

body receives, which has long been unacknowledged or ignored (Sternberg, 2009).

4

And in the treatment of purely medical (as opposed to mental) conditions, there was

a parallel development in hospitals, with a prominent advocate like Florence

Nightingale.

After the war, she was a major proponent of British architect Henry Currey (the

designer of St. Thomas Hospital in 1868). It was based upon the pavilion principle

which originated with French architect Bernard Poyet, drawing upon the natural

sunlight, ventilation and airiness even in the absence of other natural elements due

to its location in urban London. In Poyet’s designs he incorporated large bays of

windows with long hallways to facilitate airflow, placed the sanitary facilities well

away from the patients, and located each bed near a window bay (Sternberg, 2009).

Nightingale’s ideas and concepts crossed the Atlantic and were incorporated into the

design of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Canada in 1893. Features were incorporated

such as twelve foot ceilings and large windows to allow sunlight and air into the

public wing and maternity wards, while affording views of the hillsides and woods

with the express intent of allowing patients to view nature. The nearby Children’s

Hospital included allowing the children outdoor time within their limitations which was

seen as crucial for their healing (Sternberg, 2009).

The relationship between stress reduction and viewing nature scenes was

demonstrated empirically shortly after Ulrich’s ground-breaking 1984 study detailing

accelerated recovery from surgery for subjects who had a nature view during

recovery. Ulrich et al. (1991) designed an experiment to artificially stress participants

through the viewing of a video and then viewing one of six “recovery” videos -- two of

nature scenes and four urban. 120 undergraduate volunteers (60 male/60 female)

5

participated and had 4 physiological measures taken immediately before and

throughout the viewing of the videos. These were Electrocardiogram (EKG), pulse

transit time (PTT), spontaneous skin conductance responding (SCR), and frontalis

muscle tension (EMG). “The results strongly support the conclusion that recuperation

was faster and more complete when subjects were exposed to natural settings rather

than the various urban environments”. (p. 222).

And right up to the current day, the importance of the environment in helping to

reduce stress to improve healing can be seen in Maggie’s Centres throughout the

UK and around the world. Charles Jencks, along with his late wife Maggie Keswick

Jencks, formed the charity to encourage complementary therapeutic treatments

incorporating features championed by the renowned architect Frank Gehry. “The

architect Charles Jencks, when interviewed in a PBS television documentary

directed by Sydney Pollack, said that Gehry ‘is committed to a notion of an

architecture that relates to healing.’ Jencks should know. Gehry designed a tranquil,

restorative refuge in memory of Jencks’ wife, Maggie Keswick, who died of cancer.

This small, whimsical, modernist building, reminiscent of a thatched-roof cottage, is

set in the rolling countryside near Dundee, Scotland, and is one of a series of

Maggie’s Centres designed by master architects. It is filled with places for reflection,

and provides views of the peaceful hills all around”. (Sternberg, 2009, p. 166).

Early Psychologists’ Views on Nature

“You must go in quest of yourself, and you will find yourself again only

in the simple and forgotten things. Why not go into the forest for a time,

literally? Sometimes a tree tells you more than can be read in books.”

The Earth Has a Soul: C. G. Jung on Nature, Technology & Modern

Life ed. by Sabini

6

After psychology had become a separate discipline from philosophy in the latter part

of the 19th century, two influential popular figures were Sigmund Freud and Carl

Jung. Their theoretical formulations are considered less scientific nowadays than

later psychologists as many of their concepts were built upon anecdotal data, but the

quote above emerges from Jung’s experience with Analytical Psychology. And, while

still anecdotal, is an opinion moving closer from simply “common knowledge” to that

of an experienced psychologist. Jung believed in an intimate inter-relationship

between each human being and the world around them. His admonition recognizes

the same common wisdom humans seem to instinctively know: that contact with

nature can make us “feel better.” This innate feeling is many times at direct odds

with our current age, however, as the number of people dwelling in cities and having

little contact with nature is at a record level, replaced by increasing contact with

virtual reality and technology (Pergams and Zaradic, 2008).

Consequently, humankind is facing increasing physical and psychological challenges

from the accelerating pace of modern life -- from the overwhelming quantities of

information inundating individuals during 24 hours of each day, to the constant

sensory stimuli from a variety of media, including mp3 players, televisions, mobile

phones, and the Internet. Meanwhile, social pressure within the workplace to

increase effort contributes to additional mental fatigue. The cumulative effect of

these has been observed to take a toll on an individual’s physical health,

concentration, alertness and focus (American Psychological Association, 2013;

Bratman, Hamilton and Daily, 2012; Buzell and Chalquist, 2015; Kaplan and Kaplan

1989; Tennessen and Cimprich 1995; van den Berg, Hartig & Staats, 2007).

While there are various approaches and strategies to address these issues,

7

ecopsychology is the specialization within psychology in which the disconnection of

the individual/patient from nature is seen to contribute to her/his problem; the

counterbalance indicates that the reconnection of the individual with nature is part of

the solution (Roszak, 1992). Ecopsychology is influenced by biophilia which is

defined as “...a human dependence on nature that extends far beyond the simple

issues of material and physical sustenance to encompass as well the human craving

for aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive, and even spiritual meaning and satisfaction”

(Kellert and Wilson, 1993, p. 20) and leads to healthiness and wellness, but

conversely, can lead to various forms of dysfunction -- if there is a disconnect from

nature.

Many subdisciplines of psychology also recognize a nature-psyche connection, even

if their main focus is not ecopsychology. Gardner (2006) in his Multiple Intelligences

theory proposes a naturalistic intelligence which suggests a human cognitive

connection to nature. Psychodynamic theorists also note a strong connection

between nature and psychological health (Jordan 2009). Maslow, a key humanistic

theorist, includes place-based elements in the two basic levels of needs:

physiological and safety. Elements in both of these include the need for physical

shelter and the ability to feel safe and secure (or attached) to the place in order to be

psychologically healthy (Maslow, 1943). Louv (2005) focused on the lack of

connection to nature with a number of psychological conditions among children, and

similar to Roszak, proposes that at least a part of the solution is helping children to

interact with nature more frequently. This disconnection from nature has been further

documented by Pergams and Zaradic (2008, p. 2295) where “...all major lines of

evidence point to an ongoing and fundamental shift away from nature-based

recreation.” And disturbingly, the shift appears to be because of videophilia -- defined

8

as overly attached to televisions and tablets -- placing further distance between

humans and nature. Orr (2004) reflects on the importance for each of us to connect

with nature, “I do not know whether it is possible to love the planet or not, but I do

know that it is possible to love the places we can see, touch, smell, and experience”.

(ebook Loc. 1786).

Contemporary Structural Obstacles

But current thought questions the ability of humankind to solve the environmental

problems facing the world today due to both a willful disregard of the underlying

causes as well as the basic economic structure of the world. Commenting on the

plethora of environmental problems constantly surrounding us, Orr (2004) reflects:

“These facts only appear to be random. In truth, they are not random at all but part of

a larger pattern that includes shopping malls and deforestation, glitzy suburbs and

ozone holes, crowded freeways and climate change, overstocked supermarkets and

soil erosion, a gross national product in excess of $5 trillion and superfund sites, and

technological wonders and insensate violence. In reality there is no such thing as a

“side effect” or an “externality.” These things are threads of a whole cloth. The fact

that we see them as disconnected events or fail to see them at all is, I believe,

evidence of a considerable failure that we have yet to acknowledge as an

educational failure. It is a failure to educate people to think broadly, to perceive

systems and patterns, and to live as a whole person”. (p. 91).

Orr, 2004, continues in his introduction to dissect this continued duality of thought

where humankind acknowledges grave environmental issues while continuing to

engage in destructive behaviours in this introduction to a collection of essays

regarding the interaction of the mind and nature:

9

They are joined by the belief that the environmental crisis originates with the

inability to think about ecological patterns, systems of causation, and the long-

term effects of human actions. Eventually these are manifested as soil

erosion, species extinction, deforestation, ugliness, pollution, social decay,

injustice, and economic inefficiencies. In contrast, what can be called

ecological design intelligence (italics original) is the capacity to understand the

ecological context in which humans live, to recognize limits, and to get the

scale of things right. It is the ability to calibrate human purposes and natural

constraints and do so with grace and economy. Ecological design intelligence

is not just about things like technologies; it also has to do with the shape and

dimension of our ideas and philosophies relative to the earth. At its heart

ecological design intelligence is motivated by an ethical view of the world and

our obligations to it. On occasion it requires the good sense and moral energy

to say no to things otherwise possible and, for some, profitable. The surest

signs of ecological design intelligence are collective achievements: healthy,

durable, resilient, just and prosperous communities. (p. 104).

Koger and Winter in 2010 add further commentary to this phenomenon of denial:

“Somehow, people must split off their awareness so that they understand

environmental problems and yet forget them at the same time. Apparently, people do

not behave as intelligently and consciously as they think they do. These

considerations lead us to consider the enormous contributions of psychoanalytic

psychology, and its founder Sigmund Freud, the first and most influential

psychologist to theorize about the unconscious”. (p. 63).

10

One suggestion is that the very foundation of the Western mindset perpetuates the

misuse of the natural world and resources: “In this way, Western thinking is

dominated by a line -- of progress, of power, and of consciousness (or closeness to

God). The line is a potent basis of modernist visions. It sanctions and promotes the

idea of growth, which is good, and diminishes the value of sustainability, which is

stagnation. The line promotes resource extraction, production, consumption and

waste to the detriment of finding ways to reuse waste as food for the next

cycle….Here our point is that people in industrialized societies are deeply wedded to

the hope of progress, improvement, growth, ascendance, and enhancement”. (Koger

and Winter, 2010, p. 56). With a defining philosophy such as this, then, the very

foundation of the definition of success in Western society would exclude the concept

of something being “merely” sustainable, and in fact, make sustainability

undesirable.

This theme -- the suggested incompatibility of acting to prevent further climate

change with capitalism -- has been picked up and analysed fully in a book-length

examination by Naomi Klein (2014) This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The

Climate. In this detailed analysis, Klein points out the fundamental incompatibility

between capitalism and ecologically sensible policies. She calls attention to the

disconnect between the core tenets of capitalism which include ever-expanding

markets and unlimited resources and the realities of the world. Indeed, so many

resources are very limited, while many other resources are reaching the end of their

supply or becoming so polluted as to be unusable. Climate change is wreaking

havoc on areas of the world and presently the state of California in America is

experiencing its worst drought in history, highlighting the devastating effects that

11

continuing to follow market principles has on the environment. She can confidently

conclude: “Right now, the triumph of market logic, with its ethos of domination and

fierce competition is paralyzing almost all serious efforts to respond to climate

change”. (p. 23).

Given these challenges, is there evidence to support the concept of nature contact

being beneficial to human psychological health and well-being?

Study Development

This modest research project has attempted to study the intersection of nature and

its various restorative influences upon the human psyche. There is much intuitive

knowledge that informs humankind’s opinions regarding the beneficial effects of

nature-related experiences on human health and well-being, but gaps exist in the

literature to support this intuitive understanding with empirically-based evidence. The

effect on mental functioning of direct contact with nature in the form of nature walks

is what the present project undertook to examine. Responding to calls in the

literature for narrowly focused research projects, only one independent variable and

one dependent variable were studied -- the nature walk and a measure of mental

functioning, respectively.

The target population group for this study has been 16-18 year old students. This

has been an overlooked population in previous research studies which have tended

to either focus on children up to about age 16 or university age and higher adults.

Further, a subset of this group, students at an international school, were examined.

This is because while developmentally all 16-18 year olds are defining themselves

and making connections, students at an international school may in fact feel less

12

connection to the world around them because of their peripatetic lifestyle situations.

Contact with nature could also enhance their grounding and identity as they

continued to grow and develop, in addition to the psychologically restorative effects

on cognitive functioning.

Therefore, the research questions to be examined are:

To what extent do nature walks have a positive impact upon psychological

health specifically cognitive attention?

How do participants describe the nature walk experience?

Organization of Dissertation

There are six chapters to this dissertation. Chapter 1 contains the research question

and sets the topic in context. Chapter 2 discusses relevant background research and

related-field research. Chapter 3 presents theoretical and practical methodology

principles. Results are detailed in Chapter 4, while Chapter 5 interprets the results

and Chapter 6 discusses practical implications and recommendations for further

research.

13

Chapter 2

Literature Review

In this chapter, I will examine the literature relevant to the background of the current

study. I will also provide working definitions for the concepts being explored. The

topic of the impact of nature upon psychological health and well-being is by definition

cross-disciplinary and so correlates and precursors from a wide variety of fields will

be examined. This chapter will be subdivided into General Background and Topic

Specific Research sections.

Following this review, the limitations from prior studies will be identified as well as the

knowledge gaps which emerged and will be presented along with the research

question and hypothesis. Finally, key terms will be identified and defined.

General Background Studies and Antecedents

Philosophical Foundations: Evolutionary Psychology and/Biophilia

Many practicing ecopsychologists feel that Ecopsychology itself draws inspiration

from another subfield of psychology, that of Evolutionary psychology. Sampson, in a

chapter written in 2012, makes explicit this connection and proposes the Topophilia

Hypothesis which he defines as humans’ innate desire to bond with a local place

including both living and nonliving elements. Evolutionary psychology examines

characteristics of the human psyche through the lens of humankind’s evolutionary

development. By examining contemporary human experiences and comparing that

with a variety of historical sources including both anthropological and archaeological

14

evidence, logical conclusions can be drawn as to how and why humans behave

currently, and in the past, and the evolutionary path that connect the two.

One hypothesis arising from evolutionary psychology is the Biophilia hypothesis.

Biophilia entered into the lexicon of psychology with Erich Fromm. For Fromm, it was

a more general term: “Biophilia means, of course, love of life. For Fromm, biophilia is

the essence of humanitarian ethics, which is the central theme of every one of his

books”. (Eckardt, 1992, p. 233).

Edward O. Wilson, explaining his expanded concept of biophilia in his 1984 book

Biophilia, defines it as “the innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike

processes….We learn to distinguish life from the inanimate and move toward it like

moths to a porch light…...to explore and affiliate with life is a deep and complicated

process in mental development.” (Wilson, 1984, p. 1-2). He thus locates the

propensity of human beings to affiliate with nature and nature-like settings with our

evolutionary history.

In a follow up volume edited by Kellert entitled the Biophilia Hypothesis, the

explanation was expanded to note that the innate dependence on nature evolved in

our species and manifests itself in every level of human functioning: affective,

cognitive, spiritual, and physical, and therefore should affect our species desire to

preserve and conserve the natural environment. (Kellert, 1995).

Besides this innate attachment, what are the specific mechanisms that are proposed

that engender this continued appreciation and attachment to nature? One such

explanation involves a “re-balancing” of internal thoughts and feelings. In a

15

beautifully poetic passage Kellert (2003) observes: “Perceiving beauty in nature can

engender feelings of harmony, balance, and symmetry, no matter how fleeting or

even illusory these feelings may be. Certain elements of the natural world offer a

model of perfection in form. We discern unity and symmetry in the brilliance of a

colorful butterfly or crane, the flowering of a desert cactus or rose, the funneling of

breaking waves, the grandeur of snow-capped mountains, the breaching of

humpback whales, the bugling of elk at the height of their breeding impulse. Each

suggests a glimpse of perfection in a world where frailty, shortcoming, and chaos

often seem normative. These encounters may be infrequent, but they occur with

sufficient regularity to suggest an ideal of perfection in nature and life”. (p. 36).

Wilson focuses on the concept of “wonder” in humankind’s interactions with nature:

“Now to the very heart of wonder. Because species diversity was created prior to

humanity, and because we evolved within it, we have never fathomed its limits. As a

consequence, the living world is the natural domain of the most restless and

paradoxical part of the human spirit. Our sense of wonder grows exponentially: the

greater the knowledge, the deeper the mystery and the more we seek knowledge to

create new mystery. This catalytic reaction, seemingly an inborn human trait, draws

us perpetually forward in a search for new places and new life. Nature is to be

mastered, but (we hope) never completely. A quiet passion burns, not for total

control but for the sensation of constant advance”. (Wilson, 1984, p. 10).

While humankind has made vast progress in the last 10,000 years, moving from

hunter gatherer tribes, to modern day urban dwellers for the most part, our

evolutionary psychology has yet to catch up; humankind still essentially is wired to

live out among nature. Our natural environment has to have had an impression upon

16

our cognitive and emotional abilities. “This process is referred to as a gene-culture

coevolution wherein a certain genotype makes a behavioural response more likely”.

(Gullone, 2000, p. 295).

As with other concepts within evolutionary psychology, biophilia proves challenging

to be able to test empirically. By the very nature of the discipline, extant evidence

and records are consulted and conclusions drawn which do not lend themselves to

testability. However, Kahn in 1997 designed a research project directly based upon

testing the biophilia hypothesis with children. In a cross cultural study of children

conducted by Kahn in 1997 in the USA, Canada and Brazil, children were

interviewed concerning their level of awareness, knowledge and appreciation of

nature which data could then be used to conclude about biophilia. “Empirically, my

collaborative research supports the biophilia hypothesis, and fleshes it out

developmentally. Our research, for example, reveals ways in which children have an

abiding affiliation with nature, even in economically impoverished urban communities

where such affiliations seem least likely…..Thus, in line with the biophilia hypothesis,

it may be that there are aspects of nature itself, that help give rise to children’s

environmental constructions”. (Kahn, 1997, p. 54).

But multiple other branches of psychology also lend support to this intricate

relationship between nature and the human psyche. In Cognitive psychology, for

example, Howard Gardner in modifying his Multiple Intelligences theory, proposes a

naturalist intelligence. He feels that the “...the evidence for the existence of a

naturalist intelligence is surprisingly persuasive”. (Gardner, 2006, p. 18). This

17

intelligence involves the ability to “distinguish the diverse plants, animals, mountains,

or cloud configurations in their ecological niche”. (p. 19).

Psychodynamic theorists also have noted a relationship between “person and

planet” (Jordan, 2009, p. 26). Essential to this theory is a healthy and secure

development of the concept of self and others. According to this perspective, those

who do not, may experience psychological issues. In the contemporary expanding

view of “others,” attention has been directed to the inclusion of the nonhuman

environment in this description. “...(N)ature can be seen as representing a secure

base, an aspect of both our internal and external relational world that can provide

great comfort”. (p. 28).

Ecopsychology: Counterculture Movement to Mainstream Science

Ecopsychology began its re-emergence into mainstream science and psychology in

the 1990’s. One major stream of influence that contributed to Ecopsychology was

Psychoecology, a term coined by Robert Greenway in a 1963 essay he published at

Brandeis University (Schroll, no date). In the 1960’s and 1970’s, however, while

psychoecology had a scientific following, it also became a movement embraced by

the counterculture movement which therefore diluted its scientific bona fides. It was

not until 1992, though, when a graduate student of Greenway’s had begun a

discussion group about psychoecology in California that attracted the notice of

Theodore Roszak, who in turn published an essay and then a book in 1992 entitled

The Voice of the Earth, that it began its truly scientific rise. In it Roszak

communicated his view of Ecopsychology, perhaps wanting to avoid the possibility of

18

being called a “Psycho Ecologist!” The movement then began its slow scientific

resurrection. (Schroll, no date).

Ecopsychology continued to plod along until a kind of convergence of a variety of

factors. During the first decade of the 2000’s, it became apparent that the predictions

of seeming doom and gloom about the future of the environment were indeed

coming true. Al Gore toured the United States and parts of the world, raising

awareness of the reality of the environmental crisis approaching largely through his

“An Inconvenient Truth” tour. And a professional peer-reviewed journal entitled

“Ecopsychology” was founded in 2009. These events propelled the status of

ecopsychology from a little-known subdiscipline of psychology with New Age ties to

the mainstream of psychology as a full-fledged reputable part of mainstream

psychology.

Divisions still remained, however. Those who had joined the “ecopsychology

movement” and had little interest in the science side did not go away. And there

remain basic philosophical differences even among the scientists in the discipline,

but it has emerged to be the force it hoped to become to help both the environment

and people’s psychological health and well-being at the same time by raising

awareness that these two things are not at all unrelated, but rather actually intimately

interrelated to one another for the health of both (Doherty, 2009).

The intimate relationship between nature and healing was explored by Hegarty in

2010. In his article he notes that “Nature-connectedness is a core concept in

ecopsychology” (p. 64). He states that it is difficult to design research specifically to

test the hypothesis of the positive benefits of nature on psychological health because

19

of the possibility of so many confounding variables. So, he designed a “qualitative,

narrative, and ethnographic” (p. 66) study to try to overcome those issues. He

sampled the opinions of two groups regarding the participants’ nature

connectedness, disconnectedness, and connectedness and self-healing. The two

sample groups were “17 members of a European research group on ‘green care and

health’” and “26 university postgraduate counselling students ranging in age from 22-

62 years”. (p. 67). While acknowledging the inbuilt bias in the samples, he believes it

is still indicative of “the notion that connectedness to nature is a concept that is in at

least some people’s everyday experience and that they can relate it to their health”.

(p. 79). In response to the first question which all participants responded to regarding

connectedness to nature, “The positive emotional tone runs through all the

contributions to Question 1”. (p. 69). His findings regarding the second question

which dealt with nature disconnectedness and which was answered by all

participants were: “The answers to Question 2 hint at those to the final question,

showing that people found nature-contact personally meaningful and emotionally

valuable”. (p. 75). The third question asked the participants to consider the

relationship of nature and their own well-being. This was a semi-structured question

in that there was a Likert scale with room for additional comments. “Thirty-eight of

the 43 respondents ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ with the statement….’Being

connected with the natural world is a positive force for healing’”. (pp. 75-6). Question

4 was open ended to expand upon their standardized answer in question 3.

“Furthermore, their responses show that some individuals regularly seek out nature-

experiences to help their emotional or physical health, or link a nature-connected

experience to an important psychological time in their life”. (p. 79). He concludes:

“Based on the data reported here, nature-connected experiences seem to be

20

strongly emotional, and positively so. Emotions include not only relaxing and

pleasant ones but also those which are described as religious”. (p. 80). Thus this

empirical research strongly supports the biophilia hypothesis, as well as nature-

based interventions to improve psychological health and well-being as advocated by

ecopsychology.

The focused attention on the influence of environmental factors on various aspects

of human health and well-being is giving rise to new fields of study and

specializations. This includes, for example, the discipline of acoustic ecology. While

it had precursors in the 1960’s, similar to ecopsychology, it has garnered much more

attention and involvement, particularly since 2000, when its peer-reviewed journal,

The Journal of Acoustic Ecology, was launched. One of the major ways in which the

surrounding environment is mediated to human beings is through the sounds

received by each of our acoustic receptors -- or ears. And this particular discipline

examines both the positive and negative impacts that sound from the surrounding

environment, and the interpretation of sound, can have on our well-being (Wrightson,

2000).

Turning to children specifically, in 2002, the issue of the importance of the

consideration of the various influences that environment can have on children, was

examined by Isenberg and Quisenberry. They observed: “Outdoor play is

significantly different from indoor play. The outdoor environment permits noise,

movement, and greater freedom with raw materials, such as water, sand, dirt, and

construction materials.” (p. 35). While not directly addressing the specific benefits to

21

children of contact with nature, they do highlight the importance of outdoor play

which would be an underlying principle to that specific outdoor environment.

Richard Louv, in 2005, published a provocatively titled book, Last Child in the

Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. His analysis connects

many contemporary behavioral and psychological “issues” among modern children

to their disconnection from nature:

The postmodern notion that reality is only a construct—that we are what we

program—suggests limitless human possibilities; but as the young spend less

and less of their lives in natural surroundings, their senses narrow,

physiologically and psychologically, and this reduces the richness of human

experience.

Yet, at the very moment that the bond is breaking between the young and the

natural world, a growing body of research links our mental, physical, and

spiritual health directly to our association with nature—in positive ways.

Several of these studies suggest that thoughtful exposure of youngsters to

nature can even be a powerful form of therapy for attention-deficit disorders

and other maladies. As one scientist puts it, we can now assume that just as

children need good nutrition and adequate sleep, they may very well need

contact with nature. (Louv, 2005, p. 3).

From this we can see, based upon empirical data and theoretical interpretation, that

there is an intimate connection between quality of psychological health and well-

being and connection with the natural environment. Nature-deficit disorder posits that

many modern psychological “issues” are nothing more than the requisite nature

connection which our psyches long for.

Indeed, a public service guide published by the USDA Forest service in 2010 cited

further research into the importance of outdoor activities for children and

22

recommends: “Educational theory suggests that contact with nature facilitates

children’s development of cognitive, emotional, and spiritual connections to social

and biophysical environments around them”. (Wolf and Flora, 2010, p. 3).

This concept was validated in a recent Annal of the New York Academy of Sciences

issue which focused on The Year in Ecology and Conservation Biology 2012. One of

the reports reinforced this identical point: “As we move into cities and indoors at an

unprecedented rate, we are faced with a rapid disconnection from the natural world,

and this opens a suite of critical questions about repercussions for psychological

well-being”. (Bratman et al., 2012, p. 119).

A recent news story on the American National Public Radio show “All Things

Considered” covered an elementary school in the state of Vermont where a

kindergarten class spends every Monday out in the forest -- no matter the weather.

Called “Forest Monday” the teacher and the principal cite a plethora of benefits, not

the least of which are improvement in noncognitive skills such as persistence and

self-control. The classroom is a natural setting for contextualized learning and

according to the principal of the school, “When the kids come back from the woods,

they look healthy and happy” (Hanford, 2015) which is an anecdotal illustration of the

positive impact that nature can have on psychological well-being.

Emotional Benefits, Social Work, Place Attachment, and Political Science

While the previous section focused on some of the cognitive benefits involved with

nature and attention restoration, research is also being conducted into emotional

benefits of nature interactions. Building upon generations of “common knowledge”

regarding the importance of place, and in particular, nature in the role of healing and

23

healthiness, many related disciplines have contributed to, and benefit from, this

renewed attention to Ecopsychology.

Research by Marselle, Irvine and Warber from 2014 examined effects of nature

walks upon various affective measurements among a large sample (N=1516) of

mainly age 55+ individuals (88.3% of sample). They were able to support their

hypotheses that nature walk participants “reported significantly less depression,

perceived stress, and negative affect and significantly greater mental well-being and

positive affect than individuals who did not take part in the group walks”. (p. 141).

This result supports the efficacy of nature walks in helping humans with the affective

domains.

One example of an emergent discipline which has manifested in the academic field

of geography is medical geography. This is an evolving field which has become very

focused on the therapeutic value of certain places and the commonalities which they

share which seem to contribute to healing. “Symptomatic of such changes in the

discipline has been emergence of a significant body of research focused on the

relationship between place and varied therapeutic practices”. (Smyth, 2005, p. 488).

Examining the development of this discipline, Smyth recounts the history of the

discipline as beginning with examinations of places of “extraordinary” healing such

as Lourdes, Bath, etc. Throughout time, humans have associated healing properties

to basic elements such as water, fresh air, and landscapes. Indeed, one only needs

to consider the development of various institutions of healing going back to the 19th

century and beyond to see this influence. “The location of institutions of health care

has tended to reflect the ways that diseases and health are socially constructed. In

24

the nineteenth century, for example hospitals were designed to incorporate fresh air,

adequate daylight and low population densities (Gesler et al., 2004)...In essence,

philanthropists of the time sought to bring elements of rurality into the institution and

thereby, address the suspected cause of much illness, namely urban living“. (Smyth,

2005, p. 490). She concludes her article by observing that based upon emerging

research, planning spaces for therapeutic treatment can incorporate features to not

only cure disease but promote health.

One unique piece of research also ties into the concept of nature and place

attachment. As is discussed elsewhere regarding the population studied, Third

Culture Kids, these results can be highly relevant. “An element of emotional

happiness can be attributed to familiarity with place or place attachment. Processes

of attachment and emotion regulation are highly related…...The possible next step

may be to experience safety in the place, and feeling of security did indeed emerge

as a theme in the narratives reported by Morgan (2010). It may even be possible to

speak of the place as a secure base, and even nature itself as a secure

base…..People may enter into relationships with specific natural places, feel safe,

and feel soothed by being in a specific place”. (Johnsen, 2011, p. 180).

The issue of the interrelationship between the natural environment and our

psychological health and wellbeing is not confined to academia. An article in “Wired”

magazine in 2008 entitled “Clive Thompson on How the Next Victim of Climate

Change Will be our Minds” outlines the problems and challenges faced by individuals

as the natural environment around them changes. “Their environment is moving

away from them, and they miss it terribly” (Thompson, 2008). He goes on to

25

conclude that: “Ironically, we may simply be rediscovering a syndrome that we

thought was dead and buried. Back in the 1940s, the military considered

homesickness to be a serious and potentially fatal illness, because drafted soldiers

who got shipped overseas would often become savagely depressed…..Few of us

have the experience of being unmoored in the world”. (Thompson, 2008). Then in

2010, a New York Times Magazine piece further brought the matter to the general

public presenting the case for “solastalgia” which involves an involuntary break with

the surrounding natural environment due to external forces beyond the control of the

individual such as strip mining or mountaintop removal mining. The article recounted

in depth Glenn Albrecht’s pioneering work in the field and examined both supporters

and critics (Smith, 2010).

Back in academia, though, the emerging research indicates that at times it is

possible to become disconnected from one’s home “place” and nature without

leaving -- rather when the natural landscape is drastically changed or disrupted by

human interventions, such as coal mining or when it is affected by changing weather

patterns caused by human induced global warming. Albrecht, Sartore, Connor,

Higginbotham, Freeman, Kelly, Stain, Tonna and Pollard (2007) have proposed a

new condition known as solastalgia: “solastalgia is the distress that is produced by

environmental change impacting on people while they are directly connected to their

home environment”. (Albrecht et al., 2007, p. S95). They further propose that this

condition is a psychoterratic illness. “Psychoterratic illness is defined as earth-related

mental illness where people’s mental wellbeing (psyche) is threatened by the

severing of the ‘healthy’ links between themselves and their home/territory” (p. S95).

26

Research leading to this proposal came from two separate studies. In the first, 60

people in the Upper Hunter Region of New South Wales in Australia were

interviewed. This location was chosen in response to many local people in the

community reaching out to Dr. Albrecht complaining of symptoms which resembled

severe homesickness but paradoxically all of whom were still living at home. The

research team conducted key informant, community member, and group interviews.

What they found in common was that: “Their sense of place, their identity, physical

and mental health and general wellbeing were all challenged by unwelcome change”

(p. S96). Themes emerged which included: “the loss of ecosystem health and

corresponding sense of place, threats to personal health and wellbeing and a sense

of injustice and/or powerlessness”. (p. S96). This qualitative data was validated by

use of a quantitative instrument, the Environmental Distress Scale.

The Environmental Distress Scale (EDS) was validated in a separate work by

Higginbotham, Connor, Albrecht, Freeman and Agho in 2006. The purpose of the

development of the instrument was to offer a quantitative measure for the distress

associated with a changing environment -- where the subject has not changed, but

rather the ecological setting around them has. “The EDS is designed to measure

distress either from direct experience of environmental disturbance or from the

anticipation of potential disturbance…...In areas devastated by human and natural

events such as mining, drought, hurricanes, and even war, the EDS can identify that

component of people’s distress arising from solastalgia, the lived experience of

home and home environment desolation”. (Higginbotham et al., 2006, p. 253).

27

Additional empirical support for the condition of solastalgia can be found in a recently

published research article by Sangaramoorthy, Jamison, Boyle, Payne-Sturges,

Sapkota, Milton and Wilson (2016). The researchers targeted Doddridge County in

West Virginia, based upon extensive fracking which was occurring along the

Marcellus Shale (one of the largest shale formations in the USA) and the potential for

disruptions in the environment due to this development. Subjects were recruited

using various public media to invite anyone who felt that their lives had changed

since the fracking began. Thirteen subjects participated in two focus groups using

open ended standardized questions. Those who were long-term residents described

their feelings of loss and distress over the deterioration of the surrounding natural

environment. Because of the decline in property value, many could not leave and

this factor compounded their feelings of loss and stress. While the authors of this

study did not specifically use the term solastalgia (even though Albrecht is included

among their background sources) these symptoms are consonant with the condition

as proposed by Albrecht, et al. (2007).

Hasbach (2015) acknowledges solastalgia as a condition to be considered by

psychotherapists which contributes to “eco-anxiety.” Recommendations for

treatments with the consciousness of this new etiology included three points. The

first is to broaden the therapeutic focus from just intrapersonal and

interpersonal/social to include the person in environment as a possible factor in

diagnosis/treatment. This would include the second point of expanding the intake

interview to include questions about the client’s relationship with nature and the

environment. And finally, when appropriate, to assign nature-based homework for

clients or “rewilding therapy” (p. 207) as she terms it.

28

Similarly, the concepts surrounding place attachment have value for related

disciplines such as social work. A key concept underlying social work is that the

individual feels a part of a group or something greater than her/himself, and not just

limited to other human beings as discussed in a 2009 piece by Norton: “We are

disconnected when we experience detachment from nature and view it as a separate

or other, instead of something of which we are a part” (p. 140). She argues that

ecopsychology can inform and complement traditional social work: “However, just as

ecopsychology can help explain the human etiology of environmental destruction, it

can help social workers transform the notion of person-in-environment to include the

natural world in a way that promotes a broader view of human empowerment and

well-being. Connection to the natural world occurs when we are in relationship with

nature, experiencing a deep attachment to the planet. Connection also occurs when

we place ourselves in the larger ecosystem equally with other living things and do

not seek domination over the natural world”. (Norton, 2009, p. 140).

Concepts regarding place attachment and ecopsychology impact many political

discussions and decisions, but a particular political movement is based upon

organizing political divisions on ecological biosystems. This system is known as

bioregionalism. “Bioregionalism is a body of thought and related practice that has

evolved in response to the challenge of reconnecting socially-just human cultures in

a sustainable manner to the region-scale ecosystems in which they are irrevocably

embedded”. (Aberley, 1999, p. 13). This could be thought of as place attachment

translated into a political governing unit, or state, based upon biosystemic

completeness. A particularly long lived movement is the Cascadia independence

movement which one pro-independence organisation describes as: “a unique coastal

bioregion that defines the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada,

29

incorporating British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, parts of Idaho, southern Alaska

and northern California. This area is in many ways geographically, culturally,

economically and environmentally distinct from surrounding regions”. (Cascadia

Now, 2015). This is but one example of worldwide movements seeking to realign

political designations around ecological biosystems.

Ecotherapy

A related field to this research project is Ecotherapy. “Ecotherapy is an umbrella term

for a gathering of techniques and practices that lead to circles of mutual healing

between the human mind and the natural world from which it evolved”. (Chalquist,

2009, p. 64). Chalquist (2009) in a comprehensive review examined evidence of

ecotherapy practices and their efficacy. His conclusion based upon this analysis

included that disconnection from the natural world produces a variety of

psychological symptoms and that reconnection (he specifically mentions nature

walks outside as one modality) can alleviate these deficits and even contribute to a

renewed sense of purpose in life.

The current research project is focused on maintaining everyday mental health while

Ecotherapy is therapeutically assisting individuals to resolve various psychological

issues using nature and the environment, so both are related disciplines, in much the

same way that medicine and preventative medicine are related fields.

Ecotherapy as a practice long pre-dated the current text entitled Ecotherapy (Buzzell

& Chalquist, ed.) from 2009, but this volume collected writings from various

practitioners in the field. In the Foreword, David Orr traces the recognition and

attention that connecting nature and psychological health and wellness is currently

30

receiving. Research into ecotherapy, or integrating nature into treatments and

therapeutic interventions, has also seen an increase. As a recent article in the APA’s

Monitor on Psychology notes, “More psychologists are using the wilderness as a

backdrop and therapeutic tool in their work”. (DeAngelis, 2013, p. 49). In this same

article psychologist Scott Bandoroff, who uses nature and the wilderness as an

integral part of his therapeutic treatments, was interviewed and this was noted: “For

Bandoroff, there is no doubt that the combination of being in a beautiful natural

setting and working through your issues with highly trained professionals is a winning

one that more psychologists should consider exploring”. (DeAngelis, 2013, p. 52).

While it seems intuitive that nature could help with human psychological health and

restoration, these beliefs and claims have not been well documented and supported

by empirical testing.

One piece of research whose main focus was integrating physical activity into the

treatment plans for persons suffering from serious mental illness, did consider the

benefits of walking. “Although structured group programs can be effective for

persons with serious mental illness, especially walking programs, lifestyle changes

that focus on accumulation of moderate-intensity activity throughout the day may be

most appropriate”. (Richardson et al., 2005, p. 324).

In a comprehensive White Paper prepared in 2007, Mind, the UK charity formerly

known as the National Association for Mental Health, reviewed the findings to that

point of research and original articles concerning the possible benefits of

Ecotherapy. A summary of some of the key findings follows here (Mind, 2007):

31

“Research has found that there is a relationship between lack of green space in

urban areas and levels of stress (Grahn and Stigsdotter, 2003).” (p. 5)

“Terry Hartig argues that nature can restore deficits in attention arising from

overwork or over-concentration…” (p. 7)

After participating in Mind’s ecotherapy programmes, “Ninety-four percent of those

surveyed highlighted particular mental health benefits. Many respondents said that

they felt mentally healthier, more motivated and more positive. They felt the green

exercise helped to lift depression and instill feelings of calm and peacefulness. Their

overall mood, confidence levels and self-esteem all improved.” (p. 20).

Finally, the conclusion to the report suggested: “Ecotherapy is emerging as a

clinically valid treatment option for mental distress, and a core component of an

adequate public health strategy for mental health”. (p. 28).

In their follow-up report some six years later (2013), Mind in a report entitled “Feel

better outside, feel better inside” was able to observe regarding the various research

projects over the six years: “Seven out of ten people experienced significant

increases in wellbeing by the time they left the project. The type of project people got

involved in didn’t seem to make any difference, nor did their age”. (p. 21). Among

many other noticeable benefits: “With mental health problems such as anxiety and

depression increasing significantly, ecotherapy can improve physical health and

mental wellbeing. Its flexibility as an intervention means it can be used as a

wellbeing service that people can use to look after their mental wellbeing, an early

intervention to support people who may be at risk of developing a mental health

problem, or as a treatment in its own right”. (p. 39).

32

However, another piece of research into a residential wilderness therapy program

unexpectedly found no improvement in participants’ mental health and well-being.

One possible explanation for this result, however, could be that participants were

only exposed to ecotherapeutic interventions for a total of 3 hours out of possible

168 hours (seven 24 hour periods) residential (Wilson et al., 2011, p. 51).

In a comprehensive review article, Brymer, Cuddihy, and Sharma-Brymer (2010)

were able to conclude: “Exposure to non-human nature has benefits for a variety of

wellness related constructs. Theoretical perspectives suggest a range of possibilities

1) contact with nature acts as a medium for restoration, 2) contact with nature

provides an opportunity for emotional care, 3) nature provides a mirror for in-depth

reflection or 4) contact with nature provides an opportunity to rekindle an innate

union. That is, theoretical perspectives point to broad possibilities as to why being in

nature enhances wellness”. (p. 24). Recommendations for incorporation of

ecotherapy are not just confined to academia, however. There are a plethora of

recent UK government initiatives and guidance regarding the incorporation of

ecotherapy in communities for a variety of benefits. For example, the above-

referenced “Feel better outside, feel better inside: Ecotherapy for mental wellbeing,

resilience and recovery,” by Mind UK (2013), recommends: “This government

framework identified five key areas for action to promote wellbeing. Ecotherapy

works across all of these domains offering a holistic service to promote wellbeing in

the community,” (p. 10) and “A recent report by Mind and The Mental Health

Foundation, identifies three key components of an effective strategy to promote

resilience and recommends that public health teams should plan to ensure access to

33

services, such as ecotherapy, that prioritise building resilience and preventing mental

health problems”. (p. 11).

Further research specifically examined the efficacy of allotment gardening,

examining two aspects: “doing” the gardening and “being” in the natural setting

(Hawkins, Mercer, Thirlaway, and Clayton, 2013). This was conducted in Cardiff in

Wales using 14 participants who engaged in allotment gardening. A semistructured

interview was deemed the most appropriate instrument, as the subject’s individual

impressions of the gardening experience were most relevant to the research goals.

Thematic analysis was then used to identify key themes. Their findings showed that

participants described “doing” as: (a) distraction, physical activity, doing something,

Sharing: Expertise, Sharing: Produce, and achievement. Subjects identified the

following benefits of “being:” being away, being outdoors, social interaction,

community involvement, natural environment and retirement plan. Benefits which

overlapped in both categories included: escape, enjoyment, stress reduction, and

relaxation. It was clear from their results that both doing and being in the garden

helped restore their mental acuity and focus which supported Kaplan’s Attention

Restoration Theory as the explanation for the improvements. As a final thought, they

comment: “It is important to note, however, that the participants in this study may

have attributed most benefits to the gardening itself without perceiving how the

natural environment contributed to this. The effects of the natural environment may

be more subtle or unconscious and therefore should not be underestimated”. (p.

123).

The conclusion of a comprehensive review article examining the efficacy of

ecotherapeutic techniques as complementary to more traditional forms of therapy

34

noted: “Despite methodological limitations, there does appear to be a growing

evidence base demonstrating the physical, psychological and, to a lesser extent,

social benefits of viewing, and interacting with, greenspace”. (Wilson et al., 2009, p.

32).

A recent study by Passmore and Howell (2014) examined the affective wellness

aspects of simply being in nature. It consisted of 84 undergraduate students at a

Canadian university. 43 were assigned to the nature condition and 41 to a control

condition. Those in the experimental condition were given nature tasks to complete

during a two week period while the control group were given cognitive performance

tasks. They were able to conclude that “ongoing nature involvement over a 2-week

period boosted aspects of both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being” (p. 152) further

demonstrating positive benefits of interacting with nature and lending support to

ecotherapeutic interventions.

Geography/Environmental Science Research and Urban Planning

A closely allied discipline to the topic at hand is environmental psychology. In its

infancy in the 70’s the main concern of the field was focused on designing pleasing

environments that helped to foster positive human behaviours and discourage

undesirable or anti-social behaviour. As concern with environmental issues has

risen, however, the focus has shifted. As Daniel Stokols, a psychologist at the

School of Social Ecology at the University of California, Irvine, shared for a recent

Monitor on Psychology article: “While such topics are still of interest, Stokols says,

the field has shifted to reflect modern concerns, such as ecological sustainability and

public health. As we adapt our urban environments for the challenges of the 21st

35

century, psychologists have a particularly important role to play in making sure

human nature is part of the plan”. (Weir, 2013, p. 51).

As the proportion of human beings living in urban environments continues rising to

all-time highs and parallels with concerns over human-produced environmental

degradation, the question of the role of the constructed environments and their effect

upon health and well-being of the humans has become the subject of much

research.

In a comprehensive review article, van den Berg, Hartig, and Staats in 2007

analysed research relating to people’s preference for nature elements even in an

urbanized setting. In the section where they examine people’s beliefs about the

restorative power of healing, they noted that in most of the studies subjects identified

stress reduction, clearing the head, getting away from civilization and time to reflect

as the chief benefits of being in nature (as opposed to an urban environment.)

Recounting their own research, they reported their results in which subjects felt that

natural settings were more effective in bringing about psychological restoration than

urban settings. Based upon their analysis, they could conclude and recommend that

urban planning should include elements of nature and green spaces in order for

urban residents to be able experience the psychological restoration needs and de-

stress.

In a meta-analysis Professor Ian Douglas writes: “For urban people, the separation

from nature is greater than in other forms of human settlement, but need not

necessarily be so. Natural vegetation fulfils many ecosystem and human well-being

functions in urban areas. One of the more important is alleged to be improvement in

36

mental health, through recovery from, or alleviation of, mental illness and stress and

through helping to raise a feeling of well-being among people using natural areas”.

(Douglas, 2008, p. 12). He continues that his meta-analysis revealed: “There is good

scientific evidence that contact with nature in urban areas can improve mental health

and help in the restoration of psychological well-being”. (p. 20).

The interest in the importance of human nature interactions in urban environments is

not just academic, however. A recent Washington Post article concerning the High

Line in New York City demonstrates how these principles are ever expanding into

the popular consciousness: “The success and high profile of the High Line have

served to put the practice of landscape architecture, so often overshadowed by

architecture, into the limelight. The sophistication of the plant designs is undoubtedly

lost on the great majority of visitors, but the effect -- of a restless, changing,

naturalistic form evoking the original wildflowers -- is not”. (Higgins, 2014). Similar

principles are at work in the proposed Peckham Coal Line Project in London.

(Peckham Coal Line, 2016).

An exciting cross-disciplinary development is in the field of urban planning. Human

Geographer Jennie Middleton observed in a 2010 article, “In contrast to quantitative

studies of walking as a mode of transport, the diary and interview accounts have

afforded an engagement with the experiential dimensions of walking that makes

apparent a range of issues with, and beyond, the dominant focus on the built

environment in current pedestrian policy”. (p. 591). Her research calls upon

designers and planners to take into account the content of what the person

37

experiences as s/he travels from one place to another -- an element which has until

recently gone unconsidered.

She further explores the value of these cross disciplinary approaches to expand the

study of patterns of walking from merely mundane transportation concerns but also

to inquire into the motivations behind walking and other sensory experiences a

“walker” has such as appreciation (or lack thereof) for surroundings and considering

internal mental processes, thereby overtly associating urban planning with the

cognitive effects these designs can have upon the individual (Middleton, 2011). This

enlightened view opens up many possibilities for future urban planning and the

incorporation of green or nature elements in those plans as the psychological

benefits are more fully researched and documented.

TCKs -- Third Culture Kids

The extant research in ecopsychology has mainly focused on youth (under 12 years

old) and adults (19 and older), while very little work has been done with high school

age students (age 15-18). Therefore, the population chosen to examine for this

project was students between the ages of 16 and 18 who attended an international

school and are known as Third Culture Kids (TCKs) or global nomads. Third Culture

Kids is a relatively new term having originated in the 1960’s. Originally, “The term

‘Third Culture Kids’ or TCKs was coined to refer to the children who accompany their

parents into another society”. (Useem, 1993). At that time the main TCKs were

children of military families, missionaries and a few global business people. This

definition was based upon Useem’s work in cultures differing from her own over the

period of two decades that then led her to examine this phenomenon on a greater

38

scale. In the 1960’s she observed that greater and greater numbers of families were

living in cultures different from where they were born -- particularly in military and

missionary families -- and she noticed that they shared certain characteristics such

as “the styles of life created, shared, and learned by persons who are in the process

of relating their societies, or sections thereof, to each other”. (Useem, 1993). While

Useem’s work identified a number of benefits arising from the TCK experience

including a global orientation and higher participation in tertiary education, her initial

work did not uncover disconnection on the whole “...(T)he majority in this study reject

statements of alienation and isolation such as often feeling lonely, feeling adrift, and

hesitating to make commitments to others,” but she did find that “(a) number of our

respondents continue to feel rootless, alienated, and unable to make commitments

to people or places”. (Useem, 1993).

The term TCK has been further refined a number of times so that the more widely

accepted description is by Pollock and Van Reken: “An individual who, having spent

a significant part of the developmental years in a culture other than the parents’

culture, develops a sense of relationship to all of the cultures while not having full

ownership of any. Elements from each culture are incorporated into the life

experience, but the sense of belonging is in relationship to others of similar

experience”. (2003, p. 13).

Subsequent work over the past 20 years has identified a number of common

characteristics shared by most TCKs, many of which positively contribute to their

adult lives, but also a few challenges which can impede their future development and

success. It must be noted, however, that these are observational and correlational

39

studies and do offer only valuable qualitative data. Due to the longitudinal nature of

the TCKs experience, quantitative research in order to establish specific cause and

effect becomes problematic.

Among some of the positive characteristics are: “TCKs gain a wealth of insight. They

are tolerant of diversity, become skilled observers, and can serve as a model of

multicultural principle because of their expanded world view and exposure to cultural

differences”. (Gillies, 1998, p. 36).

Limberg and Lambie (2011) described four positive qualities which many TCKs

exhibit including an “expanded world view, adaptable, cross-cultural relationships

and often multilingual”. (p. 49). However, they also identified developmental

challenges for TCKs including “identity development issues and lack (of) a sense of

belonging” (p. 49) among others.

While it is clear that TCKs or global nomads develop many skills which are positive

and adaptive in an ever-globalizing world, there is much research and commentary

identifying challenges which TCKs face, chief among these, rootlessness and

restlessness. “Often those whose parents move every two years rarely consider

geography as the determining factor in what they consider home…..They may have

moved so many times, lived in so many different residences, and attended so many

different schools that they never had time to become attached to any”. (Pollock and

VanReken, 2003, p. 121-2). With regard to restlessness later in life, “Somehow the

settling down never quite happens. The present is never enough -- something

always seems lacking. An unrealistic attachment to the past, or a persistent

expectation that the next place will finally be home, can lead to this inner

40

restlessness that keeps the TCK always moving”. (Pollock and Van Reken, 2003, p.

125).

Subsequent work over the past 15 years has reinforced the existence of significant

feelings of rootlessness among the TCKs and on a larger scale than Useem initially

found. “It is difficult to draw conclusions when there is evidence of conflicting

findings. It is clear that sense of belonging is a subjective, emotional response to a

place or a community of people. There is evidence that TCKs may have a multiple

sense of belonging or no sense of belonging”. (Fail, Thompson, and Walker, 2004, p.

326).

An early study by Gillies (1998) identified particular issues which were a challenge

for TCKs. His article focused upon social and cultural norm differences that required

a transition time, but that “children in the international community are prone to

loneliness, because of changing friendships as people move in and out of their lives.

TCKs tend to avoid solving interpersonal problems, side-stepping potential conflicts

because they know the problem will ‘go away.’ After all, they will be moving soon”.

(p. 37).