1020462

ORG0010.1177/13505084211020462OrganizationVlasov et al.

research-article2021

Article

Suffering catalyzing ecopreneurship:

Critical ecopsychology of

organizations

Organization

1 – 26

© The Author(s) 2021

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals-permissions

httpDs:O//dIo: i1.o0r.g1/107.711/1737/5103505804824121010220044662

journals.sagepub.com/home/org

Maxim Vlasov

Umeå School of Business, Economics and Statistics, Sweden

Pasi Heikkurinen

University of Helsinki, Finland

University of Leeds, UK

Karl Johan Bonnedahl

Umeå School of Business, Economics and Statistics, Sweden

Abstract

The article bridges the gap between ecology and mind in organization theory by exploring the

role of psychological suffering for sustainable organizing. In particular, it shows how burn-out,

experiential deprivation, and ecological anxiety prompt ecopreneurs within the Swedish back-to-

the-land movement to become ecologically embedded. Three counter-practices illustrate how

this suffering represents an inner revolt against the exploitative structures of modern society and

growth capitalism, and a catalyst for alternative ecopreneurship. The article takes the first steps

toward critical ecopsychology of organizations, which offers an ecocentric ontology and a moral-

political framework for degrowth transition.

Keywords

Back-to-the-land, degrowth, ecological embeddedness, ecopreneurship, ecopsychology, suffering

Introduction

The way out of our collusive madness cannot [. . .] be by way of individual therapy [. . .], we cannot look

to psychiatrists to make the institutional changes that a life-sustaining biosphere requires.

(Roszak, 1992: 311)

Corresponding author:

Maxim Vlasov, Umeå School of Business, Economics and Statistics (RiseB, Research Institute for Sustainability and Ethics

in Business), Handelshögskolan, Biblioteksgränd 6, Umeå 90187, Sweden.

Email: maxim.vlasov@umu.se

2

Organization 00(0)

In critical organizational research, problems of ecology (“outer nature”) and mind (“inner nature”)

are commonly treated as separate issues. On the one hand, the anthropogenic ecological crisis,

including the loss of wildlife, the environmental overshoot, and the runaway global warming

(Ceballos et al., 2015; IPCC, 2018; Steffen et al., 2018) is acknowledged. As a result, an increasing

number of organizational studies scrutinize the dominant approaches, frameworks, practices, and

philosophies of organizing based upon an exploitative relationship with the natural environment

and economic growth (e.g. Ergene et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2018) and search for alternative, eco-

logical organizations (e.g. Beacham, 2018; Nesterova, 2020; Parker et al., 2014). On the other

hand, strong concerns about high levels of anxiety, burn-out, depression, stress and other mental

problems in the Global North are reported (Gallup, 2018; OECD, 2017; WHO [World Health

Organization], 2019). This set of problems prevails in spite of the increasing material standards of

life (Jackson, 2009), in what is also referred to as a “paradox of modern suffering” (Sørensen,

2010). Accordingly, previous research has scrutinized the precarious, rapidly changing, and “dirty”

realities of modern organizational life (Baran et al., 2016; Heikkurinen et al., 2021), related ideo-

logical and psychological processes behind neoliberalism and growth capitalism (Dashtipour and

Vidaillet, 2017; Murtola, 2012; Scharff, 2016), and the alienating aspects of modern life in general

(Ruuska, 2021).

This article aims at bridging the gap between ecology and mind in organization theory by

exploring the role of psychological suffering for sustainable organizing. In particular, it shows how

psychological suffering in modern societies can catalyze ecopreneurs to become ecologically

embedded. In addition to critical organizational research, our inquiry draws insights from the eco-

logical entrepreneurship literature (or ecopreneurship) (O’Neill and Gibbs, 2016; Phillips, 2013;

also Poldner et al., 2019). We conducted a three-year long ethnographic study of ecopreneurs

within the back-to-the-land movement in Sweden, focusing on their experiences and practices of

adopting an agrarian life and starting small-scale ecological enterprises. Our analytical approach is

based on critical ecopsychology, which we advance in the context of organizational research (see

Lertzman, 2004). One of the focal premises of ecopsychology is that human psyche (i.e. the totality

of the conscious and unconscious minds) is interwoven with and embedded in the natural environ-

ment, and consequently, the human-nature relationship influences identity, well-being and mental

health. Critical ecopsychology adds to this the psychological and cultural roots of environmental

destruction that can be traced to the growing separation of humans from the rest of the living, natu-

ral world. We draw on the works of Fisher (2013) and Roszak (1992), coupled with some ontologi-

cal ideas of Guattari (1989), to conceptualize psychological suffering as a revolt of “inner” nature,

or ecological unconscious, in relation to exploitative structures of modern societies and growth

capitalism.

By analyzing the experiences of back-to-the-land ecopreneurs through the critical ecopsycho-

logical lens, we find three counter-practices of grounding, re-sensitizing and regenerating that

embed ecopreneurs ecologically. Psychological suffering—in the form of burn-out, experiential

deprivation, and ecological anxiety—prompted the ecopreneurs to adopt a self-reliant lifestyle,

creative physical agrarian work, and regenerative farming practices. We make three main contribu-

tions to organizational research. First, we reveal psychological suffering as one antecedent for

ecological embedding in the context of modern societies (cf. Whiteman and Cooper, 2000). Second,

we advance an ecocentric ontology of ecopreneurship (Campbell, 2006; Vlasov, 2019) by uncover-

ing the emerging nexus of mind, society, and the natural environment where the ecopreneur is

moved into action by the ecologically grounded experience of suffering. Third, we provide new

empirical insights into the messy realities of alternative ecopreneurs (O’Neill and Gibbs, 2016;

Phillips, 2013), including an analysis of tensions that they encounter while navigating between the

mainstream economy and the land. The three contributions constitute the first steps towards critical

Vlasov et al.

3

ecopsychology of organizations, which apart from an ecocentric ontology offers a moral-political

framework for degrowth transition.

Literature review

Ecopreneurship, ecological embedding, and degrowth

In recent years, ecological entrepreneurship or ecopreneurship (Hultman et al., 2016; Phillips,

2013), as well as environmental, green, sustainable and biosphere entrepreneurship (see e.g.

Frederick, 2018; O’Neill and Gibbs, 2016; Schaefer et al., 2015), has surfaced as a transition

agency (Gibbs, 2006; Hultman et al., 2016). Ecopreneurship is broadly defined as starting a busi-

ness based on environmental values (Kirkwood and Walton, 2010). Ecopreneurs bridge what is

considered to be conflicting worlds of the natural environment and the enterprise (Kirkwood et al.,

2017; Linnanen, 2002), with an intent to “radically” transform industries, economies, and com-

munities (Isaak, 2002: 81). As result, they are expected to play an important role in the transitions

of energy provision, mobility, food, housing, communication, water, and finance (see Kanger and

Schot, 2019).

The extant ecopreneurship research has not addressed the separation of ecology and mind in

organization theory. This is problematic because the mind-nature dualism (and related binaries

such as nature-culture, mind-body) underlie the anthropocentric organizational paradigm with

its “dis-embodied form of technological knowing conjoined with an egocentric organizational

orientation” (Purser et al., 1995: 1053). For ecopreneurship, this dualism is reflected in the eco-

nomic theory where ecopreneurs address sustainability challenges by pursuing profitable oppor-

tunities in the market (e.g., Dean and McMullen, 2007). This theory has been criticized for being

reductionist in assuming an independent and rational ecopreneur (Fors and Lennefors, 2019),

whose access to nature is mediated through markets (Stål and Bonnedahl, 2016). The mind-

nature dualism may justify the moral right of ecopreneurs to continue to control, dominate and

exploit nature for economic utility. The separation of mind from nature also takes form in “place-

lessness that accompanies the increasingly “flat” and globalized world” (Shrivastava and

Kennelly, 2013: 87). Fast-paced and abstract rhythms of globalized markets, lengthy supply

chains, returns on investment, and technological trends separate most downstream ecopreneurs

close to the end-consumer from the matter-energetic source of their produce, the environment

(Muñoz and Cohen, 2017).

The mind-nature dualism in ecopreneurship research has resulted in the lack of an explicit cri-

tique of the unbridled economic growth (O’Neil and Gibbs, 2016; Schaefer et al., 2015). This is

part of the larger problem where most organizational responses to the Anthropocene have worked

to either sustain business-as-usual or reform it by means of greener technology and markets (Ergene

et al., 2020; Hopwood et al., 2005; Wright et al., 2018). The mainstream organizational scholarship

seldom perceives a conflict between economic progress and preservation of the environment

(Bonnedahl and Eriksson, 2007). Likewise, ecopreneurship often reproduces the prevailing techno-

rational and (necro)capitalist discourses of sustainable development (Banerjee, 2003; Gayá and

Phillips, 2016; O’Neil and Gibbs, 2016; Stål and Bonnedahl, 2016; Wright et al., 2018). Further

critique posits that entrepreneurship is a harbinger of the firmly entrenched assumptions of profit

maximization and wealth creation (Essers et al., 2017: 2), the Western paradigm of development

(Imas et al., 2012; Tedmanson et al., 2012), and ethno-centric, gender-biased stereotypes of extraor-

dinary, innovative, risk-taking individuals (Berglund and Johansson, 2007; Berglund and Wigren,

2012; Ogbor, 2000; Welter et al., 2017). As a result, the ideal ecopreneur is imagined as a hero, or

a savior (Houtbeckers, 2016; Johnsen et al., 2017) who feeds into the optimistic vision of the future

4

Organization 00(0)

where the ecological crisis is averted with eco-efficiency, technological fixes, market mechanisms,

and “the business case of sustainability” (Wright et al., 2018). That is, business organizations are

reassured to avert the ecological disaster within the modern paradigm, dismissing the need for any

transformative change (Gayá and Phillips, 2016).

Critical organizational scholars, however, scrutinize the mainstream approaches, narratives,

frameworks, theories and ontologies of sustainable development. They call for a transformation in

human relations with the natural environment, as well as more radical agencies and ambitions for

societal change (Beacham, 2018; Gayá and Phillips, 2016; Heikkurinen et al., 2016; Johnsen et al.,

2017; Parker et al., 2014; Wright et al., 2018). Joining this call, we turn to the degrowth movement

that advocates a creative energy descent with dramatic and voluntary reductions in societal metab-

olism, especially in the most affluent economies (Kallis, 2018; Martinez-Alier et al., 2010). The

scholarly discussion on degrowth is based on the ecological critique of matter-energy intensive

practices that tamper with the limits to growth. It is also a cultural critique to re-order societal pri-

orities from the narrow GDP-indicators to more holistic objectives of human and planetary well-

being (Latouche, 2009). Degrowth represents a search for alternative conceptions of well-being in

response to the crisis of the consumerist culture (Fournier, 2008). Inspiration is drawn, for exam-

ple, from the Buddhist notion of “right livelihood” that encourages enoughness, moderation, suf-

ficiency, conviviality, and simplicity, and promotes non-violence towards non-humans and nature

as a whole. The degrowth movement connects also to alternative conceptions of development, such

as Buen Vivir in South America or Ubuntu in South Africa, which embed human well-being into

community and the natural environment. In other words, the exclusive focus on technology and

markets is not enough—and is indeed counter-productive—as change is also needed in human

mind and culture colonized by the growth imperative (Latouche, 2009; Levy and Spicer, 2013).

A few recent empirical studies identify a group of ecopreneurs sceptical of green growth and

sustainable development agendas (O’Neill and Gibbs, 2016; Vlasov, 2019). Largely overlooked by

research and policy, some of these ecopreneurs are found to reject mainstream notions of business

success and well-being rooted in the profit maximization imperative (Nesterova, 2020). They

might approach their business as part of a personal commitment to decouple quality of life from

high levels of income and consumption, and reject profit in favor of non-economic values (e.g.

meaningful work, personal well-being, pro-environmental commitments, etc.) by means of down-

shifting and voluntary simplicity (e.g. Eimermann et al., 2020). Importantly, what distinguishes

alternative ecopreneurship is not just its agnosticism about profit maximization, but also that it

problematizes the growth paradigm on the macro-level (Gebauer, 2018; Parker et al., 2014).

Accordingly, alternative ecopreneurs incorporate values of the degrowth movement, including

solidarity and sufficiency, and forgo business opportunities with negative social or ecological

implications (Gebauer, 2018). It is also claimed that these ecopreneurs “create projects aimed at

changing the culture and economy from the bottom up” (Staggenborg and Ogrodnik, 2015: 726)

and experiment with “organizing social-ecological life along more regenerative, equitable and

ethical lines” (Wright et al., 2018: 463).

It is evident that degrowth would imply a deep transformation in the identities and practices of

ecopreneurs, which includes (re-)embedding them in the natural environment. Ecological embed-

ding represents, first and foremost, a shift from anthropocentrism towards ecocentric ontologies of

organizing (Heikkurinen et al., 2016). While entrepreneurship is already considered by many

researchers as an embedded rather than purely economic process (Welter, 2011), this embedding

has primarily concerned social embeddedness, where social ties shape business venturing (e.g.

McKeever et al., 2015). In the Polanyian tradition, embeddedness has been used to position entre-

preneurship within the social economy (Peredo and Chrisman, 2006), but not explicitly in nature.

Sociomateriality studies have further recognized the entanglement of the social and materiality in

Vlasov et al.

5

organizing (Orlikowski and Scott, 2008), whereby entrepreneurial processes are constructed

through a variety of artefacts, materials, material practices, and bodies, in parallel with affective,

mental and discursive activities (e.g. Fors & Lennefors, 2019; Korsgaard, 2011; Poldner et al.,

2017; Poldner et al., 2019). Ecological embedding extends this relational view to include ecologi-

cal materiality and non-human beings, for example rocks, rain, fire, ice, water, trees, animals,

birds, and climate, into the processes of sensemaking and organizing (Bansal and Knox-Hayes,

2013; Whiteman and Cooper, 2011). In the words of Gibson-Graham and Roelvink (2010: 322), an

ecocentric ontology signifies “being transformed by the world in which we find ourselves—or, to

put this in more reciprocal terms, it is about the earth’s future being transformed through a living

process of inter-being.”

Ecological embedding is also a spatio-temporal move toward a more intimate physical, emo-

tional and spiritual relationship with ecosystems. Owing to its limited vocabulary to express how

organizations are embedded ecologically, Western techno-science has long turned to the native

ontologies of indigenous peoples (Ingold, 2000). In their study of traditional ecological knowledge

of the Cree tallyman in the Canadian north, Whiteman and Cooper (2000) define ecological embed-

dedness as the degree to which one is “rooted in the land—that is, the extent to which [one] is on

the land and learns from the land in an experiential way” (Whiteman and Cooper, 2000: 1267). In

other words, they suggest that the tallyman’s sense of place, deep ecological beliefs of reciprocity,

respect and caretaking, together with experiential knowledge and extended physical presence in

the non-built environment, provide the essential foundation for engagement in sustainable manage-

ment of natural resources. Accordingly, some recent studies acknowledge the importance of direct

affective-material exchanges with the ecosystem and non-human beings in the emergence of

regenerative production and organizational practices (Vlasov, 2019), more-than-human ethics of

care (Beacham, 2018), local resilience (Korsgaard et al., 2016), and sustainable local economies

(Shrivastava and Kennelly, 2013).

While much critical organizational research has scrutinized business-as-usual (Gayá and

Phillips, 2016), the literature is short on empirical studies exploring the alternative ecopreneurs

who “escape the economy” (Fournier, 2008) and adopt ideas and practices of degrowth. More

specifically, reconnecting ecopreneurs with the natural environment appears to be an important

constituent of sustainable organizing (Shrivastava and Kennelly, 2013; Vlasov, 2019), but there is

a dearth of research on ecological embeddedness of ecopreneurs. The problem with our current

knowledge of ecological embeddedness is that seeking inspiration in the native ontologies of indig-

enous peoples runs the risk of reproducing over-romanticized and neo-colonial images of the

indigenous land ethic—ignoring the totality of economic, political, cultural, and environmental

factors, discursive production of knowledge, and relations of power (Banerjee and Linstead, 2004).

There is a need for new theoretical frameworks and empirical studies on whether and how ecopre-

neurs can become ecologically embedded in the context of modern societies and capitalist growth

economies that have lost all touch with local ecologies, as well as what implications ecological

embedding would have for the engagement of these ecopreneurs with degrowth. This brings us to

the root problem, namely the need to bridge mind and ecology in organization theory.

Critical ecopsychology

With the aim of embedding “mind” into “ecology” in organization theory, we turn to critical ecops-

ychology. In its simplest, ecopsychology positions the human psyche (including identity, well-

being and mental health) in the wider ecological context.

In his book, The Voice of the Earth (1992), Theodore Roszak, historian and critical theorist,

presented the first coherent outline for ecopsychology. Following his analysis, “healing” of the

6

Organization 00(0)

planet’s biosphere is impossible without healing of the underlying neurosis, that is, the alienation

and estrangement of humans from the more-than-human natural world. From the invention of agri-

culture to the recent history of hyper-modernization, humans have sought to emancipate them-

selves from the “tyranny” of nature and to master it with the help of technology. The quintessence

of this separation to Roszak is the Western, urban-industrial civilization. The modern civilization

is psychopathological because it rationalizes the destruction of nature for the sake of human “pro-

gress.” It is mad because it requires psychological surrender to “the great social machine” detri-

mental to human well-being; just as it requires the surrender of non-human life to industrial

development. Roszak (1992: 308) writes:

“It may well be that more and more of what people bring before doctors and therapists for treatment—

agonies of body and spirit—are symptoms of the biospheric emergency registering at the most intimate

level of life. The Earth hurts, and we hurt with it. If we could still accept the imagery of a Mother Earth,

we might say that the planet’s umbilical cord links to us at the root of the unconscious mind.”

Roszak considers humans to possess a deep, inherited sensitivity to the natural environment—an

ecological unconscious. This sensitivity, also known as biophilia, or an “urge to affiliate with other

forms of life” (Kellert and Wilson 1993: 416), is explored by the growing research community of

ecopsychology that places “psychology and mental health in an ecological context.”1 Gardening

and contact with animals is increasingly used to rehabilitate people with burn out, stress, or drug-

related issues (Steigen et al., 2016). In Japan, forest bathing, where a distressed urban dweller takes

mindful walks in the forest, has been documented for its physiological benefits (Park et al., 2010).

There is evidence that spending time in green environments and engaging in outdoor activities,

such as mountaineering, climbing trees, fishing, or birdwatching, can reduce psychological stress,

improve physical health, and encourage pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors (e.g. Soga and

Gaston, 2016).

At the same time, the implications of “a mind being embedded in nature” are not limited to the

aesthetic-expressive sphere of the affective and bodily experience of nature. The thick bodily expe-

rience is important to “foster a sense of connection with nature [. . .] to overcome the delusion that

we could ever be sane while alienated from our earthiness” (Fisher, 2013: 24). Yet, critical ecopsy-

chology also has a moral-political ambition to scrutinize “the major structures of our society [that]

generally function by rubbing out that connection.”

The deep roots of ecopsychological crisis, to Fisher, reside in the culture that “is not structured

to care for life. . .[where] to be successful. . .one does not serve nature but rather the expansion of

capital” (Fisher, 2013: 161). It is impossible to fully understand psychological distress in contem-

porary organizations and societies, without recognizing the growing human separation from the

ecological context where the self is “being redefined to fit an industrialized context” (Kidner, 2007:

123). As modern capitalist societies are moving towards a globally engineered planet, further away

from the local ecologies, they sustain the story of “progress” by exerting control over human and

non-human nature that is increasingly in revolt2.

“We experience the revolt of our own nature as our body’s painful rebellion against repressing social and

cultural conditions. . .our bodies saying “no” to the crushing demands and abuses of modern life. The

revolt of nonhuman nature, on the other hand, manifests as mutating bacteria, mudslides, droughts, and the

ecological crisis in general.” (Fisher, 2013: 158)

Our intention with the notion of “inner” nature is not to reproduce a view where questions of mind

and nature are again separated, but rather to emphasize processes manifesting in individual beings,

Vlasov et al.

7

like ecopreneurs. The “inner” and “outer” are employed as analytical categories, or spheres, whose

existence cannot be simply rejected. Nevertheless, we defy the boundaries between the “inner

nature” of the psyche and the “outer nature” of the environment, by locating the mind in nature—

and hereby “healing our dualism by returning soul to nature and nature to soul” (Fisher, 2013: 9–10).

Our critical ecopsychological lens can be further elaborated with the help of the French psycho-

therapist and philosopher Guattari (1989). Guattari developed an ontology consisting of three

ecologies: mental ecology (psyche, or human subjectivity), social ecology (e.g. organizations and

communities), and environmental ecology (ecosystems, or what is often called “nature.”) In his

work, these three ecologies are inter-related and locked within the productivist vectors of capital-

ism that exploit living ecosystems, and degrade the community, just as they lock individual life into

the cyclical patterns of going round and round in circles with no room for existential feelings “of

being lost in the Cosmos” (Guattari, 1989: 50). Such productivism reduces ecological, social, aes-

thetic and other values to the logic of profit, while individual life, the social sphere, and ecosystems

gradually lose their diversity. Guattari (1989) argues that “there is at least a risk that there will be

no more human history unless humanity undertakes a radical reconsideration of itself” (p. 68),

which in his words requires a revolt against the dominant capitalist subjectivity and its grip on the

three ecologies.

Back-to-the-land ecopreneur through the lens of critical

ecopsychology

We use critical ecopsychology to analyze the experiences and practices of ecopreneurs within the

contemporary back-to-the-land movement in Sweden. Back-to-the-landers are treated here as a

re-emerging wave of people who come from non-agrarian backgrounds and make often radical

changes in their lifestyle, profession and place of residence to adopt a predominantly agrarian way

of life (Mailfert, 2007; Ngo and Brklacich, 2014; Wilbur, 2013).

Over a period of three years, the lead author visited, observed and interviewed 11 back-to-the-

landers in Sweden (Table 1). The interviews were narrative and open-ended, providing space for

the participants to tell their stories. The interviews, lasting between 1 and 3 hours, consisted of

retrospective accounts, where the participants were making sense of their personal journeys to the

land, as well as the experiences and practices of living an agrarian life and starting small-scale

enterprises in agriculture. To get closer to the relationship of the ecopreneur with the land, the

interviews were complemented by participant observations (cf. Whiteman and Cooper, 2000). The

lead author visited the participants’ farms for periods ranging from 1 day to 2 weeks and assisted

them with daily tasks. The interview transcripts and field notes make up the primary data in this

research.

We will now proceed to describe the empirical context and how critical ecopsychology was

used to analyze and narrate the experiences of back-to-the-land ecopreneurs with three vignettes.

Back-to-the-land ecopreneurs as empirical context

The contemporary back-to-the-landers in Sweden provide a unique context to investigate the rela-

tionship between ecology and the mind. Halfacree (2006: 314) explains that “attainment of a rural

consubstantial life, whereby everyday lives and ‘the land’ mutually constitute one another, is ‘radi-

cal’ within contemporary society as the dominant tendency [. . .] is towards a distancing of people

from the soil.” Such life is in sharp contrast to the urbanization trend that takes place globally,

particularly in cultures that undergo fast modernization3.

8

Organization 00(0)

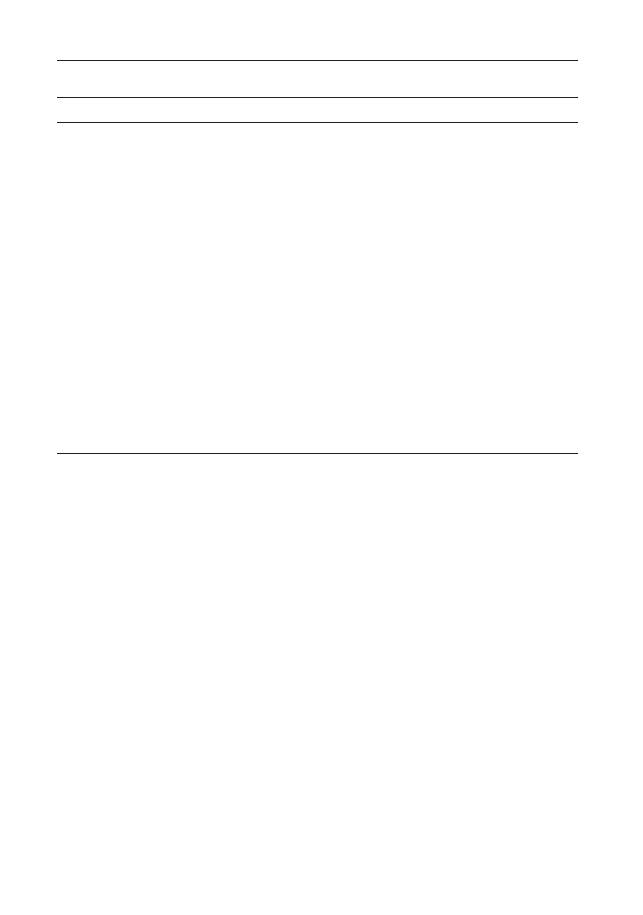

Table 1. Back-to-the-land ecopreneurs in the study.

Participantsa

Ecological enterprise

Land

Location

Oliver, 33 yo, restaurant

chef

Maja, 37 yo, teacher

Agnes, 50 yo, analyst at

international corporation

Erik, 36 yo, truck driver

and student

Julia, 33 yo, physics

student

Emilia, 33 yo, architect

Johan, 36 yo, graphic

designer

Sophia, 28 yo, physics and

engineering

Tomas, 32 yo, horticulture

degree

Laura, 31 yo, MSc in plant

biotechnology

Philipp, 39 yo, analyst at

major energy corporation

Urban organic farm, permaculture

principles, food processing, sell to

restaurants and Rekob

Urban organic farm organized as a

cooperative, community supported

agriculture, consultancy services

Certified organic farm, sell to local

supermarket and Reko

Certified organic farm organized as a

cooperative, community supported

agriculture, farm shop

Diversified farm, permaculture principles,

community supported agriculture, Reko

Certified organic farm, Community

Supported Agriculture, farmer’s market

Diversified farm, mainly organic

principles, livestock, community

supported agriculture, Reko

Forest garden, plant nursery,

permaculture books, education and

consultancy services

0.25 ha, lease

0.2 ha, lease

13 ha, own

9 ha, own

1 ha, borrow

0.5 ha, lease

4 ha, own

0.6 ha, own

Southern Sweden

Southern Sweden

Northern Sweden

Southern Sweden

Southeast Sweden

Central Sweden

Northern Sweden

Central Sweden

aAll names apart from Philipp are pseudonyms. Background indicates main occupation before starting with agriculture.

bReko are self-organized grassroots markets for local food that utilize social media.

Throughout Western history, back-to-the-landers have come in many waves, idealizing a more

grounded, simple, autonomous, self-reliant life in the countryside. The back-to-the-land sentiments

can be traced back to the romantic and transcendentalist ideals of humans emancipating themselves

from the negative effects of society by going to nature, meditating, and growing their own food

(Thoreau, 1960). Agrarian life has been celebrated for its moral benefits—as a way to “allow a

restoration or recapture of a free and natural existence that had been lost” to modernization and

capitalist culture (Danbom, 1991: 3). This idea was expressed in the counterculture of the

1960s–1970s, where urban residents, mainly youth, sought to construct rural communal utopias

(Mailfert, 2007). However, their “small-scale refusal to have anything to do with society” (Howkins,

2003 in Halfacree, 2007: 204) had a limited degree of success due to the physical toil of farming,

problems in communal decision-making, conflicts with the locals, and economic challenges among

other issues (Mailfert, 2007).

The engagement of the contemporary back-to-the-landers with the land and with mainstream

society takes a different form compared to the reactionary anti-urbanism of the past. This is not

least reflected in the increased digitalization, urban-rural linkages, and focus on individuals and

families who start businesses in agriculture and food production based on environmental and life-

style aspirations (Ngo and Brklacich, 2014). These new farmers rely on diverse economic and

livelihood practices, including growing food for their own consumption, homesteading, wage

employment outside of the farm, and starting enterprises such as small-scale organic farms, market

gardening, diversified farming systems, food handcraft, permaculture and perennials, community-

supported agriculture, education, and tourism (Ferguson and Lovell, 2017; Monllor i Rico and

Fuller, 2016).

Vlasov et al.

9

On the one hand, the engagement of “back-to-the-land ecopreneurs” (also known as new farm-

ers) in self-sufficient, close-to-nature, ecological lifestyles, appropriate technologies, and alterna-

tive food economies is considered to embody radical ideas of societal change (Wilbur, 2013).

Through their productive relationship with the land, they are claimed to create new material spaces

that challenge the global agro-industrial food system and address contemporary political concerns

such as “human and non-human welfare, environmental sustainability and post-capitalist economic

relations” (Wilbur, 2013: 149; see also Calvario and Otero, 2014; Monllor i Rico and Fuller, 2016).

Back-to-the-landers are also linked with grassroots movements such as intentional eco-localization

in response to the issues of peak oil and climate change (North, 2010), and with the food sover-

eignty movement that celebrates the role of smallholder livelihoods in constructing sustainable and

resilient local communities (Holt-Giménez and Altieri, 2013).

On the other hand, back-to-the-landers might remain at the fringe of the mainstream economy;

and they find themselves operating in highly competitive capitalist markets, which might under-

mine their critical differences (Calvario and Otero, 2014; Halfacree, 2006). The messy and ambig-

uous nature of alternatives is a common topic of debate in literature on alternative food movements,

which operate both against and within the conventional food system and its capitalist framing

(Beacham, 2018; O’Neill, 2014). The promises of alterity, community and environmental sustain-

ability in alternative food movements should therefore be evaluated on a case-by-case basis

(Forssell and Lankoski, 2015). There is a need to put the identities of new farmers into perspective,

as they navigate through the dominant discourses, as well as the human and non-human elements

in their immediate environment, while practicing more-or-less alternative livelihoods and agricul-

ture (Holloway, 2002). In this way, the stories of back-to-the-land ecopreneurs might reveal “the

gradual opening of imagined and realized possibilities” (Wilbur, 2013: 157). Such clearing could

occur if the ecopreneurs were able to disengage from some of the structures of the modern capital-

ist economy and create alternative organizing that is more embedded in local ecology.

Critical ecopsychology as analytical lens and the three vignettes

A focal observation for the emergence of this article was “suffering.” When we first analyzed the

material, what caught our attention was the painful experiences of anxiety, burn-out, depression

and stress in the retrospective accounts of the participants concerning their previous life and work.

The intensive experience of psychological suffering appeared as a turning moment for many par-

ticipants in their decision to leave the office and/or the city, move to the countryside, and engage

in ecological agriculture.

Intrigued by this finding, we turned to critical ecopsychology as an analytical lens. It allowed

us to analyze, on the one hand, alternative and dominant economic discourses (O’Neill and Gibbs,

2016; Phillips, 2013) and value regimes that materialize discourses in everyday life (Levy and

Spicer, 2013); and on the other hand, the natural environment and non-humans (Whiteman and

Cooper, 2000, 2011), and how they meet and interact in the embodied experience and material

practices of the ecopreneurial subjects. Following Allen et al. (2017), we therefore assumed “eco-

centric radical-reflexivity,” which means revealing interrelationships between actions, values,

and the social and material world in order to highlight unsustainable systems and search for alter-

native praxes.

The analysis was abductive and iterative. We moved between the rich stories of the participants

and the theoretical realm of ecopsychology, while also bringing in conceptual insights from eco-

preneurship, ecological embedding and degrowth. The result of this process is three vignettes cap-

turing how modern suffering catalyzes alternative ecopreneurship (Table 2). In ecopsychological

terms, these vignettes represent three “counter-practices” (Fisher, 2013: 174), where the

10

Organization 00(0)

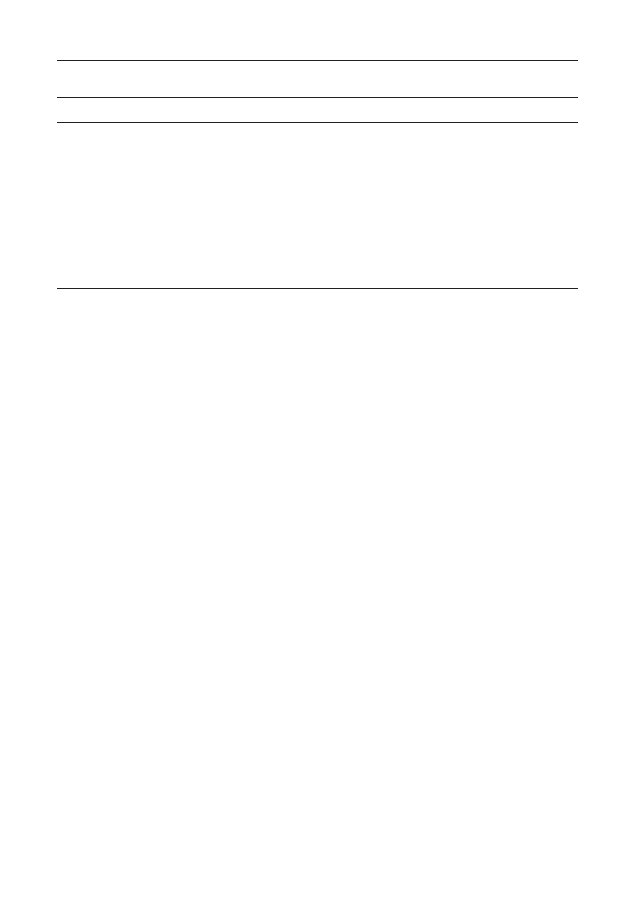

Table 2. Ecopsychological counter-practices.

Counter-practice Modern suffering Ecological embedding

Implications

Grounding

Re-sensitizing

Regenerating

Burn-out from the

career rat race

Experiential

deprivation of office

work

Ecological anxiety

Local self-reliance (re-skilling

and using local resources)

Contactful work (creative

physical labor of small-scale

diversified farming)

Regenerating soil (through

permaculture and community-

supported agriculture)

Negotiating dependence on

profit, consumption, and

material infrastructures of the

growth economy

Negotiating the degree of

technology and its impacts on

health, work, social justice, and

environmental sustainability

Negotiating local agency in the

face of systemic violence and

runaway climate change

experience of suffering is seen as an inner revolt against modern society and growth capitalism,

nudging the ecopreneur to reconnect with the land and adopt degrowth practices. We selected these

specific vignettes because they vividly represented the depth and diversity of this dynamic. These

vignettes have also been shown to resonate with the personal experience of academic and non-

academic audiences alike during presentations and discussions of this article. The vignettes consist

of two parts: an empirical part that is constructed based on interviews and observations; and an

analytical part where our interpretive voice takes primary place.

Three counter-practices that embed ecopreneurs ecologically

The three vignettes present ecopsychological counter-practices that embed ecopreneurs ecologi-

cally (Table 2). The first counter-practice (grounding) concerns Philipp, previously an analyst at a

major energy corporation, who after a near burn-out downshifted and moved to the countryside and

engaged in forest gardening to become more self-sufficient. The second counter-practice (re-sensi-

tizing) concerns Sophia, who left the prospects of an alienating “office career” for the sake of the

creative physical work of small-scale diversified farming. The third counter-practice (regenerat-

ing) is an account of ecological anxiety, which urged Johan, a freelancing graphic designer, to

regenerate soils with permaculture and community-supported agriculture.

Grounding: From the “rat race” burn-out to local self-reliance

Philipp is a renowned author and practitioner of forest gardening in Sweden. Together with his

family and friends, he writes books and develops courses, designs edible landscapes, and runs a

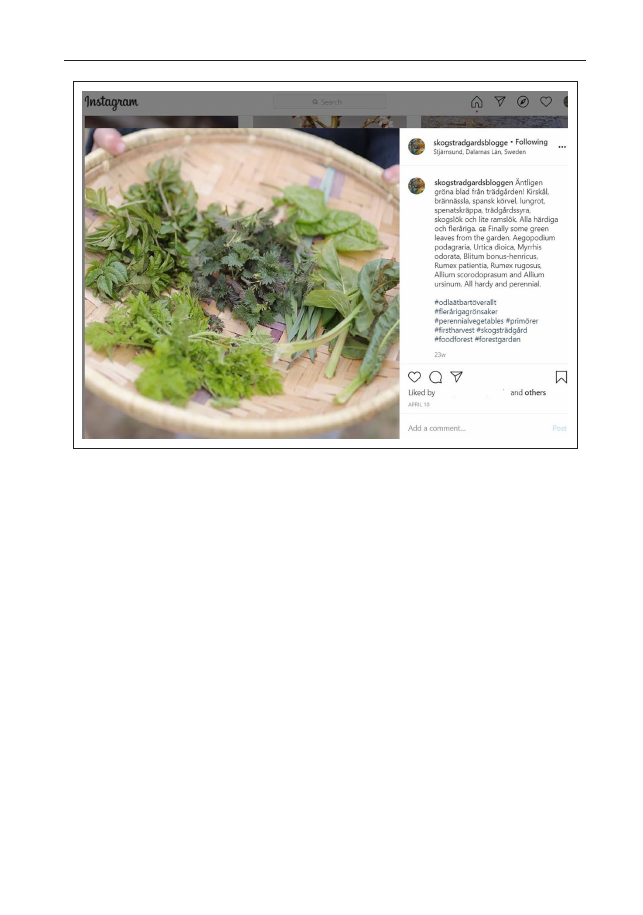

small-scale commercial nursery for edible perennial plants (Figure 1).

One of his favorite edible perennials is ostrich fern, or fiddlehead (Matteuccia struthiopteris). It

can be found in forests and natural reserves. An adult plant looks like a bunch of long feathery

ostrich plumes. The edible parts are the young, curled shoots, about 5–15 cm long, that look like

the scroll of a violin. Philipp would harvest the shoots in early May. Rich in vitamin A, they remind

him of asparagus in taste and texture. He would cook or steam the shoots, or use it in preserves. A

risotto with fiddleheads is a delicacy.

The extensive knowledge of perennial plants and the luxury of harvesting his own food from the

land is in sharp contrast with Philipp’s previous life in the city. It did not take long for him to “hit the

wall” after he started at his well-paid job as a strategic analyst at a major energy company. One of

Vlasov et al.

11

Figure 1. (Credit Philipp Weiss, permission obtained). A plate of first seasonal perennial leaves from the

garden. Philipp has a popular Instagram account where he documents his experiences.

his tasks was to analyze reports from the WWF, Greenpeace, and the World Bank. From the reports,

he discovered the dark future of energy, climate, environmental destruction, and resource scarcity.

The corporate environment felt more and more devoid of meaning. It felt narrow-minded to

commute to work every day. Philipp felt an inability to act. He became depressed, even losing

hope. The “unfreedom” of working for money was felt in the bones, along with the acute sense of

societal collapse unfolding. He “felt very limited as a human being, with tied hands and not free—

needing to find another way, but there were no role models, people who worked less and felt better,

it was more like either you work, or you are unemployed, and you do not want this either.” In his

words, he was “kind of finished.”

This experience urged him to gradually reduce his working time and eventually move to a small

cottage with a plot of land together with his partner. At first, they could barely use a hammer and a

nail, but with time, they renovated the house with local, natural, and reclaimed materials. They

now make their own firewood, tap birch sap from the nearby forest, and grow a wide variety of

berries, fruit, nuts, annual, and perennial vegetables that cater for much of their nutrition needs.

In spite of his engineering background, Philipp is sceptical about technology. In the house, a

root cellar stands in for an electric refrigerator. Instead of installing a sophisticated heating system,

he would wear two wool sweaters indoors in the winter. There is also a vibrant local community in

the village that exchanges knowledge, support and resources. This includes a network of permacul-

ture enthusiasts who meet every month to help each other with daily work. All this keeps living

expenses low compared to an average Swedish household.

12

Organization 00(0)

The business brings an income that is small, albeit enough for “a good life.” It also provides

meaningful work and everyday life immersed in the diversity of sounds, colors, smells, and tastes

of the forest garden. At the rate the plants sell out every season, the plant nursery could easily be

scaled up threefold. “It could be good with some profit,” Philipp says, which could be invested in

tools or frequent trips to collect new plants. However, to scale-up a business would also mean

becoming a manager, diverting time from things that really matter. Still fresh is the painful experi-

ence from the times when he mainly worked for money. Already now, juggling gardening for his

own needs and running a business in the peak of the summer season may sometimes push him back

to the edge of burn-out.

Analysis of grounding. Through our ecopsychological lens, burn-out can be seen as the depletion of

the human mind (Fisher, 2013) going hand-in-hand with the anthropogenic overshoot of the bio-

sphere. Philipp’s experience of near burn-out is a wake-up call that punctuates the productivist

mode of being, or Enframing (Gestell) in the vocabulary of existential phenomenology (see Hei-

degger, [1952-1962] 1977). The feeling of being forced to run faster and faster is how the accelera-

tion of modern society, powered by fossil fuels, registers on the level of human experience. This is

a form of “prison,” but the kind that one subscribes to voluntarily for its seductive efficiency and

comforts (Guattari, 1989). The rat race is a vivid representation of this prison. It is associated with

the vicious cycle of “professional, respectable waged work and consumer bliss” (Carlsson and

Manning, 2010: 937–938). On a large scale, it is sustained by policies that promote consumerism,

more jobs for the sake of jobs, and more innovation for the sake of innovation.

From the inner revolt of burn-out, grounding springs up as a counter-practice that brings the

depleted mind and the natural environment more in tune with each other by means of self-reliance.

Self-reliance is linked to downshifting and voluntary simplicity, which reflect the motion of scaling

down and slowing down one’s work and consumption to make time for things that are perceived as

important in life (Sørensen, 2020). What grounding reveals is the critical role of the land—as a

source of material and immaterial needs—in the reshuffling of dependencies on the cultural norms

of full-time work, consumerism, the productivist notions of “progress,” commodity markets, and

material infrastructures of the growth economy (cf. Fournier, 2008).

By re-skilling and living off the local resources of the land, Philipp discovers what has real

value in the economy of dwindling ecosystems, peak oil and climate change. The soil gives nutri-

tious food, the root cellar would store it independently of the electricity grid, and a local commu-

nity becomes a source of mutual help. Local self-reliance can even be described as a quest for

“rewilding,” or primitivist re-skilling in food production and other forms of subsistence (Gammon,

2018). This may open-up bioregional practices with lower matter-energetic intensity characteriz-

ing a degrowth society (Pungas, 2019), while also preparing for a possible collapse of modern civi-

lization (Taylor, 2000). These ideas are reflected in Phillip’s ecopreneurship, where business is part

of a personal commitment to be a role model that he himself missed when he was stuck in “the rat

race”; and to identify and spread plants and techniques that work in the northern climate to chal-

lenge unsustainable land use.

At the same time, Philipp is not a hermit independent of “the economy” (cf. Fournier, 2008).

From an ecological point of view, his continued dependence on social media, money, or transporta-

tion networks means that degrowth on a micro-level might feed into the environmental exploitation

happening on the macro level and in some other places (e.g. mining, cooling of data centers, etc.).

Moreover, there is a humanist critique of whether people like Philipp are hypocritical as they still

rely on the comforts of modern infrastructures and the welfare state, but contribute little to the tax

base and economic growth. Yet, this critique comes from within the system that Philipp is trying to

challenge and which has a vested interested in delegitimizing alternatives (Levy and Spicer, 2013).

Vlasov et al.

13

As a counter-practice, grounding enacts an ongoing negotiation of the boundaries between the

grounded/wild (e.g. low levels of consumption, growing and harvesting perennial plants) and the

modern (e.g. running a business, maintaining an Instagram account) in the unfolding revolt against

the productivism that exploits the mind and the natural environment.

Re-sensitizing: From experiential deprivation to contactful work of small-scale

diversified farming

Not all back-to-the-landers are, of course, particularly interested in self-reliance. Sophia, who like

Phillip comes from an office background, insists that she is not a “stereotypical kind of back-to-

the-lander,” who is in it for “growing her own food” and “feeling each and every plant.” These

things do not interest her as much as running a new sort of business in agriculture.

She runs a small-scale, organically certified, diversified farm located in the midst of a tradi-

tional agricultural region in Sweden. It is meaningful for her to build something from scratch and

to see the clear results from the seed to someone’s plate. “I love this feeling, like when I sell some-

thing, it is really the fruits of my work, I didn’t just get this money because I was sitting somewhere

for 8 hours in a row, this is how it felt before, I could sit, drink coffee, go to the toilet, and the whole

day like this.”

In her “previous life,” Sophia had a lot of sleep problems. She studied physics in college and

university. Her grandparents had a farm, and she always wanted to work with something that

involved being outdoors and doing practical things, for example making measurements for wind

power plants. Her first jobs did not satisfy this longing. She realized that “one gets to do this kind

of work rarely, and even when you are out and take measurements [. . .] it takes just several min-

utes, because everything is done automatically, you just install the device and go away.” With a

prestigious Fulbright scholarship, she also worked to analyze the efficiency of solar energy cells.

The work felt meaningless and boring. “It felt like I was just a cog in a big machine, which would

anyway keep going, even if I, as a small cog, fell out of it. It felt like I wasn’t really needed.”

After a few years in an agricultural school, Sophia and her partner moved into a house with a

small plot of land that they rented from a large-scale industrial dairy farmer. Much of the work is

done by hand and with an old tractor. She is outside a lot. Some days, she is out fifteen hours

straight, in the rain, going back and forth with the crates (until two o’clock in the morning) in order

to be on time for the farmers’ market. “Even though I feel tired and exhausted, I feel good about

moving during the day—I notice how low my mood is when I have to sit inside and do accounting

and similar things,” she says with soil on her forehead and hands. “I don’t need to go out and exer-

cise during my “free time.” The cows from the nearby farm came by the other day and I helped the

neighbor to nudge them back. I don’t need to run after this. I feel better physically apart from those

periods when there is simply too much.”

While she likes to be outside in “nature,” she notes that “yes,” here one has to put up with all

the noisy, gasoline-smelling trucks of the neighboring farmer that sweep past the house day in day

out. “Not everyone would tolerate a life like this.” A big part of the day can go into driving a car

delivering produce to the city rather than doing “fun” things. Farming is meaningful but often

monotonous and hard, with long days where the weather and season steer a lot. Sophia would not

mind scaling up her business to have more land to rotate the crops, to employ someone, and to have

more machines. Perhaps from a more radical perspective, she thinks that the hard work of small-

scale farmers is invisible in the eyes of consumers, who are spoiled by supermarkets and do not

fully value the effort that is put into growing crops; as well as the big chemical corporations such

as Monsanto, who extend their monopoly on seeds.

14

Organization 00(0)

With all respect to conventional farmers, she would never use pesticides herself. “I don’t want

to use chemicals—she says with a nervous laugh—it is a personal thing. I had a summer job at a

conventional farm, [and] I was there at the moment when they sprayed chemicals. It smelled so

strongly of it, it was on the clothes, on me, it just felt unhealthy, for me and for the land.” Done in

the right way, she means, “diversified organic farming is more sustainable not just for the environ-

ment but for yourself—to take care of the land. . .on which you depend.”

Analysis of re-sensitizing. This second vignette captures the promise that contactful work (Fisher,

2013)—the work that is in close bodily contact with the land—holds for alternative ecopreneur-

ship, as opposed to the experiential deprivation of mechanized and automated labor in the ecomod-

ernist vision of the future. “As entrepreneurship theory shifts towards valorization of mind work”

(Campbell, 2006: 180), it is not hard to see why one’s body might so desperately crave to escape,

to get out (see Michel, 2011). Sophia’s experience reflects how the urban, office and high-tech

environment, where modern subjects are mostly spending their time, is notorious for being poor at

encountering the diversity of living non-human beings (Fisher, 2013). The so-called knowledge

work is often seen as forward-moving “progression,” intended to liberate humans from toil. Yet, it

might also be creating toil of its own. Fisher notes how advanced technology infiltrates the fabric

of life—not only displacing natural environments with mines, dams, data servers etc.—but also

displacing the rich experience of the world. It turns work into the maintenance of industrial machin-

ery and leisure into its consumption.

The counter practice of re-sensitizing reflects “deliberate contact-making” (Fisher, 2013: 178),

or a search for more resonant and “real” bodily experiences, in the technological world. Contactful

work for Sophia starts with an immediate concern for personal well-being, but it does not end

there. In the context of agriculture and food, the body and embodied interaction with the land

becomes a site where the degree of technology is negotiated as part of the everyday politics of

smallholding (Holloway, 2002; Wilbur, 2013, 2014). Just as Whiteman and Cooper’s (2000) indig-

enous hunter, ecological practices of small-scale diversified farming are described to rely on local,

tacit and indigenous forms of knowledge, as opposed to industrial agriculture where the farmer is

treated as a consumer of codified knowledge that can easily be rolled out at scale (Wilbur, 2014).

To Berry (1996), even the smallholder radiates an ecological ethos of physical labour, patience,

local and low-technological ways. In the case of Sophia, negotiating the degrees of technology

connects with the issues of meaningful work; social justice (e.g. control imposed by food corpora-

tions vs autonomy and sovereignty of local practices); and environmental sustainability (e.g. the

negative impacts of chemicals or excessive ploughing of the soil).

The call for matter-energetic degrowth is often discussed in connection with the reduction of

working hours (Kallis, 2018). However, one might also expect that in a post-growth society there

will not be less, but indeed more work—just of a different kind—as creative physical labor, like

local food production, substitutes the reliance on fossil fuels and advanced technologies. On the

one hand, the rule of technology is still very much present in Sophia’s life. Tractors, computer

programs, cars to name but a few, are means to develop an efficient commercial farming operation.

On the other hand, there are also instances of “releasement” from technology (Heikkurinen, 2018),

such as the rejection of chemical pesticides. In addition to endosomatic instruments, such as her

hands and nails, she employs appropriate technologies, such as human-powered tools or organic

techniques, which give a taste of a downscaled organizational metabolism and a reduced societal

matter-energy throughput. Without reverting to individualism, the counter-practice of re-sensitiz-

ing relates to “the choices we make between either disengaging from or engaging with reality that

we confirm or protest the rule of technology” (Fisher, 2013: 178).

Vlasov et al.

15

Regenerating: From ecological anxiety to regenerating soil

It is only recently that the soil has been recognized as being alive by modern societies (Puig de la

Bellacasa, 2017). Topsoil is the outermost layer of soil, and is just 10–25 cm thick, but it contains

a high concentration of organic matter and microorganisms. It is the earth’s fragile skin that anchors

all life on Earth. It is estimated that half of the topsoil on the planet has been lost in the last

150 years, primarily due to heavy erosion from industrial agriculture, and regenerating topsoil is a

slow process. Every centimeter can take up to 50 years. However, permaculture practitioners want

to help this process with nature-inspired techniques and organization (Mannen et al., 2012; Puig de

la Bellacasa, 2010; Roux-Rosier et al., 2018; Vlasov, 2019).

Johan identifies himself as a practitioner of permaculture. Before starting with his diversified

vegetable farm, he studied graphic design and had plans to work as a freelance designer, but then

he started experiencing a lot of anxiety. This anxiety was about the world and the destruction of the

environment, about “where we are moving as society—in the wrong direction, where the distance

is getting bigger and bigger between people and between people and nature.”

Johan rented out his apartment in Stockholm, visited several permaculture farms where he was

inspired by other farmers “who saw meaning in the work they were doing,” got a chance to experi-

ment on his grandfather’s farm, and finally found a piece of land “of his own,” which he rents for

free from his partner’s family.

His farm, about one hectare in size, is dig-free and barely uses fossil fuels. It has permanent

beds, which are neither ploughed nor harrowed, apart from a small two-wheel tractor that is occa-

sionally used to cultivate the top layer. “It is the problem with organic agriculture that there is so

much cultivation with machines, one drives a lot, all the time emitting a lot of emissions into the

atmosphere.” Johan himself uses hand-driven tools and builds compost in the soil with organic

mulch that helps to retain moisture and increase nutrients. “Smell this!” Johan lifts some mulch

from the ground with a chunk of black soil. It has many tunnels left by earthworms, and a rich,

earthly, (somewhat) sweet aroma.

Johan wanted “to put things in a different direction, to take things to a smaller scale” by bringing

people closer to food and by farming “with [. . .] positive climate impact.” This proved difficult.

As a self-taught farmer, he learned the hard way that it takes time to learn the place, the soil, and

growing techniques, let alone make them work in regenerative ways, and all this in parallel with

trying to make a decent living by growing vegetables for sale. Johan is keen on perennials: “vegeta-

ble farming is not the best way to build soil,” but it was easier to turn it into a business. There is a

difference between growing food for yourself and doing it commercially because “you are forced

to think more efficiently, to choose crops that work well and have a good margin.”

While Johan is not aiming for high economic returns, anxiety about climate change at times gives

way to economic anxiety because of the insecure financial returns. “Of course, one gets anxious,

when you put a lot of time into the farm and see what it results in and make an economic evaluation

of it. You might easily get depressed.” Yet, he cannot imagine doing something other than working

for a more regenerative society—something he really wants to see emerging further.

Analysis of regenerating. The kind of anxiety that Johan experienced reflects a new psychological

phenomenon that is rapidly taking form in modern societies; namely ecological anxiety (Pihkala,

2018). Psychologists observe a growing anxiety, worry, fear, grief, and despair in relation to cli-

mate change and ecological crisis (Doherty and Clayton, 2011), especially among the younger

generation (WWF, 2018). This anxiety is happening on top of the more acute and traumatic reac-

tions to the extreme weather events and changing environments, often amongst the world’s poor-

est. The American Psychological Association defines ecological anxiety as “a chronic fear of

16

Organization 00(0)

environmental doom.” In our findings, these emotions are common among the back-to-the-landers

who are affected by the depleted state of ecosystems, industrial monocultures and the injustice they

do to biodiversity and human livelihoods, as well as the uncertainty about the future risks leaving

them feeling powerless. Ecological anxiety may be paralyzing, leading to pathological worry,

hopelessness, nihilism, denial, and withdrawal. At the same time, it can also provoke engagement

with environmental issues and ecological identity (Doherty and Clayton, 2011), as also shown by

our data, which in Johan’s case happened through engagement with regenerative farming and com-

munity-supported agriculture.

The focus on agency that can arise from ecological anxiety evokes ambiguous meanings. On the

one hand, anxiety, guilt and other painful emotions that people may feel about the ecological crisis

might put too much responsibility to resolve these systemic crises on individual shoulders (cf.

Whittle, 2015). In the Foucauldian tradition, this can be seen as an example of neoliberal govern-

mentality—the extension of “entrepreneurial subjectivity” into emotional life (see also Scharff,

2016). Such individualist narratives pressure us to consume green products or to start green busi-

nesses—with little consideration for the systemic violence and the rigidity of unsustainable social

and material (infra)structures.

On the other hand, Macy (1995: 241) notes that anxiety in response to the disturbed climate,

dying of species, forests and soils might be “our pain for the world” or “suffering with.” the non-

human. It is “the distress we feel in connection with the larger whole of which we are a part”

(Macy, 1995: 241). Metaphorically, Johan’s pain can be thought of as the plough digging into the

“fragile skin” of the earth, and also getting under the human skin itself, leaving a deep wound.

We can see how Johan’s local agency to regenerate soils comes together with his own striving for

self-healing. In permaculture cosmology, human agency is “nature working” (Puig de la Bellacasa,

2010: 161) and the care for one’s body-self is not separable from the care for other humans and non-

humans. Following Puig de la Bellacasa, however, ecological care in permaculture is manifested

through the messy politics of everyday doings. In spite of the best intentions, Johan has to live with

the reality of the unsustainable agro-industrial food system and its productivist temporalities, which

“speed up” and exhaust soils for the sake of economic utility and cheap food available all year round.

This involves navigating between the agencies and temporalities of the human and more-than-human

worlds (cf. Beacham, 2018), as he co-creates new regenerative, relational webs while still needing to

relate to the conditions of the system he so eagerly seeks to oppose.

The growing curiosity about regenerative organizing (Slawinski et al., 2019; Vlasov, 2019)

might mean further extension of human control over nature through advanced technology and

markets—a form of “stewardship” or “pastoral” care in which humans are in charge of natural

worlds” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2010: 166). However, regenerative ethos could also uncover a new

form of participation in the land that is based on the awareness that “humans are not the only ones

caring for the earth and its beings—we are in relations of mutual care” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2010:

164). If we understand ecological anxiety as a life force deep inside that is screaming for help

(Roszak, 1992), then Johan’s experiences allow us to imagine how this anxiety can catalyze a local

agency that learns to peacefully co-exist with human and non-human others, organizing “within

nature” rather than “with nature” or “to overcome nature.” The question remains as to whether this

agency can realize itself through ecopreneurship in the economic, political and cultural realities

that have lost all touch with local ecologies.

Discussion

To bridge the gap between “ecology” and “mind” in organization theory, the study explored the role of

psychological suffering for sustainable organizing. We analyzed the experiences of back-to-the-land

Vlasov et al.

17

ecopreneurs through a critical ecopsychological lens and found three counter-practices of grounding,

re-sensitizing, and regenerating that embed ecopreneurs ecologically. The contribution of the study to

critical organizational research is threefold: we (1) reveal psychological suffering as one antecedent for

ecological embedding in the context of modern societies; (2) advance an ecocentric ontology of eco-

preneurship; and (3) provide new empirical insights into the messy realities of alternative ecopreneurs,

including tensions that they encounter while navigating between the mainstream economy and the

land. More generally, the study outlines critical ecopsychology of organizations, a framework that con-

nects mind and nature in organization theory and offers a moral-political foundation for societal trans-

formation towards a post-growth world.

Modern suffering as antecedent for ecological embedding

By revealing how psychological suffering—in the form of burn-out from the career rat race, expe-

riential deprivation, and ecological anxiety—prompts ecopreneurs to reconnect with the land, we

establish an important link between ecological embeddedness (Whiteman and Cooper, 2000) and

the critique of the growth economy in organizational literature (Johnsen et al., 2017). The experi-

ence of suffering, which the protagonists use to legitimize their personal journey to the land, rep-

resents a response to the chronic separation of the modern capitalist subject from “nature.” This

experience can be seen as an inner revolt in the ecological unconscious—or an existential wake-up

call—that prompts the protagonists to organize in alternative ways.

In the three vignettes, the embodied, physical contact with the land becomes the cornerstone of

resistance to the discursive and material conditions of modern society and growth capitalism. In the

counter-practices of grounding, re-sensitizing, and regenerating, ecological embedding is what

enables the construction of alternative ways of being, living and organizing along the patterns of

degrowth. Transformation in human relationship with the natural environment has been named as

an important condition for radical agencies of ecopreneurs (Shrivastava and Kennelly, 2013;

Vlasov, 2019; see also Beacham, 2018; Wright et al., 2018). We suggest that future research on

ecological embeddedness cannot limit itself to the study of the rich sensorial experience of the

natural environment (cf. Whiteman and Cooper, 2000) without keeping a critical eye on the need

for deeper inner and societal transformation. Looking for new forms of ecological embeddedness

requires reflexivity about economic, political, cultural, and environmental context, and it is also an

important part of decolonizing indigenous cosmologies and moving beyond romanticizing native

practices in the Anthropocene (cf. Banerjee and Linstead, 2004; Jackson, 2020).

We expect that modern suffering might prove relevant for the broader inquiry into grassroots

agencies that “shift away from endless economic growth and resource efficiency mantras towards

more radical worldviews of degrowth and different ways of achieving happiness and fulfilment in

life” (Carlsson and Manning, 2010; Lestar and Böhm, 2020: 56; Seyfang and Smith, 2007). The

fact that the most “developed” economies are witnessing growing levels of burn-out, depression,

anxiety and other psychological problems is tragically ironic. The extensive use of natural resources

is justified by higher material wealth, which however does not always lead to long-term well-being

(Jackson, 2009; Kallis, 2018). On the contrary, the so-called “progress” can create new hazards

when it comes to psychological health (Sørensen, 2010; see also Vetlesen, 2016). It is not within

the scope of this article to provide universal explanations of the many causes of the mental health

epidemic in the Global North. Neither is it our intention to trivialize psychological suffering (which

can be pathological and harmful), or to suggest that it is desirable or possible to alleviate suffering

once and for all. In the tradition of critical ecopsychology, our ambition is rather to emphasize that

it is impossible to fully understand human sanity and mental well-being without considering the

link between mind, ecology, and culture (Fisher, 2013). Moreover, focusing on back-to-the-landers,

18

Organization 00(0)

who already have alternative values, this article offers a somewhat extreme narration of organiza-

tions, and there is still a need for transferring these ideas to many other contexts and mainstream

society. The questions that we leave for future research include: What further potentialities for

ecological embedding and degrowth might be contained in the mental health epidemic in the

Global North? What individual and contextual factors may influence whether psychological suffer-

ing becomes transformative for some but paralyzing for others?

The focus on psychological suffering runs the risk of individualizing largely societal problems.

As Roszak (1992) suggests in the opening quote to this article, it would not be enough to “fix” the

individual with the help of green therapy, gardening, outdoor activities, or meditative immersions

in nature without changing the institutional and material conditions that make people (and the

environment) sick in the first place. In considering the relevance of ecological embedding to wider

society, one should also keep in mind that growth capitalism is good at capturing the inner revolt

by reducing it to the matters of individual responsibility, musicalizing it, or turning it into com-

modities (Fisher, 2013). Today, the romantic dream of living a more modest life in the countryside

and doing organic farming has entered the collective imagination as a result of TV programs and

computer games (Sutherland, 2020). This development trivializes agrarian life, stripping the back-

to-the-land phenomenon from the complex issues of social and environmental justice. Furthermore,

organizations such as organic farms and plant nurseries, which financially support back-to-the-

landers investigated in this study, partly rely on the market of urban consumers who might remain

stuck in their own “rat race,” and who are desperately seeking small escapes to “nature” by buying

local organic food or perennial plants for their summer cottages. We should remain aware that

ecopreneurship of back-to-the-landers does not only arise from modern suffering, but may para-

doxically become contingent on it. The socially and ecologically destructive mode of mainstream

organizing is not merely, or even primarily, a problem of the individual. It is a product of histori-

cally embedded practices and institutions, and consequently, any solution must also deal with these

levels of analysis.

Ecocentric ontology of ecopreneurship

To bridge the gap between the human psyche and the natural environment, critical ecopsychology

offers an ecocentric ontology of ecopreneurship. As opposed to the mind-nature dualism in organi-

zation theory (Heikkurinen et al., 2016; Parker et al., 2010) and in the opportunity theory of entre-

preneurship (Fors and Lennerfors, 2019), critical ecopsychology de-centers the individual

ecopreneur, positioning her as dwelling-in-the-world (see Ingold, 2000) in ongoing affective-mate-

rial relations with human and non-human others (Allen et al., 2017; Beacham, 2018; Campbell,

2006; Vlasov, 2019; see also Poldner et al., 2019). Instead of viewing ecopreneurship as the indi-

vidual-opportunity nexus limited to the market, this view uncovers the emerging nexus of psyche,

society, and the natural environment where the ecopreneur is moved into action by the ecologically

grounded experience of suffering. Importantly, this suffering is not a property of isolated psyche

(not “inner” as in individualistic accounts of ecopreneurship), but is shaped in transversal interac-

tion with social and environmental ecologies (Guattari, 1989). The origins of this seemingly indi-

vidual pathology can be analytically traced to pathology at the level of society, where modern

society and growth capitalism drive the wedge between humans and the rest of “nature.” This

suffering has then a material foundation in the natural environment to the extent that it concerns a

direct relation with ecosystems, and the embodied experience of unsustainable systems and climate

change for example.

This contribution comes at a time when “attention to human individuals, organizations, and

societies and multiple other systems and their mutual embedding with the natural environment” is

Vlasov et al.

19

called upon (Starik and Kanashiro, 2013: 13). Critical ecopsychology would benefit future research

in exploring relationalities, assemblages, and entanglements of humans and non-humans in the

processes of sensemaking and (un)sustainable organizing (Ergene et al., 2020).

Messy realities of alternative ecopreneurs

Our third contribution consists of providing new empirical insights into the messy realities of alter-

native ecopreneurs, including tensions they encounter while navigating between the mainstream

economy and the land. In contrast with the heroic image of ecopreneurship (cf. Houtbeckers,

2016)4, back-to-the-landers negotiate their dependence on profit, consumption, and material infra-

structures of the growth economy; the degree of technology in their practice; as well as their local

agency in the face of systemic violence and runaway climate change.

Fournier (2008) suggests that the degrowth movement involves not only a dramatic reduction in

material consumption and production, but also “escaping from the economy,” that is, the economic

rationality of consumer capitalism and the market. However, back-to-the-landers do not fully

escape the economy. They still enjoy some of the comforts of modern society, engage with the city,

and start businesses for example. In some cases, again, their direct engagement with the land

results in businesses based on local regenerative food production, frugal and circular use of

resources, deep connection with place and community, and care for the natural environment and

non-humans (cf. Nesterova, 2020). Their notions of well-being, success and a good life may

become less dependent on profit maximization, and their stories might represent non-growth-based

capitalisms and ecologically enlightened civilization. In other cases, the practices of self-reliance,

re-skilling, community-based provisioning, and rejection of advanced technologies might even be

reflective of more radical ideas. These ideas include non-capitalist organizing, bioregional decen-

tralization, anarcho-primitivist critique of civilization, and preparedness for societal collapse.

We do have reasons to doubt whether ecological embedding can ever be realized through ecopre-

neurship. Entrepreneurship may unavoidably evoke subjectivities and practices that are not in line

with the ecopsychological critique of modern society and growth capitalism. Furthermore, it is still

hard for the alternative climate imaginaries represented by back-to-the-landers to gain viable ground

in the socioeconomic, political, and technological arenas that are dominated by the visions of unlim-

ited fossil fuels and technological optimism (Levy and Spicer, 2013). We can confirm that even

alternative ecopreneurs have to navigate the conflicting discourses of degrowth, green growth, and

business-as-usual (O’Neil and Gibbs, 2016; Phillips, 2013). More importantly, they have to adjust to

many institutional, cultural, and material conditions that are set by the dominant growth imaginary. Is

back-to-the-land ecopreneuring destined to remain at the margins of economic organization?

However, by “telling a different entrepreneurial story differently” (Campbell, 2006: 168), we

show how future research can explore the messy everyday politics of constructing alternative

imaginaries at the grassroots level. The three vignettes show that ecopreneurship does not mean a

priori extension of markets and technology into human and non-human life (cf. Imas et al., 2012;

Parker et al., 2014; Verduijn et al., 2014). It may instead take the form of “insurgent” activity that

walks on the boundary between the mainstream economy and alternative economies of the land,

with an intent to protect autonomy, serve the collective and duties to others, and follow a responsi-

bility to the future—“to the conditions of our individual and collective flourishing” (Parker et al.,

2014: 38). We join those who construct counter-stories to reshuffle prevailing frames of ecopre-

neurshp (Campbell, 2006); provide alternative understandings of human relationship with non-