International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Review

Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy:

A State-of-the-Art Review

Margaret M. Hansen *, Reo Jones and Kirsten Tocchini

School of Nursing and Health Professions, University of San Francisco, 2130 Fulton Street, San Francisco,

CA 94901, USA; rjjones2@usfca.edu (R.J.); kntocchini@usfca.edu (K.T.)

* Correspondence: mhansen@usfca.edu; Tel.: +1-014153787577

Academic Editors: Yoshifumi Miyazaki, Hiromitsu Kobayashi, Sin-Ae Park and Chorong Song

Received: 11 June 2017; Accepted: 21 July 2017; Published: 28 July 2017

Abstract: Background: Current literature supports the comprehensive health benefits of exposure

to nature and green environments on human systems. The aim of this state-of-the-art review is to

elucidate empirical research conducted on the physiological and psychological effects of Shinrin-Yoku

(or Forest Bathing) in transcontinental Japan and China. Furthermore, we aim to encourage healthcare

professionals to conduct longitudinal research in Western cultures regarding the clinically therapeutic

effects of Shinrin-Yoku and, for healthcare providers/students to consider practicing Shinrin-Yoku to

decrease undue stress and potential burnout. Methods: A thorough review was conducted to identify

research published with an initial open date range and then narrowing the collection to include

papers published from 2007 to 2017. Electronic databases (PubMed, PubMed Central, CINAHL,

PsycINFO and Scopus) and snowball references were used to cull papers that evaluated the use of

Shinrin-Yoku for various populations in diverse settings. Results: From the 127 papers initially culled

using the Boolean phrases: “Shinrin-yoku” AND/OR “forest bathing” AND/OR “nature therapy”,

64 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this summary review and then divided into

“physiological,” “psychological,” “sensory metrics” and “frameworks” sub-groups. Conclusions:

Human health benefits associated with the immersion in nature continue to be currently researched.

Longitudinal research, conducted worldwide, is needed to produce new evidence of the relationships

associated with Shinrin-Yoku and clinical therapeutic effects. Nature therapy as a health-promotion

method and potential universal health model is implicated for the reduction of reported modern-day

“stress-state” and “technostress.”.

Keywords: Shinrin-Yoku; forest bathing; nature therapy; integrative medicine

1. Introduction

Research conducted in transcontinental Japan and China points to a plethora of positive health

benefits for the human physiological and psychological systems associated with the practice of

Shinrin-Yoku (SY), also known as Forest Bathing FB (FB) [1–3]. SY is a traditional Japanese practice

of immersing oneself in nature by mindfully using all five senses. During the 1980s, SY surfaced

in Japan as a pivotal part of preventive health care and healing in Japanese medicine [4]. The

reported research findings associated with the healing components of SY specifically hones in on

the therapeutic effects on: (1) the immune system function (increase in natural killer cells/cancer

prevention); (2) cardiovascular system (hypertension/coronary artery disease); (3) the respiratory

system (allergies and respiratory disease); (4) depression and anxiety (mood disorders and stress);

(5) mental relaxation (Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) and; (6) human feelings of “awe”

(increase in gratitude and selflessness) [5]. Moreover, various contemporary hypotheses, such as:

Kaplan’s Attention Restorative Hypothesis [6]; Ulrich’s Stress Reduction Hypothesis [7]; and Kellert

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851; doi:10.3390/ijerph14080851

www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

2 of 48

2 of 37

and Wilson’s Biophilia Hypothesis [8] provide support and a lens for the practice of SY and other

forms of nature engagement.

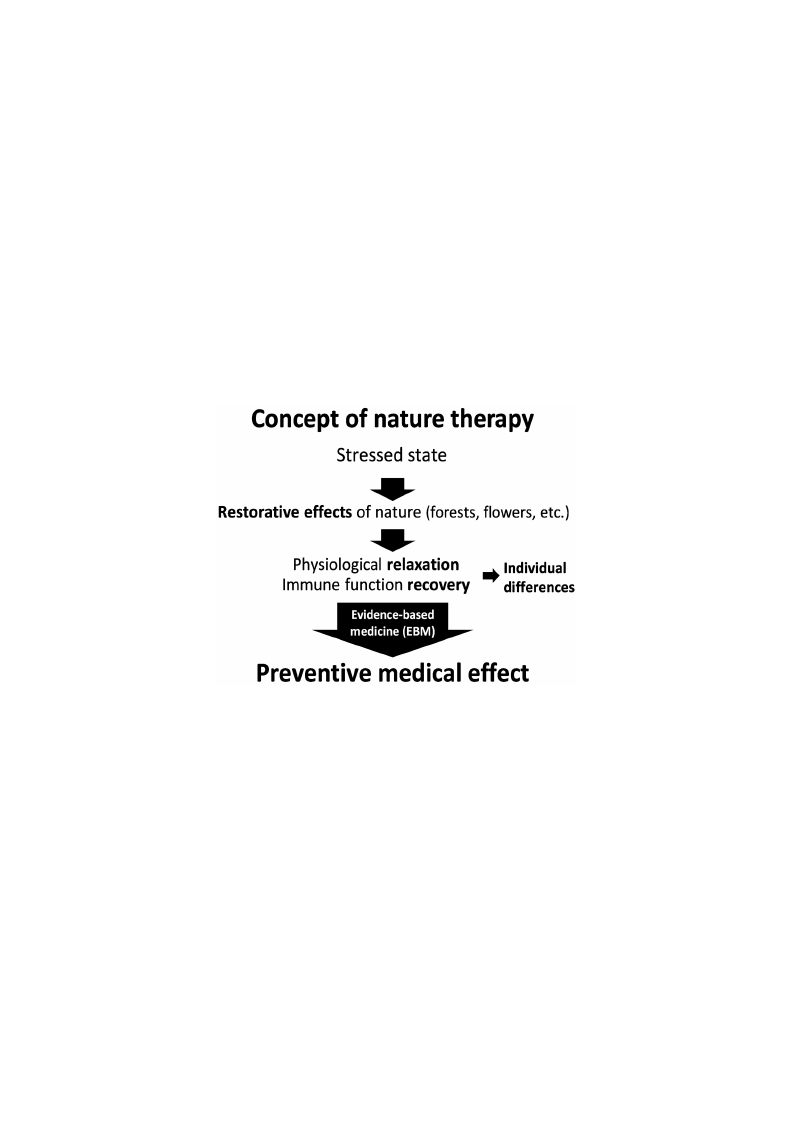

Furthermore, SY may be considered a form of Nature Therapy (NT). Song, Ikei and Miyazaki’s

present day model: Conceepptt of Nature Therapyy (CNNTT)) [9] clearlyy deffiines NT as “a set of practices

aimed aattaacchhieievviningg‘p‘prervevenentitviveemmedeidciaclaelffeefcfetsc’tsth’ rtohuroguhgehxpeoxspuorseutroentaotunraatlusrtaiml sutliimthualit trhenatderernadsetartae

sotfaptehoyfsipohloygsicoalol greiclaxl aretiloanxaatniodnbaonodstbtohoestwtehaekweneeadkeinmemd uimnemfuunnectfiuonncstitonpsrteovepnretvdeinsetadsiesse”as[9es].”T[9h]e.

TcohnecceopntcueapltmuaoldmeloodfelNoTf NstTarsttsarwtsitwhiath“ast“rsetsrseesdsesdtasttea”tea”tatthtehetotpopananddththeennppooininttssttootthhee “restorative

effects” of nature (forests, flflowers, etc.) where there is a hypothesis of iimprovement in “physiological

relaxatioonn”” anandd“im“immumnuenfue nfcutinocntiroencovrecryo”vererysp”onresseps o(innsdeisvid(iunadlivdidffueraelncdeisffneoretendc)e.sThneoste dre).spTohnessees

rtoesnpaotnusrees atroe nthateunreinacroerpthoeranteidncionrpthoreatEevdidienntcheeBEavseiddenMcedBicaisneed(EMBeMdi)cimneod(EelBaMn)dmisodilelul satrnadteids

iblyluastnraatrerdowbyleaandainrrgowto ltehaedi“npgretvoetnhteiv“epmrevedenictaivl eefmfeecdt.i”caTlheifsfecclte.a”rTmhiosdcelleasrupmpoodretsl sSuopnpgo, rItkseSioanngd,

IMkeiyi aznadkMi’siy[a9z]arkeiv’sie[9w] roefviseowmoef smomedeicmaleldyicparlolyvpenroovuentcooumtceos.meKs.aKpalapnlaannadndKKapaplalnan[[66]] associated

with exppoossuurree ttoonnaatuturraallylyooccucurrirninggstsitmimuluil(ia(lal l5l s5ensesnes)est)hatht ahtashasdairedcitreecftfeecftfeocnt ionncrienacsrienagsitnhge

pthaerapsayrmaspyamthpeatitchenteicrvnoeurvsosuysstseymsteamndanadhaeihgehigtehntedneadwaawreanrenssestshtahtaltelaedasdstotoaassttaattee ooff relaxation

(Figure 1).

FFiigguurree 11.. CCoonncceepptt ooff nnaattuurree tthheerraappyy [[99]].. PPeerrmmiissssiioonn ttoo ppuubblliisshh ffrroomm YYoosshhiiffuummii MMiiyyaassaakkii..

wwpyspsoats2JiCfbPashFoaiCShansharptptrrn5nwveveTeuhoheoyrueipeei0seenaaddedeesyynmscmrridoah0acrriirresiseuhesstlttnsnipaalakeosafusSIISliiisiflrsyuiolncnvlnreets-uisniwaeeportclilhncGaeiayxslmdsendttyvvgsmoanrhhoatahseengnacsdeeieieoenoneilbgeeirvShv,hedmicwlrarnsrsipfftst”anaeyiCwtivamaioo.fhrdtcadloGlihhdawiehulol[aihtlwatnByrtnaidtocu5auhyhuoisldgosrpilegiryinent]nnngtuseansmdaswuoauaseaaa.udwxgi-ailcetualgrenncsningpGcsTouidsaertxnttlssitewadatidhdseohtfnahrdwihpinepsltlilhlenraei,,niyynFhksacerriporviasvidehwsehghmootnns”sTeatenesbstiehisaaueieiaapuGadntexcednychfsecanx[teovvihfrsddaihrgegciii5gortnepne1dn.naneeheemvduihhue]Srat5vglxanp.asguaweaBpeeomoomemmids-ispeinn,rnaTtnpmowlnmryhgeieeaelanoPlaaooidenddihcyurdexhyonpllniagdnanirreaechkiudetplrsntverventtiiihrssbsrhseseuiasunuecnthoMeaasicsieuoohdiadiibandsmhntcisritealincnnfftpeoseiiealieehedeuaseaiidlntg1iratanranntdpvdateturllotvaotha5watnrstohsnd,dhepiisuinsllehrcos-euctfn[itnsuelePemeeesotefg3iityphuGslerinvetSiyn[aseipcave]hhnc,ai2neorsnirhen.necosbsSvrraenattbpdasg]elgsehaoelaepu.dhsred.ip,ylnapeigeStctusoatilodieioAihuiaupnhccnyhesaorpnlSnlklnlrffetnleeoeilrtriantagYrnaoMpsmnikvemsaletaagvoegcgpguurtoinaanennawlnifchrbmeeorreeetewbscsfrsrleioedehdaeereatuih,eaa[ipksueglsoerdwet3:tnc/n:ealn,dtGneahaorwCnpntg]tdinadi“twibae:enes.rcpnwSenphrredacueTdfircanssteoSsoo.aenghgetscecslrpnhpietteaumoabllfyoaSfhttfnirsssilnnaieatuneuhrrnoelcYta-l,npeeuootceeslacrbphglnlngraghrneaecrfedfitneaepapshorerfiiaeae/esrstsSscon:nietarwfualuhkger“ratneioYtsrh“nad(oo(edsstrfrueriageetGoGgTsdcoibadpfpeiEehgriedalisnafiisrarnhulSncanSohopercnesr-eeua“gche)noe)racssvsbengawvAslocts[icaeeeehfldaeernstrruini9aavlrtrfsinreeeeleislioitt]orttfglsmiainoencnbatrppshSmheetnaftwisoasodgndetscYhoegnotnilgcolagfgnf”htnimtieerbdrtureaiffsfsucnaoemscmnettae“eetsi,elaoecheofiiponeeaindcindbbn[ra[tnoiuogaresm“rftay1dn1ieioteeeausnstannonnflh0aa0ufvi,wis[omo(etlsifnnstniAgb]9ec]FeiurteHofircstcrn.t.ndcsg]sugbar”iTsereosmr[mCceifCagereat5hassirdodfg)ratsimmatciuaoedyt”t]nunoohgafneenneche.nlb[rrtmdrddaenotmoopa2citudhersHcrrhtattimetr,rerreheairaeredts3tho,eecoornsnhbih-aenylrpiub,seeoennagn9gt.aasdtaeosvteeutmischduns,onpprttnoTshwunhnas1rpstuaeaendcnfiaercye[urhs1yeeecrfclommi5ritiancaci]treormamecaeemrF(hs]coi.itusggcnFilam.finpo,iobeaia1eteafPitoaleeealTtnndthcntinriads6dnlinHhttdtilyvPlaayf)osrnfiitidatedbyi”.eecicilhhetsdtilbcancraln[sr,,rsestrTyJSoepae2eotfracpnrfiCtasfiniiuardcfoawh,cioccertfnniaecp3ofnennieeroiarihlsurheePonea,ndomfieaeddnddsi9ggcrgncemkncexga2,ne1totit,irtoaoaaarc1itisntnuss5nin6iettanenahsrnnclooeloe1hh0ggrttstomolootilaiigsddddd]hhnyyya0eeeecsss-ftfll.,,

Chiba University, Japan, researchers measured oxyhemoglobin levels in the pre-frontal cortexes of

research participants while the participants observed three dracaena plants [11]. Results indicated a

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

3 of 48

and depression [2]. At the Center for Environment, Health, and Field Sciences, Chiba University,

Japan, researchers measured oxyhemoglobin levels in the pre-frontal cortexes of research participants

while the participants observed three dracaena plants [11]. Results indicated a significant increase in

participants’ oxyhemoglobin levels for urban, domestic and workplace foliage effects which directly

demonstrates the health-promotion effects associated with indoor foliage plants on humans [11].

While exploring recent research about the health benefits associated with SY a dearth of scientific

research conducted in Western populations was determined. Therefore, the increasing interest and the

current published significant research findings surrounding the healing benefits related to SY, GS and

the wilderness offers healthcare professionals an opportunity to delve deeper into this complementary

modality for the prevention of disease and to assist with the potential healing of certain existing

conditions in Western cultures. Revealing current research methods and subsequent research outcomes

associated with SY practices may provide researchers, clinicians and students with an intervention that

assists with preventative medicine and evidence-based practice (EBP). Therefore, the aim of this paper

is to offer: (a) an in-depth inquiry of the current literature, (b) invite researchers residing in Western

cultures to design and conduct empirical research regarding the therapeutic benefits associated with

SY and, (c) to encourage healthcare providers/students to consider practicing SY to decrease undue

stress and potential disconnection.

2. Materials and Methods

Review Method

The terms of this comprehensive review were to emphasize the core elements of the research

proposition. The initial literature search was conducted with the intention of identifying publications

that offered significant historic relevance to the practice of SY, included various populations, sample

sizes and geographic locales, utilized evidence-based practices, illustrated measurable physiological

and psychological effect parameters, expounded upon practical frameworks and methodologies for the

practice of SY, explicated unique measurable criteria for the application of SY and deduced limitations

of previous research.

Search Method

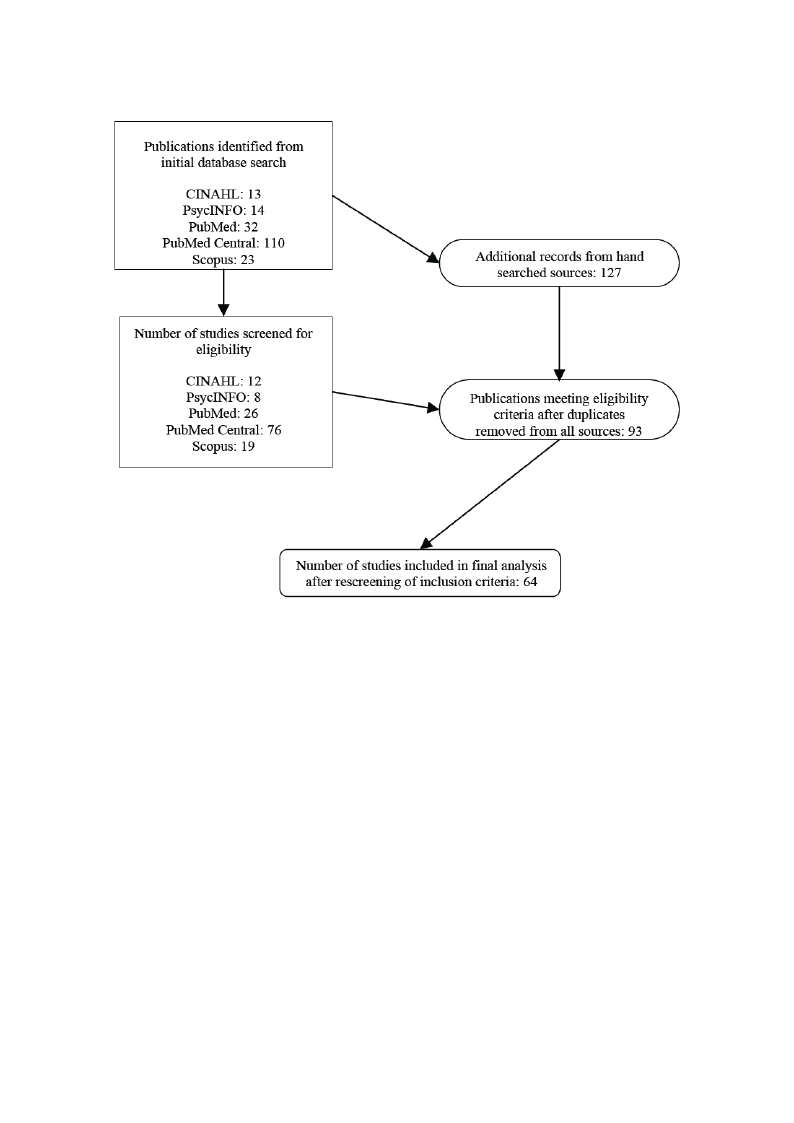

The electronic databases searched included PubMed Central, PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, and

PsycINFO (Figure 2). Hand searched bibliographies and reference lists from seminal researchers of

SY were also applied to the initial culling of publications. PubMed Central was searched to ensure

the incorporation of relevant publications not indexed in PubMed. Keywords were used for each

database and during snowball searches. All titles and abstracts were searched with the following

terms: “shinrin-yoku,” “forest bathing,” and “nature therapy.” These searches were combined with the

Boolean operators AND/OR. These terms were chosen from careful analyses of supporting literature.

For example, the aforementioned terms “nature therapy”, “shinrin-yoku”, and “forest therapy” are

used in conjunction with one another in the most recent scholarly literature review of NT in Japan [9].

To remain prescient, the reference range utilized in this review included literature published

between the years 2007 and 2017. Therefore, the inclusion criteria allowed for publications that were

available in English, dated from 2007 to 2017, incorporated transparent evidence based practices in

reviews or trials, included robust quantitative and/or qualitative data, offered unique frameworks

and theories, and explored current trends in research. Studies not meeting the tenets of this criteria,

specifically those that pertained to physical exercise, fitness, landscape architecture, and laboratory, or

animal studies were withdrawn from considerations.

IInntt.. JJ.. EEnnvviirroonn.. RReess.. PPuubblliicc HHeeaalltthh 22001177,, 1144,, 885511

44 ooff 4387

FFiigguurree 22.. LLiitteerraattuurree sseeaarrcchh pprroocceessss..

3. Results

The fifindings of aallll rreelleevvaanntt ssttuuddiieess wweerree ssyynntthheessiizzeedd ((TTaabbllee 11)).. The initial literature search

revealed a series of topical themes apropos of the research aim. Articles were grouped into categories

reflflecting upon their mmoosstt ppeerrttiinneenntt ffeeaattuurreess.. Thessee categoriess include Background information,

Frameworks, Physiologgiiccaall andd Psychhoollooggiiccaall eeffffeeccttss,, SSeennssoorryy MMeettrriiccss,, aanndd LLiimmiittaattiioonnss ttoo ffiinnddiinnggss..

Previous Systematic Reviews and Literature Reviews were identifified. Characteristics of publications

specifificc ttoo tthhee tthheemmeessooffPPhhyyssiioollooggiiccaallaannddPPssyycchhoolologgiciacal lEEfffefcetcsts(P(PP),)S, eSnesnosroyryMMetertircisc(sS(MSM), )w, whihchichisias

sausbutbotpoipciocfoPfPP,Pa,nadnFdrFamraemweowrkosrk(sF)(Fa)reardeedlienleinateeadte, dan, aenxpexlipcalitceadtewdiwthiitnhitnhethkeeykeiyn iTnabTlaeb1le. 1.

3.1. Physiological and Psychological (PP) Effects

Livni [12] published an editorial on the health benefits of SY and described the historic trends in

biophysical and psychosocial research. While news of the beneficial elements of SY has been

gathering momentum in popular lexicon, it has been the robustness of pioneering research, largely

from Japanese scholars, that illuminates empirical links between the PP effects of SY. Tsunetsugu,

Park and Miyazaki [13] conducted a novel review representing a didactic integration of various

parameters specific to central nervous system (CNS) activity biomarkers; heart-rate variability

(HRV), salivary cortisol levels (SCL), immunoglobulin A (IgA) and sense-specific metrics.

Of the studies included within the PP section, and irrespective of study aims, there was a trend

towards small sample sizes, gender and age homogeneity, and skewed ratios of females to males/vice

versa, which by either methods of convenience, purpose and/or imparted bias to the research. An

overwhelming number of studies included homogenous gender sampling [14–27]. Population

demographics specific to gender were unreported in [28–30]. Proportionately skewed ratios of male

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

5 of 48

Study

Bowler [1]

Chun [2]

Table 1. Characteristics of selected studies and supporting evidence.

Country

UK

Korea

Population

Articles were culled from

PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL,

PsycINFO, Web of Science,

SPORTDiscus, ASSIA, HMIC

Data, LILACS, UK Natl.

Research Register archives,

TRIP database, UK Natl. Lib.

for Health, Index to Theses

Online, Directory of Open

Access Journals, Economic and

Social Data Service, Database

of Promoting Health

Effectiveness Reviews, Trials

Register of Promoting Health

Interventions, Cochrane

Collab., Campbell Collab.

Sample

Article total = 25. Studies that

met the review inclusion

criteria included crossover or

controlled trials, which

investigated the effects of

short-term exposure to each

environment during a walk or

run. Including ‘natural’

environments, such as public

parks and green university

campuses, and synthetic

environments, such as indoor

and outdoor built

environments.

Chronic stroke patients

recruited from a stroke welfare

center in the Republic of Korea.

Of those included: 31 patients

had a history of cerebral

infarcts, and 28 with a history

of intracerebral hemorrhage.

N = 59; 40 men, 19 women; 60.8

± 9.1 years of age with an age

range of 36–79 years.

Setting

Centre for Evidence-Based

Conservation at the School of

the Environment and Natural

Resources, Bangor University,

Bangor, Gwynedd, United

Kingdom.

Settings included a recreational

forest area in Gyenggi-do,

Republic of Korea. The urban

group stayed in a hotel

Gyenggi-do in the Republic of

Korea.

Aim & Design

Systematic review to collate

and synthesize the findings of

studies that compare

measurements of health or

well-being in natural and

synthetic environments. Effect

sizes of the differences between

environments were calculated

and meta-analysis used to

synthesize data from studies

measuring similar outcomes.

PP

Assessment of forest therapy

effectiveness for treating

depression and anxiety in

patients with chronic stroke by

using psychological tests. This

study measured reactive

oxygen metabolite (d-ROM)

levels and biological

antioxidant (BAPs) potentials

associated with psychological

stress. Patients were randomly

assigned to a forest group

(recreational forest site) or

urban group (staying in an

urban hotel). Scores on Beck’s

Depression Inventory,

Hamilton Depression Scale,

and the Spielberger State Trait

Anxiety Inventory were

analyzed.

PP

Findings

The studies suggested that

natural environments may

have direct and positive

impacts on several aspects of

health and well-being.

Forest groups had BDI,

HAm-D17 and STAI scores

were significantly lower

following treatment. BAPs

were significantly higher than

baseline. Urban group STI

scores were significantly higher

following treatment. Forest

therapy is beneficial for

treating depression and anxiety

symptoms in patients with

chronic stroke and may be

useful in patients who can’t be

treated by standard

pharmacological or

electroconvulsive therapies.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

6 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Han [3]

Anonymous

[4]

Williams [5]

Kaplan [6]

Ulrich [7]

Kellert [8]

Song [9]

Country

Korea

Japan

Population

Sample

Employees of a public

organization providing

building and facilities

management services in Seoul

Metro area, all of whom were

diagnosed with Chronic

Widespread Pain (CWP).

N = 61; 35 females and 26

males; randomly assigned to

the either the experimental

forest therapy group (n = 33),

or the control group (n = 28).

Supporting material

NA

Supporting material

NA

Supporting material

NA

Supporting material

NA

Supporting material

NA

Researchers culled articles

from the Pubmed database

using various keywords.

Article total: 52

Setting

Forest therapy intervention

took place at a campsite at the

Saneum Natural Recreation

Forest in Yangpyeong county

of Gyeonggi Province.

Additional assessments were

taken at the Inje University

Seoul Paik Hospital in the

urban environment.

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

Aim & Design

To explore the effects of a 2-day

forest therapy program on

those with chronic widespread

pain.

Measures assessed included

the following: pre- post heart

rate variability, natural killer

cell, self-reported pain,

depression level and health

related quality of life.

PP

Shinrin Yoku. A website

describing the practice of SY

and programs offered for forest

guide training.

An article presented in the

National Geographic magazine

about the effects of NT.

A book about Kaplan’s

Attention Restorative

Hypothesis.

An article about Ulrich’s Stress

Reduction Hypothesis.

A book explaining the

Biophilia Hypothesis.

Literature review aimed to

objectively demonstrate the

physiological effects of NT.

Reviewed research findings in

Japan related to the green

space, plants and wooden

material and the analysis of

differences that arise therein.

PP

Findings

Forest therapy participants

reported significant decreases

in pain, depression and

increased QOL. Forest therapy

is an effective intervention to

relieve psychological and

physiological pain.

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

Researchers elucidated various

scientific data, which assessed

physiological indicators, such

as brain activity, autonomic

nervous activity, endocrine

activity, immune activity are

accumulating from the field

and lab experiments. NT will

play a significant role in

preventative medicine in

the future.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

7 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Sifferlin [10]

Igarashi [11]

Livni [12]

Country

Japan

Population

Supporting material

Female students from the

University of Chiba, Japan,

deemed healthy at the time of

the study.

Supporting material

Sample

NA

Setting

NA

N = 18; adult female university

students with a mean age of

21.6 ± 1.5 years.

Artificial climate chamber in a

laboratory of the Center for

Environment, Health, and

Field Sciences, Chiba

University, Japan.

NA

NA

Aim & Design

Findings

A Time magazine article about

the effects of living and

interacting in green spaces.

Results indicate people are

more energetic, in good overall

NA

health and have more of a

sense of meaningful purpose

in life.

Quantitative study was to

determine if images of natural

objects elicited similar neural

responses (activation of the

prefrontal cortex) as those

brought about with the

interaction of real objects.

Physiological measurements

were performed in an artificial

climate chamber maintained at

25 ◦C with 50% relative

humidity and 300 lux

illumination. For foliage plants

three dracaena plants (Dracaena

deremensis) were used.

Oxy-hemoglobin

concentrations in the prefrontal

cortex were assessed with

time-resolved near-infrared

spectroscopy.

SM

Subjects viewing actual live

plants had significantly

increased oxy-hemoglobin

concentrations in the prefrontal

cortex. Subjective ratings of

“comfortable vs.

uncomfortable” and “relaxed

vs. awakening” were similar

for both live and artificial

plants. Results were significant

for the benefits for urban,

domestic and

workplace foliage.

The Japanese practice of ‘Forest

Bathing’ as scientifically

NA

proven to improve your health.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

8 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Tsunetsugu

[13]

Jo [14]

Country

Population

Japan

N/A

Japan

Participants comprised

Japanese male graduate and

undergraduate students at

Chiba University, recruited

from landscape and

horticulture programs.

Sample

Author-researchers culled

articles for this literature

review from a studies rooted in

physiological data, data

collected from field

experiments in forest settings,

laboratory settings, and studies

categorized into sub-themes

specific to the five-senses.

Exact literature search

methodology and total number

of articles culled unknown.

N = 26; males aged early to

mid- twenties mean age 24 ±

1.8 years.

Setting

N/A

Chiba University in a screened

room, such that the

participants were blinded to

the observers.

Aim & Design

To investigate the physiological

effects of Shinrin-yoku

according to specific themes

centered on the health

applications of FB. The authors

reviewed previous

physiological experiments with

trials in forests and laboratory

settings, to determine the

physiological effects on

individuals from exposure to

forests and elements of forest

settings. Metrics investigated

included: physiological

measurements of central

nervous activity, autonomic

nervous activity, and

biomarkers reflecting stress

response.

PP

Quantitative. Controlled trial

without randomization. The

aim of this study was to

elucidate how floral fragrance

could impact human health;

specifically, the

psycho-physiological

responses to the floral scent of

the Japanese plum blossom.

Changes in cerebral activity

were measured by

multichannel near-infrared

spectroscopy. Pulse rate,

heart-rate variability and

arterial blood pressure were

taken. The brief-form Japanese

version Profile of Mood States

questionnaire (POMS) tested

for psychological stress.

SM

Findings

Author-researchers

summarized the separate

elements of forests in terms of

the five senses, and provide

contribution to effects of

Shinrin-yoku within the

framework of the “Therapeutic

Effects of Forests” project.

Sensory stimuli from plants

may reduce stress and provide

a general sense of wellbeing

among this population.

Hypothesis was supported by

the data.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

9 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Igarashi [15]

Ikei [16]

Country

Japan

Japan

Population

Sample

Setting

Seventeen Japanese adult

females were recruited from a

population living within the

urban suburbs of Kashiwa in

the Chiba Prefecture of Japan.

All were deemed healthy prior

to the experiment.

N = 17; Adult Japanese females

with a mean age of 46.1 ± 8.2

years.

Kiwifruit orchard adjacent to

the Center for Environment,

Health and Field Sciences,

Chiba University, Japan.

Female students from the

University of Chiba, Japan,

deemed healthy at the time of

the study.

N = 13; adult female university Center for Environment,

students with a mean age of

Health and Field Sciences,

21.5 ± 1.0 years.

Chiba University, Japan.

Aim & Design

Physiological and

psychological relaxation effects

of viewing kiwifruit orchard

landscapes in summertime in

Japan were investigated.

Quantitative, randomized

controlled trial wherein

subjects viewed a kiwifruit

orchard landscape or a

building site (control) for 10

min. Intervals. HRV and HR

were measured continuously.

Modified semantic differential

method and short-form Profile

of Mood States (POMS) were

determined.

SM

Quantitative controlled trial

without randomization was to

determine the effects of

olfactory-stimulation of the

alpha-pinene (a volatile

compound in Japanese cedar

wood) on autonomic and

parasympathetic nervous

system activity. Measures were

taken at 30 s before and 90 s

during/after smell admin.

HRV and HR were measured.

HR

SM

Findings

Significant increase in PNS

activity and marginally

significant decrease in HR and

an increase in comfortable,

relaxed and natural feelings

and a significant improvement

in mood states.

Olfactory stimulation by

a-pinene significantly

increased the High Frequency

measure of HRV, which is

associated with

parasympathetic nervous

activity, and decreased HR

overall—these are signs of

increased physiologic

relaxation.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

10 of 48

Study

Kobayashi

[17]

Kobayashi

[18]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Japan

Japan

Population

Sample

The study consisted of 456

Japanese male students at the

University of Chiba, Japan,

deemed healthy at the time of

the study.

N = 456; Males aged 20 to 29

years old (mean,

21.9 ± 1.6 years).

The population consisted of in

267 male students from The

University of Chiba, Japan,

deemed healthy at the time of

the study.

N = 267: Males with a mean

age of 21.7 ± 1.5 years.

Setting

Experimental design and

procedures took place at the

Forestry and Forest Products

Research Institute and Center

for Environment, Health and

Field Sciences, Chiba

University, Japan.

Chiba University’s research

labs and additional laboratory

studies performed at the

laboratories of SRL Inc. in

Tokyo, Japan.

Aim & Design

Findings

To deduce and present the

“normative values,” or

“reference” range of heart rate

variability (measured in 417

young male students), and

salivary alpha-amylase in 430

“healthy” male students from

Chiba University with an

emphasis on the distribution

and reproducibility of the

values. Measures within this

quantitative study included:

short-term HRV; beat to beat

HR recorded at 2 min intervals

with portable/wearable HR

monitor Salivary

alpha-amylase measurements

taken before breakfast (6:30 to

7:30 a.m.) after subjects sat

“resting” 1 min.

PP

Results suggested a relatively

small correlation between HRV

and salivary alpha-amylase.

This study is mostly indicative

of intra-individual variability

in measures. Provides example

of metrics we can use in our

study as well as

“normative” values.

Quantitative study aimed to

specify the normal salivary

cortisol levels, and reference

ranges in subjects at University

of Chiba, as a relatively

innocuous biomarker for stress

levels during the mornings on

two consecutive days, which

were analyzed by

radioimmunoassay.

Quantitative. Saliva collected

before breakfast, appx.

20–40 min after awakening

(6:30–7:30 a.m.) and again

before participants brushed

teeth. Each subject rested for

1 min in a sitting position

before saliva collection.

Measures were repeated the

following day.

PP

Consistency and reliability

(“distribution characteristics”)

of salivary cortisol measures

were reported to be steadier in

the morning samples

~30–45 min after waking.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

11 of 48

Study

Koga [19]

Lee [20]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Japan

Japan

Population

Sample

Setting

Japanese male students from

The University of Chiba were

recruited for this study.

N = 14; Males with an age

range of 21–27 years.

Laboratory rooms at The

University of Chiba, Japan.

Male students from the

University of Chiba, Japan.

N = 24; Japanese males with a

mean age of 24.9 ± 2.1.

Settings included laboratory

rooms at The University of

Chiba, Japan.

Aim & Design

Quasi-experimental study was

to gauge the feeling elicited by

(with eyes closed), touching

four different “tactile” samples:

a plate of aluminum, a piece of

velveteen, leaf of natural

Epipremnum aureum, and an

artificial resin-made leaf, for

about ~120 s. Measures

included pre and posttest

psychological and

physiological indices, Cerebral

Blood Flow (hemodynamics)

measured via near infrared

spectroscopy (NIRS; NIRO-300;

Hamamatsu Photonics,

JAPAN); measured pre and

post stimulus. Psychological

data were acquired using a

semantic differential

questionnaire.

SM

To examine the psychological

and physiological benefits of

interaction with indoor plants

vs. computer tasks.

Researchers implemented a

quantitative crossover

experimental design.

Participants were randomly

distributed into 2 groups

(n = 12 plants; n = 12

computer task).

PP

Findings

Participants successfully

reported feeling a measurable

sense of “calm” when touching

natural plant material, as

opposed to the other materials

Feelings during the

transplanting task were

different from that during the

computer task. Feeling more

comfortable, soothed, and

natural after the transplanting

task Sympathetic activity

increased over time during the

computer task but decreased at

the end of the transplanting

task. Diastolic BP lower after

transplanting task.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

12 of 48

Study

Lee [21]

Lee [22]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Japan

Japan

Population

Sample

Twelve young Japanese male

adults were recruited from

local universities. At the

recruitment stage, those who

had past or current mental

disorders, and those with

cardiovascular or allergic

diseases were screened. Those

who were habituated to

smoking or drinking were

excluded. The adults who

participated in the study had a

mean age of 21.2 years

[standard deviation (SD) 0.9].

N = 12; Japanese males with a

mean age of 21.

Male students ages 21–22 at

Chiba University in Japan were

recruited to participate in the

walking programs. All were

deemed healthy at the outset of

the trials.

N = Japanese males with a

mean age of 21.1 ± 1.2 years.

Setting

Field experiments were

performed at two different

sites (forest and urban) in

Hokkaido Prefecture, Japan.

The forest site was

characterized by broad-leaved

deciduous trees and was

located in Tsurui Village. The

urban site was a typical

commercial area situated in the

town of Kushiro.

Field experiments were

performed at four different

sites in Japan including:

Yoshino Town in Nara

Prefecture, Akiota Town in

Hiroshima Prefecture,

Kamiichi Town in Toyama

Prefecture, and Oita City in

Oita Prefecture. Data analysis

performed at The University of

Chiba, Japan.

Aim & Design

To provide scientific evidence

supporting the efficacy of FB as

a natural therapy by

investigating its physiological

benefits using biological

indicators in outdoor settings.

3 days 2-night study.

Physiological responses as well

as self-reported psychological

responses to forest and urban

environmental stimuli were

measured in real settings.

PP

Quasi-experimental study

aimed to compare the effects of

a forest walking therapy

program with an Urban

walking program over 2

consecutive days to determine

the cardiovascular relaxation

indices. Walks included

12–15 min of self-paced

walking in forest (4 sites

selected throughout Japan) and

urban (the control)

environments. HRV measured

with a portable ECG w/in

1 min intervals. 4 psychological

questionnaires delivered:

semantic differential (SD)

techniques. Japanese version of

the Profile of Mood States

(POMS). Anxiety levels studies

with Spielberger State-Trait

Anxiety Inventory (STAI).

PP

Findings

Results of each indicator were

compared against each

environmental stimulus. HF

power analysis, which reflects

the activity of the

parasympathetic nervous

system, significantly higher

values were obtained for forest

stimuli than urban stimuli.

Additionally, LF/HF ratio

values of HRV, which mediate

the activity of the sympathetic

nervous system, were

significantly lower in the forest

than at the urban site.

Cardiovascular relaxation was

noted with the forest walking

therapy program, but not as

with the urban control

-specifically the differences in

HRV and BP within the two

exposures. Psychological tests

are concurrent with these

findings.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

13 of 48

Study

Li [23]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Japan

Population

Male adult subjects were

selected from four large

companies in Tokyo, Japan.

Subjects having infectious

disease, utilizing

immunosuppressive drugs

and/or other relevant

medications were ruled out.

Subjects were deemed healthy

at the time of the trial.

Sample

N = 12; Males aged 35–56 years,

with a mean age of 45.1 ± 6.7.

Setting

Various forested and urban

locations across Japan.

Specifically, the FB groups

experienced three different

forest areas in Agematsu town

in Nagano prefecture of

northwest Japan. Whereas the

city group experienced Nagoya

city located in Aichi prefecture

in the center of Japan.

Aim & Design

To study NK activity in both

forest and urban environments.

Twelve healthy male subjects,

age 35–56 years, experienced a

three-day/two-night trip to

forest fields and to a city, in

which activity levels during

both trips were matched. On

day 1, subjects walked for two

hours in the afternoon in a

forest field; and on day 2, they

walked for two hours in the

morning and afternoon,

respectively, in two different

forest fields; and on day 3, the

subjects finished the trip and

returned to Tokyo after

drawing blood samples and

completing the questionnaire.

Blood and urine were sampled

on the second and third days

during the trips, and on days 7

and 30 after the trip, and NK

activity, numbers of NK and T

cells, and granulysin, perforin,

and granzymes A/B

expressing lymphocytes in the

blood samples, and the

concentration of adrenaline in

urine were measured. Similar

measurements were made

before the trips on a normal

working day as the control.

PP

Findings

Phytoncide concentrations in

forest and city air were

measured. The FB trip

significantly increased NK

activity and the numbers of

NK, perforin, granulysin, and

granzyme AlB-expressing cells

and significantly decreased the

concentration of adrenaline in

urine. The increased NK

activity lasted for more than 7

days after the trip. In contrast,

a city tourist visit did not

increase NK activity, numbers

of NK cells, nor the expression

of selected intracellular

anti-cancer proteins, and did

not decrease the concentration

of adrenaline in urine.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

14 of 48

Study

Mao [24]

Ochiai [25]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

China

Japan

Population

Male University students

deemed healthy at the time of

the trials without documented

history of physiological or

psychiatric disease and/or

disorder.

Participants included those

recruited from the Health

Promotion Center in

Agematsu, Nagano Prefecture.

All participants needed to be

Inclusion aged 40 years or

older and deemed healthy at

the time of the study.

Sample

N = 20; Male age

20.79 ± 0.54 years.

N = 17 Female adults with an

average age of 62.2 ± 9.4 years.

Setting

Locations included the Wuchao

Mountain Forest in Hangzhou,

Zhejiang, China and the urban,

downtown district of

Hangzhou, China.

Forest therapy phase was

conducted in Akasawa Shizen

Kyuyourin, Akasawa Natural

Recreation Forest, Agematsu,

Nagano Prefecture. Additional

assessment took place at the

nearby health promotion

center.

Aim & Design

Quantitative randomized

controlled trial was to measure

the effects of forest-bathing for

short periods of time on overall

human health using a variety

of metrics. To investigate

potentially positive effects of

FB on the subject’s health from

the standpoint of

pathophysiological metrics.

Subjects were randomly

divided into two groups.

Forest site and city site.

Measures included:

malondialdehyde (MDA)

concentrations, cytokine

production, serum cortisol,

testosterone assay, lymphocyte

assay, POMS evaluations.

PP

To assess the psychological and

physiological effects of a forest

therapy program on middle

age adult women. Measures

included pulse rate, salivary

cortisol levels and

psychological indices were

taken the day before and the

day of forest therapy.

PP

Findings

Data supported the hypothesis

that several physiological and

psychological metrics were

presented in accordance with a

decrease in overall stress and

subsequent toxic physiologic

effects of stress.

Pulse rate, salivary cortisol

levels were significantly lower

than baseline indicating a

physiological relaxed state.

Reported significantly more

comfortable, relaxed and

natural according to the

semantic differential. POMS

negative mood subscale for

tension and anxiety was

significantly lower while the

“vigor” was significantly

higher following forest therapy.

A significant decrease in pulse,

decrease in salivary cortisol

levels, increase in positive

feelings, decrease in negative

feelings. Substantial benefit to

middle age females.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

15 of 48

Study

Park [26]

Park [27]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Japan

Japan

Population

Participants included young

male Japanese university

students.

Male University students

recruited from Chiba

University, Japan.

Sample

N = 168 Male (100%), mean age

20.4 ± 4.1 years

N = 12; Males with an average

age of 22.8 ± 1.4 years.

Setting

14 forests and 14 urban areas

across Japan

The experimental trials took

place in a Seiwa Prefectural

Forest Park in Chiba Prefecture,

Japan.

Aim & Design

To investigate the relationships

between psychological

responses and either an urban

or a forest setting. Using both

the SD method and POMS

questionnaire, comparisons

were made for both the

walking and viewing phases

within each area of

accommodation.

PP

To investigate the physiological

effects of Shinrin-yoku using

salivary cortisol and cerebral

activity as indicators. On the

first day of the experiment, one

group of 6 subjects was sent to

a forest area, the other 6 were

sent to a city area. On the

second day, each group was

sent to the opposite area for a

cross check. In the morning,

the subjects were asked to walk

around their location for 20

min. In the afternoon, they

were asked to sit on chairs and

watch the landscapes of their

set locale for 20 min. Prefrontal

cortical cerebral activity and

salivary cortisol were

measured before and after

walking in the forest, or city

locations and before and after

watching the landscapes in the

afternoon in the forest and city

areas.

PP

Findings

Researchers found that

descriptions of the forest area

using the SD method were

more “enjoyable, friendly,

natural, and sacred”. There

were also significant

differences among POMS

results for both the city and

forest areas.

Results indicated that cerebral

activity in the prefrontal area of

the forest area group was

significantly lower than that of

the group in the city area after

walking; the concentration of

salivary cortisol in the forest

area group was significantly

lower than that of the group in

the city area before and after

watching each landscape. The

results of the physiological

measurements show that

Shinrin-yoku can effectively

relax both people’s body and

spirit.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

16 of 48

Study

Joung [28]

Mao [29]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Korea

China

Population

Sample

Setting

Eight Korean university

students participated in this

study. The subjects were

deemed physically and

mentally healthy prior to the

initiation of this study.

N = 8; Participants had an age

range of 22.0 ± 2.2 years.

Gender undocumented.

Forested-region located in

Dowon-ri, Toseong-myun,

Goseong-gun, Gangwon-do,

Korea. The contrasting urban

area was in Yuseong-gu,

Daejeon Metropolitan City,

Korea.

Subjects included patients

diagnosed with essential

hypertension in stable

condition at the time of the

study. All were being treated in

Hangzhou, China.

N = 24; Adults, aged from 60 to

75 years, specific

demographics unknown.

Broad-leaved evergreen forest

“White Horse Mountain

National Forest Park” in

Suichang, County, Zhejiang

Province, China. For

comparison, the control city

was an urban area in

Hangzhou, China.

Aim & Design

Determine if forest

environments have

physiological and

psychological relaxing effects

by viewing a forest area

compared with viewing an

urban area from the roof of an

urban building without being

watched by others.

Near-infrared spectroscopy

measurement was performed

on subjects while they viewed

scenery for 15 min. At each

experimental site (forest and

urban) Total hgb and

oxyhemoglobin concentrations

were measured.

SM

Quantitative randomized

controlled trial was to provide

scientific evidence to support

the use and efficacy of SY as a

practical application for

treating, or ameliorating

essential hypertension in the

elderly. Patients with essential

hypertension were randomly

divided into a field study

group and a control group of

12 persons each. The

intervention (field study)

group went to a broad-leaved

evergreen forest to experience

a 7-day/7-night trip, and the

control group experienced a

city area in Hangzhou for

control. Measurements of the

following were collected:

blood pressure indicators,

cardiovascular disease-related

pathological factors including

endothelin-1,

Findings

Total hgb and oxyhemoglobin

concentrations were

significantly lower in their

forest area than the urban area.

Comfortable, natural, and

soothed were significantly

higher in the forest vs. urban

area.

For mood states, the forest

group had significantly lower

negative emotions.

Results of this study

demonstrated that there is

direct evidence to support the

application of SY for the

amelioration of essential

hypertension in the population

studied. Data indicates that SY

practices contribute to the

inhibition of the

renin–angiotensin system and

inflammation, thereby

reducing cardiac workload and

further stress on the heart

when compared with the urban

control.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

17 of 48

Study

McCaffrey

[30]

Country

Population

Sample

Table 1. Cont.

Setting

USA

Participants included older

adults over the age of 65 with

depression.

N = 40 (mean age = 71.3 years)

with depression diagnosed by

a physician.

Morikami Gardens, Florida

Aim & Design

Findings

homocysteine, renin,

angiotensinogen, angiotensin

II, angiotensin II type 1

receptor, angiotensin II type 2

receptor, inflammatory

cytokines interleukin-6 and

tumor necrosis factor were

detected. The profile of mood

states (POMS) was used for

psychological indicators.

PP

To determine the effects of

garden walking on depression

in older adults. Participants

were asked to complete 12 two-

hour garden walks during a

3-month period. Throughout

the walks, they were asked to

read a descriptive paragraph

and journal upon reaching

specified locations within the

gardens. Pictures of these

locations were also provided so

that journaling could continue

when the participants were

away from the gardens as well.

PP

Mean scores on the Geriatric

Depression Scale decreased

from 13 to 9.4 after completion

of the 12 forest walks.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

18 of 48

Study

Kim [31]

Morita [32]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Korea

Japan

Population

Patients recruited for this study

were among a population

diagnosed with major

depressive disorder at one

university hospital located in

Seoul, Republic of Korea.

71 healthy adult volunteers

participated in this study. Ages

ranged from teens to late 70s.

Sample

N = 63 males and females; 23 in

the forest group, 19 in the

hospital group, and 21 in the

control group.

N = 71; 43 males and

28 females.

Setting

Settings were the following;

the forest program took place

at the Hong-Reung arboretum,

while the hospital program

took place at the Seoul Paik

Hospital.

Ryukoku Forest of Ryukoku

University in Shiga Prefecture,

located in the western region of

Honshu, Japan. Data analysis

took place at the University of

Shiga, Japan.

Aim & Design

To test the effect of cognitive

behavior therapy (CBT)-based

psychotherapy applied in a

forest environment on major

depressive disorder. Tests used

included the Hamilton Rating

Scales for Depression (HRSD)

scores of the forest group were

significantly decreased after 4

sessions compared with

controls. Montgomery-Asberg

Depression Rating Scales

(MADRS) scores of the forest

group were significantly

decreased compared with both

the hospital group and the

controls. The remission rate (7

and below in HRSD) of the

forest group was 61% (14/23),

significantly higher than both

the hospital group (21%, 4/19)

and the controls (5%, 1/21).

PP

Pre and posttest study was to

evaluate the immediate effects

of forest walking in a

community-based population

with sleep complaints.

Two-hour forest-walking

sessions were conducted on 8

different weekend days. Sleep

conditions were compared

between the nights before and

after walking in a forest by

self-administered

questionnaire and actigraphy

data.

PP

Findings

CBT-based psychotherapy

applied in the forest

environment was helpful in the

achievement of depression

remission, and its effect was

superior to that of

psychotherapy performed in

the hospital and the usual

outpatient management.

Results indicated that 2 h of

forest walking improved sleep

characteristics; impacting

actual sleep time, immobile

minutes, self-rated depth of

sleep, and sleep quality.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

19 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Nakau [33]

Ohtsuka [34]

Country

Japan

Japan

Population

Patients were recruited from a

pool of cancer patients,

specifically those with breast

cancer, or lung cancer of

various stages. For all

participants, one month passed

after they had undergone

surgery, chemotherapy, or

radiation and were in stable

condition at the time of study.

All participants resided in

urban areas and lacked access

to green, outdoor

environments.

Researchers culled their

participants from a sample of

patients being treated for Type

II Diabetes with an age range

of 60–83, mean height 154.0 cm

± 1.3, and mean body mass

index (BMI) of 23.6 ± 0.4

kg/m2. Additionally,

researchers incorporated data

from longitudinal studies

addressing Type II Diabetic

patients over a period of 6

years. This increased the

sample to 116 persons, from

which 25 paired samples were

studied. Healthy subjects were

used as a control.

Sample

N = 22; Men and women with

a mean age of 58.1 years +/10.8

years. Participants included 4

males with an average age of

65.3 and 18 females with an

average age of 56.6 years.

N = 48 (16 males and 32 female)

Type 2 Diabetic patients with a

mean age of 66.8 years.

Setting

Within the Kyoto prefecture of

Japan, sites included: The

Japan World Exposition 70

Commemorative Park (Suita,

Osaka Pref, Japan), parks,

forests, and gardens within the

park, horticultural settings,

participants’ homes, and a

local day treatment facility.

While watching a yoga video.

Research facility and nearby

recreational areas in connection

with Hokkaido University,

Japan.

Aim & Design

To explore the impacts of

spiritual care and integration

of the natural environments in

terms of its’ impact on 22

cancer patients. Specifically,

the integrative treatment

protocol consisted of forest

therapy, horticultural therapy,

yoga meditation, and support

group therapy sessions were

conducted once a week for 12

weeks. The spirituality (the

Functional Assessment of

Chronic Illness

Therapy-Spiritual well-being),

quality of life (Short Form-36

Health Survey Questionnaire),

fatigue (Cancer Fatigue Scale),

psychological state (Profile of

Mood States, short form, and

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory)

and natural killer cell activity

were metrics assessed before

and after the sessions.

PP

Quantitative longitudinal

study aimed to address the

effects of Shinrin-Yoku on

blood glucose levels in patients

with Type II Diabetes. In an

effort to summarize data from

future studies, the author of

this article noted that an

additional sample of 116

persons, organized into 25

paired groups were

incorporated. Available data

reflects these additional

participants.

Of the initial sample (N = 48),

Findings

There were dramatic shifts pre

and post intervention to

support the hypothesis

aforementioned. Emotional

and spiritual health improved

for all participants. This study

helps to delineate what is

meant by “spiritual well-being”

with specific questionnaires

from which we can glean much

in terms of semantics.

Results demonstrated that

Shinrin-yoku and a decrease in

blood glucose are significantly

correlated. However, due to

the additional longitudinal

participant sample being

reported in the data, the

specificities of the total

population are unclear.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

20 of 48

Study

Shin [35]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Population

Sample

Korea

Subjects were adult males and

females diagnosed with

alcoholism and coming from

treatment at the Korean

Alcohol Research Center,

Chungbuk Province, South

Korea. The Korean Alcohol

Research Center is a national

inpatient alcohol

rehabilitation facility.

N = 92; Adults 84 males, 8

females, aged ~44–49 yeas.

Setting

Saneum Recreational Forest, in

Kyungggi Province,

South Korea.

Aim & Design

Findings

11 participants experienced

only dietary and exercise

therapy, 27 were given oral

medication, and 10 were being

treated with insulin

administration at the time of,

and during the study.

Pre and posttest measures of

blood glucose were taken at

specific timed intervals during

the intervention process.

Participants were assessed after

morning meals at the research

hospital. Peripheral venous

blood samples were collected

for glucose levels. Participants

were divided into two

forest-walking groups. Glucose

samples were drawn again

post Shinrin-yoku treatment.

PP

Quantitative

case-control/cohort study with

pretest vs. posttest assessments.

Subjects were assessed over

9-day while in a forest healing

camp in Saneum Recreational

Forest, in Kyungggi Province,

South Korea, for the

determining this therapy’s

potential treatment of

depression for alcoholics.

Measures included The Beck

Depression Inventory (BDI),

and a self-reported survey of

21 items relating to personal

variables and lifestyle metrics.

PP

Alcoholics with higher pre-test

depression levels improved on

the BDI post-test scores upon

completion of the forest

program more than

participants with lower pre-test

depression levels. Education

level and marital status of

participants did not

significantly influence results.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

21 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Stigsdotter

[36]

Park [37]

Country

Denmark

Japan

Population

Initial sampling of data from

21,832 adults from Denmark

was used for this study. The

sample came from a 2005

nationally administered health

interview survey employing

region-stratified random

sampling from the Danish Civil

Registration

System. 10,250 individuals

responded and their data

recorded for this study.

Male students from the Chiba

University, Japan.

Sample

N = 10,250; Adult Danes aged

16–75 years, 5802 men and

5448 women.

N = 12; Male (100%), mean age

21.8 ± 0.8

Setting

Utilized data from a previous

study taking place across

various regions of Denmark by

The Danish National Institute

of Public Health, University of

Southern Denmark.

Conifer forest in Hinokage

Town , and Hyuga City in

Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan

Aim & Design

Case study of pre-existing data.

The aim of this study was to

research and determine the

relevant associations between

access to green-space, health,

health-related quality of life

indicators, and stress. Data

was collected from respondents

following up of a 2005 Danish

Health Interview Survey. The

data was collected from

face-to-face interviews and

self-administered

questionnaires. Measures

analyzed included: the SF-36,

(measuring eight dimensions

of health) and the Perceived

Stress Scale. Multiple logistic

regression analyses were used

to determine the association

between distance to green

space and self-perceptions

stress.

PP

Quantitative randomized

controlled trial forest recreation

and its effects on the

autonomic nervous system

were assessed. By random

assignment, two groups were

formed into forest-area and

urban-area groups. Measures

included heart rate and

heart-rate variability. The R-R

interval of the

electrocardiogram was used to

analyze how aspects of HRV

reflect the parasympathetic

nervous activity sympathetic

nervous activity respectively.

Pulse rate a blood pressure

were also measured. PP

Findings

Results of this study

demonstrate that Danish

individuals living more than 1

km from green-space reported

lower satisfaction of perceived

health and quality of life than

those living less than 1 km to

accessible green-space.

Additionally, persons living

less than 1 km from a

green-space experienced less

stress than respondents living

farther from green-space.

Respondents who didn’t report

stress were reported to be more

likely to visit green-spaces than

respondents reporting stress.

Overall, there was a viable

association between distance to

green-spaces and the health-

oriented variables in the

research question.

Pulse rate, diastolic blood

pressure and LF/(LF + HF)

(LF—low frequency, HF—high

frequency) components of HRV

were significantly lower in the

forest area than in the city area.

HF components of HRV tended

to be higher in the forest than

in the city. Forest recreation is

effective for relaxation of both

the mind and body.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

22 of 48

Study

Park [38]

Song [39]

Table 1. Cont.

Country

Japan

Japan

Population

Participants included young

male Japanese university

students.

Male students from the Chiba

University, Japan.

Sample

N = 12; Male (100%), mean age

21.3 ± 1.1

N = 23; Male (100%), mean age

22.3 ± 1.2

Setting

Areas of study included

Shinano town and Nagano city

in Nagano Prefecture.

Kashiwa-no-ha Park in

Kashiwa City, Chiba Prefecture,

Japan, with a nearby city area

denoted as the urban control

site.

Aim & Design

To determine the physiological

effects of SY. Day one of the

experiment required that six

subjects went to the forest area,

and the other six went to a city

area. On the second day,

subjects went to the opposite of

their previously assigned areas.

During the morning and

evening within the area of

accommodation, heart rate

variability (HRV), salivary

cortisol and pulse rate were

measured, In the afternoon,

they were seated on chairs

watching the landscapes of

their given area for 15 min. The

aforementioned physiological

indices were again measured

before and after watching the

landscapes in the given field

areas.

PP

Quantitative. Non-randomized

controlled trial, within-subjects

design. The aim of this study

was to demonstrate how the

intervention of walking in

urban parks during the fall

season impacted participants’

heart-rate and stress levels.

Students walked 15 min each

on specific trails in a park and

in a nearby urban area (the

control). HR, HRV, the State

Trait Anxiety Inventory, and

POMS, were measured to

assess the difference outcomes

between walk-sites.

PP

Findings

Researchers found that HRV of

subjects in the forest area was

significantly higher than that of

subjects in the city area. On the

other hand, both pulse rate and

salivary cortisol concentration

of subjects in the forest area

was significantly lower than

that of subjects in the city area.

The walk in the park enhanced

relaxation in the participants

via parasympathetic nervous

system stimulation, while

sympathetic nervous system

stimulation was decreased.

Heart-rate lowered overall.

Suggests the effectiveness of

even “small” green areas on

heart-rate variability.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

23 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Tsunetsugu

[40]

Song [41]

Country

Japan

Japan

Population

Male university students were

recruited for this study. All

were deemed healthy at the

time of the trial.

Participants recruited for this

study were adult male

Japanese citizens with a history

of prehypertension and/or

current hypertension deemed

in suitable physical condition

to participate in this study.

Sample

N = 12; Males aged 21 to 23

(mean ± SD: 22.0 ± 1.0).

N = 20; Adult men with a mean

age of 58.0 ± 10.6 years.

Setting

Conducted in a broadleaf

forest mainly Nukumidaira,

Oguni, Yamagata, Japan.

Akasawa Shizen Kyuyourin;

Akasawa natural recreation

forest within Agematsu town

of Nagano Prefecture in central

Japan. The control was a city

area within A City of Nagano

Prefecture, Japan.

Aim & Design

To study the physiological

effects of SY were examined by

investigating blood pressure,

pulse rate, heart rate variability

(HRV), salivary cortisol

concentration, and

immunoglobulin A

concentration in saliva.

Subjective feelings of being

“comfortable”, “calm”, and

“refreshed” were also assessed

by questionnaire. Physiological

measurements were conducted

six times, i.e., in the morning

and evening before meals at

the place of accommodation,

before and after the subjects

walked a predetermined

course in the forest and city

areas for 15 min, and before

and after they sat still on a

chair watching the scenery in

the respective areas for 15 min.

PP

To look at the effects of forest

walking on the autonomic

nervous system in middle aged

hypertensive adults. Subjects

were instructed to walk

predetermined courses in

forest and urban (control). The

course length was 17-min.

Walk walking speed and

energy expenditure were equal

between both groups. HRV

and HR were used to quantify

physiological responses.

PP

Findings

Data of the study revealed that

blood pressure and pulse rate

were significantly lower, and

that the power of the HF

component of the HRV tended

to be higher and LF/(LF + HF)

tended to be lower. Salivary

cortisol concentration was

significantly lower in the forest

area, and feelings of comfort

were significantly higher in the

forest area.

HR significantly lower and

high frequency component of

HRV was significantly higher.

Questionnaire results indicate

after walking in the forest the

feelings were increased around

comfortable, relaxed, natural,

vigorous, decreased tension

and anxiety, depression,

anxiety hostility, fatigue and

confusion. A brief walk in the

forest elicited psychological

relaxation and physiological

calm on the subjects.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

24 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Country

Kardan [42]

Canada

Grazuleviciene

[43]

Lithuania

Population

Sample

Setting

Large urban population in

Toronto, Canada.

Tree lined streets in urban

neighborhoods.

The study was conducted in

Toronto, Canada.

20 male and female residents of

Kaunas, Lithuania each with a

diagnosis of Coronary Artery

Disease and cardiac

comorbidities being treated at

the Cardiologic Clinic of the

Hospital of Lithuanian

University of Health Sciences.

N = 20; Male and female

participants with a mean age of

62.3 ± 12.6 years.

The study was conducted in

Kaunas. The urban exposure

area was a street near the

Hospital of Lithuanian U.

Cardiology Clinic. The green

exposure region was a pine

tree park located near the

Cardiology Clinic.

Aim & Design

Findings

Multivariate study combining

high-resolution satellite

imagery and individual tree

data from Toronto with

self-reports of general health

perception, cardio-metabolic

conditions and mental illness

derived from the Ontario

Health Study.

Having 10 or more trees in a

city block improves health

perception in a way that is like

an increase in annual personal

salary of $10,000. And, having

11 more trees in a city block

decreased cardio-metabolic

conditions in ways compared

to an increase in an annual

personal income of $20,000.

Quantitative Randomized

Controlled Trial was to study

the impact of forest-walking on

patients being treated for CAD.

Participants were randomly

assigned to either green or

urban exposure groups and

walked in these different

environments for 30 min on 7

consecutive days. Researchers

aimed to determine how the

different environments

impacted patients’

hemodynamics and state of

their CAD diagnoses. Testing

involved pretest phenotype

questionnaires, various health

assessment tools including:

SBP, DBP, HR, PWV, ECG, W

(workload), Spiroergometry.

PP

Walking in a park had a more

positive effect on overall

cardiac function in patients

than walking in urban

environments.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

25 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Jia [44]

Ohtsuka [45]

Country

China

Japan

Population

Adult patients diagnosed with

Chronic Obstructive

Pulmonary Disease, from the

region of Hangzhou, China,

with no exacerbations of COPD

within 6 weeks of the trial.

Researchers culled their

participants from a sample of

patients being treated for Type

II Diabetes with an age range

of 60–83, mean height

154.0 ± 1.3 cm, and mean body

mass index (BMI) of

23.6 ± 0.4 kg/m2.

Additionally, researchers

incorporated data from

longitudinal studies

addressing Type II Diabetic

patients over a period of 6

years. This increased the

sample to 116 persons, from

which 25 paired samples were

studied. Healthy subjects were

used as a control.

Sample

N = 20; male and female adult

participants aged 60 to

79 years.

N = 48 (16 males and 32 female)

Type 2 Diabetic patients with a

mean age of 66.8 years.

Setting

Hangzhou, China

Research facility and nearby

recreational areas in connection

with Hokkaido University,

Japan.

Aim & Design

Elucidate health effects of a FB

trip on elderly patients with

chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD).

Subjects were randomly

divided into two groups. One

group was sent to forest, and

the other was sent to an urban

area as control. Flow cytometry,

ELISA, and profile of mood

states (POMS) were evaluated.

PP

Quantitative longitudinal

study aimed to address the

effects of Shinrin-Yoku on

blood glucose levels in patients

with Type II Diabetes. In an

effort to summarize data from

future studies, the author of

this article noted that an

additional sample of 116

persons, organized into 25

paired groups were

incorporated. Available data

reflects these additional

participants.

Of the initial sample (n = 48),

11 participants experienced

only dietary and exercise

therapy, 27 were given oral

medication, and 10 were being

treated with insulin

administration at the time of,

and during the study.

Pre and posttest measures of

blood glucose were taken at

specific timed intervals during

the intervention process.

Participants were assessed after

morning meals at the research

Findings

Within the forest group, there

was a significant decrease of

perforin and granzyme B

expressions, accompanied by

decreased levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines

and stress hormones.

Meanwhile, the scores in the

negative subscales of POMS

decreased after FB trip. These

results indicate that FB trip has

health effect on elderly COPD

patients by reducing

inflammation and stress level.

NA

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851

26 of 48

Table 1. Cont.

Study

Country

Population

Sample

Morita [46]

Japan

71 healthy adult volunteers

participated in this study. Ages

ranged from teens to late 70s.

N = 71; 43 males and

28 females.

Sung [47]

The

Republic of

Korea

Recruitment included stable

patients with stage 1 HTN,

and/or patients who were on

antihypertensive medication.

N = 56; Males and females

aged 63–73 years.

Setting

Ryukoku Forest of Ryukoku

University in Shiga Prefecture,

located in the western region of

Honshu, Japan. Data analysis

took place at the University of

Shiga, Japan.

The forest group participated

at two recreation forest sites

including Hoengseong and

Saneum, in Kangwon-do,

Republic of Korea. The control

group maintained regular

treatment at the treatment

facility.

Aim & Design

hospital. Peripheral venous

blood samples were collected

for glucose levels. Participants

were divided into two

forest-walking groups. Glucose

samples were drawn again

post Shinrin-yoku treatment.

PP

Pre and posttest study was to

evaluate the immediate effects

of forest walking in a

community-based population

with sleep complaints.

Two-hour forest-walking

sessions were conducted on 8

different weekend days. Sleep

conditions were compared

between the nights before and

after walking in a forest by

self-administered

questionnaire and actigraphy

data.