AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

An Assessment of Therapeutic Skills and Knowledge of Outdoor Leaders

in the United States and Canada

Matthew M. McCarty

Submitted in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the degree

of Master of Arts from Prescott College

in Adventure Education

May, 2014

Christine Lynn Norton, Ph.D.

Graduate Mentor

Mark Wagstaff, Ed. D.

Second Reader

Denise Mitten, Ph.D.

Core Faculty

1

UMI Number: 1557626

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript

and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

UMI 1557626

Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author.

Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

All rights reserved. This work is protected against

unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code

ProQuest LLC.

789 East Eisenhower Parkway

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Abstract

Using an online survey methodology and descriptive statistics, 92 self-identified outdoor leaders,

representing a spectrum of wilderness experience programs in the United States and Canada,

were surveyed to ascertain their knowledge of select psychological theories and concepts

relevant to outdoor leadership. This study explores personal leadership philosophies, attitudes,

and practices and knowledge regarding the facilitation of trip participants’ relational

development with self, others, and the natural world. General findings indicate that leaders

possess a range of knowledge and skills to facilitate participants’ relational development.

Therapeutic outdoor leadership is tripartite relational theory emerging from outdoor

programming literature. This study finds that leaders are actively nurturing participant well-

being through a relational framework, indicated by the 34% of respondents who agree with the

author’s definition of outdoor leadership, addressing relational development of intra, inter, and

transpersonal domains. However, findings indicate that leaders do not necessarily have, or are

being educated in content and skills to maximize their abilities to develop outdoor program

participants’ relational abilities. Less than 13% of outdoor leaders are familiar with the concepts

of therapeutic alliance, transference, and countertransference. Nearly all outdoor leaders claim

to facilitate participant-nature relationships, approximately 80% use nature based metaphors,

72% use ceremonies or rituals, and most of the benefits attributed to contact with nature were

identified. Most participants are unfamiliar with conservation psychology, the biophilia

hypothesis, or ecopsychology. Almost half of outdoor leaders understand what self-efficacy

describes and 55% of respondents were familiar with locus of control. Additionally, this survey

explores leaders’ perceptions about trust factors, how they define emotional safety, relevant

professional boundaries, and feedback giving strategies.

2

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Keywords: outdoor leadership, therapeutic leadership, adventure education, relational

leadership, relationship-based programming, therapeutic outdoor leadership

3

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Copyright © 2014 by Matthew M. McCarty

All rights reserved.

No part of this thesis may be used, reproduced, stored, recorded, or transmitted in any form or

manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder or his agent(s), except

in the case of brief quotations embodied in the papers of students, and in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Requests for such permission should be electronically addressed to:

Matthew M. McCarty

m.m.mccarty.ae@gmail.com

4

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................12

Chapter 1: Introduction..............................................................................................................14

Purpose of Study.........................................................................................................................14

Research Question......................................................................................................................15

Definitions of Key Terms...........................................................................................................16

Being Therapeutic Versus Doing Therapy.................................................................................17

The Author’s Background and Paradigm...................................................................................19

Grounding Research Theories.....................................................................................................19

Chapter 2: Review of the Literature..........................................................................................22

The Centrality of Relationships..................................................................................................22

The Need for Relationships.....................................................................................................23

Psychopathology Characterized by a Lack of Relationships...................................................25

Relational Leadership.................................................................................................................26

Therapeutic Alliance and Influences.......................................................................................30

Ethical Leadership...................................................................................................................32

An Ethic of Care......................................................................................................................34

Emotional Intelligence.............................................................................................................36

Self-Awareness and Values.....................................................................................................37

Outdoor Leadership and Relationships.......................................................................................39

Competency Approaches to Outdoor Leadership....................................................................39

Relationship Driven Outdoor Leadership................................................................................42

Emotional safety......................................................................................................................44

5

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Psychological Depth................................................................................................................46

A Tripartite Relational Model for Outdoor Leaders................................................................48

Relationship with self...........................................................................................................49

Locus of control.................................................................................................................50

Self-efficacy.......................................................................................................................50

Facilitating a sense of self..................................................................................................51

Relationship with others.......................................................................................................52

Facilitating a relationship with others................................................................................53

Relationship with nature.......................................................................................................55

Facilitating a relationship with nature................................................................................57

Benefits of nature...............................................................................................................58

Attentional improvements...............................................................................................58

Stress reduction...............................................................................................................59

Affective improvements..................................................................................................60

Cognitive improvements.................................................................................................60

Transcendent experiences...............................................................................................61

Other benefits..................................................................................................................61

Relationship Influences Upon Outdoor Programming Outcomes...........................................62

Techniques of Relational Leaders............................................................................................63

Communication.....................................................................................................................64

6

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Trust and rapport development.............................................................................................66

Feedback...............................................................................................................................67

Ceremonies and rituals..........................................................................................................69

Use of metaphors..................................................................................................................70

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY............................................................................................72

Research Design..........................................................................................................................72

Survey Characteristics................................................................................................................73

Sampling Procedure....................................................................................................................73

Participant Characteristics..........................................................................................................76

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS...........................................................................................................79

Training and Beliefs of Outdoor Leaders...................................................................................79

Motives for Working Outdoors................................................................................................79

Decision-Making Influences....................................................................................................82

Characteristics of Outdoor Program Participants....................................................................83

Participant Needs: Motivational and Relational......................................................................84

Relational Leadership.................................................................................................................85

Therapeutic Alliance................................................................................................................85

Professional boundaries........................................................................................................87

Emotional disclosure.............................................................................................................88

Managing Acting Out Participants...........................................................................................88

Relationship with Self..............................................................................................................89

Self-efficacy..........................................................................................................................89

7

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Locus of control....................................................................................................................90

Interpersonal Relationships......................................................................................................91

Relationship with Nature.........................................................................................................92

Nature-based psychological theories....................................................................................93

Benefits of nature..................................................................................................................94

Techniques of Relational Leaders............................................................................................95

Trust and rapport development.............................................................................................95

Feedback strategies...............................................................................................................96

Ceremonies and rituals..........................................................................................................97

Use of metaphors..................................................................................................................99

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS...........................................................100

Outdoor Leadership..................................................................................................................101

Why People Work as Outdoor Leaders.................................................................................101

What is Outdoor Leadership..................................................................................................101

Influences to Decision-Making..............................................................................................103

Risk-management as primary influence. ............................................................................104

Need for therapeutic emphasis in decision-making............................................................105

Factors Influencing Relationship Development.....................................................................106

Therapeutic alliance............................................................................................................106

Transference and countertransference................................................................................107

Professional boundaries......................................................................................................108

Trust and rapport development...........................................................................................109

Feedback strategies............................................................................................................111

8

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Implications for practice: Education and Training Needs for Relationally Oriented Outdoor

Leaders......................................................................................................................................112

Academic Training.................................................................................................................112

Employer Provided Training..................................................................................................114

Training Needs in Psychological Constructs.........................................................................115

Self-efficacy........................................................................................................................118

Locus of control..................................................................................................................119

Environmental psychologies...............................................................................................120

Human needs.......................................................................................................................121

Emotional Risk Management.................................................................................................123

Self-Awareness......................................................................................................................125

Advancing Outdoor Leaders’ Personal Growth.....................................................................126

Technical Training Needs for Relational Leaders.................................................................127

Sequencing activities..........................................................................................................127

Ceremonies and rituals.......................................................................................................127

Wilderness solos..............................................................................................................128

The use of metaphors..........................................................................................................129

Implications for Practice: Relationship Development with Self, Community, and the Natural

World........................................................................................................................................130

To be Therapeutic..................................................................................................................130

Fostering Relationships with Self..........................................................................................131

Fostering Relationships with Community.............................................................................133

9

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Fostering Relationships with Nature......................................................................................135

An Emerging Model: Therapeutic Outdoor Leadership..........................................................143

Limitations................................................................................................................................147

Areas for Future Research........................................................................................................149

References...................................................................................................................................154

Appendix: A Complete list of survey questions with provided answers..............................167

10

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Tables and Figures

Tables

Table 1 Characteristics of Outdoor Leaders.................................................................................79

Table 2 Reasons for Working as an Outdoor Leader (non-relational)...........................................80

Table 3 Relational Motives for Working as an Outdoor Leader..................................................81

Table 4 Employer Provided Training...........................................................................................83

Table 5 Mental Health and Life Issues of Outdoor Program Participants....................................84

Table 6 Work Related Boundaries Outdoor Leaders are Mindful of ...........................................87

Table 7 How Outdoor Leaders Facilitate Relationships Between Participants and the Natural

Environment.......................................................................................................................93

Table 8 Assumed Human Benefits From Exposure/Immersion in Nature...................................94

Table 9 The Most Important Traits Fostering Trust in Outdoor Leaders.....................................95

Table 10 Rapport Development Strategies Used by Outdoor Leaders.........................................96

Table 11 Feedback Strategies Used by Outdoor Leaders.............................................................97

Table 12 Types of Ceremonies and Rituals Outdoor Leaders Facilitate......................................98

Table 13 Rituals Fostering Relationships in Three Domains.......................................................99

Table 14 Outdoor Leadership Experience..................................................................................100

Table 15 Education of Outdoor Leaders: Comparing Medina (2001) and McCarty (2014)......113

Table 16 Outdoor Leaders’ Familiarity with Environmental Psychology Constructs................121

Table 17 Comparison of Substantiated and Assumed Benefits of Nature..................................138

Figures

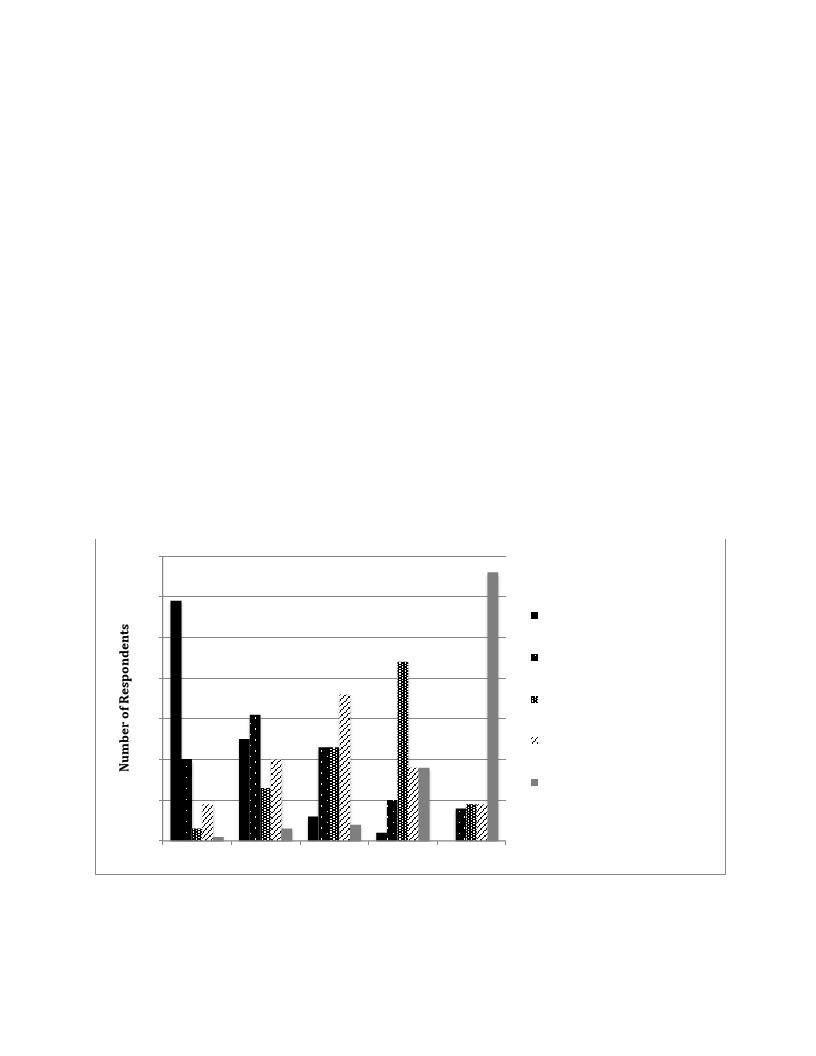

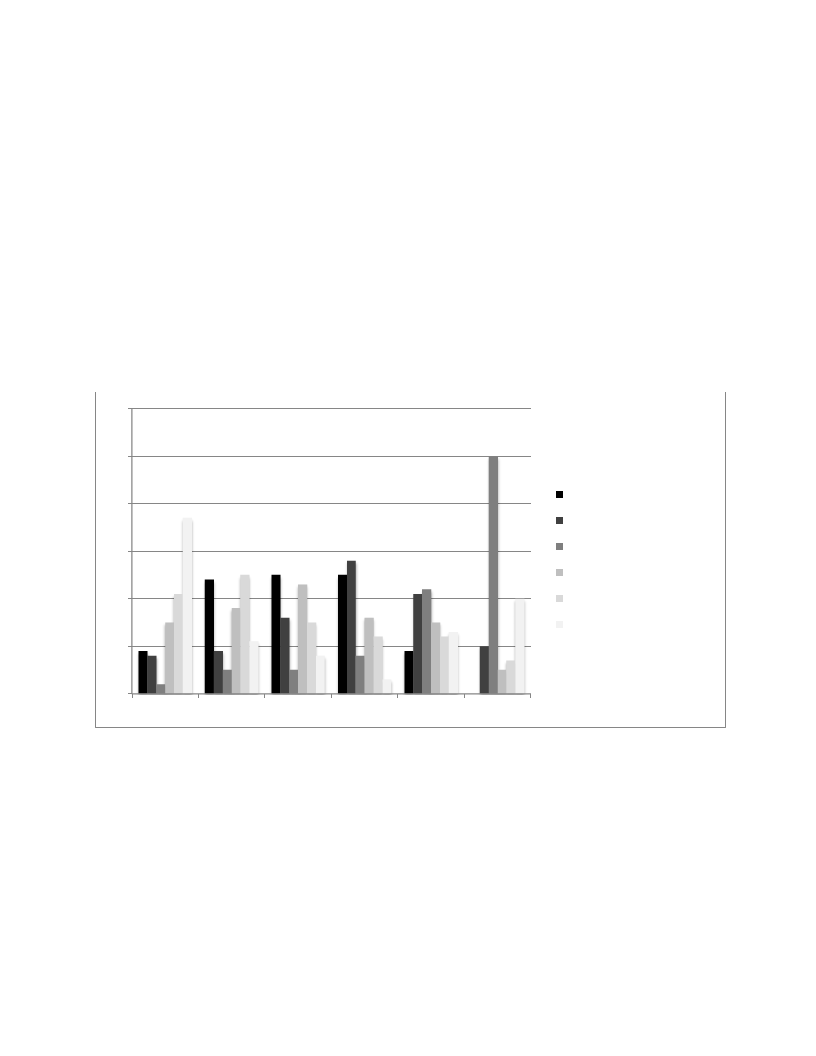

Figure 1 Ranking of Factors Affecting Outdoor Leaders’ Decision-Making Processes..............82

Figure 2 Assumed Motivational Needs of Participants in Outdoor Programming.......................85

11

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Acknowledgements

Graduate school has been a multi-year endeavor, at two institutions and in two different

fields. I feel fortunate to have attended Prescott College as both an undergraduate and graduate

student. The opportunities to pursue my academic passions and design my own academic

program are unrivaled in academia. “Trust the process” is Prescott’s motto, and the result is this

thesis on outdoor leadership.

I am grateful to all the scholars, presenters, and participants I’ve met and talked with at

professional conferences hosted by the Therapeutic Adventure Professional Group, the

Association of Experiential Education, the Wilderness Education Association, the National

Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, and the Wilderness Risk Management

Conference, as well as the many presenters and fellow students at colloquia hosted by Prescott

College.

As for my thesis committee, profound heartfelt gratitude is what I wish to express. I met

Dr. Mark Wagstaff at an AEE international conference. He expressed interest and willingness to

serve on my committee, with limited introduction to me or my ideas. Mark’s feedback has been

through the lens of outdoor leadership, and he has helped me see how my ideas can make an

impact in the field of outdoor programming. Dr. Denise Mitten has been instrumental in me

reaching the end of my graduate studies. Her administrative, academic, and interpersonal

flexibility have been critical to my development as a student, scholar, and adventure educator.

Denise and I started in Prescott’s Master of Arts Program at the same time, and I’m so impressed

to watch it grow with her vision. Lastly, I owe a tremendous debt to Dr. Christine Lynn Norton.

From our first meeting, where I broke down emotionally-trying to figure out my place in the

12

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

world of helping others, to every conversation where she has been an unwavering cheerleader,

ceaselessly motivating me to get my thesis done! Christine, your zest for life, academic rigor,

and passionate approach to mentorship has been so appreciated by me. I do not think I would

have finished this project without your ongoing support.

Lastly, I wish to thank my partner Charity Pape, for both her patience and support in

accomplishing the monumental task of completing this thesis. To my nine-month old daughter,

Scout, I hope I am able to be both a father and a therapeutic outdoor leader to you, helping you

with your relational development, and supporting your life long process towards well-being.

13

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Purpose of Study

Among the many variables that exist in outdoor recreation, education, or adventure,

relationships prove to be fundamental to human experience. The inherent relational aspects of

outdoor and adventure education is articulated within academic literature. For example, Priest

(1986) described four types of relationships relevant to outdoor education: intrapersonal,

interpersonal, ecosystemic, and ekistic. Gair (1997) described outdoor education as, “an

approach or a methodology by which challenging activities and the natural environment provide

an arena for the personal, social and educational development” of people (p. 2). However, there

is a lack of consistent emphasis upon the knowledge and skills outdoor leaders should possess

and exhibit in order to support the relational development of outdoor program participants, and

the importance or duty of outdoor leaders to nurture participant relationships.

The goal of this research project was to explore outdoor leaders’ knowledge of select

psychological theories and concepts applicable to working with participants out of doors;

specifically those relevant to relationship development, as well as their practices in facilitating

relationships for participants they lead. This thesis research represents a shift from studying

leadership traits and practices, the application of leadership, competency models, and leadership

theories, to exploring outdoor leaders’ understanding of psychological theories and universal

human needs when working with diverse populations across diverse wilderness experience

program types.

The rationale guiding this project is that outdoor leaders have a great responsibility, and

potentially a great influence on the participants they lead. Outdoor leaders can positively

influence participant well-being across multiple dimensions through the development of

14

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

relationships. This thesis introduces a relational matrix that may simplify the focus and practice

of outdoor leadership and highlights the need to advance applicable psychological theories and

professional practices within outdoor leadership training and education. This can be

accomplished when outdoor leaders are knowledgeable of relevant psychological theories and

counseling psychology approaches. With this knowledge, outdoor leaders can adopt professional

practices that generate improved participant outcomes in the dimension of personal well-being.

This author contends that outdoor programming begins not with content, but with people, and

that a fundamental purpose of outdoor leaders is to improve the well-being of those they lead.

The facilitation of the three-fold relational matrix of self, community, and nature is described in

this paper as therapeutic outdoor leadership.

Survey questions were designed to capture information about outdoor leaders’ awareness

and understanding of theories and constructs relevant to working with people generally, and

working in nature specifically, as well as how they facilitate relationships. Psychological topics

explored include rapport and trust development, self-efficacy, locus of control, transference and

countertransference, professional boundaries, benefits of human connection to nature, and

awareness of ecopsychology, the biophilia hypothesis, and conservation psychology. Outdoor

leaders were asked about their techniques for: giving feedback and developing rapport; creating

or facilitating rituals; using metaphors for personal growth; facilitating connection to the natural

world for their participants; intervening with isolative participants; creating emotional safety in

groups; and influences affecting their decision-making processes.

The Research Question

This thesis research is guided by the question: what therapeutic knowledge and relational

skills do outdoor leaders, representing a spectrum of wilderness experience programs (WEP),

15

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

have that directly relate to modeling, facilitating, and building healthier relationships within

participants, within communities, and between participants and the natural world?

Definitions of Key Terms

Adventure education: describes a field of study and body of practices that attempt to encourage

personal growth through adventure-based experiences.

Adventure programming: “is the deliberate use of adventurous experiences to create learning in

individuals or groups, that results in change for society and communities” (Priest, 1999,

p. xiii).

Adventure therapy: specialized outdoor programming attempting to treat clinical mental health

issues.

Ecopsychology: an interdisciplinary field exploring the reciprocal relationship between human

health and the health of the natural world.

Locus of control: describes how individuals attribute outcomes in their lives.

Outdoor education: is an umbrella term that includes environmental education and adventure

education.

Outdoor leader: a person responsible for the physical and emotional safety of outdoor

participants and is responsible for implementing activities to achieve desired outcomes.

Self-efficacy: describes how someone perceives their abilities, which influences personal

performances.

Relational leadership: a leadership orientation that starts with people first, as opposed to task

accomplishment, and involves the conscious intention to foster relationships.

Therapeutic: describes intentional approaches and interventions that yield healing, restorative,

reparative, or positive effect upon well-being.

16

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Therapeutic alliance: in specific terms it refers to the relationship between a psychotherapist and

client, in general terms it describes the nature of relationships between helpers and those

being helped.

Therapeutic outdoor leadership: a relationally oriented approach to leadership that involves

fostering and facilitating relationships across intrapersonal, interpersonal, and

transpersonal domains.

Well-being: can be understood as a multi-dimensional construct, expressed across spiritual,

intellectual, social, physical, emotional, and occupational domains.

Wilderness experience programs (WEPs): the broadest label used to describe any type of

program operating outdoors. Examples of WEPs might include recreation programs or

outdoor ministry, among others.

Being Therapeutic Versus Doing Therapy

This paper explores how and if outdoor leaders are interacting with participants in a

therapeutic manner, within their scope of practice and training, that foster the fulfillment of

human relational needs. For clarity, it is important to distinguish and define therapeutic

interactions from therapy (clinical psychotherapy), as these terms and roles may be confusing for

some outdoor leaders. Describing the similarities between therapists and outdoor guides Bodkin

and Sartor (2005) wrote,

In some ways a [wilderness] guide is similar to a therapist. Both therapists and guides

must have excellent listening skills and be able to help clients clarify important issues.

Both need to assess potential participant/client risks (physical and psychological), and be

capable of intervening in crisis situations. Both need to be aware of power dynamics in

17

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

relationships with participants/clients, especially potential abuses of power with

vulnerable people. (p. 46)

Despite these similarities, the differences between the processes of being therapeutic versus

conducting therapy are evident. Berman and Davis-Berman (2000) help distinguish the

differences of these terms. Therapeutic is

an adjective, [and] indicates factors that may be conducive to emotional well-being and

may apply to a variety of activities and programs….[Therapy], a noun, involves a process

of assessment, treatment planning, the strategic use of counseling techniques…and the

documentation of change. (p. 2)

To provide therapy requires professional, academic, and clinical training for addressing

problematic and sometimes significant, psychologically driven life challenges. However, to be

therapeutic, one needs simply to contribute to the well-being of another. In this thesis, the term

therapeutic describes intentional approaches and interventions that yield healing, restorative,

reparative, or positive effect upon well-being.

Research has demonstrated that relationships, and the drive to develop and maintain

them, are essential to human well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Well-being can be

understood as a multi-dimensional construct, expressed across spiritual, intellectual, social,

physical, emotional, and occupational domains (National Wellness Institute, 2014). Well-being

and personal growth are used interchangeably in this paper. Hendee and Brown (1987) defined

personal growth as, “a range of effects toward expanded fulfillment of one’s capabilities and

potential” (p. 2). Adventure and nature-based programming clearly promote well-being across

multiple dimensions, such as physical, social, cognitive, emotional, and even spiritual (Bobilya,

18

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Akey, & Mitchell, 2009). Therapeutically oriented outdoor leaders, assisting people in

actualizing their relational and psychological needs, can enhance well-being.

The Author’s Background and Paradigm

The author’s employment history working in nature spans twenty five-years, starting at

the age of 15. However, it was not until his early 30s, working in the field of wilderness therapy

that he embarked and matured as an outdoor leader. This occupational pursuit initiated graduate

study in counseling psychology; however, the author subsequently left this discipline to study

adventure education, which felt more pertinent to his personality, interests, and professional

ambitions. Initially the author was not interested in leadership, but during his adventure

education studies he was struck by what he considered the minimal focus on relationship

development and facilitation within outdoor leadership textbooks, particularly the human

connection with nature. This thesis embodies the author’s interests in both counseling

psychology and adventure education.

This study’s intention is to situate outdoor program participant well-being as a central

focus of outdoor leadership, using a tripartite relationship development framework. It is the

author’s assertion and assumption that when outdoor leaders actively nurture participant

relationships within the three domains of self, community, and nature that participant well-being

is improved and program outcomes are positively affected. The author’s ambition is to actively

promote germane therapeutic practices and knowledge found in counseling psychology and

ecopsychology within adventure education theory and practice.

Grounding Research Theories

This thesis is rooted in the belief that humans have an innate need for relationships: with

themselves, human communities, and with the natural world, and that outdoor leaders have a

19

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

responsibility to facilitate and foster these relationships. The belongingness hypothesis

(Baumeister & Leary, 1995) and ecopsychology are the grounding theories of this relationship-

oriented approach. The belongingness hypothesis advanced by Baumeister and Leary (1995) has

been cited extensively (over 7,400 times according to http://scholar.google.com/, retrieved May

18, 2014). This theory asserts that “human beings have a pervasive drive to form and maintain at

least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and significant interpersonal relationships” (p.

497), and that a lack of belongingness can cause a variety of ill effects. Baumeister and Leary

(1995) asserted that the human need to belong has an evolutionary basis, stating that social bonds

presumably provide survival and reproductive benefits.

Ecopsychology is “a blending of environmental philosophy, ecology, and psychology

that…explores how our psychological health is related to the ecological health of the planet”

(Mitten, 2009, pp. 22). Norton (2009) explained how ecopsychology focuses on human well-

being in relation to the natural environment. Ecopsychology aims to transform “humankind’s

dissociative relationship with the other than human natural world” (Adams, 2005, p. 269).

Ecopsychology research explores how the human need for belonging includes relationship with

the natural world and asserts that human well-being is inextricably tied to the health of the

natural world-that they are mutually dependent.

Wilson (1993) postulated that humans have an evolutionary urge to connect to nature and

an innate need to affiliate with biological life and lifelike processes. Wilson (as cited in McVay,

1993) named this urge biophilia, and defined it as “the innate tendency to focus on life and

lifelike processes” (p. 4). This proposition “suggests that human identity and personal

fulfillment somehow depend on our relationship to nature” (Kellert, 1993a, p. 42).

Ecopsychology, along with the biophilia hypothesis, provide a philosophical framework for why

20

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

humans need connection with nature. If the ecopsychology paradigm is well-founded, it seems

appropriate that outdoor leaders understand human psychology, particularly elements relevant to

humans and their connection with nature. This exploratory and descriptive research examines

outdoor leaders’ education and training, and beliefs and practices regarding the relational

development of the people they lead.

21

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

CHAPTER 2: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

The Centrality of Relationships

The literature reviewed explores the nature of relationships broadly and their role in

outdoor programming specifically. Additionally, components important in relationship

development and facilitation, along with select psychological theories and concepts that are

relevant to outdoor programming outcomes, as well as skills outdoor leaders may use to foster

relationships in their participants are examined. Referencing specific concepts acknowledged in

the literature, such as self-efficacy, this paper contributes to the subject matter by ascertaining

outdoor leaders’ skills and knowledge of concepts that have been shown to influence outcomes

in adventure and nature programming. Likewise, this author reviewed important psychological

topics in the literature in order to guide the development of the survey used to assess outdoor

leaders’ knowledge and skills in these areas.

The idea of personal identity being formed through relationships is foundational to the

ideas of well-being, adventure education, and therapeutic outdoor leadership. McLean’s (2005)

research found, “identity is made up of meaning-filled experiences and also of self-defining fun

experiences that induce pleasure and enjoyment” (p. 689). Uhl-Bien (2006) explained that self-

concept is “constructed in the context of interpersonal relationships and larger social systems” (p.

664). Thus, personal identity is constructed through meaning making and personal narrative, and

the resulting insights are definitional to intrapersonal relationships. Relationships, including

their quality, are a cornerstone of self-concept. Burke, Nolan, & Rheingold (2012) summarized

Noddings’ contention “that humans are relational beings who construct meaning out of

encounters with other people, objects, and environments and then use these encounters both to

define ourselves and to be defined by them” (p. 6). Relational-ontology is the perspective that

22

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

the self is always a self in relationships, or as Slife (2004) succinctly wrote, “Each thing,

including each person, is first and always a nexus of relations” (p. 159). Furthermore, Slife

(2004) explained a relationalist ontology “assumes we are always and already community” (p.

168), and that differences between members of a community are essential and serve as a strength

within communities, and conflict is perceived as opportunities for “learning, growth, and

intimacy” (p. 173). Another relevant concept is the term holon. This describes how an entity is

both autonomous, yet simultaneously a component of other systems. For example, each person

is imbedded in a network of co-occurring and interrelated relationships, while also being self-

sufficient. Humans often refer to the self, forgetting that the self is bound within larger systems.

Conn (1995) cautioned us about how we establish boundaries between systems. If the boundary

around self is too rigid, we separate ourselves from larger systems, and if they are too diffuse, we

may lose our perspective and get lost in the larger whole. When we consider all the relationships

we as humans are part of, it is the collection of these relationships, perennially changing through

time that informs our personal identity.

The Need for Relationships

Relationships, including their presence, absence, and strength, figure prominently in

human experience, human well-being and development, and outdoor programming. Baumeister

and Leary (1995) postulated that humans have a pervasive drive to form a minimum quantity of

lasting interpersonal relationships that involve mutual caring for one another. In essence,

humans need relationships. Relationships can be discerned on a continuum from mindful,

intentional connection, to connection by happenstance, and by looking at relationship

development and maintenance in both temporal and environmental contexts. Mitten (1995)

distinguished two types of relationships: those that are based on healthy bonds, leading to

23

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

trusting and secure relationships, and those based on reactionary bonding leading to potentially

unhealthy relationships. Unhealthy relationship formation may be rooted in a person’s family of

origin. Healthy relationships are based upon “mutual respect, trust, and experience with one

another” (Mitten, 1995, p. 83).

Two pervasive human motivational theories widely cited in psychology and outdoor

related literature are Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (1943) and Glasser’s (1998) Choice Theory.

Both address the principle need for caring relationships. Maslow’s hierarchy highlighted the

human need for belongingness and love, relationships and friends. Glasser also identified love

and belonging as one of our five essential needs. Subsequent research substantiates the belief

that relationships are essential to well-being, from a physiological standpoint. Allan, McKenna,

and Hind (2012) wrote, “evidence supports the notion that relationships and their inherent

qualities are brain rewiring agents which protect and provide potential for growth” (p. 8).

In addition to intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships, there are an increasing

number of professionals and nonprofessionals advocating for human well-being by promoting

the human-nature relationship. Newer lines of inquiry, such as ecopsychology, are expanding

the prominence of human relationships with the larger than human world. Traditional

perspectives of psychotherapy are being critiqued because of the lack of prominence given to the

human-nature relationship. Beringer (2004) stated that traditional psychology views the

relational self as a human-to-human relationship, and emphasizes an atomistic reduction of the

individual. Beringer identified social psychology’s lens for viewing humans in a contextual

perspective, acknowledging humans are defined by their relationships. He advocated for the

acknowledgement of the “ecological self.” Norton (2009) encouraged social workers to include

the natural world in their systems approach to mental health. Watkins, (2009) in critiquing

24

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

psychotherapy wrote, “Euro-American psychotherapeutic practices have largely left out the

relational web among person, community, and natural and built environments” (p. 224).

Psychopathology Characterized by a Lack of Relationships

But what are the potential consequences of unhealthy relationships, or a lack of

relationships? Adams (2005) explained, “psychopathology involves merely part of a person

relating with part of the world” (p. 277). Chalquist (2009) wrote, “Disconnection from the

natural world...produces a variety of psychological symptoms that include anxiety, frustration,

and depression” (p. 70). A focus on autonomy, or self, begins the process of psychopathology.

“The illusion of separateness we create in order to utter the words ‘I am’ is part of our problem

in the modern world” (Christie, as cited in Roszak, 1995, p. 12). Ecopsychologists voice the

need for humans to have relationships with nature in order to enhance well-being. “As human

beings we have a need for place-where we can be connected to a community of people, plants,

animals, and the land. Without this, we feel lost, alone, and alienated” (Robinson, 2009, p. 29).

And in popular culture, Louv (2005) introduced the term nature deficit disorder to the general

public’s vocabulary and consciousness, clearly highlighting the fact that a lack of connection

with nature negatively affects mental health.

Baumeister and Leary (1995) articulated that the human need to belong is so strong, it

explains why individuals maintain relationships with people who abuse them.

Many of the emotional problems for which people seek professional help (anxiety,

depression, grief, loneliness, relationship problems, and the like) result from people’s

failure to meet their belongingness needs. Furthermore, a great deal of neurotic,

maladaptive, and destructive behavior seems to reflect either desperate attempts to

establish or maintain relationships with other people or sheer frustration and

25

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

purposelessness when one’s need to belong goes unmet. (Baumeister & Leary, 1995, p.

521)

Teo, Choi, and Valenstein (2013) note empirical evidence that “social isolation and negative

social interactions are associated with depression and suicide” (p.1). Robinson (2009) described

one source of psychopathology:

Most people in our culture have been treated like objects all their lives. This is the source

of the wound to the soul underlying most of the human misery that therapists encounter.

Because people have come to experience themselves as objects, they in turn objectify

other people and commodify the world. They feel alienated, isolated, and empty,

believing their lives hold no meaning. (p. 25)

Relationships are a human need. Ryan and Deci (2000), wrote about needs and explained,

“whether it be a physiological need or a psychological need, is an energized state that, if

satisfied, conduces toward health and well-being but, if not satisfied, contributes to pathology

and ill-being” (p. 74). In summation, insignificant relationships, or the absence of meaningful

relationships-with self, others, or nature, can result in detrimental mental and physical issues,

which compromise personal well-being. One framework to prevent psychopathology in others is

relational leadership.

Relational Leadership

Uhl-Bien (2006) defined relational leadership “as a social influence process through

which emergent coordination (i.e., evolving social order) and change (i.e., new values, attitudes,

approaches, behaviors, ideologies, etc.) are constructed and produced” (p. 668). She conceived

relational leadership theory, which “sees leadership as the process by which social systems

change through the structuring of roles and relationships” (Uhl-Bien, 2006, p. 668). However, in

26

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

this paper the term relational leadership is not intended to refer to any specific theory, rather it

should be interpreted as simply describing a framework of leadership emphasizing relationships.

Universal among all leadership encounters is the human element, and as Reiman and

Rollenhagen (2011) pointed out, “human behavior is always contextual” (p. 1265). Similarly,

human growth is also contextual. Human behavior can be observed in our relationship networks,

and our relationships are contextual to our physical, as well as psychic environments. Ringer

(1999) wrote, “leadership of groups is one of the most complex tasks that human beings can

undertake” (p. 19). Part of this complexity is due to the multifaceted relationships each outdoor

participant is a part of.

Relational leadership is the perspective that the function of leadership is to develop

relationships in those being led. Uhl-Bien (2006) identified two relational leadership

perspectives that may enhance our conceptual understanding: entity and relational. An entity

perspective frames leadership at the individual level, whereas a relational perspective holds that

social reality is a nexus of relationships. Cunliffe and Eriksen (2011) wrote that relational

leaders are responsive to the present moment and problem solving and are able to anticipate what

matters in people’s relational nexuses. “Relational leadership requires a way of engaging with

the world in which the leader holds herself/himself as always in relation with, and therefore

morally accountable to others” (Cunliffe & Eriksen, 2011, p. 1425). Supporting this statement,

Fox and Lautt (1996) wrote, “Moral practice...encompasses relational characteristics: love,

friendship, compassion, caring, passion, and intuition” (p. 22). Relational leadership links

leadership to morality, to the practical elements of relationship formation and effective leader

attributes. However, moral frameworks should not be limited to just interpersonal ethics. Fox

and Lautt (1996) asserted that ethical leaders must “attend to personal development and change”

27

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

(p. 25), and expressed the need to foster relationships between humans and the natural world, as

well as “an urgent need to articulate ethical frameworks and moral practices that respect the

Earth” (p. 23). Supporting this, Burke et al. (2012) wrote, “by fostering positive relationships

between and among students, outdoor programs become a means of moral education, helping

students learn how to be a better person in the world through the group experience” (p. 4).

Cunliffe and Eriksen (2011) stated, “moral responsibility is embedded within relational integrity”

(p. 1439) and explained that relational integrity “encompasses being attuned to the situation,

knowing what to question and how to maintain one’s integrity” (p. 1440). Relational integrity

involves “respecting and being responsive to differences, being accountable to others, acting in

ways that others can count on us, and being able to explain our decisions and actions to others

and ourselves” (Cunliffe, & Eriksen, 2011, p. 1444).

A well-known type of leadership is transformational leadership. “Transformational

leadership involves inspiring followers to commit to a shared vision and goals...challenging them

to be innovative problem solvers, and developing followers’ leadership capacity via coaching,

mentoring, and provision of both challenge and support” (Bass & Riggio, 2006, p. 4). There are

four components of transformational leadership: idealized influence, inspirational motivation,

intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Influence is attributed to the leader’s

behavior and followers’ perceived attributes of the leader. Hayashi and Ewert (2006) found that

outdoor leaders, when compared to the general population, “demonstrated a more

transformational leadership style” (p. 230). According to Bass and Riggio (2006),

“Transformational leaders behave in ways that motivate and inspire those around them by

providing meaning and challenge” (p. 6). Transformational leaders do not publically criticize

their followers, they “pay special attention to each individual follower’s needs for achievement

28

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

and growth by acting as a coach or mentor” (Bass & Riggio, 2006, p. 7). Leaders accept

individual differences and listen effectively. “Transformational leaders gain follower trust by

maintaining their integrity and dedication, by being fair in their treatment of followers, and by

demonstrating their faith in followers by empowering them” (Bass & Riggio, 2006, p. 43). This

author considers transformational leadership to be closely related to relational leadership.

Emphasizes a shared commonality, Brower, Schoorman, and Tan (2000) acknowledge that risk

and trust are central elements to relational leadership. “A leader who is concerned but calm, who

is decisive but not impulsive, and who is clearly in charge can inspired the confidence and trust

of followers” (Bass & Riggio, 2006, p. 57). Important to this study, Bass and Riggio (2006)

noted, “Transformational leaders enhance the self-concept and sense of self-efficacy of

followers” (p. 50).

Hayashi and Ewert (2006) posited that intrapersonal and emotional elements of

leadership have been less acknowledged. When leaders are relationally oriented, emotional

elements of leadership are critical to effectiveness. Knowledge informs human decision-making

and actions. It seems logical then that greater knowledge can improve the effectiveness of

leading others and facilitating personal growth. Various fields in psychology are dedicated to

exploring human behaviors, relationships, well-being, and needs. Operating from the

perspective that humans have universal needs, as well as individual needs, leaders should have

an understanding of basic relational needs, and how best to allow those they lead to achieve

these. Relational leaders can utilize knowledge from counseling psychology and relevant

psychological constructs when attempting to foster personal growth, as well as addressing

general intrapersonal and interpersonal issues.

29

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Therapeutic Alliance and Influences

One of the most intentional human relationships focused on well-being and developing

intrapersonal relationships is professional psychotherapy. This type of relationship can inform

our opinions about the essential need for relationships, relational quality, and their therapeutic

power. The interpersonal connection between a therapist and client is referred to as therapeutic

alliance. Psychological research has shown that the variable most likely to positively affect

clinical treatment progress and therapy outcomes is the therapeutic alliance between therapist

and client (Green, 2009; Flückiger, Del Re, Wampold, & Horvath, 2011; Homrich, 2009).

Therapeutic “alliance is portrayed as the most consistent in-treatment predictor of outcomes and

possessing significant explanatory power in treatment research across numerous

psychotherapeutic approaches and client populations” (Harper, 2009, p. 46). Just as therapeutic

alliance exists between therapists and clients, alliance elements are often present between

outdoor leaders and those they lead.

The determinants of alliance are still being researched, but there are three elements

clearly prominent in therapeutic alliance: mutually agreed upon goals, mutually agreed upon

tasks, and the quality of the attachment between client and therapist (Harper, 2009). Several

therapist qualities have been identified as positively contributing to therapeutic alliance: empathy

and genuineness (Mitten, 1995), caring and openness (Gass, Gillis, and Russell, 2012), and

warmth (Mitten, 1995; Gass et al., 2012). Therapeutic alliance in the medical field is also critical

to patient outcomes. Freshwater and Stickley (2006) found that the most common complaint

regarding medical services is poor communication by medical providers. Affirming these

findings, Baumeister and Leary (1995) asserted that human belongingness needs can only be

fulfilled when the bonds between people are marked by caring and positive concern. The take

30

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

away from this research is that the most important thing a healing person can do is to establish a

meaningful, ethical and caring interpersonal connection with others.

Knapp (1999) believed that outdoor leadership entails facilitating outdoor activities safely

and skillfully, but also involves facilitating “the process of making sense from what is learned”

(p. 219). A purpose of meaning making, is to shift personal narratives, which can inform

intrapersonal relationships. Thus, it is logical that outdoor leaders must understand the value,

purpose, and development of therapeutic alliance with participants in order to foster well-being

through facilitating participating relationships with self, community, and nature, which can

positively affect individual and program outcomes.

Transference and countertransference are two concepts that can influence psychotherapy

and therapeutic alliance and are pertinent to outdoor leadership. Transference, in a therapy

context, describes the “unconscious transferring of experiences from one interpersonal situation

to another. It is concerned with revisiting past relations in existing circumstances. Thoughts

[attitudes] and feelings about significant others from one’s past are projected onto a therapist (or

others) and influence the therapeutic relationship” (Jones, 2004, p. 14). Countertransference is

the opposite experience, in which a therapist is unable to remain unbiased and reacts to the client

as someone from her or his own life. Sources of transference involve people in roles of power,

such as parents, teachers, spouses, or other authority figures. In remote and challenging

environments, amidst foreign and intimate social environments, where there are potential safety

risks, leaders are responsible for making decisions and processing experiences that affect

participants. These dynamic factors influence how participants perceive and relate to their

leaders, both positively and negatively. Through being mindful of these dynamics, and self-

31

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

aware, outdoor leaders can forge more therapeutic relationships when they are familiar with the

concepts of therapeutic alliance, transference, and countertransference.

Ethical Leadership

Ethical leadership is a complex set of relationships and interactions among elements such

as power, empowerment, ethical decision-making, self-awareness, reflection, role of

followers and leaders, connection with the natural environment and an ability to laugh, all

directed toward achieving a specific task. (Fox & McAvoy, 1995, p. 21)

This definition underscores the dynamics of leadership, but does not reference a specific

or general goal, or end point. Fox and Lautt (1996) stated that when outdoor educators focus on

relationships, they may “discover invisible connections that structure moral practice in the

outdoors” (p. 23). The assertion that relational leadership is inherently a moral process supports

the idea that outdoor leadership focusing on participant well-being is therapeutic.

Understanding that there is profound intimacy and vulnerability (and hierarchy) in

professional counseling relationship, reviewing the ethical code for counselors may improve the

competence level of ethical leaders. The American Counseling Association’s (ACA) (2014)

Code of Ethics presents guidelines and practices that are also relevant to outdoor leaders,

particularly those that are relationally oriented. “Counselors encourage client growth and

development in ways that foster the interest and welfare of clients and promote formation of

healthy relationships” (p. 4). This is aligned with adventure education’s purpose of fostering

personal growth. “Counselors interact appropriately with clients in both developmental and

cultural contexts” (p. 5). They “avoid harming others, are self-aware of their own values and

avoid imposing such values on clients” (p. 5). Awareness of one’s values is central to leadership

effectiveness. “Counselors are prohibited from sexual or romantic “interactions or relationships

32

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

with current clients, their romantic partners, or their family members” (p. 5) for at least five

years from their last professional contact. This speaks to the importance of professional

boundaries held by outdoor leaders. Professional responsibilities for counselors include open

and honest communication, to “practice in a nondiscriminatory manner within the boundaries of

professional and personal competency” (p. 8). Non-discrimination includes the areas of “age,

culture, disability, ethnicity, race, religion/spirituality, gender, gender identity, sexual

orientation, marital status/partnership, language preference, socioeconomic status, or any basis

proscribed by law” (p. 9). Outdoor programming involves individuals from all walks of life;

therefore outdoor leaders should be impartial with those they work with. “Counselors practice

only within the boundaries of their competence, based on their education, training, supervised

experience, state and national professional credentials, and appropriate professional experience”

(p. 8) and counselors are expected to behave “in an ethical, and legal manner” (p. 18). These

points parallel the responsibility of outdoor leaders to operate within legal requirements,

standards, industry common practices, and employer policies and procedures. Lastly, counselors

are expected to address ethical dilemmas with the parties involved, and through supervisors and

professional colleagues. Ethical issues are often addressed in the field with co-workers, or with

management as needed.

The ACA code of ethics exclusively addresses interpersonal dynamics and boundaries

between therapists and clients. A code of ethics for outdoor leaders also needs to address the

ethical issues involved when working in the natural world. Berger (2008) forwarded his ideas

germane to a code of ethics for nature therapy. Berger highlighted issues of physical safety,

appropriate physical challenges, the ethical responsibility for the care of the land, and promoting

ecological stewardship and respect among clients.

33

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

An Ethic of Care

Outdoor leadership theory and outdoor leaders need to be critical examiners of

underlying theories and assumptions that drive practice. A component of healthy relationships is

compassion. Relevant to both the human need for belonging and relational and ethical

leadership, there is an additional theory that may guide how leaders act towards participants to

foster growth: Noddings’ (2002) ethic of care. Articles by McKenzie and Blenkinsop (2006)

and Burke et al. (2012) assert that an ethic of care has an important role in both the theory and

practice of outdoor and adventure education, and can serve as a theoretical foundation for WEPs

to assess the role of care and compassion in programs. Noddings (2002) describes four

conditions that define a caring relationship: one person demonstrates conscious attention and

directed energy towards serving another (needs, goals); this person acts on his or her awareness;

the recipient recognizes the actions as demonstrating care; and the caring person is “consistently

present.”

An ethic of care can guide leaders in how they foster and facilitate relationship formation

and highlights elements present in caring relationships, as well as affirming the best in others

(McKenzie & Blenkinsop, 2006). According to Burke et al. (2012), “An ethic based on care is

one that puts relations and the needs of the other at the center of any moral decision-making” (p.

13). Relationships positively affected by an ethic of care include intrapersonal and interpersonal.

Quay, Dickinson, and Nettleton (2000) wrote, “Caring provides a strategy for meeting our need

for recognition as individuals as well as our need to belong within a community” (p. 7), and that

caring for others meets the human need for belonging to community. “With care theory as a

foundation, caring for individuals is never set aside or secondary in effective leadership” (Burke

34

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

et al., 2012, p. 10). This perspective acknowledges the human need for relationships and situates

caring as central to effective leadership.

Caring is acknowledged as a crucial element of leadership. Burke et al. (2012) wrote,

“The purpose of the caring relation is to promote growth, prevent harm, and meet the needs of

the other” (p. 5). Expanding the notion of the “other”, McKenzie and Blenkinsop (2006)

described how teaching low impact camping techniques and environmental ethics demonstrates

an ethic of care towards the natural world. One element of moral education is confirmation,

which “involves looking for the best in the acts of an individual and affirming and encouraging

that part of their actions which one believes is good and has good intentions” (Quay et al., 2000,

p. 10). This is akin to positive psychology, which is a growth-oriented therapy model where

individual strengths and positive traits are emphasized rather than focusing on individual

problems and deficits (Berman and Davis-Berman, 2005). Positive psychology asserts human

development is best facilitated through “leveraging natural talents rather than merely remediating

his or her weaknesses” (Passarelli, Hall, & Mallory, 2010).

Care can be applied across a broad spectrum of intentions. A leader can care about and

emphasize the physical safety of those he or she leads. A leader can care about and emphasize

the learning of those he or she leads. Or, a leader can care about the overall well-being and

personal development of those he or she leads. A caring outdoor leader encourages personal

development through adventure and nature-based experiences and teaching environmental ethics,

philosophy, and nature dominated psychological theories to build relationships within people,

between people, and with nature. McKenzie and Blenkinsop (2006) acknowledged that

adventure education curricula often addresses issues of interpersonal communication, group

process issues and development, and environmental stewardship. They conclude that an ethic of

35

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

care should address care for self, others, and the natural world. This conclusion embodies the

values and practices of therapeutically oriented outdoor leaders. Thus, a tripartite relational

matrix is already integrated in adventure education, but the domains of these three relationships

may not be explicit identified or addressed in relevant literature.

Emotional Intelligence

Outdoor leadership education, research, and competencies often address concepts such as

interpersonal skills, communication skills, judgment, and decision-making. A more integrated,

and possibly more useful construct is emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence is a

wholistic construct that has more recently been explored in the context of leadership generally,

and outdoor leadership specifically. Mayer and Salovey (as cited in Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso,

2004) define emotional intelligence as:

the capacity to reason about emotions, and of emotions to enhance thinking. It includes

the abilities to accurately perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions so as to

assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively

regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth. (p. 197)

Hayashi and Ewert’s (2006) research found that higher levels of emotional intelligence were

positively related to the level of the leader’s outdoor experience. Because the concept of

emotional intelligence includes intrapersonal, interpersonal, and situational elements, Hayashi

and Ewert (2006) suggested it is a useful framework for researching outdoor leaders. Martin,

Cashel, Wagstaff, and Breunig (2006) affirmed this point, when they stated that emotional

intelligence is “important to outdoor leaders in understanding the motivations, attitudes, and

behaviors of program participants” (p. 127). Hayashi and Ewert (2006) explained that research

suggests there is a relationship between transformational leaders and emotional intelligence,

36

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

while Palmer, Walls, Burgess, and Stough (2001) found preliminary evidence that there is a

relationship between effective leadership and the emotional intelligence of leaders. Mayer et al.

(2004) explained, “emotional information processing is an evolved area of communication

among mammals…[which] involves understanding of relationships among people and, to a

lesser extent, animals” (p. 199). Individuals with higher levels of emotional intelligence have a

greater ability for relatedness, to communicate motivating messages, to better perceive emotions

and understand their meaning, and manage emotions, which result in openness and agreeableness

yielding higher levels of cooperation (Mayer et al., 2004). Considering the research that links

emotional intelligence to effective and transformational leadership, it seems logical to emphasize

emotional intelligence within a relational framework of outdoor leadership.

Self-Awareness and Values

Self-awareness is required for leaders to effectively foster well-being and relationships.

Connecting self-awareness to emotional intelligence, Sosik and Megerian (1999) stated that self-

awareness is the theoretical foundation of emotional intelligence. Referencing the work of

renowned psychologist, Carl Rogers, Thomas (2008) extrapolated the importance of self-

reflection by person-centered therapists, to facilitators, and makes a covert reference to

countertransference. He wrote, “facilitators must be aware of, understand, and be able to manage

their internal reactions to their participants, especially in challenging situations” (p. 180). For

Thomas, an effective outdoor leader is one who is educated in what he described as person-

centered outdoor leadership education. He described person-centered leadership education as

“content focused on the attitudes, personal qualities, or self-awareness of the outdoor leader”

(Thomas, 2011, p. 6). In an earlier paper, Thomas (2008) described person-centered facilitator

education approaches as being intentional, emphasizing “the attitudes, personal qualities, or

37

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

presence of the facilitator” (p. 170) as well as being “focus[ed] on… the interpersonal

relationships between the facilitator and group” (p. 170). Thomas’ (2008) research into skills

needed by facilitator educators include “high levels of self-awareness and self-management” (p.

184) as well as “better understand[ing] their relationships with groups and their presence in the

group” (p. 184). Passarelli et al. (2010) highlighted the critical element of self-reflection by

outdoor leaders when they suggested instructors “would benefit from a deep understanding of the

patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior that their own unique strengths produce” (p. 131). Fox

and McAvoy (1995) declared that self-awareness and self-assessment are aspects of ethical

outdoor leadership, while Sosik and Megerian (1999) found in their corporate research that

leaders with high levels of self-awareness exhibited higher levels of “personal efficacy,

interpersonal control, and social self-confidence” (p. 384).

Values are an important focus area of self-awareness. Each outdoor leader brings to her

or his facilitation underlying assumptions and work related experiences that shape the leader’s

intentions. It is essential for outdoor leaders to be cognizant of their values, filters, and held

paradigms, for leaders consciously and subconsciously teach these perspectives to others.

Values research within the field of psychotherapy has found that “therapists hold important

values in actual practice, but they also inevitably seek to persuade their clients to hold them”

(Slife, 2004, pp. 172-173). This supports the assertion that leadership is inherently a process of

influence. Fox and McAvoy (1995) wrote, “It is important for the outdoor leader to understand

her or his values or ethics and how those ethics shape his or her decisions and behavior” (p. 21).

Slife (2004) and Fox and McAvoy (1995) have highlighted the reality that we are

subconsciously, yet actively persuading those around us to adopt, in some form, our own values

or to mimic our decision making processes. Schumann et al. (2009) explored instructor

38

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

influences on transfer of learning, and found that expressed leader behaviors could not be

separated from who the instructor is. Hamachek (1999) provided an illuminating quote

regarding self-awareness and leadership: “Consciously, we teach what we know; unconsciously,

we teach who we are” (p. 209). This notion of “teaching who we are” is topically explored in

this thesis survey.

Besides instructor values, there are values inherent within outdoor programming goals.

Fox and Lautt (1996) stated that “the common ground between outdoor recreation, outdoor

education, environmental education, and experiential education can be found in a value base of

respect, social responsibility, self-actualization, justice, and freedom for all living beings and the

Earth” (p. 19). Raiola (1997) asserted that adventure educator academic curricula should cover

the topic of values including care and respect for oneself, respect and acceptance of others, and

respect for nature. The points outlined in this section situate self-awareness, including values

awareness, as necessary for relational leaders.

Outdoor Leadership and Relationships

Competency Approaches to Outdoor Leadership

Outdoor leadership theories and practices have been defined, and are continually refined,

as research provides information that can improve leadership efficacy, better facilitate desired

outcomes, and enhance the training of leaders. Past discussions and research on outdoor

leadership have often focused on models of competency. Often cited works by Buell (1981),

Swiderski (1981), and Priest (1984) among others, attempted to name and categorize skills

essential to outdoor leadership. Competency models imply a level of objectivity and consistency

across WEPs, that outdoor leaders approach their duties and responsibilities with similar

perspectives. In contrast, Thomas (2008) highlighted the subjective nature of group facilitators,

39

AN ASSESSMENT OF THERAPEUTIC SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

stating that a leader’s interpretation and assessment of their group is rooted in the subjectivity of

perception, stemming from differences in feelings, thoughts, and intuitions, but does not mention