International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Article

Designing Multifunctional Urban Green Spaces: An Inclusive

Public Health Framework

Andrew J. Lafrenz

School of Nursing & Health Innovations, University of Portland, 5000 N. Willamette Blvd,

Portland, OR 97203, USA; lafrenz@up.edu

Citation: Lafrenz, A.J. Designing

Multifunctional Urban Green Spaces:

An Inclusive Public Health

Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res.

Public Health 2022, 19, 10867.

https://doi.org/10.3390/

ijerph191710867

Academic Editor: Paul B. Tchounwou

Received: 6 August 2022

Accepted: 28 August 2022

Published: 31 August 2022

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Copyright: © 2022 by the author.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

Abstract: Evidence of the wide range of health benefits associated with the use of urban green space

(UGS) continues to grow. Despite this evidence, many UGS designs do not adopt a community-

inclusive approach that utilizes evidence-based public health strategies to maximize potential health

benefits. This research focused on testing a multidisciplinary, community-involved public health

framework to drive the UGS design process. The aim of this study was to use community feedback

and evidence-based public health practices to promote physical health, psychological wellbeing, and

social cohesion by creating a multifunctional UGS that enhances nature therapy, natural play, and

sports and recreation. Community health assessment data (236 survey responses), community forum

and survey feedback (157 survey responses), local urban green space inventory assessment, and

environmental assessment and impact data were analyzed to develop a design plan that maximize

the greatest potential health benefits for the greatest proportion of the population. Community health

data indicated a strong relationship between the availability of places to be physically active in the

community and higher ratings of mental (aOR = 1.80) and physical (aOR = 1.49) health. The creation

and utilization of the proposed community-inclusive and public health-focused framework resulted in

a UGS design that prioritized the needs of the community and provided evidence-informed strategies

to improve the health of local residents. This paper provides unique insight into the application of a

framework that promotes a more health-focused and functional approach to UGS design.

Keywords: urban green space; nature and health; forest therapy; urban design; multifunctional

green space

1. Introduction

As the population density increases in many cities around the world, urban green

spaces (UGS) become increasingly important as areas to promote a wide range of health

benefits. The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that urban green spaces are

a “necessary component for delivering healthy, sustainable, livable conditions” and have

urged urban planning to include more evidence-based public health approaches [1]. The

scientific research overwhelmingly supports the substantial and growing evidence of the

influence green spaces has on multiple aspects of physical and psychological wellbeing.

As proposed by Veen et al. [2], the majority of health benefits that UGS help promote can

generally be grouped into three distinct categories of health benefits: (1) physical health,

(2) psychological wellbeing, and (3) social cohesion [2]. The benefits to physical health are

supported by studies that show an association between greater exposure to green spaces

and parks and higher levels of physical activity in children and adults [3,4], lower levels

of obesity in children and adults [5,6], improved sleep quality in adults [7], decreased

cardiovascular disease incidence [8,9], and decreased Type 2 diabetes incidence [10]. The

benefits to psychological wellbeing are supported by studies that show higher levels of

green space exposure to be associated with improved mental wellbeing, overall health,

cognitive development in children [11], lower psychological distress in teens [12], and

lower risk of a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders later in life for those with higher

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710867

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, x

2 of 15

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2c0o2g2,n1i9t,iv10e86d7evelopment in children [11], lower psychological distress in teens [12], an2dof 14

lower risk of a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders later in life for those with higher

levels of continuous green space presence during childhood [13]. In addition, studies have

indilceavteelds tohfactotnimtineusopuenstgirneefonrespstascies parsesosecniacteedduwriitnhglocwhieldr hcooortdiso[1l3l]e.veInls a[1d4d]itainodn,astrue-dies

duchtiaovneiinnrdeipcaotretdedthfeaetltiinmges ospf ehnotstiniliftoyr,edsetsprisesassisoonc,iaanteddawnixtihetlyowamerocnogrtaidsoulltlesvweiltsh[1a4c]uatend a

andrechdruocntiiocnstirnersesp[o1r5t]e.d feelings of hostility, depression, and anxiety among adults with acute

anDdescphirtoenoiuc rsturnesdse[r1s5ta].nding of the importance of green spaces to human health, green

space is Dunesdpeirteinocurreausnidngerpstraensdsuinrge ofrfotmhegimropwoirntganucreboafngpreoepnuslaptaicoensstoanhdumthaenahsseoacltihat,egdreen

urbaspnaizcaetiiosnupnrdoecreisnscerseoafsienxgpapnresisosnuraenfdrodmengsrifoiwcaitniognu[r1b6a]n. Wpoitphutlhaetiaovnasilaanbdletghreeaesnsoancidated

blueusrpbaanceizsadteiocnrepasroincgesisnems oafneyxcpoamnsmiounniatnieds,dtehnesiimficpaotriotann[c1e6o].f W maitxhimthiezianvganilaatbulreagl raereenasand

andbpluaerksspfaocresthdeeircrheeaaslitnhgainndmwanelylnceosms mbeunneiftiitesss,hthoeulidmbpeoratapnrcioeroitfym. Waxhimenizlionogkinnagtuartatlhaereas

pathawndaypsairnkws fhoirchthUeGirShaefafletcht haneadltwh,etlhlneebsesnbeefintesfihtasvsehboeuelndabtetriabuptreiodrtioty:.(1W) bheeinnglopohkyisn-g at

icalltyheacptaivthewinaynsatinurwe hoirch(2U) bGeSinagffpecret sheenatltihn, nthaetubreen. Hefiotws hevavere, btheeenchaattrraibctuetreisdtitcos: o(1f )thbeeing

spacpehiytssieclaf lilsyaalscotivinefliunennacteudrebyorit(s2f)ubnecintigonparleitsyen[1t7in]. nHaotwurea.nHd owwitehvwerh, tohme c(eh.agr.,aacltoenriestoicrs of

withthoethspearsc)eiintsdeilvfiidsuaalslsouinsfle utheencUedGSbyalistos fiunnflcuteionncaelitys p[1o7t]e.nHtioawl baendefwitsit[h2]w. hom (e.g., alone

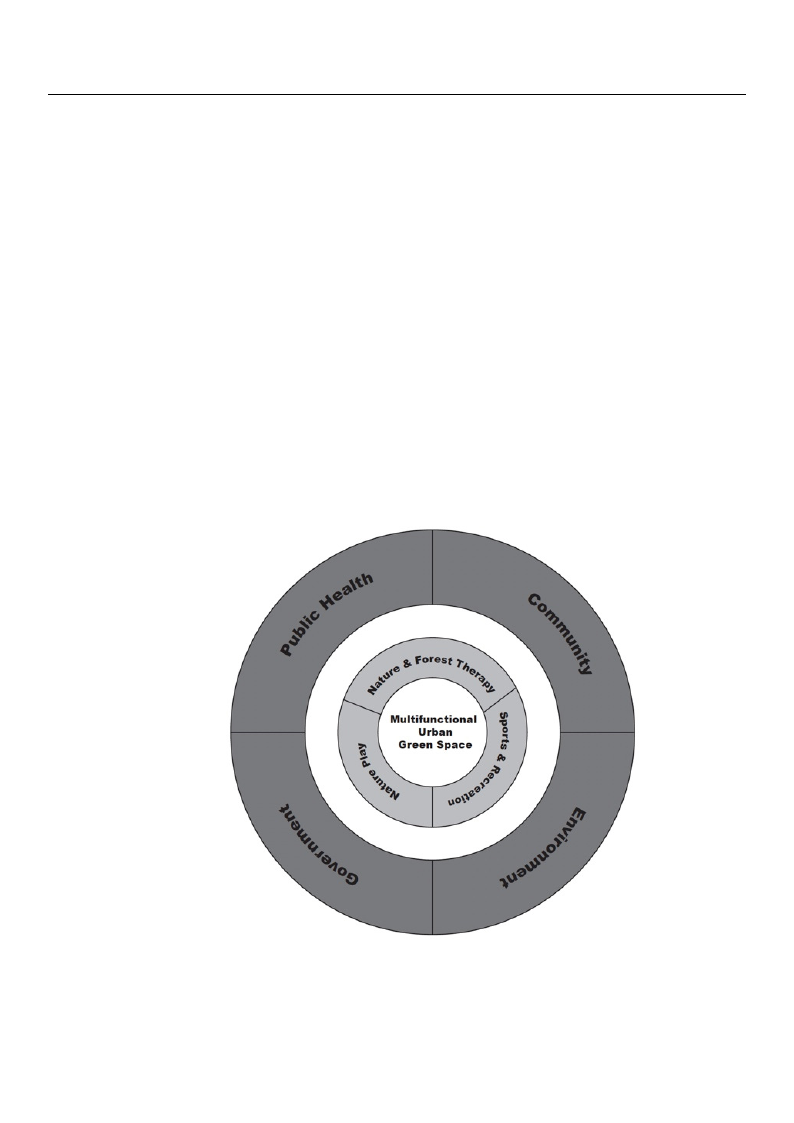

orThwiisthpaoptheerrws)iilnl dpirveisdeunat las ucasseethsteuUdGy Sonalsthoeinufltiulieznacteiointsopfoatemntuialtlidbeisnceipfiltisn[a2r]y. urban

green spTacheisdpesaipgenrfwraimll epwreosrekn(tFaigcuarsee 1s)tuthdayt oinncltuhdeeustfioliuzartciomn pofonaemntusl:t(i1d)islocicpalingoarvyerunr-ban

mengtreoeffnicsiaplasc, e(2d) elosciganl cformammeuwnoitrykm(Feimgubreers1,)(3th) alotcianlcpluudbeliscfhoeuarltchopmrpofoensesniotns:al(s1,)alnodca(l4)gov-

locaelrennmveirnotnomffiecnitaalsl ,e(x2p)elortcsa.lWcohmilemruenseitayrcmhermsbceornst,in(3u)elotocaflopcubs loicnhtheaelthheaplrtohfebsesnieofnitaslso,fand

bein(4g)aloctciavleeannvdiropnrmeseennttailnexnpaeturtrse.,Wlithtlielerreesseeaarrcchhehrasscfoonctuinseude toonfohcouws opnubthliechheeaalltthhbsecnieenfi-ts of

tistsbaeinndgaacdtiverasnedrepprerseesnent itnatnioantuoref ,lolicttallecroesmeamrcuhnhitaysmfoecmusbeedrsoncahnowoprukbcliocllhaebaoltrhatsicvielnytists

withanudrbaadnivpelarsnenreerpsrteosednetvaetilonp ohfelaolcthailecro, mmmoruenliitvyamblem, abnedrsmcaonreweonrvkircoonllmabeonrtatlliyvesluysw- ith

tainuarbbleancopmlamnnuenristiteos.dTehve lroepsehaeraclhthqiuere,smtionrecleinvtarballet,oanthdismsoturedyenwvairso: ncmanena tcaollmy msuusntaitiyn-able

inclcuosmivme,upnuitbileisc.-hTehaeltrhe-sfeoacrucsheqdudesetsiiognncfernatmraelwtoorthkisimstpurdoyvewtahse: cmanulaticfoumncmtiuonaitlyit-yinaclnudsive,

therpeufobrleict-heapltoht-efnotciualsehdeadlethsigbnenferafimtseowf oarnkuimrbpanrogvreetehnesmpaucleti?functionality and therefore the

potential health benefits of an urban green space?

Figure 1. Proposed multidiscipline, multifunctional urban green space design framework.

Figure 1. Proposed multidiscipline, multifunctional urban green space design framework.

1.1. The Problem

Despite the growing evidence of the relationship between green spaces and a variety

of health benefits, urban planners rarely design multifunctional spaces that can provide all

three distinct health benefits related to improving: (1) physical health, (2) psychological

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

3 of 14

wellbeing, and (3) social cohesion in the same space. The historical model in the U.S.

has been for local governments to make smaller green spaces available in traditional

neighborhood parks with sports fields, bike paths, playground structures, and picnic

tables. Alternatively, larger green spaces are often set aside as natural areas with little to no

infrastructure and a focus on allowing individuals to be in nature. As such, these different

types of green spaces typically target specific populations depending on their amenities.

For example, parks primarily designed with playground structures are mostly visited by

families with young children. Parks with sports and athletic fields are mostly visited by

older children and adolescents. Lastly, nature areas are primarily visited by older adults.

Less common, is the design of green spaces that function as: (1) natural play structures

for young children, (2) sports and athletic fields for school-aged children, and (3) areas

that provide nature and forest-therapy features for all ages. With a body of research now

shedding light on the multiple pathways by which green spaces and parks can affect our

health [18,19], urban planners have yet to adopt strategies that consider these multiple

pathways. Creating multifunctional green spaces would maximize the potential health

benefits for the greatest number of individuals in a community. Ensuring that UGS design

maximizes the numerous health, social, and environmental benefits is critical. In order to

accomplish this, urban planners should strive to be more inclusive and invite a greater

number of community stakeholders and public health professionals to the table when

designing green space functionality.

1.2. Aim of the Study

This paper aims to present: (1) a multidisciplinary, community-inclusive green-space-

design framework, and (2) the results of incorporating a public health approach that informs

the design of a green space by maximizing health benefits through multifunctionality.

1.3. Significance of the Study

This paper presents a case study of a multidisciplinary urban green space design

approach and framework that is informed by public health research. To date, much of

the research in the nature and wellness field has focused on providing evidence of the

various health effects in different populations, understanding the health benefit pathways,

or retrospective evaluation of the UGS built environment. Few studies have presented

frameworks for how to create collaborative and effective UGS design teams that can

maximize the evidence-based health benefits of green spaces.

2. Materials and Methods

This case study took place from December 2021 to July 2022. Data were obtained

through community health assessment questionnaires, several community-distributed sur-

veys, publicly accessible planning documents, and interviews with multiple organizations.

Details of the data collection methods are given below. The framework developed was used

to guide a new design approach for an urban green space in the city of Scappoose, in the

state of Oregon in the United States. Scappoose is a small town in Oregon, the United States

of America, with approximately 8010 residents. Traditionally settled as a farming, logging

and fishing town, most residents now commute to work approximately 25 miles away in

Portland, the largest city in the state of Oregon. The town of Scappoose, Oregon provides a

unique case study on multifunctional urban green space design for several reasons: (1) Its

proximity to a large metropolitan area (Portland, OR, USA) and its combination of urban

and rural areas results in elements of an urban layout, but with more available public

green space than many urban areas. (2) The green space involved in this study includes

a significant number of valuable natural green and blue areas, which allows for a unique

design for use as both a park and open natural area. While Scappoose is designated as both

urban and rural (depending on the defining organization and the reason for designation)

for the purpose of this study, the green space will be referred to as an urban green space

more available public green space than many urban areas. (2) The green space involved

in this study includes a significant number of valuable natural green and blue areas, which

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 1a9l,l1o0w86s7 for a unique design for use as both a park and open natural area. While Scap4poofo1s4e

is designated as both urban and rural (depending on the defining organization and the

reason for designation) for the purpose of this study, the green space will be referred to

(UasGaSn) udrubeantogirteselnocsaptaiocne (wUiGthSi)ndtuheetcoitiytslliomciattsioanndwwithitihnitnhea cwiteylll-idmeivtselaonpdedwiatrheian oafwtheell-

smdeavllecloitpye. d area of the small city.

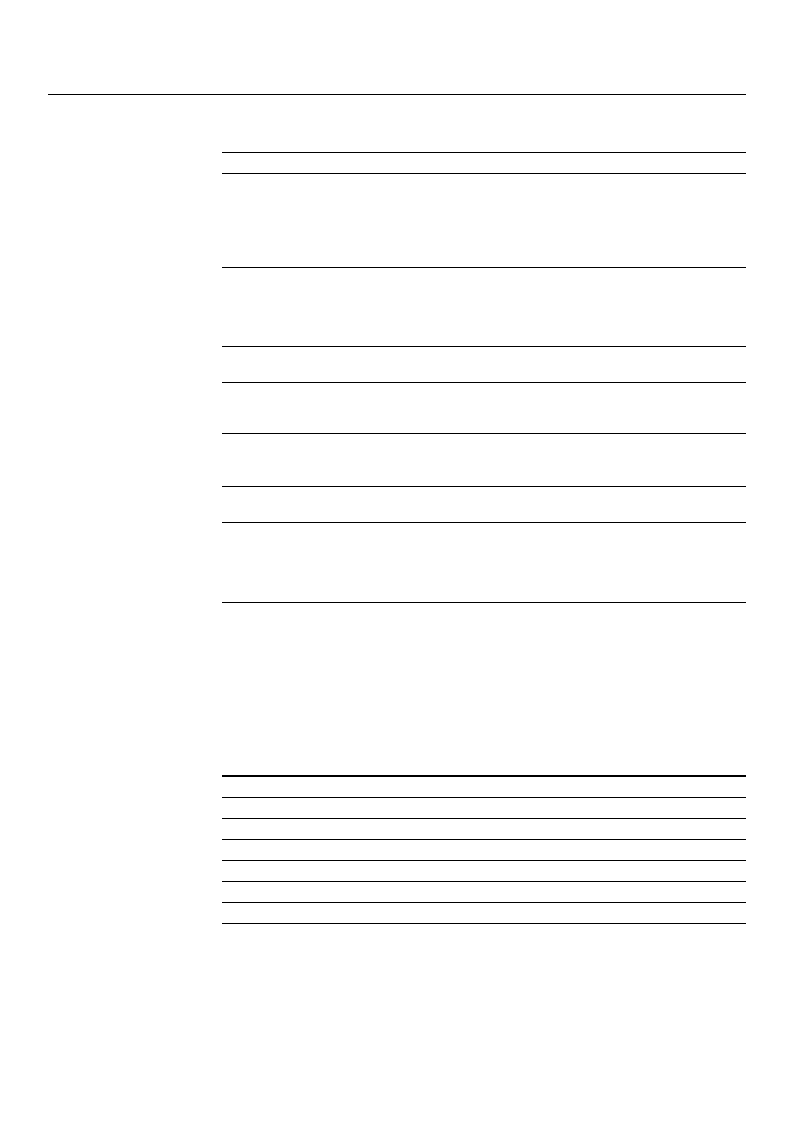

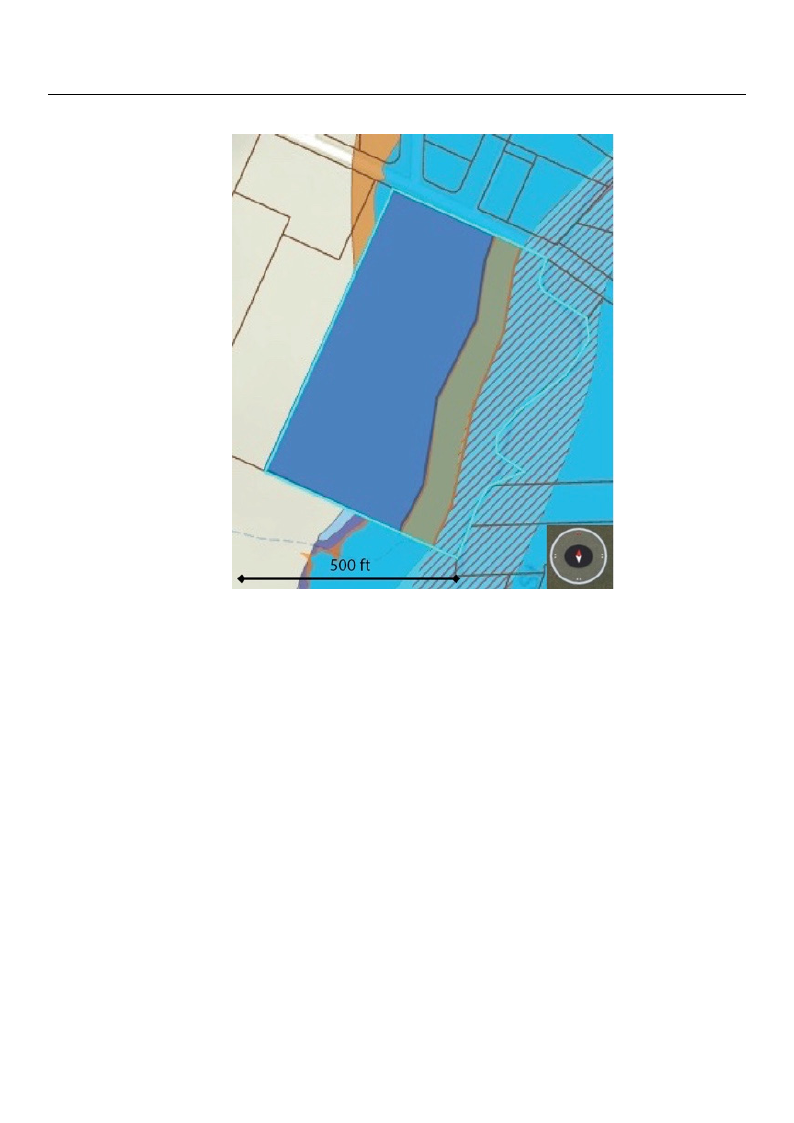

TThheespspeceicfiifcicUUGGSSininclculuddeeddininththisiscacasesestsutuddyyisis99.5.544aacrceressininsiszizee(s(eseeFFigiguurere2)2)anandd

fefaetauturersesa asmsmalal lsltsretraemamthtahtarturnusnasloanlogntghetheeasetaesrtnerbnorbdoerrdoefrtohfetahreea.reTah.eTshteresatmre,akmn,okwnnowasn

thaes SthoeutShoSuctahpSpcoaopspeoCorseeekC(rSeSeCk)(,SisSCan),iims panoritmanptotritbauntatrryiboufttahreySocfatphpeoSocsaepBpaoyoWseatBearsyhWeda,-

wthericsheddr,awinhsiicnhtodtrhaeinCsoinlutmo tbhiae RCiovleurmthbaiat bRoirvdeerrtshOatrebgoorndearnsdOWreagsohninagntodnWinatshheinUgntoitnedin

SthateeUs.nTitheedSSStaCteisn.cTluhdeeSsSsCevinecrlauldeensdsaenvgeerraeldensdpaencigeesroedf fispshecaiensdooftfhisehr afonrdmosthoefrwfoilrdmlisfeo,f

inwcliluddlifneg, icnochluodaindg cohhinooaonkdscahlminoono,kasnadlmstoene,lhaneaddstaenedlhceuatdtharnodatcutrtothurto. aEtxttreonusti.vEexetfefnosritvse

heafvfoerbtseehnavme abdeentomraedsteotroe rtehsetomreanthyecmreaenkys carnedekws atnedrwwaaytserwwiathysinwtihtheiSnctahpepSocoaspepBoaoyse

WBaatyerWshaetderdsuheedtodthue itmo pthoertaimncpeoorftatnhceesaolfmthoen shaalbmitoant ahnadbiwtaattearnqduwalaittye,raqnudailnityo,rdaenrdtoin

moirtdigeartetothmeitiingcarteeasthinegilnycfrreeaqsuinegnltylofrceaqlufleonotdlioncgalefvloenotdsi.ng events.

Figure 2. The undeveloped UGS boundaries and layout. (Google Earth 7.3, (2022) Scappoose Public

FGhGirgteruteeprne:e/nS/2wp. awTSchpwee,a.4cgue5on,◦od4g5el4ve35e.6c°l4oo5mpN′e3/d6e1″a2Ur2tG◦hN5/Si2nb5do51eu2xn2.Wdh°5ta,m2rei′5lele5s[va″aacntcideoWsnlsa,e1yd3oeouMlnte..v3([aGO0tionJouolnilgnylee2]10EA32av2r]at)hiM.la7.b.3le, [(aO2t0n:2lh2int)tepS]:c/a/pAwpvowaoiwslea.gbPolueobgllieac.t:

com/earth/index.html [accessed on 30 July 2022]).

pdtoteodflcsnreoropeoshemntcsimashageugicOvgengnese-Oerttesnvcfeeii,dovntnreerhafamermgnroonmearanrsmsadlmggdeltpl,rrtlwurpeaa,heeterncrhtwaoteeeeehitterntogs,oeckeryeposiresrh:entkhmeaps(awth:re1aviwmtkae)n(ceoes1alelergut,o)mlte,hrtahncsephlfnaateiiooamrtfxldicygaorumigakptmrturheolrepsaragteiva,gaczeiatiatetcloeaeeeslnrtavstamsntphdistmhentmslsohreatiesnmtreetnsmmhahmnastnpeihmaltulaiteasatncohxlnecttopgbfiinttimfimfb,rlmtuaaoc(or,im2sninoupzfias)dfncueaglueiatsecicgshintninpotshfhatigotmniuteltitnyc,safbh,tuemy(lthle2f(nhsiipo3in)ecueter)cri,agdlhroutocaieipdpmoooswfacueueemnwolendrntnbmathlmntcloisuiieotsmufccuunisnycaornhniiuiolaneqnlieinflbnotqauagayitltcluntleehi,atympsedeh(helt3rpexege(uosl)ataaxparcpshasrenlpieetekeueecdhrernpsnoratrtaitoomutiaussieiblunstepssismhltcetdeeatcoyo(ocuotthrprfeohaenm)teotenchifihatlntreodhiealeyecscteoua,hyUlugporttaUsdriahGonanoeereGougnddneSkrr-tdnSs)-

coamndmriettcereeathtiaotnfoccoumsemditotenegtahtahterfoincgusceodmomnugnaittyheferiendgbaccokmomnuwnhitayt fleoecdalbraecskidoenntws hwaatnltoecdal

threesgidreeenntsswpaacnetetdo itnhcelugdreee, nansdpa(4ce) atoloicnaclluednev,iraonndm(e4n) taallgocroalupentvhiartonfomcuensetadl ognrosutrpeathmat

hfaobciutasterdesotnorsatrtieoanmahnadbflitoaotdrepsltaoirnatiimonpraonvdemfloeondtspinlatinheimgrpereonvsepmaecne.ts in the green space.

2.1. Demographics

Demographic data were obtained from the 2021 U.S. Census Report [20]. The median

age in Scappoose is 41.3 years of age and, compared to both the United States and the sur-

rounding county, Scappoose has a higher proportion of children (aged 14 years and under)

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

5 of 14

and working-age adults (aged 25 to 44 years). The population includes 26% under 18 years

of age and 18% over the age of 65 years, and 37% of all households have children under the

age of 18 living with them, which is higher than both the surrounding county (34%) and

the State of Oregon (30%). The average household size is 2.56 persons—also larger than the

surrounding county (2.55) and Oregon State (2.47). Race and ethnicity demographics are:

87% white (non-Hispanic), 1% Asian, 2% American Indian, and 8% Hispanic.

2.2. Framework Variables

2.2.1. Public Health Level

Data on health-related variables for local residents were obtained from a secondary

dataset that was part of a larger tri-county community health assessment, completed by

multiple counties and a health system, in the spring of 2022. The survey was modeled

after the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance

System (BRFSS) which assesses health status, health risk behaviors, and healthcare access

and utilization. The BRFSS is a well-established survey with strong validity and reliability.

Electronic links to the surveys were posted on social media and included in newsletters,

with a total of 236 responses collected and analyzed for this study. Health-related variables

analyzed in this study included: the prevalence of chronic disease, perceived physical and

mental health, depression and anxiety, social isolation, and perceived community physical

activity options. Obesity rates were obtained from publicly available Behavioral Risk Factor

Surveillance Systems (BRFSS) survey data for the year 2018 (CDC, 2022).

2.2.2. Community Level

Community data were collected over the course of 18 months in several different

formats. Three surveys were distributed electronically on social media, in newsletters, and

in-person over this period to collect feedback on local parks and green spaces. Included

were questions about how likely respondents were to use different amenities, such as

athletic fields, playgrounds, dog parks, and nature trails, in this specific green space.

In addition, several community forums were held where local residents could provide

feedback to local officials about how they would like to see the green space designed. Lastly,

local residents were also encouraged to attend monthly city council and park and recreation

committee meetings to provide feedback on the design of the green space.

2.2.3. Environmental Level

As part of the pre-planning for this green space, an extensive environmental assess-

ment was completed by the local watershed council and external environmental consultants.

From an environmental standpoint, this green space contained several critical environmen-

tal components that needed to be considered. The presence of a stream running the entire

length of one side of the space required extensive flood-plain mitigation planning and en-

dangered fish species habitat planning, as well as wetlands identification and preservation.

2.2.4. Government Level

Local government design input included providing data that were focused on how

the green space contributed to the long-term planning and development of the city. Data

on the current park and green space inventory in the city were collected from the publicly

available 2017 Scappoose Parks, Trails, and Open Spaces Plan. The report included valuable

data on the current inventory of parks and green spaces, as well as undeveloped public

land, for future park and green-space development. The local government also provided

information on how the city master plan and future infrastructure improvements might

affect the UGS design.

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS® for Windows® version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for

data analysis. Bivariate relationships were explored using Pearson correlations. Logistic

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

6 of 14

regression analysis was performed, and models produced to determine community in-

dicators as predictors for high vs. low mental health and high vs. low physical health.

Independent variables with a p < 0.05 in the bivariate analysis were included in the logistic

regression model testing.

3. Results

3.1. Public-Health-Level Data

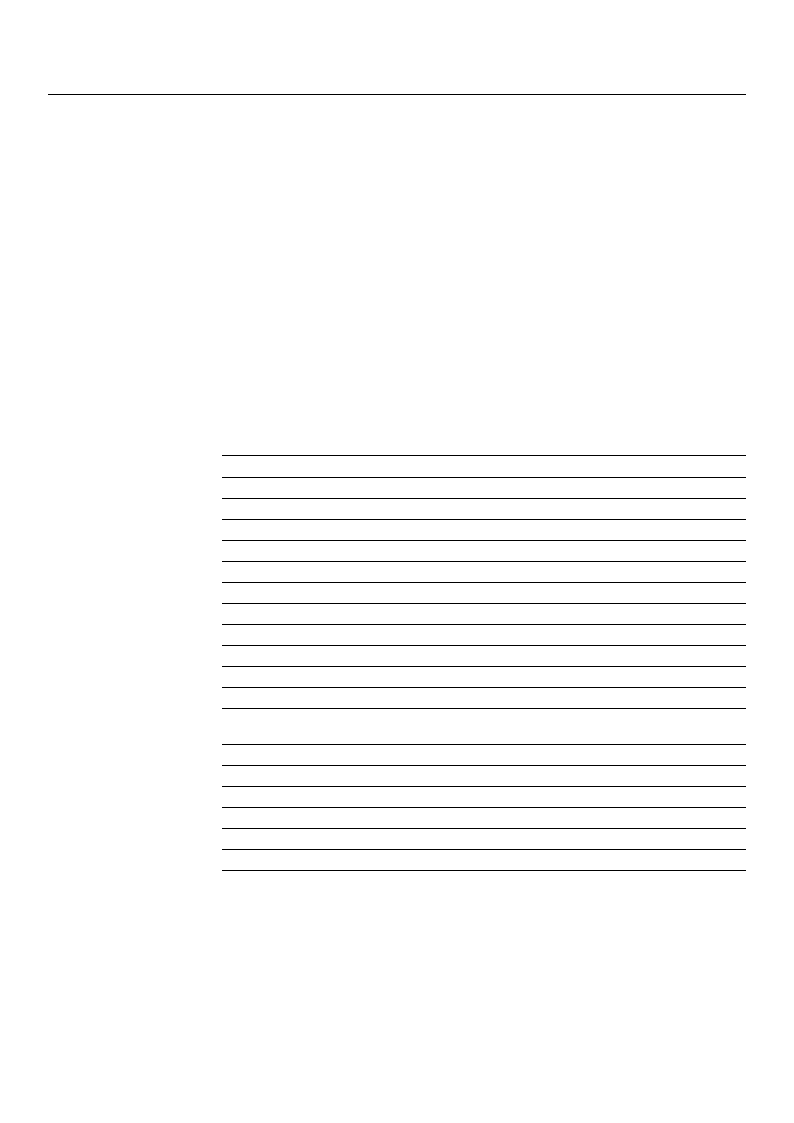

Demographic data are reported in Table 1 and general community health indicators

are summarized in Table 2. Of note are the relatively high number of residents that reported

two or more health conditions (60%), as well as 39% of residents reporting having anxiety

or depression or both. Overall, 72% of Scappoose residents rated their mental health as

good, very good or excellent (compared to 71% in the surrounding communities) and

76% rated their physical health as good, very good or excellent (compared to 80% in the

surrounding communities). The prevalence of obesity among adults aged 18 years and

older was 33% in the Scappoose community, with the same levels found in the surrounding

communities. A relatively high percentage of the population reported that there were

options for community physical activity (77).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents (n = 236).

Characteristics

n

Age

18–40 years old

71

41–64 years old

130

65 years old and over

35

Gender

Female

146

Male

73

Non-binary/other

17

Race

White

191

Multiracial

17

American Indian

Alaskan Native

3

Asian

3

Black/African American

2

Other or Unknown

24

Household makeup

HH w/children < 18 yo

116

HH w/adults > 65 yo

88

Percent of Sample

30%

55%

15%

62%

31%

7%

81%

7%

1%

1%

1%

10%

49%

37%

Significant moderate correlations (r = 0.41–0.46) were seen between indicators of

community livability, such as “my community is a good place to raise children” or “grow

old”, and it “feels safe” and there are “places to be active nearby” (Table 3). Other Pearson

correlation tests indicated significant low to moderate (r = 0.22–0.43) correlations between

various physical and mental health indicators and having places to be physically active

nearby (Table 4).

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

7 of 14

Table 2. Community Health Indicators (n = 236).

Self-Reported Health Indicators

n

Good physical health *

179

Good mental health *

170

Anxiety or depression

91

Cardiovascular risk factors

92

One or more health issues

175

Two or more health issues

142

* Responded as “good”, “very good” or “excellent”.

Percent of Sample

76%

72%

39%

39%

74%

60%

Table 3. Correlations between community livability indicators and places to be physically active in

the community.

My community is a good place to raise children

My community is a good place to grow old

My community feels safe

* p < 0.01.

There Are Places in My Community to Be

Physically Active

0.46 *

0.41 *

0.42 *

Table 4. Correlations between health indicators and places to be physically active in the community.

Physical health rating

Mental health rating

Feeling loved and wanted

Feeling socially isolated

Feeling down, depressed, hopeless

* p < 0.01.

There Are Places in My Community to Be

Physically Active

0.22 *

0.32 *

0.43 *

0.31 *

0.29 *

Final logistic regression models indicated a significant association between perceived

places to be physically active in the community and physical health (aOR = 1.49) and mental

health (aOR = 1.80), as shown in Table 5. No other independent variables were found to be

significantly associated with physical and mental health, and therefore were not included

in the final model as predictors. The final model was adjusted for age, gender, and race.

Table 5. Relationship between independent predictor “there are places to be physically active in my

community” and mental and physical health ratings.

Health Outcome

Mental Health Rating

High

Low

Physical health rating

High

Low

Crude OR (95% CI)

1.74 (1.28–2.37)

1

1.51 (1.11–2.02)

1

Adj OR (95% CI)

1.80 (1.26–2.56)

1

1.49 (1.06–2.08)

1

3.2. Community Level Data

Community feedback related to features that should be prioritized in the development

of the new green space included 157 survey responses from community residents, and is

summarized in Table 6. Overall, the survey responses strongly indicated that the availability

of more nature trails and open spaces was a priority of the community. In addition, there

was a strong response from the local soccer and softball community advocating for sports

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

8 of 14

fields that could accommodate both sports. The community also ranked their top two

recreational priorities as (1) walking and biking for exercise and (2) enjoying the outdoors

and nature.

Table 6. Community Green Space Survey (n = 157).

Question

n

The development of parks is important to me

146

I would support more trails in Scappoose

127

Scappoose parks do not meet my needs

113

Parks are important when choosing where to live

133

Percent of Responses

93%

81%

72%

85%

3.3. Environmental-Level Data

The local watershed council submitted a full stream restoration proposal to the city

in May of 2022. A full description of the environmental component is not included, as

the details of the plan fall outside the scope of this study. However, a summary of the

environmental assessment and design plan will be discussed briefly due to its importance

in developing the public health-focused design of the remaining green space. The environ-

mental proposal was primarily used to help provide details on design constraints relating

to the stream bank lay-back, and where a transition to the more traditional park amenities,

such as play structures, athletic fields, and picnic tables, could occur. State and federal

environmental regulations protect a large riparian buffer zone near the stream. However, a

balance was achieved by designing a nature-therapy-focused trail, as well as several areas

that provide access to and interaction with the green and blue areas around the creek.

3.4. Government- and Urban-Planning-Level Data

Data from the most recently completed parks, open spaces and trails report indicate

that Scappoose currently has 2.93 acres of parkland for every 1000 residents. In comparison,

the National Recreation and Park Association has established their benchmark for the level

of service for a community to be 6.25–10.5 acres of parkland for every 1000 residents. The

addition of this UGS will increase that ratio to 3.75 acres of parkland for every 1000 residents,

moving Scappoose closer to the established national guidelines. The development of this

UGS will also increase the number of residents that are within a walking distance of

five miles to a park by an estimated 220 residents. Lastly, there is currently no park or

green space within the Scappoose city limits that is designated as a natural open area.

Additionally, the park and green space inventory indicated a disproportionately lower

number of structures designed for under-2 year olds and the 2–5 year old age group.

Sensory-friendly playground structures that are more accessible for children with autism

and other challenges were also notably not present in this community.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Multifunctional Green Space Design Plan

The extensive work completed by the four components of the framework resulted

in a comprehensive multifunctional UGS design proposal, which was submitted to the

city. The purpose of this paper was to use this case study to provide insight into the

application of this framework, including the strengths and challenges of a multidisciplinary

team working on a community-involved, public-health-informed UGS design approach

for improving health in the community. The scope of this article is not to provide details

of the full UGS design plan, due to the variability and local context of each unique green

space. However, an outline of the design elements will be discussed in the context of

involving community members, public health professionals, and local city planners, as well

as environmental experts. The main components of the proposal included an environmental

habitat and stream restoration plan, athletic and sports fields and facilities, natural play

zones, and a nature-therapy-focused path along the stream. These four main components

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

9 of 14

of the UGS will maximize the potential health benefits through multifunctionality. The

design was intended to provide health benefits by targeting opportunities to be active in

nature, experience and interact with nature, and engage in social interactions in a park and

natural area.

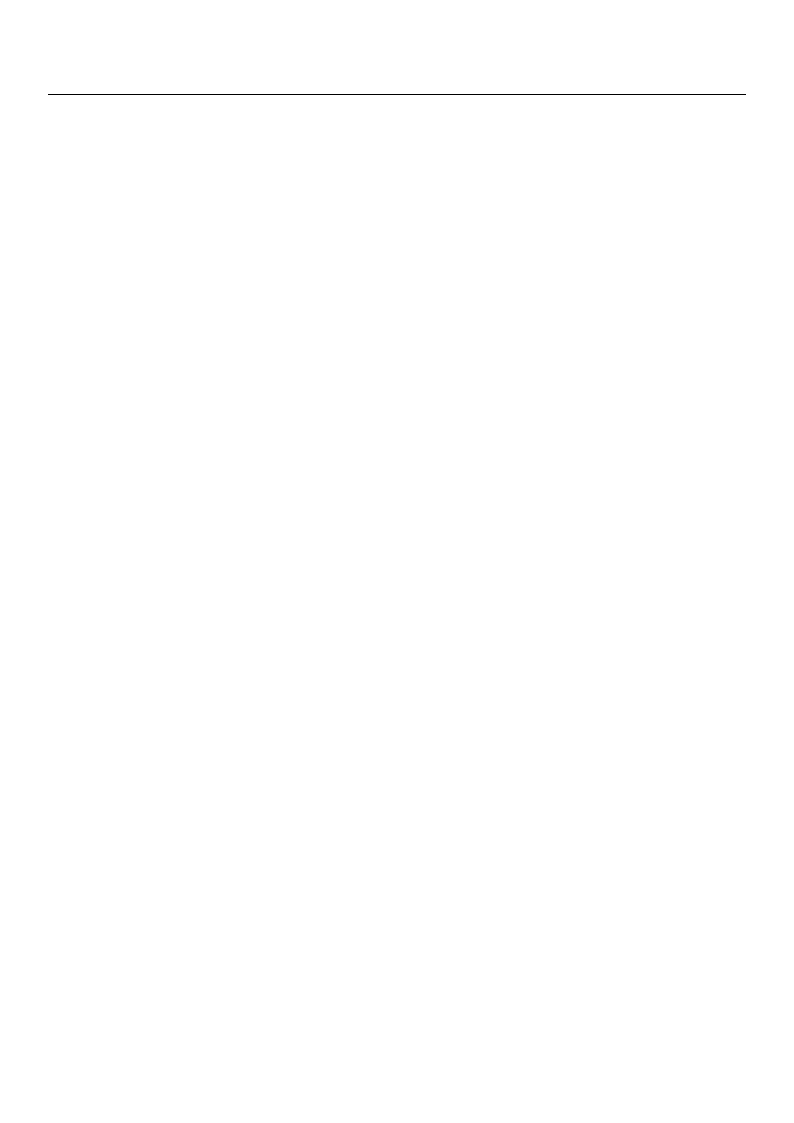

The completion of the environmental assessment and stream restoration plan was

essential for understanding how much of the 9.54 acres would remain after restoring

the natural flood plain. The original creek bank will be laid back to the required FEMA-

designated regulatory floodway, as shown in Figure 3. As a result, approximately 2.2 acres

along the creek will be set aside as a protected natural area. It is essential that future

UGS design not only include improvements to the natural areas for habitat restoration

and biodiversity, but also should include provisions for future climate-change-related

health impacts. For example, in this green space design, significant benching of the creek

bank will be completed in order to alleviate the increasingly more frequent flood events

and associated risks to homes, buildings, and other infrastructure. In addition, mature

trees will be preserved, which will help to provide shade and urban cooling as many

areas around the world experience more frequent and more severe heat waves. A zone

of approximately 1.5 acres along the border of the regulatory floodway will provide a

transitional zone, designed for residents to interact with nature. In addition, there will

be two water-access locations for children and adults to have access to the stream. This

transitional zone is an important element in the multifunctionality of the green-space

design. Rather than a hard delineation between protected natural areas and athletic fields

and concrete bike paths, a softer and more inviting wood chip path is proposed; this path

meanders around natural features such as trees, shrubs, and boulders. In addition, natural

play structures are proposed, which combine the necessary water drainage requirements

(bioswales) with additional natural play features for children to enjoy. Recent research

indicates the additive health benefits of natural play for children, compared to traditional

playground use. Brussoni et al. [21,22] found a significant decrease in depression and

aggression post-nature play exposure/intervention, and another study found a positive

increase in mood post-nature play exposure/intervention [23]. Other studies on natural

play have shown improvements in cognitive development [24,25], learning [23,26], and

social outcomes related to nature play [21,23]. Additional features in the transitional

zone will include features intended to facilitate nature and forest therapy, such as natural

boulder and log seating areas. The creation of “nature rooms”, made up of small spaces

surrounded by mature trees and plantings with a high biodiversity and a variety of textures

and colors, will be an important feature that invites individuals to pause and open their

senses to all that nature has to offer. These design elements not only facilitate the formal

sequences involved with nature and forest therapy but also are supported by research that

demonstrates the health benefits associated with higher biodiversity in green spaces [27]. A

dedicated zone that focuses on optimally facilitating nature and forest therapy is a unique

feature of this UGS design. These features draw from the growing evidence of the benefits

of guided nature and forest therapy. The growing practice of forest bathing, or nature

and forest therapy, as it is more commonly known in North America, has highlighted

the benefits of guided experiences in nature. A systematic review by Wen et al. [28] on

the medical empirical research into forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) indicated that there was

growing evidence of a wide range of health benefits, through both physiological effects

and psychological effects [28].

unique feature of this UGS design. These features draw from the growing evidence of the

benefits of guided nature and forest therapy. The growing practice of forest bathing, or

nature and forest therapy, as it is more commonly known in North America, has high-

lighted the benefits of guided experiences in nature. A systematic review by Wen et al.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19[2, 180]86o7n the medical empirical research into forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) indicat1e0doft1h4at

there was growing evidence of a wide range of health benefits, through both physiological

effects and psychological effects [28].

FiFrgiiupgrauerri3ea.n3T.bhTuehffteehrtrhzeroeenUeeGUaSrGozSuonzndoenstehaseraewrseahtseohrwwonwayinn. iOtnhritashnifigsgefuirgreuep.rreDe.siDeangiatosgnotahnleaslntrsaittpruierpseerstehrpeerrpearspeeysnetanntthdtehnpeartpourtreoactletepcdtleady

riptraarniasnitibounffzeornzeo.nBeluaeroruenpdretsheentws athteerwspaoyr.tOs-raanndg-erercerperaetisoenn-tdsetdhiecantaetduraerethae(rCapolyuamnbdianaCtouuranltyp,laOyR,

traUnSsAiti,oGnISzoMnaep. pBilnuge).represents the sports-and-recreation-dedicated area (Columbia County, OR,

USA, GIS Mapping).

partCthhenaoapcmatcaedhromnnoatkea-mcddrmtscnpAtoeh-omdadcgmtmaAfeuhortnarruteefemeleuatdotddrninrepeloaudnniadrgytbntpncoayar-abessyctefi,tcpneutooi-ediyctofaancrunhdo,oenauctcneeuucstelsslshisutunrspgecgiia,eisndodtgrannleitagmnecncehcdgpsedeolgdfesrmausdpoma,t,fbdrfraahsuofeotmusetrosthnrmrh,thdireiiulatasetfodahonyrinbratiicetstdenhniuniihthtfimaisergydiseneletlcrtrdraagaitsraheahuiliuhtmtnaenlrsermhecuampigtfatanaulcuauwalltngttrathcarslhuhfodteesnsim-r-wseuaudprreffl,sseloesusoasdtosfllec,hucmlaleaouttobeetsltihaddeeoseuresrfeeenddmtdotspbrtditereecfl,pepepeairuotnacrarmrlitswaeiinnniretoaeomi,tardnilridmsrit-afiiwaniphtttmtncuoiiiheoisitneidenrtdtieirashegasfttl.i.dsntsasaa-gshBtptptsdoaaBuaaieasopocntnpraetsircrnhfadodessptoesesesdnsrarxtsrmdoohhaneieoaamxcnceiesdonnncgirsndmnahdeedhmttttrhiharaegttloetseeehhealtihfonyecovneenffrlttelne6dytaehenfebl.oetavseaa6duasfDetectooblicardulrlotefesufacehrbsnt-farcsreobeiwiae.knrge-faocsewlncneDklfafdnuolrluenslet.rofrfnfialpnesrrlmpCsleencoiaeupgapsoolncemadartsnemmrsthlk-c.esees----

prceicpiiptaittaiotinonseseeneinn itnhitshgiseoggeroagprhaipchaliclaolcaloticoant.ioNna. tuNraaltugrraalssgarathssleatitchflieetlidcsfiaerledsofateren oufntuensa-

unbulesafobrlelafrogrelapregreiopdesrioofdtsheofytehaer yineathr iisnltohciastiloonca; ttihoenr;etfhoreer,efaonrea,rtainficairatlifitucriaf lstuurrffacseurwfaocueld

wpouroldvipdreoyveidaer yroeuarnrdomunudltmifuunltciftuionncatilounsael,ulesaed, lienagdtionggrteoagtreerahteeralhtheabltehnbeefintsefifotsr faolraarglaerrgperro-

prpooprotriotinonofofththeeccoommmmuunnitityy.. AAddddiittiioonnaallllyy,, iinncclluuddeeddiinnththeeppuubblilci-ch-heaelatlhth-i-nifnofromrmededdedseigsingn

plpanlanwwasaasnaninitnetrearcatcivtievpelpalyaystsrutrcutcutruerfeofrocrhcihldilrdernenagaegdedfofuoruyreyaerasrasnadndunudnedre. rI.nIfnofromrmataiotinon

frofrmomthtehepaprakrkanadndgrgereenenspsapcaeceinivnevnetnotroyryinidnidcaictaetdedthtahtatthtehecitcyitylalcakcekdeddeddeidcaictaetdedplpalyay

stsrutrcutcutruerseos roernevnivroirnomnmenetnstsfofrotrhtihsiasgaegegrgoruopu,ps,esveevreerleylylimlimitiintigngthtehehehaelathlthbebneenfietfsittshtahtat

outdoor play can have during this developmentally critical period in life. It was also

recommended that the structures tailored towards younger age groups include covered

areas to provide a longer window of use throughout the year and to be more inclusive

of the needs of breastfeeding mothers. Adaptive play structures and environments was

also recommended in order to be more inclusive of individuals with physical and sensory

challenges. Lastly, covered picnic structures were recommended based on the evidence

supporting the importance of community social cohesion that parks are able to provide [29].

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

11 of 14

4.2. The Importance of a Public Health Approach

The significant associations seen in Tables 3 and 4, and the final adjusted regression

model in Table 5, all highlight the relationship between places to be physically active and

mental and physical health. This is supported by findings from other studies that show

significant relationships between mental health outcomes [30] and proximity to green

spaces, as well as physical health outcomes and green-space density [31]. Conducting

a community health assessment at a local level is particularly beneficial for providing

data to local government and stakeholders. Local health data provides valuable insight

into the unique needs and priorities of each community, greatly improving the evidence

supporting specific design elements of a particular UGS. Research have shown that public-

health-focused approaches to green space interventions are more likely to improve health

behaviors [32,33].

The timeline in which the four teams contributed to the UGS design framework also

provided unique insights into the application of the framework. The public-health-informed

design recommendations occurred after the government, community, and environmental

teams submitted their design proposals. This allowed for an informal assessment of what

the design plan would look like without the public health-informed guidance. It should

be noted that this was not an intentional design of the methodology of the research study.

Rather, it was a reflection of the local government’s general exclusion of public health

guidance in the initial design of this UGS. As a result, this paper is able to provide a natural

experimental perspective of how a UGS would have been designed with government

oversight and community and environmental input, but without public health guidance.

Prior to the public-health-focused design recommendations, the green space was proposed

to be a general use park with athletic fields and an open grass field that stopped at the

hard border of the stream riparian buffer zone. This design would have resulted in a green

space that functioned strictly as a sports and recreation park and therefore did not meet

the definition of multifunctionality. The inclusion of the nature-therapy transition zone

is an important element that creates multifunctionality and targets additional groups for

health benefits related to improving psychological wellbeing. In addition, the natural play

structures and environments for the 0–4 age group was not present before the public health

assessment of groups that lacked adequate opportunities for nature play in the city. Lastly,

the public health framework identified a lack of any sensory and adaptive play equipment.

Improving the accessibility of parks and green spaces was a top priority of the public

health-focused design proposal.

4.3. Strengths of This Study

The significance of this paper to the literature on nature and public health is in the

application of a multidisciplinary, community-involved, public health-informed framework

for UGS design. The framework, as outlined in this study, include four areas of influence:

(1) community involvement, (2) an evidence-based public health approach, (3) invested

environmental groups, and (4) local government land use and planning officials. These

four areas of influence were able to work collaboratively to design an UGS that can support

the three main functions of (1) sports and recreation, (2) nature-based wellness for all ages,

and (3) environmental improvements and sustainability.

The inclusion of the local community throughout the collaborative cocreation process

was essential to ensure that the UGS was adapted to their needs, and that the prioritized

health and wellbeing outcomes are achieved. Public health approaches and recommenda-

tions are also strengthened when developed in collaboration with what the community

describes as its priorities [34]. Ultimately, partnerships between public health teams and

community groups, such as in this study, are essential for maximizing the inclusivity, access,

and utilization of green spaces.

Currently, much of the design and development of green spaces occur at the discretion

of local government, with little or no community involvement or public health influence.

Including local public health experts can serve several functions. (1) The design of different

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

12 of 14

elements of parks and green spaces can be supported by evidence that they influence

health-related behaviors and outcomes. (2) Local public health practitioners and scientists

can assist with methods of conducting a health impact assessment to identify priority

targets and the most effective use of the space for the greatest health impact. (3) Lastly,

they can help to identify appropriate measurable outcomes and develop strong evaluation

plans. Local public health departments are valuable resources for healthy urban planning

partnerships, as they are particularly well versed in the current health needs and priorities

of the communities in which they serve and live.

4.4. Challenges of This Study

While this study provides a template for an effective multidisciplinary design frame-

work, there were several challenges. Firstly, an increase in the number of contributing

teams added a level of complexity to traditional government-led green space design. Other

challenges included organizing effective communication plans between the various con-

tributing design groups. Working on roles, responsibilities, and communication strategies

for design teams early on will ensure that a more cohesive planning process occurs. Lastly,

it should be noted that there remains uncertainty as to how the work of all of these groups

will be included in the final development of the UGS. Ultimately, it is the decision of the

local city council and planning commission to finalize the design of the green space. While

local city officials have responded favorably to the design components submitted by each

design group, it has not yet been decided which elements will be included in the final UGS

development. Urban planners must balance the range of competing demands, including

housing demand, economic development, and long-term city planning, and recognize that

optimizing green space for maximum health benefits is not always a priority [35].

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

While this paper provides an important case study of a community-involved, public-

health-informed design approach for green spaces, there remain several limitations. The

relatively small sample sizes of the community survey responses, as well as the health

impact assessment, may result in health data and community park input that are not

reflective of the greater community.

The moderately large size of the UGS in this case study allowed for enough physical

space for a focus on all three priorities: (1) sports and recreational fields and spaces,

(2) undeveloped, natural open spaces for nature play and nature therapy, and (3) wildlife

habitat and stream restoration. Communities and local governments may face the challenge

of working with much smaller green spaces when trying to maximize them and design

for multifunctional use. However, this framework is not necessarily dependent on large

green spaces, and can be applied to the design of relatively small green spaces. Research

has shown that many of the health benefits related to being in nature can be achieved in

relatively small natural environments. For example, South et al. [36] demonstrated in a

cluster randomized trial that the “greening” of vacant lots reduced self-reported feelings of

depression and worthlessness in the intervention group compared to the control group.

Future research should focus on approaches to multifunctional green space design

that can be scaled down for smaller spaces such as “pocket parks”, which are smaller green

spaces located throughout neighborhoods. Additionally, larger sampling of community

health data, and community feedback on parks and green spaces, would ensure that

larger communities are represented. The incorporation of theoretical models driving

multidisciplinary UGS design would also improve our understanding of the relationship

between UGS design-based interventions and their use and related health impacts.

5. Conclusions

This study provides important insight into how to develop community-involved,

public health-informed design principles for a multifunctional green space. While every

green space has unique contextual variables around its design and development, this paper

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

13 of 14

provides a case study of how the needs of many groups in a community can be met while

also restoring natural areas and stream and wildlife habitats. Furthermore, by including

public health experts and the local community, the restoration of natural areas can in fact

be inclusive of the important health benefits associated with human interactions in natural

areas and spaces. The study also highlights the importance of community- and public

health-involved frameworks in the design phases of green space development. While land

use and development policies are primarily driven by local governments throughout much

of the world, work needs to be undertaken to connect local government decision makers

with public health scientists and community groups. With the amount of available urban

green space declining in most communities, it is critical that efforts are made to make these

areas as accessible as possible for a wide range of populations. Optimizing green spaces for

sports and recreation as well as interactions with nature will ensure that communities can

experience the many interrelated yet distinct health benefits of green spaces.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due

to the use of secondary data.

Data Availability Statement: The data presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank the Scappoose Parks and Recreation Committee for their

tireless commitment to improving the parks and green spaces in their community.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

1. WHO/Europe Reports on the Contribution of Urban Planning and Management to Resilience and Health Protection. Available

online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/13-06-2022-who-europe-reports-on-the-contribution-of-urban-planning-

and-management-to-resilience-and-health-protection (accessed on 4 August 2022).

2. Veen, E.J.; Ekkel, E.D.; Hansma, M.R.; de Vrieze, A.G.M. Designing Urban Green Space (UGS) to Enhance Health: A Methodology.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 5205. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

3. Almanza, E.; Jerrett, M.; Dunton, G.; Seto, E.; Pentz, M.A. A Study of Community Design, Greenness and Physical Activity in

Children Using Satellite, GPS and Accelerometer Data. Health Place 2012, 18, 46–54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. Mytton, O.T.; Townsend, N.; Rutter, H.; Foster, C. Green Space and Physical Activity: An Observational Study Using Health

Survey for England Data. Health Place 2012, 18, 1034–1041. [CrossRef]

5. Cleland, V.; Crawford, D.; Baur, L.A.; Hume, C.; Timperio, A.; Salmon, J. A Prospective Examination of Children’s Time Spent

Outdoors, Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Overweight. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1685–1693. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

6. Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X.; Kolt, G.S. Greener Neighborhoods, Slimmer People? Evidence from 246,920 Australians. Int. J. Obes.

2014, 38, 156–159. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

7. Shin, J.C.; Parab, K.V.; An, R.; Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S. Greenspace Exposure and Sleep: A Systematic Review. Environ. Res. 2020,

182, 109081. [CrossRef]

8. Gascon, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Martínez, D.; Dadvand, P.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Plasència, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Residential Green

Spaces and Mortality: A Systematic Review. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 60–67. [CrossRef]

9. Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The Health Benefits of the Great Outdoors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Greenspace

Exposure and Health Outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [CrossRef]

10. Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X.; Kolt, G.S. Is Neighborhood Green Space Associated with a Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes? Evidence

from 267,072 Australians. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 197–201. [CrossRef]

11. McCormick, R. Does Access to Green Space Impact the Mental Well-Being of Children: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs.

2017, 37, 3–7. [CrossRef]

12. Wang, P.; Meng, Y.-Y.; Lam, V.; Ponce, N. Green Space and Serious Psychological Distress among Adults and Teens: A Population-

Based Study in California. Health Place 2019, 56, 184–190. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

13. Engemann, K.; Pedersen, C.B.; Arge, L.; Tsirogiannis, C.; Mortensen, P.B.; Svenning, J.-C. Residential Green Space in Childhood Is

Associated with Lower Risk of Psychiatric Disorders from Adolescence into Adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116,

5188–5193. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

14. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological Effects of Nature Therapy: A Review of the Research in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res.

Public. Health 2016, 13, 781. [CrossRef]

15. Morita, E.; Fukuda, S.; Nagano, J.; Hamajima, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwai, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Ohira, H.; Shirakawa, T. Psychological

Effects of Forest Environments on Healthy Adults: Shinrin-Yoku (Forest-Air Bathing, Walking) as a Possible Method of Stress

Reduction. Public Health 2007, 121, 54–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10867

14 of 14

16. Artmann, M.; Inostroza, L.; Fan, P. Urban Sprawl, Compact Urban Development and Green Cities. How Much Do We Know,

How Much Do We Agree? Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 3–9. [CrossRef]

17. Lee, A.C.K.; Jordan, H.C.; Horsley, J. Value of Urban Green Spaces in Promoting Healthy Living and Wellbeing: Prospects for

Planning. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2015, 8, 131–137. [CrossRef]

18. Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Sun, R.; Vejre, H. Links between Green Space and Public Health: A Bibliometric Review of Global

Research Trends and Future Prospects from 1901 to 2019. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 063001. [CrossRef]

19. Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Underlying Relationships between Public Urban Green Spaces and Social Cohesion: A Systematic

Literature Review. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 24, 100383. [CrossRef]

20. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Scappoose City, Oregon. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/scappoosecityoregon

(accessed on 21 August 2022).

21. Brussoni, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Brunelle, S.; Herrington, S. Landscapes for Play: Effects of an Intervention to Promote Nature-Based

Risky Play in Early Childhood Centres. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 139–150. [CrossRef]

22. Mnich, C.; Weyland, S.; Jekauc, D.; Schipperijn, J. Psychosocial and Physiological Health Outcomes of Green Exercise in Children

and Adolescents—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 4266. [CrossRef]

23. Groves: Natural Play: Making a Difference to Children’s Learning and Wellbeing. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/

scholar_lookup?title=Natural+play:+making+a+difference+to+children%E2%80%99s+learning+and+wellbeing&author=H+

Groves+LM&publication_year=2011& (accessed on 2 August 2022).

24. Dowdell, K.; Gray, T.; Malone, K. Nature and Its Influence on Children’s Outdoor Play. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2011, 15, 24–35.

[CrossRef]

25. Zamani, Z.; Moore, R. The Cognitive Play Behavior Affordances of Natural and Manufactured Elements within Outdoor Preschool

Settings. Landsc. Res. 2013, 1, 268–278.

26. Gardner, P.; Kuzich, S. Green Writing: The Influence of Natural Spaces on Primary Students’ Poetic Writing in the UK and

Australia. Camb. J. Educ. 2018, 48, 427–443. [CrossRef]

27. Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological Benefits of Greenspace Increase with

Biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [CrossRef]

28. Wen, Y.; Yan, Q.; Pan, Y.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y. Medical Empirical Research on Forest Bathing (Shinrin-Yoku): A Systematic Review.

Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 70. [CrossRef]

29. Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 452. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

30. Callaghan, A.; McCombe, G.; Harrold, A.; McMeel, C.; Mills, G.; Moore-Cherry, N.; Cullen, W. The Impact of Green Spaces on

Mental Health in Urban Settings: A Scoping Review. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 179–193. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

31. De la Fuente, F.; Saldías, M.A.; Cubillos, C.; Mery, G.; Carvajal, D.; Bowen, M.; Bertoglia, M.P. Green Space Exposure Association

with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Physical Activity, and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 97.

[CrossRef]

32. Hunter, R.F.; Cleland, C.; Cleary, A.; Droomers, M.; Wheeler, B.W.; Sinnett, D.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Braubach, M. Environmental,

Health, Wellbeing, Social and Equity Effects of Urban Green Space Interventions: A Meta-Narrative Evidence Synthesis. Environ.

Int. 2019, 130, 104923. [CrossRef]

33. Masterton, W.; Carver, H.; Parkes, T.; Park, K. Greenspace Interventions for Mental Health in Clinical and Non-Clinical

Populations: What Works, for Whom, and in What Circumstances? Health Place 2020, 64, 102338. [CrossRef]

34. Caperon, L.; McEachan, R.R.C.; Endacott, C.; Ahern, S.M. Evaluating Community Co-Design, Maintenance and Ownership of

Green Spaces in Underserved Communities Using Participatory Research. J. Particip. Res. Methods 2022, 3, 35632. [CrossRef]

35. Colding, J.; Marcus, L.; Barthel, S. Promoting Partnership between Urban Design and Urban Ecology through Social-Ecological Resilience

Building; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [CrossRef]

36. South, E.C.; Hohl, B.C.; Kondo, M.C.; MacDonald, J.M.; Branas, C.C. Effect of Greening Vacant Land on Mental Health of

Community-Dwelling Adults: A Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e180298. [CrossRef] [PubMed]