Encountering the Sacred Temenos:

Somatically Integrating Cumulative Trauma and Discovering Wellbeing Within

by

Chelsea Phillips

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of

Master of Arts in Counseling Psychology

Pacifica Graduate Institute

27 February 2017

ProQuest Number: 10259259

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript

and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

ProQuest 10259259

Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author.

All rights reserved.

This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code

Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

ProQuest LLC.

789 East Eisenhower Parkway

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346

ii

© 2017 Chelsea Phillips

All rights reserved

iii

I certify that I have read this paper and that in my opinion it conforms to acceptable

standards of scholarly presentation and is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a

product for the degree of Master of Arts in Counseling Psychology.

____________________________________

Avrom Altman, M.A., L.M.F.T., L.P.C.

Portfolio Thesis Advisor

On behalf of the thesis committee, I accept this paper as partial fulfillment of the

requirements for Master of Arts in Counseling Psychology.

____________________________________

Avrom Altman, M.A., L.M.F.T., L.P.C.

Research Associate

On behalf of the Counseling Psychology program, I accept this paper as partial

fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts in Counseling Psychology.

____________________________________

Jemma Elliot, M.A., L.M.F.T., L.P.C.C.

Director of Research

iv

Abstract

Encountering the Sacred Temenos:

Somatically Integrating Cumulative Trauma and Discovering Wellbeing Within

by Chelsea Phillips

This paper explores trauma as a continuum and how various forms of trauma can be

treated with mindfulness and somatic psychotherapy modalities. Ten modalities are

discussed through hermeneutic, heuristic, and intuitive inquiry research methods: mindful

breathing; mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR); emotional freedom techniques

(EFT) and energy psychology; eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR)

and attachment focused EMDR; Hakomi mindfulness-centered psychotherapy;

sensorimotor psychotherapy; somatic experiencing; acupuncture, Soma Neuromuscular

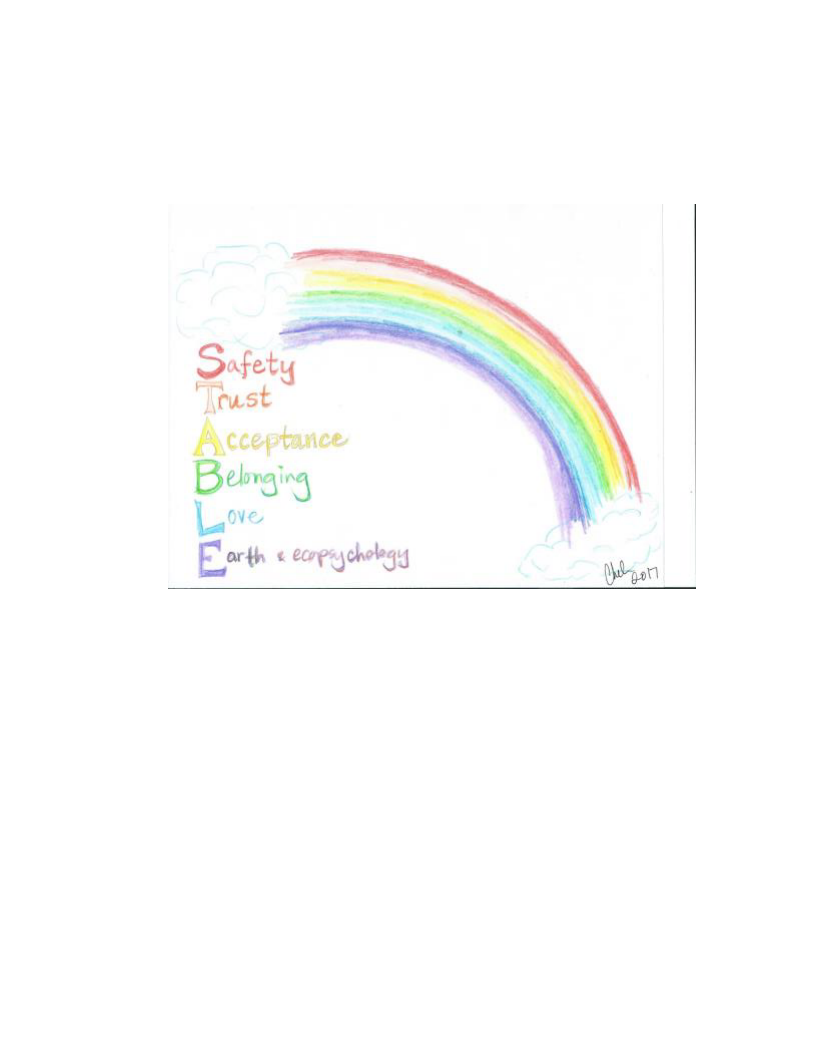

Integration® bodywork, and authentic movement. Unique to this thesis is the approach to

somatically releasing trauma using an acronym framework created by the author,

conceptualized as Safety, Trust, Acceptance, Belonging, Love, Earth, and Ecopsychology

(STABLE©). Adding a depth psychotherapy perspective, the myth of Inanna is offered as

an allegory to enrich the practice of co-regulating patients as they work through their

trauma narratives. Recognizing nature as an essential component to healing the wounds

of the soul adds an ecopsychological and wilderness therapy perspective.

v

Acknowledgments

I would like to offer my gratitude to the people who most profoundly influenced

me in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I thank my daughter Lyra Phillips,

who teaches me daily how to deepen my practice of attunement to the needs of another

and who has patiently supported me through the completion of pursuing my life dream to

become a depth and ecopsychology oriented marriage and family therapist and

wilderness therapy facilitator. My gratitude extends deeply to my ancestors and to both of

my parents, MarySue Brooks and Raymond Phillips, who have gifted me with awe

inspiring amounts of acceptance and love, secure attachment, and belief in me in all

ways. You have both taught me how to love more and to welcome adversity with grace.

To my amazing siblings Amy, Heather, and Cameron, and to our entire family—thank

you for your love, support, humor, and the closeness we share. I am blessed to be a part

of an amazing community of friends who continually inspire me, offering warmth and

support from Salt Spring Island, British Columbia to Prescott, Arizona, to Seattle,

Washington to the far reaches of my travels—you know who you are; I thank you with so

much love. To my Pacifica cohort—you have become friends and colleagues for life!

To the educators who have influenced me most throughout my lifetime for gifting

me with an enthusiasm for life and learning, calling out my wisdom, allowing the poetess

within me to be expressed, teaching me about my shortcomings, and expanding my

curiosity: Marcia Larson—you gave me my Montessori, self-directed learning beginning

and celebrated my creative and caring soul. Mary O’Malley—you inspired me to become

vi

a spiritual retreat facilitator and to be a therapist who welcomes my clients back to the

home of their being. Ellen Abell—I instantly wanted to be like you! Your wise clarity,

feminist strength, and confident ease were qualities in myself I grew into as you

mentored and believed in me. Lilla Cabot—you taught me how to question the status quo

from a feminist perspective and encouraged me that in my gentleness there is great

strength. Wayne Regina—you gave me an outstanding education in marriage, family, and

couples therapy from a family systems orientation. Jo Beth Eckerman, Karen Bolesky,

and Marcia Nolte—you gave me the tools and training to facilitate energy and somatic

healing, as well as authentic movement at a core level. To the teachers who nurtured me

as a writer and poet—Carmen Roedell, Carol Erickson, Leanne Lukas, Carmine

Chickadel, and Michael Nipert. To Larry Buell, Dave Craig, Denise Mitten, Erin Lotz,

Julie Munro, Roxane Ronca, Claire Oberst, Fiona Reid, J. Dianne Brederson, Bob Ellis,

Mark Riegner, Tom Fleishner, Laura Sewall, Steve Munsell, David Lovejoy, and Doug

Hulmes—phenomenal experiential and adventure educators who initiated me in

necessary rites of passage to become a wilderness therapy facilitator.

To my mentors at Pacifica Graduate Institute: your depth and caring, combined

with your finesse in the art of therapy fostered the confidence and competence in me to

step into the world as a ecopsychology and depth focused marriage and family

therapist—Marilyn Owen, Avrom Altman, Michelle Villegas, Sukey Fontelieu, Willow

Young, Kathee Miller, Barbara Boyd, Allen Koehn, Nicole Zapata-Williams, Matthew

Bennett, and Christine Downing.

Special thanks to Kim Sather—supervisor, mentor, and friend and to the entire

staff at my counseling internship site. Thank you to the therapists I have worked with

vii

throughout my life journey. To Kathleen Lumiere, Alda Blanes, Kim Hansen, Jared

Kohler, and Wolfgang Brolley—five of the finest somatic healers I have encountered and

benefited from their skills. To my past, present, and future clients I give my utmost

gratitude.

Finally, I give thanks to my intuitive heart and my soul essence, guiding me every

step of the way on the wild, reflective, and wondrous path that is my life.

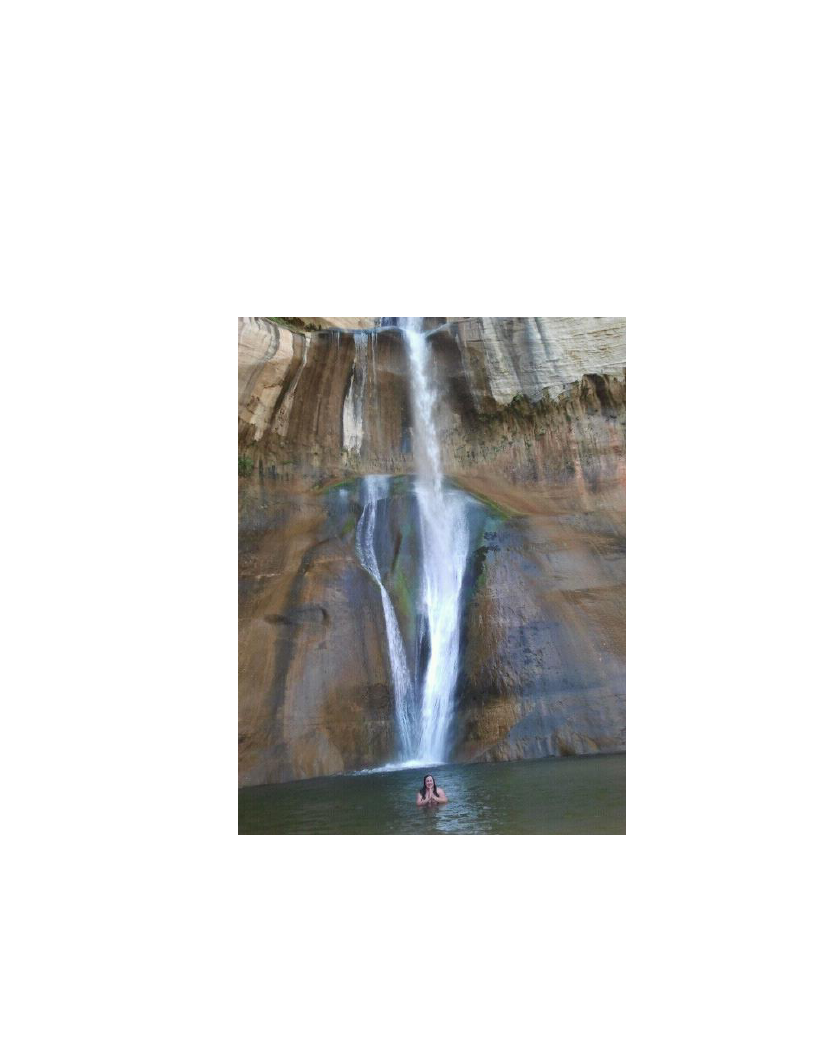

Nature & Psyche in Bliss

Calf Creek Falls, Utah

Photograph of Chelsea Phillips by Lauren Brule (2013)

Reprinted with permission.

viii

Dedication

This thesis is dedicated to the poetic moments in our lives that thrill our hearts

and warm our souls and it is also dedicated to working with what gets in the way of being

able to feel such moments. To the beauty of the microcosmic and macrocosmic Earth:

with its innumerable and miraculous permutations of life loving life into creation and

ever-unfolding transformation—the ultimate teacher in the cycles of birth and death and

rebirth. May Safety, Trust, Acceptance, Belonging, Love, and connection with Earth

become allies in the process of somatically releasing and integrating cumulative trauma.

And may the qualities of inclusivity, playfulness, empathic attunement, kindness, and

peace be a part of the journey into wellbeing within.

Blooming into Being

Prince Rupert, British Columbia

Photograph by Chelsea Phillips (2015)

ix

Table of Contents

Chapter I Introduction..................................................................................................1

Area of Interest ........................................................................................................1

Guiding Purpose.......................................................................................................3

Rationale ..................................................................................................................4

Methodology ............................................................................................................5

Research Problem ........................................................................................6

Research Question .......................................................................................7

Ethical Concerns ......................................................................................................7

Overview of Thesis ..................................................................................................7

Chapter II Literature Review.........................................................................................9

Introduction ..............................................................................................................9

Trauma Has Many Forms: Differentiations and Definitions .................................10

Trauma Symptoms: How They Show Up Clinically .............................................11

Emotional Regulation, Affect Regulation, and Self-Regulation ...........................12

Polyvagal Theory ...................................................................................................13

Window of Tolerance ............................................................................................14

Highly Sensitive People .........................................................................................15

The Importance of Integration as a Concept and Experience ................................16

Somatic Modalities Utilized in the Treatment of Trauma .....................................16

Mindfulness Breathing: One Belly Breath at a Time.................................17

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction ........................................................18

Acupuncture ...............................................................................................19

Energy Psychology and Emotional Freedom Technique ..........................20

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing ....................................21

Hakomi Mindfulness-Centered Psychotherapy .........................................22

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy .....................................................................24

Somatic Experiencing® .............................................................................25

Soma Neuromuscular Integration® Bodywork .........................................26

Authentic Movement .................................................................................27

Attachment and Bonding: What Love Has to Do With It......................................28

Chapter III Findings and Clinical Applications............................................................30

Encountering the Sacred Temenos.........................................................................30

Trauma as Cumulative and on a Continuum..........................................................33

Co-creating the Sacred Temenos with Patients and Clients ..................................34

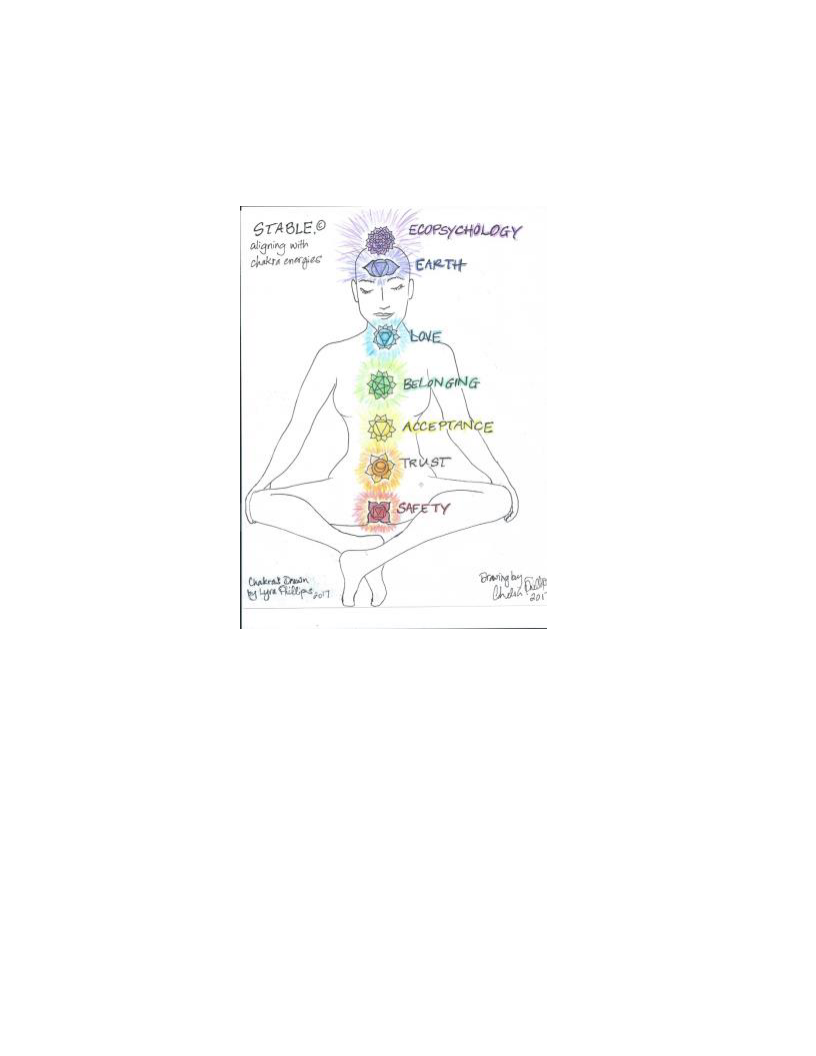

STABLE©: Safety, Trust, Acceptance, Belonging, Love, Earth, and

Ecopsychology .......................................................................................................34

Nature’s Influence on the Psyche ..........................................................................37

x

Exploring the Application of Somatic Modalities .................................................39

Affect Regulation and the Introduction of Conscious Co-Regulation...................41

Shadow Integration ................................................................................................42

The Myth of Inanna as an Allegory for Processing Trauma..................................44

Discovering and Cultivating Wellbeing.................................................................47

Clinical Applications .............................................................................................49

Chapter IV Summary and Conclusions ........................................................................51

Summary ................................................................................................................51

Suggestions for Further Research ..........................................................................52

Conclusions ............................................................................................................53

Appendix A STABLE© Rainbow Drawing Used Clinically .........................................55

Appendix B Using STABLE© to Address Client Dysregulation: A Clinical Example 56

References ..........................................................................................................................59

xi

List of Illustrations

Figure 1

Nature & Psyche in Bliss .......................................................................... vii

Photograph of Chelsea Phillips by Lauren Brule, 2013

Reprinted with permission

Figure 2

Blooming into Being ................................................................................ viii

Photograph by Author, 2015

Figure 3

Gentleness Embodied ................................................................................. xi

Photograph by Author, 2015

Figure 4

STABLE© ...................................................................................................36

Drawing by Author, 2017

Figure 5

Rainbow Drawing of STABLE© ................................................................54

Drawing by Author, 2017

Gentleness Embodied

Carpinteria, California

Photograph by Chelsea Phillips (2015)

Chapter I

Introduction

Area of Interest

My fascination with the subject of the release and integration of somatically

stored cumulative trauma comes from both professional and lived experience. This thesis

is based on the conjecture that all people experience various forms of trauma from micro

to macro. In order to orient the reader to the perspectives on trauma presented in this

thesis, sharing some of my history with discovering trauma work is relevant. Twenty

years ago, I was walking along a low bank waterfront trail on Salt Spring Island, British

Columbia when I had a vision of me sitting there in a circle of stones with a group of

people, cofacilitating a workshop blending bodywork, therapy, and attunement with

nature. In my vision, the circle of stones was a sacred demarcation, a safe container, a

temenos. There was some numinous connection between addressing healing the body and

healing psyche in nature that I intuitively felt was how I wanted to dedicate my life’s

work with others. I also desperately needed what this triune had to offer; I felt it in my

bones.

To pursue this dream, I discovered the field of ecopsychology and was also

introduced to the bodywork modality of Soma Neuromuscular Integration® (Bolesky,

2017). I set out to train as an ecotherapist and bodywork practitioner. As a bodywork

practitioner, I learned that tension and trauma are stored in the connective tissue and that

often my clients experienced eruptions of tears and memories, and released not just

present time tightness but years of stored trauma.

2

Before I understood the concept of the window of tolerance for emotional arousal,

I experienced being outside the window of my tolerance due to the intensity of new skill

acquisition backpacking in the wilderness of Arizona, river rafting in the Canyonlands,

and sea kayaking in the Sea of Cortez (Siegel, 2012; discussed in Chapter II). Years of

cumulatively accrued trauma came up for me during my adventure education training at

Prescott College in the form of overwhelm, overstimulation, fear, panic, a lack of

confidence, clumsiness, and at times being more dysregulated. My threshold for

disequilibrium seemed to be lower than for other students, although some students also

experienced disequilibrium. What made some of us more vulnerable to overwhelm than

others? I self-identify as a highly sensitive person (HSP) and this correlates to having a

nervous system that is more hypervigilant at times and more easily aroused by stimulus,

especially when there is a perceived threat to survival (Aron 1996, 2010; discussed in

Chapter II). Having experienced past trauma increases the sense of perceived threats

(Levine, 2010; van der Kolk, 2014).

A part of me was calling out for help in the only language it had—through the

body and psyche rather than the articulate mind. As I was studying to become a therapist,

I felt that there was a way to facilitate exhilarating backcountry trips that would be more

responsive to sensitively wired participants like me. My soul was calling for a pace that

would support my nervous system to experience cortical calm and integration in the

wilderness adventures being led. In reflecting on my experiences, I recognized that I

needed the pace of skill acquisition to slow down to make room for my internal process

to reveal itself. This realization influenced how I intend to facilitate therapeutic

experiences in nature.

3

When I encountered psychologist Pat Ogden’s (Ogden, Kekuni, & Pain, 2006;

Ogden & Fisher, 2015) sensorimotor psychotherapy something clicked. Ogden and her

colleagues were keenly aware of the need to slow experiences in therapy when a place of

trauma or dysregulation was touched. I could see that in adventure education slowing

down processes and offering choices when it comes to tasks involving physical risks may

help to bring equilibrium to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, which

may lead, as discussed in Chapter II, to increased skill acquisition, integration, ease, and

enjoyment of experiences. The more I work with clients from young children to adults,

the more I see the need to slow the pace of experience and allow empathic attunement to

take place, as this is where transformation from stored trauma into resilient wellbeing

occurs.

Guiding Purpose

When I set out to explore the topic of how to release and resolve trauma

emotionally, mentally, and somatically, I approached each topic individually, unaware of

the vast amount of research being done on the interrelatedness of attachment processes,

mind, body, and emotion in healing trauma. It was gratifying to me that the research

literature was supporting my intuition that these elements are crucially connected in

trauma, its release, and the creation of wellbeing—including issues of emotional

deregulation and unresolved trauma (Epstein, 2013; Johnson, 2013; Kabat-Zinn, 2013;

Kurtz, 1990; Ogden & Fisher, 2015; Parnell, 2013; Siegel, 2012; Shapiro & Forrest,

2016; van der Kolk, 2014; Weiss, Johanson, & Monda, 2015). This discovery spurred me

on to write this thesis. I set out to explore what somatic modalities seem most effective

for what kinds of trauma and what core needs long to be met beneath the defensive scabs

4

of trauma wounds. This research serves the underlying goals of therapy to help clients

release cumulative trauma, integrate past experiences to create cohesive narratives out of

their life histories, foster more effective emotional self-regulation, and increase their

sense of wellbeing and resilience in the present moment. It is my hope that readers from

professional fields that serve people’s psychological and physical wellbeing and those

with a curious mind will gain useful insights and be motivated to further explore the

approaches to treating cumulative trauma I reference in this thesis.

My hope in crafting this thesis was to envelop this synthesis of research in a depth

psychology approach with the use of language as a healing balm—to craft my thesis in

such a way that the reader has an experience of cortical calm, while reading my work. I

hoped to allow the experience of writing my thesis to be personally healing and grow me

into a better, more informed therapist. My hope is that the same kind of process happens

for my readers—where they feel acknowledged in their micro and cumulative trauma

experiences. I hope to convey to readers the uplifting idea that wellbeing is a state one

can return to again and again throughout life and within a single day.

Rationale

Trauma does not affect some people; it impacts all people (Epstein, 2013). Thus,

seeing trauma on a continuum may be helpful—from micro to macro. All people begin as

infants—vulnerable and without adequate defenses against innumerable forms of

stimulus. Some stimuli are pleasant and welcome, opening the infant further to seek more

of what feels good. Other forms of stimuli create micro trauma responses of contraction,

retraction, fear, and uncertainty. Macro trauma is inclusive of singular or repeated

incidents such as war, domestic violence, sexual abuse, rape, severe car accidents, and

5

other threats to one’s existence (Herman, 1997; van der Kolk, 2014). Developmental

trauma—that which negatively effects psychological growth during childhood—can

impact a person for the duration of his or her life. Cumulative trauma describes the

accrual of unprocessed experiences of traumatizing events. The extent to which stimuli is

trauma inducing depends on the individual’s unique set of genetic, in-utero, postnatal,

and developmental nurturance and circumstances that contribute to both cumulative

trauma and resilience. Given that every person encounters negative experiences, some of

which result in trauma responses, exploring how to release trauma from psyche and body

to move forward in life in a balanced and emotionally regulated way seems important to

practitioners, patients, and family members worldwide.

Methodology

The research and writing process in this thesis became a blend of hermeneutic,

heuristic, and intuitive inquiry approaches (Coppin & Nelson, 2005, pp. 28-33, 133).

“Hermeneutic analysis is required in order to derive a correct understanding of a text. . .

Interrelationship of science, art, and history is at the heart of hermeneutic design and

methodology” (Moustakas, 1994, p. 9). Having experienced various forms of trauma in

my life, the healing process I have undergone has become a guide in service to my

research. However, my personal journey is not the central focus of this thesis. In this

way, the heuristic aura informed how I went about writing this thesis from lived events

blended with research supporting my conjectures (Dane, 2011, pp. 44-45).

Throughout this writing process, I have released trauma from my tissues through

various forms of bodywork in conjunction with therapy, meditation, and time in nature.

In this way, I underwent an experience of intuitive inquiry: The health practitioners who

6

assisted me in healing served as a panel to reflect what they observed in me during my

process with them (Coppin & Nelson, 2005, pp. 32-33). Phenomenologically, I

somatically released trauma in conjunction with psychotherapy, and thus I became a

living example of my thesis research, as my therapy clients also did (Creswell, 2009, p.

13). The documentation of this process may be helpful for others to explore their personal

and professional encounters with releasing and integrating trauma.

Research problem. I believe that greater exploration of the relationships between

highly sensitive individuals, trauma somatization in the body, attachment and bonding,

self-regulation, and the holistic treatment of cumulative trauma from a depth perspective

would be beneficial to a large populous. It seems that as a result of the existing research

into this subject trauma and attachment have become buzz words, but this only highlights

the importance of continuing to add a depth psychotherapy voice to the dialogue.

The very pace of life can cause cumulative micro traumas: speeding down the

freeway; being inundated by electronic media; lacking time to go outside and be breathed

by the trees; global warming; increasing economic stress, debt, and homelessness; and

feeling isolated in a world where its human population is growing while other species are

racing toward extinction all contribute to cumulative trauma (Wilson, 2016). All these

micro traumas tend to be somatized in the body as it continually seeks homeostasis.

Highly sensitive individuals are most likely to have and be aware of a traumatogenic

psychological and somatic reaction to these life experiences. Creating strong

interpersonal bonds and secure attachments can be a healing balm to the growing

epidemic of isolation and support resilience and the healing of trauma. I aimed to explore

and synthesize research on trauma as a continuum inclusive of micro traumas and its

7

treatment through 10 different modalities, weaving the research into a depth psychology

approach.

Research question. Acknowledging the postulation that every person has somatic

experiences of trauma, this thesis asks: What methods are effective in the relief of trauma

symptoms, and in what ways does creating a sacred temenos, a safe container, in

therapeutic settings help to release and integrate trauma and then lead to greater

wellbeing?

Ethical Concerns

The primary ethical concern of this thesis is the potential for the author or a reader

to reexperience traumatic memories or to become activated by the material focusing on

somatized trauma. It is important that both the author and the reader be aware of personal

limitations and consult with a therapist or other natural supports if activation or

retraumatization occurs while writing or reading this material. In discussing work with

clients or patients, I used generalities of experience, amalgamating various clients’

experiences. To protect the privacy of my patients I did not use names or specific details

which could lead to any form of personal identification.

Overview of Thesis

The title of this thesis is a primer to the entire work in that each key word has at

least one interrelated section that explores its relevance. Chapter II deepens the

discussion with an overview of the key topics to understand when exploring somatically

stored trauma: differences between forms of trauma, the clinical appearance of trauma

symptoms, emotional regulation, polyvagal theory, the window of tolerance, highly

sensitive people (HSPs), and the integration of somatic content. The second portion of the

8

literature review adds perspectives from essential founders and practitioners of 10

somatic modalities that treat trauma: mindful breathing, mindfulness-based stress

Reduction (MBSR), acupuncture, Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) and energy

psychology, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and attachment

focused EMDR (AF-EMDR), Hakomi Mindfulness-Centered Psychotherapy,

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, Somatic Experiencing®, Soma Neuromuscular

Integration® bodywork, and Authentic Movement. The final section of Chapter II

discusses the essential aspects of attachment theory and bonding that highlight the

importance to wellbeing of the affiliative nature of humanness.

Chapter III opens the reader into the lens from which I do trauma work, inclusive

of Safety, Trust, Acceptance, Belonging, Love, Earth, and Ecopsychology (STABLE©),

an acronym and method conceptualized by the author. This way of working with clients

leads into a discussion of the process of making trauma work effective and how I have

observed integration and release of cumulative trauma to unfold. A depth psychological

view of integrating unconscious memories and affect is presented that draws on the myth

of Inanna (Perera, 1981) as an allegory for movement from the dysregulation of trauma to

a state of a greater wholeness. Chapter III also discusses the clinical applicability of

working with somatic modalities in the treatment of trauma symptoms. Chapter IV

provides a summary of thesis topics and suggestions for further research. The conclusion

offers final reflections and a synthesis of how therapists, facilitators, and health

professionals can incorporate the concepts offered in this thesis into their professional

practices.

Chapter II

Literature Review

Introduction

There are already multitudes of modalities and techniques to somatically address

trauma symptoms. Founder and director of the Trauma Center in Brookline,

Massachusetts, Bessel van der Kolk (2014) made the bold statement, “We are on the

verge of becoming a trauma-conscious society” (p. 349). What is exciting about van der

Kolk’s assertion is that although trauma is not considered something to look forward to

encountering, when the global populous can recognize trauma affects everyone, then the

impact trauma has on individuals and society at large can begin to transform at every

level.

There is an opportunity to recognize that physical and emotional pain affect

everyone and can show up invisibly or dramatically, and it does not make people who

name their experiences weaker or less effective. This is true unless they become

categorized as such by some internal or external source. Being categorized as weaker of

body or mind and as less than others occurred for soldiers after coming home from World

War I, World War II, The Korean War, and the Vietnam War when they experienced

symptoms of trauma from war (Levine, 2010, pp. 32-33). This history is where the

diagnosis for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) originated (American Psychiatric

Association [APA], 2013; Levine, 2010). Changing the perspective that someone is less

valuable when they need time to heal and reintegrate from stressful or traumatic

10

experiences seems to be unfolding. In this way a new paradigm of greater empathic

attunement and compassion may be on the horizon globally.

Trauma Has Many Forms: Differentiations and Definitions

Most people from adolescence into adulthood in Western culture have been

introduced to the concept of PTSD. The American Psychiatric Association (2013)

described PTSD to include directly experiencing, witnessing, or learning about traumatic

events occurring with close family members resulting in the expression of intrusive

symptoms and avoidance behaviors (p. 271). Van der Kolk (2011) recognized,

When post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) first made it into the diagnostic

manuals, we only focused on dramatic incidents like rapes, assaults, or accidents

to explain the origins of the emotional breakdowns in our patients. Gradually, we

came to understand that the most severe dysregulation occurred in people, who, as

children, lacked a consistent caregiver. Emotional abuse, loss of caregivers,

inconsistency, and chronic misattunement showed up as principal contributors to

a large variety of psychiatric problems. (pp. xi-xii)

The topic of trauma as a focus in medicine, therapy, and somatic healing

modalities is not new, yet there seem to be pervasive misconceptions around what is

considered traumatic or what can be legitimately called trauma (van der Kolk, 2016). Van

der Kolk (2011) acknowledged the shift in medicine, psychiatry, and psychology to

broaden trauma to include inherited family trauma and developmental trauma.

Developmental trauma has its own designated category and the methods to treat it can

involve more time, as often the wounding occurs over an extended phase in one’s life

(Stolorow, 2008). Founding faculty member and training and supervising analyst at the

Institute of Contemporary Psychoanalysis Robert Stolorow (2008) wrote,

Developmental trauma originates within a formative intersubjective context

whose central feature is malattunement of painful affect—a breakdown of the

child-care-giver system of mutual regulation. This leads to the child’s loss of

affect-integrating capacity and thereby to an unbearable, overwhelmed,

11

disorganized state. Painful or frightening affect becomes enduringly traumatic

when the attunement that the child needs to assist in its tolerance and integration

is profoundly absent. (p. 114)

Trauma is cumulative throughout one’s life and can be seen on a continuum.

Traumatic experiences from micro to macro occur in all realms of life—in every nation,

at every age, and at every socioeconomic level. Traumatic events occur at home, at

school, at work, while watching or reading the media, and in every setting one can

imagine.

Trauma Symptoms: How They Show Up Clinically

Observing how trauma symptoms display themselves can be obvious or more

mercurial depending on how defended a person becomes or how willing, consciously or

unconsciously, the person is to reveal their inner world to themselves and others

(McWilliams, 2011). Symptoms of depression, anxiety, shame, sleep disturbances,

holding one’s breath inadvertently, the inability to make eye contact, postural aberrations,

physical pain, dissociation or moments of vacancy, the use of substances to cope with

life’s stressors, weight loss or weight gain, fatigue, aversion to certain activities,

hypervigilance, greater tendency toward verbal conflicts, a lack of engagement with

previously enjoyed activities, difficulty maintaining relationships and friendships,

difficulty maintaining emotional equilibrium and responses when parenting, and greater

overwhelm when triggered in any number of ways can all be outer signs that someone is

experiencing overwhelm from accumulated trauma (Aron, 2010; Odgen & Fischer, 2015;

Parnell, 2013; van der Kolk, 2014). Archetypal psychotherapist and mythology scholar

Thomas Moore (1992) asserted, “Observing what the soul is doing and hearing what it is

saying is a way of going with the symptom” (p. 7).

12

Thus, seeing triggering and difficult life experiences as forms of micro, macro,

and cumulative trauma can become a lens through which to understand the potentially

incongruous or ineffective ways in which one goes about living one’s life. In this regard,

child psychologist Ross Greene (2014) shifted the common misconception from “kids do

well if they want to” to “kids do well if they can” (p. 10). The same applies to adults;

they do well if they can. From this place compassion for how others show up in the world

can grow.

Emotional Regulation, Affect Regulation, and Self-Regulation

The terms emotional regulation, affect regulation, and self-regulation seem to

point to much the same concept—the idea of being adaptive, flexible, and balanced

emotionally and using clear and effective communication when interacting with others is

the goal of all three similar terms (Levine, 2010; Siegel, 2012). Siegel (2012) addressed

the question of why self-regulation is essentially considered emotional regulation by

recognizing that emotion links all layers of functioning in the mind through an integrative

process (p. 306). The term affect, Siegel added, refers to tone of voice, facial expressions,

and bodily motions—all of which are considered social signals. Psychologist Peter

Levine (2010) highlighted, “The capacity to switch between different emotional states . . .

known as affect regulation . . . is the basis for the core sense of self. . . . Emotional

regulation, our rudder through life, comes about through embodiment” (p. 354).

Psychiatrist Michael Kerr and psychiatrist and Bowen family systems founder

Murray Bowen (1988), in their conceptualization of a family system, defined an

emotional system as that which governs human behavior by “processes that predate the

development of [a] complex cerebral cortex” (p. 28). In addition to the anatomical and

13

physiological aspects of emotional response, they found the emotional system to include

the relational system: “Much of the emotional functioning of the organism is geared to its

relationship with other organisms and with the environment” (pp. 28-29). This definition

of an emotional system alleviates the need to dichotomize and compartmentalize psychic

versus somatic causes of disease. Siegel (2012) discussed emotion as being a method the

body and mind use to organize and integrate, “attuning the whole organism to current

situational demands on the basis of past experience” (p. 267). Thus, emotions inform and

link mental, social, and biological systems that involve meaning making and memory

processes of human experience.

Polyvagal Theory

This way of understanding the emotional system seems to be a precursor to

understanding human emotional reactions as presented in the polyvagal theory of Stephen

Porges (2011,), professor of psychiatry and bioengineering and Director of the Brain

Body Center at the University of Chicago, Illinois. Polyvagal theory refers to the three

possible responses of the autonomic nervous system when presented with a perceived

threat to survival: fight, flight, or freeze. Van der Kolk (2011) summarized Porges’ theory

when he wrote “the social, myelinated vagus as the fine-tuning regulatory system that

opens up a role for the environment to foster or ameliorate stress-related physiological

states” (p. xiii). Polyvagal theory offers a model for understanding how the human

nervous system is designed to respond to and regulate with other humans, animals, and

all forms of life. Porges (2011) further explained the nervous system’s regulatory

response as being

a hierarchical regulatory stress-response system emerged in mammals that not

only relies on the well-known sympathetic-adrenal activating system and the

14

parasympathetic inhibitory vagal system, but that these systems are modified by

myelinated vagus and cranial nerves that regulate facial expression which

constitute the social engagement system. (p. xiii).

Polyvagal Theory points toward the subtlety of tone of voice and facial

expressions as giving very real cues as to how one behaves in stressful as well as ordinary

life circumstances (Porges, 2011, p. xiii). This recognition is exciting, because it

scientifically proves that by external influences such as nature, therapists, doctors, and

health practitioners can help co-regulate patients. The concepts presented in this theory

also offer the opportunity to acknowledge and apply the recognition that family members,

friends, colleagues, and any member of a person’s community contribute to positive or

negative co-regulation. This is interesting in light of family systems and group dynamics,

where a group mind can influence a person’s beliefs and subsequent actions.

Window of Tolerance

The window of tolerance, a term coined by psychiatrist Dan Siegel (2012), is

interrelated with polyvagal theory. Siegel wrote extensively on the window of tolerance

as present within everyone: “Each of us has a ‘window of tolerance’ in which various

intensities of emotional arousal can be processed without disrupting the functioning of

the system” (p. 281). The window of tolerance “is a zone of optimal arousal, not too high

and not too low, within which we can adaptively and flexibly process stimuli, including

thoughts, emotions, and physical reactions, without becoming overwhelmed or numb”

(Odgen & Fisher, 2015, p. 777). An expression of trauma symptoms often disrupts

emotional regulation—thus the zone of optimal arousal is often disturbed when trauma

occurs or when repressed trauma is triggered.

15

Highly Sensitive People

The designation of being a highly sensitive person (HSP) is a way to categorize

individuals who, as the name suggests, have heightened sensitivities to various stimuli as

compared to the global populous (Aron, 1996, 2010). This term was conceptualized by

Aron (1996, 2010) based on her observations of herself, those around her, and her

patients. When exploring one’s personal level of sensitivity or assessing the level of a

patient’s tolerance to stimulation from life events, the concept that roughly 15 to 20% of

the world’s population is thought to be made up of highly sensitive persons might be

illuminating (Aron, 1996, p. ix). This percentage is too large to list HSP as a diagnosis in

the DSM-5 but it deserves to be noted that one-fifth of the world’s population experience

stimuli more acutely than is typical (APA, 2013; Aron, 1996, p. ix). It is important to

recognize that there are introverted HSPs and extroverted HSPs. Through her research,

Aron (1996) recognized approximately 70% of HSPs lean toward social introversion,

preferring interactions with fewer people and experiencing overwhelm from crowds,

large parties, or at times strangers (p. 97). Aron noted that extroverted HSPs make up

roughly 30% of the HSP population and are less overwhelmed socially by larger numbers

of people (p. 97). However, extroverted HSPs do find other sources of arousal

overwhelming such as “a long work day or being in the city too much. When over-

aroused [extroverted HSPs] avoid socializing” (p. 98).

Often there is a misconception that only introverted people who have a low

window of tolerance for overstimulation are HSPs. That is not the case. People with

attention-deficit disorder (ADD) or attention hyperactive-deficit disorder (ADHD) whose

symptoms show up more externally can also be HSPs. Each client will have their own set

16

of needs in reframing their experience to come back to a place of equilibrium after

experiencing overstimulation and thus leaving their window of tolerance (Aron, 1996).

Siegel (2012) spoke to self-regulation and levels of sensitivity within the window of

tolerance when he wrote, “Each of us has a ‘threshold of response’ or the minimum

amount of stimulation needed in order to activate our appraisal systems” (p. 275). In

addition to acknowledging one’s level of sensitivity to stimuli, the presence of trauma

and attachment or relational wounds further contributes to understanding one’s threshold

of response.

The Importance of Integration as a Concept and Experience

When exploring the nature of how trauma is released from the body, integration is

an essential concept to grasp. Siegel (2013) pointed to the importance of the integration

of aspects of the self and interpersonally with others when he wrote, “Integration is the

fundamental mechanism beneath the adaptive and healthy regulation of affect, attention,

memory, and social interactions” (p. xiii). Somatic integration is a form of integration

that refers to the body assimilating change through stimuli inclusive of breath, touch, and

movement (Levine, 2010; Ogden & Fisher, 2015). Bodywork, walking, exercise in

general, stretching, and sleep can be particularly effective forms of physical integration

that stimulate positive somatic change and rebalancing. The effect of participating in

integrative activities can be improved cognition, greater creativity, and more flexibility

when new stimuli influence the body and mind (Bolesky, 2017).

Somatic Modalities Utilized in the Treatment of Trauma

What Jungian analyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés (1992) recognized has relevance for

all aspects of trauma work and somatic release: “The body remembers, the bones

17

remember, the joints remember, even the little finger remembers. Memory is lodged in

pictures and feelings in the cells themselves” (p. 200). What follows is an exploration of

a series of modalities that address somatically stored trauma rooted in physical,

developmental, psychological, emotional, and relational origins. This investigation into

each of these modalities is by no means exhaustive. There are literally hundreds of

modalities that address the release of somatic trauma (Shapiro & Forrest, 2016). Each of

the following sections offers a glimpse into a modality that informs this research.

Mindfulness breathing: One belly breath at a time. The breath bathes and

nourishes each cell of the body. Ecologist and philosopher David Abram (1996)

acknowledged the essential poetic nature of breath to human life:

The air is the most pervasive presence I can name, enveloping, embracing, and

caressing me both inside and out, moving in ripples along my skin, flowing

between my fingers, swirling around my arms and thighs, rolling in eddies along

the roof of my mouth, slipping ceaselessly through throat and trachea to fill the

lungs, to feed my blood, my heart, myself. I cannot act, cannot speak, cannot

think a single thought without the participation of this fluid element. (p. 225)

Spiritual teacher and counselor Mary O’Malley (2011) recognized the breath as a

doorway to be present for life, and to align the heart, mind, and body (p. 58). O’Malley

utilized many methods to strengthen awareness including mindfulness breathing. She

worked with clients individually and in weekly mindfulness meditation groups and has

led week-long retreats. O’Malley fostered an environment where hugs are welcome, eye

contact is encouraged, and breath becomes a gentle invitation into self-love. Silence is

still maintained for much of the time, but bonding between participants is encouraged.

Her mindfulness and breath work is full of heart.

Breath is part of the foundation of many somatic modalities aimed at releasing

trauma symptoms (Chodorow, 1991; Kabat-Zinn, 2013; Levine, 2010; Odgen & Fisher,

18

2015; Weiss et al., 2015). It opens tightness in the tissue when people focus on their

bellies rising and falling. Through their studies, psychiatrists Richard Brown and Patricia

Gerbarg (2012) have worked to legitimize the power of breath in U.S. medical and

psychiatric circles,

Breathing practice (pranayama) is one of the classical limbs of yoga. . . . Studies

are revealing that by changing the patterns of breathing it is possible to restore

balance to stress response systems, calm an agitated mind, relieve symptoms of

anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), improve physical health and

endurance, elevate performance, and enhance relationships (p. 2)

Buddhist psychologist and Vipassana meditation teacher Jack Kornfield (1993) has

taught mindful breathing as essential for living a life of balance and awareness—as a

steadying force amidst the chaos of ever-changing life. It seems simple to work with

something as fundamental as breathing to help relax and open the body. It costs nothing,

it is always available to patients and practitioners alike, it is portable, and without the

ability to rely on consistent breath, very little else matters. Mindful breathing grounds

patients in somatic awareness they can touch and feel.

Mindfulness-Based stress reduction. Mindfulness-based stress reduction

(MBSR) is a somatic modality adapted from Vipassana and Buddhist meditation

techniques that fosters an 8-week series of daily breathing and awareness exercises

(Kabat-Zinn, 2013). MBSR programs began in hospitals as a way to reduce suffering and

stress and to increase wellbeing in hospital inpatients and outpatients. Molecular biologist

and founder of MBSR Jon Kabat-Zinn (2013) recognized the power of breath and its

ability to regulate emotion:

In focusing on the breath when we meditate, we are learning right from the start to

get comfortable with change. We see that we will have to be flexible. We will

have to train ourselves to attend to a process that not only cycles and flows but

19

also responds to our emotional state by changing its rhythm, sometimes quite

dramatically. (p. 41)

Research has been conducted on the use of MBSR in treating patients with

anxiety, stress, loneliness, chronic pain, PTSD, and depression, and has been found to

produce positive change in these patients (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). “This ‘work’ involves

above all the regular, disciplined cultivation of moment-to-moment awareness, or

mindfulness—the complete ‘owning’ and ‘inhabiting’ of each moment of your

experience, good, bad, or ugly. This is the essence of full catastrophe living” (p. ix).

Kabat-Zinn effectively brought mindfulness practices into mainstream medicine

internationally, offering great promise to reduce stress and trauma symptoms.

Acupuncture. Acupuncture can have profound and lasting effects on the body,

trauma patterns, and balancing emotional states to regulate affect (van der Kolk, 2014).

Its interconnections through the energetic meridian system in the body correlate to every

muscle, joint, bone, nerve, and organ in the body. It also affects qualities in human

experience such as mood, affect, and memory. Acupuncturist Kathleen Lumiere stated

that she treats cumulative physical and emotional trauma in her practice regularly, noting

that “the acupuncture points to treat anxiety are also many of the acupuncture points to

treat trauma” (personal communication, November 21, 2016). Describing acupuncture’s

efficacy in treating trauma, scholar and doctor of pulse diagnosis William Morris (2015)

described, “All traumatic events affect the heart and circulation. . . . Healing moves from

the inside to the outside, top to bottom, most important organ to least important organ,

and from most recent to the most past” (p. 30). In support of acupuncture and other

somatic modalities in treating trauma van der Kolk (2014) recounted

20

Dr. Spencer Eth . . . conducted a survey of 225 people who had escaped from the

Twin Towers [On September 11, 2001]. Asked what had been most helpful in

overcoming the effects of their experience, the survivors credited acupuncture,

massage, yoga, and EMDR, in that order. Among rescue workers, massages were

particularly popular. (p. 233)

In the study referenced above, van der Kolk noted acupuncture was the number one

modality New York residents chose to effectively treat trauma after the terrorist attack.

Energy psychology and the emotional freedom technique. The emotional

freedom technique (EFT) works by stimulating acupoints through gentle tapping,

referencing the same meridian system used in acupuncture and acupressure (Feinstein,

Eden, & Craig, 2005). The general EFT recipe begins with tapping the top of the head,

points on the face, the trunk of the body, and the sides of the hands. EFT falls within the

overall category of energy psychology (EP). “EP has been used to treat traumatic stress in

various groups, and is establishing itself as an evidence-based treatment for post-

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, phobias, and other psychological

disorders” (Church, Piña, Reategui, & Brooks, 2012, p. 73; Feinstein, 2008). By

legitimizing energy psychology techniques as having profound results in one’s overall

health and wellbeing, the discussion of what constitutes effective psychotherapy is

broadened. Psychologist David Feinstein, energy healer Donna Eden, and EFT expert

Gary Craig (2005) explained that EP

approaches traumatic memories by sending electromagnetic impulses to the brain

that interrupt the intense emotional response the memory has been causing.

Unlike many other therapies, the emphasis is not on analyzing the memory and its

meaning. Rather, you work with acupoints. (p. 76)

EFT has been shown to affect neural responses including emission of a fear-

dampening signal to the amygdala and reduction of pain and fear in the limbic system of

the brain (Church et al., 2012, p. 74). To clarify the universality of energy work, all

21

human hands have “an electromagnetic field extending beyond the fingers, so simply

holding one’s hand over an affected part of the body can have a therapeutic effect, as can

massaging, tapping, or holding specific energy points on the skin” (Feinstein et al., 2005,

p. 5). Van der Kolk (2014) has had effective results utilizing EFT with his patients. He

has used EFT “to help patients stay within the window of tolerance and [this method]

often has positive effects on PTSD symptoms” (p. 267).

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. The modality of eye

movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) was developed by psychologist

Francine Shapiro. Clinical psychologist Laurel Parnell (2013) trained under Shapiro and

described EMDR as “a powerful tool for catalyzing integration in an individual across

several domains, including memory, narrative, state, and vertical and bilateral

integration” (p. xii), and it “can work on reprocessing the traumas so that they lose their

emotional charge” (p. 139). Shapiro and Forrest (2016) explained that in EMDR therapy,

“rather than trying to talk through the problem, the processing occurs on a physiological

level and allows new associations, insights and emotions to emerge spontaneously” (p.

2).

EMDR therapy helps to reunite traumatic memories with the more resourced

aspects of memory and self-regulation. Shapiro and Forrest (2016) illuminated that

traumas and other experiences perceived as distressing can be held “in the wrong form of

memory. Instead of being stored in memory where they can be remembered without pain,

they are stored in memory where they hold the emotions and body sensations that were

part of the initial event” (p. 2).

22

Parnell (2013) created attachment-focused EMDR (AF-EMDR), a specific

relational trauma subcategory of EMDR that focuses on healing the wounds stemming

from insecure attachments, especially those in childhood with primary caregivers. Both

the original practice of EMDR and AF-EMDR utilize alternating stimulation with

physical tapping of the client’s limbs, subtle electrical impulses with paddles the client

holds, or eye movement stimulation conducted by an EMDR trained therapist to reduce

the heightened affect surrounding a memory or relationship.

Developmental and relational trauma have an impact on genetic expression and

brain processes can have long-term effects on how a person relates to and interacts with

life and with others (Siegel, 2013, pp. xiv-xv). AF-EMDR assists in catalyzing greater

levels of integration and flexibility for those who experience insecure attachment and

developmental trauma (Parnell, 2013). Siegel (2013) summarized AF-EMDR as a way to

treat “suboptimal regulation, such as difficulty balancing emotion, experiencing joy, and

ease or focusing attention in a flexible and adaptive manner; challenges with painful

traumatic memories; and unhelpful patterns of interaction with others that result in

troubled relationships” (p. xiv). As a somatic and energy-based rather than talk-based

modality, AF-EMDR may be helpful for those who find verbal exploration of their

trauma a threatening endeavor (Parnell, 2013).

Hakomi mindfulness-centered somatic psychotherapy. Hakomi mindfulness-

centered somatic psychotherapy was founded by the late therapist Ron Kurtz (1990) in

the 1970s. The word Hakomi comes from the Hopi Indian word, the current usage of

which means, “who are you?” The older meaning is, “How do you stand in relation to

these many realms?” The word Hakomi came to one of the Hakomi originators, David

23

Winters, in a dream (Kurtz, 1990, p. i; Weiss et al., 2015, p. v). Hakomi therapists assist

their clients in observing the consciousness that arises within them through practicing

mindful awareness, thus serving clients as a gentle witness. Hakomi therapists embody

what they call loving presence with the intention of attuning to clients in such a way that

they feel safe and held. Kurtz summarized key components of Hakomi:

The basic method is: create a relationship which allows the client to establish

mindfulness, evoke experiences in that mindful state, and process the experience

evoked. Experience mirrors internal organization. It reflects memories and beliefs

and those images of self and world which organize all experience. With mindful

evocation we move close. Just a step or two, a gesture, staying a little longer with

the experience, and we are at the core. Core material goes deep; organizing beliefs

are held firmly and defended strongly. . . . Core material is not accessible through

the intellect. But it is through mindfulness. (p. 4)

Psychotherapist Richard Schwartz (2008, 2015) founded internal family systems

therapy (IFS), a modality for interacting with unconscious parts of one’s self, or inner

figures, to create greater psychological integration and wholeness. Schwartz (2015)

validated Hakomi as facilitating a state of mindful observation that supports clients to

“release core, often unconscious, beliefs,” noting that “through this process, they were

helping clients access what I call the exiled parts of themselves—vulnerable, young, hurt

parts that I was trying to get to in a different way” (p. xi).

Psychotherapist and international Hakomi trainer Manuela Mischke Reeds (2015)

observed, “Clients categorize their lives in terms of before and after the trauma

experience” (p. 274; Herman, 1997; van der Kolk, 2014).

Many traumatized clients are not able to mobilize intellectual and physical

requirements for addressing . . . their trauma. They cannot operate within the

window of tolerance where the ventral vagal nerve facilitates our capacity for

social engagement, with ourselves or others. (Reeds, 2015, p. 273)).

24

For therapy to be effective, clients need to be able to make coherent sense out of

their trauma narratives. Facilitating states of mindfulness as a part of Hakomi can be an

effective way to encourage this growth (Reeds, 2015, p. 273). Reeds (2015) articulated,

All somatic psychotherapy that aims to negotiate the arousal of the nervous

system in elegant ways seeks to track and address activations and dissociations

beyond the client’s window of tolerance, so clients can actually be present with

their experience and find new ways of relating to triggers. (p. 276)

Hakomi therapists bring attunement, limbic resonance, compassion, and love to

their clients in an atmosphere of calm and quiet, paying attention to the present moment

and the client’s direct experience (Reeds, 2015). This above all is what trauma clients

seek in therapy—to feel safe, loved, and recognized with understanding (pp. 276-277).

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy.

In the instinctive psyche, the body is considered a sensor, an informational

network, a messenger with myriad communication systems—cardiovascular,

respiratory, skeletal, autonomic, as well as emotive and intuitive.

C. P. Estés, 1992, p. 200

Ogden, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy founder and educational director of the

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute, and assistant educational director Janina Fisher

(2015) made the distinction, “The body’s intelligence is largely an untapped resource in

psychotherapy. . . . The story told by the ‘somatic narrative’—gesture, posture, prosody,

facial expressions, eye gaze, and movement—is arguably more significant than the story

told by the words” (p. 13). Sensorimotor psychotherapy is “a body-oriented talking

psychotherapy that specifically addresses trauma and attachment wounds, emphasizing

the body as an avenue for exploration and vehicle for change” (Ogden & Fisher, 2015,

p. 776). This modality was specifically designed to work with trauma and attachment

misattunements. “Resolving past trauma is not an act of will. It is the felt sense that the

25

trauma or threat is over. To experience a sense of having survived rather than a sense of

anticipatory threat requires autonomic and physical recalibration” (p. 537). Ogden and

Fisher (2015) explained,

A relational, attachment-focused therapy is a healing process not because

therapists are treating trauma and attachment; but because they are helping to

restore belief in the existence of human relatedness. The process of enactment

accomplishes this especially powerfully because it generates a here-and-now

reality that is created by both people in which the endangered attachment becomes

repairable right in the room. (p. 51)

Much of what sensorimotor psychotherapy does for clients is to slow down

processes and bring attention to breathing, posture, movement, and ways of relating, and

assess whether they are still valid or whether a change might increase wellbeing (Odgen

& Fisher, 2015). This form of therapy works with the edge of a client’s window of

tolerance to expand the window itself. This modality emphasizes the wisdom of both the

body of the therapist and the client as self-awareness is tracked and explored.

Somatic Experiencing®. Levine (2010) created Somatic Experiencing® as a

trauma treatment modality from his recognition that trauma resides not only the brain or

mind, but also in the body. This modality addresses the held patterns of tightness, tension,

and what the body somatized as real or imagined threat. Levine (2010) synthesized

multiple techniques inclusive of eye movements, vocal toning, postural changes, talk

therapy, and verbal cues. In a video recording of a portion of a session, Levine guided a

former Marine with PTSD through vocally toning while tracking Levine’s finger back

and forth, and up and down; at the end of the exercise, Levine gave the verbal cue: “And

rest” (Brooks & Walkenhorst, 2014). Levine (Brooks & Walkenhorst, 2014) summarized

that Somatic Experiencing® “…helps individuals have new experiences in their bodies,

where they feel more powerful, more centered, more grounded, then they’re able to deal

26

with those traumatic memories in a much better way—in a way that is embodying and

empowering” (3:01).

Nine key principles form the framework of Somatic Experiencing®: establishing

safety; exploring sensation; establishing pendulation and containment; titrating small

drops of trauma experience; providing a corrective and empowering experience;

separating conditioned associations of fear from biological immobility responses;

supporting self-regulation and dynamic equilibrium; and orienting to the present moment

(Levine, 2010, p. 75). Levine highlighted the essential importance of kindness and

noninvasive support when practicing this modality.

Soma Neuromuscular Integration® Bodywork. Soma Neuromuscular

Integration® is a structural integration modality created in 1977 by psychologist and

Rolfer® Bill Williams and his wife Ellen Gregory Williams (Bolesky, 2017). In Greek,

soma means “the body as distinct from the soul, or psyche,” but in the ancient Greek

language soma included mind and spirit (“Soma,” 2017, def. 2). Director of the Soma

Institute Karen Bolesky (2004) explained “The added layer of acknowledging body,

mind, and spirit as an inseparable whole system supports the multidimensional human

being” (p. 1). She recognized,

Our bodies want to heal, to feel great. But sometimes with accidents, stress,

abuse, trauma, and self-criticism, we forget to allow our body to listen to itself.

We forget, literally. If the body can return to being a listening mechanism, it will

heal. All touch therapy whether structural integration or massage, has the goal of

supporting the client’s body to heal—to feel great. Perhaps what we are doing as

somatic educators is pointing the client’s attention (which has often wandered)

back to their own precious body. (p. 1)

Soma is a method that takes place in 10 sessions to align the connective tissue of

the body to function as it was biomechanically designed to function, with an optional

27

11th session for further integration, known as Somassage®. Clients experience body

reading; fascial manipulation on a massage table; are guided to practice integrative

movement exercises; draw their bodies before and after sessions; and have the ability to

utilize a client notebook throughout the 10-11 sessions. Soma Neuromuscular

Integration® deep tissue massage encapsulates processes that address mind, body, and

emotions by accessing the fascial web that wraps every organ and links every muscle

(Bolesky, 2004). Thus, working one part of the fascial web influences associated parts

elsewhere in the body. The deep tissue massage releases trauma from the fascia and

connective tissue that hold body memories and associations.

Authentic Movement. Authentic movement opens the body into a state of free

association in which the contents of the psyche translate into spontaneous movement,

vocalizations, and emotions, and are witnessed by an observer (Konopatsch & Payne,

2012). Founder of authentic movement and dance therapist Mary Whitehouse (2007)

initially conceptualized this method of work through her own journey as an analysand in

Jungian therapy where she was inspired by the relationship between active imagination

and free association of movement (Konopatsch & Payne, 2012). Psychiatrist Carl Jung

(1956/1970) developed the process of active imagination in which one focuses on a

dream or fantasy as reflective of “psychic processes in the unconscious background,

which appear in the form of images consisting of conscious memory material. In this way

conscious and unconscious are united, just as a waterfall connects above and below” (pp.

495-496).

In this way of connecting above and below, conscious and unconscious, implicit

memory with explicit memory, practicing authentic movement in individual or group

28

settings offers a new way to communicate within oneself and with the therapist

facilitating the session (Konopatsch & Payne, 2012). Often there is music playing that

helps to evoke kinesthetic and emotional experiences across a range from sorrow to

ecstasy. “Authentic movement, as an approach to self-exploration, intends to create a

space for hidden, unconscious and sensitive personal themes to be explored. The ground

form of Authentic Movement involves two people, termed ‘mover’ and ‘witness’”

(Konopatsch & Payne, 2012, p. 342). Authentic Movement can evoke the release of

many forms of trauma as the mover is silently received by the witness. If there are body

issues, shame might arise, followed by tears, or sighs—small movements or sweeping

gestures. The witness acts as a source of loving presence and affirmation, which in

redressing issues of traumatized attachment, is cathartic in and of itself.

Attachment and Bonding: What Love Has to Do With It

Clinical psychologist and founder of emotionally focused therapy (EFT) Sue

Johnson (2013) wrote, “We need emotional connection to survive. Neuroscience is

highlighting what we have perhaps always known in our hearts—loving human

connection is more powerful than our basic survival mechanism: fear. We also need

connection to thrive” (p. 23). There are many components to self-regulation that dovetail

with attachment and bonding. There seems to be a correlation between affect regulation

and the ability to experience self-love and self-worth (Bram & Peebles, 2014, p. 255).

“These states of mind can be based on secure attachment experiences in which we feel

seen, safe, soothed, and secure—the ‘four S’s of attachment’ that serve as the foundation

for a healthy mind” (Siegel, 2013, p. xiii). For those who did not grow up with

relationships that facilitated feeling securely attached, indeed there is hope. There is

29

recognition among many experts in the fields of psychology and neuroscience that secure

attachment can be cultivated at every phase of development throughout one’s lifespan

(Crain, 2011; Johnson, 2013; Siegel, 2012). Chapter III builds on the research discussed

above in presenting an analysis of the creation of a sacred space that provides for the four

S’s of attachment.

Chapter III

Findings and Clinical Applications

Encountering the Sacred Temenos

The body is a multilingual being. It speaks through its color and its temperature,

the flush of recognition, the glow of love, the ash of pain, the heat of arousal, the

coldness of non-conviction. It speaks through its constant tiny dance, sometimes

swaying, sometimes a-jitter, sometimes trembling. It speaks through the leaping

of the heart, the falling of the spirit, the pit at the center and rising hope.

C. P. Estés, 1992, p. 200

To approach the human body with a sense of its dynamic, awe-inspiring, and

wondrous nature allows for the sacred to enter back into the practice of psychotherapy

and somatic psychology. I think the word sacred has become loaded with religious

connotations—whether favorable or unfavorable. But I would like to resurrect the word

sacred to mean a deep sense of honoring soul essence. Moore (1992) wrote, “Soul has to

do with genuineness and depth, as when we say certain music has soul or a remarkable

person is soulful. Soul is revealed in attachment, love, and community” (p. xii). When I

conceptualized the title of this thesis as Encountering the Sacred Temenos: Somatically

Integrating Cumulative Trauma and Discovering Wellbeing Within, I very consciously

added the word sacred. To me being invited to witness the inner and confidential

processes of a client or a friend or family member is an honor and in that way sacred. The

word sacred comes from the antiquated verb sacren “to make holy” and from the “Latin

sacrare, to make sacred, consecrate; hold sacred; immortalize; set apart; dedicate”

(Harper, 2017, para. 1). It is my belief that life and all of nature is miraculous and I

31

intentionally chose to elevate the safe container and the members held within it to honor

the presence of soul and spirituality.

Levine (2010) concurred about spirituality as an essential focus in trauma work

when he wrote, “In a lifetime of working with traumatized individuals, I have been struck

by the intrinsic and wedded relationship between trauma and spirituality” (p. 147). What

he meant by this was that the process of catharsis from wounding to releasing trauma to

reintegrating into wellbeing has brought profound and spontaneous expressions of

ecstatic joy, tears of gratitude, and “an all-embracing sense of oneness” (p. 147). This can

occur for clients, health professionals, wilderness therapy guides, and therapists who

witness and help to facilitate such a metamorphosis. I have experienced this in my own

practice as a body and energy work practitioner as well as in my training to become a

psychotherapist.

Somewhere along the way, in modern society, government, and the insurance

industry, the broad recognition of sacredness and soul in therapy got lost as an overall

tenet to treating emotional balance and wellbeing. This is true of the healing that occurs

in the myriad of modalities that tend to the body and mind. In ancient Greece there were

references to healing temples, places of great beauty and architecture with fountains and

interior courtyards—a temenos-like space in honor of the healing gods and goddesses in

the polytheistic pantheon such as Hygiea and Asclepius (Campbell, 2013, pp. 120-121).

The word temenos originates from the ancient Greek notion of a sacred healing temple

and, according to Jungian analyst Daryl Sharp (1991), when defined in a Jungian sense it

means “a sacred, protected space; psychologically, descriptive of both a personal

container and the sense of privacy that surrounds an analytical relationship” (p. 133).

32

Jungian analyst and somatic therapist Jean Chodorow (1991) defined working with the

concept of a temenos as “a safe and secure space within which unconscious fantasies and

conscious dilemmas can be safely dealt with. The nature of this dialectic between patient

and therapist is fostered by an empathic mirroring on the part of the therapist” (p. 7).

The term temenos as I use it is a place of safety and wholeness where the sacred

work of depth psychotherapy can occur—honoring the ancient tradition of creating an

exalted space. This creation of a temenos can happen in a windowless office on the

corner of a busy street in a community mental health clinic. I make use of soft lighting,

images of peace in nature on the walls, comfortable seating, plants that detoxify and

oxygenate the air in the room, and work with a steady and calm tone of voice as subtle

influences in the creation of a temenos. Yet above all, creating a temenos is about the

energetic held by the therapist, facilitator, or health professional. Being surrounded by the

beauty of nature or in an architecturally uplifting space certainly adds to the creation of

such energy, but it is not essential. The sacred temenos is largely about intentionality.

Historian and archeologist Asia Shepsut (1993) acknowledged the universe and Earth as

macrocosmic representations of the sacred temenos and spaces created to reflect the sense

of being held as microcosms of that greater, cosmic container. Shepsut furthered this

concept when she explained,

Wherever it is, however you do it, create some spot which ritualizes The Centre of

the World. . . . You will notice that creating this sacred space will have an

immediate, regulating effect on activities of a more practical nature that go on

outside it. (p. 29)

One of the primary clinical or facilitative functions of the creation of a temenos is

to create a sense of emotional safety where deeper and more vulnerable layers of human

33

experience, inclusive of cumulative trauma, can be revealed while being securely

contained by the loving presence of the therapist or other health professional.

Trauma as Cumulative and on a Continuum

Both PTSD and developmental trauma are considered macro levels of trauma,

but if trauma is seen on a continuum, varying degrees of micro traumas may occur in

which an event causes subtle neurophysiological fear reactions. There are professionals

and individuals in all walks of life who have encountered various forms of trauma or

traumatic stress and these instances can occur at any time in one’s lifespan (Parnell,

2013; van der Kolk, 2014). An employer, spouse, professor, or other person in power can

be an influential figure in relational micro or macro trauma for an adult, just as a parent

can be a tremendous source of wounding for a child (Parnell, 2013). After years of

accumulated micro traumas, peoples’ ways of relating to others and to themselves can

become in a sense clogged or distorted and in need of relief from the struggle to maintain

emotional equilibrium and defend against further trauma.

Psychotherapy and somatic modalities that address trauma are ways to work with

transforming cumulative trauma. Aron (2010) further clarified and broadened the

definition of the forms of trauma people experience: