Learning Communities Research and Practice

Volume 7 | Issue 1

Article 5

6-6-2019

Indexing: Narrating Interdisciplinary Connections

in the Classroom

Jack J. Mino

Holyoke Community College, jmino@hcc.edu

Elizabeth Trobaugh

Holyoke Community College, etrobaugh@hcc.edu

Steven Winters

Holyoke Community College, swinters@hcc.edu

James Dutcher

Holyoke Community College, jdutcher@hcc.edu

Recommended Citation

Mino, J. J. , Trobaugh, E. , Winters, S. , Dutcher, J. (). Indexing: Narrating Interdisciplinary Connections in the Classroom. Learning

Communities Research and Practice, 7(1), Article 5.

Available at: https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

Authors retain copyright of their material under a Creative Commons Non-Commercial Attribution 3.0 License.

Indexing: Narrating Interdisciplinary Connections in the Classroom

Abstract

An integrative tool that we have piloted in two LCs, the interdisciplinary index, is an integrative template that

students use to make connections between disciplines. In the learning community, “Cli-Fi: Stories and

Science of the Coming Climate Apocalypse,” faculty developed the Climate-Change Stress Index (CCSI) that

students used to identify evidence of climate-change impacts in the fictional setting of each novel they read. In

another learning community, “All things Connect: Living with Nature in Mind,” students again used an index

consisting Ecopsychology principles to describe, explain, and/or evaluate how these principles informed

excerpts from environmental literature. We present a variety of student samples using Barber’s (2012) model

of integrative learning and conclude with a review of the functions of interdisciplinary indexing.

Keywords

interdisciplinary indexing, integrative learning, Ecopsychology, Cli-Fi or climate change fiction

Cover Page Footnote

We would like to acknowledge and thank our wonderful learning community students – “Cli-Fis” and

“Connectors” - for their remarkable engagement and integrative brilliance.

Article is available in Learning Communities Research and Practice: https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

Mino et al.: Interdisciplinary Indexing

Integrative learning doesn’t just happen. Students need to be taught how to

integrate, and this effort requires work from everyone involved (Huber,

Hutchings, & Gale, 2005; Klein, 2005). If we are going to teach students how to

integrate their learning, Bass and Eynon (2009) argue, we need to value the

intermediate learning processes that lead to summative student work, not just

outcomes. So what do these so-called “intermediate learning processes” look like?

Barber (2012) provides us with a useful framework for categorizing how

students integrate their learning over time, i.e., how they “bring together

experience, knowledge, and skills across contexts” (p. 9). He identifies three

distinct developmental stages of integration that emerged from his interviews with

undergraduate students from liberal arts colleges: (1) connection, the discovery of

a similarity between ideas that themselves remain distinctive; (2) application, the

use of knowledge from one context in another; and (3) synthesis, the creation of

new knowledge by combining insights. Based on Barber’s framework, we used

interdisciplinary indexing as a scaffolding strategy to integrate science and

literature in our Learning Community (LC) classrooms at Holyoke Community

College (HCC) and in the process uncovered how students developed integrative

habits of mind over the course of a semester.

Indexing can serve as a powerful teaching and learning tool that gives

students an easy way to begin integrating ideas. Through indexing, students work

individually and in small groups to create a public archive of interdisciplinary

connections that can be used for future integrative assignments, such as

seminaring, synthesis papers, and research presentations. Making the "how" as

well as the "what" of integrative learning visible, indexing reveals students’

formative understanding of the connections between disciplines, moving “beyond

conversational activity [by] creating occasions for students to harvest learning

from the visibility of their own thinking” (Bass & Eynon, 2009, p. 15).

Demonstrating the flexibility and wide applicability of this teaching tool, indexing

has become a common practice among LC faculty at HCC.

While teaching an interdisciplinary course on climate change fiction (an

offshoot of science fiction), two of us, Steven Winters and Elizabeth Trobaugh,

invented the indexing tool that we now use in a variety of LC settings. The idea is

loosely based on the notion of “index fossils,” common in paleontology: “While

every fossil tells us something about the age of the rock it's found in, index fossils

. . . are those that are used to define periods of geologic time” [emphasis added]

(Alden, 2018).

In the spring of 2015, Winters developed geoscience computer labs called

the “Geography of the Anthropocene,” which used Google Earth to locate real

geographical sites referenced in our climate change fiction (Cli-Fi). We were

motivated, in part, by our textbook, Environmental Transformations by Mark

Whitehead (2014). Whitehead’s book is not a text on the geoscience of climate

1

Learning Communities Research and Practice, Vol. 7 [], Iss. 1, Art. 5

change as such but a text on the geography of climate change; his point is that, as

a geographer, the where of climate change (or the Anthropocene) matters as much

as the what of climate change/the Anthropocene.

In the early version of the index assignment, students used Google Earth for

three separate “laboratory exercises.” In one, they located the actual places

referred to in the stories and novels we studied. To help students understand how

texts (such as fiction, science, and history) are connected to mappable locations

and concepts, we asked them to fill out a chart we titled “Literary Field Trip.” As

part of this assignment, students kept Cli-Fi charts to record their observations

and, most importantly, reflect upon and connect their observations to the fiction.

For the second exercise, students used Google Earth to explore one of five Cli-Fi

science/literature themes and reported back to the class. For the third, they wrote

jourmal entries about a location/place in the world that could serve as a rich

setting for a Cli-Fi story. For example, they could select a location with natural

resources that might be subject to scarcity or abundance or a location that could

be impacted by rising sea levels, ocean acidification, increased temperature, etc.

To accomplish this task, students were expected to use what they had learned thus

far in the course.

While the laboratory exercises were valuable, we wanted to extend the

experience of connecting themes beyond the lab activity and into the classroom

(without Google Earth). Because we also wanted to retain the

presentation/collaboration dimension of the exercise, we developed a template

with a fixed list of themes that students would look for in the assigned stories or

novel and then share with the class by posting their textual observations to a

common document in Google Drive. For convenience, and to help students better

focus on important environmental/social aspects of climate change problems, we

renamed our list of topics or themes to a simple easily remembered phrase: the

Climate Change Stress Index or CCSI. As with index fossils, every climate

change observation or index tells us something about the extent of the global

problem.

What follows are case examples from two Holyoke LCs that used indexing

to promote integration between literature and science. In the first case study,

CliFi: Stories and Science of the Coming Climate Apocalypse (English literature

and earth science), students used the Climate Change Stress Index (CCSI) to

identify the evidence of climate-change impacts in the fictional setting of each

work of literature (e.g. novel or short story) they read (see Appendix 1). In the

second case, All Things Connect: Living with Nature in Mind (environmental

literature and ecopsychology), students used a revised version of the CCSI, an

Ecopsychology Index, which consisted of eight principles that they applied to

environmental literature, including novels and poetry (see Appendix 2). For each

case study below we present samples of student indexing and use the integration

https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

2

Mino et al.: Interdisciplinary Indexing

framework from Barber (2012) to classify them. We conclude with a discussion

of the functions of indexing, including its uses as a narrative and a classroom

exercise, an archive, and a form of priming higher order integrations.

Case Example 1: Cli-Fi: Stories and Science of the Coming Climate

Apocalypse

Cli-fi is where art meets science, where data meets emotions, and where

science meets art, too.

–Daniel Bloom, “How and Why Sci-Fi Gave Birth to Cli-Fi,” 2014

Responding to the challenges of teaching geoscience in the liberal arts

setting, we have developed an interdisciplinary course that fulfills both lab

science and English graduation requirements. At HCC, we team teach a course

called Cli-Fi: Stories and Science of the Coming Climate Apocalypse. “Cli-Fi”

refers to climate change fiction, a now popular subgenre of science fiction. Our

course combines introductory literature and composition with first-year physical

geology (including laboratory and field exercises). With interdisciplinary/thematic

content and a seminar-style learning environment, our course attracts a variety of

students—science majors, English majors, environmentalists, and science fiction

fans. In multidisciplinary learning communities (LCs), students might

understandably wonder (we all might wonder!) how earth science and English can

be connected or how a novel could help to open up some complicated research in

ecopsychology. Using the index gets students started in integrated thinking by

giving them an easy checklist to follow: here are nine impacts, or eight principles,

to look for while reading.

In this course, we read Paolo Bacigalupi’s Cli-Fi novel The Windup Girl and

shorter works from recently published anthologies. Standard college-level

geology texts and excerpts from science magazines and journals complement our

literary readings. To help students focus on climate change impacts and themes in

each story, we ask students to locate, record, and describe several features of the

climate-changed world, such as adaptation/mitigation, breakdown in

civilization/social order, climate imbalance/disorder, extinction, illness/disease,

and resource scarcity.

This stress-index technique helps us use Cli-Fi’s settings, plots, and

characters not just as jumping off points for general discussion but as windows

through which students get an integrated view of science and fiction in one lesson.

For example, when reading The Windup Girl, students notice that resource

scarcity, specifically the scarcity of fossil fuels, not only propels the plot but also

leads to technological regression: in the world Bacigalupi has created, machines

run on animal and human power rather than on electricity or fossil fuel. This

adaptation has the benefit of reducing carbon emissions in a runaway greenhouse

3

Learning Communities Research and Practice, Vol. 7 [], Iss. 1, Art. 5

atmosphere, but it also places a premium on calories in a climate-changed world

of extinctions and agricultural plagues. Identifying real climate science in a

literary text motivates students to take the projected outcomes of climate change

fiction seriously and to engage critical thinking and research skills to assess a

story’s verisimilitude. The CCSI marks the beginning of the students’ critical

analysis of the climate fiction and acts as a window through which students can

develop an integrated and in-depth view of fiction and science in one lesson. The

CCSI lists nine climate-change impacts on society and on the natural world:

1. adaptation/mitigation,

2. breakdown in infrastructure,

3. breakdown in civilization/social order,

4. climate imbalance/disorder,

5. ecosystem imbalance—flora and fauna,

6. illness/disease,

7. positive/negative feedbacks,

8. regression (psychosocial, biological, technological, etc.), and

9. resource scarcity.

With the CCSI serving as both a reading guide and a weekly credit-bearing

assignment, students approach the text with a mission: to search for evidence of

climate change impacts. Below, in the first of two examples from Clif-Fi, we see

one student apply the CCSI to The Windup Girl by selecting a passage that

illustrates technological regression (impact #8 on the index) due to environmental

degradation and resource scarcity (impact #9). The student identifies textual

evidence, practices quotation integration skills by using the MLA documentation

format, and provides an analysis of the passage using both a literary and a climate

change lens. In this analysis, we see the student’s recognition of the author’s

literary goal—using a bicycle and draft animals to show the impact of fuel

scarcity—as well as the ability to integrate the course’s two disciplines—literature

and science—through recognizing in a work of fiction how pollution and resource

scarcity may force society into technological regression.

Student-selected Quotation: “He stands on his pedals and accelerates again,

forcing the bike through the clotted traffic calling out warning and curses at

obstructing pedestrians and draft animals” (123).

Student Response: I see this as a regression in technology because we are so

used to cars as a society. We don’t bat an eye when we get in the car leaving

behind all the pollution that cars create. It helps create an understanding of

the story and how it really is affected by the climate, and how they must

regress in terms of technology to help combat negative climate change.

Encouraged to make use of the CCSI in developing their essays, students

benefit from their classmates’ contributions and insights. The sample below, from

https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

4

Mino et al.: Interdisciplinary Indexing

another student’s essay about The Windup Girl, illustrates how the communal

archive of evidence and integrated analysis can support students as they move

from reading and evidence gathering to synthesis and essay writing.

Student-selected Quotation: “The genehacked animals comprise the living

heart of the factory’s drive system, providing energy for conveyor lines and

venting fans and manufacturing machinery” (9).

Student Response: In Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl we encounter

numerous examples of regression and adaptation that take place in the

climate-changed setting of Bangkok. The main conflict is the decrease in

resources these people have, including the decline of fuel. In order for

people to remain progressive, they had to adapt to the new ways of life that

excludes any reliability on fuel. Instead of burning it up to power factories,

they created a creature that would do the manual labor for them. These

creatures are called Megodonts who were manufactured for hard labor to

make human lives a little easier.

These elephant-resembling creatures are a pure form of regression because

they are made to withstand a great deal of labor, putting forth enough energy

the people need to continue to work. Another adaptable regression in “The

Windup Girl” is the means of transportation for the people living in

Bangkok. No more fuel means no more cars, planes, or ships. People have

resorted to bikes that can also help people get from one place to another,

aiding in the drivers income. Bikes are also so common that they form their

own traffic. Bacigalupi writes, “The old man stands on his pedals and they

merge into traffic. Around them, bicycle bells ring like cibiscosis chimes,

irritated at their obstruction. Lao Gu ignores them and weaves deeper into

the traffic flow” (5). The streets of Bangkok are bustling with bicycles and

their passengers quickly trying to get to their next destination, so they can

escape the harsh sun. These two examples of regression are only the

beginning of adaptation we see in Bacigalupi’s story because the people of

Bangkok are resilient in their ways.

This excerpt demonstrates the student’s familiarity with the text, possibly

enhanced by access to the CCSI archive, the ability to connect the two disciplines,

and a higher-level understanding of the connection between resource scarcity and

technological regression.

Our curriculum combines the techniques of critical thinking and textual

analysis from the sciences and the humanities. The fictional settings and scenarios

of Cli-Fi expand the imagination and show geoscience principles in a fictional

context, inviting students to confront the role of humanity in a climate-changed

world and perhaps inspiring students to learn more about how humanity might

cultivate a more cooperative relationship with the Earth.

5

Learning Communities Research and Practice, Vol. 7 [], Iss. 1, Art. 5

Case Example 2: All Things Connect: Living with Nature in Mind

The deep and enduring psychological questions–-who we are, how we grow,

why we suffer, how we heal–-are inseparable from our relationships with

the physical world. Similarly, the overriding environmental questions–-the

sources of, consequences of, and solutions to environmental problems–-are

deeply rooted in the psyche, our images of self and nature, and our

behaviors.

–John Davis, “A Definition of Ecopsychology,” 2013

All Things Connect: Living with Nature in Mind integrates environmental

literature with ecopsychology. In his classic essay, “The Land Ethic,” Aldo

Leopold (1949) argues that to effect meaningful change in the world, we need to

focus not just on people’s behavior but on their “intellectual emphasis, loyalties,

affections and convictions.” How do we do that? One way is through good

scientific research, theorizing, and argumentation, activities that form the core of

ecopsychology. Another way is through meaningful accounts of people’s

experience in nature—sometimes beautiful, sometimes frightening, but always

offering us insight into our deep connection with a living earth. Drawing from

Roszak (1992), Mino and Dutcher adapted the indexing exercise by creating an

“ecopsychology index” with the eight principles listed below. Students were

asked to look for sections of the assigned readings that illustrated or exemplified

these principles.

1. The core of the mind is the ecological unconscious.

2. The contents of the ecological unconscious represent the living record

of evolution.

3. The goal of ecopsychology is to awaken the inherent sense of

environmental reciprocity that lies within the ecological unconscious.

4. The crucial stage of development is the life of the child.

5. The ecological ego matures toward a sense of ethical responsibility

with the planet.

6. Ecopsychology needs to re-evaluate certain “masculine” character

traits that lead us to [try to] dominate nature.

7. Whatever contributes to small-scale social forms and personal

empowerment nourishes the ecological ego.

8. There is a synergistic interplay between planetary and personal well

being.

Having read Not Wanted on the Voyage (Findley, 1984/2006), students,

working in groups of three, selected a quotation that highlighted the conflict felt

by one of the novel’s main characters, posted it in MLA format, and then

responded to it. By analyzing that quotation in terms of one of the principles from

ecopsychology—“The contents of the ecological unconscious represent the living

https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

6

Mino et al.: Interdisciplinary Indexing

record of evolution”—one student makes what Barber (2012) calls the first

integrative move, connecting the idea of symbolic representation in literature with

the idea of the ecological unconscious from ecopsychology.

Student-selected Quotation: “I was born, the trees were always in the sun . .

. . I left that place because it was intolerant of rain. Now we are here . . .

where there are no trees and there is only rain . . . . I intend to leave this

place . . . there must be somewhere where darkness and light are reconciled”

(Findley 272).

Student Response: Lucy is the living record of evolution. She lived in two

separate worlds; her prior world where there was only light and in this

current where there is only darkness. She is the “unconscious” because she

is an angel. She isn’t a real person like the Noyes family. She is the symbol

that connects the evolution of all of the past world, the current world she is

in and the future world she wishes to live in.

An indexing sample from another group of students illustrates their ability

to move beyond connecting to applying. Students selected from the Tao Te Ching

(Lao Tzu, 1989) to respond to the ecopsychology principle, “Whatever

contributes to small scale social forms and personal empowerment nourishes the

ecological ego”:

Student-selected Quotation: “It [water] goes right to the low loathsome

places, and so finds the way” (11).

Student Response: Lao Tzu mirrors an alchemist axiom, ‘in sterquilinus

invenitur,’ when he writes, “It [water] goes right to the low loathsome

places, and so finds the way” (11). Water offers no resistance to gravity’s

pull to the undesirable low places. The axiom is generally interpreted as

personal growth will be found where you don’t want to look. The abuse of

the environment stems from people’s quest to elevate their place in life and

avoid those places that they don’t want to look. If people look to their

personal empowerment without fear, like the water, the need to consume the

environment is largely alleviated.

Here the students’ application of the Latin phrase in sterquilinus invenitur, which

translates as “in filth it shall be found,” uses knowledge from one context in

helping to understand another, thus attaining Barber’s (2012) second stage of

integration. In fact, the application in this indexing sample is very sophisticated in

that it combines knowledge from three different contexts, the Tao Te Ching,

alchemy, and ecopsychology.

The third and final indexing sample from All Things Connect is a lengthy

excerpt from a student’s final synthesis essay based on Solar Storms (Hogan,

1995). In this sample, the student’s work demonstrates the third stage of

integration or synthesis according to Barber (2012). Combining ideas and insights

7

Learning Communities Research and Practice, Vol. 7 [], Iss. 1, Art. 5

from literature (the quotation “opening light of life”), ecofeminism (e.g., female

identification with nature), and ecopsychology (e.g., the ecological unconscious),

she creates new knowledge by means of phenomenology or embodied experience.

Student-selected Quotation: Wednesday was the last day we called by name,

and truly, we no longer needed time. We were lost from it, and lost in this

way, I came alive . . . Cell by cell, all of us were taken in by water and by

land, swallowed a little at a time . . . Field, forest, swamp. I knew how they

breathed at night, and that they were linked to us in that breath. It was the

oldest bond of survival . . . Somewhere in my past I had lost the knowing of

this opening light of life, the taking up of minerals from dark ground, the

magnitude of thickets and brush. Now I found it once again (Hogan 170-

171).

Student’s First Response: The characters of the book [Solar Storms] and

their histories are riddled with scars from the exploitative and divisive,

decidedly masculine, way of living by which they are surrounded. And yet,

in a transformative canoe trip north through Canada, the women free

themselves of the weight of those scars. They experience the natural world

so deeply that they are able to connect to their native roots and the world

around them in an entirely holistic way.

Student’s Second Response: Getting lost on their canoe trip, the women

rediscovered their intimate connection to the life-giving forces of the earth,

the “opening light of life,” that they themselves were a part of (Hogan 171).

It is through experience that this bond is discovered and nourished. What

this book describes is a conversation between the earth and self, a

reawakening through experience of the unique feminine bond with the earth

as givers and protectors of life. The human artifice falls away and with it the

socially constructed separation between self and nature; what emerges is an

acute sense of reciprocity with the natural world and a distinctly feminine

identity forged through embodied experience.

Students in the All Things Connect LC read five novels, a play, and a

selection of poems, all addressing environmental themes. They then used the

Ecopsychology Index as an integrative lens to describe, analyze, and explain how

the literature connected to eight principles of ecopsychology. As the student

samples above indicate, with repeated practice, students began making more

advanced integrative moves. And as the semester came to an end and the final

research paper came due, we observed more and more students creating new

knowledge via synthesis.

https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

8

Mino et al.: Interdisciplinary Indexing

Discussion: Functions of interdisciplinary Indexing

It’s clear from these samples of student work that indexing facilitates

interdisciplinary integration on multiple levels from connection to application and

synthesis. Notice that, in the examples from both LCs, the students have to match

passages from their reading to an index, and they also have to explain the match

in their own words. This exercise in synthesis happens both individually, as

students do their homework, and collaboratively in class when they work together

in groups of two or three to find passages in the day’s reading that exemplify one

or more items on the index. In those situations, the index is a working document

at the front of the class; as students make a match, we can all watch as they type,

in real time, a passage from the text and their explanation of how it illustrates the

index principle. This, in turn, is the beginning of their own synthesizing of

disciplines. We have found that, in this collaboration, the better or more prepared

readers help their partners, which encourages the less-prepared students to

participate more actively the next time.

In addition, the results of the small groups’ work is not only projected in the

classroom, it is saved to Moodle or Google docs, which serves as an archive of

pairings available for further integration. A student who might be working on a

“synthesis” essay and might want to explore the connection between various

novels and plays with the ecopsychology principle of reciprocity between humans

and their natural environment can find an index on Moodle that is already filled

with examples from Not Wanted on the Voyage, Solar Storms, or the Tao Te

Ching. Each student participated in making these documents, and each is also

benefiting from the work of the other students, in collaboration.

Beyond helping students connect, indexing provides students with an easy

guide toward integration, e.g., there are a number of geoscience /ecopsychology

principles, and the students have to find those principles in the literature. Because

it asks students to connect only two dots at a time, this task is specific and

accessible, with the added benefit of turning a textual evidence exercise into a

treasure hunt. We see from the case examples that, by connecting different kinds

of knowledge, students frequently unearth and develop powerful observations—

especially when they have to explain the connection between the principle and the

passage. This step is crucial in the development of integrative skills.

The indexing assignment also promotes the habits of close reading and

making connections. Using indexing as a semester-long foundation for inquiry

and discussion gives students the opportunity to practice and master the skill of

making connections, with the added challenge of applying the principles of one

discipline (science, social science) to another (literature). While the work of

literature (or text) changes from exercise to exercise, the indexing process remains

the same, so students get to practice the skills of close reading, connecting, and

9

Learning Communities Research and Practice, Vol. 7 [], Iss. 1, Art. 5

synthesizing repeatedly throughout the semester. As an exercise that targets

connection building, indexing supports and even deepens the practices of active

reading and note taking.

In addition, having a written and shared record of connections helps students

move from connecting just two dots, for instance, ecopsychology principle #1 to

the canoe trip in Solar Storms, to connecting multiple dots because they have

connected ecopsychology principle #1 not just to Solar Storms but also to Not

Wanted on the Voyage as well as to other readings in the course like Siddhartha

(Hesse & Rosner, 1951) and Ishmael (Quinn, 1992). So the integrative moves

from no dots to two dots to multiple dots happen in plain sight in real time. This

process shows Barber’s claim that “[t]here is a developmental process at work in

relation to integration of learning, meaning that it evolves over time” (2012, p.

601). The “indexing archive,” then, can be read as a collective narrative of the

evolution of integrative learning over the course of the semester.

When we look at indexing as an integrative process, we recognize several

distinct insights about integrative learning. There’s one story to tell about how

individual students learn to integrate between disciplines (i.e., a focus on

individual students). Like Barber (2012), we have found that first-year and

second-year college students varied greatly in their abilities to integrate academic

material between disciplines, and student characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race,

ethnicity, SES) indicated important differences in how students integrated their

learning. There’s another story to tell about how the class as a whole performs

over time across a semester (i.e., a focus on group differences). Tracking overall

class performance suggested trends in the development of students’ levels of

integrative learning, where most students made connections early in the semester,

moving to application by mid-semester, and achieving synthesis most frequently

by the end of the semester. There’s yet another story to tell about how different

LC classes compare across the curriculum (i.e., a focus on between-group

differences). When we compared the first-year Cli-Fi LC to the second-year All

Things Connect LC, we found that the more experienced students (from the

second-year LC) started out with higher levels of integration, advanced at a faster

rate over the course of the semester, and engaged in synthesis more frequently,

transferring their learning to more complex integrative assignments.

What these stories reveal about how students’ integrated their learning over

time is predicted by Barber’s (2012) theory and supported by his findings—

students became stronger and more confident with regular practice. In effect,

interdisciplinary indexing provides the routine and foundation for a continuous

iterative scaffolding process that promotes integrative learning and transfer (p.

611).

We believe indexing is a highly accessible and adaptable instructional

practice that supports learning in any classroom but especially in the LC

https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

10

Mino et al.: Interdisciplinary Indexing

classroom where a primary objective is to uncover and forge connections between

disciplines and forms of inquiry. Thus, indexing can serve a variety of important

pedagogical functions, including:

• Narrating: By selecting relevant passages from the literary text

and explaining how a particular scientific principle applies,

students create a collective public narrative of the class’s

understanding of how science and literature connect.

• Exercising: Indexing can be used as a formative exercise in the

classroom where students practice their emerging integrative skills

aided by immediate feedback and coaching from faculty as well as

their classmates.

• Archiving: Using Google Docs, students create a digital archive to

publicly record their responses in real time and store them for

future referencing.

• Priming: Indexing also serves to “prime” students to make explicit

connections as they read and write in preparation for class

discussions and to draw on for other higher-stakes assignments,

such as writing essays.

Conclusion

Over the years, a variety of valuable pedagogical tools have emerged from

LC practice and research. The “Heuristic for Teaching, Assessment, and

Curriculum Design” by Malnarich and Lardner (2003) is a classic in LC course

design. And “A Workbook for Designing, Building, and Sustaining Learning

Communities” is an essential LC professional development resource that “walks

instructors through the collaborative process of creating and sustaining successful

links and focuses on what we believe is the heart of learning community work—

transparency, relationship building, integration, assessment, and reflection”

(Graziano, Schlesinger, Kahn, & Singer, 2016, p. 1). Similarly, a number of

useful instruments that focus on assessment emerged initially from practices. The

“Collaborative Assessment Protocol” outlines a process for the collective

examination of interdisciplinary student work, while the “Peer to Peer Reflection

Protocol” assesses collaborative learning and was designed to be used as a

companion tool with the Online LC Student Survey (Malnarich, Pettitt, & Mino,

2014, p. 20). Documentation as a process of gathering evidence and artifacts of

what happens in the LC classroom can fulfill multiple functions, including that of

an instructional practice, assessment strategy, and research method (Mino, 2014).

Interdisciplinary indexing is another development in this tradition. Indexing

gives students a specific map, or checklist, to use to begin integrative thinking.

With an index in front of them, students can read one discipline or another and

11

Learning Communities Research and Practice, Vol. 7 [], Iss. 1, Art. 5

begin to pair passages and examples from their reading to one or more items on

the index. It is worth noting that Winters and Trobaugh developed and refined the

indexing exercise through teaching together for several years in a row, and they

shared their indexing tool with the LC teaching community at an LC retreat, an

example of collaboration, cross-pollination, and dissemination that occurred

within the context of institutional financial and philosophical support and

commitment. The result of this effort is a teaching strategy for faculty and a

hands-on learning strategy for students to integrate knowledge across disciplines

and over time. While we have used it for scaffolding student learning, we see as

well that it is a multi-purpose tool that could be used for assessing, and

researching how students integrate their learning. LC pedagogy includes course

templates, assignment heuristics, assessment protocols, documentation, and now

indexing—yet another useful integrative resource to add to our LC tool kit.

References

Adams, J., (Ed.) (2015). Loosed upon the world: The saga anthology of climate

fiction. New York: Saga Press.

Alden, A. (2018, December 25). “How index fossils help define geologic time.”

Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/what-are-index-fossils-1440839

Bacigalupi, P. (2015). The windup girl. New York, NY: Night Shade Books.

Barber, J, (2012, June). Integration of learning: A grounded theory analysis of

college students’ learning. American Educational Research Journal, 49(3),

590–617. doi: 10.3102/0002831212437854

Bass, R. & Eynon, B. (2009). Capturing the visible evidence of invisible learning.

In R. Bass & B. Eynon (Eds.) The difference that inquiry makes: A

collaborative case study of technology and learning, from the Visible

Knowledge Project. Academic Commons. Available at

https://web.archive.org/web/20100702230109/http://www.academiccommo

ns.org/files/BassEynonCapturing.pdf

Bloom, D. (2014, December 14). “How and why sci-fi gave birth to cli-fi.”

Teleread. Retrieved from http://teleread.com/how-and-why-sci-fi-gave-

birth-to-cli-fi/index.html

Davis, J. V. (2013). A definition of ecopsychology. Retrieved from

http://www.johnvdavis.com/Ecopsychology.html

Findley, T. (2006). Not wanted on the voyage. Toronto, Canada: Penguin Canada.

(Original work published 1984)

Graziano, J., Schlesinger, M. R., Kahn, G., & Singer, R. (2016). A Workbook for

designing, building, and sustaining learning communities. Learning

Communities Research and Practice, 4(1), Article 6. Available at:

https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol4/iss1/6

https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

12

Mino et al.: Interdisciplinary Indexing

Hesse, H., & Rosner, H. (1951). Siddhartha. New York, NY: New Directions

Publishing.

Hogan, L. (1995). Solar storms. New York, NY: Scribner.

Huber, M. T., Hutchings, P. & Gale, R. (2005). Integrative learning for liberal

education. Peer Review 7 (4): 4–7.

Klein, J. T. (2005). Integrative learning and interdisciplinary studies. Peer Review

7 (4): 8–10.

Lao Tzu (1989). Tao te ching. Trans. Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English. New York,

NY: Vintage.

Leopold, A. (1949). A sand county almanac and sketches here and there. New

York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Malnarich, G. & Lardner, E. (2003). Designing integrated learning for students: A

heuristic for teaching, assessment and curriculum design. Washington

Center Occasional Paper. Number 1, pp. 1-9.

Malnarich, G. , Pettitt, M. A. , Mino, J. J. (2014). Washington Center’s online

student survey validation study: Surfacing students’ individual and

collective understanding of their learning community experiences. Learning

Communities Research and Practice, 2(1), Article 1. Available at:

http://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol2/iss1/1

Mino, J. J. (2014). Now you see it: Using documentation to make learning visible

in LCs. Learning Communities Research and Practice, 2(2), Article 6.

Available at: https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol2/iss2/6

Quinn, D. (1992). Ishmael. New York, NY: Bantam.

Roszak, T. (1992). The voice of the earth. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Strahan, J. (Ed.), (2016). Drowned worlds: Tales from the Anthropocene and

beyond. Oxford, UK: Solaris.

Whitehead, M. (2014). Environmental transformations: A geography of the

Anthropocene. London, England: Routledge.

13

Learning Communities Research and Practice, Vol. 7 [], Iss. 1, Art. 5

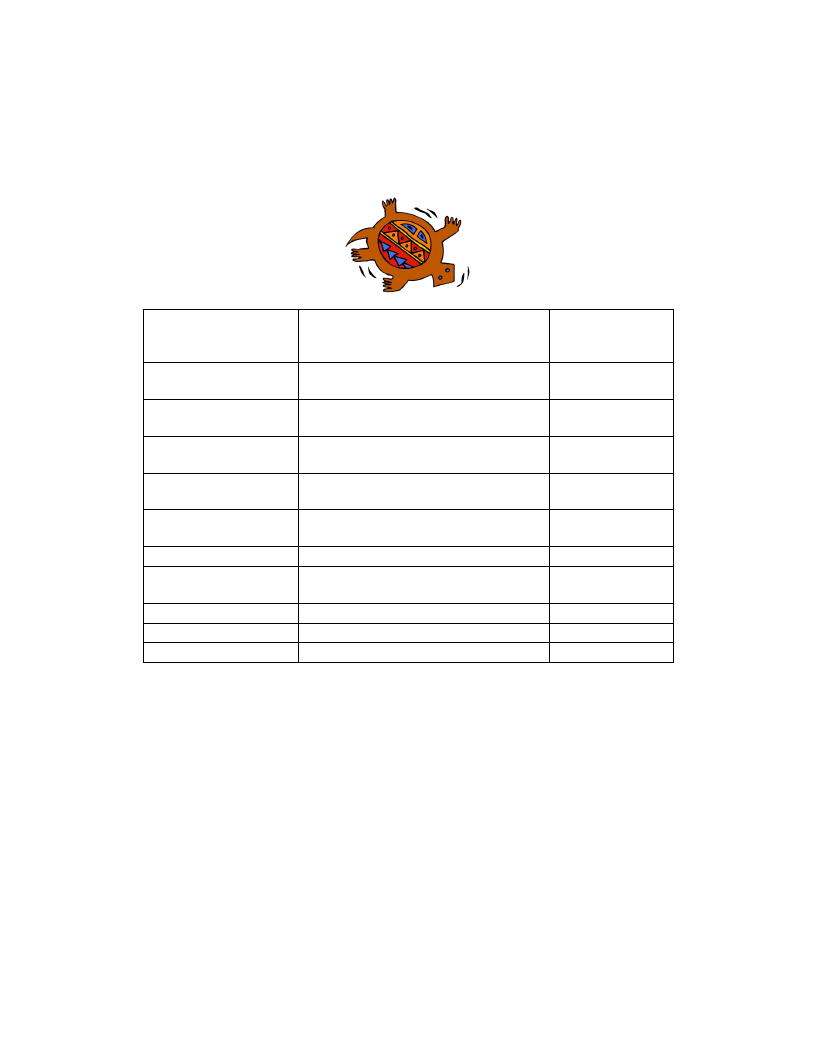

Appendix 1

Climate Change Stress Index

Stress factor/impact

Breakdown in

infrastructure

Breakdown in

government

Breakdown in

civilization/social order

Climate and weather

imbalance/disorder

Ecosystem imbalance-

flora and fauna

Resource scarcity

Regression (social,

technological, etc.)

Illness/disease

Adaptation

Mitigation

Example from the text -- record a brief

quote, with page #, and bullet point

observation(s).

Contributor (put

your name here)

https://washingtoncenter.evergreen.edu/lcrpjournal/vol7/iss1/5

14

Mino et al.: Interdisciplinary Indexing

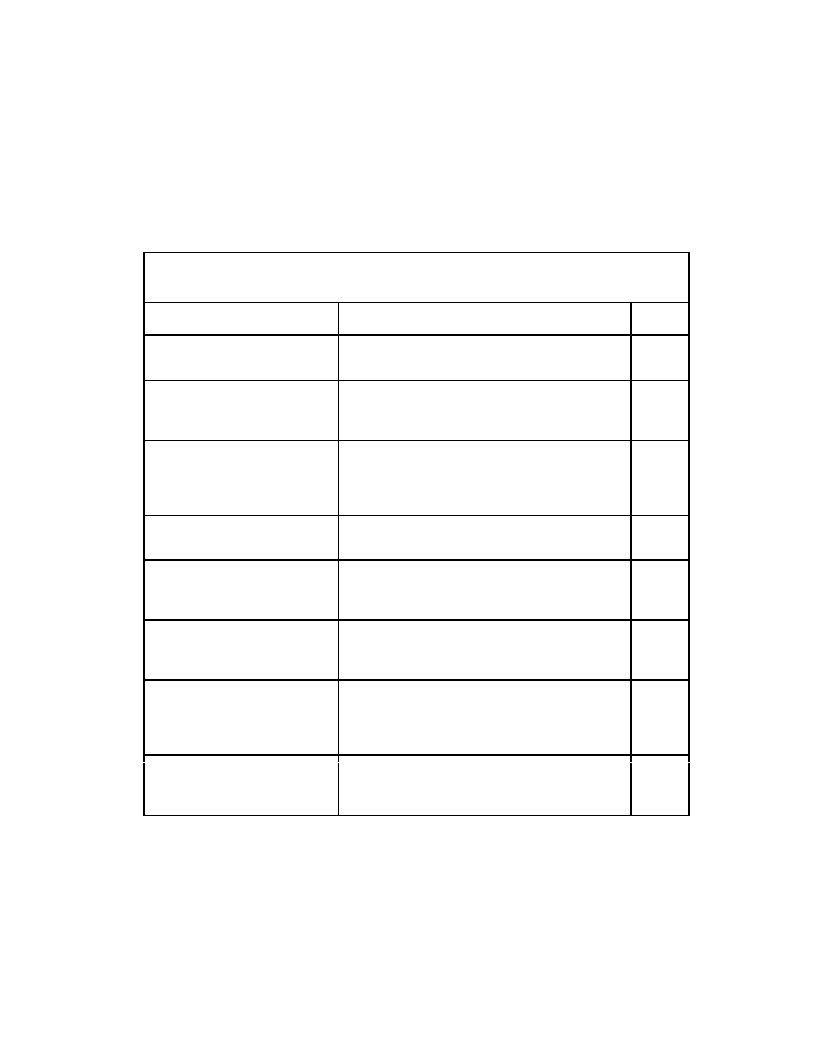

Appendix 2

Ecopsychology Index Applied to Environmental Literature

For each of the book titles below, select a quotation from the text and explain how

one or more of the eight Ecopsychology principles listed applies to that text.

Not Wanted on the Voyage

Timothy Findley

Ecopsychology Principle

Quotation (page number)

The core of the mind is the

ecological unconscious.

The contents of the ecological

unconscious represent the living

record of evolution.

The goal of ecopsychology is to

awaken the inherent sense of

environmental reciprocity that lies

within the ecological unconscious.

The crucial stage of development is

the life of the child.

The ecological ego matures toward a

sense of ethical responsibility with

the planet.

Ecopsychology needs to re-evaluate

certain “masculine” character traits

that lead us to dominate nature.

Whatever contributes to small scale

social forms and personal

empowerment nourish the ecological

ego.

There is a synergistic interplay

between planetary and personal well-

being.

Initials

15