Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Deep Ecology as a framework for student eco-philosophical thinking

William Smith

RMIT University, Australia

william.smith@rmit.edu.au

Annette Gough

RMIT University, Australia

annette.gough@rmit.edu.au

Abstract

Deep ecology is an ecological philosophy that promotes an ecocentric lifestyle to

remedy the problems of depleting resources and planetary degradation. An integral

part of this ecosophy is the process of forming a metaphysical connection to the

earth, referred to as self-realisation; an unfolding of the self out into nature to attain a

transcendental, non-egoic state. Findings from our research indicate that secondary

school students in environment clubs align with the principles of deep ecology, and

show a capacity to become student eco-philosophers, and they report empathy for

becoming ecocentric beings. This study explores the capacity for students to engage

in environmental philosophy.

Key words

ecosophy, deep ecology, self-realisation, ecological self, secondary schooling

Introduction

The idea that children can be philosophers is not new (Haynes 2003; Haynes, 2014),

however, there has been little if any research on ecocentric philosophies in schools,

and on how secondary school students view themselves using the deep ecology lens.

As a result of our research we propose the idea of student as eco-philosopher, based on

the existing network of philosophy in schools (Sapere 2014). The significance of this

study is in its generation of new theoretical models for eco-philosophical thinking

amongst secondary students.

There is growing evidence that philosophy is an important component of school

education, with successful programs being implemented throughout the United

Kingdom (Bartley & Worley 2012), where primary school children as young as eight

38

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

years are successfully involved in classroom philosophy (Bartley & Worley 2011),

and in Australian schools (Federation of Australasian Philosophy in Schools

Association 2014; Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority 2014). There is

also an active program in the United States for teaching philosophy to children

(Teaching Children Philosophy 2014) and a primary school program in ethics in

Australia (Primary Ethics 2014). Philosophy has become popular in England where it

is claimed that it promotes abstract thinking, the art of discussion, and expands

students’ vocabulary (Brett 2003). Others have called it the holy grail of education

because it creates active, creative and democratic thinking, at the same time as

increasing a sense of self-worth in students (Cohen & Naylor 2008).

In this paper we discuss the relevance of ecocentrism to students’ lives and propose

that students can realise their ecological self based on the deep ecology philosophy of

Naess (1973). Our investigation of the ecological self derives from self-realisation

(Naess 1995), a central metaphysical process for deep ecologists that we examine in

the context of concepts of the self. The purpose of our study was to investigate

student beliefs about ecocentrism and anthropocentrism, and the approach taken

was grounded in the ecologism of Green political thought (Dobson 2007). Whereas

environmentalism takes a managerial approach to environmental problems, ecologism

seeks the existential solution of a radical change to human existence in social and

political life, and has the core idea of reframing the relationship humans have to

non-human nature to allow for a more sustainable and meaningful life. Our study

also followed the critical social research tradition (Harvey 1990) by investigating the

contemporary social order of society, an essential feature of the deep ecology

platform (Rothenberg 1995). The theoretical framework was underpinned by a

critical-dialectical perspective that attempted to uncover social forces that influenced

student thinking about their place in the biosphere (Harvey 1990).

Deep Ecology

The deep ecology movement developed in the early 1970s in response to concerns

about the lack of connectedness, reciprocity and simplicity in the shallow

environmental worldview dominant in Western society. The founder of deep

ecology, Arne Naess (1973), outlined its main principles of connectedness to nature,

biospherical egalitarianism, wilderness preservation, population management,

biodiversity, and reduction of resource use (1973). In the same article Naess argued

that shallow ecology was a narrow (anthropocentric) science that mainly addressed

pollution or other environmental problems that threatened the affluent in society,

39

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

whereas lifestyles that protected the earth were deep ecology (ecocentrism). Another

more metaphysical process in deep ecology, described by Naess as ‘self-realization’, is

the deeper questioning of the relationship between the Self (the ecological self) and

nature (Fox 1990b). Sometimes this is referred to as an unfolding of the Self outwards

into the environment (Fox 1990a), and it means moving towards a oneness or

meaningful life by recognising the intrinsic value of all biological systems (Mathews

1991). Naess did not see this as a moral position but rather saw the connectedness as

deriving from a love and respect of all life and of all nature (Fox 1990b), including

the inanimate part of ecosystems such as mountains and rivers. For Naess, self-

realisation was moving from the narrow ego to ‘as expansive a sense of self as

possible’ (Fox 1990b, p. 106). Naess was also influenced by Rachel Carson’s Silent

spring (1962) to have a deep humility towards the earth, and cites her as saying that

humanity was a ‘drop of the stream of life’ (Naess & Rothenberg 1989, p. 165).

Naess was not the only scholar to devise an ecosophy; Felix Guattari was also a key

figure in the study of ecosophy (Guattari 2000) and his approach of the three ecologies

is described as an ecological philosophy that ‘engages with the material, social, and

ideological “registers” of life’ (Greenhalgh-Spencer 2014, p. 324) and is presented as

a lens to ‘illuminate pedagogical practice’. In our analysis of Guattari’s pedagogical

usefulness, it does fulfill a role in moving towards valuing the non-human world,

but his emphasis on social problems differs from what we see as the more important

aspects of deep ecology relating to the metaphysics of the Self. Naess grounded his

philosophy in the work of Spinoza (Naess 2005b) and his concept of self-realisation

was influenced almost entirely by Gandhi (Naess 1988). Spinoza’s monism and

Gandhi’s maturation of the self are key ingredients in the deep ecology platform that

provide unique models for embracing ecological philosophy. Deep ecology

promotes the complex thinking required for environmental reform and it does this

by promoting an ecological consciousness to counter dominant worldviews that

threaten the planet (Devall & Sessions 2007).

It is important to establish some pedagogical terrain for deep ecology within the

philosophy of education landscape, and the principal foundation is Dewey’s

dissertation on education and culture (Garrison, Neubert & Reich 2012). The roots of

environmental education can be traced to the liberal-progressive philosophy of

Dewey (Gough & Gough 2010). According to Garrison et al. (2012), Dewey saw

humans as part of nature:

Since his early acquaintance with Hegel, Dewey had realized that

nature and culture are not opposite but relational to each other. He

40

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

was convinced that humans as cultural beings are a part of nature.

They act within nature, with it, and partly also against it at the same

time. (p. 1)

This view accords with the monism of deep ecology (Naess & Sessions 1995). Dewey

also held the view that the individual (or self) is co-evolving with the environment

and he viewed the environment as the total of all that is experienced by the self.

Dewey contributed insight into the unfolding of the self by stating that education was

an ‘unfolding of latent powers towards a definite goal’ (Dewey 2012, p. 79). This is

seen as a drawing out of the student and a developing of the mind, which is not

dissimilar to Naess’ deeper questioning towards a gestalt state of existence (Naess

2005a). From this perspective, this paper proposes an additional approach to the

philosophy of education, one that sees deep ecology as an ecosophy for students

willing to focus their minds on metacognition rather than on discipline-based

thinking.

We recognise that there is important work on moral education and critical thinking

(Lipman 1995), and more recent evidence that the quality and complexity of student

responses increases when teachers ask shorter, higher-order questions (Topping &

Trickey 2007), particularly when there is a shift from teacher talk to student talk.

There is also an array of thinking skills programs, of which Lipman’s Philosophy for

Children (P4C) is possibly the best known (Trickey & Topping 2004), and

collectively they harness skills that are consistent with the deep ecology principles

(Naess 1973) and the deep ecology platform (Naess & Sessions 1995). Lipman’s

pedagogical dimension to philosophy of education, the community of philosophical

inquiry (Kennedy 2012), lends itself to a similar normative discourse that can be

found in deep ecology (Drengson & Devall 2010). Lipman’s dialogical speech

community, we believe, would work well as a classroom exercise for complex

environmental issues that might be emotive and challenging for students to

embrace. Our view is that it is necessary for schools to prepare students to be good

earth citizens in the face of environmental criticism (Dobson & Bell 2006).

There is a further dimension to deep ecology that requires recognition, and this

relates to the idea of intrinsic value (Fox 1990b). Defining an intrinsic value for non-

human nature is one of the central problems of environmental ethics (Callicott 1995),

largely because there is an assumption that if only sentient beings can perceive

nature (Rolston 1994), then what value does nature have when it is not experienced

by humans? Participants in the research study were asked about the value of nature

but the full analysis of the topic is beyond the scope of this paper.

41

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Research study and methodology

The focus of this study is the responses from nine students and three teachers

(including the sustainability coordinator ‘Wolf’1) who were interviewed at a mixed-

gender metropolitan secondary college (‘Bunjil’2) in the eastern suburbs of

Melbourne. The school was located within the metropolitan region of Melbourne

and was unremarkable in the sense that it was not in a disadvantaged demographic

region, nor in a prestigious location, and was a government school. We approached

the Victorian Association of Environmental Education for member schools that

might be interested in a study of deep ecology, and a few schools with strong

sustainability initiatives were short-listed. From this list we negotiated cooperation

from the school Bunjil (some principals we approached did not wish to be part of the

study). Students were drawn from the school’s environmental club; i.e. enviroclub

(with one exception), largely because they were encouraged to do so by the

sustainability coordinator, and with the permission of the principal and

governmental education department authorities. All of the available enviroclub

students participated in the study. The enviroclub is only one of a number of

voluntary extracurricular activities (e.g. music, student representative council, sport)

competing for student membership. Use of stratified sampling was not possible due

to the difficulties in finding a host school, largely because schools receive many

requests to conduct research. Semi-structured interview questions are one of the

tools of population survey and they can be designed to give either narrow responses

or almost completely unstructured responses (Nayar 2014). We aligned more with

the latter view, so the semi-structured interview questions were tailor-written for

enviroclub students and sustainability coordinators. We used semi-structured

interview questions as the basis for flexible interviews allowing for rich responses

that enabled us to follow interesting lines of thought (Appendices I and II). We

encouraged respondents to elaborate on answers and clarify their thoughts

whenever fruitful lines of inquiry emerged during the interview. What is clear from

our teacher interviews is that the sustainability coordinators had a clear

predisposition for the role and embraced the duties with some passion and

commitment. We recorded responses from the students and teachers about the

relative value of humans versus the non-human world by asking them if the earth’s

limited resources should be more equitably shared between humans and the non-

human and inanimate parts of ecosystems. The research question we addressed

looked at evidence for eco-philosophical thinking consistent with the deep ecology

1 Respondents were de-identified by name and gender using the names of stars in the night sky.

2 We used the name of an Indigenous supernatural deity to de-identify the school.

42

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

philosophy of biospherical egalitarianism (monism), self-realisation, ecological

wisdom3, biodiversity and anti-neophilia. The respondents were also asked

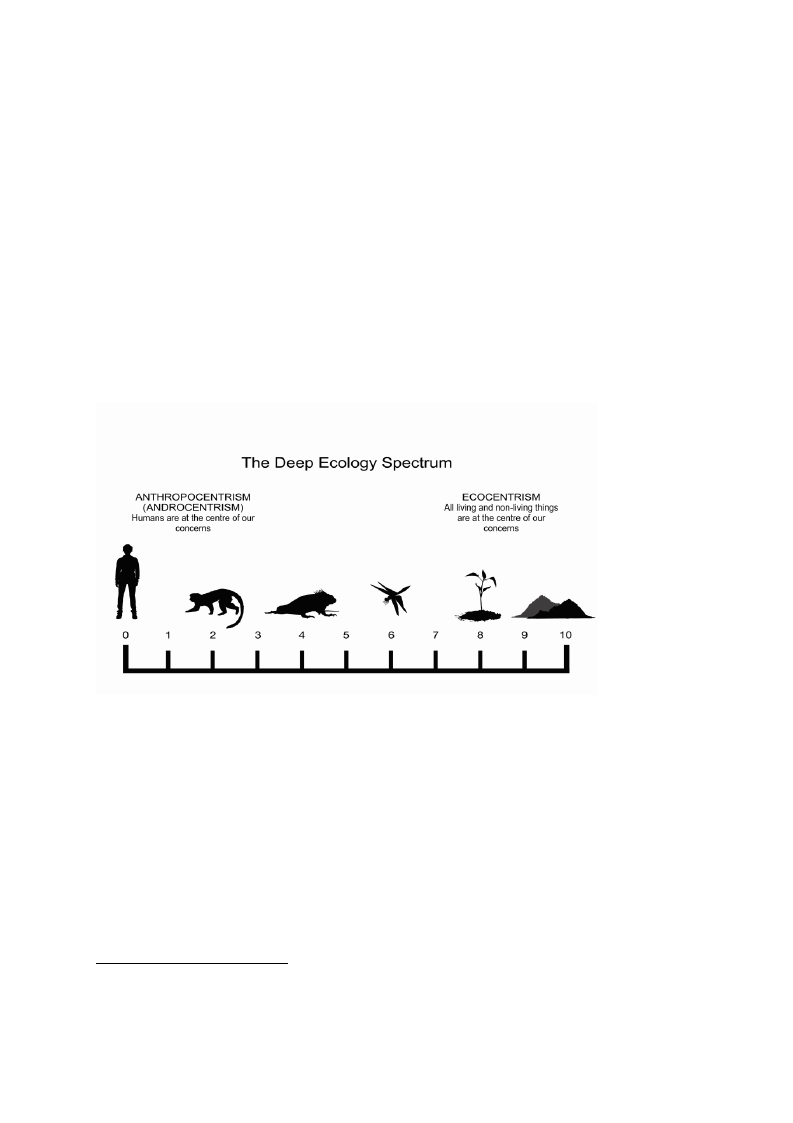

questions about their orientation towards Naess’ binary of anthropocentrism versus

ecocentrism. However, we devised a modified version modeled on the

electromagnetic spectrum, to allow for a range of answers rather than the simple

binary responses. We refer to this research device as The Deep Ecology Spectrum

(Figure 1). We created this spectrum to give the respondents the option of aligning

with a value somewhere along the spectrum. This value represented the degree to

which the student thought that humans should sacrifice their use of natural

resources for the greater good of all ecosystems. Students were also asked questions

about Indigenous land practices and whether the land was managed in a more

sustainable and holistic way compared with European settlers.

Figure 1: The Deep Ecology spectrum

(Copyright HR Smith 2014. Reprinted with permission)

The interview data for the students were transcribed, coded and analysed using

grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss 1967), modified to facilitate rich, nuanced

analysis of the responses (Boeije 2010), then reconstituted into an ontological model

(see Figure 2).

3 Naess describes ecological wisdom as the ‘deep exploration of our whole lives and context in pursuit

of living wisely’ and as ‘the essence of Socratic inquiry to know ourselves’ (Drengson & Devall

2010, p. 19).

43

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Findings

Our research findings to date indicate that the establishment of sustainability clubs

and collectives in schools, together with other environmentally-related activities in

school and at home, has led to the emergence of a generation of school students that

are well informed about key environmental problems. For example, if students had

attended a primary school with school-wide sustainability practices, they were

predisposed to becoming enviroclub members at Bunjil, even if other clubs were

available. Our data also shows that these successes are due largely to the teachers

appointed as sustainability coordinators in schools, who drive student immersion

into a sustainable culture where the school identifies itself as having a sustainability

focus. This identity is promoted throughout the school community by the principal

and ‘Wolf’, and beyond into the wider community via the school website and the

media. The students in environment clubs in our research are influenced positively

by the sustainability coordinators to have robust views about how to live and how to

protect the environment. This paper focuses on the potential of developing a deep

ecology philosophy within these students, because they express a level of awareness

of environmental issues that separates them from students who choose to stay

outside of the sustainability loop (Department of the Environment Water Heritage

and the Arts 2010; Szabo & Hedl 2011).

Some students provided evidence of metaphysical responses to the interview

questions. The following example was from a Year 9 student:

00:18:46 ‘Barnard’: Yeah I definitely agree with putting the earth first. It’s

such a beautiful and unique ecosystem our universe and our world that it

should be there for I suppose people of the future to observe so they can admire

the beauty of everything. So conserving resources to protect the environment

I definitely agree is an important thing. But there is of course the problem of

the efficiency of the resources that are like harmful to the environment.

When asked about what the future holds for us humans, Year 12 student ‘Naldisu’

responded:

00:10:41: I think I have to be optimistic because if you keep thinking that the

world’s going to die, and the future generations won’t have anything left

that’s not the nicest way to think. Because if you come in with the thought

that we’re all doomed then you’re not going to work as hard towards fixing

it.

44

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

The crucial task for eco-philosophers interested in embedding deep ecology in

schooling is to prevent it from being seen as a bolted-on imposition on the core

curriculum. Our findings indicate that environment club students in schools tend to

align with the ecocentric end of the deep ecology spectrum. Using the Deep Ecology

Spectrum, where ‘zero’ equates to anthropocentrism and ‘ten’ to ecocentrism,

students interviewed at Bunjil, scored 6.5. This represents a significant skew towards

ecocentrism, but at the same time it indicates that the respondents cannot fully let go

of human needs and wants (which could be construed as a social versus ecocentric

orientation). This is not the same as Guattari’s social ecosophy that consists of

‘developing specific practices that will modify and reinvent the ways in which we

live as couples or in the family’ (2000, p. 34). The responses from students indicate

that humans are in a sense on a journey moving from an anthropocentric past

towards an ecocentric future. This needs to be explored further to identify the

cognitive processes behind the views expressed.

Responses from teachers at Bunjil indicate that they find it difficult to embrace

sustainability as a cross-curriculum priority, unless ecology is already part of the

core curriculum for their discipline. This was described by Delphinus, the

curriculum coordinator at Bunjil, as due to the larger task of implementing the

Australian Curriculum across the entire school. This process commenced in 2013 at

Bunjil and, at the time of interview in 2014, many teachers were engaged in the

transition from old teaching materials to new documentation. There was a clear

sense that the curriculum was crowded enough without the cross-curriculum

priorities, even if they are part of the Melbourne Declaration that set the foundations

for the Australian Curriculum (MCEETYA 2008). Despite this problem of

embedding deep ecology in schools, the extra-curricular sustainability projects

(solar, water recycling, habitat restoration, energy saving, wetlands, urban forest,

frogbog) engender traits in students that are reflexive and at times metaphysical.

These characteristics are age-dependant and apparently relate to the transition from

primary school (Grade Six) into secondary school (Year Seven). The sustainability

coordinator Wolf reported that students from feeder primary schools with existing

environmental programs often find it difficult to adjust to the secondary school

timetable (and hence different teachers and rooms), but they also have more options

for extracurricular activity (as pointed out above).

The enviroclub students reported that they contemplate the nature of their own

existence, have an acute awareness of their sense of being within the social milieu of

the school, and can transcend personal boundaries to other ecosystems and other

45

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

creatures. They have a feeling of interconnectedness that aligns well with deep

ecology philosophy. Both Wolf and the enviroclub students identified strongly with

the club projects and were proud of the many environmental awards won by

members of the school community (including Wolf, the principal, and the school at

state, national and international levels). This could be construed as elitism but the

responses are more aligned to an ecological wisdom as described earlier. It clearly

gave students a wider identification with creatures all around the earth and a more

highly developed sense of self, consistent with an ecological self.

The teachers and students also hold the view that traditional landowners had a more

spiritual and connected existence to land compared with colonising peoples, and

that their collective knowledge is a valuable epistemological resource that all

humans can draw upon if we are to lead an ecocentric existence.

Discussion – A framework for eco-philosophical thinking

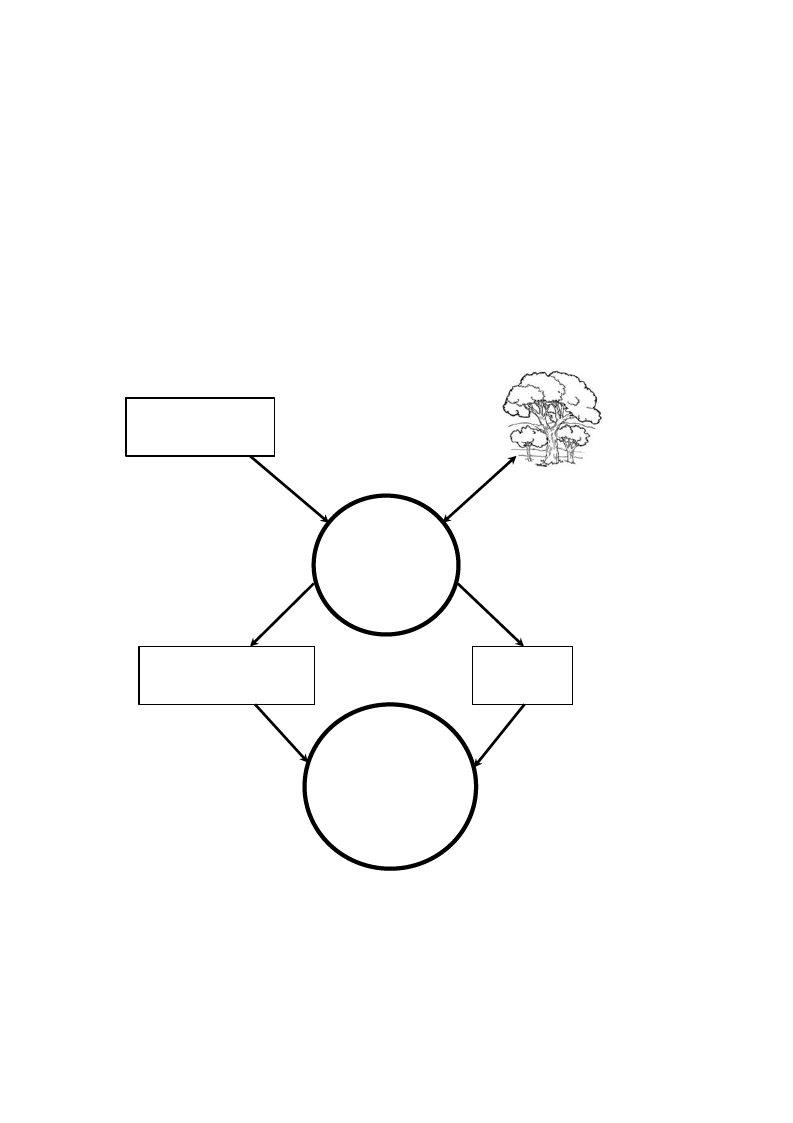

We have developed an ontological model to explain the student social milieu and

how the students transform into eco-philosophical entities (Figure 2). The model sees

all of the entities (beings) in the students’ lives as contributing to a social influence or

vector (force acting in a direction) that changes their existence and thoughts. The

social vector of influence might be interpreted as the net effect of factors that might

compete against enviroclub (e.g. student representative council, Year 12 exams)

versus those factors that might enhance membership of enviroclub (early years

exposure to sustainability at primary school). The sustainability coordinator, Wolf, is

a central figure who walks the talk, and is universally seen as an exemplar by the

students, thus contributing to the social vector of influence. There might be some

tensions from staff outside the sustainability milieu because they perceive it as

impinging on the core business of classroom teaching, and this aspect needs further

investigation, but this does not produce a negative vector of influence. Bunjil

provides significant support (both financial and time allocation) to Wolf’s position

and there is strong support from parents and the school council for the sustainability

program. In the two-way flux where the students engage in self-realisation, we

propose this metaphysical ‘oscillation’ as a thought exercise where the students

allow nature to come into the fold of their consciousness, and then they in turn

become expansive throughout nature by dissolving any boundaries between the self

and the non-self. Naess’ description of self-realisation is built on Gandhi’s rejection

of the narrow ego, attainment of a ‘supreme or universal Self’ (1988, p. 25), and

through the wider identification with nature (1988). Naess elaborates (1988, p. 20);

46

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

‘The joy and meaning of life is enhanced through increased self-realisation, through

the fulfilment of each being’s potential’. Our model in Figure 2 proceeds on to a

social psychological model of the student exercising agency over their own existence

on the one hand (De Lamater, Myers & Collett 2015), and embracing the

epistemological and spiritual approaches of Indigenous peoples to the earth on the

other hand. Once the student abandons the narrow ego and moves from the social to

the ecological self, there is an ultimate version of the self that is indistinguishable

from the non-human ecosystem.

Eco-philosophical model for student as eco-philosopher

School environment

Club projects

social vector

of influence

personal vector of

agency

Forming ecocentric beliefs

and self-agency

transcending the egoic social

self to create the ecological self

Enviroclub

student

dynamic of self-

realisation with nature

the first ecologists

‘Student as

eco-

philosopher’

First Nations

beliefs

spiritual

connection to

the earth

Figure 2: The ontological basis for Student as Eco-philosopher

The personal vector of agency we propose is the actualisation of Naess’ self-

realisation to achieve a non-egoic state, and this is effectively the monism that Naess

(2005b) adopted from Spinoza, where the delineation between self and non-self no

47

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

longer exists. Interconnectedness with the environment underpins the development

of an ecological self (Mathews 1991), which Naess interprets as occurring when

‘things strive to increase their level of being in themselves, to increase their power, to

increase their level of freedom’ (Drengson & Devall 2010, p. 274). The vector along

the line of the first ecologists has its origins in the view by some anthropologists that

‘we open our minds and our bodies to other people’s epistemologies’ (Rose 2007, p.

88), and that we need to ‘question our modern sense of the real’, to overcome the

‘pervasive anthropocentrism in modernity’ (Apffel-Marglin 2011, p. 13). Turning to

other cultures is inherent in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cross-

curriculum priority of the Australian Curriculum, but how the spiritual connection

to the earth is addressed is open to interpretation by teachers. Most of the world’s

peoples live in non-cosmopolitan, non-modern places and rely upon ritual and

traditional knowledge to lead rich and rewarding lives (Apffel-Marglin 2011). It

made sense to include this topic in the semi-structured interview questions and our

data show that student and teacher beliefs support traditional knowledge being

integral to the concept of student as eco-philosopher. Our data show that

respondents believe that Australian aboriginal peoples are closely connected to the

land, and that this relationship to country led to more sustainable land management

practices compared to European settlement.

The study reveals that secondary students in an environment club have an

understanding of the various, complex factors at play in our world that are affecting

both the natural environment and their own biographical trajectories. They are

aware of the social norms for their age group and how these norms influence

lifestyle and consumer behavior that might negatively impact on the limited

resources of the earth. They have a distinct awareness of their unique position

within the school community, a state of mind that is generally altruistic and ego free.

This was not a result that we pre-empted in our interview questions nor self-

reported by the students. The observation was derived from the field notes taken in

addition to the audio transcripts. Environmental disasters on the opposite side of the

planet adversely affected the students and this was driven by a concern for wild

animals. The students were able to reflect upon their place within their own families,

as well as within the school community, and they used this to create their ecological

selves as well as robust eco-philosophical views. We postulate that this ontological

analysis of the data is a central feature of student lives and that this is important to

the concept of student as eco-philosopher.

48

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Conclusion

In this paper we developed a theoretical model for the student as eco-philosopher,

based on the findings from our research with students and teachers in a Victorian

state secondary school. Our research indicates that students in secondary schools can

embrace philosophy at abstract levels, and that this proposition is supported by

responses from students in our cohort school. We also show that, whilst Naess’s self-

realisation is a metaphysical experience that not all scholars would agree can easily

be defined, the notion of self and the abstract sense of being are concepts that young

people can and do embrace. We conclude from our work that these students reflect

upon their existence within the ecological world and generate an environmental

philosophy that is robust, personal and well developed. In the process of developing

an ecological self, the students demonstrate attributes towards becoming the student

as eco-philosopher. Schools should be encouraged to establish environment clubs

and provide opportunities for students to engage in self-realisation that enables

them to develop their ecological selves.

References

Apffel-Marglin, F (2011) Subversive spiritualities. How rituals enact the world. Oxford

University Press, New York, NY.

Bartley, G & Worley, P (2011) Primary school philosophy. Philosophy Now Radio Show

#13. Resonance FM, London, 26 October.

Bartley, G & Worley, P (2012) Philosophy in education with Peter Worley, Michael

Hand and Stephen Boulter. Philosophy Now Radio Show #30. Resonance FM,

London, 13 March.

Boeije, H (2010) Analysis in qualitative research. SAGE, Los Angeles, CA.

Brett, M (2003) Philosophy 4 Skool. The Philosopher, 91(2). http://www.the-

philosopher.co.uk/philinschool.htm

Callicott, JB (1995) Intrinsic value in nature: A metaethical analysis. The Electronic

Journal of Analytic Philosophy, 3(Spring).

http://ejap.louisiana.edu/EJAP/1995.spring/callicott.abs.html

Carson, RL (1962) Silent spring. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA.

49

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Cohen, M & Naylor, L (2008) Philosophy in schools. The Philosopher, 96(1).

http://www.the-philosopher.co.uk/p4cgallions.htm

De Lamater, JD, Myers, DJ & Collett, JL (2015) Social psychology. 8th edn, Westview

Press, Boulder, CO.

Department of the Environment Water Heritage and the Arts (2010) Evaluation of

operational effectiveness of the Australian sustainable schools initiative. Final report.

Department of the Environment Water Heritage and the Arts, Sydney.

Devall, B & Sessions, GS (2007) Deep ecology: Living as if nature mattered. Gibbs Smith,

Layton, UT.

Dewey, J (2012) Democracy and education. Start Publishing, New York, NY.

Dobson, A (2007) Green political thought. 4th edn, Routledge, London.

Dobson, A & Bell, D (2006) Introduction. In A Dobson & D Bell (eds), Environmental

citizenship. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 1-18.

Drengson, A & Devall, B (eds) (2010) The ecology of wisdom. Writings by Arne Naess.

Counterpoint, Berkeley, CA.

Federation of Australasian Philosophy in Schools Association (2014) FAPSA Home

page. Viewed 23 August 2014. http://fapsa.org.au

Fox, W (1990a) On the interpretation of Naess’s central term “self-realization”. The

Trumpeter Journal of Ecosophy, 7(2), pp. 98-101.

Fox, W (1990b) Toward a transpersonal ecology: Developing new foundations for

environmentalism. Shambala, Boston, MA.

Garrison, J, Neubert, S & Reich, K (2012) John Dewey's philosophy of education. An

introduction and recontextualization for our times. Palgrave MacMillan, New York,

NY.

Glaser, BG & Strauss, AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for

qualitative research. Aldine, Chicago, IL.

Gough, A & Gough, N (2010) Environmental education. In C Kridel (ed) The

encyclopedia of curriculum studies. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 339-343.

50

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Greenhalgh-Spencer, H (2014) Guattari’s ecosophy and implications for pedagogy.

Journal of Philosophy of Education, 48(2), pp. 323-338.

Guattari, F (2000) The three ecologies. (trans I Pindar & P Sutton), The Athelone

Press, London, UK.

Harvey, L (1990) Critical social research. Uwin Hyman, London, UK.

Haynes, F (2014) Teaching children to think for themselves: From questioning to

dialogue. Journal of Philosophy in Schools, 1(1), pp. 131-146.

Haynes, J (2003) Children as philosophers: Learning through enquiry and dialogue in the

primary classroom. Routledge, London.

Kennedy, D (2012) Lipman, Dewey, and the community of philosophical inquiry.

Education and Culture, 28(2), pp. 36-53.

Lipman, M (1995) Moral education higher-order thinking and philosophy for

children. Early Child Development and Care, 107(1), pp. 61-70.

Mathews, F (1991) The ecological self. Routledge, London.

Ministerial Council on Education Employment Training and Youth Affairs (2008)

Melbourne Declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Carlton South,

Victoria.

Naess, A (1973) The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement. A

summary. Inquiry, 16(1), pp. 95-100.

Naess, A (1988) Self realization: An ecological approach to being in the world. In J

Seed, J Macy, P Fleming & A Naess (eds), Thinking like a mountain: Towards a

council of all beings. New Society Publishers, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 19-30.

Naess, A (1995) Self-realization. An ecological approach to being in the world. In G

Sessions (ed), Deep ecology for the 21st century. Readings on the philosophy and

practice of the new environmentalism. Shambala, Boston, MA, pp. 225-239.

Naess, A (2005a) Gestalt thinking and Buddhism. In HG Glasser & A Drengson

(eds), The selected works of Arne Naess, vol. 8. Springer Netherlands, pp. 1839-

1849.

51

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Naess, A (2005b) Spinoza and attitudes toward nature. In HG Glasser & A Drengson

(eds), The selected works of Arne Naess, vol. 10. Springer, Netherlands, pp. 2647-

2661.

Naess, A & Rothenberg, D (1989) Ecology, community and lifestyle. Outline of ecosophy.

New York, NY.

Naess, A & Sessions, G (1995) Platform principles of the deep ecology movement. In

A Drengson & Y Inoue (eds), The deep ecology movement. An introductory

anthology. North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, CA, pp. 49-53.

Nayar, PK (2014) Posthumanism. Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

Primary Ethics (2014) Primary ethics: Just think about it.

http://www.primaryethics.com.au/

Rolston, H (1994) Value in nature and the nature of value. In R Attfield & A Belsey

(eds). Philosophy and the natural environment, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, pp. 13-20.

Rose, DB (2007) Recursive epistemologies and an ethics of attention. In J-GA Goulet

& BG Miller (eds), Extraordinary anthropology. University of Nebraska Press,

Lincoln, NE, pp. 88-102.

Rothenberg, D (1995) A platform of deep ecology. In A Drengson & Y Inoue (eds),

The deep ecology movement: An introductory anthology. North Atlantic Books,

Berkeley, CA, pp. 155-166.

Sapere (2014) Sapere. Philosophy for children, colleges, communities. Viewed 12

November 2014. http://www.sapere.org.uk

Szabo, P & Hedl, R (2011) Advancing the integration of history and ecology for

conservation. Conservation Biology, 25(4), pp. 680-687.

Teaching Children Philosophy (2014) Main page. Viewed 6 August 2104.

http://www.teachingchildrenphilosophy.org/wiki/Main_Page

Topping, KJ & Trickey, S (2007) Impact of philosophical enquiry on school students’

interactive behaviour. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2(2), pp. 73-84.

52

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Trickey, S & Topping, KJ (2004) ‘Philosophy for children’: A systematic review.

Research Papers in Education, 19(3), pp. 365-380.

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (2014) Philosophy. Viewed 23

August 2014..

http://www.vcaa.vic.edu.au/Pages/vce/studies/philosophy/philosophyindex.as

px

53

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Appendix I: Student Interview

Deep Ecology and Secondary Schooling project

List of questions for students

Semi-structured interview

Q1. Can you tell me what motivates you to be involved in sustainability and

perhaps a little bit about yourself?

Q2. How does it make you feel when you work on an environmental problem and

end up either solving or reducing the problem?

Q3. Does working towards a solution make you think differently, more carefully

about what impact you and the people around you have on the planet?

Q4. Thinking overall, about teachers and other students, if some don’t really care

that much about the environment, how do you think and feel about that?

Q5. Some people try to solve environmental problems just so that we can have

more resources for humans. What do you think?

Q6. Some people called Deep Ecologists think we should not keep using more and

more resources, and should put the Earth first. What do you think?

Q7. Does being involved in sustainability change the way you think in general? Are

you more inclined to be critical if you think an action is harmful to the Earth?

Q8 Some researchers believe that Aboriginal Peoples and Native Americans had a

more spiritual and stronger relationship to the land and they took better care of

the land. Do you agree or disagree? Can we learn from this?

Q9. Do you agree with the idea that First Nations Peoples (Aboriginal) can be

described as the first ecologists?

Q10. Are many of the teachers at the school as keen on sustainability as Mr.

‘Aldebaran’?

Q11. You will be shown a picture of the DES (deep ecology spectrum) scale. Can you

tell me where on this line you might situate yourself with 1 = anthropocentric

(humans first) and 10 = ecocentric (earth first)? THIS DIAGRAM WILL BE

EXPLAINED TO YOU AT INTERVIEW.

54

Deep Ecology

Journal of Philosophy in Schools 2(1)

Appendix II: Teacher Interview

Deep Ecology and Secondary Schooling project

List of questions for teachers

Semi-structured interview

Q1. Can you tell me how you became involved in sustainability education and a

little bit about your recent teaching in the area?

Q2. How does it make you feel when you and your students work on an

environmental problem and contribute to reducing the problem? Do you feel

more connected to the Earth?

Q3. Do you think that students acquire a kind of ecological wisdom, perhaps a

more robust personal ecological philosophy by studying sustainability?

Q4. When you think of the earth’s ecosystems as consisting of physical elements,

human and non-human elements, do any one of these deserve priority? How

does this affect your approach to sustainability teaching?

Q5. Do you think that science has the answer to all of our sustainability problems?

Is there another way of tackling planetary health for future generations?

Q6. Some people try to solve environmental problems just so that we can have

more resources for humans. What do you think about this approach? Explain.

Q7. Some people called Deep Ecologists think we should not keep using more and

more resources, and should put the earth first. What do you think?

Q8. Some researchers believe that Aboriginal Peoples and Native Americans had a

more spiritual and stronger relationship to the land and they took better care of

the land. What do you think? Can we learn from this?

Q9. Do you agree with the idea that First Nations Peoples (Aboriginal) can be

described as the first ecologists?

Q10. In teaching children about Aboriginal identity with country as described in the

curriculum, how do you best convey this relationship to students and do they

truly understand what it means?

Q11. When you read the AusVELS content descriptors, how do you go about giving

them meaning (i.e. translate them into teaching practices)?

55