Forest Science and Technology

ISSN: 2158-0103 (Print) 2158-0715 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tfst20

The influence of indirect nature experience on

human system

Jin Young Jeon, Poung Sik Yeon & Won Sop Shin

To cite this article: Jin Young Jeon, Poung Sik Yeon & Won Sop Shin (2018) The influence of

indirect nature experience on human system, Forest Science and Technology, 14:1, 29-32, DOI:

10.1080/21580103.2017.1420701

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2017.1420701

© 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa

UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis

Group.

Published online: 09 Jan 2018.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 3073

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tfst20

FOREST SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, 2018

E–ISSN 2158-0715, VOL. 14, NO. 1, 29–32

https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2017.1420701

The influence of indirect nature experience on human system

Jin Young Jeona, Poung Sik Yeonb and Won Sop Shina

aGraduate Department of Forest Therapy, Chungbuk National University, 1 Chungdae-ro, Cheongju 28644, Korea; bNational Center for Forest

Therapy, 209 Therapy-ro, Bonghyun-myeon, Yeongju, Kyungbuk 36043, Korea

ABSTRACT

A growing number of studies have shown that contact with nature contributes enhancing positive

psycho-physiological effects. This study experimentally compared the effects of direct and indirect

contact with nature on psychological and physiological affect, respectively. Thirty university students

participated in this experiment. The results of this study indicated that indirect nature experience also

provided positive psychological and physiological effects, except for parasympathetic nerve activity.

The results of the present study would support the effectiveness of virtual nature for people who

cannot easily access real nature in order to improve psychological benefits.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 20 November 2017

Accepted 20 December 2017

KEYWORDS

Contact with nature; psycho-

physiological effects; virtual

nature; forest therapy; health

benefits

1. Introduction

According to biophilia (Wilson 1984) and human evolution-

ary (Ulrich 1981) theories, humans have spent many

thousands of years adapting to the natural environment, yet

have only inhabited urban ones for relatively few generations

(Maller et al. 2006). However, the world has become an urban

society, with a vast number of people becoming alienated

from the traditional people–nature relationship. The modern

urban continuous, distracting stimuli can impede people’s

abilities to focus on significant issues or to achieve relaxed

states (Kaplan 2001; Kim et al. 2017). Viewing nature is con-

sidered one approach to promoting balance and harmony in

the modern urbanite’s life.

Ulrich et al. (1991) argued that a person’s initial response

to an environment is affective. They believed that the initial

affective response to an environment shapes the cognitive

events that follow, leading to sustained attention, higher lev-

els of positive feelings, and reduced negative or stress-related

feelings (Valtchanov et al. 2010). The growing number of

studies supported Ulrich and his colleagues’ argument

and evidenced that viewing natural scenes contributes to

reducing stress, provides more positive psycho-physiological

effects on human systems, and may facilitate recovery from

illness (Shin et al. 2012; Bang et al. 2017; Lee 2017). Cross-

cultural studies also indicate that visual exposure to natural

scenes improves moods, reduces stress, and provides opti-

mal physiological activation (Han 2010; Shin et al. 2011;

Honold et al. 2014; Song et al. 2015; Bang et al. 2017; Lee

2017).

The accumulating evidence of the beneficial effects of

viewing nature prompts an important question: can restor-

ative environments be created and customized to promote a

health benefit and help people who have difficulties visiting

or spending time in real nature? In the modern society, not

everyone can access nature easily. In particular, people with

disabilities, senior citizens, and those with other illnesses can-

not freely seek out natural settings. For these populations,

replicating the restorative effects of nature may be achievable

using indirect nature experiences.

This study experimentally compared the effects of direct

and indirect contact with nature (i.e., virtual nature experi-

ence) on psychological and physiological affect, respectively.

To our knowledge, this comparison of direct and indirect

nature experience and their differential impacts on psycho-

physiological affect, respectively, has not been investigated

experimentally.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty university students aged between 18 and 27 (21.2 §1.7)

years, participated in this experiment. Anyone with

a current or recent history of endocrine, neuropsychiatric,

salivary gland or acute/chronic pain disorders, or who was

using certain disqualifying medicines, was excluded from

participating. Before the experiment, the participants were

fully informed about the aims and procedures involved.

After briefing about the experiment, the participants signed

an agreement to take part in the study. The study was

approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chung-

buk National University (CBNU 201609-BMSB-366-01)

and conducted in accordance with committee’s regulations.

Participants came to the laboratory one at a time by sched-

uled appointments over the course of 8 weeks.

2.2. Experimental design

To compare the effects of direct and indirect nature experi-

ence on psychological and physiological influence, two sets of

experiments were conducted. A nature setting located near

the Chungbuk National University campus in Cheongju,

South Korea was selected for the effect of direct nature expe-

rience. The nature area was flat, bright and well-managed

with mostly pine trees (Figure 1). Physiological and psycho-

logical effects of indirect nature experiences were measured

in a laboratory with an artificial climate maintained at 25C

with 50% relative humidity (Figure 2).

CONTACT Won Sop Shin shinwon@chungbuk.ac.kr

© 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, dis-

tribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

30

J. Y. JEON ET AL.

E-ISSN 2158-0715

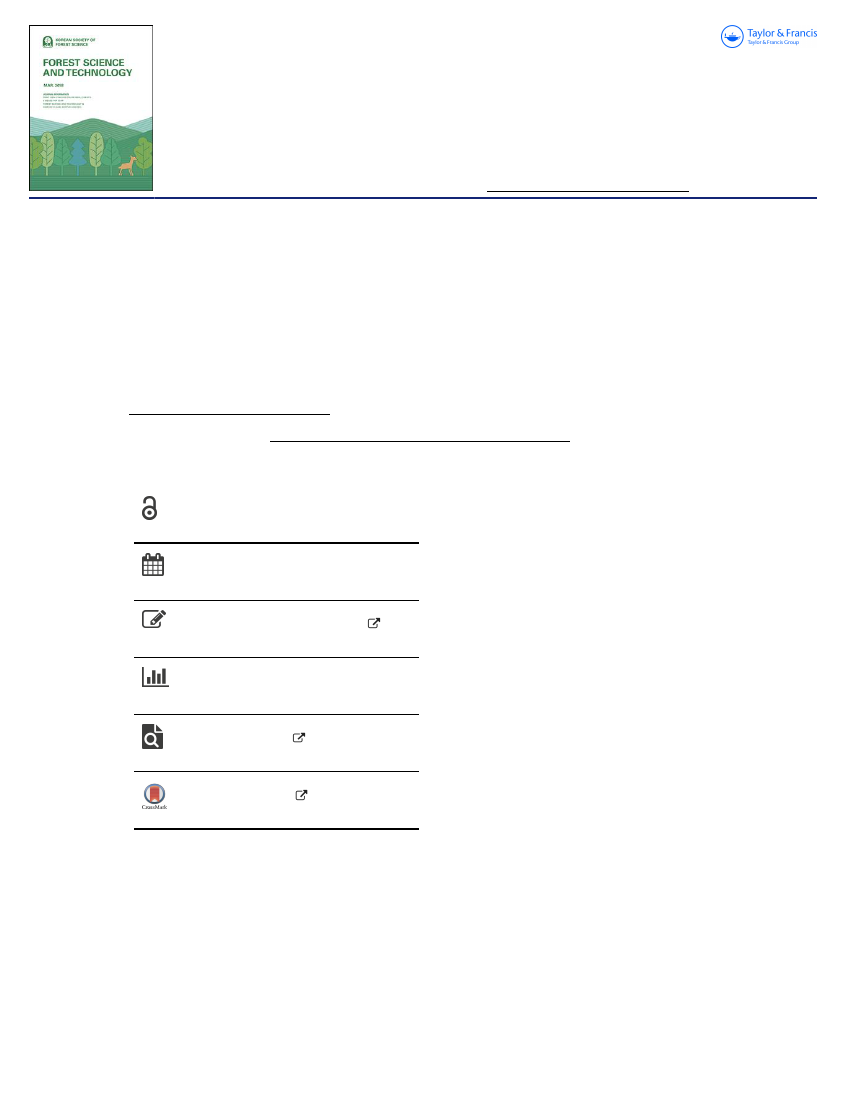

Figure 3. Mood improvement after direct nature experience.

2.5. Profile of mood state (POMS)

Figure 1. Study area for investigating the effect of direct forest experience.

2.3. Heart rate variability

Heart rate variability (HRV) was measured as the periods

between consecutive R waves (R–R intervals) in an electro-

cardiogram recorded with a portable electrocardiograph

(Canopy 9 plus, IEMBIO). The low frequency (LF; 0.04–

0.15 Hz) band and the high frequency (HF; 0.15–0.40 Hz)

band were measured. The HF power was suggested as reflect

parasympathetic nervous activity (Kobayashi et al. 2012).

2.4. Semantic differential method

The participant’s emotional impact was investigated using a

modified semantic differential (SD) method (Osgood et al.

1957). This SD method contains items and each item has a

pair of adjectives, such as “comfortable–uncomfortable.”

The POMS is a commonly employed, factor-based and ana-

lytically derived scale to measure psychological distress. In

this study, the Korean version of POMS was employed to

measure each participant’s six mood states, such as tension

and anxiety (TA), depression (D), anger and hostility (A-H),

vigor (V), fatigue (F), and confusion (C).

3. Results

3.1. Direct and indirect nature experience and mood

state

To investigate the effect of mood states from direct and indi-

rect nature experiences, participants’ mood states were mea-

sured before and after exposure to nature experiences. As can

be seen from Figures 3 and 4, there were significant differen-

ces in t-scores in both direct and indirect nature experience

groups. Specifically, in the direct nature experience group,

participants’ tension and anxiety (TA) (t = 4.65; p = .000),

depression (D) (t = 2.86; p = .008), fatigue (F) (t = 3.70;

p = .001), and confusion (C) (t = 4.64; p = .000) were signifi-

cantly improved at p 0.01 level after exposure to nature.

On the other hand, anger (A) (t = 2.10; p = .044) and vigor

(V) (t = 2.18; p = .038) were improved at p 0.05 level after

exposure to nature. Interestingly, in the indirect nature expe-

rience group, all moods significantly improved at p 0.01

level after exposure to virtual nature [tension and anxiety

Figure 2. Laboratory for investigating the effect of indirect forest experience. Figure 4. Mood improvement after indirect nature experience.

E-ISSN 2158-0715

FOREST SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

31

4. Discussion

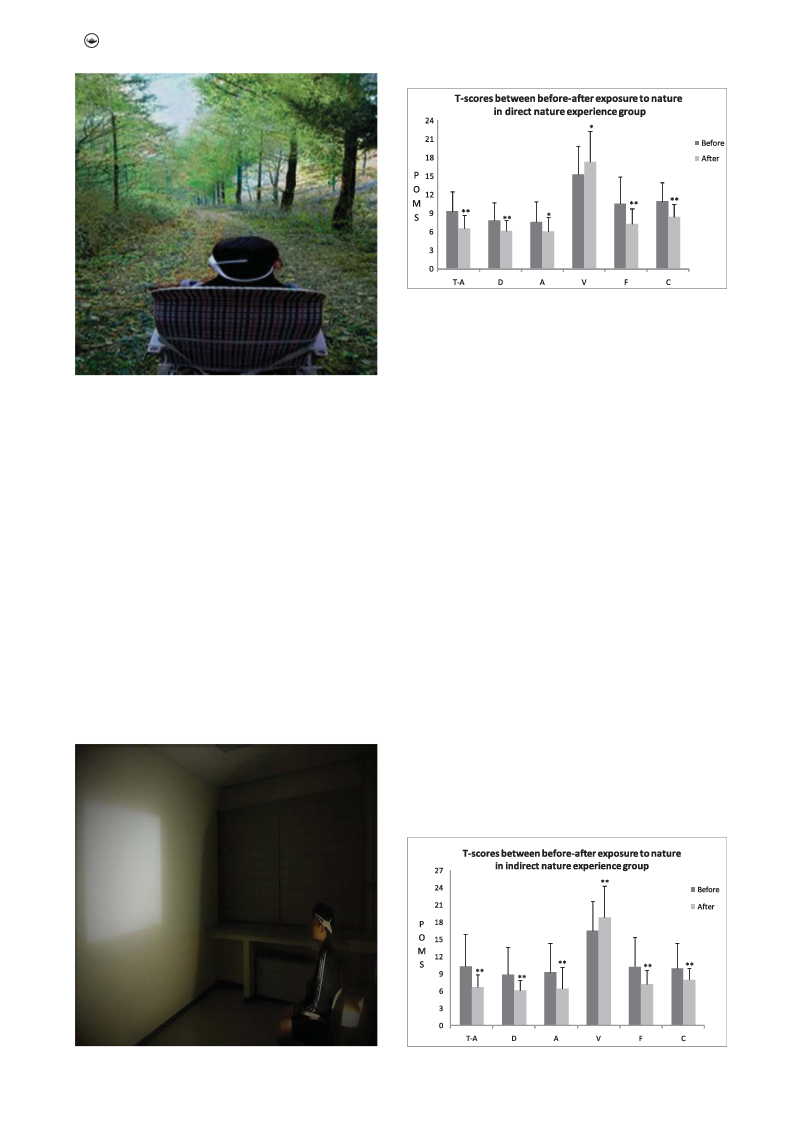

Figure 5. Differences in SD scores between direct and indirect nature

experiences.

(TA) (t = 4.17; p = .000), depression (D) (t = 3.81; p = .001),

anger and hostility (A) (t = 3.74; p = .001), vigor (V)

(t = 2.85; p = .008), fatigue (F) (t = 4.12; p = .000), and confu-

sion (C) (t = 3.16; p = .004)]. The results indicate that those

who had nature experiences either directly or indirectly

obtained positive mood states.

3.2. Semantic differential (SD) method

Figure 5 compares the effects of emotional impact between

direct and indirect nature experiences. Among the three

emotional impact categories, there were significant differen-

ces in “pleasant” (t = 2.39; p = .020) and “natural” (t = 2.60;

p = .012). However, in the “calm” category, no significant dif-

ference was found (t = –.111; p = .912). The results of the SD

comparison indicate that participants who had a direct

nature experience felt higher pleasant and natural feelings

than those who had an indirect nature experience.

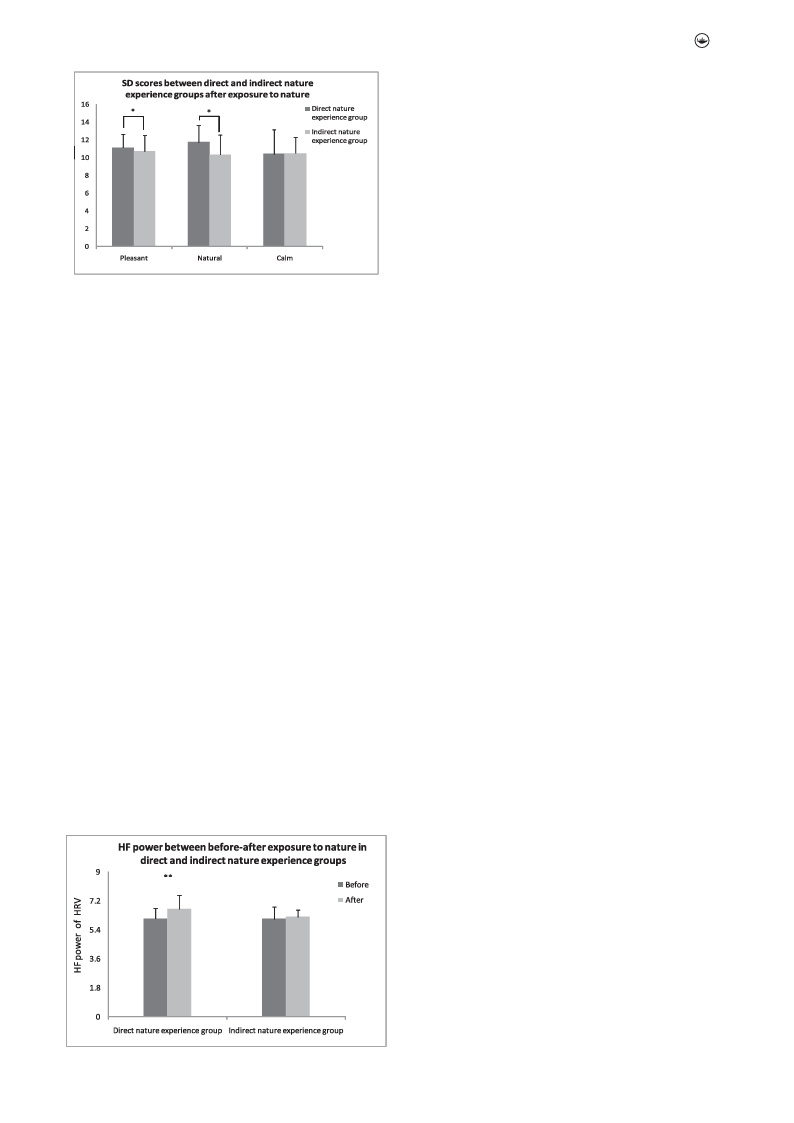

3.3. Parasympathetic nerve activity

The results of analysis to compare the natural logarithm of

HF component, which is known as an estimate of parasym-

pathetic nerve activity, between direct and indirect nature

experiences are shown in Figures 6. As can be seen from

Figure 6, there were significant differences in mean HF values

between before and after in the direct nature experience

group (t = 3.57; p = .001). However, in the indirect nature

experience group, no significant difference was found

between before and after experiences (t = 0.97; p = .336).

Contact with nature has been evidenced to enhance psy-

cho-physiological effect positively (Shin et al. 2012; Beil

and Hanes 2013; Bang et al. 2017; Lee 2017). The present

study was performed to compare the psycho-physiological

effects of direct and indirect nature experience. Although

some previous studies (Ulrich 1984; Valtchanov et al.

2010; McAllister et al. 2017) have reported positive

impacts of indirect nature experiences, very few studies

have reported the impacts of comparison between direct

and indirect nature experiences.

The results of this study indicate that indirect nature expe-

rience provided positive psychological and physiological

effects as direct nature experience did, except parasympa-

thetic nerve activity. The findings in this study are consistent

with the Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) Attention Restoration

Theory (ART) that nature provides human restoration. The

findings also are in line with Ulrich’s argument that contact

with nature provides positive physiological responses.

The present study results indicated that exposure to

virtual nature can produce significant improvement in affec-

tive states. Modern technology in virtual reality (VR) would

allow for the complete customization and creation of restor-

ative environments (Valtchanov et al. 2010). The results of

the present study would support the effectiveness of virtual

nature for people who cannot easily access real nature. People

with disabilities, patients, inmates, and workers in remote

areas are in urgent need of experiencing nature to obtain pos-

itive psycho-physiological benefits. The present study can

provide strong justification for providing virtual nature.

The findings of the present study indicate that even

brief, virtual nature experience can enhance affect, and

emphasizes the necessity of indirect nature experience for

special populations who cannot easily access real nature.

The experimental constructs employed in this study may

have some limitations that can be addressed by future

research. Relatively small sample size and a homogeneous

group in this study may limit its statistical power. Further

research should consider including more participants from

diverse populations. Especially, studies with large numbers

of participants from different population groups may gen-

eralize the results of this study. Although the physiological

measure did not show a significant difference in HRV

response between before and after exposure to indirect

nature, the measures on psychological effects suggest that

a large variety of content needs to be made available in

order to achieve compatibility with a large number of peo-

ple. Duration of exposure to indirect nature and content

of nature may cause the insignificant difference in HRV.

Further research with different content of nature, different

duration to exposure and different population may be

needed to confirm the findings of this study.

Figure 6. HF changes after nature experiences.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the psycho-physiological effects of

direct and indirect nature experiences. The results of this

study showed that exposure to real and virtual natural envi-

ronment appears to be beneficial to participants’ moods and

feelings. However, exposure to the real natural environment

tends to be more beneficial in physiological response (para-

sympathetic nerve activity) than exposure to virtual nature.

32

J. Y. JEON ET AL.

E-ISSN 2158-0715

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Bang KS, Lee I, Kim S, Lim CS, Joh HK, Park BJ, Song MK. 2017. The

effects of a campus Forest-Walking program on undergraduate and

graduate students’ physical and psychological health. Int J Environ

Res Public Health. 14(7). doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070728

Beil K, Hanes D. 2013. The influence of urban natural and built environ-

ments on physiological and psychological measures of stress- a pilot

study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10(4):1250–1267.

Han KT. 2010. An exploration of relationships among the responses to

natural scenes: scenic beauty, preference, and restoration. Environ

Behav. 42(2):243–270.

Honold J, Lakes T, Beyer R, van der Meer E. 2014. Restoration in urban

spaces: forest views from home, greenways, and public parks.

Environ Behav. 48(6):796–825.

Kaplan R. 2001. The nature of the view from home psychological

benefits. Environ Behav. 33(4):507–542.

Kaplan R, Kaplan S. 1989. The experience of nature: a psychological

perspective, Michigan: Ulrich’s: Ann Arbor.

Kim J, Kil N, Holland S, Middleton WK. 2017. The effect of visual and

auditory coherence on perceptions of tranquility after simulated

nature experiences. Ecopsychology. 9(3):182–189.

Kobayashi H, Park BJ, Miyazaki Y. 2012. Normative references of heart

rate variability and salivary alpha-amylase in a healthy young male

population. J Physiol Anthropol. 31(1):1–8.

Lee J. 2017. Experimental study on the health benefits of garden landscape.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 14(7). doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070829

Maller C, Townsend M, Pryor A, Brown P, St Leger L. 2006. Healthy

nature healthy people: ‘contact with nature’ as an upstream health

promotion intervention for populations. Health Promot Int. 21(1):

45–54.

McAllister E, Bhullar N, Schutte NS. 2017. Into the woods or a stroll

in the park: how virtual contact with nature impacts positive and

negative affect. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 14(7). doi:10.3390/

ijerph14070786

Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH. 1957. The measurement of

meaning. Oxford, England: Univer. Illinois Press. (The measurement

of meaning).

Shin WS, Shin CS, Yeoun PS. 2012. The influence of forest therapy camp

on depression in alcoholics. Environ Health Prev Med. 17(1):73–76.

Shin WS, Shin CS, Yeoun PS, Kim JJ. 2011. The influence of interaction

with forest on cognitive function. Scand J Forest Res. 26(6):595–598.

Song C, Ikei H, Kobayashi M, Miura T, Taue M, Kagawa T, Li Q,

Kumeda S, Imai M, Miyazaki Y. 2015. Effect of forest walking on

autonomic nervous system activity in middle-aged hypertensive

individuals: a pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 12(3):

2687–2699.

Ulrich RS. 1981. Natural versus urban scenes: some psychophysiological

effects. Environ Behav. 13(5):523–556.

Ulrich RS. 1984. View through a window may influence recovery from

surgery. Science. 224(4647):420–421.

Ulrich RS, Simons RF, Losito BD, Fiorito E, Miles MA, Zelson M. 1991.

Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments.

J Environ Psychol. 11(3):201–230.

Valtchanov D, Barton KR, Ellard C. 2010. Restorative effects of virtual

nature settings. Cyberpsychol, Behav, Soc Netw. 13(5):503–512.

Wilson EO. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.