Creative Arts Educ Ther (2017) 3(2):3–16

DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2017/3/2

The ‘Green’ Mandala: Where Eastern Wisdom meets

Ecopsychology

“绿色”曼陀罗:东方智慧遇到生态心理学

Alexander Kopytin

St.-Petersburg Academy of Post-Graduate Pedagogical Training,

Russia

Abstract

Mandalas are circular images often created in various religious and indigenous traditions. Due to

the development of Jungian analysis and transpersonal studies diagnostic and therapeutic poten-

tial of the mandala was extensively explored. Analytical psychologists and art therapists under-

stand visualized or created mandalas of their clients as the symbolic mirror of the psyche, a

means of containing and integrating its energies, both conscious and unconscious dynamics and

states of mind.

This paper presents ecological and environmental perspectives on our understanding and ther-

apeutic application of the mandala as an expressive/creative tool that helps to bring the arts and

nature together and provide bene cial effects both for human and nonhuman worlds. Basic theo-

retical, ethical and instrumental ingredients related to the ‘green’ mandala, or eco-mandala, together

with case vignettes illustrating their therapeutic application and functions will be presented.

Keywords: mandala, environmental, ecopsychology, ecotherapy, art therapy

摘要

曼陀罗是通常在各种宗教和土著传统中创建的圆形图像。由于荣格分析和超个人研究的

发展,对曼陀罗的诊断和治疗潜力进行了广泛的探索。分析心理学家和艺术治疗师将他

们客户的可视化或创造的曼陀罗理解为心灵的象征性反映,这是一种遏制和整合其能量

的手段,既有意识的也有无意识的动态和精神状态。

本文将我们对曼陀罗的理解和治疗应用的生态和环境视角作为一种表现力/创造性工

具,帮助将艺术和自然融合在一起,并为人类和非人类世界提供有益的影响。本文还将

介绍与“绿色”曼陀罗或生态曼陀罗相关的基本理论、道德和机制成分,以及说明其治

疗应用和功能的案例简介。

关键词: 曼陀罗, 环境, 生态心理学, 生态疗法, 艺术疗法

Introduction

The term ‘green mandala’ is introduced here to de ne either pre-existing natural circular

forms or those created by humans (co-creating together with nature) along with the use of

natural materials and environments. The mandala will be presented as an eco-psychological

Creative Arts in Education and Therapy – Eastern and Western Perspectives – Vol. 3, Issue 2, December 2017.

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

4

Alexander Kopytin

concept and a form of eco-art therapy practice which helps to achieve both individual

health and well-being and also meets public and environmental health outcomes. The

perennial nature of the mandala as one of the core symbols of the spiritual traditions of

East and West will be considered within the context of the modern psychological idea of

the personality – along with its relationships to wider social and environmental networks.

This will enable a deeper understanding of the creation of the mandala as an environmen-

tal action – rooting it not so much in the need of creative self-expression (in the traditional

Western sense of the word) but within a strong motivation to support and serve both nature

and life.

The human inclination to interact with and create mandalas will be explored through

the perception of natural environments and living forms both as a kind of a supportive

eld and as a living entity. These environments and forms can be highly attractive to

humans – not only due to their practical value but also because of their aesthetic, cogni-

tive, and spiritual meanings and their ability to support inner harmony and nature within

human beings.

As any other method or instrument applied in ecopsychology and ecotherapy (and eco-

art therapy as one of its forms), making mandalas out of natural materials and/or within

natural environments is based on the premise that the health of the planet impacts our health

and acknowledges that a certain synergy between the well-being of communities, individ-

uals and the environment (in which they live) does exist. The central goal of creating and

using the mandala from both an eco-psychological and eco-therapeutic perspective is to

achieve well-being as an inner state of wellness; such wellness includes physical, mental

and emotional states of consonance which exist in a healthy environment.

The mandala in cultural traditions and as a psychological

concept and therapeutic instrument

A mandala is a spiritual and ritual symbol in Hinduism and Buddhism, representing the

universe. In common use, ‘mandala’ has become a generic term for any diagram, chart

or geometric pattern that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically; a

microcosm of the universe. It can be acknowledged that the circle as a natural form and

a human creation symbolizes many things for different people and provides healing in

cultural traditions worldwide.

Contemporary interest in the mandala was initiated by Jung who prompted research

relating this phenomenon within Western psychotherapy. Jung adopted the Sanskrit

word ‘mandala’ to describe the circular drawings he and his patients did. Jung observed

the mandala in his own as well as his patients’ dreams and drawings which had been

composed during certain states of mind. The discovery of the mandala led Jung to aban-

don the idea of the superordinate position of the Ego and inspired him, instead, to

formulate the theory of the Self and the individuation process (Jung, 1973, 1976).

The appearance of the mandala in patients’ dreams and artworks is usually inter-

preted as a representation of human wholeness or as a re ection of a psychological

centripetal process through which the personality achieves or restores inner balance and

harmony. Since Jung, the mandala has been used as a therapeutic instrument in a number

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

The ‘Green’ Mandala: Where Eastern Wisdom Meets Ecopsychology 5

of different ways. It is often applied in psychodynamic, insight-oriented therapy – giving

a client the means by which to externalize the inner processes and states of their mind

and to integrate certain idiosyncratic experiences and qualities too. The making of the

mandala itself becomes a projective instrument of centering and balancing personality

as well as a meditative and relaxing procedure that re ects or anticipates states of Ego-

Self integration and the individuation process. Mandala making can be also used outside

insight-oriented psychotherapy as a form of healing or self-help practice that helps to

reduce or prevent stress-related symptoms and achieve psychological integration.

The interpretation of the mandala in psychology is, however, different and is depen-

dent on the particular theory of the personality implied. As Hillman (1995) states, “There

is only one issue for all psychology. Where is the “me”? Where does the “me” begin?

Where does the “me” stop? Where does the “other” begin? ...For most of its history,

psychology took for granted an intentional subject: the biographical “me” that was the

agent and the sufferer of all “doings”. For most of its history, psychology located this

“me” within human persons de ned by their physical skin and their immediate behavior.

The subject was simply “me in my body and in my relations with other subjects”.

(p. xvii)

Over the past few years, these ideas of the personality have been revisited with a

view to gaining a new perspective on the idea of personality and its relationships with

the world surrounding it. Hillman believed that “Adaptation of the deep self to the col-

lective unconscious and to the id is simply adaptation to the natural world, organic and

inorganic. Moreover, an individual’s harmony with his or her “own deep self” requires

not merely a journey to the interior, but a harmonizing within the environmental world”.

(Hillman, 1995, p. xix).

The mandala as a representation of the human connection

with the natural environment

Visualizing and making mandalas cannot be perceived only as an inwardly-oriented

process but can also be seen as a means of relating to the environment. Such procedures

can involve an attunement to various environmental phenomena by which not only the

inner processes of the body and the psyche can be externalized and brought to the con-

scious mind, but qualities and resources implied within the environment can also be

internalized – so both inner and outer worlds can come together.

This core function of the mandala can be explored through an acquaintance with the

processes of human environmental creation from prehistoric times – for with the devel-

opment of such disciplines as environmental psychology and ecopsychology, a new

perspective on and understanding of the mandala as a tool both for therapy and for the

harmonizing of human relationships alongside the natural environment has been cre-

ated. Holistic therapies, various ‘green movements’ and post-modern environmental and

ecological arts now help to expand our understanding of the mandala as an expression

of the human need to re-establish healthy bonds with the environment.

Furthermore, the human inclination to create and use man-made circular forms in

healing and spiritual practices (including those related to the natural environment) can

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

6

Alexander Kopytin

be considered as an expression of the human instinct of mutually supportive relationships

with nature and a healthy resonance with many circular forms abundant in the natural

world. This inclination can be explained from the perspective of the biophilia hypothesis

(Wilson, 1984, 1993), which postulates the existence of a pervasive attraction that draws

people to nature with its different mineral, plant and organic forms and often implies

circular structures as representative of a healthy and contained life.

This biophilia hypothesis is also based on the presumption that our relationship with

these natural forms can be mutually supportive – going beyond their practical value as

food or medicine and often enabling us to perceive them as emotionally compelling

symbols.

Creating the green mandala can be acknowledged as a viable expression of the art

of biophilia. (Kopytin, 2016) de ned this as a form of creative activity within natural

environments (green spaces). The act of creating the mandala from natural materials

appears to share similar qualities with (and to be based upon) the values and principles

of the Japanese art of Ikebana. This revered practice is a blend of aesthetic and spiritual

expression and seeks composure, balance, and clarity within a structured re ection of

the fully formed self.

Environmental psychology helps to expand our understanding of the mandala as a

dynamic representation of the positively constructive interplay between individuals and

their surroundings. This perception of our constructive human interaction with the envi-

ronment can be enriched through the use of concepts such as the personalization of

space/environment (Gregory, Fried, and Slowik 2013; Heimets 1994) as it relates to

psychosocial aspects expressed through territoriality and, additionally, people’s need to

maintain a sense of belonging, ownership and control over their space.

Personalization can also be de ned as human behavior focused on bringing the dis-

tinctive features of an individual to bear on the environment. Personalization provides

people with a greater sense of ownership and control over a space and helps to establish

and maintain a sense of individuality (identity). As a result of the personalization and

appropriation of a space, existing ego-structures can be brought forward to and expressed

within the environment, and a further development and reconstruction of the personality

and appropriation of new, positive characteristics of identity becomes possible. The act,

therefore, of creating the green mandala can be expressed as an ecological form of per-

sonalization based on sustainable and supportive human interactions with the natural

world.

Creating the mandala as an expression both of the art of biophilia and as an ecolog-

ical form of personalization can be related to the ecologically grounded personality

theory which requires the development of personality be recognized as taking place

within a wider matrix of existence – including those with natural environments. This

awareness of various acts of personalization and appropriation of the natural environ-

ment and an additional acknowledgement of the subsequent effects on human beings has

paved the way for a developmental personality theory with the main focus on the for-

mation of an Eco-Identity, “... a kind of self-perception and self-understanding that is

linked to one’s sustaining relationship with nature and her/his involvement in some

positive activity in or with nature.” (Kopytin, 2016, p.21).

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

The ‘Green’ Mandala: Where Eastern Wisdom Meets Ecopsychology 7

Eco-Identity can be established (and subsequently developed) when a person

becomes involved in some activity involving nature – including the expressive/creative

acts. The arts can be regarded as one type of environmental action with a strong self-

regulating function – together with many other activities which are typical examples of

eco-therapy: gardening, animal encounters, spending more time in ecologically healthy

settings or, additionally, actively working on maintaining and restoring eco-health.

Materials and environments implied in creating the green mandala

Materials

Creating the mandala as a form of environmental and ecological expressive therapeutic

practice can take place either indoors or outdoors, but must use mostly natural materials

and forms. An increase in the varieties, structures, and types of materials (including such

botanical ephemera as vines, leaves, fruits, owering branches, owers and seed pods

as well as different kinds of soils, sand, stones, etc.) yields a richer, more complex sen-

sual and symbolic eld for the client’s exploration. Various art and junk materials, both

found and man-made items and clients’ personal belongings can be used too.

The signi cance of natural materials and botanical ephemera, however, must be

given particular emphasis because of their ability to evoke biophilic reactions. Botanicals

also “acquire metaphorical vitality that individuals may experience at different con-

scious and unconscious levels of experience. Within [such an] interwoven relationship,

it is unsurprising that botanicals become signi ers of speci c human events as a part of

the common language...simply touching, smelling and arranging botanical ephemera

into pleasing symmetries can bring pleasure, alertness, and a sense of accomplishment.”

(Montgomery & Courtney, 2015, p.19)

Diehl (2009) believes that “The multitudes of fragrances, color, textures, tastes and

sounds of plants awaken our senses.” She further explains that “sensory stimulation helps

us connect with nature by engaging us physically, cognitively, and emotionally” (P.169).

Such natural circular or spherical forms as owers and fruits are abundant in nature and

are often perceived as signi cant symbols of wholeness, harmony and protection; these

support our link to the environment and enhance our ability to create similar forms.

Environment

The practice of creating mandalas as other types of activities typical for nature based or

ecological therapies can take place in the wide environmental continuum. Some of these

outdoor forms can be characterized by greater biodiversity, while working indoors

requires an appropriate supply of natural materials. If time, weather and seasonal con-

ditions permit, most (or at least some part) of the session can take place outdoors.

Outdoor spaces used for such activities can vary considerably.

Urban spaces devoid of all forms of nature can be dif cult to nd. Some environ-

ments with a great diversity of plant forms can be discovered even in the midst of the

city. Such spaces usually include at least some natural forms and some botanical ephem-

era with which participants can interact. Most towns and cities usually include such

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

8

Alexander Kopytin

‘green’ spaces as parks or gardens, etc. Today, national and international policies support

the inclusion of the natural environment in the promotion of holistic health.

Creative activities involving mandala making can be arranged in such speci cally

accessible green areas as part of a hospital, a rehabilitation center, a shelter or a residen-

tial home etc. These activities may also be aligned to a private practitioner’s of ce as

well as to municipal areas (parks, gardens, the beach etc.) or the ‘wild’ environment. As

far as working outdoors is concerned, speci c variations and a differing quality of envi-

ronmental perception should be taken into consideration. The perception of an

environment and subsequent modes of engaging with it can, however, depend not only

on its quality but on the participants’ intentions and attitudes.

Therapeutic and restorative activities based on creating

‘green mandalas’

Creating mandalas as a form of ecotherapeutic/eco arts therapeutic practice is not only

expressed within the original theoretical positions presented (above), but is also explored

through practical implementation. The process of creating the green mandala occurs in

three phases and is similar to Scull’s (2009) nature-connecting – including preparation,

experience and debrie ng of the experience.

The rst phase introduces clients to the theme of creating the green mandala as a

special form of eco arts therapeutic activity and also to the materials needed for such a

session. Some indoor (or outdoor) warm-up activity helps to awaken the participants’

sensory awareness through touch, taste, smell etc. of surrounding natural spaces, objects

and materials and provides a change in the participants’ perception of their environ-

ment. Establishing a focus on the topic to be explored and choosing a question or

situation that will be most relevant for the day is usually included in this part of the

session too.

The second phase is the actual working session where clients create the mandala and

interact with it (or through it) with themselves and with the environment. They can

install their mandala in the landscape or use such action-based creative activities as

performance, dance and movement, personal or group rituals or multimedia events.

More concentrated forms of re ective and creative activity such as journaling or creat-

ing narratives can also be implemented in this session. In the third phase, clients step

back from their creations and observe and discuss their work they have completed –

allowing both insight and perspective.

Assignments related to creating mandalas can be open-ended or based on certain

themes. Open-ended assignments encourage participants to walk outdoors in the envi-

ronment or to explore natural materials indoors and pay attention to scenery or objects

they nd most interesting or appealing for them; they can task them to select materials,

or simply take photographs or draw scenery or objects. Sessions can be more focused

on particular topics or themes as “The mandala as a response to my question/aspiration,”

“The mandala as a gift of nature,” “The mandala as a message from the environment,”

“The mandala as an expression of Nature’s wisdom,” “The mandala as a union of

subjects” or “The mandala as my personal ‘mirror” etc.

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

The ‘Green’ Mandala: Where Eastern Wisdom Meets Ecopsychology 9

FIGURE 1 | The mandala made by 72-year old woman and explained as a symbol of her

experience related to aging.

There are many ways to create such mandalas. They can take a circular form con-

structed of botanical arrangements (Montgomery and Courtney, 2015) and can be made

up of different botanical ephemera enclosed in some vessel or bound together in the

fascicle or wreath. An example of creating such a mandala as a form of botanical

arrangements related to the subject of aging is visible in artwork made by a 72-year old

woman who participated in the eco-art therapy group session (Figure 1). Though the

session itself took place indoors in Manhattan, New York, the participants were encour-

aged to use various botanical ephemera that had been found in Central Park by the team

leader and then brought to the session. Some additional greenery had also been pur-

chased at one of the nearby markets. At the beginning of one session, the therapist gave

the group the chance to explore and seek out any natural materials available and then to

select and use some of them in order to create a small personal green mandala. The

therapist recommended that participants use cardboard circles up to 25 cm in diameter

as a holding space for their botanical arrangements.

Upon completing her artwork, 72-year old woman commented it in the following way:

‘I could say that it was an organic and unconscious process, led by the tex-

tures and colors of the materials. I was aware that it was a bit “off-center” in

that it didn’t have the usual symmetrical form of a traditional mandala. I

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

10

Alexander Kopytin

actually enjoyed that it seemed to ‘ ow’ off to the right and was a bit

whimsical and light. It also has a strong feminine quality which pleases me

too as I have been exploring that side of myself. It feels grounded and also

possesses a quality of releasing and owing; this mirrors my life at the

moment. I have enjoyed the tactile and sensorial experience of working with

the natural materials even though the workshop itself was held in a rather

sterile interior and urban environment.

I nd my mandala to be a good representation of the complex meanings

related to aging. I can refer it to Wabi-Sabi, beauty found in the simple,

imperfect, old, worn, weathered objects and natural forms. These qualities

of “beauty consciousness” that were revealed through the process of creat-

ing my green mandala can assist us in seeing beauty in the older human

being and can also guide us toward recognizing this same beauty within

ourselves as we age. This aesthetic form and this philosophy of life can help

us to become aware of aging as a creative act...’

Another example of using the mandala as a form of botanical arrangement which

relates to self-perception can be seen in the creative activity of drug and alcohol abusers

who participated in interactive art therapy as a part of their rehabilitation program at a

specialized day center unit in St. Petersburg. The group conductor encouraged the par-

ticipants to walk in a park close to the center during the month of September in order to

search for natural materials. Later, members of the group created botanical arrange-

ments in the studio by arranging their ndings on paper plates.

The group conductor’s idea was that, through the use of some environmental tasks,

clients could be facilitated to move into a more open space as a newly symbolic repre-

sentation of their more autonomous functioning. This activity also helped patients to

frame and reframe their self-perceptions, to nd meaning in the environment and to

appropriate and personalize it. The conductor encouraged participants to work with

either an open-ended format (with no particular topic chosen beforehand but simply a

spontaneous response to the environment where they chose any natural objects that they

found attractive or meaningful), or on the focusing on a topic as “Self-image object”.

While taking a walk outdoors, group members could ask themselves ‘Is there some

natural object (or objects) in the environment that I feel connected to, have some af nity

with, or which can represent my personality?’

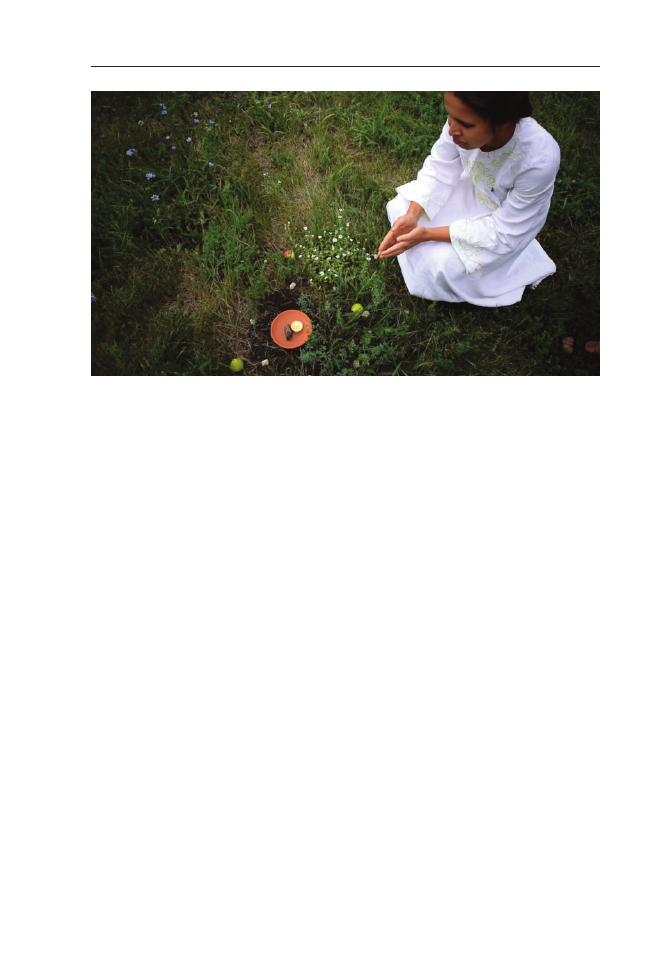

On presenting his creation (Figure 2), one of the participants (aged 36) describes

how this figure is associated with his life in the last few years – a time when he has

perceived himself as running in a circle. He believes, however, that a small break

he noticed at the top of his mandala may signify his overcoming his addiction and

beginning a healthy new life. He associates acorns with the potential for new

growth.

A mandala can also be viewed as an environmental installation or construction, for

it shares certain similarities with megalithic creations and contemporary artists’ environ-

mental or eco-art projects, gardens, labyrinths and other ‘green spaces’ as well as circular

‘homes in nature’ used for centering, healing and contemplation.

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

The ‘Green’ Mandala: Where Eastern Wisdom Meets Ecopsychology 11

FIGURE 2 | Botanical arrangement which represents self-perception of one group member.

In sessions involving creating the green mandala, a mindful interaction with the nat-

ural environment and forms is the most signi cant component of such a process. It can

be a means of connecting the symbolic forms of art and language with the participant’s

immediate physical experience of the natural world (the life process). Creating the green

mandala (and other such related activities) can be considered as a means of developing

both a somatic awareness and an embodied sense of self in one’s relationship to the envi-

ronment. This effect is more obvious when clients’ involvement in outdoor activities is

combined with both mindfulness and certain body-centered exercises and when emphasis

is placed on meditative journeys or path-working as a form of mini-pilgrimage in ‘the

green area’ and is subsequently accompanied or followed by green mandala making.

An example of such a creative process can be seen when an environmental mandala

is made during the continuation of an environmental mindfulness-based art therapy

session (Peterson, 2013) which included a meditative journey taken by a 33 year old

femals psychologist. into an institutional green area. She also used a selection of natural

materials She participated in the session with other professionals; this group’s goal was

to learn ways of developing self-regulating, stress-management skills and mindfulness

techniques based on their creative interactions with the natural environment.

At the beginning of one session, a therapist offered a group the possibility of spending

one hour outdoors in order to explore the institutional environment of the community center

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

12

Alexander Kopytin

where sessions were taking place. This was an enclosed eld with a sports ground, some

wild plants and apple, pear and birch trees. The therapist explained that the participants were

allowed to select and use any types of organic materials available on the institutional grounds

– these included vines, leaves, fruit, branches, and seed pods, wild owers and other botan-

ical ephemera. Members of the group could also use stones, soil, sand and water.

Participants were encouraged to take a meditative journey through this environment

and to nd some natural materials and objects that they could then arrange as a small

personal mandala. The therapist recommended that participants use small ceramic con-

tainers, plates or cups up to 12 cm in diameter as a holding space for their botanical

arrangements. They also encouraged the participants to nd some place within the envi-

ronment to install their creations and to arrange the surrounding area, if need be. Later

they were invited to present a brief performance – a ritual in the environment – and to

interact with their green mandalas as meaningful objects. This part of the session was

subsequently followed by participants sharing their experiences and discussing the

meanings implied in both their creations and in their performances.

When the group participants completed their green mandalas and were ready to

perform in the space where they had installed their creations, a 33 year-old woman per-

formed a kind of a ritual. She invited the group to join in her ritual by following her as

she slowly moved around her green mandala which had been placed on the ground. She

then stopped and sat on the ground in front of her creation and made some movements

with her hands as if she were expressing her reverence to the space and her creation.

When she nished her ritual she explained:

“I want my green mandala to be included in the living environment. I’ve

chosen a place in the middle of this space encircled with blue chicory owers.

I need a heavenly color. You can see the two apple trees standing from the

both sides of this space. I noticed a little spot in the middle and created some-

thing like a personal shrine putting my vessel of the green mandala here.

I also put few stones, apples and pears around it in order to mark bound-

aries. It is important to provide a variety of live forms and biological diversity

since this provides endurance for the ecological system. I put water in the

vessel and sprinkled water around it. If you come closer you can see ants,

spiders and other insects running. All of them are inhabitants of this space

and are happy to nd that I have left some food for them.

I put a little stone in the vessel too. It is a traditional Japanese symbol of

mountains. If there is no any natural rock or hill in the garden people bring

stones to signify rocks or mountains. You can see that my green mandala

includes a mountain in the form of a stone and lake in the form of water.”

Another participant, a 37 year old man, a school teacher, commented on his experi-

ence in the following way:

“I intuitively searched for natural materials for my green mandala in the

beginning, and recognized what my creation means later. I’m astonished to

discover that nature provides such a great variety of forms and it is very

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

The ‘Green’ Mandala: Where Eastern Wisdom Meets Ecopsychology 13

FIGURE 3 | Group participant performing her ritual in front of her mandala installed

in the space.

creative, but we don’t value that most of the time. It is often dif cult to see

even a small part of this great variety when we are absorbed in out routine

everyday activities. Today I was lucky to notice and explore this variety of

natural beautiful forms and colors abundant even in this small spot of land.

You can see the apple in the center of the composition surrounded with

water, soil, stones and many owers and herbs. Everything is included in the

small plate of my green mandala. I put my creation in the center of the hatch

which symbolizes a circle of our daily routine.”

A 42 year-old woman, a university teacher, invited people to stand in the circle and

pass her green mandala through their hands. She said:

“I was sitting on the ground watching the environment around me in the

beginning. At certain moment I got a feeling that I’m dissolving in nature.

When I stood up and started to search for natural materials around I noticed

small plants and shoots. All of them are so beautiful, tiny, and wonderful, but

I didn’t notice that before.

It was a spontaneous process of selecting natural forms that I found most

interesting and attractive for me in the beginning. I didn’t want to rip and

destroy plants so I preferred to take the whole plants including their roots

and transport them into the environment of my green mandala. You can see

the two little plantains inside. I planted them in the soil that I’d put in the

vessel and sprinkled them with water. These plants can grow now. Everything

is so small and has a certain Japanese quality. This evokes a special feeling.

I felt that when I was making my green mandala. It serves as a small holo-

gram of the world.

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

14

Alexander Kopytin

FIGURE 4 | Green mandala created by 37 year old man – a school teacher.

FIGURE 5 | Green mandala created by 42 year old woman.

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

The ‘Green’ Mandala: Where Eastern Wisdom Meets Ecopsychology 15

When I completed my creation I started to walk around carrying my

creation in a meditative state of mind with me. I realized that I can take a

small part of this beautiful wonderful natural environment in my hand and

even share it with other people. I can pass my green mandala through the

circle of people now. You can feel its warmth created with my hands and

with the little candle burning in the middle. Later, I can put my creation

somewhere. I can separate from it now and know that it needs separation too.

It has its own life now and it is free. Perhaps I’ll take it with me and put it

on a table during lunch time.”

Conclusion

Both the ecological and environmental perspectives on the therapeutic application of the

mandala presented in this article help us to understand and de ne it as an expressive/

creative tool which brings both the arts and nature together to provide therapeutic,

health-promoting effects. The human inclination to create circular symbolic forms of

natural materials (often in relation to the natural environment) can be considered from

both an ecological and environmental viewpoint as an expression of the human instinct

to create a mutually supportive relationship with nature. This inclination can be

explained, in particular, via the biophiliahypothesis which postulates a pervasive attrac-

tion between humans and nature in all its differing mineral, plant and organic forms. It

focuses, too, on circular structures as representations of a healthy and contained life.

The mandala as an ecological artwork made from natural materials and/or in nature

serves as a special instrument for providing physical and psychological healing as a

result of a positive biophilic human relationship with nature. As with any other method

or instrument applied in eco-psychology and eco-therapy such mandala-making is based

not only on the premise that the health of the planet impacts our health but also on the

notion of collective synergy between the well-being of communities, individuals and the

environments in which they live.

Creating the mandala as eco art therapy practice can be a viable expression of the

art of biophilia (Kopytin, 2016), a form of creative activity in and with natural environ-

ments (green spaces) and rooted not so much in the need of creative self-expression in

the traditional sense of this word, but on a strong motivation to support and serve nature

and life. The act of creating such mandala can be understood as an ecological form of

personalization of the environment which supports the establishment and further devel-

opment of Eco-Identity, an aspect of self-perception and of self-attitude implying ones’

feeling and understanding of a vital connection to nature, the eco-system which implies

one’s responsibility towards and stewardship of nature.

The brief case studies presented here illustrate a variety of ways in which the pro-

duction of the green mandala can be factored into the therapeutic processes of different

client groups, This creative action can take place either indoors or outdoors using mostly

natural materials and forms. These vignettes demonstrated that the process of creating

the green mandala occurs in several clearly delineated phases: nature-connecting, prepa-

ration, experience and debrie ng of the experience (Scull, 2009). These examples also

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

16

Alexander Kopytin

indicate that creating such mandalas as an eco art therapeutic activity (when clients are

safely grounded in some natural space and forms) helps them to perceive themselves in

an holistic way, and allows them to view their mandala as the container of embodied

sensory, perceptive, emotional, imaginative, symbolic and spiritual experiences. This

allows the participants to come to a more balanced and healthy understanding of

themselves and their relationships.

About the author

Alexander Kopytin is a psychiatrist, psychotherapist, professor in the psychotherapy

department at Northwest Medical I. Mechnokov University, head of postgraduate train-

ing in art therapy at the Academy of Postgraduate Pedagogical Training at St. Petersburg,

and chair of the Russian Art Therapy Association. He introduced group interactive art

psychotherapy in 1996 and has since initiated, supported, and supervised numerous art

therapy projects dealing with different clinical and non-clinical populations in Russia.

References

Diehl, E. R. M. (2009). Gardens that heal. In L. Buzzell & C. Chalquist (Eds.), Ecotherapy: Healing with

nature in mind (pp. 166–174). San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Gregory, L. A., Fried, Y., & Slowik, L. H. (2013). “My space”: A moderated mediation model of the

effect of architectural and experienced privacy and workspace personalization on emotional exhaustion

at work. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 144–152.

Heimets, M. (1994). The phenomenon of personalization of the environment. Journal of Russian & East

European Psychology, 32(3), 24–32.

Hillman, J. (1995). A psyche the size of the Earth. In T. Roszak, M. Gomes, & A. Kanner (Eds.),

Ecopsychology. Restoring the Earth, healing the mind (pp. xvii–xxiii). San Francisco: Sierra Club

Books.

Jung, C. (1973). Mandala symbolism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. (1976). Symbols of transformation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kopytin, A. (2016). Green studio: Eco-Perspective on the therapeutic setting in art therapy. In

A. Kopytin & M. Rugh (Eds.), Green studio: Nature and the arts in therapy (pp. 3–26). New York:

Nova Science Publishers.

Montgomery, C. S., & Courtney, J. A. (2015). The theoretical and therapeutic paradigm of botanical

arranging. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, 25(1), 16–26.

Peterson, C. (2015). “Walkabout: Looking In, Looking Out”: A Mindfulness-Based Art Therapy Program

for Cancer Patients. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 32(2), 78–82.

Scull, J. (2009). Tailoring nature therapy to the client. In L. Buzzell & C. Chalquist (Eds.), Ecotherapy:

Healing with nature in mind (pp. 140–148). San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. (1993). Biophilia and the conservation ethic. In S.R. Kellert & E.O. Wilson (Eds.), The

biophilia hypothesis (pp. 31–40). Washington, DC: Shearwater Books/Island Press.

Creative Arts Educ Ther 2017, 3(2)

Copyright © 2017 Inspirees International