Attachment to Nature: the Roots of Environmentalism

Brendan Hill

Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD

Department of Psychology

University of Edinburgh

May 2003

Text and layout in Word, citations and bibliography in Endnote, questionnaire in

Pagemaker, data transcription in Filemaker, statistical analysis in SPSS, tables in Excel,

figures in Omnigraffle and Photoshop. Body font set in Times New Roman 11/18 point

on an ‘ice’ iBook and ‘angle poise’ iMac running Mac OS X 10.2. Infinite Loop forever!

Printed and bound by University of Edinburgh Reprographics, Edinburgh, Scotland.

ii

Declaration of Authorship

I, the undersigned, hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and that it has not been

submitted for any degree or professional qualification at any other institute of tertiary

education.

Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others is acknowledged

in the text and a full list of references is incorporated.

Brendan Hill

Dated

iii

Dedication

This project has without doubt been the most arduous I have faced, a labour of love of

which I repeatedly despaired, whose conclusion was unimaginable without the tireless

personal support of many friends, colleagues and my parents. I have attempted to

acknowledge their part elsewhere, hoping the end result justifies if only to some small extent

their faith in me. However there are four special people in particular to whom I dedicate it,

for all of whom I was the first of their next generation: my grandparents.

For unrepayable years of honest toil in hard times and good, for unimaginable bravery in

all our names, and for long and full lives of unquestioning service, dedication and love to

your families and to others, this thesis is for:

Annie Bonney

William Bonney

Mary Ellen Hill

Samuel Hill

of St. Helens, Lancashire, England.

iv

Overview and Chapter Summary

The goal of this thesis is to throw light on the origins of our attitudes to nature. Within

this overarching theme, the aims are to enhance the study of environmentalism with a

conceptually coherent and empirically testable psychological basis, to investigate evidence

for developmental influences on environmental attitudes, and to examine the implications of

such a theoretical investigation for practical applications.

Chapter 1: Introduction: Narcissism, agency and the ‘environmental’ ‘crisis’ .......1

This chapter is a personal essay outlining the train of thought which led to the question asked by this

thesis: What are the fundamental influences on our attitudes to nature? Moreover, it suggests why

such attitudes might be important as both an intellectual enquiry and a factor in quality of life. It ends

with a short confessional on the author's own influences.

Chapter 2: Literature review: Evolution and ontogeny of the self in relation to nature..

................................................................................................... 11

Humans interact with their environments in ways ranging from the physiologically evolved to the

culturally complex, out of which 'self' arises. This chapter extends the traditional view of self as

interpersonal to review the evidence for self in relation to the non-human. In particular it examines

the mounting evidence for the importance of nature to the self through the lens of perhaps the most

successful theory of self-in-relationship, Attachment Theory.

Chapter 3: Literature review: Attitudes and behaviours toward nature ................75

Attitudes and behaviours are the subject of much psychological investigation and theorising. This

chapter describes how this work impinges on our thoughts and actions in relation to nature, and how

authors interested in these questions have characterised the variety of attitudes people hold.

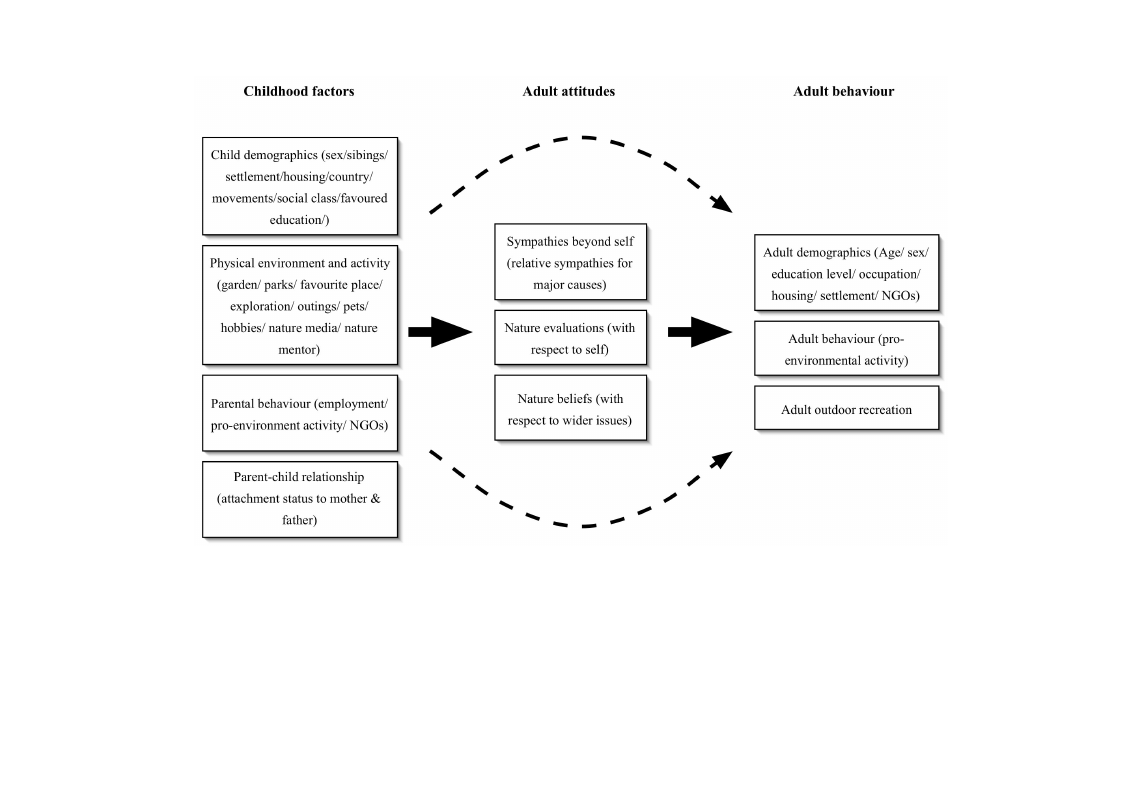

Chapter 4: Questions arising and hypotheses for investigation ............................99

This short chapter summarises the main unanswered questions thrown up by the literature review and

proposes a multifactorial, developmental model for the origination of environmental attitudes and

behaviour. A series of seven testable hypotheses arising from this model are stated.

Chapter 5: Methodology ................................................................................... 103

This chapter systematically considers the possible sources and means of gathering data for relevance

and practicality. It concludes that an extensive questionnaire administered to a wide range of target

groups is most suitable. It explains in detail how the instrument was constructed and how the data

gathering and processing work was carried out.

Chapter 6: Analysis of major hypotheses .......................................................... 155

The three 'major' hypotheses are tested against the data. Statistical conclusions about the significance

of the various relationships are summarised by individual hypothesis.

v

Chapter 7: Analysis of minor hypotheses.......................................................... 201

The four 'minor' hypotheses are tested against the data. Statistical conclusions about the significance

of the various relationships are summarised at the end of the chapter.

Chapter 8: Discussion: Hypotheses and results ................................................. 237

The hypotheses and the results relevant to them are in turn summarised and discussed. Where

patterns arising from multiple results are evident they are identified, and speculations about what this

might imply for the relationship between childhood experience and adult attitudes are made.

Chapter 9: Discussion: Childhood, attachment and environmentalism .............. 259

Discussion moves on from the specific hypotheses to how the larger picture emerging from this

investigation might be characterised. Based on the new empirical evidence, seven specific arguments

are proposed. Finally, a number of novel theoretical proposals are mooted which have particular

relevance for accepted theories of attachment and environmentalism.

Chapter 10: Consequences, applications and further research.......................... 290

This final coda considers some of the wider practical implications of the progressive diminution of

direct contact with nature. A conceptual framework for understanding the deterioration and potential

improvement of human-nature relations is proposed, and a series of possible interventions and further

research questions is identified.

Chapter 11: Appendices.................................................................................. 309

The full questionnaire instrument as deployed and the most important statistical results tables are

reproduced. Supplementary statistical tables are included on a CD-ROM.

Bibliography ................................................................................................ 383

vi

Full Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction: Narcissism, agency and the ‘environmental’ ‘crisis’ .......1

1.1

THE HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIP IS AN URGENT AND NEGLECTED SUBJECT OF

INVESTIGATION.......................................................................................................................................... 1

1.2 IN OUR IGNORANCE WE THREATEN OUR EXISTENCE AND MUCH ELSE ....................................... 3

1.3 PSYCHOLOGY HAS LARGELY IGNORED AND DENIED CONSCIOUSNESS OF NATURE.................... 6

1.4 THE PSYCHOLOGY THAT DOES ACKNOWLEDGE NATURE IS MARGINAL ..................................... 7

1.5 ESTABLISHING A BASIS FOR HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIPS? ................................................ 8

1.6 WHY ME, HERE, NOW .................................................................................................................. 9

Chapter 2: Literature review: Evolution and ontogeny of the self in relation to

nature

................................................................................................... 11

2.1 EVOLUTIONARY AND GENETIC PREDISPOSITIONS TO A DIALOGUE WITH NATURE................... 12

2.2 PHYSICAL TROPISMS: SENSORY AWARENESS OF THE WORLD .................................................. 14

2.2.1 Light.................................................................................................................................. 14

2.2.2 Temperature ..................................................................................................................... 14

2.2.3 Sound ................................................................................................................................ 15

2.2.4 Odour................................................................................................................................ 15

2.3 LEARNING AND INSTINCTS ........................................................................................................ 16

2.3.1 Encountering the world: How animals learn to perceive .............................................. 16

2.3.2 Mammalian consciousness .............................................................................................. 18

2.3.2.1 Attachment needs I: Food and protection ..................................................................................19

2.3.2.2 Attachment needs II: Knowledge of a home environment and the beginnings of culture.......20

2.3.3 Humans and knowing about a place to live .................................................................... 20

2.3.3.1 We like natural landscapes: Why?..............................................................................................21

2.3.3.1.1 Complexity and interest.......................................................................................................22

2.3.3.1.2 Savannah hypothesis............................................................................................................22

2.3.3.1.3 Prospect and refuge..............................................................................................................22

2.3.3.2 Historical trends modify the sense of place ...............................................................................23

2.3.3.3 Iconic symbolism: Shared places ...............................................................................................24

2.3.3.4 Gender differences in sense of place..........................................................................................24

2.3.4 The Biophilia Hypothesis and an ‘environment recognition device’ in animal minds . 25

2.4 IDEAS OF THE SELF..................................................................................................................... 28

2.4.1 Self consciousness: Knowing action ............................................................................... 28

2.4.2 How does the human self arise?...................................................................................... 30

2.4.3 The instinctual ‘need’ for others in social species ......................................................... 30

2.4.4 Self in relation, or intersubjectivity................................................................................. 31

2.4.5 Staged transformations.................................................................................................... 33

2.5 ATTACHMENT THEORY.............................................................................................................. 35

2.5.1 Origins in ethology and psychoanalysis ......................................................................... 35

2.5.2 Experimental confirmation.............................................................................................. 36

2.5.3 Refinements ...................................................................................................................... 37

2.5.3.1 Criticisms of attachment theory..................................................................................................37

2.5.3.2 Infants are participants, reacting actively and ‘logically’ to experience ..................................37

2.5.3.3 Biological motherhood is not essential ......................................................................................38

2.5.3.4 Embodiment and touch ...............................................................................................................38

2.5.3.5 Models of self and other .............................................................................................................39

vii

2.5.3.6 Multiple psychologies: The same constructs? ...........................................................................41

2.5.4 Extensions ........................................................................................................................ 42

2.5.4.1 Human .........................................................................................................................................42

2.5.4.1.1 Intrinsic influences ..............................................................................................................42

2.5.4.1.2 The first dyad.......................................................................................................................43

2.5.4.1.3 The next dyad, and the first triad ........................................................................................44

2.5.4.1.4 Wider and lasting effects.....................................................................................................45

2.5.4.1.5 One attachment or many?....................................................................................................46

2.5.4.2 Attachment to all sentient others? ..............................................................................................47

2.5.4.2.1 Interspecies relationships are normal..................................................................................48

2.5.4.2.2 ‘Companion animals’ engender health ...............................................................................52

2.5.4.2.3 Animal attachment and its consequenses ...........................................................................54

2.5.4.2.4 ‘Family ecology’ and the community.................................................................................57

2.5.4.3 Attachment and the non-sentient environment ..........................................................................59

2.5.4.3.1 Attachment and lower animals............................................................................................59

2.5.4.3.2 Attachment and plants .........................................................................................................60

2.5.4.3.3 Attachment and inanimate objects......................................................................................61

2.5.4.3.4 Attachment and the built environment ...............................................................................62

2.5.4.3.5 Attachment and place ..........................................................................................................64

2.5.4.3.6 Climate, community, ‘The Planet’ and ‘God’....................................................................69

2.5.4.4 Non-attachment...........................................................................................................................72

2.6 HOLISTIC THEORIES: ‘EVER-WIDENING SPHERES OF MEANING AND PARTICIPATION’ ............ 72

Chapter 3: Literature review: Attitudes and behaviours toward nature ................ 75

3.1 EXPERIENCE, ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIOUR IN GENERAL.......................................................... 75

3.1.1 What are attitudes and how do they arise? .................................................................... 75

3.1.2 Do attitudes predict behaviour?...................................................................................... 77

3.1.3 Can experience predict behaviour, regardless of attitudes? ......................................... 79

3.2 ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIOURS TOWARD NATURE..................................................................... 80

3.2.1 Conceptions and models.................................................................................................. 80

3.2.2 Demographics and personality ....................................................................................... 85

3.2.3 Historical and cultural factors........................................................................................ 88

3.2.4 Deliberate change: environmental education ................................................................ 92

3.2.5 ‘Ordinary ecstasy’: outdoor recreation.......................................................................... 95

Chapter 4: Questions arising and hypotheses for investigation............................ 99

4.1 UNANSWERED QUESTIONS CONCERNING ATTACHMENT AND ENVIRONMENTALISM ............... 99

4.2 MAJOR HYPOTHESES ............................................................................................................... 101

4.3 MINOR HYPOTHESES................................................................................................................ 102

4.4 WIDER UTILITY OF SUCH AN INVESTIGATION ......................................................................... 102

Chapter 5: Methodology................................................................................... 103

5.1 REVIEW OF METHODOLOGICAL ALTERNATIVES...................................................................... 103

5.1.1 What information is required? ...................................................................................... 104

5.1.2 Kinds of cohorts............................................................................................................. 106

5.1.3 Types of data gathering ................................................................................................. 108

5.2 THE METHODOLOGY ADOPTED................................................................................................ 112

5.2.1 Participants.................................................................................................................... 113

5.2.1.1 Sample groups...........................................................................................................................113

5.2.1.2 Administration and responses...................................................................................................114

5.2.1.3 Sample demographics ...............................................................................................................117

5.2.2 Materials ........................................................................................................................ 119

5.2.2.1 Full list of variables ..................................................................................................................121

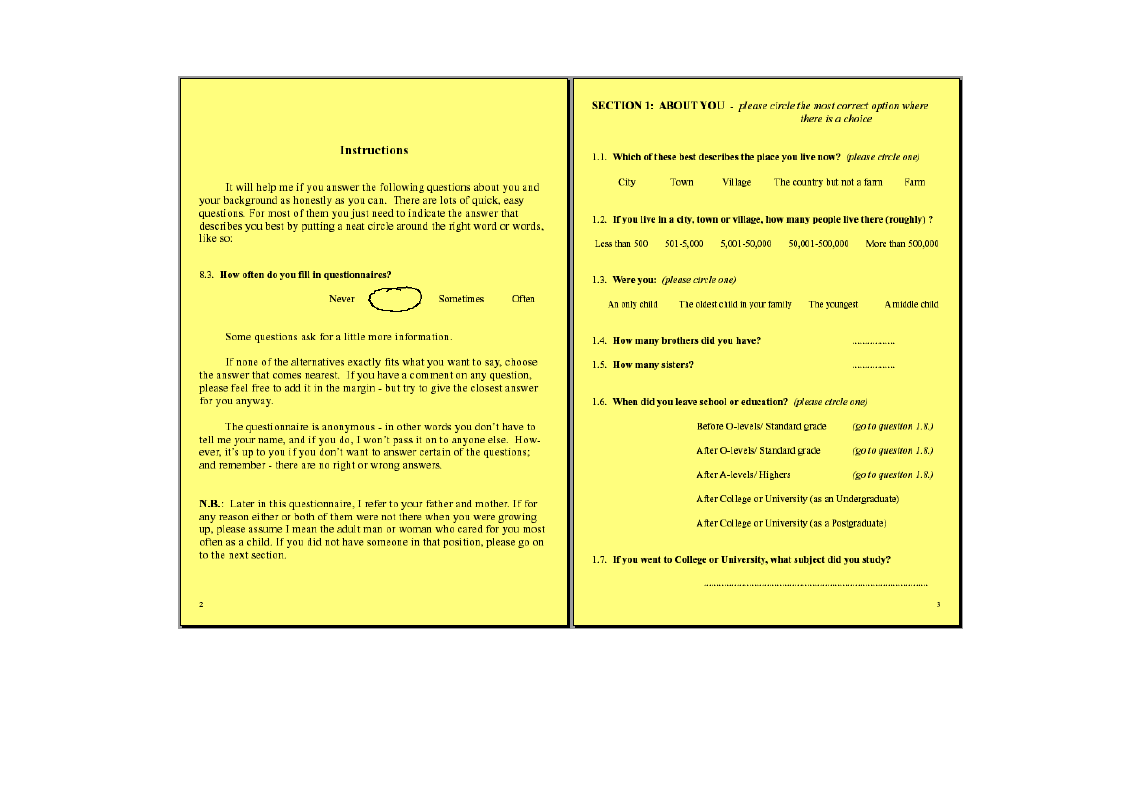

5.2.2.2 Development of the questionnaire............................................................................................124

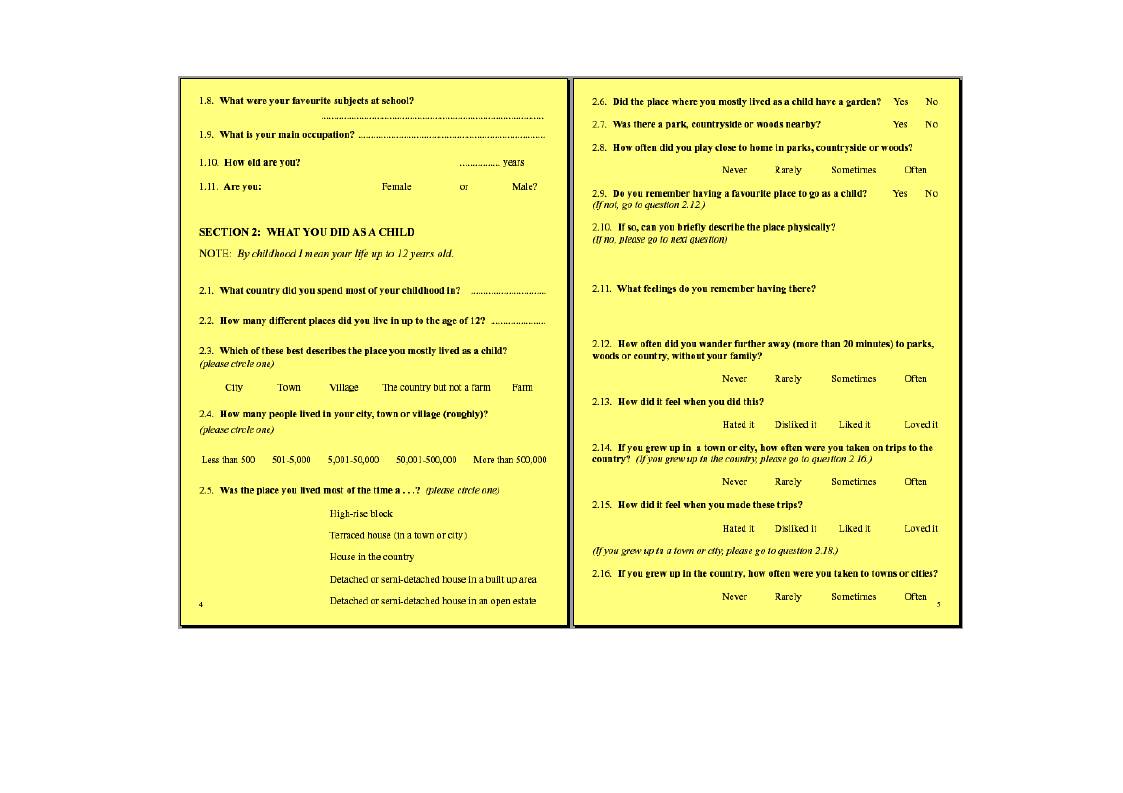

5.2.2.2.1 Section 1: demographics ...................................................................................................124

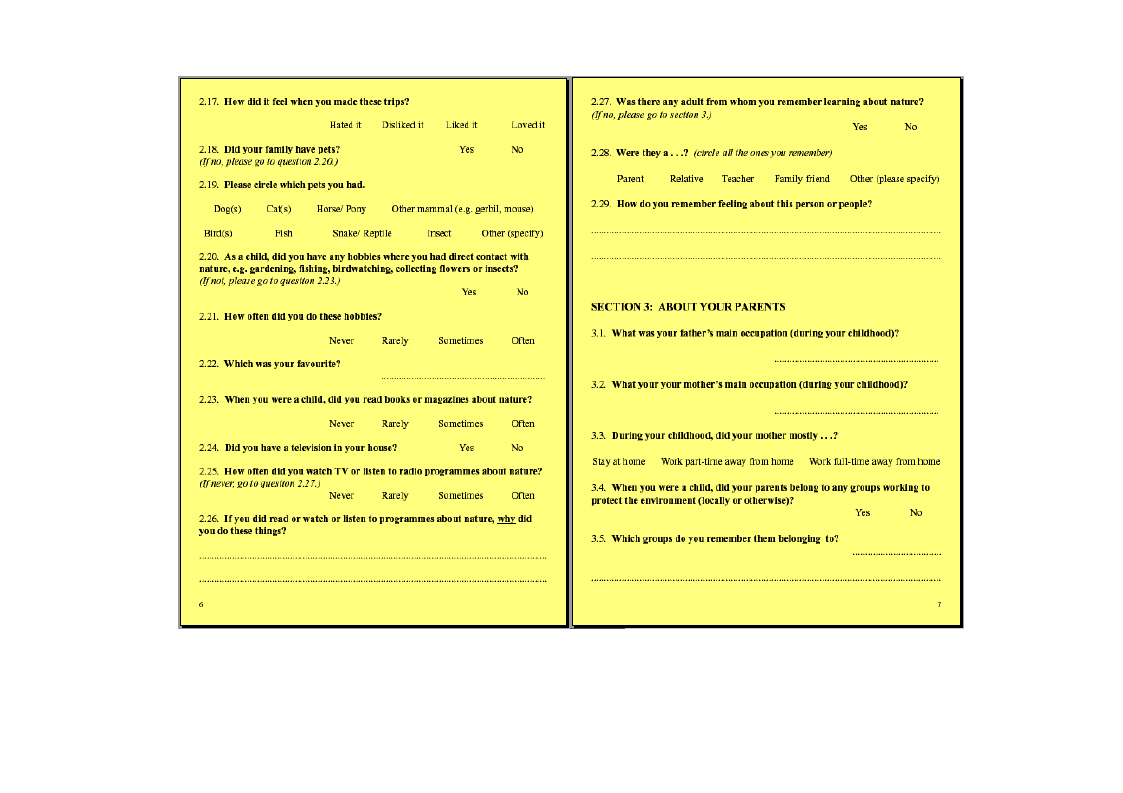

5.2.2.2.2 Section 2: childhood habitation/activities.........................................................................125

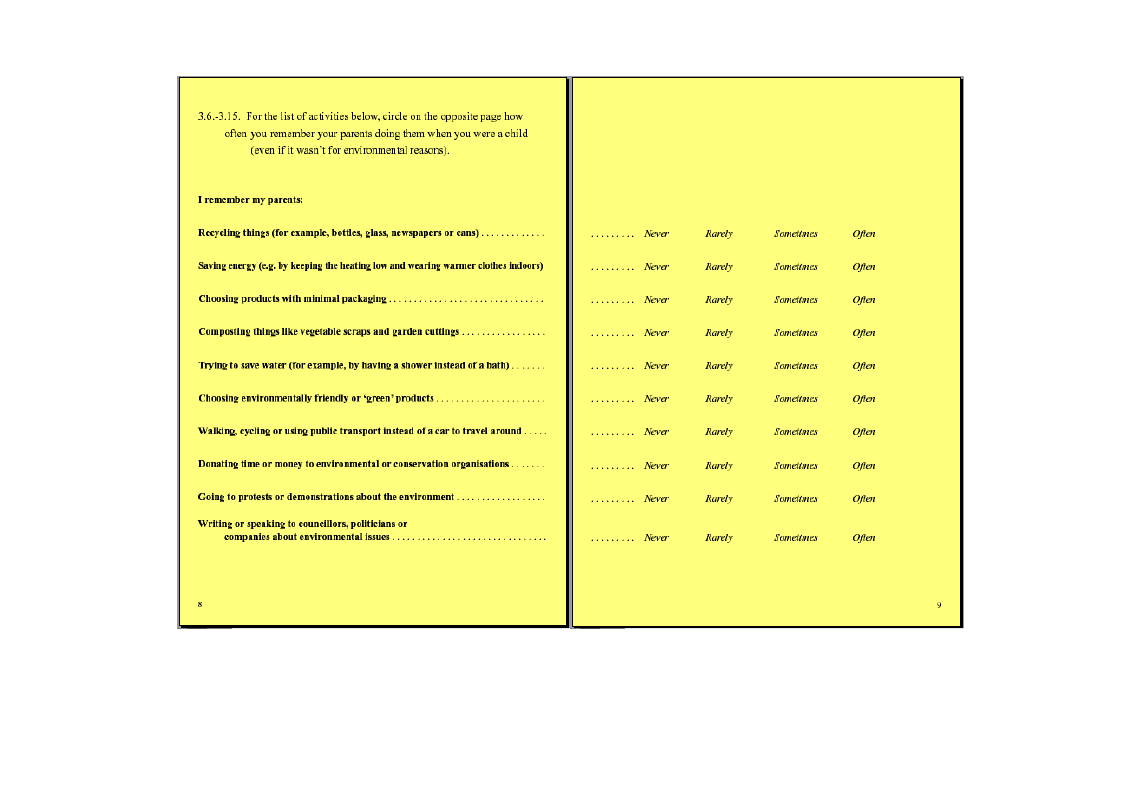

5.2.2.2.3 Section 3: parental work and environmental actions .......................................................126

5.2.2.2.4 Section 4: charitable giving...............................................................................................128

viii

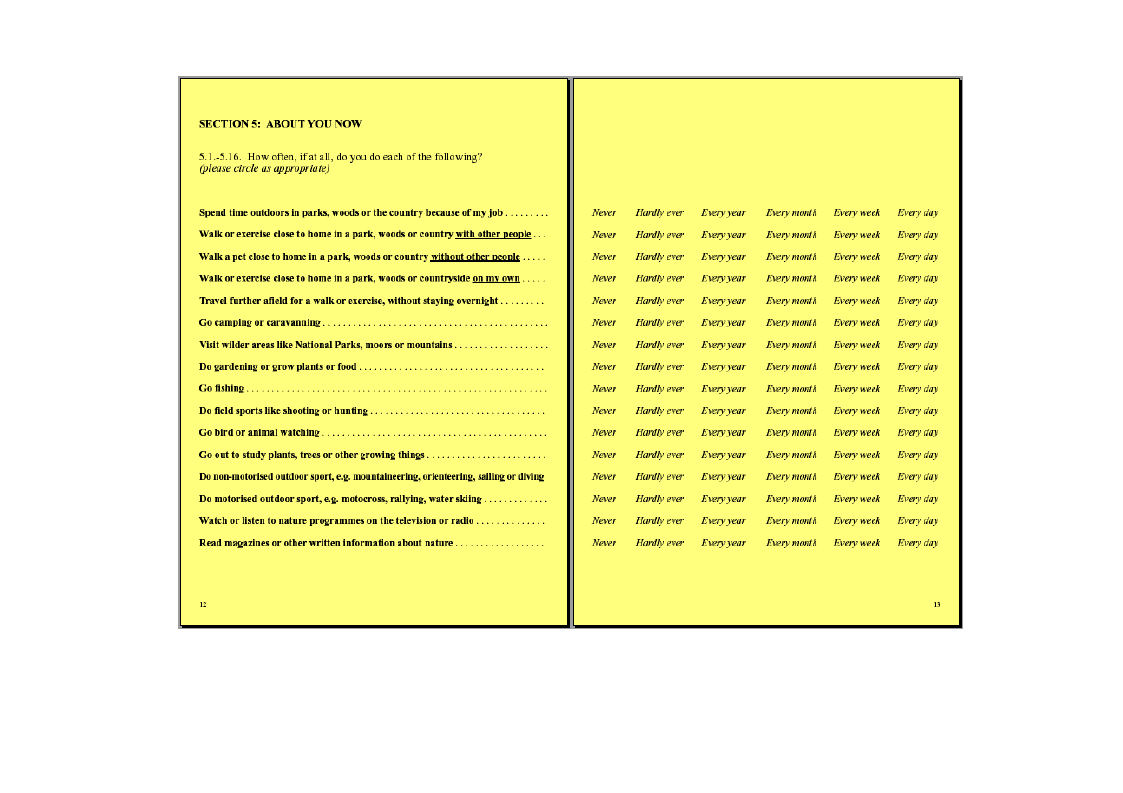

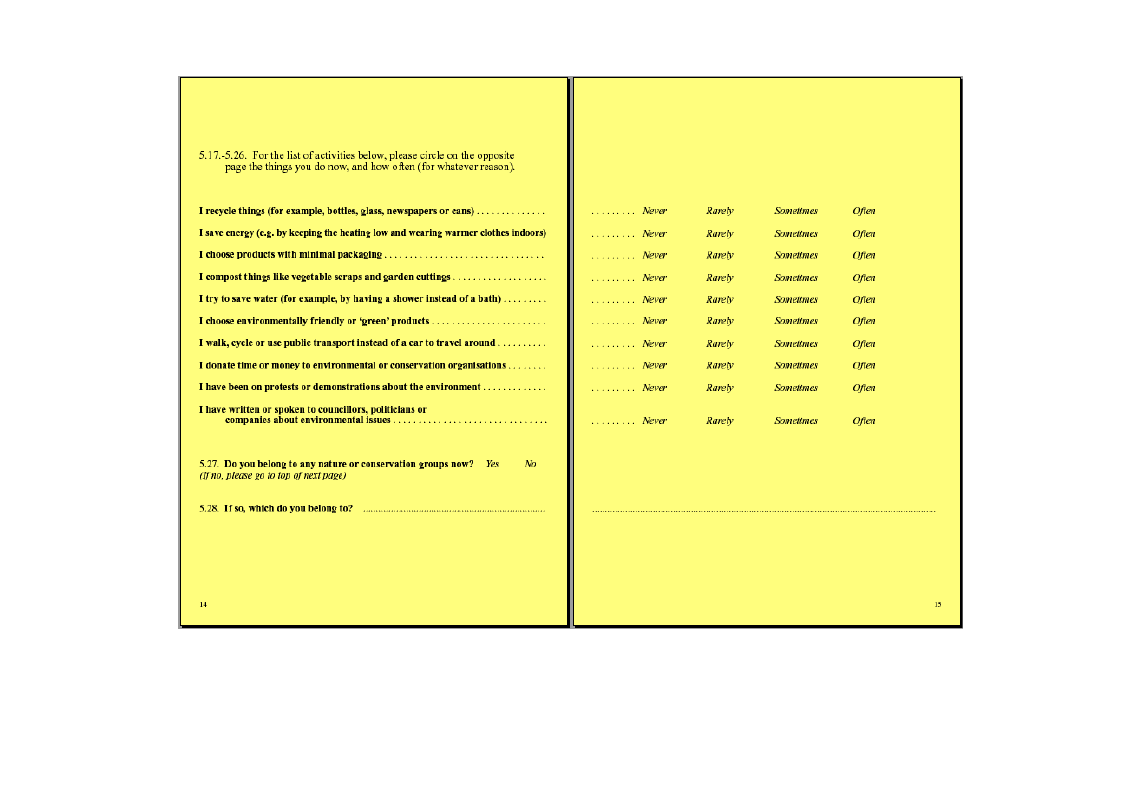

5.2.2.2.5 Section 5, first half: present environmental activities ......................................................128

5.2.2.2.6 Section 5, second half: present environmental actions ....................................................129

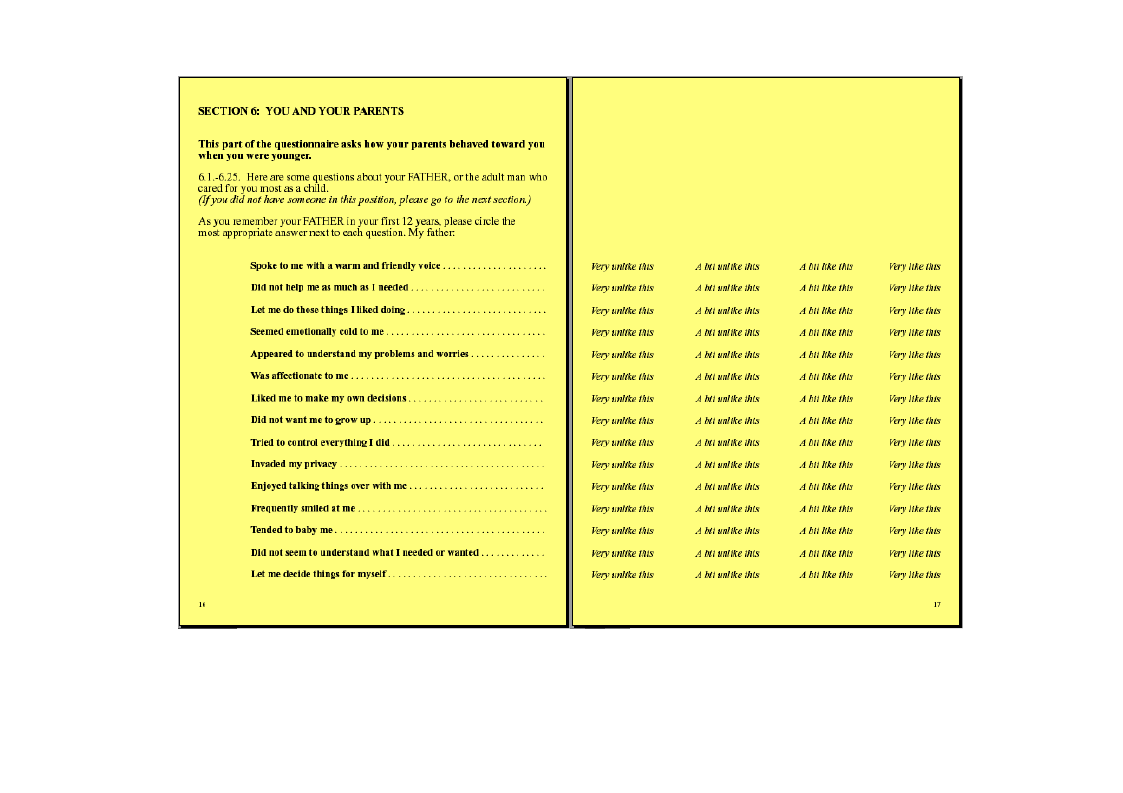

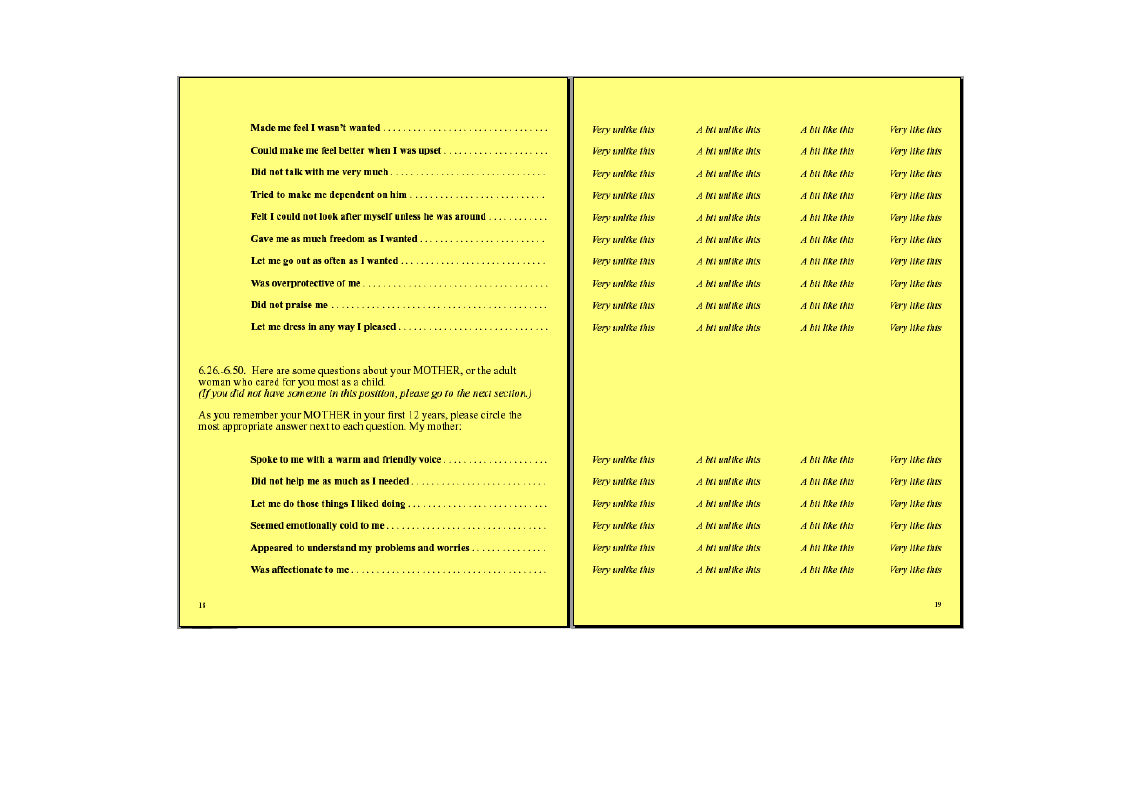

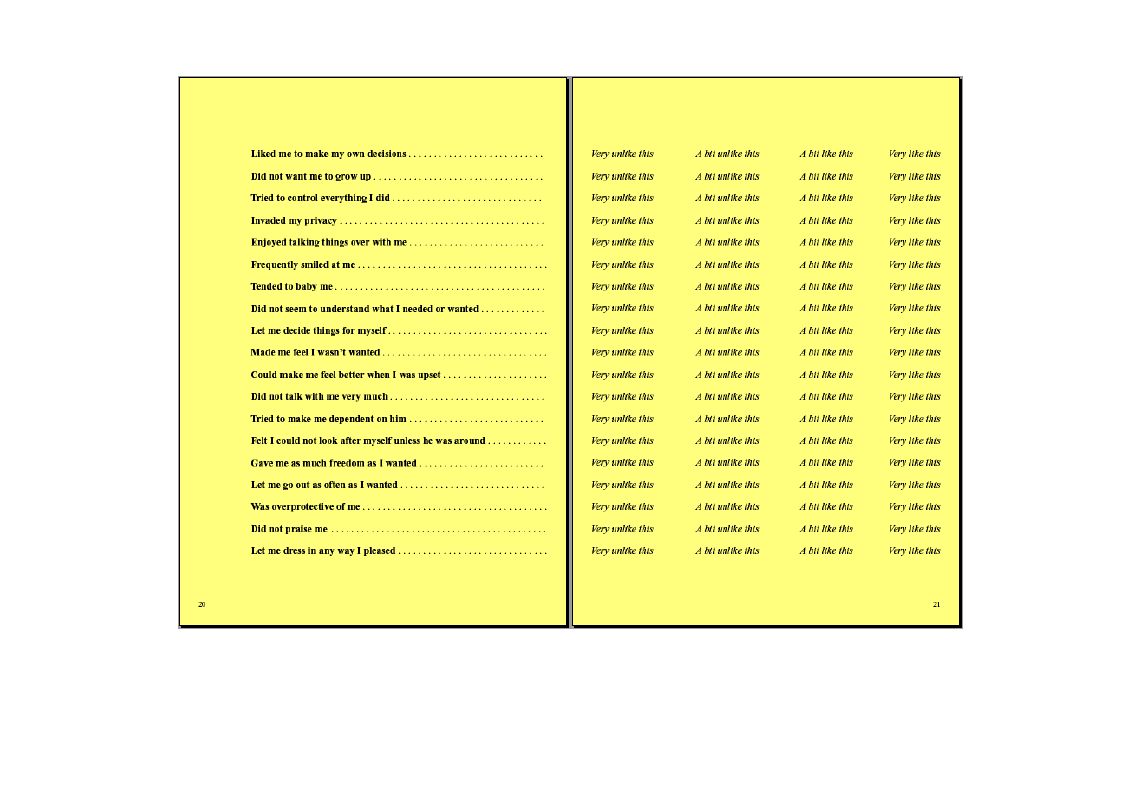

5.2.2.2.7 Section 6: adult attachment ...............................................................................................129

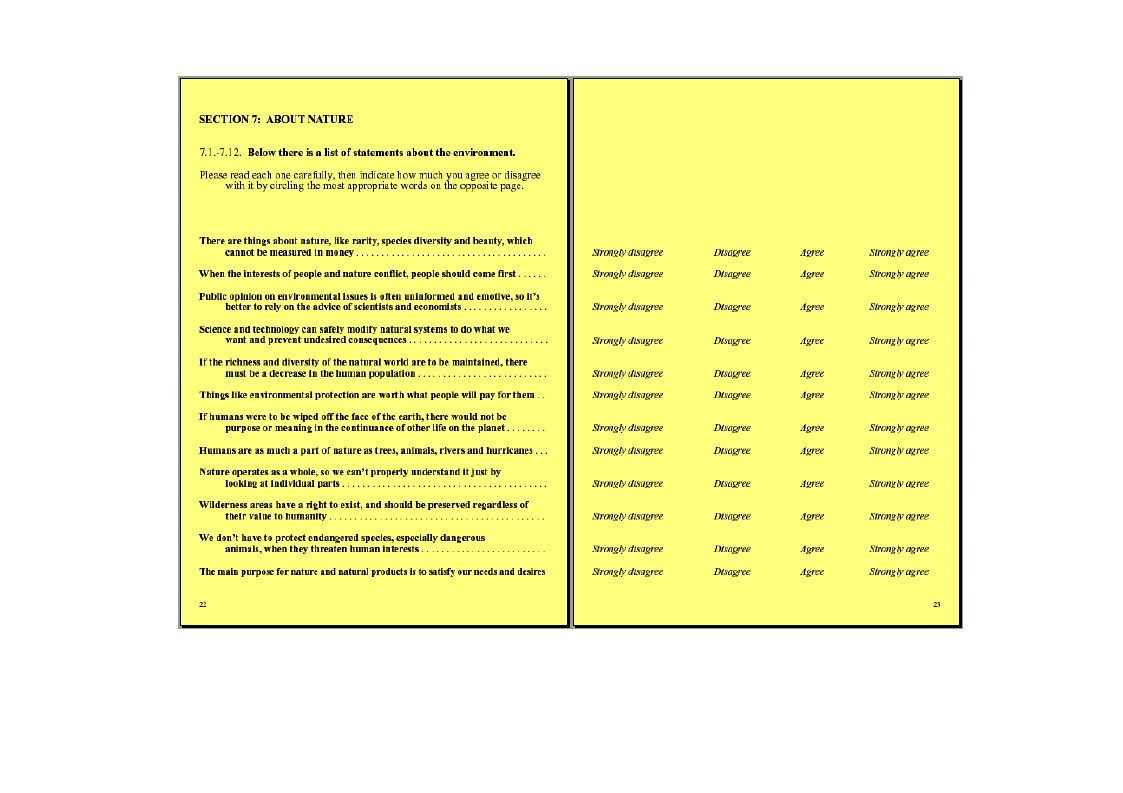

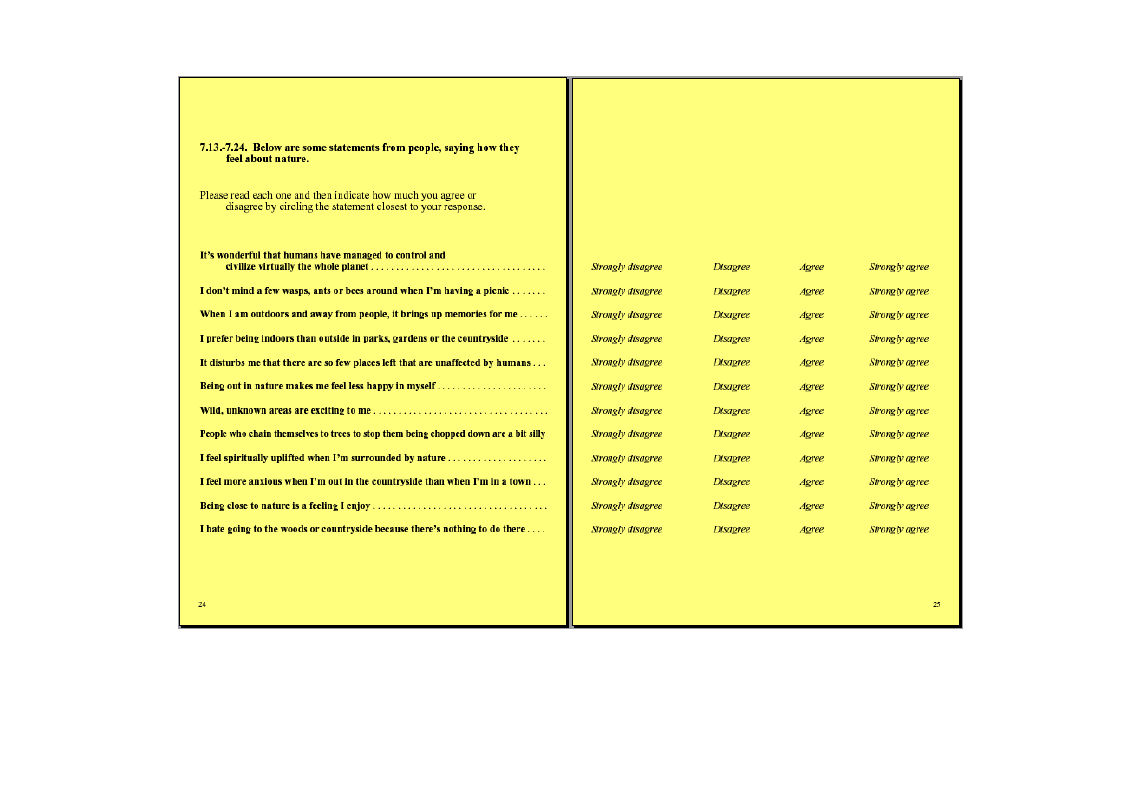

5.2.2.2.8 Section 7: environmental attitudes....................................................................................132

5.2.3 Procedures ..................................................................................................................... 136

5.2.3.1 Piloting.......................................................................................................................................136

5.2.3.2 Post-survey respondent feedback .............................................................................................139

5.2.3.3 Data transcription ......................................................................................................................140

5.2.3.4 Preparation of the data ..............................................................................................................141

5.2.3.4.1 Section 1: demographics....................................................................................................141

5.2.3.4.2 Section 2: childhood habitation/activities.........................................................................142

5.2.3.4.3 Section 3: parental work and environmental (eco-) actions.............................................144

5.2.3.4.4 Section 4: charitable giving...............................................................................................145

5.2.3.4.5 Section 5, first half: present environmental (eco-)activities ............................................147

5.2.3.4.6 Section 5, second half: present environmental actions ....................................................148

5.2.3.4.7 Section 6: adult attachment ...............................................................................................150

5.2.3.4.8 Section 7, first half: attitudes and beliefs towards nature ................................................150

5.2.3.4.9 Section 7, second half: emotional responses to nature.....................................................152

Chapter 6: Analysis of major hypotheses .......................................................... 155

6.1

HYPOTHESIS ONE: ADULT ATTITUDES TO NATURE ARE RELATED TO PARENTAL ATTACHMENT

STATUS 155

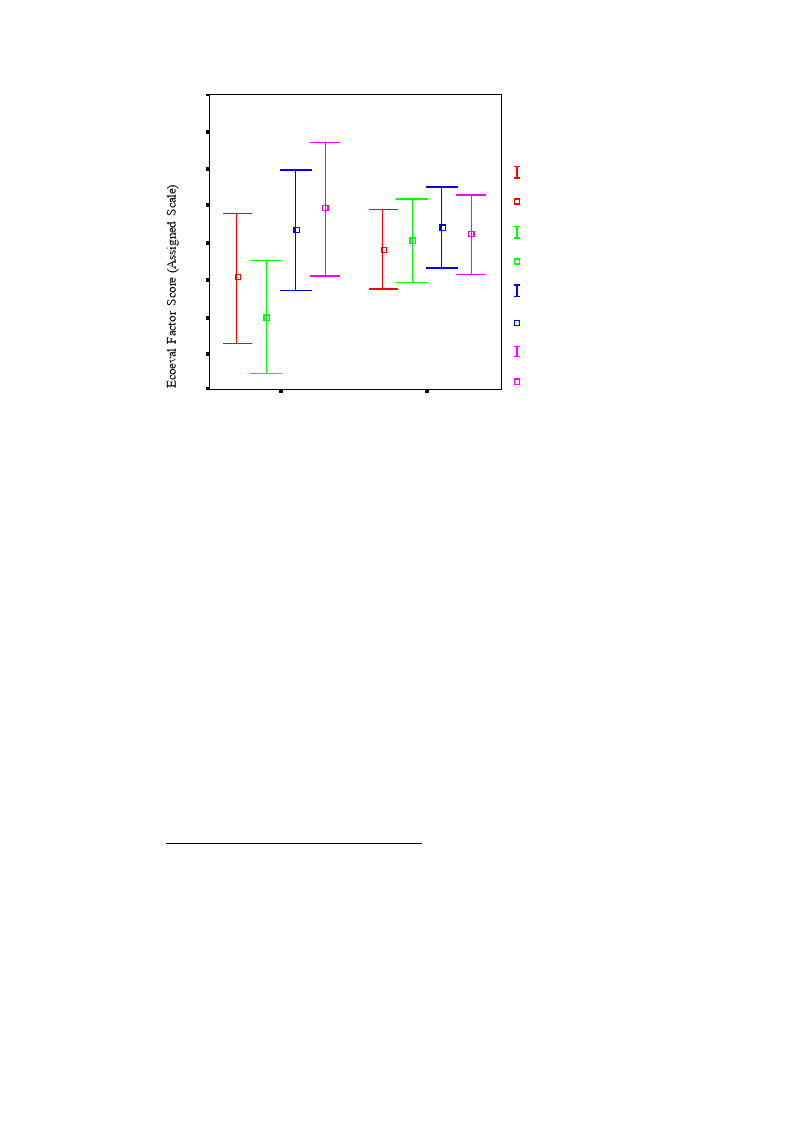

6.1.1 Paternal attachment status and ecoevaluation............................................................. 155

6.1.2 Maternal attachment status and ecoevaluation............................................................ 156

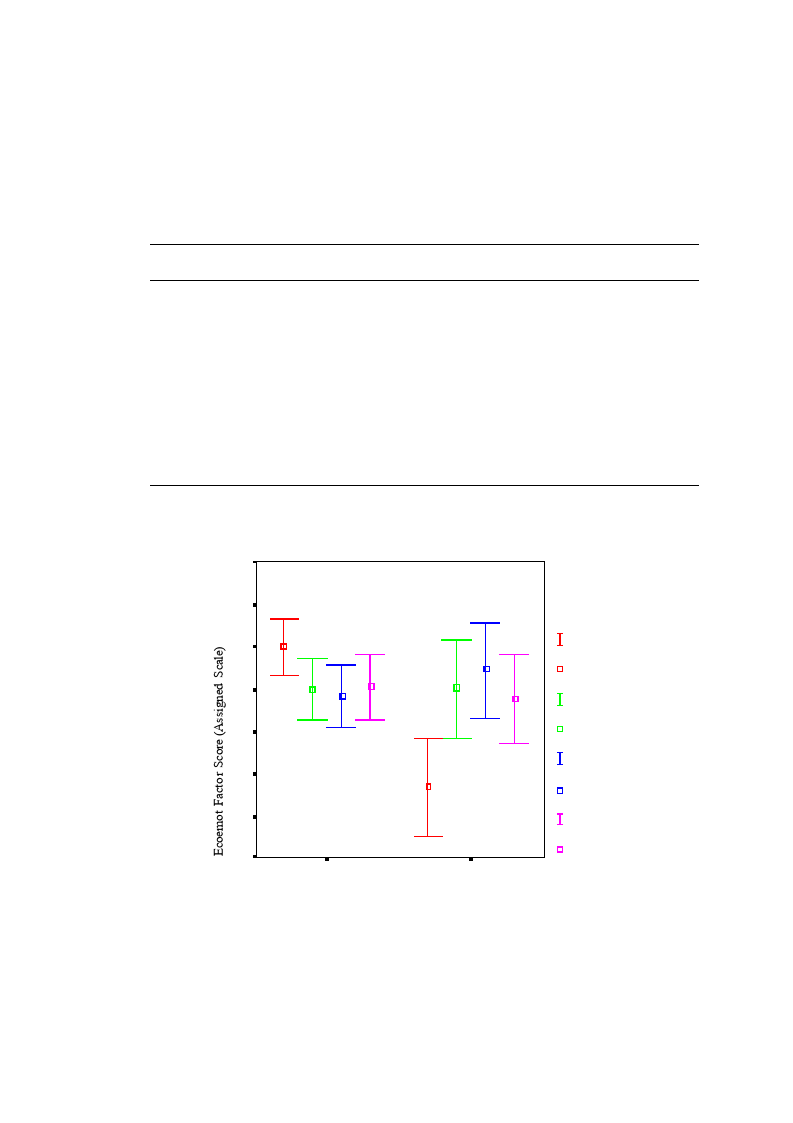

6.1.3 Paternal attachment status and ecoemotionality.......................................................... 157

6.1.4 Maternal attachment status and ecoemotionality......................................................... 158

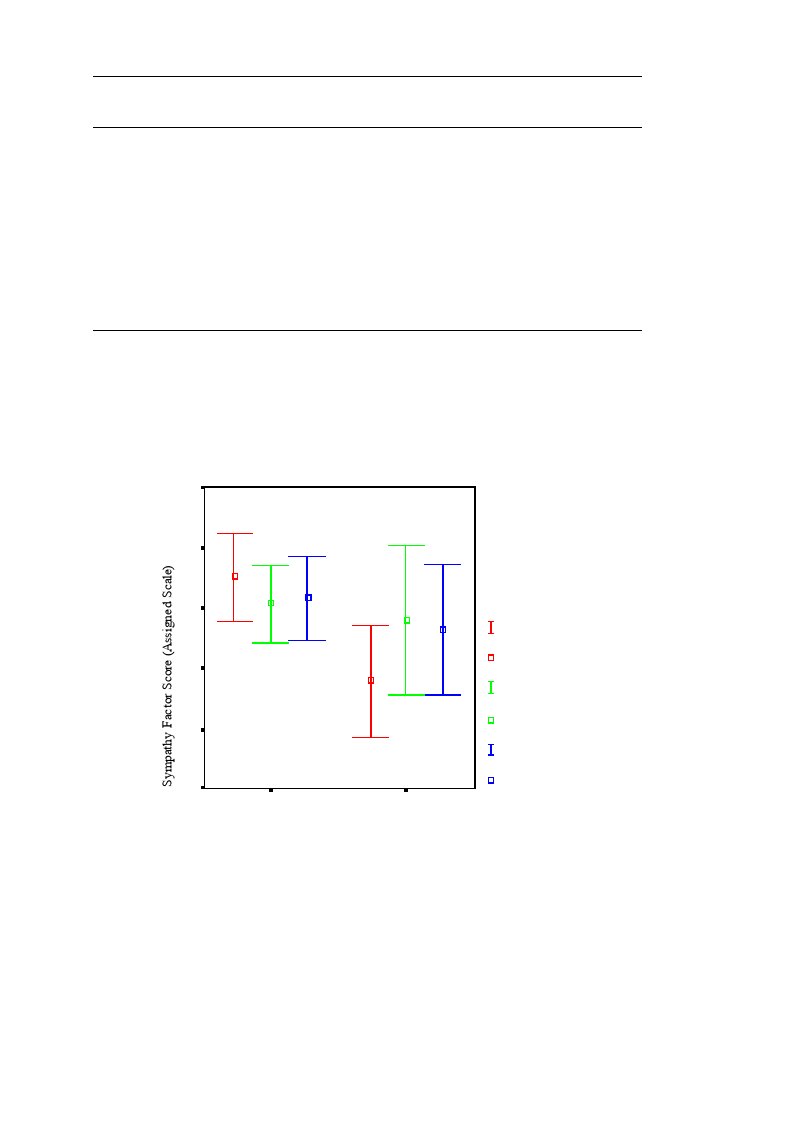

6.1.5 Paternal attachment status and relative sympathies .................................................... 159

6.1.6 Maternal attachment status and relative sympathies ................................................... 160

6.1.7 Attachment and exploring nature.................................................................................. 161

6.1.8 Attachment versus other selected attitude and behaviour measures ........................... 163

6.1.8.1 Paternal attachment status.........................................................................................................164

6.1.8.2 Maternal attachment status .......................................................................................................164

6.1.9 Other notable results ..................................................................................................... 164

6.1.9.1 Maternal care and sample sub-group........................................................................................164

6.1.10 Summary of findings ...................................................................................................... 165

6.1.10.1

Paternal attachment ..............................................................................................................165

6.1.10.2

Maternal attachment.............................................................................................................166

6.2

HYPOTHESIS TWO: ADULT ATTITUDES TO NATURE ARE AFFECTED BY DIRECT CONTACT WITH

NATURE AS A CHILD............................................................................................................................... 167

6.2.1 Accessible nature and attitudes to nature..................................................................... 167

6.2.1.1 Accessible nature and ecoevaluation........................................................................................167

6.2.1.2 Accessible nature and ecoemotionality ....................................................................................168

6.2.1.3 Accessible nature and relative sympathies...............................................................................169

6.2.1.4 Accessible nature and education...............................................................................................171

6.2.1.5 Accessible nature and sample sub-groups................................................................................171

6.2.2 Exploring nature and attitudes to nature...................................................................... 171

6.2.2.1 Play and ecoevaluation..............................................................................................................171

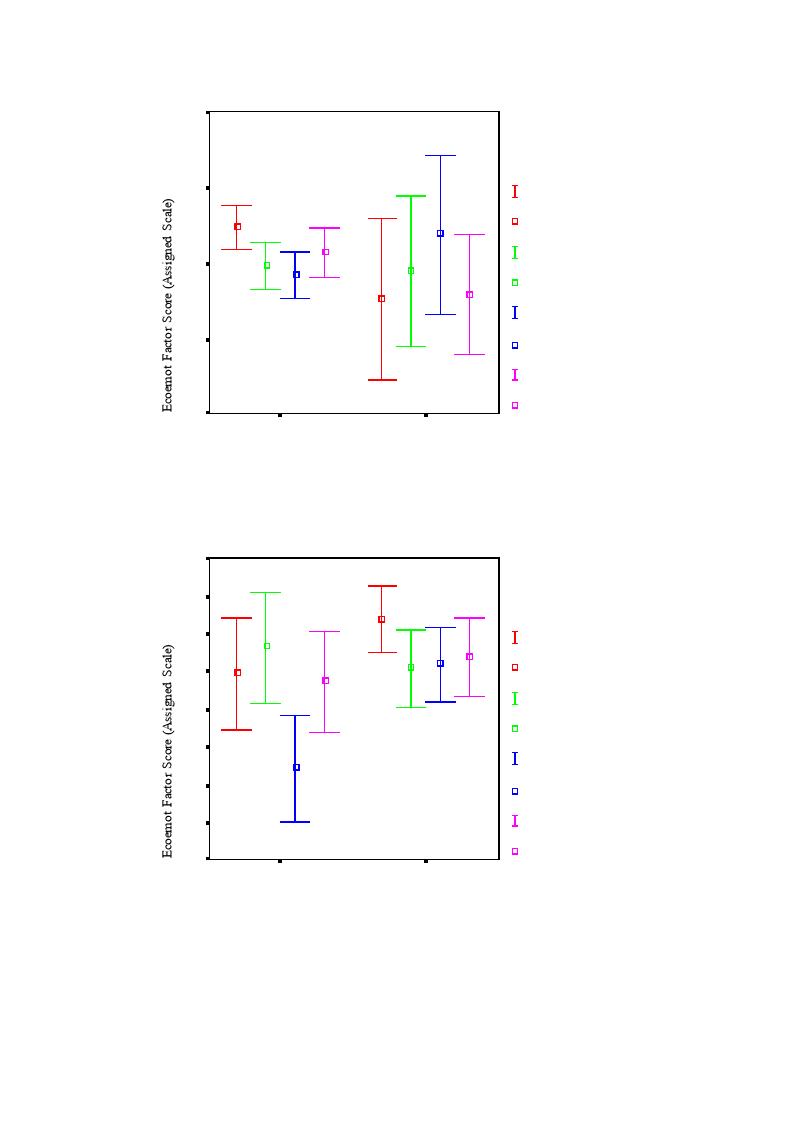

6.2.2.2 Play and ecoemotionality..........................................................................................................172

6.2.2.3 Play and relative sympathies.....................................................................................................174

6.2.2.4 Wander and ecoevaluation........................................................................................................174

6.2.2.5 Wander and ecoemotionality ....................................................................................................175

6.2.2.6 Wander and relative sympathies...............................................................................................176

6.2.2.7 Favourite place and ecoevaluation ...........................................................................................177

6.2.2.8 Favourite place and ecoemotionality........................................................................................180

6.2.2.9 Favourite place and relative sympathies ..................................................................................183

6.2.2.10

Exploring nature and place ..................................................................................................185

6.2.2.11

Exploring nature and age .....................................................................................................187

6.2.3 Summary of findings ...................................................................................................... 188

6.3

HYPOTHESIS THREE: ADULT ATTITUDES TO NATURE ARE AFFECTED BY PARENTAL

BEHAVIOUR............................................................................................................................................ 191

6.3.1 Parental ecoactivity and attitudes to nature................................................................. 191

ix

6.3.1.1

6.3.1.2

6.3.1.3

6.3.1.4

6.3.2

6.3.2.1

6.3.2.2

6.3.2.3

6.3.2.4

6.3.3

6.3.3.1

6.3.3.2

6.3.3.3

6.3.3.4

6.3.4

Parental ecoactivity and ecoevaluation ....................................................................................191

Parental ecoactivity and ecoemotionality ................................................................................192

Parental ecoactivity and relative sympathies ...........................................................................193

Other parental ecoactivity-related findings..............................................................................193

Nature mentoring and attitudes to nature..................................................................... 194

Nature mentor and ecoevaluation.............................................................................................194

Nature mentor and ecoemotionality .........................................................................................195

Nature mentor and relative sympathies....................................................................................195

Other nature mentor-related findings .......................................................................................196

Ecoparenting and attitudes to nature ........................................................................... 197

Ecoparenting and ecoevaluation...............................................................................................197

Ecoparenting and ecoemotionality ...........................................................................................197

Ecoparenting and relative sympathies......................................................................................198

Other ecoparenting-related findings.........................................................................................199

Summary of findings ...................................................................................................... 200

Chapter 7: Analysis of minor hypotheses.......................................................... 201

7.1

HYPOTHESIS FOUR: ADULT ATTITUDES TO NATURE ARE AFFECTED BY INDIRECT AND

VICARIOUS CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCE OF NATURE ................................................................................ 201

7.1.1 Prevalence of indirect and vicarious nature experience.............................................. 201

7.1.2 Nature hobbies and attitudes to nature......................................................................... 202

7.1.2.1 Nature hobbies and ecoevaluation............................................................................................203

7.1.2.2 Nature hobbies and ecoemotionality........................................................................................203

7.1.2.3 Nature hobbies and relative sympathies...................................................................................204

7.1.3 Nature media and attitudes to nature ........................................................................... 206

7.1.3.1 Nature media and ecoevaluation ..............................................................................................206

7.1.3.2 Nature media and ecoemotionality...........................................................................................207

7.1.3.3 Nature media and relative sympathies .....................................................................................208

7.1.4 Nature child and attitudes to nature ............................................................................. 208

7.1.4.1 Nature child and ecoevaluation ................................................................................................208

7.1.4.2 Nature child and ecoemotionality.............................................................................................209

7.1.4.3 Nature child and relative sympathies .......................................................................................210

7.2

HYPOTHESIS FIVE: ADULT ATTITUDES TO NATURE ARE AFFECTED BY THE SIZE AND NATURE

OF THE ANIMAL AND HUMAN ‘MENAGERIE’ THE CHILD GROWS UP IN................................................. 210

7.2.1 Pets and attitudes to nature........................................................................................... 210

7.2.1.1 Pets and ecoevaluation..............................................................................................................211

7.2.1.2 Pets and ecoemotionality ..........................................................................................................212

7.2.1.3 Pets and relative sympathies.....................................................................................................214

7.2.1.4 Other pet-related findings.........................................................................................................215

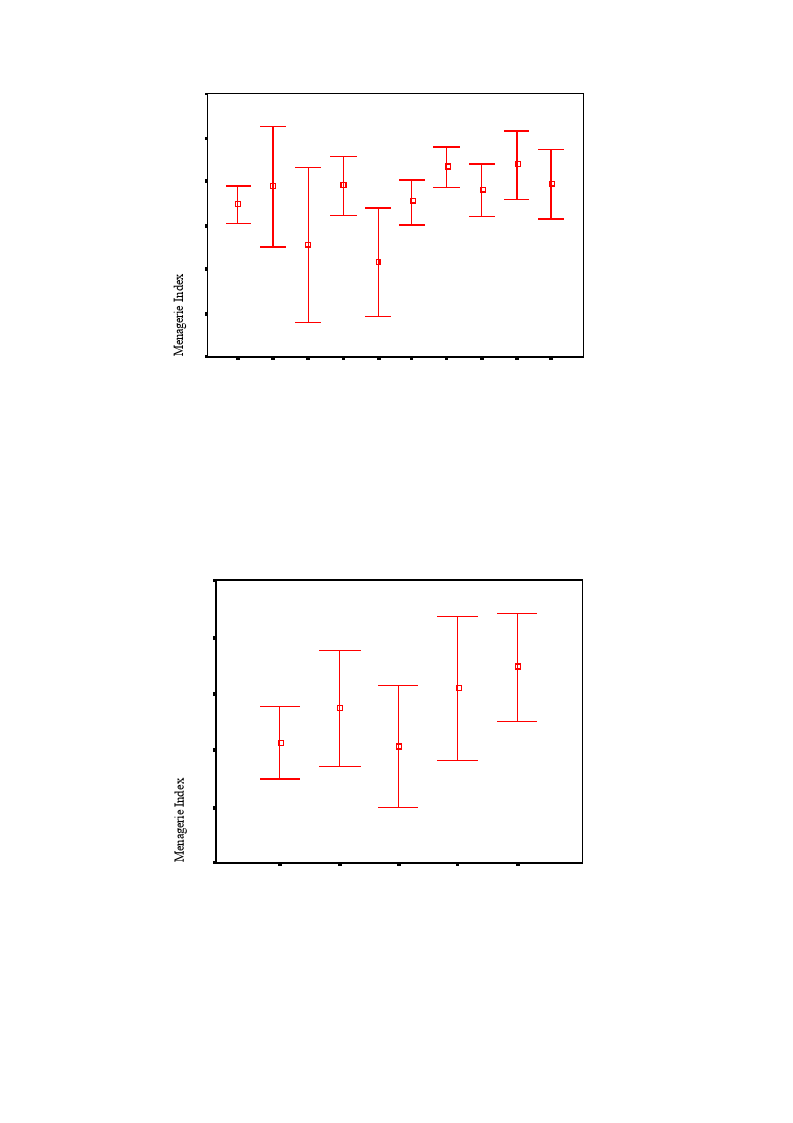

7.2.2 The ‘menagerie’ and attitudes to nature....................................................................... 217

7.2.2.1 Menagerie and ecoevaluation ...................................................................................................217

7.2.2.2 Menagerie and ecoemotionality ...............................................................................................218

7.2.2.3 Menagerie and relative sympathies ..........................................................................................219

7.2.2.4 Miscellaneous menagerie-related findings ..............................................................................219

7.3

HYPOTHESIS SIX: ADULT ATTITUDES TO NATURE ARE AFFECTED BY SOCIAL FACTORS ....... 221

7.3.1 Child movements and attitudes to nature ..................................................................... 221

7.3.1.1 Child movements and ecoevaluation........................................................................................221

7.3.1.2 Child movements and ecoemotionality....................................................................................222

7.3.1.3 Child movements and relative sympathies ..............................................................................223

7.3.1.4 Other social factors-related findings ........................................................................................223

7.3.2 Social class and attitudes to nature .............................................................................. 223

7.3.2.1 Social class and ecoevaluation .................................................................................................224

7.3.2.2 Social class and ecoemotionality..............................................................................................224

7.3.2.3 Social class and relative sympathies ........................................................................................225

7.3.3 Education and attitudes to nature................................................................................. 227

7.3.3.1 Education and ecoevaluation....................................................................................................227

7.3.3.2 Education and ecoemotionality ................................................................................................227

7.3.3.3 Education and relative sympathies...........................................................................................228

7.3.4 Adult home and attitudes to nature ............................................................................... 229

7.3.4.1 Adult home and ecoevaluation .................................................................................................229

7.3.4.2 Adult home and ecoemotionality .............................................................................................229

x

7.3.4.3 Adult home and relative sympathies ........................................................................................230

7.4

HYPOTHESIS SEVEN: ADULT BEHAVIOUR TOWARD NATURE IS SHAPED BY CHILDHOOD

FACTORS, INDEPENDENTLY OF ADULT ATTITUDES............................................................................... 231

7.5 SUMMARIES OF FINDINGS ........................................................................................................ 232

7.5.1 Hypothesis FOUR .......................................................................................................... 232

7.5.2 Hypothesis FIVE ............................................................................................................ 232

7.5.3 Hypothesis SIX ............................................................................................................... 233

7.5.4 Hypothesis SEVEN......................................................................................................... 233

Chapter 8: Discussion: Hypotheses and results ................................................. 235

8.1 HYPOTHESIS ONE SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION....................................................................... 235

8.1.1 Summary of main findings ............................................................................................. 235

8.1.2 Discussion ...................................................................................................................... 236

8.2 HYPOTHESIS TWO SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION ...................................................................... 240

8.2.1 Summary of main findings ............................................................................................. 240

8.2.2 Discussion ...................................................................................................................... 240

8.2.2.1 ‘Given’ nature............................................................................................................................241

8.2.2.2 Play and exploration choices ....................................................................................................244

8.3 HYPOTHESIS THREE SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION ................................................................... 246

8.3.1 Summary of main findings ............................................................................................. 246

8.3.2 Discussion ...................................................................................................................... 247

8.4 HYPOTHESIS FOUR SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION..................................................................... 248

8.4.1 Summary of main findings ............................................................................................. 248

8.4.2 Discussion ...................................................................................................................... 249

8.5 HYPOTHESIS FIVE SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION ...................................................................... 251

8.5.3 Summary of main findings ............................................................................................. 251

8.5.4 Discussion ...................................................................................................................... 251

8.5.4.1 Animal ‘siblings’.......................................................................................................................251

8.5.4.2 Siblings ......................................................................................................................................253

8.6 HYPOTHESIS SIX SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION ........................................................................ 253

8.6.1 Summary of main findings ............................................................................................. 253

8.6.2 Discussion ...................................................................................................................... 254

Chapter 9: Discussion: Childhood, attachment and environmentalism............... 259

9.1 PARENTAL ATTACHMENT INFLUENCES ATTITUDES TO THE NON-HUMAN.............................. 259

9.2 ATTACHMENT TO THE NON-HUMAN IS A SEPARATE RELATIONSHIP....................................... 261

9.3 HUMANS NORMALLY DOMINATE SOCIALIZATION, FOLLOWED BY ANIMALS ......................... 264

9.4

EXPLORATION ENGENDERS NATURE SECURITY, ASSUMING FREEDOM FROM CONSTRAINT .. 265

9.5

PARENTS CAN CONSTRAIN PLAY AND WANDERING, OR FACILITATE NATURE SECURITY....... 268

9.6 VICARIOUS NATURE SATISFIES SOME NEEDS, BUT MAY NOT REPLACE REALITY ................... 269

9.7

POOR ATTACHMENT CAN LEAD TO DISPLACEMENT OF NEEDS ONTO THE NON-HUMAN ........ 270

9.8

THEORIES OF ATTACHMENT AND ENVIRONMENTALISM MAY REQUIRE MODIFICATION ........ 271

9.8.1 Beyond mother-infant attachment ................................................................................. 273

9.8.2 Complexity of attachment .............................................................................................. 274

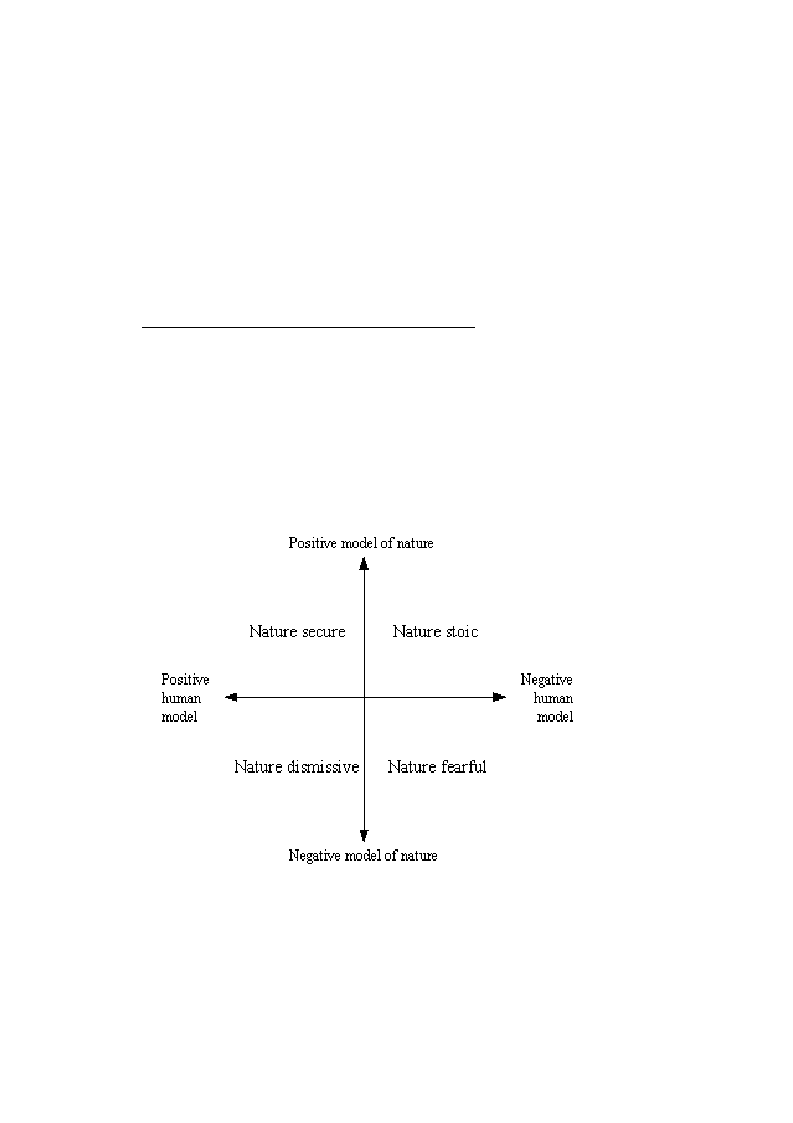

9.8.3 Dimensions of attachment to nature ............................................................................. 276

9.8.4 A model for a General Theory of Attachment............................................................... 278

9.8.5 Environmentalism as motivation for learning about (attachment to) nature?............ 283

9.9

CONCLUSIONS: WHAT WAS INTENDED AND PULLING THE STRANDS OF THEORY TOGETHER

286

Chapter 10: Consequences, applications and further research .......................... 290

10.1 APPLICATIONS ......................................................................................................................... 291

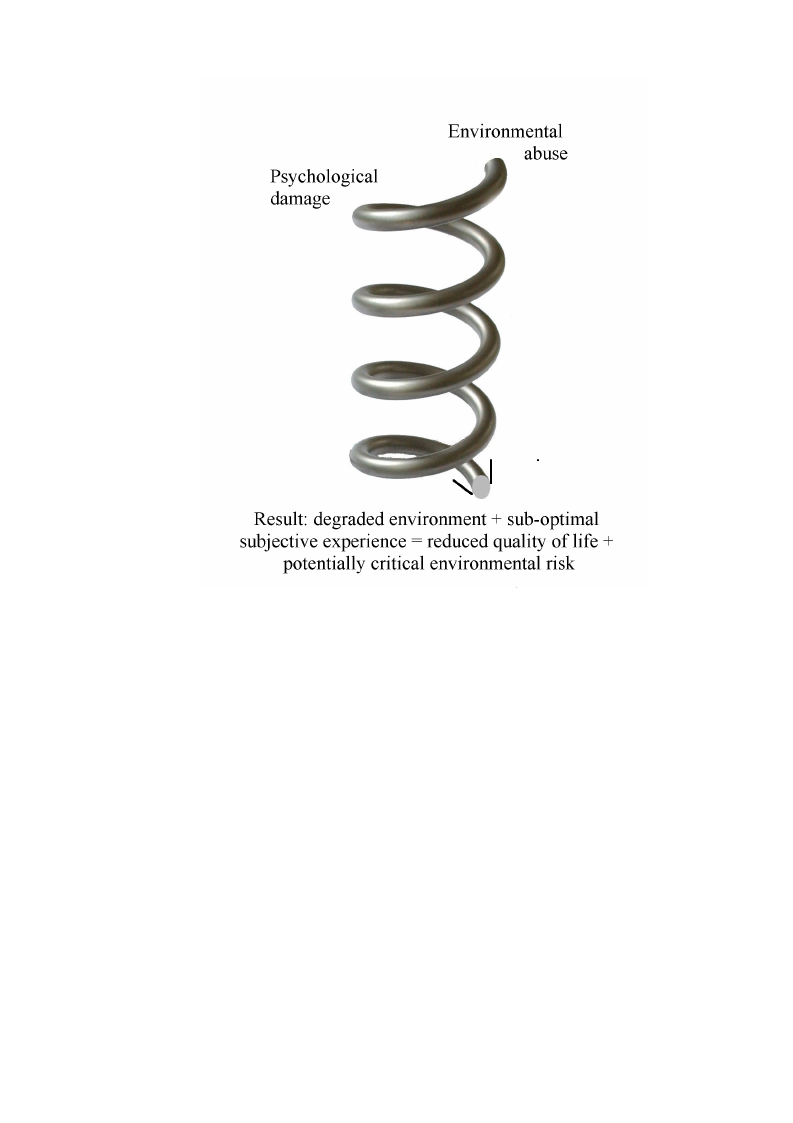

10.1.1 An intergenerational downward spiral ......................................................................... 291

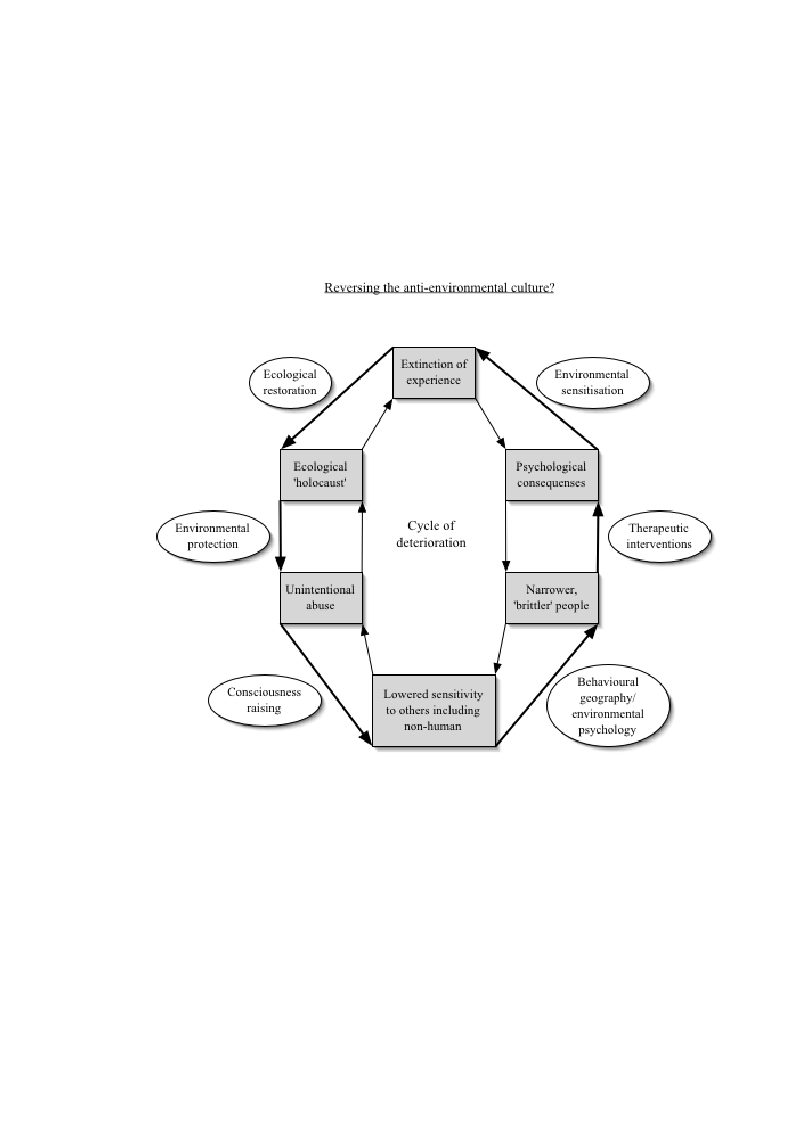

10.1.2 Reversing an anti-environmental culture?.................................................................... 294

10.1.3 ‘Clinical’ applications: possible positive interventions............................................... 298

10.1.3.1

Actions directed to benefit awareness of the non-human, in this generation ....................298

xi

10.1.3.2

Actions to change humans, in this generation ....................................................................299

10.1.3.3

Actions in favour of the non-human, over many generations............................................300

10.1.3.4

Actions to change human behaviour, over many generations ...........................................300

10.2 FURTHER RESEARCH ............................................................................................................... 301

10.2.1 Questions that may have improved this research......................................................... 301

10.2.2 Theoretical questions..................................................................................................... 302

10.2.3 Developmental questions............................................................................................... 304

10.2.4 Questions on the nature of relationships ...................................................................... 305

10.2.5 Educational questions ................................................................................................... 306

10.2.6 Health and mental health questions.............................................................................. 307

10.3 A LAST WORD .......................................................................................................................... 308

Chapter 11: Appendices.................................................................................. 309

11.1 QUESTIONNAIRE AS DEPLOYED............................................................................................... 309

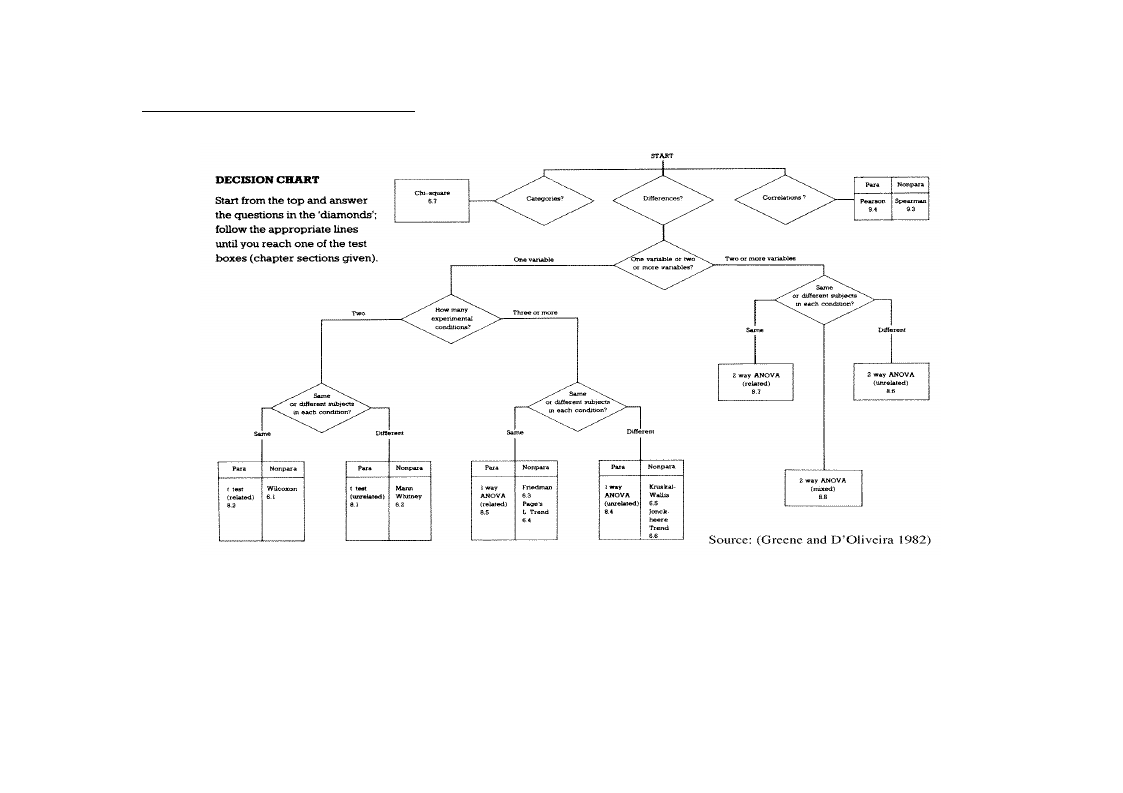

11.2 STATISTICAL TEST DECISION FLOW CHART............................................................................. 325

11.3 SUM OF SQUARES TABLES ....................................................................................................... 326

11.3.1 Sum of squares tables relating to Chapter 6.1 ............................................................. 326

11.3.1.1

Paternal attachment versus ecoevaluation ..........................................................................326

11.3.1.2

Maternal attachment versus ecoevaluation .........................................................................326

11.3.1.3

Paternal attachment versus ecoemotionality.......................................................................327

11.3.1.4

Maternal attachment versus ecoemotionality .....................................................................328

11.3.1.5

Paternal attachment versus relative sympathies .................................................................329

11.3.1.6

Maternal attachment versus relative sympathies ................................................................329

11.3.1.7

Paternal attachment versus selected attitudinal and behavioural measures.......................330

11.3.1.8

Maternal attachment versus selected attitudinal and behavioural measures .....................330

11.3.2 Sum of squares tables relating to Chapter 6.2 ............................................................. 331

11.3.2.1

Accessible nature versus ecoevaluation..............................................................................331

11.3.2.2

Accessible nature versus ecoemotionality ..........................................................................332

11.3.2.3

Accessible nature versus relative sympathies.....................................................................333

11.3.2.4

Play versus ecoevaluation....................................................................................................333

11.3.2.5

Play versus ecoemotionality................................................................................................334

11.3.2.6

Play versus relative sympathies...........................................................................................335

11.3.2.7

Wander versus ecoevaluation..............................................................................................335

11.3.2.8

Wander versus ecoemotionality ..........................................................................................336

11.3.2.9

Wander versus relative sympathies.....................................................................................337

11.3.3 Sum of squares tables relating to Chapter 6.3 ............................................................. 337

11.3.3.1

Parental ecoactivity and ecoevaluation...............................................................................337

11.3.3.2

Parental ecoactivity and ecoemotionality ...........................................................................338

11.3.3.3

Parental ecoactivity and relative sympathies......................................................................339

11.3.3.4

Nature mentor and ecoevaluation........................................................................................339

11.3.3.5

Nature mentor and ecoemotionality ....................................................................................340

11.3.3.6

Nature mentor and relative sympathies...............................................................................341

11.3.3.7

Ecoparenting and ecoevaluation..........................................................................................342

11.3.3.8

Ecoparenting and ecoemotionality......................................................................................342

11.3.3.9

Ecoparenting and relative sympathies.................................................................................343

11.3.4 Sum of squares tables relating to Chapter 7 ................................................................ 344

11.3.4.1

Nature hobbies and ecoevaluation.......................................................................................344

11.3.4.1.1 Nature hobby (Q2.20) .....................................................................................................344

11.3.4.1.2 Hobby frequency (Q2.21) ...............................................................................................344

11.3.4.1.3 Favourite hobby (Q2.22).................................................................................................345

11.3.4.2

Nature hobbies and ecoemotionality...................................................................................346

11.3.4.2.1 Nature hobby (Q2.20) .....................................................................................................346

11.3.4.2.2 Hobby frequency (Q2.21) ...............................................................................................347

11.3.4.2.3 Favourite hobby (Q2.22).................................................................................................347

11.3.4.3

Nature hobbies and relative sympathies .............................................................................348

11.3.4.3.1 Nature hobby (Q2.20) .....................................................................................................348

11.3.4.3.2 Hobby frequency (Q2.21) ...............................................................................................349

11.3.4.3.3 Favourite hobby (Q2.22).................................................................................................349

11.3.4.4

Nature media and ecoevaluation .........................................................................................350

11.3.4.4.1 Read Books (Q2.23)........................................................................................................350

11.3.4.4.2 TV (Q2.24) ......................................................................................................................351

xii

11.3.4.4.3 TV Frequency (Q2.25) ....................................................................................................352

11.3.4.5

Nature media and ecoemotionality......................................................................................352

11.3.4.5.1 Read Books (Q2.23) ........................................................................................................352

11.3.4.5.2 TV (Q2.24).......................................................................................................................353

11.3.4.5.3 TV Frequency (Q2.25) ....................................................................................................354

11.3.4.6

Nature media and relative sympathies ................................................................................355

11.3.4.6.1 Read Books (Q2.23) ........................................................................................................355

11.3.4.6.2 TV (Q2.24).......................................................................................................................355

11.3.4.6.3 TV Frequency (Q2.25) ....................................................................................................356

11.3.4.7

Nature child and ecoevaluation ...........................................................................................356

11.3.4.8

Nature child and ecoemotionality........................................................................................357

11.3.4.9

Nature child and relative sympathies ..................................................................................358

11.3.4.10 Pets and ecoevaluation.........................................................................................................359

11.3.4.10.1 Pets (Q2.18)...................................................................................................................359

11.3.4.10.2 Pet Types (Q2.19) .........................................................................................................359

11.3.4.10.3 Mammal Types..............................................................................................................360

11.3.4.10.4 Non-mammal Types......................................................................................................361

11.3.4.11 Pets and ecoemotionality .....................................................................................................362

11.3.4.11.1 Pets (Q2.18)...................................................................................................................362

11.3.4.11.2 Pet Types (Q2.19) .........................................................................................................362

11.3.4.11.3 Mammal Types..............................................................................................................363

11.3.4.11.4 Non-mammal Types......................................................................................................364

11.3.4.12 Pets and relative sympathies................................................................................................365

11.3.4.12.1 Pets (Q2.18)...................................................................................................................365

11.3.4.12.2 Pet Types (Q2.19) .........................................................................................................365

11.3.4.12.3 Mammal Types..............................................................................................................366

11.3.4.12.4 Non-mammal Types......................................................................................................366

11.3.4.13 Menagerie and ecoevaluation ..............................................................................................367

11.3.4.13.1 Menagerie Index............................................................................................................367

11.3.4.13.2 Siblings ..........................................................................................................................368

11.3.4.14 Menagerie and ecoemotionality...........................................................................................369

11.3.4.14.1 Menagerie Index............................................................................................................369

11.3.4.14.2 Siblings ..........................................................................................................................369

11.3.4.15 Menagerie and relative sympathies .....................................................................................370

11.3.4.15.1 Menagerie Index............................................................................................................370

11.3.4.15.2 Siblings ..........................................................................................................................371

11.3.4.16 Child movements and ecoevaluation...................................................................................371

11.3.4.17 Child movements and ecoemotionality...............................................................................372

11.3.4.18 Child movements and relative sympathies..........................................................................373

11.3.4.19 Social class and ecoevaluation ............................................................................................373

11.3.4.20 Social class and ecoemotionality.........................................................................................374

11.3.4.21 Social class and relative sympathies ...................................................................................375

11.3.4.22 Education and ecoevaluation ...............................................................................................375

11.3.4.23 Education and ecoemotionality ...........................................................................................376

11.3.4.24 Education and relative sympathies ......................................................................................377

11.3.4.25 Adult home and ecoevaluation ............................................................................................378

11.3.4.26 Adult home and ecoemotionality.........................................................................................378

11.3.4.27 Adult home and relative sympathies ...................................................................................379

11.4 LIST OF FILES ON ACCOMPANYING CD-ROM......................................................................... 381

11.5 INDEX TO SPSS OUTPUT FILES ............................................................................................... 381

Chapter 6.1.....................................................................................................................................................381

Chapter 6.2.....................................................................................................................................................381

Chapter 6.3.....................................................................................................................................................381

Chapter 7........................................................................................................................................................382

Bibliography ................................................................................................. 383

xiii

Table of Figures

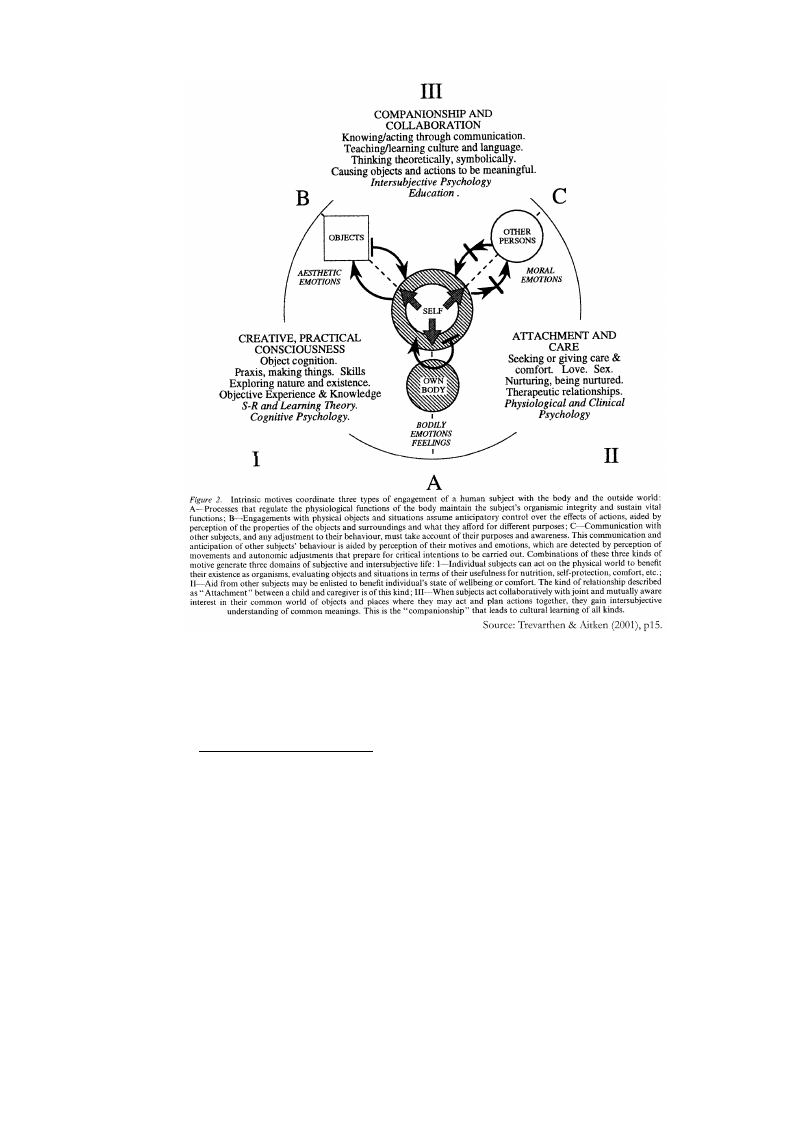

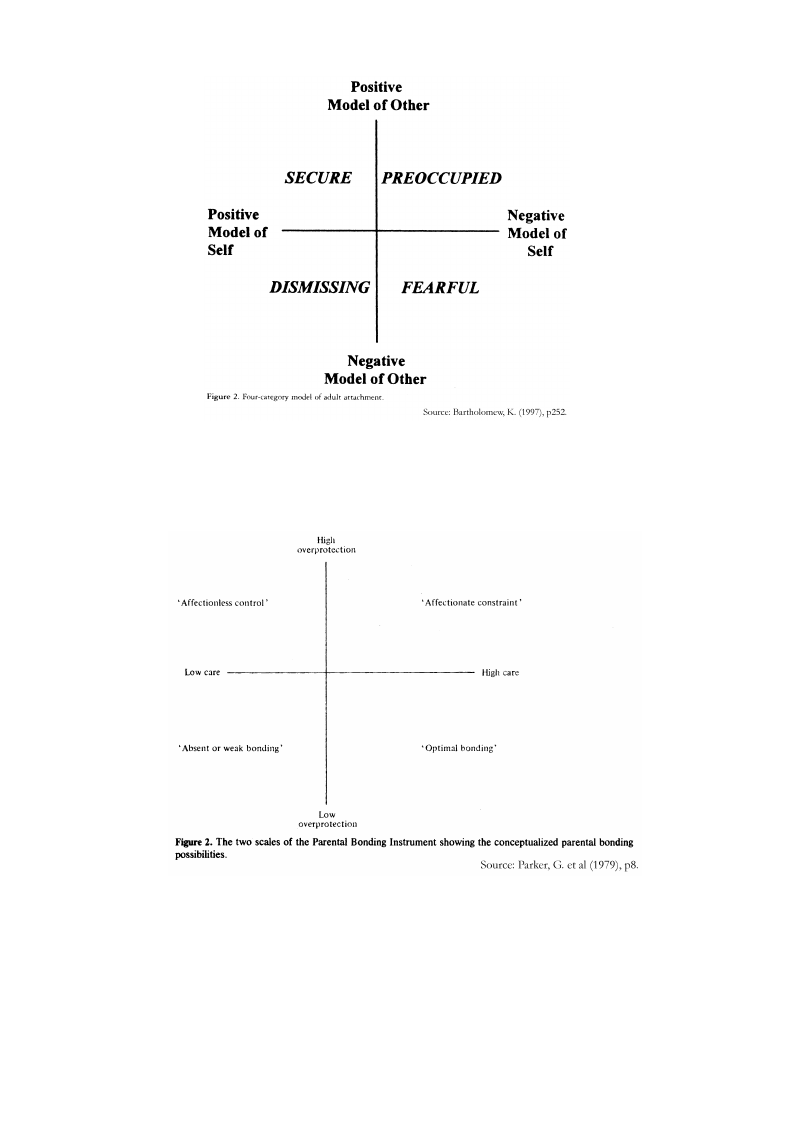

Figure 2.1: Trevarthen’s three relational domains ......................................................................33

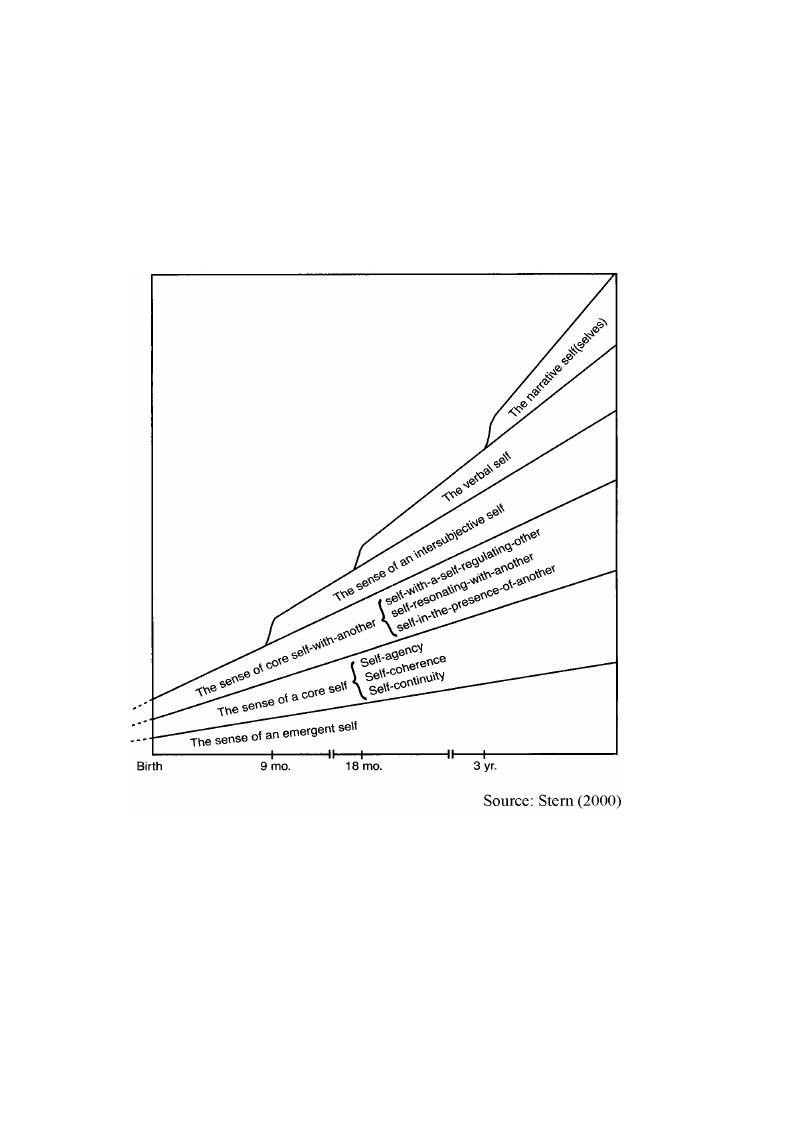

Figure 2.2: Stern’s conception of the emergence of self ............................................................34

Figure 2.3: Bartholomew’s four-category model of adult attachment .......................................40

Figure 2.4: Parental Bonding Instrument scales..........................................................................40

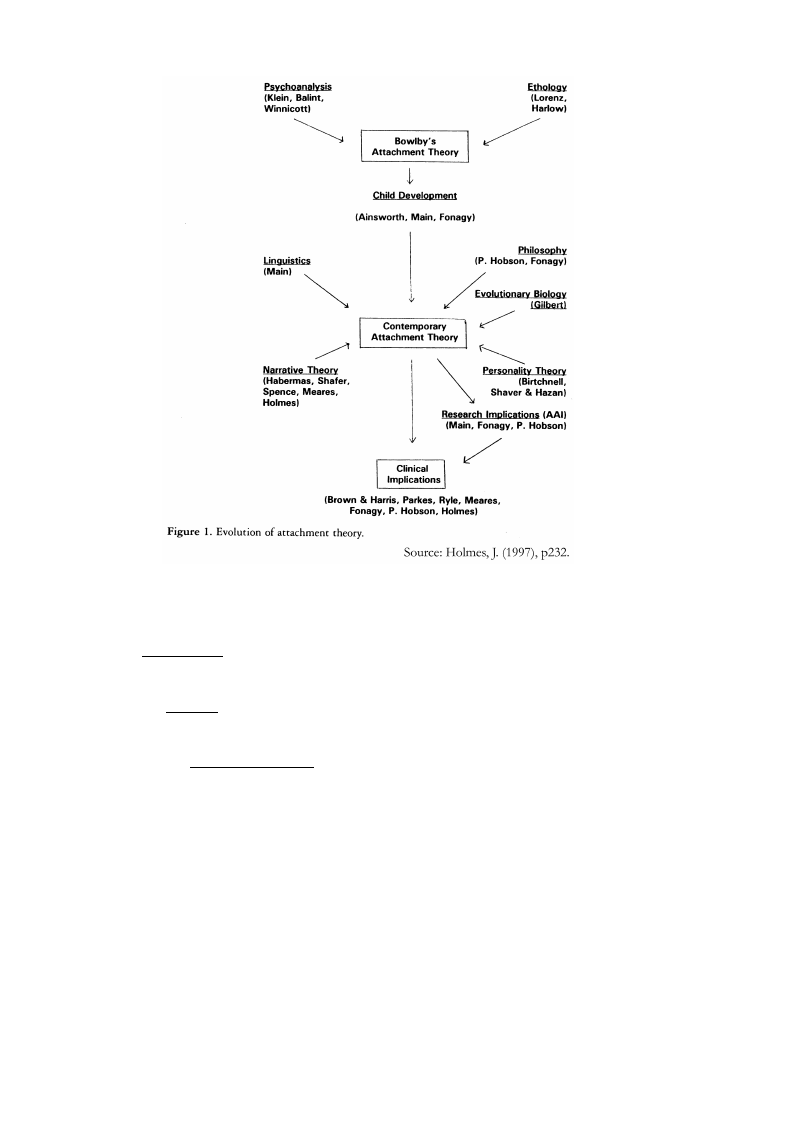

Figure 2.5: Evolution of attachment theory.................................................................................42

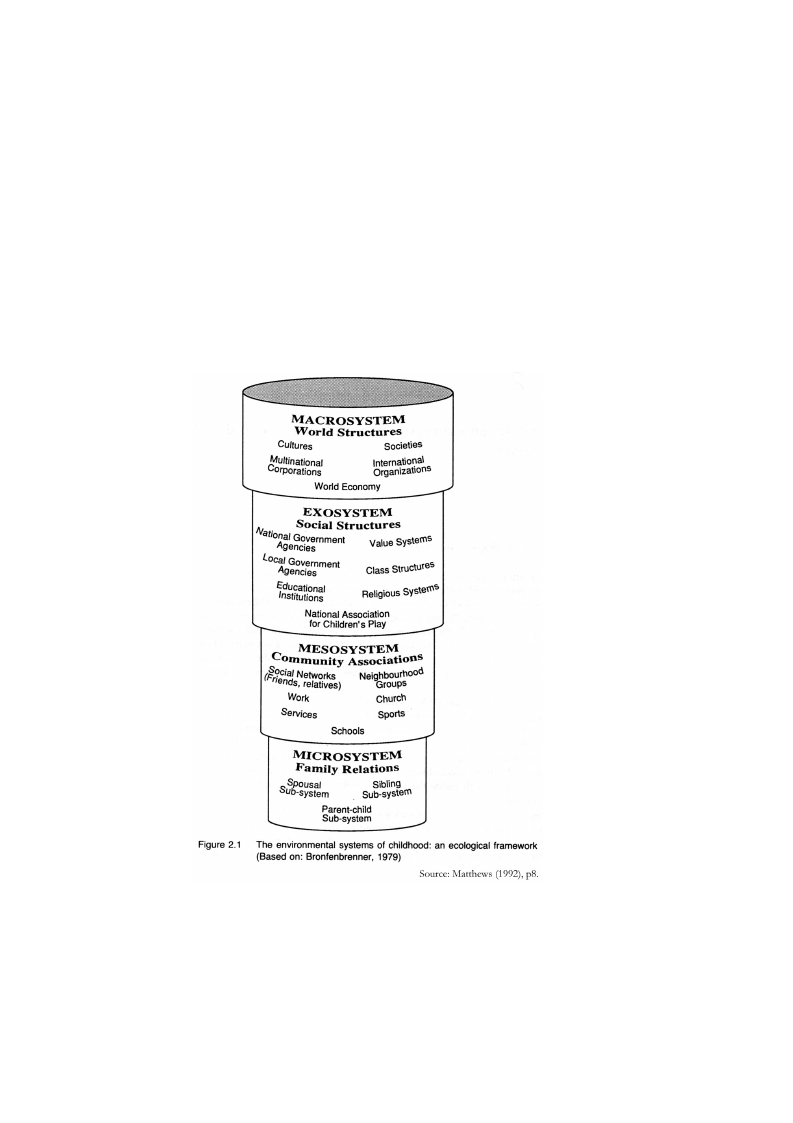

Figure 2.6: Bronfenbrenner’s microsystem-macrosystem model...............................................58

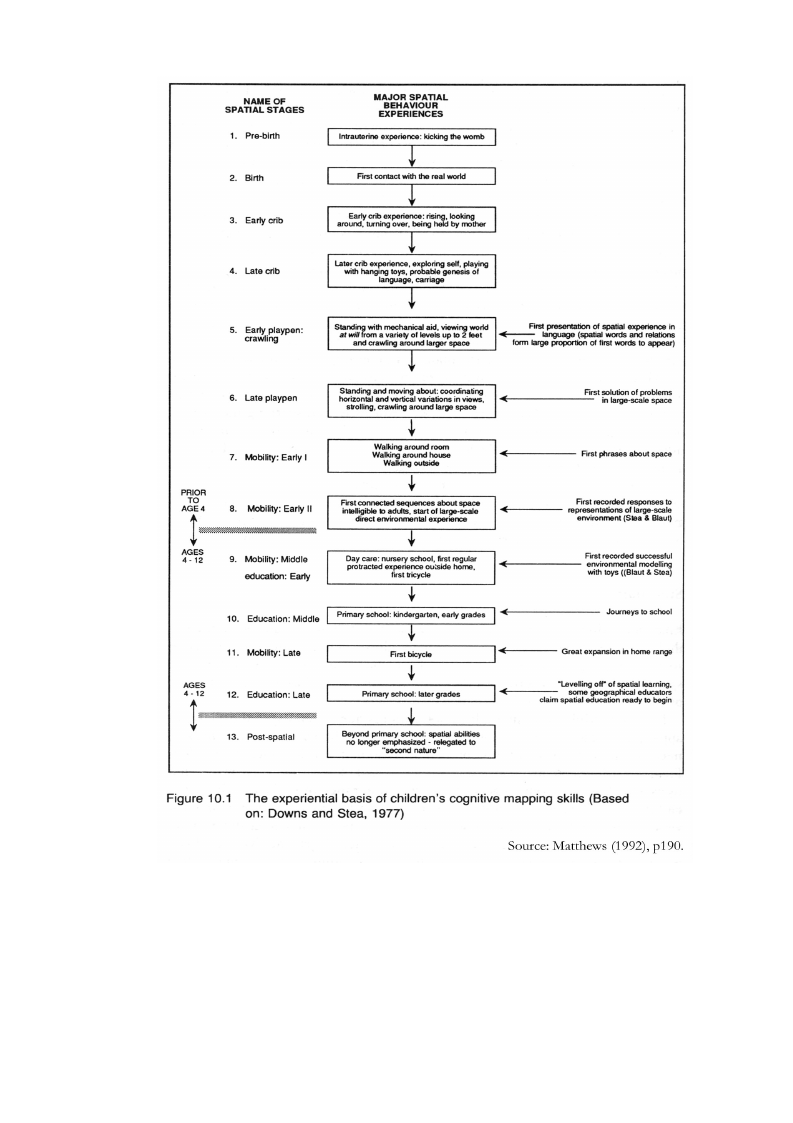

Figure 2.7: Matthews' experiential basis of mapping .................................................................67

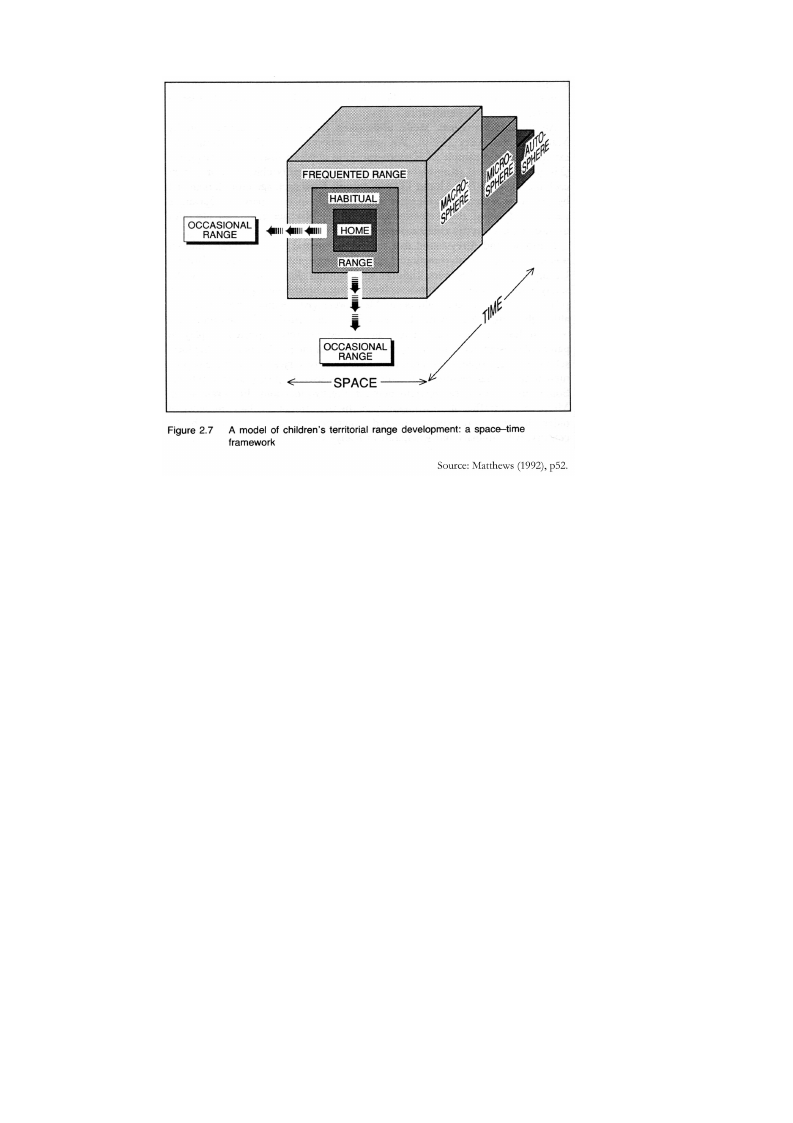

Figure 2.8: Matthews’ model of children’s range development.................................................68

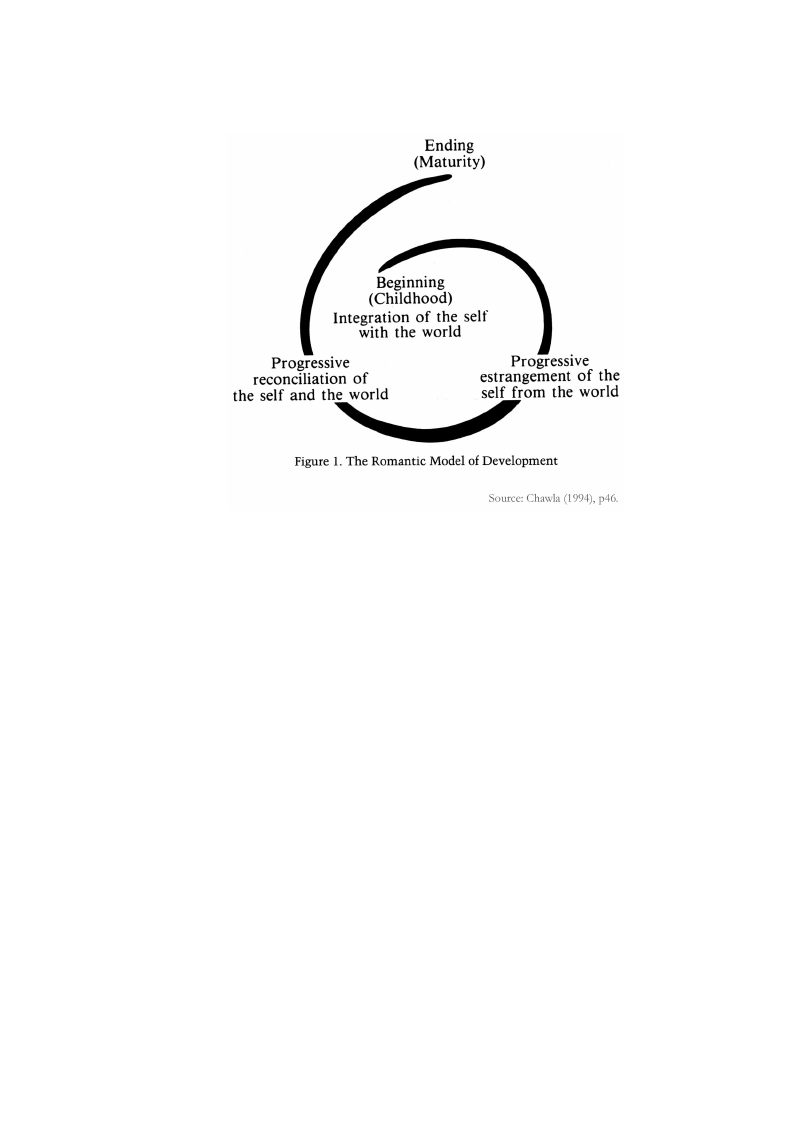

Figure 2.9: Romantic model of personal development...............................................................73

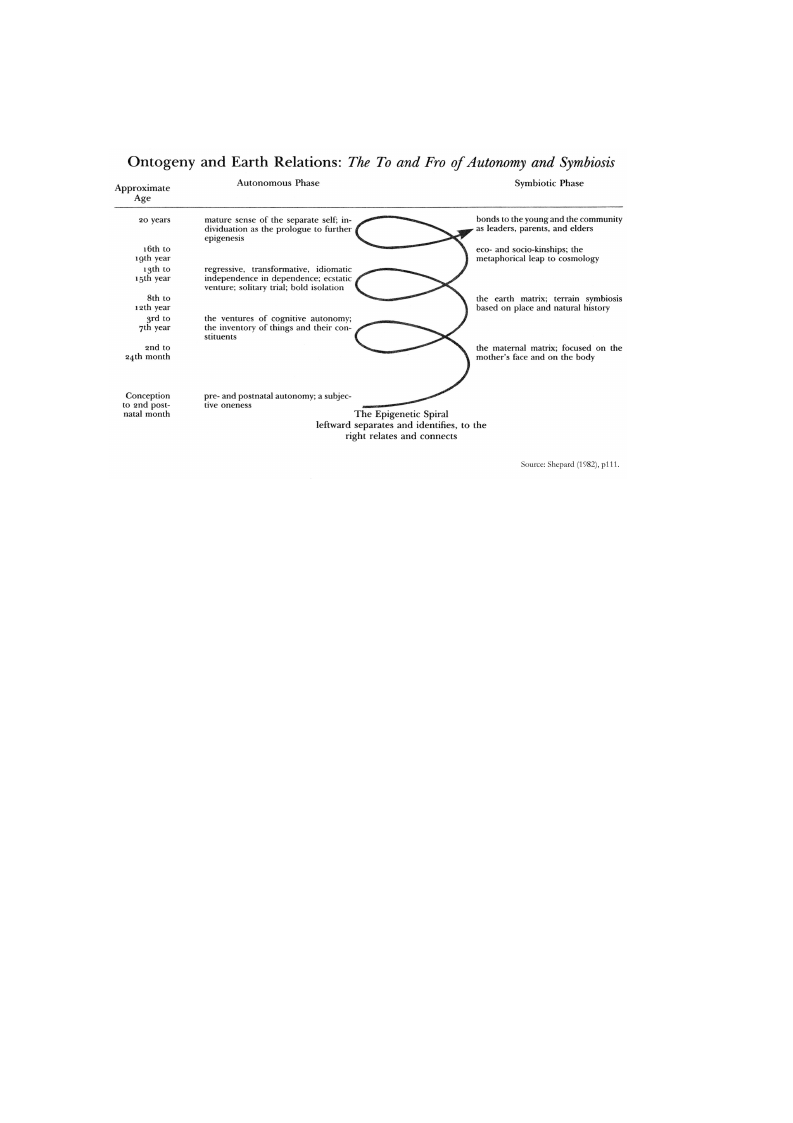

Figure 2.10: Ontogeny and earth relations ..................................................................................74

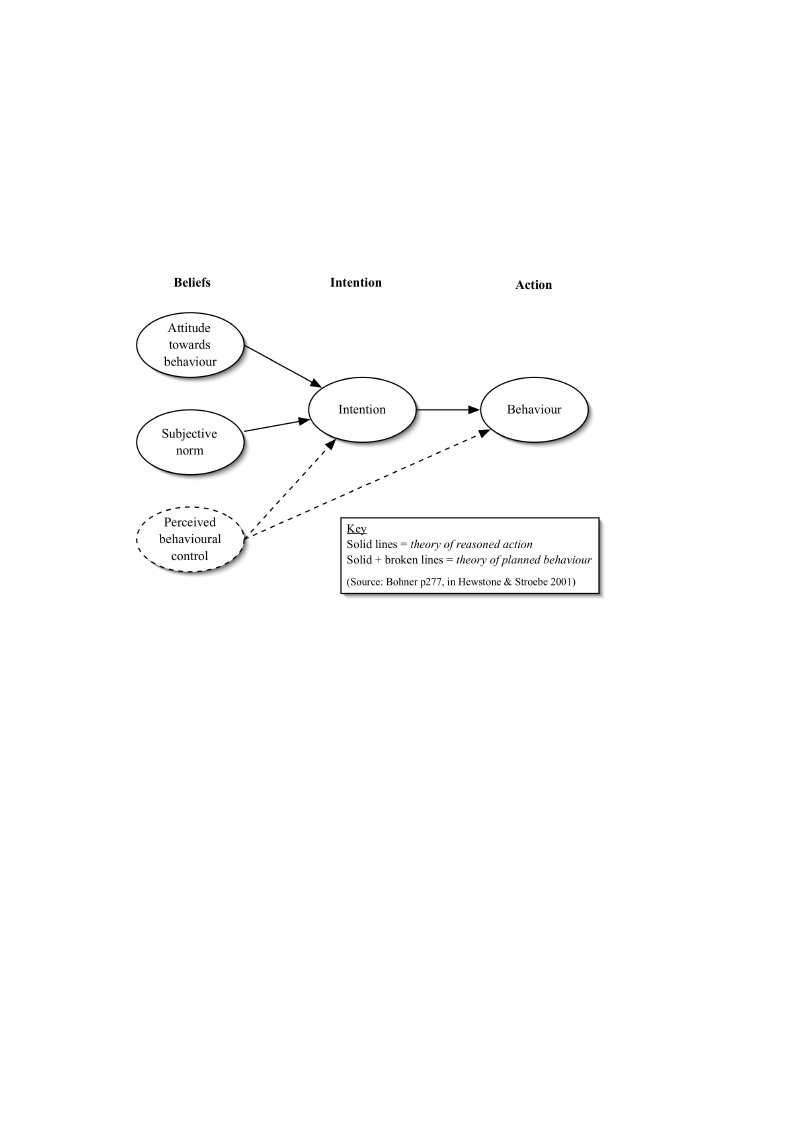

Figure 3.1: Theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour................................................78

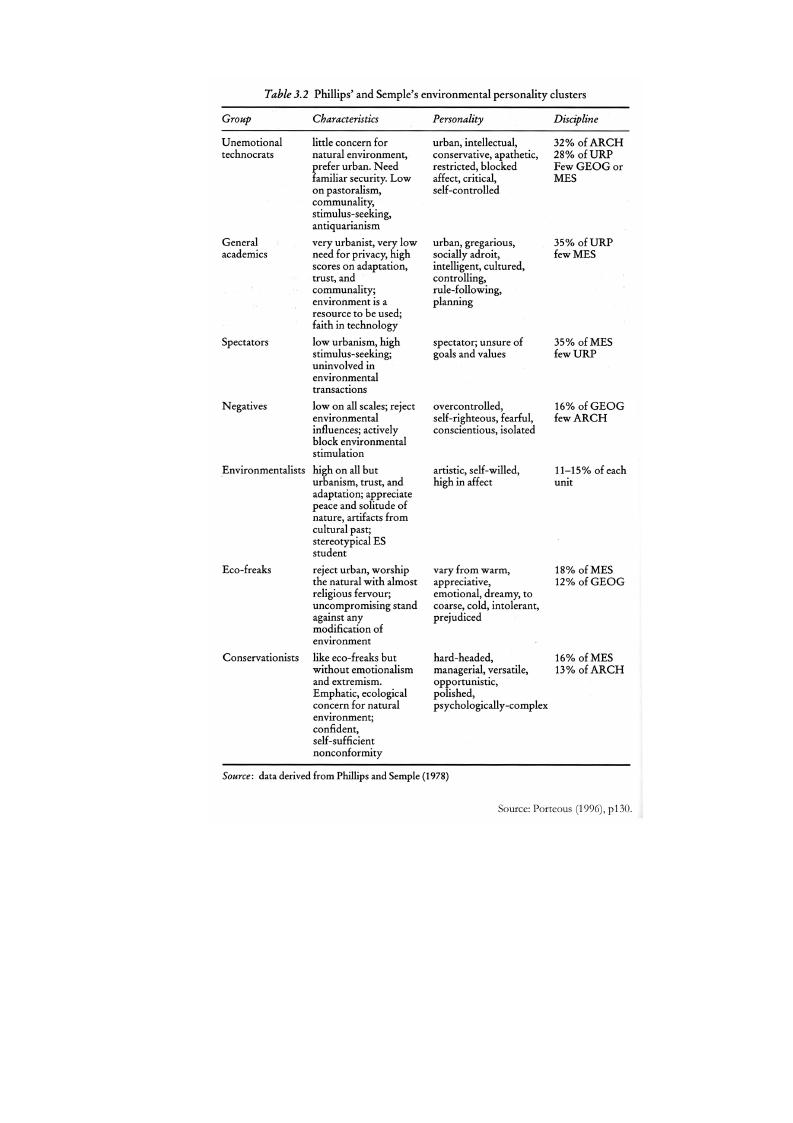

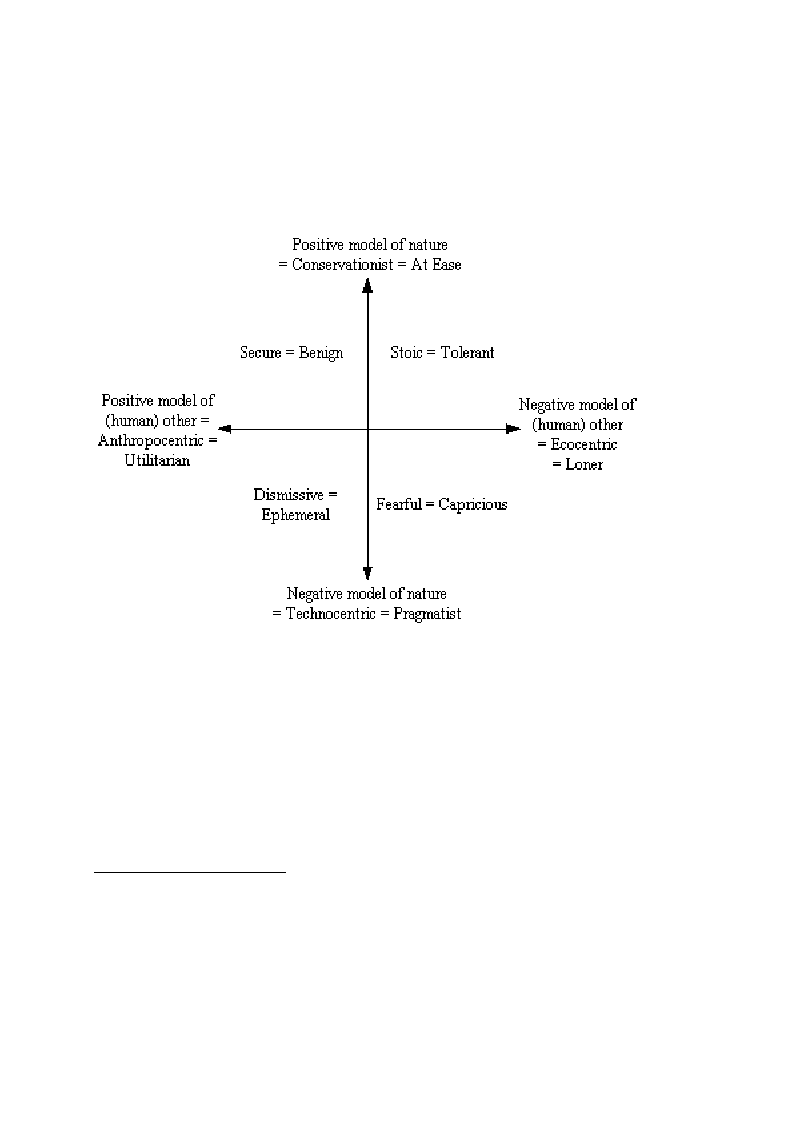

Figure 3.2: Environmental personality clusters...........................................................................87

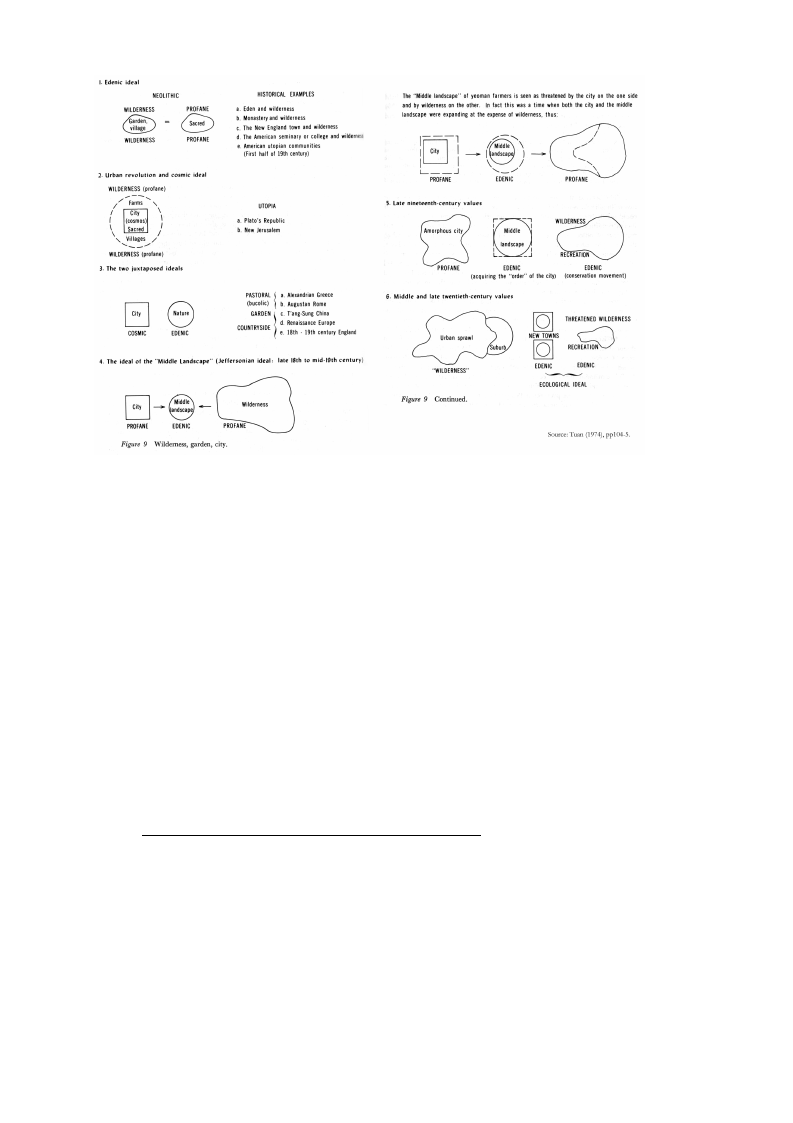

Figure 3.3: Tuan’s cultural evolution of human-nature relations...............................................92

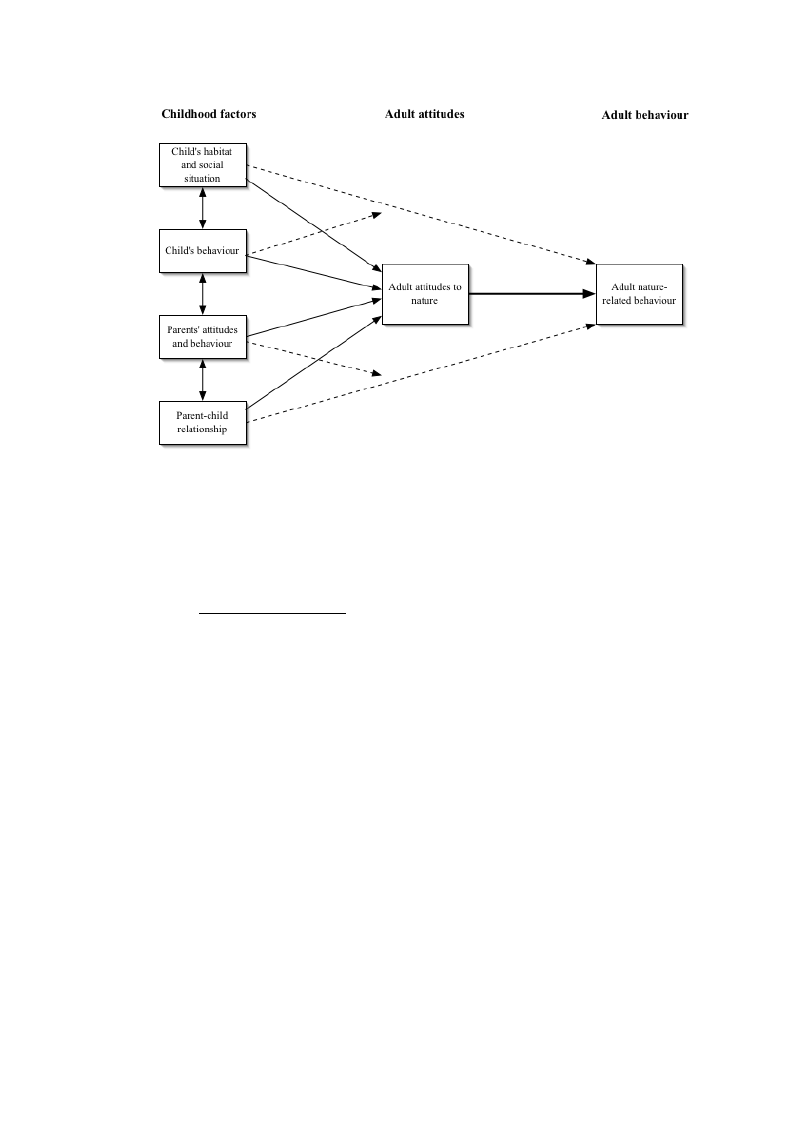

Figure 4.1: A model for the origination of environmental attitudes and behaviour ................101

Figure 5.1: Social class distribution of sample .........................................................................118

Figure 5.2: Model for variables in the Questionnaire ...............................................................120

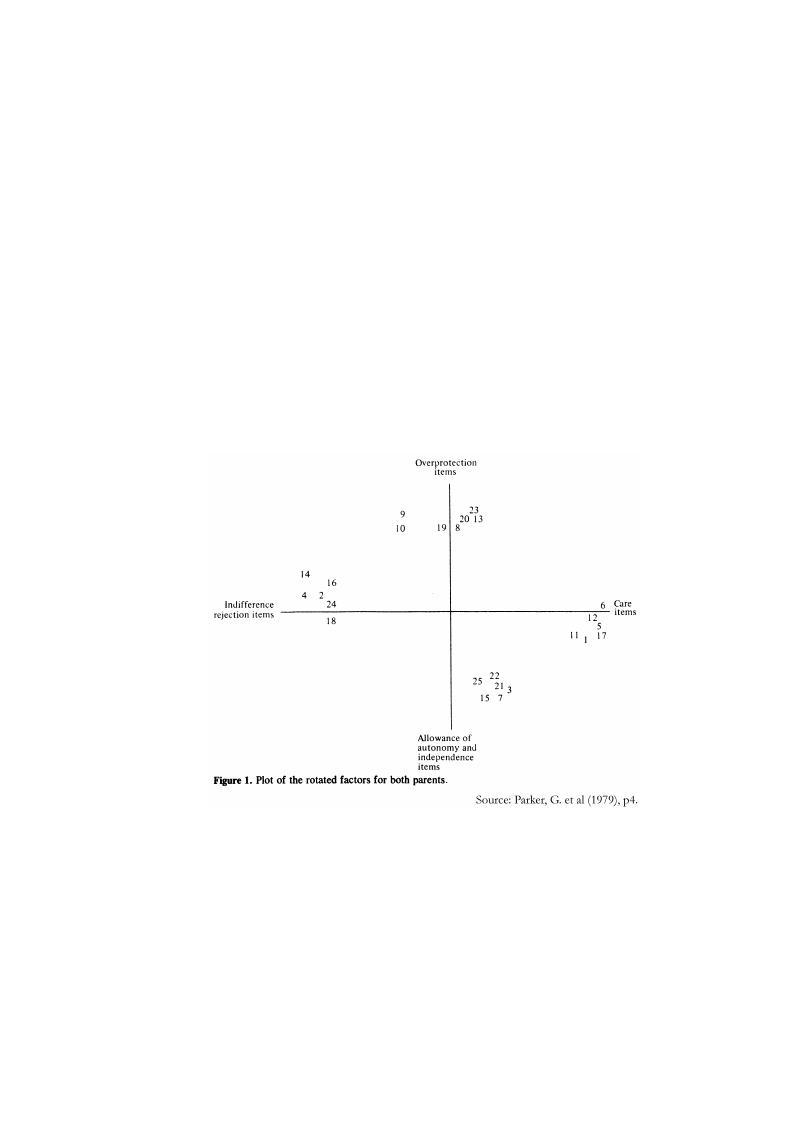

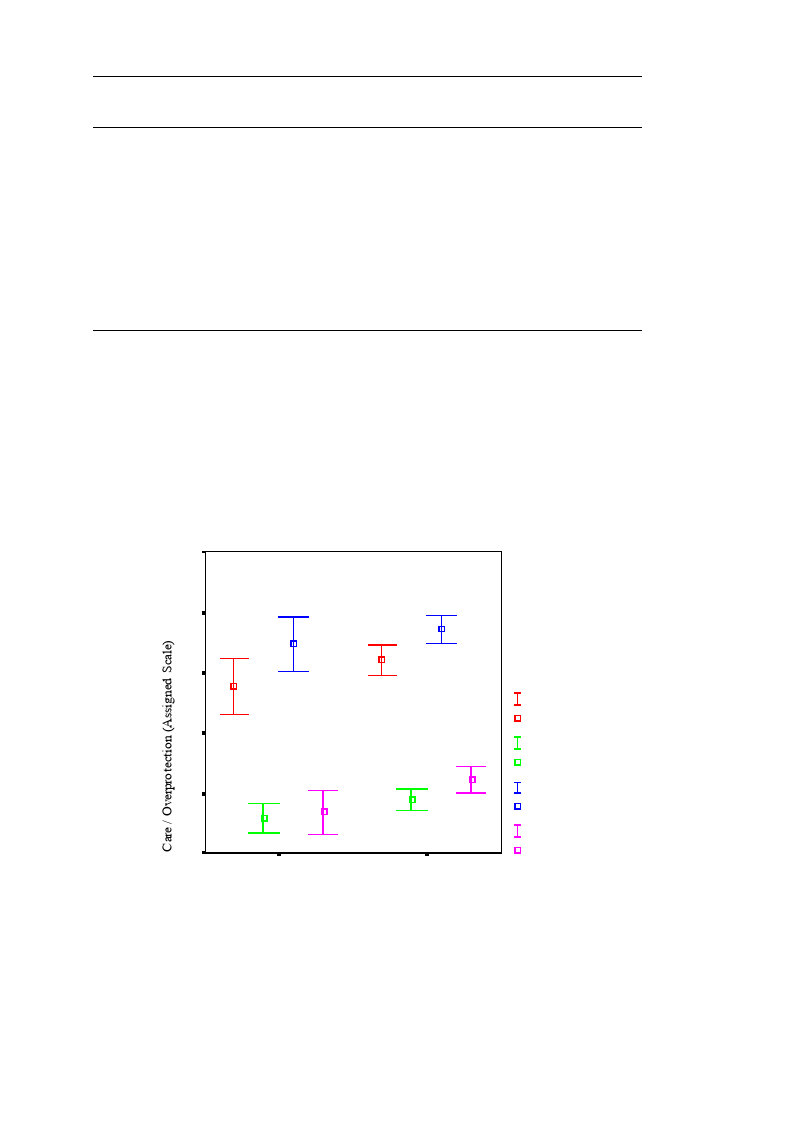

Figure 5.3: Item dimensions plot for Parental Bonding Index .................................................131

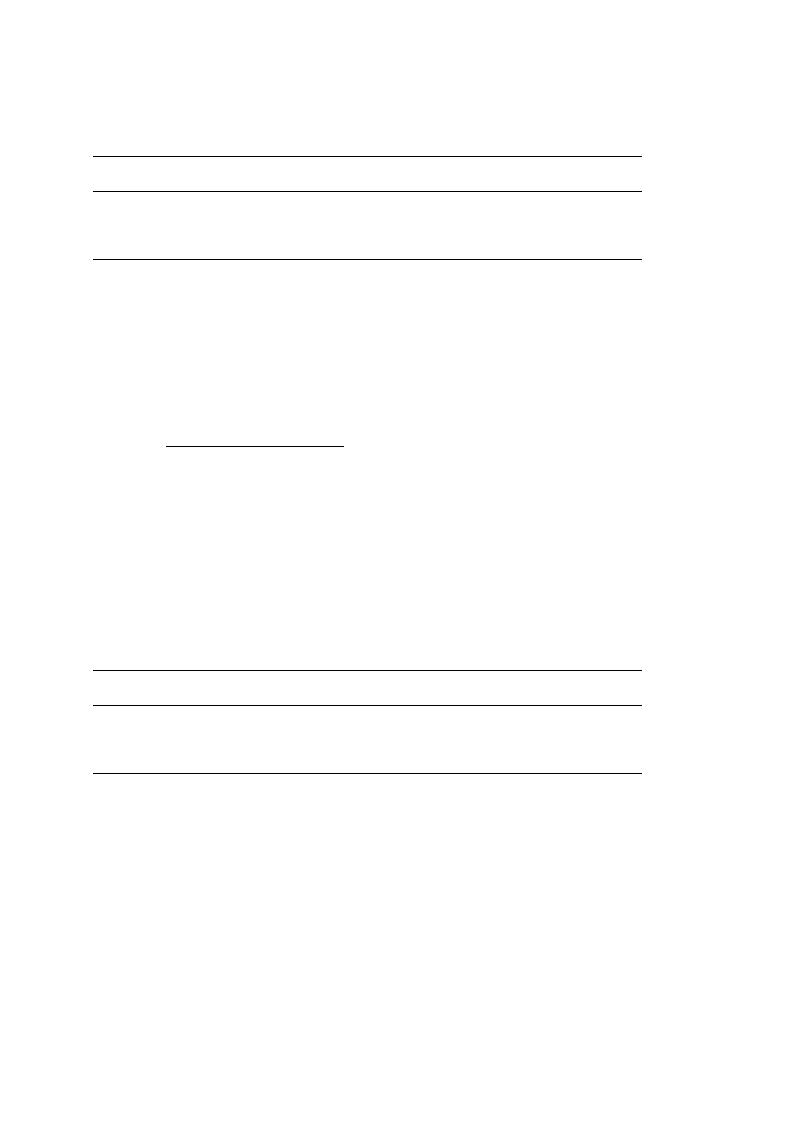

Figure 6.1: Favourite place location versus parental attachment factor scores........................162

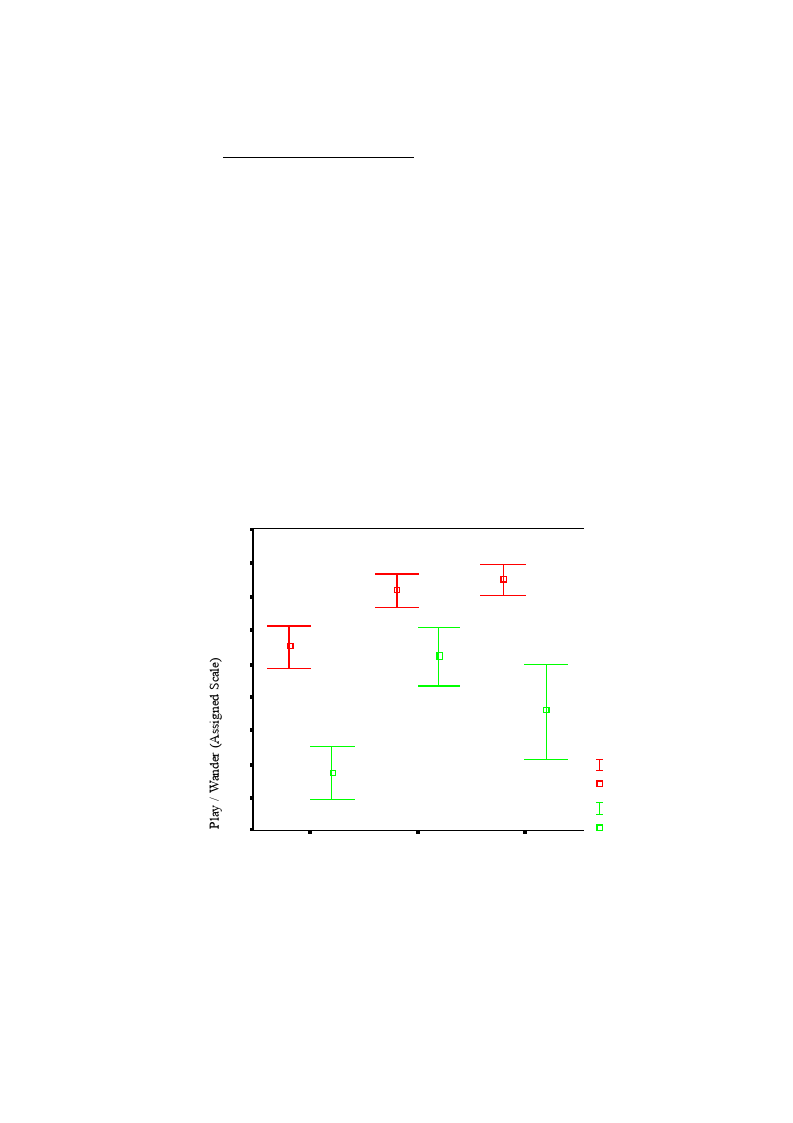

Figure 6.2: Play / Wander versus paternal overprotection........................................................163

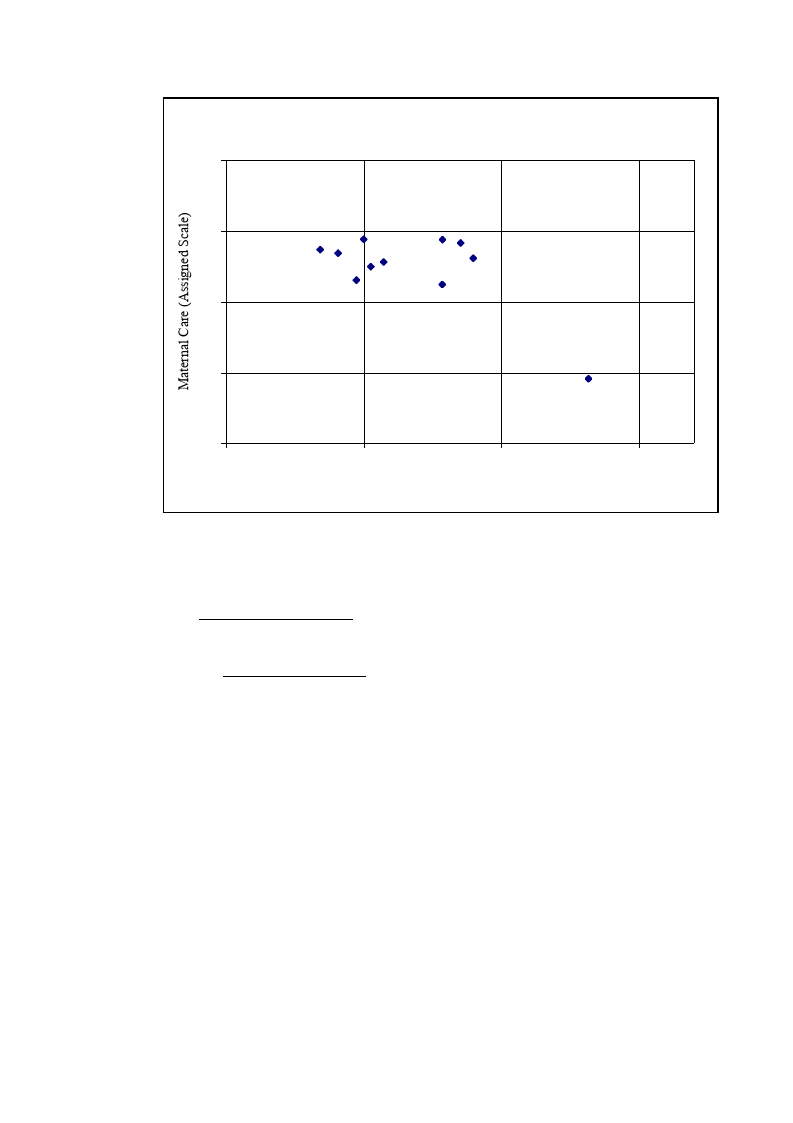

Figure 6.3: Maternal Attachment Status versus Sample Sub-group.........................................165

Figure 6.4: Childhood residence versus relative sympathy factor scores ................................170

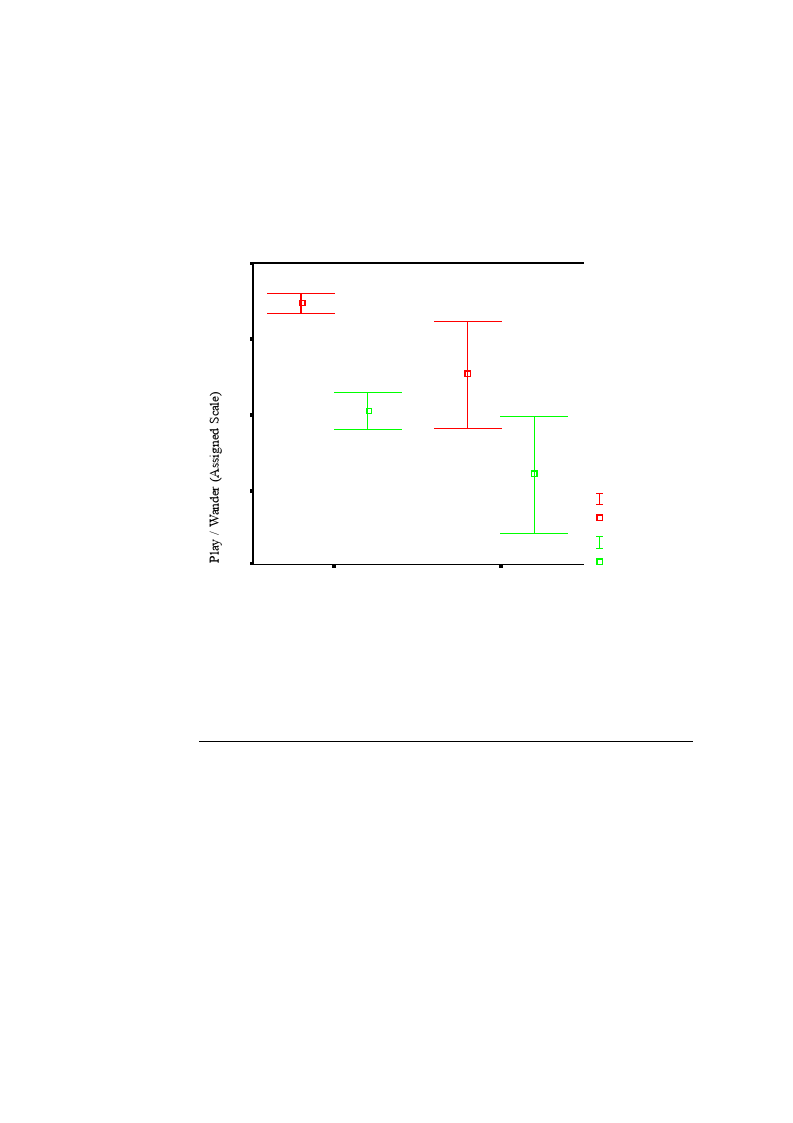

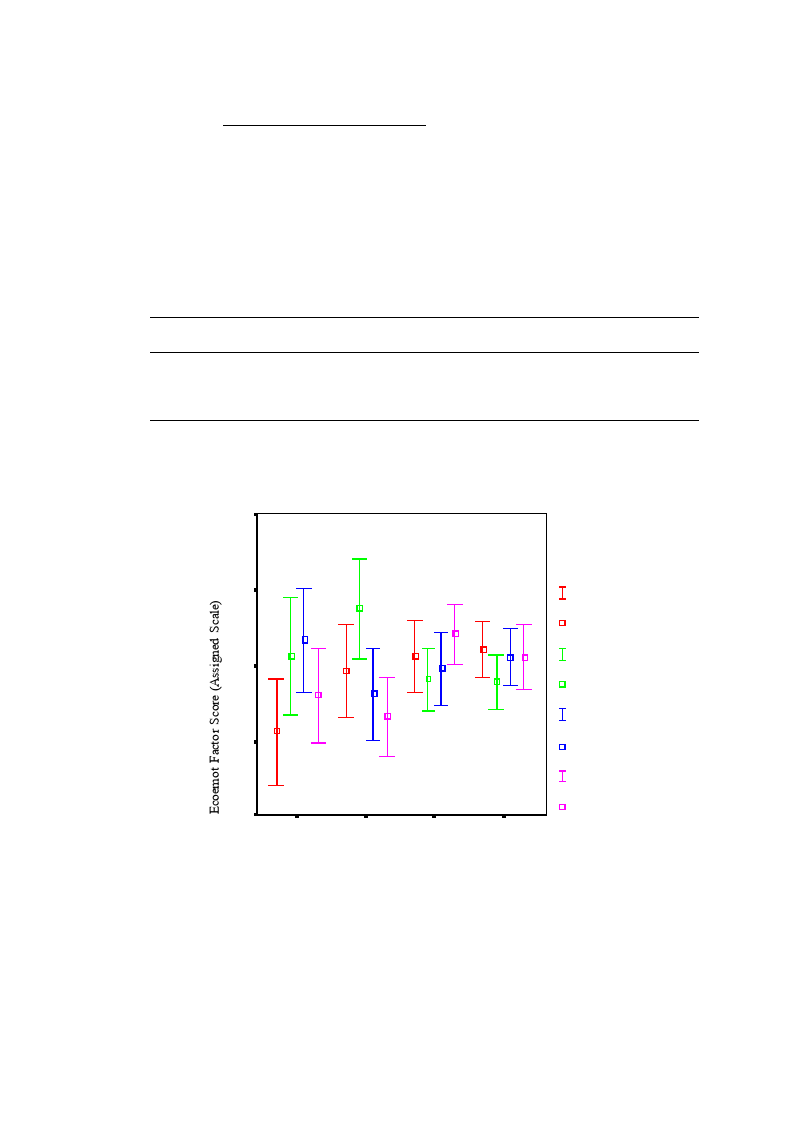

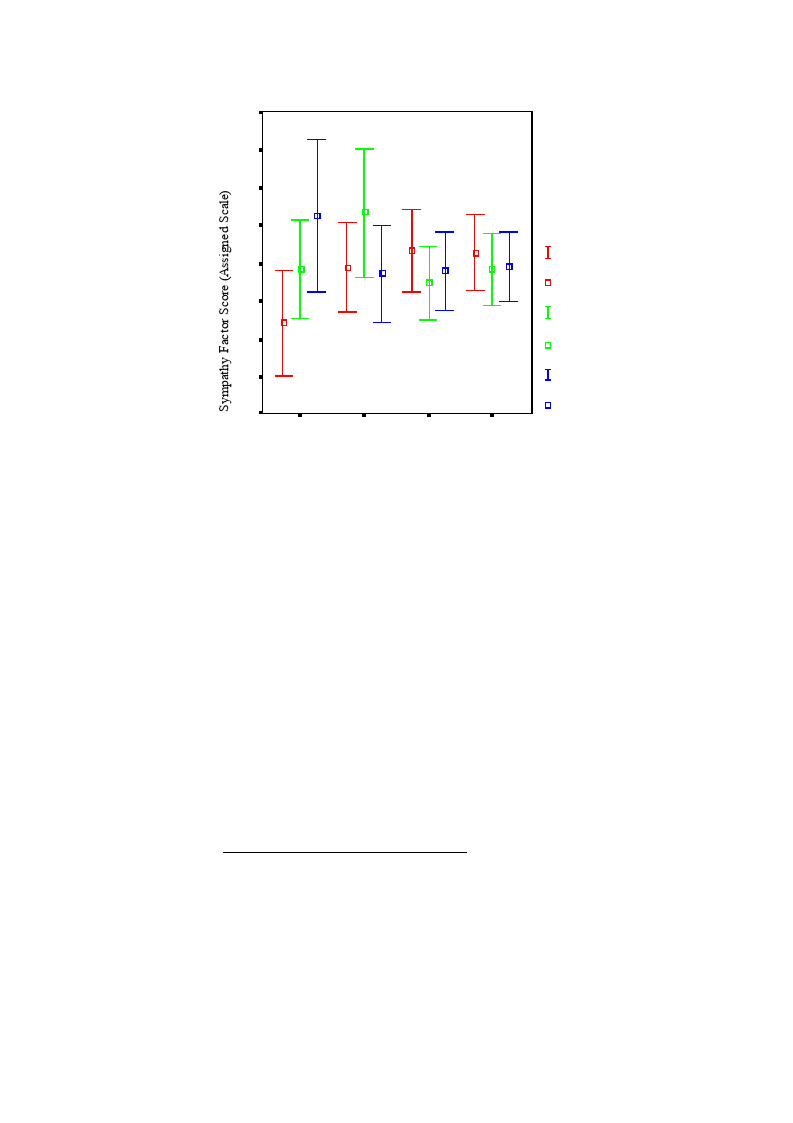

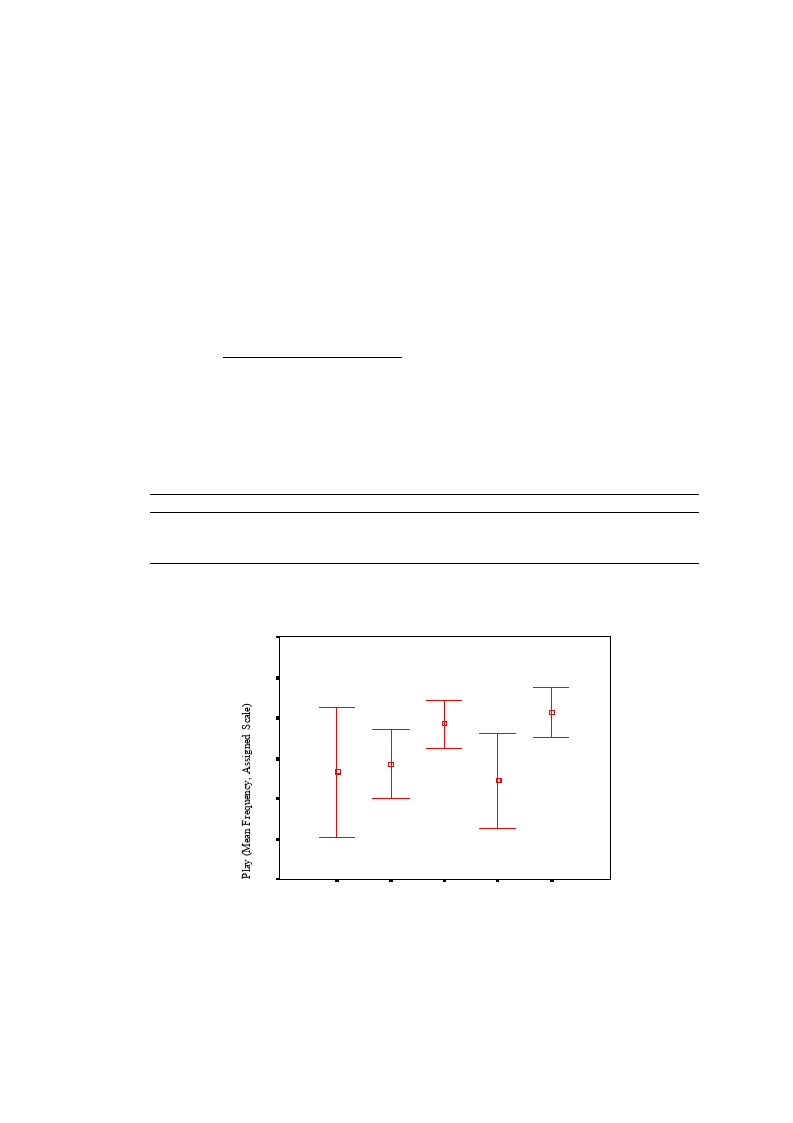

Figure 6.5: Play versus ecoemotionality factor scores..............................................................173

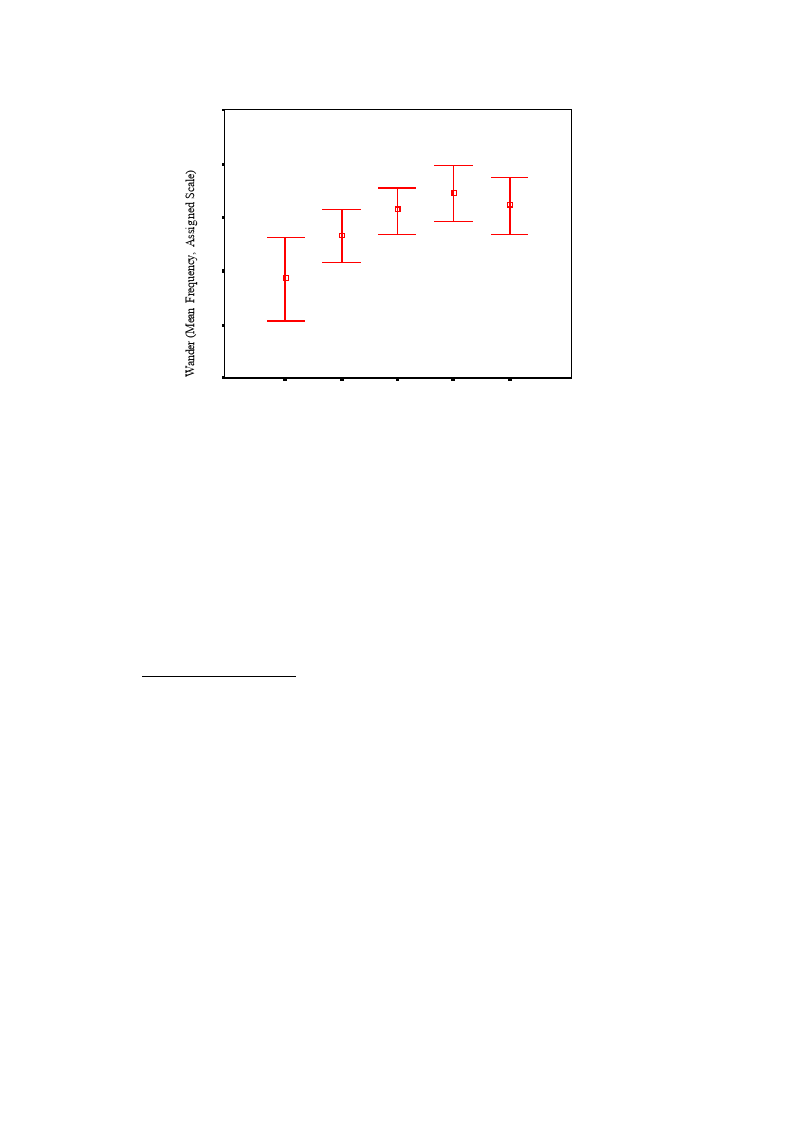

Figure 6.6: Wander versus ecoemotionality factor scores........................................................175

Figure 6.7: Wander versus relative sympathy factor scores .....................................................177

Figure 6.8: Favourite place versus ecoevaluation factor scores ...............................................179

Figure 6.9: Favourite place location versus ecoevaluation factor scores.................................179

Figure 6.10: Favourite place proximity versus ecoevaluation factor scores............................180

Figure 6.11: Favourite place versus ecoemotionality factor scores..........................................181

Figure 6.12: Favourite place location versus ecoemotionality factor scores ...........................182

Figure 6.13: Favourite place proximity versus ecoemotionality factor scores ........................182

Figure 6.14: Favourite place versus relative sympathy factor scores.......................................184

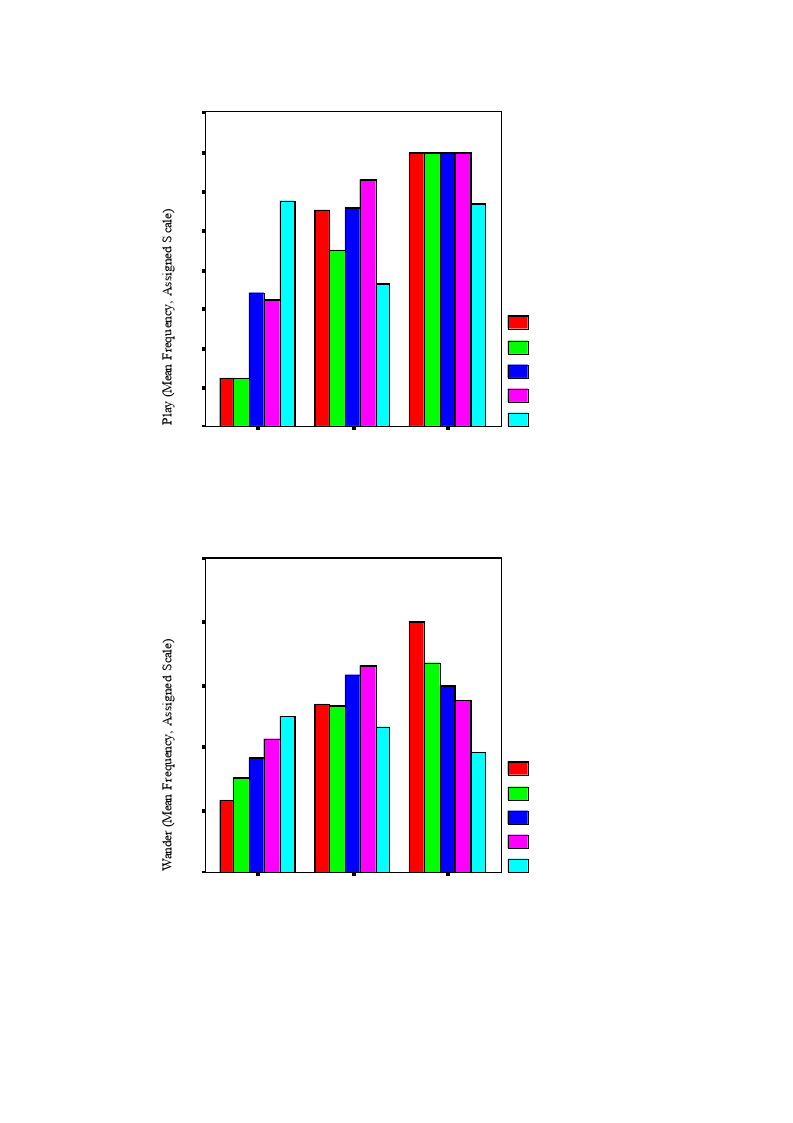

Figure 6.15: Mean play / wander frequency versus childhood residence ................................185

Figure 6.16: Play frequency versus childhood residence, by adult residence..........................186

Figure 6.17: Wander frequency versus childhood residence, by adult residence ....................186

Figure 6.18: Age band versus mean play ..................................................................................187

Figure 6.19: Age band versus mean wander .............................................................................188

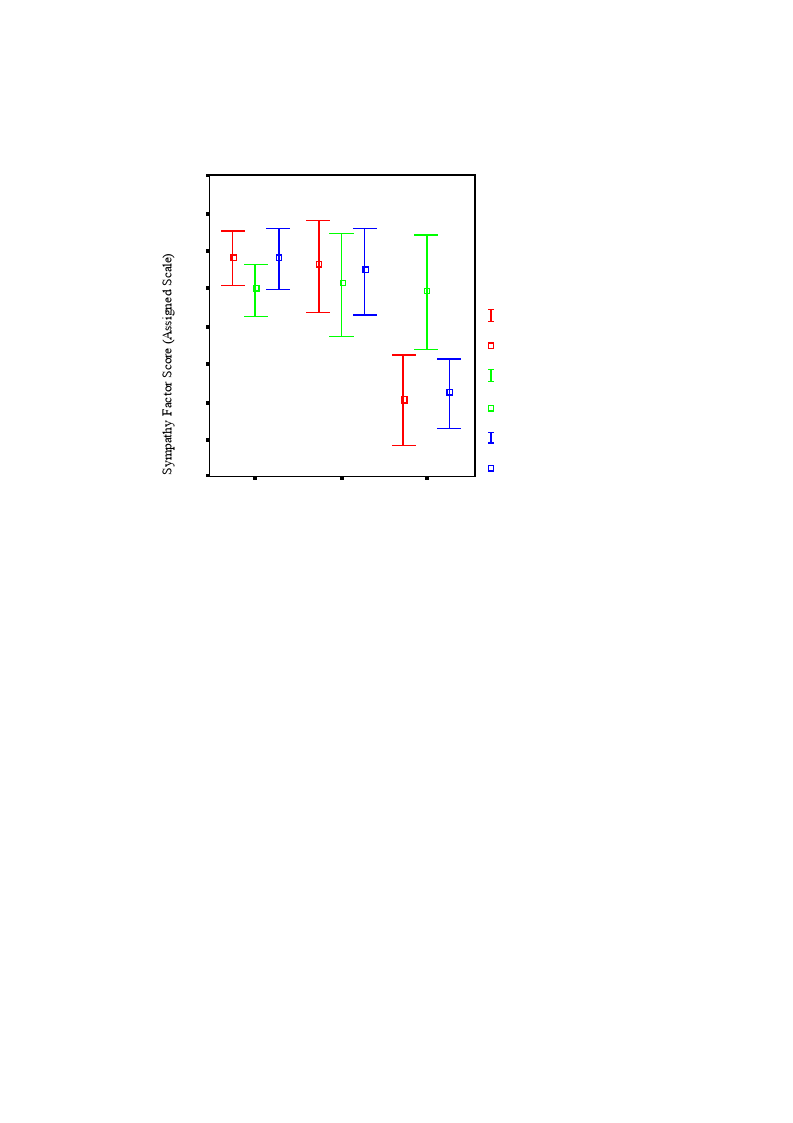

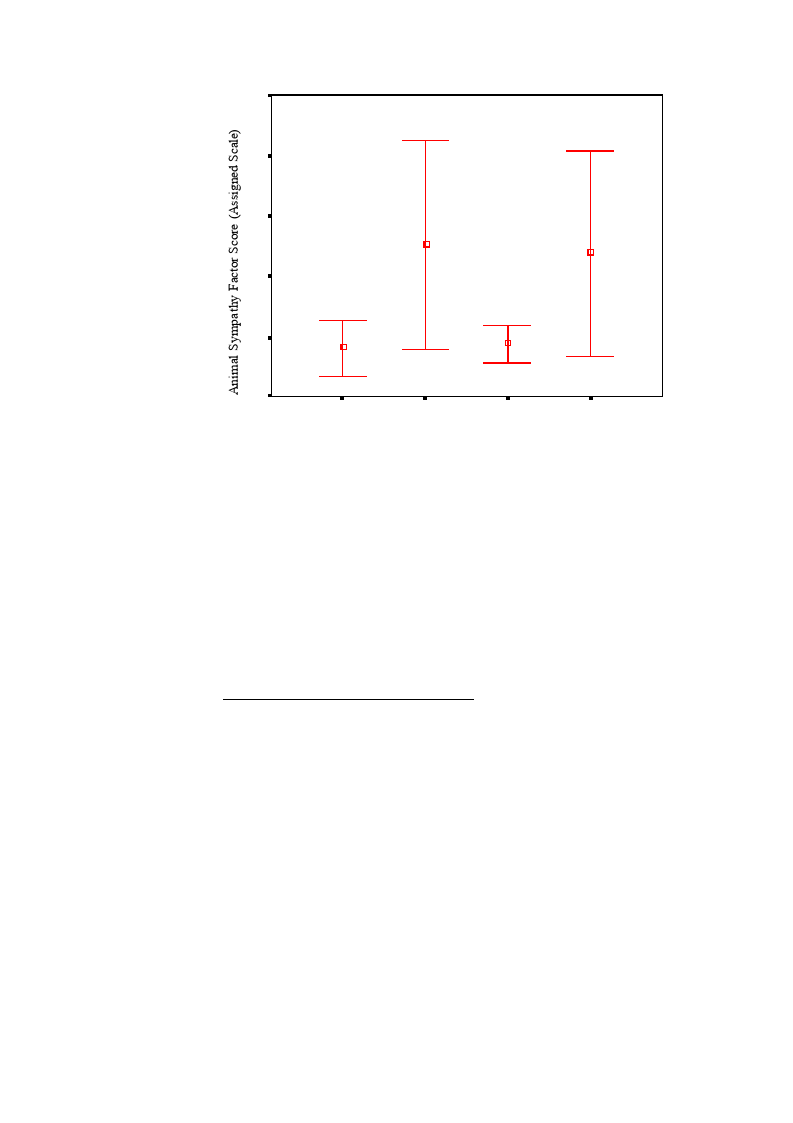

Figure 6.20: Animal sympathy factor score versus ecoparenting category .............................199

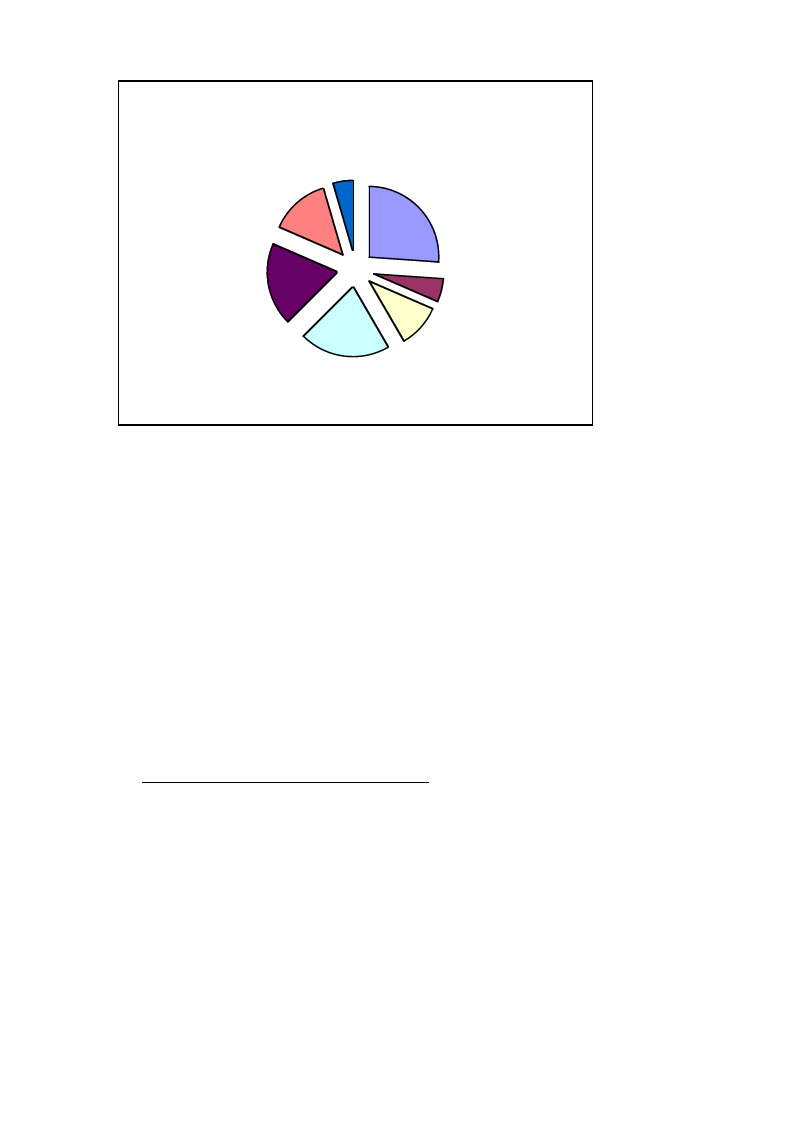

Figure 7.1 Favourite Nature Hobby (First Coder results).........................................................202

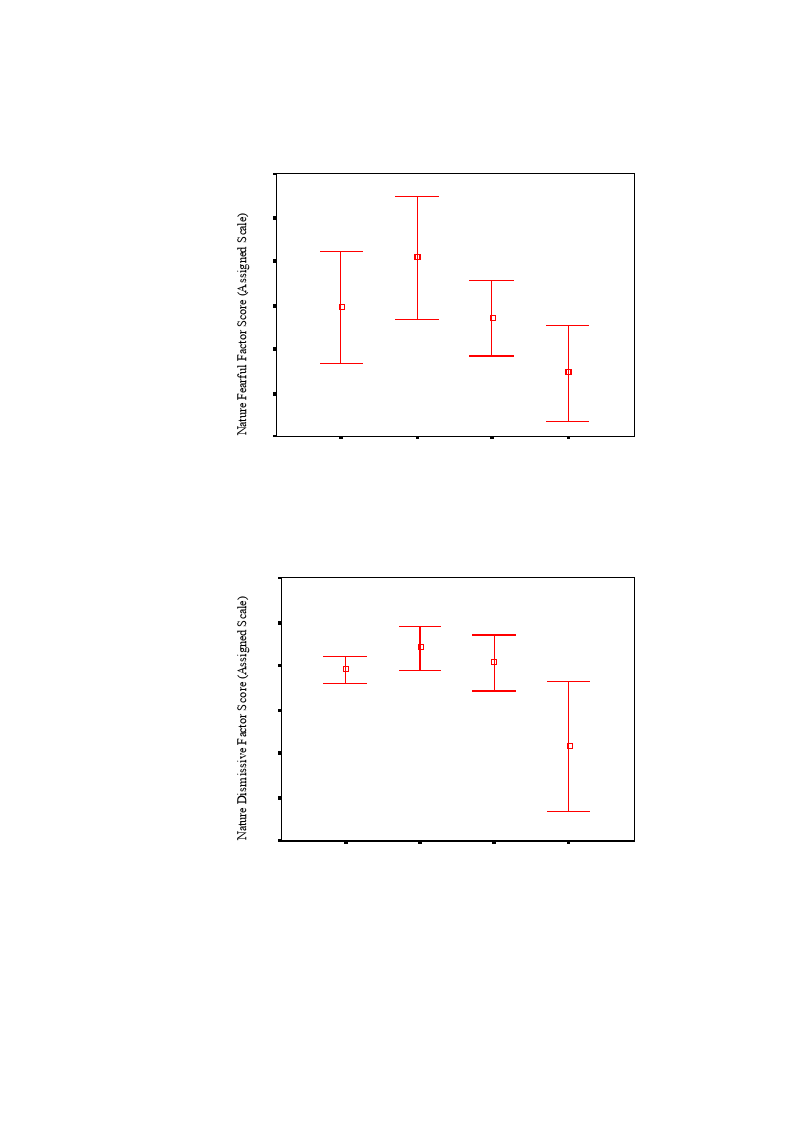

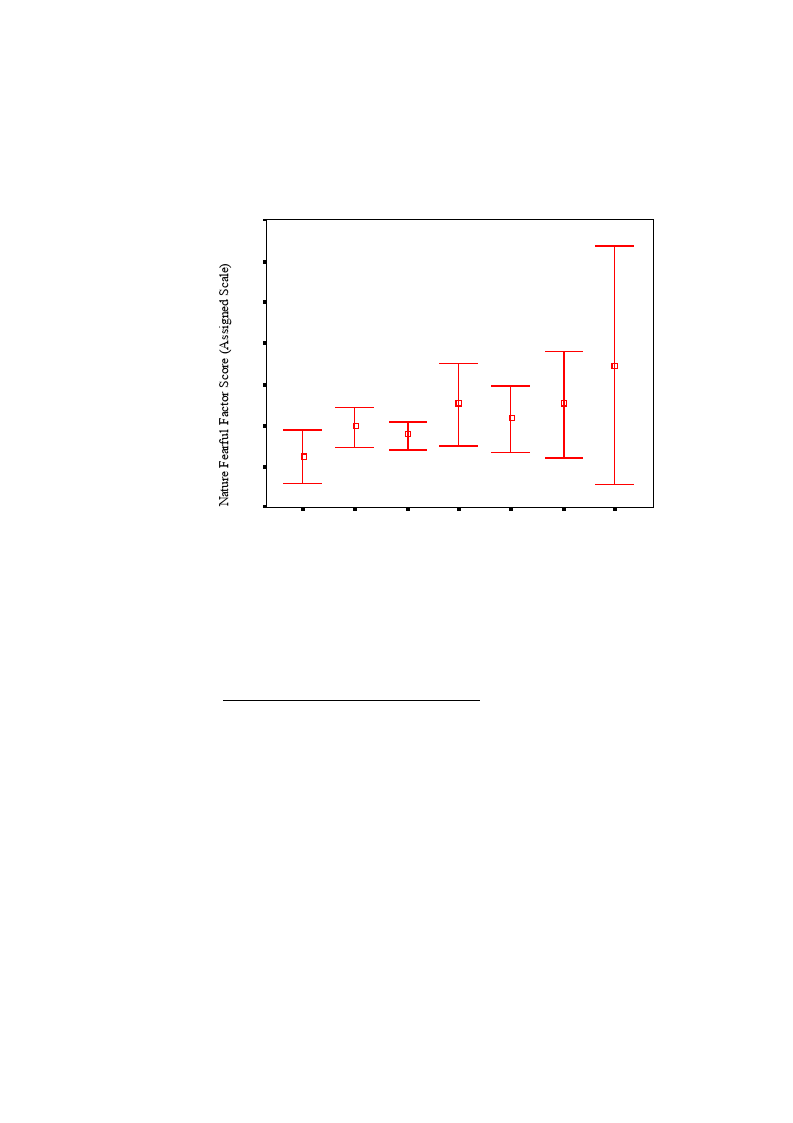

Figure 7.2: Nature fearful factor score versus number of mammal pet types..........................213

Figure 7.3: Nature dismissive factor score versus number of non-mammal pet types............213

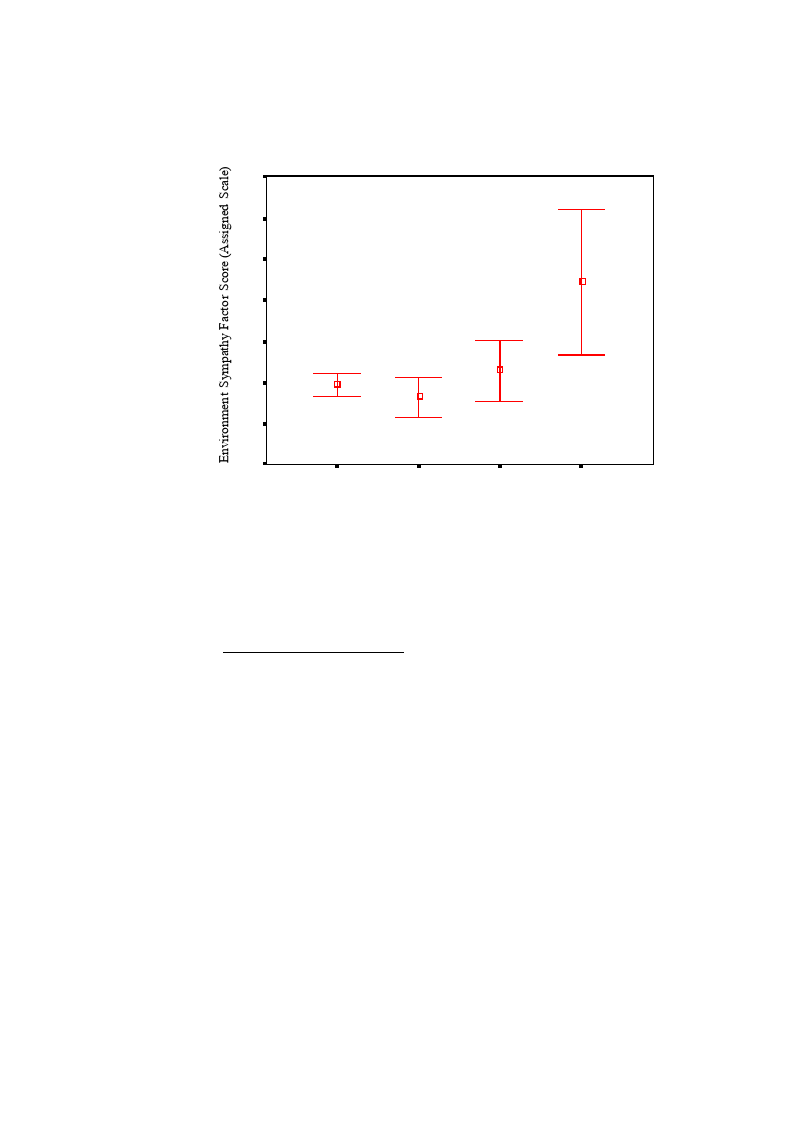

Figure 7.4: Environment sympathy factor score versus number of non-mammal pet types ...215

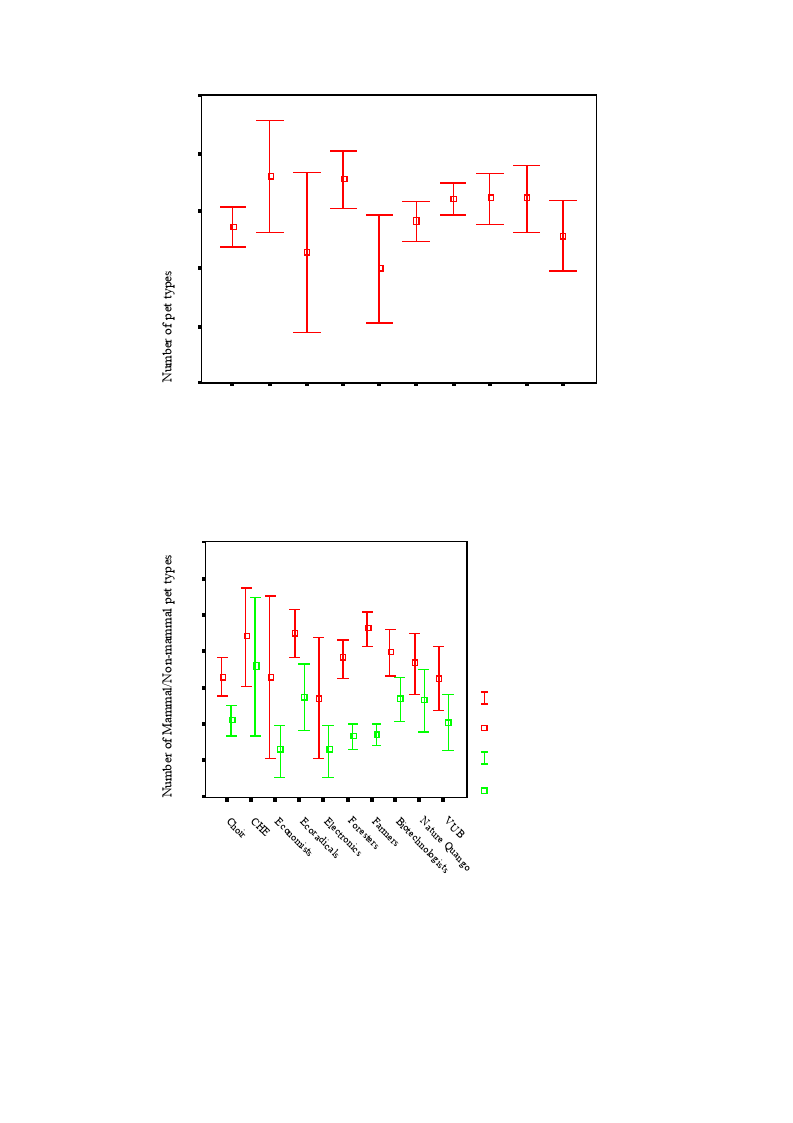

Figure 7.5: Number of pet types versus sample sub-groups.....................................................216

Figure 7.6: Number of mammal and non-mammal pet types versus sample sub-groups........216

Figure 7.7: Sample sub-group versus menagerie index ............................................................220

Figure 7.8: Adult residence versus menagerie index ................................................................220

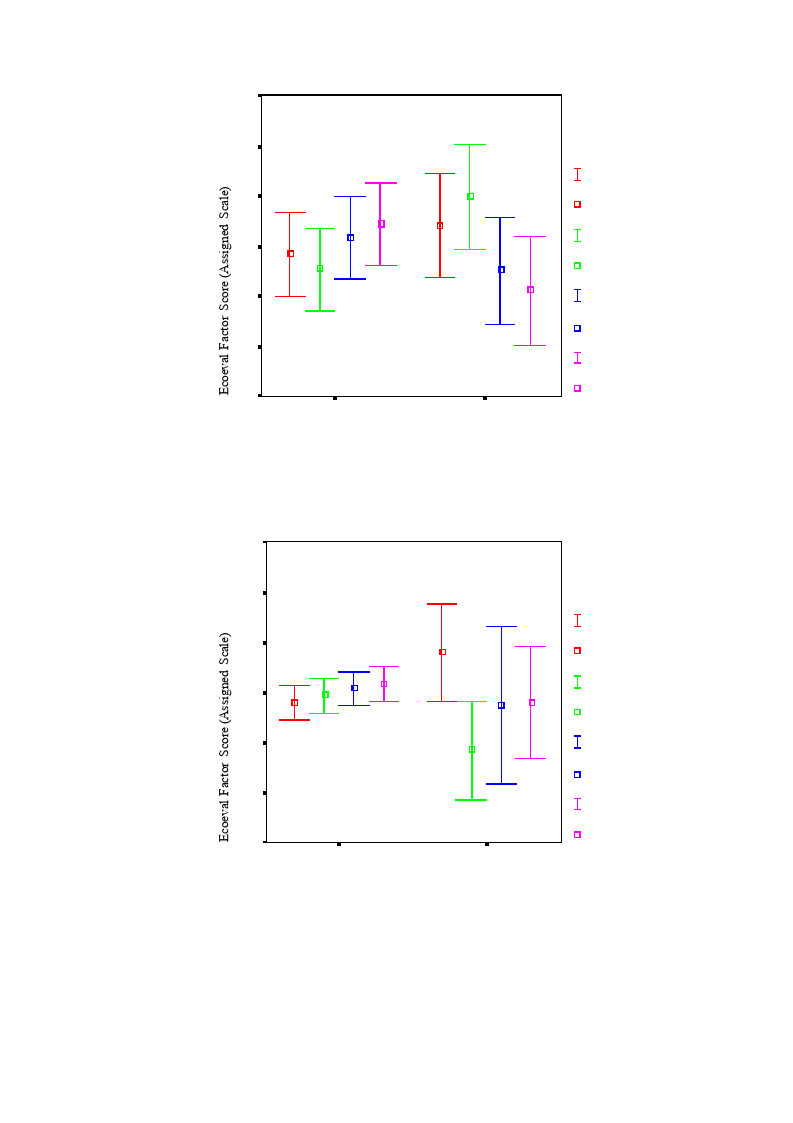

Figure 7.9: Child movement versus ecoevaluation factor scores .............................................222

xiv

Figure 7.10: Social class versus ecoemotionality factor nature fearful.................................... 225

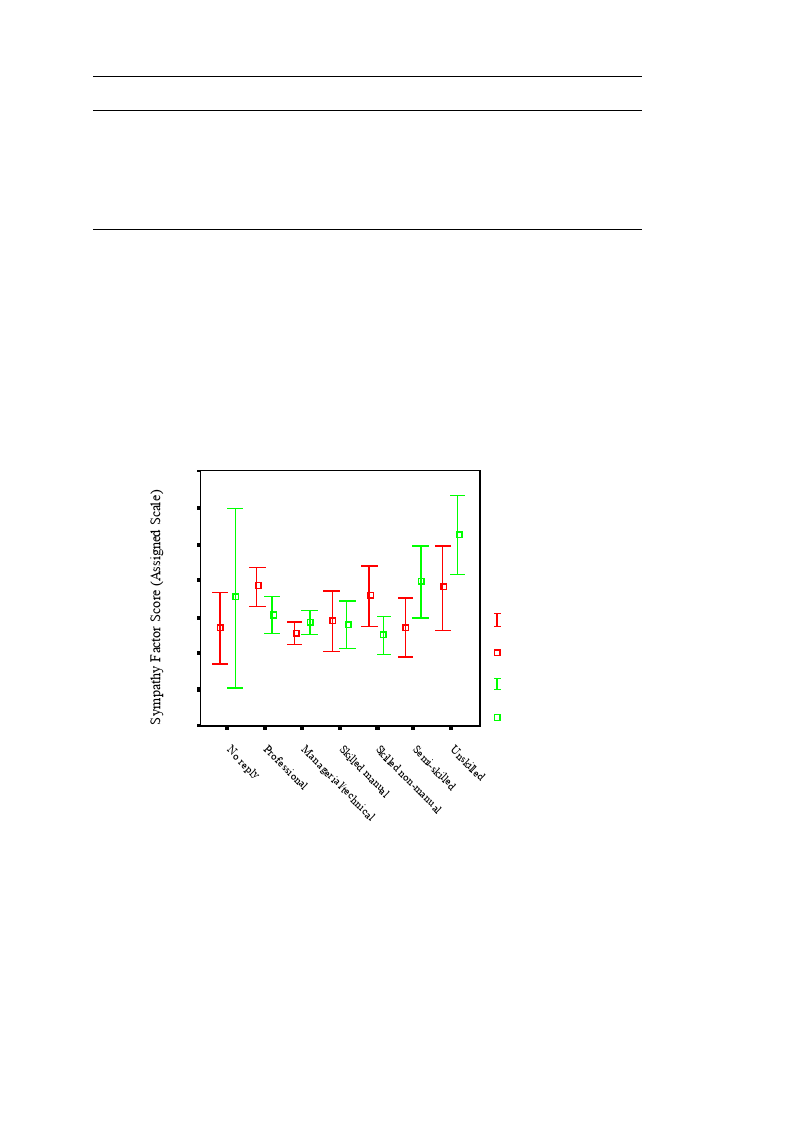

Figure 7.11: Social class versus relative sympathy factors environment and animal.............. 226

Figure 9.1: Proposed four category model of nature attachment ............................................. 278

Figure 9.2: Possible nature attachment model incorporating derived factors.......................... 280

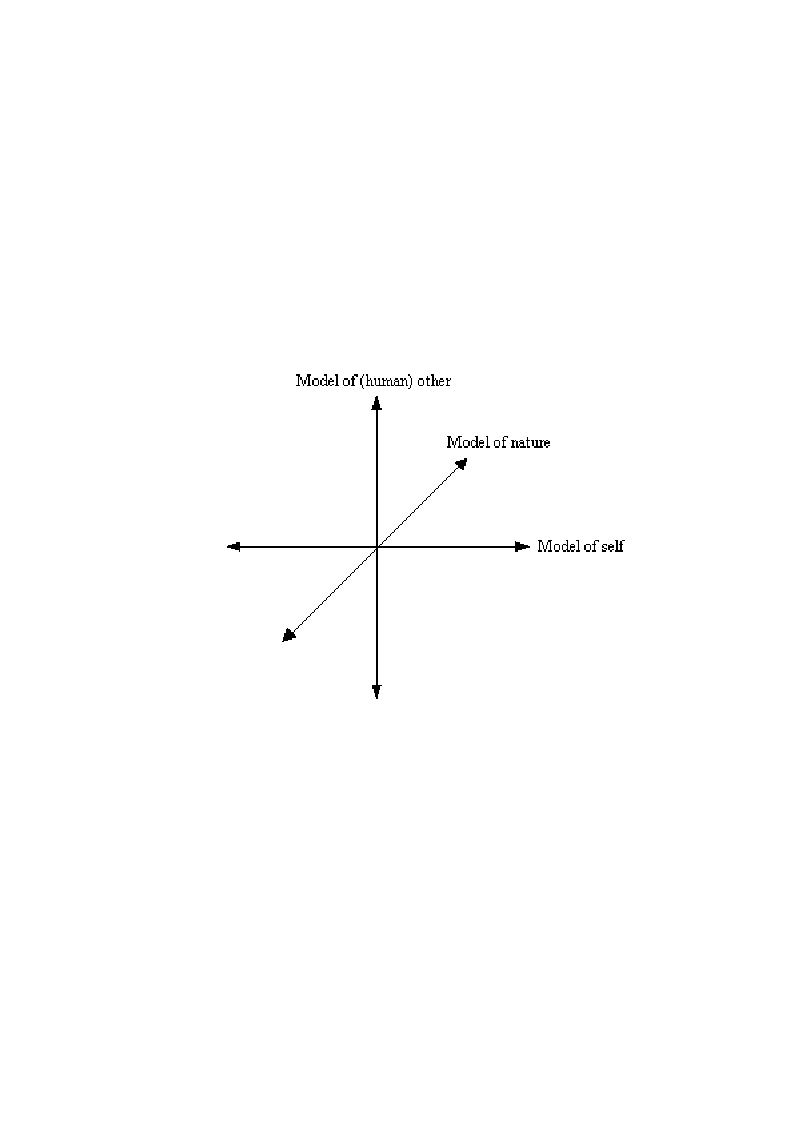

Figure 9.3: Speculative 3D model of human-nature attachment relations............................... 281

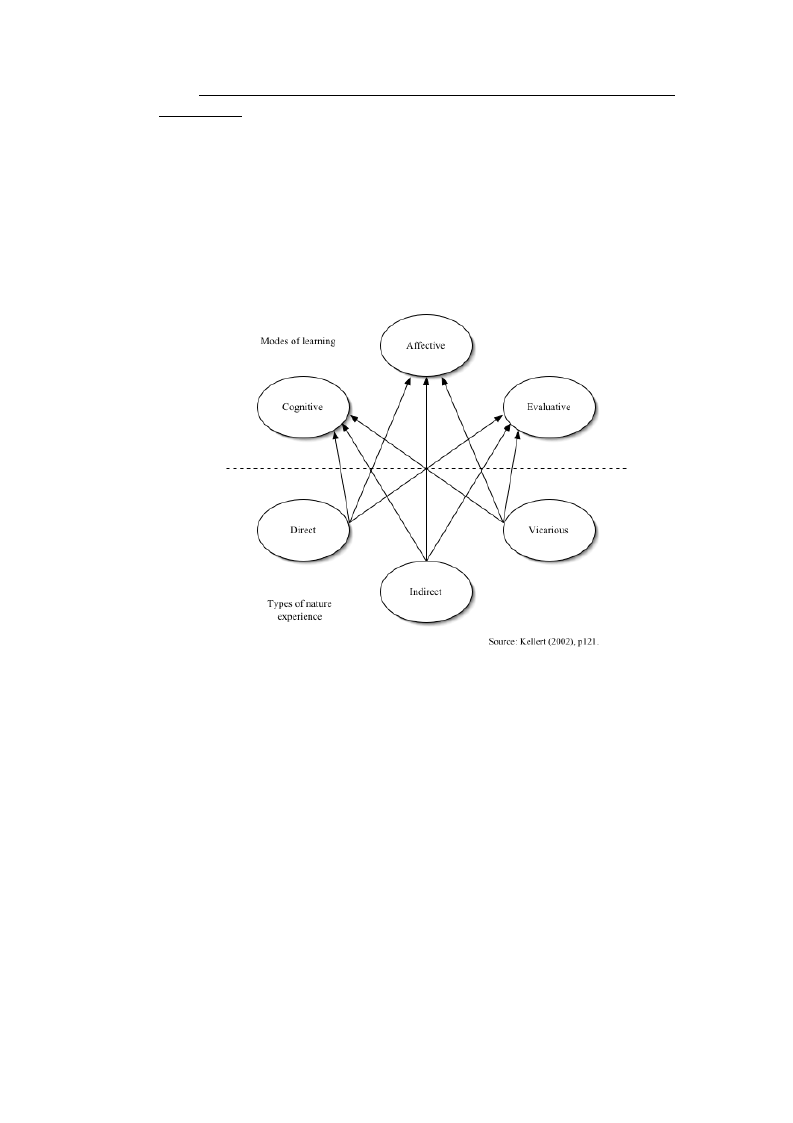

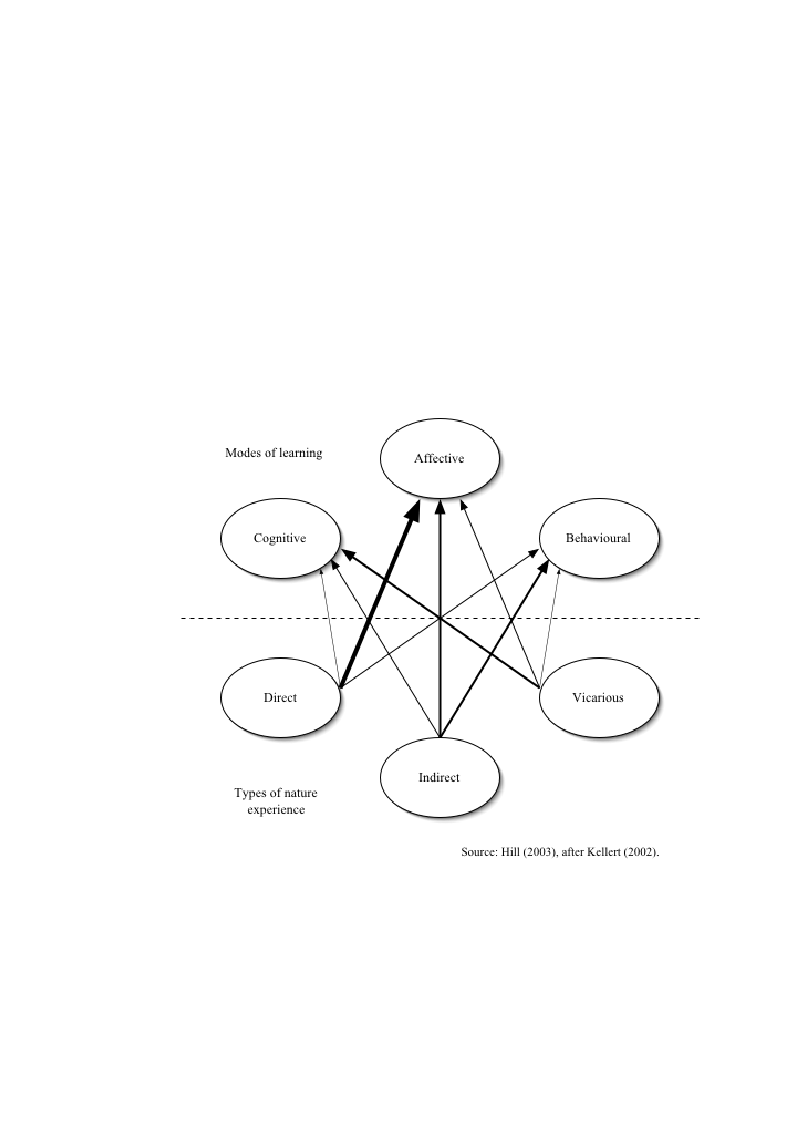

Figure 9.4: Types of nature experience and modes of learning ............................................... 283

Figure 9.5: Revised relationships between nature learning and experience ............................ 285

Figure 10.1: Cycle of enviromental-psychological deterioration............................................. 293

Figure 10.2: Proposed model for reversing anti-environmental culture .................................. 297

xv

Table of Tables

Table 2.1: Comparison of attachment model axes ......................................................................41

Table 5.1: Matrix of areas for investigation ..............................................................................104

Table 5.2: Questionnaire distribution and response rates .........................................................116

Table 5.3: Questionnaire distribution and return rates..............................................................117

Table 5.4: Distribution of residence ..........................................................................................118

Table 5.5: Full List of Simple and Derived Variables ..............................................................122

Table 5.6: List of Compound Variables and Coding Schemes.................................................123

Table 5.7: List of derived demographic variables.....................................................................142

Table 5.8: List of derived childhood variables..........................................................................144

Table 5.9: List of derived parental ecoactivity variables..........................................................145

Table 5.10: List of derived charitable giving variables ............................................................146

Table 5.11: List of derived adult ecoactivity variables.............................................................148

Table 5.12: List of derived outdoorsiness variables .................................................................149

Table 5.13: List of derived attachment variables ......................................................................150

Table 5.14: List of derived ecoevaluation variables .................................................................152

Table 5.15: List of derived ecoemotionality variables..............................................................153

Table 6.1: Paternal attachment status by ecoevaluation status .................................................155

Table 6.2: Correlations between paternal care and overprotection factor scores and

ecoevaluation factor scores................................................................................................156

Table 6.3: Maternal attachment status by ecoevaluation status................................................157

Table 6.4: Correlations between maternal care and overprotection factor scores and

ecoevaluation factor scores................................................................................................157

Table 6.5: Paternal attachment status by ecoemotionality status .............................................158

Table 6.6: Maternal attachment status by ecoemotionality status ............................................158

Table 6.7: Correlations between maternal care and overprotection factor scores and

ecoemotionality factor scores ............................................................................................159

Table 6.8: Paternal attachment status by relative sympathies ..................................................160

Table 6.9: Correlations between paternal care and overprotection factor scores and relative

sympathy factor scores ......................................................................................................160

Table 6.10: Maternal attachment status by relative sympathies...............................................160

Table 6.11: Correlations between maternal care and overprotection factor scores and relative

sympathy factor scores ......................................................................................................161

Table 6.12: Favourite place variables by parental attachment factor scores............................162

Table 6.13: Childhood residence by ecoevaluation factor scores ............................................168

Table 6.14: Childhood residence by ecoemotionality factor scores.........................................168

Table 6.15: Childhood residence by relative sympathy factor scores ......................................169

Table 6.16: Play by ecoevaluation factor scores.......................................................................172

Table 6.17: Play by ecoemotionality factor scores ...................................................................172

Table 6.18: Play by relative sympathy factor scores ................................................................174

Table 6.19: Wander by ecoevaluation factor scores .................................................................174

Table 6.20: Wander by ecoemotionality factors scores ............................................................175

Table 6.21: Wander by relative sympathy factor scores...........................................................176

Table 6.22: Favourite place variables by ecoevaluation factor scores .....................................178

Table 6.23: Favourite place variables by ecoemotionality factors scores................................181

Table 6.24: Favourite place variables by relative sympathy factor scores...............................184

Table 6.25: Age band versus play and wander..........................................................................187

Table 6.26: Parental ecoactivity by adult ecoevaluation factor scores.....................................191

Table 6.27: Parental ecoactivity by ecoemotionality factor scores ..........................................192

Table 6.28: Parental ecoactivity by relative sympathy factor scores .......................................193

Table 6.29: Nature mentor by adult ecoevaluation factor scores .............................................194

xvi

Table 6.30: Nature mentor by ecoemotionality factor scores................................................... 195

Table 6.31: Nature mentor by relative sympathy factor scores................................................ 196

Table 6.32: Ecoparenting by adult ecoevaluation factor scores ............................................... 197

Table 6.33: Ecoparenting by ecoemotionality factor scores..................................................... 198

Table 6.34: Ecoparenting by relative sympathy factor scores.................................................. 198

Table 7.1: Nature hobbies by ecoevaluation factor scores ....................................................... 203

Table 7.2: Nature hobbies by ecoemotionality factor scores.................................................... 204

Table 7.3: Nature hobbies by relative sympathy factor scores................................................. 205

Table 7.4: Nature media by ecoevaluation factor scores.......................................................... 206

Table 7.5: Nature media by ecoemotionality factor scores ...................................................... 207

Table 7.6: Nature media by relative sympathy factor scores ................................................... 208

Table 7.7: Nature child score by ecoevaluation factor scores .................................................. 209

Table 7.8: Nature child score by ecoemotionality factor scores .............................................. 209

Table 7.9: Nature child score by relative sympathy factor scores............................................ 210

Table 7.10: Pets by ecoevaluation factor scores ....................................................................... 211

Table 7.11: Pets by ecoemotionality factor scores.................................................................... 212

Table 7.12: Pets by relative sympathy factor scores................................................................. 214

Table 7.13: Menagerie and siblings by ecoevaluation factor scores........................................ 217

Table 7.14: Menagerie and siblings by ecoemotionality factor scores .................................... 218

Table 7.15: Menagerie and siblings by relative sympathy factor scores ................................. 219

Table 7.16: Child movements versus ecoevaluation factor scores........................................... 221

Table 7.17: Child movements by ecoemotionality factor scores ............................................. 222

Table 7.18: Child movements by relative sympathy factor scores........................................... 223

Table 7.19: Social class by ecoevaluation factor scores........................................................... 224

Table 7.21: Social class by relative sympathies factor scores.................................................. 226

Table 7.22: Education by ecoevaluation factor scores ............................................................. 227

Table 7.23: Education by ecoemotionality factor scores.......................................................... 228

Table 7.24: Education by relative sympathies factor scores .................................................... 228

Table 7.25: Adult home by ecoevaluation factor scores........................................................... 229

Table 7.26: Adult home by ecoemotionality factor scores....................................................... 230

Table 7.27: Adult home by relative sympathy factor scores .................................................... 230

Table 9.1: Characterisation of environmental memories.......................................................... 267

xvii

Acknowledgements

I should – as the joke runs – not have started this journey where I did. With the benefit of

hindsight I could have chosen an easier task than to attempt a thesis in an under explored

area in which I had little expertise, and to pursue it while working concurrently in

demanding jobs. I could and probably should have gone about it in a more disciplined

fashion and would in all likelihood have concluded it more rapidly, rather than the

wandering, serendipitous and glacial manner I have done. But whilst it has had its

downsides, as in so many things, the process has proven itself to be as important as the

product: it has been a baptism of fire, a befuddling maze, an apprenticeship of elephantine

gestation, a motivational test par excellence peppered with drowning feelings and,

occasionally, elation.

Though I have not answered all the questions I set, I feel I have done the original

conception justice, and discovered many potential enquiries I had not imagined. I am the

better for it: I only hope that in the fine tradition of the academy the half-dozen people who

get to read the average PhD find some part of these labours of benefit to their enquiries.

The list of those to whom I offer undying gratitude is long. Prime among them are my

supervisors Colwyn Trevarthen and Andy McKinley, for endorsement, tuition, insight and

serious patience. Others who have played an intellectual or supportive part, include: Sam

Graham (particularly encouragement in the last stretch), John Talbott and Ulrich Loening;

Jacqui Yelland who, in addition to much practical help, including transcribing virtually all

the scripts, shared insights and provoked challenging discussions; Tania Dolley who with me

wrote the first UK graduate ecopsychology course and delivered it with Hilary Prentice;

those who humbled me by pretending to be my students (particularly the ‘Unifying Concepts

of Ecology’ and ‘Ecopsychology’ classes of 1999-2002, my tutor groups and Masters thesis

supervisees: Dave, Gill, Chris P, Mandy, Tim, David B, Marie-Ange and Petra; Bob W and

Norah B for dedicated librarianship, and US intern Kathryn Bell). Bob Morris optimistically

facilitated this non-psychologist joining his venerable Department. Thanks also to those

groups, organisations and individuals that generously cooperated with my request for

participants, and the EU Survey Team, who gave helpful advice on the questionnaire.

Way back at the genesis of this project, the company of many Friends of Clayoquot

Sound (including Tzeporah, Valerie, Garth, Julie, Toby and Ron), and people from Tofino,

Ucluelet, UBC, Macmillan Bloedel and Interfor was inspirational (occurring only because of

kind assistance from Francesca and KZT). Karina, Martyn and Francoise raised interesting

issues. Kate S, Pete H and Wendy M helped me obtain timely teaching opportunities. My

thinking was affected by Jane, Peter and Chris at IDE UK and friends at the IDE US summer

schools (especially Batya Kagan), spells at Schumacher College, colleagues and contributors

at RS, members of the ecology-psychology list and ICE, the UK Ecopsychology Network,

Robin van Tine, Sylvie Shaw, Ted Roszak, Allen Kanner, Robert Greenway and all at the

Naropa 2000 meeting. Earlier formative life experiences came from knowing our King

Charles Cavalier Spaniels and other pets, from Rob M for early ‘green’ awareness, and from

Anna B for helping me understand the love of nature. DC, Andrew and families were

endlessly supportive and allowed me periodic tastes of normality at important moments.