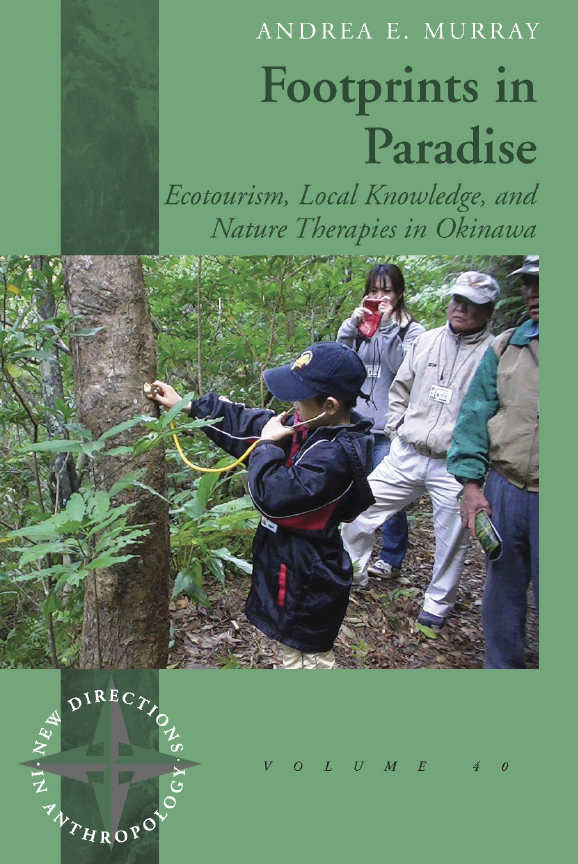

FOOTPRINTS IN PARADISE

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

New Directions in Anthropology

General Editor: Jacqueline Waldren, Institute of Social Anthropology, University of Oxford

Volume 1 Coping with Tourists: European Reactions

to Mass Tourism

Edited by Jeremy Boissevain

Volume 2 A Sentimental Economy: Commodity and

Community in Rural Ireland

Carles Salazar

Volume 3 Insiders and Outsiders: Paradise and

Reality in Mallorca

Jacqueline Waldren

Volume 4 The Hegemonic Male: Masculinity in a

Portuguese Town

Miguel Vale de Almeida

Volume 5 Communities of Faith: Sectarianism,

Identity, and Social Change on a Danish Island

Andrew S. Buckser

Volume 6 After Socialism: Land Reform and Rural

Social Change in Eastern Europe

Edited by Ray Abrahams

Volume 7 Immigrants and Bureaucrats: Ethiopians

in an Israeli Absorption Center

Esther Hertzog

Volume 8 A Venetian Island: Environment, History

and Change in Burano

Lidia Sciama

Volume 9 Recalling the Belgian Congo:

Conversations and Introspection

Marie-Bénédicte Dembour

Volume 10 Mastering Soldiers: Conflict, Emotions,

and the Enemy in an Israeli Military Unit

Eyal Ben-Ari

Volume 11 The Great Immigration: Russian Jews in

Israel

Dina Siegel

Volume 12 Morals of Legitimacy: Between Agency

and System

Edited by Italo Pardo

Volume 13 Academic Anthropology and the

Museum: Back to the Future

Edited by Mary Bouquet

Volume 14 Simulated Dreams: Israeli Youth and

Virtual Zionism

Haim Hazan

Volume 15 Defiance and Compliance: Negotiating

Gender in Low-Income Cairo

Heba Aziz Morsi El-Kholy

Volume 16 Troubles with Turtles: Cultural

Understandings of the Environment on a Greek Island

Dimitrios Theodossopoulos

Volume 17 Rebordering the Mediterranean:

Boundaries and Citizenship in Southern Europe

Liliana Suarez-Navaz

Volume 18 The Bounded Field: Localism and Local

Identity in an Italian Alpine Valley

Jaro Stacul

Volume 19 Foundations of National Identity: From

Catalonia to Europe

Josep Llobera

Volume 20 Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory and

the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus

Paul Sant Cassia

Volume 21 Who Owns the Past? The Politics of Time

in a ‘Model’ Bulgarian Village

Deema Kaneff

Volume 22 An Earth-Colored Sea: ‘Race’, Culture

and the Politics of Identity in the Postcolonial

Portuguese-Speaking World

Miguel Vale De Almeida

Volume 23 Science, Magic and Religion: The Ritual

Process of Museum Magic

Edited by Mary Bouquet and Nuno Porto

Volume 24 Crossing European Boundaries: Beyond

Conventional Geographical Categories

Edited by Jaro Stacul, Christina Moutsou and

Helen Kopnina

Volume 25 Documenting Transnational Migration:

Jordanian Men Working and Studying in Europe,

Asia and North America

Richard Antoum

Volume 26 Le Malaise Créole: Ethnic Identity in

Mauritius

Rosabelle Boswell

Volume 27 Nursing Stories: Life and Death in a

German Hospice

Nicholas Eschenbruch

Volume 28 Inclusionary Rhetoric/Exclusionary

Practices: Left-wing Politics and Migrants in Italy

Davide Però

Volume 29 The Nomads of Mykonos: Performing

Liminalities in a ‘Queer’ Space

Pola Bousiou

Volume 30 Transnational Families, Migration, and

Gender: Moroccan and Filipino Women in Bologna

and Barcelona

Elisabetta Zontini

Volume 31 Envisioning Eden: Mobilizing

Imaginaries in Tourism and Beyond

Noel B. Salazar

Volume 32 Tourism, Magic and Modernity:

Cultivating the Human Garden

David Picard

Volume 33 Diasporic Generations: Memory, Politics,

and Nation among Cubans in Spain

Mette Louise Berg

Volume 34 Great Expectations: Imagination,

Anticipation and Enchantment in Tourism

Jonathan Skinner and Dimitrios

Theodossopoulos

Volume 35 Learning from the Children: Childhood,

Culture and Identity in a Changing World

Edited by Jacqueline Waldren and Ignacy-

Marek Kaminski

Volume 36 Americans in Tuscany: Charity,

Compassion and Belonging

Catherine Trundle

Volume 37 The Franco-Mauritian Elite: Power and

Anxiety in the Face of Change

Tijo Salverda

Volume 38 Tourism and Informal Encounters in

Cuba

Valerio Simoni

Volume 39 Honour and Violence: Gender, Power

and Law in Southern Pakistan

Nafisa Shah

Volume 40 Footprints in Paradise: Ecotourism,

Local Knowledge, and Nature Therapies in Okinawa

Andrea E. Murray

Volume 41 Living Before Dying: Imagining and

Remembering Home

Janette Davies

Volume 42 A Goddess in Motion: Visual Creativity

in the Cult of Maria Lionza

Roger Canals

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

FOOTPRINTS IN PARADISE

Ecotourism, Local Knowledge,

and Nature Therapies in Okinawa

Andrea E. Murray

berghahn

NEW YORK • OXFORD

www.berghahnbooks.com

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

First published in 2017 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

© 2017 Andrea E. Murray

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages

for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book

may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information

storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented,

without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Murray, Andrea E.

Title: Footprints in paradise : ecotourism, local knowledge, and nature therapies in

Okinawa / Andrea E. Murray.

Description: New York : Berghahn Books, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references

and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017010903 (print) | LCCN 2017015913 (ebook) |

ISBN 781785333873 (eBook) | ISBN 9781785333866 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Ecotourism—Japan—Okinawa Island. | Economic development—

Japan—Okinawa Island. | Traditional ecological knowledge—Japan—Okinawa Island.

Classification: LCC G155.J3 (ebook) | LCC G155.J3 M87 2017 (print) |

DDC 338.4/79152294—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010903

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78533-386-6 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-78533-473-3 (open access ebook)

An electronic version of this book is freely available thanks to the support of libraries

working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make

high quality books Open Access for the public good. More information about the ini-

tiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at knowledgeunlatched.org.

is work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution

Noncommercial No Derivatives 4.0 International license. e terms of the

license can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

For uses beyond those covered in the license contact Berghahn Books.

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

For my grandparents, Jo and Winston Murray,

who taught me the value of good old-fashioned hard work

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Figures

viii

Preface

x

Acknowledgments

xi

Introduction: “We want them to know nature!!”

1

Chapter One: Okinawa’s Tourism Imperative

15

Chapter Two: Slow Vulnerability in Okinawa

29

Chapter Three: Knowing and Noticing

62

Chapter Four: Ecologies of Nearness

79

Chapter Five: Healing and Nature

114

Conclusion: Yambaru Funbaru!

151

References

156

Index

167

vii

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 0.1 Map of Okinawa Island, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan

13

Figure 1.1 Map of U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa

19

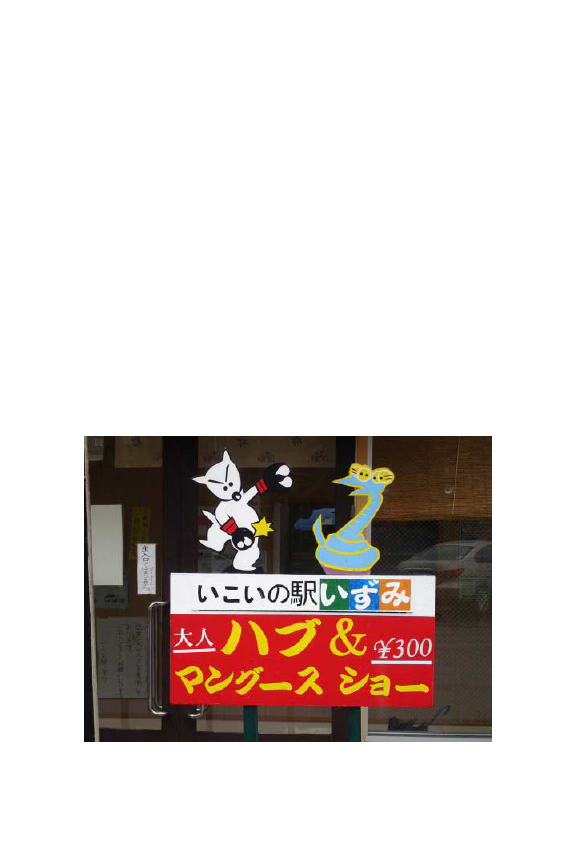

Figure 2.1 Advertisement for Habu-Mongoose Show, Nago

31

Figure 2.2a Giant Yambaru Kuina, Churaumi Aquarium, Motobu 36

Figure 2.2b Kuina in Training, Tourism Welcome Center, Kunigami 36

Figure 2.2c Cuddly Kuina Mascot at Waterfowl Festival, Naha

37

Figure 2.2d Crying Kuina, Kunigami

37

Figure 2.3a “Mongoose Northward Prevention Fence,” Yonabaru

Forest, Kunigami

39

Figure 2.3b Ministry of Environment “Mongoose Busters”

Extermination Program Logo

39

Figure 2.4 Tourist Habu-Mongoose T-Shirt: “A Battle of Legend”

41

Figure 2.5 Okinawan Agrotourists Harvest Sugarcane, Itoman

47

Figure 2.6 Agrotourists Operate Sugarcane Press, Itoman

48

Figure 3.1 Northern Okinawans Dine and Chat During

Community Gathering, Kunigami

67

Figure 4.1 Dolphins Kiss in Caricature at Wellness Village, Motobu 87

viii

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

List of Figures

Figure 4.2 “Restaurant Flipper” Invokes Okinawan Culinary

Tradition, Nago

92

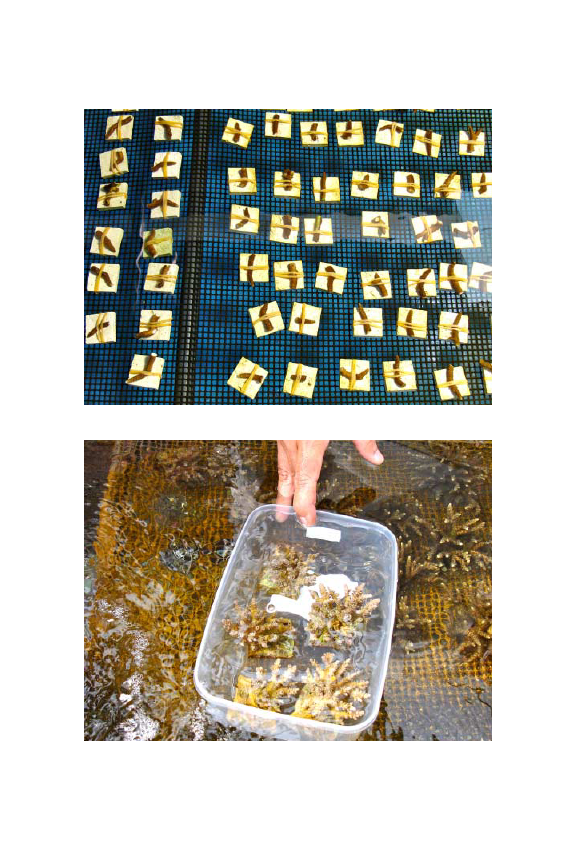

Figure 4.3a Volunteer Coral Gardeners on Land, Ginowan

106

Figure 4.3b Coral Polyp Transplants (3 months)

107

Figure 4.3c Coral Polyp Transplants (6 months)

107

Figure 4.3d Volunteer Coral Gardeners at Sea, Ginowan

108

Figure 5.1 Okinawans Do Forest Therapy, Yonabaru Forest

114

Figure 5.2 Flier for Okinawans: “Treasure Box” Nature Games

119

ix

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

PREFACE

Social and political life on small subtropical islands is frequently shaped by

the economic imperative of sustainable tourism development. In Okinawa,

“ecotourism” promises to provide employment for a dwindling population

of rural youth while preserving the natural environment and bolstering re-

gional pride. In this volume, I consider how new subjectivities are produced

when host communities come to see themselves through the lens of the visit-

ing tourist. I further explore how Okinawans’ sense of place and identity are

transformed as their language, landscapes, and wildlife are reconstituted as

cherishable yet vulnerable resources.

I present a case study of how local ecological knowledge moves inter-gen-

erationally (between Okinawan elders and youth) and cross-culturally (be-

tween Okinawan nature guides and international and mainland Japanese

tourists, the latter being often also considered “foreign”). By tracing the for-

mal and informal social networks through which specific attitudes, beliefs,

and sensibilities about the environment are circulated and reproduced, I

demonstrate how nature-based therapies marketed to tourists for stress relief

and lifestyle rehabilitation (e.g., forest therapy, dolphin therapy, and coral

gardening) also influence Okinawan attitudes toward health and wellness.

These kinds of activities reconfigure human relationships with nonhuman

animal species: creatures previously “good to eat” (Harris 1985) are now

even better to heal.

Sustainability in Okinawa always begins with the question of military

bases. The ecotourism concept poses a compelling, if problematic, economic

alternative to the expansion of U.S. bases into northern Okinawa, the hub

of environmentally oriented conservationist, educational, and tourist pro-

grams on the main island. My analysis of the ecological and cultural effects

of sustaining the tourism industry in Okinawa speaks to small islands facing

similar economic and environmental challenges in East Asia, the Caribbean,

Oceania, and beyond.

x

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My deepest gratitude goes out to the wealth of friends, family members, and

colleagues who have helped me to generate, investigate, and ultimately com-

plete this project over the last decade. Chapter 1 was conceived with the help

of Sarah Vaughn, Goutam Gajula, Shafqat Hussain, and Anand Pandian

through a panel on “Vulnerability’s Ethical Engagements and Traces” held

at the American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting in November

2011. My colleague Rheana (Juno) Parreñas’s work on rehabilitant orang-

utans in Malaysia inspired me to consider nonhuman animal histories in

relation to human vulnerability in Chapter 2. Countless words of thanks to

Lisanne Norman and Jennifer Mack for patiently reading, editing, and cri-

tiquing every line of every chapter as they first emerged, and to Dr. Norman

for her continued editing of the manuscript as it developed. I would have

been completely lost without tracking your changes!

Sarah Kashani and Fumi Wakamatsu supported my conceptual thinking

on Japan, while the members of the Political Ecology and Reischauer Insti-

tute of Japanese Studies Working Groups provided invaluable feedback every

time we met to workshop our writing. My dear friends Illiana Quimbaya,

Sarah Kashani, Jennifer Mack, Cynthia Browne, Bridget Hanna, Aquene

Freechild, H’Sien Hayward, Alison Hillegeist, Annie Turner, and Ruthe

Farmer kept me afloat when I struggled most. Megan Scheminske, your

graphic design skills are uncrushable! My fantastic officemates Kristin Wil-

liams, Esra Gokce Sahin, Jeremy Yellen, Christopher Leighton, Hiromu

Nagahara, Raja Adal, and Jennifer Yum were always available with ample

empathy as we typed, typed, typed, in a row, day and night, Monday through

Sunday. Your humor and support were a breath of fresh air, and you know

exactly how precious oxygen was in our office.

I could not have conducted my fieldwork without the kindness and gen-

erosity of Professors Junko Ōshima and Katsunori Yamazato, and Ms. Kaori

Kinjō from the University of the Ryukyus. The incredible kindness shown

to me by my formal (and informal) advisors at Meio University—Profes-

sors Yūji Arakaki and Sumiko Ōgawa, and Dr. Eugene Boostrom—kept me

xi

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Acknowledgments

healthy and at home in Okinawa. My dear healing friend, Yuri Arakaki, my

loving host mother Yoshiko Nakasone, and her wonderful niece Mutsuko

Inafuku enriched an often isolating fieldwork experience by making me feel

welcome, always. “Weasel” the wily translator: Thank you for your sense of

humor about my fieldwork.

At Harvard, Marianne Fritz, Cris Paul, Susan Farley, Amy Zug, and Su-

san Hilditch helped me to keep perspective as I struggled to clear the steep

hurdles set by the Department of Anthropology and GSAS. The endless ef-

forts of these fantastic women offer the finest argument for “Staff not Stuff!”

To my cohabitants Chris Mosier and Chenzi Xu: Our lively conversations

brought me much-needed levity during one of the most stress-filled years of

my life. Anne Allison, Diane Nelson, Deborah Thomas, and John L. Jack-

son, Jr.: Thank you for turning me on to the weird world of Anthropology

when I was most impressionable. Kimberly Theidon, thank you for helping

me to persevere when I was most discouraged.

The Department of Anthropology, the Reischauer Institute of Japanese

Studies, and the Harvard Asia Center generously supported my preliminary

summer fieldwork, as well as my participation in the Japanese language

schools and academic conferences that helped me to refine my research ques-

tions. Special thanks to Ted Gilman and Stacey Matsumoto for affording

me the many perks of being a Graduate Student Associate at RIJS (twice!).

The Fulbright Institute of International Education made my fieldwork pos-

sible despite some very difficult circumstances, and I am forever indebted to

Dr. David Satterwhite and the staff at the Japan–United States Educational

Commission in Tokyo for their tremendous support and flexibility through-

out the daunting health challenges I faced during fieldwork. My heartfelt

thanks go to Jackie Waldren for being such an inspiring friend and mentor to

me over the past decade. Without your encouragement this Berghahn Book

would not exist.

My thesis committee members each brought a different intellectual and

disciplinary gift to the table: Michael Herzfeld, you pushed me to write,

write, write, and write some more when I was blocked and despairing, and

you offered thoughtful encouragement when I needed it most. Steven Ca-

ton, you validated my unconventional writing style while gently reminding

me that I still needed to make an argument. Ian Miller, your enthusiasm

for my topic kept me engaged when my own thoughts were moving from

critical to cynical. Thanks to you, I finally have the confidence to show my

historiography to a real historian! Ted Bestor, as my advisor, friend, and sur-

rogate family in Cambridge, you and Vickey have constantly reminded me

why I became an anthropologist. You have shown me a kindness that extends

worlds beyond anything I could have imagined when I first came to big,

xii

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Acknowledgments

scary Harvard University. You have both seen me through the raw and the

cooked, and I will never forget your generosity. Thank you.

Thank you to my sister, Lauren Sullivan, and to my father, Michael

Murray, for keeping the faith—in me. Jennifer “Mama Jen” Desmond: You

rescued me many times throughout graduate school and during my tumul-

tuous time in Japan. I am so grateful to you for your unfailing love and

support, always. You are also owed an honorary doctorate for your thought-

ful, real-world contributions aimed at making this project make sense.

Philip Klinkner, thank you for bringing me home after a very long journey.

I love you.

xiii

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

INTRODUCTION

“We want them to know nature!!”

Our guide’s impassioned explanation of his primary objective was lost on

most of the sunburned ecotour group I had joined for an afternoon of man-

grove kayaking in Higashi, one of Okinawa Island’s northernmost villages.

We sat in a circle on straw tatami mats, sheltered at last from a blazing July

sun by the red-tiled roof of a traditional Okinawan house built on sturdy

stilts to welcome rare cool breezes blowing through. An exhausted, hungry

group of ecotourists dug eagerly into a bowl full of saataa andaagii, black

sugar and pineapple-flavored “Okinawa donuts,” and chugged hibiscus tea.

Our guide, “Cha-chan,”1 a twenty-something Okinawan outdoor enthusiast

nicknamed after brown tea leaves for his year-round tan, told us about his

desire to “teach” nature, along with a bit of Okinawan history and culture,

on every tour he conducted.

His boss, Mr. Miyagi, a generation or two older and noticeably less tan,

sat on the opposite side of the floor table we were gathered around. Miyagi

interjected that the Higashi Nature School’s goals were also practical: “Of

course, our first objective is to improve the economic health of the area.

Agriculture does not appeal to the younger generations, so we bring in third

sector business and industry to retain and attract young people.”

Cha-chan was one of many self-declared “nature lovers” I met during fif-

teen months of fieldwork in the Japanese prefecture of Okinawa. He spoke

of the need to retain the rich biodiversity of northern ecosystems, symboli-

cally including himself when he told me: “I never want to be separated from

this place!” His boss, director of the Higashi Tourism Promotion Associa-

tion, was also a nature enthusiast but focused more on how to sustain the

livelihood of young guides like Cha-chan by continuing to attract the twenty

thousand mainland Japanese tourists who annually visit his hometown of

Higashi, a village with only two thousand permanent residents. Since the

late 1990s, the Higashi Nature School has grown to become northern Oki-

nawa’s model of success in promoting the “ecotourism” concept to visiting

1

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

tourists, and to a predominantly pineapple-farming community not yet ac-

customed to having large tour buses full of Japanese homestay students flood

their rivers, forests, and living rooms.

Miyagi’s description of the dramatic shift in local labor away from the

sun, sweat, and dirt afforded by the primary experience of farming, toward

the more tertiary sun, sweat, and dirt supplied by guiding ecotours, indi-

cates that tourists are not the only population to experience something pro-

foundly new and different when they don a wetsuit to dive deeper into the

ocean, or enter a subtropical forest to listen for the call of rare birds. When

I asked him whether the growth of ecotourism in Higashi had changed lo-

cal attitudes toward nature, Miyagi replied without hesitating: “Not much.

It hasn’t yet. The locals only see the money. It’s easy to see business. Then

again, people have begun to really want to show a nice clean town to visitors

for profit purposes, and this has had a good effect on the environment. The

attitudes will change from now on.”

This book is an attempt to see, notice, and know how “Nature” is con-

structed and reconstituted as a cultural, economic, and touristic resource

in Okinawa. Looking through the lens of Japanese and international eco-

tourists while tracing the footprints of their Okinawan nature interpreters, I

present a case study of how knowledge about the environment is localized,

packaged, and reproduced for tourist consumption in northern Okinawa as

part of a much larger Japanese state project promoting village revitalization.

The economic and social transformation of the northern Yambaru Area of

Okinawa Island—from an “inconvenient countryside” and a “harsh place

with only mountains” (Ministry of Environment 2008: 2) into a biodiver-

sity hotspot that hosts nearly 25 percent of Japan’s plant species and four of

Japan’s twelve endemic animals—redefines the environmental sensibilities of

visitors and residents alike.

I consider the touristic, activist, and educational initiatives through which

Okinawans express and promote their archipelago’s specific environmental

concerns to visitors while forging new touristic enterprises to sustain local

economies. The binarizing social and analytical categories of visitor/visited,

local/expert, insider/outsider, and host/guest frequently deployed in anthro-

pological studies of tourism2 are both reproduced and transcended in Oki-

nawa. Multiple forms of naturalized touristic encounters between humans

and other humans, and between humans and nonhuman forms of life are

made visible through ecotourism and other facilitated experiences of nature.

The nature of these experiences calls into question the location and limits of

the natural environment that local guides and visiting tourists seek to expe-

rience, encouraging new theoretical perspectives on why we are compelled

to get closer to “green.” In Okinawa, knowing nature—even loving it—is a

matter of interpretation.

2

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Introduction

Locating the Ecotourist: Theoretical Questions

As a typical Japanese tourist in Okinawa, you would probably arrive in Jan-

uary, March, or August with your spouse and 1.25 children, drop your lug-

gage at one of Japan Airlines’ luxurious, all-inclusive beachfront hotels, and

instruct your pre-programmed GPS-equipped rental car to take you straight

to three of the most popular tourist sites: Okinawa Peace Memorial Park; an

enclosed cultural theme park such as Okinawa World; and Churaumi, the

world’s second-largest aquarium. You might collect a few kariyushi “happi-

ness” Hawaiian shirts for your co-workers and some pit viper–infused awam-

ori liquor before finally hitting the beach, where you could partake in marine

leisure sports such as snorkeling or a one-time fun dive. You would allot ap-

proximately 2.5 days to see, do, and buy it all before flying back to Tokyo to

return to work, and your fond memories might not include any Okinawans.

For a middle-class family embarking on its first big trip, the practical

appeal of taking a “quasi-overseas trip to quasi-foreign, quasi-tropical” (Figal

2012: 122) Okinawa would likely include the ease of speaking Japanese and

spending yen, minimal travel time (about four hours by plane from Tokyo

to Naha), and affordable amenities.

These stereotypes of Japanese patterns of domestic tourism3 are well-worn

territory, among both tourists (5.7 million visited Okinawa in 2009), and

anthropologists of Japan (e.g., Graburn 1989; Hendry 1995; Ivy 1995). An-

thropologists have tended to frame their studies of tourism in terms of the rit-

ual and religious origins of tourism (Graburn 1983), the marketing of village

tourism to urban Japanese (Ivy 1995; Robertson 1991), or the negative social,

cultural, and environmental effects of village tourism (Moon 1997, 1998).

Whether explaining the historical roots of contemporary Japanese modes

of travel (Graburn 1983) or analyzing the relationship between nostalgia and

national identity at play in domestic village travel (Robertson 1988), anthro-

pologists of Japan have tended to study domestic tourism from the perspective

of the tourist guest. Common scholarly assumptions that tourism has been

“imposed on locals, not sought, and not invited” (Stronza 2001: 262) have im-

peded a full understanding of why host communities engage in tourism in par-

ticular ways. Studies of recipient communities have criticized the deleterious

social and environmental effects of tourism caused by the commodification of

nature (Moon 1997: 222) without fully considering the financial, cultural, and

community benefits that locals may also derive from actively studying their

surroundings and sharing certain aspects of their lives with outsiders.

Marilyn Ivy points out that “those who are living continuously in the

place where they were born do not call that place furusato [old village or

native place]” (Ivy 1995: 103). I contribute to the anthropology of Okinawa

by asking how nostalgia operates for Okinawan hosts engaged in ecotourism

3

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

in northern towns such as Ōgimi, where a giant carved banner greets visitors:

“Welcome to the long-living furusato!” Chris Nelson’s (2008: 24) ethnogra-

phy of Okinawan popular performers provides insight into how the trope

of the idyllic Okinawan past both attracts visitors “in search of an authentic

experience of a lost Japan” and incites the postwar “will to memory” among

the performers. Okinawan nature interpreters (including young novices and

experienced retirees) also reify these discourses of loss through storytelling

and performance when leading tours.

The existing literature on Japan provides useful theoretical frameworks

for understanding how domestic tourism supports rural areas struggling

with depopulation and stagnant economies (Ivy 1988, 1995; Moon 1997;

Siegenthaler 1999) and creates educational opportunities for tourist “pil-

grims” (Graburn 1983). Yugo Ono’s (2005) study of Ainu ecotourism and

cultural heritage advocacy in Hokkaido demonstrates how one of Japan’s

ethnic minority groups can mobilize the natural resources of the countryside

to supplement previously established rural industries such as rice cultiva-

tion, fishing, and logging. While recent scholarship dedicated to the political

ecology of global tourism begins to cover more territory (cf. Mostafanezhad

et. al 2016), ecotourism in East Asia has been largely overlooked by social

scientists. Previously one had to journey to a Tanzanian island marine park

(Walley 2004), a Costa Rican rainforest (Vivanco 2006), or an Indonesian

island (Lowe 2006) to find a critical ethnographic examination of the com-

modification of the environment (Walsh 2012) through ecotourism.

Ecotourism is most commonly associated with the hyper-naturalized

imaginary of the “Global South” (this term refers to countries such as Costa

Rica, Kenya, and Brazil), but over the last twenty years national parks and

nature preserves throughout the United States, Europe, Australia, and Japan

have also begun to adopt the concept. Through a politics of nature Laura

Ogden (2011: 96) regards as “ecological fame-making,” northern Okinawa’s

Yambaru forests, for example, are now comparable to Costa Rica’s Monte

Verde, a veteran “biodiversity hot spot” (Vivanco 2006: 10) that contains

5 percent of the world’s floral and faunal species. Every ten square kilometers

of Okinawa is more than “twenty times richer” (McCormack 1999: 262)

than equivalent areas elsewhere in Japan.

Anthropologists have studied tourism as a transnational vector for the

commodification of culture (Greenwood 1989); as route for and producer

of globalization (Enloe 2014; Stronza 2005); as a mediator of insiders’ and

outsiders’ sense of community and belonging (Smith 1989: 5; Waldren

1996); as a colonialist holdover (Urry 1990); as a source of environmental

degradation and exploitation (Bundy 1996; Vivanco 2006); even as a form

of governance (West and Carrier 2004). As a result, Amanda Stronza (2005:

263) suggests, we know ‘“practically nothing’ about the impacts of tourism

4

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Introduction

on tourists themselves. How are they affected by what they see, do, and

experience during their travels?” Paige West and James Carrier (2004), in

their case studies of ecotourism in Jamaica and Papua New Guinea, find

that the dominant hopes and desires of Western tourists can be gleaned from

the behaviors of host countries. They argue that ecotourism “encourages a

particular way of knowing people and things in pertinent parts of the world”

(2004: 485) and further develop Carrier’s term “virtualism” (Carrier and

Miller 1998) to explain how ecotourism, a quintessentially neoliberal busi-

ness concept, moves and grows in similar ways despite being implemented

in diverse cultural contexts.

Virtualism explains some of the contradictions inherent in ecotourism:

that it tends not to preserve valued ecosystems, but rather creates landscapes

that conform to Western fantasies about Nature4 through a rationalized

“market-oriented nature politics” (West and Carrier 2004: 485; cf. Sivara-

makrishnan 1998); or that the local (“traditional”) values that ecotourism

host communities intend to preserve tend to be replaced by capitalist com-

mercial values (West and Carrier 2004: 486). One of the most common

fantasies disseminating from the so-called Global North is the “rescue of

Nature from anthropogenic destruction” (Keller 2015: 8), a discourse driven

by the rise of industrial capitalism and an underlying belief that Nature is

(or at least should be) kept separate from humanity (West and Carrier 2004:

485). My key questions include: How are these discourses mobilized in a

non-Western, non–Judeo-Christian context? Is there a Japanese equivalent

to the Nature rescue fantasy? If so, how does it manifest in ‘“Tropical Para-

dise Okinawa’” (Figal 2012: 8)?

Clifford Geertz (1997: 20) writes that the study and management of tour-

ism requires that it be conceptualized as an “extended field of relationships,

not readily disentangled from one another, not easily sorted … into clear-cut

and exclusive, opposing categories.” Such oppositional categories include host/

guest, inside/outside, local/global, we/they, and here/there. Studies of eco-

tourism in the early twenty-first century must also address binaries such as

human/non-human, North/South, Western/non-Western, and rich/poor. Ac-

cordingly, this study of the political ecology of ecotourism in Okinawa

demonstrates that “green development” (Adams 1990) is not limited to de-

veloping equatorial nations, and challenges the binarizing discourses of the

Global North and Global South. Ecological appreciation of one form or an-

other is becoming a “positive national characteristic” (Vivanco 2006: 10) in

many countries, but cultural expressions of this cosmopolitan sentiment are

both historically and geographically contingent. This ethnography contrib-

utes to sustainable development literature by providing a case study of eco-

tourism in Okinawa—among the poorest prefectures of one of the world’s

wealthiest nations.

5

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

I began my fieldwork planning to focus on the experiences of mainland

Japanese tourists. However, the first few ecotours I joined helped me realize

that the local (“host”) experience of ecotourism, while it does not involve

travel per se, affects Okinawan perceptions of the environment that move

well beyond the socioeconomic motivations identified by Mr. Miyagi in the

opening ethnographic anecdote. Engagement in tourism-related activities

that encourage Okinawans to view their proximate natural environments as

unique and even healing shapes local participants’ sense of place and sense

of self. In the process of embracing, reappropriating, and responding to the

early twenty-first–century set of political and economic constraints, which I

label collectively as the “tourism imperative,” Okinawans also come to view

their biophysical surroundings like a tourist.

Authenticity and Power

I hate travelling and explorers. Yet here I am proposing to tell the story of [their]

expeditions.

—Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques

The tourist can be defined as “a temporarily leisured person who voluntarily

visits a place away from home for the purpose of experiencing a change”

(Smith 1989: 1). Valene Smith’s classic definition is broad enough to in-

clude virtually all kinds of tourists seeking multiple forms of change (geo-

graphic, climatic, psychological, or spiritual). Amanda Stronza argues that

these leisured people are actually “key protagonists in processes of globaliza-

tion” (2005: 171). Are all tourists today mere pawns in a multibillion-dollar

global industry, or do participants in small-scale forms of alternative tour-

ism develop a sense of ethical responsibility to the places they visit? In 2012,

2 percent of all human carbon emissions came from airplane travel (Mc-

Grath 2016). If ecotourists are concerned with the protection of the natural

environment, then why not curb the carbon footprint and “staycation” at

home?

While “sun, sex, sea, and sand”5 (Crick 1989: 307) form highly visible

components of most island tourism, leisure travel in Japan is often character-

ized as including an explicitly educational element as well (Kato 1994). Go-

toh et al. (2008) find that changes in Japanese demand for marine tourism

can also be linked to larger nationwide sociological trends: growing demands

for leisure time, greater quality of life, and extended leisure activities—as

opposed to short periods of socializing around work—are all changing the

nature of domestic tourism in Okinawa. The authors suggest that ecotour-

6

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Introduction

ism (sometimes referred to as “green tourism”) favors “the environment

and environmental consciousness over sightseeing” through its promise of

a “richer holiday experience through deeper interaction with a community”

(2008: 31).

Until 2015, The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) offered a

simple definition of ecotourism: “responsible travel to natural areas that

conserves the environment and improves the welfare of local people.” The

updated definition reveals the importance now given to the role of the local

interpreter: “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environ-

ment, sustains the well-being of the local people and involves interpretation

and education [of staff and guests]” (TIES 2015). Center for Responsible

Tourism Director Martha Honey’s vision of ecotourism is even more ambi-

tious: beyond promoting low-impact, small-scale travel to fragile, pristine,

and usually protected areas, ecotourism also “helps educate the traveler; pro-

vides funds for conservation; directly benefits the economic development

and political empowerment of local communities and fosters respect for dif-

ferent cultures and for human rights” (Honey 2000: 33). These idealized

definitions warrant unpacking; ecotourism is the fastest growing segment of

the tourism industry, with global expenditure estimates ranging from US$30

billion (Honey 1999: 9) to US$1.2 trillion (West and Carrier 2004: 483; cf.

Butcher 2007; Gössling 2003; Gössling and Hall 2006; Hill and Gale 2009;

Holden 2000). This ethnography builds on Noel B. Salazar’s (2010) study of

power in tourism by moving away from one-sided studies of the impacts of

the global tourism imperative on hosts or guests and instead analyzes the sto-

ries and experiences of local guides, interpreters, and other primary media-

tors of “Tourist Okinawa” (Figal 2012: 15), a carefully curated and mutually

constitutive tropicalized space.

Ecotourism is an idealized travel concept that often emerges in discourses

of sustainable tourism development, but perhaps due to its inherently local-

ized scope, the movement lacks internationally agreed upon standards of im-

plementation and offers few comparative or comprehensive metrics that can

be used to determine its effectiveness. Likewise, the genuine ecotourist can

hardly be identified by his or her rucksack and reusable canteen. Rather, eco-

tourism researcher Robert Fletcher suggests, the ecotourist might be more

easily identified by the strenuousness of leisure activities pursued. According

to Fletcher (2009: 276), unlike “conventional mass tourism where the object

is typically to relax and pamper oneself, the aim of ecotourism is to engage in

strenuous physical exertion and experience uncomfortable—if not expressly

unpleasant—conditions.”

Debates about the problem of authenticity pervade social science litera-

ture on tourism. Erve Chambers (2000) emphasizes the source of agency as

7

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

the key measure of authenticity in host communities. Gerald Figal’s (2012:

89) work on heritage tourism in Okinawa builds on Chambers’s theory of

authenticity by not equating the real/traditional/authentic with “always and

only things of the past one strives to reproduce faithfully under conditions

of modernity” (cf. MacCannell 1999). My objective in studying ecotourism

development in Okinawa is neither to “condemn hoaxes nor to award diplo-

mas of genuineness, but rather to understand a moral and social phenome-

non which is especially peculiar” (Lévi-Strauss 1955: 18).

West and Carrier (2004: 485) demystify another contradiction inherent

in ecotourism—the apparent ethical contradiction between conservation and

travel—by demonstrating that the authenticity of a traveler’s experience is

judged through the framework of “Nature and the frontier” rather than the

messages of conservation biologists or anthropologists. Primordial Nature,

with its host of exoticized plants, animals, and (in some cases) people, can

only be reached by “being here” (Geertz 1988: 130). We can begin to un-

derstand ecotourism’s peculiar mix of leisure, fantasy, and activism by first

studying its proponents and practitioners—those who are already “here,” nav-

igating with great passion the future of tourism development on Okinawa.

Ecotourism is meant to change the nature of encounters between hosts

and guests in destination communities and ecosystems around the world

(Stronza 2005: 171). This ethnography focuses on the experiences of “ed-

ucationally oriented” Okinawan and mainland Japanese travelers (Smith

1989: 5). The consumer profile of the ecotourist is different from that of the

middle-class Japanese tourist who, since the 1960s, has desired Tropical Para-

dise Okinawa. However, Akinori Kato finds that the difference is more likely

a matter of degree than kind. The educational component of ecotourism is

important not only to Japanese vacationers who seek to camouflage or at

least justify the purely recreational element of their trips with an educational

(or religious) component (Kato 1994: 57–59); improving environmental ed-

ucation about Okinawa is also a top priority for many of the nature guides

I met during fieldwork. By examining the touristic reciprocity that shapes

host-guest encounters at Okinawa’s natural sites, I hope to complicate our

understanding of the motives and desires of those who preserve, maintain,

package, and present these places for outsiders—and for themselves.

By studying ecotourism in Okinawa, I complicate the narrow view that

most educationally oriented travelers who participate in ecotourism, whether

as paying customers, guides, or planners, are also members of a very narrow

demographic: “namely, white, professional-middle-class members of post-

industrial Western societies” (Fletcher 2009: 271). According to Robert

Fletcher, these professionals tend to be people who practice (or were raised

by practitioners of ) “relatively well-paid white-collar professions” (271)

8

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Introduction

such as teaching, journalism, business, and law. While Japanese people have

been problematically characterized as “Honorary Whites” or even “Honor-

ary Europeans” (Adachi 2010; cf. Beasley 1987; Kawasaki 2001), Fletcher’s

generalizations about the ethnic, cultural, and geographic backgrounds of

most ecotourists lose traction when considered in the Okinawan context. In

Okinawa, racialized discourses of difference constructed vis-à-vis the idea of

the dominant mainland Japanese ethnic group unsettle hemispheric divides

(cf. Keller 2015; Lowe 2006; Tsing 2005) that inform much of the existing

scholarship on ecotourism.

Nature has always been a resource in Okinawa, but Yambaru’s recent eco-

nomic transformation from supplier of lumber for postwar reconstruction

in the south to recipient of vacationers (from southern Okinawa Island,

mainland Japan, the United States, and beyond) has dramatically altered the

region’s economic makeup. This transformation has also spurred new dis-

courses of ecological uniqueness that influence local residents’ regard for the

everyday rivers, forests, and oceans that constitute the northern landscape.

By bringing this landscape to life in a dynamic new way, ecotour guides re-

conceptualize their own and their customers’ practical, physical, emotional,

and spiritual relationships with biophysical nature.

This book is a parallel endeavor. Rather than presenting the biophysical

world in snippets of colorful ethnographic details to evoke the scene of pri-

mary human-human interactions and events, I place forests, oceans, rivers,

and their array of nonhuman inhabitants centrally in my narrative. I em-

ploy “landscape ethnography,” which Laura Ogden defines as “an approach

to writing culture that is attentive to the ways in which our relations with

non-humans produce what it means to be human” (2011: 28). My objective

is to provide new interpretations of a few key interspecies relationships cul-

tivated through Okinawan ecotourism today. These relationships are clearly

influenced by, but not reducible to, the profound social, political, and en-

vironmental consequences of colonization and war, and the attendant dis-

courses of death, loss, violence, and invasion so superbly articulated by other

anthropologists of Okinawa (e.g., Angst 2003, 2008; Nelson 2008).

I attempt to expand scholarship on Okinawa by including nonhuman

animal histories, without which critical Okinawan perspectives on the en-

vironment cannot be usefully incorporated into the literature on tourism-

dependent islands, sustainability, and ecotourism. In addition to rendering

legible the lasting ecological consequences of nineteenth-century Japanese

colonialism, of the devastating 1945 Battle of Okinawa, and of the postwar

U.S. occupation of Okinawa (1945–72), I conduct a hopeful analysis of

Okinawan responses to the tourism imperative through new forms of en-

gagement with nature.

9

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

Fieldsites and Methods

I conducted the first half of my fieldwork (August 2009–April 2010) from

Ginowan, a central Okinawan city about a twenty-minute drive north of

the capital city of Naha where close to 90 percent of Okinawa’s popula-

tion resides (see Figure 0.1). I chose to move to Ginowan because it put

me just a short drive away from the University of the Ryukyus, where I

was affiliated and audited a variety of courses on ecotourism, sustainable

tourism development, and environmental education over the course of my

fieldwork. Ginowan, located next to the town of Chatan (where I completed

my open-water scuba diving certification in 2009), is one of the primary sites

for coastal coral transplanting activities described in Chapter 4. The bulk of

my training dives were conducted with members of Reef Check Okinawa, a

nonprofit organization (NPO) in the southern city of Itoman.

For the second half of my fieldwork (December 2010–May 2011), I

moved north to Nago, the largest city in the Yambaru Area. The name “Yam-

baru” (ჰ) combines the Chinese characters for “mountain” and “field,”

refers to the area’s geographic characteristics. The Yambaru Area includes

Nago City and the three villages of Kunigami, Higashi, and Ōgimi (see Fig-

ure 0.1). From Nago, I was able to frequently visit the Wellness Center in

the town of Motobu and the Churaumi Aquarium, as well as the Kunigami

Forest Therapy Centers, all of which became central sites for my research.

Yambaru’s forests are comprised of low hills covered by evergreen oak (Itajii)

and subtropical plants, including wild orchids, azaleas, ferns, and mistle-

toe (McCormack 1999: 267). Protected species include the Ryukyu robin,

Scops owl, Pryor’s woodpecker, Okinawa rail, and rare amphibians, reptiles,

and insects.

Throughout my fieldwork I was a visiting scholar in the University of the

Ryukyus’ Department of Tourism Sciences (DTS) and at the International

Institute for Okinawan Studies (IIOS). I worked primarily with sustainable

tourism planning and environmental education specialist Professor Junko

Ōshima (DTS) and Katsunori Yamazato, Professor of American literature

and Director of IIOS. By guest lecturing in Professor Ōshima’s Ecotourism

courses, I gained a sense of the kinds of questions and problems being ad-

dressed by tourism researchers. During the second half of my fieldwork, I

was also a visiting scholar in Tourism Sciences at Meio University in Nago.

Under the auspices of Professors Yūji Arakaki and Sumiko Ōgawa, I had

the privilege of presenting my findings at the Okinawa Ecotourism Promo-

tional Association’s annual conference in 2011. These kinds of intellectual

exchange opportunities provided invaluable networking opportunities and

helped me to refocus my scope of inquiry over the course of my fieldwork.

10

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Introduction

With the help of my advisers, I gained introduction to a variety of gov-

ernment agencies and NPOs that generously facilitated my participation in

the majority of activities described in this book. At the Okinawa Interna-

tional Center in Urasoe, I attended weekly lectures and training sessions on

ecotourism and sustainable tourism development sponsored by the Japan

International Cooperation Agency (JICA), a Japanese government orga-

nization frequently compared to USAID. JICA sponsors tourism industry

professionals from the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries and

Oceania to engage in sustainable tourism training workshops and site visits

ranging from six weeks to six months in length. By following these groups,

actively participating in their brainstorming sessions, and serving as a discus-

sant during presentations of their project summaries, I became familiar with

the discourses of sustainability and development that pervade the tourism

sector of islands currently receiving Overseas Development Aid (ODA) from

Japan.

By following and riding on the official JICA bus, I learned which na-

ture-based tourism sites are considered most important by the Okinawans

who organized our visits. Sites included the Churaumi Aquarium, the Za-

mami Whale-Watching Association, the Ufugi Nature Museum, and Kuniga-

mi’s Forest School, all of which are discussed in the chapters that follow.

JICA and the Okinawa International Center worked in conjunction with

NPOs such as the Okinawa Environment Club (OEC) and the Kunigami

and Higashi Tourism Associations to organize experiential training fieldtrips

that fostered discussion and debate between international participants on

the relative merits and disadvantages of how ecotourism is conducted in

Okinawa. With permission from key administrators of these training tours,

I participated in ecotourism activities and observed how sustainable tourism

in Okinawa is produced for tourist consumers, local residents, and tour staff.

The interviews included in this book were conducted as formal and infor-

mal semi-structured conversations with the government officials, academics,

nonprofit directors and affiliates, guides, tourists, and museum employees

who were kind enough to answer my questions before, during, and after

tours.

I also attended Okinawa Prefecture–sponsored conferences on topics

ranging from biodiversity, conservation, and slow living to long-stay tourism

and community building. Much of the data I include was gleaned from com-

prehensive presentations and handouts provided by lecturers at these talks.

A presenter at one of these conferences outlined some of the common so-

cioeconomic characteristics of ecotourists: “They are mostly women in their

twenties, of the highest educational background.” He went on to list a few

sub-categories profiling the typical ecotourist:

11

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

• Socially Aware (politically active)

• Visible Achiever (interested in material success)

• Young Optimist (age 18–24)

I quickly determined that I was the Young Optimist (or at least, that

I had been when I began graduate school). Having my demographic mir-

rored back to me so succinctly made me squirm, and reminded me to avoid

broad generalizations about my informants wherever possible. Castaneda

and Wallace (NAPA Tourism Workshop, 19 November 2008) acknowledge

some common challenges associated with studying tourists, a category most

anthropologists have probably occupied at some point during their time in

the field: “One runs the risk of studying her/himself being a tourist partic-

ipant. … Studying tourism, especially tourists, can lead to uncomfortable

introspection without a path through the maze of self-interpretation.” The

theme of “uncomfortable introspection” that runs throughout this book is

an unintended consequence of my methodological approach, which can

be summarized as participating in ecotours and other nature-based tourist

activities; observing the ways that guides and tourists interacted with each

other and with the nonhuman life forms they sought; and conducting in-

formal, semi-structured interviews with the ecotourism advocates and local

participants whose lives and livelihoods are affected most directly by the

expansion of alternative tourism activities in the north.

This book represents my attempt to create a path through the “maze of

self-interpretation” that concerned me as an ethnographer, but also held clear

significance for Nago Museum and Ufugi Nature Museum affiliates, Forest

and Dolphin Therapy participants, and perhaps most of all for the Japanese

and Okinawan nature interpreters who, like me, linked their identities di-

rectly to their interpretive work. My research contributes to anthropological

perspectives on tourism, inter- and intra-subjectivity, and the environment

by probing the ways in which discourses of vulnerability, loss, and disaster

shape the politics of island tourism development and produce new forms

of environmental affect in guides and participants. I bridge the existing an-

thropological literature on the small island “vulnerability paradigm” (Moore

2010), “hosts and guests” (Smith 1989), and interspecies (or “post-human”)

relationships by focusing on the organized natural and touristic encounters

that bring these discourses into the same frame.

I begin my inquiry by asking: How do people become ecological stake-

holders through participation in forms of travel idealized as sustainable?

What kinds of performative acts serve to destabilize and reconstitute the

economic, political, and social categories oversimplified by the labels Tour-

ist, Expert, and Local? I consider broadly what is at stake in our ability to

12

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Introduction

cultivate and support affective relationships with nonhuman forms of life—a

need that increasingly manifests in the form of nature-based tourism.

The pages that follow will take you on a series of ethnographically ren-

dered ecotours and other touristic animal encounters that re-create the com-

plexity of experience I saw, touched, and felt when following guides and

their tourists into the woods, under the sea, and into the town halls, con-

ference rooms, and museums where they discussed what these forays into

nature mean to them.

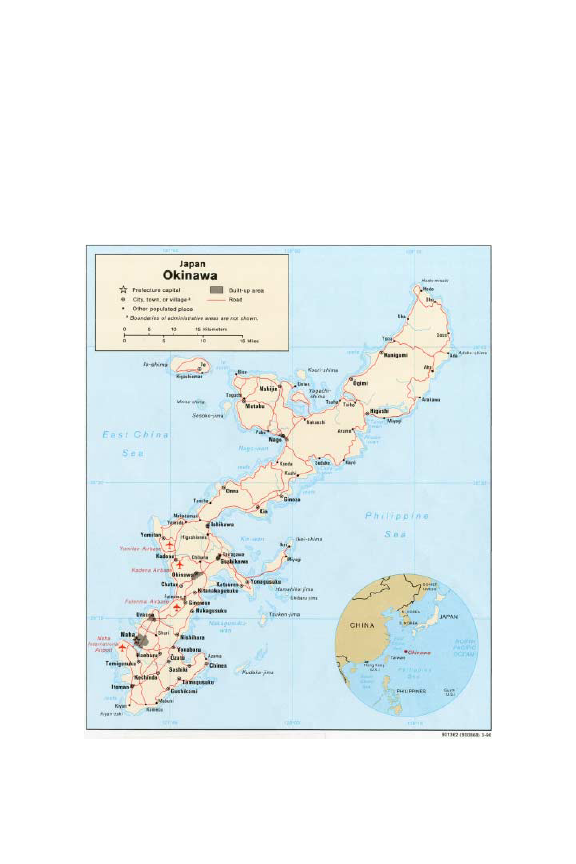

FIGURE 0.1 • Map of Okinawa Island, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan6

13

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

Notes

1. All informants’ given names and nicknames have been changed. All Japanese and Oki-

nawan names are presented throughout the text as follows: [First Name] [Family Name]

in accordance with standard English language practice.

2. Noel Salazar (2010: 139) grapples with the politics of naming social actors in host com-

munities, considering “passive” terms favored by other scholars: “visitee,” “travelee,” and

“touree.” Salazar favors the more agentive “tourate” for his multi-sited study of foreign

tourist guides in developing countries. Because this ethnography explores the fluidity of

identities within domestic tourism and across multiple social frames (cultural, occupa-

tional, political), I do not favor any one descriptor for Okinawans involved in the tourism

industry. Rather, I adopt the language used by my informants to describe their work.

3. While the focus of this ethnography is Japanese domestic tourism, it is worth noting that,

according to the World Tourism Organization, in 2005 roughly a quarter of international

“tropical island tourists” came from Australia, Japan, and Indonesia (Picard 2013: 17). For

a discussion of translation, knowledge, and nature-based Japanese tourism in Canada, see

Satsuka (2015).

4. Raymond Williams (1983) observes that the word “Nature” is “perhaps the most com-

plex word in the [English] language” (219). Following Anna Tsing (2005) and Eva Keller

(2015), I capitalize “Nature” when emphasizing a particular related discourse or defini-

tion such as “singular global system uniting all life” (Tsing 2005: 91). I do not capitalize

“nature” when using the term to convey its many other meanings. For a groundbreaking

history of a similarly problematic term, “Wilderness,” see Cronon (1995).

5. These are Crick’s often cited “4-S’s of tourism” (1989).

6. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

14

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Chapter 1

OKINAWA’S TOURISM IMPERATIVE

Introduction

A basic familiarity with Okinawa’s history and political economy is essential

to understanding the prefecture’s tourism industry in the early twenty-first

century. In this chapter, I provide a brief overview of the historical circum-

stances that have produced tourism dependency in Okinawa. I trace the

development of Okinawa’s tourism imperative to explain the contemporary

practice and presentation of ecotourism in northern Okinawa.

Island Geographies, Populations, and the Politics of Naming

Okinawa is Japan’s southernmost prefecture. The formal prefecture consists

of roughly 160 islands encompassed by a longer chain of islands collectively

known as the Ryūkyū Archipelago (ਹ౯⊝ặ), about forty of which are

inhabited by people. The Ryūkyū Archipelago stretches over a thousand

kilometers, extending southwest from Kyushu (the southernmost island of

Japan’s four main islands) to Taiwan. The archipelago is usually divided from

northeast to southwest and includes four geographic subgroupings: Oki-

nawa, Miyako, Yaeyama, and Senkaku Islands. The prefecture’s capital city,

Naha, is centrally located on Okinawa Island (Okinawa hontō),1 by far the

largest of the Ryūkyū Islands and the primary site of my fieldwork.

Okinawa’s political history can be examined through the lens of language,

which is also deeply linked to the questions of cultural authenticity, exoti-

cized otherness, and regional pride that continue to shape touristic represen-

tations of the island today. The former semi-autonomous Ryūkyū Kingdom

operated centrally in an expansive trading system that began during the sev-

enth century, connecting the archipelago with China from the fourteenth

15

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

century, and Japan from the fifteenth century, until the late nineteenth cen-

tury, throughout which the Ryūkyūan government paid tribute to both pow-

ers (Zabilka 1959: 15–17).

The name, according to the Chinese, is of Chinese origin, for the word “Lew-

k’ew” [Ryūkyū] means “hanging beads” and refers to the fact that this island

chain is like a string of tassels on the skirt of China. But though the Japanese

have allowed their own pronunciation of this name to stand, they favor the name

“Okinawa” or the “long sea rope” which stretches as a cable between Japan and

Formosa [Taiwan], and thus makes these islands and Formosa an integral part of

Japan proper. (Gast 1945: 12)

The expansionist Japanese government formally annexed Okinawa in 1872,

establishing Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. Americans referred to the same

group of islands as “Ryukyu” from their first involvement in the mid nine-

teenth century until the end of the post–World War II U.S. military occu-

pation (1945–72).

The Okinawan-language term for Okinawa is Uchinaa. There are many

ways to refer to the Okinawan language, each carrying a different political

valence. In Japanese, the now dominant language of Okinawa Prefecture

(and the language in which I conducted the bulk of my fieldwork), one is

most likely to hear the terms Okinawa-go (Okinawan) or hōgen (dialect of

Japanese). In Okinawan, however, Uchinaaguchi (literally “mouth of Uchi-

naa”) denotes the umbrella language that was spoken throughout the island,

with some regional variation, until Japan’s forced assimilation policies sys-

tematically eradicated it from classrooms and other public spheres during

the early twentieth century.

Linguists such as Rumiko Shinzato have recently established that Uchinaa-

guchi2 is not, in fact, a dialect of Japanese. While the two languages are genea-

logically related, Okinawan is less than 70 percent cognate with standardized

Japanese and the two are mutually unintelligible (2003: 284). Shinzato

(2003: 284-291) identifies the following six distinct periods over the course

of less than one century, a period during which the Okinawan language was

purged from daily life but eventually emerged as a key marker of cultural

pride and difference:

1) Before the creation of Okinawa Prefecture (1879): Okinawan exists as

an independent language of the Ryūkyū Kingdom

2) From 1879 until the start of First Sino-Japanese War (1895): Oki-

nawan is gradually marginalized through the “top-down” imposition

of Japanese-language–only schools and conversation training centers

for monolingual adults

16

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Okinawa’s Tourism Imperative

3) From 1895 until Japan invades China again, effectively beginning the

Second World War (1937): Japanese becomes the language of educa-

tion through a period of more grassroots standardization, while Oki-

nawan is still spoken at home

4) 1937–45, a period which spans the Second Sino-Japanese War and

World War II: Okinawan is denigrated as a dialect, the use of which

is punishable in increasingly militarized schools during a period of

extreme Japanese nationalism

5) 1945–72, the period of the formal U.S. Military occupation of Oki-

nawa: Okinawan declines rapidly under postwar U.S. policies designed

to propagate English and squelch the rise of pro-Japanese sentiment

6) 1972–present (Reversion to Japan in 1972): Okinawan resurges as a

point of prefectural pride following Okinawa’s political reversion to

Japan

Until 1879, Okinawan monolingualism was standard throughout the

Ryūkyū Kingdom; today, Okinawans under age sixty speak and understand

Okinawan-accented standard Japanese. The Japanese (and later, the U.S.)

government’s political conquest of Okinawa was achieved in part through

“linguistic conquest” (286), and I very briefly summarize these periods to

historicize one of the most intensive processes through which Uchinaan-

chu (people of Okinawa) have come to regard themselves as “Okinawan”

and, to a lesser degree, “Japanese.”3 Okinawan-language greetings such as

Haisai! (Hello) and Menso~re! (Welcome) are much more likely to be di-

rected at sunblocked tourists than spoken between Okinawans in everyday

conversation.

Okinawans also have many names for mainland Japan4: Yamato (which

indexes the ancient Japanese capital of Nara and the dominant Japanese

ethnic group, known in Okinawan as Yamatonchu), Naichi (a relic of the

Japanese colonial period that indexes the main islands as the “internal” or

“home” territories), and occasionally even just Nihon (today’s most com-

monly used Japanese language name for Japan). My informants frequently

used these descriptors selectively to imply varying degrees of historical, cul-

tural, and linguistic separateness from Japan.

My informants regarded the reclamation and continued use of Okinawan,

and of dialects of Okinawan unique to the northern area where I worked, as

central to the joint enterprises of revitalizing local pride and strengthening

small-scale tourist economies. Whether for the edification and entertainment

of mainland Japanese tourists or for the benefit of Okinawans, the preserva-

tion of the Okinawan language functions as a strategic claim to authenticity

by emphasizing the islands’ cultural and historical difference from Japan.

17

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

Okinawa’s “3-k” Economy

Your assignment to the Ryukyu (Ree-YOU-que) Islands—of which Okinawa is

the largest—will place you in pleasant surroundings, face to face with people

quite different from those back home. If you have not been in the Far East before,

the sights you see and the people you meet will seem strange at first. But you

will feel at home once you get acquainted with the Ryukyuan people and make

friends with them.

It would be a mistake, in an essentially rural and village country such as the

Ryukyus, to expect the dazzling attractions found in Tokyo, London, or Paris.

But the Ryukyus have much to offer, not the least of which is the natural beauty

of a varied landscape. And wherever you go, you will find the Ryukyuans friendly

and hospitable. These winning traits of the people have earned for Okinawa such

titles as “Land of Courtesy” and “Isle of Smiles.” Even the most glum visitor will

enjoy the good-natured smiles and laughter of the Okinawans …

Because of the strategic importance of the Ryukyus, it is essential that you

understand the islands’ background and people and the political circumstances

under which the United States retains control there. This guide will help you ap-

preciate the Ryukyuan point of view by telling you a little about the Ryukyuans,

their way of life, their problems, and their aspirations. The more you know about

the Ryukyuans, the more you will appreciate them and enjoy your tour of duty

among them. Take advantage of an unusual opportunity to know at close range

these delightful Asian people. (A Pocket Guide to Okinawa,5 U.S. Department

of Defense 1961)

The above excerpt, taken from an early 1960s U.S. Department of Defense

“Pocket Guide to Okinawa” written for military personnel, illustrates key

aspects of the deep connections between Okinawa’s tourism industry and the

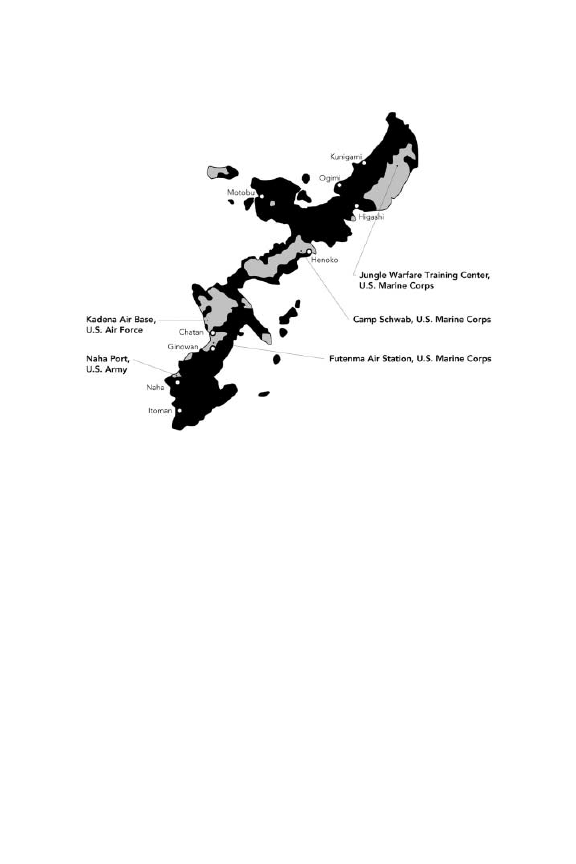

presence of U.S. military bases on the island (see Figure 1.1). Glenn Hook

and Richard Siddle (2003: 6) reject the image of Okinawans as “non-threat-

ening, laid-back and relaxed ‘exotic’ islander[s], ever ready to burst into song

and dance, happily supportive of the status quo and the ‘warm’ relationship

with the mainland,” a stereotype reified through similar kinds of pamphlets

now directed at mainland Japanese tourists instead of U.S. soldiers.

The formal U.S. occupation of mainland Japan ended in 1952 with the

signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which recognized Japan’s ‘“resid-

ual sovereignty”’ (Tanji 2006: 61), but allowed U.S. forces ‘“to be stationed

all the time in and about Japan.” Of Okinawa, President Eisenhower pro-

claimed in his 1952 State of the Union message: ‘“The Ryukyu Islands will

be held for an indefinite period,”’ thus reinscribing the politicized differences

between Uchinaa and Yamato described previously. Another twenty years

passed before Japan and the United States negotiated the return of Okinawa

to Tokyo’s jurisdiction.

18

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Okinawa’s Tourism Imperative

FIGURE 1.1 • Map of U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa6

Note: Not all U.S. military facilities are labeled.

On 15 May 1972, seven new laws were implemented to administer the

islands, including a law to address “Special Measures for Promotion and De-

velopment of the Islands of Okinawa” (Asato 2003: 234). Tourism fell under

the rubric of the Promotion and Development Plan, meant to help Okinawa

achieve parity with mainland Japan. In 1973 the mayor of Nago City fore-

shadowed the issues I explore here when he criticized Tokyo’s industry-driven

approach to development: “Human beings have become enslaved to produc-

tionism, which results in the destruction of the basis of our existence. Rather,

we citizens of Nago should take as our goal the creation of the most favorable

life environment” (234). The mayor’s criticism of Okinawans’ postwar de-

velopment imperatives as “productionism” can be read as a response to the

Okinawa Tourism Association’s (OTA) attempts to produce what members

called “tourism consciousness” (kankō ishiki) in the prefecture beginning

in 1954 (Figal 2012: 37). Gerald Figal’s (2012: 39) description of the OTA

mission can be understood as a kind of virtualism wherein “Okinawans

needed to view physically and conceptualize discursively their island in terms

consonant with the expectations of outsider visitors.”7 The Tropical Paradise/

19

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Footprints in Paradise

Tourist Okinawa mentality expressed by so many Okinawans today had to

be learned as an alternative narrative to the all too real “poverty-stricken,

foreign-occupied, war-ravaged homeland” (39) Okinawans were forced to

contend with in the postwar period.

Once the 1972 Reversion eliminated strict U.S. policies that required

passports and visas for travel between Okinawa and Japan, a newly domestic

tourism promoting the “subtropical climate, the beautiful ocean, and the

exotic city scene” became a major industry (Shinzato 2003: 290). Gavan

McCormack (1999: 275) identifies the 1975 Marine Expo as the beginning

of mainland Japanese interest in Okinawa’s touristic potential, which led to a

decades-long “wave of steel” and concrete in the form of resort development.

Tourist visits jumped from 800,000 annually in 1974 to 1.8 million in 1975,

3 million in 1992, and nearly 6 million in 2009.

By the mid 1980s and 1990s, streamlined travel was furthering the spread

of a so-called “Okinawa boom” across Japan: Okinawa-themed music, the-

ater, and cinema gained popularity on the Japanese mainland, driving re-

newed interest in the revival and preservation of the Okinawan language and

mainstreaming a renewed sense of Okinawan pride. Domestic tourism con-

tinued to rise as things Okinawan grew in popularity and commercial prof-

itability, and the previously stigmatized idea of “Okinawa Time” (a slower,

more relaxed pace of life) found new currency among stressed mainland vis-

itors (Nelson 2008: 236).

Now, in the midst of what Hook and Siddle (2003: 6) identify as the

“third wave” of the post-Reversion tourism frequently characterized by bat-

tlefield tours and organized shopping trips for cheap goods, Okinawans in-

volved in ecotourism are actively resisting the typical travel packages that

place visitors in mainland-funded luxury hotels staffed by non-Okinawans.

Tourism forms one leg of Okinawa’s basic economic structure, often re-

ferred to as the “3-k” economy, meaning that kichi, kankō, kōkyō jigyō—

“bases,” “tourism,” and “public works,” respectively—constitute the main

sectors of employment in Okinawa. These three industries frequently come

into conflict over questions of aesthetics and environmental health. Hook

and Siddle describe how human intervention in the form of widespread U.S.

military base construction subjected postwar Okinawa to “the good, the bad

and the ugly” (2003: 3). Bases bring at least four major kinds of suffering

to Okinawans living nearby: clamor, calamity, contamination, and crime

(Gillem 2007: 17). Linda Angst (2003) and Cynthia Enloe (2014) show that

Okinawan girls and women are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence

perpetrated by U.S. soldiers, who between 1972 and 2001 constituted four

percent of Okinawa’s population and were responsible for 1.7 percent of

crime (Cullen 2001, quoted in Gillem 2007: 308). Chronic aircraft-related

noise pollution,8 oil spills, accidental jet and auto crashes, and robberies and

20

This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale.

Okinawa’s Tourism Imperative

murders committed by U.S. soldiers are among the many complaints voiced

by Okinawans (Gillem 2007: 48).

Among Japan’s forty-seven prefectures, Okinawa comprises just 1 percent

of Japan’s landmass but holds 75 percent of U.S. bases in Japan (Hein and

Selden 2003: 5). The United States, which has more overseas military bases

than any other country (Enloe 2014: 126), currently maintains fourteen

military bases on or near Okinawa Island. These bases occupy close to 20 per-

cent of the island’s landmass and comprise roughly one-third of Yambaru in

the form of jungle training areas (McCormack 1999: 267). In 2016, there

were roughly 27,000 active-duty service members stationed on Okinawa, a

number that doubles when Department of Defense civilians and dependents

are included (Narang 2016). The social problems caused by U.S. military

bases remain the top priority in contemporary Okinawan politics, and griev-

ances frequently invoke base-related environmental destruction and the loss

of natural habitat for Okinawa’s animals.

In 1996 the Okinawa Development Agency’s expansive public works

projects constituted more than half of all construction business in Okinawa

(Hein and Selden 2003: 4). The “pristine” forests of the north become in-

creasingly valuable when juxtaposed with the “bulldozed and concreted”

rivers, beaches, and land, the damage from which feeds into the coastline

in the form of red soil runoff, killing coral and other sea life in less obvious

ways (5).

Redefining “The Environment” in the Postwar Period

To approach defining a “favorable life environment,” we must first consider

how the meaning of the term “environment” has taken shape throughout

Okinawa’s history. Okinawa-based scholar Eiko Asato succinctly outlines the

development trajectory I explore in this work: the destruction of the natural

and social environment, Asato (2003: 236) writes, “began with the devastation

of war, was followed by the degradation of the environment through military

base construction [and was] followed by industrial and tourism development.”

Shin Yamashiro’s (2005: 51–55) summary of the “critical phases” of Oki-

nawa’s environmental history complements Shinzato’s earlier analysis of Oki-

nawa’s linguistic history:

1) Preparation for War (1940s to October 1944)

2) Direct Impact of the War (1944–45)

3) Aftermath of the War (1945–72)

4) Preservation and Conservation of Natural Resources (1972 to the

1990s and onwards)

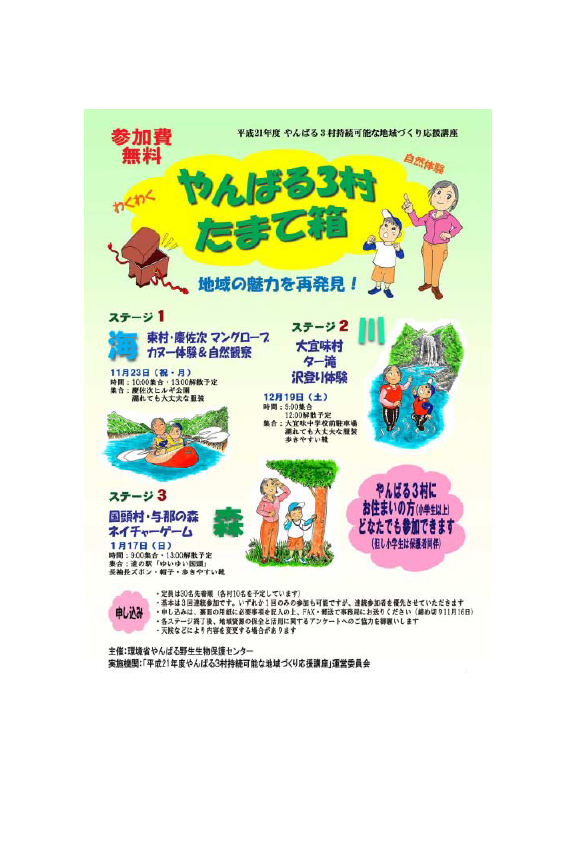

21