International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Article

Assessing the Impact of a Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing)

Intervention on Physician/Healthcare Professional Burnout:

A Randomized, Controlled Trial

John Kavanaugh 1,*, Mark E. Hardison 2, Heidi Honegger Rogers 3, Crystal White 2 and Jessica Gross 4

1 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of New Mexico Hospital,

University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM 87106, USA

2 Occupational Therapy Graduate Program, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA

3 College of Nursing, University of New Mexico College of Nursing, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA

4 Clinical and Translational Science Center, University of New Mexico Health Science Center,

Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA

* Correspondence: jpkavanaugh@salud.unm.edu

Citation: Kavanaugh, J.; Hardison,

M.E.; Rogers, H.H.; White, C.; Gross,

J. Assessing the Impact of a

Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing)

Intervention on Physician/Healthcare

Professional Burnout: A Randomized,

Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res.

Public Health 2022, 19, 14505. https://

doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114505

Academic Editors: Amber L.

Vermeesch, Andrew Lafrenz

and Chloé Littzen

Received: 20 September 2022

Accepted: 1 November 2022

Published: 4 November 2022

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Abstract: Professional healthcare worker burnout is a crisis in the United States healthcare system.

This crisis can be viewed at any level, from the national to local communities, but ultimately, must be

understood at the level of the individual who is caring for patients. Thus, interventions to reduce

burnout symptoms must prioritize the mental health of these individuals by alleviating some of the

symptoms of depression, grief, and anxiety that accompany burnout. The practice of Shinrin-Yoku

(Forest Bathing) is a specific evidence-based practice which research has shown can improve an

individual’s mental health and, when performed in a group, can support a sense of social connection.

We investigated the impact of a three-hour, guided Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) nature-based

intervention on burnout symptoms among physicians and other healthcare workers by using a

randomized, controlled trial. The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) and Mini-Z assessments were

used to collect baseline burnout scores and participants were randomized into the intervention group,

which completed the assessment again after the Shinrin-Yoku walk, or into a control group, which

completed the assessments again after a day off from any clinical duties. A total of 34 participants

were enrolled in the intervention group and a total of 22 participants were enrolled in the control

group. Ultimately, no statistically significant differences were detected between the pre-test and

post-test scores for the intervention group or between the post-test scores of the intervention group

compared to the control group. However, the subjective responses collected from participants after

participating in the Shinrin-Yoku walk overwhelmingly reported decreased feelings of stress and

increased mental wellbeing. This raises important questions about the difference between symptoms

of burnout and other aspects of mental health, as well as the limitations of a one-time nature-based

intervention on levels of chronic burnout symptoms. Thus, further research on the effects of engaging

healthcare providers in an ongoing practice of Shinrin-Yoku is warranted.

Keywords: forest bathing; Shinrin-Yoku; forest therapy; professional burnout; healthcare providers

Copyright: © 2022 by the authors.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

1. Introduction

Shinrin-Yoku (forest bathing) is the practice of “visiting a forest or engaging in various

therapeutic activities in a forest environment to improve one’s health and wellbeing” [1].

More specifically, it is an intentional practice in which the practitioner immerses themselves

in nature while mindfully giving attention to the sensory information they receive from

that natural environment. Forest Bathing as a term was coined by the Japanese government

in 1982, and since this time, researchers around the world have been assessing the impact

of Forest Bathing on a wide variety of physiological and psychological variables. These in-

clude potential benefits for immune system function (increase in natural killer cells/cancer

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114505

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

2 of 11

prevention), the cardiovascular system (hypertension/coronary artery disease), the respira-

tory system (allergies and respiratory disease), depression and anxiety (mood disorders

and stress), mental relaxation (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder) and human feelings

of “awe” (increase in gratitude and selflessness) [2]. In a study conducted in Japan in

2019 to evaluate the effects of Forest Bathing on working age adults with high stress and

depressive tendencies, a two-hour Forest Bathing activity was shown to decrease blood

pressure and alleviate negative psychological parameters, especially in participants with

depressive tendencies [3]. Some benefits from a single Forest Bathing experience, such as

the improved functioning of natural killer (NK) cells, have been found to persist for up to

30 days [4]. Based on the demonstrated health benefits of Forest Bathing, researchers have

stated the need for further research in the “areas of healthcare professional stress reduction

and life balance” [2].

Professional burnout is of increasing concern within the healthcare system, both in

terms of the mental health of the providers as well as the impact it has on the quality and

safety of patient care. Burnout is an unfortunately prevalent syndrome among physicians

and other healthcare workers and the symptoms can consist of emotional exhaustion,

depersonalization, and feelings of low personal accomplishment [5]. It is estimated that

33–50% of all physicians experience at least one of these dimensions of burnout and

that these symptoms are also prevalent among other healthcare workers [5,6]. This is

especially relevant given that work-related stress and symptoms of burnout have been

exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. Multiple studies and organizations have

mobilized to understand and address the issue of physician burnout. In a 2019 study on

the effectiveness of resident-led initiatives, residents reported that they perceived the most

effective interventions to be fitness-based activities (gym, walk, outdoor activity, Tai Chi)

and art therapy. In a meta-analysis of different interventions, a meditation workshop was

also noted to decrease resident burnout rates [8,9]. These findings are highly suggestive

that Forest Bathing, which involves outdoor activity with a mindful meditative component,

could be beneficial in addressing physician burnout.

In a review of the literature, only one study was identified which analyzed the effects

of a Forest Therapy intervention on burnout. A 2015 study held in Korea studied the

effects of a 3-day Forest Therapy program on 19 female “workers in the healthcare and

counseling service industry”, who reported a low-frequency use of a forest environment

compared to a control group of 20 female participants from the same industry who reported

a high-frequency use of a forest environment [10]. The control group was initially found

to have lower indicators of stress than the experimental group, which was thought to

be secondary to them already using the forest environment more frequently prior to the

study. The findings of the study were variable; however, it did find an improvement in

perceived stress levels and on professional efficacy in participants of the Forest Therapy

camp as determined by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). This study and the lack of

similar studies demonstrates the need for further research of this therapy as a potential

intervention to address the serious and widespread prevalence of physician burnout.

In the United States, the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy (ANFT) is a leading

organization providing Forest Therapy interventions. It offers courses for participants to

become certified Forest Therapy guides, who then lead others through a series of invitations

to encourage a therapeutic, mindful engagement with the natural environment [11]. These

guided walks introduce new practitioners to Forest Therapy who are unfamiliar with this

therapeutic exercise. This has similarities to the Forest Therapy centers in countries such as

Japan, which provide guides, on-site physicians, and designated Forest Bathing trails with

signs listing specific invitations into the practice along the route.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of a guided Forest Bathing ses-

sion on symptoms of burnout and collect qualitative feedback on this intervention. It was

hypothesized that a Forest Bathing session would result in a statistically significant improve-

ment from baseline burnout symptoms when compared to a control group experiencing a

typical day off of clinical work.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

3 of 11

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This project was a two-arm, randomized, controlled trial with a waitlist control group.

Outcomes were collected at two timepoints: before and after the allocated intervention.

Participants were allocated into intervention groups by using the randomization module

on REDCap that draws from a pre-randomized table, assigning sequential participant IDs

to different groups. A blinded researcher allocated all new participants at the time they

entered the study by clicking the “randomize” button on the REDCap electronic form.

The randomization table this process drew on was generated before the study by using

blocks of 6 for all possible permutations for 2 groups, and then rolling dice to generate the

sequence of blocks.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki

and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of New Mexico Health

Sciences Center (21-419, approved on 1 February 2022. Informed consent was obtained

from all subjects involved in the study before beginning. All recruitment, interventions,

and data collection occurred in a 3-month period in Spring 2022. Participants in the

experimental group were allowed to sign up for a Forest Bathing walk immediately

after filling out the pre-test materials. Participants in the waitlist control group had to

wait a minimum of 5 days and fill out the post-test survey on a day off from clinical

duties before signing up for a Forest Bathing walk. This did not move them into the

experimental group, but rather was carried out solely to allow all interested individuals

to participate in the intervention. This option was made available given that this inter-

vention was being offered to assist with the wellness of healthcare providers coping with

the challenges of a worldwide pandemic.

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

Recruitment used convenience sampling of health sciences faculty and medical resi-

dents at a university/teaching hospital in the southwestern United States. Possible par-

ticipants were contacted through email announcements and in-person presentations on

the physiological and psychological benefits of nature immersion/Forest Bathing. To be

included in the study, participants needed to be: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) current

faculty of the university’s Health Sciences Center or working as a medical resident at the

teaching hospital, (3) able to physically tolerate a 0.8 km (0.5 mile) walk.

2.3. Interventions

The Forest Bathing walks were conducted through a collaboration with two Forest

Bathing guides who had completed the certification course through the Association of

Nature and Forest Therapy (ANFT). They were hired to be the interveners for the project.

The Forest Bathing walks were initially held at a public open space encompassing ap-

proximately 525 hectares (1300 acres) of mountains and a piñon-juniper forest located

30 min from the university hospital (see Figure 1). The elevation of the intervention area

is approximately 2285 m (7500 feet). The walk began in an open meadow of grama grass

(Bouteloua species) speckled with paintbrush flowers (Castillega species) and overlooked by

several large ponderosa pines (Pinus ponderosa). It then wandered through scattered groves

of one-seed junipers (Juniperus monosperma), pinyon pines (Pinus edulis), and Gambel oak

(Quercus gambelli). The walk concluded at a dramatic rise populated by multiple alligator

junipers (Juniperus deppeana) growing among large boulders, which provided a view of

the forest-covered Sandia mountains. Due to extensive wildfires, public lands were closed

during the period of this study and the final walks were invited to be held on nearby private

land with similar vegetation and terrain. The course of the walk in both locations was less

than 0.8 km (0.5 miles) on a dirt path with some mild variations in grade. Participants were

sent an email with information on the walk as well as suggestions for weather preparedness

(temperatures ranged from approximately 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit) in the

mornings of the first walks to 27 degrees Celsius (80 degrees Fahrenheit) in the afternoons

view of the forest-covered Sandia mountains. Due to extensive wildfires, public lands

were closed during the period of this study and the final walks were invited to be held on

nearby private land with similar vegetation and terrain. The course of the walk in both

locations was less than 0.8 km (0.5 miles) on a dirt path with some mild variations in grade.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 1P9a, r1t4i5c0i5pants were sent an email with information on the walk as well as suggestion4 soff1o1r

weather preparedness (temperatures ranged from approximately 10 degrees Celsius (50

degrees Fahrenheit) in the mornings of the first walks to 27 degrees Celsius (80 degrees

oFfathherelnahstewit)ailnkst)haenadftsearfneotyo.nIsnoafdtdhietiloanst, awsahlkosr)t aPnodwsearPfeotiyn.tInpraedsednittiaotnio,na oshnotrhtePporwacetricPeooinft

FporreessetnBtaatthioinngown athsepproravcidtiecde.oTf hFeorAesNtFBTatghuinidgews satsaprtreodvitdheede.xTpheeriAenNceFTwgituhidinetsrosdtaurctetidonthse,

foexllpoewreiednbcey wanitohriienntrtoatdiounctaionnds,safofelltoywtaeldk,btyo hanelporaiellnptaatritoicnipaanndtssfaefeeltycotmalkfo,rttoabhleelpwaitlhl pthaer-

intitceirpvaenntstiofene.lTcohme pfoarrttaicbilpeawntisthwthereeinguteirdveedntinioan.1T5hme ipnagrtriocuipnadnitnsgwaenrde cgeunidteerdinign eax1e5rcmisien

ingroorudnedritnoghaenldp cseetnttehreinsgtaegxeefrocristehienfoorlldoewr itnogh“eilnpvsietat ttihoensst”awgehfiochr twheerfeololoffweriendg, “ainndviitna-

otridoners”towghuiicdhe winetreentoioffnearledaw, aanrednienssoordf ethretosegnusiedseasinttheentpiaorntaiclipawanatrsemneosvseodf stlhoewsleynasleosnags

ththeeppaathrt.icTihpeasnetsinmviotvateidonsslofwolllyowaleodngthtehsetapnadtha.rdThseeqseueinnvceitaotfioannsAfNolFloTw-beadsetdhewsatalkndanardd

insecqluudeendcenootficainngAaNnFdTi-nbtaesreadctiwngalwk iatnhdthienicrlusudrerdounnodtiicnignsg. Tanhde pinatretircaicptainngtswwiethretbhreoirugsuhrt-

toroguetnhdeirnigns.aTcihreclepaarftteicripeaacnhtsinwveitraetibornoaungdhtwteorgeegthiveerninthae ociprpcloertaufnteirtyetaochshianrveiwtahtiaotnthaenyd

wweerreengoitviecnintgh.eTohpipsoprrtaucntiitcye tsoersvheasretowrheaint tfhorecyewaenrde dneoetipceinngt.hTehcisonpnraeccttiicoensoerfvtehsetsoorceiianl-

gfroorucep,aansdwdelelpaesnmthoedceolnannedctiinosnpoirfethfuerstohceiracl ognronuepct,iaosnswweliltahstmheondaetluarnadl sinusrproiruenfduirnthges.r

TchoenAneNcFtiTonsseqwuiethncteheprnoavtiudreasl soumrreoustnadnidnagrsd.iTzhateioAnNoFf Tthseeiqnuternvceenptiroonviwdhesilseoamlseo satlalonwdainrdg-

thizeatgiuonidoefttohaedinaptetrtvheenstipoenciwfichitlheearlaspoeaultliocwpirnagcttihcesgtuoidtheetopardtaicpipt tahnetsspanecdifeicnvthireornapmeeunttic.

Tphreacfitnicaelsintovithateiopnarwtiacsipfaonrtas 2a0ndmiennv“siritonspmoet”n,t.wThheerefipnaarlticnivpiatanttisohnawd aths efoorpapo2r0tumninty“tsoit

ssitpaont”d, wnohteicree tphaeritricniaptaunrtaslhsaudrrtohuenodpinpgosr.tuTnhietyextopseirtieancdencootnicelutdhedir wnaithuraalgsruatrirtouudnedpirnagcs-.

tiTcheeaenxdpsehriaernecdetceoan. Aclut dtheedewndithofathgreaitnittuedrveepnrtaiocnti,cpeaarntidcisphaanrtesddtiesacu. Asstetdhteheenedxpoef rtiheencine-

totegrevtehnetrioan,dpaasrkteicdipqaunetsstiodnisscuofsstehde AthNeFeTxgpueridieenbcefotoregewthaelkrinagndbaacskkteodgeqtuhesr.tiTohnes eonftitrhee

eAxpNeFriTengcueidweabse3fohre. wGarolkuipnsg obfaFckorteosgteBthaethr.inTgheweanltkireersexwpeerreiemncixeewdassu3chh.thGartotuhpesAofNFFoTr-

geusitdBeawthaisnbglwinadlekdertso wwehriechmpixaertdicsipuachnttshwatetrheewAaNlkFinTggausiadepawrtasofbtlhinedeexdpetorimwhenicthalpgarrotuicpi-

opratnhtescwonertreowl garlokuinpg. as a part of the experimental group or the control group.

FFigiguurere11. .TThheeFFoorreessttBBaaththininggwwaalklksstotoookkpplalacceepprrimimaarriliylyininppoonnddeerroossaappininee, ,ppininyyoonn,,aannddjujunnipipeerr

hhaabbitiatat,t,aassccaannbbeesseeeennininththisisppicictuturereoof fththeeinintetervrvenentitoionnsistiet.e.

22.4.4. .MMeeaassuurreess

DDaattaaccoollelecctteeddfoforrththeesstutuddyyininccluluddeeddththrreeeeeelelemmeenntsts: :((11))ddeemmooggrraapphhiiccininffoorrmmaattiioonn;;

(2(2))twtwoostsatnadnadradridziezdedasasessesmssemnetsntosf obfurbnuorunto;u(3t;) (o3p)eonp-ennd-eenddqeudesqtuioenstsiosonlsicsiotilnicgitfienegdbfeaecdk-

abbaocukt athbeouintttehreveinntteiorvne. ntion.

TThheeOOldldeennbbuurrggBBuurrnnoouuttInInvveenntotorryy(O(OLLBBII))aassseesssmmeennttisisaasstatannddaardrdizizeeddaassseesssmmeenntt

uusseeddtotoaassesesssththeelelveevleol fobf ubrunronuotuitninphpyhsyicsiiacniasnpsrpovroidvindgindgirdeicrtepctatpieantitecnatrcea. rTeh. eThOeLOBILiBsI

aiswaidweliydeulsyeudsmedeamsueraesuorfeboufrnbouurnt obuectabuesceauitsuesietsu1s6espo16sitpivoesliytivaenldy nanegdantievgealytivfoerlmy ufolarmteud-

itleamtesdtoitmemeassutroe emxheaausustrieoneaxnhdaudsisteionngagaenmd endtis[e1n2]g.aTgheemseenittem[1s2f]u.rtThheresdeemitoenmstsraftuertthhaetr

burnout can be interpreted in terms of the “identification continuum”, which provides a

dimension ranging from disengagement to dedication, as well as the “energy continuum”,

which provides a dimension ranging from exhaustion to vigor. The OLBI has been proven

effective for both work and academic settings, and for all employees, not just those in

healthcare [13]. It has been found to have a high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.63), es-

pecially concerning the two dimensions it evaluates: exhaustion (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87)

and disengagement (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81) [12].

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

5 of 11

The Mini-Z is a questionnaire on work-related burnout symptoms, modified from

the MEMO (Minimizing Error Maximizing Outcome) questionnaire, where prior work-

life measures are assessed [14]. The Mini-Z questionnaire includes 10 items that address

job satisfaction, in which participants indicate potential burnout predictors. The Mini-Z

has been evaluated for reliability and validity through the annual administration to all

departments at Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis, MN [15]. Reliability is

reasonable, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8 when participants answer using a 1–5 scale within

the range from strongly disagree to strongly agree, respectively (e.g., “I feel a great deal

of stress because of my job”) [16]. Satisfaction and stress are good predictor variables that

correlate with overall burnout (p < 0.001) [17].

2.5. Analysis

Summary statistics were calculated for interventions and controls and compared prior

to analysis using the Wilcoxon rank-sum and Fisher’s exact tests to confirm the groups

were matched demographically.

We analyzed OLBI scores and Mini-Z scores for all individuals in the sample and

standardized the reversed scores on the OLBI questionnaire prior to analysis so that the scale

was consistent for all questions. Scores for the two questionnaires were tested for normality

and homogeneity of variances using the Shapiro–Wilk and Bartlett’s tests, respectively.

After confirming the data normality and homogeneity of variances, we conducted

Student’s t-tests to determine whether baseline and post-test scores differed within the in-

tervention and control groups, and Welch’s t-tests to determine whether baseline scores for

interventions and controls differed from each other and whether the intervention led to signifi-

cantly different post-test scores for the two study groups. We analyzed both the total scores for

each questionnaire, as well as the OLBI disengagement and exhaustion subdomains. p-values

were adjusted for multiplicity using the Benjamini–Hochberg method.

All data were collected and compiled in REDCap before being exported for analyses

in R version 4.1.1.

3. Results

A total of 34 participants were enrolled in the intervention group and a total of

22 participants were enrolled in the control group. During the study, several participants

were lost to follow-up, and as a result, 10 people from the intervention group and

12 people from the control group were excluded. Participants in the intervention and

control groups were matched for age, gender, ethnicity, and race. See Table 1 for complete

demographic data.

The baseline burnout scores of the control and intervention groups from the pre-test

are similar and show no statistical difference between the two groups. Scores from the

OLBI range from 16 to 64. Past studies have a score of 35 or above as a positive indicator of

burnout [18]. The median scores for the pre-tests and post-tests of both the intervention

group and the control group were all above 35 on the OLBI, which is consistent with the

presence of burnout symptoms in these groups. The Mini-Z evaluates burnout as well as

satisfaction and stress, and a total score of 40 or above is defined as a joyful workplace [19].

Neither the pre-test nor post-test median scores for either group reached this threshold

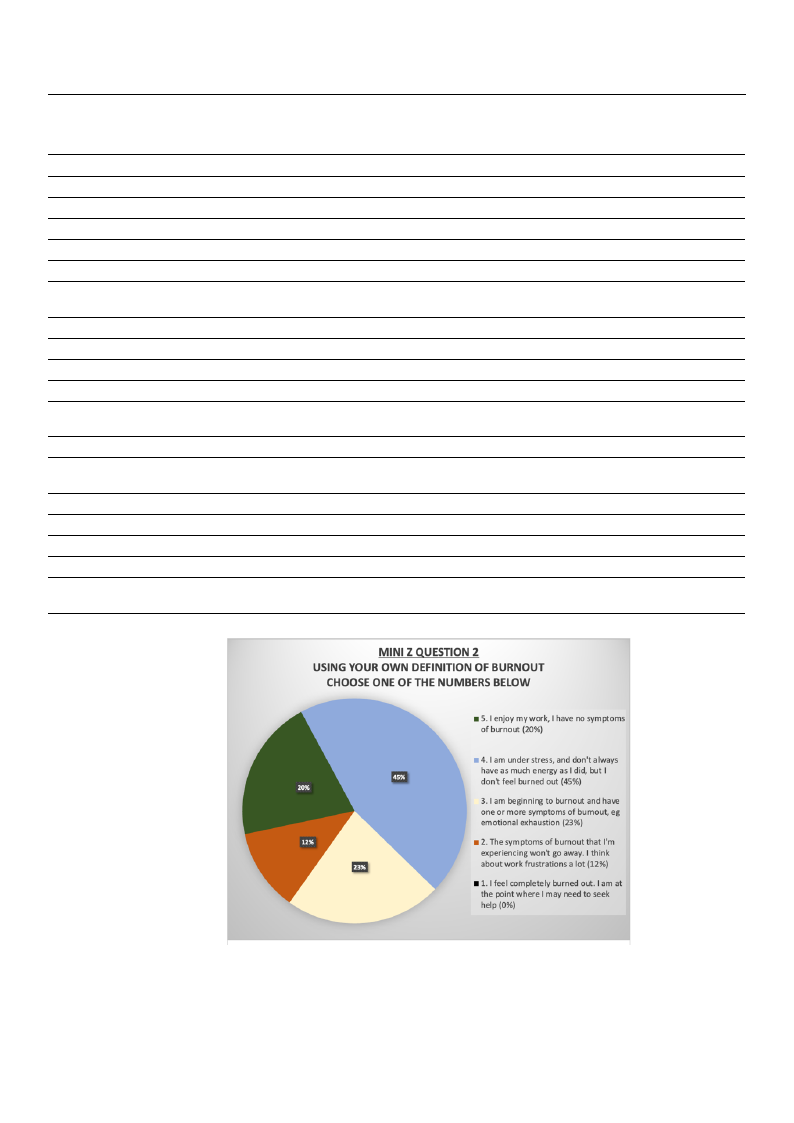

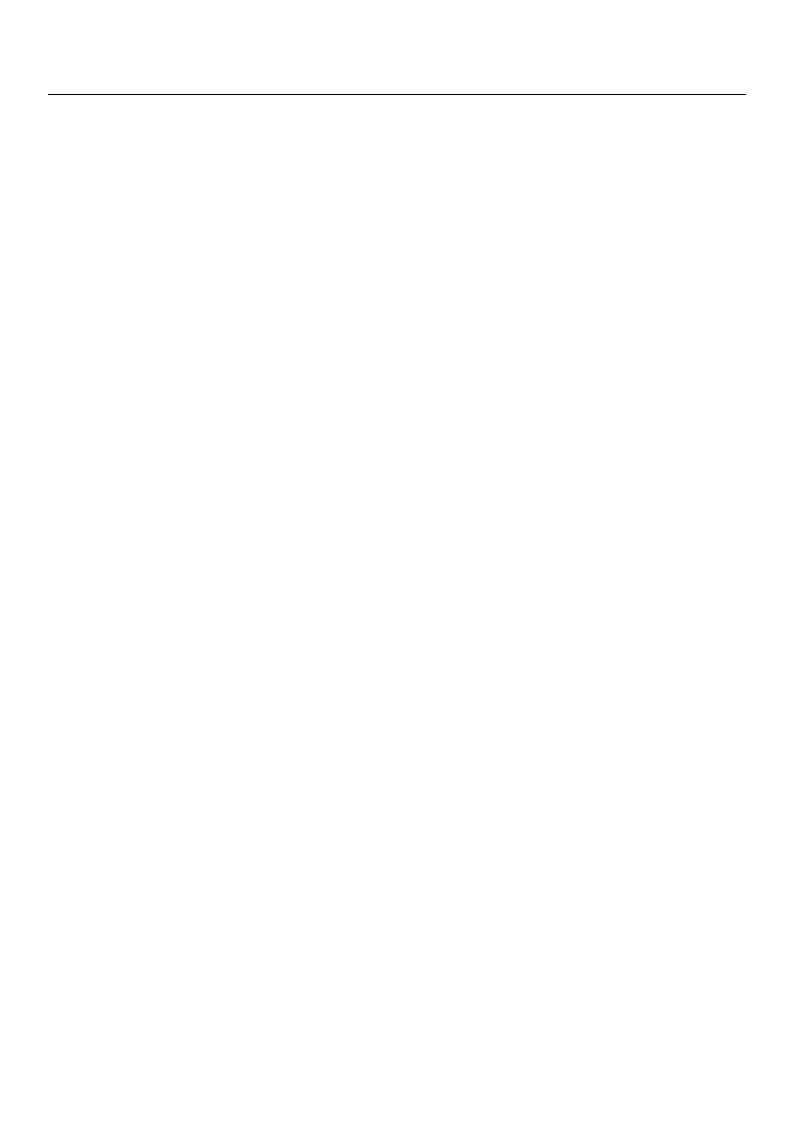

score of 40. Question 2 of the Mini-Z asks the participant to use their own definition of

burnout to choose from five options, and the results can be seen in Figure 2.

When analyzing the data from the OLBI, we did not find a statistically significant

difference between the intervention group and the control group or between the pre-test

and post-test scores for the intervention group (see Table 2). When analyzing the data

from the Mini-Z assessment, there was a slight but statistically significant decrease in the

post-test scores of the intervention group relative to the control group. However, after

adjusting the p-values, this finding was no longer significant. The Mini-Z results similarly

did not demonstrate a significant difference between the pre- and post-test results in either

the intervention or the control group. There was also no significant decrease in post-test

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

6 of 11

scores for the intervention group relative to the control group for the burnout symptom

subdomains of exhaustion and disengagement on the OLBI (see Table 3).

Table 1. Demographic information.

Cases (n = 34) Controls (n = 22)

p

Test for

Group Comparison

Age in Years: Mean

(Standard Deviation)

40.50 (12.7)

38.73 (8.0)

0.81

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum

n (%)

n (%)

Nonbinary

0 (0.0%)

1 (4.6%)

Gender

Female 27 (79.4%)

19 (86.4%)

Male

7 (20.6%)

0.26

2 (9.1%)

Fisher’s exact

None of these

0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%)

Hispanic/Latino

Yes

2 (5.9%)

4 (18.2%)

0.20

No 32 (94.1%)

18 (81.8%)

Fisher’s exact

Asian

5 (14.7%)

2 (9.1%)

Black or Af Am

2 (5.9%)

0 (0.0%)

Race

Nat Am

Nat Hawaiian/PI

2 (5.9%)

0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%)

0.56

Fisher’s exact

White 23 (67.7%)

19 (86.4%)

More than one race

0 (0.0%)

0 (0.0%)

Prefer not to answer

2 (5.9%)

1 (4.6%)

Notes: Participant 55 does not have a group number, so is excluded from the table; participant 24 (case group) chose

Race 3 and Race 5)

Age breakdown

Full Sample

Cases

Controls

Mean Age

39.8

40.5

38.7

Minimum Age

26

26

28

Maximum Age

69

69

65

Sample Size by Age Range

n (%)

n (%)

n (%)

Total

57 (100.0%)

35 (100.0%)

22 (100.0%)

Age 20–29

8 (14.0%)

7 (20.6%)

1 (4.6%)

Age 30–39

23 (40.4%)

12 (35.3%)

10 (45.5%)

Age 40–49

18 (31.6%)

8 (23.5%)

10 (45.5%)

Age 50–49

3 (5.3%)

3 (8.8%)

0 (0.00%)

Age 60–69

5 (8.8%)

4 (11.8%)

1 (4.6%)

Participant 65 is missing age (case group)

Table 2. Pre- and post-test analysis of Oldenburg Burnout Inventory and Mini-Z assessments.

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory Overall Scores (Cases vs. Controls)

Cases

Controls

Test

pre-Test Median score

39.00

42.00

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

post-test median score

38.00

41.00

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

Notes: Reversed scores were recoded prior to analysis.

p-Value

0.07

0.17

adj p-Value

ns

ns

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

7 of 11

Table 2. Cont.

Mini-Z Scores (Cases vs. Controls)

Cases

Controls

Test

p-Value

adj p-Value

pre-test median score

35.00

36.00

Wilcoxon rank-sum test 0.21

ns

post-test median score

34.00

37.00

Wilcoxon rank-sum test 0.03

ns

Significant results are highlighted in red (raw p = 0.05 was used as the threshold for significance).

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory Overall Scores (Change in Scores within Groups)

Pre-Test

Median Score

Post-Test

Median Score

Test

p-Value

adj p-Value

cases (n = 24)

paired t-test

controls (n = 10)

paired t-test

cases (n = 24)

39.50

38.00

Wilcoxon signed-rank test 0.30

ns

controls (n = 10)

41.50

41.00

Wilcoxon signed-rank test 0.44

ns

Notes: Ten cases and twelve controls had pre-test scores, but not post-test scores; one case had a post-test score, but no pre-test

score; these participants were excluded from the paired analyses. Reversed scores were recoded prior to analysis.

Mini-Z Scores (Change in Scores within Groups)

Pre-Test

Median Score

Post-Test

Median Score

Test

p-Value

adj p-Value

cases (n = 24)

33.63

33.92

paired t-test

0.43

0.43

controls (n = 10)

36.10

36.90

paired t-test

0.27

0.27

cases (n = 24)

34.00

34.00

Wilcoxon signed-rank test 0.23

ns

controls (n = 10)

37.00

37.00

Wilcoxon signed-rank test 0.31

ns

Int. J. ENnvoitreosn: .TRenesc.aPsuesblainc dHtewaletlhv2e0c2o2n,tr1o9l,sxhFadOpRreP-EteEsRt sRcoErVesI,EbWut not post-test scores; one case had a post-test score, but no pre-test

score; these participants were excluded from the paired analyses.

FFigiguruer2e. 2R.eRsueltssuflrtosmfraollmpaartlilcipparntiscoipnaMnitnsi-oZnQMueisntiio-nZ2Qcounecsetrinoinng2bucornnocuetrsnyimnpgtobmusr.nout symptom

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of participating in a Shinr

intervention on the level of burnout of physicians and other healthcare workers. F

that would have clearly demonstrated that this therapy can decrease burnout sy

would have shown a significant decrease in burnout scores on the post-test relati

pre-test in the intervention group on either the OLBI or the Mini-Z tests, or a sig

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

8 of 11

Table 3. Analysis of Oldenburg Burnout Inventory Subdomains.

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory Subscores (Cases vs. Controls)

Cases

Controls

Test

p-Value

Disengagement

pre-test median score

18.00

20.00

Wilcoxon rank-sum test 0.07

post-test median score

18.00

20.00

Wilcoxon rank-sum test 0.30

Exhaustion

pre-test median score

20.50

22.00

Wilcoxon rank-sum test 0.10

post-test median score

20.00

21.50

Wilcoxon rank-sum test 0.04

Notes: Reversed scores were recoded prior to analysis. Significant results are highlighted in red

(raw p = 0.05 was used as the threshold for significance).

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory Subscores (Change in Scores within Groups)

Pre-Test

Median Score

Post-Test

Median Score

Test

p-Value

Disengagement

cases (n = 24)

19.00

18.50

Wilcoxon rank-sum test 0.33

controls (n = 10)

20.00

20.00

Wilcoxon rank-sum test 0.88

Exhaustion

cases (n = 24)

20.00

20.00

Wilcoxon signed-rank test 0.34

controls (n = 10)

21.50

21.50

Wilcoxon signed-rank test 0.16

Notes: Ten cases and twelve controls had pre-test scores, but not post-test scores; one case had a post-test score,

but no pre-test score; these participants were excluded from the paired analyses. Reversed scores were recoded

prior to analysis.

adj p-Value

ns

ns

ns

ns

adj p-Value

ns

ns

ns

ns

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of participating in a Shinrin-Yoku

intervention on the level of burnout of physicians and other healthcare workers. Findings

that would have clearly demonstrated that this therapy can decrease burnout symptoms

would have shown a significant decrease in burnout scores on the post-test relative to the

pre-test in the intervention group on either the OLBI or the Mini-Z tests, or a significant

decrease in the burnout scores on the post-test for the intervention group relative to the

control group. The latter was initially detected for the Mini-Z test alone, although this

finding was then negated when the p-value was adjusted. This result may, in part, be due

to a loss of power in the context of a smaller sample size. Although the results from the

Mini-Z test are suggestive that the intervention decreased aspects of burnout, it would

require further studies with a larger sample size to better determine this. Overall, the

results from this study do not demonstrate a significant impact on burnout scores from

these two tools, resulting from a Forest Bathing intervention.

The data add to the body of evidence that burnout symptoms are prevalent among

healthcare providers. The median scores from the OLBI are consistent with burnout

symptoms in both the intervention group and the control group. On question 2 of the

Mini-Z test, 34% of participants reported some symptoms of burnout. This includes 12%

who reported persistent burnout symptoms that do not go away.

The post-intervention data also gathered subjective comments on the mental state of

the Shinrin-Yoku participants. Twenty participants responded with comments. Nineteen of

these comments focused on feeling more relaxed, more peaceful, calmer, more appreciative,

and less anxious. Only one comment stated that they did not detect a difference in their

internal state after the walk.

These results that do not demonstrate a significant difference in burnout scores after

a Shinrin-Yoku intervention appear to be in contradiction to these subjective comments

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

9 of 11

which report the psychologically calming benefits of this therapy. These findings also

appear in contradiction to the results from other studies that showed participating in

Shinrin-Yoku can alleviate symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, which are all

connected to symptoms of burnout [2]. This then raises the question of the nature of

healthcare worker burnout and how it is fundamentally different from either a state of

mood or a psychiatric disorder. It can be described as a reactive syndrome that develops

over a prolonged period due to systemic issues, bureaucratic burdens, and repetitive moral

injury. One of the participants of this study put this succinctly when they wrote, “I felt very

relaxed after forest therapy. Then I came home and did 6 h of work that needed to be done

before Monday, and then took the survey. I generally feel stressed on Sunday afternoons

trying to finish all the things that didn’t get done during the week and forest therapy didn’t

take those things away.” It is likely that, for some, their experience of a Shinrin-Yoku walk

highlighted rather than relieved their sources of burnout symptoms. It is also of note that

recruitment was a significant challenge for this study, not due to a lack of interest, but rather

due to difficulties for many interested physicians in finding sufficient time off from their

clinical duties to join a Shinrin-Yoku walk. This represented an insurmountable obstacle

for many of the 79 people who originally signed up as interested in the study. As one

participant wrote after their Shinrin-Yoku walk, they were “more aware of how exhausted I

am, the degree of anxiety I carry around. I also felt more at peace and like I might be able to

tolerate the intense 120+ hour schedule I have for the next 2 weeks”. This articulates both

the challenge in addressing the source of burnout symptoms and the need for interventions

such as Shinrin-Yoku for providing the subjective sense of peace that is so often lacking

in healthcare. It is clear from the subjective responses that many of the participants on

these Shinrin-Yoku walks found them to be of value to their mental wellbeing despite not

significantly impacting their burnout symptoms.

When considering why the study participants reported feelings of “peace” that did not

translate to decreased burnout scores, it is important to note that Shinrin-Yoku is often pro-

posed to be an ongoing practice rather than a one-time intervention [20]. The distinguished

Japanese researchers of this therapy, Dr Yoshifumi Miyazaki and Dr Qing Li, as well as

Amos Clifford, the founder of the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy, propose that

Shinrin-Yoku be incorporated into the participant’s life as an ongoing practice [11,20]. In a

way similar to psychotherapy, yoga, and tai chi, it is understandable that a single session

of Shinrin-Yoku would not produce a measurable improvement in a chronic condition,

such as healthcare worker burnout. This, as well as the small sample size, were significant

limitations for this study which introduced this therapy to dozens of healthcare workers,

but did not assess the long-term impact of using this therapy over months and years on

burnout symptoms.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the data from this randomized controlled trial did not demonstrate

a change in burnout symptoms from participating in a single Shinrin-Yoku walk when

compared to baseline burnout scores or when compared to a control group. This does not

mean, however, that there is no possible role for Forest Therapy in providing relief from

burnout symptoms. The subjective comments from participants after the Shinrin-Yoku

walk are consistent with many previous studies which demonstrated the ability of this

practice to decrease stress and anxiety [2]. It is unlikely that anyone can experience burnout

without simultaneously experiencing stress and anxiety. Burnout symptoms accumulate

over time, and thus, it is reasonable to suppose that alleviating burnout will also take

time. An ongoing practice of Forest Therapy may very well erode the severity of burnout

symptoms through cumulative improvements in stress and anxiety levels. Therefore, there

is a need for further research on the impact of Shinrin-Yoku on burnout symptoms in

healthcare workers over a prolonged period and as a regular practice.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

10 of 11

Author Contributions: J.K., H.H.R. and M.E.H. All contributed to the conceptualization, methodol-

ogy, investigation, resources, original draft preparation, review and editing, visualization, supervision,

and funding acquisition. C.W. contributed to the investigation and draft review and editing. J.G. con-

tributed to the software, validation, formal analysis, and data curation. All authors have read and

agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This project was funded by an internal grant from the University of New Mexico Faculty

Lifecycle Scholarship Fund by the Office of Faculty Affairs and Career Development.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the

Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of New

Mexico Health Sciences Center (21-419, approved on 2/1/22).

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: Raw data can be obtained by contacting the primary author. All data

will be de-identified to protect participant privacy.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge and express gratitude to Elizabeth

Lawrence, Akshay Sood, and the University of New Mexico faculty, residents, and staff who provided

support for the study; the city of Albuquerque Open Space Division, Leila Von Stein, and the Blue

Desert Retreat Center for providing the maintained trails we used for the Shinrin-Yoku walks; and

our amazing Forest Therapy guides, Sally Stevens and Alix Peters.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Tchounwou, P. Environmental Research and Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2004, 1, 1–2. [CrossRef]

2. Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-yoku (Forest bathing) and nature therapy: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Environ.

Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

3. Furuyashiki, A.; Tabuchi, K.; Norikoshi, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Oriyama, S. A comparative study of the physiological and psychological

effects of forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) on working age people with and without depressive tendencies. Environ. Health Prev. Med.

2019, 24, 46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D.; Carlone, L.; Maggini, V.; Firenzuoli, F.; Bedeschi, E. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on individual

well-being: An umbrella review. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 32, 1842–1867. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

5. Dewa, C.S.; Loong, D.; Bonato, S.; Trojanowski, L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms

of safety and acceptability: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015141. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

6. Rodrigues, H.; Cobucci, R.; Oliveira, A.; Cabral, J.V.; Medeiros, L.; Gurgel, K.; Souza, T.; Gonçalves, A.K. Burnout syndrome

among medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206840. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

7. Kunz, M.; Strasser, M.; Hasan, A. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on healthcare workers: Systematic comparison

between nurses and medical doctors. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 413–419. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

8. Busireddy, K.R.; Miller, J.A.; Ellison, K.; Ren, V.; Qayyum, R.; Panda, M. Efficacy of Interventions to Reduce Resident Physician

Burnout: A Systematic Review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2017, 9, 294–301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

9. Mari, S.; Meyen, R.; Kim, B. Resident-led organizational initiatives to reduce burnout and improve wellness. BMC Med. Educ.

2019, 19, 437. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

10. Jung, W.H.; Woo, J.-M.; Ryu, J.S. Effect of a forest therapy program and the forest environment on female workers’ stress. Urban

For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 274–281. [CrossRef]

11. Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides and Programs. Available online: https://www.natureandforesttherapy.org/

(accessed on 24 May 2021).

12. Tipa, R.O.; Tudose, C.; Pucarea, V.L. Measuring Burnout Among Psychiatric Residents Using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory

(OLBI) Instrument. J. Med. Life 2019, 12, 354–360. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

13. Reis, D.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Tsaousis, I. Measuring job and academic burnout with the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI):

Factorial invariance across samples and countries. Burn. Res. 2015, 2, 8–18. [CrossRef]

14. Olson, K.; Sinsky, C.; Rinne, S.T.; Long, T.; Vender, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Bennick, M.; Linzer, M. Cross-sectional survey of workplace

stressors associated with physician burnout measured by the Mini-Z and the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Stress Health J. Int. Soc.

Investig. Stress 2019, 35, 157–175. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

15. Khanna, N.; Montgomery, R.; Klyushnenkova, E. Joy in Work for Clinicians and Staff: Identifying Remedial Predictors of Burnout

from the Mini Z Survey. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2020, 33, 357–367. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

16. Linzer, M.; Poplau, S.; Babbott, S.; Collins, T.; Guzman-Corrales, L.; Menk, J.; Murphy, M.L.; Ovington, K. Worklife and Wellness

in Academic General Internal Medicine: Results from a National Survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 1004–1010. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14505

11 of 11

17. Rohland, B.M.; Kruse, G.R.; Rohrer, J.E. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory

among physicians. Stress Health 2004, 20, 75–79. [CrossRef]

18. Summers, R.F.; Gorrindo, T.; Hwang, S.; Aggarwal, R.; Guille, C. Well-Being, Burnout, and Depression among North American

Psychiatrists: The State of Our Profession. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 955–964. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

19. Linzer, M.; Smith, C.D.; Hingle, S.; Poplau, S.; Miranda, R.; Freese, R.; Palamara, K. Evaluation of Work Satisfaction, Stress, and

Burnout among US Internal Medicine Physicians and Trainees. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2018758. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

20. Miyazaki, Y. The Japanese Art of Shinrin-Yoku, Forest Bathing; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2018.