Article

The Effects of a Short Forest Recreation Program on

Physiological and Psychological Relaxation in Young

Polish Adults

Ernest Bielinis 1,* , Lidia Bielinis 2, Sylwia Krupin´ ska-Szeluga 2, Adrian Łukowski 3,4 and

Norimasa Takayama 5

1 Department of Forestry and Forest Ecology, Faculty of Environmental Management and Agriculture,

University of Warmia and Mazury, Pl. Łódzki 2, 10-727 Olsztyn, Poland

2 Department of General Pedagogy, Faculty of Social Science, ul. Z˙ ołnierska 14, 10-561 Olsztyn, Poland;

lidia.bielinis@uwm.edu.pl (L.B.); krupinska_sylwia91@wp.pl (S.K.-S.)

3 Institute of Dendrology Polish Academy of Sciences, Parkowa 5, 62-035 Kórnik, Poland;

adrian.lukowski@gmail.com

4 Faculty of Forestry, Poznan´ University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 71c, 60-625 Poznan´ , Poland

5 Environmental Planning Laboratory, Department of Forest Management, Forestry and Forest Products

Research Institute in Japan, 1 Matsunosato, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8687, Japan; hanri@ffpri.affrc.go.jp

* Correspondence: ernest.bielinis@uwm.edu.pl; Tel.: +48-603-809-211

Received: 14 October 2018; Accepted: 5 January 2019; Published: 7 January 2019

Abstract: Forest recreation is an activity that could be successfully used to alleviate negative

symptoms of stress in individuals. Multiple positive psychological and physiological effects have

been described in the literature, especially regarding works describing research from Asian countries

such as Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. In East-Central Europe, however, the effectuality of forest

recreation has not been addressed in scientific research. Thus, a special recreation program was

developed, and its usability was examined with the involvement of 21 young Polish adults. A pre-

and post-test design was used, wherein four psychological questionnaires were applied (Profile of

Mood States, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Restorative Outcomes Scale, Subjective Vitality

Scale), and physiological measures were assessed (pulse rate, blood pressure) before and after the

program. A field study was also conducted at the nature reserve Redykajny, near the suburban

forest of the city of Olsztyn. The recreational program had a significant impact on psychological

and physiological parameters. After recreation, the negative mood markers of the negative affect

decreased and the positive affect, including restoration and vitality, increased. Furthermore, pulse

rates, systolic blood pressures, and mean arterial pressures of the participants were significantly

lower after the program. These results reveal that the short forest recreation program may be effective

in reducing negative symptoms of stress.

Keywords: emotional affect; blood pressure; forest bathing; forest therapy; mood; nature reserve;

pulse rate; restoration; Shinrin-Yoku; stress reduction

1. Introduction

Recreation is a wholesome activity undertaken for pleasure, as well as any action that refreshes

the mental attitude of an individual [1]. Forest recreation aimed at improving physical and mental

health, as well as reducing stress, is called “forest therapy” (also “forest bathing”, from Japanese

Shinrin-Yoku) [2,3]. This type of forest recreation is well known in Japan and in some other Asian

countries, where it is practiced as a remedy for problems induced by stress [4]. The importance of forest

therapy in these countries is high, as shown by the multiplicity of organizations involving individuals

Forests 2019, 10, 34; doi:10.3390/f10010034

www.mdpi.com/journal/forests

Forests 2019, 10, 34

2 of 13

and professionals interested in this topic (e.g., the Forest Therapy Society, the International Society of

Nature, and Forest Medicine).

To achieve a broad range of effects on health improvements in practice, researchers have developed

different “forest recreation programs”. The effects of these programs on humans have been tested for

short-term, middle-term, and long-term scenarios. One short recreation program (a few minutes) had

a positive influence on mood states and on the cardiovascular relaxation of Japanese participants [5].

Similarly, a one-day forest therapy study conducted in Japan significantly influenced mood states and

decreased pulse rate [6]. Another short-term program conducted in a young conifer forest in Japan

demonstrated that viewing and walking in the forest affected the psychology of participants, increasing

their comfort and making them feel refreshed and calm. Physiological indices were also affected, as this

program resulted in lowered diastolic blood pressure and pulse rate in the participants [7]. A two-day

forest therapy program conducted in urban parks in China had an antianxiety effect [8], and another

two-day forest therapy program conducted in a recreational forest in Taiwan had a significant positive

influence on the mood states of women involved in the study, causing a decrease in both anxiety

levels and systolic blood pressure [9]. A five-day forest therapy program conducted in Japan also

had a positive influence on the mood states of the participants [10]. Forest recreation has also been

reported to be effective in increasing human natural killer cell activity and expression of anticancer

proteins [11–13], and to affect human immune function [14], as well as cardiovascular and metabolic

parameters [15]. These forest recreation programs appear to have a broad spectrum of beneficial effects on

the physiological and psychological parameters measured in Asian participants. Little is known, however,

regarding the effectiveness of forest recreation programs on individuals living in East-Central Europe.

One study has tested the effects of 15 minutes of viewing the forest on psychological relaxation [16],

but there have been no reports of experiments investigating the effects of longer exposure to the forest

environment or testing the effects of forest recreation programs conducted in this region.

Estimating the effects of forest recreation on human health is possibly of high importance to

East-Central Europe citizens. Expectations regarding the functions of forests have recently changed in

this region, whereas the status of “other than wood production activity in the forest” has increased

as well [17]. The growing importance of the social function of a forest, especially its usefulness for

recreation, is more frequently expected by society, which has been reflected in an increasing number of

scientific reports addressing this topic. The importance of forest recreation is also growing in Poland,

where forests cover 29.5% of the land area and the population’s awareness of the positive influence of

this environment on health is increasing.

Polish forests are of medium age, with most trees being 41–80 years of age. Forest management

in Poland is conducted in a close to natural, sustainable way. Thus, there are not many deforested

areas, and forest stands are suitable for forest recreational activities. Various kinds of activities are

popular in Polish forests, with forest walks and mushroom picking being the most popular. In addition,

individuals appreciate forest areas and perceive them as useful for forest recreation. Forest therapy

roads are not designed, however, and the effectuality of forest therapy programs is not tested, while

the severity of stress increases in workers, and their mental health declines. One of the main aims of

the present study was therefore to verify the hypothesis that a short-term forest recreation program can

influence the physiological and psychological relaxation of participants. The second hypothesis tested the

usefulness of a forest near Olsztyn, on the nature reserve Redykajny, for forest recreation. The positive

influence of this environment on the tested parameters was identified as a needed, desired effect, which

could indicate that the nature reserve Redykajny is a proper area for conducting forest recreation

programs. To verify these two hypotheses, the influence of a short-term (few hours) forest recreation

program conducted at the reserve was estimated for young and working or learning Polish citizens.

In summary, the purposes of conducting and presenting this study were: (i) To fill in the gaps in

knowledge regarding how effective a forest recreation program might be on the psychological and

physiological relaxation of adults in East-Central Europe, and (ii) to assess the usefulness of the tested

area for conducting forest recreation programs affecting the psychological and physiological relaxation

of participants.

Forests 2019, 10, 34

3 of 13

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty-one participants living in the city of Olsztyn were recruited for this study. Persons

recruited for the study were former friends of researchers and their acquaintances who agreed

to participate in the study. Twelve students from the University of Warmia and Mazury were

selected (not from the forestry course). To avoid having only student sample, an additional nine

working, non-student persons were recruited. Only young adults between the ages of 21 and 29 years

participated in this study (demographics of the participants are presented in Table 1). Non-healthy

adults, with mental or physical diseases or metabolic syndromes, were excluded from the study.

Because it is less likely for young people to be taking medications, and because they appear to be

more stable in terms of their physical condition, we assumed that individual differences among them

would be smaller than in the case of older people. This group was therefore considered homogenous.

An optimal sample size was used to balance the need for quick testing and the need to obtain

reliable results. Additionally, the results of other researchers have indicated that a sample size of

12–16 participants in forest therapy experiments is enough to draw significant conclusions [10,18].

Thus, our group of 21 individuals was large enough to obtain valuable information.

Before the experiment, the participants were informed that they would be asked to contribute to a

research study on “forest recreation”, and informed consent was obtained. The participants were also

informed of the research plan on the first and second days of research. All procedures performed in

this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Polish Committee of Ethics in Science

and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Table 1. Demographic information of study participants.

Parameter

Value (Mean ± SD)

Total sample number

Sex

Activities

Age (years)

Weight (kg)

Height (cm)

BMI (kg/m2)

21

Female = 9, male = 12

Students = 12, workers = 9

23.86 ± 2.67

76.09 ± 13.95

172.81 ± 7.12

25.38 ± 3.78

Note: BMI: Body Mass Index; SD: Standard Deviation.

2.2. Study Sites

The indoor pre-test experiment was conducted in an apartment in the city of Olsztyn. The field

post-test experiment was conducted in the forested area of the nature reserve Redykajny, which covers

14 ha in the northwest part of the suburban forest of Olsztyn. Meteorological data on the pre-test

day and post-test day were collected from the meteorological station in Olsztyn-Mazury (location:

53◦28 50” N, 20◦56 10” E). The mean annual temperature in Olsztyn is 7.9 ◦C, the mean annual

precipitation is 635 mm, and the altitude is 139 m. On the pre-test day, the average temperature was

20 ◦C, atmospheric pressure was 1018 hPa, the speed of the southeast wind was 14 km/h, and humidity

was 50%. Cloudiness was absent, and no precipitation was observed. On the post-test day, the average

temperature was 25 ◦C, atmospheric pressure was 1014 hPa, humidity was 46%, the speed of the east

wind was 22 km/h, and humidity was 46%. Cloudiness was low, and no precipitation was observed.

Sound levels and illuminance were measured on both experimental days with a Huawei P9

Lite smartphone (Huawei, China) using the “Sound Meter” and “Light Meter” applications, both of

which have been shown to be excellent applications comparable to a professional laboratory sound

analyzing instrument [19,20], and using a professional illuminance analyzing instrument. The mean

sound level (±SD) measured with the “Sound Meter” application in the indoor environment was

47.86 ± 10.24 dB, whereas the mean sound level in the forest environment was 38.08 ± 5.19 dB.

Forests 2019, 10, 34

4 of 13

The mean illuminance in the indoor environment measured with the “Light Meter” was 710 ± 493.79 lx,

whereas the mean illuminance in the forest environment was 37,755.24 ± 45,561.35 lx. Physical and

meteorological parameters concerning this study are presented in Table 2. Sound levels and illuminance

were measured 15 times in a random part of each environment (in one room of the apartment and in

each forest area) at random times during the experimental procedure.

Table 2. Physical and meteorological parameters during the forest therapy experiment.

Parameter

Sound level (dB)

Illuminance (lx)

Forest tree density (n/ha)

Parameter

Temperature (◦C)

Humidity (%)

Cloudiness

Wind speed (km/h)

Room Environment

(Mean ± SD, n = 15)

47.86 ± 10.24

710 ± 493.79

-

The Day before

Forest Recreation

20

50

Absent

14

Forest Environment (Mean ± SD, n = 15)

Area 1

Area 2

Area 3

37.33 ± 4.85

23,657.67 ± 24,959.55

600

39.4 ± 4.81

88,515.27 ± 38,563.678

200

37.53 ± 5.94

1092.8 ± 467.83

1200

The Day of Forest Recreation

25

46

Small

22

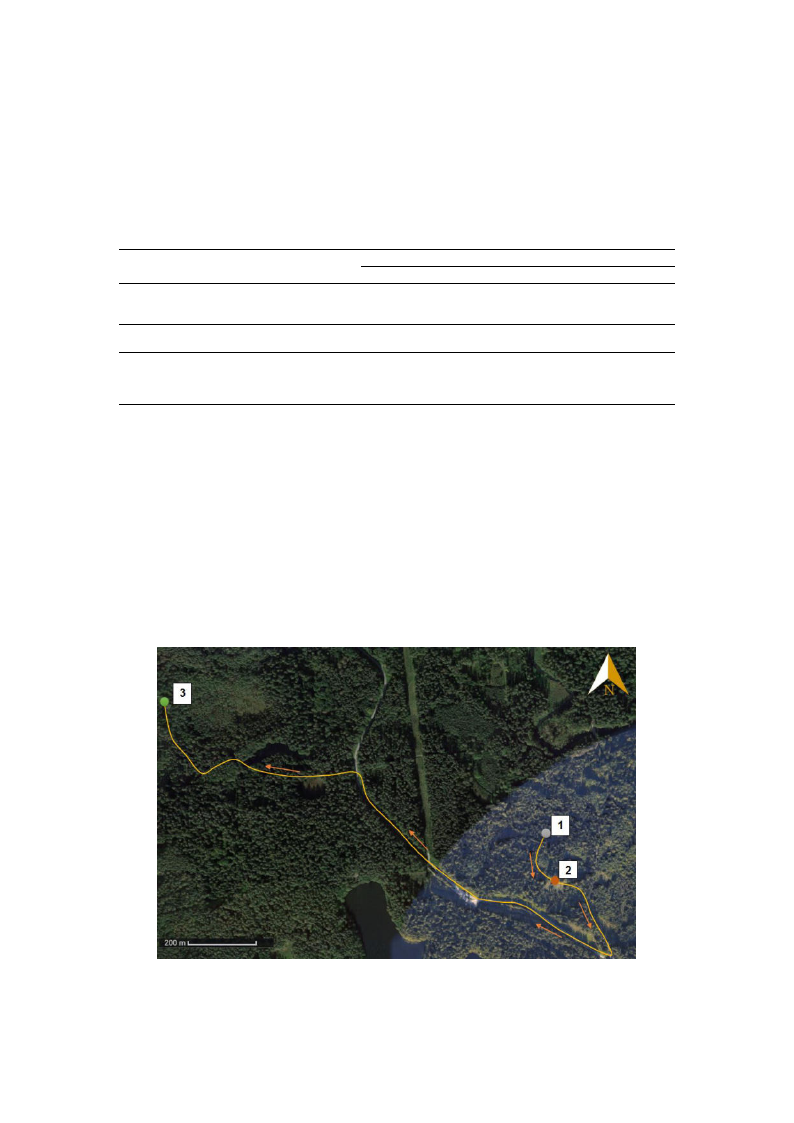

The forest areas used in this study, numbered from 1 to 3 (Figure 1), were parts of the nature

reserve Redykajny. The whole area of the reserve is covered mainly by 85- to 130-year-old Picea abies

(L.) H. Karst. and 80- to 180-year-old Pinus sylvestris. L. Area 1 is covered by 105-year-old P. abies

(40%), 180-year-old P. sylvestris (40%), 85-year-old P. abies (20%), and a mixture of additional species

(Quercus robur L., Fagus sylvatica L.: 20%). Species composition in Area 2 is the same, but a less-dense

part of the stand was selected—an area previously prepared by foresters for regeneration, leaving

200 residual trees/ha. Area 3 is covered by 60-year-old, 90-year-old, and 120-year-old P. abies (10%, 50%,

and 20%, respectively), along with Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn., Betula pendula Roth and 80-year-old

P. abies (10% each). The ground in the part of the reserve intended for the forest recreation program is

covered with moss and herbaceous vegetation. All views in this selected place were of the forest alone,

undisturbed by buildings or other objects.

Figure 1. The walking route at the nature reserve Redykajny during the forest recreation program.

Colored points indicate places intended for recreational activities. Points of stay are numbered from

the start (Area 1) to the end (Area 3) of the walk. Map provided by F. Ordon.

–

recreation program was applied. The participants’ psychological and physiological responses were

Forests 2019, 10, 34

5 of 13

2.3. Procedure

In this study, a pre-test–post-test design with a short, one-day intervention of the forest recreation

program was applied. The participants’ psychological and physiological responses were measured

indoors on the day before forest recreation, and then under field conditions on the next day, directly

after the forest recreation. On the pre-test day, before the pre-test, the subjects simply participated

in their ordinary, everyday activities. These activities did not consist of performing tasks identical

to those planned for the “forest recreation”. The same time of each day (15:45–16:15) was chosen for

psychological and physiological measurements to achieve comparable results. Measuring at different

times during the day may cause biased results, due to the effect of the circadian rhythm on humans [21],

and thus we chose the same time of measurement for each day. As the intervention was planned for

several hours, the pre-test was carried out in the same hour as the post-test, at the same time of the day,

but the day before (to avoid performing measurements during different hours of the biological clock).

The participants took part in a single exit to the forest (in a single intervention) which is a common

practice in forest therapy research. Their relaxation at individual stages of the intervention took place

in privacy, and each participant chose a separate place a few meters away from other participants

to be able to relax and follow the instructions of the researcher leading the therapy. The conducted

forest recreation program engaged participants’ senses: Auditory (e.g., listening to the sounds of the

forest in a sitting position with closed eyes), visual (viewing the forest), and tactile (touching forest

items, cuddling up to trees). The sense of smell was engaged during all activities, which is illustrated

in Figure 2. The activities were repeated three times, once in each of the selected forest areas, which

participants moved among on foot. The walking route and place of stay for forest recreation are

shown in Figure 1. The time spent standing in the forest throughout the forest recreation program was

approximately 5 h. In addition, participants could relax throughout the intervention, which made

the intervention not an effort. The schedules of indoor and field experiments are shown in Table 3.

The purpose of choosing three different activities in three different parts of the forest was to replicate a

previous study, where different activities were repeated in different forest areas [6], and this scheme

was applied to obtain an effect of forest therapy in this study comparable to that observed in the

previous study. The three different localities intended for forest recreation provided the participants

with a variety of views and experiences that could be useful in recreation and could increase the

recreational effect.

Table 3. Schedule of the indoor (first day) and field (second day) experiments.

Date

12 May 2018 (Saturday)

13 May 2018 (Sunday)

Time

15:45~16:15

11:30~12:00

12:00~12:15

12:15~12:30

12:30~12:45

12:45~13:00

13:00~13:05

13:05~13:20

13:35~13:50

13:50~14:05

14:05~14:20

14:20~14:30

14:30~14:45

15:00~15:15

15:15~15:30

15:30~15:45

15:45~16:15

Activity

Psychological and physiological response pretest

Orientation, traveling to Area 1

Listening to the sounds of the forest

Viewing at the forest

Touching forest items

Cuddling up to a tree

Traveling to Area 2

Listening to the sounds of the forest

Viewing at the forest

Touching forest items

Cuddling up to a tree

Traveling to Area 3

Listening to the sounds of the forest

Viewing at the forest

Touching forest items

Cuddling up to a tree

Psychological and physiological response post-test

Forests 2019, 10, 34

6 of 13

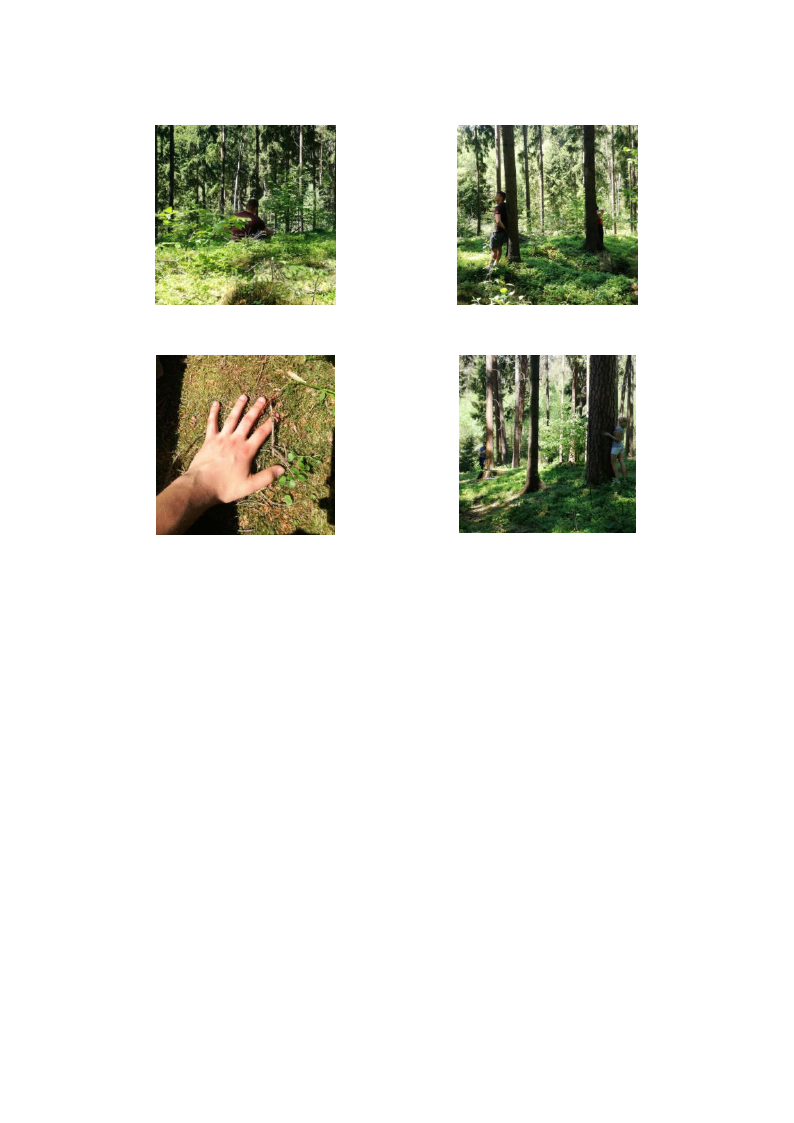

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Figure 2. Activities undertaken during a forest recreation intervention: (a) Listening to the sounds

of the forest; (b) viewing the forest; (c) touching forest items; (d) cuddling up to a tree. All photos

provided by F. Ordon.

2.4. Measurements

Four psychological questionnaires were used to measure the psychological effect of forest therapy

on the participants. In the Polish language, a 65-item version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS)

questionnaire was chosen [22] to assess the program’s effect on the emotional states of participants.

POMS is a reliable and valid measure of psychological distress [23], and has previously been used to

estimate the influence of the forest environment on mood states [16,24,25]. This tool measures six mood

states: Confusion, fatigue, anger or hostility, tension or anxiety, depression or dejection, and vigor.

A five-point Likert scale was used for each item to evaluate participants’ mood states, with each item

assessed from 0 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree).

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) was used to measure the emotional affect of

each participant. PANAS questionnaires contain 20 items, with 10 items addressing negative affect

and 10 addressing positive affect. The reliability and validity of the PANAS is high [26], and its use

for forest recreation assessments has been previously described [16,25]. A Polish adaptation of this

schedule was used in the current study [27]. Each item was assessed using a five-point Likert scale

(1—strongly disagree, 5—strongly agree). The PANAS scale was used for this study because it is often

used in research on forest therapy.

The Restorative Outcome Scale (ROS) is a reliable and valid tool developed based on previous

research concerning restorative phenomena [28,29]. Originally, this scale was used to assess humans’

restoration in the forest environment [16,25]. It contains six to nine items, with each item assessed by

participants on a seven-point Likert scale (1—not at all, 7—completely). In this study, we used a scale

modified for forest experiments by Takayama et al. [26]. The scale with modifications was adapted

Forests 2019, 10, 34

7 of 13

into Polish [16]. In this study, “Restorative Outcome” was measured (i.e., a general restorative effect

that was obtained as a result of the intervention).

The Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS) [30] was used for vitality assessment. A version with four

items, adapted to research in the forest environment, [25] was used in this study. The four items

were assessed by participants using a seven-point Likert scale (1—not at all, 7—completely), with one

inversely scored item. A Polish version was applied in this research [16]. Four common items were

chosen: “I feel alive and vital”, “I don’t feel very energetic”, “I have energy and spirit”, and “I look

forward to each new day”.

Different time frames may be used in the POMS, PANAS, ROS, and SVS questionnaires, but in

this study, the time frame “at the present moment” was applied. The raw data from each questionnaire

were used for statistical purposes.

The physiological indices measured in this study were parameters connected to blood circulation

in the body. All were measured with portable devices on the day before the forest recreation program

and directly after the forest recreation program. Participants’ pulse rates (in bpm), systolic blood

pressures (SBPs), and diastolic blood pressures ((DBPs), both in mmHg) were measured with a blood

pressure monitor (Tech-Med, TMA 10-PRO, Beijing, China). Measurements were conducted in a sitting

position, in the same arrangement pre-test and post-test. The relative value of mean arterial pressure

(MAP) was calculated after measurements as ((2 × DBP) + SBP)/3 [31].

2.5. Data Analysis

Raw data from psychological questionnaires and raw data from physiological measures were

used for statistical analyses. MAP was calculated in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), as were

all mean values and SD values. A paired sample t-test was applied to compare pre-test and post-test

measurements. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics Version 24 (IBM, Armonk,

NY, USA). Cohen’s d was used to estimate the effect size, with a Cohen’s d close to 0.2 described as a

weak effect, close to 0.5 as a medium effect, and close to 0.8 as a strong effect.

3. Results

Results of the paired sample t-test examining the psychological differences before (pre-test) and

after (post-test) the forest recreation program are presented in Table 4. There was a significant decrease

in four negative mood states of the POMS scale after the program, including confusion (t = 2.392,

p < 0.05), anger or hostility (t = 2.838, p < 0.05), tension or anxiety (t = 3.185, p < 0.01), and depression or

dejection (t = 2.823, p < 0.05). Regarding emotional affect, the level of negative aspects in participants

decreased significantly after the forest recreation program (PANAS negative: t = 2.905, p < 0.01).

In turn, the effect of participant restoration increased significantly post-test (ROS: t = −5.225, p < 0.001).

Furthermore, there was a significant increase in participants’ vitality levels post-test (SVS: t = −3.759,

p < 0.01), in comparison to those levels before the test.

Results of the paired sample t-test regarding physiological differences pre- and post-test are

presented in Table 5. There was a significant decline in three physiological indices after the forest

recreation program: Pulse rate (t = 3.581, p < 0.01), SBP (t = 3.366, p < 0.01), and MAP (t = 2.537, p < 0.05).

There were no significant differences in participants’ DBPs pre- and post-test.

Forests 2019, 10, 34

8 of 13

Table 4. Effects of the forest recreation program on emotional state, emotional affect, restoration,

and vitality.

Pre-Test

Post-Test

Psychological Indices

t

Mean ± SD Mean ± SD

p

Rate of

Change (%)

ES

Mood State (POMS)

Confusion

1.10 ± 0.63 0.71 ± 0.53 2.392 0.027 *

−35.8

1.07

Fatigue

1.22 ± 0.76 0.81 ± 0.79 1.817

0.084

−33.52

0.81

Anger or hostility

1.02 ± 0.73 0.58 ± 0.39 2.838 0.010 *

−42.58

1.27

Tension or anxiety

0.90 ± 0.64 0.40 ± 0.44 3.185 0.005 **

−55.56

1.42

Depression or dejection

0.72 ± 0.64 0.33 ± 0.35 2.823

0.011 *

−54.39

1.26

Vigor

2.39 ± 0.62 2.51 ± 0.92 −0.754 0.459

5.24

0.34

Emotional Affect (PANAS)

Negative

Positive

1.65 ± 0.58 1.27 ± 0.37 2.905 0.009 **

−23.31

1.30

2.94 ± 0.61 3.14 ± 0.93 −1.099 0.285

6.8

0.49

Restorativeness (ROS)

4.30 ± 0.99 5.63 ± 1.02 −5.225 0.000 ***

30.81

2.34

Vitality (SVS)

4.40 ± 10 5.42 ± 1.03 −3.759 0.001 **

22.97

1.68

Note: POMS: Profile of Mood States; PANAS: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; ROS: Restorative Outcomes

Scale; SVS: Subjective Vitality Scale; ES: Effect size; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; n = 21.

Table 5. Effects of the forest recreation program on physiological stress indices.

Physiological Indices

Pre-Test

Post-Test

t

Mean ± SD Mean ± SD

p

Rate of

Change (%)

ES

Pulse rate (bpm)

86.05 ± 9.50 81.19 ± 9.63 3.581 0.002 **

−5.65

1.60

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 135.1 ± 11.39 127.33 ± 9.47 3.366 0.003 **

−5.75

1.51

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 83.62 ± 8.56 80.38 ± 9.67 1.400 0.177

−3.87

0.63

MAP (mmHg)

100.78 ± 7.85 96.03 ± 9.00 2.537 0.020 *

−4.71

1.13

Note: MAP: Mean arterial pressure; ES: Effect size; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; n = 21.

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychological Effects

This study confirmed that a short program of forest recreation has a positive influence on the

psychological indices of young learning and working adults. Negative emotions (confusion, anger

or hostility, tension or anxiety, depression or dejection) of the participants were alleviated after this

program, consistent with the results of previous studies [16,25,32]. The emotional state of vigor,

however, did not increase significantly after the recreation program. The negative aspect of emotional

affect, based on the PANAS, diminished after the recreation program, which had also been observed

earlier [16], but was not always confirmed [25]. Positive emotional affect did not increase significantly

post-test, which has not been confirmed by previous studies. Both aspects of PANAS have also been

used as good indicators of the psychological response of participants in measuring the effect of the

thinning in the forest [33]. The restoration and vitality reported by participants increased after the

program, as has been observed in other forest therapy research [34]. These findings indicate that, in

comparison to a short stay in the forest [16,25], longer stays within the elaborated forest recreation

program also have a significant positive psychological effect on participants.

The observed positive influence of a forest recreation program on psychological indices suggests

that this kind of intervention might be used in a therapeutic process. Forest recreation is a remedy for

problems such as increased stress levels in the population and decreased levels of mental health [35]

and, as shown in our study, it also works in East-Central Europe. Further research concerning mental

health (e.g., with patients in mental hospitals) may also help establish if forest recreation programs are

effective for the treatment of the mentally ill, which was not tested in this study.

Forests 2019, 10, 34

9 of 13

The natural reserve Redykajny is a good place for the citizens of Olsztyn to be mentally refreshed,

as a five-hour visit to this place had a significant positive effect on many psychological indices.

In the future, the possibility of building special infrastructure, which could be designed for forest

recreation, should be considered at the local governance level. In addition, a mental hospital is

located in the city of Olsztyn, and its buildings are near the suburban forest of Olsztyn, which affords

the possibility of using forest therapy roads for the treatment of patients. The observed positive

effects on the psychological indices observed in this study will be a good argument in stimulating

the establishment of infrastructure for therapeutic purposes and the development of strategies for

therapeutic-friendly cities.

4.2. Physiological Effects

4.2.1. Pulse Rate

A lowered pulse rate has frequently been observed in previous studies in the field of forest

recreation [6,36–39]. In this study, the pulse rate of participants was also lower after the forest

recreation program, indicating that this form of activity may be useful in alleviating the negative

effects of leading a highly stressful lifestyle [40]. Stressful work can increase the pulse rate level, which

may have negative implications for human health and well-being [41]. Even a short forest recreation

program, such as the one proposed in the present study, might be a useful tool in lowering the pulse

rates of subjects, which is especially easy in areas located near cities, as is the case with Redykajny.

The causes of the relaxing effects on pulse rate induced by forest recreation have yet to be identified:

However, several theories may be useful in explaining this effect. One is the “psycho-evolutionary

theory” [42,43], which states that humans have lived for a very long time in the natural environment,

and during this time some adaptations to unthreatening environmental conditions evolved, which may

be observed as a relaxing response to this environment. Another theory, formulated by Kaplan [44],

suggests that the forest environment has acquired some special requirements that are essential for

restoration, and one of them is to be an idyllic place for “being away”, which allows resting one’s

directed attention. In contrast, a theory proposed by Miyazaki et al. [45] suggests that humankind has

spent more than 99.99% of its evolutionary history living in untransformed, natural environments,

and thus their physiological processes function best in the forest, which could be observed as, for

example, a lowering effect on their pulse rate. These three theories also prove useful in explaining the

positive response of blood pressure.

4.2.2. Blood Pressure

As demonstrated in previous studies [5–7,10,24,37], our findings confirmed that a short forest

recreation program influences participants’ blood pressures. SBP decreased significantly after the

intervention, whereas DBP did not change after the program. Such tendencies have also been observed

by other authors [10]. MAP, defined as the average pressure in a person’s arteries during one cardiac

cycle, is likely a better indicator of perfusion to vital organs than SBP [46]. Thus, the significant

decrease in MAP after the forest recreation program indicates that this activity might be useful in

the prevention of many health issues, such as cardiac events. This is important for public health,

because cardiac events are one of the most important causes of death worldwide [47], and doing any

activity that can lower indices positively linked with cardiac events could be extremely important

for the health of each individual. The lowering of SBP indicates the influence of the forest recreation

intervention on autonomic nerve system activity [5,48], and thus it may be concluded that the tested

intervention did have an influence on this system. Higher SBP is linked with cardiovascular disease

and mortality, making every method that effectively lowers SBP valuable to overall human health [49].

Future experiments should focus on searching for areas that are best predisposed to forest recreation

purposes, with the highest potential to decrease the blood pressures of participants.

Forests 2019, 10, 34

10 of 13

Investigations addressing the effects of staying in the forest for five hours are not sparse, as two

other forest recreation programs involving approximately five-hour stays in the forest conducted in

Japan demonstrated similar effects on blood pressure reduction [6,50]. Forest recreation may prove

useful in preventing the progression of hypertension [50]. Physiological stress was reduced in the

current study in a manner similar to that reported by other short-staying studies dealing with forest

recreation. In other words, participants were physiologically relaxed, but the superiority or inferiority

of programs (differing lengths of interventions) should be examined in future studies.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we estimated the effects of a short forest recreation program on physiological

and psychological relaxation in young adults. Measurements were performed on the day before the

intervention and directly after the intervention. The results showed that participants’ levels of negative

mood (confusion, anger or hostility, tension or anxiety, depression or dejection) and negative affect

significantly decreased after the program, whereas components of their positive affect—restoration

and vitality—increased. Physiological parameters such as pulse rate, systolic blood pressure, and mean

arterial pressure lowered after the program. These findings indicate that short forest recreation

programs may positively influence the psychological and physiological characteristics of participants,

which provides evidence for the hypothesis that forest therapy in East-Central Europe could be

successful. Our short forest recreation program was conducted with success at the nature reserve

Redykajny, confirming its usability for this type of recreation.

6. Experimental Limitations

In this study, a pre-test–post-test design was applied to one group. This design is frequently used

to assess the effectuality of forest recreation programs [6,8–10]. The current study did not have a control

group, however, which might violate its internal validity. Furthermore, in forest recreation research,

a randomized, controlled trial should be used to reduce bias. Other factors possibly influencing the

results should be controlled for during this kind of study. The effectuality of the regular use of this

kind of intervention and the effectuality of this potential therapy on the overall quality of life of

participants should be tested in future studies. Although many kinds of forest therapy programs have

been developed, which of them is the most effective in improving respondents’ bodies and minds

remains unknown, and should also be addressed in future studies. Unfortunately, there is a lack of

research that has investigated the lasting effects of this intervention. Therefore, such research should

be carried out in the future to check whether the effects of forest recreation can have some prolonged

effects on study participants.

Sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous system activity and stress hormone levels of participants,

which are usually estimated in this kind of research [10,48], were not assessed this time. Only non-costly,

quick-to-collect parameters were measured before and after the program, including physiological

ones (pulse and blood pressure) and psychological ones (responses to four selected, previously-tested

research questionnaires [16]). Using measures that were not time-consuming ensured accomplishing

the aims of this research study in a relatively short time and without the potential bias caused by

measuring at different times of the day.

Author Contributions: E.B. conceived and designed the experiment, conducted data analysis, and prepared the

first version of the manuscript. L.B., S.K.-S and A.Ł. consulted on experimental design, as well as reviewing and

editing the manuscript. N.T. contributed to publication by reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Acknowledgments: We thank Filip Ordon for technical support and sharing photos. We would also like to thank

the Faculty of Forestry at the University of Life Sciences in Poznan´ and the Chair of Department of Forestry

and Forest Ecology at the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn for organizing financial support for the

manuscript’s publication.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Forests 2019, 10, 34

11 of 13

References

1. Douglas, R.W. Forest Recreation, 3rd ed.; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; p. 336. ISBN 9781483148267.

2. Morita, E.; Fukuda, S.; Nagano, J.; Hamajima, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwai, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Ohira, H.; Shirakawa, T.

Psychological effects of forest environments on healthy adults: Shinrin-yoku (forest-air bathing, walking) as a

possible method of stress reduction. Public Health 2007, 121, 54–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

3. Karjalainen, E.; Sarjala, T.; Raitio, H. Promoting human health through forests: Overview and major

challenges. Environ. Health Prev. 2010, 15, 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. Kondo, M.C.; Jacoby, S.F.; South, E.C. Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time

stress response to outdoor environments. Health Place 2018, 51, 136–150. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

5. Lee, J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Takayama, N.; Park, B.J.; Li, Q.; Song, C.; Komatsu, M.; Ikei, H.; Tyrväinen, L.;

Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Influence of forest therapy on cardiovascular relaxation in young adults. Evid.-Based

Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 834360. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

6. Ochiai, H.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; Miyazaki, Y.

Physiological and psychological effects of a forest therapy program on middle-aged females. Int. J. Environ.

Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 15222–15232. [CrossRef]

7. Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Morikawa, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of forest

recreation in a young conifer forest in Hinokage Town, Japan. Silva Fennica 2009, 43, 291–301. [CrossRef]

8. Zhou, C.; Yan, L.; Yu, L.; Wei, H.; Guan, H.; Shang, C.; Chen, F.; Bao, J. Effect of Short-term Forest

Bathing in Urban Parks on Perceived Anxiety of Young-adults: A Pilot Study in Guiyang, Southwest

China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 1–12. [CrossRef]

9. Chen, H.-T.; Yu, C.-P.; Lee, H.-Y. The Effects of Forest Bathing on Stress Recovery: Evidence from

Middle-Aged Females of Taiwan. Forests 2018, 9, 403. [CrossRef]

10. Takayama, N.; Saito, K.; Fujiwara, A.; Tsutsui, S. Influence of Five-day Suburban Forest Stay on Stress Coping,

Resilience, and Mood States. J. Environ. Inf. Sci. 2018, 2017, 49–57.

11. Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Li, Y.J.;

Wakayama, Y.; et al. Visiting a forest, but not a city, increases human natural killer activity and expression of

anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2008, 21, 117–127. [CrossRef]

12. Li, Q.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Hirata, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Wakayama, Y.;

Kawada, T.; et al. A day trip to a forest park increases human natural killer activity and the expression of

anti-cancer proteins in male subjects. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2010, 24, 157–165. [PubMed]

13. Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; Li, Y.J.;

Wakayama, Y.; et al. A forest bathing trip increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer

proteins in female subjects. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2008, 22, 45–55. [PubMed]

14. Li, Q. Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 9–17.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

15. Li, Q.; Otsuka, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Wakayama, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Li, Y.; Hirata, K.;

Shimizu, T.; et al. Acute effects of walking in forest environments on cardiovascular and metabolic

parameters. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 2845–2853. [CrossRef]

16. Bielinis, E.; Takayama, N.; Boiko, S.; Omelan, A.; Bielinis, L. The effect of winter forest bathing on

psychological relaxation of young Polish adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 276–283. [CrossRef]

17. Ciesielski, M.; Steren´ czak, K. What do we expect from forests? The European view of public demands.

J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 209, 139–151. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

18. Takayama, N.; Saito, H.; Fujiwara, A.; Horiuchi, M. The effect of slight thinning of managed coniferous forest

on landscape appreciation and psychological restoration. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2017, 4, 17. [CrossRef]

19. Murphy, E.; King, E.A. Testing the accuracy of smartphones and sound level meter applications for measuring

environmental noise. Appl. Acoust. 2016, 106, 16–22. [CrossRef]

20. Gutierrez-Martinez, J.M.; Castillo-Martinez, A.; Medina-Merodio, J.A.; Aguado-Delgado, J.; Martinez-Herraiz, J.J.

Smartphones as a Light Measurement Tool: Case of Study. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 616. [CrossRef]

21. Pickering, T.G.; Hall, J.E.; Appel, L.J.; Falkner, B.E.; Graves, J.; Hill, M.N.; Roccella, E.J. Recommendations for

blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in

humans: A statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the

American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 2005, 111, 697–716.

Forests 2019, 10, 34

12 of 13

22. Dudek, B.; Koniarek, J. The adaptation of Profile of Mood States (POMS) by D.M. McNair M. Lorr L.F.

Droppelman. Przegla˛d Psychologiczny 1987, 30, 753–762. (In Polish)

23. McNair, D.M.; Maurice, L. An analysis of mood in neurotics. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1964, 69, 620–627.

[CrossRef]

24. Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Ohira, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of forest bathing on physiological

and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health 2011, 125, 93–100. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

25. Takayama, N.; Korpela, K.; Lee, J.; Morikawa, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.J.; Li, Q.; Tyrväinen, L.; Miyazaki, Y.;

Kagawa, T. Emotional, restorative and vitalizing effects of forest and urban environments at four sites in

Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7207–7230. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

26. Crawford, J.R.; Henry, J.D. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity,

measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004,

43, 245–265. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

27. Brzozowski, P. Internal structure stability of positive and negative concepts. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 22,

91–106.

28. Korpela, K.M.; Ylén, M.; Tyrväinen, L.; Silvennoinen, H. Determinants of restorative experiences in everyday

favorite places. Health Place 2008, 14, 636–652. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

29. Korpela, K.M.; Ylén, M.; Tyrväinen, L.; Silvennoinen, H. Favorite green, waterside and urban environments:

Restorative experiences and perceived health in Finland. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 200–209. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

30. Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C. On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of

well-being. J. Pers. 1996, 5, 529–565. [CrossRef]

31. Horiuchi, M.; Fadel, P.J.; Ogoh, S. Differential effect of sympathetic activation on tissue oxygenation in

gastrocnemius and soleus muscles during exercise in humans. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 348–358. [CrossRef]

32. Lee, I.; Choi, H.; Bang, K.S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Lee, B. Effects of forest therapy on depressive symptoms

among adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 321. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

33. Takayama, N.; Fujiwara, A.; Saito, H.; Horiuchi, M. Management Effectiveness of a Secondary Coniferous

Forest for Landscape Appreciation and Psychological Restoration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14,

800. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

34. Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T. The influence of urban green

environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 1–9. [CrossRef]

35. Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy: A state-of-the-art

review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

36. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Individual differences in the physiological

effects of forest therapy based on Type A and Type B behavior patterns. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2013, 32, 14.

[CrossRef]

37. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of nature therapy: A review of the research in Japan.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 781. [CrossRef]

38. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Elucidation of a physiological adjustment effect in a forest environment:

A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 4247–4255. [CrossRef]

39. Li, Q.; Kobayashi, M.; Kumeda, S.; Ochiai, T.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Imai, M.; Wang, Z.; Otsuka, T.; Kawada, T.

Effects of forest bathing on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters in middle-aged males. Evid.-Based

Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 2587381. [CrossRef]

40. Van der Zwan, J.E.; de Vente, W.; Huizink, A.C.; Bögels, S.M.; de Bruin, E.I. Physical activity, mindfulness

meditation, or heart rate variability biofeedback for stress reduction: A randomized controlled trial.

Appl. Psychophys. Biofeedback 2015, 40, 257–268. [CrossRef]

41. Cassel, J. Physical illness in response to stress. In Social Stress; Levine, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY,

USA, 2017; pp. 189–209.

42. Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to

natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [CrossRef]

43. Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Human Behavior and Environment;

Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125.

Forests 2019, 10, 34

13 of 13

44. Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15,

169–182. [CrossRef]

45. Miyazaki, Y.; Park, B.J.; Lee, J. Nature therapy. In Designing Our Future: Local Perspectives on Bioproduction,

Ecosystems and Humanity; Osaki, M., Braimoh, A., Nakagami, K., Eds.; United Nations University Press:

New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 407–412.

46. Roman, M.J.; Devereux, R.B.; Kizer, J.R.; Lee, E.T.; Galloway, J.M.; Ali, T.; Umans, J.G.; Howard, B.V. Central

pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: The Strong

Heart Study. Hypertension 2007, 50, 197–203. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

47. Mathers, C.; Stevens, G.; Hogan, D.; Mahanani, W.R.; Ho, J. Global and Regional Causes of Death: Patterns

and Trends, 2000–15. In Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition: Volume 9. Improving Health and Reducing

Poverty; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 69–104.

48. Yu, C.P.; Lin, C.M.; Tsai, M.J.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chen, C.Y. Effects of short forest bathing program on autonomic

nervous system activity and mood states in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public

Health 2017, 14, 897. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

49. Bundy, J.D.; Li, C.; Stuchlik, P.; Bu, X.; Kelly, T.N.; Mills, K.T.; He, H.; Chen, J.; Whelton, P.K.; He, J. Systolic

blood pressure reduction and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: A systematic review and network

meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 775–781. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

50. Ochiai, H.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Takamatsu, A.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.;

Imai, M.; et al. Physiological and psychological effects of forest therapy on middle-aged males with

high-normal blood pressure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2532–2542. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access

article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution

(CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).