Solace from Space

Jennifer Marrie Burch

Solace from Space

Jennifer Marrie Burch

esis submitted to the faculty of

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

in partial ful llment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Landscape Architecture

in

Landscape Architecture

Paul Kelsch

Nathan Heavers

Marcia Feuerstein

April 13, 2021

Alexandria, Virginia

Keywords: Landscape Architecture, Mental Health, Urban Planning

© Jennifer Marrie Burch, 2021

Solace from Space

Jennifer Marrie Burch

ABSTRACT

Shinrin-yoku or forest bathing is the Japanese art of using the forest to relax. e

process takes about two hours to absorb the full bene ts of the forest. is does not provide

for an easy way to decompress if you are living or working in an urban environment. e

expansion of urbanism and decrease of green space across the country only furthers the

inaccessibility someone might face if they seek nature as their destination to de-stress.

ere needs to be a more accessible way to alleviate the harmful e ects of stress in an urban

atmosphere. e health bene ts from nature are numerous. is thesis focuses on the ways

landscape can quiet the mind and aid in calming the psychological stressors of a person

living in an urban environment. e use of expanse, beauty, and phytoncides combine

together to create the zones of this soothing landscape park. e importance of nding a

way to create a safe, healing environment is critical to the development of this site. Multiple

design ideologies are implemented to create a space that will aid in reducing strain on

the brain’s cognitive load capacity. is thesis shapes a park that provides a calming and

soothing escape for any person who seeks twenty minutes to relax and decompress before

returning to their work day. e Carlyle Solace Park is an example of how a therapeutic

space can be created in an urban environment.

Solace from Space

Jennifer Marrie Burch

GENERAL AUDIENCE ABSTRACT

Stress is debilitating. Mental illnesses are o en incapacitating. ‘ e brain has a mind of

its own’ is in fact no joke. Managing a person’s mental health in an urban environment is not easy.

Smog, car horns, tra c, o ce chatter, the smell of dumpsters or cigarettes as you walk down

the street. None of this will help someone when they are going through a depressive episode, a

panic or anxiety, or have exceeded the amount of stress their body can handle. ere has to be

a way to create a space that calms the mind and allows for reconnecting with your senses in the

environment. e Japanese call it shinrin-yoku or forest bathing. Forests are used to alleviate the

pressures of day to day stress and other mental or psychological ailments. To truly bene t from

shinrin-yoku, one must spend two hours amongst the trees in the forest. is does not provide

for an easy way to decompress if you are living or working in an urban environment. is thesis

explores the bene ts of three landscape types to create a park that can provide solace to the person

who is struggling with stress or a mental illness. e brain can be uncontrollable. It is important

to nd a way to relieve the pressures placed on it. Nature is healing. Cities need to maximize

therapeutic e ects of nature in their green spaces. e Carlyle Solace Park, designed in this thesis,

is an example of how a therapeutic space can be created in an urban environment.

DEDICATION

is thesis is dedicated to those su ering om mental health ailments.

I hope this helps inspire you to nd a space that can ease your pain and help you nd solace.

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank my friends and family who assisted me on my thesis journey for

their love, unyielding support, and encouragement, especially Bill and Patti Burch,

Allison, Michael, and Zoe Harrigan, Pamela Sanchez, Becky Anzelone, and Chris Hampel.

My thesis co-hort who I would not have gotten this far without: Lynda Ramirez-Blust,

Michelle Mitchell, Ashley Coates, Rana Rahimi. My thesis committee for their feedback

and guidance: Paul Kelsch, Nate Heavers, and Marcia Feuerstein. ank you all so much

for helping me get to the nish line.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

III

GENERAL AUDIENCE ABSTRACT

IV

D E D I C AT I O N

V

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

VI

INTRODUCTION

1

20 MINUTES

5

SOFT FASCINATION

8

SITE SELECTION

9

URBAN FOREST

15

CARLYLE SOLACE PARK

19

MODEL

25

S AVA N N A H

27

ATTENTION RESTORATION THEORY

29

MEADOW

35

THE OUDOLF METHOD

37

THE RAINIER METHOD

39

S WA L E

45

FOREST

49

BIO-ENERGY & NEGATIVE IONS

51

PH Y TONCI DE S

55

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

59

REFERENCES

61

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

figure 1 - photo from carlyle neighborhood

figure 2 - photo of grass textures

figure 3 - inspiration photo collage

figure 4 - alexandria african american heritage park (aaahp)

figure 5 - aaahp, hooff’s run view

figure 6 - sketch of walk at hooff’s run

figure 7 - photos from lake walk

figure 8 - sketch from lake walk

figure 9 - photos from various walks - falls church, va

figure 10 - eisenhower avenue, south - sketch

figure 11 - photo from john carlyle street looking south

figure 12 - existing site collage

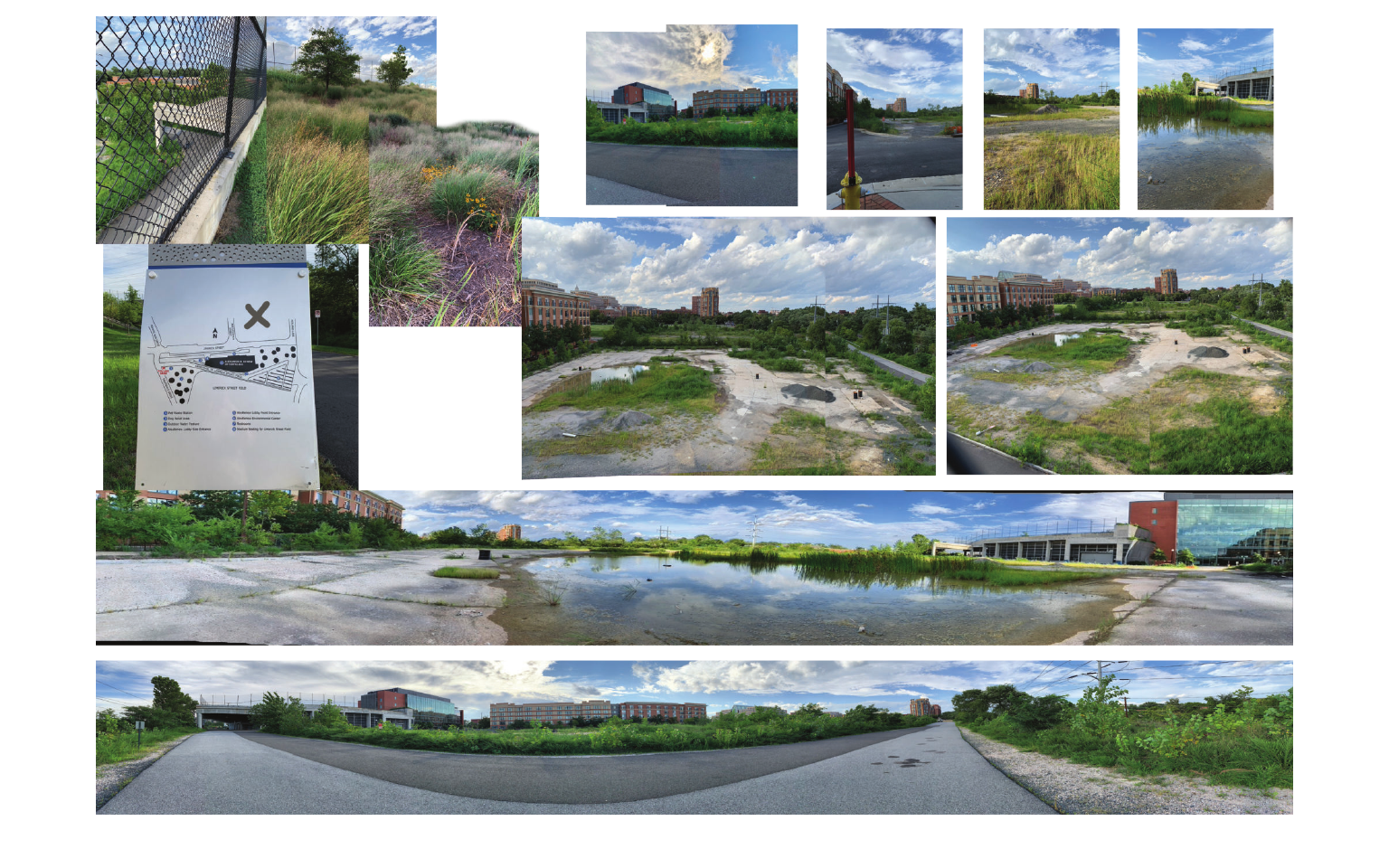

figure 13 - site/empty lot collage

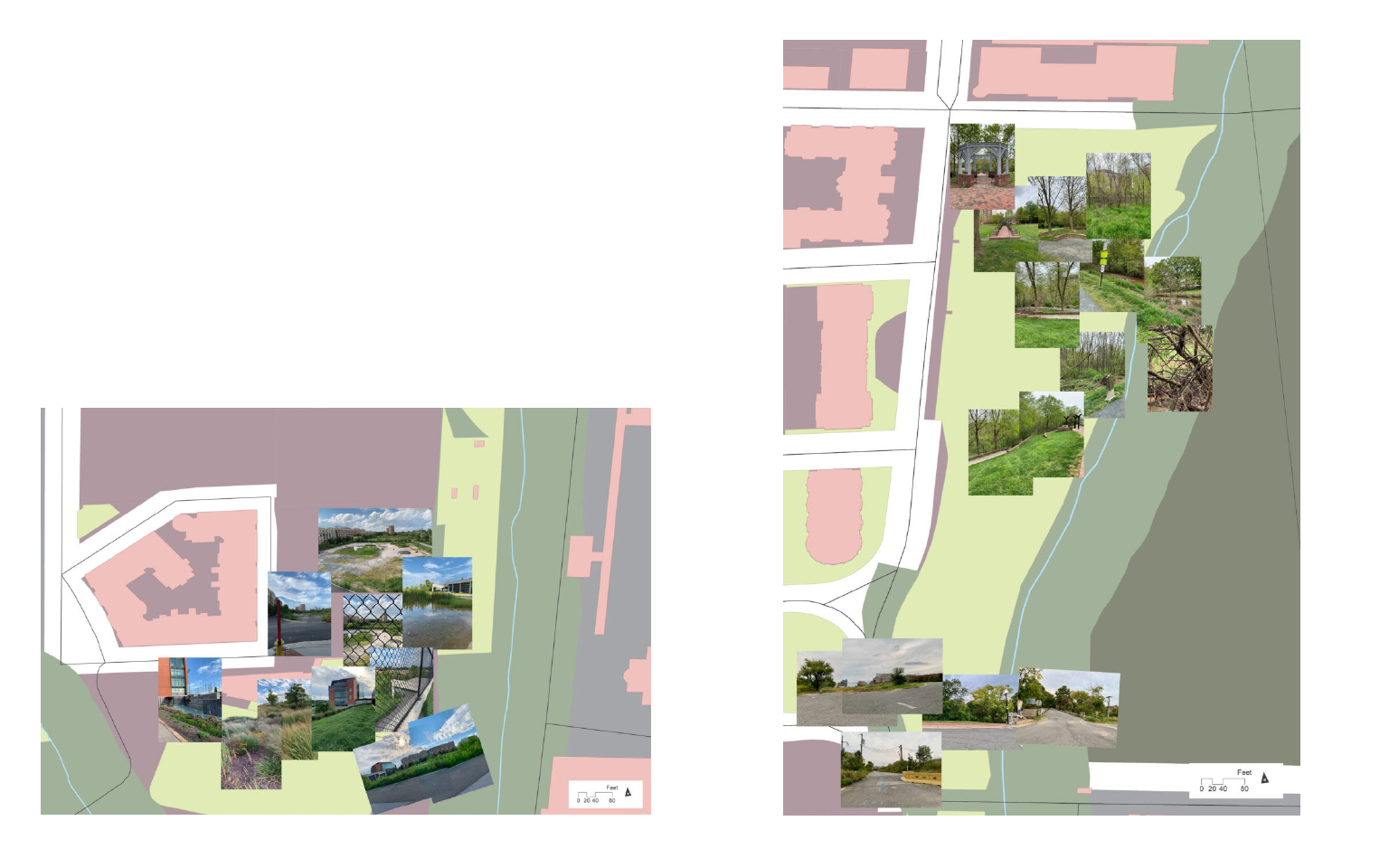

figure 14 - aaahp & empty lot site collage

figure 15 - urban forest site collage

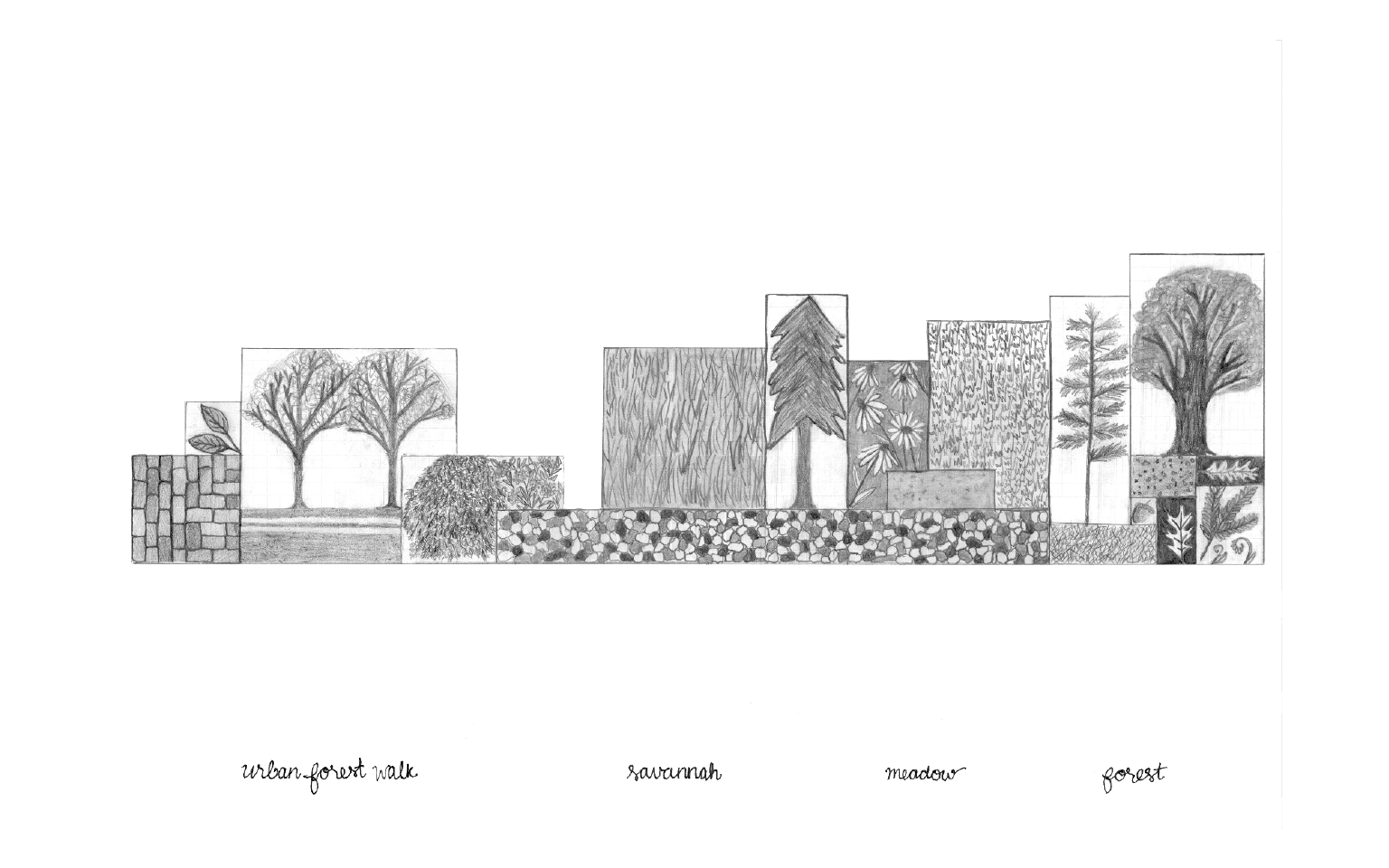

figure 16 - site textures sketch

figure 17 - carlyle neighborhood, alexandria, va - aerial

figure 18 - carlyle solace park - original layout

figure 19 - carlyle solace park - final layout

figure 20 - carlyle solace park - cut/fill diagram

figure 21 - carlyle solace park - grading plan

figure 22 - carlyle solace park site - plan with section lines

figure 23 - site model

figure 24 - savannah section

figure 25 - savannah perspective

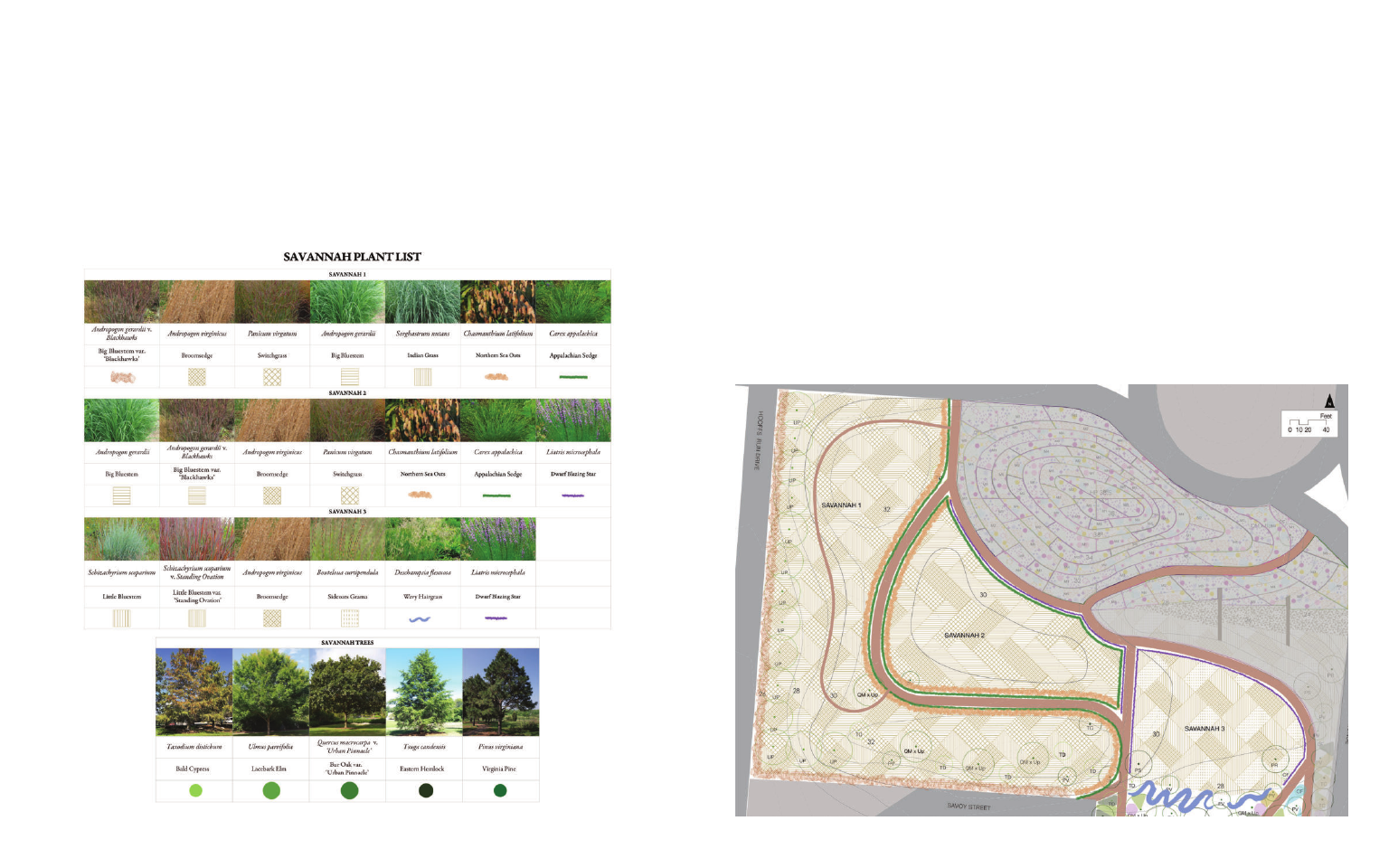

figure 26 - savannah plant list

figure 27 - savannah planting plan

figure 28 - plant texture collage

figure 29 - meadow section

figure 30 - textural details - oudolf’s planting at hummelo

viii

2

figure 31 - lurie garden - chicago, il - designed by oudolf

38

2

figure 32 - thomas rainier’s home garden - arlington, va

40

4

figure 33 - bio-retention planting - lancaster, pa - designed by phyto studio

40

5

figure 34 - meadow plan - ‘quilt’ view

41

6

figure 35 - meadow planting plan - matrix view

41

6

figure 36 - meadow planting plan

41

7

figure 37 - meadow plant list

42

7

figure 38 - meadow elevation

44

8

figure 40 - swale section

46

9

figure 39 - example of river rocks

46

10

figure 41 - swale planting plan

47

12

figure 42 - swale plant list

48

13

figure 43 - forest perspective

50

14

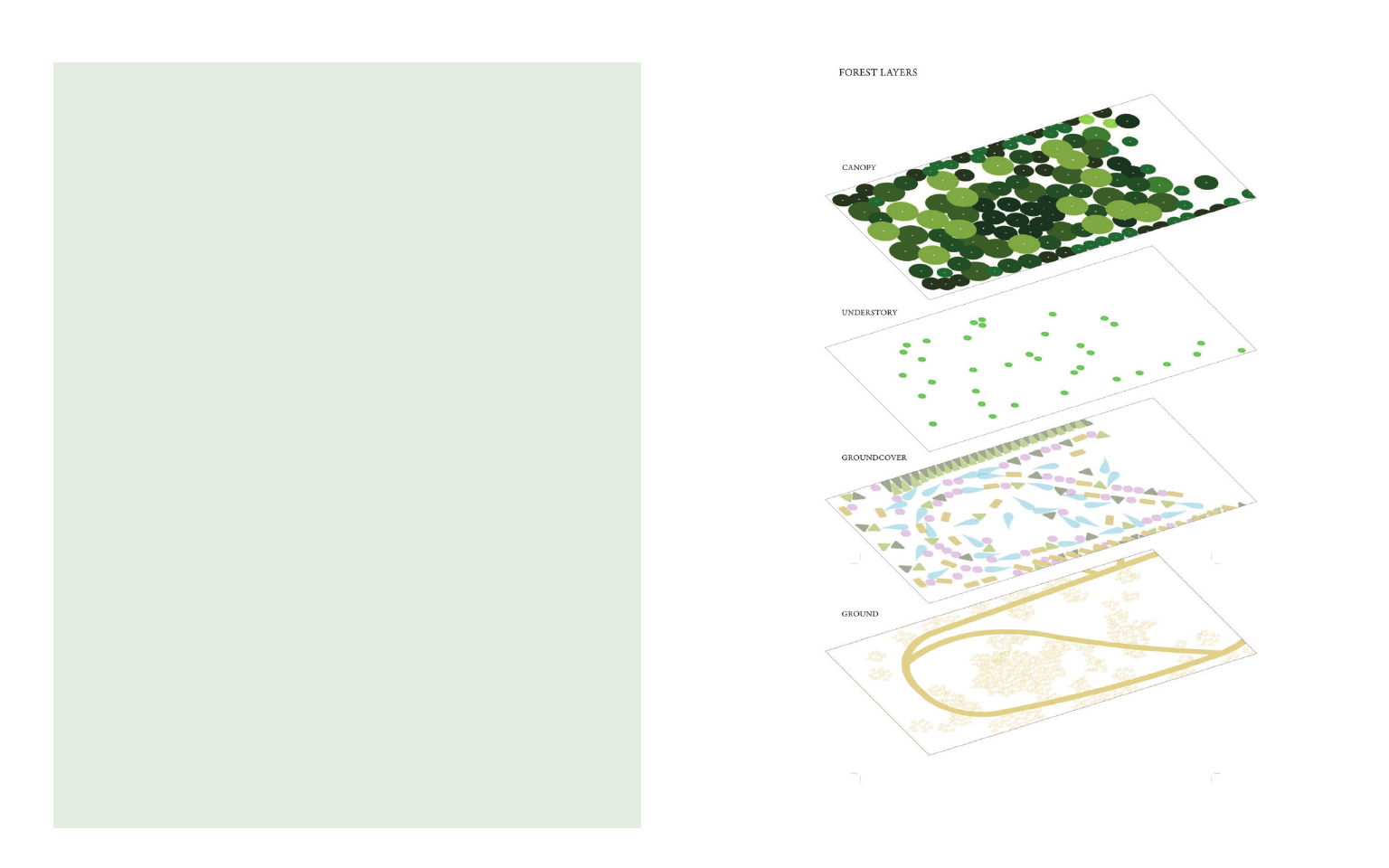

figure 44 - forest layers axonometric

52

16

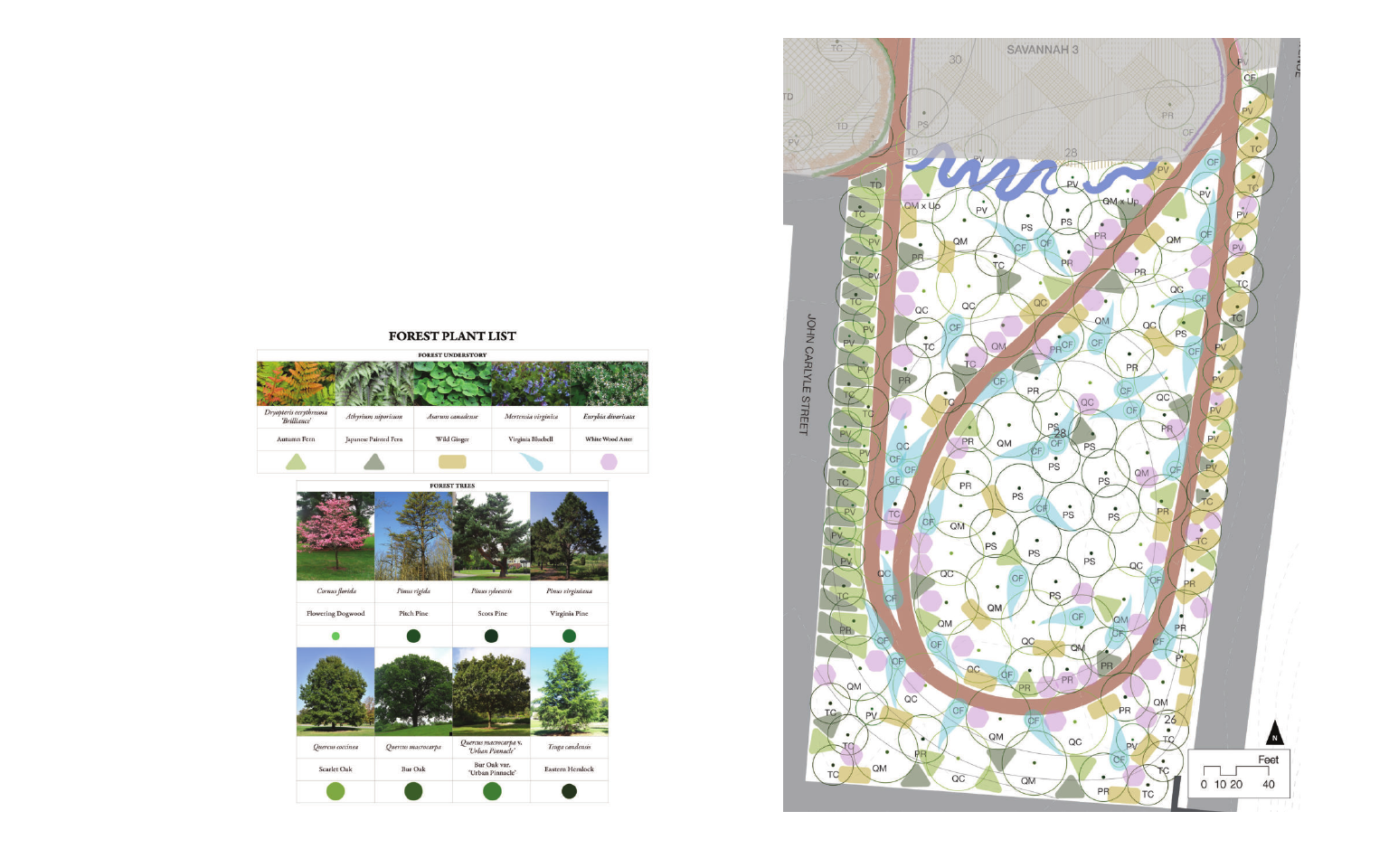

figure 45 - forest plant list

53

17

figure 46 - forest planting plan

54

20

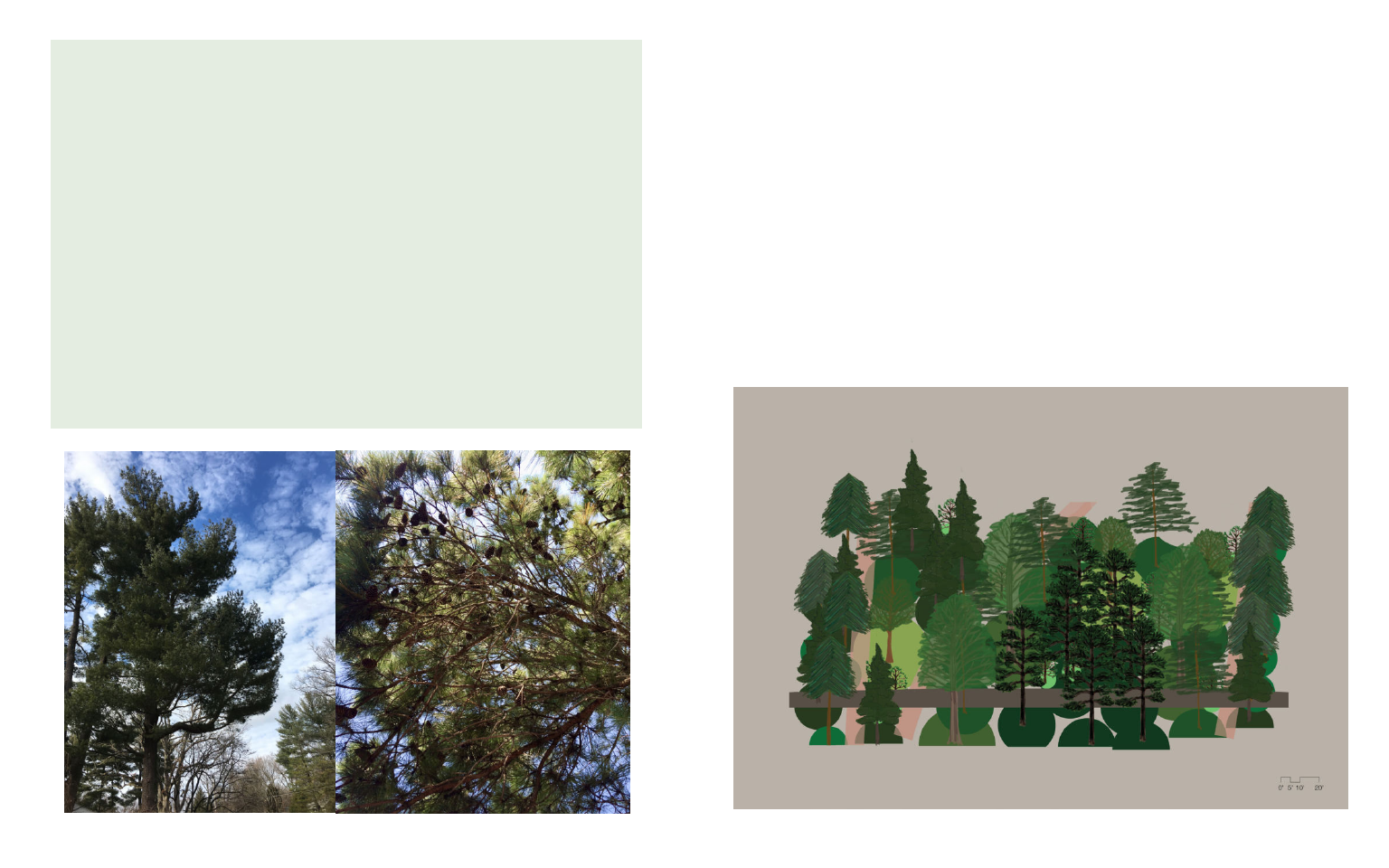

figure 47 - photo of conifers

55

21

figure 48 - forest center sketch

56

21

figure 49 - final collage

57

22

figure 50 - photo of pine needles

60

23

figure 51 - photo of forest

62

24

25

28

30

31

32

33

36

38

ix

x

INTRODUCTION

Stress and forest bathing di erent. Unfortunately, in America anxiety, and depression was the

- together became the impetus for mental health is o en not covered by starting point of my search for

this thesis. I have su ered from insurance companies, or if it is, the alternative mental health relief. I

anxiety and depression most of my paperwork alone is overwhelming. found Dr. Qing Li’s book, Forest

life. Mental health diagnoses usually Counselors and therapists are Bathing - How Trees Can Help You

lead to a roller coaster lifestyle — frequently independently owned Find Health and Happiness, lled

that is, some good days and some and costly. So, while one can with visually striking images of

bad ones. But the bad ones are pay out of pocket and wait to be lush green forests in Japan. is

harder than the typical ‘ at tire on partially reimbursed, it is not ideal. reminded me of my undergraduate

the way to work’ bad day. I entered e system or lack of a system studies in Japanese art history, and as

graduate school full time while also causes people to seek alternative a graduate student, Japanese gardens

working full time. My stress level forms of mental health care. While has become my favorite genre in

imploded, and the bad days led to organizations like Mental Health landscape architecture history. I le

anxiety attacks, massive waves of America are making strides with the bookstore with my new forest

overwhelming emotions, and many campaigns like #StoptheStigma and bathing book and started reading.

days of doubt, ultimately sent me on #B4Stage4, it is still hard for many

A er nishing Dr. Qing

this path pursuing stronger mental to seek help from a professional due Li’s book, shinrin-yoku, the Japanese

and physical health.

to cost, accessibility, availability, term for forest bathing, increased my

Mental health care is not awareness. e path to healthy fascination with Japanese culture.

a one size ts all solution. For mental health is full of obstacles. Dr. Li’s book explained the science

most, the best form of treatment

Perusing the ‘Self Help’ and research behind the healing

is a combination of talk therapy sections of bookstores, nding e ects spending time in nature has

and medication, but everyone is books on breathing, mindfulness, on the body. A two-hour forest bath

1

decreases the signs of stress on the

body signi cantly and creates huge

strides for those needing assistance

in stress management or mental

health struggles. ese two simple

ingredients (two hours and a forest)

are a prescription for a healthier

mind, but are actually harder to

nd in urban areas of the United

States, which is drastically losing

its green space. Street trees are

o en the closest a person gets to a

forest. How many cities have forests

within a 20-minute drive? ere

may be parks and green spaces, but

actual forests are dwindling. en

comes the ingredient of time. How

many people have two consecutive

hours in which they can unplug

from their life and go for a walk

in a forest? Driving out of the city

to a forest for a two hour hiatus is

not a practical component of the

workday. ere had to be a way to

harness the techniques and bene ts

of forest bathing in a shorter time

frame. Making this process more

attainable and accessible within city

limits is the opportunity to help

those su ering from mental illnesses

attain the relief o en needed on a

daily basis.

figure 1 - photo from carlyle neighborhood

figure 2 - photo of grass textures

2

figure 3 - inspiration photo collage

3

4

20 MINUTES

If forest bathing is shorter of the two time frames as the middle to be devoted time spent

impractical to someone in an urban the main constant, I estimated the in a healing landscape. Is twenty-

setting, how can this problem be amount of time someone is able to minutes be enough time to restore

resolved? How much time does devote to extracurricular activity the mind and body from stress?

someone actually have during a and still get back to work on time. If that was all the time a person

work day that would allow them to irty minutes allots for a ve had, would it even be worth it?

get away, reset, relax, take a break? A minute trip to the new destination According to a study done at the

lunch break is the only time or respite and a ve minute trip back, while University of Michigan, “for the

for most workers and the average allowing for the twenty-minutes in greatest payo , in terms of e ciently

lunch break is half an hour to an

hour long. According to Mencagli

and Nieri, “it would be much

healthier to take a break and re ect

in a beautiful natural environment

that, as has been shown, allows us to

expand our cognitive capacities even

with complex emotional states that

produce calm and serenity, promote

greater relaxation, regularize our

heartbeat, and modulate blood

pressure” (40). A park escape would

be bene cial at both the emotional

and physical level. By using the

figure 4 - alexandria african american heritage park (aaahp)

5

lowering levels of the stress hormone Heritage Park. I walked the whole the vegetation, the wildlife, and

cortisol, you should spend 20 to loop in about ten minutes (partially the infrastructure of the site were

30 minutes sitting or walking in a because I was committed to keep focused on in more detail. What

place that provides you with a sense moving and get the most accurate made this place special? What made

of nature” (Frontiers). Another judgment of distance). e second it a good space to walk? What were

study written for the International lap was slower and more immersive; is deterrents? e sensory elements

Journal of Environmental Health

Research by Yuen and Jenkins

found that the subjective well-being

of a person was higher a er time

spent in a park. Yuen and Jenkins

suggest “design of the park space

should attract visitors to stay for at

least 20 min in the park” (Yuen and

Jenkins). Additionally, Sue Stuart-

Smith writes in her book, A Well-

Gardened Mind: e Restorative

Power of Nature, “whilst changes in

heart rate and blood pressure can be

detected within minutes of exposure

figure 5 - aaahp, hooff’s run view

to natural surroundings, levels of the

stress hormone cortisol take a little

longer to reduce, typically dropping

a er twenty to thirty minutes” (75).

Twenty-minutes would be enough

time to make an impact on lowering

the stress level of a person.

e next question was how

far does 20 minutes of walking take

a person? I took a few exploratory

walks to try and determine this. e

rst journey was at Hoo ’s Run

near Alexandria’s African American

figure 6 - sketch of walk at hooff’s run

6

were there. e pathway was lower water owing on me, which was not Park when the sound of the falls

in the ravine blocking out almost bad, just subtly took away from the is heard before it is seen. e lake

all of the city noise one expects to naturalistic part of the walk since I path has more residential landscape

hear in an urban park. ere were knew where the source of the sound plantings and a larger collection of

plenty of shades of green in the was coming from. It was not the color than the path at Hoo ’s Run.

early summer. e temperature experience a person has in Prospect It was a di erent visual experience

was cooler in the shade. e water

from Hoo ’s Run was visible, but

it was stagnant and the sounds of

water running down a riverbed was

inaudible. Nature encompassed the

lower path presenting a di erent

type of quiet that sweeps over and

relaxes the mind. It was not forceful,

but a sudden realization of serenity.

is is what I wanted to create. A

safe space, a calm space, a natural

space that could allow for the mind

and body to begin to heal. I located

figure 7 - photos from lake walk

one sample park design, in a ten-

minute path, one block o of Duke

Street in Old Town, Alexandria.

e second journey to

experiment with the twenty-minute

timeline was around a man-made

lake. It was a slower trip with more

focus on plants and wildlife. e

terrain was di erent, it was asphalt

around the lake on one side and

boardwalk on the other. is man-

made lake with fountains was not

the same as the stagnant overgrown

Hoo ’s Run. It forced the sound of

figure 8 - sketch from lake walk

7

and apparent the path was in a

housing community; it did not feel

like an immersive environment.

e path around the lake was about

three quarters of a mile and at a

slower speed about twenty-minutes.

is trip gave a lot of perspective

on naturalistic design, the role of

immersion in the landscape and the

importance sound has on creating a

calming space.

Other walks were longer

than 20 minutes and on paths in the

woods. Nature was engul ng; the

plants were growing wildly and the

bright owers popping up brought

forth a beautiful collection of color

and texture. ere was something

serene about having so much to look

at that allowed the brain to rest. So

fascination now made perfect sense.

SOFT FASCINATION

A brain can only handle so much, at some point you

reach your cognitive load capacity and fall into mental fatigue.

Mental fatigue can come from stress but it can also “arise out of

handwork on a project one enjoys” (Kaplan and Kaplan, 178).

While stress and mental fatigue are similar, they are not one and

the same. However, both can be soothed through so fascination.

So fascination “is created by environments and situations with a

gentle appeal, an emotional engagement modulated by pleasurable

but not overly intense stimuli, which allow for a full regenerative

experience (Mencagli and Nieri, 59). Looking at something that

not only calms the eye but also the mind is to experience so

fascination. Its counterpart, hard fascination, is more emotional

and overpowering, it does not allow for restorative processes. So

fascination allows us to enjoy things like the waves on a beach or

a sunset. We feel calm by watching a simple scene and nothing to

divulge thought or action into it.

figure 9 - photos from various walks - falls church, virginia

8

SITE SELECTION

Where could I nd a space urbanism into perspective. It is volunteer plantings just growing up

that would allow me to amplify the full of restaurants, the US Patent around the edges. ere were tall

patterns and characteristics of the and Trademark O ce, multiple cattails and other plants which I was

natural environment? I wanted to other o ce buildings, apartment not able to identify that were easily

create a space that brought color and complexes and some open spaces. a few feet tall. is ‘pond’ had to

texture, like the experiences I had ere were three large empty lots to have been sitting on this abandoned

on my walks, while also wrapping a the south of Eisenhower Avenue that lot for a year, if not longer. It was

person in a natural security blanket were paved and covered with weeds. as if the space was calling for more

by putting them in a safe calming Spaces clearly lying in wait for some vegetation, a revitalization. is

environment.

magic to be done to beautify them. space needed my help.

e further investigations e space had a ‘pond,’ which was

e existing lots were

around the Carlyle neighborhood actually a stagnant body of rain water neglected. Fenced along the West

of Alexandria brought the area’s sitting in the middle of it lled with side near the apartments. e

figure 10 - eisenhower avenue, south - sketch

9

East side was unfenced but thick

e site in the Carlyle where people gathered making it

overgrown weeds lining the street neighborhood had the quali cations accessible and that was key to the

edge. ere were a few “Do not I was looking for. It was close to success of the space. ese empty

enter” signs scattered around. e housing, multiple business and o ce lots were exactly where my park

lots formed an upside-down ‘L’ shape spaces, plenty of restaurants — all should be.

with the longer portion parallel to the elements of urban living. It has

Hoo ’s Run. e Northern part people around who could bene t

of the site, was partially covered from the type of place I wanted to

in asphalt and was far from at. It design. It was walking distance from

looked as if a pile of dirt had just

been paved over it without taking

the time to level the ground rst.

en on the low side of this paved

mound the asphalt stopped. It

turned into a dusty gravel space with

wild grasses starting to ll in. is

transition is also where a small swale

below the tra c circle was located,

which sent water right across the

street toward a small bridge and

into Hoo ’s Run. e area directly

across from John Carlyle Street was

also overgrown. It appeared to have

once been some sort of open eld

because there was less asphalt here

and more uncut grasses and weeds.

ere was fencing along Eisenhower

Avenue across from John Carlyle

Street which made the space look

even less inviting. But standing

across the street, looking at this lot

straight on there were two things I

could see: blue sky and potential.

figure 11 - photo from john carlyle street looking south

10

figure 12 - existing site collage

11

12

figure 13 - site/empty lot collage

13

figure 14 - aaahp & empty lot site collage

14

URBAN FOREST

e forest is the base of this of the street going south toward was more cheerful than walking

entire project. It brought forth the Eisenhower Avenue that I realized down the side of the street that had

ideology of natural healing. How what I had discovered. e trees on minimal landscaping and a giant

could the landscape be used to heal this side had much larger canopies driveways for parking garage entry

the mind and body? It was again a and the sidewalk takes a pedestrian and service work.

‘forest’ that brought cohesiveness to under the street trees. ey were

e upli ing and enjoyable

selecting the three empty lots south part of the experience of walking as situation was what I was seeking

of Eisenhower Avenue. e space I opposed to the Western side where to build. Here I was in a street tree

dubbed ‘Urban Forest’ was a healthy the street trees functioned as items forest just across the street from the

grouping of street trees lining the that broke up the monotony of the empty lots I had discovered in serious

Eastern side of John Carlyle Street. block. Against the buildings, back need for remediation. is had to be

is canopy covered sidewalk was on the Eastern side, were smaller the start of my journey. If I could get

a welcoming gateway leading up to conifers and shrubs that hid the people to start their healing walk

the three lots chosen as the space to exposed brick of the buildings. e on the Eastern side of John Carlyle

create a therapeutic landscape on. two sides of John Carlyle Street are Street they would bene t from an

Both sides of John Carlyle like night and day when it comes to unintentional forest bath before

Street were analyzed multiple the vegetation. On the more barren getting to the solace park I wanted

times from the perspective of side was a parking garage while the to build. It was a prefab entrance to

the pedestrian and as a driver. opposite was town-homes. e a dream space that held the qualities

When driving it was noticeable landscaping was more inviting near I wanted to create in the rest of the

that one side of the street had the homes and it was clear in the site. e perfect gateway just four

more vegetation, but it was not experience of walking the space. tra c lanes apart.

until walking on the Eastern side Walking down a landscaped street

15

figure 15 - urban forest site collage

16

figure 16 - site textures sketch

17

18

CARLYLE SOLACE PARK

e overall goal of this site archetypes, which can be recreated from a high point of 38.5 feet to

design is to combine three landscape and replicated in other cities with 23 feet at the lowest point of the

archetypes to create a place that the hope that more natural therapy swale. e path is formed from self-

will appease a larger portion of the healing spaces can be built across the binding gravel aggregate and is just

population and e ectively create country or around the world.

over one-half mile in total length.

natural healing zones for as many as

e site allows for entry

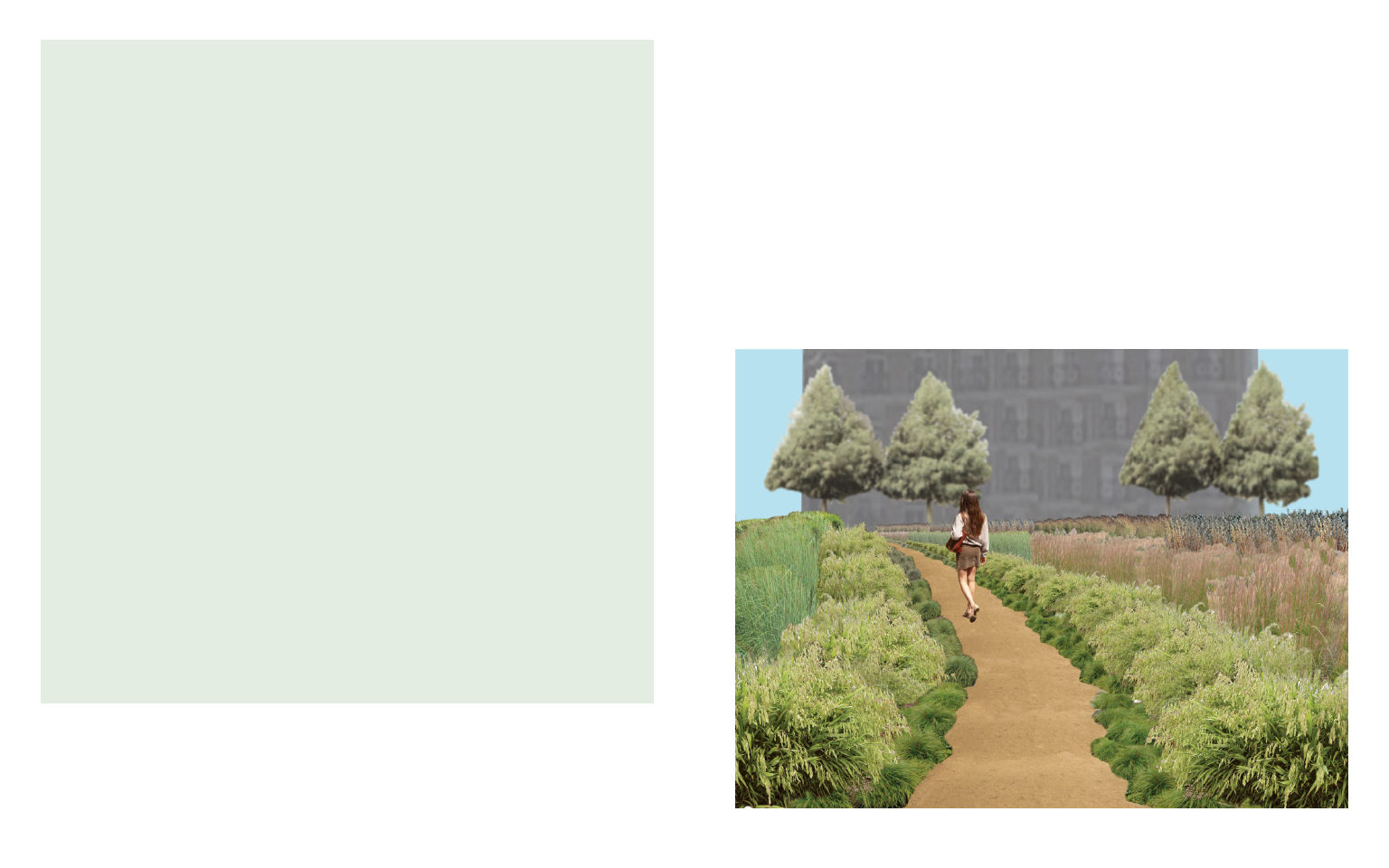

e site perspectives and

possible. ethreechosenarchetypes from three locations: the North, sections in the following images all

are the savannah, the meadow, in between the savannah and the intentionally showcase the same

and the forest. Each provide rest meadow on Eisenhower Avenue; individual as they experience the

through di erent psychological or the middle, entering from Savoy site. As the design’s intent is directed

situational contexts. e savannah Street and John Carlyle Street into toward a more personal solitary

allows for a person to feel safe in a the savannah and the forest; the experience. Here the woman

space where they can see the entire East, from Eisenhower Avenue just experiences the three archetypes in

expanse around them. e meadow north of the swale entering into the her journey to nd some solace.

relies on the role of beauty in the meadow. e path allows for various

landscape, which allows the eye ways to navigate the archetypes and

and mind to rest. e forest emits encourages a ‘choose your own

organic compounds, which are healing’ experience. As a whole

mood li ing. ese three types Carlyle Solace Park is roughly 8 ¼

allow for a space that helps more acres lled with 13 species of grasses,

than one person or that a person can 13 meadow plants, 5 herbaceous

be helped through more than one layer plants in the forest, and ten

method. ey are relatively simple tree species. e elevation changes

19

Source: Esri, Maxar, GeoEye, Earthstar Geographics, CNES/Airbus DS, USDA, USGS, AeroGRID, IGN, and the GIS User Community

Feet

0 50 100 200

figure 17 - carlyle neighborhood, alexandria, virginia - aerial

20

SAVANNAH

PEBBLE SWALE

HILLSIDE

MEADOW

FOREST

Feet

0 50 100 200

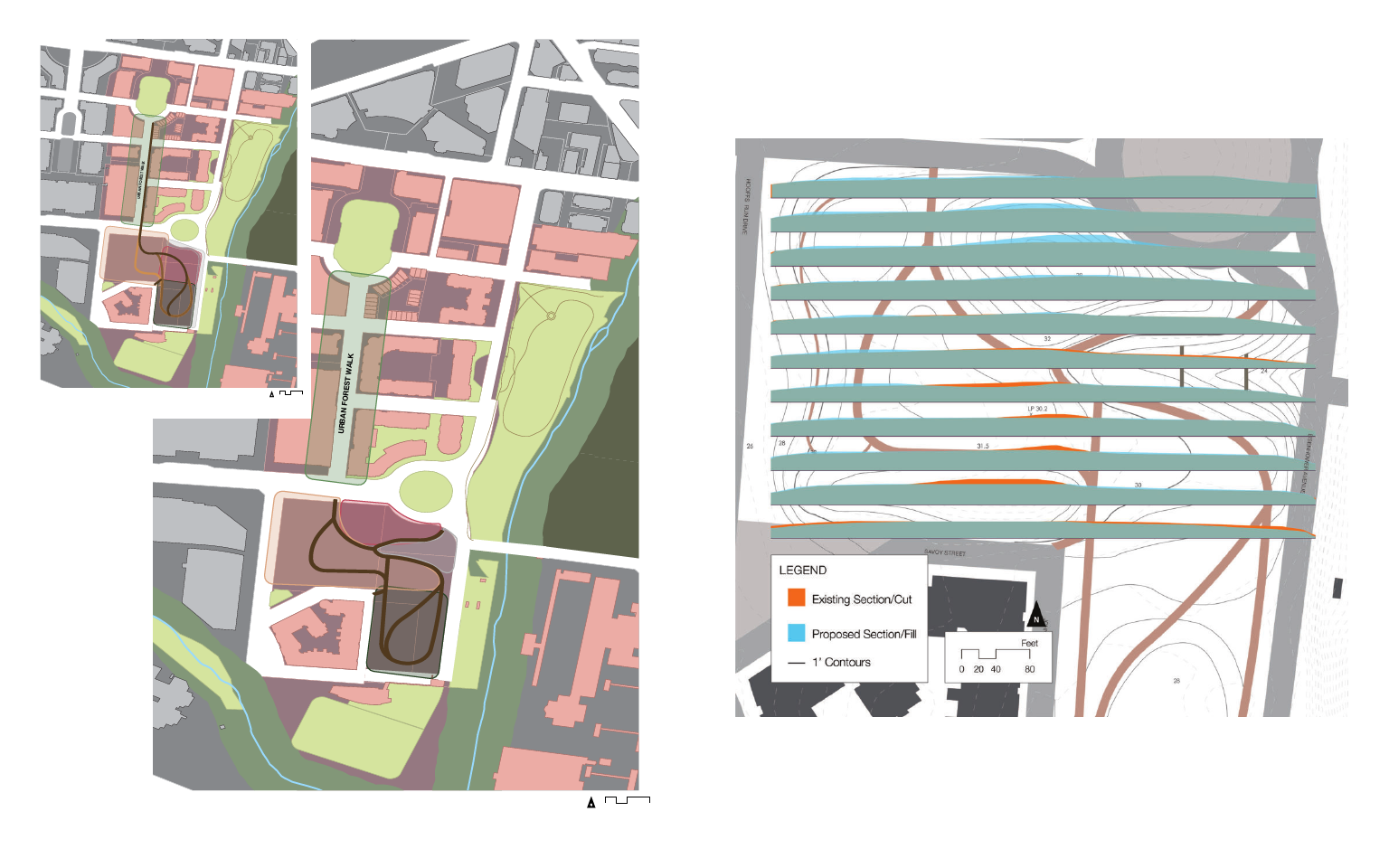

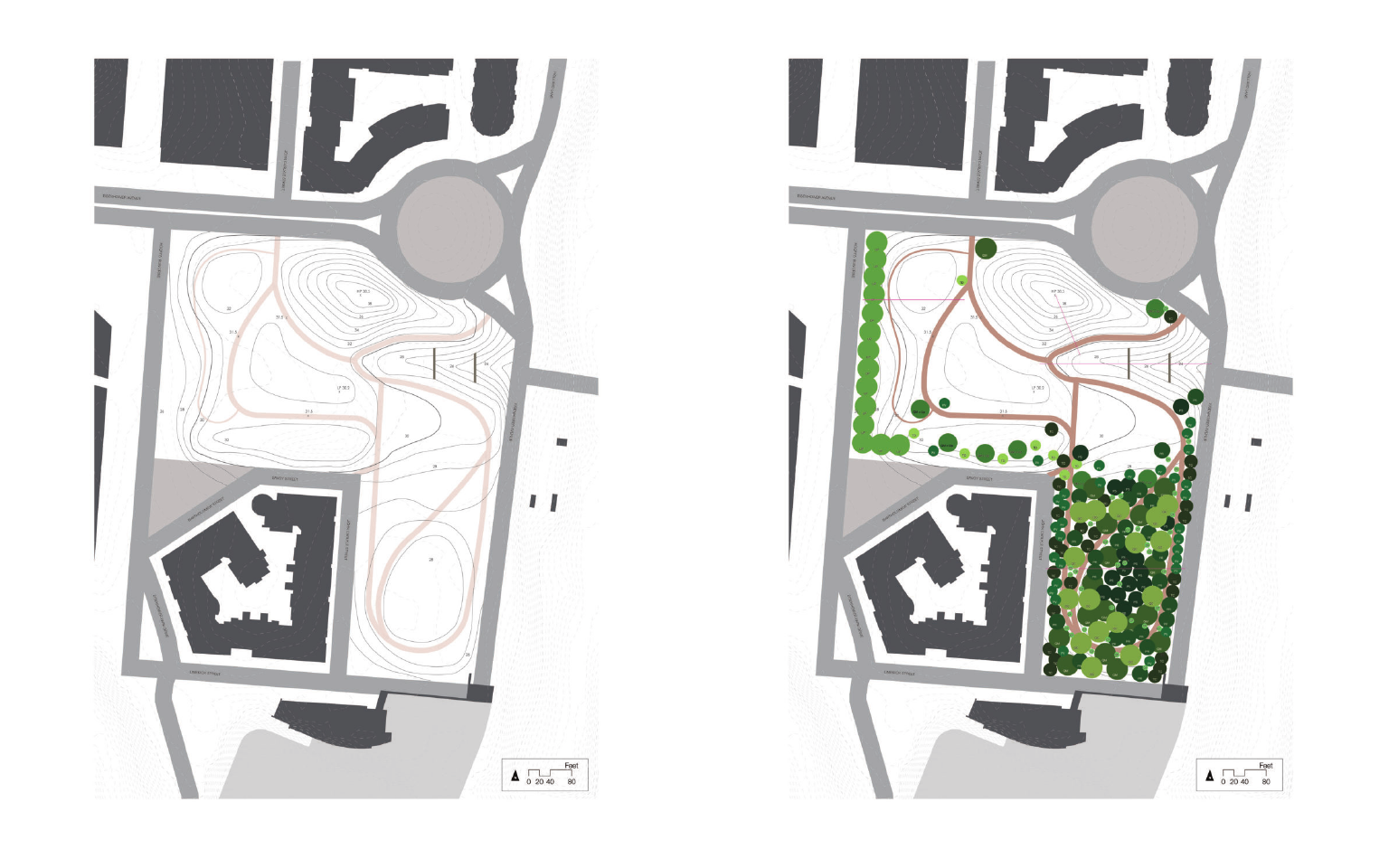

figure 18 - carlyle solace park - original layout

HILLSIDE

MEADOW

SAVANNAH

PEBBLE SWALE

FOREST

Feet

0 50 100 200

figure 19 - carlyle solace park - final layout

21

figure 20 - carlyle solace park - cut/fill diagram

22

figure 21 - carlyle solace park - grading plan

23

figure 22 - carlyle solace park site - plan with section lines

24

MODEL

Building the model was in variegated thread to showcase is area ended up being a critical

important to the understanding of the immense variety of planting transitional space where the

the design and topography of the that would be on the hill. In the savannah connects to the forest in a

site. Felt was used to cut each layer savannah, knots of multicolor naturalistic manner.

of the model. e horizontal scale is threads with long tails are used

e model was a de nite

1”=40’ with the model measuring 18 to show tall grasses. Finally, for turning point in the design of the

inches by 22 inches, which shows an the trees felt circles for protecting site. It was a very tedious project, but

area of the site 720 feet by 880 feet. furniture were color coded per the insight that was gained from its

e vertical scale is ⅛”=1’ showing species and sized to scale based on creation was well worth the e ort.

elevations from 20 feet to 35.5 feet. species’ canopy widths.

Seeing the site in three dimensions

In the nal stages of grading the site,

While the model doesn’t and creating a piece of art in the

the model was critical in deciding to represent the nal design, (the process was energizing.

raise the high point of the meadow placement of the path changed, the

hill two 38.5’ for greater impact to hill is raised, swale deepened, etc.)

this archetype. A person standing at it did provide excellent guidance

the bottom of the hill would have on areas that were being overlooked

a better view shed of the meadow in the design. For example, the

with it potentially matching their area below the swale and above the

height.

forest was without characteristics of

In the model di erent any archetype. When lling in the

types of embroidery are used to textural elements representing each

emphasize the site’s texture. e archetype on the felt model, the

meadow is made up of French knots hole in the design was highlighted.

figure 23 - site model »

25

26

S AVA N N A H

e savannah is proven to be of green space that resemble the experiences when entering from

one of the most relaxing landscape landscape of the savanna at least Eisenhower and the Carlyle area.

archetypes. e ability for a person somewhat provide the fastest e western edge of Savannah

to see all of their surroundings emits adaptive response of recovery from I, along Hoo s Run Drive, is

a feeling of safety. e research of stress” (61). e ability to see a lined with Andropogon gerardii v.

Rachel and Stephen Kaplan explains whole area and understand it even ‘Blackhawks,’ big bluestem variation

this feeling as ‘extent’ in Attention at a basic level allows the mind and ‘blackhawks’ and Ulmnus parvifolia,

Restoration eory. “People prefer body to feel respite, a sense of relief. Chinese elm. ese plantings work

to be in natural environments, and

e design of the savannah as a screen against tra c on Hoofs

especially in savanna or parklike was based around two elements — Run Drive as well as the buildings

habitats. e long depth of view the edges and the savannah itself. across the street. is adds to the

across a relatively smooth, grassy e edges are important as they privacy and aids in the quietness on

ground surface dotted with trees give and hold the shape of the space. the site.

and copses… ey try to place e three savannah zones have

Since the Carlyle

their habitations on a prominence, di erent grass plantings to build the neighborhood is right outside of

from which they can safely scan edges. ese edges then transition historic Old Town Alexandria

the savanna…environment. With and blend from each zone into the it was pivotal to nd a way to

nearly absolute consistency these next. is brings cohesion into reference the heritage and history

landscapes are preferred over the roughly four acres of savannah of Old Town in the designed park

urban settings that are either bare across the whole site.

space. Additionally, there needed

or clothes in scant vegetations”

Savannah I is on the far to be a way to create biodiversity

(Mencagli and Nieri, 14). Further, West side of the site and is the and interest in a eld of grasses

Mencagli and Nieri pose “models rst landscape archetype a person (plus assist in the ease of planting

27

the space). A grid system based var. ‘standing ovation’ has a denser at 10 feet wide throughout the park

o brick patterns found in the vertical line hatch.

except for a small o set in savannah

sidewalks of Old Town Alexandria

e border of savannah I. e narrow 3-foot wide curved

was established. Savannah I & III I and savannah II entering from path o set was designed to allow

use the same 10-foot by 20-foot Eisenhower Avenue is planted with for the visitor to feel a greater sense

double basket weave pattern while a low edge of Carex appalachia, of immersion within the grasses of

savannah II uses a 10-foot by 30- Appalachian sedge, directly next the savannah. e 3-foot mowed

foot herringbone pattern. Each to the path. On the outside of the path is cut to the west of the main

‘brick’ represents one of four species Carex appalachia is Chasmanthium path and through savannah I. It

per savannah section. e species latifolium, Northern sea oats. starts about 15 feet into the site

in the savannah are all represented Northern sea oats were chosen for and loops back to the main path

by di erent hatch patterns with their braided seed pods providing an just behind the Quercus macrocarpa

variations of the same species having introduction to the many textures var. ‘urban pinnacle,’ bur oak urban

similar hatches to help identify the park visitor will experience as pinnacle. is path was designed as

that the grasses are from the same they continue down the path toward an alternative for someone wanting

family. For example, big bluestem the meadow or the forest. e low to feel a di erent type of seclusion

has a horizontal line hatch with a Appalachian sedge next to the taller than what the rest of the savannah

wider spacing between lines and Northern sea oats simulates a wider provides.

big bluestem var. ‘blackhawks’ has path as a person journeys through

e southern part of

a denser horizontal line. Similarly, the savannah. e openness here savannah I has a small berm that is

little bluestem has the same hatch will feel like it narrows as the edge planted with Quercus macrocarpa

as big bluestem except a vertical plantings change around the site, but var. ‘urban pinnacle,’ bur oak urban

orientation with little bluestem the width of the path stays consistent pinnacle; Pinus virginiana, Virginia

figure 24 - savannah section

28

ATTENTION RESTORATION THEORY

e idea of the therapeutic landscape cannot be truly understood without explaining Rachel &

Stephen Kaplan’s Attention Restoration eory. Attention Restoration eory has four requirements

that are needed to create a restorative landscape. ey are as follows: ‘being away,’ extent, fascination, and

compatibility.

‘Being away’ is taking a vacation from whatever is occupying the mind and exerting mental fatigue.

While it could be a week at the beach that will only partially ful ll the ‘being away’ requirement. A person

must also remove themselves from the taxing stimuli. ey could ‘be away’ by sitting in their backyard

doing nothing. In contrast, changing a work environment to a cabin in the woods does not qualify as

‘being away’ when there is still draining work to be done in the cabin. ‘Being away’ needs an environment

that does not have any sort of distraction which would prevent the mind from being at rest.

Extent requires two properties to be fully de ned: scope and connectedness. Essentially you

much have interest while also being taken to another place. Becoming truly invested in a movie or a

play will draw interest and allow for exploration of this ‘new world’ enacting involuntary attention and

allowing for the brain to rest. “ ey must be places that are capable of capturing and maintaining our

interests” (Mencagli and Nieri, 58).

Fascination, which relies heavily on involuntary attention, lets the mind rest. “Fascination is

important to the restorative experience not only because it attracts people and keeps them from getting

bored, but also because it allows them to function without having to use directed attention” (Kaplan and

Kaplan, 184). Watching the sun rise or set is an ideal example of fascination.

Compatibility is nding a space that is going to work with the person and not against them.

If a person seeks peace and quiet, a playground a er school gets out is not compatible with their goals.

Instead they may seek a private garden or bench by a river. e landscape must be in favor of the same goal

as the individual in order for the space to be restorative.

Attention Restoration eory provides the guidelines for the creation of a therapeutic landscape.

pine; Tsuga candensis, Eastern

hemlock; and Taxodium distichum,

bald cypress. Planting these trees on

and around the berm created more

height and a larger screen to mask

Savoy Street and the apartment

complex on the other side of it. e

southeastern corner of savannah I

has a second entryway into the

park to allow for those coming

29

from the apartment complex to

easily access the site and experience

it from a di erent point of view.

eir journey would start with a

crossroads between heading north

toward the savannah and meadow the savannah I border, however, the path to intersect two landscape

or south into the forest.

northern part is bordered with Carex archetypes, savannah III and the

Savannah II is the appalachia, Appalachian sedge and forest. In order to blend the two in

innermost part of the site. Here Liatris microcephala, dwarf blazing a naturalistic way, the trees from

there is a smaller 1-foot depression star. e purple owers of Liatris the forest were brought out from

to allow for water to collect and microcephala are used tie into the the denser area and placed more

feed the grasses. While the land is colors of the neighboring meadow sparingly as they approached the

lower, the height of the plants in and are a blending point between savannah III zone. Savannah III has

savannah II will grow higher due the savannah and the meadow.

the basket weave pattern of grasses

to a more constant source of water

Savannah III is the most leading to the forest. As a barrier

and direct sunlight. e lower and transitional space in the entire site. and blending method Deschampsia

western edges of savannah II mirror It is the one area where there is no exuosa, wavy hairgrass is planted in

figure 25 - savannah perspective

30

a loose spray. Deschampsia exuosa has a light seedy texture. Two efourthbrickworkpatternplantis

is a part sun/part shade grass which others are Schizachyrium scoparium, Andropogon virginicus, broomsedge,

works well in the transitional space little bluestem, and Schizachyrium which has a rough texture and

to blur the edge of the savannah into scoparium var. Standing Ovation, golden color. With the addition of

the start of the forest. One of the four little bluestem variation standing Deschampsia exuosa, Savannah III

plants represented in brick working ovation. Schizachyrium scoparium has the widest collection of textures

pattern in Savannah III is Bouteloua var. Standing Ovation brings deep of all the savannah areas.

curtipendula, sideoats grama, which red hues into the Savannah III zone.

All three savannah areas vary

in plantings, but are held consistent

by their brick patterning. A total of

twelve grass species are used across

the roughly four acres of savannah

space. e diversity across the three

zones gives an interlacing of hue

and grain, which can be enjoyed as

they sway amongst each other in the

wind. It brings a quiet and peaceful

view to someone seeking calmness

in their day.

figure 26 - savannah plant list

31

figure 27 - savannah planting plan

32

figure 28 - plant texture collage

33

34

MEADOW

e role of the meadow is to Resilient Landscapes. Both had themselves. For example, matrix

elevate the site both guratively and di erent approaches to the problem, 1 does not intersect with another

literally. It is to be an explosion of which meant picking one or nd a matrix 1. Each individual matrix is

textures, colors, shapes, and species. combination of the two that would composed of ve oral species, one

e planting plan for the meadow work.

grass, and one species of crocus. e

was the most challenging part of

e meadow planting plan role of the crocus is to provide a pop

the Carlyle Solace Park design. is designed as a matrix-grid hybrid. of color in the early spring before

How do I go about planting a A radial grid was used to lay out the late spring/early summer plants

meadow? Especially if the meadow the sections of where the plantings begin to bloom. e following

is to look like a eld of wild owers, would be. e center of the circle species were used to populate the

completely naturalistic. What does was placed at the high point of the

a planting plan look like when I site, 38.5 feet in elevation. From

do not want the design to look like there, the radial grid was broken

there is a planting plan?

up every 15º moving outward from

Two designers were the center of the circle. e sections

researched heavily in an attempt were divided up at every 1-foot

to understand the meadow and contour line with the widths being

how to implement it. Piet Oudolf, based o the 15º radii. Each section

renowned landscape architect of varied in size but was bound by the

the High Line in New York City, 15º and topographic changes. From

and omas Rainier, co-author here a di erent matrix group was

of Planting in a Post Wild World: randomly assigned to each section;

Designing Plant Communities for the sections do not align next to

35

hill meadow:

• Amsonia hubrichtii, threadleaf bluestar

• Asclepias purpurascens, purple milkweed

• Asclepias tuberosa, butter y milkweed

• Aster cordi orus, common blue wood

aster

• Crocus chrysanthus ‘Goldilocks,’ snow

crocus

• Crocus tommasinianus, snow crocus

• Echinacea purpurea, purple cone ower

• Echinacea purpurea var. ‘White Swan,’

purple cone ower var. ‘white swan’

• Eryngium planum, sea holly ‘Blaukappe’

• Eupatorium stulosum, Joe Pye weed

• Monarda stulosa, wild bergamot

• Pycnantheum muticum, mountain mint

• Salvia x sylvestris ‘Mainacht,’ wood sage

May night

• Schizachyrium scoparium, little bluestem

• Schizachyrium scoparium var. ‘Standing

Ovation,’ little bluestem var. ‘standing

ovation’

Every species is represented

in at least two matrices and no

two matrices are the same. To best

represent the various plantings and

also show the overlap of species

between matrices, each species was

assigned an icon. Species that were

represented more than once, but

as a di erent cultivar had a similar

icon changed slightly in orientation

and color. is way a viewer could

easily identify the representation of

milkweed or echinacea on the plan

while still understanding there are

various cultivars shown in the plan. I

used the icons of each plant to create

a pattern speci c to the makeup of

each matrix. e result is ve unique

patterns that are then overlaid onto

their speci c section of the meadow

‘quilt.’ When the grid and contour

lines are removed all of the icons

representing the various plant

species in the meadow show up as a

fully naturalistic and random array

of plants. is gives the design of

the meadow the structure needed

for someone to plant it and the

looseness of a wild ower meadow

once fully planted and growing.

Creating a design that can be

planted with ease and also appear as

random as possible was challenging,

but necessary for the goal on this

portion of the site.

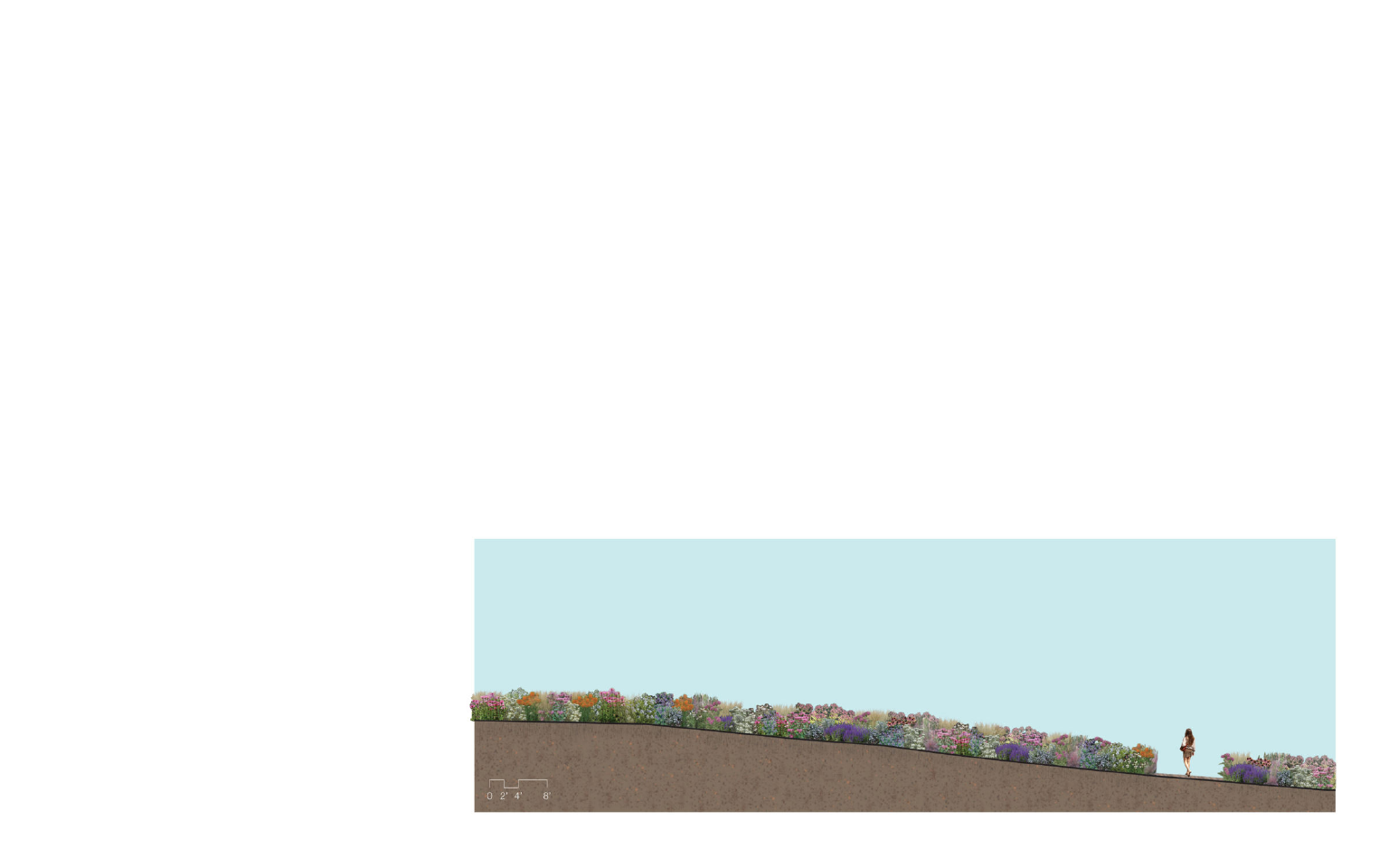

e meadow’s role is to

represent the beauty on the site. It

allows for the visitor to experience

beauty. Frederick Law Olmsted

wrote on the subject of “beautiful

figure 29 - meadow section

36

THE OUDOLF METHOD

Piet Oudolf, a Dutch landscape designer, is widely renowned as the designer of New

York City’s High Line, Chicago’s Lurie Garden, Pensthrope Garden in Norfolk, England. He

has designed public spaces as well as private residences in both North America and Europe. His

designs are highly texturized and he takes great care in selecting plants with year-round seasonal

interest. For example, the dried seed heads in the winter are just as important (and beautiful) to the

design as the same plant’s colorful owers in the summer. He suggests using plant combinations

that bring forth the essence of a wild habitat, allow for some spontaneity, and use plants that can

be recognized in their natural element.

Oudolf ’s designs are full of brushes of colors that sweeping across the space and the

breathtaking clumps of textures they create. Oudolf and Kingsbury de ne meadows and prairies

as a “typical habitat where one species — or usually one category — dominates, o en grasses or

grass like plants, but with a large number of other species present in much smaller numbers” (78).

When planting he uses a hierarchal design of primary plants (the main impact), matrix plantings

(a species used en masse), and scatter plants (which are just exactly as they sound). Oudolf ’s

plantings are made into groups and then placed around the site on a planting plan using icons and

colors to present where they go. He uses di erent iconography for the impact plants, the matrix

plantings, and the scatter plants so that they can be easily identi ed in their correct grouping.

“ e [role of the] matrix evokes the situation in many natural habitats where a small number of

species form the vast majority of the biomass, studded with large number of species present in

much smaller numbers, but which are a visually important element” (Oudolf and Kingsbury, 99).

Oudolf ’s work to create naturalism in the landscape is due to his “successful mixed planting…

which can function with relatively little maintenance almost as an arti cial ecosystem” (Oudolf

and Kingsbury, 210). His planting plans are just as striking as a piece of art found in a gallery.

However, according to Kingsbury, “the overriding factor which makes a Piet Oudolf planting

work for the long term is that his plants are long-lived” (236). e needs of the plant to survive

are no less important than their placement and role on the site.

37

figure 30 - textural details - oudolf’s planting at hummelo

figure 31 - lurie garden - chicago, illinois - designed by oudolf

38

THE RAINIER METHOD

omas Rainier is the co-authors of Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant

Communities for Resilient Landscapes. He works with his co-author and fellow landscape

architect, Claudia West, at Phyto Studio in Arlington, Virginia. e work of Phyto Studio

focuses on designed plant communities. “Designing with plant communities can not only link

nature to our landscapes, but also bring together ecological planting and traditional horticulture”

(Rainier and West, 20). Resilient plant communities contemplate the ecological niches of plants

and use systems to create collections that are at peak function when together. “‘ e key is to pay

attention to how plants t together,’ Rainer said. ‘To pay attention to their shape and behavior.’

is involves not only their growth patterns aboveground, but their root types, which permit

plants that are surface-rooted, such as many ground covers, to coexist with deep-rooted meadow

owers and grasses” (Higgins). Which plants thrive in the what soil type? Does the plant’s root

structure work with its surrounding plants? Rainier and West suggest the following principles be

considered when designing resilient plant communities:

1. Related populations

2. Stress as an asset

3. Cover ground by vertically layering plants

4. Make it attractive and legible

5. Management, not maintenance

is requires signi cant learned knowledge of each plant’s ecological preferences. Knowing which

perennials grow best with which grasses or ground covers leads to a successful plant community.

While it may seem daunting at rst, Rainier and West state “our focus is on plants naturally

adapted to their speci c sites. It is the relationship of plant to place we want to elevate” (41).

e plant must be suitable for its corresponding archetype in order to be successful, regardless

of its status as native or exotic. Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for

Resilient Landscapes advocates a fresh look at planting plans that o en stipulate only using native

plants. According to Rainier and West, “the time is right for this shi in thinking” (62).

39

figure 32 - thomas rainier’s home garden - arlington, virginia

figure 33 - bio-retention planting - lancaster, pennsylvania - designed by phyto studio

40

figure 34 - meadow plan - ‘quilt’ view

figure 35 - meadow planting plan - matrix view

figure 36 - meadow planting plan

41

figure 37 - meadow plant list

42

natural scenery ‘[it] employs the with beauty, we can opt out of our

mind without fatigue and yet ordinary distractions” (Mosko and

exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet Noden, 17). Visiting the meadow at

enlivens it; and thus, through the Carlyle Solace Park is an experience

in uence of the mind over the in immersive environments. e

body, gives the e ect of refreshing landscape is so invigorating that you

rest and re-invigoration to the can let go of the day’s strife and allow

whole system’” (Stuart-Smith, 91). the brain to experience calmness.

Looking at something beautiful, “It is not the plants themselves that

like a piece of art in a museum, have power; it is their patterns,

releases dopamine and serotonin in textures, and colors - particularly

the brain. e lush, brilliant colors those that suggest wildness - that

of the meadow owers intermixed become animated as light and

with grasses is Carlyle Solace Park’s life pass through them” (Rainier

art piece. “Dopamine generates and West, 24). e meadow is a

a sense of purpose and a state of combination of wildness with a

optimistic expectation, and it boosts precision construction hidden

connectivity and communication within the roots of the plants.

throughout the brain” (Stuart- “ is is why it’s important to create

Smith, 102). Serotonin is the brain’s beautiful garden environments in

mood stabilizer; de ciencies in which we can lose ourselves enough

serotonin is linked to depression. to discover insights otherwise

An improvement of both dopamine hidden by our involvement with

and serotonin levels increases the busy unstimulated spaces that only

mental well-being of a person.

encourage distraction” (Mosko

When someone is in the and Noden, 29). e meadow is a

hospital, we take them owers to space to rest the eyes and take in a

make them feel better. e meadow di erent type of stimulation, that of

makes the visitor feel better. It our natural world.

gives them something else to think

about, look at, focus on as they

escape their day for twenty minutes

of respite. “When we are engaged

43

figure 38 - meadow elevation

44

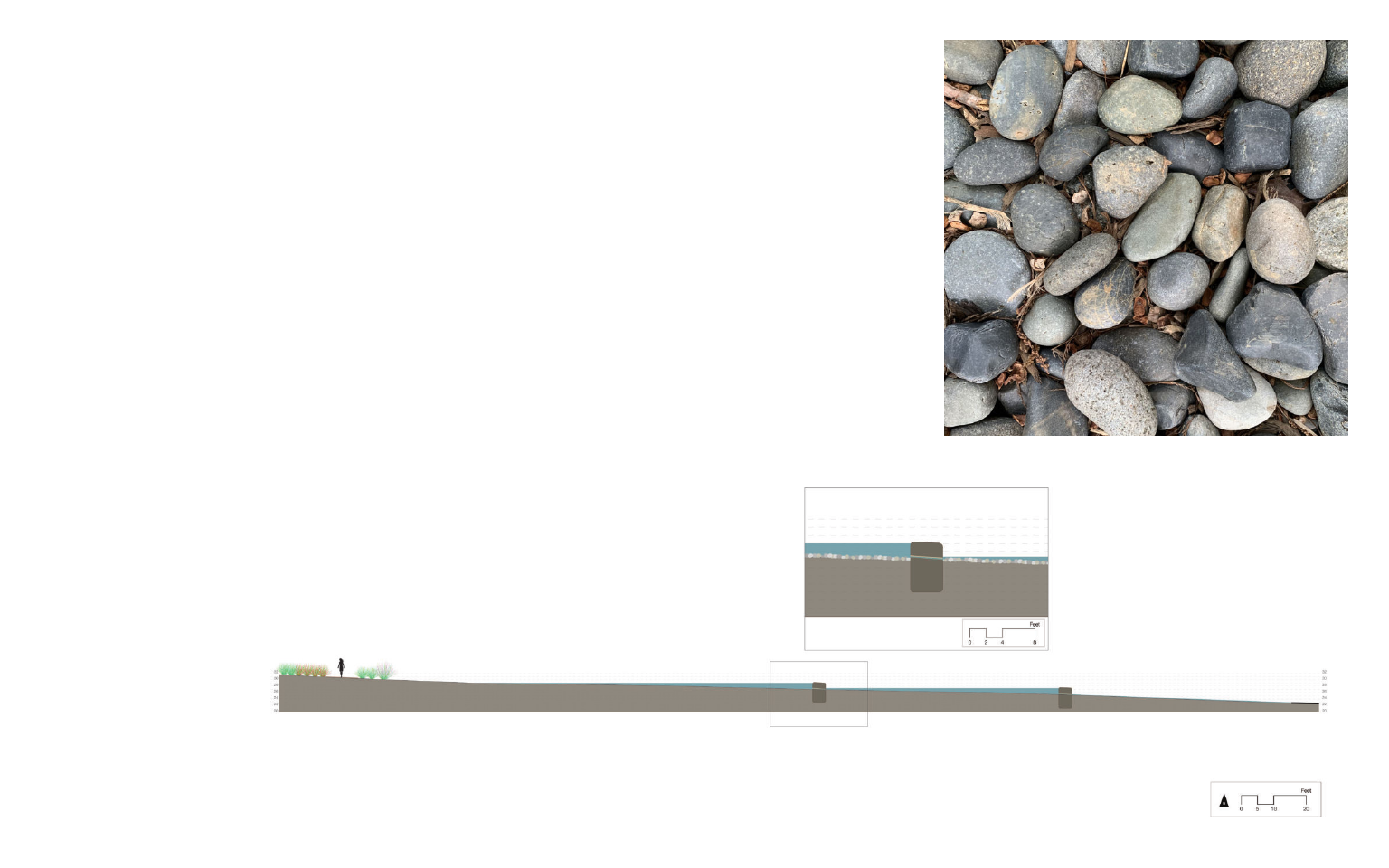

archetype. e center is a bed river

rocks no bigger than six inches. e

stones in the bed of the swale add a

di erent type of hardscaping, which

still appears as a natural site element.

e plantings are implemented as if

the path surrounding the swale did

not exist and the bed of the swale

S WA L E

was the dividing line. is helps

to amplify the naturalism sought

e existing topography had site and entering into Hoo ’s Run. be wide enough for a safe journey

a slight swale in it leading to Hoo ’s Lessening the sedimentation in this across. While slight, this is also a

Run. is existing feature is used watershed will help keep it owing reference to the stepping-stones seen

and ampli ed it by deepening the and prevent it from becoming a dry in a Japanese garden. e stepping-

cut of the swale and to allow for the stream bed in need of restoration. stone dams of the swale constitute

cut to ll the height needed to raise

One element of the swale the one area of the site that has

the meadow’s hill from the small design was to implement an area more obvious geometric structure.

in the site design. As the plants on

either side of the swale grow, they

will start to ll in and encroach the

swale bed lessening the hardness

of this portion and combing three

areas into one hybrid area in the

lower topography of the site.

mound that it was to something that a visitor may walk along or sit e sides of the swale are planted

more substantial. Deepening the down and relax; they needed to to match the nearest landscape

swale allowed for two check dams

to be installed formed from large

four-foot wide stones that span

the 27’ and 25’ contour lines. e

check dam works by slowly releasing

storm water through small four-

inch holes in the dam wall and

preventing what can be a toxic rst

ush collected in the urban area.

e swale will control the runo by

giving the water direction on where

to ow and collect. It will aid in

preventing extraneous runo and

sedimentation from leaving the park

45

46

figure 39 - example of river rocks

figure 40 - swale section

figure 41 - swale planting plan

47

figure 42 - swale plant list

48

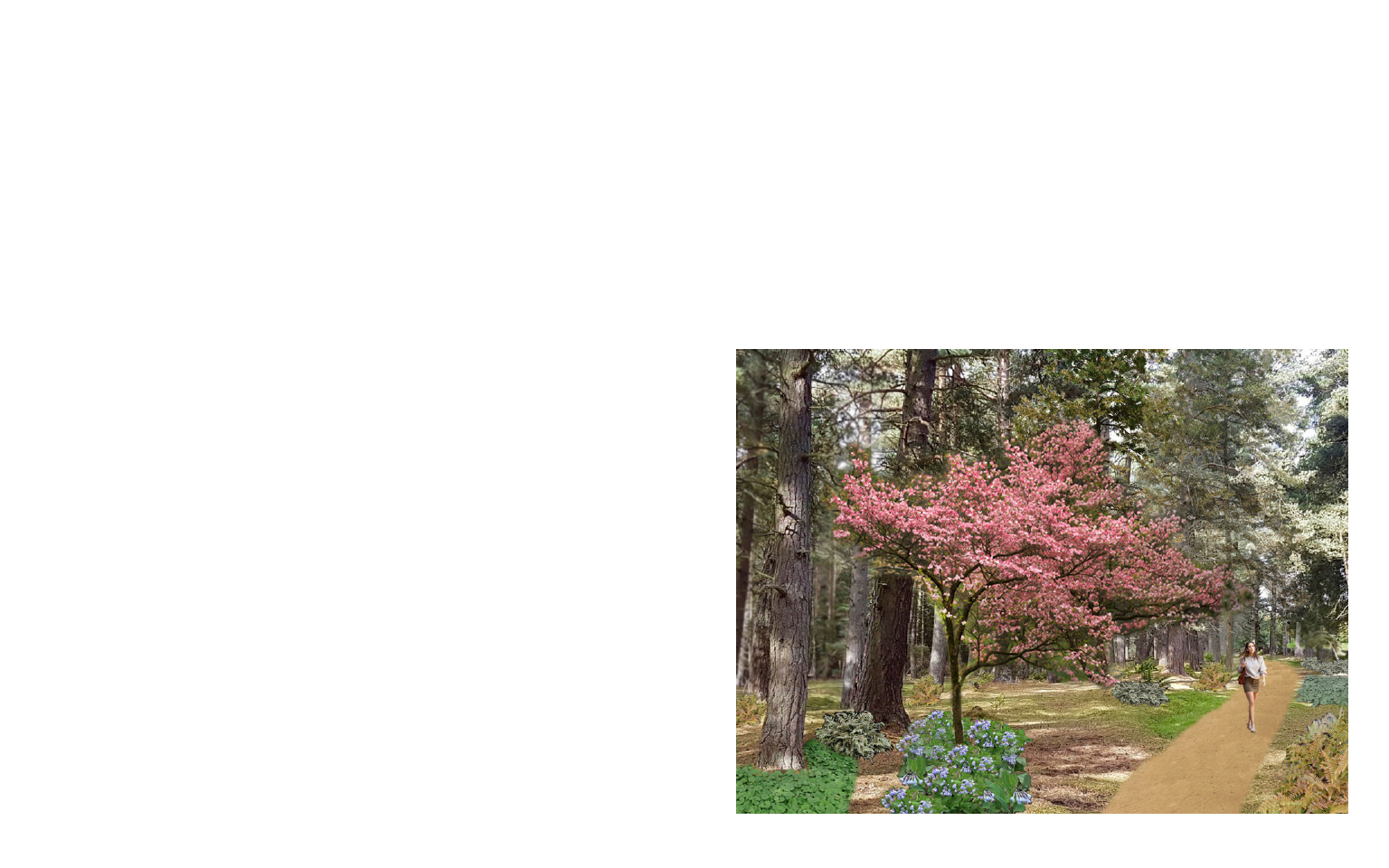

FOREST

e forest is the cohesive are lined with Pinus virginiana emissive potential of phytoncides

end to the three landscape and Tsuga canadensis. ese trees (Mencagli and Nieri, 93), which

archetypes in Carlyle Solace Park. are used as a border to shelter the makes it an ideal species to be located

It brings in di erent sensory space, quieting the inside of the on a forest bathing site. “Evergreens

elements than those experienced forest by blocking road noise and like pine trees, cedars, spruces and

on the rest of the site. e forest is screening the apartment complex. conifers are the largest producers of

made up of eight trees; three species

e Quercus genus lines the phytoncides” (Mosko and Noden,

of oaks: Quercus coccinea, scarlet edges of the paths and are intermixed 91). e pine core of the forest was

oak; Quercus macrocarpa, Bur oak; across the entire forest area. is created with this in mind, grouping

Quercus macrocarpa var. ‘Urban allows those walking along the species that are more fragrant

Pinnacle’; Bur oak cultivar Urban path to connect with the oak trees, with phyoncides than others in a

Pinnacle; plus three species of pines: hugging them if they want, or just central area to amplify the natural

Pinus sylvestris, Scots pine; Pinus sitting under them. e oaks here e ects of the environment. It was

rigida, pitch pine; Pinus virginiana, improve the canopy cover and aid equally important to enhance the

Virginia Pine; as well as Tsuga in the enhancing the visitors bio- percentage of negative ions in the

canadensis, Eastern Hemlock; and energetic body current, which can space. “Many forest environments

Cornus orida, owering dogwood. help reduce stress. e inner part suitable for the practice of forest

e dogwood is the only understory of the forest is lled with the oaks bathing also have a signi cant

tree. It brings color in the early and Pinus rigida. In the center of level of air ionization o en with

spring to the experience of the the forest there is an opening where a predominance of negative ions

site and subtly ties in the color of there is a grove of Pinus slyvestris. over positive ones” (Mencagli and

the meadow to the forest zone. Pinus slyvestris, Scots pine is listed Nieri, 112). e forest encompassed

e East and West of the forest as one of the species with greater a wider range of healing methods

49

as the more healing methods to guide visitors to enter the site each understory plant I assigned an

e understory of the at speci cs spots and not enter icon, similar to how I approached

forest is composed of Asarum from o the pathway, disturbing the planting in the meadow. Each

canadense, wild ginger; Dryopteris the plants. e entry point of the icon represents the general area

eerythrososa var. ‘Brilliance,’ forest is at the corner of Savoy where the plant will be, with the

autumn fern; Athyrium niporicum, Street and John Carlyle Street. understanding that as time passes

Japanese painted fern; Mertensia

e placement of the they will continue to ll in the

virginica, Virginia bluebell; Eurybia herbaceous layer of the forest is forest oor. Mertensia virginica

divaricata, white wood aster. e designed to allow the plants to is speci cally placed underneath

ferns are used heavily along the grow and expand lling the space all of the Cornus orida in a tear

outside edges of the forest to help over time. In order to represent drop or paisley-shaped formation.

create a barrier. e intention is the areas too start the planting of Originally, the goal was for the

figure 43 - forest perspective

50

BIO-ENERGY & NEGATIVE IONS

e Quercus genus emits high bio-energetic resonance. “Plants emit bio-electromagnetic

elds that are able to in uence the state of our organs to varying extents” (Mencagli and Nieri,

128). e oak is considered highly bene cial as compared to others, like the walnut, which is

considered disruptive to a person’s energetic eld. In order to receive bene ts from the oak, a

person needs to be no further than “12 to 16 inches from the trunk” (Mencagli and Nieri, 133).

For even greater bene t, hugging the tree creates a bio-energetic connection and grounds the

person to the earth. “ e oak response with enthusiasm to the hug with a positive e ect on all

our organs, especially the nervous and immune systems, ovaries, adrenal glands, and the thyroid”

(Mencagli and Nieri, 132). Grounding is technique where the human body’s circuitry is realigned

with that of the Earth through direct contact. “Evidence suggests that the Earth’s negative

potential can create a stable internal bio-electrical environment for the normal functioning of all

body systems” (Chevalier et al.). Becoming more connected to the landscape, by being present in

it, is bene cial to human health.

Negative ions are the more bene cial of the two ions, one being positive, the other negative,

to human health. ese ions are “electrically charged molecules or atoms in the atmosphere…

formed when a gaseous molecule or atom receives su ciently high energy to eject an electron.

Negative air ions are those that gain an electron, while positive air ions lose an electron” ( Jiang et

al.). Areas of the landscape that have a higher concentration of negative ions are waterfalls (where

the water molecules are breaking apart as they hit rock) and areas of denser well-established plant

life, like a forest. “Unfortunately, however, urban and indoor environments do not even come

close to the ionization levels typical of more natural surroundings” (Mencagli and Nieri, 105).

is gives an even better reason to leave the o ce to go for a walk in a park, speci cally a forested

one. e expansion of urbanism is not only decreasing our green space, but at the same time

increasing the percentage of positive ions in the atmosphere. “Environments with a predominance

of negative ions are shown to be e ective in reducing states of stress, depression, and psychological

maladies connected to stressful events” (Mencagli and Nieri, 107). Additional tree canopy and

lush plantings will aid in the increase of negative ions and therefore the health of those who visit

these verdurous spaces.

51

figure 44 - forest layers axonometric

52

Mertensia virginica to appear to fade Athyrium niporicum and so on. be solely represented by the pine

away from under the Cornus orida Aside from the formation of the needles. ere is a strange so ness

so that the brighter oral colors of Pinus sylvestris grove in the center to a bed of pine needles when it is

the forest are together and produce of the forest the borders are the looked at. I wanted to create a pine

pops of color throughout the mostly most structured plantings in this oasis in the center of the forest. A

earth-tone journey of the forest. e archetype. is again, was mainly quiet place which could allow for

teardrop formation also mirrors the to guide visitors on where to enter someone to step into the area and

interior shape of the forest path. the site for the best experience. breathe in the phytoncides emitted

While this was unintentional, it

e inside core of the forest by the pines. e center of the forest

created a nice form of cohesion and is more barren with herbaceous is the epicenter of the entire space.

subtle poetry to the forest oor. plants. is is to allow the oor to Quiet, full of smells, full of texture,

e other forest oor

plantings are somewhat sporadic.

Eurybia divaricata, Asarum

canadense, Dryopteris eerythrososa,

and Athyrium niporicum all hug the

edges of the path on the inner areas

of the forest archetype. is allows

for the species to be experienced by

the visitor in various combinations

as they proceed through the park.

is changes on the eastern edge of

the forest where Asarum canadense

forms a stronger diagonal pattern

to break up the edge experience

in a more systematic way as the

visitor walks along the path

adjacent to Eisenhower Avenue.

ere are collections of Asarum

canadense, then Eurybia divaricata,

then Asarum canadense, then

Dryopteris eerythrososa followed

by Asarum canadense again, then

figure 45 - forest plant list

53

figure 46 - forest planting plan

54

PHYTONCIDES

ere is a di erent smell when you enter a forest. It is something easily noticed, but hard to

identify. e smell comes from phytoncides. According to Dr. Qing Li, “phytoncides are the natural

oils within a plant and are part of the tree’s defense system” (89). ese are emitted by the trees to

ght against fungi, bacteria and insects. “ e main components of phytoncides are terpenes” (Li, 91)

which includes monoterpenes. A monoterpene is an organic compound that is emitted by a variety of

plants. It is a standard component of essential oils and many resins. “Essential oils have been known

to humans for thousands of years and their medicinal use is extremely widespread across all latitudes”

(Mencagli and Nieri, 79). Walking through the forest phytoncides are inhaled, by increasing the

amount of time we are in the forest, we increase the amount of time we are exposed to phytoncides.

Subjection to phytoncides boosts the human immune system. Additionally, “exposure to essential

oils [is known] to li depression and help with anxiety” (Li, 94). e more time spent in and around

phytoncides or forests with higher percentages of conifers the better a person will feel. A walk in a

pine stand, for example, is more than just an adventure or exercise, it is a healthy healing experience.

a calming space to allow someone to a sense of closure at the end of the

fully relax and spend time relaxing trip. Even if the journey takes the

andateasebeforeturningupthepath visitor back toward Hoo ’s Run

to walk toward their job or home. or the African American Heritage

e idea of a healing forest Park. It was important that the

started the entire project from a design of the site was further

philosophical level in my research reinforced by the forest element.

to a physical level in the Carlyle

neighborhood when I walked

through the urban forest. Shinrin-

yoku inspired the project so it is

tting that the end of the journey

through the Carlyle Solace Park be

the forest again. ere had to be

figure 47 - photo of conifers

55

figure 48 - forest center sketch

56

figure 49 - final collage

57

58

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

is project started when I out when they are going through a Incorporating three landscape

bought a book. I was su ering from rough time? ere are therapeutic archetypes into one site was a way

stress and anxiety and wanted to gardens attached to hospitals, to expand outward from the success

nd another way to help myself heal. rehabilitation centers, or retirement that is seen with shinrin-yoku and

What I found was forest bathing communities, but we need more use other healing mechanisms

and an idea of how to help others and they must be in places easily found in the natural environment.

who su ered as well. According to accessible to anyone at any time. roughout this project I created

Mental Health America, one in ve

My research into many collages. ey show site

adults su er from mental illness. therapeutic spaces expanded my evaluations, project goals, textures,

Mental illness are ailments that view of how versatile the landscape and exude the feelings I wanted to

e ect behavior, feelings, and/or the is and how simple design decisions express with my nal product. e

mind. It is not the easiest type of can go a long way in creating healing nal collage is my way of showcasing

ailment to live with or to attempt environments. e design of this the new space that I had created, but

to heal from. It takes a lot of work space was vital to my goal to bring also showcasing my journey through

and it is not the most a ordable. awareness to mental health. is this project and through landscape

ose who su er seek solace - project is not the creation of a architecture. It expresses what

“comfort or consolation in a time of park. is project is the creation inspired me moving through this

distress or sadness” (Stevenson and of a health landscape. e space project. It shows the elements that I

Lindeberg) What makes a place had to be welcoming, a safe wanted to make sure to incorporate.

a solace? is was one of the rst environment, accessible, free of any ItincludessomeoftheworkthatIdid

questions I wrote to myself when I nancial requirement. It had to and elements I found inspirational.

started my thesis journey. How can evoke openness while still feeling Finally, it exudes my passion for

I create a space that people will seek like the safest place in the world. texture, color, and pattern. A space

59

that has serenity that has openness lessen people’s burden with the mental illnesses, I wanted the space

and has security all at the same time. landscape. is project is a space the to appeal and assist as much of the

And I hope that this does that and person who is living on the street urban population as possible. e

really creates this inviting space. and does not understand why they views of mental health care need to

Our public green spaces can do so are hurting, for the person who is be broadened and with broadening

much more to help those su ering working at a fast food restaurant the knowledge of a subject, we can

from mental illness. I designed a and does not have the funds to visit expand ways to solve it, look at the

place that serves as an example to a therapist or to see a doctor, for problem di erently. e Carlyle

leaders in city governments, urban the person working full time while Solace Park is an alternative method

planning, landscape architecture, trying to earn a degree and take care to heal not only an individual

and the mental health community. of their family all at the same time. but whole communities as well.

With this project I wanted to bring is can be their place, where they

to light the importance of mental can go and heal. Everyone’s life is

health and that there are ways to di erent and so are their struggles or

figure 50 - photo of pine needles

60

REFERENCES

Chevalier, Gaétan, et al. “Earthing: Health Implications of Reconnecting the Human Body to the Earth's Surface Electrons.”

Journal of Environmental and Public Health, vol. 2012, 12 Jan. 2012, pp. 1–8., doi:10.1155/2012/291541.

Frontiers. "Stressed? Take a 20-minute 'nature pill': Just 20 minutes of contact with nature will lower stress hormone levels,

reveals new study." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 4 April 2019.

<www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/04/190404074915.htm>.

Higgins, Adrian. “Why Manicured Lawns Should Become a ing of the Past.” e Washington Post, 2 Dec. 2015.

Jiang, Shu-Ye, et al. “Negative Air Ions and eir E ects on Human Health and Air Quality Improvement.” International Journal

of Molecular Sciences, vol. 19, no. 10, 28 Sept. 2018, p. 2966., doi:10.3390/ijms19102966.

Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. e Experience of Nature: a Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Li, Qing. Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness. Viking, 2018.

Mencagli, Marco, and Marco Nieri. e Secret erapy of Trees: Harness the Healing Energy of Forest Bathing and Natural Landscapes.

Rodale, 2019.

Mosko, Martin Hakubai, and Alxe Noden. e Sound of Cherry Blossoms: Zen Lessons om the Garden on Contemplative Design.

Shambhala, 2018.

Oudolf, Piet, and Noël Kingsbury. Planting: a New Perspective. Timber Press, 2014.

Rainer, omas, and Claudia West. Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes. Timber

Press, 2016.

“Quick Facts and Statistics About Mental Health.” Mental Health America, 2021, www.mhanational.org/mentalhealthfacts.

Stevenson, Angus, and Christine A. Lindeberg. e New Oxford American Dictionary: ird Edition. 3rd ed., Oxford University

Press, 2010.

Stuart-Smith, Sue. Well-Gardened Mind: e Restorative Power of Nature. Scribner, 2020.

Yuen, Hon K., and Gavin R. Jenkins. “Factors Associated with Changes in Subjective Well-Being Immediately a er Urban Park

Visit.” International Journal of Environmental Health Research, vol. 30, no. 2, 2019, pp. 134–145.,

doi:10.1080/09603123.2019.1577368.

61

figure 51 - photo of forest

62