new animism:

relational

epistemologies

and expanding

western

ontologies

Josh Bou hton

Uni ersity o Queensland

Keywords

Ne animism, e opsy holo y, relatedness,

Indi enous, nature.

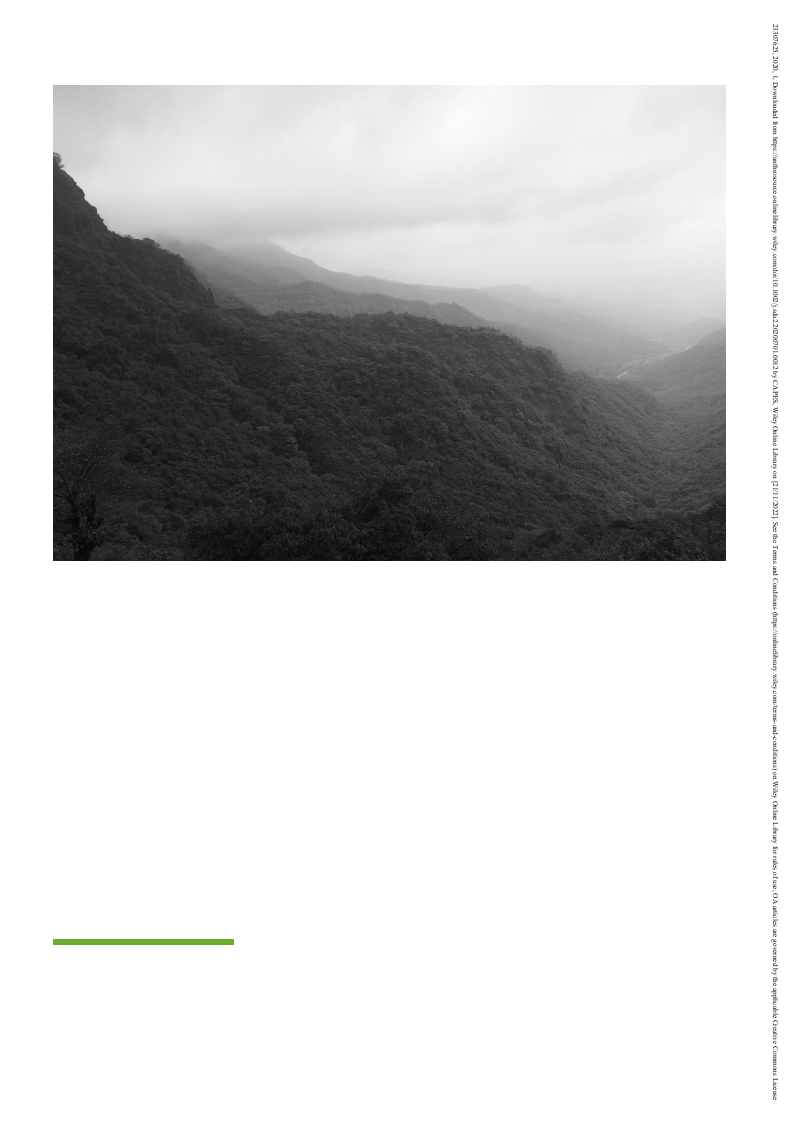

“Western Ghats” by Laura Murray (2017).

Introduction

Animism is said to be the most fundamental

form and starting point of religious belief

(Stringer, 2013). This concept has been used in

cultural anthropology since the late 1800s but,

due to inconsistencies in research ontologies,

fell out of favour as an ethnographic research

tool (Bird-David, 1999). A return to, and

modification of, this concept has been witnessed

over the turn of the century as researchers seek

to better understand how the tool may once

again be utilized. In this essay I discuss how

modern conceptualisations of animism may

shape human/non-human interactions and

relations. I provide a brief history of the concept

and discuss how its limitations excluded it from

cultural anthropology’s tool kit for the better

part of a century. Following this, I outline the

contemporary conceptualizations of animism,

or new animism, and how they seek to address

the term’s original misdirection. Modern use

of animism in South India, South America and

Burkina Faso highlight the variability within

the concept itself as well as the consistency

of relational epistemolo y: bridging the gap

between the “self” and “other.” To conclude this

essay, I explore the possibilities of Western

(and global) integration of traditional peoples’

epistemologies to reduce Cartesian dualism

of humans and nature, which contribute to

the exploitation and degradation of natural

beings. This is seen in the emerging field of

e opsy holo y, which seeks to address issues

inherent in pro-environmental communication

with the general public through a recalibration

of philosophical understandings.

animism: primitive and savage

56

Notions of animism in the West have existed

since the 6th century BCE (Harding 2013),

though Edward Tylor’s work in the late 1800s is

a commonly accepted origin (Bird-David, 1999;

Malville, 2016; Stringer, 2013). Tylor borrowed

the idea from Stahl, a 17th century alchemist

(Bird-David, 1999); however, contemporary

anthropologists and scholars of traditional

peoples deemed it morally unacceptable (Bird-

David, 1999; Malville, 2016; Stringer, 2013). Many

consider Tylor a father of cultural anthropology

of the “modernist” period, in which science and

evolutionism were held in the highest regard.

Through second-hand accounts of “primitive

peoples,” he defined a concept of animism. The

traditional/indigenous peoples that lived under

this banner believed in the existence of spirits,

whom were embodied in all human and non-

human entities. From this Tylor posited that

the minds of animistic traditional peoples were

similar to that of children who attribute living

qualities to inanimate objects, concluding that

their societies were cognitively underdeveloped

(Bird-David, 1999). This line of thought directly

stems from the evolutionistic mind frame of

the modernist period which presented animism

as the “root” of religion, and thus less evolved

in comparison to monotheistic religions

(Christianity, Islam, etc.), and importantly,

science. Tylor entered this field of study with

an interest in the spiritualist movement of

the time, which he argued was a “survival and

revival of savage thought” (Bird-David, 1999,

S69). His work on animism was collated and

presented in the 1871 book Primitive Culture:

Researches into the Development of Mytholo y,

Philosophy, Reli ion, Lan ua e, Art and Custom.

Whilst Tylor touched on important concepts

within cultural anthropology, his approach

was condescending to traditional peoples and

the subject retains a stigma to the present day

(Malville, 2016).

Reignited by Hallowell’s 1960’s ethnography of

the Ojibwa people and the intrinsic animation

of objects within their language, notable

anthropologists such as Eduardo Viveiros

de Castro, Philippe Descola, and Nurit Bird-

David began to revive the concept of animism

through the turn of the century and have

opened an inquiry into animism’s ideas about a

world alive (Harvey, 2013). In contrast to Tylor’s

positivist approach to notions of “life,” “nature,”

and “personhood,” contemporary scholars

have suggested a relational epistemolo y to

develop better understandings of “local

concepts” (Bird-David, 1999). Through what is

now viewed as misdirected understandings,

theoreticians in the modernist period assumed

“primitive peoples” shared the same notions

of “self” to natural objects, “primitive peoples”

were deemed misguided (Bird-David, 1999).

In contrast, relational epistemology seeks

to understand the world via a primary focus

on relatednesses (relationships between

the human and non-human) and avoids the

modernist dichotomies of natural/supernatural

and spirit/body (Bird-David, 1999).

New Animism: Relational Epistemology

“Animism is about a world full of immediate

relational beings” (Naveh & Bird-David, 2013,

27). Naveh & Bird-David’s (2013) chapter in

Graham Harvey’s Handbook of Contemporary

Animism explores the ideas of animism,

conservation, and immediacy (regular exposure

to something as in one’s everyday life). They

state that animism is absent from the West

due to the lack of immediacy ) in engagements

with plants, animals, and other natural objects.

They explore immediacy through ethnographic

observation of forest dwelling Nayaka people

in the Nilgiris hills in South India. The

region has become a hotspot for regional and

global ecological development and has been

recognised as a UNESCO biosphere reserve since

the 1970s. The authors state that during a 30-

year gap between ethnographic observations,

the Nayaka people have managed to retain

their relational epistemology despite economic

pressures. The Nayaka’s animistic epistemology

places greater significance on knowing how to

behave with relations to nourish them, over the

dualistic notion that things are separate from

oneself. Despite achieving conservation in the

region, it has not been cognitively pursued and

behaviour with relations has been shown to be

variable within the Nayaka. According to the

authors, tribal members display mindfulness

and care when harvesting or hunting for their

immediate use or consumption but not when

conducting similar activities for economic

means. Despite these con icting actions,

animism and relational epistemology present

opportunities for recognising contemporary

Western society’s utilitarian epistemologies

57

that contribute to the degradation of

environmental health.

Descola’s (2013) ethnography of the Achuar

people in the borderlands between Ecuador and

Peru also provides clear examples of relational

epistemology at work. The Achuar believe

that all plants and animals are relatives and

possess a soul ( aken) which classifies them

as persons (aents). Maintaining good relations

with these aents is vital to the lives of the

Achuar. Disrespecting the spirits puts at risk

familial and neighbourly relations, hunting

success, and conjugal harmony. Distinctions

between persons are drawn not via di erences

in appearance but through a hierarchical

order of communication, which directly

challenges Cartesian dualism. The Achuar place

themselves at the top of the pyramid as they are

able to see and communicate with each other

in the same language. Exchanges with non-

humans are possible via anents (incantations)

which are not immediately obvious and appear

mostly in dreams or hallucinogenic trances.

Despite endowing the non-human with souls,

the Achuar exclude most insects, fish, grasses,

pebbles and rivers from their network of

subjectivity. This highlights inconsistencies

in the term “animism” between di erent

traditional communities, yet the notions of

relatedness remain.

Animism and relational epistemology need not

take the preconceived form of spiritualised

natural objects that first comes to mind.

Stringer’s (2013) ethnographic enquiry into

the people of Burkina Faso delivers another

contemporary example of animism, free from

modernist prejudices. The animistic people of

Burkina Faso treat spiritual beings as a fact

of life. These spirits engage with the human

population by inhabiting inanimate objects

such as statues and masks, which Stringer

acknowledges is not animism expressed in

the most basic form of relations between the

spiritual and material worlds. Rather, this

is a highly sophisticated mode of religious

engagement with the non-empiri al other, or

that which cannot be measured. He compares

this engagement with that of women in the UK

communicating with dead relatives and God.

Stringer concludes that the people of Burkina

Faso hold a relationship of fear and uncertainty

with their spiritual others, which contrasts

with women in the UK whose relationships

consist of coping mechanisms and love.

Further contrasts are in de Castro’s (2004)

ethnographic probing of Amerindian animist

ontologies. The use of anthropomorphism

among Amerindian peoples demonstrates a

lack of di erentiation between human and non-

human life, since both stem from humanity as

their original condition. They view animals as

possessing human sociocultural inner aspects

that have been “disguised” by external bestial

forms. This is a divergence from the other

ethnographies explored in this essay and

further asserts the range of possibilities under

the umbrella of animism. What consistently

runs through these accounts of new animism is

the importance of relatedness.

Expanding the Western Mind

Earlier I mentioned the possibilities of using

relational epistemology in a Western context

as a means of cultivating pro-environmental

attitudes. The Western mind’s loss of relational

connections with nature incites su ering

for both camps. Hogan (2013) suggests that

we need animists to address the detrimental

issues of climate change, though the irony of

institutions teaching animism where they

previously shunned it as “primitive” is not lost

on her. Despite this, she seems optimistic in

animism’s ability to positively impact the whole

living world, particularly non-human animals:

“the future of the animals is for the new young

animists to determine” (2013, 25). It is not my

goal to suggest that all people should practice

animism. However, what may be possible is the

respectful borrowing of some core principles of

animism, such as those discussed in this essay.

Additionally, there are clear parallels between

the non-dualism found within new animism

and relational epistemology to ecopsychology,

since ecopsychology questions the distinction

between the body and the other (Hillman,

1995). As in animistic cultures, principles of

ecopsychology are enacted from birth. Davis

(2012) highlights the importance of beliefs and

actions in determining the ecological footprint

of a culture. If, as a child, one is directed towards

a respectful relationship with the mountain,

one is more likely to behave di erently than

the child who is not a orded the same beliefs.

58

Reinders (2017) believes that we share an

ancient kinship of embodied being with all

lifeforms and that it is the awareness of our

interaction and connectedness with the earth

and the entire cosmos that defines us as human.

It has been the case, however, that centuries of

unmitigated capitalist technological expansion

have reinforced the duality between human

and nature via egocentric and anthropocentric

worldviews. Reinders continues that an eco-

centric consciousness can marry scientific

thought to a capacity to love, and rational

understanding to empathy and intuition. Her

notion of the body being the “topsoil” in which

the eco-centric consciousness may take root

and develop paints a clever metaphor that

resonates with relational epistemology and the

dismantling of human/non-human barriers.

Through our lived body as a sensory vessel

we may experience empathic relations with

nature: “alive in all our senses, we may begin to

listen to the ancient dialogue of body and earth”

(2017, 17). Reinders’ emotive language is one

example of how ecopsychology aims to address

the underlying philosophical limitations of

capitalist-driven societies. Just as we seek the

help of psychologists to work through traumas,

so we might turn to principles in ecopsychology

to work through the trauma that exists between

human and non-human.

Conclusion

From its roots as a misguided and derogatory

concept to contemporary contextualisation,

animism continues to provide cultural

anthropology with a useful tool of ethnographic

enquiry. The literature shows variation in

animistic conventions throughout traditional

peoples in di erent societies. However, a

constant theme of relational epistemology

persists in almost all of them. This distinction

is not only important in understanding

di erences between traditional cultures but

also for recognising limitations to the Western

capitalist-driven, utilitarian ontology that

has resulted in continued environmental

devaluation and degradation. Acknowledging

these aws presents the potential to reconnect

a sensual relation with the earth that

suppresses, or even destroys, the Cartesian

duality of human and non-human.

works cited

Bird-David, Nurit. “’Animism Revisited’:

Personhood, Environment, and Relational

Epistemology.” Current Anthropolo y 40, no.

s1 (1999): S67-S91. http://www.jstor.org/

stable/10.1086/200061

Davis, Wade. “Sacred Geography.” In

E opsy holo y: S ien e, Totems, and the

Te hnolo i al Spe ies, edited by

Peter H. Kahn & Patricia H. Hasbach, 285-308.

New York: MIT Press, 2012.

Descola, Philippe. Beyond Nature and Culture.

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Harvey, Graham. he Hand ook o Contemporary

Animism. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Hillman, James. “A Psyche the Size of the Earth:

A Psychological Foreword.” In E opsy holo y:

Restorin the Earth, Healin the Mind, edited

by Theodore Roszak, Marey E. Gomes & Allen

D. Kanner, xvii-xxiii. Los Angeles: Sierra Club

Books, 1995.

Hogan, Linda. “We call it tradition.” In he

Hand ook o Contemporary Animism, edited by

Graham Harvey, 30-44. New York: Routledge,

2013.

Malville, J. Mc Kim. “Animism, Reciprocity and

Entanglement.” Mediterranean Ar haeolo y and

Ar haeometry 16, no. 4 Special Issue (2016): 51–

58. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.220898.

Naveh, Danny & Bird-David, Nurit. “Animism,

conservation and immediacy.” In he Hand ook

o Contemporary Animism, edited by Graham

Harvey, 27-37. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Reinders, Sophia. “The Sensuous Kinship of

Body and Earth.” E opsy holo y 9, no. 1 (2017):

15-18. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/

eco.2016.0035.

59