Surfing communities and their potential for

grassroots environmentalism

A comparison of Ukraine and Germany

Oksana Dmytriak

Isabelle van der Graaf

Pia Luisa Reker

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and

Organisation

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability

(OL646E), 15 credits

Spring 2019

Supervisor: Jonas Lundsten

1

June 2019

Malmo, Sweden

Malmö University, Department of Urban Studies

Master’s programme in Leadership for Sustainability

Researchers: Oksana Dmytriak, Isabelle van der Graaf, Pia Luisa Reker

Supervisor: Jonas Lundsten

Title: Surfing communities and their potential for grassroots environmentalism. A comparison

of Ukraine and Germany

1

1

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the participants of the study who took the

time to provide us with insights about their connection to nature and structures of their surfing

communities. We acknowledge that otherwise we would have had no access to these understandings.

We truly appreciate your inputs, spirit and constant inspiration shared through the interviews.

Also, we are particularly grateful to Malmš Stadbiblioteket for being our productive oasis and

pleasant working space. We want to thank the staff of the Library CafŽ for recognizing us as regulars

by securing coffee supply in times, when it was needed.

Many thanks go to our classmates for their curiosity about the topic of this paper, for their

support and occasional distraction. Moreover, we want to thank Jonas Lundsten for appreciated

feedback and shared calmness throughout the weeks of diving deep into ecopsychology and various

other theories, that crossed our path. We are thankful for the process and cherish the knowledge we

gained.

Lastly, we want to thank Jonas and Seve for taking the time to advise our trio on academic

validity and express special thanks to Kathi and Maya for supplying us with spiced and wholesome

carbohydrates, in the final period of writing.

Abstract

This research paper aims to study the lack of local grassroots initiatives in surfing communities by

comparing Ukrainian and German contexts. Hence, a qualitative and inductive approach is used. The

scope of the research question is explored, by analysing the effects of individual motivators and societal

factors needed for GRI formation in active and connected surfing communities. It is further analysed

how these motivators are developed and influenced in Germany and Ukraine taking the theories of

ecopsychology, social learning and social capital as the framework and analytical lens. Key findings

highlight a certain degree of potential for Ukrainian GRIs in surfing communities, while an intense

amount of limiting factors is found. Moreover, the chosen comparative context of Ukraine and Germany

reveals relevant findings from the collected data, that reveals a low level of trust towards the

governments and a low self-efficacy level in Ukraine, while a high level of trust and high self-efficacy

was observed in Germany. The research provides relevant insights about the increasing popularity of

surfing as a sport, niche, and potential social movement towards environmental activism and sustainable

development.

Key words: grassroots initiatives, GRIs, environmental activism, environmentalism, surfing

movements, surfing communities, ecopsychology, social learning, social capital, Ukraine, Germany,

EU

1

Table of Contents

Table of Abbreviations

1

1. Introduction

1

1.1 Context

2

1.1.1 Sustainable development

2

1.1.2 Environmental local activism

2

1.1.3 Grassroots initiatives

3

1.1.4 Active and connected surfing grassroots movements

4

1.2 Impact of surfing foundations on environment

4

1.2.1 Europe: Surfing initiatives

5

1.2.2 Germany: The country, their environmental attitude and surfing movement 5

1.2.3 Ukraine: The country, their environmental attitude and surfing movement

6

2. Previous research

8

2.1 Research problem

8

2.2 Purpose

9

2.3 Research questions

9

2.4 Structure

9

3. Theoretical framework

9

3.1 Model for social change through grassroots initiatives

10

3.2 Social Learning

10

3.3 Social Capital

12

3.4 Ecopsychology

13

4. Methodology

17

4.1 Research design

17

4.2 Collecting data

18

4.3 Data analysis

19

4.4 Research reliability and validity

20

4.5 Research limitations

20

5. Analysis

21

5.1. Antecedent findings

21

5.2. Social Learning

23

5.3 Social Capital

24

5.4 Ecopsychology

25

5.5 Ukraine: Political context

26

5.6 Themes

27

5.6.1 Trust (societal level)

28

5.6.2 Self-efficacy (individual perspective)

28

6. Discussion

30

7. Conclusion

33

Pages after the conclusion may have another type of numbering such as: i, ii, iii...

34

References

35

Appendix

43

Interview Questions

43

Consent Forms

47

2

1

Table of Abbreviation

EJM

EU

EWWR

GDP

GRI

IOSF

NGO

SC

SDG

SGMAP

SL

SLE

UN

UNDP

USC

USF

Environmental Justice Move

European Union

European Week for Waste Reduction

Gross Domestic Product

Grassroots Inititative

Internationally operating surfing foundation

Non-governmental organisation

Social Capital

Sustainable Development Goal

Surfer grassroot movement against pollution

Social Learning

Significant Life Experiences

United Nations

United Nations Development Programme

Ukrainian Surfing Community

Ukrainian Surfing Federatio

1

1. Introduction

Grassroots initiatives (GRIs) emerge as networks of activists and organizations generating

novel bottom-up solutions for sustainable development. Lately, they have been growing and obtaining

a lot of attention, tackling global environmental issues through activism (Feola, 2013; Seyfang & Smith,

2007; Leach et al., 2012). Global environmental issues refer to harmful effects of human activity on

ecosystems, biodiversity and natural resources causing global warming, environmental degradation

(such as ocean acidification) and biodiversity loss. These environmental challenges have been

recognized and therefore, sustainable development was coined by the United Nations General Assembly

in 1987 (UN, 1987). The sustainable development goals (SDGs) were launched in 2015 in order to

amongst others, fight climate change (SDG 13) and maintain sustainable cities and communities (SDG

11).

GRIs play an important role when addressing these challenges as, in contrast to mainstream

business, they fight climate change and strive for sustainable cities in different and innovative solutions

(Grabs et al., 2015; Seyfang & Smith, 2007). As role models for societal change, GRIs are mainly

focused on organizing at a local community level with a structure that aims to work on a high degree of

participatory decision-making and flat hierarchies (Grabs et al., 2015). Their successful achievements

were defined in previous research along the lines of social connectivity, empowerment, and external

environmental impact (Feola & Nunes, 2013).

Research also suggests that a lifestyle sport, such as surfing, can be considered not only a sport

but a cultural space concerned with the social movement of environmentalism (Wheaton, 2007).

Wheaton (2007) reveals that participants of hedonistic, individualistic, minority sports cultures are

exposed to and directly involved with environmentalism. Even though bodily pleasure is the apparent

intercommunity, these cultural spaces bear the potential for political activism (Wheaton, 2007).

Laviolette (2006) approves that surfing creates interconnectivity of humans and nature. Interestingly,

the theory of ÔecopsychologyÕ defined that the closer the human connection to nature is, the stronger

the desire for taking care of the environment and contributing to more sustainable practices will be

(Brymer, Downey & Gray, 2009).

Thus, this research study focuses on grassroots initiatives around surfing and their potential to

influence environmental activism and foster communication towards more sustainable development in

Ukraine. To better understand the context, the following sections will provide an introduction to the

topic. Hence, GRIs will be explained and European surfing communities, especially the German context

will be characterised to lay the foundation for a comparison with the Ukrainian surfing community.

Magnani and Osti (2016) explain that the German surfing community and context was chosen due to

the strong GRIs networks in northern Europe. The engagement of civil society in social movements is

essential. Hence, Germany is a relevant country to look at.

The countryÕs legal framework for GRIs favors the development of such and generally the

political will to support is found. Moreover, Western- and Northern European countries seem to have a

higher overall GDP per capita (income), than Southern- and Eastern European nations. Therefore, the

stronger middle class in Western and Northern Europe has more resources to utilize for the formation

of social movements (Magnani & Osti, 2016). Kern (2019) states that since the Rio Earth Summit in

1992 and the Paris Agreement in 20151 awareness was raised about the responsibility of cities and

municipalities to bring sustainable change. As this research shows, Germany among other countries like

1 The Paris Agreement describes the get together of 195 countries in 2015 that were willing to

understand and face climate change by developing a global agreement that is nationally fair and

globally adaptable (Klein, Carazo, Doelle, Bulmer & Higham, 2017).

1

the Netherlands and Sweden, are the leaders in Europe, when it comes to voluntary implementations of

significantly sustainable practices, that often exceed the aims of the EU and member states (Kern, 2019).

When a municipality acts as a Ôgreen cityÕ, and therefore as a leader for other places, communities and

citizens, the latter ones get inspired and empowered to become active on individual levels. Thus, the

total sum of these factors favours the formation of GRIs in Western and Northern European countries

(Magnani & Osti, 2016; Kern, 2019).

Thus, Germany and Ukraine are divergent, yet both countries show surfing movements.

Therefore, two countries, one EU member and one non-EU member, will be compared. The different

political and industrial circumstances will be taken into consideration as well as societal factors when

surfing communities and movements are compared and examined.

1.1 Context

The following paragraph enlightens the key terms used in the thesis, which are Ôsustainable

developmentÕ, Ôenvironmental local activismÕ, ÔGRIsÕ and Ôactive and connected surfing grassroots

movementsÓ. These terms are part of the research question, as well as important for contextualizing the

previous research, as well as for the findings from the interviews.

1.1.1 Sustainable development

The concept of sustainable development was interpreted by the Brundtland Commission to link

the issues of economic and environmental stability. Sustainable development was defined as the

Òdevelopment that meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations

to meet their own needsÓ (United Nations General Assembly, 1987). In 2015, the agenda for Sustainable

Development and its 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) were formed with the idea to transform

the world by ending poverty, inequalities and tackle climate change by 2030. This agenda calls for the

action, commitment and collaboration of stakeholders around the world.

1.1.2 Environmental local activism

An environmental movement emerged in the 19th century around preservation and

conservation. Preservation describes the aim to keep nature undisturbed and apart from industry and

humanity. Conservation is concerned with the sustainable use of natural resources for future

generations. These trends reacted to early stages of capitalism. These approaches clarify the perceptions

of humans dominating nature, in this time referred to the industrialization and its effect of the

environment in the first place. While the 1960s brought a new era of environmental activism, the early

approaches of preservation and conservation are still part of the common strategies. When further

industrialization and urbanization took place, the effects on nature increased and as a consequence

knowledge about the effects of environmental disruption on human health (Mihaylov & Perkins, 2015).

In a middle-class setting, where social movements were supported and social change requested the new

environmentalism arose by questioning economic growth and demanding a Ôgreener lifestyleÕ and

independence from governmental control. These times brought forth Ôgreen politicsÕ and introduced

environmental concerns into the political context, especially in Europe. The relationship between

humans and nature changed and the approach to generations passing the world on like they received it

arose. In addition to it the 1970s and 1980s continued the bottom-up-approach in the ÔEnvironmental

Justice MoveÕ (EJM). The EJM arose in a time, when economic growth increased and societal

inequalities intensified Mihaylov & Perkins (2015) explain. The EJM aimed to include the less powerful

and formerly discriminated into the movement. Communities had learnt from the civil rights movement

and adapted their experiences to then fighting for clean water, air and food. The strong connection of

2

social justice and environmental activism describes the interconnection of first, protecting the

environment to protect marginalized communities that suffer most from environmental harm and

second, fighting for social justice helps the environment, because societies are less excluded and the

enforcement of environmental protection can be easier implemented. The importance of local initiatives

became clearer, because especially marginalized communities stay within the spatial borders of their

communities, not only for work, learning and residing, but also for leisure activities. The audiences of

the environmental movement have included the white middle-class and marginalized communities

which over the years acknowledged the importance of local involvement and activism. In the 1990s and

2000s a drastic increase in local GRIs took place. The localization of environmental activism evolved.

These GRIs are part of humansÕ everyday life and interpersonal networks, which react to the immediate

threats of environmental harm (Mihaylov & Perkins, 2015).

Moreover, the interaction between locals and their environment is rooted in two perspectives

on the place, that is desired to be protected. The ÔplaceÕ is described in a material, as well as socially

constructed dimension. Places are referred to as locations where people work, live, and form social

relationships and attachments. Therefore, local GRIs movements get strengthened by localsÕ connection

and proximity to the e.g. threatened ecosystem or site (Mihaylov & Perkins, 2015).

1.1.3 Grassroots initiatives

GRIs are organizations with innovative bottom-up approaches for sustainable development

(Grabs et al., 2015; Seyfang & Smith, 2007). They stimulate collective actions characterized by a

greener business activity role model where sustainable innovation with a focus on Social Learning (SL)

is ascendant. They emphasize different social, ethical and cultural rules and their spectrum of

organisations exhibit varying degrees of professionalisation, funding and official recognition. The

motives of the activists who initiated the movement are normally driven by social need and ideology

(Seyfang & Smith, 2007). Grassroots then, involve committed activists and innovative solutions for

sustainable development that respond to the local situation and the interests and values of the engaged

communities (Seyfang & Smith, 2007).

Seyfang and Smith (2007) further explain, that GRIs offer potential for individual advantages,

development and diffusion opportunities. The individual advantages include job creation, training, skill

development, personal growth in relation to self-esteem or confidence, a sense of community, social

capital, improved access to services, health improvements and greater civic engagement. Advantages

for diffusion that are accrued by GRIs are awareness-raising, education, promotion, altering mindsets

of local policy-makers and politicians, inspiring people to implement more sustainable ways of acting

and thinking in their everyday life, supporting sustainable development, fighting for empowerment,

confidence and built the capacity for community-based actions and activism.

GRIs are functional for various of the processes of niche development (Ornetzeder &

Rohracher, 2013; Seyfang & Smith, 2007; Seyfang & Haxeltine, 2012). A Ôstrategic nicheÕ is defined

as a protected space where experiments can develop away from regime selection pressures and it is

formed by intermediary organisations and actors, which serve as Ôglobal carriersÕ of best practice,

standards, institutionalized learning, and other intermediating resources such as networking and

lobbying which are informed by, and in turn inform, concrete local projects (Kemp, Schot, & Hoogma,

1998). Three key processes for successful niche growth and emergence are recognized: managing

expectations, building social networks and learning. Expectation management concerns how niches

present themselves to external audiences and whether they live up to the promises they make about

performance and effectiveness. To best support niche emergence, expectations should be widely shared,

specific, realistic and achievable. Networking activities are claimed to best support niches when they

embrace many different stakeholders, who can call on resources from their organisations to support the

3

nicheÕs growth. Learning processes are estimated to be most effective when they contribute not only to

everyday knowledge and expertise but also to Ôsecond-order learningÕ wherein people question the

assumptions and constraints of regime systems. GRIs may be functional in terms of network formation,

learning and competence building but also in shielding, nurturing or empowering niche innovations

(Ornetzeder & Rohracher, 2013). Conversely, the niche can play an active role in interacting with the

context and thus contribute to shaping the conditions for GRIs success or failures (Feola & Nunes,

2013). Many positive accounts of specific grassroots initiatives have been provided and often seen as

niches of experimentation of new social, cultural, economic or technological arrangements (Seyfang &

Haxeltine, 2012; Seyfang & Smith, 2007).

1.1.4 Active and connected surfing grassroots movements

Active and connected surfing grassroots movements in this context mean the representatives of

those communities constantly involved in surfing as a sport or leisure time activity in different locations:

Odessa and Chernomorka in Ukraine and other popular and visited surfing places all over the world

(e.g. Portugal, Sri-Lanka, Bali etc.). The surfing community is connected in a way that surfers do not

necessarily live at the coastline, but live in Ukraine, and they are the part of the surfing group (despite

the fact itÕs formalized or not) and have to travel to the coast in order to practice surfing (ÒFirst surfing

championship in OdessaÓ, 2018).

However, several studies (Brymer & Gray, 2009; Olsen, 2001; Uhlik, 2006) explore the deeper

connection and relationship between extreme sports participants and nature, that can lead to different

repercussions (starting from stronger care and leading to environmental activism) according to the

theory of ecopsychology (Brymer & Gray, 2009). Those who participate in extreme sports consider the

concept of fighting or conquering the environment a misunderstanding. A Study by Brymer & Gray

(2009) shows that participants of extreme sports accept that they cannot control the environment and

that they are powerless compared with the natural world. Participants of extreme sports deny any

attempt to control natural forces. They are in the natural world and, to participate successfully, must

learn to understand their limitations and adapt (Brymer & Gray, 2009).

Furthermore, active and connected surfing has more potential to become a strong GRI towards

environmental activism, as according to the principles of ecopsychology people who had formative

experience with nature from early childhood and had role models who took care of it were led by their

example are more prone to have a better interconnections with the natural world that is being expressed

in a care of it (Gibson, 2000; Chawla, 2007; Arnold, 2009).

1.2 Impact of surfing foundations on environment

Multiple movements and organizations around surfing for the protection of beaches, reduction

of plastic waste in the ocean and adaptation of ocean-policies arose within the last decades. An

internationally operating surfing foundation (IOSF), a NGO, was founded in 1990 in the United States

and brings together local communities (volunteers), coastal defender and national experts in law, policy

and science to produce victories, change laws, educate and share knowledge on protecting beaches and

oceans. Therefore, the introduced IOSF is a valuable example of activistic engagement, since its impact

is measurably successful (ÒA European Network of VolunteersÓ, 2019; ÒOur oceans, waves, and

beaches are everythingÓ, 2019). Another movement that gathered in the late 1990s is named the local

surfer grassroot movement against pollution (SGMAP). The surfers demonstrated how through sports

consumption, participants from a range of minority water sport cultures have formed a political trans-

local collectively based around a concern with their own localised environment, one which has become

articulated into broader political issues (Parris, Shapiro, Welty Peachey, Bowers, & Bouchet, 2015).

4

Apart from the focus of the thesis on local surfing communities, the authors acknowledge the

fact that the internationality of surfing leads to extensive air travel, which is one of the worst activities

from an environmental point of view. Nevertheless, the thesis focuses on the local groups as a driver

for environmentalism and is therefore distanced from the harmful travelling.

1.2.1 Europe: Surfing initiatives

A European surfing foundation was founded shortly after the American core foundation around

the year 1990 (German Interviewee 1). Today, local chapters of the IOSF are found in over 14 European

countries, run by volunteers (ÒA European Network of VolunteersÓ, 2019). Thousands of volunteers

operate to promote the foundationÕs mission, run local campaigns, raise awareness, organise events,

develop partnerships and improve the volunteer network (ÒA European Network of VolunteersÓ, 2019).

Thus, the impact of these surfing foundations and their members is considerable. Moreover, surfing is

a leisure activity that has gained more popularity within the last years. Hence, the surfing communities

in Europe and the interest in environmental protection grew (ÒA European Network of VolunteersÓ,

2019).

Not actually nudged by surfing initiatives but aligned with their visions is the following political

trend: the preservation of the ocean as a thematic priority in political partiesÕ programs, which was

analysed and published by the IOSF of Europe (ÒEuropean ElectionÓ, May 24, 2019). The observation

shows that Germany ranks highest with 11 parties that focus on preserving the environment and ocean

from threats such as pollution, biodiversity, sea transport and climate change. The IOSF stresses the

importance of acting Ôagainst the economical and industrial interestsÕ (ÒEuropean ElectionÓ, May 24,

2019).

1.2.2 Germany: The country, their environmental attitude and surfing movement

A multitude of surfing organisations, formed to various extents, are found in Germany. There

are surf clubs, that focus on the sport and performance, NGOs, that activate within the surfing

communities for charitable matters and above, local chapter of IOSF.

More than one local chapter of an IOSF were formed in Germany. These chapters are located

in Hamburg, Berlin and on Fehmarn. The multitude of local chapters shows great awareness for the

protection of the ocean, beaches and the environment in general among involved volunteers. The first

chapter was formed in Hamburg, followed by Berlin and Fehmarn (German Interviewee 1). The local

chapters work through volunteers. The IOSF in Germany supported the political engagement to adopt

measures for maritime transport to retain the commitment of the Paris Agreement to keep the global

temperature rise below 2¡C, which proved to be successful (ÒAnnual Report #17Ó, 2017). Moreover,

they took part in the European Week for Waste Reduction2 (EWWR) which takes place once a year

since 2012 (ÒIdeas for ActionsÓ, 2019). Awareness was raised by volunteers that reached out to up to

100 stores in Northern Germany to educate about the effect of plastic bags on the environment (Assenjo

& Sico, 2017).

A present image of Germany portraits the country as the Ôglobal environmental leaderÕ

(Schreurs, 2016; Knill, Heichel, & Arndt, 2012). It is often stated, that the country has one of the most

active and institutionalized Green movements in the world. Studies from 2016 show that 10 percent of

Germans are part of an environmental, nature protection, or animal rights group and thereby, more

active than other nations (Schreurs, 2016). Hence, GRIs exist in many places in Germany. Whole

2 EWWR takes place annually all over Europe. The EWWR aims to educate about sustainable

resource and waste management by promoting the 3 Rs, that are reduce, reuse, recycle (“Ideas for

ActionsÓ, 2019).

5

communities collectively compete against each other to be more sustainable or more organic than other

towns. Some compete for who is using more renewable energy solutions. Moreover, Germans rank high

in European comparison with their recycling performances (Schreurs, 2016).

Germany is EuropeÕs largest economy and accounts for over 20 percent of the European

UnionÕs (EU) Gross Domestic Product (GDP). It is the largest country by citizen. Therefore, the country

has a noticeable voice in Brussels EU Parliament. Concerning the European climate goals, Germany

advocated for the establishment of a significant reduction in CO2 emissions, development and support

for renewable energy and the ambition to improve energy efficiency by 2020 (Schreurs, 2016). A

driving force in these developments were GRIs. Nevertheless, the country still quarries the natural non-

renewable resource brown coal, which is not environmentally friendly, and is responsible for the largest

amount of greenhouse gases emitted in Europe (Schreurs, 2016). On top of that the automobile industry

is very strong in Germany. Approximately one percent Germans is employed in this field and 18 percent

of the worldwide produced cars origin in Germany (Schreurs, 2016).

What this all amounts to is that Germans show an awareness for planetÕs scarce resources and

the need for environmental protection. Hence, a network of GRIs is present and active. Nevertheless,

industries and politicians often chose the short-term solution and sacrificed environmentalism, even

though political attempts are visible. Though, in comparison to other European countries, Germany

ranks as a leader in the political and Ôgreen-economicalÕ context (Schreurs, 2016; Knill et al., 2012).

1.2.3 Ukraine: The country, their environmental attitude and surfing movement

Ukraine as a surfing destination in Eastern Europe is developing. Hence, the south coast of the

country (Odessa) and its Black Sea coastline have great potential for the surfing activity to be

developed: The Ukrainian Surfing Federation (USF) was created in summer 2018, registered as a non-

governmental organisation (NGO) and has already held one competition among surfers in September

2018 in Odessa (ÒFirst surfing championship in OdessaÓ, 20183). Moreover, a Ukrainian surfing

community (USC) has great popularity in the country as it popularized surfing practices as a leisure

activity and increases tourism. Moreover, the USC organises surfing trips to different continents, which

are accessible for Ukrainian surfers with different skill-levels (ÒHi, itÕs us!Ó, 2019). Natural conditions

allow surfing in Odessa mostly in autumn and winter, which can be too demanding for the leisure

activity in beginnerÕs perspective, but despite the fact that surfing conditions in Ukraine can be difficult

for beginners, the surfing community in the country grows each year (ÒSurfing in Odessa:Ó, 2016). The

USC can be defined as passionate surfing individuals who surf at local beaches (e.g. Odessa,

Chernomorka) as well as abroad in countries such as Portugal, Spain and Sri-Lanka (ÒSurfing in

Odessa:Ó, 2016).

Observing the situation of Ukraine at the moment, due to Euromaidan events, it seems that the

country represents a good platform for grassroots initiatives that have the potential to learn about a

sustainability transition. Several studies suggest that grassroots initiatives in Ukraine were influenced

by an important social protest - Euromaidan (2013-2014) and affected participantsÕ perception of taking

an action, building community and reflect (Udovyk, 2016; 2017). The protestÕs label ÔMaidanÕ

originates from the common abbreviation for ÔMaidan NezalezhnostiÕ (Independence Square) the main

plaza in UkraineÕs Capital Kyiv. Geographically the plaza is not located within an area of political

decision-making. However, historically, the plaza is known for the ÔOctober RevolutionÕ during soviet

times and is ever since known for a place for political expression (Yekelchyk, 2015). Multiple protests

3 Hardly any comprehensive scientific studies exist about the surfing community in Ukraine, therefore

non-scientific sources are gathered.

6

have been held at the ÔMaidanÕ throughout the years, which made the square internationally known to

be a symbol for Ôpopular democracyÕ (Yekelchyk, 2015). Recently, from 2013 to 2014, Ukrainian GRI

participants strengthened their senses of solidarity and responsibility through the experience of

Euromaidan and were led to the active participation of further development of similar initiatives

(Udovyk, 2016), which makes Ukraine a strong platform for further development of GRIs. In 2013

protests were initiated and GRIs were formed after the Ukrainian government resigned from the

ÔAssociation AgreementÕ with the EU, which was supposed to stabilize political and economic relations,

secure equal rights for workers and build a step towards visa-free traveling of Ukrainians (Yekelchyk,

2015). Hence, the dissatisfaction of Ukrainians was immense, GRIs were formed and consequently, the

government changed and was revoted (Yekelchyk, 2015). Therefore, the self-confidence for the

possible effect of GRIs was increased (Udovyk, 2016).

Moreover, according to a United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) environmental

survey, the Black Sea has twice as much floating plastic as any other sea in Europe (UN Environment,

2018). According to the results of Simeonova (2019) marine litter monitoring along the coast of the

Black Sea is most polluted by artificial polymer materials (plastic cups, lids of beverages, synthetic

polymer items). Today, the Black Sea has one of the highest indicators of single-use plastic items -

68%, in comparison with the Mediterranean Sea - 13%, NE Atlantic - 12% and Baltic Sea - 7%.

Generally, the report concludes that single-use plastic items (e.g. plastic cups and drink bottles) were

typical mostly from the Bulgarian Black Sea coast and were not found on the shoreline of the rest marine

regions in those amounts yet, which can mean that they were probably replaced by another type of

material (Simeonova, 2019). The repercussions of plastic pollution at the seashore are obvious which

highlights the need for an influential and active community to locally tackle the problem.

According to the latest report on climate change in the context of the Paris Agreement

commitments and challenges in cooperation between Ukraine and EU, it is stressed that no framework

law has been adopted in Ukraine on the prevention of- and adaptation to climate change, and there are

problems with integrating climate policy in various spheres. Low institutional capacity and human

resource potential are mentioned as obstacles for policy implementation (Turchenko, Viriovkina,

Tselocalchenko, Zakrevska, & Bondarenko, 2017). Moreover, the role of local governments is indicated

as a strong obstacle when achieving climate targets (Turchenko et. al, 2017).

It has been also stressed that special attention should be paid to the adaptation to the effects of

climate change. Important for Ukraine this regard is the relationship between water resources

management and climate change: the probability of a future lack in potable water resulting from climate

change needs to be taken into account, and a policy developed to address these adverse effects

(Turchenko et. al, 2017). Moreover, it is emphasized on the importance of raising awareness among the

population that should be better informed of the implementation of environmental legislation and

Ukraine's environmental commitments to greening the economy, energy savings, climate change

prevention and adaptation to climate change (Turchenko et. al, 2017).

Surfing has a great potential in Ukraine, not only as a leisure activity but also as a professional

sport. The fact that Ukraine did not become a part of European Union and is still on its way of

development and meeting the requirements of the EU, may have influenced the climate regulations,

policies and the attitude of authorities towards the adaptation to climate change. Moreover, UkraineÕs

Industry is renowned to be one of the worldÕs largest producer of steel, cast iron, pipes and mineral

fertilizers. Pre-influenced by the Soviet Union, Ukraine still ranks as a relevant player in the military

industry (Yekelchyk, 2015). The Ukrainian industry, hence, consists of heavy and ÔdirtyÕ fields, with

no prominent trend towards climate-friendlier alternatives, yet (Yekelchyk, 2015). Moreover, the

Ukrainian country still struggles with the law framework of the climate regulations and proper

7

awareness among the population (Turchenko et. al, 2017) by covering this issues with more important

social, political and military matters.

2. Previous research

Different authors emphasized the importance of having local grassroots instead of globalized

environmentalism due to the significance of local knowledge and scale, direct exposure to nature, place

attachment and its disruption, and place-based power inequalities (Mihaylov & Perkins, 2015; Seyfang

& Smith, 2007; Seyfang & Haxeltine, 2012). Previous environmental initiatives in situations of an

uneven status of power have been demonstrated to be successful and started to replace governments in

the quest for environmental sustainability (Guerr—n-Montero, 2005). Further, research shows that

societies are less likely to wait for political unions and parties to act and would rather proactively

approach problems themselves (Kj¿lsr¿d, 2013). Research also investigated why grassroots initiatives

were created and developed successfully by focusing on the processes of funding, engaging, developing

and maintaining grassroots initiatives (Grabs et al., 2015). They presented theoretical and empirical

evidence connecting a broad spectrum of concepts, as Social Capital (SC) and Social Learning (SL),

that can be used as testable factors for in-depth investigations of grassroots motivators which will be

used in the thesis. Furthermore, ecopsychological studies suggest that under the circumstances a person

had access and mobility to explore the natural world (Chawla, 2007), had a strong role model (parents,

caregivers or peers) who protected or were knowledgeable about the environment and lived through

significant life experience with the nature (Arnold, 2009), this individual is more prone to be influenced

in a positive way for environmental care. There is no direct proof that only people with mentioned

experiences can become strong environmental leaders, but ecopsychology evidences that mentioned

factors influence general interconnections with the natural world and forms the personality (Chawla

1998; 2007; Sivek, 2002; Arnold, 2009), which can create a perpetuate loop of sharing environmental

competences with others and be a base for environmental activism.

2.1 Research problem

Different observations have been contemplated. First, it appears that grassroots movements

keep increasing globally due to their successful achievements (Feola & Nunes, 2014). Second, surfing

communities are increasing in popularity and more surfers are connected with nature, therefore they are

also more aware and concerned about the environmental damages caused by human actions and feel

more responsible to protect the environment (Laviolette, 2006). Third and contradictorily, it seems that

not every surfing community necessarily follows this line of thought. Ukraine will be analysed and

compared to Germany in this thesis, due to active surfing communities in both countries, which can be

examples of good platforms for GRIs with the potential to transform individuals into sustainable leaders.

Yet, there are scarce prominent indicators for change towards sustainable development and little visible

active environmental behaviour in especially Ukrainian surfing communities. There is thus a gap in

research regarding the motivators and influences needed at the individual and the societal level for

facilitating grassroots surfing initiatives which enable and empower environmental activism. In the

context of motivators that Grabs et al. (2015) described as necessary for successful grassroots initiatives,

certain factors at individual and societal level need to be considered and explored when interviewing

the individuals from the surfing communities in different contexts, as these motivators are the

preconditions for GRIs and can contribute to finding influences for the current gap in research upon

surfing communities and their potential for GRI environmentalism.

8

2.2 Purpose

The thesis aims to explore to what extent local surfing communities bear potential for

transforming into GRIs and act as sustainable leaders to bring change towards sustainable development

and environmental activism. This will mainly be performed by exploring the effects of individual

motivators and societal factors, needed for GRIs to form and develop in surfing communities. Ukraine

and Germany will be used as exemplary contexts.

2.3 Research questions

RQ 1: How is it that there is a lack of local grassroots initiatives in Ukrainian surfing

communities while they are present in the EU country Germany?

RQ 1.1: How does the relationship between individual and societal level influence local

GRIs?

RQ 1.2: What are the influences that bring about sustainable development and environmental

activism through active and connected surfing grassroots movements in EU countries such as

Germany?

2.4 Structure

This paper is organized into seven chapters with further subchapters. The first chapter provides

background information about the context of the paper. The second chapter presents the research

questions, the purpose of the study and previous research on the studied question. Chapter three gives

an overview of the relevant theoretical framework which was used in the paper. In the fourth chapter a

detailed methodological description for data collection is presented, this chapter describes also the data

analysis process and specifies research limitations. Chapter five is composed of the detailed analysis of

the collected data and is divided into subchapters according to the analytical process. The key findings

are summarized and discussed in chapter six. Lastly, a conclusion is formed in the last chapter of the

paper.

3. Theoretical framework

The following chapter introduces the theoretical framework of multiple concepts and theories

that the research paper is rooted in. Research suggests that the formation of GRIs, e.g. local chapter of

an IOSF, surfing associations are a fundamental progress and effective tool for sustainable development

and environmental activism (Feola & Nunes, 2014). Several factors influence the GRI to be a catalyst

for sustainable development and environmental activism (Grabs et al., 2015). Through the application

of the theoretical framework to the findings from the qualitative research, this research aims to identify

the motivators that might be lacking at individual and societal level for implementation of grassroots

initiatives in surfing communities in Ukraine. The chosen theoretical perspectives were Social Learning

(SL), Social Capital (SC) and Ecopsychology. SL studies behavioural change and GRIs will become

more generative contributing to efficient behavioural change through SL by bringing change in the

positions and commitments of different actors. As SC is used to study the interaction of individuals and

the thesis focuses on group movements, this theory was relevant to study the type of relationship

between different actors. Finally, ecopsychology was chosen as it emphasized the interconnections

between human and natural world as well as states that the closeness to the environment learnt through

9

the formative experience has a great impact on future relationship to nature and can lead to sustainable

development and consequently environmental activism.

3.1 Model for social change through grassroots initiatives

Based on the model from Grabs et al. (2015), GRI motivators can be framed in three different

levels: the individual, group-level and societal-level. GRIs can be represented in various forms and

tackle different problems, while they all provide a collective and social strategy for action and change.

As initiatives are driven by individuals engaged in the movement it is advisable to take the individual

level of GRI motivators into account. It is highlighted that the importance of comprehensibility, self-

efficacy, key experience, meaningfulness of change for individual as well as value systems or

worldviews, life quality as the starting point or motivator on an individual level. As GRIs are not only

individuals acting independently but are characterized as a group of people acting for a shared cause,

the model considers group-level characteristics. First and foremost, the legal status of the organisation

plays an important role in its image and further cooperation with other agencies and attraction of

volunteers. Strong organisational structures are of special importance for the initiatives that seek to

influence societal change as well as productive relationships with the government, funders, media and

other organisations are vital for small grassroots groups. As GRIs are managed by a group of people

their skills and the amount of time devoted to the development of the organization are vital too.

Moreover, the size and diversity of the steering group, trust between group members, density of the

internal network and the quality of internal communication are the factors mentioned by Grabs et al.

(2015) to motivate people to continuously develop the GRI organisation. Furthermore, the

organisational level includes motivators such as openness in process and goal-setting, so that the team

is led by a common goal and share expectations of the organisation that all members can identify with.

Lastly, even well organized and functioning groups might not achieve their stated goals unless

they are able to motivate collective learning and change at a societal level. This requires certain

structural and framework prerequisites. Societal-level GRI motivators should consist of regional or

national network, contacts to other stakeholders such as governmental agencies, private businesses, and

community representatives as they may further help the GRIs goals. GRIs also have to boost their

influence by offering broader-level policy recommendations to governmental actors. External

communication and the external impression by others through the focused public relations activities,

can even enable GRIs to stimulate change outside the traditional spheres of influence (Grabs et al.,

2015). Moreover, societal framework conditions for change have to include: political governance

support, under the circumstances that governmental objectives align with the grassroots initiativesÕ state

institutions which can then aid the cause by organising conferences, programs, or even special funding

for the group in question (Seyfang & Smith, 2007). One more motivator mentioned in the study is the

particular moment in time when GRI discovers societal conditions favourable for its success: a certain

window of opportunity (Grin et al., 2010), where due to particular events (such as crisis) given societal

arrangements become questionable and there is demand for alternatives which favours respective GRIs.

The levels are categorized and described according to the Grabs et al. (2015) model. Hence, this research

follows this specific categorization and focuses on the link between individual motivators of GRIs and

the societal level as it has great influence on GRIs development and success.

3.2 Social Learning

SL theory is based on the idea that people learn from interactions with others in a social context.

This theory has often been called a bridge between behaviourist learning theories and cognitive learning

theories because it demands attention, memory and motivation (Tadayon, 2012). Learning is defined

10

by Weinster & Mayer (1986) as the relatively permanent change in a personÕs knowledge or behaviour

due to experience. Bandura (1977) described SL as a learning process that individuals obtain by their

social interactions within a group. The theory explains that the individual can learn in different ways:

some patterns of behaviour are acquired by humans own direct experience, such as learning by doing,

or by observing at behaviours of others, so called observational learning. Bandura (1977) stressed the

importance of observational learning or modelling, where people observe their actions and outcomes

and on the basis of informative feedback they develop thoughts and hypotheses about the type of

behaviour that will be most successful. These thoughts and hypotheses will serve as guides for future

actions and are forceful (Bandura, 1977). There are four components involved in the process of

modelling. First, the observer must pay attention to events that are learned. Attention is determined by

variety of variables, including the power and attractiveness of the model as well as the conditions under

which behaviour is viewed. Second, it must be retained, with the observed behaviour represented in

memory through either an imaginal or a verbal representational system. Third, symbolic representation

now must be converted into appropriate actions similar to the originally modelled behaviour. To start

reproducing may involve skills the observer has not yet required. Lastly, the observational learning

process involves motivation as a variable. There must be, for instance, sufficient incentive to motivate

the performance of the modelled actions (Grusec, 1992).

Bandura also introduced self-efficacy as a context of an explanatory model of human behaviour

and how it will influence their actions in the face of overwhelming problems, defined as Ôbeliefs in their

capability to exercise some measure of control over their own functioning and over environmental

eventsÕ (Bandura, 2001). OneÕs perception of his/her capabilities and confidence of being able to

complete a concrete task, may not always be compatible with the actual accomplished skills and abilities

of this person. If the overestimation represents a slight discrepancy, then it can be considered a benefit

as it inspires people to go beyond their immediate reach and stimulate them to put more effort to excel

their usual performances (Bandura, 2001). However, the discrepancy between actual and perceived self-

efficacy should not be a gap, as according to Gage & Polatajko (1994) the inaccuracies in perception of

oneÕs performance, despite the fact they are too pessimistic or optimistic, may result in notable

repercussions. It is important to mention, that although perceived self-efficacy is a strong predictor of

behaviour, when capabilities are lacking, the desired performance cannot be achieved only based on the

expectations of the individual (Bandura, 1989). Additionally, Bandura finds that mastery experiences

are the most effective source for creation of efficacy perception and boosting efficacy level (Bandura,

1989). Mastery experiences can be previous experiences in a specific area in the form of knowledge,

practices, procedures or practical experiences with a concrete task that has been dealt with success and

therefore increased the sense of efficacy, which, according to Pearlmutter (1998) will influence oneÕs

efficacy for the next task to be performed successfully. It is found that beliefs of self-efficacy can

contribute to the motivational process and decisions for behavioural change. This is so, because such

beliefs affect the choice of action, how much effort will be put in it, how long people will persevere

when confronting obstacles and the type of goals that will be set (Wood, Bandura, & Bailey, 1990).

Pearlmutter (1998), finds that perceived self-efficacy influences oneÕs readiness to promote change, as

well as their level of motivation and commitment. The main implication is that if people believe they

can succeed in the performance of a task, they will become involved in the particular activity and will

behave with commitment, while if they think they cannot succeed, they will avoid the activity

(Pearlmutter, 1998).

Reed et al. (2010) argues that for a process to be considered SL, must have three characteristics.

First, a change in understanding has taken place in the individuals involved. Second, a process needs to

demonstrate that the change goes beyond the individuals and becomes situated within wider social units.

Third, change occurs through social interactions and processes between actors within a social network.

11

Social networks were traditionally linked between the micro and macro levels and have also been

demonstrating to have an influence on peopleÕs opinions and views. Changes in social networks might

be found through changes of rules, norms and power relations. Social interactions can be one-directional

(through information transmission) and multi-directional (in which the exchange of and deliberation

over different ideas and arguments change prior perceptions through persuasion. In alignment with

this, Gough et al. (2017) described it as Òprocesses by which society democratically adapts its core

institutions to cope with social and ecological change in ways that will optimise the collective well-

being of current and future generationsÓ.

3.3 Social Capital

ÔSocial capitalÕ (SC) is a sociological concept that stands for the source which facilitates social

movements as well as for the outcome of social movement activities (Edwards, 2013). Parris et al.

(2015) describe that when SC is created it creates value for the life within this particular community.

Thus, a social network is formed and trust is built. Paldam (2000) introduces the Ôtrust-cooperation

complexÕ which implies that SC stands for the quantity of trust that an individual has with other

individuals within their community and wider society (Paldam, 2000). Through this development both

individuals and the wider community benefit from a more supportive, trusting, and effective society

(Parris et al., 2015). Generally, SC describes peopleÕs ability to work with other people to achieve a

common goal in the structure of a voluntary organisation (Paldam, 2000). Although this form of

cooperation is actively chosen by individuals, an outside enforcement may also take place through third

party involvement, like governmental or institutional interest in social capital (Paldam, 2000).

Moreover, governments and institutions might passively support SC through a legal and political

environment that favours the social movement activities (Paldam, 2000). Furthermore, PutnamÕs

instrument is the density of voluntary organisations (Paldam, 2000).

Woolcock (2000) describes that the most fundamental agents for creating SC are a personÕs

relatives, friends and associates. Putnam (1993) agrees that Ôthick trustÕ develops in personal relations.

The same structure holds for groups. Communities with a diverse set of social networks and civic

associations are stronger and able to fight issues such as poverty and move forward quicker and more

agile (Woolcock, 2000). Therefore, SC describes the norms and networks that get people to act

collectively and voluntarily (Woolcock, 2000; Putnam, 1993). Putnam (1993) organised these three

resources as follows: first, trust and the supporting elements for development, second, the importance

of social norms and obligations and third, the presence of social networks and formation of voluntary

organisation (SiisiŠinen, 2000).

Putnam emphasized that SC is a collective quality produced and shared by members of a group.

Building on this, Flora and Fey (2004) examined community contexts and created a classification that

connects two aspects of social capital: bonding and bridging network for effective community action.

Bonding networks refer to strong connections among individuals and groups with similar background

while bridging networks refer to weaker connections among individuals and groups with different

backgrounds. Flora and Fey (2004) argue that communities with high levels of bonding and bridging

networks will be engaging in effective action while communities with low levels of bonding and

bridging networks suffer from individualism and find it difficult to engage in community action. The

communities with strong bonding, but weak bridging tend to have conflicts between separate insider

groups which are competing for control of decision-making. Communities with strong bridging but

weak bonding networks tend to leave too much control in de the hand of powerful outsiders. These

aspects of network themes can be helpful when locating communities on a continuum from weak to

strong in term of these two types of networks.

12

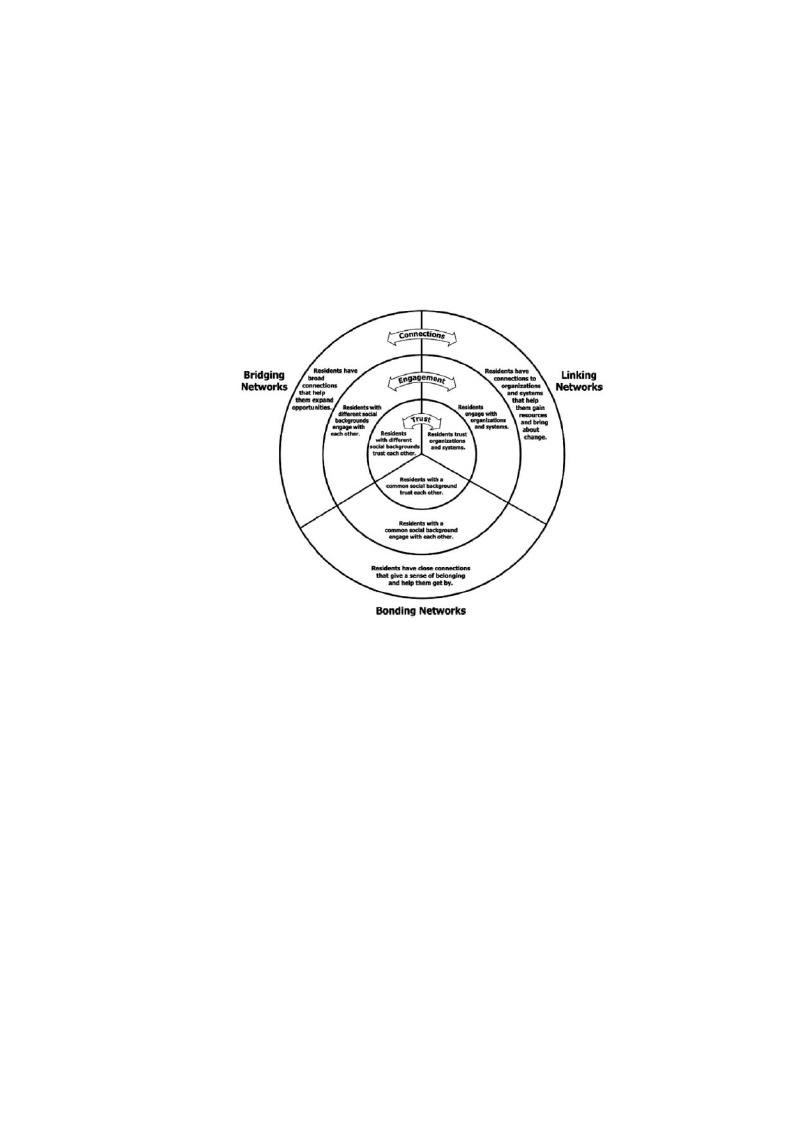

Figure 1 shows a community Social Capital Model developed by Chazdon and Lott (2010).

This focuses on how communities can improve their Social Capital by strengthening their residentsÕ

trust and engagement within three distinct networks: bonding, bridging and linking. Linking networks

are defined as networks and institutionalized relationships among unequal agents. Compared with

bridging, which connect individuals or groups who are not alike but more or less equal in terms of status

of power, linking networks are based as explicit vertical power differentials. These vertical connections

to organizations and systems help residents gain resources and bringing about change. Linking networks

is thus a third category of social capital to measure community strength.

Figure 1. Community social capital model (Chazdon & Lott, 2010).

3.4 Ecopsychology

ÔPsychology, so dedicated to awakening human consciousness, needs to wake itself up to one

of the most ancient human truths: we cannot be studied or cured apart from the planetÕ (James

Hillman).

Ecological psychology or ecopsychology Òfirst defined by Theodore RoszakÓ is a term for the

emerging synthesis of psychology and ecology (Hibbard, 2003). As a type of psychology, it seeks to

comprehend humankindÕs interrelationship with the natural nonhuman world, to diagnose what is

wrong with that interrelationship and to suggest paths to healing (Roszak, 1995). Ecopsychology grew

out of the environmental movement, which began in the 1960s in response to the dawning recognition

that modern industrial civilization had engendered an environmental crisis (Hibbard, 2003).

Studies suggest various definitions of ecological psychology: according to Winter (1996), it is

the study of human experience and behaviour in its physical, political and spiritual context in order to

build a sustainable world. Kinder (1994) defines ecopsychology as a study which explores how our

psyche is influenced by our environment as well as the environmental conditions influencing the way

we think and feel, treat nature and other creatures around us. According to Kindler, ÔEnvironmental

psychology is typically concerned with the effects of particular environmental conditions, such as stress,

13

pollution, noise, urbanization, crowding, and so forth, on individualsÕ (Kinder, 1994). By definition

ecopsychology aims to understand the ecological crisis from a psychological perspective (Hibbard,

2003). Taking into account all the mentioned definitions, ecopsychology aims to explore the

interrelations between human and nature relative to ecological crisis as it grew from it (Hibbard, 2003)

Scull (2008) discusses how actions towards nature need to be changed to overcome the existing

psychological alienation from the natural environment (Scull, 2008). Thus, ecopsychologists mention

that improving the relationship between human and nature happens on several levels (Hibbard, 2003;

Scull, 2008). One of those levels of ecopsychology is the experiential learning, that is assumed to help

humans arrange or rearrange their emotional and spiritual connection within their ecological system

(Scull, 2008). More precisely, experiential learning can already begin in early childhood as a significant

life experience that might continue, e.g. in wilderness experiences.

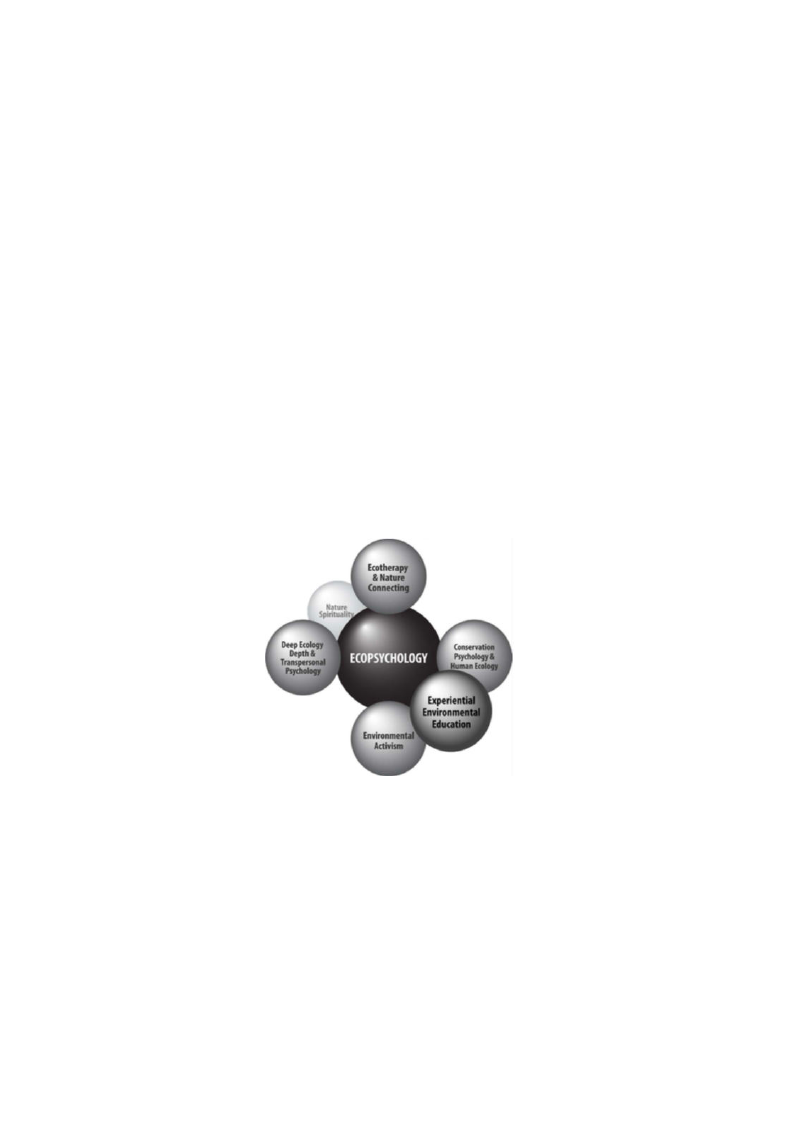

It is difficult to indicate a clear place of ecopsychology along other disciplines, as it has the

potential to break down barriers between many contrasting approaches to the human-nature relationship

and can be located at the intersection of three different dimensions, as illustrated in Figure 3. Indefinite

boundaries between ecopsychology and neighbouring disciplines appear.

To resume ecopsychology as a discipline, it has to be mentioned that it is a mixture of

experiential environmental education, natural history, and science. One can learn about nature and

ecology through attentive contact with the natural world (Scull, 2008). Building on a foundation of

direct experience with nature, ecopsychology is about formulating a language and set of models of the

human-nature relationship (Scull, 2008).

Figure 2. The position of ecopsychology in relation to other sub-disciplines. The boundaries are

vague and ecopsychology is informed by all these neighbouring fields. (Scull, 2008).

In ecopsychology people coexist in a cycle of life, like other organisms, and are directly

confronted with the physical world and not just mental constructs (Chawla, 2007). Furthermore,

ecopsychology suggests and describes that individual psychology takes place when people learn

through movement and exploration, such as children growing up close to nature or through playing

outdoors. Therefore, being a human means being involved in constant movement (Gibson, 2000). Under

ideal conditions children and adolescents discover the world through a wide range of movements in the

place where they live and in nature, since the natural environment plays a crucial part in this experience.

14

For learning and exploration, nature is a good playground and field of study since nothing

happens twice in the natural world (e.g. the chemistry of water) (Chawla, 2007).

By seeing people first and foremost as moving organisms in the environment, ecopsychology

sees them as a part of a relational system (Hibbard, 2003). Ecopsychologist Gibson (1979) suggested

the concept of affordances, which describes the properties of the environment that are described by the

relationship between the environment and other organisms. According to his concept affordances lay in

the relationship between nature and human-beings. Focussing on the subject of the paper the example

can be as follows: a wave has a certain shape and thus, allows a surfer to surf on it. This example relies

on the logic from Heft (1988). Therefore, it is about all creaturesÕ ability to take advantage of the

resources that the environment holds. Success depends not just on the qualities of the environment, but

equally on the biological systems that creatures have evolved to detect and use information about these

qualities, as well as the particular capabilities of individual organisms. Of course, the level of

affordances provided to humans are very different depending on the living conditions (Kytta, 2004,

2006).

Various studies (Chawla, 2007; Arnold, 2009; Sivek, 2002; Bymer & Gray, 2009; Gibson,

2000) define stronger connection with the nature in adolescence stages for those who were raised in a

less urban setting and had strong role models (parents, care givers, teachers), taking care of the

environment around them by action (Chawla, 2007) or by significant life experiences (Arnold, 2009).

Significant Life Experiences (SLE) are associated with pro-environmental attitudes and behaviour. It

was found that environmental leaders attribute their involvement in environmental action to spending

time outdoors, with parents, peers and teachers or reading books on relevant topics, e.g. environmental

destruction. The majority of the influences mentioned in SLE researches participants developed in their

childhood or adolescence and involved passionate role models such as parents, caregivers or teachers

(Chawla,1998; 2007; Sivek, 2002; Arnold, 2009). Previous researchers suggest that parents were

formative for all participants. Supportive parents were consistently present, but only this factor was not

enough to translate interest and values into action (Chawla 1998,2007; Sivek, 2002; Arnold, 2009). For

most people, the caregivers who first introduced them to the world remain their examples of what to

notice in the environment and how to respond to it (Chawla, 2007).

It is studied that adults who are the role models pay attention to the environment in four ways:

seeing land or water as a limited resource essential for family identity and well-being; by disapproving

of destructive practices; by experiencing pleasure while being out in nature; and through their own

fascination of earth, sky, water and living creatures (Chawla, 2007). The same people who taught care

for the land or water were also likely to express disapproval of other peopleÕs destructiveness, and when

they showed fascination with the details of things, it underscored lessons about the value of family land

or attitude to the natural water they use for familyÕs well-being, or general expressions of pleasure at

heading out into forests or fields (Arnold, 2009). By this ecopsychology explains the influence of close

role model caregivers on further attitude to nature or environmental activism.

The final principle of ecological psychology which helps to explain the formative experiences

of environmental activists is the importance of learning about the world first hand through oneÕs own

actions in it, rather than second hand when others represent it. Reed (1996) calls it Ôthe necessity of

experienceÕ. Outdoors especially, a person encounters a dynamic, dense, multi-sensory flow of

diversely structured information, but some places are richer in this regard than others. For that reason,

Reed (1996) suggested that the level of closeness to the nature or the access to affordance during the

development of a child is of importance due to the fact that it will influence the future exploration and

interconnection and care for the environment in adolescents, despite the influence of significant adults.

Primary experience is also necessary because it occurs in the real world of full-bodied experiences,

where people form personal relationships and attachments. This increases the motivation to protect the

15

surroundings, people they love and to build competencies and communities to do so (e.g. to protect the

river they grow up close to or to save the park from buildings) (Reed, 1996; Chawla, 2007).

Chawla (2007), suggests the positive interactive cycle of a human engagement with the

environment to support the principles of ecopsychology. As it is shown in Figure 3, the positive

interactive cycle starts with an animate organism who is human and has the ability to be mobile (e.g.

free to explore the environment autonomously) as well as the access to that environment. This is the

base to start the experience of interaction with nature. To proceed with a deeper exploration one (or an

animate organism) needs a certain level of affordances (as it was mentioned before with the branches

of the tree or the waves example). When the interaction happened in a satisfying way and gave some

further challenges to overcome there is a motivation to explore further, which positively leads to

growing environmental knowledge and competence (Chawla, 2007). The cycle presents the ground for

the human-nature interaction and can be interpreted broader than the focus on environmental activism.

However, this research will use the cycle to display the work of principles of ecopsychology in the

surfing community.

Figure 3. Interactive cycle of human engagement with the environment (by Chawla, 2007).

Last but not the least principle of ecological psychology relates to the value of organisations,

which environmental activists also credited as important influences in their childhood and youth

(Chawla, 2007). Barker (1968) developed the concept of Ôbehaviour settingsÕ, which are the customary

patterns of behaviour in designated places where people gather to engage in particular activities at

particular times (Chawla, 2007). These settings are constituted by the coordinated actions of people as

well as the affordance of the place. According to Barker (1968) these settings are influential for further

environmental activism. However, the base of affordances or role-models in a positive interactive cycle

are usually the factors that are deeply-rooted (Chawla, 2007).

Putting these principles of ecological psychology together, they illustrate how formative

childhood experiences, role-models and settings that a person experiences are to have a stronger

interconnection with nature, which eventually leads to more powerful environmental values and care.

16

4. Methodology

4.1 Research design

This thesis is conducted with a qualitative and inductive research approach. Qualitative research

is an umbrella term for a variety of approaches and strategies for conducting research aimed at finding

how human beings understand, perceive, interpret, and experience the social world (Campbell &

Hammersley, 2012). This research will be mainly concerned with the analysis of the complex,

contingent, and context-sensitive character of social life. Moreover, the analysis will observe actions

and outcomes, which are produced by people that interpret situations in different ways, and act

individually on the base of these interpretations. The logic behind the inductive approach is that

generalisations will be made about behaviour observed in a specific context or situation. In this instance,

the gathering of data is used to explore a phenomenon, identify themes and patterns and create a

conceptual framework (Saunders et al., 2012). This paper introduces research questions to define and

narrow the scope of the study. Further the research questions aim for objectives that shall be achieved

during the research process. There is no theoretical frame for successful motivators in grassroots

initiatives in surfing communities, yet. Therefore, this will be explored by identifying patterns at

existing and developing surfing communities in Ukraine and Germany. The theoretical framework (SC,

SL and ecopsychology) is used as an analytical lens. The analysis will be followed by a discussion

which will include recommendations for practice and further research. Eventually, the findings of the

thesis will be summarized in a conclusion.

The chosen method in the research is semi-structured interviews, where interviews are

conducted to understand the socially constructed world of research participants (Ritchie et al., 2014).

This was chosen due to the conversational style, which is often relevant for learning about motivations

behind peopleÕs behaviours and choices, their attitudes and beliefs, and the impacts on their lives of

specific policies or events. Semi-structured interviews often provide valuable information that was not

anticipated by the researcher (Raworth et al., 2012). In the thesis, 10 semi-structured interviews with

open ended questions were used, as it allowed the flexibility and depth of responses (Wiles, 2005).

These interviews were composed of a total sum of 12-40 questions, that were specifically adapted to

the individual background of the intervieweeÕs role in the surfing community. The noticeable difference

in interview-questions shows the individual approach to each interviewee, which indicated another

advantage of semi-structured interviews, which is the freedom it gives to the interviewees when

answering questions in their own frame of reference without being restricted by leading questions from

the interviewer (Wiles, 2005).

The semi-structured interviews were conducted and analysed by the authors themselves and

thus belong to primary data, which is generally understood to be the initial data specifically collected

by the original researcher concerned about the research problem. The literature review will be the

secondary data, understood as a portrait of data gathered from previous studies by a number of relevant

researchers (Heaton, 2004). The findings from the literature will be presented result-based and focused

on recent developments in the research field in the sections ÔintroductionÕ, ÔcontextÕ and Ôprevious

researchÕ. Therefore, the research will be approached by three modalities: by gathering formal data from

publicly available data, by collecting informal data shared between researchers and by accessing oneÕs

own data. By using all three approaches, the team of researchers aim to answer the research question at

micro (individual) and macro (societal) level.

The focus of this research is based on two countries - Germany and Ukraine, where surfing

communities exist and can therefore be compared and examined. Hence, the authors interviewed 10

surfers from both countries: 3 Germans and 7 Ukrainians with different levels of involvement in GRIs,

17

surfing communities and environmental activism to collect the primary data for the research. The total

sum of 10 interviews was chosen due to the predefined guidelines by Malmš University.

4.2 Collecting data

The ten interviewees were selected and consequently contacted through social media and email.

The main criterion for the participation in the interviews was the level of involvement in surfing

communities in Germany or Ukraine, as well as their participation in the IOSF, which was relevant

solely for German interviewees due to the fact the USC has not yet been formalized as a GRI. Gender

and age of participants was not taken into account, however, the place of living and growing up was

considered due to the theoretical framework of the paper. Ukrainian interviewees were found through

the USC groups in social media. German interviewees were found and chosen due to their involvement

in relevant IOSF and local surf clubs.

The structure of the semi-structured interviews was the following: after explaining the purpose

of the interview and research, questions regarding the intervieweesÕ personal details (nationality, place

of living etc.) followed. Afterwards, the interview was designed to continue with more detailed and

open questions to obtain a deeper view on the participants opinion about relevant subject areas. The

first questions were focused on the intervieweeÕs previous experience in surfing and also tackled the

reasons of involvement with the sport and connections with the nature of a particular interviewee. Then

a variety of questions followed that enabled the interviewer to understand the level of involvement in

IOSF (was relevant only to German interviewees). The interview questions were designed according to

a chosen model of GRI motivators by Grabs et al (2015). The model was described earlier in the paper

and provides an understanding of which factors have to be taken into account for societal change in a

developing GRI. As the focus of this paper is the interconnection of influences on individual and societal

levels on GRIs, the interview questions were formulated accordingly. Particularly the questions were

composed to find out how the individual involvement of a surfer with the IOSF is constructed and which

reasons for the involvement exist. Just as important for the research are the effects of the societal

conditions and political support on the IOSF. The questions were also rooted in the ecopsychological

theory to provide an overview of the participantsÕ involvement in surfing through their connection with

the nature.

One interview was conducted in person. The environment was chosen in a public environment

to make the interviewee feel as comfortable as possible to create a friendly and trustworthy atmosphere

(Flick, 2018). The additional nine interviews were then conducted via telephone or video-call, since the

interviewees are not living in Sweden, where the research was conducted. Each of the interview got

audio-recorded and then transcribed (Flick, 2018). Firstly, the transcript was authored in the native

language of both interviewer and interviewee, secondly, the interviews were translated to the language

of presentation. Whilst Flick (2018) describes different approaches to presenting translated findings

bilingually, the authors of the thesis will present findings coherently only in the language of

presentation. The answers of the interviews were used for an analysis by coding and categorizing the

collected data. The exact composition of the 10 interviewees by code, gender, country, organisation and

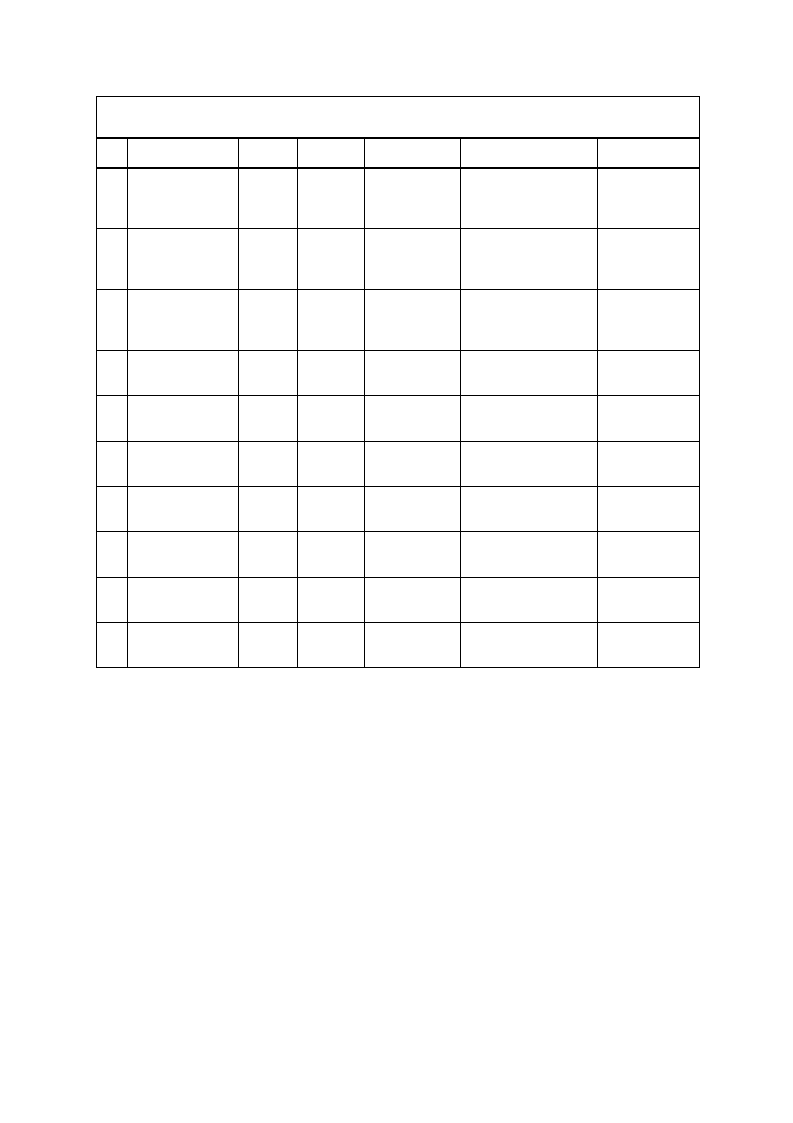

role is described in Table 1.

18

Table 1. Overview of 10 Interviewees from Germany and Ukraine

Interviewee

1 German

interviewee 1

2 German

interviewee 2

3 German

interviewee 3

4 Ukrainian

interviewee 1

5 Ukrainian

interviewee 2