Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

1

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

Nature Therapy

Developing a Framework for Practice

Thesis submitted for the degree:

Doctor of Philosophy ^

By: Ronen Berger

Supervisory team:

Head of studies and main supervisor: Prof. John McLeod

Supervisors: Dr. Andrew Samuel and Prof. Sue Cowan

External advisors: Prof. Haim Hazan, Dr. Ian Rotherham and Colin Beard

February 2009

Tayside Institute for Health Studies

School of Health and Social Sciences

University of Abertay, Dundee

NATURE THERAPY

DEVELOPING A FRAMEWORK

FOR PRACTICE

RONEN BERGER

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements of the University of Abertay Dundee

for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

February 2009

I certify that this thesis is the true and accurate version of the thesis

approved by the examiners

Signed

(Director of Studies)

(Q

Date

This is to certify that all the work that appears in the doctoral dissertation

Nature Therapy Developing a Framework for Practice, is my own authentic

work.

The work has been edited and corrected as per the comments given by the

examiners.

Ronen Berger

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

2

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................... 8

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS............................................................................................. 9

VOLUME 1 .................................................................................................................. 10

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION................................................................................10

1.1 Placing the Research in Context...........................................................................10

1.2 The Contribution and Aims of the Current Study............................................... 11

1.3 The Development of Integrated Therapies...........................................................12

1.4 Structure of the Thesis..........................................................................................15

CHAPTER 2 - BEGINNING THE JOURNEY - PLACING THE WORK IN

CONTEXT.................................................................................................................... 18

2.0 Introduction...........................................................................................................18

2.1 The Place I Come From - A Reflexive Perspective on the Journey................... 18

2.1.1 Prologue. 8th September 2006..........................................................................18

2.1.2 My Personal Journey - An Autobiographical Perspective............................. 19

2.1.3 The Impact of Culture..................................................................................... 29

2.1.4 Connection to the Land................................................................................... 30

2.1.5 The Meaning of Therapy for Me..................................................................... 31

2.1.6 The Meaning of Nature for M e....................................................................... 32

2.2 A Social-Psychological-Environmental Exploration into the Evolution of the

Relationship between Humans Beings and Nature.................................................... 34

2.2.1 Prologue.......................................................................................................... 34

2.2.2 Human - Nature Relationships in Traditional Cultures.................................. 35

2.2.3 Deep Ecology.................................................................................................. 42

2.2.4 Ecopsychology................................................................................................ 48

2.2.5 Seeking Reconnection: Body and Mind, Person and Community, People and

Nature........................................................................................................................50

2.2.6 Science's Limited Ability to Explain Complex Human Experiences............. 53

2.2.7 From Questions to Construction..................................................................... 57

2.3 Incorporating Nature into Therapy: Key Themes................................................ 58

CHAPTER 3 - A REVIEW OF THE RELEVANT RESEARCH LITERATURE.... 65

3.1 Adventure Therapy.............................................................................................. 66

3.2 Drama Therapy.................................................................................................... 73

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

3

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

3.3 Conclusions...........................................................................................................78

3.4 Aims of the Present Study.....................................................................................79

CHAPTER 4 - METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS.................................... 81

4.1.1 Introduction......................................................................................................81

4.1.2 From Quantitative to Qualitative Methods..................................................... 83

4.1.3 Action Research...............................................................................................85

4.1.4 Action Research and the Context of this Study..............................................85

4.1.5 Reflexivity........................................................................................................87

4.1.6 Reflexivity and the Context of this Study...................................................... 88

4.1.7 Grounded Theory.............................................................................................89

4.1.8 Grounded Theory in the Context of this Study.............................................. 91

4.1.9 Quality Control in Qualitative Research........................................................ 92

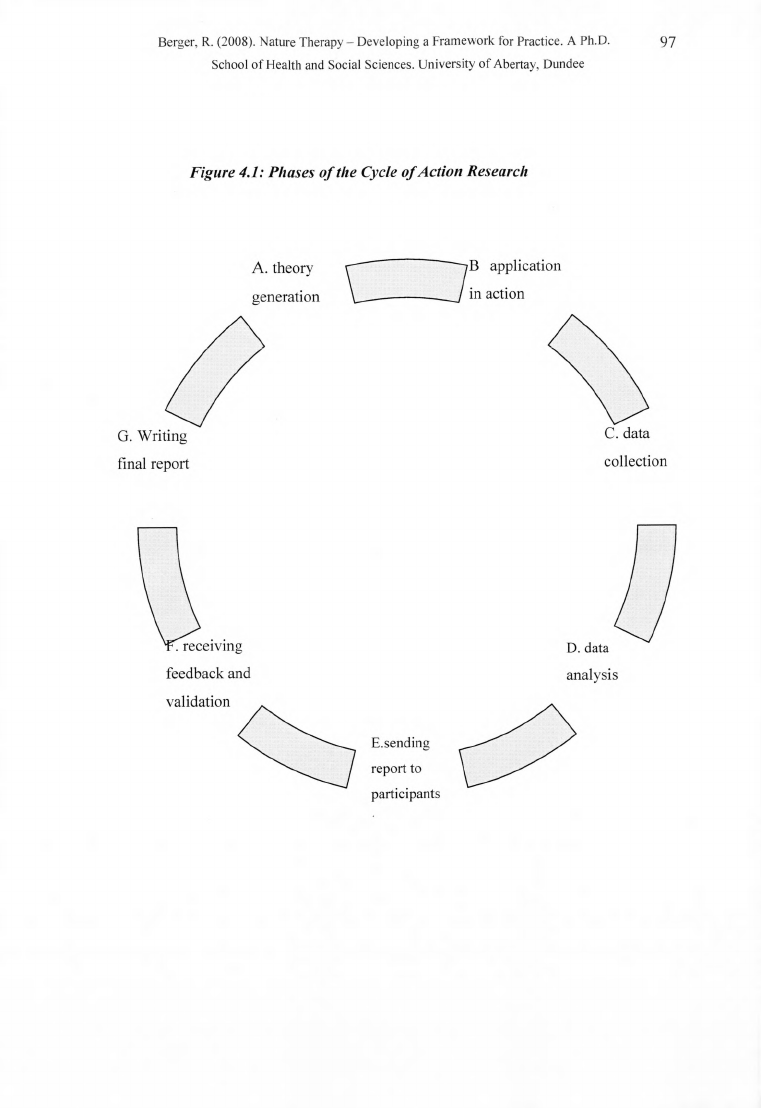

4.2 The Cycle of Action Research: An Overview of the Process........................... 95

4.2.1 Cycle 1: From Primary Reflexivity to the Creation of a Pilot Programme.... 98

4.2.2 Cycle 2: Developing a Therapeutic Programme - 'Encounters in Nature' for

the Ministry of Education in Israel.......................................................................... 99

4.2.3 Cycle 3: Developing Short Intensive Training Programmes....................... 101

4.2.4 Cycle 4: Developing Longer, Academic Trainings.......................................102

4.2.5 Cycle 5: Creating a Professional Community and Forming a Dialogue with

other Professions.....................................................................................................103

4.2.6 Cycle 6: Elements from the Process that Took Place in Parallel to the Previous

Cycles:..................................................................................................................... 104

4.2.7 Cycle 7: Work Related to the Viva-Voce and the Examiner's Report:........ 105

4.2.8 Selection of Action Research Data for Presentation......................................105

4.3. Research Procedures........................................................................................105

4.3.1 Case Study 1: 'Encounters with Nature' - Nature Therapy in a School for

Children with Special Needs...................................................................................106

4.3.2 Case Study 2: 'Between the Circle and the Cycle'....................................... 109

4.4 Research Procedure: Overview and Conclusions.........................................

112

CHAPTER 5 - 'BUILDING A HOME IN NATURE’- NATURE THERAPY WITH

CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS: A CASE STUDY.......................................113

CHAPTER 6 - 'BETWEEN THE CIRCLE AND THE CYCLE'............................. 133

6.1 Placing Things in Context:................................................................................ 134

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

4

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

6.2 Workshop 1 (7<hand 8<hJuly 2004).................................................................. 142

6.2.1 Aims of the Workshop...............................................................................142

6.2.2 Arriving..........................................................................................................143

6.2.3 First Circle - Place to Gather.........................................................................144

6.2.4 Second Circle - Bridging with Nature, Summoning Physicality and Creativity

145

6.2.5 Third Circle - Figures in the Sand............................................................... 146

6.2.6 Fourth Circle - Stepping into a Nature Therapist's Shoes........................... 147

6.2.7 Fifth Circle - Sunrise....................................................................................150

6.2.8 Processing and Conceptualization - Encounter 1 (22.7.04) - 'Between Spaces'

152

6.2.8.1 The place I came from............................................................................. 152

6.2.8.2 The actual encounter................................................................................153

6.2.8.3 Making the transition from workshop to everyday environment (T.2.10)153

6.2.8.4 Exploring boundaries (T.2.11)................................................................ 155

6.2.8.5 Between theory and grocess (T.2.9)........................................................ 157

6.2.8.6 A shared love for nature (T.2.4.)...............................................................158

6.2.8.7 Who is responsible for the process?........................................................ 158

6.2.8.8 Discussion and conclusions - first indoors encounter............................ 159

6.3 Workshop 2 (5th-6thAugust 2004)......................................................................159

6.3.1 Aims in Planning this Workshop...................................................................160

6.3.2 Arriving..........................................................................................................160

6.3.3 First Circle - Creating and Entering the Circle............................................ 161

6.3.4 Second Circle - Digging for Metaphors.........................................................162

6.3.5 Third Circle - What Hides in the Shadows?............................................... 163

6.3.6 Stories in the Sand.........................................................................................165

6.3.7 Fourth Circle - The Sunrise Brings New Meaning...................................... 167

6.3.8 Fifth Circle - Taking Sand Home..................................................................168

6.4 Processing and Conceptualization Meeting 2(18 August 2004).................... 169

6.4.1 Cycle 1: Making Dreams come True.............................................................170

6.4.2 Cycle 2: Between Theory and Intuition, Art and Science, Male and Female

(T .2 .9 ) ..................................................................................................................... 172

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

5

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

6.4.3 Cycle 3: Between Child and Adult, Strength and Vulnerability, Male and

Female (T.2.2 & T.2.1)...........................................................................................173

6.4.4 Crossing the Bridge - from Practice to Theory........................................... 174

6.5 Workshop 3 (2nd- 3rd September 2004)........................................................... 178

6.5.1 Aims in Planning the Workshop....................................................................178

6.5.2 The Therapist can Also Ask for Nature's Help............................................. 178

6.5.3 Circle 1 - Arriving (Between Solid Ground and Deep Water)..................... 179

6.5.4 Second Circle - Entering the Water...............................................................181

6.5.5 Third Circle - In the Light of the M oon........................................................182

6.5.6 Fourth circle - Making the Transition............................................................184

6.5.7 Fifth Circle - Sunrise......................................................................................186

6.5.8 Sixth Circle - Departure................................................................................188

6.6 Processing Meeting Workshop 3 (9th September 2004)................................... 188

6.7 Learning that Emerged from the Chapter - Discussion and Connection to the

Action Research Cycle..............................................................................................194

VOLUME 2 ................................................................................................................198

CHAPTER 7 - DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS............................................. 198

7.1 Using Action Research to Generate a Theory...................................................198

7.1.1 Action Research Cycle 1: The Development of a Preliminary Model of Nature

Therapy................................................................................................................... 198

7.1.2 Action Research Cycle 2: Testing a New Nature Therapy Framework with

Different Clients and in Different Settings, Delivered by Different Facilitators... 200

7.1.3 Action Research Cycle 3: Developing Intensive Training for Practitioners. 202

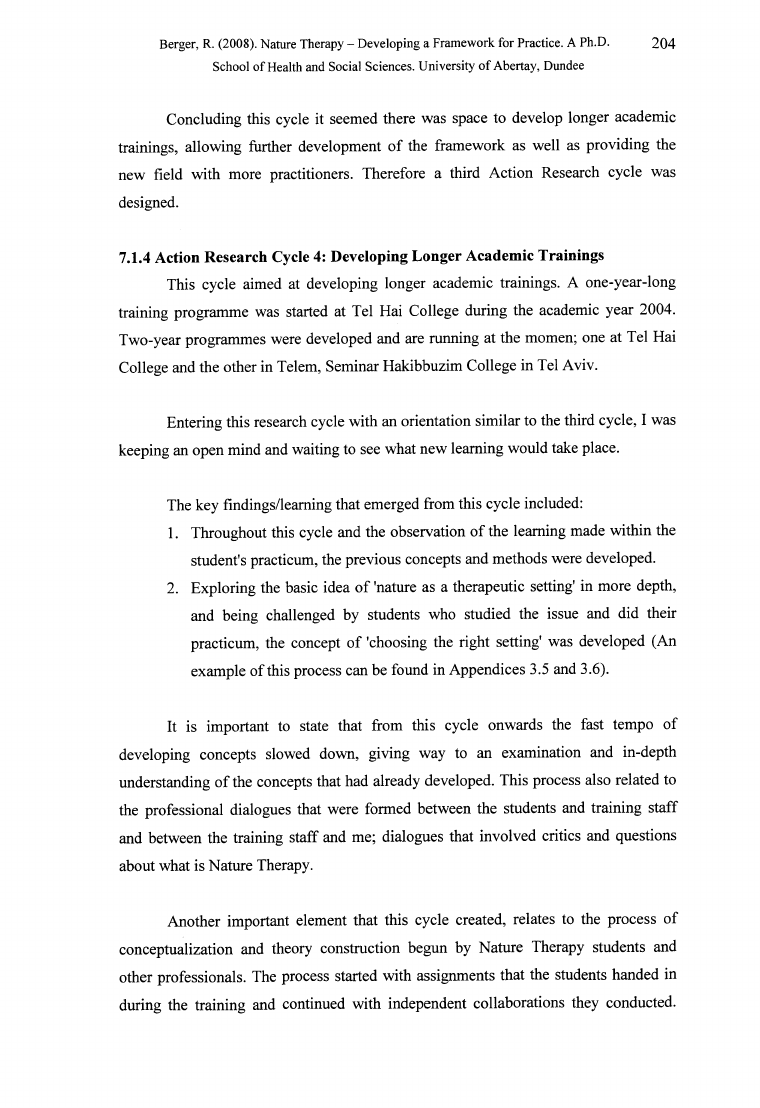

7.1.4 Action Research Cycle 4: Developing Longer Academic Trainings........... 204

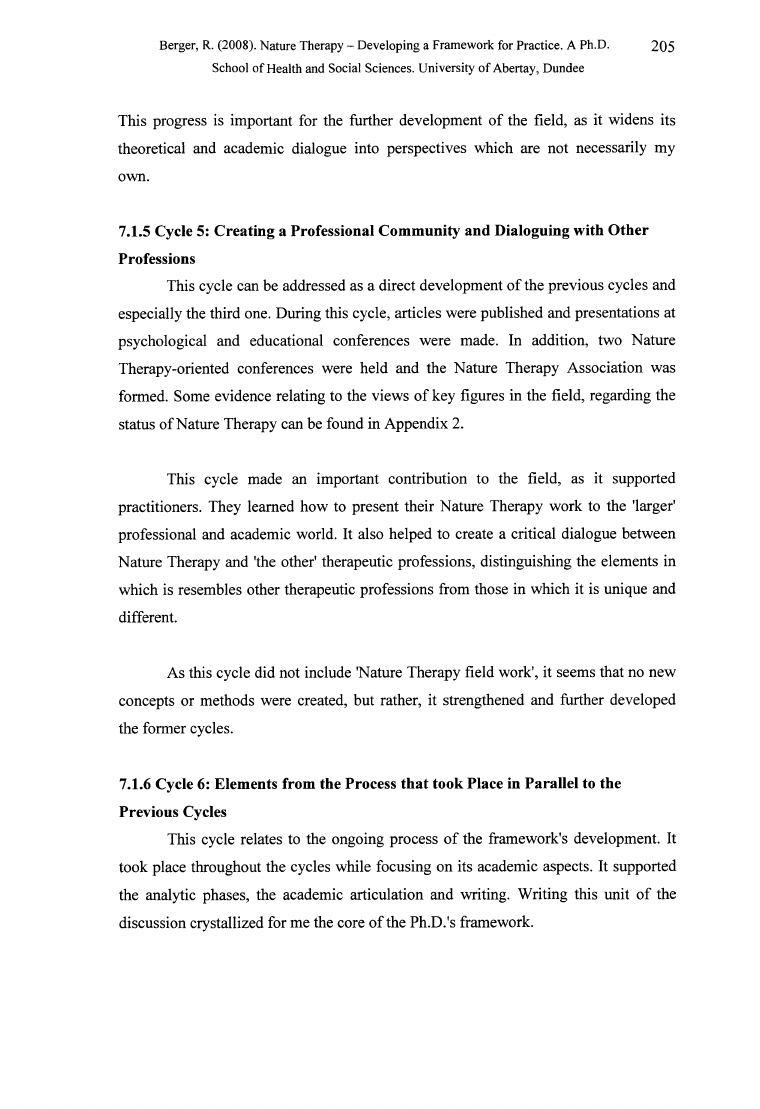

7.1.5 Cycle 5: Creating a Professional Community and Dialoguing with Other

Professions............................................................................................................. 205

7.1.6 Cycle 6: Elements from the Process that took Place in Parallel to the Previous

Cycles..................................................................................................................... 205

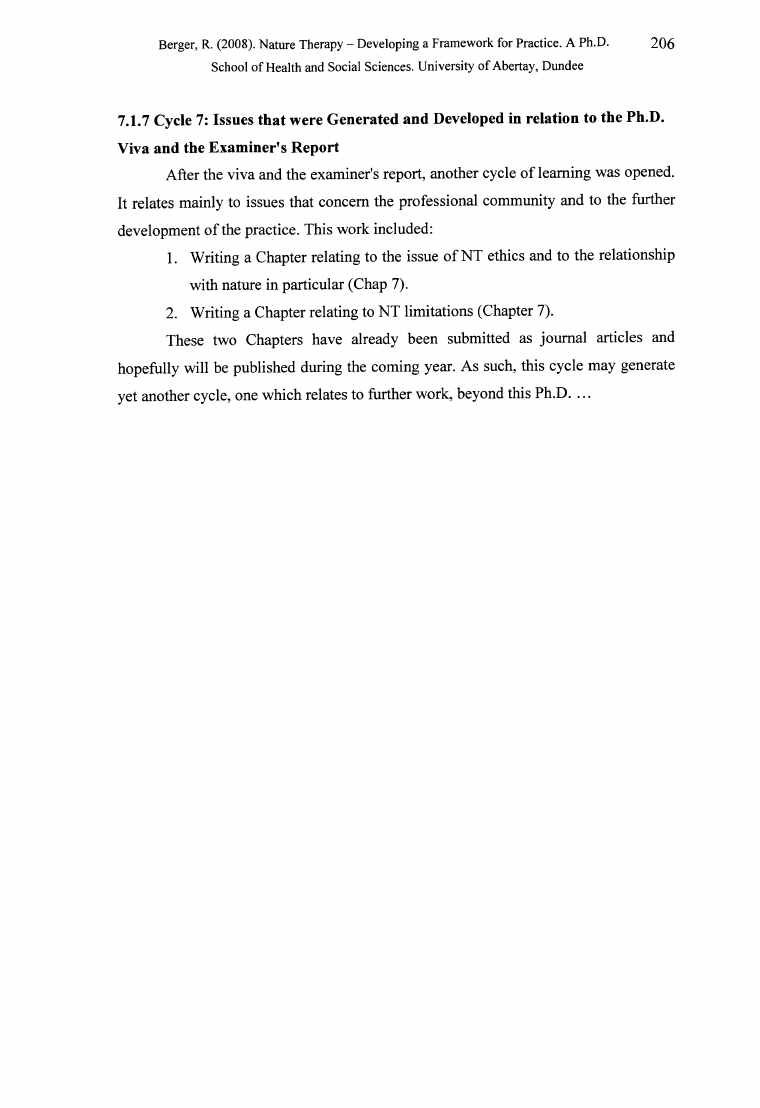

7.1.7 Cycle 7: Issues that were Generated and Developed in relation to the Ph.D.

Viva and the Examiner's Report............................................................................ 206

7.2 New Knowledge that the Ph.D. HasDeveloped............................................... 208

7.2.1 Developing a Fresh Eco-socio-psychological Philosophy Based on the

Evolution of the Human-Nature Relationship....................................................... 208

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

6

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

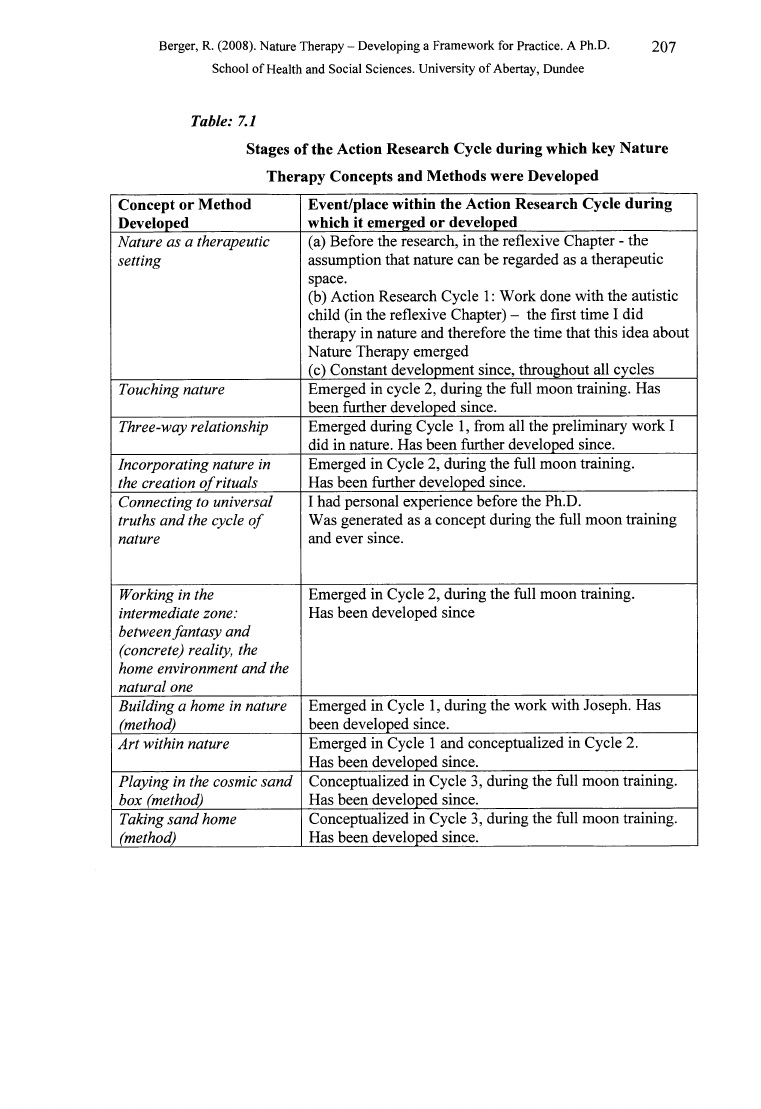

7.2.2 Concepts and Methods that the Ph.D. Developed........................................ 209

7.2.2.1 Nature as a therapeutic setting................................................................ 209

1 2 2 2 Touching nature.......................................................................................209

7.2.2.3 The Three-way relationship: client-therapist-nature............................... 210

7.2.2.4 Incorporating nature in the creation of rituals......................................... 210

122.5 Connecting to universal truths and the cycles of nature......................... 211

122.6 Working in the intermediate zone: Between fantasy and (concrete) reality,

the home environment and the natural one......................................................... 212

7.2.2.7 Choosing 'the right' setting..................................................................... 213

7.2.3 Methods and Techniques that the Ph.D. Has Developed............................. 213

7.2.3.1 Building a home in nature....................................................................... 213

7.2.3.2 Art within nature...................................................................................... 214

7.2.3.3 Playing in the cosmic sandbox................................................................ 215

7.2.3.4 Taking sand home.................................................................................... 215

7.2.4 Other Elements that the Work Developed................................................... 216

7.2.4.1 Developing a framework that can be implemented with different kinds of

populations........................................................................................................... 216

7.2.4.2 Developing an integrative therapeutic framework................................... 217

7.2.4.3 Developing alternative ways to relate to the hierarchy between therapist

and client.............................................................................................................. 217

7.2.4.4. Developing ways to include spiritual and transpersonal experiences in the

psychotherapeutic process.................................................................................... 217

7.2.4.5 Developing and defining Nature Therapy's attitude towards nature - from

an instrumental to an artistic standpoint.............................................................. 220

7.2.4.6 Developing an ethical code for Nature Therapy...................................... 221

7.2.4.7 Thoughts about the limitations of the practice........................................ 230

7.2.4.8 The concept of "Nature" within Nature Therapy.................................... 240

7.3 Ways in Which the Ph.D. Added to the Existing Body of Knowledge..........241

7.3.1 Discussion of the Contribution of the Ph.D. to the Field of Ecopsychology 241

7.3.2 Discussion of the Contribution of the Ph.D. to the Field of Adventure Therapy

244

7.3.3 Discussion of the Contribution of the Ph.D. to the Field of Drama Therapy247

7.4 Future Applications for Theory, Practice and Research................................. 250

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

7

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

7.4.1 Future Developments for Theory.................................................................. 251

7.4.2 Future Developments for Practice................................................................. 251

7.4.3 Future Applications for Research................................................................. 253

7.5 Validity and Methodological Issues.................................................................253

7.5.1 Research Validity and Trustworthiness........................................................ 254

7.5.2 Things I Have Learned.................................................................................. 256

7.5.3 Recommendations for Improving the Research............................................ 257

CHAPTER 8 - CONCLUDING THE JOURNEY.................................................... 259

CHAPTER 9 - REFERENCES................................................................................. 261

APPENDICES........................................................................................................... 279

APPENDIX 1 -RESEARCH PROCEDURES - RELEVANT DOCUMENTS...... 279

1.1 Information sheet: 'Encounters in Nature' Case Study 1.................................... 279

1.2 Information sheet: 'Between the Circle and the Cycle' Case Study 2 ................ 282

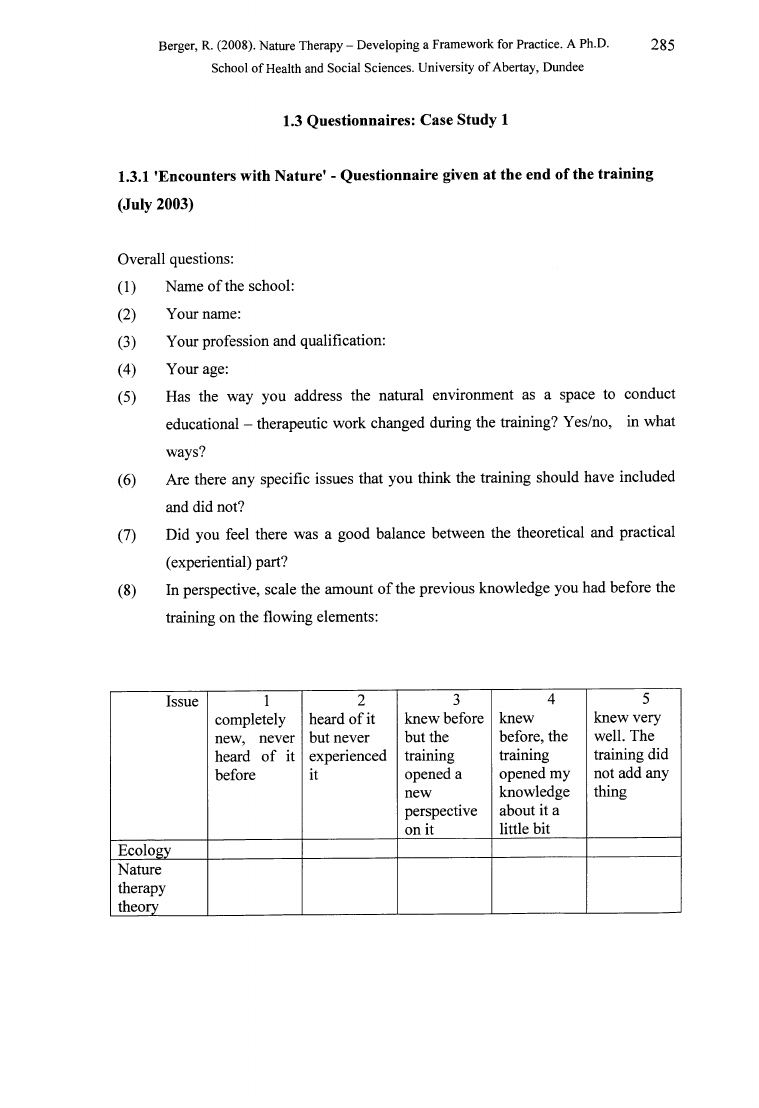

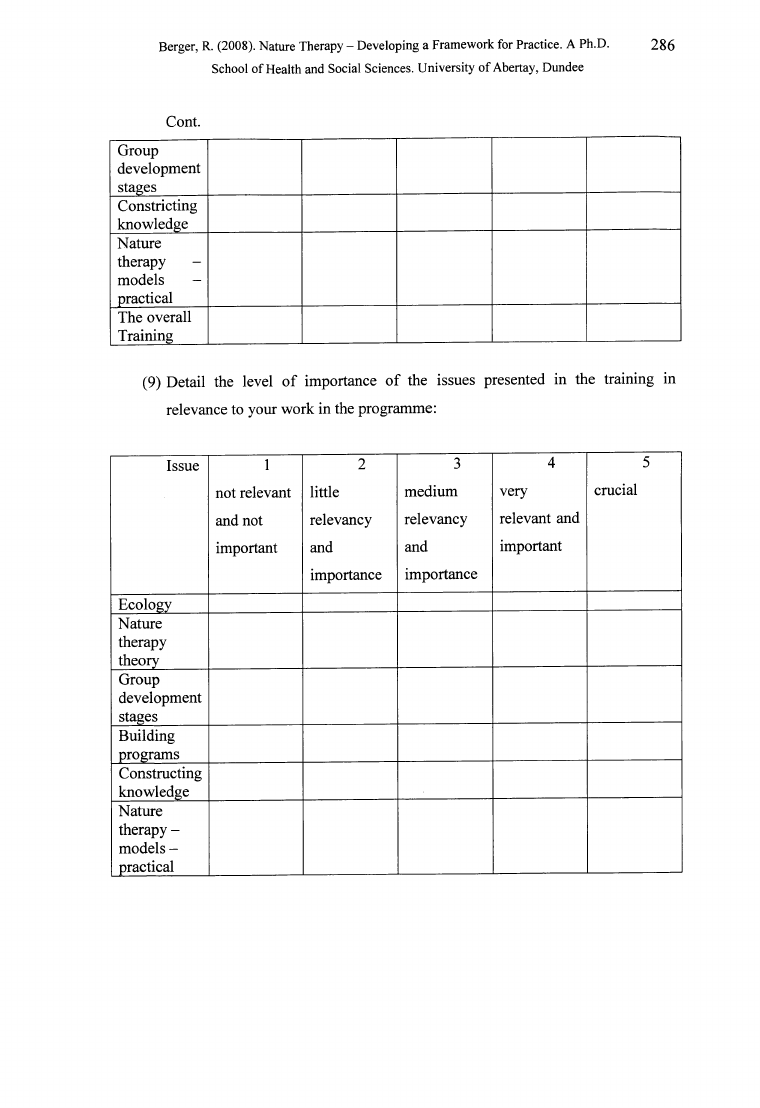

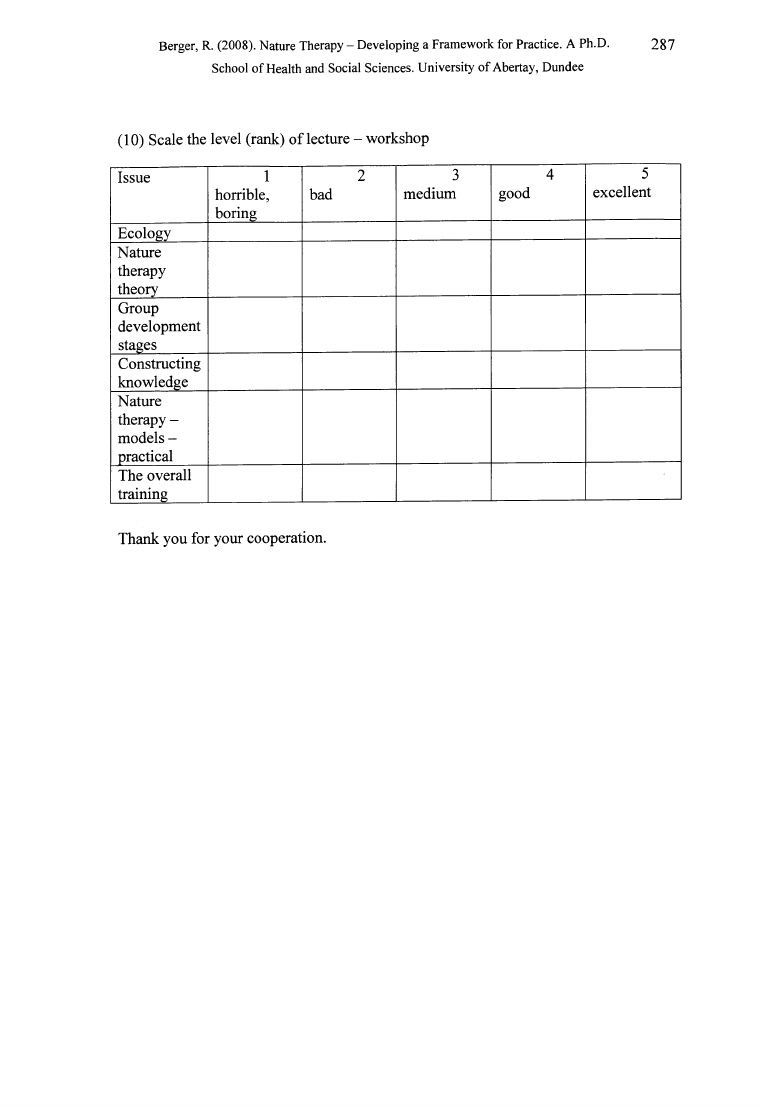

1.3 Questionnaires: Case Study 1 ............................................................................ 285

1.3.1 'Encounters with Nature' - Questionnaire given at the end of the training (July

2003).......................................................................................................................285

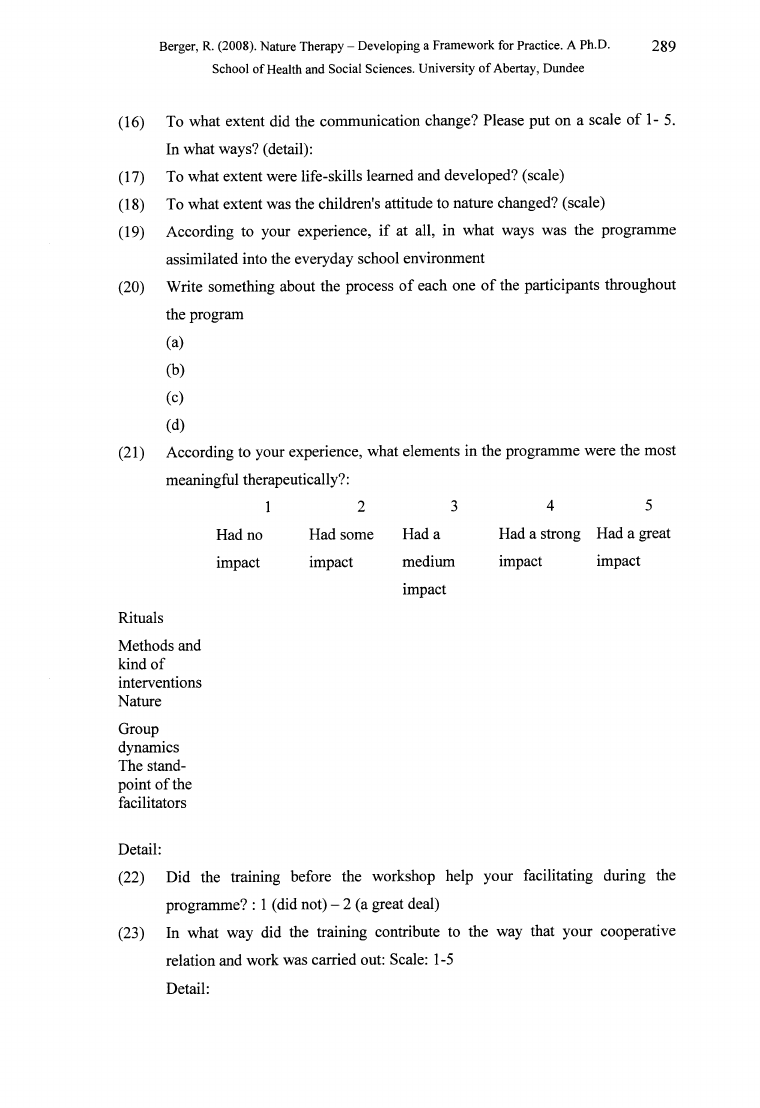

1.3.2 'Encounters with nature': End of the programme questionnaire (June 2004)288

1.4 Questionnaire: Case Study 2 (July-September 2004)........................................ 291

APPENDIX 2 - RESEARCH AND THEORETICAL ARTICLES.......................... 295

2.1 In the Footsteps of Nature - Nature Therapy as an Emerging Therapeutic

Educational Model.................................................................................................. 295

2.2 The Therapeutic Aspect of Nature Therapy....................................................... 304

2.3 Going on a Journey: A Case Study of Nature Therapy with Children with a

Learning Difficulty.................................................................................................. 317

2.4 Being in Nature: Being in Nature: An Innovative Framework for Incorporating

Nature in Therapy with Older Adults...................................................................... 327

2.5 Building a Home in Nature - An Innovative Framework for Practice............. 333

2.6 Choosing "the Right" Space to Work in - Reflections Prior to a Nature

Therapy Session....................................................................................................... 342

2.7 A Safe Place - Ways in which Nature, Play and Creativity can help Children

Cope with Stress and Crisis...................................................................................... 347

2.8 Turning Verbal Interpretations into Experiential Interventions - From Practice to

Theory.......................................................................................................................358

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

8

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

ABSTRACT

The relationship between human beings and nature has played an important

role throughout history, as part of traditional medicine and curative rituals. The

Shaman, the healing man, incorporated nature into rituals aiming to help both the

individual and the community heal from misfortunes and make the transition from one

life phase to another. However, the development of industry and urbanization put a

distance between human beings and nature. The new healing methods that were

constructed in the 20th century largely overlooked the relationship with nature,

working mainly through cognition and verbal communication, relating to the

relationship between people as the core element. In the last decade, along with the

development of post-modernism, new therapeutic approaches emerged. Some of them,

like the expressive-art therapies, seek to expand cognitive and verbal techniques to

non-verbal and creative modes of working, emphasizing people's creativity and

imagination abilities. Other approaches seek to expand the process by relating to 'the

larger then self, inviting transpersonal and spiritual work to widen the person-to-

person discourse. Ecopsychology invites people to expand their relationships beyond

the 'person-to-person' relationship into one which will include nature. Despite its

nature-oriented philosophy, however, Ecopsychology has not yet articulated into a

therapeutic form, that specifies practical methods for therapeutic work. The present

study aims to develop a therapeutic approach taking place in nature, using non-verbal

and creative methods to extend common therapeutic practices in ways that can include

a dialogue with nature. Using a reflexive Action Research strategy, the study

examines the experience of both practitioners who used Nature Therapy in practice

and who took part in training courses, and uses these data as a basis for the

conceptualization and development of an innovative therapy theory. The implications

of the study, for theory, research and practice in psychotherapy, are discussed.

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

9

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to acknowledge a number of people without whose ongoing

support this work could not have been accomplished:

Gad and Maira Berger - my parents, for the belief they have in me at crucial

times.

Lilach Berger-Glick - my partner in ongoing love, companionship and trust,

who has joined me on this journey.

Alon and Neta - my children, for creating the father within me.

Professor John McLeod - my Ph.D. supervisor, for hearing my voice and

teaching the dancer within me to talk and write.

Michal Doron - my former clinical supervisor and present colleague, for

supporting me in the creation and development of the Nature Therapy practice

Arye Bursztyn and Professor Mooli Lahad - my teachers, for teaching me the

magic embedded in dance and improvisation, fantasy, myth and drama.

My clients and students - for constantly teaching me what Nature Therapy is.

The Golan wolves and the Banias River - for giving me new life.

M y heart is with you.

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

10

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

VOLUME 1

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION

1.1 Placing the Research in C ontext

The aim of this introductory Chapter is to highlight some of the key issues

explored within the thesis, identify some over-arching research questions, and

introduce the structure of the thesis.

The potential therapeutic aspects of contact with nature have been well

documented by several writers (Abram, 1996; Berger, 2004; Beringer and Martin,

2003; Davis, 1998, 2004; Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989; Roszak, 2001; Totton, 2003). In

recent years, the issue of human-versus-nature relationship has received greater

recognition due to the negative effects that some aspects of technological

developments have had upon various social and environmental processes (Roszak,

2001; Roszak et al., 1995; Totton, 2003). The two main areas of practice in which the

therapeutic impact of contact with nature has been explored are Ecopsychology, and

Adventure Therapy.

The developing field of Ecopsychology represents a social-therapeutic-

environmental philosophy arguing that reconnection with nature is essential, not only

for the maintenance of the physical world (habitats, animals, plants, landscape and

cultures) but also for people's basic well-being (Roszak, 2001; Roszak et al.., 1995;

Totton, 2003). However, in the context of this Ph.D. thesis, it is important to state that

even though Ecopsychology offers a fresh philosophy and political standpoint, it has

not yet developed a practical therapeutic framework, nor has it generated research that

has examined its impacts in therapy (Rust, 2005; Sevilla, 2006; Totton, 2003).

The growing field of Adventure Therapy reflects a different dimension of this

aspect, as it uses the outdoors as a setting for educational and therapeutic work. As

discussed in Chapter 3, Adventure Therapy seems to relate to nature only as a setting

that provides the challenges and obstacles needed for the operation of this problem

solving and task-oriented approach (Beringer and Martin, 2003; Itin, 1998; Richards

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

11

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

and Smith, 2003). The attitude of Adventure Therapy towards nature has been

receiving a growing amount of criticism. Both practitioners and researchers argue that

this approach misses out on the spiritual and emotional benefits that the relationship

with nature contains (Berger, 2003; Beringer, 2003; Beringer and Martin, 2003;

Bums, 1998; Davis, 1998; Roszak et al., 1995). In addition, its theoretical basis has

been criticised due to the lack of sufficient framework (Cason and Gillis, 1994; Hattie

et al.., 1997; Hovenlynck, 2003), on the claim that without academic and clinical

development and validation through research, the ongoing debate regarding the issue

of the field's professional boundaries (therapeutic or educational?) will not be solved

(Hovenlynck, 2003; Itin, 2003; Peeters, 2003).

1.2 The Contribution and Aims of the Current Study

This Ph.D. seeks to develop an innovative theoretical framework that will add

to the existing body of knowledge present in the fields of Adventure Therapy and

Ecopsychology. As such, it will integrate elements from the aforementioned areas

combining additional elements from Drama Therapy, the Narrative approach,

Transpersonal Psychology and Gestalt as well as concepts found in anthropological

literature.

The framework will include theory and methods relating to nature as a core

reference point. It will add to Adventure Therapy's present framework, while

extending its concrete and cognitive orientation to add creative, non-verbal and

transpersonal dimensions. These concepts and framework can be used to develop

more appropriate, productive, therapeutic interventions for people with verbal and/or

cognitive difficulties and for those who would like to do therapy in experiential ways

while keeping close contact with nature.

Last but not least, as the theoretical basis of the Ph.D. will include

anthropological references, relating to the way in which Shamans used nature for

healing rituals, the work will also add to the general debate about the place of

spirituality within psychotherapy, adding specific knowledge about ways in which

contact with nature can take part and assist such processes.

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

12

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

The researcher will make use of his pre-assumptions, based upon his previous

experience as an ecologist and as a therapist. He will also use reflexive Action

Research strategy and Grounded Theory analysis to further explore these assumptions,

generate new concepts and frameworks, and to examine their impact upon varied

populations and different settings.

1.3 The Development of Integrated Therapies

One of the key issues dominating the field of psychotherapy, for the past fifty

years, has been the question of the theoretical basis of practice. Although a number of

well-established approaches to therapy, such as psychoanalysis and cognitive-

behavioural therapy (CBT), have their own distinctive theoretical foundations and

forms of practice, there are also a large number of other approaches which are

'integrative'; assembling ideas and techniques from other fields. The existence and

popularity of the new movement towards integrationist theories is driven by a belief

that established approaches to therapy are incomplete, and that more effective

approaches could be developed by adding new elements to previous approaches

(assimilative integration), or by creating new structures of theory and practice by

welding together aspects of other approaches (McLeod, 2003a). In recent years, the

integrationist movement in psychotherapy has begun to move beyond seeking merely

to bring together concepts and techniques from within traditional psychology and

psychotherapy. It had adopted ideas and practices from other domains. The process

includes a development of a more holistic, mind-body-spirit and ritualistic framework,

including elements such as forgiveness, mindfulness and contact with the 'larger than

self (Al-Krena, 1999; Davis, 1998; Rust, 2005; Jerome, 1993; Lahad, 2002; West,

2000, 2004). In addition, the cognitive discourse and its verbal mode are being

expanded with the development of creative approaches that integrate concepts and

methods from theatre, dance and art into the psychotherapeutic melee (Jennings, 1998;

Lahad, 2002, Landy, 1996; Rubin, 1984). These developments, within the broader

field of psychotherapy as a whole, provide a perspective from which it is possible to

locate the focus of the present study, on the relevance of nature for psychotherapeutic

practice, as an issue that has hardly been studied or developed. A review of current

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

13

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

debates revolving around the role of theoretical integration in psychotherapy can be

found in Norcross and Goldfried (2005).

These concerns draw attention to the key question: what makes a set of ideas

come to be regarded as 'theory'? One of the by-products of the attention to theoretical

integration, manifested in the psychotherapy community, has been a consequent

interest in the nature of psychotherapy's approach - what is it that is being integrated?

It is widely accepted that all approaches to psychotherapy share a number of 'common

therapeutic factors' such as the development of a supportive relationship, the

opportunity to express emotion and the installation of hope. In addition to these

common factors, the different elements of any specific psychotherapy approach have

been summarised by McLeod (2003a: Chapter 3), who suggested that a psychotherapy

approach must encompass the following features:

1. An organised and coherent set of concepts, comprising:

a. Underlying philosophical or 'meta-psychological' assumptions (for

example, in psychoanalysis, the idea of the ‘unconscious’).

b. Theoretical propositions, predicting connections between

observable events (i.e., in psychoanalysis, the posited causal

association between certain childhood events and adult

psychopathology).

c. Observational terms (i.e., in psychoanalysis, concepts such as

'transference' or 'denial').

2. A distinctive set of therapeutic procedures or interventions: i.e., systematic

desensitization is a distinctive CBT procedure, and interpretation of

transference is a distinctive psychoanalytic procedure. Also, it must be a

framework for deciding on which procedures are most appropriate for

specific clinical situations, presenting problems, and client groups.

3. A knowledge community: a network of people and institutions that sustain

the approach as a form of practice - books, articles, training courses,

journals, conferences, meetings, etc.

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

14

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

4. An account of the personal, social, cultural and historical context within

which the approach has been developed. For example, previous research

has identified the close link between the life-story of the key figures in the

main psychotherapy theories (people such as Sigmund Freud and Carl

Rogers), and the core characteristics of the approaches they founded.

A central aim of the current study is to develop a theory of Nature Therapy

that satisfies the criteria listed above. Specifically, the thesis seeks to address the

following set of research questions:

a. What are the concepts (philosophical, propositional and observational)

used by practitioners of Nature Therapy and in what way can they be

articulated into the creation of a 'theory'?

b. What are the therapeutic methods and interventions used by practitioners

of Nature Therapy and in what way can they be integrated in practice?

c. In what ways has the Nature Therapy approach been influenced by the

biography and socio-cultural context of the person involved in its

development?

The aim of this study is to provide grounds for the development of an

innovative therapeutic approach titled Nature Therapy. The core of the approach will

deal with the ways it incorporates nature into the process and to the different

applications it has in practice. The thesis will present a framework, concepts and

methods that can help practitioners incorporate 'nature' into their practice, as well as to

develop this new form of therapy. It will include case studies that will examine the

approach's impact upon different clients and will offer a chance to explore it through

action.

The intention is to use this thesis as the basis for planning further research into

the effectiveness of Nature Therapy, informed by the Guidelines for the Evaluation of

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

15

School of Health and Social Sciences. University of Abertay, Dundee

Complex Interventions (MRC, 2000). It is also hoped that the study will provide

guidelines that may be valuable for other psychotherapy practitioners engaged in the

early stages of establishing innovative forms of practice.

1.4 Structure of the Thesis

The study that has been undertaken comprises a series of action research

cycles that took place over a period of several years. It is not possible, within the

space limitations of this thesis, to include full documentation of all aspects of the

research that has been carried out. Accordingly, the thesis incorporates a selection of

relevant material, along with copies of additional papers that have been published (see

Appendix 3). A summary of thesis Chapters is provided below:

Chapter 1: Introduction

C hapter 2: B eginning the Journey - P lacing the Thesis in Context. This

Chapter begins with a reflexive section that describes the researcher's biography and

standpoint towards the issues that the thesis includes. As the researcher is directly

involved in the study - as trainer and supervisor of the practitioners who facilitated the

first case study and the facilitator of the second - this reflexive section sheds light on

the way 'his story' might have influenced the study. Afterwards, aiming to place the

thesis within its larger eco-socio-psycho context, and in order to highlight some of the

dynamics that triggered its emergence, the second main section within the Chapter

explores the evolution of the human - nature relationship, highlighting it from a

specific social-psychological-environmental perspective. The Chapter concludes with

a theoretical section where the key themes within Nature Therapy are presented,

providing the thesis with its theoretical ground.

Chapter 3: A R eview o f the R elevant Research Literature. A literature review

is presented, aiming to place the work within its academic milieu and to explore

research done in the field. As this thesis imbibes from a number of disciplines, the

review is mainly focused on two: Adventure Therapy and Drama Therapy. The first,

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

16

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

due to the resemblance in setting (working in nature) and the second due to its use of

creative modes of work and use of rituals.

Chapter 4: M ethodological Considerations. This Chapter contains three sub-

Chapters. The first presents the methods which were chosen for the current research,

using reflexive Action Research strategy and the Grounded Theory analytic approach.

The second sub-Chapter presents the cycle of Action Research - the movement

between the construction of theory, implementation of programmes and development

of professional community. The last sub-Chapter presents research procedures:

recruitment of participants, data collection, analysis, writing the report draft, receiving

participant's feedback, writing the final report and publishing.

Chapter 5: Building a H om e in Nature': Nature Therapy f o r Children with

Special Needs - A case study. A qualitative research based on the experience of

practitioners who facilitated a Nature Therapy programme in a school of children with

special needs. The case study explores the programme's impact; focusing on the way

nature influenced the process.

Chapter 6: 'Between the Circle and the Cycle' - using a description o f

N ature Therapy Training to Illustrate the Framework. This case study provides an

in-depth description of an advanced Nature Therapy training. Using the voices of

participants and facilitator, the Chapter presents fresh concepts and methods that can

be incorporated in Nature Therapy work, as well as in the larger therapeutic

community. Since the case study is carried out on 'normal' adults, it also highlights

some of the impact that Nature Therapy can have upon clients. As the Chapter is

written as a 'showing', it also provides a kind of protocol that can be used in the design

of future training.

Chapter 7: D iscussion and Conclusions. This Chapter discusses the research

findings. The first unit relates to ways in which the framework was developed and

generated from the Action Research cycle. The second unit summarizes the research

outcomes, highlighting the main concepts and methods it produced. The third unit

demonstrates ways in which the Ph.D. adds to the existing body of knowledge and to

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

17

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

the fields that stand at its basis. The fourth unit highlights ways in which the research

can be applied to the development of future practice, research and theory. The last unit

discusses the research's creditability and other methodological issues.

Chapter 8: Concluding the Journey.

Chapter 9: References.

Appendices. This section includes research procedures - documents relevant to

the thesis; research and theoretical articles about Nature Therapy.

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

18

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

CHAPTER 2 - BEGINNING THE JOURNEY - PLACING THE WORK IN

CONTEXT

2.0 Introduction

The aim of this Chapter is to provide the personal and theoretical context for

the study. Because the research that was carried out involved my own participation as

therapist and trainer, and also as researcher, it seemed appropriate to place special

emphasis on reflexive methodology (explained more fully in Chapter 4). The use of

reflexivity in research means that the researcher does everything possible to be open

about his or her biases, expectations, and relevant life experiences. The first major

section of this Chapter, therefore (section 2.1) attempts to place the researcher within

the context of my own biography, experience, and values. The second major part of

the Chapter (section 2.2) introduces the main theoretical, philosophical, conceptual

and historical ideas that have informed the development of this piece of research.

Because Nature Therapy is a pluralistic or integrative model of therapy, and

encompasses aspects of practice not usually addressed in therapy theories, Section 2.2

is wide-ranging in its scope. In section 2.3, the key themes to emerge from the earlier

parts of the Chapter are identified.

2.1 The Place I Come From - A Reflexive Perspective on the Journey

'Know the place you came from,

Know the place you are going to...'

(David Ben Gurion, Thefirst Israeliprime-minister and desert lover)

(Translatedfrom Hebrew)

2.1.1 Prologue. 8thSeptember 2006

The hour is 20:10 and I am sitting on the balcony of Glenmore Lodge,

Aviemore, Scotland. The sun is setting but the temperature is pleasant. I am far away

from home, but after spending a week at Abertay University, with the trees and

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

19

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

mountains I feel at home. Coming here after a week's supervision I did not plan to

write this Chapter, but spending time in the woods today made me reflect upon this

journey and the writing of this Ph.D. thesis. The many spiders I came across, building

and containing their homes made me think of my own home, my family, friends and

community. I also thought about Nature Therapy as a kind of home that has been built

during the last 4-5 years. It is amazing that the two journeys - as father to my children

and as 'father' of Nature Therapy - started simultaneously. In a few days, when I return

home, we will be moving to the kibbutz I lived in when I first wrote the words 'Nature

Therapy' sitting in the oak woods, above the Banias River, on the edge of the Golan

Heights, my home...

2.1.2 My Personal Journey - An Autobiographical Perspective

Trying to explore the connection between my personal journey and the

development of Nature Therapy, it seems that the two stories are intertwined - perhaps

inseparable... it seems that only now am I taking my first independent steps...

Therefore, I have chosen to explore the issue by looking into 'our' relationship

throughout my development, from early childhood until today.

Early Childhood

I was bom in Zahala, a small suburb in Tel-Aviv, Israel. Though I believe I

was raised by two loving parents and I know I had a sister who was 4 years younger

than I was, my strongest memories from early childhood relate to our two Alsatian

dogs. Reflecting on it now, nearly 30 years, later it seems that this powerful memory

is connected to the feeling that they were always there, taking care and being with me.

Stories that run in the family taught me that when I was a baby, Gipsy, the dog

allowed only my parents to come near me and touch me, and Capi, the bitch used to

sleep by my bed and follow me wherever I went. Later, when I had difficulties in

school, starting to read only in the fourth grade (not to talk about basic mathematics

which I still cannot handle), and finding it hard to sit on a chair in class all day long, I

found refuge in the orchard behind our home, running there alone or with my dogs.

There, I could find peace; nothing I did was 'wrong', no one called me names,

punished me or sent me to sit near the principal's office. Luckily enough, when I

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

20

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

reached third grade my home-room teacher left school and the new teacher did not ask

me to read in front of the class. Instead, she found supportive ways to make use of my

restless mode of being. She used to send me to water the plants, help the administrator

and bring chalks... I was a strange boy, spending much time within my own

imagination, protecting ants from being stepped on and talking to the dogs. I was quite

lonely. I do not know if that is what I felt then, but thinking of it now makes me sad.

Nature was indeed a safe and containing place for me, one in which I could play,

imagine and be whomever I wanted to be.

My mother was very concerned about my performance in school and did all

she could to help, taking me to a private tutor (who I hated), sending me to

psychologists (whom I disliked) and meeting the school principle on a regular basis.

My father was hardly home, and when he was present he mainly watched T.V.

Reflecting on it now, being a father and a therapist, it seems they simply did not know

how to join me, how to be with me. I think they were embarrassed by my dramatic

personality and love of dance. They did not know what to do and how to deal with my

way of being. I know my father wanted me to be like his friends' sons, playing tennis

and behaving 'like a man' and tried to shape me like them. I do not know what my

mother's story was; I think she really wanted me to be happy, but our concepts of

happiness were so different. She took me to concerts and taught me manners, but I

wanted to dance, make up stories, play in the sand and touch frogs.

Today, some 30 years later, the orchard behind our home is tree-cleared and

the open wild space is turning into a housing complex.

Teenager (age: 12-18)

When I was 12, after much concerted effort on my parents' part, I moved to a

special class, in a new school outside my settlement. It was oriented around

environmental studies and knowledge of the land. Its syllabus was much more

experiential; one that included weekly trips and intensive workshops in nature

throughout the year. As it had quite a different orientation than other classes in school

it was named 'the weirdoes'... but at least we were a group... This change gave me a

new lease on life, not only because it allowed me to start afresh in a place where I was

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

21

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

not known as the 'dyslectic' or 'strange' kid, but also since it made room for my skills,

interests and talents (which were not reading, writing or sitting quietly). The fact that I

was used to being in nature became a strength and allowed me to feel acknowledged

and respected by my peer group, a group in which I felt safe and loved, perhaps for

the first time in my life. My home-room teacher liked me and did not seem to make a

fuss about my being a poor student. By that time the issue of dyslexia was beginning

to receive recognition and my mother was efficient and made sure that I was

diagnosed, and that I receive the proper help and attitude in school. As school was in

a different settlement, I used to walk there through the same orchard where I used to

run to as a younger child. These daily journeys, before and after school, allowed me

the private time to touch base with my secret and imaginary space. Thinking of it now,

it seems that my connection with this small natural zone behind my house, with its

orange trees, open-wild landscape and small stream, was very intimate, romantic and

from a psychological standpoint, even symbiotic. I knew the fox dent and the falcon's

nest in spring, the best tree to pick figs in summer, and the hideouts from the orchard

watchman in winter, after being spotted picking oranges. Today, I would probably not

allow my children to make this journey alone, but in those days the issue of safety was

different and I do not remember being scared. Nature was home.

When I was fifteen my hobby of horse-riding became more serious. My

parents gave me my own horse, and I took care of it and rode daily. I used to leave

school early and go to the stable. Talking to my horse as if he was a person made

some of the people in the stable laugh, but at the same time helped me find other

people who also talked to their animals...There I met people who joined my journeys

in nature, and we rode through orchards together. I was practicing dressage and show

jumping, so I started competing and realized that I liked it. I made friends with riders

my age and formed meaningful friendships and relationships.

I was still a poor student, needing to pass intermediate examinations every

summer and ongoing private tuition in mathematics, which I hated. Thankfully, my

horse, the orchards and friends were there to provide compensation.

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

22

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

Young A dult (age 18-24)

On reaching the age of 18,1was recruited into the Israeli army. I found myself

spending 3 years in a bunker deep underground. Companionship was good, but the

work itself did not give me meaning or pleasure and I could hardly wait for it to end.

On weekends and holidays, I used to go to the desert with one or two friends, walking

through the mountains, sleeping out and watching animals. During this period, I

developed a special love for birds of prey, which I cherish to this very day. This was a

different experience in nature, going on adventurous journeys, seeking to confront my

physical and psychological strength, using the time to get to know friends from

additional perspectives and deepen our relationships. During this time, I strengthened

my outdoor skills: navigating, climbing and surviving in the wilderness. It was during

this period of time I realized that my future would be linked with nature and its

conservation.

As soon as I finished my army service, I moved up north, lived on a small

kibbutz (a communal settlement) and joined the first B.A Ecology Studies in Israel, at

Tel-Hai College. As a scientific and technological/ environmental science, it did not

answer most of my expectations, which apparently related more to the philosophical,

psychological and educational aspects of this field and not to empirical subjects such

as physics, mathematics and chemistry... Nevertheless, the people I met there shared

my love for nature; some of them were involved in environmental activism, nature

conservation activities and environmental education. Under their influence, I joined

the regional field school (a network of the Israeli Society for the Protection of Nature),

received training as a Nature Guide and worked as a part-time instructor. During the

three years of my B.A studies, I used to take people for guided walks in nature, telling

them some of the history, botany and zoology of this beautiful area. At the same time,

in order to cover my living expenses, I took care of the kibbutz stable, and worked

with the kibbutz kids, particularly those who had emotional, physical and/or social

difficulties. The parallel jobs made me aware not only of the pleasure I got from

working with people in nature but also of the meaningful interactions they create.

Another important way I was affected by the transition to the north of the

country connects to the time it allowed me to spend in a new natural environment; a

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

23

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

wild one, rich with water and animals. Not being familiar with the area, I took time to

wander around without a map, discovering the hidden springs and ponds, the deserted

fruit orchards and the wild animals... the revelation of what had become my new

home, gave me the comfort I needed for my struggles with mathematics and physics. I

was also giving more space to my creativity and sexuality, and found that I could give

my body more freedom. Swimming naked in the ponds, dancing with the wind and

finding a fig tree where I could come with my partner to make love. Nature was home.

The Wolves, the M oon and I (age 24-26)

After having finalized my B.A in Ecology, I joined a nature conservation

research project that aimed at studying and protecting the Golan Heights wolves. As

the wolf population grew in the area, more and more cattle were attacked by them and

damaged the farmers' income. As a result, the farmers tried to kill the wolves by

poisoning them, an illegal act that jeopardized the entire food-chain of the Golan

Heights and the vulture population in particular. The research was carried out in order

to study the wolfs ecology and behaviour, while finding ways to protect the cattle. I

was involved in the first section of the project. My role was to collect data on the

wolves, analyze it and then recommend a conservation policy. Since wolves can move

very fast through harsh terrain and as they are very shy, the only way to 'watch' them

is by putting a radio transmitter on their necks and follow them from a jeep while

continually spotting them through the radio-telemetry receiver. Doing research on

animals active at night changed my entire life style. Each trucking started by spotting

a particular radio-marked wolf 2-3 hours before sunset, when I also tried to make eye

contact with the wolf and the pack, collect behavioural data and then continue

following the pack until 2-3 hours after sunrise, at which time I could sometimes

come into eye contact with them again and conclude the observation. Those two years,

were very special for me as they gave me a chance to get into the wilderness as I have

never done before. Alone with the moon, following the wolves, the path finders of

mythological wolf power in the North American heritage (Sams & Carson, 1988),

made me encounter aspects of my personality of which I had never before been aware.

Living in a form of isolation and separation, away from my family, friends and my

girl friend (a two-year relationship that did not last through the 'wolf period') allowed

me to strip off the symbols of culture and simply be me: to dance with the trees, sing

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

24

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

with the birds and cry with the wolves. Joining the wolves on an everyday basis,

knowing them as if I was a pack member, allowed me to be part of their cycle, join in

feeling their pain and death and celebrate their communal play and birth, identifying

with the stories of life and death. It made me accept some of my own, parallel stories,

and relate to them from a holistic point of view; addressing them as part of the ever

lasting cycle. As most of the experiences I encountered during this time were non

verbal, it is hard for me to name specific elements that the wolves touched within me.

I can say that they relate to my deep, spiritual or mystical aspects. It is clear that my

experience with them has changed my perception of life and my choices of how to

live. They say that if you meet a wolf eye to eye, you will never forget him. Most of

the eyes I met have already died; all of them continue to live on within ...

On the morning of the 3rd of July 1996,1discovered a massive poisoning in the

north-east zone of the Golan Heights. More than 40 vultures died, as well as many

other mammal predators (jackals, foxes, wild boar...). No wolf was found dead.

Thought I had warned the authorities previously as to the possibility of such an event,

I saw it happening, and was unsuccessful in preventing it. Heartbroken and in despair,

I left the research, packed up my jeep and left the Golan Heights.

Dance and Drama - In Search o f Non-verbal Expression and Healing

(age 25-29)

During the years I spent with the wolves, I continued to facilitate groups in

nature. I was working for the Nesia Institute, an organization that works on personal

development in a style that facilitates the integration of art, Jewish text, heritage and

work in nature in order to explore identity issues. During one of these projects, I

participated in a Contact Improvisation workshop led by Arye Bursztyn. It felt

wonderful to dance, touch and be touched; to be in my body and have Arye as a gentle

yet present witness. Following my instincts, I found myself driving once a week to his

contact improvisation classes in Tel-Aviv. I was drawn to his non-judgmental,

containing, allowing, creative, modest and generous way of 'space giving' (I use this

phrase as it describes my sense of his teaching style). I joined Arye's two-year New

Dance training, which led to the co-founding of an independent improvisation dance

group, and to performing. Contact Improvisation emerged as an artistic-social-

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

25

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

political-embodied dance form, protesting against the aesthetic orientation of modem

dance forms and individualistic life style. It had a strong social aspect embedded in its

physical form: two people dancing together keeping constant physical touch, its

central core resembling that of a Jam session. Contact Improvisation focuses around

the physical concept of gravity and momentum, 'being in the moment' and creating an

improvised reality. It emphasizes the fluidity and authenticity of movement rather than

its aesthetics. As such, it combines elements from martial arts (such as Chi-Kong,

Aikido and Tai-Chi), soft body work (Feldenkrais and Yoga) and modem dance

techniques, with philosophical ideas of the peace movement that emerged in the

seventies in the U.S.A. Entering the world of Contact Improvisation allowed me to

find a concrete, physical dance form in which I could express myself creatively, find

people I liked and develop myself as a dancer, without requiring the conventional

dance scene (dressing up, going to parties, being in the studio a specific amount of

time before performing, studying with these teachers or those...). In addition, the

relationship shared with Arye was very meaningful and inspiring for me. Although he

was a Gestalt therapist, we never had a therapeutic contract and remained dance

teacher and student. Nevertheless, it was one of the most therapeutic relationships I

ever had...

With Arye's support I started a three year post-graduate Drama Therapy

training at Tel Hai College, discovering the therapeutic impact of the fantastic ('as if)

reality; creative and non-verbal modes of work, and the power of group work and

rituals. The intensive training gave me a framework for working as a therapist, as well

as allowing me to go through a meaningful personal process connecting to my

strength and abilities: dance, drama and imagination, and apparently, group work. In

addition, Professor Mooli Lahad (one of the pioneers of Drama Therapy, founder of

the Six-Piece Story Making technique and the BASICPH approach; author of Creative

Supervision) was my teacher for 3 years. He supported my creative and spontaneous

mode of working, while confronting my objections to Drama Therapy theory and to

working within its classical framework. In fact, he nearly threw me out of his training,

as he did not approve of the ways I incorporated Contact Improvisation ideas into

Drama Therapy, claiming that I should first become an efficient Drama Therapist and

only then make the 'strange' combinations I did while studying (a rational claim that I

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

26

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

can now totally agree with). I found meaning and I loved the studies - it was the first

time I was able to complete a course in academic training without my mother's

intervention.

Throughout this period, I deepened my experience and knowledge in

body therapy and Contact Improvisation dance. I participated in advanced workshops

around the world, teaching and performing, and was very active in the forming of a

Contact Improvisation community in Israel. This activity included the formation of the

Israeli Contact Improvisation teacher's laboratory meetings, and later on, experimental

laboratories exploring the links between Contact Improvisation and psychotherapy

(funded by the BI ARTS project conducted by the British Council in Israel, 2002).

The combination of Drama Therapy and Contact Improvisation dance, both

integrative disciplines challenged me to investigate ways in which I could integrate all

of my loves into one practice. Soon after I completed my Drama Therapy studies, I

started working as a Drama therapist. In this capacity, I met Joseph, an autistic child

who did not want to enter the clinic and asked me to join him for walks in nature...

The experience with Joseph was in many ways the 'gateway' into my journey towards

the creation of Nature Therapy and the writing of the current Ph.D. (More about the

work with Joseph can be found in Berger and McLeod, 2006; Appendix 3)

Nature - M y Therapeutic Space (within the sam e ages o f 25-29)

After I left wolf research, I moved to Snir, a small kibbutz, located between

the Golan Heights and the Hula Valley, just above the beautiful Banias River reserve.

It enabled me to see the Golan Heights, yet, not be 'in it'. It also allowed me a unique

chance to get to know the Banias River, a 5 minute walk from my home. I gradually

formed a specific way of living: waking up with sunrise, going to the river, doing

body work that involved direct contact with nature (such as dancing with the wind,

climbing a tree), meditating, swimming in the river and returning home. Then, when I

came back from school or work, I went to the river once again, taking some time for

reflection and going for a last swim. Thinking of it now, it seems that these repetitive

activities gave me a sense of order in life, while providing personal time to adjust to

the changes they contained. During my Drama Therapy training, the time I spent at the

river have provided a safe space for 'self reflection', where I could make my own

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

27

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

meaning, as opposed to the meanings and interpretations that were given to me by my

Drama Therapy teachers and supervisors. The private time I spent in the Banias

included physical (and meta-physical) experiments, exploring the impact that direct

contact with nature had upon my sensations, dreams and images, and my overall

perception of life. They included explorations such as sleeping on a tree or in a cave,

spending time inside hollow trees, crawling, walking naked with blindfolds over my

eyes, as if to make sense of the world, and spending time hanging (using sling

rappelling gear) above the big water fall. Due to these explorations, my sensory and

metaphysical awareness changed. I could hear and sense things I had never heard

before. At times, I felt as if the trees were watching me... in fact I became aware of

strange sensations that presented themselves after sunset, including a new sense of

fear emanating from nature. Some spots in the reserve felt friendly and loving while

others felt angry and dangerous. Such intimate relationship with the river did not only

change my concrete knowledge and discovery of things such as eagle and owl nests

and the badger's den, it also changed my perception of my being. I could identify with

things I never even knew existed before. I was able to sense things that happened in

the past and that could happen in the future.

This is the first time I am trying to put these elements into writing and share

them with people. It feels strange. Trying to use the academic knowledge I have

acquired towards the end of writing this Ph.D., I would say that it seems these

experiments expanded my 'ecological self and helped me engage with a wider cosmic

knowledge (Berger & McLeod, 2006). I presume that the tacit knowledge I found on

the river underlines my faith and my confidence in facilitating, teaching and

developing Nature Therapy.

As part of my final assignment for the completion of my Drama

Therapy training, I wrote a paper entitled 'Nature Therapy', in which I offered a draft

of a therapeutic, nature-oriented model. Based on this theme, I designed a pilot

programme titled: 'Encounter in Nature', which later operated in schools and was

granted the Ford Foundation Reward in 2002.

Becoming and Being a Father (29 - present)

I met Lilach, an energetic educational and clinical psychologist, who used to

water the floor along with watering the flowers in her clinic, while being supervised

for my work on the 'Encounters in Nature' programme. Things developed in

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

28

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

surprising ways, and we decided after our second supervision meeting to change our

contract, depart supervision and begin dating. A short time later Lilach became

pregnant, and I was shocked. I was accustomed to a bachelor's individualistic life

style (ever since my second year with the wolves), and the thought of entering a

serious relationship, not to mention becoming a father, was inconceivable. Not finding

answers to questions which popped up, I turned back to nature. This time, four years

after having left the wolves and the Golan Heights, I headed back, straight to the

hideout above the gorge in which I used to watch Kern's den, pack and puppies. After

a sleepless night, calling out to them and receiving no answer, I realized they were no

longer there. I went down to the actual location of the den. Recognizing familiar

objects, such as an old shoe the puppies used to play with, I squeezed my way into the

den and fell into a deep sleep. Several hours later, climbing up the cliff I saw them, as

if they had been waiting for me all this time. We said goodbye - and I had received

my answer. I was apparently ready to become the 'Alfa male' of a human pack, my

very own family...

A few months later, Alon (Hebrew for oak tree) was bom and

following Lilach's request, we moved to her kibbutz to receive her family's support.

Paradoxically enough, my Ph.D. journey started with Alon's birth, as, several months

later, I took my first trip to Sheffield Hallam University in England, to work on the

draft of a research proposal. Things got very hectic as I tried to juggle my role as an

involved father who spends time with his child, while simultaneously stmggling to

undertake a Ph.D., run a new therapeutic programme, make a living and continue to

dance. Going into counseling, working with a Jungian 'father figure' therapist helped

me articulate this new situation. I found myself using 'a human therapist' to work

through issues dealing with intrapersonal issues and relationships. In addition, this

experiment taught me something about Jungian psychology, and opened up another

dimension of Drama Therapy's use of symbols and archetypes. My daughter Neta

(Hebrew for sapling) was bom two years later, while I had moved my Ph.D. studies

from Sheffield to Dundee, together with the opening of the first post-graduate Nature

Therapy training. As I was more confident in the role of father it was easier at first,

until, a few months later, Lilach went into a post-birth depression. I was a heavy

assignment to manage everything; emotionally containing Lilach and acknowledging

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

29

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

that we were not immune from such a phenomenon. This process had a major impact

upon our life as we realized the personal and family price we paid for our chase after

money, honour and success. A year and a half later, having received help our life

changed once again. Lilach emerged from the depression, stronger and more

connected to her strength. Ever since this episode, I am much more aware of the way I

navigate my post-modern life style, trying to make choices that allow me to keep a

balance between the different roles and demands in life. Living so close to nature

makes it easy to spend daily family time in nature, allowing my children the freedom

to experiment, play and create.

2.1.3 The Impact of Culture

As I started thinking of ways in which society and culture have shaped my life,

I immediately began writing in the sense of 'we' rather than as 'I'. Upon reflection it

seems as if I was educated and raised upon values which are common to most

middleclass, secular Israelis. Therefore, in this sub-Chapter, I will write as 'we' to

describe my interpretation of a collective identity. I will transfer back to 'I', as I try to

share the personal meanings I give to this larger context.

The Place o f Rituals and the Symbolic Place o f N ature in m y Life

Thinking of my identity in the cultural sense, I see myself first of all as an

Israeli and only then as a Jew. Being raised in a secular settlement and a non-religious

family, keeping Shabbat, eating kosher, going to synagogue, etc., had only minor role

in my life. At the same time, as Jewish culture, symbols, language and holidays are

strongly embedded in the collective Israeli identity and way of living, I am sure they

affected my personality on different levels of awareness. Most of the Jewish holidays

are correlated with nature's cycle, so it's hard not to be aware and influenced by this

human - nature relationship. The celebration of holidays in kindergartens and

preliminary schools include rituals that revolve around these concepts: On Tu Bishvat,

which marks the time of tree planting we plant trees, on Shavuot (Feast of Harvest) we

decorate our homes with the 'seven species', and during Succoth, which marks the

Israelites' journey from Egypt to the holy land, we live and sleep outdoors in tent-like

constructions made from wood and fabric, from which we can see the stars...

Berger, R. (2008). Nature Therapy - Developing a Framework for Practice. A Ph.D.

30

School o f Health and Social Sciences. University o f Abertay, Dundee

When I left my parents atheist home and worked in the Nesia Institute

(an organization working on personal development in a facilitation style that

integrates art, Jewish text, heritage and work in nature), I realized that traditional

rituals such as Sabbath songs and prayers contribute to my identity, help me

experience togetherness and get in touch with the power of the collective. I was

attracted to various aspects of this heritage, and when I came back to my secular

kibbutz and family, I found myself forming traditional rituals, maintaining their main

ideas and adapting them to secular and pluralistic thinking. For example, the

traditional Sabbath candle-lightning ritual, in which the woman lights candles, turned

into a ritual in which each person (including children and men) shared something from

the week that had passed and then each lit a candle. Reflecting on this process now

helps me understand the reason that Nature Therapy has been given such a ritualistic

orientation.

2.1.4 Connection to the Land

As an Israeli, the issue of land is very significant; the keeping and holding of

our land is embedded in our history and first and foremost, has an existential meaning.

A safe territory equals a safe life. I would venture to say that this is true for most

people around the world. However, it assumes an additional meaning for those who

belong to a nation whose spiritual well-being is embedded in the land; a nation that

was expelled from their land and won it back by war and have had to protect it ever

since. This connection to the land is also rooted in the Israeli educational system, as

each class (from the first grade) goes for 'getting to know the land' trips as part of the

yearly school syllabus. Youth movement activities are also connected to this concept,

reflected during their outdoor camps. In this sense, from my subjective standpoint, it

seems that the Israeli sense of connection to the land and the feeling of nationalism is

far stronger than those of people whose national narratives are less 'land-connected'. I

feel a strong sense of connection to this land: the landscape in which I grew up, live in