Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 27 (2017) 246–252

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ufug

Original article

Sustained effects of a forest therapy program on the blood pressure of office

workers

Chorong Songa,1, Harumi Ikeia,b,1, Yoshifumi Miyazakia,⁎

a Center for Environment, Health and Field Sciences, Chiba University, 6-2-1 Kashiwa-no-ha, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-0882, Japan

b Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, 1 Matsunosato, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8687, Japan

MARK

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Middle-aged adults

Physiological relaxation

Preventive medicine

Prolonged effects

Shinrin-yoku

Stress management

ABSTRACT

We examined the sustained effects of a forest therapy program on the blood pressure of office workers. Twenty-

six office workers (mean age ± standard deviation, 35.7 ± 11.1 years) participated in a 1-day forest therapy

program. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse rate were used as measurement indices. The evaluations

were performed three times before breakfast, lunch, and dinner 3 days before, during, and 3 and 5 days after the

forest therapy program. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure significantly decreased during the forest therapy

program relative to the value from 3 days before the program, and this decrease was maintained 3 and 5 days

after the forest therapy program. There were no significant differences in pulse rate. We then specifically focused

on nine participants whose systolic blood pressure was above 120 mmHg. For the measurement before dinner,

the systolic blood pressure significantly decreased (from 133.8 to 116.6 mmHg) during the forest therapy pro-

gram, and this decrease was maintained at 3 and 5 days after the program (126.4 and 124.0 mmHg, respec-

tively). A significant decrease in diastolic blood pressure (from 88.6 to 77.1 mmHg) was observed during the

forest therapy program. In conclusion, systolic and diastolic blood pressure decreased during the forest therapy

program and these decreases were maintained for 5 days.

1. Introduction

There are serious social concerns over health problems caused by

job stress. Job stress is defined as harmful physical and emotional re-

sponses that occur when the requirements of a job do not match the

capabilities, resources, or needs of the worker (National Institute for

Occupational Safety and Health, 1999). Over the past few decades,

more and more research has documented that job stress is associated

with a moderately elevated risk of adverse health outcomes, especially

cardiovascular-related adverse effects (Kang et al., 2005; Kivimäki and

Kawachi, 2015; Siegrist and Li, 2016).

According to a survey conducted in Japan (Ministry of Health,

Labour and Welfare, 2012), 60.9% of Japanese workers feel stress in

their jobs. This high stress state of workers has become an important

social issue and, therefore, the Japanese government launched a new

occupational health policy called the Stress Check Program to monitor

and screen for workers experiencing high psychological stress in the

workplace (Kawakami and Tsutsumi, 2016). It has become increasingly

important to seek solutions for people to cope with workplace stress in

Japan.

In recent years, there has been considerable and increasing atten-

tion on the use of forest environments as a setting for health promotion.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that forest environments mitigate

stress states and induce physiological relaxation (Tsunetsugu et al.,

2007; Park et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Park et al.,

2010; Lee et al., 2011; Tsunetsugu et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014). It is

well known that spending time in forest settings improves immune

function and that these effects last for about 1 month (Li et al., 2007; Li

et al., 2008a, 2008b). From the psychological aspect, the restorative

effects of forest environments related to psychological stressors or

mental fatigue and improved mood states and cognitive function have

been reported (Morita et al., 2007; Shin et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011;

Shin et al., 2011).

The idea of “forest therapy” has been proposed in accordance with

the results of the above studies. The aim of evidence-based “forest

bathing (shinrin-yoku)” is to induce preventive medical effects to im-

prove weakened immune function and prevent diseases by achieving a

state of physiological relaxation through exposure to forest-origin sti-

muli (Song et al., 2016). Forest therapy is now increasingly recognized

as an effective relaxation and stress management tool that has been

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: crsong1028@chiba-u.jp (C. Song), ikei0224@ffpri.affrc.go.jp (H. Ikei), ymiyazaki@faculty.chiba-u.jp (Y. Miyazaki).

1 These authors contributed equally to this work.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.08.015

Received 7 April 2017; Received in revised form 21 August 2017; Accepted 21 August 2017

Available online 01 September 2017

1618-8667/ © 2017 The Authors. Published by Elsevier GmbH. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/BY/4.0/).

C. Song et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 27 (2017) 246–252

demonstrated to be an effective preventive or alternative therapy

(Frumkin, 2001; Lee et al., 2012), and its effects have been studied in

elderly individuals and adults at risk of stress- and lifestyle-related

diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and depression (Ohtsuka

et al., 1998; Mao et al., 2012; Shin et al., 2012; Sung et al., 2012; Lee

and Lee, 2014; Kim et al., 2015; López-Pousa et al., 2015; Ochiai et al.,

2015; Song et al., 2015a; Chun et al., 2017; Song et al., 2017).

The preventive medical effects induced by forest environments are

increasingly being recognized; however, there is a lack of research on

how long these effects last. The aim of the present study was to clarify

the sustained effects of a forest therapy program on the blood pressure

of office workers. We specifically focus on participants whose systolic

blood pressure (SBP) was above 120 mmHg because recent research

indicates that lowering SBP to less than 120 mmHg can significantly

reduce the rates of major cardiovascular events and death from any case

(The SPRINT Research Group, 2015).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. All participants (N = 26)

The participants were employees from a company that aims for

regional creation with information technology from Tottori Prefecture.

Twenty-six office workers aged 19–56 years (male: 14, female: 12,

mean age ± standard deviation: 35.7 ± 11.1 years; Table 1) partici-

pated in this study.

With respect to recruitment, we posted study information on an

office bulletin board. Those who wished to participate in the study

applied via e-mail. All participants were thoroughly informed regarding

the aims and procedures of the study. After receiving a description of

the experiment, they signed an agreement to participate in the study.

During the study period, the consumption of alcohol, caffeine, and to-

bacco was prohibited. Participants were asked to perform normal life

activities on the days before and after participating in the forest therapy

program. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Center for Environment, Health and Field Sciences, Chiba

University, Japan (Project identification code number: 5).

2.1.2. Higher than 120 mmHg group (N = 9)

Of the 26 participants, we focused on 9 participants (male: 8, fe-

male: 1, mean age ± standard deviation: 37.4 ± 10.0 years) whose

SBP was above 120 mmHg, as measured before dinner, at the office and

3 days before participating in the forest therapy program. We named

this group as the “higher than 120 mmHg group.”

2.2. Experimental sites

The forest therapy programs were conducted in Chizu, Tottori

Prefecture, which is located in the Chūgoku region in Japan. More than

90% of the total area of this region is covered by forests and forestry

and timber processing are its main industries. The experimental site of

Table 1

Participant demographics.

Parameter

Mean ± standard deviation

Total sample number

Age (years)

Height (cm)

Weight (kg)

BMI (kg/m2)

All participants

26

35.7 ± 11.1

164.7 ± 8.6

60.7 ± 10.7

22.3 ± 3.1

Males

14

35.3 ± 10.6

170.1 ± 6.2

66.9 ± 10.8

23.1 ± 3.5

BMI: Body mass index.

Females

12

36.2 ± 12.2

158.4 ± 6.4

53.4 ± 3.8

21.4 ± 2.4

the present study (hereafter referred to as the forest area) was certified

as a forest therapy base in 2010 and it is a mixed forest mostly com-

posed of cedar and hardwood. Annually, around 1400 forest therapy

tourists visit this town (as of April 2015).

It was sunny on the days on which the forest therapy program was

run and the mean temperature, humidity, and intensity of illumination

in the forest area were 18.7 ± 3.3 °C, 65.3 ± 9.8%, and

2097 ± 1910 lx, respectively.

2.3. Measurement

SBP, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and pulse rate were used as

physiological measurement indices. A digital blood pressure monitor

using oscillometric methods (HEM1020; Omron, Kyoto, Japan) was

used to measure the blood pressure and pulse rate in the right upper

arm. Participants rested in a seated position for 5 min and then mea-

sured their blood pressure and pulse rate twice, with their arm placed

on top of a desk. Desks and chairs of the same size were used in all

measurements. In the case of discrepancies in SBP exceeding 10 mmHg

and/or DBP exceeding 6 mmHg between two measurements, an addi-

tional measurement was taken. The mean of two or three measurements

was used in the analysis.

2.4. Experimental design

Before joining the forest therapy program, the 26 office workers

attended an orientation in the meeting room of their office on

September 3, 2014. The participants were randomly assigned to three

groups of eight, ten, and eight individuals, and these three groups

participated in the forest therapy program on September 13, and

October 11 and 18, 2014, respectively.

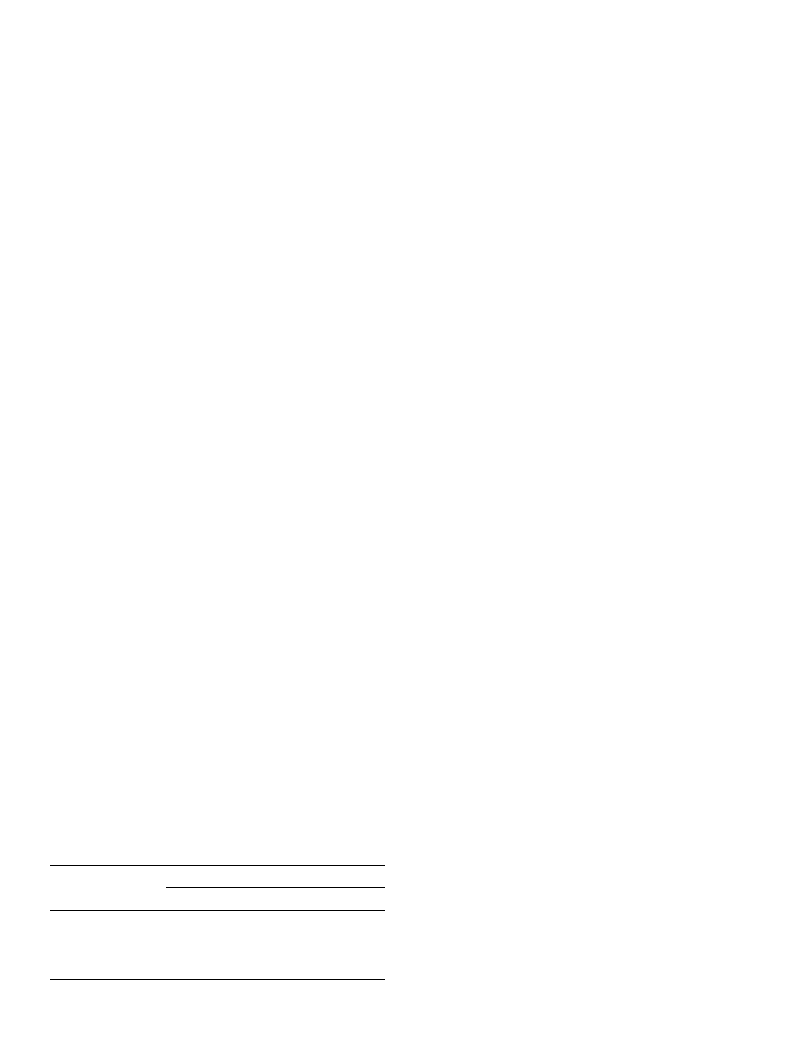

To investigate the changes in the physiological response of the

participants to the forest therapy program over time, the physiological

measurements were taken 3 days before, during, and 3 and 5 days after

the program (Fig. 1). The measurements were taken three times before

breakfast, lunch, and dinner on each assessment day. The measurement

time was based on the timing of the forest therapy program; the par-

ticipants’ blood pressure (SBP and DBP) and pulse rate were measured

before breakfast (about 7:00, before participation in the program),

before lunch (12:30), and at the end of the program (about 15:00).

These measurements were also taken at the same time of day 3 days

prior to the forest therapy program and 3 and 5 days after the program

in their home and/or office using desks and chairs of the same size.

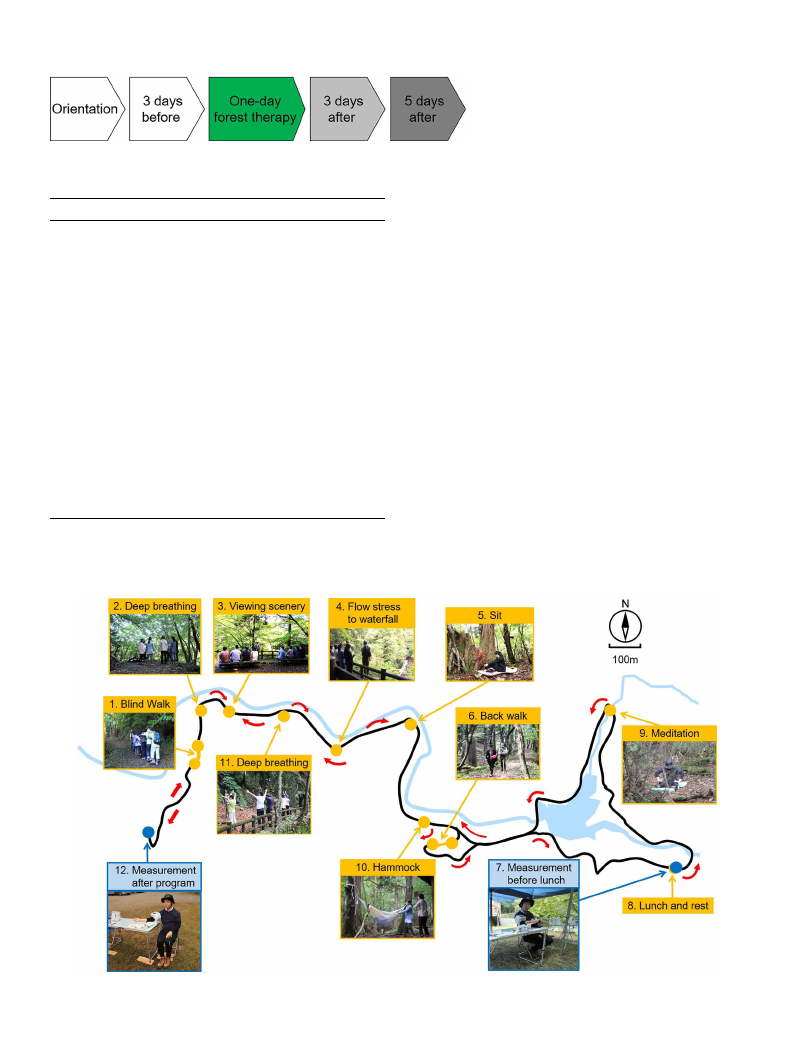

On the morning of the forest therapy program, the participants

gathered at the parking area near the entrance of the “forest therapy

road” at 8:50 and joined in the forest therapy program as a group with a

guide. The program consisted of multiple timed activities over about

6 h, 12 min, with a walking distance of 4265 m, and included time for

lunch and the physiological measurements. Table 2 shows the details of

the forest therapy program on September 13. The programs were con-

ducted following the same procedure at approximately the same times

for all three groups.

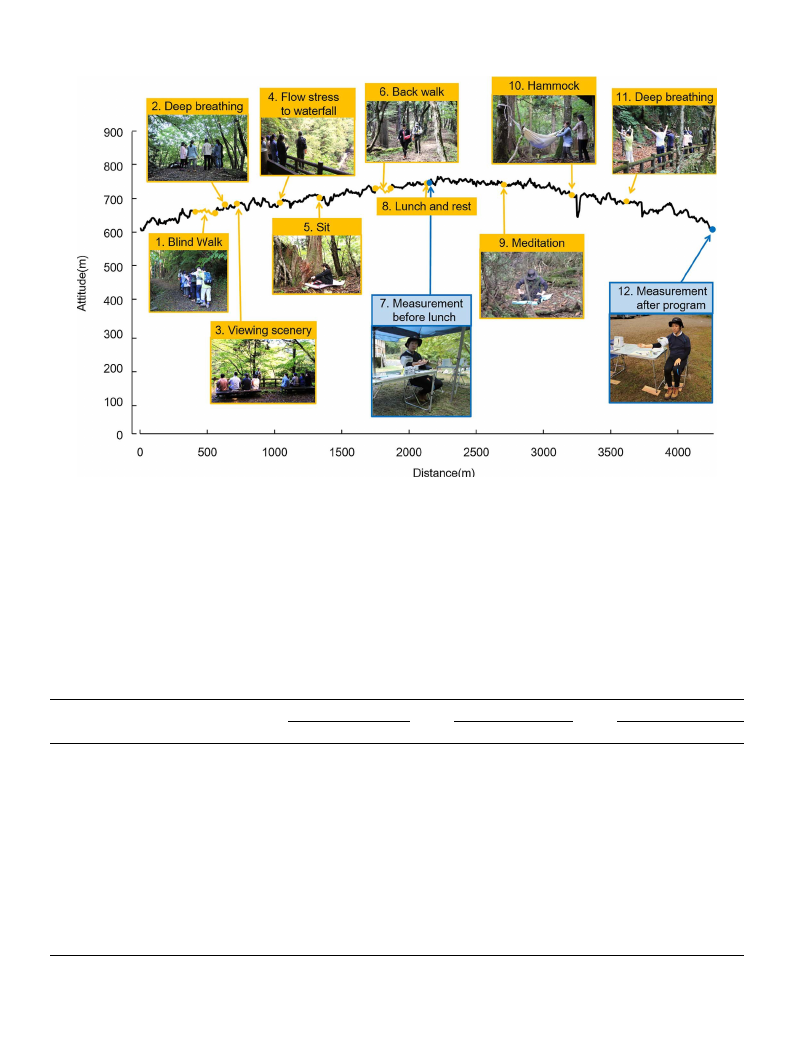

The program and altitude map of the course showing the various

activities in the forest therapy program are shown in Figs. 2 and 3,

respectively. This data was obtained using an offline map-caching GPS

application (Geographica, Japan).

2.5. Data analysis

The data were summarized in terms of the mean value before

breakfast, lunch, and dinner 3 days before, during, and 3 and 5 days

after the forest therapy program. Furthermore, average daily measures

were also examined.

SPSS software (V20.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for

all statistical analyses. For all comparisons, p < 0.05 was considered

statistically significant. A paired t-test with Holm correction was used to

247

C. Song et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 27 (2017) 246–252

Fig. 1. Experimental schedule.

Table 2

Schedule of the various activities in the forest therapy program.

Time

Event

Number in Figs. 2 and 3

09:18–09:20 Brief explanation about the program –

09:21–09:26 Preparation stretches

–

09:27–09:48 Walking to the forest area

–

09:49–09:51 Blind walking

1

09:52–09:54 Stroll in the forest

–

09:55–10:02 Deep breathing

2

10:03–10:06 Stroll in the forest

–

10:07–10:26 Viewing scenery & lecture

3

10:27–10:37 Stroll in the forest

–

10:38–10:47 Flow stress to waterfall

4

10:48–10:54 Stroll in the forest

–

10:55–11:22 Sitting & lying down in the forest

5

11:23–11:33 Stroll in the forest

–

11:34–11:48 Back walk

6

11:49–12:01 Stroll in the forest

–

12:02–12:35 Rest & measurements before lunch

7

12:36–13:16 Lunch & rest

8

13:17–13:52 Stroll in the forest

–

13:53–14:09 Meditation

9

14:10–14:25 Stroll in the forest

–

14:26–14:37 Hammock

10

14:38–14:54 Stroll in the forest

–

14:55–14:58 Deep breathing

11

14:59–15:10 Stroll in the forest

–

15:11–15:30 Rest & measurements after program

12

compare the physiological measurements obtained during and 3 and

5 days after the forest therapy program with those taken 3 days before

the program (baseline); therefore, Holm correction was applied three

times. Regarding the smallest p value, the adjustment is the same as the

Bonferroni correction for the three outcome measures being analyzed,

resulting in a corrected significance level that was set at a p value of

0.017 (=0.05/3). If the smallest p value is > 0.017, the process stops,

but if it is smaller, the next smallest p value is divided by 2 (p = 0.025).

The process continues in a similar manner if that p value is significant,

with the next smallest value being divided by 1 (p = 0.050).

One-sided tests were used because of the hypothesis that the par-

ticipants would be physiologically relaxed by the forest therapy pro-

gram.

3. Results

The participants showed significantly lower blood pressure during

and following the 1-day forest therapy program than in their everyday

life (3 days before participating in the program), and these decreases

lasted for at least 5 days.

3.1. All participants (N = 26)

The overall results are summarized in Table 3. Regarding SBP

measured before breakfast, compared with the mean value from 3 days

before (baseline: 114.2 ± 2.3 mmHg), the mean value significantly

decreased on the day of the forest therapy program

(110.1 ± 2.2 mmHg, p < 0.05), 3 days after (107.7 ± 2.7 mmHg,

p < 0.05), and 5 days after (107.9 ± 2.5 mmHg, p < 0.05). In terms

of the SBP measurements taken before dinner, compared with the mean

measurements taken 3 days before (baseline: 115.5 ± 3.1 mmHg), the

mean value also significantly decreased on the day of forest therapy

Fig. 2. Schematic with images showing the various activities in the forest therapy program.

248

C. Song et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 27 (2017) 246–252

Fig. 3. Altitude map with images showing the various activities in the forest therapy program.

(106.5 ± 2.4 mmHg, p < 0.05). No significant difference was ob-

served for the measurements taken before lunch. For the average daily

measures, compared with the mean value from 3 days before (baseline:

114.8 ± 2.7 mmHg), the mean value significantly decreased on the

day of the forest therapy program (109.1 ± 2.2 mmHg, p < 0.05),

3 days after (111.5 ± 2.6 mmHg, p < 0.05), and 5 days after

(110.7 ± 2.6 mmHg, p < 0.05).

For DBP measured before breakfast, compared with the mean value

from 3 days before (baseline: 75.6 ± 2.1 mmHg), a significant

decrease was found 3 days (70.5 ± 2.0 mmHg, p < 0.05) and 5 days

after the forest therapy program (72.4 ± 1.9 mmHg, p < 0.05). The

mean value on the day of forest therapy (73.3 ± 2.0 mmHg) appeared

to be lower than the baseline value; however, no significant difference

was observed. For the DBP measurements taken before dinner, com-

pared with 3 days before (baseline: 73.5 ± 2.8 mmHg), the mean

value also significantly decreased on the day of forest therapy

(68.3 ± 2.1 mmHg, p < 0.05). No significant difference was ob-

served for the DBP measurements taken before lunch. For the average

Table 3

Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse rate measurements taken at different measurement times.

Measurement time

SBP (mmHg)

DBP (mmHg)

Before breakfast

Before lunch

Before dinner

Mean

3 days before

Forest therapy day

3 days after

5 days after

3 days before

Forest therapy day

3 days after

5 days after

3 days before

Forest therapy day

3 days after

5 days after

3 days before

Forest therapy day

3 days after

5 days after

Mean ± SE

114.2 ± 2.3

110.1 ± 2.2

107.7 ± 2.7

107.9 ± 2.5

114.5 ± 3.4

110.7 ± 2.8

112.6 ± 2.7

112.0 ± 3.0

115.5 ± 3.1

106.5 ± 2.4

114.3 ± 3.2

112.2 ± 2.8

114.8 ± 2.7

109.1 ± 2.2

111.5 ± 2.6

110.7 ± 2.6

p value

–

0.025*

0.001*

0.000*

–

0.025

0.388

0.199

–

0.001*

0.519

0.062

–

0.000*

0.009*

0.001*

Mean ± SE

75.6 ± 2.1

73.3 ± 2.0

70.5 ± 2.0

72.4 ± 1.9

75.8 ± 2.6

73.5 ± 2.2

73.8 ± 2.2

72.5 ± 2.6

73.5 ± 2.8

68.3 ± 2.1

72.4 ± 2.7

73.8 ± 2.3

75.0 ± 2.3

71.7 ± 1.9

72.2 ± 2.1

72.9 ± 2.1

SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure, SE: Standard error.

N = 26, mean ± SE.

* p < 0.05 by paired t-test (one-sided) with Holm correction.

249

p value

–

0.103

0.000*

0.003*

–

0.062

0.164

0.033

–

0.010*

0.524

0.854

–

0.003*

0.011*

0.044*

Pulse rate (bpm)

Mean ± SE

71.0 ± 2.2

70.6 ± 1.8

69.4 ± 2.0

71.0 ± 1.8

70.4 ± 2.0

71.3 ± 2.2

73.3 ± 2.0

72.5 ± 1.6

75.0 ± 2.3

76.5 ± 2.4

77.7 ± 2.5

74.8 ± 2.1

72.1 ± 2.0

72.8 ± 2.0

73.5 ± 2.0

72.8 ± 1.6

p value

–

0.735

0.199

0.988

–

0.560

0.025

0.171

–

0.311

0.024

0.926

–

0.555

0.083

0.548

C. Song et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 27 (2017) 246–252

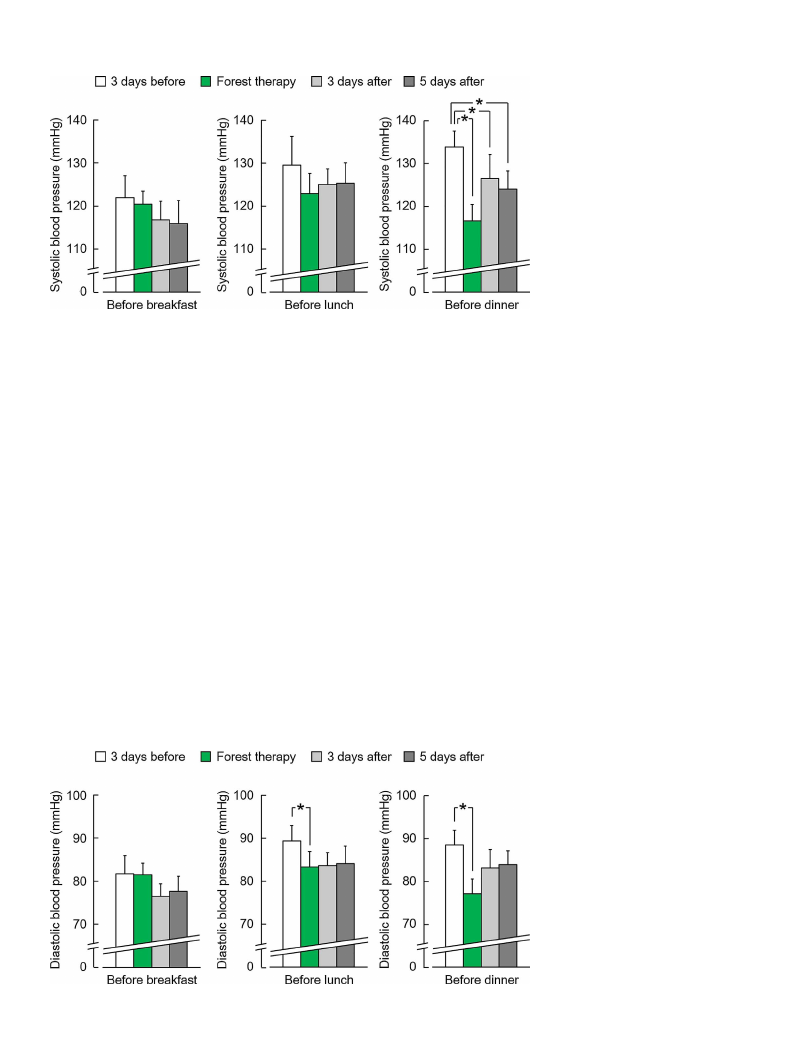

Fig. 4. Systolic blood pressure measurements taken

before breakfast, lunch, and dinner in the “higher

than 120 mmHg group.”.

N = 9, mean ± SE, *p < 0.05 by paired t-test

(one-sided) with Holm correction.

daily measures, compared with the mean value from 3 days before

(baseline: 75.0 ± 2.3 mmHg), the mean value significantly decreased

on the day of the forest therapy program (71.7 ± 1.9 mmHg,

p < 0.05), 3 days after (72.2 ± 2.1 mmHg, p < 0.05), and 5 days

after (72.9 ± 2.1 mmHg, p < 0.05).

Further, no significant differences were found in the pulse rate for

any of the measurements.

3.2. Higher than 120 mmHg group (N = 9)

Similar results were obtained in the “higher than 120 mmHg

group.” The SBP results are shown in Fig. 4. For the results before

dinner, compared with the mean value from 3 days before (baseline:

133.8 ± 3.7 mmHg), the mean values significantly decreased on the

day of forest therapy (116.6 ± 3.8 mmHg, p < 0.05), 3 days after

(126.4 ± 5.5 mmHg, p < 0.05), and 5 days after

(124.0 ± 4.2 mmHg, p < 0.05). No significant difference was ob-

served for the measurement before breakfast (3 days before:

122.0 ± 5.1 mmHg; on the day of forest therapy: 120.4 ± 3.1 mmHg;

3 days after: 116.8 ± 4.3 mmHg; 5 days after: 115.9 ± 5.4 mmHg,

p > 0.05) or before lunch (3 days before: 129.6 ± 6.7 mmHg; on the

day of forest therapy: 122.9 ± 4.7 mmHg; 3 days after:

125.1 ± 3.7 mmHg; 5 days after: 125.4 ± 4.2 mmHg, p > 0.05).

For the average daily measures, compared with the mean value from

3 days before (baseline: 128.4 ± 4.9 mmHg), the mean value sig-

nificantly decreased on the day of the forest therapy program

(120.0 ± 3.3 mmHg, p < 0.05), 3 days after (122.8 ± 4.2 mmHg,

p < 0.05), and 5 days after (121.8 ± 4.6 mmHg, p < 0.05).

Fig. 5 shows the DBP results for the “higher than 120 mmHg group.”

For the results before lunch, compared with 3 days before (baseline:

89.4 ± 3.6 mmHg), the mean value also significantly decreased on the

day of forest therapy (83.3 ± 3.6 mmHg, p < 0.05). For the mea-

surements taken before dinner, compared with 3 days before (baseline:

88.6 ± 3.4 mmHg), the mean value also significantly decreased on the

day of forest therapy (77.1 ± 3.4 mmHg, p < 0.05). There were no

significant differences for the measurements taken before breakfast

(3 days before: 81.9 ± 4.2 mmHg; on the day of forest therapy:

81.7 ± 2.7 mmHg; 3 days after: 76.6 ± 2.9 mmHg; 5 days after:

77.8 ± 3.5 mmHg, p > 0.05). For the average daily measures, com-

pared with the mean value from 3 days before (baseline:

86.6 ± 3.4 mmHg), the mean value significantly decreased on the day

of the forest therapy program (80.7 ± 2.9 mmHg, p < 0.05), 3 days

after (81.1 ± 3.2 mmHg, p < 0.05), and 5 days after

(82.0 ± 3.4 mmHg, p < 0.05).

For the pulse rate results, no significant differences were found for

any of the measurements.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the sustained effects of a forest therapy

program on the blood pressure of office workers. The results indicated

that blood pressure significantly decreased during the forest therapy

program relative to the value measured 3 days before participation in

the program, and that this decrease was maintained at 3 and 5 days

after the program.

Moreover, we demonstrated the same effect in the “higher than

Fig. 5. Diastolic blood pressure measurements taken

before breakfast, lunch, and dinner in the “higher

than 120 mmHg group.”.

N = 9, mean ± SE, *p < 0.05 by paired t-test

(one-sided) with Holm correction.

250

C. Song et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 27 (2017) 246–252

120 mmHg group.” From the literature, blood pressure levels of ≥140/

90 mmHg are regarded as hypertension, 130–139/85–89 mmHg as high

normal blood pressure, 120–129/80–85 mmHg as normal blood pres-

sure, and < 120/80 mmHg as optimal blood pressure (Shimamoto

et al., 2014). However, the optimal blood pressure remains con-

troversial and recent research has revealed that lowering SBP to a target

goal of less than 120 mmHg, as compared with the standard goal of less

than 140 mmHg, results in lower rates of major cardiovascular events

and death from any case (The SPRINT Research Group, 2015). In the

before dinner measurement of the “higher than 120 mmHg group,” we

detected a dramatic reduction in blood pressure, which was sustained.

Compared with the value from 3 days before (baseline:

133.8 ± 3.7 mmHg), SBP significantly decreased by 17.2 mmHg

(12.8%) on the day of the forest therapy program by 7.3 mmHg (5.5%)

3 days after and by 9.8 mmHg (7.3%) 5 days after. Further, DBP sig-

nificantly decreased by 11.5 mmHg (12.9%) on the day of the forest

therapy program compared with 3 days before (baseline:

88.6 ± 3.4 mmHg). The mean blood pressure from 3 days before the

program, which was assumed to be the same as each participant’s

average daily blood pressure, was high for both SBP (133.8 mmHg) and

DBP (88.6 mmHg). After forest therapy, SBP decreased to 116.6 mmHg

and DBP decreased to 77.1 mmHg, indicating a remarkable effect.

On the other hand, a sustained reduction in SBP was observed in the

before breakfast measurement in the all participants group, but it was

detected in the before dinner measurement in the nine participants with

high SBP. Looking at SBP results from 3 days before the forest therapy

program, there were no significant differences in the values obtained

before breakfast (114.2 mmHg), lunch (114.5 mmHg), and dinner

(115.5 mmHg) in all participants. However, when we separate out the

nine participants with high SBP, we observed values that gradually

increased from before breakfast (122.0 mmHg), to lunch

(129.6 mmHg), and dinner (133.8 mmHg). It is possible that work-re-

lated stress was reflected in the measures of the high-SBP group.

Because the value before dinner was high, it appears that the effect of

forest therapy was remarkable. The mechanism that explains different

results between the 26 participants and the 9 participants with high SBP

are unknown. These would be important topics for examination during

future research. In addition, we focused on participants who actively

experienced stress. We consequently obtained evening measures of SBP,

which is the time when most daily work stressors end. Although we

used data that was measured only for 1 day, future studies should ex-

amine participants with sustained high blood pressure in the evening.

Some of the results from the present study are consistent with those

of previous studies, which showed decreases in blood pressure as a

result of various types of contact with forest environments, such as only

15 min walking in and/or viewing forests (Tsunetsugu et al., 2007; Lee

et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Park et al., 2010) and participation in

forest therapy programs for 1 day (Ochiai et al., 2015), 3 days (Sung

et al., 2012), and 7 days (Mao et al., 2012). These findings suggest that

forest environments can significantly lower blood pressure.

Because job stress is known to be associated with a moderately

elevated risk of adverse health outcomes, especially cardiovascular-re-

lated outcomes (Kang et al., 2005; Kivimäki and Kawachi, 2015;

Siegrist and Li, 2016), proper management and prevention of stress are

thought to be important to health. We believe that participation in

forest therapy programs can be an effective and beneficial method for

stress management and health promotion in office workers. In the fu-

ture, it will be necessary to study the mechanism and factors in the

forest that bring about these effects, as well as how to the forest en-

vironment can be used to optimize physiological benefits

Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to

urban green spaces, which provide a natural environment that is ac-

cessible for most people in modern society, has a positive effect on

perceived general health (Takano et al., 2002; Maas et al., 2006) and a

brief walk in an urban park can induces parasympathetic nervous ac-

tivity that is enhanced in relaxed state, suppresses sympathetic nervous

activity that is enhanced in stressful state, and decrease the heart rate,

regardless of the season (Song et al., 2013, 2014, 2015b). Because the

development of urban green spaces is a simple and accessible method of

improving health and quality of life, there is a need to clarify the

physiological influence and sustainable effects of urban green spaces.

The present study provides evidence of the sustained effects of a

forest therapy program on the blood pressure of office workers.

However, this study has several limitations. First, it lacks a control

group performing similar activities in an urban environment. Second,

the only analysis variables were blood pressure and pulse rate; there-

fore, future studies should determine the effects of the forest environ-

ment using other physiological indices. Third, we only measured the

blood pressure of the office workers for up to 5 days after participation

in the program. Thus, future studies should measure the physiological

effects of the program 7–10 days after participation.

5. Conclusions

Regarding the sustained effects of the forest therapy program on the

blood pressure of office workers, our study findings revealed the fol-

lowing: (1) blood pressure decreased during the forest therapy program

and (2) this decrease continued for 5 days. In conclusion, the forest

therapy program reduced the blood pressure of office workers and these

effects were sustained for 5 days.

Author contributions

Chorong Song contributed to the experimental design, data acqui-

sition, statistical analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript

preparation. Harumi Ikei contributed to the experimental design, data

acquisition, statistical analysis, and interpretation of results. Yoshifumi

Miyazaki conceived and designed the study and contributed to the data

acquisition, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. All

authors have read and approved the final version submitted for pub-

lication.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Chizu Town Office and LASSIC Co., Ltd.

References

Chun, M.H., Chang, M.C., Lee, S., 2017. The effects of forest therapy on depression and

anxiety in patients with chronic stroke. Int. J. Neurosci. 127, 199–203.

Frumkin, H., 2001. Beyond toxicity: human health and the natural environment. Am. J.

Prev. Med. 20, 234–240.

Kang, M.G., Koh, S.B., Cha, B.S., Park, J.K., Baik, S.K., Chang, S.J., 2005. Job stress and

cardiovascular risk factors in male workers. Prev. Med. 40, 583–588.

Kawakami, N., Tsutsumi, A., 2016. The stress check program: a new national policy for

monitoring and screening psychosocial stress in the workplace in Japan. J. Occup.

Health 58, 1–6.

Kim, B.J., Jeong, H., Park, S., Lee, S., 2015. Forest adjuvant anti-cancer therapy to en-

hance natural cytotoxicity in urban women with breast cancer: a preliminary pro-

spective interventional study. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 7, 474–478.

Kivimäki, M., Kawachi, I., 2015. Work stress as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 17, 74.

López-Pousa, S., Bassets Pagès, G., Monserrat-Vila, S., de Gracia Blanco, M., Hidalgo

Colomé, J., Garre-Olmo, J., 2015. Sense of well-being in patients with fibromyalgia:

aerobic exercise program in a mature forest–a pilot study. Evid.-Based Complement.

Altern. Med. 2015, 614783.

Lee, J.Y., Lee, D.C., 2014. Cardiac and pulmonary benefits of forest walking versus city

walking in elderly women: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Eur. J. Integr.

Med. 6, 5–11.

Lee, J., Park, B.J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2009. Restorative effects of

viewing real forest landscapes, based on a comparison with urban landscapes. Scand.

J. For. Res. 24, 227–234.

Lee, J., Park, B.J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Ohira, T., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2011. Effect of

251

C. Song et al.

forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male

subjects. Public Health 125, 93–100.

Lee, J., Li, Q., Tyrväinen, L., Tsunetsugu, Y., Park, B.J., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2012.

Nature therapy and preventive medicine. In: Maddock, J.R. (Ed.), Public Health-

Social and Behavioral Health. InTech, Rijeka, Croatia, pp. 325–350.

Lee, J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Takayama, N., Park, B.J., Li, Q., Song, C., Komatsu, M., Ikei, H.,

Tyrväinen, L., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2014. Influence of forest therapy on cardi-

ovascular relaxation in young adults. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014,

834360.

Li, Q., Morimoto, K., Nakadai, A., Inagaki, H., Katsumata, M., Shimizu, T., Hirata, Y.,

Hirata, K., Suzuki, H., Miyazaki, Y., Kagawa, T., Koyama, Y., Ohira, T., Takayama, N.,

Krensky, A.M., Kawada, T., 2007. Forest bathing enhances human natural killer ac-

tivity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol.

20, 3–8.

Li, Q., Morimoto, K., Kobayashi, M., Inagaki, H., Katsumata, M., Hirata, Y., Hirata, K.,

Suzuki, H., Li, Y.J., Wakayama, Y., Kawada, T., Park, B.J., Ohira, T., Matsui, N.,

Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., Krensky, A.M., 2008a. Visiting a forest, but not a city,

increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J.

Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 21, 117–127.

Li, Q., Morimoto, K., Kobayashi, M., Inagaki, H., Katsumata, M., Hirata, Y., Hirata, K.,

Shimizu, T., Li, Y.J., Wakayama, Y., Kawada, T., Ohira, T., Takayama, N., Kagawa, T.,

Miyazaki, Y., 2008b. A forest bathing trip increases human natural killer activity and

expression of anti-cancer proteins in female subjects. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents

22, 45–55.

Maas, J., Verheij, R.A., Groenewegen, P.P., Vries, S.D., Spreeuwenberg, P., 2006. Green

space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community

Health 60, 587–592.

Mao, G.X., Cao, Y.B., Lan, X.G., He, Z.H., Chen, Z.M., Wang, Y.Z., Hu, X.L., Lv, Y.D.,

Wang, G.F., Yan, J., 2012. Therapeutic effect of forest bathing on human hyperten-

sion in the elderly. J. Cardiol. 60, 495–502.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2012. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/h24-

46-50.html.

Morita, E., Fukuda, S., Nagano, J., Hamajima, N., Yamamoto, H., Iwai, Y., Nakashima, T.,

Ohira, H., Shirakawa, T., 2007. Psychological effects of forest environments on

healthy adults: Shinrin-Yoku (forest-air bathing, walking) as a possible method of

stress reduction. Public Health 121, 54–63.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 1999. Stress … at Work. Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

(Publication no. 99–101, 26 p).

Ochiai, H., Ikei, H., Song, C., Kobayashi, M., Takamatsu, A., Miura, T., Kagawa, T., Li, Q.,

Kumeda, S., Imai, M., Miyazaki, Y., 2015. Physiological and psychological effects of

forest therapy on middle-aged males with high-normal blood pressure. Int. J.

Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 2532–2542.

Ohtsuka, Y., Yabunaka, N., Takayama, S., 1998. Shinrin-Yoku (forest-air bathing and

walking) effectively decreases blood glucose levels in diabetic patients. Int. J.

Biometeorol. 41, 125–127.

Park, B.J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kasetani, T., Hirano, H., Kagawa, T., Sato, M., Miyazaki, Y.,

2007. Physiological effects of Shinrin-Yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the for-

est)–using salivary cortisol and cerebral activity as indicators. J. Physiol. Anthropol.

26, 123–128.

Park, B.J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kasetani, T., Morikawa, T., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2009.

Physiological effects of forest recreation in a young conifer forest in Hinokage Town,

Japan. Silva Fennica 43, 291–301.

Park, B.J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kasetani, T., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2010. The physiological

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 27 (2017) 246–252

effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence

from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Preventative Med.

15, 18–26.

Park, B.J., Furuya, K., Kasetani, T., Takayama, N., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2011.

Relationship between psychological responses and physical environments in forest

settings. Landscape Urban Plann. 102, 24–32.

Shimamoto, K., Ando, K., Fujita, T., Hasebe, N., Higaki, J., Horiuchi, M., Imai, Y.,

Imaizumi, T., Ishimitsu, T., Ito, M., et al., 2014. The Japanese Society of Hypertension

guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens. Res. 37,

253–390.

Shin, W.S., Yeoun, P.S., Yoo, R.W., Shin, C.S., 2010. Forest experience and psychological

health benefits: the state of the art and future prospect in Korea. Environ. Health

Preventative Med. 15, 38–47.

Shin, W.S., Shin, C.S., Yeoun, P.S., Kim, J.J., 2011. The influence of interaction with

forest on cognitive function. Scand. J. For. Res. 26, 595–598.

Shin, W.S., Shin, C.S., Yeoun, P.S., 2012. The influence of forest therapy camp on de-

pression in alcoholics. Environ. Health Preventative Med. 17, 73–76.

Siegrist, J., Li, J., 2016. Associations of extrinsic and intrinsic components of work stress

with health: a systematic review of evidence on the effort-reward imbalance model.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13, 432.

Song, C., Joung, D., Ikei, H., Igarashi, M., Aga, M., Park, B.J., Miwa, M., Takagaki, M.,

Miyazaki, Y., 2013. Physiological and psychological effects of walking on young

males in urban parks in winter. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 32, 18.

Song, C., Ikei, H., Igarashi, M., Miwa, M., Takagaki, M., Miyazaki, Y., 2014. Physiological

and psychological responses of young males during spring-time walks in urban parks.

J. Physiol. Anthropol. 33, 8.

Song, C., Ikei, H., Kobayashi, M., Miura, T., Taue, M., Kagawa, T., Li, Q., Kumeda, S.,

Imai, M., Miyazaki, Y., 2015a. Effect of forest walking on autonomic nervous system

activity in middle-aged hypertensive individuals: a pilot study. Int. J Environ. Res.

Public Health 12, 2687–2699.

Song, C., Ikei, H., Igarashi, M., Takagaki, M., Miyazaki, Y., 2015b. Physiological and

psychological effects of a walk in urban parks in fall. Int. J Environ. Res. Public

Health 12, 14216–14228.

Song, C., Ikei, H., Miyazaki, Y., 2016. Physiological effects of nature therapy: a review of

the research in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13, 781.

Song, C., Ikei, H., Kobayashi, M., Miura, T., Li, Q., Kagawa, T., Kumeda, S., Imai, M.,

Miyazaki, Y., 2017. Effect of viewing forest landscape on middle-aged hypertensive

men. Urban For. Urban Green. 21, 247–252.

Sung, J., Woo, J.M., Kim, W., Lim, S.K., Chung, E.J., 2012. The effect of cognitive be-

havior therapy-based Forest Therapy program on blood pressure, salivary cortisol

level, and quality of life in elderly hypertensive patients. Clin. Exp. Hypertens.

34, 1–7.

Takano, T., Nakamura, K., Watanabe, M., 2002. Urban residential environments and se-

nior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: the importance of walkable green spaces. J.

Epidemiol. Community Health 56, 913–918.

The SPRINT Research Group, 2015. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard

blood-pressure control. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2103–2116.

Tsunetsugu, Y., Park, B.J., Ishii, H., Hirano, H., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2007.

Physiological effects of Shinrin-Yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest) in an

oldgrowth broadleaf forest in Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 26,

135–142.

Tsunetsugu, Y., Lee, J., Park, B.J., Tyrväinen, L., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., 2013.

Physiological and psychological effects of viewing urban forest landscapes assessed

by multiple measurements. Landscape Urban Plann. 113, 90–93.

252