sustainability

Article

Evaluating the Relationship between Park Features and

Ecotherapeutic Environment: A Comparative Study of

Two Parks in Istanbul, Beylikdüzü

Didem Kara 1,* and Gülden Demet Oruç 2

1 Urban Design Master Program, School of Engineering, Science and Technology,

Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul 34469, Turkey

2 Urban and Regional Planning Department, Faculty of Architecture, Istanbul Technical University,

Istanbul 34437, Turkey; orucd@itu.edu.tr

* Correspondence: karadi@itu.edu.tr; Tel.: +90-5534-921-003

Citation: Kara, D.; Oruç, G.D.

Evaluating the Relationship between

Park Features and Ecotherapeutic

Environment: A Comparative Study

of Two Parks in Istanbul, Beylikdüzü.

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600. https://

doi.org/10.3390/su13094600

Abstract: The impacts of problems related to dense, unplanned, and irregular urbanization on

the natural environment, urban areas, and humankind have been discussed in many disciplines

for decades. Because of the circular relationship between humans and their environment, human

health and psychology have become both agents and patients in interactions with nature. The

field of ecopsychology investigates within this reciprocal context the relationship between human

psychology and ecological issues and the roles of human psychology and society in environmental

problems based on deteriorated nature–human relationships in urbanized areas. This approach

has given rise to ecotherapy, which takes a systemic approach to repairing this disturbed nature–

human relationship. This study aims to uncover the relationship between the physical attributes of

urban green areas and their potential for providing ecotherapy service to users, first by determining

the characteristics of ecotherapeutic urban space and urban green areas given in studies in the

ecopsychology and ecotherapy literature, and then by conducting a case study in two urban parks

from the Beylikdüzü District of the Istanbul Metropolitan Area. The impacts of these parks’ changing

physical characteristics on user experiences are determined through a comparison of their physical

attributes and the user experiences related to their ecotherapy services.

Keywords: greening cities; urban design; ecopsychology; ecotherapy

Academic Editor: Israa H. Mahmoud

Received: 24 February 2021

Accepted: 12 April 2021

Published: 21 April 2021

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Copyright: © 2021 by the authors.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

1. Introduction

There has always been a bidirectional relationship between humankind and its envi-

ronment. While humanity changes the environment based on its needs, the environment

has in turn played an essential role in human evolution and development. Urban areas are

one of the best examples of anthropogenic impacts on the environment. Such places are

structured based on human needs and lifestyles under the influence of other anthropogenic

factors such as industrialization, population growth, migration, development levels, and

national policies. The phenomena born of these factors, such as rapid and distorted ur-

banization, have negatively affected natural areas and resources, leading to the creation

of problematic and substandard urban areas. Moreover, the establishment of unplanned

urban areas has resulted in both direct and indirect harm upon their inhabitants [1].

The indirect impacts of these areas are felt mostly in the natural environments that

provide vital services for human life, resulting in shortages of environmental resources, the

destruction of necessary ecosystems, the loss of biodiversity, and rises in global warming

and pollution [2]. The direct impacts involve the damage caused by these urban areas to

people’s physical and mental health, e.g., diseases that can spread quickly in dense urban

areas with poor physical conditions and a lack of infrastructure [3–8], lifestyle-related

illnesses [3,4,6,9,10] resulting from the lack of physical activity and unhealthy dietary

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094600

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

2 of 23

habits and food provision in some urban areas, afflictions related to exposure to urban

pollution [3–6,8,9], and, lastly, mental issues caused by urban features such as the lack of

social infrastructure [11], poor physical conditions, pollution [3,4,8,11–13], high population

densities, and overcrowding [3,4,8,12,13].

The role of environmental sciences in solving the problems above has become more

prominent; however, world ecosystems and human populations are still facing constant

ecological issues. Considering the importance of individual behavior and awareness, there

is a need for systemic (and comprehensive) approaches and solutions in terms of the

reconstruction of individuals’ relationship with nature and the environment. In this way

the outputs of the social sciences examining human–nature relationships may offer valuable

inputs for the urban planning and design disciplines. Environmental psychology stands

out for this purpose, as it has been examining since the 1960s the bidirectional relationship

between humans and the environment, its focus ranging from the physical and social

effects of urban space to the impacts of natural areas on human psychology. Moreover,

discussions on sustainability have included the claim that environmental psychology has

evolved as a “psychology of sustainability” [14].

First coined by Theodore Roszak in 1992, ecopsychology has helped to develop

environmental awareness and change behavior toward ecological problems through ex-

amination of the relationship between the environmental issues and human spiritual or

psychological ones. Roszak argued that human activities and economic systems have

changed, detailing the harmful effects of this changing activity and economic order on

the ecosystem. Roszak noted that disconnection from nature and other people due to

urbanization both increases negative impacts on the environment and deepens psycho-

logical problems [15]. To this end, the field examines the roles of human psychology and

society in environmental issues within the framework of the deteriorated nature–human

relationship [16].

In his treatment of the relationship between people and the environment, Scull posited

a more experiential role for ecopsychology in theory and practice, asserting that many

things can be learned through contact with nature [16]. This approach is speculative,

philosophical, and theoretical, preparing a basis for the reconstruction of the nature–

human relationship with a new language and model; it may also have a role to play

in environmental protection and in solving human psychological problems through the

adoption of practices such as environmental activism and ecotherapy.

At this point, it is clear that ecopsychology offers a solution to the problems of ur-

banization and urban areas based on the individual’s perspective of and connectedness to

nature (CNS). In addition to Scull’s approach, through which strong ties are established to

fields such as deep ecology and environmental activism, ecotherapy studies have intro-

duced a systemic therapy method for repairing the disturbed nature–human relationship.

Clinebell defined ecotherapy as “recovery and growth with a healthy relationship with

the world” [17], using it as an inclusive term in the context of nature-based physical and

psychological recovery methods. This approach to ecotherapy deals with psychotherapy

and psychiatry in the context of nature and nature–human relationships. Clinebell labeled

ecological deterioration the most profound health issue of all time owing to the vital role of

ecosystems in the continuity of our kind and offered as a solution to this problem the raising

of awareness about lifestyles through ecotherapy and early childhood eco-education [17].

Ecotherapy thus may offer a help to solve environmental problems and the psycho-

logical issues caused by disconnection from nature. Ecotherapeutic studies are based on a

three-phased process: (1) acknowledgment of the healing presence of nature, (2) recogni-

tion of more-than-human experiences and self-relocation in the natural world, and (3) the

sharing of this experience with other people and involvement in activities that care for the

planet [17]. Ecotherapy is the name given to a wide range of programs aiming to improve

mental and physical health through activities in natural areas and connection to nature.

These activities include working in or experiencing nature [18]. However, the fulfillment

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

3 of 23

of this reconnection is conditional on spending time and being active in natural areas and

making these activities a part of daily life.

It is thus essential to be in nature and understand that being a part of the ecosystem is

vital to solving both physical and mental health problems as well as to help the environ-

mental crisis. Accordingly, ecotherapy helps people to recognize nature, appreciate it more,

and be respectful to the earth. The necessity of addressing this approach through spatial

studies has arisen from an emphasis on the importance of natural areas and spending time

in nature, as issues related to disconnection from nature occur most frequently in urban

spaces where natural areas and elements are scarce. Natural areas and urban greeneries

have been subjects for examination in environmental disciplines for many decades because

of their services to humans, their recreational functions, and their importance to urban

quality and ecosystems [19,20]. Studies have investigated the benefits of these qualities for

mental and physical health, in particular, their role in encouraging people to do physical

exercise [21,22]. However, apart from their impacts on overall health, spatial studies have

focused on the role of ecopsychology and ecotherapy to help people to be aware of envi-

ronmental problems. For this purpose, it is helpful to understand their therapy functions

for citizens in addition to their impacts on the quality of urban areas. The design of urban

green spaces should be reviewed based on the features of therapeutic environments that

create environmentally conscious individuals who can address the source of their health

problems and environmental problems.

This study aims to reveal the relationship between the physical attributes of the urban

green areas and their potential for providing ecotherapy service to citizens. The first section

contains a brief explanation of the aspects of ecotherapeutic environments, determining

the characteristics of ecotherapeutic urban spaces and urban green areas through an

examination of the benefits obtained from green or natural places, their effects on human

psychology, the attributes of therapeutic areas, and the types of therapeutic activities.

These have been classified by discourse analysis in accordance with their contribution to

the urban design process. In determining the attributions above, literature research was

conducted in the Scopus’ database in August 2019. A total of 249 papers were found in the

database with the “ecopsychology” keyword and 57 with the “ecotherapy” keyword. Out

of these articles, those related to psychology, social sciences, and environmental sciences

were filtered, and 37 articles remained to be examined. The findings of this literature review

were presented in detail at the 28th Symposium of Urban Design and Implementations and

published as an article in the Design+Theory Journal in Turkish [1].

The second part of the study examines two parks from the Beylikdüzü District of

the Istanbul Metropolitan Area in order to compare the impressions of the results ob-

tained from a literature review of space and user experience. This comparison is twofold:

(1) physical characteristics and (2) user experience. The physical characteristics of the

parks are analyzed and presented via several maps, satellite images, diagrams and pictures.

Data concerning user experience were obtained through a survey conducted with the

users of these parks. This study adds to the ecopsychology literature by evaluating the

ecotherapeutic benefits of green spaces and how these differ according to the urban design

principles adopted when designing the spaces. In addition to highlighting the ecological

and recreational benefits of urban green spaces, this study provides guidance for planning

and designing green areas with improved ecotherapeutic features that may further enhance

the psychological health and environmental awareness of city residents.

2. Characteristics of Ecotherapeutic Environment

The characteristics of ecotherapeutic environments and their effects on human psy-

chology can be evaluated according to ecotherapeutic activities, type, benefits and features

of ecotherapeutic environments. Ecotherapeutic activities are examined within two cate-

gories: working in nature and experiencing nature. Working in nature includes various

athletic activities defined as the green and blue gym [23–29], the most significant of which

is walking [23–26,30–35]. Apart from athletics, this group comprises activities such as

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

4 of 23

meditation/therapy [23,25,28,33,34,36,37], art [28,38,39], and production in/with nature

(frequently gardening and horticulture) [36,38]. Experiencing nature involves spending

time observing and listening in nature [23,26,28–30,32,36,38]. Activities from both groups

can be conducted in natural areas to obtain ecotherapy services, and an understanding

of these activities allows designers to provide proper facilities or places to citizens in

these areas.

The types of ecotherapeutic environments are grouped according to their location

in inner, peripheral, and outer urban areas. Ecotherapeutic areas located on the outer

and peripheral parts of an urban area include various natural areas and landscapes, of

which forests [23,24,30,31,40–43] and wilderness areas [23,25,32,36,44,45] are the most

prominent types. Ecotherapeutic areas located in inner urban areas include many

public and private green areas; urban parks [24–26,30–33,36,38,41–43,46,47] and private

gardens [23,26,36,43,48–50] are the most prominent examples of this type. These results

reveal the need for natural spaces and urban greeneries in the urban texture because of

their ecotherapy benefits. Moreover, they underline the importance of providing and

protecting these areas both within and outside of the urban texture. Knowledge of the

types of ecotherapeutic areas can help planners and designers consider these areas in their

spatial decisions.

The benefits of therapeutic environments on human psychology comprise two cate-

gories: (1) mental and emotional benefits and (2) advancement in self-placement and per-

ception. The most prominent mental and emotional benefits are relaxation [24,26,27,36,51],

improvement in attention [24,28,30,34,39,41,48,52], concentration [26,31,34,53], and

mood [23,26,29,34,48,51], and declines in stress [23,24,26,28–31,33,34,36,43,48,51,52], anxi-

ety, depression [25,28,30,33,39,48], and anger [39,41]; better self-esteem is the most promi-

nent manifestation of advancement in self-placement and perception [25–28,34,39,48,54].

These results demonstrate that spending time in natural areas helps people to cope with

mental problems and gains importance in tandem with the growing negative impacts of

urban areas on human mental health. Ecotherapy services increase the quality of life of

citizens. Recognizing these benefits offers a new perspective for urban studies and design

practices, especially in terms of designing cities and their green areas in a way that will

provide ecotherapy services.

The features of ecotherapeutic areas, which can serve as the most directing outputs

to environmental designers, are grouped into the categories of accessibility and size, de-

sign features, the fauna of therapeutic areas, and the sensations the areas create. First, as

mentioned above, spending time in nature daily is essential in the provision of ecotherapy

services. So the accessibility [34,36], inner circulation [39], and size [36,55] of these areas

should be suitable for the daily use of citizens in their activities. The second group, design

features, includes subgroups such as vegetation and natural elements, facilities and furni-

ture, physical environmental control (daylight, wind, etc.), inner view and perception, and

relationship with surrounding urban space. Vegetation and natural elements consists of

the existence of landscapes and green areas with trees [29,30,32,36,45,55], bushes [26,30,55],

grass [55], and flowers [24], and their type [30], density [31,42,56], and diversity [42,50]. Nat-

ural and artificial water elements [24,26,30,32,36,41,45] are evaluated under this subgroup.

The facilities and furniture subgroup involves, rather than specific facility or furniture

types, the compatibility of the furniture materials [26,55] with the natural characteristics of

the area. It also includes certain exercise equipment [26] that encourages people to be more

active. The inner view and perception subgroup comprises the necessity of structuring

depth, complexity, enclosure, and vegetation density, each in a well-balanced manner,

allowing for open views and remote landscapes [42,56]. Moreover, the visual relationship

between ecotherapeutic areas and urban texture is a critical part of providing pristine and

more natural perception [36,50] in an area. Consequently, it is better to obscure visibility

of the urban pattern from ecotherapeutic areas [56] and increase the visibility of these

areas from urban spaces [45,50] through regulations such as those that limit the number of

floors in new buildings, lower urban density around green spaces [32,57], and create mild

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

5 of 23

transitions from parks to urban areas [56]. Additionally, the presence of fauna enhances the

natural image of the area, and encounters with wild animals and hearing animal sounds

(bird sound, etc.) increase therapy service [26,29,31,41,45,53]. Lastly, ecotherapeutic ar-

eas create sensations helpful in obtaining therapy services such as peacefulness [41,58],

quiet [26], solitude, distance [55], aesthetic pleasure [26], beauty [26,41], and fascination [35].

In order to obtain ecotherapy services as they are defined, people require the presence of

sensations that oppose those endemic to dense urban areas such as overcrowding, noise

pollution, etc. Natural elements and characteristics have thus become prominent in the

design of therapeutic areas.

3. Method

The methodology of the study was twofold: examining the spatial characteristics

of selected urban parks and examining the change of user experience according to the

features of the parks. For the spatial examination of selected parks, the characteristics

of the surrounding urban fabric and demographic structure of the population they serve

were kept constant for the purpose of comparing their internal characteristics and the

relationships they established with the surrounding urban fabric. Accordingly, two parks

located close to each other were selected for the examination. The study also compared

the different features of these two parks, such as type, size, form, design, and vegetation.

A detailed examination of vegetation was conducted for this study with the help of site

observation, 28 videos and 691 photographs that have geo-positioning data.

In order to evaluate user experience, a survey was conducted in the selected urban

parks (Table S1). The first section of the survey contained a scale measurement of “connect-

edness to nature” to gauge individuals’ effective and experiential connection to nature [59].

The scale was developed for the empirical studies on the basis of Leopold’s claim that

the environmental awareness depends on the feeling of belonging to the wider natural

world [60]. Dependently, CNS included 14 questions about one’s perspective of being

a member of the natural world, feeling a sense of kinship with it, seeing themselves as

belonging to the natural world as much as it belongs to them, and considering that their

welfare depends on the welfare of natural world [59]. It was developed as a 5-point Likert

scale, and scores were calculated as a mean value of the answers. CNS was selected, first,

to seek out a relationship between the frequency of time spent in selected urban parks and

consciousness about the value of the natural environment, and, second, to determine a

relationship between the user profile regarding connectedness to nature and ecotherapy

service. An understanding of user profile relation to environmental issues and connected-

ness to nature was essential in revealing whether or not the ecotherapy service provided

by the city parks was available regardless of the user profile and ecological consciousness.

The second section of the survey consisted of 5-point Likert scales and open-ended

questions about the features, activities, and feelings highlighted in ecopsychology and

ecotherapy literature. The section made inquiries concerning types of activities, the ad-

equateness of the parks for users, the impact of park characteristics on park preference,

satisfaction with park characteristics, the influence of interior and exterior features or

factors on the natural image of the parks, the relationship with the surrounding urban area,

and the emotions/mental states that participants experienced during park use.

The survey was conducted in two selected parks at the same time, on four days from

12–15 September 2020 (two days during the week and two days on the weekend) from

8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Participants were chosen randomly within the two parks. The researchers

first introduced themselves, informed the participant about the study, and the participant’s

consent was obtained for conducting the survey. A total of 90 subjects (49 male, 41 female)

participated in the survey, 45 from each park. As the data on the total daily users of the

park were unavailable, the decision on minimum sample size was based on the Central

Limit Theorem, which defines the accurate sample size as more than 30. Besides, according

to the calculations made on the population of the neighborhoods surrounding the parks,

the ideal sample size was found to be 96 people, yet the sample was limited to 90 people in

of the park were unavailable, the decision on minimum sample size was based on the

Central Limit Theorem, which defines the accurate sample size as more than 30. Besides,

according to the calculations made on the population of the neighborhoods surrounding

the parks, the ideal sample size was found to be 96 people, yet the sample was limited to

Sustainability92002p1e, 1o3p, 4l6e00in total because the proposed park users did not volunteer to participate in the

survey during the pandemic.

6 of 23

4. Case Study total because the proposed park users did not volunteer to participate in the survey during

the pandemic.

The history of the Istanbul Metropolitan Area goes back to the ancient settlements of

7–8 thousand year4s.aCgaos.eItStius daycity that later became the capital city of important empires

such as the Byzantine aTnhde hOistttoormyaonf .thTehIestmanobsutliMmeptroorptaonlittapneAriroeda goofetsimbaeckthtaotthche aanngcieednttsheettlements of

face of the city too7k–8pltahcoeusianntdhyeeRarespaugbol.icItpisearicoidty. tWhaitthlatehrebiencdamusetrthiaeliczaaptiitoalncpityroocfeisms,pmorit‐ant empires

gration from rural stuocuhrabsanthaerBeayszaanntdinreaapnid uOrtbtoamniazna.tiTohnehmavoesttaimkepnorptalanctepseirniocde tohfeti1m95e0tsh;at changed

the city has begunthtoe sfapcreaowflthaendcitlyostoeotkhpeliamcepionrtthaenRt nepautubrliaclpaenrdiodg.reWeinthatrheeasin[d6u1s,6tr2i]a.liTzhateion process,

development direcmtiiognraotifotnhefrocimtyrsuhraifltetodufrrboamn tahreeaesaasnt–dwraepstidduirrebcatnioiznattioonthheanvoerttahkewnhpelraece since the

the forests

Bosporus.

Iannaddodtiht1wTie9ohhr5nee0n,rsdae;detttuvuhhereeelaocftloipotarymertshheetaasensstaibnnadedrcigrereouecrtanhtiicseotehrond,nsaoapafftrcutatecrhwreaeslltschaaiirnebteydiaclssioltohanysirsefetatetrrnhdiucdechfitr,umioaonmfpntceootrorhntftaehtntreheotacelnsolaetbn–tdrsuwitrdrueaugrslcbteatiasdnondinorievgzocerafterittoeihtonnehnabet,orreidtahsgee[6sn1oo,6vrt2eh]r.

the historical corethheasBobsepcoormuse. Idneandsdeirtioinn, tdimueeto[6th2e].inTcordeaasye,dwacictehssiitbsilditiyvaenrdseucnucoltnutrroallleadnudrbanization,

historical layers antdheohviesrto1r5icmal icloliroenhianshbaebciotamnetsd,eInsstaenr binutliims eth[6e2b].igTgoedsatym, wetitrhopitoslditiavnerasreecaultural and

of Turkey [63]. BehyilsitkodriüczalülaDyeisrtsraicntd, wovheerr1e5 smelilelciotendinuhrabbaitnanptsa,rIkstsanabreulliosctahteedbi,gigsesat nmeewtrloypolitan area

urbanized settlemeonf tTuinrkceoym[6p3a]r. iBsoenylitkodtühzeühDisistotrriyct,owf thheerecsiteyle. cUterdbaunrbdaenvpealorkpsmareenltoocfattehde, is a newly

district was pioneeurrebdanbiyzethdesehtotluemsinengtcionocpoemrpatairviseosninto1t9h9e0hsi[s6to4r]y. Tohf itshedicsittyr.icUt rwbaans sdeelveecltoepdment of the

for the case studyddisutericttowtahseppiorneeseernecdeboyfthgereheonusairnegacsooopf evraatriivoeussinsi1z9e9s0sa[n6d4].shThapisedsisitnrictht we as selected

similar

In

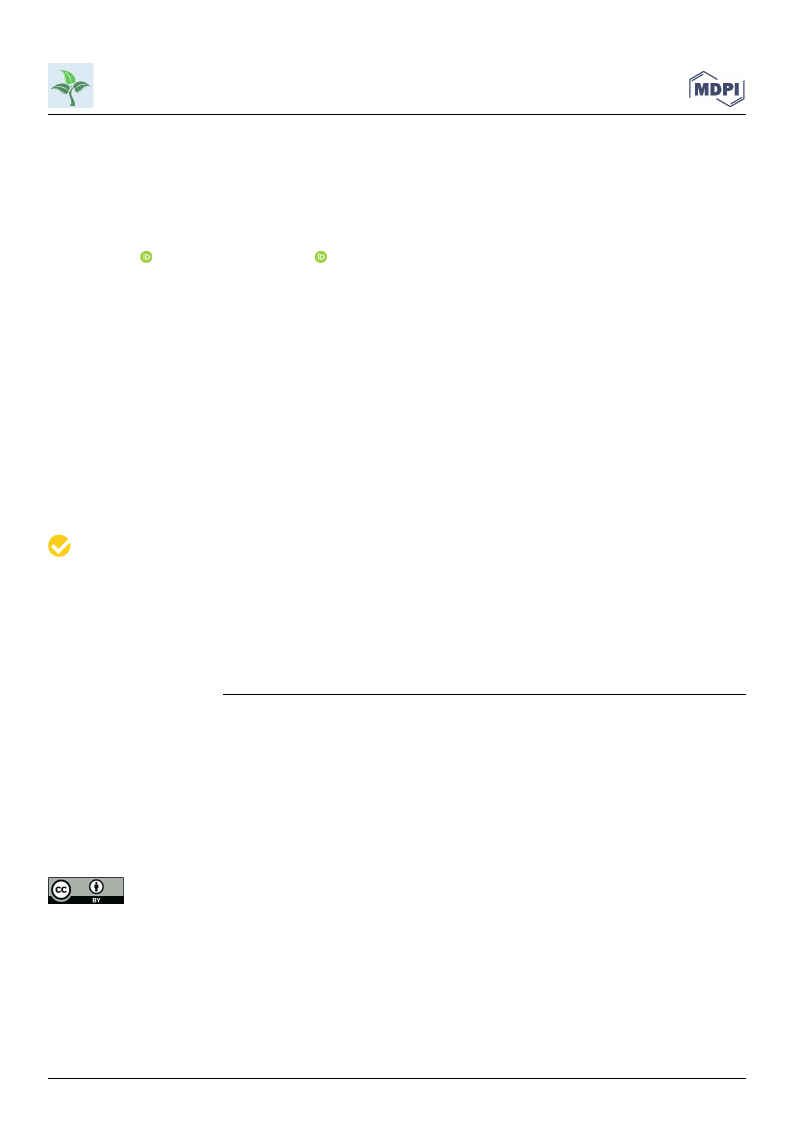

uthrebacnaspeasttteufsoridmnry,til,hfIaonetrwrcutahaorsnebepacansaactrspcukeuadsstryttaweudtrdeneuyr,ce,efoottmwosreaotplhneapecaratpicerscrkdouesnsrteaw.onteechreceeoolsmpfeplggearcaertueiesndgoenato.rtehhaeselorpeflgvaaatuiroigoneustshhsiepizreebsleaattwinodneesshnhiappbesetiwn ethene

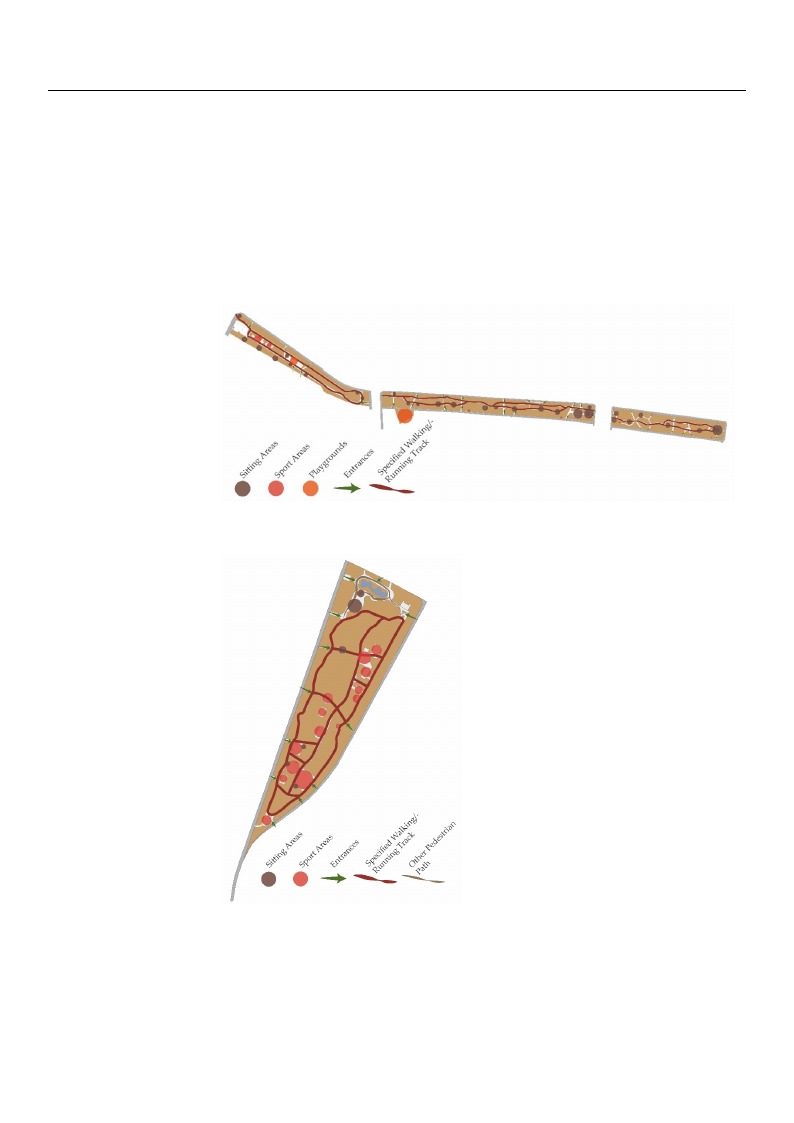

spatial features ansdpautsiealr feexaptuerreiesnacned. Tuhseerfeirxspteorifetnhcees. eTphaerkfisrsits oaf ltihneesaer ppaarrkks sisysatelimnecaor np‐ark system

sisting of the FatihcSounlstiastninMg oehf tmheetF(aFtiShMSu) latanndMMeehhmmete(tFASMki)faEnrdsoMye(hMmAetEA) kWifoEorsdosy, a(MndAEth)eWoods, and

other is the MunicitphealoityhePraisrkth(eFMiguunrieci1p)a. lity Park (Figure 1).

FigurFei1g.u(ar)eL1o.c(aat)ioLnoocfatthieoBneoyflitkhdeüzBüeyDliisktrdicützinüIDstiasntbriuclt; (ibn)ILsotacantbiounl;o(fbse)lLecotceadtpioanrkosfinseBleeycltiekddüpzaürDksistirnicBt;e(yc)‐Location

of palrikksd(üFzigüuDreisitsripcrto; d(cu)cLesocbaytiroenseoafrcphaerrks.s (SFoiugrucree: iYsapnrdoedxuMceaspbsySaretesleliatercIhmearsg.eS, oduartec:e:1Y5aMndayex2M01a8,pasccessed on

15 DeSceamteblleirte20Im20a[g6e5],)d. ate: 15 May 2018, accessed on 15 December 2020 [65]).

Spatial Analysis/ChSarpaactitaelrAisntiaclsysoifs/FCahtaihraSctuerltisatnicsMofehFmateiht S(FuSltMan)ManehdmMete(hFmSMet)Aankidf MEreshomye(tMAkAifEE)rsoy (MAE)

Woods and MunicipWaloitoydsPaanrdkMunicipality Park

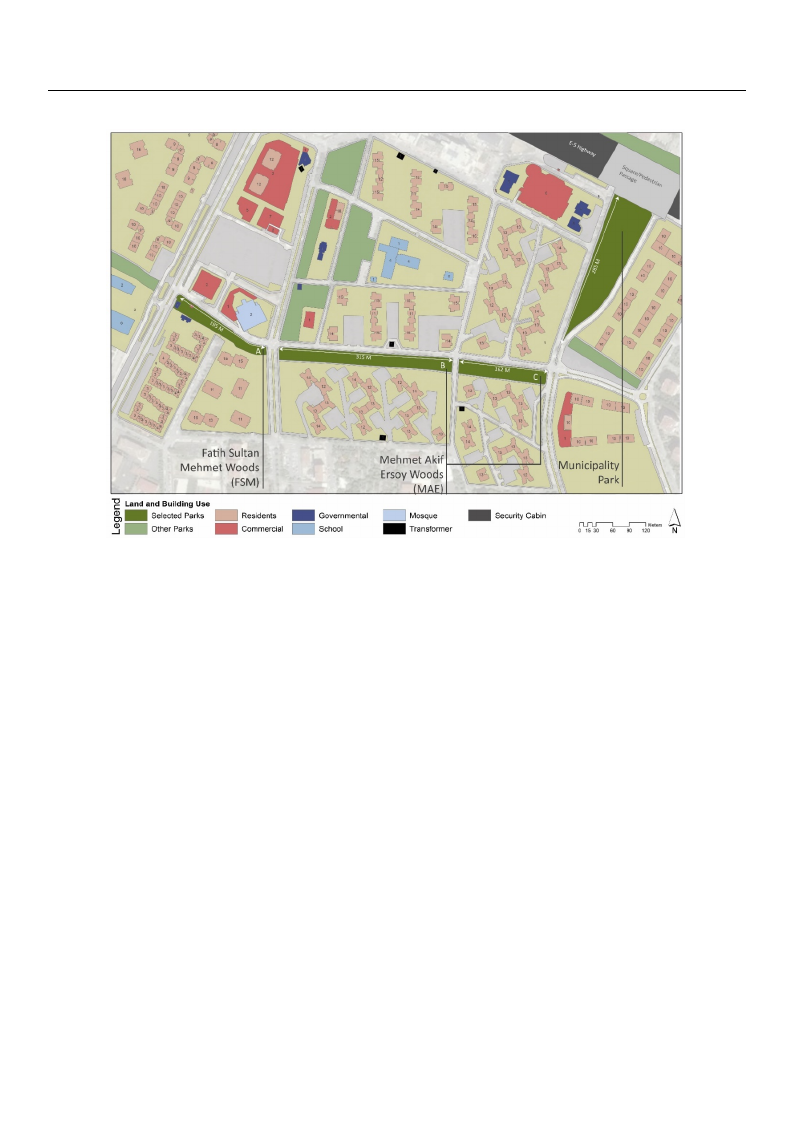

The FSM and MAE Woods are located between a street and a residential dwelling

The FSM anduMnitA. TEhWe tootoadl slenagrethloofcathteedpabrektswyseteenmaiss7t0r2eemt ,aanndd iatsrwesiiddthenvtairailesdfwroemlli1n6gto 25 m (see

unit. The total lengFtihguorfet2h)e. Ipt ahraks asyssutrefmaceisar7e0a2omf 1e5t,e0r0s0, saqnudarietsmweitdertsh. Ovanritehse fortohmer 1h6antdo,2M5unicipality

meters (see FigureP2ar).k,Itlohcatseda astutrhfeaceeasatererna eonfd1o5f,0th0e0 MsqAuEarWeomodeste, irss.aOvangutheelyotrtihaenrguhlaanr-ds,haped park

Municipality Park,2l8o5cmateind laetntghthe aenasdtewrinthenad14o,1f0t7hesqMuaAreEmWetoeordssu,rifsacaevaaregau. eTlyhetrpiarnkgiusladr‐jacent to an

shaped park 285 muertbearnssiqnulaernegdtehsiagnndedwfoitrhpead1e4st,r1i0a7n spqaussaargeemabeotveer tshuerEfa-5cehiagrhewa.aTyh(Feigpuarrek2).

is adjacent to an urban square designed for pedestrian passage above the E‐5 highway

(Figure 2).

21, 13, x FOSuRstPaiEnaEbRilitRyE2V02I1E,W13, 4600

7 of 24

7 of 23

FigureFi2g.uLrean2d. Luasnesdaunsdesnaon. dofnob.uoilfdbinugilfldoinogrsflinootrhseinsutrhroeusnudrirnogunudrbinang aurrebaa(nreaprreoad(urceepdrobdyurceesdeabrcyhreers‐ from the

MunicsiepaarlcithyeBrassferoMmapth[6e6M]).unicipality Base Map [66]).

These parks and tThheesseuprraoruksnadnindgthuersbuarnroaurnedainhgavuerbaanneaareralyhfalvaet atonpeoagrlryapflahtyt,owpohgircahphy, which

provides easy accepsrsoavniddesmeoasbyilaitcycefsosrapneddmesotbriilaitnysf.oTrhpeedlaenstdriuansse.sTohfethlaensduursreosuonfdthinegsuurrrbouannding urban

alarregaecfoancisliisttiems sousctlhfalyaararceogisalfeimcthifoeaoinsgcssihlqliiislkutytieeemspss,ocoshssupctocluhoyhlolasooatfsaleshndm,idgaaohnmnsldqydousmpegqosaau,ptlelseusscdl.havWtoareeordhislesiias,dlneaefdrnonodftgmitaamhtloeeanddlnelwrsue.teomslW ildsbiinehxengi,rltenoiuaefolnaffdirltbotwshyoeearrlnslenidsniunigmdafeubanfnecetriiiwtlas‐ol fabnfludoilodarisfnegiwns

ities like schools agnednemraolslyquhaevsevaarhiiegshferronmumobneer,troansigxi,nngefarormbyforeusritdoe1n6ti(aFligbuurield2)i.ngs gener‐

ally have a higher numWbehril,erathnegivneggeftraotmionfoouf rbtooth16pa(rFkigs ucorens2i)s.ts mainly of evergreen trees such as the

While the vegLeawtastoionncyopfrebsos,thpaplmartkresec, oanndsinstust,mblacinkl,yanodf Teevnearsgserreiemnptirneee, sthseurechareasotmhe deciduous

Lawson cypress, ptarelems stureche,aasnthdencuomt, mbloanckas, ha,nNdoTrwenayasmsearpilme, hpoirnsee,cthheesrtneuatr,eacsaocmiaeanddecpilduum‐. As shown

ous trees such as tihneFicgoumrem3o, ncroawshn, cNloosruwreayofmthaepclaen, ohpoyrsies cvhereysthniugth, dacuaectioa tahneddpenlusimty. oAf sthe trees in

shown in Figure 3,bcortohwpanrkclso. sBuerceauosfetohfetchaenporpomy iinsevnecreyohf iegvherdgureeentos,tthheesdeepnasriktys hoafvtehea tvreereysclosed and

in both parks.

and forest‐like

Batemctfaioocursses.pseTTth-hohleieefrkebedthuiiansestthmrepeibvosruseoaptrmniyhodeinsnrseeoheafrnisnutcorbeeensveoswe(fFraeyinergedvsueeebarrvusegaosrl3nhue)ea.e(sFtneissdgh,uobtrwahesese3sdt)eh. oapntaadrlleknsseschittyaiovanensdahlavevneegrdythifcf(elForiegsneutdrech4a).raScptaerrsise-

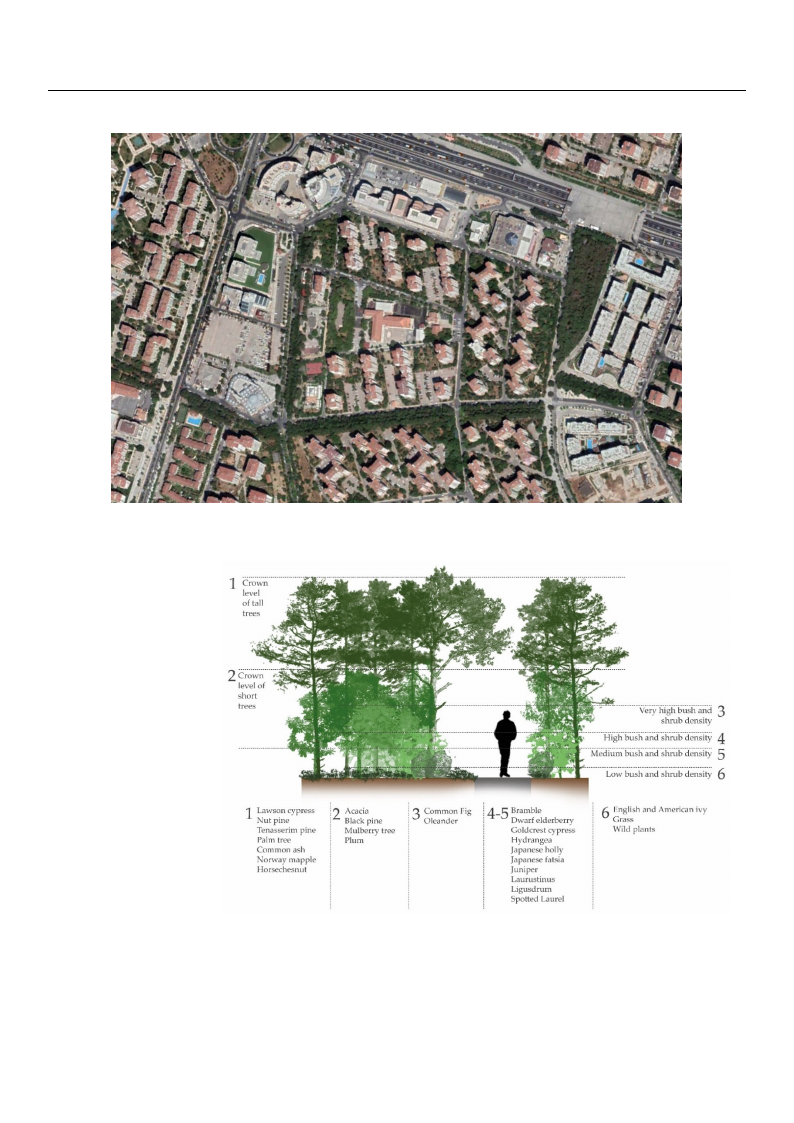

The distributiaonndosfhotrreteins aonthderbsueschtieosnss,hbouwshsetshaant dalslhsreucbtisoanrse hdeanvseediniffthereeFnStMchWaroaocdte(rF‐igure 5). In

istics. The bushesthaendMushnircuipbasliwtyePrearkev, tahleuraeteisdabhaigsehdploanntdveanriseittyyinanbdothletnrgeeths a(nFdigbuursehe4s),. with three

Sparse and short inveogtehtaetriosnecltaiyoenrs,cbounshisetisnagnodf tshhertuabllsesatrpeidneentrseeesinatththeeFtSopM, vWaroioouds (dFeicgiudrueous trees of

5). In the MunicipraelliattyivPelayrksh, otrhterreheisigahthinigthhepmlaindtdlvea, rainedtyvainriobuosthbutsrheeess, sahnrdubbsuasnhdeasn, nwuiatlhwild plants

three vegetation laoynetrhsecfloonosri.sAtinlogngofthteheeatsatlelrenstbporidneer,trtheeespaartkthisesteoppa,ravteadriofruosmdtehceidrouaodubsy a wall of

trees of relatively Lsahworstoenr chyepirgehssteisn. Othnetmheidwdelsete, ranneddgvea,rvioaurisoubsuoshtheesr, tsahllruanbds maneddiuanmn-uheailght bushes

awwildalpl loafnLtsaownsothneciaarfynrrleoedpgnorsuoerhl.sarpsAurleabilsnnos.tntaOehgcdetntflaihntsohenwseeeeerpawrpassaret,aersgttrtroenoarrfssbnst.h-oTceerohddpvegeaederrrk,e,edtnvahsnaseiudrtyiprodfoaauefrccskebresoui,astsoshhesreesewsrpinaitadantrehldal-etosaesphndoerduunftbrhmsospemerbandecectrihosuemgeimniore‐eosnhiahte(hdFiigegigbrhhuyeotrrfeath6n)ed. pTmahroekrrsee.

bushes and shrubs act as separators. The density of bushes and shrubs becomes higher

and more irregular in the inner part of the park and decreases in the southern region (Fig‐

ure 6). There are no planted flowers, grass‐covered surfaces, or wide‐open spaces in either

of the parks.

021, 13, x FSOusRtaPinEabEiRlityR2E0V21IE, 1W3, 4600

Sustainability 2021, 13, x FOR PEER REVIEW

8 of 24

8 of 23

8 of 24

FigureF3i.gSuarteell3it.eSiamtealglieteofimtIFhmiaegagupgeraeer,ok3dfs.atSshtheae:ote0wpl8laiintDrekgeiscmthesmaehgcoberweoorwif2ntn0hg2ce0tlho,paseaucrcckreresos(sswSheodonuworccnilneo:0gs8GuthAoreeopgc(rlrSieloo2wEu0anr2rc1tcehl[:o6SGs7au]to)re.oellgi(tSleeoIuEmracaregt:ehG, Sdoaoattgeel:lel0iEt8eaDrtehcSemateblelrite

2020, aIcmceassgeed, donat0e8: 0A8pDrile2c0e2m1 b[6e7r])2.020, accessed on 08 April 2021 [67]).

FFiigguurree 44.. HHeeiigghhtt aanndd ddeennssiittyy ooff ttrreeeess,, bbuusshheess,, aanndd sshhrruubbss..

Figure 4. Height and density of trees, bushes, and shrubs.

bility 2021,S1u3s,taxinFaObRilitPyE2E0R21R, E1V3,I4E6W00

ability 2021, 13, x FOR PEER REVIEW

9 of 24

9 of 24

9 of 23

Figure 5. Height and density of trees, bushes, and shrubs in the FSM and MAE Woods (repro‐

Figure 5. HdFeuiiggchuetdreabn5yd. Hrdeesniegsahirtctyhaoenfrdstrdbeaessn,esbdituyosnhofethst,reeaeMnsd,ubsnhuicrsuihpbeasl,iitnayntBdhaesshFeSrMuMbasapnin[d6t6Mh]e)A. FESMWoaondds M(reApEroWduocoeddsb(yrerpersoe‐archers based on

the MunicipdaulicteydBbaysereMseaaprc[6h6e]r)s. based on the Municipality Base Map [66]).

Figure 6. HFeiigguhrtea6n.dHdeeinghsittyanodf tdreeness,itbyuosfhterse,easn, bdusshhreusb, sanindMshurnuibcsipinalMityuPnaicrikpa(rleitpyrPoadrukce(rdepbryordeusceeadrcbhyers based on the

MunicipalitrFyeisgBeuaasrrechM6e. raHspeb[ia6gs6he]td).aonnd tdheenMsituynoicfitpraeleisty, bBuassheeMs, aapnd[6s6h])r.ubs in Municipality Park (reproduced by

researchers based on the Municipality Base Map [66]).

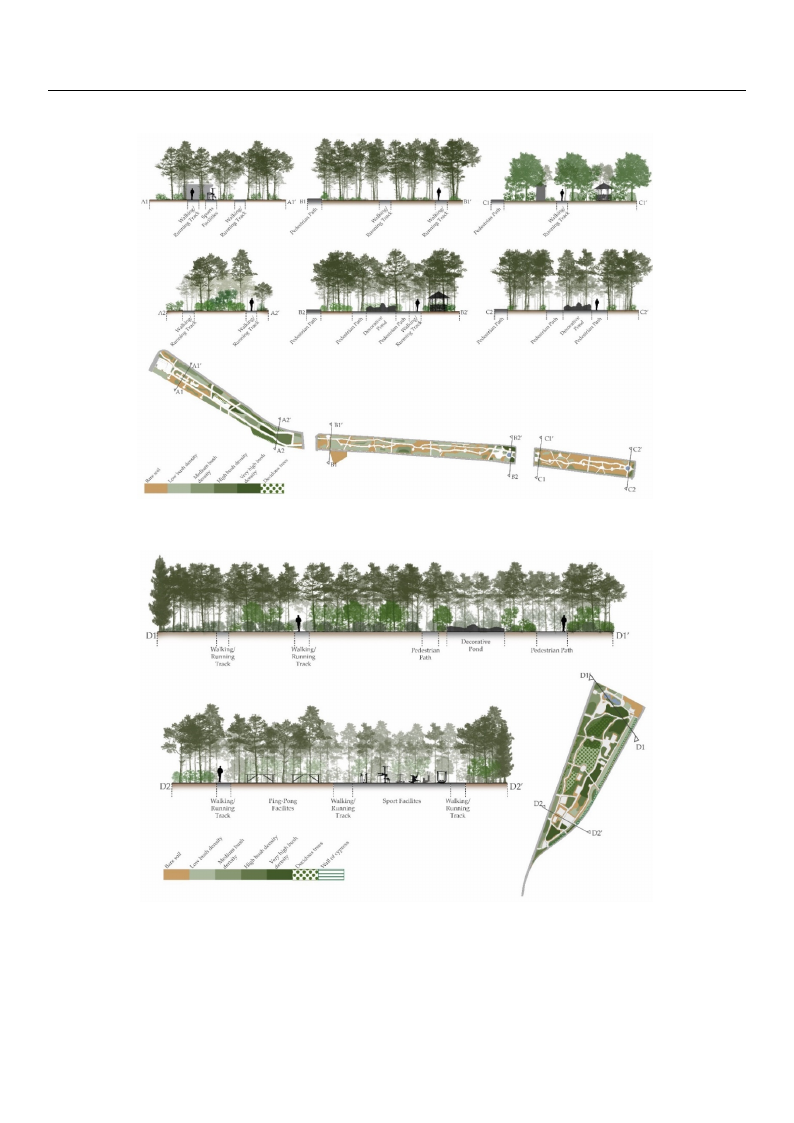

In regard to theInfarceilgiatireds taondthfeixfaecdilfiutirensitaunrde,fitxheedpfaurrknsithuorues, ethveapriaoruksschoomusmeovnaruirobuasncommon urban

mfwfwuuiarirttninhhniitIltoouynunnrrrreeeeueagsansnuanuadrcdcldhhosspntwmfpaaougororiaretrternthihtatahnsiseteloifiufynfnanamarcrceecttiuiahihllalsiniieietnunttiiiaedFceFeclshsSsiSos.r.MMnpaMacMnugoreoodrWlWtaatsshsftttooiieiofnoxoooamfenfdcdtdttih.ahr.hlioeifTeTetnuuihFhsesrtcpeSpsenei.oMrsoiwwtcMrruouttaasWfrsollleakftskfoa,htatiiitncoencoohiigdgnlfpleii/./ttatrrrpihiuToreueaeksunhsnrssnatkena.perisriswneonehrgoglalotoofsltuctkctrrfahasiaaanteteccceegkivkdpdl/siasati,i,rrinrnueippkosMnMasauavn.vusureieenncnddoiglicocmwwiitcpprimaiatatathhcleoliikdtntrrysyuui,unPbPbprababbMarereavkkrurne,,,,ndicwipiathlitryuPbabrekr,,

mainly run along the main circulation routes of the parks.

SSuussttaaiinnaabbiilliittyy 22002211,, 1133,, xx FFOORR PPEEEERR RREEVVIIEEWW

1100 ooff 2244

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

10 of 23

BByy aanndd llaarrggee,, tthhee ppaarrkkss’’ ssppoorrttss ffaacciilliittiieess aanndd aarreeaass wwhheerree sseeaattiinngg eelleemmeennttss aarree cclluuss‐‐

tteerreedd ffuunnccttiioonn aass ffooccaall ppooiinnttss ((FFiigguurreess 77––99)).. DDeeccoorraattiivvee ppoonnddss aallssoo ccrreeaattee aann aattttrraaccttiioonn

ppooiinntt Bwwyiittahhndtthhleaeirirrgess,uutrrhrreooupuannrddkiisnn’ggspssoeeraatttsiinnfaggcieelillteeimmeseeannnttdss a((FFreiiggauus rrweeh99e))r..eMMseooasstttinoogffettlhheeme ceciinrrtccsuuallaraettiicoolnnuslltiiennreeessd

ssfeeurrvnvecetaaiossnllaaannsddfsoscccaaappl epeovviiinssttsaass(Ftthihgaauttrcceoosnn7ss–ii9sst)t.ooDff ettuuconnrnnaeetlilv‐‐lleiikkpeeovvniideewswasslsoooff cpprlleaaannttteaaattiinoonna,t,teerssappcteeiccoiinaallpllyyoiinntMMwuuit‐‐h

nntiihccieippiraallsiiuttyyrrPPoaaurrnkkdddinuugeestteooatthhineegvveeelggeeemttaaettniiootsnn(dFdieegnnussriitetyy9(()FF. iiMgguuorrseet o110f0))t..hEEexxcaaimrmcuiinnlaattiioonn looinff etthhseesevvriivssieibbaiillsiittlyyanoodff -

tthhsceeasspuuerrrvrooisuutnnasdditinnhggatuucrrobbnaasnnisppt aaottftteteurrnnnddeeelt-teleirrkmme iivnnieeeddwttshhoaafttpddluuaenetttaootittohhnee, hhesiiggphhecddiaeelnnlyssiiittnyy Mooffuttrnreeieceissp,, abbluuitiiyllddPiinnarggk

vvdiissuiibbeiitlloiittiiteehsseaavrreegsseiitmmatiiilloaanrr iidnnebbnoosittthhypp(Faairrgkkuss.r.eHH1oo0ww).eeEvvxeearrm,, ttihhneeatiiimmonppaaoccfttstshooeffvnnieseiaabrribbliyytyrroooaafddthsseaarsreue rhhriiogguhhneedrriiinnng

tthhueerbFFaSSnMMpaatnnteddrnMMdAAeEEteWWrmooioonddesds,, taahssatthhdeeuiirresstppoaatrrhssee bhbuuigsshheedsseaannnsdidtysshhorrfuutbbresse,, see,ssbppueecicliidaalillnlyygbbveeittswwibeeieelinntiesssiiddaeer‐‐e

wwsaiamllkkisslaaarnniddn wwboootoohddpss,a, rddkoos.nnHoottoccwrreeeaavtteer,aathsstterrooimnnggpbabcaatrrsrriioeefrr nbbeeeattwwrbeeyeennrottahhdeesppaaarrerkkhaaignnhddettrhhieensstuuhrrerrooFuuSnMnddiiannnggd

uuMrrbbAaannE Waarroeeaoa,,daas,nnadds ttthhheeeiiirrr swwpiiaddrttshhe bdduooseehssennsooattnaadllllsoohwwruffboosrr, eaasnnpyyecggirraeellaaytt bddeiitsswttaaenneccnee sffirrdooemmwaaalddkjjsaacaceennndttwrroooaaodddsss,

((FFdiiogguunrroeet 1c1r11e))a.. te a strong barrier between the park and the surrounding urban area, and their

width does not allow for any great distance from adjacent roads (Figure 11).

oFoFFtninihggigettuuhhurMreeeereMuM77n7..uu.AiAcnnAicciiptctcciiaitivvppilviiiaatttiyyylltiiyttpBpyypoaoBBosiinneiaanttssMssteesaaaMMannpnddaad[pp6aaa6xx[[x6]6ee)e66ss.s]]ii))nin..nttthhheeeFFFSSSMMMaaannndddMMMAAAEEEWWWooooddss ((rreepprroodduuuccceeedddbbbyyyrrreeessseeeaaarrrccchhheeerrrsssbbbaaassseeedddon

MFMFMFiigguuiguuunnunrriiceceriiceip8p8ip8..aa.AaAlliilAttcicyytttyciiBBvtviBaiaivttassyyiesetyeppMMoMopiaiaonnappittpnss[[t66[aas66nn6a]]dd))]n..).daaxxaeexsseiisnniMMn uMunnuiiccniiippcaaiplliiattyylitPPyaarPrkkar((krree(pprrreoopddruoudcceeuddcebbdyy brreeyssereeaasrreccahhreecrrhssebbraasssbeedadsooendn ttohhneethe

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

SSuussttaaiinnaabbiilliittyy 22002211,, 1133,, xx FFOORR PPEEEERR RREEVVIIEEWW

Sustainability 2021, 13, x FOR PEER REVIEW

11 of 23

1111 ooff 2244

11 of 24

FFFFigiiiggguuuurrrereee9999. ...SSSSppppoooorrrrtttstsssffffaaaacccciiililliliiittttiiiieeeessssiiiinnnnMMMMuuuunnnniiiicccciiiippppaaaalllliiiittttyyyyPPPPaaaarrrrkkkk((((lllleeeefffftttt)))) aaaannnndddd ppppoooonnnndddd iiiinnnn tttthhhheeeeMMMMAAAEEEWWWoooooooodddd((((rrrriiiigggghhhhtttt))))....

FFFFigiiiggguuuurrrereee11110000. ...LLLLaaaannnnddddssssccccaaaappppeeeevvvviiiissssttttaaaassssffffrrrroooommmmMMMMuuuunnnniiiicccciiiippppaaaalllliiiittttyyyyPPPPaaarrrkkk (((llleeefffttt))) aaannnddd WWWoooooodddsss(((rrriiiggghhhttt)))...

FFFFigiiiggguuuurrrereee11111111. ...RRRRooooaaaaddddvvvviisiisssiiibibbbiiiilllliiiittttyyyyffffrrrroooommmmWWWWooooooooddddssss(((l(lleleeefffftttt))))aaaannnnddddMMMMuuuunnnniiiciccciiipipppaaaallliliiittttyyyyPPPPaaaarrrrkkkk((((rrrriiiigggghhhhtttt))))....

paPfattedpaaatcphhadpaaatcpdpaaatcpxsneaaahahdtcdtheeleidteliploelildrlttttaefefttiiefiaarsijrarijkrrijfplrinfenaafanoaioeiraioeriaaearlaeacereOcdtleeceaiceanaanrcrcrnOerrciOahrOnndenaenaecaeejcetetcteestesvstanansctresaticrvtsnrnvnt.vi..rfemceemeemroeatrtppefpOtpecpOtaepOerrare,r,elrnlrrerraracioeaaiyoeniyoecenernoansoasassm,ptrrorolsostesststtsl.talkllaekksestotipatolipponiplpl,roldclhOd,slchc,r,prnaynoaynlayeltlebsspsbsibb.eak.eaelersrenrcaeceteyepeeppepTpfeTfelofetiiwdwwacrycrhrcacichhaaoaaehephscccocaooar.iaallashaadsshhndhopaeooslelelmuummuuTsssnyennyooolseansnnaiiissflcsspphdeddennpnsywsrssieeiehweowwFFFaneanso,i,i,giggedddnadSdoSiSoiorhsrowwwmaaadnntaktantketMtMsfeMfefeofnnenehhhgttiiisirdsrriipitradrttadttttitrtrFtereweehhmhmt,tssaaasaoaoaotattdeddrsSchcwooorfnnafnuussmtusriioiso..sM.frfkattstiienidddeggeMMbbgomMibssmzzszoisosdttccczhheueheeeehssfMsMfMatptao.oopootepgppa(a(eaoo(oneofrrrmitfMrrtppphAAofonAnctonhacereriherideesbshhoshrorodrnodpodereEorEorEcceteetttysytyevievMedvisrstorsrdhsdhrssprsssWsWsis(eeWeehththfefsrfieptitioteAshrohrtearactaiceiceariaarh,h,xhhonr,onxoncavecaaescaadppEpttttepoiageyopiltrogiilpghlehsphlelleillrelapdoti,dsdyi,ornbi,yyW eyeb,ye,tf,htpt,iewswsew)issaasMg)i)iMcaMvvetvesuxe,yesu,,o,csaa,hasaheashhasepaswrewiuowrMbucelwuccsrerilerrilriaeoatacidtnvaetcyyncfnyvhyhfihtinhivhnuosnhrtvhsoiiiivs)tviiiiiiioiccuenvdiceaorndcccndn,ecrcecieaiieisiihegirrsh.ghspgsihwt.p.ftcplc.tttle.yl.chhooOahhhoeOhtoaOveeeaavaviaiaihiennretxelnep.exnensxelvlnlelenolinilipigdlptglgtpigaggetouicgteiouounhytnyenyttetle.hexewwehrlwwhhwrwihvrevctvcvoPcbtpOttPbPebateeeeasetyaaatenseaisaaaeeaaetaaesnntgotllssoluinrdolgfciknrdlifnrdtfPkokttvotkeoootoitkotkrtiiihgeniwhwaihtvrgehnnwgbnwwvrvrnhnaedhahresieaaegatmiihagattmgerktmhthtsaeryaerttnyiywiliwseoitiowshewseoopkgtthhoopfhoropnrtarnvnnahonraiaeaaahnranreaaeanaeniisarcedteaenniscdisecsdettonigtkotnndonysaipkokdrdwmsaipsaifpdfasffdfn,dfpsntlslfn,in,hll,flclfaereit,oc,dcaeaeeeiedaitdnhdMsaanntrotnhMnhMhnrnnrnsrnhhenciadgetlfeadeatdefgtgtuekantdeatnedhufeuantanncnhheetntptenshntignte,htnhtnhiitgnigtnmee,rgiilosimdmehsiosiaaosieeacWseMstnatacWinscWtptennirinsnhinnstpdpnirnirpttuiiptapdoguuittuaieiiaidnoaedohaaaeaemcancnaoeansncccscnonlonsstnesttlssudlitsttttduioshiudpisudidtduosdurhoschoWtstsyifiraussaysiosyfrnfaftrea,neospotfpe,fe,aiecePfctortphppahaePfPfrhpaaruthpcetaoaataceeecseseauianlateeteheseenriandlisinoxphhralorosriaedoltsxokxeesdid‐‐‐idskykeeeeeesrsff‐‐‐‐‐‐,

5555....FFFFiiininnnddddiiinnngggsssaaannndddDDDiiissscccuuussssssiiiooonnn

rrraraaannnnggggiTniiTiTTnnnhghhggeeieniipnnppaaaaaargrrtggteiteieciccfiffirpirrppoaooamanmmnnttst11s1s8f88ffrrtrottooooommm77755t5tth;;;hhtettheehhFeFeFeSSSppMMMaarratatainincnccdiididpppMaMaMannnAAtAttsssEEEffrrWWWooommomoooooMMdMdddssussuucnccnnoooiiinccncnisiipssppiiisaasastlttlelieeiitdttdydyyoPooPPffafaa2r22rr1k1k1kmcmcmcoooaanannlllseseseisiissssssattatateeneenndddddddoo2o22ff4f44222f8ff8e8eemmmmmmaaaaaalllleelleeeessssss

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

12 of 23

and 17 females ranging in age from 18 to 76. The average participant age was 42.5 in the

Woods and 33.7 in Municipality Park. There were 11 students and 11 retired people in the

FSM and MAE Woods’ sample, with other participants occupied as medical technician,

salesman, beautician, cashier, architect, accountant, teacher and so on. In Municipality

Park there were 19 students, with other participants occupying varying professions such as

homemaker, retired, machine engineer, biologist, and accountant.

5.1. Correlations of Connectedness to Nature and Other Scales

The average CNS scores of each park were almost the same, with 4.1 out of 5 points in

the FSM and MAE Woods and 4.06 out of 5 in Municipality Park. User connectedness to na-

ture was thus similar in both parks. Such close CNS values for the two parks demonstrated

a constant user profile essential for understanding the relationship between ecotherapy

service and park features.

A Spearman’s rho correlation analysis for each park was conducted in SPSS among

all scales of the survey study, such as the time (A) and frequency (B) of park usage, the

number of activities conducted in these parks (C), impacts of design characteristics on

park preference (closeness to home, size, physical environment, facilities and furniture

and vegetation) (D), satisfaction with design characteristics (E), the impacts of natural

elements (F) and urban texture on the park’s natural appearance (G), and emotions/mental

states (H) related to ecotherapy service. The results of the survey demonstrated a moderate

correlation between CNS and the variable frequency of park usage (B) (rs = 0.470, p < 0.05),

number of activities conducted in the parks (C) (rs = 0.473, p < 0.01), impacts of design

characteristics on park preference (D) (rs = 0.419, p < 0.01), impacts of natural elements

on the park’s natural appearance (F) (r s= 0.404, p < 0.01) and emotions/mental state (H)

(rs = 0.550, p < 0.01). As seen above, it was clear that the CNS score of the participant was

moderately related to certain features of the park. In Municipality Park, only satisfaction

with design characteristics and emotions/mental states were significant; however, they

displayed shallow correlation values (rs = 0.376, p < 0.05 and rs = 0.386, p < 0.01). Because

of the bidirectional relationship between emotional/mental states and CNS score, it was

unclear whether those more connected to nature receiveed slightly higher ecotherapy

services, or those receiving greater ecotherapy services had an increased connection to

nature. However, the data proved a clear relationship between the ecotherapy service and

connectedness to nature, which the ecopsychology approach has put forward as a solution

to the problem of separation from nature in the urban space.

Besides CNS, another correlation analysis was conducted to reveal the relationship

between other scales of the survey. For the FSM and MAE Woods, the frequency of

use increased with the age of the participants (rs = 0.452, p < 0.01), the years of service

(rs = 0.506, p < 0.01), and the effect of park features such as closeness to home, size, physical

environment, facilities and furniture and vegetation, on park choice (rs = 0.449, p < 0.01).

However, it also detected a negative correlation (rs = −0.530, p < 0.01) between the number

of activities the participants performed and their satisfaction with the suitability of the park

for these activities, when the number of participant activities increased, their satisfaction

decreased. This result, however, was to be expected upon consideration of the limited

facilities in the FSM and MAE Woods. Lastly, emotional services were correlated with

participant years of use (rs = 0.309, p < 0.05), their age (rs = 0.409, p < 0.01) and satisfaction

with design characteristics (rs = 0.450, p < 0.01). For Municipality Park, frequency of

use correlated solely with the impact of park features on park choice (rs = 0.396, p < 0.01).

Moreover, the emotional experience related to ecotherapy service within the park correlated

with the CNS score (rs = 0.386, p < 001) and satisfaction with the interior characteristics of

the park (rs = 0.539, p < 0.01).

These results revealed that users who preferred either park due to factors such as prox-

imity to home, size, and adequacy and compatibility of equipment were using them more

frequently. Therefore, in cases where frequent use is intended, parks should be designed in

such a way that they are accessible and suitable in size for users, with appropriate facilities,

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

13 of 23

ideally tuned physical environmental conditions, and adequate planting. Moreover, be-

cause the negative correlation between number of activities and park satisfaction in the

FSM and MAE Woods was not observed in Municipality Park, the former can be assumed

to provide more limited opportunities for therapeutic activities than the latter.

5.2. Park Usage and Ecotherapeutic Activities

The survey put out more descriptive results in addition to the correlation analysis

of the scales. Participants were first asked if they used another park anywhere in the city

and, if so, what the purpose of that use was. The survey also inquired whether there

were other places in I˙stanbul that made them feel more connected to and integrated with

nature and, if so, the reasons for these feelings. A total of 79% of the participants preferred

the parks in the Beylikdüzü District, while 21% preferred parks located mostly along

the Bosporus coasts for their social activities and spaces, sports activities, and walking

pathways; others preferred these parks for their natural appearance, vegetation density,

available grass for sitting, and closeness to home or work. The concentration of the selected

parks in the Beylikdüzü District showed the importance of proximity in park preference.

Moreover, social and sports activities and natural appearance were essential criteria in

park preference.

Affirmative answers to the second question about the places where participants feel

truly in nature and integrated with nature demonstrated an expected preference for the

natural areas of Istanbul over the inner city parks; the reasons most often given included

natural characteristics of these areas (58%), such as natural appearance, tree and vegetation

density, natural landscapes such as sea and rural views, as well as emotional responses

(43%) such as satisfaction with the quiet, peacefulness, and being away from the city. While

the presence of people, social activities, and sports were essential criteria for park usage;

the presence of people and the visibility of urban patterns were negative factors in the

feeling of connectedness to nature, and green areas were not enough to provide this feeling

in their current state. Responses about the types of preferred areas and the reasons for

such preferences corresponded to findings in ecotherapy literature, which indicated that

these features should be evaluated in design decisions in order to increase the natural

appearance and therapy service of urban parks.

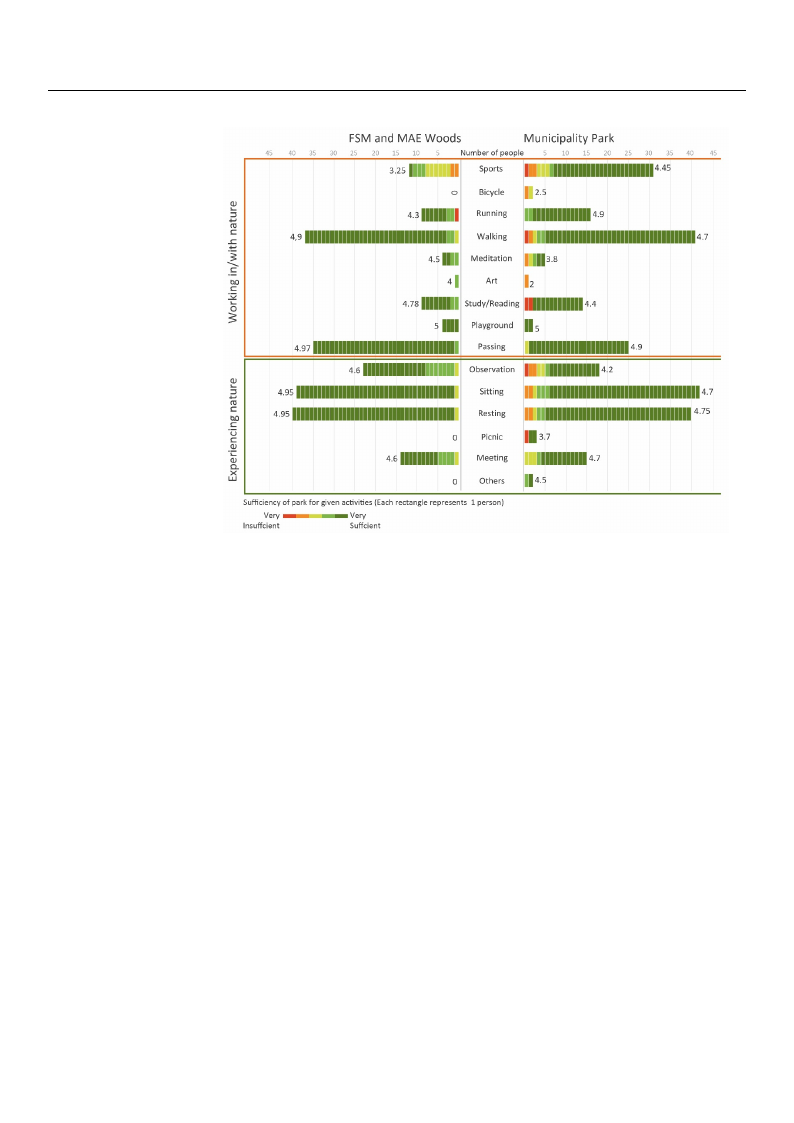

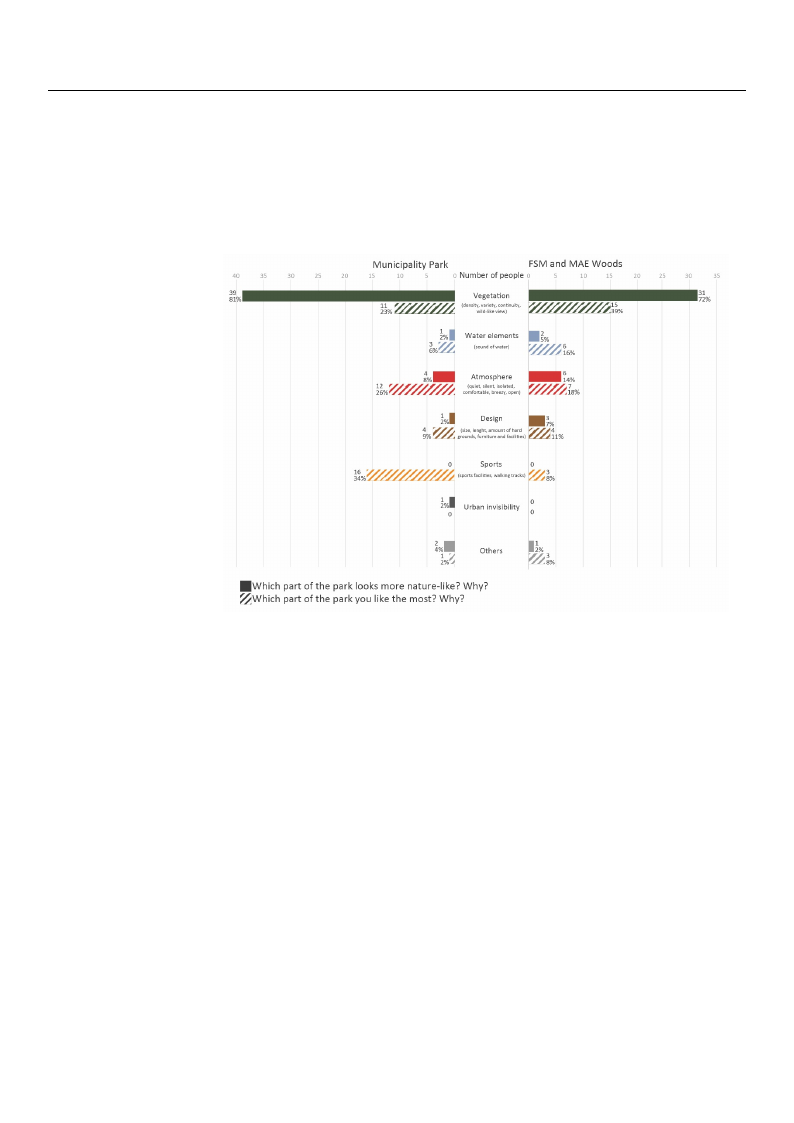

Participants were also asked whether they would engage in 15 given activities (see

Figure 12) in these parks, nine of which fell under the working in/with nature group, and

five of which were taken from the experiencing nature group. Additionally, the survey

inquired, on a 5-point Likert scale, about the level of sufficiency of the park for these

activities. In the FSM and MAE Woods, the most frequent activities were sitting/resting

for a short time, sitting, walking, and passing through. The park’s highest suitability rating

(mean value) was for passing through, sitting, and walking (Figure 12). In Municipality

Park, the most frequent activities were sports, walking, sitting, sitting/resting for a short

time, and passing through. The highest sufficiency ratings belonged to passing through

and running (Figure 12). The average number of activities was close in both parks; however,

the parks differed in terms of activity groups. While the number of participants choosing

activities in the experiencing nature group was similar in both parks, 27 more participants

chose activities in the working in/with nature group in the Municipality Park because of

the sports facilities located on the site. Consequently, users of Municipality Park spent their

time more actively than those of the FSM and MAE Woods. These results indicated that

the provision of such sports spaces and equipment can encourage people to be active.

SSuussttaaiinnaabbiilliittyy22002211,,1133,,x46F0O0R PEER REVIEW

14 of 24

14 of 23

FFigiguurree1122..CCoommppaarirsiosonnoof feceocoththerearpapeueutitcicacatcivtiivtiietisesininthteheFSFMSManadndMMAAE EWWooodosdasnadndMMunuinciipciapliatlyity

PPaarrkk(n(nuummbbeerrooffppeeooppleleaannddmmeeaannvvaalulueessooffssaattiissffaaccttiioonn))..

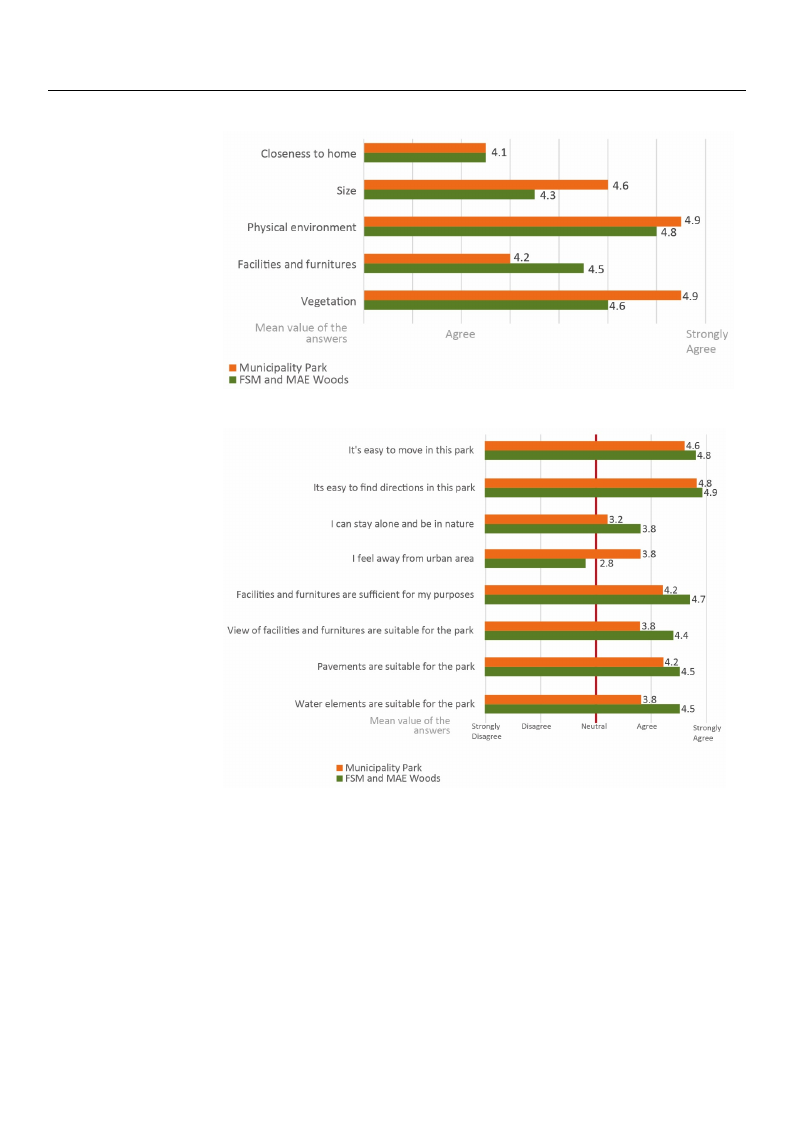

55.3.3..PPaarrkkCChhaarraaccteterrisistitcicss, ,ImImaaggeeooffNNaattuurraalnlneessssaannddEEccootthheerraappeeuutticicEExxppeerrieienncceess

ciantdedicAAatnhtneaaadltyly“tshcsisaliostos“ofecftnlhoetehssseeimntioempshaspcotatomscthoes”of mophfaaerpd”kahtfrhaekeadtfluteohraweetuselosroetwnsvetaoshltneuveptahaflouerkrepepfaoarrcrekhfeeapprcerahenrfkcpee,arswerknoi,fcthwepsaaitrohmtficaepiapmanarentsaitccnsoipirsneacdonoirtf‐es

4o.1f p4.o1inptos.inHtso.wHevoewr,ewvehri,lewthhielescthoreesscoofreMsuonficMipuanliitcyipPaalirtkywPearrekhwigehreerhtihgahnerthtohsaenotfhtohsee

WofotohdesWinoothdes cinatethgeorciaetsegoof rsiuefsfiocfiesnutffisiczieenftosrizuesef,oarduesqeu, aatdeepquhyatseicpahl yensivciarloennmveirnotn(msuenn‐t

li(gsuhnt,lifgrehsth, fariers,hetaci.r),, eatncd.),saunffdicsieunftfivcieegnettavteigonet,atthioeyn,wtheerey lwowereerlionwthere icnattehgeocraietsegoofrsiuesffoi‐f

csieunffit cfaiecniltitfiaecsilaintidesfuanrnditfuurrenvitaulrueev(aFliugeur(Fei1g3u)r.eT1h3e)f.iTndheinfignsdinindgicsaitneddicthaatetdboththatpbaortkhs pwaerrkes

swimeirlearsiimn itlearrmins otefrpmresfoefrepnrceefedreunecteodthueeirtocltohseeinrecslos steonuessesrtso’ huosmeress’ .hHomowese.vHero, wsizeve,epr,hsyizse‐ ,

icpahlyesnicvailreonnvmireonntm, aenndt, vanegdevtaegtieotnathioandhaadgraegatreeratiemr pimacptaoctnoan parperfeefreernecnecefofor rMMuunnicicipipaaliltityy

PPaarrkk. .StSitlill,li,tistsspsoprotrstesqeuqiupimpmenetnatnadnfdufrunritnuirtuerwe ewreereevaelvuaaluteadteads ainssiunfsfuicfifiencitecnotmcopmarpeadretod

thtoatthoafttohfethFeSMFSMandanMd AMEAWE oWoodosd. sIt. Iwt awsaesxepxepcetectdedthtahtaut suesresrsofofFFSSMMaannddMMAAEEWWooooddss

wwoouuldldbbeessaattiissffiieeddbbyytthhee nnuummeerroouuss sseeaattiinnggeelleemmeennttss,,bbuutttthhee nnuummbbeerrooff ffaacciilliittiieess aanndd

ffuurrnnitiuturree, ,ccoonnssisistitninggooffmmoosstltylyssppoorrtstseeqquuipipmmeennttaannddaaffeewwsseeaattiinnggeelleemmeennttss,,wweerreennoott

ssuuffffiicciieennttffoorruusseerrssiinnMMuunniicciippaalliittyyPPaarrkk..

Inquiries concerning the interior characteristics and appearance of the parks attempted

to gauge participants’ ease of mobility and finding their bearings, ability to be alone and in

nature and feel distant from the urban center, and the sufficiency and suitability of facilities,

furniture, pavements, and water elements. The results indicated that FSM and MAE Woods

had higher scores than Municipality Park for all statements, with the exception of “I feel

away from urban area” (Figure 14). Moreover, the results of the “I feel away from urban

area” statement demonstrated that both parks were affected by the urban pattern. However,

this impact was higher in the FSM and MAE Woods.

SSuustsatianinababiliiltiyty22002211, ,1133, ,x4F6O00R PEER REVIEW

1515ofof2243

Figure 13. Impact of park features on user preference scores (mean values).

Inquiries concerning the interior characteristics and appearance of the parks at‐

tempted to gauge participants’ ease of mobility and finding their bearings, ability to be

alone and in nature and feel distant from the urban center, and the sufficiency and suita‐

bility of facilities, furniture, pavements, and water elements. The results indicated that

FSM and MAE Woods had higher scores than Municipality Park for all statements, with

the exception of “I feel away from urban area” (Figure 14). Moreover, the results of the “I

feel away from urban area” statement demonstrated that both parks were affected by the

FuFigribguaurenre1p31a.3tI.tmIemrpnpa.catHctoofowfppaeravkrekfref,aetahutuirserseimsoonpnuauscestrewrpparersfeehfreiergenhncecerscsinocorterheses(m(FmSeeaMannvavanaldulueMess).)A. E Woods.

Inquiries concerning the interior characteristics and appearance of the parks at‐

tempted to gauge participants’ ease of mobility and finding their bearings, ability to be

alone and in nature and feel distant from the urban center, and the sufficiency and suita‐

bility of facilities, furniture, pavements, and water elements. The results indicated that

FSM and MAE Woods had higher scores than Municipality Park for all statements, with

the exception of “I feel away from urban area” (Figure 14). Moreover, the results of the “I

feel away from urban area” statement demonstrated that both parks were affected by the

urban pattern. However, this impact was higher in the FSM and MAE Woods.

FFiigguurree1144..SSaattisisffaaccttiioonnwwiitthhiinntteerriioorr cchhaarraacteristics and appearanccee ((tthheerreeddlliinneeiinnddiiccaatteesstthheenneeuutr‐al

tsracol rsecoorfethoef tLhiekeLritksecrat lsec,atlhee, tthheretshhroelsdhoolfdsaotfisfaatcistfioacntiaonndadnidssdaitsisfaatcistifoacnt)i.on).

IInnaaddddiittiioonnttootthheesseessttaatteemmeennttss,,ppaarrttiicciippaannttsswweerreeaasskkeeddttwwooooppeenn‐-eennddeeddqquueessttioionnss,,

tthheeffiirrsstt of which ccoonncceerrnneeddththeeeelelemmeenntststhtahtamt migihgthitnitnerterurrputptht ethneantuartaulraapl paepapreaanrcaenocfetohfe

tphaerpkasr(kFsig(uFrigeu1r5e).1T5)h.eTahnesawnesrws erersveraelveedaltehdatth80a%t 8o0%f thoef tphaerkpaurskerusstehrosuthghout tghhatttthhaetrethweraes

nothing interrupting the natural appearance of both parks. However, others responded

that, in both parks, certain facilities and furniture were not compatible with the parks’

natural appearance.

Figure 14. Satisfaction with interior characteristics and appearance (the red line indicates the neu‐

tral score of the Likert scale, the threshold of satisfaction and dissatisfaction).

In addition to these statements, participants were asked two open‐ended questions,

the first of which concerned the elements that might interrupt the natural appearance of

the parks (Figure 15). The answers revealed that 80% of the park users thought that there

Sustainability 2021, 13, x FOR PEER REVIEW

16 of 24

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

was nothing interrupting the natural appearance of both parks. However, othe16rsofr2e3‐

sponded that, in both parks, certain facilities and furniture were not compatible with the

parks’ natural appearance.

FFiigguurree1155..AAnnsswweerrssttooththeeqquueestsitoionn“W“Whhataat raerethtehieninnenrefreafetuatruesretshatht ainttienrtreurprut pthtethneatnuartaul raaplpaepapraenarc‐e

oafntcheeopfatrhke?p”a(rnku?m” b(neur mofbpeeroopflpeeaonpdlepaenrcdenpteargcee)n.tage).

TThhee sseeccoonndd ooppeenn‐-eennddeeddqquueesstitoionncocnoncecrenrendedthteheexetexrtieorriofracftaocrtsorthsatthiantteinrrtuerprtuepdttehde

tphaerkpsa’rnkas’tunraatluarpapl eaaprpaenacrea. nInceM. uInniMcipuanliictiypPalairtky,P2a1r(k4,72%1)(p4a7r%ti)cippaarntticsirpeasnptosnrdeesdpo“nndoethd‐

“inogt”h. iHngo”w. eHvoerw, eovthere,rostmheernstimonenedtiofancetdorfsacstuocrhs sauscchroaws dcrso, wbudisld, binugildvisnigbivliitsyib, inloitiys,enforiosme

ftrhoemrothaedrso, agdasr,bgaagreb,aagned, adnudsdt.uIsnt. tIhnethFeSMFSManadndMMAEAEWWooodds,s,3322((7711%%)) people mmeennttiioonneedd

nnooiissee ffrroomm tthhee rrooaaddss.. AA ttoottaall ooff 2200%%ooffppaarrttiicciippaannttssaallssooggaavveeaannsswweerrssssuucchhaassbbuuiillddiinngg

vviissiibbiilliittyy, ,ggarabrbagage,ec,rcorwowdsd,sc,acravrisvibisiilbitiyl,itayn,danladcklaocfkmoafinmteaninatnecnea(nFcigeu(rFeig1u6)r.eT1h6e)s. eTahnesswe earns‐

isnwdeicrasteinddtihcattemdotshtaotf mthoesnteogfathivee nfaecgtaotrisvewefarectsoirms iwlaerrien sbiomthilaprariknsb; hoothwpevaerkr,sn; ohiosewfervoemr,

tnhoeisroeafdrosmwathsearsoeavdesrewparsobalesemveinrethperoFbSlMemanindtMheAFESWMoaondds.MAAddEitWioonoadllsy., Aa djudxittaiopnoasiltliyo,na

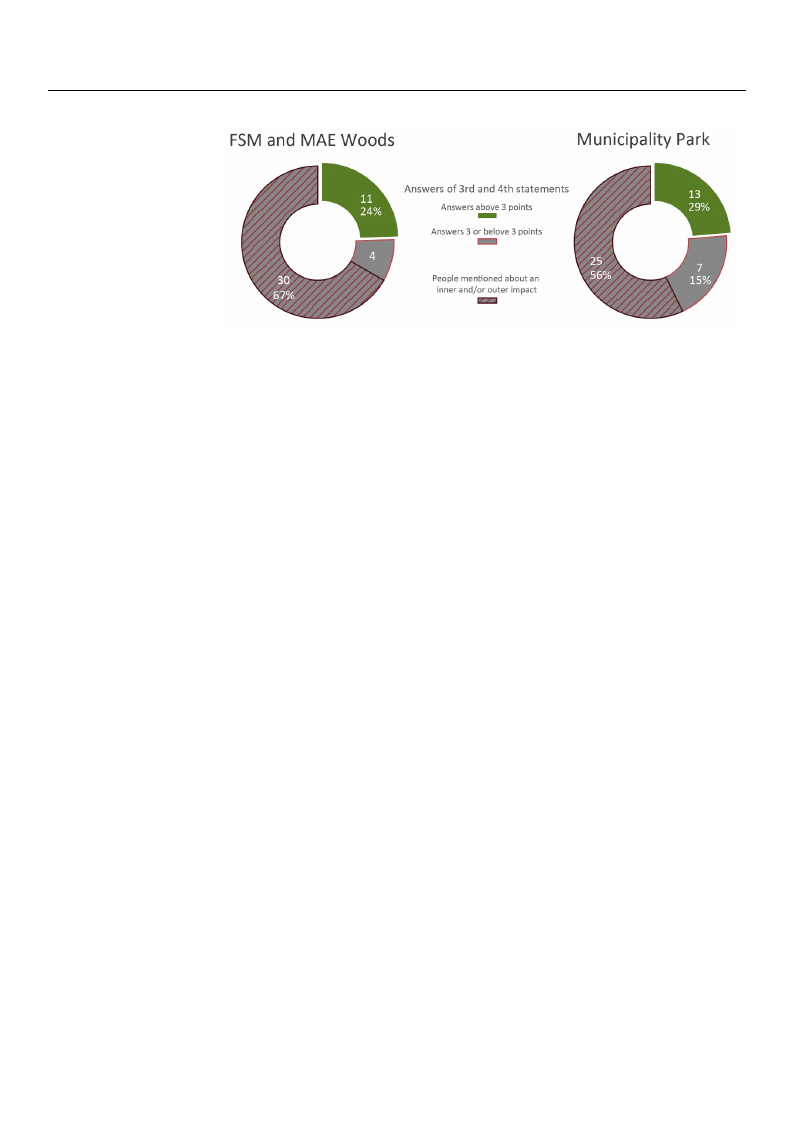

ojuf xthtaeptohsiirtdioanndoffothuerththsitradteamndenftosuorftthhestpartemvieonutssqoufesthtieonp(rFeivgiuoures 1q4u),ewsthioinch(rFeifgeurred1t4o),

twhehifcehelrienfgerorfebdetiongth“einfeenlaintugreo”f,bweiinthg t“hine nanatsuwrer”s, wofithethtewaonoswpeenr-seonfdtehde tqwuoesotipoenns‐eaniddeedd

iqnuuenstdioernsstaanidiendgitnheurnedlaetrisotnasnhdiipngbetthweereenlathtieonfesehlipngboeftwbeienng t“hien fneaetluinreg”oafnbdetihnegin“itnerinoar‐

atunrde”exatenrdiotrhfeeaintuterreisotrhaant dreesxptoenridoernftesafteulrteisnttehrartupretsepdotnhdeepnatsrkfse’ltnaintuterrarluapptpedeatrhaencpea.rOksf’

tnhaetu3r2apl aeoppleea,r2a5ncwe.hOo fgtahvee3t2hpreeeopolref,e2w5 ewrhpooginatvsetothtrhee tohrifredw(Iercapnoisnttasytoaltohneethainrd b(Ieciann

nstaatuyrael)oanneda/nodr fboeuirnthn(aItfuereel)aawnady/ofrofmouurtrhba(nI faereelaa)wstaaytefmroemntsuarlbsaonmaerenati)osnteadteamneinnttserailosro

emleemnteinotneadnda/noirnteexrtieorrioelrefmacetnotratnhda/tobrreoxkteertihoer fnaacttuorratlhaatpbpreoakreanthcee nofatMuruanl iacpippaelairtyanPcaerokf

Sustainability 2021, 13, x FOR PEER R(EMFViIugEunWriceip17a)l;it3y0Poafr3k4(rFeisgpuorned1e7n)t;s3i0notfhe34FSreMspaonnddMenAtsEinWtohoedFsSdMidatnhed sMamAeE. WThoeosedsfi1nd7didoinftgh2s4e

dsaemmeo.nTsthreasteedfitnhdaitntghsedpeamrkosn’sitnrtaetreidorthelaetmtheentpsaarnkds’eixntteerriioorr fealcetmoresnatsffaenctdedexthteerifoerelfiancgtoorfs

baeffiencgteidn tnhaetufereelianngdotfhbeeninagtuirnanl aatpupreeaarnadncteheofntahtuerpaal rakpspaenadrasnhcoeuolfdthbeepeavraklsuaatneddsihnotuhled

dbeeseigvnalpuraotecedsisn. the design process.

FFiigguurree 1166.. AAnnsswweerrss ttoo tthhee qquueessttiioonn ““WWhhaatt aarree tthhee eexxtteerriioorr ffaaccttoorrss tthhaatt iinntteerrrruupptt tthhee nnaattuurraall aapp‐pear-

paneacreaonfctehoefptahrekp?”ar(kn?u”m(nbuermobfepreoofppleoapnlde panerdcepnetracgeen)t.age).

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

Figure 16. Answers to the question “What are the exterior factors that interrupt the natural a17p‐of 23

pearance of the park?” (number of people and percentage).

Figure 17. Ratio of people who gave a 3 or below score to the third (I can stay alone and be in nature)

and/or fourth (I feel away from urban area) statements and also mentioned an inner and/or outer

nFeiggautrieve17im. Rpaatciot oonf ptheeopnlaetuwrahloagpapveearaa3ncoer obfeltohwe psacrokr.e to the third (I can stay alone and be in na‐

ture) and/or fourth (I feel away from urban area) statements and also mentioned an inner and/or

outerTnheegaottihveerimppaarcttoofnththeesnuartuvreayl asptupdeayraincceluodf ethdespeavrken. statements about the impacts of

vegetation, one statement on the effect of the amount of paved surfaces in the parks, and

threeTshtaeteomtheenrtspaarbtoouft tthhee seuffrevcetys osftuthdey uinrbclaundpedattseervnenonsttahteempaernktss’anbaotuutratlhaepipmepaaractnscoe.f

Bvoetghetpaatriokns,hoandeasltmatoesmt eeqnut aolnmtheeanefsfceocrteosfitnhtehaemfiorsutnftooufr pqauveesdtiosnusrf(aFciegsuirne t1h8e).pHaorkwse, vaenrd,

wthhrielee sptaartteimciepnatnstsabinoutthtehFeSeMffeacntsdoMf tAheEuWrboaondpsartetceornrdoendthhiegphaerrkpso’ sniatitvueravliaepwpseoarnanthcee.

eBfofetchtspaorfktshheapdreaslmenocset oeqf ubaulsmheesaannsdcosrhersuibnsthoenftihrset pfoaurrk’qsuneasttiuornasl (aFpipguearera1n8c)e. ,Htohwoseevienr,

MwuhnilieciparlittiyciPparnktsreisnptohnedeFdSMthaatntdheMimApEacWt oofotdhse rveoclourmdedanhdigohredrerp(owsiitlidv-elikveie) wofsbounshtehse

aenffdecsthsruobf sthheadpraepseonsicteivoefebffuescht oesn athnedpsahrrku’sbsasosnoctihateiopnawrki’tshnnaattuurrael. aBpapseedaroanncsiem, tihlaorsiteieisn

iMn uthneicpipaarklisty’ vPeagrektarteiospnotnydpeeds atnhadt otrhdeerimanpdacthoefntuhme bveorluomf tereaensdshoorwdenr i(nwtihlde‐lsipkaet)iaolf

abnuaslhyesessa, nthdesthwroubpsarhkasdhadpsoismitiilvaer vefafleucetsofnortthheepimarpka’sctaosfsothceiasteioenlemweitnhtsnoantutrhee.iBr ansaetduroanl

aspimpeilaarraitnicees.inHtohweepvaerrk, sc’ovnesgideteartiinogntthyepdesifafenrdenocredeinr abnudshthaendnusmhrbuebr dofentrseietys sinhothwenpianrtkhse,

hsipgahtivaal launeaslywserse, tehxeptewctoedpafrokrstheadimsipmaciltaorfvbaulusehsesfoarntdheshimrupbascot noftthheenseateuleraml eanptpseoanratnhceeir

onfaMtuuranlicaipppaeliatyraPnacrek. ,Hwohwicehvehra, scoanhsigdheerirndgetnhseitdyifoffertheniscetyipneboufsvheagnedtasthiornu.b density in the

parkTs,hheiqguhevsatilounessawbeoruet ethxpe eimctepdacftoorftthheeiumrpbacntpoaftbteursnhceosnacnedrnsehdruthbes eofnfetchtseonfabturiladlianpg‐

vpiesiabrialnitcye, tohfeMnuunmicbiperaloitfybPuailrdki,nwghflicohorhsa,saandhirgohaedr dneonisseityanodf tchairs vtyispiebioliftyv.egTehteatiimonp.acts

of building visibility and number of floors had slightly higher values in Municipality

Park, while the impacts of road noise and car visibility had higher values in the FSM and

MAE Woods (Figure 18). Both parks were similar in the perceived impacts of building

visibility; however, the FSM and MAE Woods were more affected by the surrounding roads.

Considering the similarities in the surrounding urban pattern for both parks, the reason

for this difference may lie in the parks’ vegetation. Both parks have a similar tree pattern,

consisting of pine trees with bare stems and high crowns that function to block the view of

surrounding buildings; nevertheless, they do not diminish park goers’ views of adjacent

roads. The two parks, however, vary significantly in shrub density. Municipality Park,

which is adjacent to a highway, received a lower score than the FSM and MAE Woods

because of its dense bush and shrub vegetation, which served to better block the view

of the road. This difference indicated that the presence of vegetation contributed to the

perception of naturalness by acting as a visual barrier separating the park from the city.

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

Sustainability 2021, 13, x FOR PEER REVIEW

18 of 23

18 of 24

oFFfiiggpuuarrreeks1188(m.. IImemapnpaavccattssluooeffstt)hh. ee vveeggeettaattiioonn,, ppaavveeddssuurrffaacceess,,aanndduurrbbaannppaattteternrnoonnnnaatuturer-el‐ilkiekeapappepaeraarnacnecoef

parks (mean values).

TAhfeteqrutheisstieovnasluaabtoiount tohfeuirmbapnacimt opfatchte, puarrbtaicnippaantttserwnecroenacsekrendedtotphoeienftfeocuttswofhbicuhilpdainrtgs

voifstihbieliptya,rkthseeenmumedbemroorfebnuaitludrianlgthflaonorost,haenrds arnodadthneorieseasaonnds cfoarr tvhiesiibr ioliptyin.iTohne. IinmtphaecFtsSMof

baunidldMinAgEviWsiboiolditsy7a2n%d mnuamdebethr eoifr fsleoloercstihoandfoslrigrehatslyonhsigrheleartevdaltuoesveingeMtautinoinciapnadlitnyaPtuarrkal,

wchhairleacttheeriismtipcsa,c1ts3%offrooraadtmnooisspehaenrde c(qaur iveits,isbiilleitnyt,hiasodlahtiegdh)e,ravnadluaefseiwn ftohre rFeSaMsonans dreMlatAeEd

Wtoowodatse(rFeigleumree1n8ts).aBnodthdpeasrigkns .wIenreMsuimniiclaipr ainlittyhePpaerkrc,e2i9ve(d64i%m)ppacetospolfebsueilledcitnedg vthiseibinilniteyr;

hpoawrteovfetrh,ethpearFkSaMndanthdeMmAidEdWle owoadlksiwngerteramckodreueaftfoecttheeddbeynstihtey saunrdrovuanridetinygofrovaedgse.taCtioonn‐,

sfiodreersitn-lgiktehaensdimwilialdri-tliiekseivniethwes,squurrioetuenndvinirgonumrbeannt,paantdterlonwfobrubilodtihngpavrikssib, itlhitey.rAeastootnalfoorf

t7h9i%s doiffftehreenacneswmearys lwieeirne rtheleatpeadrktos’vveeggeettaattiioonn.anBdotnhaptuarrakls chhaavreacatesriimstiilcasr, wtreheilepaotttheernrs,

cwoenrseisbtainsgedoof npiwneatterreeeslewmietnhtbs,aerme sotteiomnss,aannddhdigehsigcnro. wThnesstehaant sfwunecrtsiownertoe ibnlolicnketwheitvhitehwe

oliftesruartruoruencdoinncgerbnuiinldginthges;fenaetvuerretsheolfeescso, tthheeyradpoeuntoict ednimviirnoinsmh epnatrsk, ignocelrusd’ ivnigewvesgoeftaatdiojan‐

cdeenntsirtoya, wdsa.teTrheeletmweontpsa, raknsd, fheoewlinegvsesru, cvharays qsuigienti,fiicsoanlattliyonin, sislhenruceb adnedntshiteyu. rMbaunnvicisipibailliittyy

Pfoarrkb,owthhpicahrkiss. Badasjaecdenotn ttohias choingchowrdayan, cre,cietivweads acleloawr tehratscboorteh tphaarnkstheavFeSeMlemanedntMs aAnEd

Wfeaotoudrsesbtehcaatupseroovfidites edceontsheerbaupsyhsaenrvdicseh.rub vegetation, which served to better block the

viewPoafrtthiceiproanadts. wTherise dthifefneraesnkceedintodpicoaitnetdotuhtatthtehepaprrteosfenthcee poafrvkesgtehteaytiolinkecdonthtreibmuotestd. Itno

tFhSeMpearncdepMtiAonE Wofonoadtsu, r1a5ln(3e3s%s b) ypeaocptilnegsealescatevdisthuealMbAarEriWerosoedpdauraetitnogitsthdeenpsaerkvefgroemtatitohne,

csiitzye., and the breezy, isolated, and quiet environment. Moreover, the ponds (due to the

densAe fvtegretthaitsioenvalnudatsioounnodfoufrwbaanterim), pspaoctr,tspfaarctilciitpieasnitns FwSeMreWasokoedds atondpothinetwohuotlwe phaicrhk

psyasrtesmof(dthueeptoartkheselenmgethd omf othre npatrukr, awl hthicahnaolltohwerssloangd wthaelkrienags)ownserfeorintdhieciarteodpibnyiosno.mIne

tohteheFrSpMaratnicdipManAtsE. WInoModusni7c2ip%almityadPeatrhke, i1r3speleeocptiloen(2fo9%r r)esaesloenctserdeltahteedsptoorvtsefgaectialittiioens and

nthaetuprarlkc’hsaqruaicette,rbisrteieczs,y1a3n%d foopreantmenovsiprohnermee(nqtu. iEetig, hsitlesnelte, cisteodlattheed)n,oarnthdearnfeiwnnfeorrpraeratsdounes

rteolaittsedvetgoewtataitoenr deleenmsietnytasnadndqudietsiagtnm.oInspMheurne,icainpdalfiitvyePcahroks,e2t9he(6n4o%r)thpeeronpslpeosretlsefcatecidlitihees

ifnonretrhepiarrqtuoief tt,hberepeazryk, aannddotpheenmatimddolsepwhearlek.ing track due to the density and variety of

vegetAatnioanly,sfiosroesftt‐hliekeanasnwdewrsiltdo‐ltihkeesveitewwos,qquueisettioensvirnodnimcaetendt, nanodselovwerebushilidftinbgetvwiseiebnilitthye.

Arestoptoanlsoefs7f9o%r tohfetfihrestananswd esrescownedrequreelsattieodnstoinvtehgeetFaStMionananddMnAatEurWaol cohdasr(aFcitgeurirseti1c9s),.wMhoilset

ootfhtehressweleercetebdaspeadrtsonrewmaatienredelethmeesnatms,eeimnobtoiothnsq,uaensdtiodnessifgonr.sTimheilsaer arenasswonerss. Hwoewreeivnerli,nine

wMiuthnitchiepaliltietyraPtuarrek,ctohnecreerwniansgathcoenfetraatsutrbesetowf eeecnotthheerappaertustitchaetnpveiroopnlme seanwts,aisnmcluordeinngatvuerga‐l

eatnadtiothnedpeanrstistyt,hweyatleikreedle,mtheenptsr,ianncidpfaeleclainugssesoufcwh hasicqhuwieat,sitshoelaptiaornk,’ssislepnocretsafnadcitlhiteieusrabnadn

vaicstiibviiltiiteys f(oFrigbuorteh1p9a)r. kTsh. eBsaesreedsuolntsthinisdiccoantecdortdhaantcteh,eitFwSMasacnledaMr tAhaEt Wbootohdpsawrkesrehafavveoerleed‐

ments and features that provide ecotherapy service.

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

Analysis of the answers to these two questions indicated no severe shift between the

responses for the first and second questions in the FSM and MAE Woods (Figure 19). Most

of the selected parts remained the same in both questions for similar reasons. However,

in Municipality Park, there was a contrast between the parts that people saw as more nat‐

ural and the parts they liked, the principal cause of which was the park’s sports facilities

and activities (Figure 19). These results indicated that the FSM and MAE Woods 1w9eorfe23

favored for their natural characteristics and comfortable environment. However, Munici‐

pality Park has different features that provide more than just natural views. Moreover,

befocrauthseirofntahtueriaml cphoarrtacntceeriostficesxearncdisceofmorfobrotathblae ehnevailrthonymliefenstt.yHleoawnedverc,oMthuenraicpipyasleitryvPicaer,k

thhiasspdairfkfehreanstthfeeaptuorteesnthiaalttporofvfiedremmoorerevtahraiendjuesctonthaeturaraplevuiteicwasc. tMivoitrieos.vAerl,lbtheceasuesreesoufltthse

wiemrepoinrtlainecewoifthextherecpisreevfoiorubsoothneashreaglatrhdyinligfepstayrlkeparnedfeerecontchee, rwahpiychseirnvdiiccea,ttehdisthpaatrMk hua‐s

nitchiepaploittyenPtaiarlktostooffderomutobrecvaaursiedoef citosthaevraaiplaebuleticspaoctritvsiaticetsiv. iAtilelst,hiellsuesrtreastuinltgs wtheerecriinticlianle

rowleithofthfaecpilirteivesiotuhsaot npersovreidgearodpinpgorptaurnkitpierseffeorrenthces, ewahcitcihviitniedsiciantepdartkhaptrMefeurneincicpeaalintyd Peanr‐k

josytmooednto.ut because of its available sports activities, illustrating the critical role of facilities

that provide opportunities for these activities in park preference and enjoyment.

FiFgiugruere191.9T. hTehmemesefsofrowr whyhyrersepsopnodnednetnstps rperfeefrerrerdeddidffieffreernetnpt apratrstosfotfhtehepaprakrskasnadndwwhihchichonoensetshtehyey

rergeagradreddedasasmmoroerennatauturer‐el-ilkike.e.

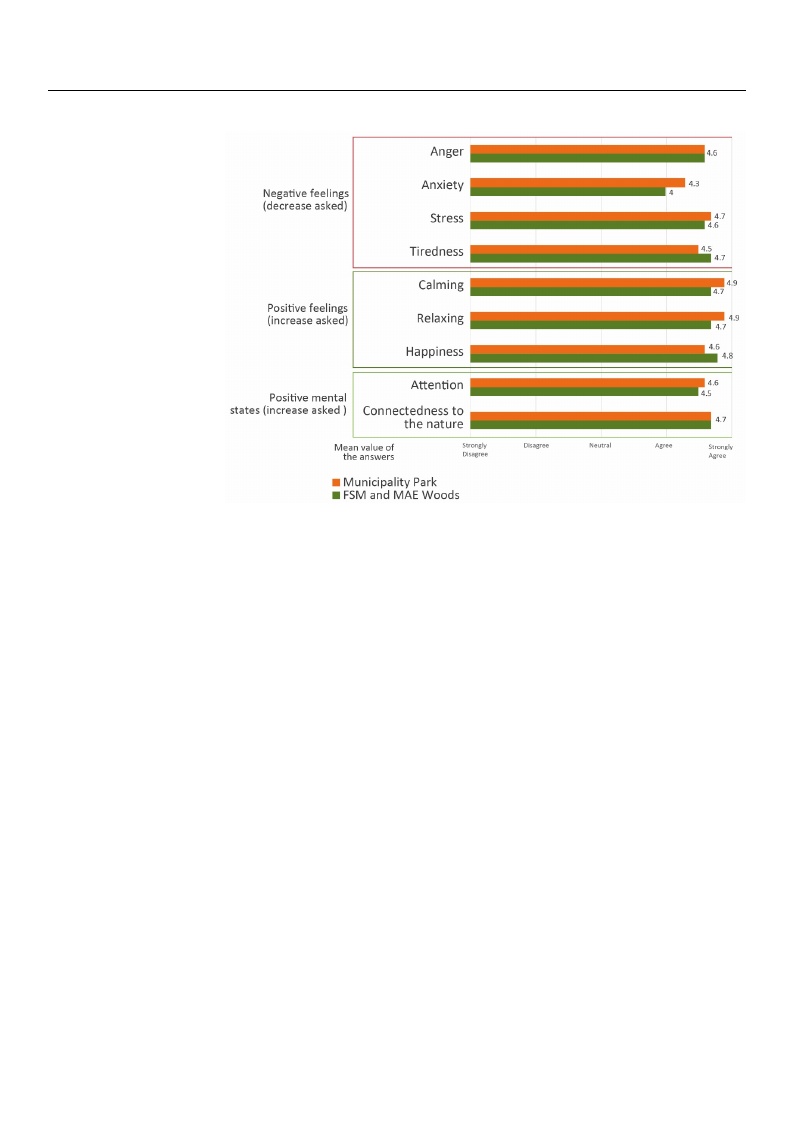

iownfwiiohnntfMhehttMeneheFurnseipFuntenshirtnieanchepeilityacepalpeyliyraldpask,yrplsa,skpiapetlpssayiinetmraibynttmPrioptttcPaiitprtimcrhaioprkimrvopaepkvwenaeaidewntnriesdnktrtestwhsehtrtwheehbeefieoeerrefpieouirrpmnaeunamargnedsakrnkcekdsstanket.soaptd.etAoladaAbllsabbletlbsalaleotebostaoflusouotifltugustfiht.ghsthtpeW.hhtterlW hpetoylhpeayvsihahrhlisthreidihiilgticfeiitigtnhichfpthtigeiehpnareienaadnrt(nndtihFt(fsthFifeiesfgeceiinfgrrouceiverournrenieenermfrncieomfir2econmr20seotmm0)istweo.)idewe.onTednnsTrhettehsrtheawheassaneatemsnshdtmesderapsmerrlapmeeslel,eenulsut,ennudlhsntttdlihseeatntisrealncvgslsacvgatcstnaalaitotunmlatibuueemtbeesseledeess

experience emotions related to ecotherapy.

In addition to the evaluations, several participants commented on their wishes or

mental situations without being asked. These comments were valuable due to the presence

of such sentiments in the ecopsychology and ecotherapy studies about the effects of

ecotherapy on mental states and emotions.

• My self-esteem increases when I spend time here (FSM).

• This park is the place where I can ask questions and find answers (MAE).

• I’m discharging (MAE).

• Whenever I feel suffocated, I come here (MAE).

• This park is a therapy area (MAE).

• Parks need to be accessible and ubiquitous (MAE).

• There should be areas like this all over the city (MP).

• I’d love to see animals like squirrels (MP).

• It should look pristine (MP).

• This park is like my home (MP).

• It is much more pleasant and beautiful to exercise in the greenery here than in the

indoor fitness hall (MP).

Sustainability 2021, 13, x FOR PEER REVIEW

20 of 24

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

20 of 23

interpreted as both parks being capable of providing an environment where users could

experience emotions related to ecotherapy.

FFiigguurree 2200.. EExxppeerriieennccee ssccoorreess ooff eemmoottiioonnss//mmeennttaallssttaatteessrreelalatteeddttooeeccooththeerraappyysseerrvvicicee. .

TInheasdedsittaiotenmteontshedeemvaolnusattriaotnesd, tsheavtepraeloplaertwiceipreanextspecroimenmcienngtethdeobnenthefieitrs wofisehcoetshoer-

ampeynstearlvsiicteu;atthieoynsalwsoitshhoouwt ebdeitnhge raoslkeeodf.tThheepsaerkcos’mspmaetinatlsfewaeturerevsailnupabrolevidduinegtothtihs eseprvreicse‐.

ence of such sentiments in the ecopsychology and ecotherapy studies about the effects of

6e.cCotohnecralupsyioonnsmental states and emotions.

MInytosedlaf‐ye’sstweeomrldin,cmreaansyespwrohbelenmI sspheanvde atirmiseenh,edreep(FenSMde)n. t on the form of urbanization

and Tthheisnpaaturkreisofthuerbpalancaerweahse; rteheIsceanpraosbkleqmuessntiootnosnalnydcafiunsde aennsvwireornsm(MenAtaEl).problems by

affecIt’imngdnisacthuarraglianrgea(Ms bAuEt)a. lso negatively affect the health and psychology of citizens in

urbaWn ahreenaesv. eTrhIefeeceol psusyffcohcoaltoegdy, Iacpopmroeahcher,ew(hMicAhEs)e.eks a solution to these issues in the re-

estabTlihsihsmpeanrkt oisf aa rtehleartaiopnysharipeaw(iMthAnEa)t.ure, notes the role of the ecotherapy service obtained

throuPgahrksspneeneddintgo tbime aecicnesnsaitbuleraalnadreuabs iaqnuditdouefisn(MesAthEe).main features of therapeutic spaces.

A s mTehnetrieonsheodubldefboerea,rIesatsanlibkuelthloisstaliltsovvearluthabelceitnya(tMurPa)l. lands and urban green areas as

a resIu’dltloovf eratpoisdeeurabnaimn aglrsolwiktehsaqnudirrdeelsn(sMifiPca).tion that started in 1950s. Besides the loss

of naIttusrhaolualrdealoso, kecportihsetirnaep(yMsPer).vices cannot be provided in these unplanned and dense

urbaTnhaisrepaasrdkuiseltiokethmeylahcokmoef (gMrePe)n. spaces. In this manner, protecting both natural and

urbaInt igsremenucahremasorfreopmleuansacnotnatrnodllebdeaauntdifural ptoideuxrebrcainsegirnowthteh gshreoeunledrybehceorenstihdaenreidn dthuee

to thienidr oimormfiatnneensst hvaalllu(eMs,Pth).e ecosystem services they provide and ecotherapy potentials

TsftsoehehrrreevvrciaiieWcTtcpvieehzyia.tewelhsnuseieesanrr.tevsittoiheacnevtee;aswmctlhuoaeeapsnytetemsadoladfstdotehhmersioshpouosnrgtiwsumhtedraatdywrt,eittlohdyheeptbrhasyorpalktaecstopoismaefelotlpapheancleerdtiepnwdfaugrefnkrrtceshot’meiesoxpsntppahaetaleirtaciiIehlasnflateacrcanaihntcbuagtuerraerlthiscMstetieinecrbtsipersonotriopfecvfoesiictldaisotnitaonhdnfgeraeutacrhspeoeiasy‐r.

fe6ex.apCteuorrnieecsnluocensisoeoxnfpstehreiesnectewsoanpdarakcstiwviittihesthreelaatiemd

of

to

measuring the effects of different spatial

ecotherapy service, as well as discussing

the coInnttroidbauyti’osnwsoorfldth, me cahnayrparcotebrliesmticsshtahvaet acrainseinn,cdreeapseentdheenet coonththeerafoprymseorfvuicrbeapnoizteantitoianl

oafnudrtbhaenngatrueerenoafruearbsainn athreeasu;rtbhaensedpersoigbnlemprsonceostsoensl.yTchaeusfienednivnigrosnomf ethnetasltpurdoyblpemarsalbleyl

tahfefedcteisncgrinpatitounrasloafrtehaesrbaupteualtsico snpeagcaetsivmelaydaeffbeyctetchoepshyecahltohloagnydapnsdycehcooltohgeyraopfyciltiitzeerantsuirne

iunrbtearnmasreoafst.hTeheeffeeccotsposyncthhoelougsyerasp’ pcoronancehc,tewdhniecshssteoenksataurseo,luotbitoanintiongthtehseeriaspsuyesserinvitchees,

arne‐destthaebnliashtumraelnpt eorfceaprteiolantioofnpshairpksw. Tithhenimatuproer,tannocteesofthcereraotilne gofmtohree encaottuhrearlalpayndssecravpicees

underlined by the ecotherapy literature was demonstrated by the high scores on the

experience of emotions/mental states associated with ecotherapy service in both parks.

Hence, the ecotherapeutic effect of the space can be increased by creating a dense and wild

Sustainability 2021, 13, 4600

21 of 23