Utah State University

DigitalCommons@USU

All Graduate Theses and Dissertations

Graduate Studies

8-2012

An Exploration of the Relationships Among Connectedness to

Nature, Quality of Life, and Mental Health

Peter Gelden Tauber

Utah State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd

Part of the Psychology Commons

Recommended Citation

Tauber, Peter Gelden, "An Exploration of the Relationships Among Connectedness to Nature, Quality of

Life, and Mental Health" (2012). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1260.

https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1260

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by

the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has

been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and

Dissertations by an authorized administrator of

DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please

contact digitalcommons@usu.edu.

AN EXPLORATION OF THE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG CONNECTEDNESS

TO NATURE, QUALITY OF LIFE, AND MENTAL HEALTH

by

Peter G. Tauber

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the degree

of

MASTER OF SCIENCE

in

Psychology

Approved:

Gayle S. Morse, Ph.D.

Committee Chair

M. Scott DeBerard, Ph.D.

Committee Member

JoAnn T. Tschanz, Ph.D.

Committee Member

Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D.

Vice President for Research and

Dean of the School of Graduate Studies

UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY

Logan, Utah

2012

ii

Copyright © Peter G. Tauber 2012

All Rights Reserved

iii

ABSTRACT

An Exploration of the Relationships Among Connectedness to Nature,

Quality of Life, and Mental Health

by

Peter G. Tauber, Master of Science

Utah State University, 2012

Major Professor: Gayle S. Morse, Ph.D.

Department: Psychology

The current study examined the relationships among connectedness to nature

(CTN), quality of life (QOL), and mental health (MH). Theory in biophilia and

ecopsychology has emphasized the importance of the human relationship with the natural

world for the health of individuals, our species, and our planet as a whole. Previous

research has documented the relationship between experiences in nature and outcomes of

health and well-being. However, scant research has examined the correlates of the

concept of CTN. Furthermore, no research has examined the relationship between CTN

and measures of well-being such as QOL or MH. In the current study, 267 undergraduate

students completed a series of self-report items measuring CTN, QOL, MH, and

demographic characteristics. Significant relationships between CTN and all categories of

dependent variables (QOL, MH, and demographics) were found. In addition, the

subcategory of CTN closely related to the desire for direct experiences in nature, NR

iv

experience was shown to have a stronger relationship to QOL and MH than overall

CTN—as evidenced by more significant correlations and by serving as a better predictive

model through multiple regression. QOL, MH, and demographic variables were

collectively found to predict 21% of the variance in overall CTN, while those same

variables were found to predict 35% of the variance in NR experience. Implications of

these findings based on previous research, limitations of the current study, and future

avenues of research are discussed.

(126 pages)

v

PUBLIC ABSTRACT

An Exploration of the Relationships Among Connectedness to Nature,

Quality of Life, and Mental Health

by

Peter G. Tauber, Master of Science

Utah State University, 2012

In recent decades, a new branch of psychology has emerged—ecopsychology. This field

looks at the complex relationship between human beings and the natural world. Previous

research has shown the importance of direct experiences in nature for the promotion of

human health and well-being. However, it is still not understood why these experiences

in nature carry so much importance.

It is possible that the concept of connectedness to nature (CTN) plays a role in this

relationship between nature and wellness. CTN is defined as feelings of close affiliation

with the natural world in a physical, cognitive, and emotional manner. Previous research

leaves open the possibility that these feelings of affiliation and connectedness may

contribute to well-being.

To try to better understand this idea, a survey was designed to measure CTN, quality of

life, and mental health. Since research of these ideas has never been performed before,

this should be considered an exploratory project. In this current study, 267

undergraduates at Utah State University participated.

Results indicated that certain aspects of mental health and quality of life were related to

overall CTN. First, relationships were found between mental health and quality of life

variables and one specific aspect of CTN which can also be thought of as the desire to

have direct experiences in the natural world. Second, demographic factors such as age,

gender, and ethnicity were all associated with CTN. Future research should try to

understand what things might contribute to CTN and to develop interventions which

might increase CTN and well-being.

vi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to extend my greatest feelings of appreciation and

gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Gayle Morse. Gayle, your support, encouragement, and wise

counsel throughout this process have been invaluable. You have been my rock, providing

not only academic guidance but personal and spiritual support as well. I do not believe

that I could have made it to this point without your compassion, strength, and wisdom. I

could not have asked for a better advisor and mentor. I extend my deepest bow to you.

I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Drs. Joann

Tschanz and Scott DeBerard. Through your guidance, I have learned how to transform

my writing from the flowery, descriptive prose consistent with my liberal arts

background into the precise, evidence-based style of scientific writing where claims are

always accompanied by supporting evidence. In addition, your insistence on

methodological and statistical rigor has challenged me to think critically about the

research process and greatly aided in my development as a scientist.

I could also not have made it to this point without the support of my family and

the unconditional love and acceptance of my parents, John and Suzy Tauber. Mom and

Dad, it was your continual support and warmth from the day of my birth until the present

that enabled me to grow and flourish. You have instilled in me the value of education and

the feeling of accomplishment that comes when hard work is met with success in any

domain. I am deeply grateful for your continued love, guidance, and support. I love you

both immeasurably.

I would also like to thank my friends at USU for their continued support and care.

vii

Krista, Ellen, Sarah, Justice, Morey, and James—thank you all so much for your support.

You provided me with advice and ideas when I needed them, a shoulder to lean on when

feeling weak, and companionship to celebrate the many good times that we shared. I

could rely on you to help me through difficult times, be they academic or personal in

nature. I simply could not have made it to this point without your support, smiles, and

thoughtfulness.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge my greatest inspiration for this entire

project—nature herself. Were it not for the days spent bobbing on my surfboard in the

Pacific, the nights underneath the limitless expanse of Utah’s skies, the moments of

unbearable beauty that accompany the rise and setting of the sun, and the countless

moments of awe that accompany my time in the green mountains and red rock desert, I

would not have my passion for this field and this idea.

Namaste—a deep bow to you all.

Peter G. Tauber

viii

CONTENTS

Page

ABSTRACT................................................................................................................... iii

PUBLIC ABSTRACT ................................................................................................... v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................. vi

LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................... x

LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................... xi

CHAPTER

I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1

II. LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................... 4

The Literature Review Procedure ................................................................... 4

Philosophical and Theoretical Underpinnings of Connectedness to Nature... 5

Measures Quantifying the Human-Nature Relationship................................. 9

Quality of Life................................................................................................. 16

Quality of Life and Connectedness to Nature................................................. 20

Mental Health and Connectedness to Nature.................................................. 24

Mental Health.................................................................................................. 31

Quality of Life and Mental Health.................................................................. 32

Concluding Remarks....................................................................................... 33

Specific Aims and Research Questions .......................................................... 33

III. METHODS ..................................................................................................... 35

Setting and Sample ......................................................................................... 35

Measures ......................................................................................................... 36

Procedure ........................................................................................................ 42

IV. RESULTS ....................................................................................................... 43

Descriptive Statistics....................................................................................... 44

Aim 1: Connectedness to Nature and Demographics ..................................... 44

Aim 2: Connectedness to Nature and Quality of Life..................................... 49

Aim 3: Connectedness to Nature and Mental Health...................................... 51

ix

Page

Aim 4: Multiple Regression............................................................................ 53

V. DISCUSSION ................................................................................................. 61

Demographics ................................................................................................. 62

Implications for Past Theory and Research .................................................... 62

CTN and Demographics ................................................................................. 63

CTN and QOL................................................................................................. 66

CTN and Mental Health.................................................................................. 70

CTN and Predictors......................................................................................... 74

Limitations ...................................................................................................... 75

Implications..................................................................................................... 78

Future Directions ............................................................................................ 79

REFERENCES .............................................................................................................. 81

APPENDICES ............................................................................................................... 91

Appendix A: Letter of Information............................................................... 92

Appendix B: Demographic Questionnaire ................................................... 95

Appendix C: Nature Relatedness Scale ........................................................ 97

Appendix D: WHOQOL-BREF ................................................................... 99

Appendix E: Histograms for Distribution of NR Scale Scores .................... 103

Appendix F: Histograms for Distribution of WHOQOL Scale Scores........ 106

Appendix G: Histograms for Distribution of SCL-90 Scale Scores............. 110

x

LIST OF TABLES

Table

Page

1. Examples of Items from Each Subscale of the NR Scale .................................. 38

2. Examples of Items from Each Subscale of the WHOQOL-BREF .................... 39

3. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample...................................................... 45

4. Descriptive Statistics for Nature Relatedness Scales......................................... 46

5. Correlations Between Connectedness to Nature and Demographic

Variables ............................................................................................................ 47

6. Descriptive Statistics of WHOQOL-BREF Compared to a Normative

Sample................................................................................................................ 49

7. Correlations Between Connectedness to Nature and Quality of Life

Variables ............................................................................................................ 50

8. Descriptive Statistics of the SCL-90 Compared to a Normative Sample .......... 52

9. Correlations Between Connectedness to Nature and Mental Health

Variables ............................................................................................................ 53

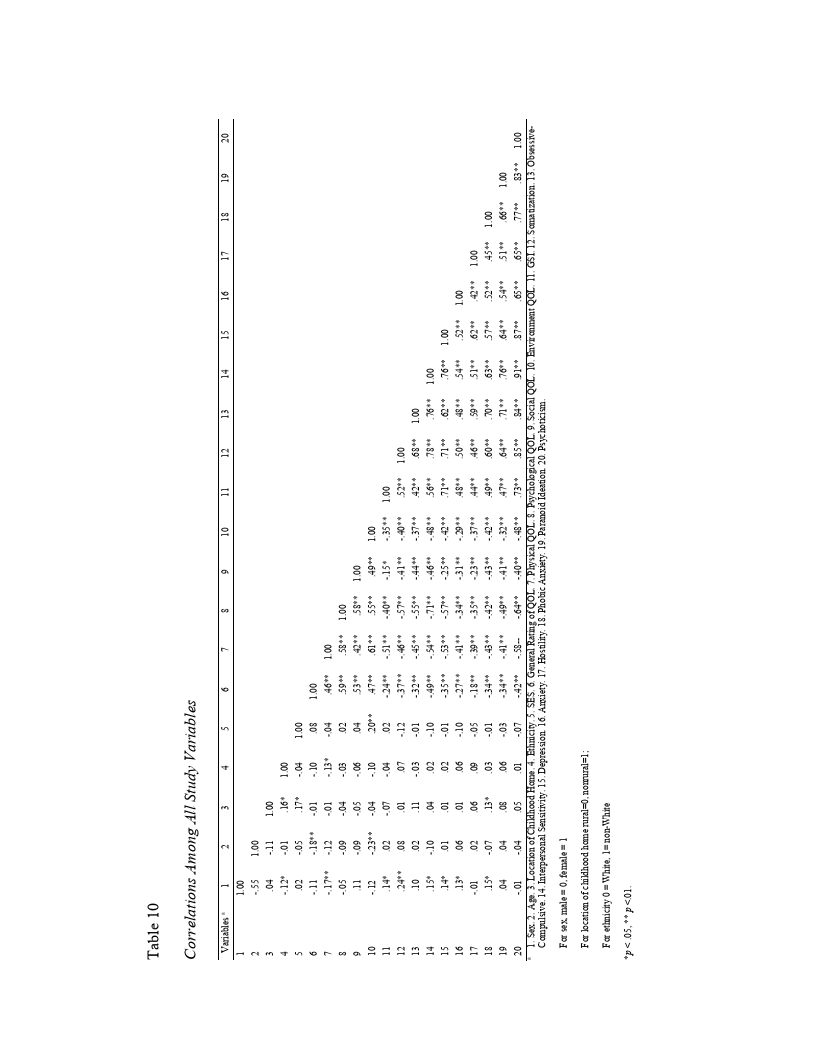

10. Correlations Among All Study Variables .......................................................... 54

11. Multiple Regression: Predicting Overall Nature Relatedness with

Demographic Variables, QOL Variables, and GSI............................................ 56

12. Multiple Regression: Predicting Overall Nature Relatedness with

Demographic, QOL, and Mental Health Variables ........................................... 58

13. Multiple Regression: Predicting NR Experience with Demographic, QOL,

and Mental Health Variables ............................................................................. 60

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure

Page

1. The Inclusion of Nature in Self scale................................................................. 13

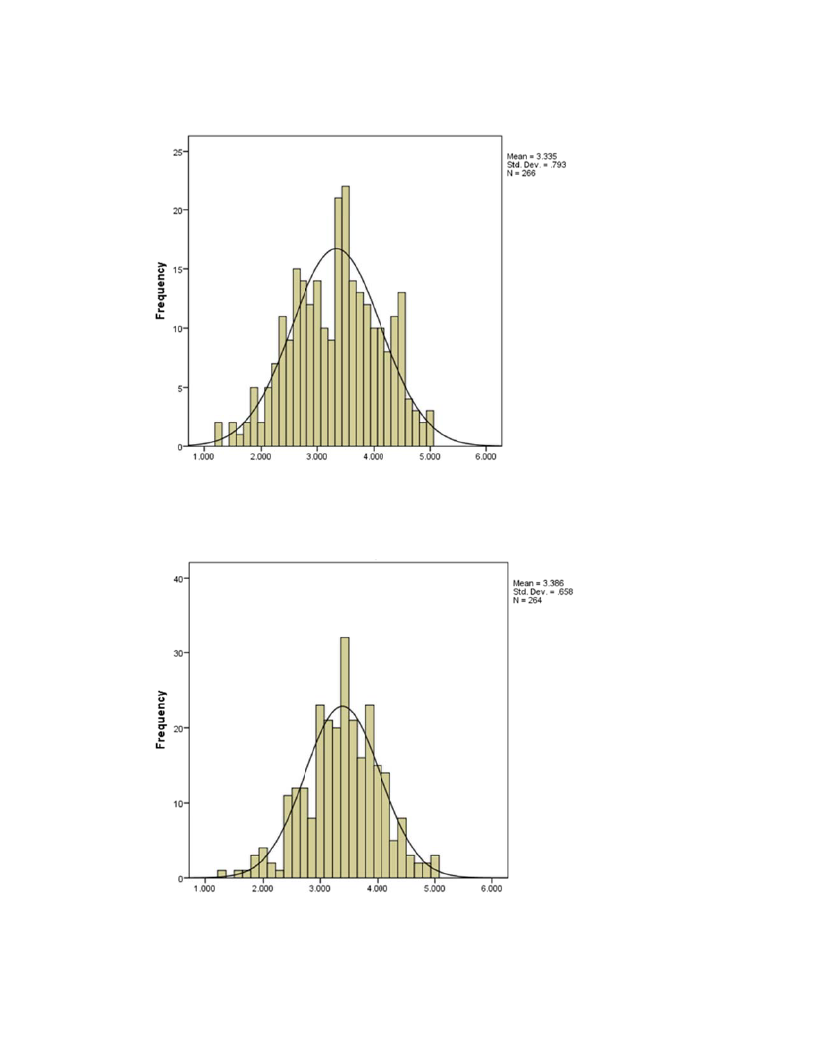

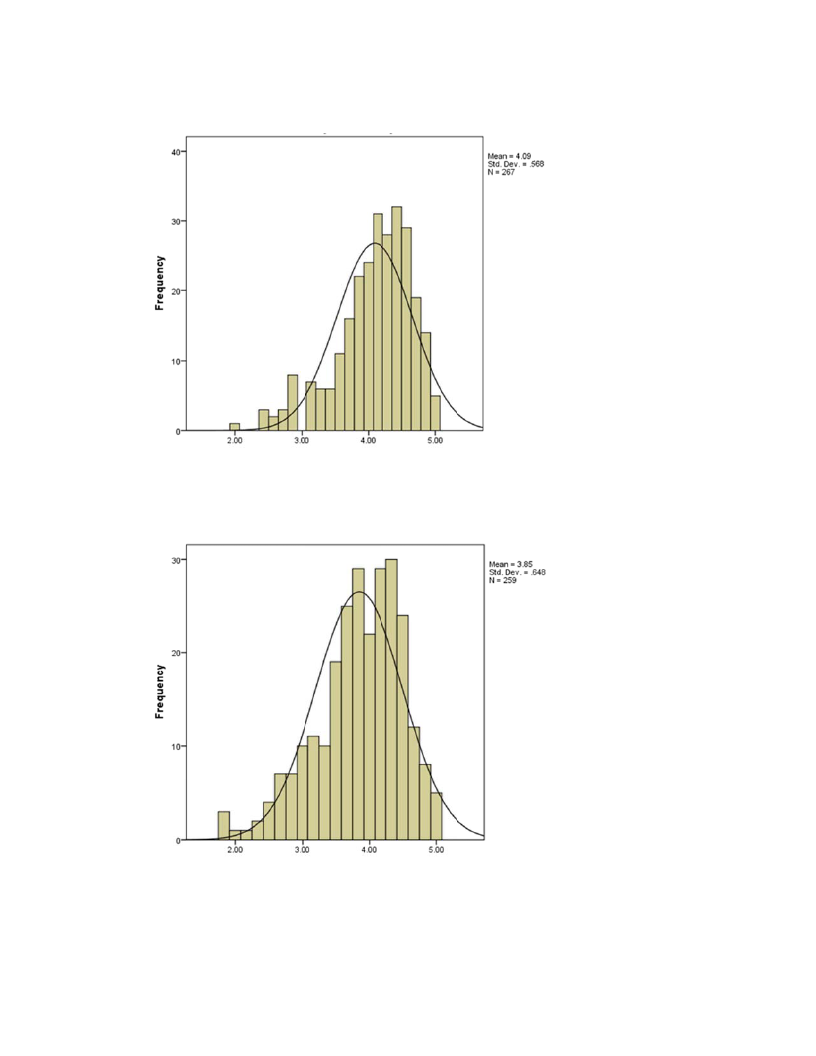

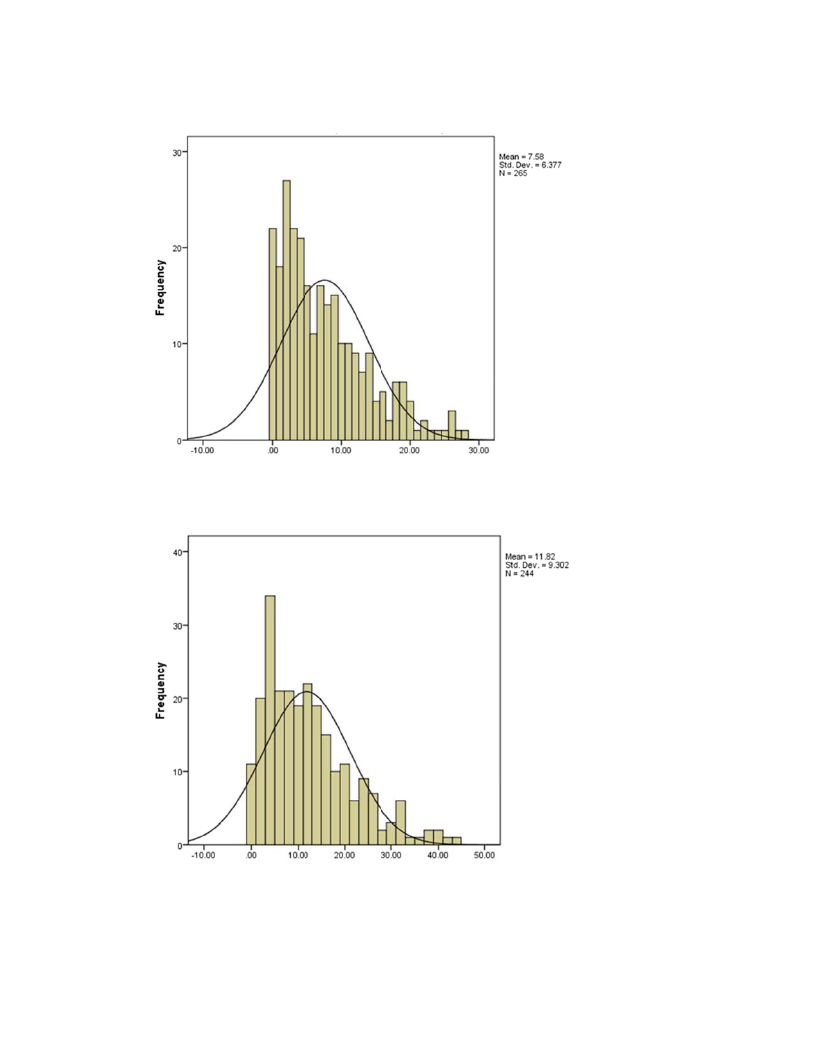

E-1. Distribution of NR “self” scale scores ............................................................... 104

E-2. Distribution of NR “perspective” scale scores................................................... 104

E-3. Distribution of NR “experience” scale scores ................................................... 105

E-4. Distribution of NR “overall” scale scores.......................................................... 105

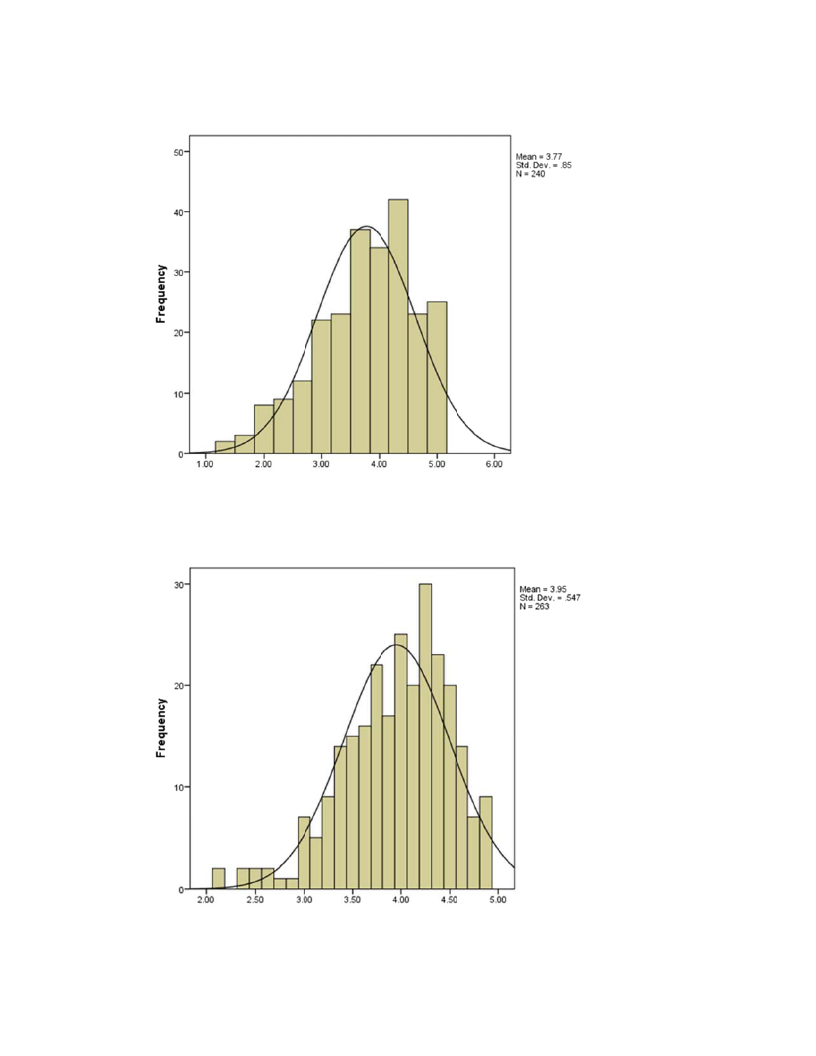

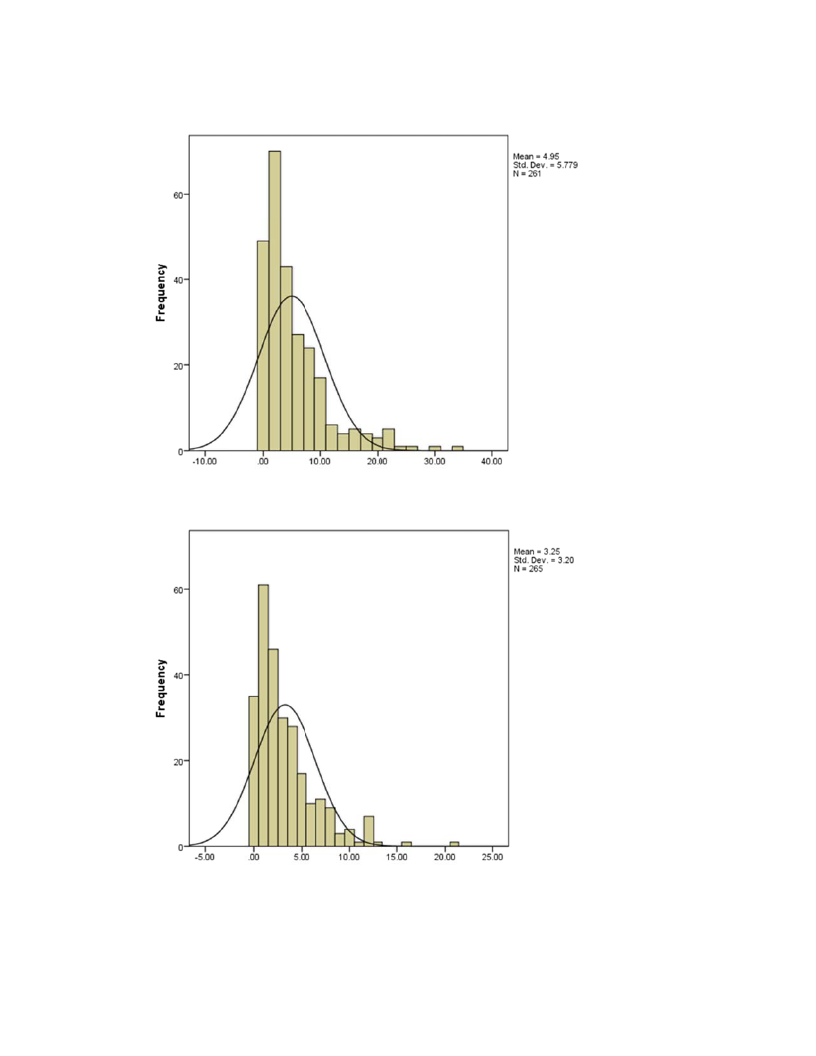

F-1. Distribution of WHOQOL “physical” scale scores ........................................... 107

F-2. Distribution of WHOQOL “psychological” scale scores .................................. 107

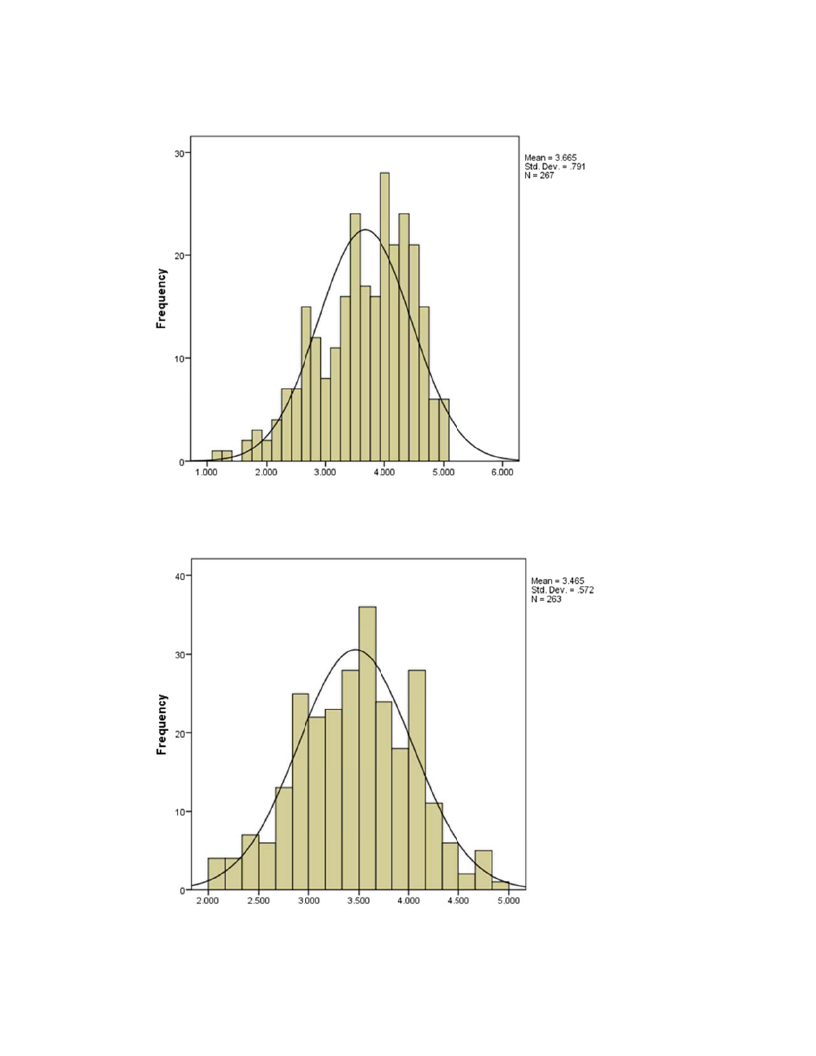

F-3. Distribution of WHOQOL “social relationships” scale scores.......................... 108

F-4. Distribution of WHOQOL “environment” scale scores .................................... 108

F-5. Distribution of WHOQOL “overall” scale scores ............................................. 109

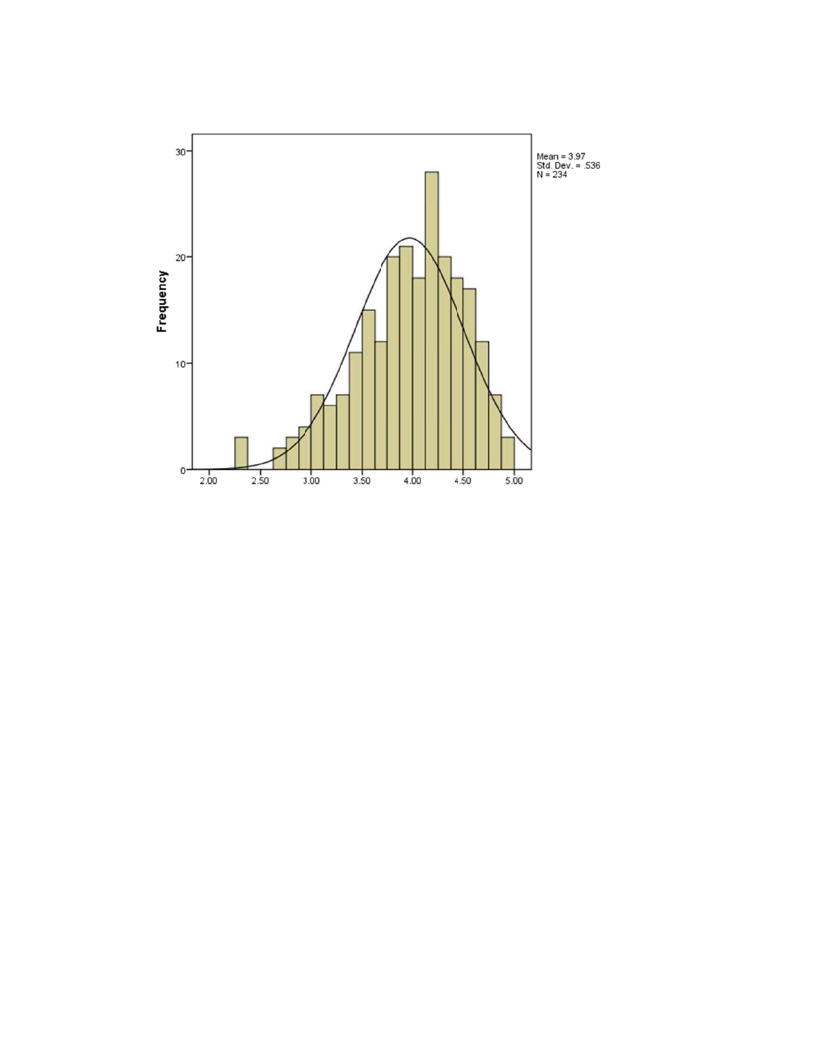

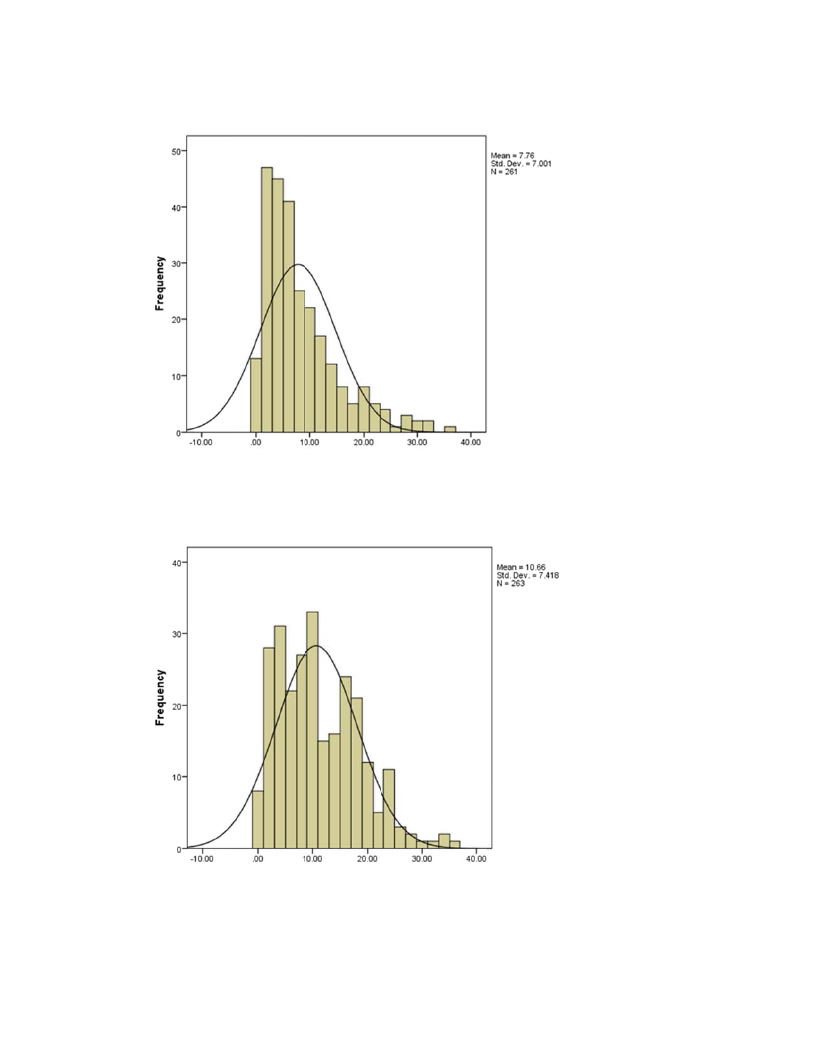

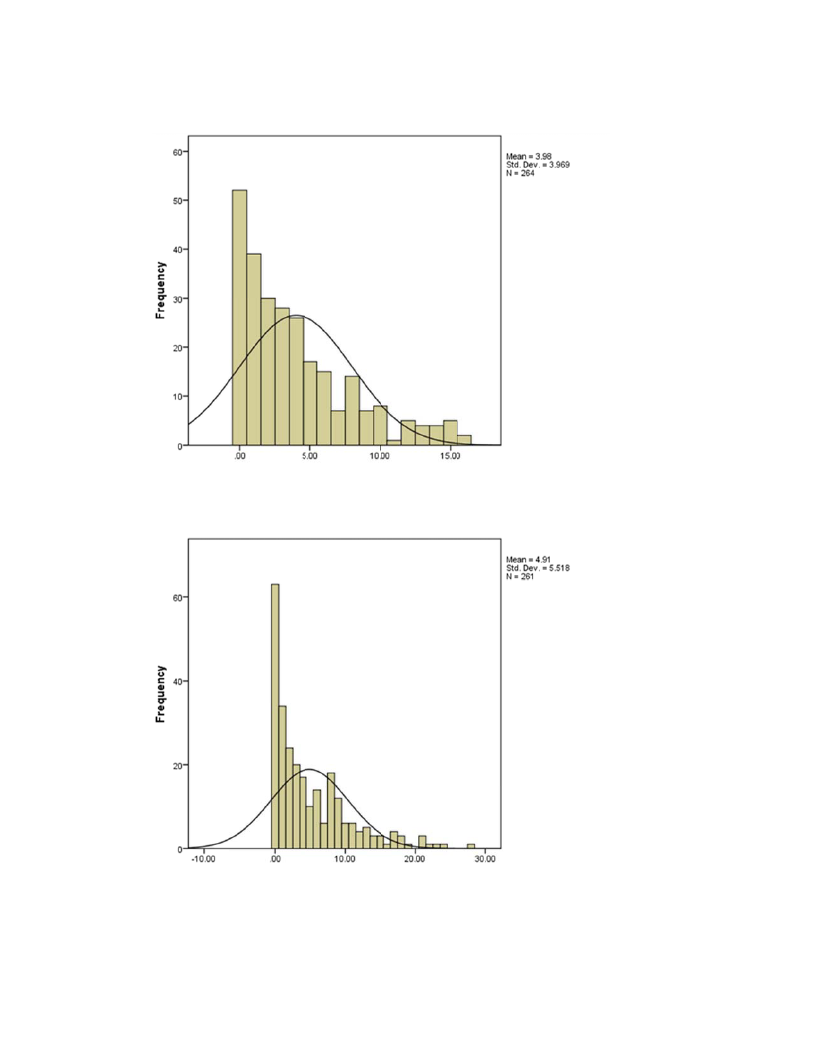

G-1. Distribution of SCL-90 “somatization” scale scores ......................................... 111

G-2. Distribution of SCL-90 “obsessive-compulsive” scale scores........................... 111

G-3. Distribution of SCL-90 “interpersonal sensitivity” scale scores ....................... 112

G-4. Distribution of SCL-90 “depression” scale scores............................................. 112

G-5. Distribution of SCL-90 “anxiety” scale scores .................................................. 113

G-6. Distribution of SCL-90 “hostility” scale scores................................................. 113

G-7. Distribution of SCL-90 “paranoid ideation” scale scores.................................. 114

G-8. Distribution of SCL-90 “psychoticism” scale scores......................................... 114

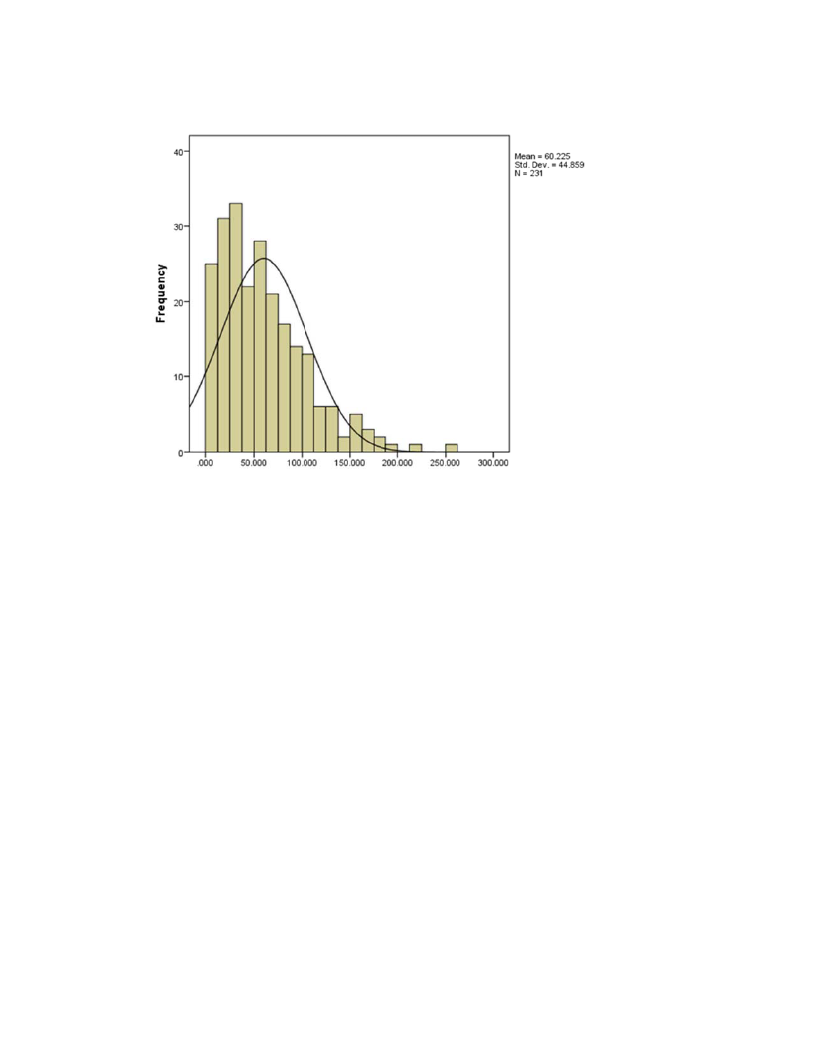

G-9. Distribution of SCL-90 “global severity index” scale scores ............................ 115

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Many consider the beginning of the modern environmental movement to reach

back into to the middle of the 20th century with the publication of seminal works like

Aldo Leopold’s (1949) A Sand County Almanac and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring

(1962), capitulating with a spate of national legislation in the 60s and 70s such as the

National Environmental Policy Act (1969), the Clean Air Act (1963), and the Endangered

Species Act (1973). Now we are witnessing a second resurgence in environmental

interest due to the salience of global climate change and the influence of high-profile

environmentalists such as Al Gore and films such as An Inconvenient Truth (Bender &

Guggenheim, 2006). The contemporary environmental movement has raised awareness

of the consequences of our planet-affecting actions on both our species and our planet as

a whole.

While the modern environmental movement in the United States is still relatively

new, other cultures have always valued the importance of preserving our land and

maintaining a balance between the natural and built environment. For example, those

who ascribe to traditional Native American beliefs typically do not recognize a separation

between their personal identity and the natural world; often both nature and their

environment are included in their sense of self. For these people, harm committed against

nature and the environment can be considered personal harm (LaDuke, 2005). In this way

personal health and psychological well-being are closely tied with the health and well-

being of the ecosystem. In contrast to those long-held beliefs of Native cultures,

2

contemporary Western culture is now just beginning to examine the link between nature

and psychological health. This is evident in treatises defining the burgeoning field of

ecopsychology (Roszak, Gomes, & Kanner, 1995) and its subfield, ecotherapy (Buzzell

& Chalquist, 2009). These compilations emphasize the important role of the human

relationship with the natural world for promoting and maintaining psychological health.

Indeed, recent research has begun to examine this human-nature connection.

Several measures have recently been created which attempt to quantify the concept of

connectedness to nature (Mayer & Frantz, 2004; Nisbet, Zelenski, & Murphy, 2009;

Schultz, 2002). For the purpose of this study, connectedness to nature can be defined as

the extent to which an individual’s view of nature is incorporated into their perception of

their own sense of self (Schultz, 2002). This broad definition includes physical, cognitive,

and emotional elements of that relationship. Nature in this sense can be defined as spaces

big or small consisting predominantly of flora and fauna and having little or no human

constructions (Schultz, 2000). Now that the concept of connectedness to nature has now

been defined and rendered quantifiable, emerging research has examined the relationship

between this variable and other important indicators of well-being such as psychological

health and quality of life (QOL).

Since research indicates that 46.4% of all Americans will suffer from a mental

health (MH) disorder at some point in their lives (Kessler et al., 2005), it is crucial to gain

more knowledge about the potential connections between MH and other personal

characteristics like one’s relationship with the natural world. If people are motivated to

increase their sense of connectedness to the natural world for personal reasons such as

3

improvements in their own health and well-being, then they may be more motivated to

seek out a more personal affiliation with the natural world. But, to date, no research has

examined the links between sentiments of connectedness to the natural world and

measures of physical or psychological health. However, emerging research has linked

experiences in the natural world with health and well-being. Experiences in nature have

been associated with significant personal gains such as an increase in positive affect

(Burns, 2008), decreased substance use (Frumkin, 2001), and lower rates of symptoms of

mental distress (Chalquist, 2009).

This new and interesting research suggests that it may be possible that one’s

sentiments of connectedness to nature (CTN) are also related to wellness. In order to

explore this, the current research will frame CTN around the broad concept of QOL as

well as aspects of MH. To date no one has directly examined the link between beliefs and

perceptions of a personal connection to nature and a broad measurement of QOL. Nor has

a comprehensive measure of MH been applied to this issue either. The following review

of the literature will critique and synthesize the previous research centered on the concept

of connectedness to nature and its relationship to health and QOL. In addition, this review

will examine what specific aspects of QOL and MH are most related to the human

connection with nature, and how they are related.

4

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

The Literature Review Procedure

Objectives

To understand of the current state of research with regards to connectedness to

nature, health, and well-being, this chapter has three objectives: (a) to describe the current

state of research regarding exposure and connectedness to nature and their relationships

to health and QOL; (b) to discuss the issues, strengths, and weaknesses in previous

research regarding the above topics; and (c) to draw conclusions based on this

information from which the research questions and strategies for this study were

formulated.

Keywords

A preliminary search of the PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, and Utah State

University library databases was conducted to identify all studies published prior to

August, 2011, that reported either: (a) measures of connectedness to nature or (b) the

effects on health and wellbeing of time spent in the natural world. A variety of search

terms and search term combinations were used including: CONNECTEDNESS,

CONNECT* TO NATURE, CONNECT* TO ENVIRONMENT, and NATURE AND

HEALTH. Additional articles were found through the reference sections of articles

identified through the database searches and from review articles on the health effects of

time spent in nature (Chalquist, 2009; Frumkin, 2001).

5

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included in this literature review if they met one of the following

criteria: (a) they contained a measure quantifying a sentiment of connection to the natural

world or (b) they documented the relationship between time spent in nature and physical

and/or MH. Studies were excluded if either: (a) no measure of connectedness to nature

was mentioned or (b) the study did not document the effects of health and well-being for

an intervention in the natural world.

Philosophical and Theoretical Underpinnings of

Connectedness to Nature

Overview

The goal of this section is to summarize the theory which could be used to explain

the importance and significance of the human connection to nature. In an attempt to find

contemporary theory which explains the affiliation between humans and the natural

world, works from diverse fields such as biology, philosophy, and psychology were

examined.

The Biophilia Hypothesis

It is evident that many people value nature highly and are willing to spend

significant amounts of time and money in order to interact with it through behaviors such

as paying a premium for a good view, devoting time to a garden, or hiking or driving

great distances to reach a desired natural setting (Clayton, 2003). The biophilia

hypothesis (Kellert & Wilson, 1993; Wilson, 1984) posits that there is an innate

6

emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms. This hypothesis suggests

that humans have grown to appreciate and protect other forms of life. Furthermore, the

demonstration of respect for all forms of life on this planet may assure our continued

survival as a species as the interconnected nature of life on this planet requires the

maintenance of a harmonious equilibrium between all forms of life.

This human need to affiliate with other living creatures extends far beyond the

mere exploitation of nature’s material resources to include the influence of nature on our

emotional, cognitive, aesthetic, and even spiritual development (Kellert, 1993). Thus, our

inherent Biophilia pervasively influences our thoughts and feelings. Sentiments of

affiliation vary on a personal level and some of that variation may be accounted for by

factors such as one’s level of exposure to nature. Still, it is hypothesized that all human

beings possess some degree of biophilia (Kellert & Wilson, 1993; Wilson, 1984). And,

by tapping into this trait through empirical investigation, it is possible to gain a greater

understanding of the reasons behind humans’ inherent connection to the natural world.

Deep Ecology

Viewing ourselves as a part of nature and understanding this human connection to

nature has also been explored in the field of deep ecology (Roszak et al., 1995). Deep

Ecology approaches the issue from a mainly philosophical and theoretical perspective. It

emphasizes the development of theory exploring the interconnectedness of all life forms

and the inherent value of all living creatures. However, perhaps due to the inability to

operationalize its terms and assess them in an empirical manner, deep ecology lacks

empirical support in the literature. Nevertheless, its theoretical propositions, such as the

7

connectedness of all living creatures and the inherent value of all living beings for

nonutilitarian reasons, has strongly influenced both the environmental movement and

contemporary theories of human connectedness to the natural world. These in turn have

led to more direct, empirical applications of this theory which examine the human

relationship with nature through the field of ecopsychology.

Ecopsychology

Ecopsychology concerns itself with more applied and practical aspects of

humans’ connectedness to nature. Through research and practice, the field of

ecopsychology seeks to explore more specific details regarding the human-nature

relationship. It places psychological research and the study of wellness in the context of

our current ecological systems. This includes experimental research published in peer-

reviewed journals such as Ecopsychology. For example, a recent issue of this journal

covered such diverse areas as outcome data for youth offenders who participate in a

wilderness adventure program (Russell, 2010) and the efficacy of applying different

social psychological principles to improve conservation behaviors (Meineri, Martin, &

Grandjean, 2010). In addition, the ecopsychology movement also targets the general

public through the publication of mass-market monographs such as those by Richard

Louv (Last Child in the Woods and The Nature Principle) and Bill McKibben (The End

of Nature and Deep Economy). Ecopsychology has also gained a foothold in the fields of

psychotherapy and counseling. In ecotherapy (Buzzell & Chalquist, 2009), the authors

explored how nature can be applied to a therapeutic context in diverse areas such as

equine therapy, couples work, and work with trauma.

8

Ecopsychological theory emphasizes the importance of expanding our sense of

self to include other living beings and the natural environment as a whole in addition to

empathizing with other forms of life. This concept of an ecological self as a nature-

inclusive identity is synonymous with a belief in the human connection to nature.

Including nature in one’s self-identity implies a perception of belonging to nature and

relating with it intimately. Although there has been a lack of empirical research regarding

the specific concept of ecological self, numerous researchers have attempted to quantify

the human-nature relationship in other terms with a variety of scales and measures.

Summary of the Theoretical Underpinnings

of Connectedness to Nature

Based on the above findings, there is an emerging literature base which informs

the theoretical understanding of CTN. Through the work of biologists, philosophers and

psychologists, the significance and importance of the human-nature connection has been

suggested. A relationship with the natural world is hypothesized to directly affect one’s

physical, mental, and overall wellness through the benefits gained by increased exposure

to nature and positive experiences in the natural world. Sentiments of connectedness to

the natural world may also be interpreted as a representation of the intention to be

integrated more fully with the other living beings on this planet and in that regard may be

related to QOL and wellness. Thus, the goal of the current project is to empirically

investigate how sentiments of connectedness to the natural world are related to wellbeing

and to gain a better understanding of the significance of the human-nature connection

through empirical exploration.

9

Measures Quantifying the Human-Nature Relationship

Overview

A review of the measures used to examine the human-nature relationship provides

an overview of how the above theoretical underpinnings can be placed in an applied,

empirical context. The goal of this section is to document previously published measures

purporting to describe the human-nature relationship and then engage in a critical

analysis of their strengths and weaknesses. The objective of this section is to determine

which measures, if any, could be deemed appropriate for the current study involving the

construct of CTN.

The New Ecological Paradigm

The concept of the human connection to the natural world described by the

biophilia hypothesis and in the ecopsychology movement has been studied empirically

using measures that quantify and categorize the human relationship with the natural

environment. The first researchers in this area concerned themselves with developing a

paper and pencil survey to quantify how one can measure sentiments and attitudes

towards nature and the environment. The result of this inquiry was the development of

the new environmental paradigm, the first measure designed to tap into personal attitudes

and beliefs about nature (Dunlap & VanLiere, 1978). It was later updated to become the

new ecological paradigm (NEP; Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig, & Jones, 2000).

The 15 item NEP is a measurement of people’s ecological worldviews and

environmental concern. It measures the degree to which a person views humans as an

10

integral part of the natural environment instead of being seen as separate from nature. It

also taps basic, essential beliefs about the nature of the earth and humanity’s relationship

with it. Representative items include “plants and animals have as much of a right to exist

as humans,” “the balance of nature is very delicate and easy to upset,” and “humans have

the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs.” Overall, the measure

elicits cognitive beliefs about people’s relationship with the natural world. However, the

measure lacks items which go beyond cognitions to include a sense of emotional or

physical affiliation with the natural world. The measure also lacks items which directly

tap into the concept of CTN elucidated in the theoretical literature of biophilia or

ecopsychology. Thus, while its cognitively based statements certainly tap into people’s

beliefs about the human relationship with nature, the measure fails to include physical,

emotional, or behaviorally-based manifestations of connectedness to nature relevant to

this study.

Environmental Value Orientations Scale

Similar to the highly cognitive NEP, a different measure was created by Stern and

Dietz (1994) to examine the origins of people’s environmental concern: the

Environmental Value Orientations Scale. Using factor analytic techniques they

demonstrated that environmental concerns are related to three different value

orientations: egoistic, social-altruistic, and biospheric values. Egoistic values describe

attention to environmental issues that affect people personally (“I am concerned about

environmental problems because of the consequences for: me, my lifestyle, my health,

my future”). Social-altruistic values describe environmental action from a place of moral

11

obligation and attending to environmental issues that have consequences to other human

beings (“I am concerned about environmental problems because of the consequences for:

people in my community, all people, children, future generations”). Biospheric values

describe judging environmental issues on the basis of the cost and benefits to nature and

the biosphere as a whole, thus giving the environment itself moral consideration (“I am

concerned about environmental problems because of the consequences for: plants, marine

life, birds, animals”). These value domains are all measured by separate scales which are

independently calculated.

This measure elicits the reasons why people may be concerned about the

environment as opposed to simply documenting the extent of their sentiments of concern.

In addition, this measure is worded within the context of “concern about environmental

problems.” This is understood to activate both the cognitive and emotional facets of

environmental concern. However, this scale lacks components which would make it an

appropriate measure of connectedness to nature. Concern for nature is different from

connectedness to nature; one can feel concerned about another being or system without

expressing strong sentiments of connectedness to that being or system. While this scale is

unique in its disambiguation of the reasons why people may be concerned about the

environment as well as its emotion-oriented language, it is not an appropriate measure for

the concept of connectedness to nature in this study.

Environmental Attitudes Scale

Similarly, Thompson and Barton (1994) formulated two distinct attitudes toward

the environment in their Environmental Attitudes Scale. In their measure, one subscale

12

tracks ecocentrism—valuing nature for its own sake and protecting it because of its

intrinsic value. The other subscale, Anthropocentrism, is defined by the belief that nature

should be valued only for the material and physical benefits that it can provide for

humans. Those with strong ecocentric values were more likely to endorse conservation

behaviors and belong in environmental organizations. Those with strong Anthropocentric

values were more likely to endorse environmental apathy and less likely to engage in pro-

environmental behaviors. This measure is inappropriate for use in the current because it

examines attitudes and values towards the natural world which are distinct from the

concept of connectedness to nature and do not tap an emotional, cognitive, or physical

strength of affiliation with the natural world.

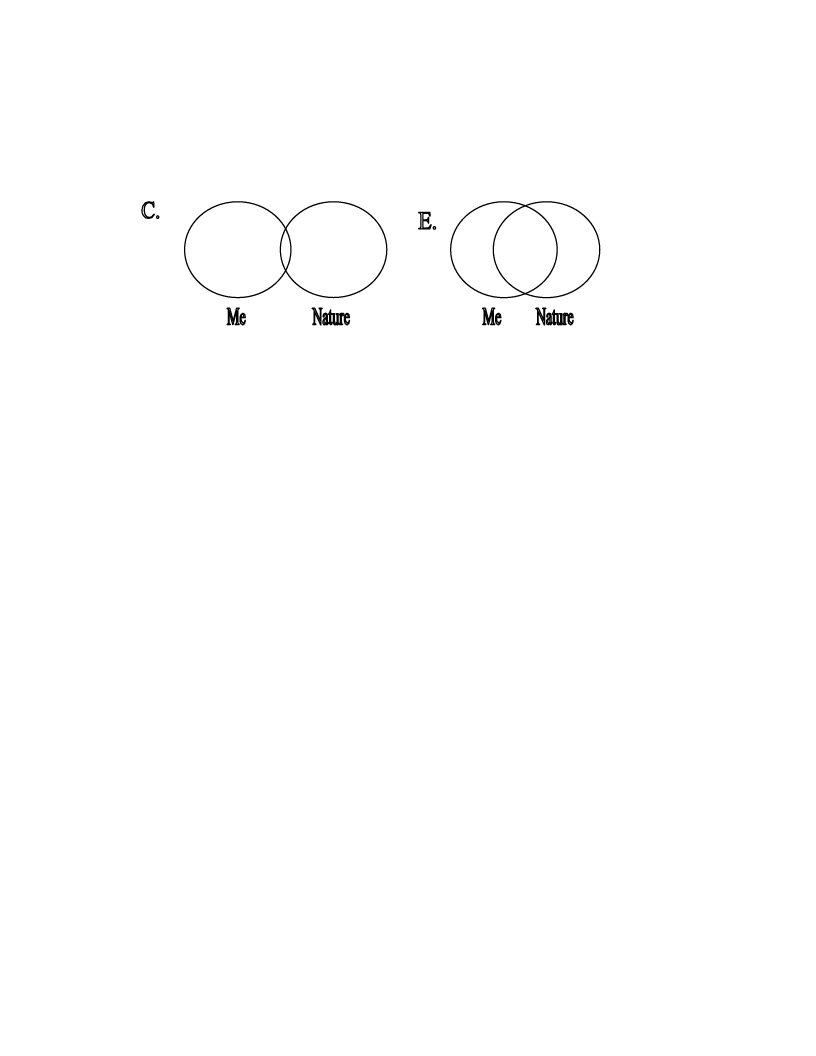

Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale

Instead of framing the human relationship with nature around environmental

concerns, other researchers have focused on specific qualities of peoples’ connection to

the natural world and related those to pro-environmental behaviors. The concept of

connectedness to nature was first introduced by Schultz, who designed a measure to

examine the extent that people viewed themselves as part of the natural environment

(Schultz, 2000, 2001). The Inclusion of Nature in Self scale taps beliefs regarding one’s

feelings of connection to the natural world through a visual metaphor of overlapping

circles (see Figure 1). More overlap between the two circles of “me” and “nature”

indicates a stronger connection between those two domains. This method of measuring

connectedness to nature confers many advantages. Its visual, nonlinguistic nature allows

the subject to express their choice in a context free from the construct of language. This

13

Choose the one pair of circles that best represents your sense of connection to the natural world and circle

that set:

Figure 1. The Inclusion of Nature in Self scale.

could potentially create a less biased and more intuitive measure. In addition, its

simplicity and facility of administration make it a very accessible measure to administer.

However, it also suffers from a few disadvantages. It offers no details or reasons as to

why one may feel that sense of connection. While potentially useful as a single-item

measure, it is unclear whether this is a true measure of connectedness to nature or if it

could merely be tapping sentiments of affiliation or preference. Furthermore, as a single-

item measure, it is impossible to judge internal consistency or reliability. Therefore this

measure is not appropriate for use in the current study.

Environmental Identity Scale

Other researchers have been more concerned with issues of identity. Clayton

(2003) established a different approach to the topic of the human relationship with the

natural environment. She described Environmental Identity through the establishment of

a personal sense of connection to the natural environment which is based on history,

similarity, and feelings of personal connection (Clayton, 2003). The Environmental

14

Identity Scale (EIS) combines past and present interactions with nature, self-

identification with nature, environmental ideology, and emotional response to nature to

create a measure of environmental identity. Environmental identity has been shown to

positively correlate with pro-environmental behavior. Thus, someone with a stronger

environmental identity would be more likely to endorse efforts of resource conservation

and environmental protection. Likewise, those with a weaker environmental identity

would be less likely to favor the protection of the environment or the conservation of

natural resources. Although the EIS does tap into certain aspects of connectedness to

nature such as one’s sense of overlap between personal identity and environmental

identity, it also draws upon past experiences with nature and political values. Therefore,

the EIS broadens the concept of connectedness to the natural world desired for this study

by bringing in political beliefs and past experiences in the natural world, and this does not

fit the concept of connectedness to nature desired for measurement in this study.

Connectedness to Nature Scale

Another measure designed to quantify the concept of connectedness to nature is

the Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS; Mayer & Frantz, 2004). Based on the theory

and writings of Aldo Leopold (Leopold, 1949), the 14-item CNS was designed to

measure “an individual’s affective, experiential connection to nature” (Mayer & Frantz,

2004). Sample items include, “I often feel a sense of oneness with the natural world

around me,” “I think of the natural world as a community to which I belong,” and “I

often feel a kinship with animals and plants” (Mayer & Frantz, 2004). The CNS is an

effective measure of environmental attitudes, a multi-item scale, and a good predictor of

15

environmental behavior. However, the measure also has a few drawbacks. First, there is

concern that the CNS does not measure an emotional connectedness to nature as the

authors purport, and instead merely taps into cognitive beliefs (Perrin & Benassi, 2009).

Also, Perrin and Benassi argued that it is only the scale’s self-referential nature and

positive tone that account for the differences with the NEP. Furthermore, the measure

lacks a physical component of connectedness to nature, which is deemed to be crucial in

the construct of connectedness to the natural world (Nisbet et al., 2009). Because of these

concerns and the limited definition of “connectedness to nature” proposed by the authors,

this measure will not be used as the primary operational definition of CTN in this study.

Nature Relatedness Scale

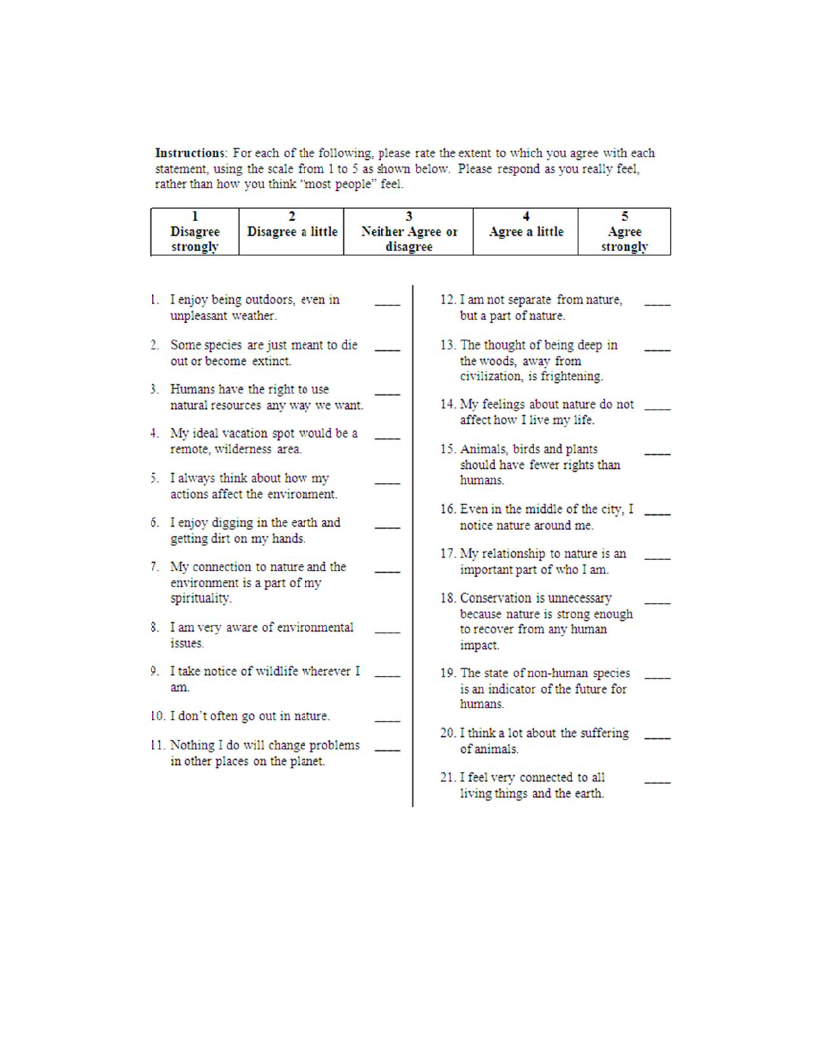

This study will use a more recent scale to measure the concept of connectedness

to nature—the Nature Relatedness (NR) scale (Nisbet et al., 2009). The NR was designed

to assess the affective, cognitive, and physical relationships between humans and the

natural world. The measure also taps into a sense of appreciation and understanding of

the interconnectedness of life on this planet. In addition to functioning as a single,

cohesive measure of connectedness, the NR loads onto 3 distinct factors: NR Self, NR

Experience, and NR Perspective. See Chapter III for statistics regarding the reliability of

this scale, and Table 1 (shown later in Chapter III) for definitions of each subscale and

sample items that load onto each individual scale.

Summary and Conclusions

After a review of the measures developed to examine individuals’ relationships

16

with the natural world, the NR (Nisbet et al., 2009) best defines the concept of CTN for

purposes of this study. Its multi-scale format allows direct examination of three

empirically validated components of connectedness to nature (Schultz, 2002): a personal,

self-concept-related aspect, a view of our species’ place in the broader ecosystem, and the

value of physical experiences in the natural world. This is especially useful when wishing

to compare the NR to other measures of health and wellness, as desired in the current

study. The NR is sensitive to change after experiences in nature, and the measure was

found to be associated with pro-environmental behaviors.

Since the NR has been found to be associated with a few measures of well-being,

it is possible that it may be associated with related constructs as well. The following

section will examine QOL based on previous literature, provide theoretical background

supporting this concept, and describe various measures used to quantify the construct of

QOL with the ultimate goal of choosing a measure which best fits the construct of QOL

and is most practical for use in the current study.

Quality of Life

Overview of the Construct

“Quality of Life” is a construct created to measure a level of overall well-being in

individuals or populations (World Health Organization [WHO], 1997). This broad, far-

reaching concept encompasses numerous domains such as one’s environment,

community, social and family relations, physical health, MH, and leisure activities. Its

exact definition varied from one author to the next. One Danish team (Ventegodt et al.,

17

2005) described QOL with regards to the relationship between one’s current life

experiences, personal history, and early life biological factors. In this context, QOL

contains numerous subjective factors (e.g. meaning in life, life satisfaction, and

happiness) and objective factors (e.g. income, status, and work). Health and ability play a

large role in determining one’s QOL as well. The authors conclude that for many QOL is

determined not solely by life events but also by the way that one views and processes

those events. This implies a large subjective component to QOL and suggests that QOL is

also related to one’s ability to be a part of the present reality.

Other authors view QOL as a complement to measures of functional status and

health (WHOQOL Group, 1998). According to the WHO, an ideal measure of QOL

should include physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. These authors

assert that QOL is a multidimensional construct which loses a great deal of richness and

validity when examined from a mono-dimensional perspective.

Others assert that QOL should be viewed by examining measurable, objective

characteristics such as functional status, health, and well-being (Garratt, Ruta, Abdalla,

Buckingham, & Russell, 1993). This has led to the creation of many health-related

measures of QOL. These measures examine QOL through one’s ability to interact with

the world and function in basic tasks of living on a day to day basis. These measures also

are frequently used to determine how illnesses affect one’s ability to function.

Since an investigation into the construct of QOL is relevant and necessary, one

way to further explicate definitions of QOL is to examine the measures themselves. For

this study, numerous measures of QOL were evaluated with the goal of choosing a

18

measure that adequately captures the multi-faceted nature of well-being in an appropriate,

culturally sensitive manner for a representative sample of healthy, college-aged adults.

The Short Form- 36

First, the category of health-related QOL measures was evaluated to see if one of

those measures adequately expressed the above-stated criterion. The Short Form-36 (SF-

36) was examined due to its ubiquity (Turner-Bowker, Bartley, & Ware, 2002),

popularity, and balance between brevity and comprehensiveness (Ware & Sherbourne,

1992). The SF-36 consists of 36 questions that break down into eight subscales: physical

functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, MH, and role

limitations due to emotional problems, social functioning, vitality, and general health

perceptions.

This measure was not chosen for inclusion in the current study because it

provided too limiting and strict of a definition of QOL by focusing mainly on one’s

capacity to accomplish tasks and function autonomously. While aspects of social

functioning and overall well-being are included, their weight with regards to the entire

measure is light. While the SF-36 would be quite appropriate in a medical setting, for a

healthy, college-age sample there remains the possibility of a limited range of scores and

a larger than necessary emphasis on physical health to the neglect of other valuable

aspects of well-being.

The Quality of Life Questionnaire

The Quality of Life Questionnaire (Evans & Cope, 1989) was subsequently

19

examined as a possible measure due to its more broad and inclusive definition of QOL

beyond a health related context. In this measure, 192 true/false self-report items were

designed to gauge an individual’s behavior in the context of their environment. It

includes five major domains: general well-being, interpersonal relations, organizational

activity, occupational activity, and leisure and recreational activity.

This measure succeeds in creating a broad, multifaceted definition of QOL. It

extends beyond merely health related aspects of QOL to include other domains such as

work, leisure, and civic responsibilities. However, this operational definition of QOL is

not ideal for use in the current study. It appears to be targeted strictly towards working

adults of North American culture. It asserts that certain domains like occupation, voting,

and charity work are relevant factors for one’s QOL. While this may be the case for

some, for the college students and young adults (many of whom do not work and are not

civically active) who are the subject of the current study, this measure may give an

inaccurate impression of QOL by placing value on certain domains which are not as

relevant to this cohort. In addition, its definition of QOL appears limited to mainstream

North American culture, limiting its generalizability.

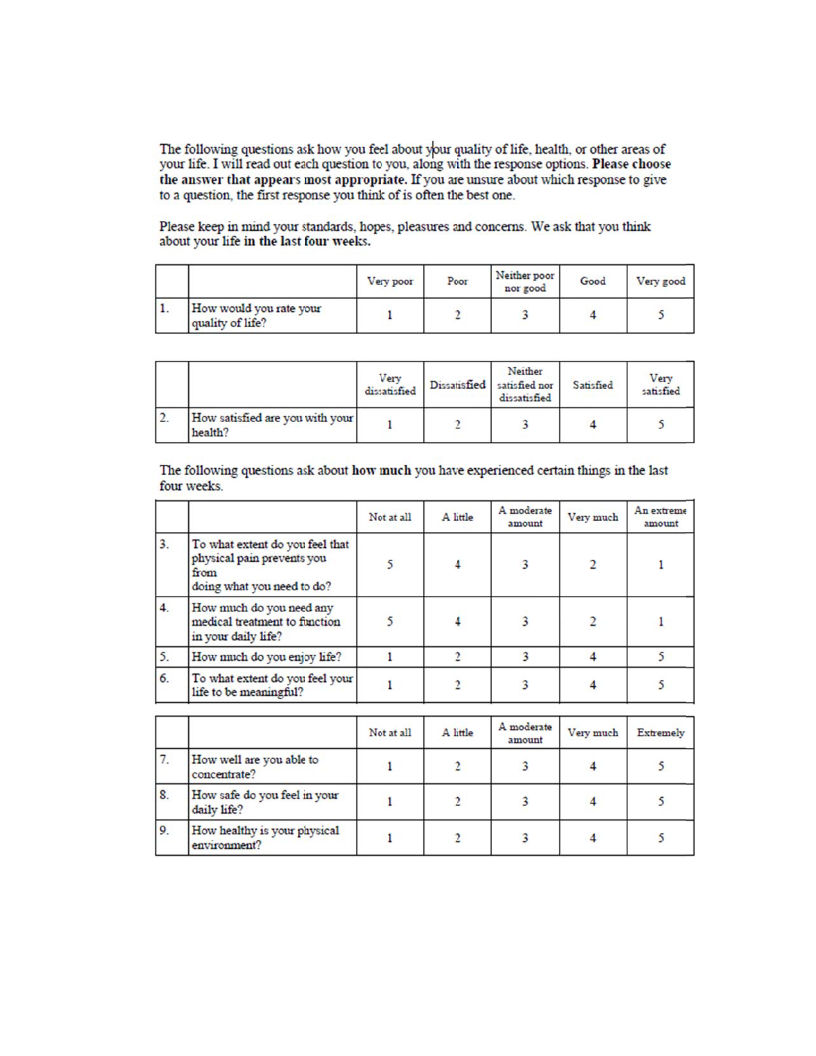

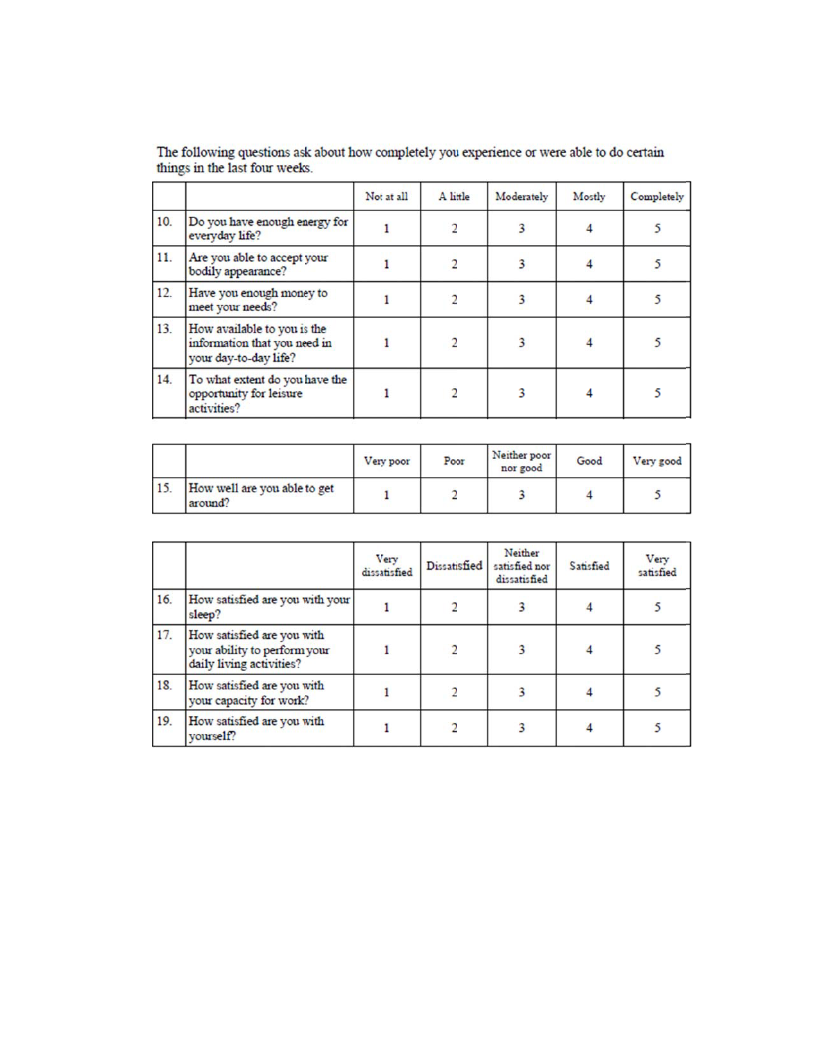

The WHOQOL-BREF

The WHO’s Quality of Life-Brief measure (WHOQOL-BREF) is a promising

measure of QOL for the current study (WHO, 2011). This 26-item measure was designed

to allow the participant to determine the importance of certain activities and values in the

determination of their own QOL, and so the measure claims to be free of cultural bias and

thus applicable worldwide (WHO, 1993). The WHO defined QOL as “individuals'

20

perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in

which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”

(WHO, 1997). Consequently, this measure includes physical, mental, social,

environmental, and personal belief components of well-being. By focusing on

individuals’ perceptions of their own well-being, the measure strives to assess overall

functioning in the context of health and QOL (WHO, 1993). For these reasons, the

WHOQOL-BREF was chosen as the best measure of QOL for the purposes of this study.

Quality of Life and Connectedness to Nature

The following section will examine several specific aspects of QOL and how they

may be related to the construct of CTN. The following review will cover the

environmental, social, and physical aspects of QOL. The well-established relationship

between MH, an important aspect of QOL included in most measures, and CTN will be

reviewed in a forthcoming section.

Environment and Connectedness to Nature

Many experts consider the physical and built environment to compose a

significant aspect of QOL (Evans & Cope, 1989; Turner-Bowker et al., 2002; WHO,

1997). The physical characteristics of where one lives and specific aspects of their

community such as safety and ease of transportation are aspects of QOL frequently cited

in measures (WHO, 1997). These elements of one’s built and natural environment could

be related to and influence one’s sentiments of CTN.

Most of the literature which relates sentiments of CTN to the physical

21

environment examines the differences between rural and urban populations. Rural

inhabitants report stronger sentiments of connectedness to the natural world than urban

residents (Klassen, 2010; Muller, Kals, & Pansa, 2009). However, these studies measured

connectedness to nature as a single item self-report question, making the measure

susceptible to problems of internal validity as well as differences in interpretation

between participants. Also, those studies were also limited by the lack of socioeconomic

diversity in their participants. Another study of rural inhabitants also demonstrated that

they reported stronger sentiments of connection with the natural world than urban

residents and also reported higher scores on indices of well-being than those from urban

areas (Hinds & Sparks, 2009). However, that study similarly suffered from a small

sample size and a geographically and ethnically narrow population, reducing its external

validity.

This study attempted to expand the connection between an environmental aspect

of QOL and CTN by examining how other factors of the built environment besides

merely rural living, such as safety or ease of transportation, may be related to CTN.

Social Relationships and Connectedness

to Nature

Research connecting social relationships, an important element of QOL, and CTN

is currently quite scant. One study (Marcus, Omoto, & Winter, 2011) cited the

importance of a sentiment of community and strong interpersonal relationships in the

development of the values of environmentalism and participation in environmental

issues. The current study intends to collect exploratory data to further examine the

22

connection between social relationships and sentiments regarding CTN.

Physical Health and Connectedness

to Nature

Numerous studies have linked exposure to nature with increased physical health,

an important aspect of QOL. One study examined a representative sample of US adults

and found higher rates of physical health and well-being in those who have more direct

contact with the natural world (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989). Other lines of inquiry have also

linked exposure to nature with positive benefits for physical health in samples of both

healthy US adults and those with physical and mental illness (Chalquist, 2009; Frumkin,

2001). Interestingly, sometimes simply having a view of nature has an effect on health.

One study found that prison inmates with views of the outdoors area beyond the prison

are sick less than those with views of an interior courtyard (Moore, 1981), while another

found that patients with views of nature from hospitals rooms recover faster than those

with views of a wall (Ulrich, 1984). These studies are notable in their significant efforts

to decrease confounding variables and examine only the difference in view. While this

health effect could be attributed to qualities of the view besides the mere presence or

absence of natural stimuli, these results still deserve attention.

Contact with animals, such as pets, has also been shown to decrease the amount of

health problems that their owners may experience. In one prospective study, a community

sample of adults was found to experience fewer illness and minor injuries than a

comparison group of nonpet owners over a 10-month period (Serpell, 1991). Pet

ownership has also been found to be associated with higher levels of physical health

23

(Mullersdorf, Granstrom, Sahlqvist, & Tillgren, 2010). Unfortunately, it was not

determined whether the health-affirming aspects of pet ownership effects were due

simply to the presence of a pet in the home or factors associated with pet ownership such

as time spent outside or an increase in physical activity or exercise. Thus, one can only

speculate as to the mechanism at work in decreasing health problems among pet owners.

In addition, hospital administrators have long understood that the presence of plants and

gardens increases rates of healing among their patients, and participation in wilderness

programs often results in improvements in physical health (Frumkin, 2001). Again, the

literature fails to explain how these situations increase healing. It may not be the presence

of nature or natural features themselves, but rather elements associated with nature

instead. Improvements in health could be accounted for by the increased sensory

stimulation and activity levels that gardens provide, and the health-promoting aspect of

wilderness programs could be due solely to increased exercise or a decrease in

environmental contaminants. Still, these findings merit further investigation.

It should likewise be noted that the exact mechanisms of how time spent in nature

may mediate physical health and wellness are unknown. Exposure to nature is often

associated with physical exercise, and it is possible that the effects of increased physical

activity which happen to take place outdoors account for health improvements.

Alternatively, the effect could even be biological: exposure to a type of bacteria, M.

vaccae, which is only found outdoors in soil, was shown to produce increases in immune

system production and boost levels of serotonin (Lowry et al., 2007). More research is

needed to determine the mechanism of action which connects exposure to nature and

24

physical health.

While physical health is merely one component of QOL, an in-depth examination

of the relationship between physical health and exposure to nature reveals the diversity of

ways in which exposure to the natural world could be related to one’s QOL. In addition,

these studies highlight avenues rich for future research which could serve to better

explain the mediating factors between exposure to the natural world and personal health.

Mental Health and Connectedness to Nature

Overview

The following section will outline the connections between nature and one’s MH.

It will begin with an examination of the research connecting experiences in the natural

world with changes in MH. After this connection has been established, a review of the

small but significant literature supporting the relationship between connectedness to

nature and MH will be conducted.

Exposure to Nature and Mental Health

An established base of research catalogs the positive effects of exposure to nature

for one’s MH. Nature may have a rejuvenating effect: spending time in nature could

serve to increase tolerance of stressful situations, improves concentration, and increase

productivity (Nisbet & Zelenski, 2011; Nisbet, Zelenski, & Murphy, 2010). Another

study examining university students in the United States using cross-sectional survey data

reported that those who self-report more contact with the natural world as measured by

time spent in a natural environment report higher levels of effective functioning and

25

personal development, peacefulness as measured by the Positive and Negative Affect

Scale, and lower levels of stress as measured by the Perceived Stress Scale (Herzog &

Strevey, 2008).

A number of studies have also examined the MH and well-being of inhabitants of

rural communities. These populations, which may typically have a higher degree of

contact with nature in their daily lives than those from urban areas, may be considered a

proxy for those with more exposure to nature. After controlling for a number of factors

such as SES, employment, and household income, one investigation demonstrated that

rural inhabitants reported lower rates of symptoms of depression and anxiety on the

General Health Questionnaire than participants living in urban areas (Weich, Twigg, &

Lewis, 2006). Yet, this difference, while statistically significant, demonstrated little

practical significance (1/2 point on the General Health Questionnaire).

To date, the exact mechanisms behind the connection between rural life, CTN,

and well-being remains unclear. While some hypothesize that rural inhabitants possess a

stronger sense of place (i.e. they feel more connected and comfortable with the land on

which they live) than urban inhabitants that contributes to increased well-being (Weich et

al., 2006), other authors purport that rural living increases one’s exposure to the natural

world, and nature’s subsequent restorative effects cause the increases in well-being

(Hinds & Sparks, 2009). Or, it could be that factors inherent to rural life such as less

crime, pollution, and crowding could attribute to improvements in well-being.

Unfortunately, no peer-reviewed study has pursued this possibility. Regardless, since

some models actively attempting to explain mediating factors only account for half of the

26

variance in the rural inhabitance-well-being connection (Hinds & Sparks, 2009), there is

still clearly a great deal more research necessary before anything more than tentative

conclusions can be reached regarding the connection between rural life, connectedness to

nature, and well-being.

The connection between exposure to nature and MH is also supported by the

literature as evidenced by two thorough literature reviews (Chalquist, 2009; Frumkin,

2001). People connected with nature through the ownership of pets such as dogs have

shown significant benefits for MH including stress reduction (Siegel, 1990) and decreases

in depression (Siegel, Angulo, Detels, Wesch, & Mullen, 1999). Unfortunately, one can

only speculate as to the mechanism of action in these studies. It may be due to the fact

that dogs, as members of the animal kingdom, increase one’s feelings of connectedness to

nature in general, which then leads to improvements in MH. Or, as mentioned above, it

could simply be that pet ownership necessitates healthy changes in lifestyle such as more

time spent outdoors doing physical activity. Or, the added companionship of pets may be

providing a boost to mood.

In addition, those who connect with the natural world through gardening and the

care of plants benefit from numerous positive MH outcomes according to research in the

field of horticultural therapy (Jarrott & Gigliotti, 2010; Rice, Remy, Whittlesey, Simson,

& Straus, 1998). Again, it is not entirely understood why this is the case. It could have

something to do with the physical act of gardening or perhaps some of its associated

features such as caring for other living creatures, interacting with nature, and being

outdoors.

27

Furthermore, ecotherapists in independent practice have reported the mental and

physical benefits of contact with nature for their clients (Burns, 2008). For example, one

intervention for couples in conflict involved creating shared experiences in natural

settings in order to strengthen their relationship. In another situation, reconnecting with

special natural areas that were important to one as a child helped to solidify values and

improve sentiments of well-being. While this evidence from psychotherapists is

anecdotal and requires systematic study to ascertain more definite conclusions, it does

indicate an area ripe for future research.

There have even been significant findings detailing nature’s restorative effect on

emotions. A “natural” stimulus, ocean waves, was specifically selected by the authors of

one study to elicit contentment. It was found that the ocean wave sound significantly

reduced the cardiovascular stress and sympathetic nervous system arousal elicited by a

fearful stimulus (Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998; Fredrickson, Mancuso, Branigan, &

Tugade, 2000). However, it may not be ocean waves’ nature-related quality that induces

the effects of contentment. It could be the repetitive, monotonous nature of the sound that

classifies it as contentment-inducing. This study only demonstrates that the stimulus

chosen by the authors to be prototypically contentment-inducing happens to be nature

related, and that the calming effect was supported by the results. Multiple additional

studies have also demonstrated the stress-reducing (Laumann, Garling, & Stormark,

2001; Rader, 2009), restorative effects (Herzog, Black, Fountaine, & Knotts, 1997;

Herzog, Maguire, & Nebel, 2003), well-being enhancement (Kaplan, 2001), and mood-

improving aspects (Rader, 2009) of exposure to nature and nature-related stimuli. Again,

28

with all of these studies, it is not possible to determine what specific aspects of these

natural stimuli account for increases in well-being. However, the preponderance of

results connecting natural stimuli with improvements in health and well-being points to

the necessity of further investigation of how this occurs. This study attempted to build on

these findings to examine whether this relationship is mediated by sentiments of

connectedness to the natural world.

Greenway (1995) demonstrated that participants in a nature-based course were

successful at breaking old unhealthy habits such as the consumption of alcohol and

tobacco. However, a lack of control variables limits the extent of determining nature’s

role in the reduction of substance use. Likewise, adolescent participants in wilderness

therapy programs, which emphasize the therapeutic aspects of a wilderness setting

(Russell, 2003, 2005), have also shown a great deal of positive outcomes such as a

stronger desire to reduce maladaptive behavior, less substance abuse, and a better

awareness of one’s feelings (Russell & Phillips-Miller, 2002). Again, it is difficult to

determine the exact role that the natural setting and connectedness to nature play in the

process of reaching these positive outcomes.

In addition, a number of thinkers in the field of ecopsychology emphasize the

importance of a connection with the earth and its implications for MH (Bragg, 1996;

Conn, 1998; Feral, 1998). According to this perspective, a significant amount of mental

illness stems from a lack of connection with the natural world in today’s modern society.

By ignoring and failing to acknowledge our connection to the natural world we are

denying a fundamental part of our identity as human beings (Howard, 1997; Roszak et

29

al., 1995). It is argued that psychological issues such as depression and anxiety can be

related back to this sense of disconnect with our natural world and additional concern

over the health and well-being of our planet (Buzzell & Chalquist, 2009). Unfortunately,

these claims lie solely on theoretical grounds without empirical support. The current

explored these theoretical claims.

One commonality does exist among of all of the above findings: there can be only

speculation as to the mechanism of action connecting exposure to nature with increases in

well-being. These studies are valuable because they provide potential reasons why nature

is important for one’s personal well-being. However, none of them provide more than

corollary evidence connecting direct exposure to natural environments or nature-related

stimuli to gains in personal health and well-being. Thus, these findings should be viewed

as an indication to further investigate the connection between nature and health and not as

support for the health-affirming aspects of exposure to nature. Connectedness to nature

could be one of the mediators in the relationship between exposure to nature and health.

The following section will examine this possibility.

Connectedness to Nature and Mental Health

Recent research in experimental psychology has served to quantify fundamental

Ecopsychological principles by associating measures of connectedness to nature with

specific outcomes and implications for health and well-being (Mayer & Frantz, 2004;

Mayer, Frantz, Bruehlman-Senecal, & Dolliver, 2009; Nisbet et al., 2010). Research

applying the Connectedness to Nature Scale demonstrates a correlation between higher

ratings of connection to the natural world and greater life satisfaction (Mayer & Frantz,

30

2004). However, life satisfaction was only a single item likert-scale question. Thus, the

information that can be gleaned from this metric is certainly limited and requires a more

detailed examination. In another study sampling U.S. university students, time spent in

nature was also found to support reflection of life problems and was associated with

higher state levels of connectedness to the natural world (Mayer et al., 2009). After

taking a walk in a natural area, students reported that they were more effective in

resolving a minor life problem through contemplation than those who performed the

same procedure in a non-natural area (i.e., a parking lot). It appears that there is

something inherently restorative about time spent in nature. And, this restorative process

may be mediated through a greater feeling of connectedness to the natural world in that

moment.

Research with the Nature Relatedness (NR) scale has explored the relationship

between connectedness with the natural world and well-being (Nisbet et al., 2009).

Recent studies have revealed that NR correlates positively with many indicators of well-

being including positive affect, autonomy, personal growth, purpose in life, and vitality

(Nisbet et al., 2010). A more recent investigation using this scale has shown that an

increased positive affect can result from taking a walk in a natural area compared to

taking the same walk indoors. Furthermore, both positive affect and time in a natural area

contribute to higher levels of Nature Relatedness (Nisbet & Zelenski, 2011). It seems

from this finding that NR mediates the relationship between time spent in nature and

positive affect. However, further research is required to support the results of this single

study.

31

Summary and Conclusions

As evident above, research supports the relationship between experiences in the

natural world and positive MH outcomes. Additionally, a small but growing body of

work has found relationships between the novel concept of CTN and indicators of MH.

Further research should attempt to build on these initial findings regarding CTN in order

to better understand the importance of the human-nature connection.

Mental Health

Overview

Mental illness represents a significant problem in this country with 26.2% of all

adults receiving a DSM-IV diagnosis and $57.5 billion spent on MHcare during a one

year period (Kessler et al., 2005). Many factors have been found to influence one’s MH

status. Differences in age and sex are found in many mental illnesses such as major

depressive disorder (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000; Waraich, Goldner,

Somers, & Hsu, 2004) and panic disorder (Eaton, Kessler, Wittchen, & Magee, 1994;

Goodwin et al., 2005). Socioeconomic status (SES) may also influence MH in areas such

as eating disorders (Palma-Coca et al., 2011) and depression (Kosidou et al., 2011).

Ethnic differences have also been found in the prevalence of many mental disorders such

as substance use disorders (Bray, Adams, Getz, & Baer, 2001; Huang et al., 2006). Since

spirituality has also shown to be an important factor in the treatment of substance use

disorders (Franklin, Markarian, Frances, Miller, & Mack, 2005; Lyons, Deane, Caputi, &

Kelly, 2011), information regarding strength of spiritual beliefs is deemed important. In

32

addition, exercise has been found to play a role in the prevalence (Strohle, 2009) and

treatment of various mental disorders such as depression (Mota-Pereira et al., 2011) and

anxiety (Carek, Laibstain, & Care, 2011). Interestingly, many studies have found pet

ownership to be associated with lower levels of MH as well (Mullersdorf et al., 2010;

Parslow, Jorm, Christensen, Rodgers, & Jacomb, 2005).

Quality of Life and Mental Health

Research has firmly established the relationship between QOL and MH. A

thorough review of this body of literature is beyond the scope of the current study.

However, a brief mention of a few studies incorporating similar measures to the current

study merits attention. One study found moderate to strong positive correlations between

QOL as measured by the WHOQOL and MH as measured by the SCL-90 in a group of

Dutch psychiatric outpatients (Trompenaars, Masthoff, Heck, Hodiamont, & Vries,

2005). Another study found similar findings in a group of alcoholic males (Barros da

Silva Lima, Fleck, Pechansky, de Boni, & Sukop, 2005). Additionally, a third study also

found a strong positive relationship between MH and QOL in adults with mood disorders

(Trompenaars, Masthoff, Van Heck, Hodiamont, & De Vries, 2006). These findings are

understandable due to the fact that most measures of QOL, such as the WHOQOL,

include an assessment of MH as a fundamental aspect of QOL. Thus, this relationship

between QOL and MH will not be a focus of the current study due to the extensive body

of previous work in this area and the already well-established relationships.

33

Concluding Remarks

Previous psychological research has certainly demonstrated the feasibility of

developing a measure which accurately quantifies the sentiment of connectedness to

nature discussed through the biophilia hypothesis (Wilson, 1984) and writings of

ecopsychologists (Buzzell & Chalquist, 2009; Roszak et al., 1995). Numerous other

studies have also demonstrated the strong link between exposure to nature and measures

of physical and MH. In addition, researchers are now just beginning to move in the

direction of directly applying measures of connectedness to nature to the categories of

health and wellness. However, while recent research has touched upon some of the

potential benefits of possessing strong sentiments of connectedness to nature such as

increased positive affect and greater life satisfaction, no studies have examined the

explicit connection between sentiments of connectedness to nature and specific indicators

of health and QOL. Therefore, the following specific aims and research questions were

proposed.

Specific Aims and Research Questions

This study addressed four specific aims: (1) to explore the relationship between

CTN and demographic variables (age, class standing, major, GPA, sex, ethnicity, SES,

location of childhood home, strength of spiritual beliefs, pet ownership, amount of

exercise); (2) to explore the relationship between CTN and QOL, (3) to explore the

relationship between CTN and MH; and (4) to explore what other factors relate to CTN,

and to what extent.

34

This study addressed the following research questions related to Aim 1.

1. How were the responses for demographic variables and CTN (1 overall scale

and 3 subscales) distributed across the sample?

2. What were the relationships between CTN and the demographic variables

suggested by previous research?

This study addressed the following research questions related to Aim 2.

1. How were the responses for QOL (1 general rating and 4 subscales) distributed

across the sample?

2. What were the relationships between CTN and QOL scales?

This study addressed the following research questions related to Aim 3:

1. How were the responses for MH (1 overall scale and 9 subscales) distributed

across the sample?

2. What were the relationships between CTN and MH scales?

This study addressed the following research question related to Aim 4:

1. Which of the above variables (demographics, global QOL, and global MH)

most strongly predicted CTN, and to what extent?

The research questions may contribute meaningfully to the research base because

they help to clarify connections between holding sentiments of connectedness to the

natural world and indicators of personal well-being. If these hypotheses are supported, an

argument could be made to investigate possible causal relationships between variables.

This could lead to interventions designed to increase CTN, which in turn may contribute

to increases in MH and QOL, resulting in healthier and better functioning people.

35

CHAPTER III

METHODS

Setting and Sample

Data collection took place in Logan, UT, a small college town of approximately

48,000 people in the Cache Valley region of Northern Utah. Participants were recruited

via class presentations and an online recruitment system, Sona Systems (www.sona-

systems.com), from a pool of psychology students at Utah State University during the

spring semester of 2012. In the Sona System the students had the opportunity to

participate in this study by selecting it from a list of approved experiments conducted by

the university as one possible way to obtain course credit. Their decision to choose

participation in this experiment was based on only its title (“Connectedness to Nature and

Wellness”) and the time commitment required (approximately 30 minutes). In order to

promote a wider diversity of students, participants were also recruited from sections of

Introductory English. During their class time, students participated in the survey and

listened to the researcher give a lecture of the research process as part of a course