International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Article

Sociodemographic Determinants of Poles’ Attitudes towards

the Forest during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Anna Koprowicz 1 , Robert Korzeniewicz 2 , Wojciech Pusz 3 and Marlena Baranowska 2,*

1 Institute of Pedagogy, Pomeranian University in Słupsk, 76-200 Słupsk, Poland; anna.koprowicz@apsl.edu.pl

2 Department of Silviculture, Poznan University of Life Sciences, 60-637 Poznan´ , Poland;

robert.korzeniewicz@up.poznan.pl

3 Department of Plant Protection, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences,

50-375 Wrocław, Poland; wojciech.pusz@upwr.edu.pl

* Correspondence: marlenab@up.poznan.pl; Tel.: +48-618-487-612

Citation: Koprowicz, A.;

Korzeniewicz, R.; Pusz, W.;

Baranowska, M. Sociodemographic

Determinants of Poles’ Attitudes

towards the Forest during the

COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ.

Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537.

https://doi.org/10.3390/

ijerph19031537

Academic Editors: Pedro

Silva Moreira, Pedro Morgado, Pedro

R Almeida and Ary Gadelha

Received: 2 January 2022

Accepted: 27 January 2022

Published: 29 January 2022

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Copyright: © 2022 by the authors.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

Abstract: Attitudes towards forest ecosystems have been changing together with human needs, which

is amplified with society’s increasing need to spend recreation time in the forest. The phenomenon

has been particularly visible during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of this study was to determine

the attitude of Poles to forests during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research was based on (1) a

sociodemographic background questionnaire that consisted of questions about the independent

variables and (2) the LAS scale—an independently prepared tool for measuring attitudes towards the

forest. In the survey, 1025 people participated (673 women). The age of the subjects was between 19

and 68. The attitude towards the forest was analysed in three dimensions: Benefits, Involvement, and

Fears. The Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks were

used for statistical analysis. Women and people with primary education expressed the most fears

connected with going to the forest. Men and people living in the countryside and in small towns,

as well as respondents who were professionally active and performing work connected with forests

were the most involved in exploring the forest and working for its benefit. Concerning the forest,

concerned women, people from the highest age group, respondents with university education, and

white-collar workers notice the most benefits from recreational activities in the forest.

Keywords: coronavirus; forest therapy; LAS scale; COVID-19; society; forest function; urban and

suburban forests

1. Introduction

1.1. Forest and Health

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has acknowledged forest ecosystems as key for

the survival of the humankind and the life on Earth [1]. The perception of forest ecosystems

has been changing together with human needs [2,3]. It has been estimated that forests

fulfil over 100 functions that are perceived as benefits which humans can accrue. The

most popular benefits are economic, social, and protective [4,5]. The social benefit of the

forest, which is constantly gaining importance, is to create optimal conditions for human

health and recreation [5,6]. The modern person in an anthropogenic environment, who

is constantly pursuing free time to regenerate both the body and mind, is spending an

increasing amount of time in the forest [7,8].

The idea of spending time in a natural environment for its regenerative, restoring,

and healing properties has been known since the 16th c. In Europe, people suffering

from breathing difficulties, tuberculosis, and some mental illnesses were directed to health

resorts surrounded by forests [9]. Nowadays, so-called forest therapy and forest bathing are

becoming more popular [10–12], and involve walks in the forest in each period (a weekend,

a week, or longer) depending on the ailments and the person’s health [13]. This concept

was introduced in Japan in 1982 by the Forestry Agency, and since then it has been gaining

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031537

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

2 of 16

popularity, particularly among corporate employees where a significant number of worker

deaths had been observed [14]. Nowadays, these methods are used in other countries

as well [10,15]. The medical community has welcomed forest therapy as a preventive

treatment [13] and it has been used to assist in the recuperation and rehabilitation process.

The therapy aims at stimulating the body to self-heal through contact with nature in the

forest. It has also been used in treating disorders that occur due to stress, depression, and

ageing, and to improve overall health and wellbeing (the rustling sounds of trees, bird song,

and the greenery have a soothing effect). Walking in the forest has also been suggested to

humans as a form of minimal physical activity, getting fresh air (oxygenate the body), and

improving blood circulation [10,11,14,16]. Moreover, spending time in the forest distances

people from places where they usually spend time, e.g., the workplace, and distracts them

from everyday activities, reduces stress levels, and improves mood and concentration [17].

Forest bathing has a positive influence on emotions and regeneration, and increases the

level of vitality, which has been emphasised by Karjalainen et al. [18] and Bielinis et al. [19].

Healing properties of the forest stem from its microclimate, which is shaped by essen-

tial oils (phytoncides). They are recognised for their antibacterial, fungicidal, and antiviral

properties [20]. Hence, forest therapy should be popularised in society, especially in many

places on the planet where forests are easily accessible. Walking in the forest is a cheap

leisure activity that is of vital importance for elderly people and the ill whose economic

situation is precarious [16].

Despite numerous benefits that the forest offers, there are also people who do not like

the forest and perceive it as an alien and dangerous place, evoking anxiety and uneasi-

ness [21]. In some situations, the forest ecosystems can be threatening to human health.

People who are in frequent contact with the forest can be exposed to infectious diseases

connected with it. The vectors of these diseases can be the arthropods and mammals living

in the forest. Examples of such diseases are Puumala orthohantavirus (PUUV, transmitted

by the bank vole), Lyme disease, and tick-borne encephalitis (transmitted by ticks) [22].

Another why the forest evokes fear are dangerous animals, as well as poisonous plants and

mushrooms that can be found there. Also, some animals and plants which are part of the

forest ecosystems cause allergies and skin reactions [18].

1.2. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Importance of the Forest

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (in April 2020) it was evident that

the situation was going to impact forests and forestry [23]. In Poland, the first case was

diagnosed on 4 March 2020, while the first regulations to limit the spread of the coronavirus

were introduced on 13 March 2020. Regulations [24] limited the possibilities of movement,

the functioning of certain institutions or workplaces, and established a ban on assembly.

So far, these restrictions have appeared in Poland depending on the number of infected

people. The State Forests National Forest Holding (PGL LP) also introduced a periodic

ban on access to the forest on 3–11 April 2020, under the slogan “Las Poczeka” (the forest

will wait). After that period, parks and forests were often the only “space of freedom” for

Poles with unlimited access [25]. Forests in Poland cover about 30% of the country’s area,

of which almost 81% are public forests. These are national goods, owned by all citizens of

the Republic of Poland, to which every Pole has free access. [26]. Currently, the distance

of the place of residence from the forest and the possibility of access are not a factor that

significantly affects the limitation of recreation in forests [25].

Derks, Giessen, and Winkel [27] compared the number of visitors to forests in Germany

before and during the introduction of restrictions and mandates against COVID-19. The

scientists concluded that the numbers of visitors to the forests doubled. People were also

more motivated to go to the forest for social reasons, such as meeting friends and family,

as well as for preserving physical and mental health [28]. A similar increased interest in

forest mid-COVID-19 pandemic was observed by Grima at al. [29]. The increasing trend in

forest visits during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2021, compared to the same months before

the pandemic in 2016 and 2017, was written about by Bamwesigye et al. [30]. Many other

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

3 of 16

scientists noted an increased number of people who strolled and rode bikes along rivers or

in parks and forests during the lockdown [31,32]. During the pandemic, people pay special

attention to the risk of infection, and the forest, unlike public space, is not a crowded place.

Especially at the times when recreation, sport, and cultural facilities, as well as shopping

centres, were closed, the forest was one of few free spaces where Poles could spend their

free time [25]. The pandemic made Poles change summer holiday plans [33,34], both due

to travelling restrictions and deteriorated financial situations [34], particularly for people

whose business activity suffered because of the restrictions. The majority of people had

to limit their expenses on recreation [9]. The pandemic functioned as an inhibitor for the

tourist industry [35,36] but it also evoked the substitution effect on the tourist market [33].

One of the substitutes for domestic and international tourism could be trips to the forest.

During the pandemic, the forest can be a particularly popular place for walks, considering

the necessity to avoid crowds as well as the opportunity to find peace and relaxation from

everyday life [25]. In such a situation, it is important to notice that spending time in the

forest on a regular basis boosts the immune system [9,20] by mitigating the effects of social

isolation and loneliness, which have a negative impact on both physical as well as mental

health [37].

2. Materials and Methods

The increase in the number of people visiting forests is a challenge for those who

manage forests as well as for urban forest policy [27]. The boom of visitors generates the

need for integrated forest management [38] that can respond directly to the social need

and will be suited to people’s needs and expectations. The strategy should be based on

the understanding that management measures are essential to deliver various ecosystem

services needed by society [27]. In this context, it seems especially important to canvass

popular opinion about the forest and forest recreation. And this topic was increasingly

taken up by researchers, such as Bamwesigye et al. [30], Mateer et al. [39].

2.1. The Aim, Problem, and Hypothesis of the Research

Considering the above ideas, the aim of this study is to learn about the attitude of the

Polish people towards the forest regarding chosen sociodemographic variables. The aim of

the study was to determine the attitude of Poles towards the forest amid the COVID-19

pandemic. The pilot studies conducted by Baranowska, Koprowicz, and Korzeniewicz [25]

reveal that during the restrictions, to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the forest gained

significance as one of few spaces of freedom for Poles. The study participants indicated that

the lower transmission risk of SARS-CoV-2 virus is one of factors which encouraged walks.

Hence, it is necessary to inquire about a general attitude of the Polish people towards the

forest amid the pandemic and what are the characteristics of this attitude.

The following research question has been formulated: What are the sociodemographic

factors of Poles’ attitude towards the forest? The dependent variable is the attitude towards

the forest expressed by results of LAS scale which includes three areas: the Benefits of forest

recreation, the fears connected with the forest, and involvement in exploring the forest.

The independent variables controlled in the study are sex, age, professional activity, work,

education, place where the respondents live, and their living conditions.

We formulated several hypotheses: (1) women express more fears connected with

going to the forest then men, (2) elderly people see more benefits connected with the forest

than younger respondents, (3) people with secondary and higher education express fewer

fears connected with being in the forest and see more benefits, (4) people living in the

country see more benefits of forest recreation and are more involved than people living in

the cities, (5) people living in a block of flats see more benefits of being in the forest than

people who have their own gardens, (6) people who are professionally active see more

benefits connected with the forest, but they are also less involved than people who do

not work, and (7) people who work in professions connected with forest management are

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

4 of 16

more involved and express fewer fears connected with the forest than people who work in

other professions.

2.2. Research Tools

The study was conducted using the survey diagnostic method and two research tools

were used:

1. Sociodemographic background questionnaire that consisted of questions about the

independent variables.

2. LAS scale—independently prepared tool for measuring the attitude towards the forest.

The tool is characterized by good reliability expressed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient

at the level of 0.90. Its theoretical relevance was determined by subjecting the items to

competent judges and by factor analysis. The scale contains 20 statements, to which

the respondents refer on a scale from 1—“strongly disagree” to 5—“strongly agree”.

It consists of three factors. The first one, “Benefits”, consists of eight statements

(such as: “I rest and relax in the forest very well”, “The forest helps me to improve

my health”) concerning the experience of pleasure and health benefits connected

with spending time in the forest. The second factor, “Involvement”, included eight

statements that determine the extent to which respondents are involved in learning

about nature, understanding forest management issues, or working for the benefit of

the forest. There were such statements as: “I take part in tree planting campaigns”,

“I am interested in nature—I am keen on learning about various tree species or reading

about animals”. The last factor, “Fears”, containing four statements (e.g., “I am afraid

to go to the forest because of ticks” or “I worry that I will get lost in the forest”),

examines the concerns expressed by the respondents about being in the forest.

2.3. The Research Procedure

The results presented in the article are a part of a greater interdisciplinary study titled

“The approach towards the forest during the pandemic. Psychological and sociodemo-

graphic characteristics”. The analysed research tools, together with others that are a part

of the entire project, were shared on the Internet between February and May 2021. The

invitation to participate in the study was sent through social media. Students were asked

by their academic teachers who work at higher education institutions of various profiles.

Out of the 1071 questionnaires that were sent, 1025 were qualified.

Statistical calculations were conducted using Statistica 10 software (StatSoft Polska

Sp. z o.o., Kraków, Poland). The distribution of the results achieved in the LAS scale

deviates from normal, hence, to determine the differences between the particular groups,

the Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks

were adopted.

2.4. Surveyed People

In the study (survey), 1025 people participated, out of which 673 were women. The

ages of the subjects were between 19 and 68. To conduct comparisons, the respondents

were divided into three age groups. The aim was to create groups that were similar in

terms of numbers, hence percentiles were adopted, with the lower threshold established at

33.34% and the upper threshold at 66.66%. Thus, people up to the age of 22 were assigned

as the youngest group, and people over the age of 26 were assigned to the oldest group.

The detailed sociodemographic structure of the surveyed people is presented in Table 1.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

5 of 16

Table 1. Sociodemographic structure of the studied sample.

Variable

Sex

Age

Education

Place of residence/

Type of settlement

Type of dwelling

Professional activity

Type of occupation

Feature

Male

Female

Group I (ages 19–21)

Group II (ages 22–25)

Group III (26 and over)

Primary

Vocational

Secondary

Higher

Countryside

Small town (up to 20,000 inhabitants)

Town (between 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants)

City (above 100,000 inhabitants)

Detached house with a garden

Multi-family house with a garden

Block of flats

Professionally active

Professionally inactive

Retired

White-collar worker

Blue-collar worker

Service

Freelancer

Health worker

Uniformed services

Forestry

Professionally inactive

Share (%)

65.66

34.34

28.39

39.02

32.59

0.09

2.54

46.83

50.54

40.00

13.76

13.37

32.88

55.90

7.02

37.07

47.22

52.29

0.49

29.76

5.66

2.73

3.41

2.73

0.29

2.63

52.78

3. Results

3.1. Sex and Attitude to the Forest

The results of the Mann–Whitney U test indicate statistically significant differences

between males and females in the scope of all subscales in the LAS scale. In light of the

collected research material, the first hypothesis can be considered as a supported one—

females do indeed express more fears connected with going to the forest. Moreover, it

turned out that the differences between males and females occur also in Benefits and

Involvement (Table 2).

Table 2. Attitude to forest—comparing females and males.

LAS

Women

Men

n Median Quartile Range

n

Median

Quartile Range

benefits

37

8

36

7.5

involvement 673

26

10

352

30

10

fears

8

6

5

3

U

103,219

88,216

70,892

p-Value

0.001

0.001

0.001

3.2. Age and Attitude towards the Forest

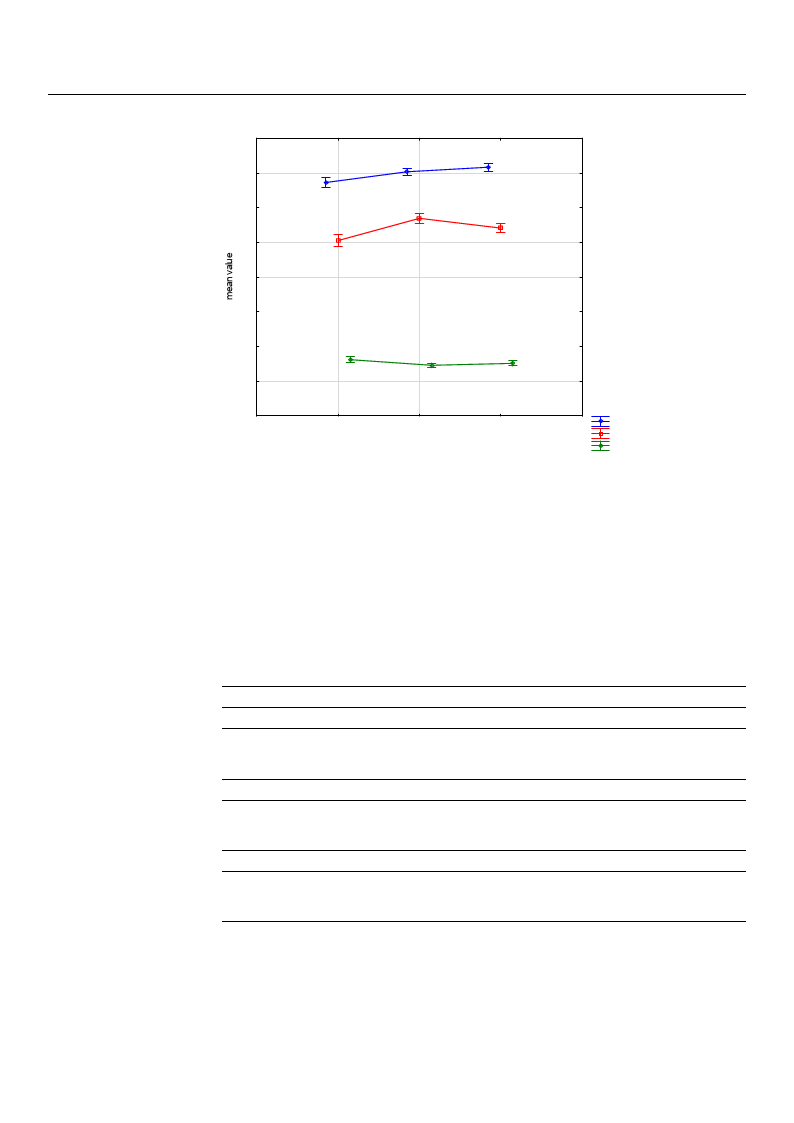

The results of Kruskal-Wallis test indicate a significant difference in the scope of noted

benefits from forest recreation (H (2, n = 1025) = 31.45, p < 0.01); involvement in exploring

the forest (H (2, n = 1025) = 34.74, p < 0.01), and fears connected with spending time in the

forest (H (2, n = 1025) = 8.93, p = 0.011), which were signalled by various age groups. The

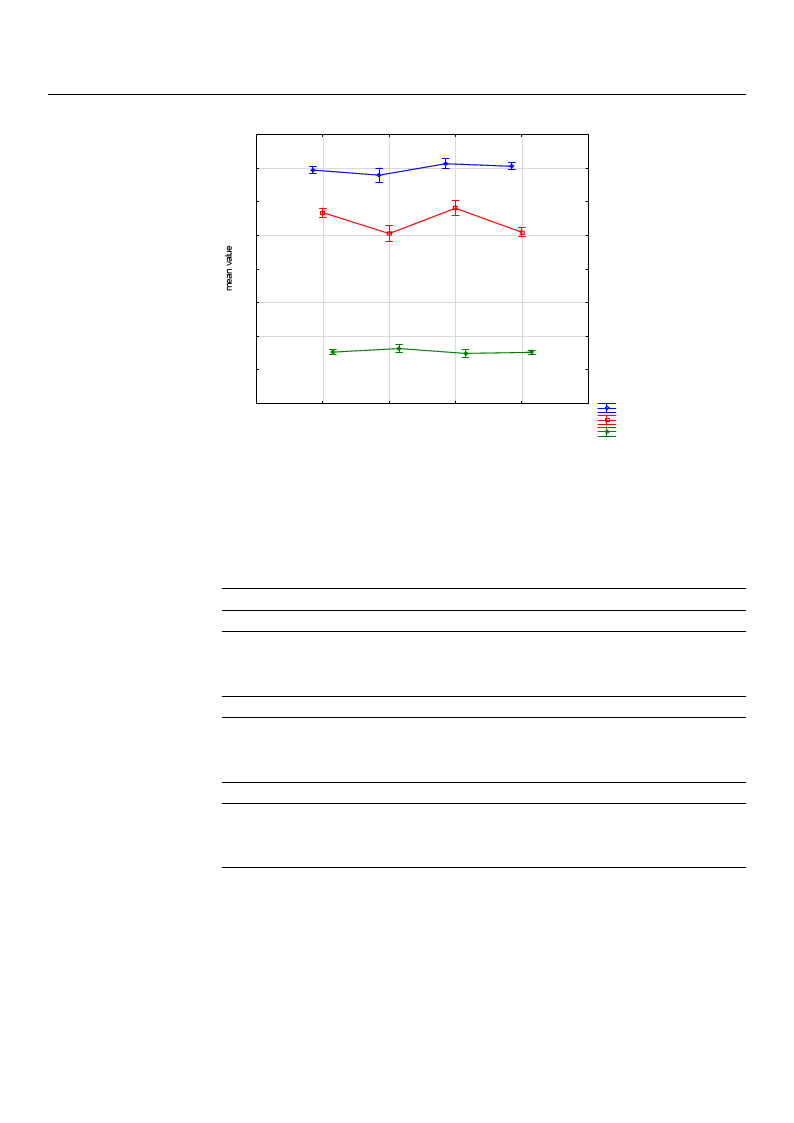

differences are presented graphically in Figure 1.

3.2. Age and Attitude towards the Forest

The results of Kruskal-Wallis test indicate a significant difference in the scope of

noted benefits from forest recreation (H (2, n = 1025) = 31.45, p < 0.01); involvement in

exploring the forest (H (2, n = 1025) = 34.74, p < 0.01), and fears connected with spending

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 202t2i,m19e, 1i5n37the forest (H (2, n = 1025) = 8.93, p = 0.011), which were signalled by various6aogfe16

groups. The differences are presented graphically in Figure 1.

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

group I

group II

group III

AGE GROUPS

LAS benefits

LAS involvement

LAS fears

FFigiguurere1.1A. Atttitiutuddeetotoththeefoforersets—t—mmeaenanchchaartrtfoforrggrorouuppssddivividideeddbbyyaaggee. .

PPoosts-th-hooccaannalaylysissis(D(Duunnnn’s’stetsets)t)hheleplpededtotoddeteetremrminineewwhhicihchoof fththeeththrereeeggrorouuppssththee

ddififfefererenncecsesininpapratirctuicluarlasrcaslceasleosf tohfetahtetitautdtietutdoethteoftohreesftohraevstehreaavceheredatchheendetcheessnareycelsesvaerly

olfesvtealtiosftisctaaltsisigtincaiflicsaignnceifi(cTaanbclee (3T)a. bOlen3t)h.eO“nBethneef“itBs”enaenfidts“”Inavnodlv“eInmveonltv”e,msceanlte”a, lslctahlereaell

gtrhoruepesgdroifufeprssdiginffiefricsaingtnlyififcraonmtloynferoamnoothneera. nTohtehoelrd. eTshtepoelodpelsetipnetohpelsetuindythgersotuupdy(ggrorouupp

II(Ig)rroeucpogInIIi)zeretchoegmniozset tbheenemfiotsstcboemnienfigtsfrcoommcinongtafrcotmwictohnntaactut rwe,itwhhnearetuarset,hwe hyeoruenagsetshte

gyroouupng(egsrtogurpouI)ps(egersouthpeIf)esweeesstthbeenfeewfitess.tAbesnfeafir tass. A“Isnfvaorlavsem“Iennvto”lvisemcoenncte”rinsecdo,ntcheernree-d,

spthoenrdeesnptosnfdoremntsthfeorsmecothnedsaegcoengdroaugpe agcrhoiuepveadchsiiegvneifdicsaingtnliyfihcaignhtleyr hreigsuhletrsrtehsaunlttshtehoatnhtehre

oontehse. rInonthees.“IFneathrse”“sFceaalers,”thsecasltea,titshteicsatlalytisstiigcnailfliycasnigtndiififfcearnetndceifsfearpepnecaerseadpbpeetawreedenbegtrwouepen

IIgaronudpgIrIoaunpdI,gwrohuopeIx, pwrhesoseedxptrheessmedostthaenmxioestyt .anxiety.

TTaabblele33. .TThheessigignnifiificcaanncceeooffththeeddififfeferreenncceessbbeettwweeeennaaggeeggrroouuppss——rreessuullttssooffppoosstt--hhooccaannaallyyssiiss..

AAgge e

GGrorouuppI I

GGrorouuppIIII

GGrorouuppIIIIII

Group I

GGroruopupIII

GGGrorrououpuppIIIIIIII

Group I

GGroruopupIII

GGroruopupIIII

* p < 0.05.Group III

* p < 0.05.

GGrorouuppI I

GGrorouuppIIII

LLAASS——BBeenneeffiittss((HH((22,,nn==1012052)5)==313.14.54,5p, p< <0.00.10)1)

0.00.0030434* *

0.00.0030434* *

0.00.0000101* *

0.00.2052454* *

LLAASS——InInvvoolvlveemmeenntt(H(H(2(2, ,nn==11002255) )==343.47.47,4p, p<<0.00.10)1)

0.0001 *

0.0001 *

0.0001 *

LAS—0F.000e..100a310r330s31(*H** (2, n = 1025) = 80.9.003.00,70p57=5*0*.011)

LAS—Fears (H (2, n = 1025) =08.0.9039,5p*= 0.011)

0.0095 *

0.0095 *

0.01.80095* *

0.9038 *

0.1809 *

0.9038 *

GGrorouuppIIIIII

0.00.0000101

0.00.2052454* *

0.0133 *

0.00.0071533* *

0.0075 *

0.1809 *

0.09.0138809* *

0.9038 *

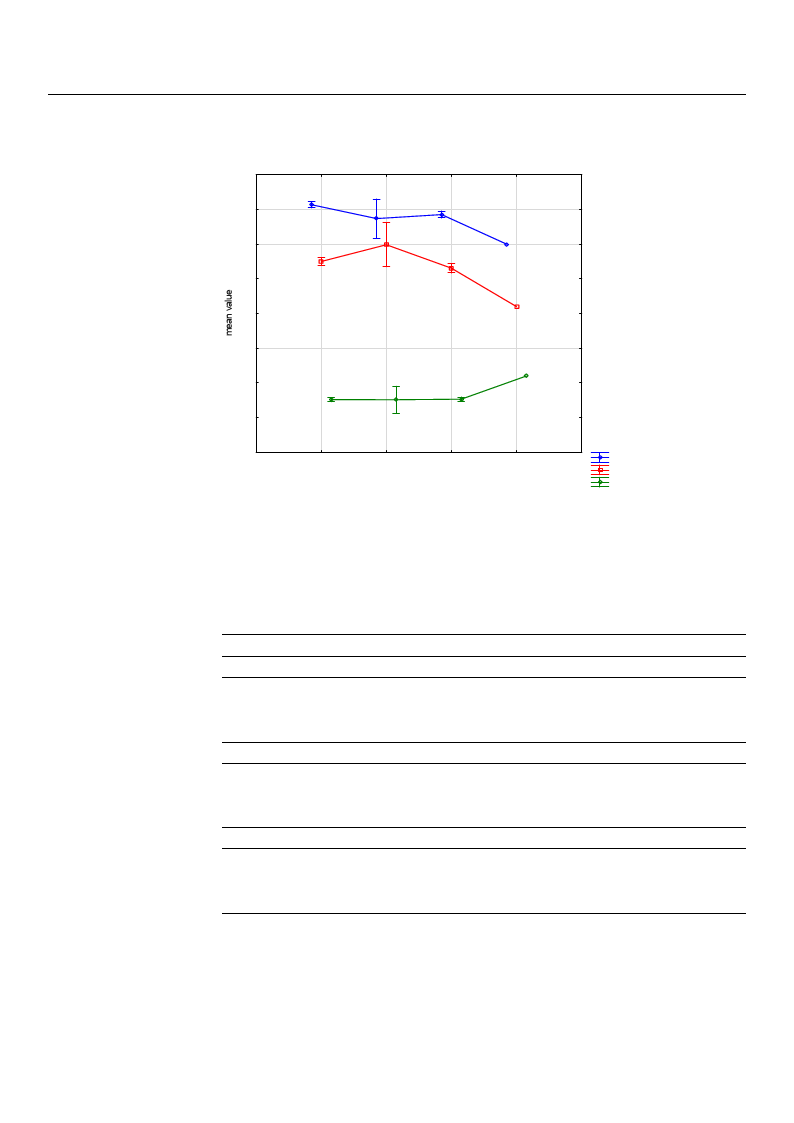

3.3. Education and Attitude towards the Forest

Statistical analysis has revealed that the respondents at various degrees of education

differ as far as forest Benefits are concerned (H (3, n = 1025) = 23.91, p < 0.01). Such

differences were not observed in the subscales focused on Fears H (3, n = 1025) = 2.48,

p = 0.48) and Involvement (H (3, n = 1025) = 10.81, p = 0.012). The mean comparison showed

3.3. Education and Attitude towards the Forest

Statistical analysis has revealed that the respondents at various degrees of education

differ as far as forest Benefits are concerned (H (3, n = 1025) = 23.91, p < 0.01). Such differ-

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 202e2,n1c9e, s15w37ere not observed in the subscales focused on Fears H (3, n = 1025) = 2.48, p = 07.4o8f )16

and Involvement (H (3, n = 1025) = 10.81, p = 0.012). The mean comparison showed that

people with higher education most often acknowledge Benefits of spending time in the

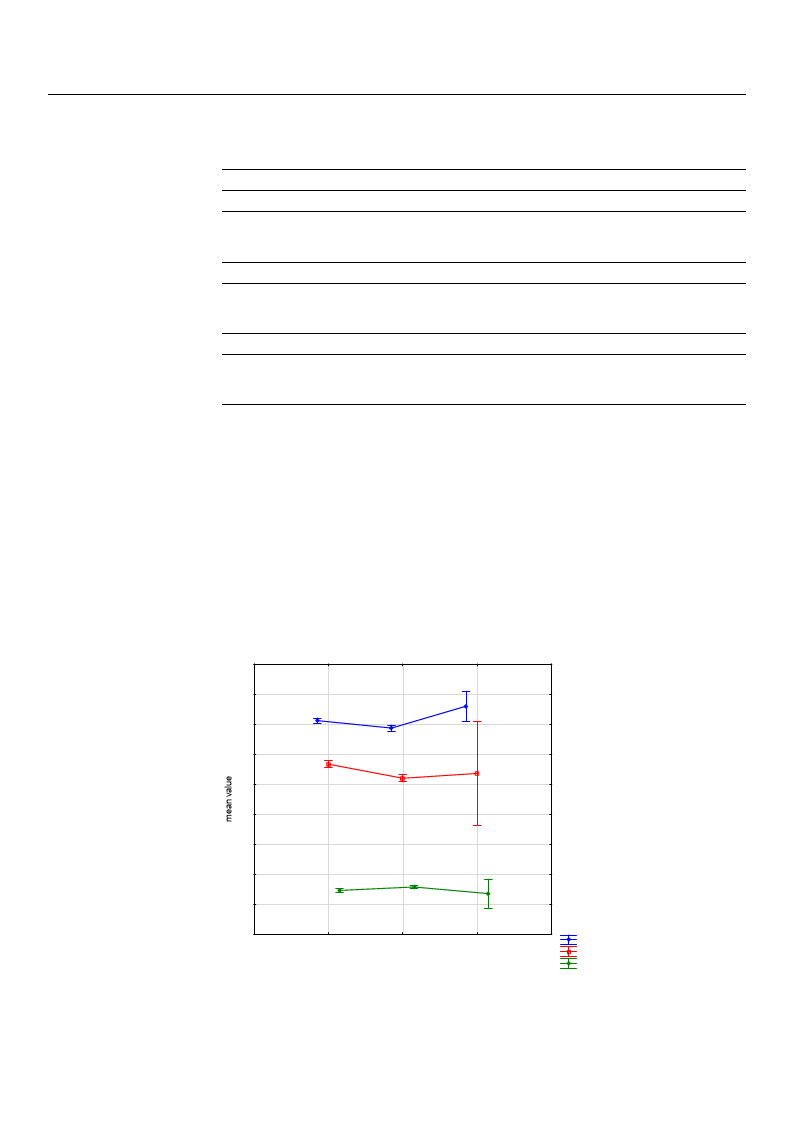

fothreastt,pweohpelreeawsiptheohpiglehewriethdupcriamtioarnymedoustcoatfitoenn—actkhneolewalsetdogfteeBne(nFeigfiutsreo2f )s.pending time in

the forest, whereas people with primary education—the least often (Figure 2).

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

higher

vocational secondary

primary

EDUCATION LEVEL

LAS benefits

LAS involvement

LAS fears

FiFgiugurere2.2A. Atttitiutdude etotothtehefofroersets—t—mmeaenanchcharatrtfofor rggrorouuppssddivivididededbbyyeedduucacatitoionnlelevveel.l.

TThheeppoosts-th-hococananalaylysissishhasasrerveveaelaeldedththatataastsatatitsitsitciaclallylysisgignnifiificacnant tddififfefreernenceceininththisis

scsocoppeeooccccuurrss oonnllyybbetewtweeenenpepoepoleplwe itwhihthighheigr hederuceadtiuocnaatinodn saencodndseacryoneddaurcyatieodnu. cAamtioonn.g

Aomthoenrggorothueprsgtrhoeudpisfftehreendcieffweraesnnceotwsatastnisotitcsatlalytisstiigcnalilfiycasingtn(iTfaicbalnet4()T. able 4).

TTaabblele4.4S. igSnigifniciafinccaencoef doifffderifefnecreenbceetwbeeetwn egernougprsoiunprsefienrernefceeretonceedutocaetidounclaetvioeln—lreevseul—ltsroesfuplotsst-of

hpocosatn-haolycsaisn.alysis.

EEdduuccaattiioonn

PPrriimmaarryy

VVoocactaitoinoanlal

SeSceocnodnadryary

LASL—ASB—enBenfietfist(sH(H(3(,3,nn==11002255)) == 23.9911,,pp<<00.0.011) )

PPrirmimaarryy

VVooccaattiioonnaall

SeSceoconnddaarryy

HHigighheerr

PPrirmimaarryy

VSVoeocccaoatntiiodonanraayll

SecHoingdhaerry

Higher

Primary

PVoricmataiornyal

VSoeccaotniodnarayl

SecHoingdhaerry

* p < 0H.05i.gher

11.0.00000

1.010.0000

11..00000000

1.010.000000

11..00000000

11..00000000

11.0.0000000

11.0.0000000

0.000.00020*2 *

LASL—ASI—nvIonlvvoelvmeemnetn(tH(H(3(3, ,nn==11002255)) == 1100..8811,,pp==00.0.0112)2)

010...088099077099

11..00000000

00.8.8979979

0.0657

00.3.0786657

1.010.000000

0.006.056757

0.1709

1L.0A0S0—0 Fears (H (3, n0=.31708265) = 2.48, p = 0.04.81)709

LAS—Fears (H (3, n = 1025) = 2.48, p = 0.48)

1.0000

1.0000

1.0000

1.0000

1.010.000000

1.00000000

1.0000

1.0000

11..00000000

11.0.0000000

1.0000

1.0000

1.0000

1.0000

* 3p.<4.0P.0l5a.ce of Residence and the Attitude towards the Forest

HHiigghheerr

11..00000000

11..00000000

00..00000022* *

11..00000000

000...313777808696

0.1709

1.0000

11..00000000

11..00000000

1.0000

The result of the analysis has revealed that the type of settlement where the respon-

dents live also differentiates their attitude to the forest as far as their Involvement is

concerned (H (3, n = 1025) = 55.83, p < 0.01). The differences concerning Fears (H (3,

n = 1025) = 5.14, p = 0.16) and Benefits (H (3, n = 1025) = 6.20, p = 0.10) appeared to be

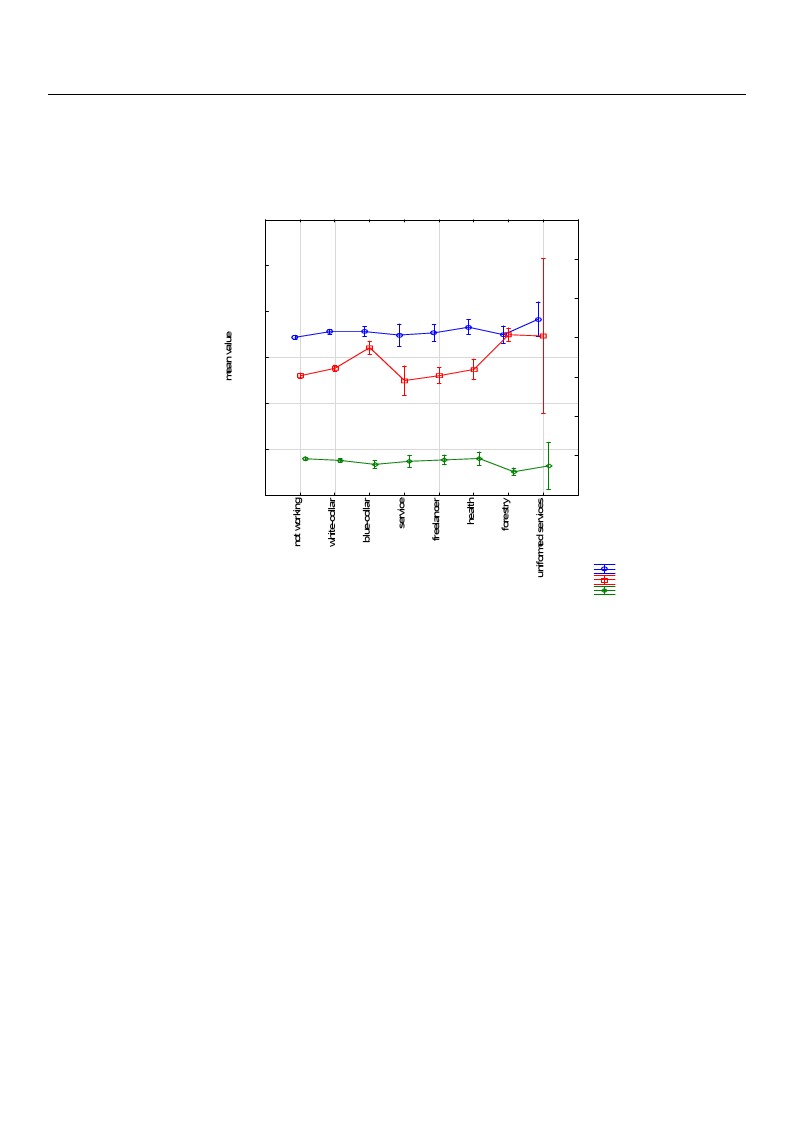

statistically insignificant. The collected means have been depicted in Figure 3.

3.4. Place of Residence and the Attitude towards the Forest

The result of the analysis has revealed that the type of settlement where the respond-

ents live also differentiates their attitude to the forest as far as their Involvement is con-

cerned (H (3, n = 1025) = 55.83, p < 0.01). The differences concerning Fears (H (3, n = 1025)

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 202=2, 519.1, 415,3p7 = 0.16) and Benefits (H (3, n = 1025) = 6.20, p = 0.10) appeared to be statistic8aollfy16

insignificant. The collected means have been depicted in Figure 3.

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

countryside

tow n

small tow n

city

PLACE OF RESIDENCE

LAS benefits

LAS involvement

LAS f ears

FiFgiugurere3.3A. Atttituitduedetotothtehefofroersets—t—mmeaenanchcahratrftofrorgrgoruoupps sbbasaesdedoonnththeepplalcaeceoof freresisdideenncece. .

TThhe eppoosts-th-hococananalaylsyississhshowowededthtahtatrerseisdidenetnstsofofvvilillalgaegsesananddsmsmalallltotwownsnsaraeremmoorere

ininvvoolvlvededininlelaeranrnininggabaobuout tananddexepxplolroirninggththeefofroersetsat nanddaraeremmoroereininvvolovlvededininwworokrikninggfofror

ththeierirbbenenefeifitstsththaannininhhaabbitiatanntstsoof fbbigigtotowwnnssaannddccitiiteiess(T(Taabblele55))..

TTaabblele55. .SSigignnifiificcaanncceeooffddiiffffeerrences between ggrroouuppssiinnrreefefererenncecetototytpyepeofopf lpalcaecoeforfesriedseidnecne—cer—esruel-ts

suolftspofstp-hoostc-haoncalaynsaisl.ysis.

TypeToyfpSeeotftlSeemttleenmtenTt he CoTuhnetrCyountrySmallSTmoawll nTown BigBTigoTwown n

CCitiyty

LASL—ASB—enBeenfietfist(sH(H(3(,3,nn==11002255)) == 66..2200,, pp==00.1.100))

The cTohuenctoruyntry

SmalSlmtoawll ntown

0.6976 0.6976

0.69706.6976

1.010.000000

1.010.000000

Big tBoiwgntown

1.0000 1.0000

0.23605.2365

City City

1.0000 1.0000

1.00010.0000

0.304.034303

1.10.0000000

1.10.0000000

0.03.4340033

LASL—ASI—nvIonlvvoelvmeemnetn(tH(H(3(3, ,nn==11002255)) == 5555..8833,,pp<<00.0.011) )

The cTohuenctoruyntry

SmalSlmtoawll ntown

BigCtiBotyiwgCntiotywn

The cTohuenctoruyntry

SmalSlBmtoiagwlltontowwnn

Big towCnity

* p < 0.05C. ity

1.00010.0000

0.000.0100*1 *

1.0000 *1.0000 *

0.000.00100*1 *

0.0001

0.0001

**00..00000011

*

*

00..0000001100..00**000011

*

*

1.010.000000

LASLA—SF—eaFresar(sH(H(3(,3n, n==11002255))==55..1144,, pp == 00..1166))

0.2528

0.2528

1.0000

1.0000 1.0000

0.25208.2528

0.3561

0.35611.0000

1.010.000000

0.305.635161

1.0000

1.0000

1.0000

1.0000

0.00.00011**

0.00.0000011**

1.10.0000000

1.10.0000000

1.110..00000000000

1.0000

* p < 0.05.

The variable known as “type of dwelling” (living conditions) has recognized the

following types of houses: a block of flats, a detached house with a garden, and multi-

family houses with access to a garden. This variable also differentiated the respondents’

in reference to Involvement (H (2, n = 1025) = 18.85, p < 0.01), but it does not matter as

far as Benefits (H (2, n = 1025) = 1.99, p = 0.37) or Fears (H (2, n = 1025) = 1.23, p = 0.54)

are concerned. Statistically significant differences on the “Involvement” scale occurred

between people who live in a block of flats and other groups (Table 6).

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

9 of 16

Table 6. The significance of differences between groups in reference to type of the house—results of

post-hoc analysis.

Type of House

Block of Flats

Multi-Family House Detached House

LAS—Benefits (H (2, n = 1025) = 1.99, p = 0.37)

Block of flats

Multi-family house

Detached house

1.000

1.000

1.000

0.5883

1.000

0.5883

LAS—Involvement (H (2, n = 1025) = 18.85, p < 0.01)

Block of flats

Multi-family house

Detached house

0.0068 *

0.0003 *

0.0068 *

0.8314

0.0003 *

0.8314

LAS—Fears (H (2, n = 1025) = 1.23, p = 0.54)

Block of flats

Multi-family house

Detached house

* p < 0.05.

1.000

0.9391

1.000

1.000

0.9391

1.000

3.5. Professional Activity and Attitude towards the Forest

In the scope of declared professional activity, three groups were distinguished: profes-

sionally active, professionally inactive, and those whose activity ceased due to retirement.

The variable appeared to be a factor differentiating the respondents as far as Benefits (H (3,

n = 1025) = 14.48, p < 0.01), Involvement (H (2, n = 1025) = 26.5, p < 0.01), and Fears (H (2,

n = 1025) = 9.48, p < 0.01) are concerned. At the same time, the post-hoc analysis shows that

the differences reach a satisfactory level of statistical significance only when comparing

people who are professionally active and inactive, but not when comparing with people

who retired (Figure 4). People professionally active perceive more benefits connected with

forest recreation than people professionally inactive; they are also characterized by highest

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 1I9n, xvFoOlvRePmEEeRnRtEiVnIEtWhe studied group. Also, they express fewer Fears about s1p0eonfd1i6ng time in

the forest than professionally inactive people.

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

active

inactive

retired

PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY

LAS benefits

LAS involvement

LAS fears

FFigiugruer4e. 4A.tAtittutidteudtoethtoe tfhoreesfot—remste—anmcehanrt cfohragrtrofuopr sgbroasuepdsobnatsheedpolancethoef rpelsaidcenocfe.residence.

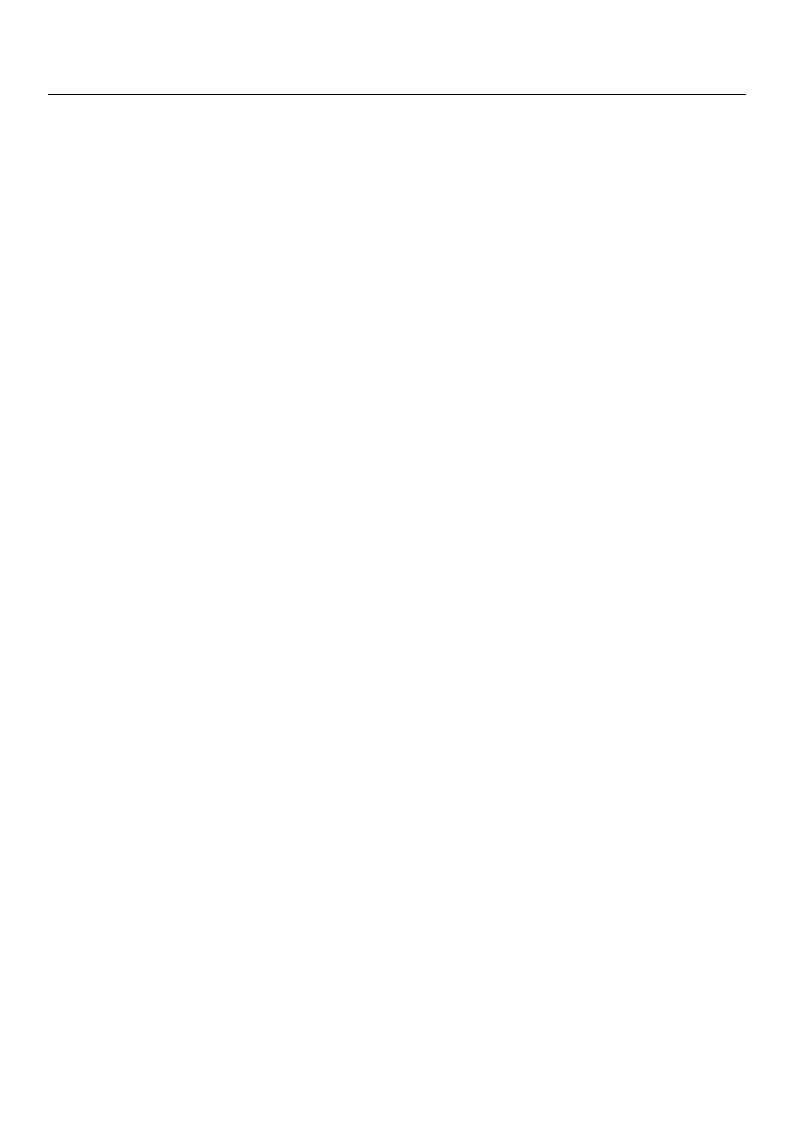

TyTpyepeofoofcoccucpuaptiaotnioanlsaolsaoppaepapredarteodbteo abesiagnsiifgicnainfitcvaanrtiavbalreiatobldeettoerdmeitneermthieneret-he respon-

spdoenndtse’natst’tiatuttdituedtoe wtoawrdarsdtshtehfeofroersets.tI.tItdidfiffefreerennttiaiatteess tthhee rreessppoonnddeennttssininrreefefererenncecetoto Benefits

Benefits (H (7, n = 1025) = 15.483. p = 0.03) and Involvement (H (7, n = 1025) = 86.64. p <

0.01) as well as Fears H (7, n = 1025) = 32.23, p < 0.01). As expected, people whose occupa-

tion relates to the forest are characterized by an increased Involvement and fewer Fears

than other respondents (Figure 5)

0

active

inactive

retired

PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY

LAS benefits

LAS involvement

LAS fears

Figure 4. Attitude to the forest—mean chart for groups based on the place of residence.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

10 of 16

Type of occupation also appeared to be a significant variable to determine the re-

spondents’ attitude towards the forest. It differentiates the respondents in reference to

Be(nHef(i7ts, n(H= 1(70,25n) == 11052.458)3=, p15=.408.033.)pa=nd0.I0n3v)oalvnedmInenvto(lHve(m7,ennt=(1H02(57), =n 8=61.6042,5p) <= 08.60.16)4a.spw<ell

0.0a1s)FaesawrseHll a(s7,Fnea=rs1H025(7),=n3=21.2032,5p) =<302.0.213),. pA<s 0e.x0p1e).cAtesde, xppeeocpteledw, pheoospeleocwchuopsaetiocncurepla-tes

tiotno rtehleatfeosretosttahree fcohraersat catreericzheadrabcytearniziendcrbeyasaendinIncvreoalsveedmIennvtoalvnedmfewntearnFdeaferswtehraFneoatrhser

tharenspotohnedrernetssp(oFnigduernets5()F. igure 5)

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

OCCUPATION

LAS benefits

LAS involvement

LAS fears

FigFuigreur5e. A5.tAtittutidtuedtoe tohethfoerfeosrte—stm—emaneacnhachrtafrot rfogrroguropuspbsabseadseodnotnyptyepoefoofcocuccpuaptiaotnio.n.

The assumptions were also corroborated by a post-hoc analysis. People professionally

connected with the forest in reference to Fears do not differ statistically significantly from

uniformed services and blue-collar workers (physical workers) and services. As far as

Involvement is concerned, they differ from white-collar workers, freelancers and services,

and health workers, but they do not differ from uniformed services and blue-collar workers

(physical workers). In this area, blue-collar workers differ from other groups, apart from

forest workers and uniformed services. In the Benefits subscale, the statistically significant

differences occurred only between professionally inactive people and white-collar workers.

People working in forestry do not differ from people of other types of occupations in the

assessment of benefits connected with forest recreation

4. Discussion

Despite the fact that it is women who feel more benefits connected with spending

time in the forest and forest recreation, men are more involved both in the work in forest

areas as well as in exploring nature. This has also been confirmed by studies done by

Gołos [7], who claimed that women who went to the forest more often also paid more heed

to the benefits connected with relaxation, learning, and educational processes, as well as

mood enhancement. Men, however, revealed a greater need for physical activity and a

need to satisfy their curiosity (seeking attractions) [40]. Women express greater fears of

encountering wild animals and ticks [41]. Hence, a trip to the forest with family and friends

can be important for women because they do not always want to go to the forest alone,

for safety reasons [42]. Studies from previous years (e.g., [43–45]) reveal that women and

people with higher education are more often characterized by ecological sensitivity than

other groups. Nevertheless, Trempała and Sadowski [46], who studied social attitudes

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

11 of 16

towards deforestation of tropical forests, proved that men were characterized by a higher

level of increasing biocentric attitudes than women. This view has also been confirmed

by our studies which focused on greater involvement and willingness of men to work to

forests’ benefit.

Hypothesis No. 2, which stated that older people recognize more Benefits connected

with the forest, has been confirmed. Indeed, the respondents from the oldest age group

are significantly statistically different in comparison to other studied groups. Moreover,

the conducted research reveals that age is a differentiating factor as far as Involvement

is concerned. On this scale, the highest results were achieved by the people ascribed to

the middle age group and this group also differs significantly from the youngest group

in reference to declared Fears. One of the factors that encourages people to visit nearby

green areas and forests is the willingness to socialize. Short social contacts in the forests

were identified as, for example, walks with a dog and other forms of leisure activity in

the forest with other people [47]. Participating in events that take place in forests can be a

source of social contact for people. Considering the benefits of spending time in the forest

for people, it seems rational to promote this type of leisure activity. A similar idea was

presented by Zawadka and Zawadka [16], particularly in reference to recreation and forest

therapy. It is important to pay special attention to the oldest people (over 65 years old)

and research should be conducted in this group because it is claimed that by 2060, the

number of people aged 65 and more will have increased up to 30% in Europe, and the

share of people above the age of 80 will also increase [48]. Hence, it is reasonable to make

changes and preparations in the forest for the rest and recreation of elderly people and the

disabled [49].

The third hypothesis assumed that people with higher and secondary education have

fewer Fears connected with the forest and acknowledge more Benefits. This hypothesis

has been only partially confirmed, particularly in reference to Benefits. Interestingly,

respondents with secondary education differ as far as Benefits are concerned only from

the respondents with higher education. The differences between people from other groups

dividing people by education were not found. Although it was visible that the mean

of fears is the highest in the group with primary education, the differences appeared

statistically insignificant. Tyrväinen et al. [50] pointed to the differences concerning the

way nature is perceived through the prism of age, health, status and psychological features,

and physical activity and education. In addition, Wierzbicka, Krokowska-Paluszak, and

Schmidt [51] reported that most tourists who visited Przeme˛t Landscape Park were people

with secondary or higher education. They stated that better-educated people are more

willing to spend leisure time outdoors; it may be due to the fact that they have a greater

awareness of the need to rest than those with a lower education [51], which also confirms

our findings. According to Grzelak-Kostulska and Hołowiecka [52], with higher education,

the awareness of the need to rest, especially as an active recreation, increases. The level of

education/projects to the need of spending leisure time actively in a natural environment,

which is beneficial to health, is realized by the people with higher education [52]. A partial

corroboration of the third hypothesis is quite surprising because the research into the level

of self-assessment of wellbeing during the pandemic revealed that education does not

depend on it. The lower a respondent’s education, the more pessimistic they were in their

questionnaire answers. Simultaneously, people with higher education indicated the need

to give up recreation more often [53].

In the study, the focus on the place of residence was twofold: both in reference to

the type of settlement as well as the type of house (dwelling) in which the respondents

live. The living conditions became particularly significant during lockdown to prevent the

spread of COVID-19 and also for people who were quarantined or who underwent home

isolation. It seems that people whose movement was restricted were forced to stay indoors

in a block of flats; naturally these groups could particularly feel the loss of relaxation

in the fresh air. People who have a garden were able to catch their breath and relax

during lockdown.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

12 of 16

The hypothesis No. 4 has been confirmed only partially. Indeed, people who live

in the country depict greater involvement than those who live in big towns and cities,

although they do not differ in this scope from people living in small towns. The assumption

concerning Benefits has not been confirmed; the respondents from cities do not differ from

people living in the country in this scope. Forest penetration and the choice of recreation

place are dependent on the location of the forest in reference to the place of residence

and the preferred type of recreation chosen by the respondents [54]. Da˛browski and

Zbucki [41] did not notice differences in limitations concerning forest recreation due to the

respondents’ place of residence. Gołos [7] indicates that people living in cities complain

about diminishing recreation areas, including forest and areas with trees (parks). People

living in the rural areas, to a great extent, do not experience the deficit of forest areas

because it is an inalienable element of their surrounding and lifestyle. Moreover, forests are

also a source of additional income for those who live in the country [7].

The predictions expressed in hypothesis No. 5 appeared to be erroneous. It was

assumed that during the pandemic, people living in a block of flats would appreciate the

opportunity to walk in the forest the most. The assumption was not confirmed. However,

the conducted research has confirmed that people living in block of flats are less involved

in exploring the natural environment than people who have the possibility of tending to

their garden on a regular basis. It is quite surprising because blocks of flats are built most

often in cities. The previous research indicates that spending time in the forest can lower

the impact of these factors on the human body [55,56]. Hence, the benefits of spending time

surrounded by nature should be appreciated by people living in blocks of flats, particularly

during COVID-19 lockdowns.

The hypotheses concerning professional activity assumed, among others, that people

professionally active acknowledge more benefits, but are also less involved than people

professionally inactive. The hypothesis was confirmed in reference to Benefits, however

the assumption about lesser Involvement was verified negatively. It would seem that

people professionally active have less time that could be spend in order to get involved in

forest exploration. However, it occurred that it is the opposite—it is those professionally

active who are involved the most. A possible explanation could be that people who

work seek isolation from the workplace, everyday chores, and activities. Our results

confirm the claims of Pietrzak-Zawadka and Zawadka [16], who indicate that health

tourism, which is particularly popular among professionally active people, is developing

dynamically nowadays.

Hypothesis No. 7, which assumed the occurrence of differences between people

working in forestry and forest management and respondents in the scope of Involvement

and Fears, has been positively verified. Interestingly, as far as Involvement is concerned,

people professionally linked with forests do not differ statistically significantly from people

who work in uniformed services and blue-collar workers; and as far as Fears are concerned,

apart from the two groups they also differ from people working in services. It seems that the

explanation of the results can be partially found in the procedure of the conducted research.

The respondents themselves had to choose their own type of occupation (explanations and

lists which occupations and jobs are included in each type were provided). Unfortunately,

the study conducted over the Internet did not provide the opportunity to solve any possible

doubts and inquiries about the adopted types of occupations. There is a possibility that

some people who work in forestry and forest management were classified as blue-collar

workers, i.e., physical workers.

5. Conclusions

The relationships between health and wellbeing, biodiversity, healthy ecosystems, and

climate change have been attracting attention of researchers and politicians internationally

over the last few years [1,57,58]. The current situation around the world added one more

issue to these ponderings, namely their relationships with the coronavirus pandemic [59].

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

13 of 16

A few years before the pandemic it had been observed that one of the most visited

places were suburban forest complexes. It stems from the increasing awareness about the

human need for recreation and, at the same time, an increased access to recreational places

outside the city (among others transport, infrastructure) [52].

During the pandemic, the role of the forest, as a place for relaxation, recreation, and

social gatherings, has increased. The living situation and personal features of character

shape people’s attitude towards the natural environment [60]; hence we attempted to

determine which sociodemographic variables are connected with Poles’ attitude towards

the forest in the presented study. The relationship was analysed in three dimensions:

Benefits, Involvement, and Fears. Most Fears connected with spending time in the forest

were expressed by women and people with primary education, whereas men, people who

live in the country and in small towns, people professionally active, and people working in

forestry were the most involved in exploring the forest and working to its benefit. In the

scope of observed Benefits of forest recreation, higher results were achieved by women, the

elderly, and respondents with higher education; additionally, white-collar workers notice

the benefits more often than professionally inactive people. Gathering opinions about the

forest, including the sociodemographic characteristics, may be helpful in implementing

forest practices that will meet contemporary social expectations [25]. Particularly, during

the pandemic an increased number of visitors in the forest was a challenge for forest

managers and for urban forest policy [27]. The increase in the number of visitors generates

the need to integrate forest management [38], which will directly respond to social demand

and will be suited to the needs and expectations of visitors. The strategy should be based on

the understanding that management measures are essential to provide various ecosystem

services, which society needs [27]. The results of further research will indicate the most

socially acceptable ways of managing forests. They will contribute to proposing alternative

methods in reference to, for example, currently used thinning methods, by replacing the

clear-cutting method and selection-cutting method with the patch-selection method of

forest management. The results of similar research will also support the decision concerning

the organization of tourism in forests, i.e., canalizing tourist flow in the forest area, creating

new parking spaces or creating an app, making it safer to use the forest.

Getting to know the needs and expectations of society in relation to the forest is

important, because the demands of the society are often based on individual, subjective

preferences [61]. Due to this fact, foresters should shape the attitudes of society in order to

limit the habits of people that may pose a threat to nature or contribute to losses in forest

management [7]. The results of social research make it possible to define the target scope

and forms of forest recreation areas management, the evaluation of non-market values of

the forest, as well as the benefits and risks resulting from multifunctional forestry.

6. Limitations

The adopted procedure of conducting the studies via the Internet made it possible to

collect a considerable sample of people from various environments. Naturally, the approach

has its limitations. One of the issues was representativeness: to take part in the study it,

was necessary to have access to a computer and the Internet so the potential respondents

could receive a link to the questionnaire; also, the topic of the study had to be interesting

enough for people to devote their time and fill in the questionnaire. In such a case, it is

difficult to infer a random choice of the sample, which would increase its representativeness

and also the possibility to generalize the achieved results. Another vital value limitation

of the adopted procedure is the possibility of filling in the questionnaire multiple times

by the respondents or its absolute anonymity which can favour giving untrue data about

sex or age, for example. Moreover, no possibility to control the external factors, such as

distractions or the presence of third parties excluded the standard score of the research

conditions [62]. The number of the collected sample lowers the unfavourable influence

of the described factors on the achieved results; hence they can become an inspiration for

further empirical studies.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

14 of 16

The non-equivalence of the studied groups’ results in the necessity to treat some of the

results cautiously. Despite adopting nonparametric methods of data analysis, some of the

groups (such as the group of people working in uniformed services—3 people) are so small

that it is difficult to generalize conclusions coming from comparisons with other groups.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: A.K. and M.B.; methodology: A.K.; software: A.K., M.B.

and R.K.; analysis: A.K., M.B. and R.K.; investigation, A.K., M.B., R.K. and W.P.; resources: M.B. and

A.K.; data curation: A.K.; writing—original draft preparation: A.K. and M.B.; writing—review and

editing, M.B., A.K., R.K. and W.P.; visualization: R.K.; supervision: W.P.; project administration: A.K.

and M.B.; funding acquisition: R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of

the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding “Project No. 005/RID/2018/19” Wielkopolska

Regional Excellence Initiative in the field of life sciences at the Poznan´ University of Life Sciences

“Project financed under the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education in the years

2019–2022” and “TheAPC/BPC isfinanced/co-financed by Wroclaw University of Environmental

and Life Sciences”.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in

the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. World Health Organization. Health, Environment and Climate Change—Human Health and Biodiversity—Seventy-First World Health

Assembly; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

2. Kobbail, A.A.R. Local People Attitudes towards Community Forestry Practices: A Case Study of Kosti Province-Central Sudan.

Int. J. For. Res. 2012, 2012, 652693. [CrossRef]

3. Yang, H.; Harrison, R.; Yi, Z.F.; Goodale, E.; Zhao, M.X.; Xu, J.C. Changing perceptions of forest value and attitudes toward

management of a recently established nature reserve: A case study in southwest China. Forests 2015, 6, 3136–3164. [CrossRef]

4. Kindler, E. A comparison of the concepts: Ecosystem services and forest functions to improve interdisciplinary exchange. For.

Policy Econ. 2016, 67, 52–59. [CrossRef]

5. Tiemann, A.; Ring, I. Challenges and opportunities of aligning forest function mapping and the ecosystem service concept in

Germany. Forests 2018, 9, 691. [CrossRef]

6. Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.A.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster,

P.H.; et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819.

[CrossRef]

7. Gołos, P. Social and Economic Aspects of Non-Productive Functions of Forests and Forest Management—Results of Public Opinion;

Research Forest Research Institute: Se˛kocin Stary, Poland, 2018.

8. Winter, P.L.; Selin, S.; Cerveny, L.; Bricker, K. Outdoor recreation, nature-based tourism, and sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 81.

[CrossRef]

9. Sallmannshofer, L’.M.M. Areas and Sustainable Forest. Human Health and Sustainable Forest Management; FOREST EUROPE—Liaison

Unit Bratislava: Zvolen, Slovak, 2019.

10. Bielinis, E.; Jaroszewska, A.; Łukowski, A.; Takayama, N. The effects of a forest therapy programme on mental hospital patients

with affective and psychotic disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 118. [CrossRef]

11. Kim, J.G.; Shin, W.S. Forest therapy alone or with a guide: Is there a difference between self-guided forest therapy and guided

forest therapy programs? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6957. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

12. Jeon, J.Y.; Kim, I.O.; Yeon, P.S.; Shin, W.S. The physio-psychological effect of forest therapy programs on juvenile probationers. Int.

J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5467. [CrossRef]

13. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Individual differences in the physiological effects of forest therapy

based on Type A and Type B behavior patterns. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2013, 32, 14. [CrossRef]

14. Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.J.; Miyazaki, Y. Trends in research related to “shinrin-yoku” (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest

bathing) in Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 27–37. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

15. Grilli, G.; Sacchelli, S. Health benefits derived from forest: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6125. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

16. Pietrzak-Zawadka, J.; Zawadka, J. Forest therapy jako forma turystyki zdrowotnejp. Ekon. S´rodowisko. 2015, 4, 199–209.

17. Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [CrossRef]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

15 of 16

18. Karjalainen, E.; Sarjala, T.; Raitio, H. Promoting human health through forests: Overview and major challenges. Environ. Health

Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 1–8. [CrossRef]

19. Bielinis, E.; Takayama, N.; Boiko, S.; Omelan, A.; Bielinis, L. The effect of winter forest bathing on psychological relaxation of

young Polish adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 276–283. [CrossRef]

20. Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.I.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Li, Y.; Wakayama, Y.; et al.

Visiting a forest, but not a city, increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol.

Pharmacol. 2008, 21, 117–127. [CrossRef]

21. Milligan, C.; Bingley, A. Restorative places or scary spaces? The impact of woodland on the mental well-being of young adults.

Health Place 2007, 13, 799–811. [CrossRef]

22. Aydin, L.; Bakirci, S. Geographical distribution of ticks in Turkey. Parasitol. Res. 2007, 101, 1985–1988. [CrossRef]

23. KPMG. COVID-19 Sector Implications; KPMG: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2020.

24. Szumowski, Ł. Regulation of the Minister of Health of 13 March 2020 on the Declaration of an Epidemic Threat in the Republic of Poland in

the Territory of the Republic of Poland; Setting Log Republic of Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2013; pp. 1–10.

25. Baranowska, M.; Koprowicz, A.; Korzeniewicz, R. Social importance of the forest—report of pilot studies conducted during the

pandemic. Sylwan 2021, 165, 149–156.

26. Pawlaczyk, P.; Bohdan, A.; Grzegorz, A. An Attempt to Assess the Management of the Most Valuable Forests in Poland; Stowarzyszenie

Pracownia na rzecz Wszystkich Istot: Białystok, Poland, 2016.

27. Derks, J.; Giessen, L.; Winkel, G. COVID-19-induced visitor boom reveals the importance of forests as critical infrastructure. For.

Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102253. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

28. Kittl, B.; Lässig, R. The corona lockdown changed the Swiss population’s visits to the forest. News WSL 2020, 173, 4–9.

29. Grima, N.; Corcoran, W.; Hill-James, C.; Langton, B.; Sommer, H.; Fisher, B. The importance of urban natural areas and urban

ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

30. Bamwesigye, D.; Fialová, J.; Kupec, P.; Łukaszkiewicz, J.; Fortuna-Antoszkiewicz, B. Forest Recreational Services in the Face of

COVID-19 Pandemic Stress. Land 2021, 10, 1347. [CrossRef]

31. Parnell, D.; Widdop, P.; Bond, A.; Wilson, R. COVID-19, networks and sport. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–7. [CrossRef]

32. Rice, W.; Mateer, T.; Taff, B.D.; Lawhon, B.; Reigner, N.; Newman, P. The COVID-19 pandemic continues to change the way

people recreate outdoors: A second preliminary report on a national survey of outdoor enthusiasts amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

SocArXiv 2020. [CrossRef]

33. Niezgoda, A.; Nowacki, M. Experiencing nature: Physical activity, beauty and tension in tatra national park-analysis of tripadvisor

reviews. Sustainbility 2020, 12, 601. [CrossRef]

34. Uglis, J.; Je˛czmyk, A.; Zawadka, J.; Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.M.; Pszczoła, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourist plans:

A case study from Poland. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 405–420. [CrossRef]

35. Niezgoda, A.; Kowalska, K. COVID-19 as a tourist activity inhibitor as evidenced by Poles’ holiday plans. Stud. Perieget. 2020, 32,

9–24. [CrossRef]

36. Wojcieszak-Zbierska, M.M.; Je˛czmyk, A.; Zawadka, J.; Uglis, J. Agritourism in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19): A rapid

assessment from poland. Agriculture 2020, 10, 397. [CrossRef]

37. Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A.; Masi, C.M.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness Predicts Increased Blood Pressure: 5-Year Cross-Lagged

Analyses in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Psychol. Aging 2010, 25, 132–142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

38. Aggestam, F.; Konczal, A.; Sotirov, M.; Wallin, I.; Paillet, Y.; Spinelli, R.; Lindner, M.; Derks, J.; Hanewinkel, M.; Winkel, G. Can

nature conservation and wood production be reconciled in managed forests? A review of driving factors for integrated forest

management in Europe. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110670. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

39. Mateer, T.J.; Rice, W.L.; Taff, B.D.; Lawhon, B.; Reigner, N.; Newman, P. Psychosocial Factors Influencing Outdoor Recreation

During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 70. [CrossRef]

40. Ju˚ za, R.; Jarský, V.; Riedl, M.; Zahradník, D.; Šišák, L. Possibilities for harmonisation between recreation services and their

production within the forest sector—A case study of municipal forest enterprise Hradec Králové (CZ). Forests 2021, 12, 13.

[CrossRef]

41. Da˛browski, D.; Zbucki, Ł. Factors limiting the realization of free time in forest areas in the opinion of academic youth. SiM CELP

w Rogowie 2013, 16, 226–234.

42. Morris, J.; O’Brien, E.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Lawrence, A.; Carter, C.; Peace, A. Access for all? Barriers to accessing woodlands and

forests in Britain. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 375–396. [CrossRef]

43. Mcmillan, M.; Clifford, W.B.; Brant, M.R.; William, B. Social and Demographic Influences on Environmental Attitudes. J. Rural

Soc. Sci. 1997, 13, 12–31.

44. Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP

scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [CrossRef]

45. Aminrad, Z.; Zakaria, S.Z.B.S.; Hadi, A.S. Influence of Age and Level of Education on Environmental Awareness and attitude:

Case Study on Iranian Students in Malaysian Universities. Medwell J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 6, 15–19. [CrossRef]

46. Trempała, W.; Sadowski, S. Postawy społeczne wobec deforestacji lasów tropikalnych. Stud. Ecol. Bioethicae 2018, 16, 19–29.

[CrossRef]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1537

16 of 16

47. O’Brien, L.; Morris, J.; Stewart, A. Engaging with peri-urban woodlands in england: The contribution to people’s health and

well-being and implications for future management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 6171–6192. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

48. Da˛browska, A.; Janos´-Kresło, M.; Lubowiecki-Vikuk, A. Styl z˙ ycia wellness a zachowania osób starszych na rynku usług

prozdrowotnych services market. Wyzwania Ekon. Społeczne 2019, 47–64. [CrossRef]

49. Janusz, A.; Pochopien´ , J. Role of Forest in the light of consumer preferences. Zeszyty Naukowe Wyz˙szej Szkoły Humanitas Zarza˛dzanie

1997, 2, 62–73.

50. Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Neuvonen, M.; Borodulin, K.; Lanki, T. Health and well-being from forests—Experience from finnish

research. Sante Publique 2019, 31, 249–256. [CrossRef]

51. Wierzbicka, A.; Krokowska-Paluszak, M.; Schmidt, M. Turystyka w Przeme˛ckim Parku Krajobrazowym—Czego oczekuja˛ turys´ci?

Polish J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 23, 65–72. [CrossRef]

52. Grzelak-Kostulska, E.; Hołowiecka, B. Forests as places to meet the individual needs of activity and recreation of the population.

SiM CEPL w Rogowie 2013, 37, 104–110.

53. Kalinowski, S.; Wyduba, W. My Situation in the Coronavirus Period. Final Research Report; Institute of Rural Development and

Agriculture: Warszawa, Poland, 2020.

54. Janeczko, E.; Park, L. The social conditions of forest recreation: Case study. Tur. i Rekreac. 2005, 1, 25–28.

55. Morita, E.; Fukuda, S.; Nagano, J.; Hamajima, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwai, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Ohira, H.; Shirakawa, T. Psychological

effects of forest environments on healthy adults: Shinrin-yoku (forest-air bathing, walking) as a possible method of stress

reduction. Public Health 2007, 121, 54–63. [CrossRef]

56. Ochiai, H.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Takamatsu, A.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; et al. Physiological

and psychological effects of forest therapy on middle-aged males with high-normal blood pressure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public

Health 2015, 12, 2532–2542. [CrossRef]

57. Rinawati, F.; Stein, K.; Lindner, A. Climate change impacts on biodiversity-the setting of a lingering global crisis. Diversity 2013, 5,

114–123. [CrossRef]

58. Hirwa, H.; Zhang, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Leng, P.; Tian, C.; Khasanov, S.; Li, F.; Kayiranga, A.; Muhirwa, F.; et al. Insights on water

and climate change in the greater horn of africa: Connecting virtual water and water-energy-food-biodiversity-health nexus.

Sustainbility 2021, 13, 6483. [CrossRef]

59. Lajaunie, C.; Morand, S. Biodiversity targets, sdgs and health: A new turn after the coronavirus pandemic? Sustainbility 2021, 13, 4353.

[CrossRef]

60. McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis.

J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [CrossRef]

61. Janusz, A.; Piszczek, M. Providing access to forests for tourism and recreation in the area of the Regional Directorate of State

Forests in Krakow. SiM CEPL w Rogowie 2009, 14, 52–60.

62. Batorski, D.; Olcon´ -kubicka, M.; Nauk, S.; Ifis, S. Prowadzenie Badan´ Przez Internet—Podstawowe Zagadnienia Metodologiczne.

Stud. Socjol. 2006, 3, 99–132.