SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

Review article

Deep Ecology: Contemporary Bioethical Trends 1

Sandra Mijač 1, Goran Slivšek 2*, Anica Džajić 3

1 Department of Microbiology, Molecular Diagnostics Unit, Synlab Croatia, Zagreb, Croatia

2 Department of Intensive Medicine, Anaesthesiology, Intensive Medicine and Pain Management Clinic,

Clinical Hospital Centre Rijeka, Croatia

3 Department of Translational Medicine, Children’s Hospital Srebrnjak, Zagreb, Croatia

*Corresponding author: Goran Slivšek, goran.slivsek@xnet.hr

Abstract

Deep ecology emphasizes the importance of the ecological problems as a practical issue, and its

importance is in changing the human understanding of everything, including even man’s

understanding of who he is.

The aim of this paper was to present deep ecology, what it represents and how it has become a

significant ecological movement of the 20th century and to indicate the connection between

bioethics as new environmental ethics and deep ecology, as well as other environmental movements

which, in the contextualization of bioethics, emphasize changing the outlook on life, giving a better

knowledge of it, and allowing questioning of social actions and looking at events from different

aspects. The idea is to emphasize that man is not only an active, but also a responsible being which

is capable of making a paradigm shift in responsibility, and therefore, taking responsibility for all life

on Earth.

Content analysis and comparative method were introduced and applied for the requirements of

making this review.

Based on the obtained results, the review points to the need to create new ethics which could

introduce a general value system for all living and non-living things - a paradigm shift involving man

as part of nature and not opposed to it, and to successfully address these complex issues. It will take

a profound shift in human consciousness to fully comprehend that it is not only plants and animals

that need a safe habitat - because they can live without humans, but humans cannot live without

them.

(Mijač S, Slivšek G, Džajić A. Deep Ecology: Contemporary Bioethical Trends. SEEMEDJ 2022; 6(1); 129-

139)

Received: Oct 15, 2022; revised version accepted: Feb 8, 2022; published: Apr 27, 2022

KEYWORDS: bioethics, ecological and environmental concepts, sustainable development,

One Health, public health

129

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

Introduction

From the beginning of man’s life on Earth, every

invention and discovery he had made to ease life

was about subduing nature for his benefit (1). The

reason why the problem began to appear, back

in ancient times, is the importance of the

presentation of the course of human thought

and how changing this thought has led to the

consciousness that in its expression subjugated

the entire world around itself (2). Deep ecology

emphasizes the importance of ecological

problems as a practical issue, and its importance

is in changing the human understanding of

everything, including man’s awareness of

himself (3). The result produced would be that

deep ecology, pointing to the value of all living

things, also wants to point to the responsibility

that people have in their environment. The new

ethics must also have the dimension of

sustainability, which can be accomplished in the

frame of bioethics, as an interdisciplinary area of

science. It is necessary to change awareness so

that people can re-establish a relationship with

nature without perceiving nature as a resource

from which man will have a (short-term) benefit

(4). In that sense, international nature and

environment protection laws are deficient in

practice, and citizens also need to contribute to

ecological awareness.

By unifying human approaches in the

relationship to nature, this review aims to show

that this relationship has become threatened.

The aim was to determine whether deep

ecology finds its justification in the change of

awareness regarding human relationship to

people and nature and to show how and to what

extent environmental and nature protection

which exceeds ecology in its complexity is

carried out.

Deep Ecology

Scientists have the most significant

responsibility when it comes to preservation and

strengthening of the ethical principles in their

research and institutions, to act beneficially

upon this crossroad of fate from where one can

either crash into eternal doom or finally get into

130

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

the haven of peace (5). Increased interest in the

problem of the environment (i.e., the ecological

problem) began to appear during the 1970s, and

considering the need for new ethics, some

scientists and ecologists came up with the idea

of said ethic. That considered, Rand Aldo

Leopold, a forester, philosopher, writer, teacher,

and one of the greatest American biologists

called such ethics the ethics of the Earth, which

would, by expanding the boundaries of the

community, contain everything - from earth to

animals (1). He explained the base of his ethics,

which was to protect wholeness and stability,

and only then can the righteousness of the

matter itself be discussed. Arne Næss expanded

the thought behind such ecological movement

with the diversity between surface and deep

elements, where the surface elements mark our

avoidance to contaminate the environment

exclusively for our own benefit. In contrast, the

deep elements represent the protection of the

whole biosphere, regardless of the benefits a

human being could have (6). This division in the

surface and deep elements, that is, shallow and

deep ecology, points to the meaningful division

within contemporary ecological thought (7).

According to that, shallow ecology represents

the anthropocentric thought in which a human

being is above nature, and nature has only

instrumentalist value, while deep ecology goes

for the highest ecological norm: preservation of

the vital needs of everything living (8).

The maker of the term deep ecology, Arne

Dekke Eide Næss, who was born in 1912 and died

in 2009 in Oslo (1). He was one of the most

famous Norwegian philosophers, who taught at

the University of Oslo between 1937 and 1970,

where he also graduated and completed a

master’s degree. He taught semantics and

gathered a group of young philosophers and

sociologists who were applying empirical

methods to affirm the meaning of philosophical

terms. He also taught the philosophy of science

and the philosophy of Spinoza and Gandhi (9),

who also had a significant impact on him. As a

hiker and a tour guide of the first expedition to

the Tirich Mir mountaintop in the Islamic

Republic of Pakistan, his motivation for nature

and environmental protection was no wonder.

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

Although it is not about the motivation founded

on the reformist current of the ecological

movement, which only wants to prevent

contamination, Naess should be given a closer

look as a supporter of the revolutionary current,

who supports the original current, but who also

builds his philosophy seeking for new

metaphysics, cognitive theory, and ethics which

would solve the relationship between a human

being and nature. He called this (eco)philosophy,

which is contained in the term deep ecology and

synonymous with the terms fundamental

ecology, a new philosophy of nature, ecosophy,

or ecophilosophy T. In that regard, ecosophy T is

built starting with oneself, the change within

oneself – to act upon welfare as a whole (1). The

core of Næss’s philosophy is about connecting

everything into a whole, that is, the idea that

nothing works independent of the whole,

meaning that the relationships between people,

plants, and animals depend on one another.

According to that, two fundamental principles of

that philosophy stand out, as well as those of the

ecological movement: self-fulfilment and

biospheric equality (5). Contrary to health and

welfare of the population, more precisely the

population which lives and acts in the developed

industrial countries as a central theme of the

contemporary society fighting against the

contamination of the environment, Næss turns

to the inner knowledge of norms, values and

ethics, meaning that ecological science will

bleed into interdisciplinary practical life wisdom

(3). Naess called that transition deep ecology (9).

Furthermore, Næss and the American

philosopher George Sessions (who also referred

to the new ecological ethic which Næss

discovered in 1972 and referred to as deep

ecology) shaped and exposed the principles

which would work for the deep ecology

platform, in eight chapters in an article from

1984. Some of those principles are:

1.

The welfare and the success of human

and non-human life on Earth have their own

values (synonyms: intrinsic value, inherent

value). Those values do not dependent on the

usefulness of the non-human world for humans.

2.

The richness and diversity of life forms

contributes to the realization of these values.

131

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

People have no right to jeopardize that richness

and diversity unless the goal is to satisfy life

needs (6).

The authors state that, although those principles

relate to life when we talk about the term

biosphere, they are also meant to include the

unliving, like rivers, environment, and finally the

ecosystem. Naess replaces the term biosphere

with the term ecosphere, and that way he does

not limit himself to the form of life in the

immediate or global surroundings (9). In addition,

he replaces the term environment with the term

co-world to mark the place of a human in the

most truthful way possible.

Deep ecology increases the meaning of the

principle of letting the being be (10) while trying

to bring ecological consciousness to a higher

level and achieve a healthier ecological life.

Among other things, deep ecology is founded

on Darwinist thought, which tries to move the

human away from the centre of life and into a

natural circuit of existing (9). Because of that, the

Darwinist element presented in the deep

ecology builds a complex and contradictory

relationship. Deep ecology postulates that

exiting from evolutional and acceptable

circumstances, which Darwinism sets as an

imperative in the way of life, damages the

human civilization and nature (1). It exposes the

human being and breaks the illusion that

humans are wise enough to rationally manage

their physical and social environment, not taking

into account the evolutionary processes (9).

Another relevant characteristic of deep ecology

is its attitude towards wilderness, the only real-

world left, around which, because of its

ecocentric orientation, exists a cult of wilderness

(11). According to that, it advocates

ecoregionalism and condemns urbanization and

hypermobility. It is clear that deep ecology

nearly revises that pantheistic belief and

divinifies nature, but what needs to be

underlined is that it does not replace religion,

cults, or a mystical worldview, even though it has

mystical aspects. The possibilities and the

controversy of deep ecology are manifested

even in its basic statement about the concept of

intrinsic values, which states that every part of

nature is valuable in itself, and not because of

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

higher goals (human, for instance). In that regard,

humans are a part of nature and not its highest

achievement (9). However, nature is formed

hierarchically, with humans on top, which

subjects this concept to criticism and doubt (11).

By replacing the term biospheric egalitarianism

– in principle – with the term biospheric equality,

Næss equalizes all the organisms in the

biospheric community, and their equality is a

consequence of a relational interconnection,

which gives them an intrinsic value. The fact that

humans are at the top of the pyramid does not

mean that they are not responsible for it.

Understanding that a human being must satisfy

its needs to survive, Næss does not deny those

needs, but only for existential purposes, and

when human secondary needs and vital needs

of another species come into conflict, a human

being should sometimes abandon egoism

before the needs of other living beings (12).

The authors of the book Deep Ecology, Bill

Devall and George Sessions, think that all

organisms and entities in the ecosphere, as parts

of an interconnected whole, are equal by

intrinsic value. A question arises how all these

living, but diverse beings are equal by their

intrinsic value. Furthermore, one criticism may

be that even if there is an intrinsic value relating

to the whole, the book does not say anything

about the values of individuals. No individual is a

necessity for the survival of the ecosystem as a

whole (6). It is concluded that the ethics of the

deep ecology does not answer the questions

concerning the value of life of individual living

beings. The reason may be that the wrong

questions are being asked: ecological ethics

might be more acceptable when applied to the

level of species and ecosystem. In trying to

establish that value based on the ecological

ethics, a certain holistic feeling arises, a feeling

that a species or the ecosystem is not just a total

of individuals, but an entity in itself (3).

Authors like Lawrence E. Johnson, Frey

Mathews, and James Ephraim Lovelock include

species and ecosystems as holistic entities or

selves with their own form of realization (6). If the

species and the ecosystem can be considered a

type of an individual with its own interest, the

ethics of deep ecology must face the problems

132

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

of determining the moral value of the species or

the ecosystem again, regardless of the value

which it has because of its importance for

sustaining life (9). The fact that the biosphere can

react to events in ways that look like a self-

sustainable system does not show that the

biosphere wants to contain itself consciously (1).

This fact underlines that the ethics of deep

ecology must reject its moral base because the

argument stemming from the intrinsic value of

plants, species, and the ecosystem is

problematic (6). This, of course, does not mean

that the argument for protecting intact nature is

weak, but the argument based on the difference

between the feeling and non-feeling creatures

is firmer than the division between the living and

non-living (5). The arguments should show that

the value of preservation of the last significant

areas of untouched nature significantly

overcomes economic values (6).

A human must acknowledge that value as an

ethical category for that to happen, and

therefore, confirm its responsibility (13). If a

human’s realization of interests for his benefit is

acknowledged as an intrinsic value, then it must

also be acknowledged for other living beings

who are ensuring their well-being (11). Also, the

concept of the “right of nature” is doubtful

because it enters into a new manipulation. The

right to preserve natural resources is

contradictory to the concept of preservation of

intrinsic values (13). The task of intrinsic values is

building the marvel towards the wholeness of

existence which is independent of humans (11). It

stems from the fact that due to the prevalence

of big cities and mechanicalized environment,

such marvel cannot be seen or felt towards the

non-human, which is what the deep ecology

wants to revive. One of the objections to deep

ecology is humanist voluntarism, which

postulates that humans can change things by

their own will. Nevertheless, ecological

destruction occurred because of actions of

generations, and that is also why one generation

cannot change it.

The stumbling stone of deep ecology is that if it

cannot change people’s awareness, it cannot

lead to radical change (10). Modern ecology

states that nature existed before the first

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

humans and that it will continue to exist, which is

different from the understanding of tribal

societies, and this is something that can be the

encouragement for treating nature with more

respect. Tribal life, which deep ecologists

advocate, is unacceptable for most people. In

that regard, bioregionalism is unenforceable in

the global world (11). Talking about a relationship

of a human being towards nature that is filled

with awe, a German physician, theologian and

philosopher Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer is

the most noted expert in defending ethics by

expanding on sensitive beings (9). Using the

phrase “awe before life”, he builds the ethics of

awe, which is based on having equal awe before

every life, as well as one’s own life (11). He

shaped the first and extensive attitude of

philosophical biocentrism (7), but his ethics finds

itself before the question: What is it like in the

cases in which human life can be preserved only

then when another human life has to be

destroyed instead (14)?

Deep ecology sets a unique view of the

relationship towards evolutionism. Generally,

the attitude of the deep ecologists is that

modern life in industrial societies is not

evolutionarily adjusted (11). Tomislav Markus

understands that people did not kill nature, but

they abandoned the environment of

evolutionary adaptation. As the author points

out, deep ecology is closer to science and

philosophy, and it is not a moral lesson for

wealthy individuals (10). Markus points out that

knowledge in biology and ecology is essential

for understanding the relationship between

humans and nature. So is the awareness of the

pressure modern industrial societies put on the

environment, which means that evolutionary

adjustment to the environment is impossible.

Therefore, the author sets an imperative in

creating a new view of nature, human nature,

and human inadaptability to evolution (11).

Since the base of the humanist disciplines lies in

dualism, a human as a being is separated from

nature with its history about the self-creative

process, which is founded on biophobia and

ecophobia. The solution is found in the human

need to escape into the circumstances of an

organic existence (9), representing the escape

133

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

from environmental destruction. According to

that, deep ecology is the escape from

consumerism,

hyperurbanism,

hyper-

population, and all other significantly destructive

orders of the modern industrial society (15). The

solution might be seen in accepting naturalness

as a characteristic of human nature, which could

decrease environmental destruction. To stop

environmental destruction, in favour of life

preservation, deep ecology emphasizes the

change of the paradigm (1). That would mean

that the paradigm, which positions the human

being in a superior position looking at nature

exclusively as a resource, should change by

accepting the evolutionary insights about

people’s lives. It is trying to rise above

consumerism as one of the characteristics of

technical civilization. Markus thinks that there are

too many people living on this Earth who are not

one with nature and who, by that, challenge it by

destruction (11). The solution is in the tribal

communities, and the precondition is decreasing

the population. It is the tribal communities who

have the lowest rate of intervention in the

environment, as opposed to industrial societies

which replace life through the technical and, by

doing so, they put pressure on the environment.

According to Næss, the quality of life of an

individual and of an entire population cannot be

considered if the size of that population is

excessive. He agrees with decreasing the

population in a non-violent way through

voluntary birth control (12). Also, he thinks that

there should be a 100 million people less on

Earth. Numerous deep ecologists believe that

diseases, wars, and lack of food will more likely

lead to decreasing the population than the

rational, controlled way (10). For instance, when

Næss wrote about the solutions for

depopulation, there were six billion people in the

world, while today that number has exceeded

seven billion and is still growing. As partially

shown before, the two attitudes were

determined according to ecoethics: shallow and

deep ecology, which try to solve the problems

regarding human violations against nature (16).

Various ecological ethics or ecoethics appeared

because of the care for nature and the paradigm

change, as is the case with deep ecology. Deep

ecology, by pointing to the value of all living and

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

non-living beings, also wanted to indicate the

responsibility of all towards the environment (17).

That term, as well as others, lay the foundation

of bioethical principles, and the relationship

between bioethics and deep ecology (5).

Bioethics and Deep Ecology

Bioethics is a term that came into use in the

1970s, relating to ethical questions in the areas

of biology, medicine and psychology in order to

provide answers to the challenges of new

knowledge. Although the term bioethics, i.e.,

“bioethik”, was first used by Paul Max Fritz Jahr in

an article from 1927, the credits for

conceptualizing and preparing the term go to

Van Rensselaer Potter II, who built the

foundation for the development of bioethics in

his work in the 1970s (15). Since the meaning of

life is broader than the human or medicinal

aspect, bioethics questions the responsibility of

human action towards humans themselves, but

also towards all life on Earth, or better said

towards the biosphere (18). Namely, Potter

thought that ethical values cannot be separated

from biological facts, and he considered

bioethics to be a bridge between science and

humanity (19) which includes all living beings or,

in other words, a biosphere essential for

guaranteeing a future (20). Numerous

discoveries have brought new knowledge,

which he believed could not in itself be

completely bad or good, but that it represented

power, and, therefore, once available, it would

mostly be used for power (21). It is therefore

essential to know how to use new knowledge,

and that is possible only by possessing the

wisdom on how to use new knowledge (22). On

that end, he believed that bioethics as a science

of survival would provide the wisdom on how to

ensure sustainability (21). However, despite that,

bioethics is often synonymous with clinical,

medical or, the commonly called, biomedical

ethics, which is wrong and inconsistent with

Potter’s original idea of a global bioethics which

deals with man’s relationship with himself, but

also with the ecosystem (23). Bioethics cannot

be only clinical ethics because the concept

simultaneously contains elements of

environmental ethics — it is concerned with the

134

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

survival of man, but not any survival - the survival

which considers the survival of the ecosystem

that has its value, entirely independent of man

(24).

Finally, according to Potter, bioethics implies the

inevitable interconnectedness of man and the

rest of the living world (25), or in other words, an

interconnected biosphere (20). Deep ecology as

a part of environmental ethics understands

people as an indispensable part of nature or a

link in the chain of life, it points to the

interconnectedness and interdependence of all

parts of the ecosphere, emphasizes the

primordial value of all species regardless of

human needs, and it focuses on wisdom and

balance (26). Deep ecology can be seen as a

form of a radical environmental critique of the

technological civilization which reacts to

technolatry, anthropocentrism, instrumentalism

and resourcism, consumerism, and linear

progressivism which overtook society with the

emergence of new knowledge (27). Naess

considered deep ecology to be an ecosophy

developed under the influence of Leopold,

focused on wisdom, that is, the wisdom of the

Earth, which focuses on ecologically wise and

healthy living (28). It is shown that ecological

ethics, ecoethics, or environmental ethics gather

different theories, some of which are mentioned

here. For example, ecocentrism, biocentrism,

pathocentrism, or their mixed forms such as

ecocentrism and ecofeminism, as well as the

ethics of deep ecology from which each of them

stems, try to set a frame in order to discuss the

moral relationship between humans and

inhuman entities, by expanding the human

moral obligation to animals, plants or certain

areas of nature or life in general (29). Despite the

critics and the deficiencies to which deep

ecology subjected, the framework for building a

new theory is the concept of responsibility, more

precisely the responsibility of acting, as in

lighting the effects of knowledge (30). Also, new

ethics must have a dimension of sustainability,

which bioethics as an interdisciplinary field of

science can realize within the scope of its

content, and its strength can be seen in

generating a new sensibility and creating a new

awareness which goes past particular

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

dimensions and tries to preserve life to stabilize

all the segments of society (29).

In the works of Leopold and Potter, it is evident

that bioethics and environmental ethics share a

common source. The connection between

bioethics and deep ecology as part of the

environmental ethic is in their vision of an

interconnected biosphere (20). People are a part

of the natural world, and not just bystanders, and

based on that, the responsibility towards the

world around and towards each individual is

evident (31). Bioethics and environmental ethics

also share wisdom as a common root (21), mostly

because of new knowledge. It is precisely

because of that high complementarity between

bioethics and environmental ethics that, in 1988,

Potter proposed the introduction of the new

term global bioethics (32). Potter coined the term

global bioethics in an attempt to protect the new

science of survival from a growing transition into

a predominantly clinical ethics, but also to

further expand it with even more elements of

environmental ethics, especially under the

influence of Leopold’s legacy (33). However,

despite all that, bioethics and deep ecology

have over time developed into two separate

fields (20), which has led to the creation of a gap

between bioethics and environmental ethics

(34). Namely, bioethics has mostly developed

into clinical ethics, where the focus is on the

individual health of a human patient, while

environmental ethics has developed more with

the focus on biosphere health and not on

individual health, that is, on the health and

sustainability of the overall ecosystem (35).

Public Health Ethics as a Bridge Back to

Potter’s Bioethics

Public health ethics is a relatively new field,

coming into its own somewhere at the beginning

of the 21st century, and it is still in its

developmental stage but in recent years it has

become one of the fastest growing

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

subdisciplines of ethics (34). It is deeply rooted in

bioethics, clinical and research ethics, and also

in environmental ethics (36). Public health ethics

is primarily focused on policies, programs and

laws for the protection and promotion of public

health, and the focus is not on the individuals but

on the community (i.e., the population) when it

comes to achieving the common good (34).

Since health is a state of complete physical,

mental and social well-being and not merely the

absence of diseases or infirmity (20), the

complexity of public health, and thus of public

health ethics, is evident. The fact that human

health depends on the environment has been

known since the beginning of time, and today it

is increasingly clear that it also depends on

animal health, because the convergence of

humans, animals, and their products is more

pronounced than ever before (37). The current

coronavirus pandemic shows the importance of

interconnectivity of the domains of people,

animals, and the environment as a group of

interconnected circles when it comes to public

health, but also when it comes to the future of all

living things (38). Severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 is most likely the

product of ecological conditions created by

humans, while the related pandemic is a product

of the number, density, and connectivity of the

human species and its interaction of the

environment (39). It is obvious that the health of

humans is connected to the health of animals

and the environment, and, therefore, we can say

that the health of each of those three domains is

the product of interactions of triangles of their

health which, in fact, forms public health (40).

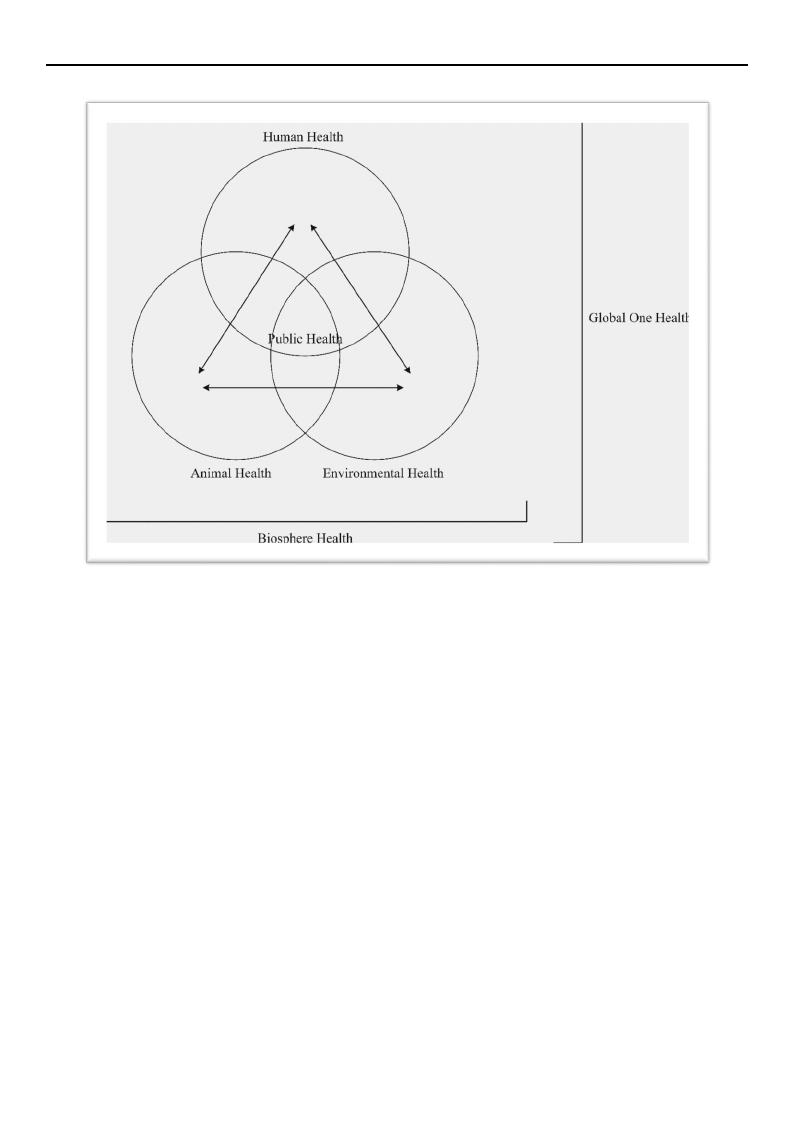

That kind of public health – the One Health

approach (41) – is in line with Potter’s vision of an

interconnected biosphere; hence it can be

considered as a planetary vision of One Health

(42) or Global One Health, and, consequently, we

can talk about the global public health ethics

(Figure 1) (43).

135

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

Figure 1 The expanded model of the Global One Health concept

Potter sought to include health, survival, and the

environment in the new ethics, which will

combine knowledge and deliberation in the

human constant quest for wisdom, that is, the

knowledge of how to use new knowledge for

the survival and progress of humankind (44).

Those qualities are contained and encouraged

by public health ethics, which on one hand

overlaps with bioethics, and on the other hand

with deep ecology as part of the environmental

ethics, while in its origins contains features of

global ethics (20). Public health ethics shows that

human health is strongly and inseparably linked

to the health of the planet (the biosphere) and

that the health of the community is essential for

the health of individuals, which in turn has a

strong impact on the health of the population

(45). That is not surprising since public health

deals with the health of the individual, but also

with the health of the environment, in order to

achieve the best possible health of the

136

population (20). The case of the coronavirus

pandemic underlines the need for a

fundamental shift in the human conception of

health, sustainability, and humanity, which is

only possible by returning to Potter’s bioethics,

which evaluates and considers all living beings,

or in other words, the biosphere (46). Based on

everything mentioned above, public health

ethics can be used to bridge the gap between

bioethics and deep ecology as part of the

environmental ethics to restore the values of

Potter’s bioethics for a brighter future of all living

things (34).

Conclusion

The history of ecology starts with the Neolithic

Revolution, although it seems that it was only

after the revolution that we heard about

ecological problems. It has been confirmed that,

at the same time when the human

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

anthropogenic activities started to change his

organic and wild environment, to which he is

genetically adjusted, began the alienation of the

wilderness that he has gotten used to (13). Of

course, it was not just humans who conditioned

the (negative) changes in nature; there were also

volcanic eruptions, asteroid collisions,

earthquakes, and floods – in other words, a

multitude of natural disasters to which most of

the living world is not adjusted and most of

which happened long before human existence.

With the development of civilization, the shaping

of cultures, and usage of technology, human

beings genuinely become active factors in

affecting nature. From Greek philosophy to

Cartesianism, nature was thought to be the

starting point for questioning everything (47).

Experiencing nature as a devalued magnitude

and the subject of knowledge conditions the

forming of new things, more specifically new

age humans. The new age products are modern

science and technology, in which science is the

beholder and technology is the executioner (48).

The role of technology is to satisfy the needs of

life as quickly and pleasingly as possible, and

through that, the consumer society is created,

which also affects the expansion of the

ecological crisis. It is no wonder that the

relationship of a human being and nature is

altered because of the eternal nature of modern

science and technology (49). Numerous

archaeological studies have shown that the

ecological problems started with the Neolithic

domestication, which has increased in intensity

in the last few centuries and led to an ecological

crisis (50). Although the ecological crisis does

not affect everyone equally, it is a problem that

significantly influences life and demands an

urgent solution, regardless of those who think

that the ecological crisis is either a reflection of

capitalism or industrialization, contrary to those

References

1.

Bhaskar R, Høyer KG, Næss P, editors.

Ecophilosophy in a World of Crisis: Critical Realism

and the Nordic Contributions. London: Routledge;

2012.

137

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

who believe that technology could solve the

problems of humanity (51).

Ecology contains many areas affected by

biosphere processes, which should be

contained to access the solution to its problems.

This should be done with the help of sustainable

development, which presents the principles of

sustainability of the system, a way of

development that does not degrade or violate

nature (50). However, to achieve progress, it is

people’s attitude towards nature that must

change, not their attitude towards themselves,

which is how Næss formulated it in his

philosophy, known under many other terms, but

mentioned here most often under the term

“deep ecology” (52).

The concept that emphasises the value of every

life — in (new) bioethics, ethics of life, which due

to its interdisciplinary area of impact can be

applied in reality, is enriched through that

responsibility (53). In recent years, it has come to

light that public health ethics can be used to

bridge the gap between bioethics and deep

ecology as part of the environmental ethics, thus

enabling the return to Potter’s bioethics which

has built-in values of deep ecology (54).

Although much has been done in recent years,

deep ecology is to a great extent still in its very

beginnings.

Acknowledgement. None.

Disclosure

Funding. No specific funding was received for

this study.

Competing interests. None to declare.

2.

Valera LE. El futuro de la ecología: la sabiduría

como centro especulativo de la ética ambiental [The

Future of Ecology: Wisdom as the Speculative Centre

of Environmental Ethics]. Cuad Bioet. 2016; 27(91):

329-338. Spanish.

3.

de Jonge E. Spinoza and Deep Ecology:

Challenging

Traditional

Approaches

to

Environmentalism. Aldershot: Ashgate; 2004.

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

4.

Akamani, K. Integrating Deep Ecology and

Adaptive Governance for Sustainable Development:

Implications for Protected Areas Management.

Sustainability

2020,

12,

5757.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145757

5.

Talukder MH. Nature and Life: Essays on

Deep Ecology and Applied Ethics. Newcastle upon

Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2018.

6.

Singer P. Practical Ethics. 3rd ed. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press; 2017.

7.

Jennings V, Yun J, Larson L. Finding Common

Ground: Environmental Ethics, Social Justice, and a

Sustainable Path for Nature-based Health Promotion.

Healthcare (Basel). 2016; 4(3): 1-9. doi:

10.3390/healthcare4030061

8.

Kopnina H, Washington H, Taylor B, Piccolo

JJ. Anthropocentrism: More than Just a

Misunderstood Problem. J Agric Environ Ethics. 2018;

31(1):109-127. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-

018-9711-1

9.

Cifrić I. Dubinski ekološki pokret: „Ekozofija T”

Arne Naessa [Deep Ecological Movement: Arne

Naess’s “Ecosophy T”]. Soc. Ekologija. 2002 J; 11(1-2):

29-55. Croatian.

10. Markus T. Više-nego-ljudski-svijet. Dubinska

ekologija kao ekološka filozofija [More-than-Human-

World. Deep Ecology as Environmental Philosophy].

Soc. Ekologija. 2003; 12(3-4): 143-164. Croatian.

11.

Krznar T, editor. Čovjek i priroda: Prilog

određivanju odnosa [Man and Nature: Contribution to

the Determination of their Relationship]. Zagreb:

Pergamena; 2013.

12. Geiger M. Spiritualni aspekti ekofeminizma

[Spiritual Aspects of Ecofeminism]. Soc. Ekologija.

2002; 11(1-2): 15-27. Croatian.

13. Merchant C. Radical Ecology: The Search for

a Livable World. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2005.

14. Koprek I. Ekološka kriza - izazov praktičnoj

filozofiji [Ecological Crisis - Challenge for Practical

Philosophy]. Obnov. Zivot. 1991; 46(1): 28-37. Croatian.

15. Muzur A, Rinčić I. Van Rensselaer Potter i

njegovo mjesto u povijesti bioetike [Van Rensselaer

Potter and His Place in the History of Bioethics].

Zagreb: Pergamena; 2015. Croatian.

16. Clowney D, Mosto P. Earthcare: An Anthology

in Environmental Ethics. Lanham: Rowman &

Littlefield Publishers; 2009.

138

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

17. Devi TVG. Understanding Human Ecology:

Knowledge, Ethics and Politics. Abingdon: Routledge;

2019.

18. Cifrić I. Trgovina životom i proširenje bioetičke

tematike [Trade with Life and Broadenning the

Bioethical Subject Matter]. Soc. Ekologija. 1998; 7(3):

271-290. Croatian.

19. Potter VR 2nd. Bioethics: Bridge to the Future.

Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall: 1971.

20. Lee LM. A Bridge Back to the Future: Public

Health Ethics, Bioethics, and Environmental Ethics.

Am J Bioeth. 2017; 17(9):5-12. DOI:

10.1080/15265161.2017.1353164

21. Valera L. The Bioethics of Potter: A Search for

Wisdom in the Origins of Bioethics and Environmental

Ethics. Medicina y Ética 2017; 28(2): 413-430.

22. ten Have HAMJ. Global Bioethics: An

Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge; 2016.

23. Whitehouse PJ. The Rebirth of Bioethics: A

Tribute to Van Rensselaer Potter. Glob Bioeth. 2001;

14

(4):

37-45.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.1080/11287462.2001.10800813

24. ten Have HAMJ. Potter’s Notion of Bioethics.

Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2012; 22(1): 59-60. DOI:

10.1353/ken.2012.0003

25. Potter VR 2nd. Bioethics, Biology, and the

Biosphere. Hastings Cent Rep. 1999; 29 (1): 38.

26. Drengson A, Inoue Y, editors. The Deep

Ecology Movement: An Introductory Anthology.

Berkeley: North Atlantic Books; 1995.

27. Næss A. Ecology of Wisdom Writings by Arne

Naess. Berkeley: Counterpoint; 2009.

28. Sessions G. The Deep Ecology Movement: A

Review. Environ Rev. 1987; 11 (2): 105-125.

29. Krznar T. Znanje i destrukcija: Integrativna

bioetika i problemi zaštite okoliša [Knowledge and

destruction: Integrative bioethics and environmental

problems]. Zagreb: Pergamena; 2011. Croatian.

30. Miller P, Westra L, editors. Just Ecological

Integrity: The Ethics of Maintaining Planetary Life.

Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2002.

31. Diehm C. Connection to Nature, Deep

Ecology, and Conservation Social Science: Human-

Nature Bonding and Protecting the Natural World.

New York: Lexington Books; 2020.

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)

32. Potter VR 2nd. Bridging the Gap between

Medical Ethics and Environmental Ethics. Glob

Bioeth.

1993;

6(3):

161-164.

https://doi.org/10.1080/11287462.1993.10800642

33. Mandal J, Ponnambath DK, Parija SC.

Bioethics: A Brief Review. Trop Parasitol. 2017; 7(1): 5-

7. DOI: 10.4103/tp.TP_4_17

34. Mastroianni AC, Kahn JP, Kass NE, editors.

The Oxford Handbook of Public Health Ethics. New

York: Oxford University Press; 2019.

35. Gruen L, Ruddick W. Biomedical and

Environmental Ethics Alliance: Common Causes and

Grounds. J Bioeth Inq. 2009; 6(4): 457. doi:

10.1007/s11673-009-9198-6

36. Barrett DH, Ortmann LW, Dawson A, Saenz C,

Reis A, Bolan G, editors. Public Health Ethics: Cases

Spanning the Globe. Cham: Springer; 2016.

37. Mackenzie JS, Jeggo M, Daszak P, Richt JA,

editors. One Health: The Human-Animal-

Environment Interfaces in Emerging Infectious

Diseases. Cham: Springer; 2013.

38. Horton R. Offline: The Origins Story—Towards

A Deep Ecology. Lancet. 2022; 399(10320):129. DOI:

10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00001-0

39. Calistri P, Decaro N, Lorusso A. SARS-CoV-2

Pandemic: Not the First, Not the Last.

Microorganisms.

2021;

19;9(2):433.

DOI:

10.3390/microorganisms9020433

40. Alves RRN, de Albuquerque UP, editors.

Ethnozoology: Animals in Our Lives. London:

Academic Press; 2018.

41. Beever J, Whitehouse PJ. The Ecosystem of

Bioethics: Building Bridges to Public Health. Jahr.

2017; 8(2): 227-243. https://hrcak.srce.hr/193834

42. Rabinowitz PM, Pappaioanou M, Bardosh KL,

Conti L. A Planetary Vision for One Health. BMJ Glob

Health. 2018; 3(5): 1-6. DOI: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-

001137

43. Landrigan PJ, Vicini A, editors. Ethical

Challenges in Global Public Health Climate Change,

Pollution, and the Health of the Poor. Eugene:

Pickwick Publications; 2021.

Author contribution. Acquisition of data:SM, GS, AD

Administrative, technical or logistic support: SM, GS, AD

Analysis and interpretation of data: SM, GS, AD

139

SEEMEDJ 2022, Vol 6, No 1 Deep Ecology

44. Turina IS, Brkljačić M, Grgas-Bile C, Gajski D,

Racz A, Čengić T. Current Perspectives of Potter’s

Global Bioethics as a Bridge Between Clinical

(Personalized) and Public Health Ethics. Acta Clin

Croat. 2015; 54(4): 509-515.

45. Tong S, Bambrick H, Beggs PJ, Chen L, Hu Y,

Ma W, Steffen W, Tan J. Current and Future Threats

to Human Health in the Anthropocene. Environ Int.

2022;

158(2022):

1-14.

DOI:

10.1016/j.envint.2021.106892

46. Sodeke SO, Wilson WD. Integrative Bioethics

is a Bridge-builder Worth Considering to Get Desired

Results. Am J Bioet. 2017; 17(9):30-32. DOI:

10.1080/15265161.2017.1353174

47. Laasch O, Conaway RN. Principles of

Responsible Management: Glocal Sustainability,

Responsibility, and Ethics. Stamford: Cengage

Learning; 2015.

48. Pereira AG, Funtowicz S, editors. Science,

Philosophy and Sustainability: The End of the

Cartesian dream. London: Routledge; 2015.

49. Rimanoczy I. The Sustainability Mindset

Principles: A Guide to Developing a Mindset for a

Better World. New York: Routledge; 2021.

50. Miller GT, Spoolman S. Living in the

Environment: Principles, Connections, and Solutions.

17th edition. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2012.

51. Kaphle D. Genetic Engineering, Globalization

and the Future of Ecology: An Ecocritical Study of

Margaret Atwood’s The Year of the Flood. Sch. J. Arts

Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021; 3(1): 83-93. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.3126/sjah.v3i1.35377

52. Valera L. El futuro de la ecología: la sabiduría

como centro especulativo de la ética ambiental [The

Future of Ecology: Wisdom as The Speculative

Centre of Environmental Ethics]. Cuad Bioet. 2016;

27(91): 329-338. Spanish.

53. Dwyer J. How to Connect Bioethics and

Environmental Ethics: Health, Sustainability, and

Justice. Bioethics. 2009; 23(9): 497-502. DOI:

10.1111/j.1467-8519.2009.01759.x

54. Goldberg TL, Patz JA. The Need for a Global

Health Ethic. Lancet. 2015; 386(10007): 37-39. DOI:

10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60757-7

Conception and design: SM, GS, AD

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual

content: SM, GS, AD

Drafting of the article: SM, GS, AD

Final approval of the article: SM, GS, AD

Southeastern European Medical Journal, 2022; 6(1)