ANIMAL-ASSISTED THERAPY (AAT) - WHAT IS IT?

ELRI HETTEMA

Assignment submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Masters of Arts degree

(Counselling Psychology) at the University of Stellenbosch

Supervisor: Prof T.W.B. van der Westhuysen

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

2

DECLARATION

I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this assignment is my own original

work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any University for a

degree.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

Abstract

ANIMAL-ASSISTED THERAPY (AAT) - WHAT IS IT?

This study focuses on existing research into the field of animal-assisted therapy (AAT) and

attempts to provide a clear answer as to what animal-assisted therapy (AAT) is. In addition,

the limitations of current research, as well as future opportunities for research in this field and

some practical considerations for applying animal-assisted therapy are explored.

The origin of animal-assisted therapy is examined. How the present terminology has

developed in that it defines the use of animals in therapy as an adjunct to other therapeutic

techniques is discussed in contrast to previous terminology, which created the impression that

there was some form of managed process on the part of the animal. The terminology has

developed from terms such as pet therapy and pet-facilitated therapy to animal-assisted

therapy (AAT) and animal-assisted activities (AAA).

The history of animal-assisted therapy is examined in relation to the three therapy categories

of milieu therapy, physical rehabilitation and animal-assisted psychotherapy. The most

common theoretical frameworks for AAT are also discussed. In general, systems theory tends

to be the most favoured theoretical foundation for AAT.

The typical target populations of animal-assisted therapy are examined in the light of target

relationships. The six target relationships that a practitioner of animal-assisted therapy would

need to manage are identified and their merits discussed: therapist-and-patient relationship;

therapist-and-animal relationship; the staff-and-patient and staff-and-animal relationship; the

staff-and-animal therapist relationship; the animal-and-patient relationship; and the

application environment wherein these relationships are lived.

The typical research designs for AAT are also discussed within the history of AATand

successful research tends toward longitudinal studies wherein patients with similar diagnostic

profiles are all exposed to a common form of treatment. The experimental group has some

form of AAT in addition to the standard treatment whilst the control group continues with

only the standard treatment. Comparisons are made against specific measurements such as

degree of sociability and other indices. In general, the current research indicates a need for

research characterised by better controls and the application of general research principles to

supplement the abundance of anecdotal and case study reports on AAT.

In addition, the practical application of AAT is also examined in relation to training and

liability, office management and décor, animal well-being, and the necessary precautions to

safeguard patients from possible harm.

A critique of AAT is provided as well as the difficulties encountered in the practical

implementation of animal-assisted therapy. The literature reviewed for this study confirms

that animal-assisted therapy shows excellent promise, which increases when complimented

by experimental endeavour in terms of properly evaluated AAT programmes.

In terms of the future potential of AAT, the possible advantages of the implementation of

AAT programmes into schools, prisons and working environments is raised. Related

therapeutic adjuncts such as horticultural and natural therapy are also discussed. Fine (2000)

was the most up to date and encompassing source for AAT and may be a good tool to guide

future practitioners and researchers in the field of AAT.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

Abstrak

DIERE-ONDERSTEUNDE TERAPIE (DOT) -WAT IS DIT?

Hierdie studie fokus op huidige navorsing op die gebied van diere-ondersteunde terapie

(DOT) en strewe om lig te gooi op wat presies diere-ondersteunde terapie is. Daarbenewens,

word die beperkinge van huidige navorsing sowel as toekomstige geleenthede vir navorsing

op hierdie gebied. Praktiese doelwitte vir die toepassing van diere-ondersteunde terapie is

ook geidentifiseer. Die oorsprong van diere-ondersteunde terapie word ondersoek. Hoe die

huidige terminologie ontwikkel het in sover dit die gebruik van diere aangaan in terapie as

adjunk tot ander terapeutiese tegnieke word bespreek, in vergelyking met vorige terminologie

wat die indruk geskep het dat daar een of ander bestuurde proses is wat deur die dier

uitgevoer word. Die terminologie het ontwikkel van terme soos troeteldierterapie en

troeteldier-gefasiliteerde terapie tot diere-ondersteunde terapie (DOT) en diere-

ondersteunde aktiwiteite (DOA).

Die geskiedenis van diere-ondersteunde terapie word ondersoek volgens die drie

terapiekategoriee van milieuterapie, fisiese rehabilitasie en diere-ondersteunde psigoterapie.

Die mees algemene teoretiese raamwerke vir DOT word ook bespreek. Oor die algemeen, is

sisteemteorie die sigbaarste teoretiese grondslag vir DOT.

Die tipiese teikengroepe vir diere-ondersteunde terapie word ondersoek in die lig van teiken

verhoudings. Die ses teikenverhoudings wat 'n praktisyn van diere-ondersteunde terapie sou

bestuur word onderskei en hul relatiewe meriete bespreek: die terapeut/pasient-verhouding;

terapeut/dier-verhouding; personeel/pasient-verhouding; personeel/diereterapeut- verhouding;

dier/pasient- verhouding ; sowel as die toepassings omgewing waarin die verhoudings

uitgeleef word.

Die tipiese navorsingsontwerpe vir DOT word ook binne die geskiedenis van DOT bespreek.

Die mees geloofwaardige navorsing neig tot longitudinale studies waarin pasiente met

soorgelyke diagnostiese profiele almal aan 'n gemene vorm van behandeling blootgestel is.

Die eksperimentele groep kry dan een of ander vorm van DOT sowel as die standaard

behandeling terwyl die kontrole groep slegs die standaard behandeling ontvang. Vergelykings

word dan gemaak volgens spesifieke metings soos mate van sosialiteit en ander persoonlike

effektiwiteit maatstawwe. Oor die algemeen dui huidige navorsing op 'n behoefte vir

navorsing wat deur beter beheer gekenmerk word, en die toepassing van algemene

navorsingsbegrippe om as aanvulling te dien tot die oorvloed anekdotiese en gevallestudies

wat die DOT literatuur betref. Daarbenewens word die die praktiese toepassing van DOT

ondersoek met betrekking tot opleiding en verantwoording, kantoorbeheer en dekor,

dierewelsyn sowel as die nodige teenmaatreëls om pasiente teen enige negatiewe gevolge te

beskerm.

'n Kritiese ontleding van DOT word ook voorsien en die moontlike struikelblokke wat in die

praktiese implementasie van diere-ondersteunde terapie ondervind kan word. Die literatuur

wat vir hierdie studie nagegaan is, bevestig dat diere-ondersteunde terapie uitstekende

vooruitsigte toon. Sover dit die toekomstige potensiaal van DOT aangaan, word die

moontlike voordele van die implementasie van DOT-programme in skole, tronke en

werksomgewings genoem. Verwante terapeutiese byvoegings soos tuin- en natuur-terapie

word ook bespreek. Fine (2000) blyk om die mees resente en omvattende bron van DOT te

wees en mag 'n goeie hulpmiddel wees om toekomstige praktisyns en navorsers op die

gebied van DOT van 'n riglyn te voorsien.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

3

DEDICATIONS

Why did early man, when he expressed himself in rock engravings, choose animals as emblems of

his aspirations? Why have highly cultured races like the Egyptians and Assyrians used animals as

symbols for their Gods ... ? Why are we so deeply moved by tragedies involving our pets? Why are

the first toys given to our children representatives of animals? ...

Do we need more proof that we need animals more than they need us - that they can give us

something which we cannot give ourselves?

Joy Adamson - Pippa's Challenge

I would like to thank my husband Sean for all his support and my promoter Professor van der

Westhuysen for his patience.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

TABLE OF CONTENTS

4

Page

1. INTRODUCTION, MOTIVATION FOR AND OBJECTIVES OF ASSIGNMENT

i.i. Introduction

5

1.2. Motivation for Assignment

5

1.3. Broad Objectives of Assignment

6

1.4. Delineation of Assignment

6

1.5. Terminology

7

1.6. Conclusion

8

2. ORIGIN OF ANIMAL-ASSISTED THERAPY (AAT)

8

3. OVERVIEW OF ANIMAL-ASSISTED THERAPY

3.l. Introduction

10

3.2. Therapy categories and disciplines associated with AA T

11

3.3. Most common theoretical frameworks associated with AAT

15

3.4. Typical target populations

16

3.5. Typical research and application designs

19

3.6. A developmental perspective on AAT

22

3.7. Related aspects

23

3.8. Critique of animal-assisted therapies

25

4. FUTURE POTENTIAL OF ANIMAL-ASSISTED THERAPY

26

5. REFERENCE LIST

28

7. RESOURCES

29

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

5

1. INTRODUCTION, MOTIVATION FOR AND OBJECTIVES OF ASSIGNMENT

1.1

Introduction

Levinson (1969, quoted in Brickel, 1986) highlighted the interconnectedness and co-

dependence of animals and humans over the ages. Humans have depended on

animals for food and protection from the elements. We have used animal hides for

clothing and shelters. Animals have also been used as a means of transport and as

extra muscle in labour such as ploughing fields. In return animals have had their

basic physical needs for food and shelter taken care of by humans. On a social and

emotional level this co-dependence has ranged from shared companionship between

human and animal such as the shepherd and his dog, .

The formal exploration of these human-animal interactions is an age-old endeavour

with advancing popular acceptance in the last 20 years, especially in terms of the

therapeutic application implications of these human-animal interactions. Available

resources vary in their knowledge contribution from the highly descriptive, almost

evangelistic studies of the converted to highly critical attacks on what is often

perceived as an emotionally laden area of study.

This assignment will strive to provide an answer as to precisely what animal-

assisted therapy (AAT) is.

1.2

Motivation for Assignment

In the process of exploring the field of animal-assisted therapy (AA T) it becomes

clear that there is a preponderance of hypothesis generating research. This research

is inclined to generate more empirical questions than confirming any specific

hypotheses. Mallon (1992) confirms that practitioners of animal-facilitated therapy

tend to report high levels of success based on case reports. These studies generally

report on the practical application of animal-assisted therapy within environments

such as prisons, nursing homes, homes for the disabled and in child care settings.

These practitioners according to Mallon (1992) typically do not focus sufficient

attention on scientific rigour in the application of AA T. According to Voelker

(1995, quoted in Fine, 2000) it is for this reason often difficult to obtain outcome

data in terms of animal-assisted therapy.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

6

The motivation for this assignment is rooted in providing an integration of current

research and direct experience to clarify what exactly animal-assisted therapy is,

what it's limitations are and to highlight current research outcomes and future

research opportunities. Considerations to applying animal-assisted therapy will also

receive attention.

1.3

Broad Objectives of Assignment

The objectives of this assignment can be formulated as:

To clarify what animal-assisted therapy is;

To identify relevant considerations for the application of AAT as a therapeutic

adjunct;

To highlight the future potential of animal-assisted therapy;

and

To provide a summary of current animal-assisted therapy research.

1.4

Delineation of Assignment

To achieve the objectives in section 1.3 the assignment will examine the following

aspects of animal-assisted therapy:

The origin of animal-assisted therapy;

An overview of animal-assisted therapy;

Practical examples of, and considerations for, the systematic application of

animal-assisted therapy;

Research foundations of animal-assisted therapy; and

The future potential of animal-assisted therapy.

Odendaal (1992) maintains that there are primarily two motivations for applied

human-animal interaction. The first is to elicit emotional advantages and the second

is the utility value to humankind. The latter includes working animals, security

animals and sport and recreation. This study, however, will focus on the emotional

and physical value gained by human-animal interactions within the above fields. In

other words, the use of human-animal interactions that focuses on the therapeutic, as

opposed to utility, outcomes. The professions involved with the emotional value of

AAT include psychologists, social workers, educators, physiotherapists and

occupational therapists.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

7

According to Brickel (1986) the field of animal-assisted therapy encompasses three

therapeutic categories: milieu therapy, physical rehabilitation and animal-facilitated

psychotherapy. This assignment is aimed at all three of the above categories.

1.5

Terminology

An abundance of AAT literature exists, as is apparent from the report by Draper,

Gerber and Layng (1990) indicating over a thousand references to animal-assisted

therapy in the current literature base. Furthermore they have indicated a diversified

use of terminology in AAT, although they ascribe the highest prevalence to the

following terms in the literature: Pet therapy, Pet Assisted Therapy and Pet

Facilitated Therapy. Draper et al. (1990) also point out that this trend to diversified

terminology confuses the field of study.

Mallon (1992) confirms a redefinition of all of the above to the more inclusive term

of animal-facilitated therapy. The use of the word "animal" is more encompassing

than "pet" as some therapies use animals that would not generally be construed as

pets. Furthermore the use of the word "facilitated" is more descriptive of the general

approach within most of the successful therapies described in the literature.

Fine (2000) chooses the term animal-assisted therapy, which seems to solve the

problem that animal-facilitated appears to denote a form of managed process on the

part of the animal. Animal-facilitated therapy could be interpreted as implying that

the animal facilitates the therapeutic process, denying the fact that it actually is

therapist that facilitates the process. Animal-assisted therapy is clearer in defining

the use of animals in therapy as an adjunct to other therapeutic techniques and

distinguishes between the use of an animal as an assistance to therapy and an

animal-directed form of therapy. The term animal-assisted therapy (AAT) will be

used as the standard for the purpose of this assignment.

Animal-assisted therapy as such is not a therapy modality in and of itself but rather a

particular therapeutic adjunct, which can be quite broadly applied.

According to Brickel (1986), animal-assisted therapy " ...refers to integrating

animals into client-directed therapeutic activities" (p 309).

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

8

1.6

Conclusion

Building on the above, the subsequent chapters will examine the origin and history

of animal-assisted therapy, the disciplines, theoretical frameworks and target

populations typically associated with animal-assisted therapy and the various

application designs for animal-assisted therapies. Considerations for AA T practice

will also be examined.

The research foundations, critique and the future potential of AA T will conclude the

assignment.

2.

THE ORIGIN OF ANIMAL-ASSISTED THERAPY

Odendaal (1989) provides an excellent perspective on the origin of animal-assisted

therapy. In this article he describes the main contributors according to the time of

their impact on the field of study and their goals with animal-assisted therapy. All of

those mentioned report a high degree of success and are generally acclaimed as

pioneers in the field.

In summary Odendaal (1989) describes the origin as follows: The earliest recorded

instance of the formal use of animals in therapy was by Gheel in the 9th Century in

Belgium, whose form of therapy was known as "therapy naturelle". This approach

included, apart from animals, the use of other natural resources in therapy. Another

early pioneer was William Tuke (circa ] 792) of the York Retreat Hospital in

England where the therapeutic goal with the use of animals was to facilitate the

development of self-control for emotionally disturbed people by stimulating

responsibility. Odendaal (1992) also mentions the Bethal Institute in Germany,

which was established in 1867 and still uses animals today as an integral part of its

therapeutic programmes.

Among the more recent contributions Odendaal (1989) highlights the work of Boris

Levinson in the 1960' s, especially with children. Some of Levinson's goals with

animal-assisted therapy were based in the creation of a safe relationship between

children and animals, wherein the child is in the leading position. He also used

animals to help break down psychological barriers. According to Levinson the

interaction between child and animal provides safe opportunities to discuss the

behaviour of the child directly or to discuss the behaviour of the animal as an

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

9

analogy of other relationships the child may be in. In this way animals assisted in

the therapeutic process.

The ]970's, (Odendaal 1989), yielded the husband and wife team of Prof Samuel

Corson and Dr Elizabeth Corson of the Ohio University Hospital in the United

States. They used animals in a medical hospital setting and coined the terminology

"pet facilitated psychotherapy". Their goals were focused on improving non-verbal

communication, stimulating self-confidence, the development of a reality orientation

and to decrease dependence on psychotropic drugs.

Odendaal (1989) discusses another six international practitioners who contributed to

AAT between 1970-1989, the most noteworthy being Dr Aaron Katcher from the

University of Pennsylvania in the early 1980's. Katcher was of the opinion that

animal-facilitated therapies have the following benefits: relief from loneliness;

fulfillment of the need to nurture; provision of a stimulus to activity; provision of an

object for touch and safe attachment; and fulfillment of the need to feel secure.

One of the most highly developed centres for animal-assisted therapy is the Green

Chimneys Farm (http://pcnet.coml-gchimney/story).This facility was started in

1947 on a farm close to New York City and programmes range from shelter care,

residential treatment, adult services and group homes. Green Chimneys have a

Residential Treatment Center, Residential Treatment Facility, Special Education

Day School, Farm & Wildlife Conservation Center, Arbor House and an Outdoor

Education Center. Green Chimneys utilizes Animal-Assisted Activities (milieu

therapy), Animal-Assisted Therapy and Equine-Assisted Psychotherapy.

They have recently completed a $12 million dollar campus, which offers

certification and internship training in animal-assisted therapy across a broad field.

Beck (Fine, 2000) quotes a survey by Walter-Toews in 1993 of 150 selected U.S.

and 74 Canadian humane societies. The findings indicated that 46% of the U.S. and

66% of the Canadian programmes ran animal-assisted programs.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

10

Referring to South Africa Odendaal (1989) mentions two noteworthy projects in the

field of animal-assisted therapy. At Witrand Care and Rehabilitation Centre for the

mentally retarded in Potchefstroom, a study was conducted using cage birds to help

patients in the normalising process, establish recognition of personal individuality

and to monitor any general improvements in patient behaviour, with reported

positive results. At the Avril Elizabeth Home for the mentally and physically

disabled in Germiston, animal-assisted therapy formed part of the general

therapeutic programme and was used in conjunction with other therapeutic

approaches. The home had their own animal therapy unit with animals ranging from

horses to ducks. The programme was closed down around 1995 due to complaints

from neighbours and staffing difficulties.

Pollsmoor prison in Cape Town, South Africa also has a programme (Huisgenoot, 7

December 2000) wherein selected prisoners are involved in breeding and raising

parakeets for re-sale into the community. According to Wikus Gresse, a director at

the Pollsmoor Prison, the prisoners involved in the programme are less aggressive,

more responsible and have also learned some small business skills as a result of the

programme.

An overview of animal-assisted therapy will be addressed in the next chapter.

3.

OVERVIEW OF ANIMAL-ASSISTED THERAPY

3.1.

Introduction

Although still a relatively new area of practice, animal-assisted therapy literature has

crystallized to the point where the therapy categories, theoretical frameworks, target

populations and research foundations can be broadly specified. This chapter will

encompass:

3.2 The therapy categories and theoretical frameworks associated with animal-

assisted therapy;

3.3 The typical target populations for animal-assisted therapy;

3.4 The typical research and application designs of animal-assisted therapy;

3.5 A critique of animal-assisted therapy;

3.6 A developmental perspective on AAT; and

3.7 Related aspects.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

11

3.2

Therapy categories and disciplines associated with AAT

Three types of animal-assisted therapy, namely: milieu therapy, physical rehabilitation

and animal-assisted psychotherapy are generally accepted delineations within the study

area of animal-assisted therapy (Brickel, 1986).

3.2.1

Milieu Therapy

According to Brickel (1986) milieu therapy quite simply involves introducing an animal

into an environment where there will be contact between animal and patient or vice

versa. This is the most commonly used form of animal-assisted therapy. The implicit

hypothesis is that human-animal contact interactions are intrinsically therapeutic. This is

also the simplest intervention form and the most broadly applicable type of human-

animal intervention to introduce. It is also the form best suited for lay therapists.

Corson et al. (1977, in Fine, 2000) exposed patients who had not responded to any

traditional therapies to a pet visitation programme. By comparing the previously

ineffective therapies with the effect of animal-assisted therapy the patients served as

their own controls. The patients continued to receive the traditional therapies at the

same time that the visitation programme was introduced. The milieu therapy included

the following elements. Animals were introduced into the care centre in kennels, in the

wards and during bedside visits. Primarily dogs were utilized.

Analysis of the recorded sessions between patient, animal and handler indicated that

patients became less withdrawn and responded to a therapist's questions sooner and

more comprehensively.

Subjectively the patients appeared happier. This immediately visible impact of milieu

therapy coupled with the resourcing advantage of using trained volunteers from the

general public, has allowed this form of AAT to flourish worldwide. A further

advantage of milieu therapy lies in the institution not having an animal care

responsibility in addition to their human care responsibility. The care of animals places

an additional burden on staff, which can lead to the failure of AAT programmes. A

common concern is the spread of zoonotic diseases. By involving a veterinarian in the

management ofthe programme the threat of zoonotic diseases may be controlled.

3.2.2

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

12

Physical rehabilitation

Physical rehabilitation programmes (Brickel, 1986) typically involve patients in care-

giving activities such as grooming, cleaning, feeding or walking the animals as well as

the cleaning and/or maintenance of cages, aquariums and stables. This category may

often be a peripheral benefit of milieu therapy. The health value is deduced from the

gross and fine muscle movements required during care-giving activities as well as the

psychological value of the responsibility of caring for a particular animal. The

interaction with an animal may also serve as a focus for sounds and speech in that

patients may be encouraged to emulate animal sounds within the context of speech

therapy or function as a topic for conversation. This may include animal sounds such as

barking or attempts to describe animal antics or characteristics. An extension of AAT in

terms of physical rehabilitation is the use of service animals for people with disabilities

primarily in the home setting but also in the form of guide dogs in work and other social

settings.

Beck (in Fine, 2000) highlights some interesting research by Allen and Blascovich in

the area of service animals for the disabled. The study included a group of patients with

ambulatory motor impairment examining measures such as locus of control, self-esteem

and community integration in relation to the use of a service dog. A "waiting list

control" approach was used wherein patients were their own control group over a period

of time. Patients either received a service dog 1 month or 12 months after the study

began. The expected experimental variable was the time that a subject was exposed to a

service dog in relation to the measures provided by the questionnaires used.

The monthly mail back questionnaires to the entire group were used to evaluate locus of

control, self-esteem and community integration in the control group (those who had not

yet received a service dog) and the experimental group (those who had already had a

service dog for a measurable period of time). The results indicated that the experimental

group (patients who received their service dogs 1 month after the study began) faired far

better than the control group (patients who received their service dogs up to 12 months

after the service began).

Based on the self-assessment of the participants those patients with a longer exposure

service dogs scored proportionally better for self-esteem, internal locus of control and

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

13

community integration. This group required fewer services, which resulted in savings of

more than R400,OOO per dog.

Thus physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists may find animal-

assisted therapy in this form able to contribute to some of their specific outcomes

(Brickel, 1986), such as improved self-esteem, internal locus of control and community

integration.

Other forms of physical rehabilitation programmes include specialised programmes

such as equestrian programmes. It is important, according to Beck (in Fine, 2000), that

one distinguishes between equine-assisted psychotherapy and hippotherapy. Equine-

assisted psychotherapy activities, such as riding and vaulting, are designed to co-

ordinate with the overall psychotherapeutic treatment of the individual. Typical

therapeutic goals according to Beck (in Fine, 2000) are improving self-confidence,

social competence and other variables related to quality of life. The goal is not to learn

to ride per se.

Hippotherapy on the other hand is applied by trained physical and occupational

therapists to improve patients neuro-motor functioning using horses. An additional

advantage of these forms of therapy is the reported enjoyment derived by patients whilst

receiving treatment. Thus the use of animals in physical and mental rehabilitation is best

suited for qualified rehabilitation therapists across a broad field ranging from

physiotherapists and occupational therapists to speech therapists.

3.2.3

Animal-assisted psychotherapy

Animal-assisted psychotherapy (Brickel, 1986) refers to the use of an animal in goal

directed therapeutic programmes focused on psychological or social outcomes. Goal

directed therapy in this case refers to there being specific goals identified by the

therapist for the animal-assisted session. An example could be to improve the self-

confidence of the patient. It is the ability of animals to elicit responses from people that

the therapist can capitalise upon that is especially valuable according to Brickel (1986).

In this instance, the typical therapists would include social workers, psychologists and

accredited counselors.

Odendaal (1992) links the following psychosocial outcomes or goals to animal-assisted

psychotherapy: life satisfaction, happiness, quality of life, improved self-image/self-

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

14

acceptance, self-confidence and improved social functioning/communication skills.

Odendaal identifies quality of life as the most significant outcome of animal-assisted

psychotherapy based on his review of research in this area of study.

An example of animal-assisted psychotherapy is presented in the qualitative research by

Kogan, Granger, Fitchett, Helmer and Young (1999). Two male participants, labelled as

emotionally disturbed by school professionals, took part in this study. Kogan et al.

(1999) specified therapeutic goals and the evaluation thereof based on the participants'

history of diagnoses and treatment. Participant A was evaluated according to the

development of appropriate social skills among peers or adults and a decreased level of

distractibility or attention deficit. Participant B was evaluated based on the development

of age appropriate behaviours, social skills and an increased sense of personal control

and power. Each participant was exposed to weekly AAT sessions of 45-60 minutes.

These sessions were comprised of a rapport-building and then an animal

training/presentation planning time. The participants needed to train the animal they

were working with to perform certain actions. At the end of the process each participant

would demonstrate the actions or tricks they had trained their animal to perform and

also present their experience of the entire process. The rapport-building period provided

time for the animal-handler to talk through relevant topics as initiated by the participant

or raised by the school professional in consultation with the animal handler (Kogan et

al.,1999). The animal training and presentation planning time was very goal-focused in

terms of learning how to command the dog to perform certain routine actions such as

sit, stay and fetch. The final goal was a planned execution of a certain sequence of

actions by the dog combined with a presentation of what the experience meant for each

participant.

The data sources for this study by Kogan et al. (1999) included the ADD-H

Comprehensive Teacher Rating Scale (ACTeRS), observations of sessions by education

professionals, multi-rater coding of 3 video sessions staggered from initial, mid-point

and final session, monitoring of Individual Education Plans (IEP) and post-intervention

interviews with the participants. The findings reported both participants as having

improved on the majority of their goals after the AAT intervention. As such, Kogan et

al. (1999), concluded that AAT is a highly effective supplementary tool for

psychotherapists and special education teachers.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

15

3.3

Most common AAT theoretical frameworks

Prochaska (1984) provides a clear defmition of a system as a set of elements or

relationship interaction points that have some form of a consistent relationship.

According to Prochaska (1984), the organization of systems suggest that when

consistent relationship patterns form between individual interaction points in the

system, a different entity is produced which is greater than the sum of the parts of the

original system.

According to Triebenbacher (in Fine, 2000), systems theory appears to offer an

appropriate theoretical foundation on which therapists, psychologists, social workers

and other mental health professionals can build on in the process of including AAT in

their treatment plans. Odendaal (2000) appears to support this view indicating that

intraspecies social systems are not necessarily closed systems but can be expanded to be

interspecies social systems in nature. Thus, with AAT the companion animal being used

can be viewed as a vital member of the human family or social system. As Odendaal

(2000) emphasizes, AAT is about achieving a mutually beneficial interaction between

people and animals characterized by equilibrium and mutuality.

According to Prochaska (1984), the interactional or relationship relevance of systems

resides in the propensity of systems to form boundaries between different systems and

their subsystems. These boundaries guide the relationship patterns within systems and

reflect the rules of interaction for systems.

The interaction with animals as part of an interspecies system results in the formation of

patterns and boundaries that may serve the following therapeutic functions according to

Fine (2000):

They provide a social lubricant within the therapy setting;

They assist with rapport building;

They act as a catalyst for emotions; and

They provide opportunities for role-modelling.

The nature of these boundaries reflects the character of the relationship interactions

between different subsystems within a system and between different systems.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

16

3.4

Typical target populations of AA T

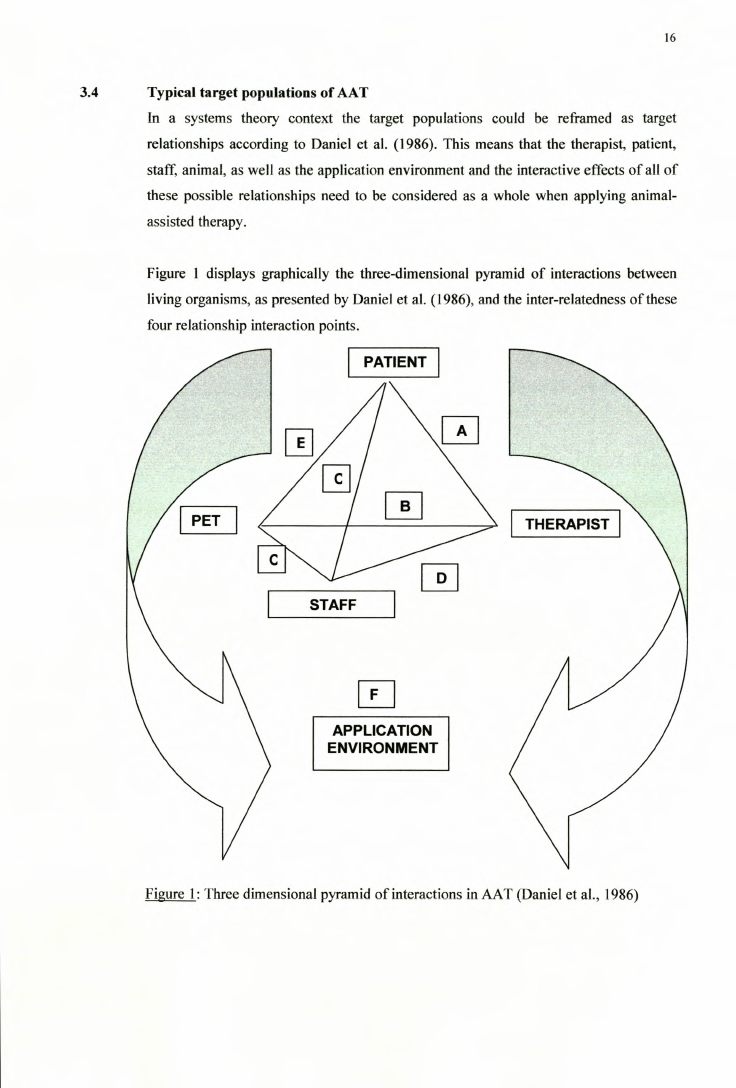

In a systems theory context the target populations could be reframed as target

relationships according to Daniel et al. (1986). This means that the therapist, patient,

staff, animal, as well as the application environment and the interactive effects of all of

these possible relationships need to be considered as a whole when applying animal-

assisted therapy.

Figure 1 displays graphically the three-dimensional pyramid of interactions between

living organisms, as presented by Daniel et al. (1986), and the inter-relatedness of these

four relationship interaction points.

PATIENT

STAFF

THERAPIST

APPLICATION

ENVIRONMENT

Figure 1: Three dimensional pyramid of interactions in AAT (Daniel et al., 1986)

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

17

The above model is based upon a practical implementation study of an AA T programme

at the Hudson View Nursing Home in New York. Based on this Daniel et al. (1986)

distinguish the six target relationships that a practitioner of animal-assisted therapy

would need to manage, namely A: - The therapist-and-patient relationship; B: - The

therapist-and-animal relationship; C: - The staff-and-patient and staff-and-animal

relationship; D: - The staff-and-animal therapist relationship; E: - The animal-and-

patient relationship; and F: - The application environment wherein these relationships

are lived.

The therapist-and-patient relationship is best developed, according to Daniel et al.

(1986), by therapists with formal training and experience in assisting the patient

population in question. In addition to this formal training, the target relationship also

requires potential therapists to have professional or paraprofessional experience in the

appropriate application environments prior to the addition of an animal as "co-therapist"

into the relationship network. In other words should the application environment be a

prison it would be more effective should the therapist already have worked in a similar

environment prior to the introduction of AAT as a therapeutic adjunct. In this way the

therapist will only have to deal with the impact of AAT and not their own adjustment to

this particular application environment.

According to Hart (in Fine, 2000) animal-assisted therapies predominate in institutional

settings such as care centres for the elderly; the physically and mentally disabled,

children and youth, prisons and rehabilitation centres.

The therapist-and-animal relationship entails the interaction between the therapist and

the "animal co-facilitator". According to Daniel et al. (1986) it is imperative that the

potential therapist must have adequate knowledge and skills regarding applied animal

behaviour and the appropriate animal training required. The type and breed of animal

used is critical. The personality and behaviour of a particular type or breed of animal

needs to suit the planned AAT application. Organisations such as Therapy Dogs

International (tdi@gti.net) provide certification programmes for both the

handler/therapist and the relevant animal. This typically entails ensuring that the

animals and handlers are suitably trained for AAT applications. Elements here include

the animals being trained in certain commands to make them more manageable,

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

18

socialising the animals to be comfortable in settings with many people and a high level

of activity. In terms of the handlers or therapists the training typically includes animal

behaviour and control as well as care of the animal.

In any environment that includes care staff the staff-patient and staff-animal relationship

determines the success the therapist, introducing the animal-assisted therapy, will

achieve. The primary focus according to Daniel et al. (1986) is on the real impact an

AAT programme has on the total work environment of the care staff and the critical

reinforcement the care staff need to provide for the AAT programme to succeed.

The staff-and-animal therapist relationship determines the staff-patient and staff-animal

relationship. The staff-and-animal therapist relationship requires of the animal therapist

to create a relationship of trust and openness with the care staff (Daniel et aL, 1986).

This entails the development of a sensitivity and responsiveness to care staff needs and

concerns so as to be able to generate the solutions required for addressing the staff-

patient and staff-animal relationship.

Nebbe (1991) also emphasises as a necessity the need to involve the administration staff

of the institution in the design and motivation for an animal-assisted therapy

programme.

The therapist will therefore need to invest time in a careful monitoring of staff feelings

and concerns and the facilitation ofa constant dialogue with care staff with the ultimate

aim of the care staff being partners in the intervention with patients. According to

Cecilia Tweedy, the Hudson View Social Services Director, "The outcome was less

work for each department and more alert patients" during the implementation of this

model at Hudson View Nursing Home (Daniel et al., 1986).

Using the Avril Elizabeth Home once again as an example, their programme ran into

trouble as staff were often additionally loaded with animal care work, which they did

not have the time or inclination for. Staff at the Avri! Elizabeth Home also resented

having to deal with the additional stress of residents mourning animals that had died. It

is of critical importance that should one have a residential programme of this kind, that

interested and trained animal care staff are clearly identified. Clearly this type of

programme requires its own dedicated staff. Furthermore an AAT programme should, if

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

19

anything, have as its aim to lighten the workload of existing care staff if it is to survive.

(This information was sourced from personal discussions with a current staff member at

the Avril Elizabeth Home who was involved with their AAT programme).

The animal-and-patient relationship is the primary relationship of animal-assisted

therapies. This relationship cannot thrive without all the preceding relationships being

well established. The preceding relationships describe the therapist's necessary

preparation. The best implementation route to an effective relationship here is viewed

as an internship with an experienced animal-assisted therapy professional in the

required application environment. The best results would of course be achieved with the

addition of direct support from another therapist with experience in applying animal-

assisted therapy. Green Chimneys Farm NY offers these types of internships for

therapists and handlers.

Daniel et al. (1986) also highlights the importance of identifying patients who have an

affinity or are at least not averse to animals. In all cases some patients will not be suited

to an AAT intervention due to allergies, phobias or a dislike of animals. This choice to

participation by patients should be respected.

3.5

3.5.1

Typical research and application designs

Typical research designs

Marr et al. (2000) highlight the need for research characterized by better controls and

the application of general research principles to supplement the abundance of anecdotal

and case study reports on AAT. A study conducted by Marr et al. with sixty-nine male

and female psychiatric inpatients is a good example of this type of research. In their

study they randomly assigned patients to either a psychiatric rehabilitation group that

included AAT or a control group with conventional psychiatric treatment. In this way

the intervention was the same for both groups with the exception of AAT being an

additional factor for the experimental group. In terms of the design there were no

significant demographic differences between the control and the experimental groups.

The study time frame was in both cases four weeks. The therapy goal for both groups

was to build a foundation to aid in the development and maintenance of coping skills to

resist alcohol and drugs or to initiate a recovery process if usage had already started.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

20

The Social Behaviour Scale by Perelle and Granville was used to obtain baseline

measures for each patient on the first day of therapy. The instrument was then scored

daily near the end of each of the sessions for each patient with cumulative weekly

scores. The same rater was used to score both groups independent of the individual

conducting the groups in order to enhance interrater reliability. The rater was however

not blind to the experimental condition but was blind to the design and intent of the

study.

The animals used with the experimental group included dogs, rabbits, ferrets and guinea

pigs. The animals remained with the group for each full session rotating between

patients. Patients were allowed to observe the animals or interact with the animals as

they chose as long as they did not disrupt the group in the process. All the animals met

health and temperament/obedience standards. An AAT technician always accompanied

the animals.

The results of this study by Marr et al. (2000) were significant. The nine questions of

the Social Behaviour Scale were analysed separately. The AAT group of patients

interacted more with other patients (F(l,35) = 5.7, p=0.022). They also socialized more

and took more pleasure in their activities (F(l,35) = 5.5, p=0.025). These positive

behaviours are generally accepted to improve the effectiveness of therapy (Marr et al.,

2000).

The study by Marr et al. (2000) indicated that AAT probably promotes prosocial

behaviour simply by the animals being present. This design did not actively include the

animals in the therapeutic activity and yet it proved the probable value of animals as an

adjunct to therapy.

Marr et al. (2000) point out that research in the field of AAT tends to achieve better

results if a thorough patient history in terms of previous experience with animals and

pets is examined to identity those patient groups which may benefit the most from

AAT. The data in the Marr et al. (2000) study also points to the importance of tracking

the response to treatment over a few weeks and of using analytical tools that allow for

repeated measures.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

21

3.5.2

Typical application designs

In terms of the typical application designs for animal-assisted therapy, Gammonley and

Yates (1991) distinguish between the use of animals with formal therapeutic goals in

mind or the more informal use of animals as entertainment value. In both of these

applications the animals may either form part of a resident or a visitation programme.

Resident animal programmes entail the animals living on the premises where the

patients are. Visitation programmes, on the other hand, entail the animals being brought

to the premises at certain times for specified visits.

According to Gammonley and Yates (1991), the most common form of animal

intervention currently found are informal animal visitation programmes with a positive

diversionary or entertainment goal in mind. This type of programme is also known as

animal-assisted activity (AM).

On the other hand animal-assisted therapy (AA T) is viewed as an applied science using

animals to assist in dealing with a human problem. It entails using animals as an adjunct

to other therapies. This type of programme is more formally structured and can entail

the animals being part of a resident or visitation programme.

Gammonley and Yates (1991) further distinguish animal-assisted therapy from animal-

assisted activity by affirming animal-assisted therapy as being goal-oriented with

defined assessment and evaluation procedures as is the case for any therapeutic

intervention. The above can be achieved in either a residence or visitation programme

structure.

In terms of the typical application environments for animal-assisted therapy Hart (in

Fine, 2000) differentiates between institutional settings (prisons, care centres for the

elderly, for children and the physically and emotionally disturbed) and private practice.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

22

3.6

A developmental perspective on AAT

Fine (2000) outlines some of the possible development goals and treatment purposes of

AAT using Erik:Erikson's stages of development as a framework.

In terms of children the developmental goals are primarily focused around the need to

feel loved and to develop a sense of industry. On an AAT level, animals can assist the

clinician in promoting unconditional acceptance. Children feel accepted by the

unfettered love that animals exude and a sense of industry and competence can quite

easily be built into the application design in the form of care and grooming activities for

animals.

For adolescents the primary development challenge according to Erikson is to develop a

sense of identity (Messer & Millar, 1999). There is a strong need for affiliation and

social acceptance. The presence of an animal may assist in putting the teenager at ease

during therapy, which in tum may facilitate in bringing down barriers to the interaction

more easily. Fine (2000) indicates that pet ownership may be especially beneficial for

teens experiencing social isolation, Animals respond to people in a way that makes the

person feel significant.

For young adults the need to recognize that they can also take care of others could be a

focus point (Fine, 2000). In this case animals may be used as metaphors for discussing

generativity versus self-absorption. It is not uncommon for therapists to recommend that

a young couple have a pet as a trial to considering children, while animals also serve as

valuable metaphors regarding child-rearing practices (Fine, 2000),

In terms of the application of AAT with elderly clients Fine (2000) argues that should

the elderly person have had previous relationships with animals, the presence of an

animal would be inclined to encourage positive reminiscing in terms of past life events.

These animal-related memories also make it easier to identify major life milestones for

the patient. Ownership of a pet may have specific value in allowing an elderly person to

feel needed again (Fine, 2000).

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

23

3.7

Related aspects

A number of related aspects need to be considered in the practical application of AAT.

They are training and liability, office management and décor, animal well-being, and

the necessary precautions to safeguard patients from possible harm.

3.7.1

Training and liability

Training and liability is the first aspect that clinicians considering AAT should address.

According to Hines and Frederickson (in Fine, 2000) training and liability needs to be

viewed in the context of the safety and the welfare of both the patient and the animal.

Clinicians need to be aware of best practice procedures to ensure quality AAT as well as

safety for all parties.

The typical training programme for potential AAT clinicians should, according to Hine

and Frederickson (in Fine, 2000), incorporate the following elements:

Awareness of health issues;

Skill aptitude of specific animals; and

Strategies to incorporate the animals with clients III a specific therapeutic

modality.

The Delta Society's Pet Partners Programme (Fine, 2000) provides seminars and

workshops to keep practitioners up to date on the latest developments in this field. The

Human Animal Interaction Study Group of South Africa fulfills a research and

continuous education function in terms of AAT in South Africa (Odendaal, 1992).

3.7.2

Office management and décor

This is quite a simple issue but has a high impact according to Fine (2000). Office

dimensions, layout, and décor should suit the animal(s) being used in terms of the type

of materials used, space and accessibility. The way the office is designed should also

create the desired therapy atmosphere, be clean and hygienic and cater for the animals

needs for fresh water at any time of the day. All cages and litter should be regularly

cleaned and spilt food cleared.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

24

3.7.3

Animal well-being

The third consideration identified by Fine (2000) is the welfare of the animal(s).

Animals used within the context of any type of therapy need to be safe from any abuse

or danger from any client at all times. Fine (2000) also emphasizes the importance of

the therapist managing the stress level of the animal(s) being used. This can be achieved

by ensuring that the animal has some quiet relaxation time during the course of every

day and there should be a refuge in the office or practice to which the animal can retreat

when stressed or fatigued. Patients, especially children, need to be educated to respect

this need for retreat by the animal.

Considering animal well-being, Hubrecht and Turner (in Fine, 2000) stipulate that

therapy animals should be free from pain, injury or disease. This requires therapists to

maintain good health procedures for all animals being utilized for AAT. This includes

being up to date on all inoculations and the animal visually appearing to be in good

health. The animal should be clean and well groomed. All animals should be under the

supervision of a veterinarian who is aware of the animal's AAT role. The schedule to

which an animal can work as it ages also needs to be curtailed.

3.7.4

Precautions to safeguard AAT patients

The fourth consideration in applying AAT, according to Fine (2000) are the precautions

necessary for clients. Identifying which animal(s) will serve the best purpose with

specific client groups needs to be carefully considered. Wishon (in Fine, 2000) points

out that one of the problems often underestimated is the potential for the transfer of

pathogens, which can lead to zoonotic diseases. Zoonotic diseases are diseases that can

be transferred from animals to humans. Careful health management of the animals can

minimize this risk. Hines and Frederikson (in Fine, 2000) do, however, note that data

related to the transmission of zoonotic diseases in AAT programmes has been minimal.

In addition to the potential health risk to clients in terms of the transmission of

pathogens, it is also important for the AAT therapist to be aware of any client fears in

terms of animals in general or toward specific animal species. Allergies to any animals

should also be identified prior to commencing with AAT.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

25

3.7.5

General concerns

Fine (2000) also highlights some more general concerns, which need to be addressed by

the AAT therapist. Illness and/or death of a loved AAT animal may need to be

explained to an attached client. This needs to be carefully handled. An additional

concern may be how to introduce any new animals into the therapeutic relationship. It is

recommended to plan a staggered exposure of an animal to the therapeutic context so as

to allow the young or new animal to adjust to this role.

3.8

Critique of animal-facilitated therapies

Draper et al. (1990) confirm that available research tends toward not placing sufficient

emphasis on the role the therapist fulfills regarding the success or failure of an animal-

assisted therapy intervention. The variables that require further exploration are the

personal attributes of the therapist, the professional expertise of the therapist and the

type of therapy being applied.

Brickel (1986) indicates that the literature confirms that animal-assisted therapy shows

excellent promise; which increases when complimented by experimental endeavour in

terms of properly evaluated AAT programmes.

Any AAT programme should, according to Mallon (1992), should be able to account for

benefits linked more closely to the novelty factor surrounding the introduction of

animals to a therapeutic setting. Researchers need to test for changes in response to

animals over time. Mallon (1992) also identifies the need for AAT literature to broaden

reports of AAT success beyond the enjoyment of patients to prove the therapeutic value

of AAT. AAT has developed around pictures of cute animals and the smiling faces of

patients. What is needed is a greater emphasis on well-planned and evaluated

therapeutic studies on the benefits of AAT.

For AAT to gain general acceptance in the scientific community, research results are

required indicating whether or not the immediate emotional response to an animal

during therapy translates into lasting therapeutic change.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

26

Mallon (1992) also highlights the need for more sophisticated research methods within

the area of AAT. The use of appropriate controls to produce clear, consistent evidence is

required. AAT researchers also need to increase an explicit skepticism, realizing that a

possible hypothesis that animals have no effect on therapeutic goals is possible.

According to Beck and Katcher (in Mallon, 1992) there is a need for AAT researchers

to frame their research from the perspective of whether animals have a therapeutic

effect rather than an orientation of how to prove that animals have a therapeutic effect.

There appears to be a tendency to research from the assumption that animals do have a

therapeutic effect and all that is necessary is to prove this effect.

Mallon (1992) also identifies the need for more concrete assessments of financial and

risk control issues surrounding the implementation of AAT programmes.

In general the critique of AAT centers around a degree of over-enthusiasm by AAT

supporters to the extent that it may at time frustrate the objective evaluation of AAT as a

credible therapeutic adjunct.

4.

FUTURE POTENTIAL OF AAT

The proactive application of animal-assisted therapy in the future could be based upon a

hypothesis that the benefits of animal-assisted therapy with populations such as the

disabled, the elderly and the emotionally disabled can also be transferred to populations

of school children, prisoners and working adults (Moneymaker & Strimple, 1991).

Our school and work environments tend to be sterile. Both are environments wherein

the importance of a positive experience is directly related to individual growth and

performance. The introduction of animal-assisted activities and or therapies may assist

school children and employees to reach their full potential. To identify specific

methodologies to integrate the benefits of animal-assisted therapy into the above

environments is a challenge future research may choose to explore.

Turner (in Fine, 2000) also highlights the future role of ethology in the research and

application of the human-animal relationship. Veterinary ethology encompasses the

study of animal behaviour and will be especially beneficial for ensuring the correct use

of certain species of animals for certain patient groups and contexts.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

27

Nebbe (in Fine, 2000) focuses attention on the future potential of horticultural and

nature therapy. Horticultural therapy may include farm, greenhouse and garden

programmes.

Katcher (in Fine, 2000) suggests that the future of AAT may need to be examined in the

wider context of interaction with plants, gardens, open spaces and the wilderness.

Nature therapy involves reconnecting with our natural environment by wilderness trips,

walks in parks and other forms of exposure to nature. The power of metaphors is

especially useful in this context. Our long evolutionary history has always had a nature

context. Man has only become separated from this context in the last 150 years. Nature

therapy often fills the feeling of emptiness many city dwellers suffer from.

Thus one future of AAT may be the naturalizing of our work and care environments. A

new form of architecture may result which rejuvenates our concrete environments by

means of animals and plants.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

28

5. REFERENCE LIST

Beck, A.M., & Katcher, A.H. (1984). A new look at pet-facilitated therapy. JAVMA, 184 (4),

414-420.

Brickel, CM. (1986). Pet-facilitated therapies: A review of the literature and clinical

implementation considerations. Clinical Gerontologist,S (3/4), 309-331.

Daniel, S.A., Burke, J., & Burke, J. (1986). Educational programs for pet-assisted therapy in

institutional settings: An interdisciplinary approach. Veterinary Technician, 394-397.

Draper, J., Gerber, G.J., & Layng, E.M.(1990). Defining the role of pet animals in

psychotherapy. Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa, 15 (3), 169-172.

Fine, AH (ed.). (2000) Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and

guidelines for practice. San Diego, CA: Academic Press

Gammonley, J., & Yates, J. (1991). Animal assisted therapy in nursing homes. Journal of

Gerontological Nursing, 17 (1),12-15.

Kogan, LR, Granger BP, Fitchett, JA, Helmer, KA, & Young, KJ (1999). The human-animal

team approach for children with emotional disorders: Two case studies. Child and Youth Care

Forum, 28(2), 105-121.

Mallon, G.P. (1992). Utilization of animals as therapeutic adjuncts with children and youth: A

review ofthe literature. Child & Youth Forum, 21 (1),53-67.

Marr, CA, French, L, Thompson, D, Drum, L, Greening, G, Mormon, J, Henderson, I, &

Hughes, CW (2000). Animal-assisted therapy in psychiatric rehabilitation. Anthrozoos, 13(1),

43-47.

Messer, D., & Millar, S. (1999). Exploring Developmental Psychology: From infancy to

adolescence. London: Arnold.

Moneymaker, J.M., & Strimple, E.O. (1991). Animals and inmates: A sharing companionship

behind bars. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 16 (3/4), 133-152.

Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

29

Nebbe, L.L., (1991). The human-animal bond and the elementary school counselor. The School

Counselor, 38. 362-371.

Odendaal, J.S.J. (1989). 'n Historiese perspektief op mens-dier-interaksies

Journal of the South African Veterinary Association, 60 (3), 169-172.

as studieveld.

Odendaal, J.S.l (1992). Geselskapsdiere: moderne gebruike. Archimedes, 1,9-18.

Odendaal, JSJ (2000) Animal-assisted therapy - magic or medicine? Journal of Psychosomatic

Research, 49(4), 275-280

Prochaska, J.O. (1984). Systems of Psychotherapy. Chicago: The Dorsey Press.

6. RESOURCES

Human Animal Interaction Group: rina@ccnet.up.ac.za

The Delta Society: info@deltasociety.org

Therapy Dogs International: tdi@gti.net

Alpha Affiliates: AlphaAffiliates@webtv.net

Therapet Animal Assisted Therapy Foundation: Therapet@Juno.com

Dog-Play: http://www.dog-play.com

Create-a-smile: http://www .create-a-smile.org

Green Chimneys Children's Services: http://www.pcnet.coml-gchimney

The above sites also have listings and references to approximately a hundred different

organizations working with animal facilitated therapy in one form or another.