Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65 (2021) 127340

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ufug

Original article

Addressing psychosocial issues caused by the COVID-19 lockdown: Can

urban greeneries help?

Keeren Sundara Rajoo a,*, Daljit Singh Karam b, Arifin Abdu c, Zamri Rosli a,

Geoffery James Gerusu a,d

a Department of Forestry Science, Faculty of Agricultural Science and Forestry, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Nyabau Road, 97008, Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia

b Department of Land Management, Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

c Department of Forestry Science and Biodiversity, Faculty of Forestry and Environment, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

d Institut Ekosains Borneo, Universiti Putra Malaysia Bintulu Campus, Nyabau Road, 97008, Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia

ARTICLE INFO

Handling Editor: W Wendy McWilliam

Keywords:

COVID-19

Depression

Anxiety

Stress

Nature therapy

Preventive medicine

DASS-21

Exercise

ABSTRACT

The Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected over 200 countries, forcing governments to

impose lockdowns to contain the spread of the disease. Although effective in reducing infection rates, the

lockdowns have also resulted in a severe negative impact on mental health throughout the world; Setting the

foundation for mental illnesses to become the next “silent” pandemic. This study attempts to determine a self-

care method of ensuring mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for those living under lock

down. We evaluated the potential of physical exercise (in a nature setting) and nature therapy in improving

mental wellbeing, among young adults with either stress, anxiety or depression symptoms. The study involved

thirty subjects, who were equally divided into a nature-exercise group and a nature therapy group. The par

ticipants were briefed on the activities that they were to perform on a daily basis, and both groups performed

their assigned activities concurrently for one week (27th April 2020 to 3rd May 2020) at urban greeneries

accessible to them (rooftop parks, neighbourhood parks, home gardens). We used the depression, anxiety and

stress scale – 21 items (DASS-21) to evaluate the mental health status of participants, once before beginning the

study (baseline readings) and once at the end of the study (after a week of nature-exercise/nature therapy). There

was a statistically significant reduction in stress, anxiety and depression symptoms for both the nature-exercise

and nature therapy groups. However, when evaluating the effectiveness of exercise and nature therapy in

treating stress, anxiety and depression symptoms on a case-by-case basis, it was discovered that nature therapy

was more effective in treating mental health issues. Hence, nature therapy has the potential to be a form of

preventive medicine, namely in preserving mental health during the COVID-19 crisis.

1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (COVID-19)

outbreak occurred at Wuhan, China in December 2019 (Santarpia et al.,

2020), and has now become a global pandemic (Wang et al., 2020). The

total number of cases and deaths has far exceeded those of SARS, and as

of September 2021, COVID-19 has killed more than 4.5 million people

worldwide. Thus, it is no surprise that the World Health Organization

(WHO) has declared the COVID-19 outbreak as “the highest level of

emergency of international concern” (Cao et al., 2020).

1.1. Mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak

Pandemic outbreaks can have a negative impact on mental health,

causing psychosis, anxiety, trauma, suicidal tendencies, chronic stress

and panic (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). Several studies

have reaffirmed this with the COVID-19 pandemic (Kelly, 2020; Mog

hanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020; Rajkumar, 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Zhai

and Du, 2020). The impact appears to be worse in regions under lock

down (Jankowicz, 2020), . The increased stress and anxiety levels

caused by the outbreak have also been linked to an increase in domestic

* Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: keeren.rajoo@upm.edu.my, keeren.rajoo@gmail.com (K. Sundara Rajoo).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127340

Received 29 July 2020; Received in revised form 21 July 2021; Accepted 6 September 2021

Available online 8 September 2021

1618-8667/© 2021 Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved.

K. Sundara Rajoo et al.

violence and child abuse worldwide (Taub, 2020). Therefore, there is a

need for people to not only take precautions in avoiding COVID-19 in

fections, but to also take necessary measures in preserving mental health

(Grover et al., 2020).

Malaysia is no exception when it comes to the negative impacts of

lockdowns (NST, 2020a). Lockdowns and movement control orders have

been largely successful in flattening the curve, however there has been

several other setbacks (NST, 2020b). Malaysia is on the verge of expe

riencing its worse economic recession in history (Khalid, 2020), massive

unemployment (Lim, 2020) and a growth in mental deterioration

(Hassandarvish, 2020). Even before the pandemic, mental health issues

in Malaysia had tripled in the past two decades, attributed largely due to

a lack of awareness on mental health and also societal stigma pertaining

to mental illnesses (Chua, 2020). With the pandemic outbreak and

lockdowns in place, mental illnesses are set to become a “silent”

pandemic in Malaysia (Hassandarvish, 2020).

Thus, there is an obvious need for a self-care method that will improve

mental health during this pandemic, especially those living under lock

downs. The World Health Organization (World Health Organization

(WHO), 2020) has listed several actions/activities that can be taken to

preserve mental wellbeing during this pandemic, for example maintaining

a daily routine, exercising, maintaining a healthy diet and keeping in

regular contact with loved ones (via telephone, social media, etc.).

1.2. Nature therapy

Research has found that nature has the ability to improve mental

wellbeing, in a process known as “nature therapy”. Nature therapy,

sometimes referred to as ecotherapy, is a technique or treatment

employed to improve an individual’s physical or mental health using

natural surroundings. Nature therapy can be performed in any natural

setting, including forests, oceans or even home gardens (Chevalier,

2012). There are mainly two forms of nature therapy. The first does not

include certified professionals such as therapists and psychologists, but

simply uses nature itself as a form of therapy (Bielinis et al., 2018; Fur

uyashiki et al., 2019). The second is an evidence-based practice that uses

certified therapists or health specialists to improve physical and mental

health by incorporating nature (Berger and Tiry, 2012; Sonntag-O¨ stro¨m

et al., 2015; Dolling et al., 2017), and is often referred to as “forest

therapy” (Rajoo et al., 2019). For this paper, we will refer to the first type

as “nature therapy”, and the second type as “forest therapy”.

Despite numerous studies affirming the benefits of nature therapy in

terms of improving general well-being (Rajoo et al., 2020), yet the exact

mechanisms that allow for these benefits is still not fully understood

(Franco et al., 2017). The general consensus is that urban settings

overload human sensory with “polluted” senses, thus experiencing

natural environments provide a calming and restorative effect (Ulrich

et al., 1991). Therefore, the various activities performed in nature

therapy focuses on experiencing nature through each of our senses

(Franco et al., 2017).

For instance, nature therapy activities that focused on viewing natural

landscapes have been found to have a calming effect (Franco et al., 2017;

Rajoo et al., 2019), even reducing blood pressure of elderly hypertensive

men (Song et al., 2017b). Nature sounds like birdsongs have also been

used in nature therapy to relieve stress (Franco et al., 2017). Breathing

exercises are commonly performed to encourage the participants to

indulge in the “smell” of natural environments (Song et al., 2016). Elderly

patients with chronic pulmonary diseases gained more health benefit

from breathing exercises when performed in forests (Bing et a., 2016).

This can be attributed to breathing in phytoncides, which are antimi

crobial volatile organic compounds derived from trees, which improves

immunity (Ohtsuka et al., 1998; Li et al., 2006). It has also been reported

that psychiatric treatment for children was more effective when paired

with nature therapy at a beach (Berger and Tiry, 2012). Activities per

formed in this study focused on “touch” sensory, whereby children

played with sand and seawater while undergoing psychiatric therapy.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65 (2021) 127340

1.3. Study objective

This study attempts to determine a self-care method of ensuring

mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, using urban greeneries.

We evaluated the potential of nature therapy and physical exercise in

improving mental wellbeing, among young adults with either stress,

anxiety or depression symptoms. This study aims to serve as a pilot study

for future widescale research projects that can provide governmental

agencies, mental health professionals and the general public an effective

tool in safeguarding the mental wellbeing of society as a whole, in the

face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design, setting and participants

This study was approved by the University’s Ethic Committee for

Research Involving Human Subjects. This research was considered to be a

low risk research, whereby the Ethic Committee only raised anonymity as

being a cause for concern. The study utilized anonymous online surveys,

in all thirteen states and three federal territories of Malaysia. The survey

was propagated using social media and their anonymity were ensured, by

only using all data provided by the participants solely for this study. Any

personal identifiers such as contact details were only used for direct

communication pertaining to this study, and were deleted once the study

was concluded. Other personal details that could reveal the identity of

the participants were deleted at the conclusion of the study.

To obtain a homogenous group of participants, we focused on young

adults (18–40 years old) that believed they were suffering from mental

health issues as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic or the MCO.

The initial survey was conducted on 19th April 2020 to 23rd April 2020,

receiving 853 respondents, and we evaluated their mental health status.

We used the depression, anxiety and stress scale – 21 items (DASS-21),

which is a widely validated tool in evaluating the status of depression,

anxiety and stress of subjects (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995; Lee et al.,

2020). Each parameter (depression, anxiety and stress) is evaluated

separately in the questionnaire (seven items for each parameter), along

with different scoring weightages for each parameter; Stress symptoms

requires a score of ≥15, for anxiety symptom ≥ 8, and for depression

symptom ≥ 10 (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995).

Besides evaluating their mental health, the respondents were also

asked demographic questions and also how often they followed-up on

COVID-19 news. They were also asked the “zone level” at their place of

residence. The Ministry of Health of Malaysia categorizes the severity of

COVID-19 infection rates by zones; Green zones (no Covid-19 cases),

yellow zones (1–20 cases), orange zones (21–40 cases), and red zones

(41 cases and above). Red zones have more MCO restrictions in place,

while green zones have more leeway.

Only 42 of the initial 853 respondents exhibited either stress, anxiety

or depression symptoms. These 42 respondents also responded “none” to

the statement “What steps do you take to maintain your mental health?”,

indicating that they did not take any active measures to manage their

mental health.

An invitation was extended to these 42 respondents to participate in

this study on 24th April. Several subjects had to drop out of the study as

they didn’t have access to urban greeneries or due to other personal

issues that were not specified. The respondents were allowed to opt-out

of the study without providing justification, in line with the university’s

ethical committee’s guideline. Additionally, three more participants

didn’t comply with the study protocols and were removed from the

study. Thus, a total of thirty participants were recruited for this study.

The thirty participants were split and assigned to their respective

groups randomly; nature-exercise group and nature therapy group.

Both the groups performed their preassigned activities at urban

greeneries that were accessible to them; Rooftop parks, neighbourhood

parks, home gardens.

2

K. Sundara Rajoo et al.

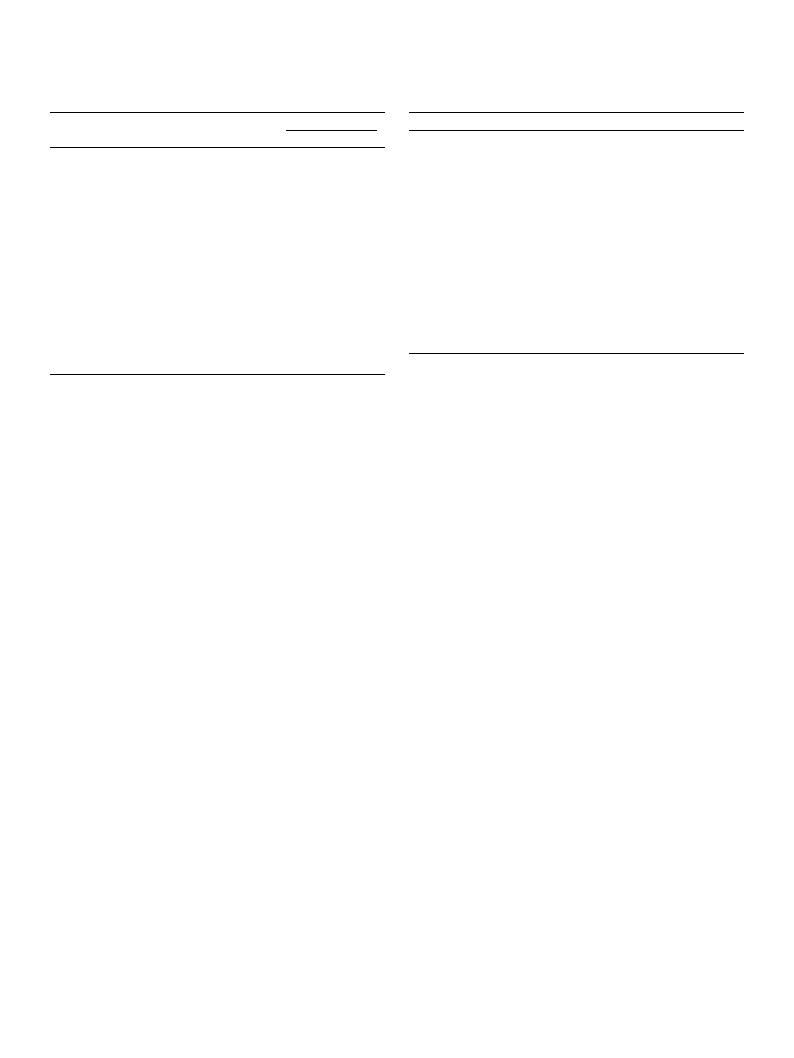

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of baseline DASS-21 scores of participants, before the

intervention study was conducted.

Total (N =

30)

Mean SD

Symptoms

Skewness Kurtosis

Yes

No

Stress

Anxiety

Depression

12.63 4.52 0.58

6.87 3.25 0.26

8.23 4.43 0.04

0.49

9 (30 %) 21 (70 %)

0.82

17 (56.67 13 (43.33

%)

%)

1.23

15 (50 %) 15 (50 %)

Exercise group (N = 15)

Stress

13.13 3.96 1.1

Anxiety

Depression

6.8

3.63 0.46

8.67 4.53 0.11

1.33

5 (33.33 10 (66.67

%)

%)

1.23

9 (60 %) 6 (40 %)

1.26

8 (53.33 7 (46.67

%)

%)

Nature therapy group (N = 15)

Stress

12.13 5.11 0.51

Anxiety

6.93 2.94 0.11

Depression

7.8

4.44 0.01

0.21

4 (26.67 11 (73.33

%)

%)

0.12

8 (53.33 7 (46.67

%)

%)

1.19

7 (46.67 8 (53.33

%)

%)

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65 (2021) 127340

Table 2

Relationship between baseline DASS-21 scores with COVID-19 variables, before

the intervention study was conducted.

Stress

Anxiety

Depression

COVID-19 Zone level

Following-up on

COVID-19 news

Red

Orange

Yellow

Green

Chi-Squared

test

Very often

Somewhat

often

Not very often

Never

Chi-Squared

test

21.75 ±

3.14

17.24 ±

2.75

14.4 ±

3.74

8.96 ±

6.32

0.03*

12.81 ±

4.23

11.6 ±

2.34

11.82 ±

4.74

–

0.21

7.13 ±

5.28

7.25 ±

3.41

6.5 ±

1.83

6.58 ±

2.74

0.39

7.14 ±

4.85

6.61 ±

1.7

5.21 ±

2.69

–

0.57

8.5 ± 2.2

8.63 ± 3.5

7.2 ± 4.8

4.84 ±

5.85

0.36

7.5 ± 2.5

8.6 ± 1.96

7.63 ± 1.7

–

0.37

N = 30, M ± SD, *p < 0.05.

Participants were briefed on their respective activities via a PDF file

attached to Google Docs, and were encouraged to ask questions

regarding their responsibilities either via email or WhatsApp. Both

groups performed their assigned activities daily and concurrently for

one week (27th April 2020 to 3rd May 2020) for approximately twenty

minutes. On 4th May, the participants’ mental health status was eval

uated once again, using the DASS-21.

For the nature-exercise group, we used a clinically proven exercise

program that was especially designed for beginners to perform without

any gym equipment (Kilka and Jordan, 2013). Each exercise in the circuit

is performed for 30 s, with 10 s transition time between. Total time for

entire circuit workout is approximately seven minutes. The twelve ex

ercise were jumping jacks, wall sit, knee push-up (regular push-up for

those who are able to), abdominal crunch, step-up onto chair, squat,

triceps dip on chair, plank, running in place, lunge, knee push-up

(push-up and rotation for those who are able to) and side plank. Partic

ipants either used YouTube or the Home Workout exercise app to guide

them throughout the exercise program. Participants also did appropriate

warm-up before exercising, and were reminded to not exert themselves.

For the nature therapy group, the participants performed three

common nature therapy activities; Sensory enjoyment, stretching exer

cises and meditation (Song et al., 2016). These activities were selected as

they had been found to be effective in a previous Malaysian forest

therapy study (Rajoo et al., 2019). Sensory enjoyment consisted of

engaging the senses with different natural aspects. This included visual

stimuli performed by observing the natural environment in detail, smell

by taking in deep breaths, sound by listening to natural sounds like

birdsongs, and touch by feeling the soil and flora. For stretching exer

cises, participants performed basic stretches incorporating the neck,

arms, lower back and legs. Participants were informed to not overdo the

stretches beyond their physical limit. Meditation either involved deep

breathing or reciting religious/spiritual mantras, which was performed

according the participant’s personal preferences. Each activity was

performed for five to seven minutes. The participants were briefed in

detail on how to practice each activity, and were instructed to conduct

the nature therapy program every morning, before the afternoon heat.

2.2. Data analysis method

The data were analysed using SPSS software version 25, for descrip

tive statistics and inferential statistics (chi-squared and dependent t-test).

Besides statically analysing the results, we also compared the data based

on a case-by-case basis, that is whether the week-long exercise or nature

therapy program was able alleviate the individuals’ stress, anxiety or

depression symptoms.

3. Results

3.1. Research participants’ demographic and baseline mental health

status

As mentioned previously, a total of 30 participants were involved in

this study, who were split evenly and assigned to their respective groups

randomly; nature-exercise group (N = 15) and nature therapy group (N

= 15). The participants were 26.2 ± 4.14 years old (20 males and 10

females). Table 1 shows the baseline mental health status of the re

spondents, that is their mental health status before the study was con

ducted. Of the thirty participants in this research, 30 % showed

symptoms of stress, 56.67 % had symptoms of anxiety while 50 % had

symptoms of depression. For the nature-exercise group, the majority

exhibited symptoms of anxiety (N = 9) and depression (N = 8). While for

the nature therapy group, a majority of the participants exhibited

symptoms of anxiety (N = 7), seven participants had symptoms of

depression while four had symptoms of stress.

3.2. Association between COVID-19 variable with mental health status

Table 2 shows the relationship between COVID-19 variables with

mental health status of the participants, before conducting the study. Of

the 30 study participants, four lived in red zones, five resided in orange

zones, nine lived in yellow zones while the remaining twelve lived in

green zones. More than 66 % of the participants followed COVID-19

related news very often (N = 11) or somewhat often (N = 9), while 33

% followed the news not very often (N = 10). None of the participants

said that they never followed the news at all. Pearson Chi-Square anal

ysis found no association between COVID-19 zone level with anxiety (X2

(1, N = 30) = 37.64, p = 0.39), and depression (X2 (1, N = 30) = 45.07, p

= 0.36). Pearson Chi-Square analysis also found no association between

following-up on COVID-19 news with stress (X2 (1, N = 30) = 45.81, p =

0.21), anxiety (X2 (1, N = 30) = 22.23, p = 0.57) and depression (X2 (1,

N = 30) = 29.94, p = 0.37). However, Pearson Chi-Square analysis

found an association between zone with stress (X2 (1, N = 30) = 40.74, p

= 0.03), whereby participants in red zones recorded higher stress.

3

K. Sundara Rajoo et al.

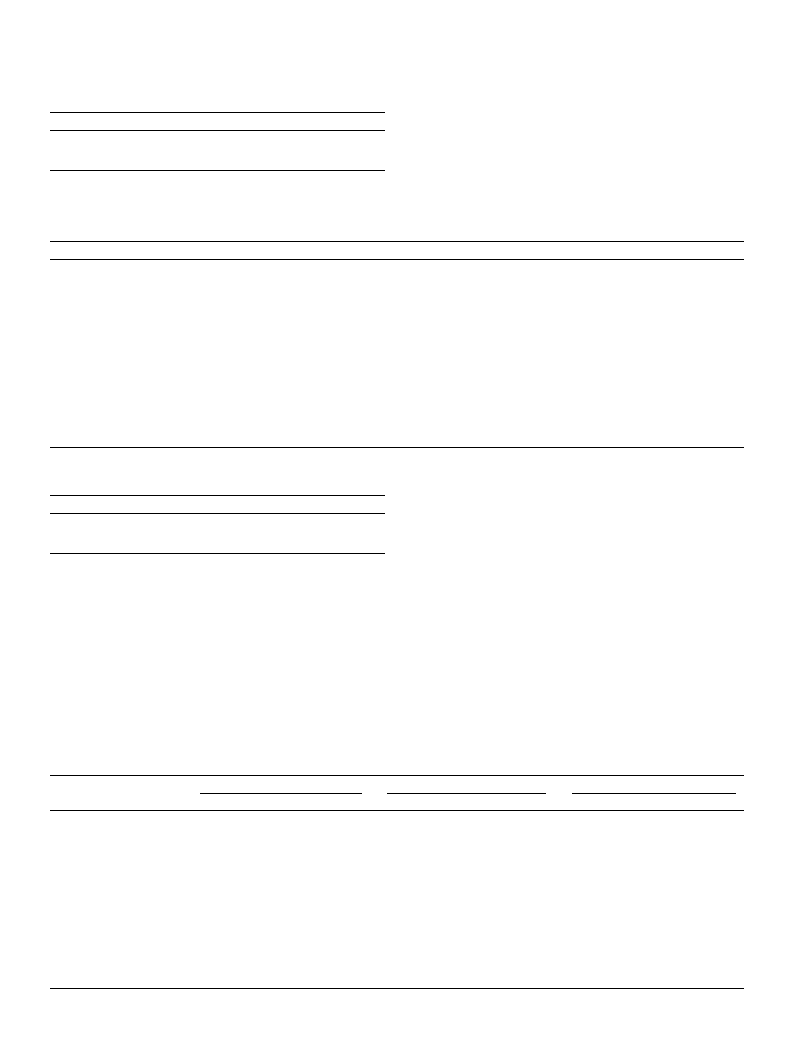

Table 3

Summarized effects of the nature-exercise program on DASS-21 scores of

participants.

Baseline

After

t-test

Stress

Anxiety

Depression

13.13 ± 3.96

6.8 ± 3.63

8.67 ± 4.53

11.27 ± 4.41

5.27 ± 3.6

7.2 ± 7.2

0.00*

0.02*

0.01*

N = 15, M ± SD, *p < 0.05.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65 (2021) 127340

The depression baseline readings before the program (M = 8.67, SD =

±4.53) significantly reduced after the nature-exercise program (M =

7.2, SD = ±7.2), (t(14) = 3.0, p < 0.01). However, the results weren’t as

promising when the effects of exercise were evaluated on a case-by-case

basis (Table 4). Of the five subjects that exhibited stress symptoms, only

one individual (Subject-E4) ceased to show stress symptoms after one-

week of exercise. Nine participants had anxiety symptoms, but only

four participants (Subject-E2, Subject-E5, Subject E-6 and Subject E-11)

stopped showing anxiety symptoms, while out of the eight participants

Table 4

Effects of the nature-exercise program on DASS-21 scores, by subject.

Stress Symptoms

Subject

Subject-E1

Subject-E2

Subject-E3

Subject-E4

Subject-E5

Subject-E6

Subject-E7

Subject-E8

Subject-E9

Subject-E10

Subject-E11

Subject-E12

Subject-E13

Subject-E14

Subject-E15

Gender/Age

Male, 21

Female, 27

Female, 32

Male, 26

Male, 20

Male, 39

Male, 27

Female, 27

Female, 23

Male, 27

Male, 28

Male, 19

Female, 27

Female, 28

Male, 30

Baseline

23 (Yes)

18 (Yes)

16 (Yes)

16 (Yes)

14 (No)

11 (No)

11 (No)

10 (No)

9 (No)

12 (No)

10 (No)

11 (No)

13 (No)

8 (No)

15 (Yes)

After

19 (Yes)

18 (Yes)

15 (Yes)

12 (No)

11 (No)

9 (No)

12 (No)

9 (No)

5 (No)

14 (No)

7 (No)

9 (No)

8 (No)

5 (No)

16 (Yes)

Improvement

No

No

No

Yes

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

No

Anxiety Symptoms

Baseline

11 (Yes)

9 (Yes)

12 (Yes)

7 (No)

8 (Yes)

9 (Yes)

4 (No)

2 (No)

2 (No)

10 (Yes)

8 (Yes)

1 (No)

2 (No)

9 (Yes)

8 (Yes)

After

8 (Yes)

7 (No)

11 (Yes)

5 (No)

5 (No)

4 (No)

2 (No)

1 (No)

1 (No)

8 (Yes)

5 (No)

1 (No)

1 (No)

10 (Yes)

10 (Yes)

Improvement

No

Yes

No

–

Yes

Yes

–

–

–

No

Yes

–

–

No

No

Depression Symptoms

Baseline

11 (Yes)

6 (No)

9 (No)

4 (No)

4 (No)

2 (No)

16 (Yes)

10 (Yes)

13 (Yes)

11 (Yes)

5 (No)

14 (Yes)

13 (Yes)

2 (No)

10 (Yes)

After

10 (Yes)

5 (No)

5 (No)

4 (No)

3 (No)

3 (No)

15 (Yes)

8 (No)

13 (Yes)

10 (Yes)

2 (No)

8 (No)

10 (Yes)

1 (No)

11 (Yes)

Improvement

No

–

–

–

–

–

No

Yes

No

No

–

Yes

No

–

No

Table 5

Summarized effects of nature therapy on DASS-21 scores of participants.

Baseline

After

t-test

Stress

Anxiety

Depression

12.13 ± 5.11

6.93 ± 2.94

7.8 ± 4.44

7.67 ± 3.48

4.8 ± 2.46

4.53 ± 2.85

0.00*

0.00*

0.00*

N = 15, M ± SD, *p < 0.05.

3.3. Effects of nature-exercise on mental health

Table 3 shows that there was a significant reduction in stress, anxiety

and depression symptoms after the nature-exercise program. The stress

levels of the participants reduced significantly after the nature-exercise

program (M = 11.27, SD = ±4.41) when compared to the baseline

readings before the nature-exercise program (M = 13.13, SD = ±3.96),

(t(14) = 3.2, p < 0.001). Similarly, the anxiety baseline readings before

the program (M = 6.8, SD = ±3.63) significantly reduced after the

nature-exercise program (M = 5.27, SD = ±3.6), (t(14) = 3.1, p < 0.02).

that had depression symptoms, only two (Subject-E8 and Subject-E12)

stopped showing depression symptoms.

3.4. Effects of nature therapy on mental health

Similar to the nature-exercise group, there was a significant reduc

tion in stress, anxiety and depression symptoms after a week-long nature

therapy program (Table 5). The stress levels of the participants reduced

significantly after the nature therapy program (M = 7.67, SD = ±3.48)

when compared to the baseline readings before the nature therapy

program (M = 12.13, SD = ±5.11), (t(14) = 7.9, p < 0.001). Similarly,

the anxiety baseline readings before the program (M = 6.3, SD = ±2.94)

significantly reduced after the nature therapy program (M = 4.8, SD =

±2.46), (t(14) = 3.1, p < 0.001). The depression baseline readings

before the program (M = 7.8, SD = ±4.44) significantly reduced after

the nature therapy program (M = 4.53, SD = ±2.85), (t(14) = 5.2, p <

0.001). Moreover, unlike the nature-exercise group, the effects on an

individual basis were also promising (Table 6). After nature therapy, all

Table 6

Effects of nature therapy on DASS-21 scores, by subject.

Stress Symptoms

Subject

Gender/Age

Baseline

After

Subject-N1

Subject-N2

Subject-N3

Subject-N4

Subject-N5

Subject-N6

Subject-N7

Subject-N8

Subject-N9

Subject-N10

Subject-N11

Subject-N12

Subject-N13

Subject-N14

Subject-N15

Male, 33

Male, 31

Male, 19

Male, 24

Female, 24

Female, 25

Male, 28

Male, 23

Male, 27

Female, 30

Female, 28

Male, 21

Male, 19

Male, 33

Male, 30

18 (Yes)

19 (Yes)

23 (Yes)

14 (No)

12 (No)

13 (No)

9 (No)

15 (Yes)

11 (No)

10 (No)

11 (No)

9 (No)

4 (No)

9 (No)

5 (No)

12 (No)

12 (No)

14 (No)

9 (No)

8 (No)

9 (No)

5 (No)

11 (No)

8 (No)

6 (No)

4 (No)

5 (No)

2 (No)

5 (No)

5 (No)

Improvement

Yes

Yes

Yes

–

–

–

–

Yes

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Anxiety Symptoms

Baseline

After

8 (Yes)

10 (Yes)

13 (Yes)

4 (No)

3 (No)

9 (Yes)

2 (No)

8 (Yes)

6 (No)

8 (Yes)

9 (Yes)

4 (No)

5 (No)

7 (No)

8 (Yes)

6 (No)

7 (No)

8 (Yes)

2 (No)

1 (No)

7 (No)

0 (No)

5 (No)

6 (No)

4 (No)

8 (Yes)

4 (No)

3 (No)

5 (No)

6 (No)

Improvement

Yes

Yes

No

–

–

Yes

–

Yes

–

Yes

No

–

–

–

Yes

Depression Symptoms

Baseline

After

3 (No)

7 (No)

5 (No)

11 (Yes)

10 (Yes)

2 (No)

10 (Yes)

6 (No)

7 (No)

3 (No)

15 (Yes)

12 (Yes)

14 (Yes)

11 (Yes)

1 (No)

1 (No)

4 (No)

2 (No)

8 (No)

5 (No)

2 (No)

7 (No)

3 (No)

4 (No)

1 (No)

7 (No)

4 (No)

10 (Yes)

8 (No)

2 (No)

Improvement

–

–

–

Yes

Yes

–

Yes

–

–

–

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

–

4

K. Sundara Rajoo et al.

four participants (Subject-N1, Subject-N2, Subject-N3 and Subject-N8)

that had stress symptoms, showed no symptoms after nature therapy.

Out of the eight participants that had anxiety symptoms, six participants

(Subject-N1, Subject-N2, Subject-N6, Subject-N8, Subject-N10 and

Subject N-15) ceased showing symptoms. Six out of the seven partici

pants that had depression symptoms, stopped showing symptoms after

nature therapy (Subject-N4, Subject-N5, Subject-N7, Subject-N11, Sub

ject-N12 and Subject-N14).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine a self-care method of

ensuring mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, using urban

greeneries. We evaluated the potential of nature therapy and physical

exercise (in a nature setting) in improving mental wellbeing, among

young adults with either stress, anxiety or depression symptoms. Sta

tistical analysis found an association between zone and stress, where

residents of red zones were more likely to experience stress symptoms.

Which is understandable since residents of red zones have more re

strictions in place compared to other zones. Red zone inhabitants have

their movement severely restricted via police roadblocks (they can only

travel within 10 km for essential goods and services), have increased law

enforcement surveillance and in some extreme cases, they are not even

allowed to leave their homes for essential goods (food supplies are

delivered directly to them). Thus, individuals under severe quarantine

conditions are more at risk of mental health deterioration (Moghani

bashi-Mansourieh, 2020).

There was a significant reduction in stress, anxiety and depression

symptoms for both the nature-exercise and nature therapy groups.

However, everyone reacts differently to stressful situations, thus the key

to effective mental health management is to ensure that the resources

are appropriate to their needs (Reinhard, 2000; Arya, 2020). When

evaluating the effectiveness of nature-exercise and nature therapy in

treating stress, anxiety and depression symptoms on a case-by-case

basis, it is apparent that nature therapy is more effective than exercise

in treating mental health issues. As mentioned previously, studies have

proven that nature therapy has a positive effect on human health, from

both physiological and psychosocial perspectives. Moreover, nature

therapy has also been found to be able to alleviate depression (Fur

uyashiki et al., 2019), manage stress for highly-stressed individuals

(Dolling et al., 2017), and in treating patients with severe exhaustion

disorders (Sonntag-O¨ stro¨m et al., 2015). Thus, in line with the findings

of this study, nature therapy could be an effective tool in mental health

management during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There has been much debate on why natural environments have a

positive effect on mental and physical health (Rajoo et al., 2021). Some

researchers believe that it is the activities performed in nature that

brings benefit, and not nature itself. Therapeutic activities and light

exercises like stretching exercises have been found to have a positive

effect on the immune system (Smyth et al., 2002), blood glucose levels

(Ohtsuka et al., 1998) and chronic stress reduction (Dolling et al., 2017).

However, several studies that examined the effects of urban environ

ments and natural environments on human health, discovered that the

positive effects of relaxing activities and light exercises could only be

experienced by participants in forest settings (Bing et al., 2016; Song

et al., 2017b). Ulrich et al. (1991) proposed that living in

structure-dominant environments would increase the stress levels of

urbanites, causing them to be more susceptible to mental and physical

illnesses. The Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) developed by Ulrich et al.

(1991) explains the need for urbanites to experience natural elements at

times. SRT states that by observing natural sceneries, such as greeneries

and lakes, it creates positive feelings and emotions that enables a

restorative effect. This theory isn’t new. In ancient Rome, it was com

mon for people to periodically take refuge in forested areas to deal with

urban congestion (Glacken, 1967). Some researchers believe the healing

powers of nature is primarily due to phytoncides, a volatile substance

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65 (2021) 127340

emitted by plants Li et al. (2006). Song et al. (2016) discovered that

indoor exposure to forest derived phytoncides could increase NK cell

activity and improve overall immunity function. Hence, it is safe to

conclude that the health benefits derived from nature therapy is due to a

combination of relaxing activities, light exercises and the natural ther

apeutic atmosphere.

5. Conclusion

The core objective of this study was to serve as a pilot study for future

widescale research projects that can provide key stakeholders and the

general public an effective method to manage mental health, especially

during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study found that both exercise and

nature therapy when performed at urban greeneries, has the potential to

be a form of preventive medicine, namely in preserving mental health

during the COVID-19 crisis. In this regard, mental health professionals

should advise the general public on the actions/activities that they can

take to prevent mental health issues, especially for those under quar

antine or lockdowns. For individuals with access to natural sceneries

such as home gardens, nature therapy should be one of the activities

performed on a daily basis.

This study has several limitations. Namely, the lack of a control

group. This meant that other factors, such as time, could have improved

mental health instead of the interventions. Other factors such as gender,

age and type of greenery were also variables that can affect the outcome

of the study, but could not be statistically analysed due to a small sample

size. Thus, this pilot study is best used as a foundation for future research

in this area. Future studies should involve a larger sample size, and use

other evaluation tools besides DASS-21, including direct psychiatric

evaluation. The potential for nature therapy to serve as a preventive

medicine for individuals experiencing mental fatigue and work stress

should also be evaluated. Appropriate governmental agencies should

develop effective self-care nature therapy programs for the general

public, allowing for the preservation and improvement of the mental

wellbeing of society.

Author statement

Keeren Sundara Rajoo contributed to the conceptualization, method

ology, interpretation of results and writing. Daljit Singh Karam contrib

uted to the data acquisition, interpretation of results and writing. Arifin

Abdu contributed to interpretation of results and writing. Zamri Rosli and

Geoffery James Gerusu contributed to the writing (Review & Editing).

Financial disclosure

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all respondents that participated in

this study. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for

their invaluable feedback that help improve this article.

References

Arya, D.K., 2020. Case management, care-coordination and casework in community

mental health services. Asian J. Psychiatr. 50, 101979 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

ajp.2020.101979.

Berger, R., Tiry, M., 2012. The enchanting forest and the healing sand – nature therapy

with people coping with psychiatric difficulties. Art Psychother. 39, 412–416.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.03.009.

5

K. Sundara Rajoo et al.

Bielinis, E., Takayama, N., Boiko, S., Omelan, A., Bielinis, L., 2018. The effect of winter

forest bathing on psychological relaxation of young Polish adults. Urban For. Urban

Green. 29, 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.12.006.

Bing, B.J., Xin, Y.Z., Xiang, M.G., Dong, L.Y., Lin, W.X., Hong, X.W., Ling, L.X., Bao, C.Y.,

Fu, W.G., 2016. Health effect of forest bathing trip on elderly patients with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 29 (3), 212–218. https://doi.

org/10.3967/bes2016.026.

Cao, Z., Zhang, Q., Lu, X., Pfeiffer, D., Jia, Z., Song, H., Zeng, D.D., 2020. Estimating the

effective reproduction number of the 2019-nCoV in China. medRxiv. https://doi.

org/10.1101/2020.01.27.20018952.

Chevalier, G., 2012. Earthing: health implications of reconnecting the human body to the

earth’s surface electrons. Pittsburgh J. Environ. Public Health Law 291541. https://

doi.org/10.1155/2012/291541.

Chua, S.N., 2020. The economic cost of mental disorders in Malaysia. Lancet 7 (4), E23.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30091-2.

Dolling, A., Nilsson, H., Lundell, Y., 2017. Stress recovery in forest or handicraft

environments – an intervention study. Urban For. Urban Green. 27, 162–172.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.07.006.

Franco, L.S., Shanahan, D.F., Fuller, R.A., 2017. A review of the benefits of nature

experiences: more than meets the eye. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14 (8), 864.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080864.

Furuyashiki, A., Tabuchi, K., Norikoshi, K., Kobayashi, T., Oriyama, S., 2019.

A comparative study of the physiological and psychological effects of forest bathing

(Shinrin-yoku) on working age people with and without depressive tendencies.

Environ. Health Prev. Med. 24, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-019-0800-

1.

Glacken, C.J., 1967. Traces on the Rhodian Shore: Nature and Culture in Western

Thought from Ancient Times to the End of the Eighteenth Century. University of

California Press.

Grover, S., Dua, D., Sahoo, S., Mehra, A., Nehra, R., Chakrabarti, S., 2020. Why all

COVID-19 Hospitals should have Mental Health Professionals: the importance of

mental health in a worldwide crisis! Asian J. Psychiatry (Pre-Proof). https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102147.

Hassandarvish, M., 2020. Malaysian Expert: Silent Mental Illness ‘pandemic’ to Arrive

Following Covid-19 Economic Fallout. Retrieved from. https://www.malaymail.

com/news/life/2020/04/28/malaysian-expert-silent-mental-illness-pandemic-to-arr

ive-following-covid-1/1860920.

Jankowicz, M., 2020. More People Are Now in’ Lockdown’ Than Were Alive During

World War II. Retrieved from. https://www.sciencealert.com/one-third-of-the-

world-s-population-are-now-restricted-in-where-they-can-go.

Kelly, B.D., 2020. Emergency mental health legislation in response to the Covid-19

(Coronavirus) pandemic in Ireland: urgency, necessity and proportionality. Int. J.

Law Psychiatry 70, 101564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101564.

Khalid, N., 2020. Impact of Pandemic on Economy and Recovery Policy. Retrieved from.

https://www.bernama.com/en/features/news.php?id=1829686.

Kilka, B., Jordan, C., 2013. High-Intensity circuit training using body weight: maximum

results with minimal investment. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 17 (3), 8–13.

Lee, K.W., Ching, S.M., Hoo, F.K., Ramachandran, V., Chong, S.C., Tusimin, M.,

Nordin, N.M., Devaraj, N.K., Cheong, A.T., Chia, Y.C., 2020. Neonatal outcomes and

its association among gestational diabetes mellitus with and without depression,

anxiety and stress symptoms in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. Midwifery 81,

102586.

Li, Q., Ari, N., Hiroki, M., Yoshifumi, M., Alan, M.K., Tomoyuki, K., Kanehisa, M., 2006.

Phytoncides (Wood essential oils) induce human natural killer cell activity.

Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 28 (2), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/

08923970600809439.

Lim, J., 2020. Malaysia Unemployment Rate Expected to Hit 4% This Year Due to Covid-

19. Retrieved from. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/malaysia-une

mployment-rate-expected-hit-4-year-due-covid19.

Lovibond, P.F., Lovibond, S.H., 1995. The structure of negative emotional states:

comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression

and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Theory 33 (3), 335–343.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65 (2021) 127340

Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, A., 2020. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general

population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51, 102076 https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076.

New Straits Times (NST), 2020a. Coronavirus: Malaysia Records Eight Deaths; 153 New

Cases Bring Total to 1,183. Retrieved from. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/s

e-asia/malaysia-records-fourth-coronavirus-death.

New Straits Times (NST), 2020b. Covid-19 to Have’ profound’ Mental Health Fallout.

Retrieved from. https://www.nst.com.my/world/world/2020/04/584739/covid

-19-have-profound-mental-health-fallout.

Ohtsuka, Y., Yabunaka, N., Takayama, S., 1998. Significance of shinrin-yoku (Forest-Air

bathing and walking) as an exercise therapy for elderly patients with diabetes

mellitus. J. Jpn. Assoc. Phys. Med. Balneol. Climatol. 61 (2), 101–105. https://doi.

org/10.11390/onki1962.61.101.

Rajkumar, R.P., 2020. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature.

Asian J. Psychiatr. 52, 102066 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066.

Rajoo, K.S., Karam, D.S., Abdu, A., Rosli, Z., Geoffery, J.G., 2021. Urban Forest Research

in Malaysia: A Systematic Review. Forests. Forests 12 (7), 903. https://doi.org/

10.3390/f12070903. In press.

Rajoo, K.S., Karam, D.S., Abdul, A.N.A., 2019. Developing an effective forest therapy

program to manage academic stress in conservative societies: a multi-disciplinary

approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 43, 126353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

ufug.2019.05.015.

Rajoo, K.S., Karam, D.S., Wook, N.F., Abdullah, M.Z., 2020. Forest Therapy: An

environmental approach to managing stress in middle-aged working women. Urban

Forestry & Urban Greening 55, 126853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

ufug.2020.126853. In press.

Santarpia, J.L., Rivera, D.N., Herrera, V., Morwitzer, M.J., Creager, H., Santarpia, G.W.,

Crown, K.J., Major-Brett, D., Schnaubelt, E., Broadhurst, M.J., Lawler, J.V., Reid, S.

P., Lowe, J.J., 2020. Transmission potential of SARS-CoV-2 in viral shedding

observed at the university of nebraska medical center. medRxiv. 2020 https://doi.

org/10.1101/2020.03.23.20039446.

Smyth, M.J., Hayakawa, Y., Takeda, K., Yagita, H., 2002. New aspects of natural-killer-

cell surveillance and therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2 (11), 850–861. https://

doi.org/10.1038/nrc928.

Song, C., Harumi, I., Yoshifumi, M., 2016. Physiological effects of nature therapy: a

review of the research in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13 (8), 781–798.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13080781.

Song, C., Ikei, H., Kobayashi, M., Miura, T., Li, Q., Kagawa, T., Kumeda, S., Imai, M.,

Miyazaki, Y., 2017. Effects of viewing forest landscape on middle-aged hypertensive

men. Urban For. Urban Green. 21, 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

ufug.2016.12.010.

Sonntag-O¨ stro¨m, E., Stenlund, T., Nordin, M., Lundell, Y., Ahlgren, C., Fjellman-

Wiklund, A., Ja¨rvholm, L.S., Dolling, A., 2015. “Nature’s effect on my mind” –

patients qualitative experiences of a forest-based rehabilitation programme. Urban

For. Urban Green. 14, 607–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.06.002.

Taub, A., 2020. A New Covid-19 Crisis: Domestic Abuse Rises Worldwide. Retrieved

from. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/world/coronavirus-domestic-violen

ce.html.

Ulrich, R.S., Simons, R.F., Losito, B.D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M.A., Zelson, M., 1991. Stress

recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ.Psychol. 11

(201), 230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7.390.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C.S., Ho, R.C., 2020. Immediate

psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019

coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.3390/

ijerph17051729.

World Health Organization (WHO), 2020. Mental Health and Psychosocial

Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak, 18 March 2020. World Health

Organization.

Zhai, D., Du, Xue., 2020. Addressing collegiate mental health amid COVID-19 pandemic.

Psychiatry Res. 288, 113003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113003.

6