Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Cleaner Production

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro

Organising in the Anthropocene: an ontological outline for ecocentric

theorising

Pasi Heikkurinen a, *, Jenny Rinkinen b, Timo Ja€rvensivu c, Kristoffer Wilen d, Toni Ruuska e

a University of Leeds, Sustainability Research Institute, Leeds, LS2 9JT, United Kingdom

b Lancaster University, DEMAND Centre, Department of Sociology, Lancaster, LA1 4YD, United Kingdom

c Aalto University School of Business, Department of Marketing, Helsinki, 00100, Finland

d Hanken School of Economics, Department of Marketing, Helsinki, 00100, Finland

e Aalto University School of Business, Department of Management Studies, Helsinki, 00100, Finland

article info

Article history:

Received 27 August 2015

Received in revised form

3 December 2015

Accepted 9 December 2015

Available online 23 December 2015

Keywords:

Anthropocene

Ecocentric

Ecocentrism

Ecosophy

Ontology

Organisation

abstract

As a response to anthropogenic ecological problems, a group of organisation scholars have acknowledged

the importance of ecocentric theorising that takes materiality and non-human objects seriously. The

purpose of this article is to examine the philosophical basis of ecocentric organisation studies and

develop an ontological outline for ecocentric theorising in the Anthropocene. The paper identifies the

central premises of ecocentric organisations from the previous literature, and complements the theory

with a set of ontological qualities common to all objects. The study draws on recent advances in object-

oriented and ecological philosophies to present three essential qualities of objects, namely autonomy,

uniqueness, and intrinsicality. The paper discusses how these qualities are critical in reclaiming the lost

credibility and practical relevance of ecocentrism in both organisational theory and the sustainability

sciences in general. To organise human activities in a sustainable manner in the new geological era, a

new ontology is needed that not only includes materiality and non-humans in the analysis, but also leads

to an ecologically and ethically broader understanding of ecospheric beings and their relationships.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In the era of the Anthropocene (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000;

Crutzen, 2002), it is increasingly acknowledged that the way hu-

man life is organised is ecologically damaging and jeopardises the

existence of most beings (MA, 2005; Barnosky et al., 2011; IPCC,

2014). Especially since the Industrial Revolution, or more pre-

cisely the invention of the steam engine, the biosphere and its local

ecosystems have undergone radical changes in terms of rising

temperatures and a reduction in biodiversity (Zalasiewicz et al.,

2008; Barnosky et al., 2012). Climate scientists have recorded a

worrying global temperature rise of 1 C since the early twentieth

century (NASA/GISS, 2014), while biologists and palaeontologists

have suggested that the sixth mass extinction might be on the

horizon if the current rate of species loss continues (Barnosky et al.,

* Corresponding author. Tel.: þ44 (0)113 343 9631.

E-mail addresses: p.heikkurinen@leeds.ac.uk (P. Heikkurinen), jenny.rinkinen@

lancaster.ac.uk (J. Rinkinen), timo.jarvensivu@aalto.fi (T. Ja€rvensivu), kristoffer.

wilen@hanken.fi (K. Wilen), toni.ruuska@aalto.fi (T. Ruuska).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.12.016

0959-6526/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

2011, 2012; Ceballos et al., 2015). These two changes in the envi-

ronment are assumed to be causally related, so that global warming

is leading to biodiversity loss, as ecosystems and their organisms

are unable to adapt to the rapid climatic changes in their habitat

(MA, 2005). To avert further damage, continued population growth,

excessive resource use and environmental deterioration are chal-

lenges that humanity must deal with within the next few decades

(Steffen et al., 2007), and arguably, the sooner the better (see e.g.,

Ceballos et al., 2015).

Despite the severity of the ecological challenge, and particularly

the significant role that the organisation of production has in the

climate crisis (Barnosky et al., 2012; IPCC, 2014), ecological ques-

tions have remained at the periphery of contemporary organisation

theory, as reviewed by Cunha et al. (2008). Rather than focussing on

the non-human and material aspects of the world, organisational

enquiries have tended to emphasise the role of humans and non-

material aspects of the organisation (Fleetwood, 2005;

Orlikowski, 2010). It follows that organisational studies are in-

clined to reproduce the anthropocentric and antirealist philo-

sophical tradition of science, as the human experience is favoured

at the expense of the non-human world. The absence of an

706

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

ecological perspective on organising human activity seems likely to

lead the way deeper into the Anthropocene with unpleasant con-

sequences not only for the human species but also for the

ecosystem as a whole.

The lack of organisational theorising from an ecological

perspective was first noticed in the mid-1990s, when the rela-

tionship between organisations and the natural environment

attracted scholarly attention (Shrivastava, 1994; Gladwin et al.,

1995; Clair et al., 1996). Some of the early scholars discussed, for

instance, the relevance of organisational activities to developments

such as overpopulation and overconsumption (Starik and Rands,

1995), as well as the limitations of an anthropocentric worldview

in dealing with ecological problems (Purser et al., 1995). Thus,

instead of continuing to position human actors above other beings

and interpreting the world in terms of human values, these scholars

developed and called for ecocentric approaches in the ontological,

epistemological, and axiological domains of organisation studies

(Shrivastava, 1994, 1995; Purser et al., 1995; Starik and Rands, 1995;

Starik, 1995).

While the call was not immediately taken up, a few organisa-

tional scholars have recently expressed signs of ecocentric theo-

rising by embedding social actors in the ecosystem (Whiteman and

Cooper, 2000), recognising the interconnectedness of all actors in

the ecosystem (Valente, 2012; Newton, 2002), and advancing

ethical considerations for the non-human world (Gosling and Case,

2013; Ezzamel and Willmott, 2014). Critics of ecocentrism, how-

ever, have continued to question the necessity and practicality of

ecocentric thought, as well as the underpinnings of its worldview

(Hanna, 1996). An intellectually well-founded critique on ecocen-

trism has been presented on the feasibility of reordering the human

relationship with the natural environment, and on the dualistic

representations of nature and humans (Newton, 2002). These

fundamental, yet constructive strictures on ecocentrism, coming

from both the managerial and sociological sides of organisation

studies, invite environmental scientists to revisit the philosophical

foundations of ecocentric theory.

Against this background, the purpose of this paper is to examine

the philosophical basis of ecocentric organisation studies, and

develop an ontological outline for ecocentric theorising in the

Anthropocene. The study is guided by the following research

questions: (a) what are the central premises of ecocentric organi-

sations in the previous literature, and (b) how might these premises

be complemented in order to respond to the criticism of ecocentric

thought and advance ontology for an ecological organisation?

Without a thorough discussion on the basic categories of being

and how they relate to each other (particularly those between

human and non-human objects), the task of advancing ecocentric

theory becomes not only extremely demanding, but can also

threaten the credibility of the approach and attract criticism of a

failure to deliver practical value. The importance of focussing on

ontological questions is reinforced by the premise that the way

humans perceive objectseand their relationsewill influence the

way things are (and will be) organised. Hence, the nature of objects

is crucial in the search for ecological organisations, including sus-

tainable modes of production.1

The paper begins with a brief introduction to the questions of

ontology in organisation studies and provides an overview of the

1 A sustainable mode of production as imagined in this study is not limited to the

early German concept on sustainability (Nachhaltigkeit), which appeared in 1712 in

the writings of von Carlowitz “to indicate how monetary profits could be made

from nature by obtaining optimum sustainable yields” (Martinez-Alier, 2014, p. 38)

but is instead in line with the idea of strong sustainability (e.g., Pearce and

Atkinson, 1993; Beckerman, 1995; Ayres et al., 2001).

challenges related to the Anthropocene: the current geological era.2

The study proceeds to review the ways previous studies in the field

of the organisation and the natural environment have con-

ceptualised humanenature relationships, and also to identify the

central premises of ecocentric organisations. To advance ecocentric

theorising, the paper draws on object-oriented and ecological

philosophies to arrive at a set of essential qualities of objects. Lastly,

it proposes an ontological outline for further studies and concludes

by discussing the implications of the outline for ecological practice

and theory.

2. Ontological questions in the age of humans

The field of organisation studies has undergone several intel-

lectual redirections or turns within its relatively short history

(Reed, 2005). Some of these turns have dealt with the means of

acquiring and analysing data, while others have focused more on

the assumptions related to the nature of knowledge and reality, or

ontology. The ontological position of a person, community, or turn,

could be described as a way of understanding the nature of reality.

An ontology can also more directly, and quite literally, be thought of

as how the world is: ‘what exists, and so what are the primary

entities of concern in any given field, and what are their most

general features and relationships’ (Spash, 2012, p. 37). Moreover,

as ontologies deal with the question of existence and being, they

are often considered the most profound concerns in scientific

enquiries.

Fleetwood (2005, p. 197) describes the ontological discussion in

organisation studies as ambiguous, ‘which makes it difficult to get

to the bottom of ontological claims and, of course, to locate the

source of any ontological errors’. Ontological discussions often also

mix with epistemological questions (that relate to knowledge) and

axiological questions (that relate to value), which make them even

more complex and challenging to grasp. Owing to its often-

assumed lack of practical implications for managers and its weak

relevance to what might be called the publication rat race, ontology

(as a study of being and existence) might also have a forbidding

echo for some organisation theorists. However, if scholars seek

ecologically advanced understandings of organisations, the exam-

ination of ontologies may offer not only prolific grounds and

stimulating avenues in the quest for considering different objects

and their relations, such as man-made organisations and the nat-

ural environment, but may also be unavoidable in the current times

of ecological, and sociocultural, turmoil. The climatic and geological

changes are arguably pressing humans to rethink their relationship

with other humans and the non-human world through recent

phenomena like climate refugees and mass extinctions.

The ontologies in organisation studies have recently been

heavily influenced by the cultural, linguistic, post-structural or

postmodern approaches that build on an idea of socially con-

structed realities (Fleetwood, 2005). For an ecocentric inquiry, this

development can be considered problematic because, in the anti-

realist ontology, a world does not exist independent of human

perception, and because the proponents of antirealism do not

subscribe to any causal scientific independence of matters of fact in

the world (Ma€ki, 2008). To put it bluntly, if the causality of human

action and ecological harm cannot be propounded with any degree

of certainty, then protective measures (e.g., conservation efforts)

are difficult to justify and legitimise.

2 A team of scientists led by Jan Zalasiewicz announced that in 2017 a decision

will be made on whether the current geological epoch will be officially re-named

(Schwa€gerl, 2013).

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

707

According to a recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change, the main causes of global warming are anthro-

pogenic greenhouse gas emissions, which are in turn undesired

consequences of economic and population growth (IPCC, 2014), and

particularly the former (UNEP, 2011; Lorek and Spangenberg, 2014).

The growth of economies (measured in gross national product) and

in the number of human inhabitants on the planet, have meant a

rising demand for food, mobility, housing and other goods and

services (Latouche, 2009; Jackson, 2011). The production of these

goods and services has led not only to growing pressure on the

atmosphere through emissions, but also to growing pressure on

land and water occasioned by their utilisation for production pur-

poses: ‘During the course of the 20th century, average resource use

per capita merely doubled,’ while ‘the global annual material

extraction increased […] by a factor of eight’ (UNEP, 2011, p. 17e18).

The use of the term Anthropocene e the Age of Humans e is apt to

describe this current era of global climate change and negative

human influences on ecological processes (Crutzen and Stoermer,

2000; Crutzen, 2002; Zalasiewicz et al., 2008).3 In ontological

terms, this signifies that humans are not only observers of the

Anthropocene but a central causal factor in the unfolding of reality:

a dominant ingredient of the planetary ecosystem.

For a large part of the scientific community, it is apparent that

ecosystems are now setting limits to the expansion of organised

human activity (Rockstro€m et al., 2009; Steffen et al., 2015). Un-

sustainable development has been enabled by medical and other

technical advances, by an unequal global exchange of energy and

other natural resources (Hornborg, 2014), particularly fossil fuels

(Wrigley, 2010), as well as a major growth in agriculture and animal

husbandry (Crutzen and Steffen, 2003). In terms of material limits,

non-renewable natural resources are running out and renewable

resources are being consumed at a faster rate than they can renew

(e.g., Lorek and Spangenberg, 2014). Concerning less tangible limits,

again, the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration has been

found to be too great and the global nitrogen cycle to be too dis-

rupted to ensure a safe operating space for humanity and other

species (Rockstro€m et al., 2009; Steffen et al., 2015). These esti-

mates concerning the state of the planet are certainly surrounded

by uncertainties, but the important point here is that if humans are

to steer away from the worst-case scenarios of collapsing ecosys-

tems and civilisations, human activities should be reorganised in

ecologically sustainable ways (Goodland and Daly, 1996).

In ontological terms, an ecologically substantive understanding

of ‘being’ in the Anthropocene epoch thus calls for a more realist

approach in organisation studies. Considering an organisation

merely as a socially constructed phenomenon might lead to over-

looking the material basis of all human activity in the ecosystem.

Any such exclusion of materiality and non-human objects from the

analysis is not only scientifically limited, but also highly dangerous

if it propounds a worldview where ecological destruction is not

considered problematic beyond human interests. Thus, without

doubt, ‘in certain instances it might be “appropriate”, “justifiable”

and eminently sensible to look for something other than human

language in order to appreciate the force of phenomena like human

3 It is important to note what Graham Harman (in Koot and Grootveld, 2015, p. 1)

expressed in a recent interview: “[the] Anthropocene Epoch is not an Anthropo-

centric Epoch, because it highlights the fragility of the human species rather than

human supremacy. This split between the Anthropocene and the Anthropocentric

compels us to recognise an important philosophical distinction that is seldom

acknowledged. Namely, the fact that humans are involved as ingredients in the

creation of some entity does not entail that the entity has no autonomous reality

apart from humans. The Anthropocene climate is generated by humans and inde-

pendently mysterious to us, and the same holds for other fields that have been

‘anthropocene’ from the start: human society, art, economics.”

responsibility and harm; simply recurring to discourse may often be

unsatisfactory’ (Holt and Mueller, 2011, p. 82). Moreover, denying

reality independent of the human subject is disturbingly anthro-

pocentric, which again is shown to be limited in its usefulness in

solving the complex ecological problems that organisations now

face (Purser et al., 1995).

Against this call for a new ontological frame, the next section

reviews and discusses the main premises of, and advances in,

ecological organisation literature. In the current study an ecological

organisation refers to those organisational orderings that take place

within the bioregional and global, and material boundaries of

ecosystems, and hence embrace the existence and prosperity of

humans, as well as other beings.

3. Organisations and the natural environment

In the Western tradition, the origins of ecological thought on

organising human action can be traced to influential North-

American texts such as Nature (Emerson, 1836), Walden (Thoreau,

1854), and Silent Spring (Carson, 1962). In Europe, important early

contributions to ecological thinking were Capital: Critique of Polit-

ical Economy (Marx, [1867] 1992) and The Technological Society

(Ellul, [1954] 1964). The authors of these far-sighted texts identified

and reported on a development whereby humans are becoming

increasingly distanced from the natural environment (i.e. non-

man-made objects), but are becoming a greater force in shaping

it (i.e. turning non-man-made objects into man-made ones). Most

of these seminal works explicitly acknowledged that a major reason

for such a rapid change in the humanenature relationship lies in

the advance of industrial and technological organisations.

Although these organisations of different shapes and sizes are

considered to be a ‘primary instrument by which humans impact

their natural environment’ (Shrivastava, 1994, p. 705), organisation

studies have paid relatively little attention to the human relation-

ship with the non-human world, and likewise, have largely over-

looked the threats evident in the Anthropocene. A rather small

group of scholars, however, have discussed ecological questions

related to organisations (e.g., Shrivastava, 1994; Jennings and

Zandbergen, 1995; Purser et al., 1995), some with a focus on the

economic organisation (Welford, 1995; Hart, 1995; Clair et al.,

1996), for over two decades (for a summary, see Gladwin et al.,

1995). More recently, continuations to these pioneering studies

have emerged (Valente, 2012; Gosling and Case, 2013; Ezzamel and

Willmott, 2014), but large-scale attention to ecological questions in

organisation theory is yet to come.

3.1. Embeddedness in the ecosystem

In the early 1990s, it became clear that the view offered by

mainstream organisation studies in analysing the surroundings of

organisations was denatured, narrow, and parochial due to its

emphasis on the economic, social, political, and technological as-

pects of organisational environments (Shrivastava, 1994). This

profound critique of the underlying assumptions of the field led to

an opportunity to reconceptualise the organisational environment

so that the significance of the non-human world was recognised in

explaining and understanding social activity. The centrality of na-

ture became obvious with the realisation that all individuals and

organisations, as well as sociocultural and political-economic sys-

tems, are embedded in the planetary ecosystem (Starik and Rands,

1995; Ezzamel and Willmott, 2014).

While ecological embeddedness applies to all societies, in-

stitutions and organisations, it also holds true on the individual

level. Whiteman and Cooper (2000, p. 1265) explain this as follows:

‘To be ecologically embedded as a manager is to personally identify

708

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

with the land, to adhere to beliefs of ecological respect, reciprocity,

and caretaking, to actively gather ecological information, and to be

physically located in the ecosystem’. The important finding from

the search for ecological organisations is that the degree of

ecological embeddedness is linked to managers' commitment to,

and engagement in an ecological praxis (Whiteman and Cooper,

2000). Thus, instead of making organisational decisions based on

mere technical knowledge, ‘which removes the knower from the

process of knowing’ (Purser et al., 1995, p. 1060), embeddedness is

related to situational knowledge that comprises first-hand expe-

rience of local ecosystems (Whiteman and Cooper, 2000). It goes

without saying that the premise of embeddedness radically

changes the manner in which the humanenature relationship is

perceived and organisations are managed (see Tilley, 2000).

3.2. Dependency on the ecosystem

Instead of presupposing nature is something distinct from hu-

manity and an infinite pool of resources for economic, or other

human activity, humankind has been forced to admit that ecosys-

tems are finite (Georgescu-Roegen, 1975; Daly, 1979) with material

boundaries (Rockstro€m et al., 2009; Steffen et al., 2015), and the

parts are dependent on the whole (Naess, [1974] 1989). As human

organisations ‘receive a number of inputs from various ecosystems,

including air, water, land, minerals, energy, animals, plants, and

microbial life’ (Starik and Rands, 1995, p. 917) that are critical to

their existence and success (Hart, 1995), the material dependency

of organisations on the planetary ecosystem became obvious. In

other words, the ecosphere provides the conditions essential to the

existence of humans and organisations (Shrivastava, 1995), as well

as those required to conduct economic or any other activity (Starik

and Rands, 1995).

In their study, Starik and Rands (1995, p. 928) demonstrated

how ‘organizations have environmentally oriented interactions

with other levels and systems, and [how] these are integrated in

[…] a web of relationships’. This insight signifies a shift from

atomistic and reductionist ideas to perceiving interconnectedness:

all actors in the ecosystems are connected (Valente, 2012; Newton,

2002). Many ecologically oriented organisation scholars have

employed the notion of interdependency to describe the relation-

ship between human organisations and the natural environment

(Newton, 2002; Valente, 2012; Ezzamel and Willmott, 2014), while

others have refrained from the use of the term (e.g., Starik and

Rands, 1995; Purser et al., 1995). According to Gladwin et al.

(1995), this disparity can be explained by a difference in ontolog-

ical stances. Ecocentric theorists assume that an entity (e.g., an

economic organisation) that is embedded in the ecosystem is

dependent on the ecosystem; however, the whole ecosystem is not

dependent on every single part of it. That is to say, life on the planet

may well continue without any human organisation, but a human

organisation cannot continue without the planet. However,

organised human actions undoubtedly have an effect on local and

global ecosystems as all objects are interconnected, and thus a

degree of interdependency can be argued, but to propose an

equivalent interdependency between objects would be a fallacy.

Hence, it is posited that certain objects (e.g., the Earth) are more

dependent on other objects (e.g., the sun) than others are (e.g., a

business organisation).

3.3. Value of the ecosystem

While anthropocentric organisation studies continue the con-

struction of an ontological hierarchy and a moral order, where

humans are above or apart from the ecosystem (Purser et al., 1995),

ecocentric theorists respectfully consider all human organisations

as subordinate to the planetary ecosystem. In ecocentrism, nature

as a whole is ‘more important than humans, as humans are simply

one animal species in the ecosystem’ (Ketola, 2008, p. 426). This

reverse in the construction of the ontological and moral hierarchy is

not favoured by most relational theorists (e.g., Newton, 2002), as

for them the world will ‘remain flat at all points’ (Latour, 1996, p.

240). Despite neglecting the difference in the relations between the

whole and its parts, a flat ontology is an important step away from

anthropocentrism, but it does not extend to ecocentrism, which

broadens the idea of community to include ecological wholes (such

as forests, wetlands, lakes and deserts) and also extends moral

value to ecological organisms (Purser et al., 1995). This broadened

view is radically different from the prevailing understandings of

value, where any non-instrumental value in the non-human world

is received with anxiety.

While anthropocentrism can also work as a basis for developing

an ecological conscience when motivated by concerns about

intergenerational equity and justice (Johnson, 1988, p. 610), major

problems arise from anthropocentrism for the ecological organi-

sation. The main problem with anthropocentrism is not that it is

human-centred (Purser et al., 1995, p. 1054), ‘or even that its pro-

ponents view nature instrumentally, but with proponents’ ten-

dency to view human beings as sole locus of value and measure of

all things' (Purser and Montuori, 1996, p. 611). A further problem

with the largely prevalent anthropocentrism in organisational

theory (Ezzamel and Willmott, 2014) and practice (Tilley, 2000) is

that it influences the code of ethics towards nature by essentially

denying that nature could have any inherent worth (Purser et al.,

1995). This, of course, has severe consequences for how humans

interact with the non-human world.

A few organisation scholars have lately started to raise questions

concerning the reflective dismissal of the anthropocentric ethos.

For instance, Wright et al. (2013, p. 647) ask: ‘how can we imagine

alternatives to our current path of ever escalating greenhouse gas

emissions and economic growth?’ Gosling and Case (2013, p. 716)

suggest that the social dreaming found in many traditional cultures

‘may offer us a route to discover meanings that are not accessible

within normal conscious rationality’, like a non-anthropocentric

moral frame. Similarly, Ezzamel and Willmott (2014, p. 2) suggest

that ‘unclosing the ethical register invites novel thinking about

established forms of knowledge, and thereby opens up new vistas

of theory development and empirical investigations’, and impor-

tantly for the present research, ‘attentiveness to the ethical register

is seen to invite radical reflection on a dominant, anthropocentric

value-orientation’ (Ezzamel and Willmott, 2014, p. 1). A desired

outcome of these reflections could be an ecocentric ontology and

an ethical frame that encompasses extended and deepened care for

humans as well as non-humans (cf. Naess, 1997).

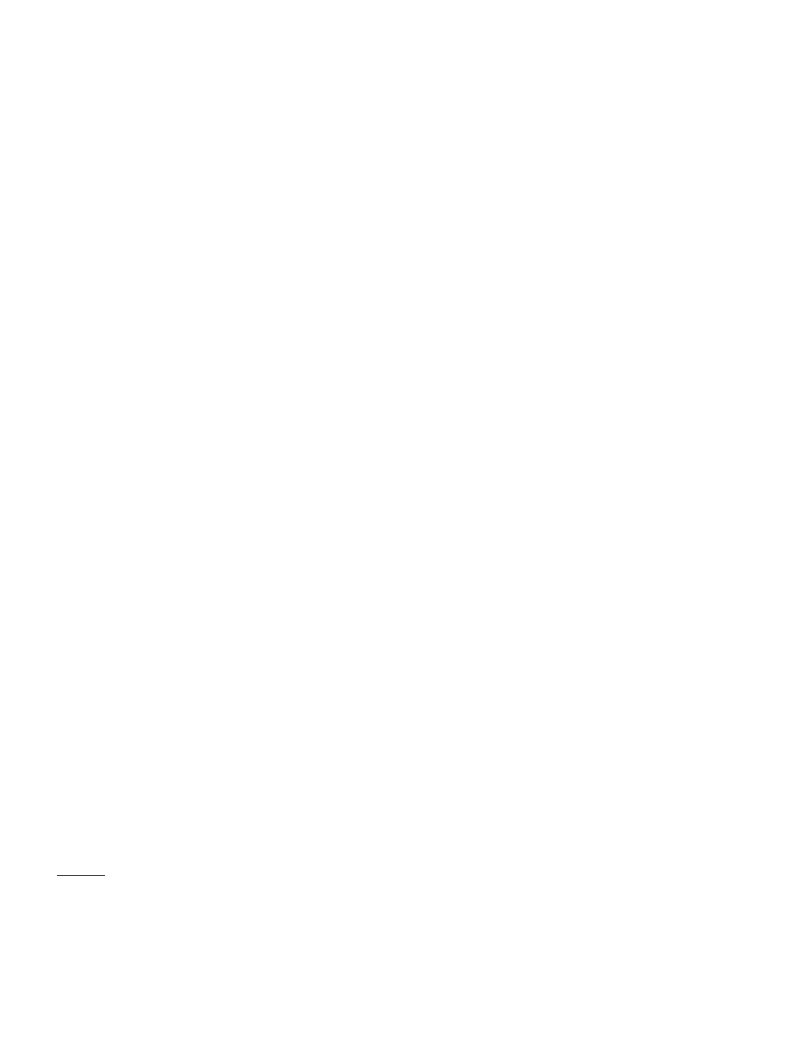

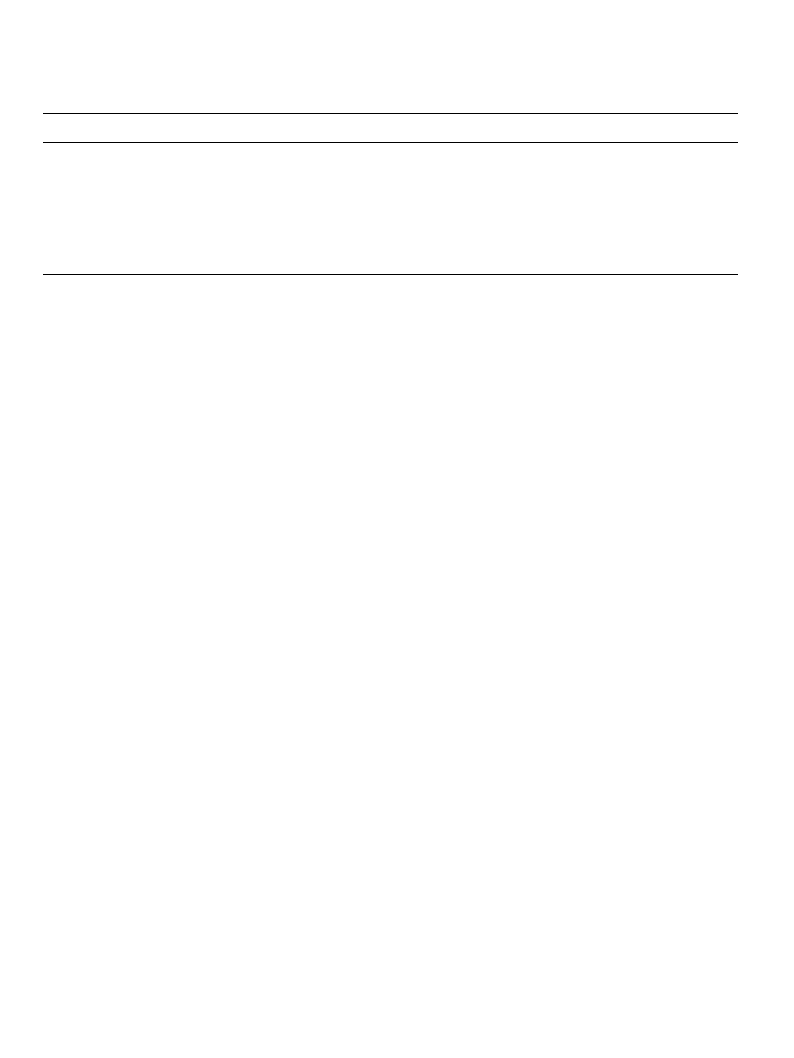

Table 1 summarises the central premises in the previous eco-

centric organisation literature and the conceptualisation of

humanenature relationships. Next, the paper proposes and dis-

cusses three essential qualities of all objects (mixing humans and

non-humans), derived from object-oriented and ecological phi-

losophies, to complement ecocentric theorising.

4. Essential qualities of objects for ecocentric theorising

As discussed above, previous studies on ecocentrism assume

organisational embeddedness in, and dependency on, the plane-

tary ecosystem (and also regional ecosystems), and enable a de-

parture from anthropocentrism. In terms of the humanenature

relationship, the premise of embeddedness of the ecosystem suggests

that human and man-made objects are embedded in non-human

and non-man-made objects, while the premise of dependency on

the ecosystem denotes that the human and man-made objects are

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

709

Table 1

The table illustrates the central premises in the ecocentric organisation literature and the consequent conceptualisations of humanenature relationships.

Central premise

Embeddedness in the ecosystem

Dependency on the ecosystem

Value of the ecosystem

Description of the

premise

Conceptualisation of

humanenature

relationships

Humans and their organisations are

embedded in ecosystems

Human and man-made objects are

embedded in non-human and non-man-

made objects

Humans and their organisations are

dependent on ecosystems

Human and man-made objects are

dependent on non-human and non-man-

made objects

Humans and their organisations are not the only source

of intrinsic value

In addition to human and man-made objects, non-

human and non-man-made objects can also hold

intrinsic value

dependent on non-human and non-man-made objects. Moreover,

with regard to the premise of value of the ecosystem, non-human

and non-man-made objects may also hold intrinsic value (Table 1).

But since ecocentric theory attracts accusations of dualism by

maintaining the analytical separation between humans and non-

humans, normativity through its calls for radical change, and an

unsatisfactory representation of nature (Newton, 2002), reima-

gining the ontological basis on ecocentric theorising is a worth-

while exercise.

4.1. Autonomy of objects

One way to avoid the often-problematized humanenature and

subjecteobject dualism in ecocentric thought (Guattari, 1989;

Newton, 2002) is to consider both human subjects and nature-

objects equally as objects among other objects. This radical idea

of object-oriented philosophy asserts that an enquiry cannot be

merely about the humans in the world, but must encompass other

things and objects (such as crude oil and the oceans), including

their fundamental relations and characteristics (Harman, 2002,

2009). So far many fields of research, including material culture

studies, have ignored factors like the achievements and impacts of

[non-human] living organisms (Ingold, 2012).

The distinction between the notions of things and objects

should be noted. For Ingold (2012), objects are completed forms

that stand over and against the perceiver and block further

movement. He rejects the notion of the object and takes materiality

for what it isemade and finishedeand turns to things to emphasise

the gatherings of materials in movement, as distinct from objects.

In Ingold's (2012) ecology of materials, a focus on the life of ma-

terials prioritises the processes of production over those of con-

sumption. Ingold thus insists on a radical distinction between

object and thing, drawing inspiration primarily from an influential

essay, entitled The Thing by Heidegger ([1971] 2001, p. 165e182).

For Harman (2009) again, all things are objects. Thus real objects

include those things without matter and relation. And the ‘real

objects […] withdraw from all human view and even from all re-

lations with each other’ (Harman (2009, p. 195), making the

essential qualities that this paper seeks to outline rather more a

matter of perception than actuality.

Another crucial difference is that while Ingold's (2011) largely

enquires into what things do, Harman (2009) seeks to understand

what objects are. For an ecological organisation, both tasks are

definitely important. In the present enquiry, however, the focus is

on the latter as the study seeks to complement ecocentric thought

with a set of essential qualities common to all objects. These qual-

ities are within the object itself, not to be found in its relation to

other objects (Harman, 2009).

Object-oriented philosophy differs in an important way from

the relational tradition (e.g., actor-network theorising by Latour

(1996, 2005), Johnson (1988)), as it does not consider objects as

fully defined by their relationships with other objects, but views

objects as entities that have a certain autonomy (Harman, 2002,

2009, see also Morin, [1994] 2008). In other words, when

compared to relational ontologies (e.g., Latour, 2005; Johnson,

1988), a distinctive feature of the object orientation is that

objects are not fully defined by their relationships with other ob-

jects, but have a degree of autonomy (Harman, 2002, 2009; Pierides

and Woodman, 2012). Harman (2009, p. 132), one of the key con-

tributors of speculative realism, explains objects and their relations

as follows:

[...] there are countless actors of different sizes and types,

constantly duelling and negotiating with each other. But objects

are not defined by their relations: instead they are what enter

into relations in the first place, and their allies can never fully

mine their ores. In Heideggerian terms, objects enter relations

but withdraw from them as well; objects are built of compo-

nents, but exceed those components. Things exist not in rela-

tion, but in a strange sort of vacuum from which they only partly

emerge into relation.

However, such autonomy is relative: ‘we will have to conceive

the system in its relation with its environment, in its relation with

time, in its relation finally with the observer/conceiver’ (Morin

[1977] 1992, p. 123). Human and man-made objects are

embedded in non-human and non-man-made objects. While the

existential phenomenological tradition of Heidegger ([1927] 1962)

is also inclined to consider objects as subordinate to human access

to them, the present study draws a non-anthropocentric ontolog-

ical line, where objects may not only exist but also thrive inde-

pendently of human perception and presence. This means that not

all objects depend on the subject (cf. Morin, [1994] 2008, p. 108),

and it is exactly because of this that the autonomy of objects is

highly relevant to the task of developing ecocentric theorising, as it

offers an exit from the anthropocentric and dualistic conceptual

frames of thought.

Humans should no longer speak of relations between people

and things, because people are things too (Ingold, 2012) but should

instead address everything as an object (Harman, 2009). The

importance of this post-human ontological turn is that when each

thing becomes an object, the material and non-human worlds, and

their relations with other objects, are also included in the analysis

(Pierides and Woodman, 2012). For an organisational analysis, this

signifies that ‘all objects and their relations matter’ (Pierides and

Woodman, 2012, p. 663), as they become full members of the

world community (Purser et al., 1995). This helps not only to ac-

count for the missing living (and non-living) organisms in the

scholarly analysis, but it also helps to erase the division between

ecological and social, and encourages people to view organisms as

parts of an intertwined process of becoming (Ingold and Palsson,

2013). Things are not mere objects of perception, but part of the

world-in-formation. In other words, rather than considering

humans as subjects and observers, becoming prompts us to view

humans as objects and participants (Ingold, 2011), as well as beings

with the capability to act as the observers of the observer (Morin,

[1994] 2008).

4.2. Intrinsicality of objects

The ethical register of theory building often tends to be over-

looked (Ezzamel and Willmott, 2014), but in this paper axiological

710

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

questions are considered an integral part of the ontological outline.

When independent non-human entities enter the equation, the

traditional anthropocentric assumptions are likely to be challenged

(Pierides and Woodman, 2012). However, the inclusion of non-

human objects in the analysis, although signalling that analysis is

taking the materiality of organisations seriously, does not mean

that an ecocentric ethos would automatically emerge. In fact, there

is a danger the post-human approaches develop into post-humane,

and perhaps violent, forms of actions unless the question of value is

explicitly addressed.

The second quality of objects adds depth to the ecocentric

organisation theory by suggesting that every object (including

agents such as ants or humans, structures such as buildings or re-

ligions, and processes such as thinking or life) has intrinsic value.

Following intrinsicalism (Gladwin et al., 1995), this quality of ob-

jects can be called intrinsicality. It is important to note here that the

intrinsicality of objects does not denote that all objects are proper,

good or right in the ethical sense. Nevertheless, by assuming this

quality is present, no object is considered merely an instrument for,

or means to, another object: instead objects become valued in

themselves. This signifies that non-human objects are valuable

independently of human objects (Naess, 1973, [1974] 1989) and

fosters the view of a human object as an object among others. In

contrast to the anthropocentric form of thought, ecocentric

scholars are able to escape the humanenature value dichotomy

through a premise of inherent equality and justice between all

objects.

According to Naess (1973), such broadened egalitarianism,

however, only works in principle. This is because ‘any realistic

praxis necessitates some killing, exploitation, and suppression’

(Naess, 1973, p. 95). Moreover, Naess ([1974] 1989, p. 95e96) ex-

plains the inclusive form of egalitarianism as follows:

The ecological field worker acquires a deep-seated respect, even

veneration, for ways and forms of life. He reaches an under-

standing from within, a kind of understanding that others

reserve for fellow men and for a narrow selection of ways and

forms of life. To the ecological field worker, the equal right to live

and blossom is an intuitively clear and obvious value axiom. Its

restriction to humans is an anthropocentrism with detrimental

effects upon the life quality of humans themselves. This quality

depends in part upon the deep pleasure and satisfaction we

receive from close partnership with other forms of life. The

attempt to ignore our dependence and to establish a master-

slave role has contributed to the alienation of man from himself.

In the above excerpt, Naess illustrates how the understanding of

the intrinsicality of objects relates to both human ethics and aes-

thetics, and how humans have a natural attraction to life. Ingold

(2011, p. 39), somewhat similarly, connects value and senses as

he states that ‘nothing, however, better illustrates the value placed

upon a sedentary perception of the world, mediated by the alleg-

edly superior senses of vision and hearing, and unimpeded by any

haptic or kinaesthetic sensation through the fee’ (Ingold, 2011, p.

39). That is, ethics and aesthetics are to a great extent intertwined

(Bateson, [1972] 2000; Kagan, 2010). While human objects have the

skill of aesthetic evaluation, which surely helps people to perceive

value in the non-human world, it does not denote that the value of

objects is dependent on humans assigning such value to objects. In

Naess' ([1974] 1989) terms, it instead refers to the human realisa-

tion of the inherent value in objects, and its consequences for

humans (e.g., in terms of aesthetic experiences). The quality of

intrinsicality hence contrasts with instrumentalism, which

views the value of objects only in relation to other objects.

While the value of objects largely unfolds in relation to others

(Bateson, [1972] 2000; Latour, 2005), intrinsicality posits that value

is a quality rather than a relation.

Perhaps somewhat paradoxically, humans might find them-

selves forced to leave the still largely prevalent anthropocentric

premises behind in order to save the human species while not

destroying others. In practice, this would first mean recognising the

human place within the complex ecosphere, then admitting

the limitations of human intellectual mechanisms in understanding

the complexity, and third, proceeding with precaution and respect

for all objects. But leaving anthropocentrism behind also necessi-

tates and implies an ecosophical language that turns the enquiry

away from human-centred discourse and practices based on the

instrumentalisation of objects. Fortunately, there is an increased

awareness of the connection between ‘scientific truth, on the one

hand, and beauty and morality, on the other: that if a man entertain

false opinions regarding his own nature [or arguably regarding any

nature], he will be led thereby to courses of action which will be in

some profound sense immoral and ugly’ (Bateson, [1972] 2000,

p. 265).

4.3. Uniqueness of objects

The rationale for considering everything as an object and

assuming all objects come with intrinsic value comes from the

realisation that an object's existence (and becoming) is always

exceptional. Objects, be they persons, flowers, events, sounds, or

other phenomena, disclose in a specific time and place a horizon

that is always unique. To ontologically arrive at this idea of

uniqueness, objects are considered to be irreducible to their con-

stituent parts (Naess, [1974] 1989; Harman, 2009). For example,

‘any attempt to undermine an object e in thought, or with a gun, or

with heat, or with the ravages of time or global warming e will not

get at the withdrawn essence of the object’ (Morton, 2011, p. 150). It

is crucial to note that objects cannot be rejected and reduced to

anything: objects are what objects are. This signifies that objects

are irreplaceable (Naess, [1974] 1989) and non-substitutable (Daly,

1979).

The substitutability of objects is often assumed in economics

and reductionist ecological studies (Heikkurinen and Bonnedahl,

2013). However, objects such as natural and human capital are

not substitutable but only complementary (Daly, 1979), if even that.

For an ecological enquiry, the non-substitutability factor is of vital

importance, as man-made objects such as thoughts, machines and

economic processes cannot substitute for non-man-made objects

(such as stars, forests and species), and vice versa. Daly (1996, p. 76)

explains this non-substitutability vividly:

One way to make an argument is to assume the opposite and

show that it is absurd. If man-made capital were a near perfect

substitute for natural capital, then natural capital would be a

near perfect substitute for man-made capital. But if so, there

would have been no reason to accumulate man-made capital in

the first place, since we were endowed by nature with a near

perfect substitute. But historically we did accumulate

man-made capital e precisely because it is complementary to

natural capital. [...] Man-made capital is itself a physical trans-

formation of natural resources which come from natural capital.

Therefore, producing more of the alleged substitute (man-made

capital), physically requires more of the very thing being

substituted for (natural capital) e the defining condition of

complementarity!

This paper thus assumes that the essence and relations of all

objects are at best complementary rather than substitutable. For

instance, it is common sense that objects such as sawmills cannot

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

711

substitute for stocks of wood (Daly, 1979, 1992), and the other way

around, which necessitates rethinking the role of objects and the

current industrial practices that transform objects at an increasing

pace. And what follows the irreducibility and non-substitutability

of objects is the quality of uniqueness. The uniqueness of objects

directs scholars away from any reductionist mode of organisation

studies towards more inclusive frameworks (see e.g., Purser et al.,

1995; Reed, 2005; Lozano, 2008), and guides them to proceed

with caution when organising and managing objects, as well as

encouraging respect for the exceptionality of all objects.

5. Discussion on object-oriented ecosophy

As the essential qualities of objects in this study are derived

from object-oriented philosophy (Harman, 2002, 2009) and

ecological philosophy (Naess, 1973, [1974] 1989). The three-point

outline could be labelled object-oriented ecosophy. In the

following, the reasons why the emergence of ontological discussion

in ecological studies could be valuable, and the implications of the

outline for ecological theory and practice are discussed.

Autonomy is very relevant to ecocentric theory, as the ‘notion of

autonomy does not correspond to the old notion of freedom, which

was to a certain extent immaterial and detached from constraints

and physical contingencies’ (Morin, [1994] 2008, p. 69). According

to Morin ([1994] 2008, p. 69), ‘it is, on the contrary, a notion closely

linked to that of dependency, and the latter is inseparable from the

notion of self-organization’. That is, objects are emergent, a quality

that might be measured or registered by their relationships, ‘but

can never be fully defined by them’ (Harman, 2009, p. 143). This

quality enables scholars to describe and prescribe different

agencies for objects, yet keep them embedded in the ecosystem. For

example, it is commonly accepted that without a degree of au-

tonomy, no moral responsibility for sustainability (or any other

end) can be assigned or assumed. Further, when ethics is consid-

ered an essential element in achieving sustainability (de Paula and

Calavanti, 2000), then moral agency is needed to enable, or at least

support, the change. Thus, it is vital that the degree of autonomy

can be used to explain different agencies in scientific enquiry

instead of claiming full interdependency between objects, which

leaves little or no room for moral agency (or quality) in objects (see

e.g., Latour, 2002).

However, without a degree of autonomy, objects lack the ability

to act and to explore their full potential. The idea of the degree of

autonomy urges researchers and practitioners of ecological

organising to gradually move from questions such as ‘how are ob-

jects related to each other?’ to more practically relevant questions

such as ‘what are the implications if all objects are assumed to have

agency beyond their relations to other objects, and thus also

beyond human comprehension?’ Consequently, humans respon-

sible for organisations become better equipped to appreciate the

idea that they need not only to understand how objects are related

to each other in the production system, but also to understand the

capability of all objects to surprise the production system with their

inherent agency.

While a degree of autonomy is an essential part of object-

oriented ecosophy, it becomes ecologically strong only when

complemented with the other two qualities. By realising that ob-

jects are not substitutes for other objects and cannot be reduced to

any other object, the quality of uniqueness becomes accessible, and

when objects disclose uniquely in a specific time and place horizon,

it calls for the theory and practice to respect and embrace their

exceptionality, including transformation, change, decomposition

and death, that is, also the vulnerability and fatality of objects.

This quality should prompt both researchers and managers to

scrutinise the ethics of depriving any object of its agency or

existence. The focal implication for organisational practices would

thus be to proceed with caution when organising and managing

objects. Assuming objects, such as people, animals, forests, chairs,

activities, ideas and sounds, are entities that are irreducible and

non-substitutable invites us to consider that objects possess not

only instrumental value dependent on other objects but, most

importantly, value in themselves. This kind of inherent value

translates to the quality of intrinsicality. The main implication of

intrinsicality for organisational enquiry is that it releases objects

from the instrumental rationale, and signifies the right of objects to

disclose on their own, that is, to live and flourish.

Moreover, object-oriented ecosophy and the quality of intrinsi-

cality hold crucial instrumental value for an enquiry into ecological

organisation. In other words, if it is to imagine, practice, and

manage those organisational orderings that are to stay within

material boundaries, humankind has to embrace the existence of all

objects for their own sake and therefore to admit their intrinsic

value. In the light of anthropocentric thought, this rationale might

seem paradoxical for two reasons. First, although instrumentality

and intrinsicality usually (if not always) coexist in an object, they

are often thought of in dualistic terms, as opposites. Nevertheless,

there is no reason to think that they could not coexist in an object.

Second, the rationale behind intrinsicality is supported with an

instrumental logic dictating that if people are to imagine and

practice those ecological orderings, they need to embrace the ex-

istence of all objects for their own sake. Again, teleological argu-

mentation (which claims something for the sake of an end) can be

considered to conflict with the idea of intrinsicality only if intrin-

sicality is presumed to be something that is antithetical to

instrumentality.

An ecological turn based on these ecocentric premises repre-

sents a radical departure from mainstream organisation theory and

shallow environmental turns within and around it. There is little

doubt that importing ecological concepts into organisation theory

will involve a major reorientation (Purser et al., 1995), which will

take time. It is, however, rather encouraging to note that ecologi-

cally advanced ontological turns are occurring in sociology (Urry,

2011) and economics (Spash, 2012). However, the question re-

mains whether ecocentric theory must still be developed on the

outskirts of contemporary organisation theory, or whether society

will open up and begin taking the threats of the Anthropocene

seriously.

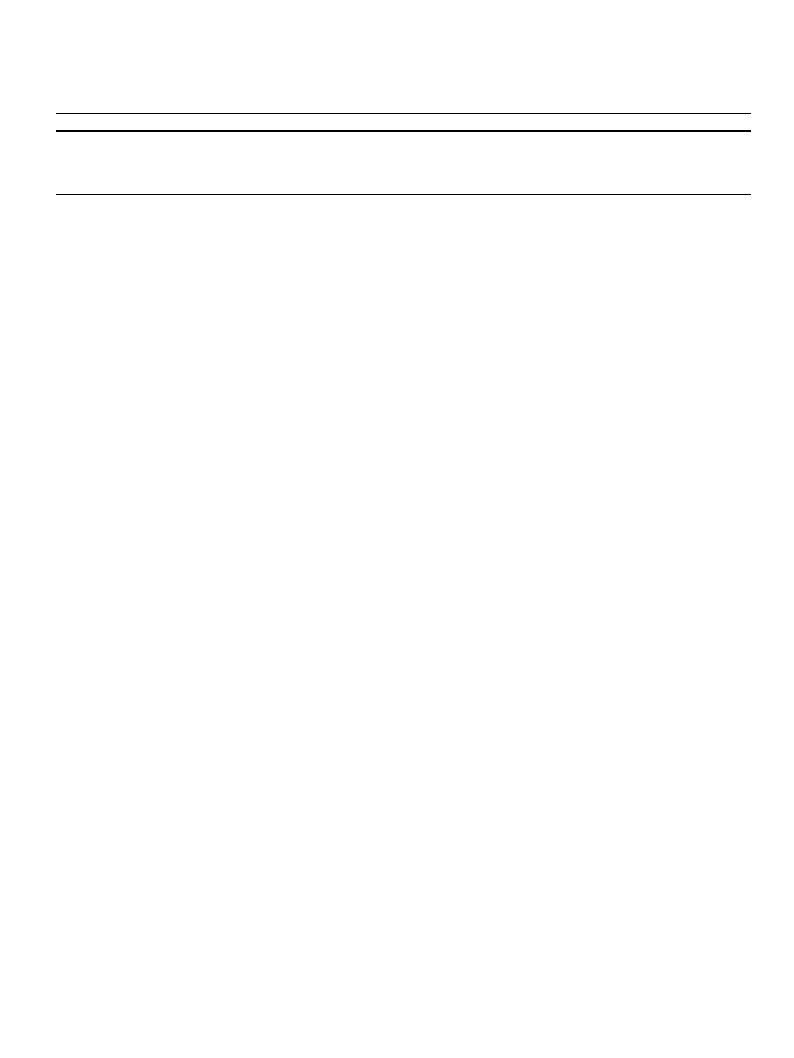

Be that as it may, the paper considers that given the proposed

set of essential qualities of objects (see Table 2 for a summary),

organisational scholars would be willing and able to build practi-

cally relevant and ecologically advanced theories that consider the

non-human and material realms as integral parts of the analysis

without falling into the trap of dualism or unsatisfactory repre-

sentations of nature (see Newton, 2002; Hanna, 1996). Further-

more, such a descriptive outline could offer a response to the

critique of ecocentric theorising being just normative ecological

ordering that is doomed to fail, since it is merely an ontology that is

not considered to be over-encompassing or forced on anyone. It

may or may not be realised.

The ontological outline suggested in this paper escapes the

kind of realism where reality is objective and accessible to

humans objectively, as well as the kind of antirealism where

realities are socially constructed and always relative to subjective

human interpretation. The philosophical position of the present

study decentralises the human subject by assuming that reality

may be objective but knowledge about it only subjective. A sig-

nificant motivation for leaving the antirealism behind comes from

noting that these positions are not equipped to face the ongoing

ecological catastrophe (Bryant et al., 2011) that is the

Anthropocene.

712

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

Table 2

The table illustrates the essential qualities of objects and the implications to ecocentric theory and practice.

Quality of

objects

Autonomy

Intrinsicality

Uniqueness

Underlying

assumption

and key

literature

Description of

the quality

Theoretical

implication

Practical

implication

Objects are not fully defined by their relationships Objects are not considered to be merely instruments Objects are irreducible (Harman, 2002; Naess,

with other objects but have a degree of autonomy for, or means to, other objects but have value in [1974] 1989) and non-substitutable (Daly,

(Harman, 2002, 2009)

themselves (Naess, [1974] 1989)

1979)

All objects have a degree of autonomy

All objects are ends in themselves

All objects are

unique

Some objects are more autonomous than others No object should be treated merely as a means

Objects disclose in a specific time and place

horizon

Autonomy can be used to explain and assign

Intrinsicality releases objects from instrumental Uniqueness suggests precaution in organising

different (moral) agencies, i.e. objects' ability to act rationale, and signifies the right of objects to disclose activities and the conservation of ecosystems,

and explore their fullest potential

on their own; to live and blossom

as well as embracing the diversity of objects

It has been argued that if humans are to move to ecocentric

ontologies, they need more than a popular, observer-style under-

standing of ecology (Purser et al., 1995, also Morin, [1994] 2008).

Thus, in addition to embedding social actors in the ecosystem

(Whiteman and Cooper, 2000), recognising the interconnectedness

of all actors in that ecosystem, (Valente, 2012; Newton, 2002), and

advancing ethical considerations to encompass the non-human

world (Gosling and Case, 2013; Ezzamel and Willmott, 2014), ob-

jects would have a metaphysical footing of their own. ‘Objects exist

as autonomous units, but they also exist in conjunction with their

qualities, accidents, relations, and movements without being

reducible to these’ (Harman, 2009, p. 156). Becoming aware of the

qualities of objects necessitates engaging with the objects in a

direct and open manner, that is, encountering them without

instrumentalisation.

While the popular knowledge of objects is a sort of ‘spectator

epistemology that assumes that by withdrawing from participation

in the world, objects can be described and represented as if there

were no subjective observer (with values, feelings, etc.)’ (Purser

et al., 1995, p. 1059), the situational knowing that object-oriented

ecosophy hints at does not exclude subjectivity from objects or

values from ontology. Subjective sentiments such as values in fact

play a central role in the ecocentric ontology that is not dominated

by, or limited to, instrumental rationality (Purser et al., 1995).

Furthermore, several scholars have pondered whether the

groundlessness that characterises modern living is preventing

humans from developing deeper understandings of, and relations

to, objects (Heidegger, [1945] 2010; von Wright, 1978; Ingold,

2011). If so, then re-establishing grounds for time- and space-

sensitive knowing by anchoring practices in closer proximity

would be warranted.

6. Conclusions

The current research indicates that the new geological era of the

Anthropocene calls for a new ontology to guide the organisation of

human activities. The ontology proposed here takes a realist and

ecocentric turn to avoid the pitfalls of the antirealist and anthro-

pocentric approaches. Drawing from object-oriented (Harman,

2002, 2009) and ecological philosophies (Naess, 1973, [1974]

1989), the study proposes three essential qualities common to all

objects, namely autonomy, intrinsicality, and uniqueness. The onto-

logical outline formed by these three points responds to the

critique of ecocentric organisation studies. It demonstrates how to

avoid the humanenature dualism by considering each thing an

object while still arriving at an ecologically relevant view of reality.

The outline labelled object-oriented ecosophy facilitates

explaining and assigning different agencies depending on the de-

gree of autonomy, the release of objects from an instrumental

ethical rationale, and the reasoning behind exercising caution

around objects and encouraging their conservation. When the

suggested qualities are assumed in organising activities, objects

become capable of unfolding in their own ways (autonomy), acquire

rights to exist on their own (intrinsicality), and are respected for

what they are (uniqueness).

The current study's main contribution to ecological organisation

theory and practice is to provide a framework for reimagining the

objecteobject relations central to the peaceful coexistence of objects.

This includes the reconsideration of the relationship between

humans and the natural environment, and the consequent need to

reorganise production activity in a manner that embraces the di-

versity of objects. The ongoing growth of human economic activity

has had a severe impact in terms of reducing the diversity of life,

leading to a call for a ‘degrowth society’ (Daly, 1996; Latouche, 2009;

Jackson, 2011). Object-oriented ecosophy offers an ontological outline

for this transition. If the suggested qualities of objects are perceived

in organisations, then organisations are likely to radically reduce the

instrumentalisation of objects, including the use of so-called natural

resources or capital. In practice, the outline is to signify a decrease in

the rate of material throughput needed to reach sustainability

(Georgescu-Roegen,1975; Daly,1996) and an ecological organisation.

The limitations of this paper relate to the conceptual nature of

the study. Whether the proposed ontological outline is actually

suited to promote sustainability and would lead to desirable

changes in organisational practice is a question that must be

explored empirically. Future studies might therefore test the model

in organisations, and encompass further theoretical work on the

qualities and activities of objects.

Funding

The research undertaken by Pasi Heikkurinen, Jenny Rinkinen,

Kristoffer Wilen, and Toni Ruuska received no specific grant from

any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit

sectors. The work of Timo Ja€rvensivu was funded by a Tekes (the

Finnish Funding Agency for Innovation) research project ‘Ener-

gizing Urban Ecosystems’.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at two interna-

tional colloquia: (1) the Finnish Society for Environmental Social

Science (YHYS), sub-theme ‘Methods of Framing in Environmental

Policy and Sustainable Consumption Research’ in November 2013,

and (2) the European Group for Organizational Studies (EGOS), sub-

theme ‘Things Ain't What They Used to Be: Objects, Relations,

Materiality’ in June 2014. We wish to thank the organisers and

participants of these events for their valuable comments. We also

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

713

want to express our deepest gratitude to the editorial team and the

four anonymous reviewers of this journal for their encouragement

and critical remarks.

References

Ayres, R., van den Berrgh, J., Gowdy, J., 2001. Strong versus weak sustainability.

Environ. Ethics 23, 155e168.

Barnosky, A.D., Matzke, N., Tomiya, S., Wogan, G.O.U., Swartz, B., Quental, T.B.,

Marshall, C., McGuire, J.L., Lindsey, E.L., Maguire, K.C., Mersey, B., Ferrer, E.A.,

2011. Has the Earth's sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 471, 51e57.

Barnosky, A.D., Hadly, E.A., Bascompte, J., Berlow, E.L., Brown, J.H., Fortelius, M.,

Getz, W.M., Harte, J., Hastings, A., Marquet, P.A., Martinez, N.D., Mooers, A.,

Roopnarine, P., Vermeij, G., Williams, G.W., Gillespie, R., Kitzes, J., Marshall, C.,

Matzke, N., Mindell, D.P., Revilla, E., Smith, A.B., 2012. Approaching a state shift

in Earth's biosphere. Nature 486, 52e58.

Bateson, G., 2000 [1972]. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. University of Chicago Press,

New York.

Beckerman, W., 1995. How would you like your ‘sustainability’, sir? Weak or strong?

A reply to my critics. Environ. Values 4, 167e179.

Bryant, L., Srnicek, N., Harman, G., 2011. The speculative turn: continental materi-

alism and realism. re.press, Melbourne.

Carson, R., 1962. Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P.R., Barnosky, A.D., García, A., Pringle, R.M., Palmer, T.M., 2015.

Accelerated modern humaneinduced species losses: entering the sixth mass

extinction. Sci. Adv. 1, e1400253.

Clair, J.A., Milliman, J., Whelan, K.S., 1996. Toward an environmentally sensitive

ecophilosophy for business management. Organ. Environ. 9, 289e326.

Crutzen, P.J., 2002. Geology of mankind. Nature 415, 23‒23.

Crutzen, P.J., Steffen, W., 2003. How long have we been in the Anthropocene era?

Clim. Change 61, 251e257.

Crutzen, P.J., Stoermer, E.F., 2000. The Anthropocene. Glob. Change Newsl. 41, 17e18.

Cunha, M.P.e., Rego, A., Vieira da Cunha, J., 2008. Ecocentric management: an up-

date. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 15, 311e321.

Daly, H.E., 1979. Entropy, growth and the political economy of scarcity. In:

Smith, V.K. (Ed.), Scarcity and Growth Reconsidered. John Hopkins U. Press,

Baltimore, pp. 67e94.

Daly, H.E., 1992. Steady-state Economics. Earthscan, London.

Daly, H.E., 1996. Beyond Growth. Beacon Press, Boston.

de Paula, G.O., Cavalcanti, R.N., 2000. Ethics: essence for sustainability. J. Clean.

Product. 8, 109e117.

Ellul, J., 1964 [1954]. The Technological Society (La technique ou l'enjeu du siecle)

(translated by Merton, R.K.). Vintage Books, New York.

Emerson, R., 1836. Nature. James Munroe and Company, Boston.

Ezzamel, M., Willmott, H., 2014. Registering ‘the ethical’ in organization theory

formation: towards the disclosure of an ‘invisible force’. Organ. Stud. 35,

1013e1039.

Fleetwood, S., 2005. Ontology in organization and management studies: a critical

realist perspective. Organization 12, 197e222.

Georgescu-Roegen, N., 1975. Energy and economic myths. South. Econ. J. 41,

347e381.

Gladwin, T.N., Kennelly, J.J., Krause, T.S., 1995. Shifting paradigms for sustainable

development: implications for management theory and research. Acad. Manag.

Rev. 20, 874e907.

Goodland, R., Daly, H., 1996. Environmental sustainability: universal and non-

negotiable. Ecol. Appl. 6, 1002e1017.

Gosling, J., Case, P., 2013. Social dreaming and ecocentric ethics: sources of non-

rational insight in the face of climate change catastrophe. Organization 20,

705e721.

Guattari, F., 1989. The three ecologies. New Form. 8, 131e147.

Hanna, M.D., 1996. Environmentally responsible managerial behavior: is ecocen-

trism a prerequisite. Acad. Manag. Rev. 21, 796e799.

Harman, G., 2002. Tool-being: Heidegger and the metaphysics of objects. Open

Court Publishing, Chicago.

Harman, G., 2009. Prince of Networks: Bruno Latour and Metaphysics. re.press,

Prahran.

Hart, S.L., 1995. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20,

986e1014.

Heidegger, M., 1962 [1927]. Being and Time (Sein und Zeit) (translated by Mac-

qarrie, J., Robinson, E.). Blackwell Publishing, Malden.

Heidegger, M., 2001 [1971]. Poetry, Language, Thought (Das Gegeneinander von

Welt und Erde ist ein Streit) (translated by Hofstadter, A.). Harper & Row, New

York.

Heidegger, M., 2010 [1945] (Translated by Davis, B.W.). Country Path Conversations

[Gesamtausgabe, vol. 77]. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Heikkurinen, P., Bonnedahl, K.J., 2013. Corporate responsibility for sustainable

development: a review and conceptual comparison of market- and stakeholder-

oriented strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 43, 191e198.

Holt, R., Mueller, F., 2011. Wittgenstein, Heidegger and drawing lines in organization

studies. Organ. Stud. 32, 67e84.

Hornborg, A., 2014. Ecological economics, marxism, and technological progress:

some explorations of the conceptual foundations of theories of ecologically

unequal exchange. Ecol. Econ. 105, 11e18.

Ingold, T., 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description.

Taylor & Francis, New York.

Ingold, T., 2012. Toward an ecology of materials. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 41, 427e442.

Ingold, T., Palsson, G., 2013. Biosocial Becomings: Integrating Social and Biological

Anthropology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), 2014. 5th Assessment Report.

Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaption, and Vulnerability.

Jackson, T., 2011. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet.

Earthscan, New York.

Jennings, P.D., Zandbergen, P.A., 1995. Ecologically sustainable organizations: an

institutional approach. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 1015e1052.

Johnson, J., 1988. Mixing humans and nonhumans together: the sociology of a door-

closer. Soc. Probl. 35, 298e310.

Kagan, S., 2010. Cultures of sustainability and the aesthetics of the pattern that

connects. Futures 42, 1094e1101.

Ketola, T., 2008. A holistic corporate responsibility model: integrating values, dis-

courses and actions. J. Bus. Ethics 80, 419e435.

Koot, L., Grootveld, M., 2015. Interview with Graham Harman on the Anthropocene.

In: Sonic Acts Research Series #10, Anthropocene Objects, Art and Politics.

Available at: http://www.sonicacts.com/portal/anthropocene-objects-art-and-

politics-1.

Latouche, S., 2009. Farewell to Growth. Polity Press, Cambridge.

Latour, B., 1996. On interobjectivity. Mind Cult. Act. 3, 228e245.

Latour, B., 2002. Morality and technology: the end of the means (translated by

Venn, C.). Theory Cult. Soc. 19, 247e260.

Latour, B., 2005. Reassembling the Social-an Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory.

Reassembling the Social-an Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford

University Press, Oxford.

Lorek, S., Spangenberg, J.H., 2014. Sustainable consumption within a sustainable

economyebeyond green growth and green economies. J. Clean. Prod. 63,

33e44.

Lozano, R., 2008. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 16,

1838e1846.

MA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment), 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-

being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington.

Ma€ki, U., 2008. Scientific realism and ontology. New Palgrave Dict. Econ. 7, 334e341.

Martinez-Alier, J., 2014. Environmentalism, currents of. In: D'Alisa, G., Demaria, F.,

Kallis, G. (Eds.), Degrowth: a Vocabulary for a New Era. Routledge, London,

pp. 37e40.

Marx, K., 1992 [1867]. Capital Volume 1: A Critique of Political Economy (Das

Kapital: Kritik der politischen O€ konomie) (translated by Fowkes, B.). Penguin

Classics, New York.

Morin, E., 1992 [1977]. Method: towards a Study of Humankind: La nature de la

nature (translated by Belanger, J.L.R.). In: The Nature of Nature: La nature de la

nature, vol. 1. Peter Lang, New York.

Morin, E., 2008 [1994]. On Complexity (La complexite humaine) (translated by

Postel, R., Kelly, S.M.). Hampton Press, Cresskill.

Morton, T., 2011. Objects as temporary autonomous zones. Continent 1, 149e155.

Naess, A., 1973. The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement. A sum-

mary. Inq. Interdiscip. J. Philos. 16, 95e100.

Naess, A., 1989 [1974]. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle (Økologi, samfunn og

livsstil: utkast til en økosofi) (translated by Rothenberg, D.). Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, Camridge.

Naess, A., 1997. Sustainable development and the deep ecology movement. In:

Baker, S., Kousis, M., Richardson, D., Young, S. (Eds.), The Politics of Sustainable

Development: Theory, Policy and Practice within the European Union. Rout-

ledge, London, pp. 61e71.

NASA/GISS (National Aeronautics and Space Administration/Goddard Institute for

Space Studies), 2014. Climate Data. Available at: data.giss.nasa.gov.

Newton, T.J., 2002. Creating the new ecological order? Elias and actor-network

theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 27, 523e540.

Orlikowski, W.J., 2010. The sociomateriality of organisational life: considering

technology in management research. Camb. J. Econ. 34, 125e141.

Pearce, D.W., Atkinson, G.D., 1993. Capital theory and the measurement of sus-

tainable development: an indicator of ‘weak’ sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 8,

103e108.

Pierides, D., Woodman, D., 2012. Object-oriented sociology and organizing in the

face of emergency: Bruno Latour, Graham Harman and the material turn. Br. J.

Sociol. 63, 662e679.

Purser, R.E., Montuori, A., 1996. Ecocentrism is in the eye of the beholder. Acad.

Manag. Rev. 21, 611e613.

Purser, R.E., Park, C., Montuori, A., 1995. Limits to anthropocentrism: toward an

ecocentric organization paradigm? Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 1053e1089.

Reed, M., 2005. Reflections on the ‘realist turn’ in organization and management

studies. J. Manag. Stud. 42, 1621e1644.

Rockstro€m, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å, Chapin III, F.S., Lambin, E.F.,

Lenton, T.M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H.J., Nykvist, B., de Wit, C.A.,

Hughes, T., van der Leeuw, S., Rodhe, H., So€rlin, S., Snyder, P.K., Costanza, R.,

Svedin, U., Falkenmark, M., Karlberg, L., Corell, R.W., Fabry, V.J., Hansen, J.,

Walker, B., Liverman, D., Richardson, K., Crutzen, P., Foley, J.A., 2009. A safe

operating space for humanity. Nature 461, 472e475.

Schw€agerl, C., 2013. Anthropo-scene #1: from Rocks to Thoughts. Next Nature, April

29, 2013. Available at: https://www.nextnature.net/2013/04/anthropo-scene-1-

from-rocks-to-thoughts/.

714

P. Heikkurinen et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 113 (2016) 705e714

Shrivastava, P., 1994. Castrated environment: greening organizational studies. Or-

gan. Stud. 15, 705e726.

Shrivastava, P., 1995. The role of corporations in achieving ecological sustainability.

Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 936e960.

Spash, C.L., 2012. New foundations for ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 77, 36e47.

Starik, M., 1995. Should trees have managerial standing? Toward stakeholder status

for non-human nature. J. Bus. Ethics 14, 207e217.

Starik, M., Rands, G.P., 1995. Weaving an integrated web: multilevel and multi-

system perspectives of ecologically sustainable organizations. Acad. Manag.

Rev. 20, 908e935.

Steffen, W., Crutzen, P.J., McNeill, J.R., 2007. The Anthropocene: are humans now

overwhelming the great forces of nature. Ambio J. Hum. Environ. 36, 614e621.

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockstro€m, J., Cornell, S.E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E.M.,

Biggs, R., Carpenter, S.R., de Vries, W., de Wit, C.A., Folke, C., Gerten, D.,

Heinke, J., Mace, G.M., Persson, L.M., Ramanathan, V., Reyers, B., So€rlin, S., 2015.

Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet.

Science 347, 1259855.

Thoreau, H.D., 1854. Walden. Ticknor and Fields, Boston.

Tilley, F., 2000. Small firm environmental ethics: how deep do they go? Bus. Ethics

Eur. Rev. 9, 31e41.

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), 2011. Decoupling Natural

Resource Use and Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth. A report of

the working group on decoupling to the International Resource Panel. English

summary. Retrieved from. http://www.unep.org/resourcepanel/Portals/24102/

PDFs/DecouplingENGSummary.pdf.

Urry, J., 2011. Climate Change and Society. Polity Press, Cambridge.

Valente, M., 2012. Theorizing firm adoption of sustaincentrism. Organ. Stud. 33,

563e591.

von Wright, G.H., 1978. Humanismen Som Livshållning (Humanism as an Approach

to Life). Månpocket, Stockholm.

Welford, R., 1995. Environmental Strategy and Sustainable Development: the

Corporate Challenge for the Twenty-first Century. Routledge, London.

Whiteman, G., Cooper, W.H., 2000. Ecological embeddedness. Acad. Manag. J. 43,

1265e1282.

Wright, C., Nyberg, D., De Cock, C., Whiteman, G., 2013. Future imaginings: orga-

nizing in response to climate change. Organization 20, 647e658.

Wrigley, E.A., 2010. Energy and the English Industrial Revolution. Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, Cambridge.

Zalasiewicza, J., Williams, M., Smith, A., Barry, T.L., Coe, A.L., Bown, P.R., Brenchley, P.,

Cantrill, D., Gale, A., Gibbard, P., Gregory, F.J., Hounslow, M.W., Kerr, A.C.,

Pearson, P., Knox, R., Powell, J., Waters, C., Marshall, J., Oates, M., Rawson, P.,

Stone, P., 2008. Are we now living in the Anthropocene? GSA Today 18, 4e8.