WITH THE EARTH IN MIND: ECOLOGICAL GRIEF

IN THE CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN NOVEL

Ashley E. Reis

Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS

May 2016

APPROVED:

Ian Finseth, Committee Chair

Priscilla Ybarra, Committee Member

Jacqueline Foertsch, Committee Member

Robert Upchurch, Chair of the Department

of English

Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate

School

Reis, Ashley E. With the Earth in Mind: Ecological Grief in the Contemporary American

Novel. Doctor of Philosophy (English), May 2016, 233 pp., references, 260 titles.

With the Earth in Mind responds to some of the most cutting-edge research in the field of

ecocriticism, which centers on ecological loss and the grief that ensues. Ecocritics argue that

ecological objects of loss abound--for instance, species are disappearing and landscapes are

becoming increasingly compromised--and yet, such loss is often deemed "ungrievable." While

humans regularly grieve human losses, we understand very little about how to genuinely grieve

the loss of nonhuman being, natural environments, and ecological processes. My dissertation

calls attention to our society's tendency to participate in superficial nature-nostalgia, rather than

active and engaged environmental mourning, and ultimately activism. Herein, I investigate how

an array of postwar and contemporary American novels represent a complex relationship

between environmental degradation and mental illness. Literature, I suggest, is crucial to

investigations of this problem because it can reveal the human consequences of ecological loss in

a way that is unavailable to political, philosophical, scientific, and even psychological discourse.

Copyright 2016

by

Ashley E. Reis

Li

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My acknowledgements must begin with Ann Pancake, whose Strange as This Weather

Has Been found me in a bookstore somewhere between Oregon, Wyoming, and Texas, and

revealed to me the palpable and very real nature of ecological grief at a most formative moment

in my academic life. I cannot thank Ann enough for forging a relationship with me; expressing

genuine interest in and offering earnest support for my project; and providing reminders through

her fiction and direct words to me of this project’s exigency.

Additionally, I am indebted to my generous and encouraging advisor, Dr. Ian Finseth, for

his unwavering support of my project from its earliest inception. Dr. Finseth’s enthusiasm for my

ideas and his confidence in my ability to bring them to fruition enabled me to make my way

through this process with as much finesse as one could ever hope. Dr. Priscilla Ybarra, too, gave

generously of her time, formally and informally, as a thoughtful critic and supportive mentor.

She was present for the early conference presentations of the ideas I advance in this dissertation,

and provided invaluable feedback, guidance, and, above all, inspiration. Dr. Jacqueline Foertsch,

who has been an influential presence since day one of my graduate career at UNT, has played an

immeasurable role in inciting me to be the best version of my academic self possible. I am

grateful to have spent three graduate seminars learning from her; for her first-rate direction and

guidance during my comprehensive exams; and for her unrelenting insistence that I step up to a

bar I didn’t know I could possibly reach. I would also like to thank Dr. Stephanie Hawkins, who

also dedicated her time and counsel as a member of my comprehensive exam super-committee.

And, of course, I am ever grateful to my canine sidekick Banjo, who, despite the long

hours writing and researching (typically at Banter Bistro—thank you to my Denton family

members Ellen and Kat), kept me tethered firmly and meaningfully to the earth all along.

iLi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................LLL

INTRODUCTION: “WITH THE EARTH IN MIND: ECOLOGICAL GRIEF IN THE

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN NOVEL”................................................................................ Y

CHAPTER : THE WOUNDS OF DISLOCATION: NATIVE AMERICAN

DISPLACEMENT AND ENVIRONMENTALLY-INDUCED MENTAL ILLNESS IN KEN

KESEY’S ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST................................................................. 1

CHAPTER : “UP AGAINST A MAD MACHINE”: THE PSYCHIATRIC REFUGE OF

WILDERNESS IN EDWARD ABBEY’S THE MONKEY WRENCH GANG ............................ 46

CHAPTER : THE CO-OPTED CONSCIOUSNESS: DON DELILLO’S WHITE NOISE AND

THE EVOLUTION OF ECOLOGICAL ANXIETY IN THE POST-NUCLEAR UNITED

STATES ...................................................................................................................................... 100

CHAPTER : MOURNING THE MOUNTAINS: SLOW VIOLENCE, CLASS, AND

ECOLOGICAL GRIEF IN ANN PANCAKE’S STRANGE AS THIS WEATHER HAS BEEN. 154

REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................... 217

iY

INTRODUCTION: “WITH THE EARTH IN MIND: ECOLOGICAL GRIEF IN THE

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN NOVEL”

In a 2014 study titled “Beyond Storms & Droughts: The Psychological Impacts of

Climate Change,” the American Psychological Association (APA) attests to a phenomenon that

has been garnering critical and popular attention as of late: as humans, we have begun to grieve

for the ecological decline of the planet. The APA study contends that as a result of climate

change, individuals are experiencing more general trauma, stress, and anxiety, or more specific

conditions such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Major Depressive Disorder

(MDD) and it anticipates an increase in mental health-related symptoms and conditions as the

effects of climate change continue to materialize (18-20). As they do, the psychological

symptoms of these conditions will gradually emerge. According to the APA, these symptoms

include substance abuse, depression, sense of loss, helplessness, fatalism, resignation, loss of

autonomy, and loss of personal identity and sense of control (22-24). While it is not inevitable

that climate change impacts individuals’ mental health and psychological functioning, the

likelihood of declining mental health in the face of ecological degradation is escalating.

Collectively, our growing awareness of ecosystems’ fragility and impending demise is causing

profound emotional turmoil.

With the Earth in Mind at once names the phenomenon whereby environmental

degradation provokes the decline of human mental health, and asserts literature’s capacity to

effectively address the nature of this phenomenon, reveal the destructive impacts of ecological

devastation, and encourage ecologically ethical behavior that can spare both human and

environmental deterioration. In this project, I will outline the emergence of what I call

“ecological grief” as an overlooked, yet critical phenomenon in the United States since 1945,

which post-World War II and contemporary American authors have explored since the war

v

ended. When Rachel Carson introduced the concept of environmental illness to popular

audiences in 1962, she did so by exposing the likelihood that the pesticide DDT entered the food

chain by accumulating in the tissue of animals and human beings, ultimately causing cancer and

other forms of genetic damage. In doing so, Carson alerted Americans to their own ecological

realities, and her work’s legacy attests to its immeasurable value. Since Silent Spring’s

publication in 1962, a variety of American authors have extended Carson’s essential arguments

that humans are not exempt from harm inflicted upon the ecosystems of which they are a part,

that human and nonhuman life is comprised of the same components, and that what affects,

mutates, or harms humans’ ecological surroundings stands to harm humans in the same way.

These critics and activists have, however, typically done so by imagining how damage to the

ecosystem manifests itself within the human body. The fictional works this dissertation features,

on the other hand, advance an essential element of environmental illness as they position the

human mind as a key component of the system of ecological vulnerability. Environmental

illnesses, these works suggest, are not contained within the human body, as it is traditionally

conceived. These works instead insist that environmental harm comes to bear on humans’ mental

health in critical and poignant ways.

In his 2001 Los Angeles Times article, “The World is Dying—and So Are You,” Richard

B. Anderson suggests that late twentieth- and early twenty-first century Americans are becoming

attuned to a “core of grief” which lies at “the heart” of the modern age. Anderson speaks to this

melancholia associated with the planet’s deterioration specifically as it evolved throughout the

twentieth century. “A great sorrow arises,” Anderson writes, “as we witness the changes in the

atmosphere, the waste of resources and the consequent pollution, the ongoing deforestation and

destruction of fisheries, the rapidly spreading deserts and the mass extinction of species.” It is

vi

generally accepted that the fin de siècle ushered in an era of irreparable change, which was

accompanied by anxiety and a sense of loss that plagued the modern era. However, I argue that

the particular “core of grief” Anderson highlights, which is fundamentally rooted in ecological

degradation, lies instead at the heart of the mid-twentieth-century. In particular, it originated as a

post-World War II phenomenon. WWII brought on a surge in industrialization, and ushered in

what scientists call The Great Acceleration, which represents a key phase within the current

epoch of the Anthropocene. According to Will Steffen et al., in the study, “The Anthropocene:

Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?,” the Anthropocene began with

the industrial revolution and extends to include our own contemporary moment. This epoch

signals humans’ recognizable geophysical influence on all ecosystemic components at a

planetary scale. Since 1950, which roughly marks the onset of the Great Acceleration, scientists

have recorded the greatest exponential rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide in the planet’s history.

Nearly three quarters of carbon dioxide emitted has occurred since 1950, and half has occurred in

the last 30 years (Steffen et al. 618). As a result of this rise in carbon dioxide emissions, among a

multitude of other effects, ice sheets and glaciers are melting worldwide; sea levels are rising;

precipitation is increasing; and floods and droughts are occurring.

Despite the profound reality of ecological damage, it is difficult for humans—both

societally and individually—to acknowledge and cope with the grief they experience as a result

of the environment’s degradation. As Cate Sandilands explains in her 2010 essay, “Melancholy

Natures, Queer Ecologies,” “there is lots of evidence of environmental loss, but few places in

which to experience it as loss, to even begin to consider the diminishment of life that surrounds

us on a daily basis [as] something to be really sad about, and on a personal level” (338). While

the loss of human life is marked by rituals and performative events such as funerals, various

vii

forms of burial, and, in many cultures, periods of prolonged mourning, the loss of nonhuman life

in American culture, and a multitude of other Western and/or industrial cultures, is not. As

Sandilands explains, these “object[s] of loss [are] very real but physically ‘ungrievable’ within

the confines of a society that cannot acknowledge nonhuman beings, natural environments, and

ecological processes as appropriate objects for genuine grief” (333). It is time, however, that we

begin to recognize the “grievability” of nonhuman beings, and thus to recognize these beings’

inherent value. Turning to literature, I argue, enables this recognition.

Civilization and its Ecological Discontents

A grieving process that is both psychological and performative becomes a necessary tool

for psychological healing in the face of the planet’s deteriorating ecosystems. To be denied the

appropriate avenues of grief for these objects of loss can result in melancholia, notes Sandilands.

Freud, in “Mourning and Melancholia,” initiated a long modern tradition of exploring both

human psychological responses to both loss, and human-world interconnections. For Sandilands,

the critical tension between mourning and melancholia sheds light on humans’ melancholy

natures or, the experience of ecological grief. Whereas mourning has a finite timeline,

melancholia entails a suspended state of mourning. That is, mourning, like melancholia,

“involves grave departures from the normal attitude to life,” but is “overcome after a certain

lapse of time” (“Mourning and Melancholia” 243-44). However, with mourning, “the bereaved

ego becomes able to transfer attachment to new objects” (Sandilands 334). In the case of

melancholia, however, the ego will not and cannot let go. “Instead of transferring attachment

outward to a new [object]…the melancholic internalizes the lost object as a way of preserving

it.” This disallowance of grief at once “denies the loss,” and traps the melancholic individual

viii

within an unhealthy cycle of mental illness. As Sandilands so insightfully demonstrates, Freud’s

psychological theories are applicable in the case of ecological loss, as they elucidate the

psychological effects of such loss, the psychological ramifications of impeded grieving

processes, and the presumed “ungrievability” of ecological objects of loss. Freud’s work thus

lays a foundation for this dissertation’s contention that ecological grief manifests in humans who

have been denied the appropriate venues to mourn ecological loss, but nonetheless harbor an

inherent need to lament the loss(es) they have experienced.

Beyond substantiating the premises of ecological grief, Freud’s theories attest to the

foundational psychological inclinations that drive humans’ inherent connections to the natural

world. In Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), Freud discusses the “indissoluble bond,” or the

feeling of “being one with the external world as a whole” (12). In his opening chapter, Freud

recounts a letter sent to him by an unnamed friend, wherein this friend at once agrees with

Freud’s treatment of religion as an illusion,1 and yet laments Freud’s inability to recognize “the

true source of religious sentiments” (10). Freud explains,

This, he says, consists in a peculiar feeling, which he himself is never without,

which he finds confirmed by many others, and which he may suppose is present

in millions of people. It is a feeling which he would like to call a sensation of

‘eternity,’ a feeling as of something limitless, unbounded—as it were, ‘oceanic.’

(10-11)

While Freud admits that he cannot recognize this “oceanic” feeling in himself, and while he

cannot convince himself of “the primary nature of such a feeling,” he maintains that his own

1 See The Future of an Illusion, 1927.

ix

inability to perceive an indissoluble bond with the world outside of himself gives him “no right

to deny that it does in fact occur in other people” (12). In other words, whether or not Freud can

perceive his placement within an “oceanic” system of life is irrelevant. Despite the ego’s

maintenance of “clear and sharp lines of demarcation” between our selves and that which exists

outside of our selves, and despite our ability to perceive this demarcation, he acknowledges that

the boundary between ego and object can and does at times melt away (13). In fact, notes Freud,

our infant beginnings suggest such a state: “An infant at the breast does not yet distinguish his

ego from the external world…He gradually learns to do so” (13). The ego’s earliest state in fact

incorporates the external world, and it is only later that it detaches itself. This means that “[o]ur

present ego-feeling is, therefor, only a shrunken residue of a much more inclusive—indeed, an

all-embracing—feeling which corresponded to a more intimate bond between ego and the world

about it” (15). The assumption that certain individuals experience the persistence of this feeling,

the sense of “limitlessness and of a bond with the universe,” or the “oceanic” feeling to which

Freud’s friend alludes, lays the groundwork for a major premise of my argument in this

dissertation: that humans maintain an “ecological unconscious.”2 In such cases, a primordial state

of mind has persisted, rather than having been overlaid. Humans experience “discontent” in a

Freudian sense, then, when the must repress their ecological unconscious desires, instead

maintaining a superficial connection with the vast system of life to which they belong.

Echoing Freud’s notion of humans’ limitless bond with the universe, ecopsychologist

Theodore Roszak introduces the concept of “the ecological unconscious” in The Voice of the

2 In 2007’s Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind, Evan Thompson

refers to a similar kind of “feeling of self and world” as sentience, or the ability to feel the

presence of one’s body—mind included—in the world (221).

x

Earth (1992) (301). Roszak coins the term to describe humans’ inherent connection to their

natural environment. The ecological unconscious, according to Roszak, drives a primordial

human need, that dates back to our distant human conditions. Of course, we must historically

distinguish Roszak’s concept from Freud’s, for Roszak points to the rise of symptoms related to

the repression of the ecological unconscious as specific to the postwar moment, one that I assert,

additionally, results from the material ecological degradation associated with the Great

Acceleration. The exponential growth of technological and industrial “progress” within the

postwar moment, and, accordingly, the ecological harm engendered by the spread of technology

and industry, alienated humans from their natural environments and/or impeded human

connection to healthy ecosystems by degrading the environment (Voice of the Earth 320). Since

the beginnings of the Great Acceleration, humans have struggled to fulfill the needs of the

ecological unconscious. Because there is an “interplay between planetary and personal well-

being,” as Roszak contends—meaning that the health of the psyche depends on the health of the

natural environment—humans’ ability to integrate ourselves with healthy ecosystems is critical.

And yet, contemporary advancements in unsustainable industrialization, capitalism, and even

basic ways of life have interfered with humans’ ability to do so. As a result, humans are

experiencing ecological grief.

But coping with this ecological grief is nearly impossible, given the widespread inability

to draw adequate connections between environmental degradation and mental illness. For one,

drawing such a correlation is tricky due to the difficulty of assembling quantifiable, scientific

data to prove that the degradation of one’s environs corresponds with the decline of her or his

mental health. Patients typically self-diagnose and self-report their symptoms, often drawing

their own conclusions as to the cause of their suffering. For example, in the case of afflicted

xi

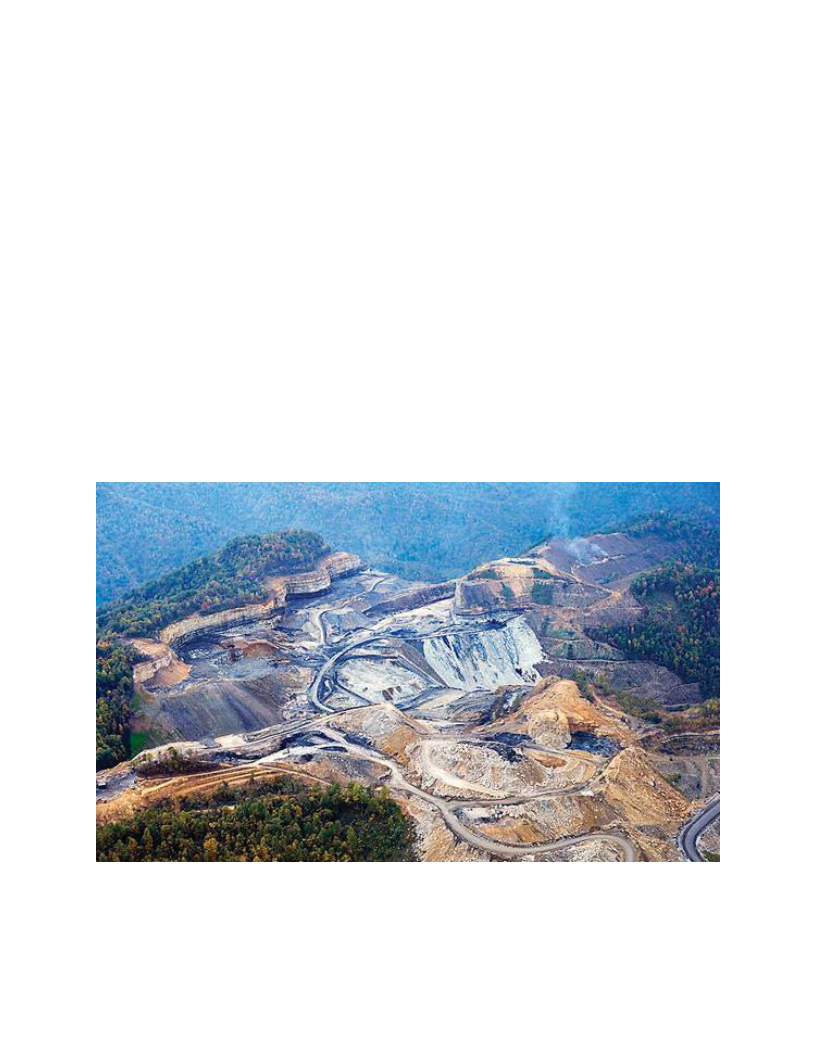

individuals living in close proximity to mountaintop removal (MTR) sites in West Virginia, a

state which has one of the highest depression and suicide rates in the United States, scientists

have struggled to find a distinct correlation between the ecological devastation that results from

MTR and the elevated depression and suicide rates.3 Moreover, studies often attribute mental

health disorders in West Virginia to social, economic, and cultural factors such as lack of access

to education and mental health services, as well as high rates of unemployment (Keefe 1).

Even more problematic, however, for the endeavor of correlating environmental

degradation and mental illness is the American historical and cultural propensity for

misrecognizing or misconstruing instances of environmentally-induced mental illness as

nostalgia. As Jennifer K. Ladino notes in Reclaiming Nostalgia: Longing for Nature in American

Literature (2012), “a nostalgic infatuation with nature remains a powerful force in popular

culture” (xiii). Ladino seeks to “reclaim nostalgia” for more progressive means, and argues that

nostalgia has the potential to aid environmental movements. Nostalgia often stimulates

sympathy, she explains, and ultimately might inspire individuals to advocate for environmental

preservation. However, Ladino also interrogates the general skepticism towards nostalgia, and in

doing so, reinforces it at times. Ladino explains,

Notsalgia’s scapegoat status stems from a range of admittedly problematic traits:

its easy cooptation by capitalism, which critics like Fredric Jameson say generates

a postmodern cultural paralysis in which old styles are recycled and marketed

without critical effect (or affect); its ubiquity in the media and the arts, which

3 The nonprofit, nonpartisan group, State of the USA, conducted a state by state analysis, which

placed West Virginia just behind the state with the highest rates of depression, Mississippi, by

only .5 percentage points.

xii

signifies a lack of creativity, alienation from the present, and complicity in

consumer culture; its tendency to romanticize the past through imagining an

origin that is too simplistic; and its reactionary bent—the use of nostalgia by

right-wing forces to gloss over past wrongs and to glorify tradition as justification

for the present. (5-6)

When we wax nostalgic about “lost” environments, it is typically in reference to conceptions of a

people-less nature or wilderness that existed prior to the European colonization of North

America. But “wilderness” was never “untrammeled by man,” as The Wilderness Act would

have us believe. It has always been a site of human-ecological correspondence and kinship.

Nostalgia can perpetuate such understandings of socially constructed nature, rather than as an

amalgamation of material elements. Accordingly, nostalgia is often referred to as a “social

disease” that references a “felt lack” (Stewart 23), rather than the psychological impacts of a

distinct material site’s demise or loss.

Nonetheless, nostalgia can offer an effective starting point for advancing conversations

about the relationship between individuals and the sites for which they long, and which they

yearn to effectively grieve, in the case of localized ecological destruction of decline. In fact,

nostalgia is one of the only words in English that describes the links between the human mental

state and the environment. Literally, nostalgia means homesickness, with “nostos” meaning a

return to native home or land and “algia” meaning pain or sickness. Attending to nostalgia as

early as 1678, medical doctors once diagnosed nostalgia as a medical conditionand thus a bodily,

material one.4 However, they were ultimately unable to locate the disease in the body, or to

4 See Ritivoi 20 and Boym 9-10.

xiii

determine a unified taxonomy of causes (Ladino 7). Ultimately, nostalgia was de-medicalized at

the turn of the twentieth-century. Accordingly, it was stripped of its material, spatial, and

environmental connotations, and came to be best understood as we widely regard it currently: in

relation to time rather then material reality.

While Ladino’s attempt to “re-place” nostalgia by redeploying it for effective activist

means is a worthwhile scholarly endeavor, the phenomenon carries too great a cultural weight to

be practical. Widespread cultural assumptions have defined—and continue to define—nostalgia

as a romanticized relationship to the past. In the case of utilizing nostalgia to promote an

effective environmental ethic, as Ladino hopes, it is simply too difficult to destabilize the

overarching narrative surrounding it, as this narrative is indelibly rooted in our own American

ethos, which harkens back to Americanization and manifest destiny. American narratives,

especially nature narratives written since the “close” of the western the frontier in 1890, exhibit

nostalgia for the lost frontier and an uninhabited wilderness, as well as pastoral and pre-industrial

societies (Ladino 10), while continuing to dominate the American historical imagination.5 The

overbearing presence of nostalgia in these narratives and others is in many ways dangerous, as it

overlooks American histories of violence and oppression—oftentimes including the very

instances of environmental degradation and dispossession that likely precipitated early,

unrecorded instances of ecological grief—in favor of an idealized mythology that neatly ties

settler-colonial Euro-Americans to the landscape that comprises the nation.

Reinterpreting oft-misconstrued instances of nostalgia as potential instances of ecological

grief makes room for a pathology that recognizes the complex interrelationship between human

5 See Frederick Jackson Turner’s “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” (1894).

xiv

mental health and environmental health, and makes rooms for a necessary discourse in the social

and psychological sciences that attends to this phenomenon. Australian environmental

philosopher Glenn Albrecht’s concept of “solastalgia” is a more useful concept for the purposes

of this project, which, like Ladino’s, seeks to advance a productive discourse that can facilitate

environmental ethics and justice. The relationship between ecosystem stress and human distress

has driven Albrecht’s research over the past 25 years. By bringing to bear the work of Elyne

Mitchell, which suggests that when humans are “divorced from [their] roots [they lose] psychic

stability” (4), on David Rapport’s concept of “ecosystem distress syndrome” (628), Albrecht

began to conceive of “psychoterratic illness,” or environmentally-induced mental illness.6

Whereas theorists had previously interrogated contemporary “place pathology” and the resulting

symptoms of disorientation, depression, and various modes of estrangement (Casey 38) amongst

displaced peoples such as Native Americans, Albrecht is interested in places that are not

“completely lost,” but places that are “being transformed” (“Solastalgia: A New Concept” 44). In

Albrecht’s study, the people of particular concern are not always forcibly removed from their

homeplaces. However, their “place-based distress [is] also connected to powerlessness and a

sense that environmental injustice [is] being perpetrated on them.” In other words, as Albrecht

explains, though still “at home,” the individuals in question “[feel] a similar melancholia as that

caused by nostalgia connected to the breakdown of the normal relationship between their psychic

identity and their home” (“Solastalgia: A New Concept” 44). Albrecht’s “solastalgia,” then,

describes the “specific form of melancholia connected to lack of solace and intense desolation”

6 Albrecht argues that Mitchell “should properly be seen as Australia’s Also Leopold” (41).

xv

with which I am concerned in this dissertation, and from which I derive my concept of ecological

grief.

The Novel and Ecological Consciousness

American society’s tendency to participate in superficial nature-nostalgia, rather than

active and engaged environmental mourning, perpetuates ecological grief. But by calling upon

literature, which constitutes its own imaginative domain for addressing this phenomenon, we can

begin to identify ecological grief as a result of environmental degradation, and thus to address

this phenomenon and its causes. Given the difficulty that conventional scientific and political

discourse has traditionally faced in identifying and substantiating a correlation between

ecological and human psychic stability, literature becomes an essential ally and a rich source for

investigating the phenomenon of environmentally induced mental illness. Whereas other

disciplines require particular data sets that arise from controlled environments, literature attends

to humans’ ecological realities in more imaginative and enterprising ways. If literature, as David

Lodge asserts, is “a record of human consciousness, the richest and most comprehensive we

have” (10), and if it “constitutes a kind of knowledge about consciousness which is

complementary to scientific knowledge” (16), then literature stands to reveal the human

consequences of ecological loss in a way that is unavailable to political, philosophical, scientific,

and even psychological discourse.

Novels in particular can effectively address the nature of the ecological unconscious and

the ecological grief individuals endure because of a lack of sustaining ecological implacement,

for the genre’s narrative form allows for a sustained appraisal of human psychological processes,

and stands to affect social reform. The emergence of the novel as a form corresponds with

xvi

western philosophy’s preoccupation with human consciousness within the last three and half

centuries (Demasio 231), and thus it is no coincidence that the same period that saw the rise of

the concept of consciousness also saw the rise of a new narrative literary form in the novel

(Lodge 39). Whereas earlier narrative forms—the epic, for example—recycled stories and tropes,

the novel attempted new and unique stories that spoke to the individuality of human experience,

and human consciousness. Moreover, unlike the forms that preceded it, the novel emphasized

“interiority of experience” (Lodge 39). In accordance with Descartes’s paradigm-shifting

philosophy that consciousness determined humanity, the grandiose form of the novel burgeoned,

giving prominence to “phenomena such as memory, the association of ideas in the mind, the

causes of emotions and the individual’s sense of self” (Lodge 40). Meanwhile, the novel allowed

for dramatic arcs and tensions, and lent itself to a sustained, nuanced narrative; a well-developed

plot; and strong characterization. Combined, these elements contributed to complex literary

representations of the human psyche.

The novel’s techniques for representing human consciousness have been widely critiqued

and theorized. For instance, in Transparent Minds: Narrative Modes for Presenting

Consciousness in Fiction (1978), Dorrit Cohn highlights the extent to which the novel allows for

extraordinary access to a fictional character’s interiority. “Fictional consciousness,” she writes,

“is the special preserve of narrative fiction” (vi). The novelist finds her or himself in a

particularly powerful position: she or he is a “creator of beings whose inner lives [she or he] can

reveal at will” (4). Cohn asserts, moreover, that the novel’s creative resources position it to tell

the audience “how another mind thinks, another body feels” (5-6). It does so by way of an

authoritative narrator, or by generating what Dorothy Hale calls “the illusion of quoted mind

content” (273). Even as she or he “draws on psychological theory and on introspection,” the

xvii

novelist, says Cohn, “creates what [José] Ortega called ‘imaginary psychology…the psychology

of possible human minds’—a field of knowledge the Spanish critic also believed to be ‘the

material proper to the novel’” (6). For these reasons, the novel as form positions us to effectually

question the nature of the ecological unconscious.

Additionally, the novel’s social, historical, and political value positions it as a form of

social discourse that stands to enact social change. Or, in the case of the novels I examine here,

to enact environmentally ethical behavior. By at once “[depicting the] particular experience of

fictional characters in their social worlds,” and “[positioning its] readers as witnesses to and

interpreters of those fictional worlds” (Hale 437), the novel performs a social function. In

Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction 1760-1860 (1985), Jane Tompkins

equates the novel’s social power with all other forms of social discourse. For Tompkins, the

novel performs the same kind of ideological work as both nonfiction writing, and other forms of

nonliterary writing (539). In fact, for Tompkins it is the literary form best suited to persuasion

and thus to social reform. By “emotionally acting upon” the reader (Hale 447) and positively

soliciting the reader’s affective engagement, the novel stands to persuade readers, who may

come to a novel from a social position that contends with the ideals of the novel, or at least

render them willing to change their views. Novelistic discourse, as Tompkins argues, is

particularly well-suited to expressing the need for social change, and even for envisioning and

ultimately enacting such change.

While Tompkins is interested in the sentimental rather than the realist novel, this project

focuses almost entirely on realist novels. Traditionally speaking, the realist novel effectively

emphasizes the need and serve as a tool for social change by enacting the “powers of realism”

that Hale attributes to the novel in compelling representations of “real” material environments.

xviii

Lilian Furst offers a compelling interpretation of the realist novel in its contemporary moment in

All is True: The Claims and Strategies of Realist Fiction (1995), which points out that despite the

difficulty of realistic representation, the importance of the realist novel is that these novels

relentlessly grapple with the task. One way of confronting the obstacles of realistic

representation, notes Furst, is via one of the “cardinal conventions of the realist novel”:

particularity of place (24). She writes,

Place can be taken either literally, as a way to endow the fiction with the stamp of

truth, or more obliquely, as a part of a complex scenario in which it still plays a

vital role—not as a direct replica but rather as a prop in the animation of a

pretense. In both cases, place is central to the plausibility of the fiction. (24-25)

The suggestion that the places these novels imagine are real lends plausibility to the fictional

representation of the real. For instance, Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962)

depicts Celilo Falls on the Columbia River in Oregon, Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench

Gang (1975) portrays (what once was) Glen Canyon in the desert Southwest, and Ann Pancake’s

Strange as This Weather Has Been (2007) sketches Buffalo Creek in West Virginia. Such

incorporation of these “semblances of reference” into the process of representing material

realities is a distinctive hallmark of the realist novel, explains Furst, as is it advances the closest

thing it can to reality: a pretense of truth (25). Don DeLillo’s White Noise (1982) is, of course,

the exception to this rule. A prototypically postmodern novel, White Noise may seem an

unorthodox choice. However, it is the novel’s social context that interests me, and by conducting

the necessary historical research and positioning the novel effectively within this context, I am

able to attend to its realist elements. That is, although the text’s symbolic technique is highly

refractory, these symbols stand in for very real material environments and conditions, which lend

xix

themselves to a reading of toxic materiality as it comes to bear on the human mind. While

Blacksmith isn’t a “real” town, that is, we associate its realities with towns we know. It could—

and may as well—be Niagara Falls, New York, where the Love Canal Tragedy Occurred, or St.

George, Utah, which lies downwind of the Nevada Test Site. Both locations, like Blacksmith

itself, house populations typically protected from environmental injustice. The realist novel—and

sometimes, it turns out, the postmodern novel—by utilizing place, or material ecological sites to

develop realistic plausibility, does important work then as it gives its readers a sense of the

everyday realities of ecological grief.

Of course, imagining interiority and psychology in completely realistic ways is

essentially impossible. The realist novel nonetheless attempts to do so by representing both

environments and psychologies in tandem, engaging in a balancing act commonly enacted in the

novel, which Cohn aptly refers to as “the mutual dependence of realistic intent and imaginary

psychology” (6). Although novelists can only “imagine” these psychologies, their characters’

interiority takes on the next best thing: what Henry James in “The Art of Fiction” calls “one of

the supreme virtues of the novel…the air of reality” (my italics). The novel, the most distinctive

feature of which, according to Hale, is its “capacity for sustained psychological realism” (272), is

also the most suitable site for “the mimesis of consciousness” (Cohn 7). Because consciousness

is, by Freud’s definition “that which can never be known by consciousness but which expresses

itself indirectly through its effects on consciousness” (Hale 274), like the air of reality, a mimesis

of consciousness also serves realist purposes, especially if this mimesis can position readers to

“establish an affective relation that rivals our real-life social relations” (Hale 273). It is in this

way that the realist novels this dissertation highlights (and the postmodern novel it includes)

xx

conscientiously enact the work of plausible representation, and encourage ecologically-ethical

behaviors.

Material Ecocriticism and the Embodied Mind

While ecocriticism has begun to focus on the transcorporeality of human bodies and

environments on a material level, by investigating how the aforementioned novels associate

psychological affliction with environmental degradation, this dissertation challenges the critical

tendency to emphasize bodily over psychological harm, and advances the theoretical position

that environment, body, and mind are interlinked and mutually determined. Environmental

historian Linda Nash’s Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and

Knowledge (2007) is a revealing example of recent criticism that advances the study of human-

environmental material relationships in vital ways, and yet which nonetheless disregards the

human mind, or brain, in its analysis of humans’ bodily reactions to environmental stressors.

Silent Spring propels Nash’s argument, as Nash points to the publication of Carson’s seminal

work as perhaps the moment that Americans came to experience and understand their own health

as connected to the health of the land. Carson blew a whistle that resounded from coast to coast,

revealing to Americans that the indiscriminate dissemination of the pesticide DDT posed

extensive harm not only to its intended target, but to entire ecosystems as well, including the

human inhabitants of these ecosystems. Silent Spring still garners praise today for highlighting

the dangers that these newly introduced and widely disseminated chemicals posed to human

bodies. And yet, recent scientific research suggests that the dissemination of DDT also affected

exposed humans psychologically. Scientific studies not only reveal that “the relation between

farming, pesticide exposure or poisoning, depression, injury and suicide is an area of increasing

xxi

concern” (Freire and Koifman 445). They go so far as assert that “exposure to high levels of

pesticides, including poisoning, experienced by agriculture workers and rural residents may

result in an elevated risk of neuropsychiatric sequelae (mood disorders, depression and anxiety)

and suicide attempts and mortality.”7

While Nash and others overlook what Evan Thompson calls “the deep continuity of life

and mind,” theorists from other disciplines, such as Gregory Bateson and Christopher J. Preston,

do in fact address the embodied mind. These theorists’ work has vast implications for this

literary project, as they provide a theoretical framework for understanding the “hard problem of

consciousness” that comes to bear on ecocritical work, and is likely at the core of many

ecocritics’ emphasis on traditionally conceived bodies—mind not included—as the objects of

environmental harm. Thompson describes this problem thusly:

Many philosophers of mind today believe that a profound difference exists

between consciousness and mere biological life. On the one hand, consciousness,

or more precisely, so-called phenomenal consciousness, is thought to be an

internal, subjective, qualitative, and intrinsic property of certain mental states.

Life, on the other hand, is thought to be an external, objective, structural, and

functional property of certain physical systems. Given this way of thinking, the

attempt to understand consciousness and its place in nature generates a special

problem, the so-called problem of hard consciousness. (222)

In other words, Thompson explains, “there seems to be an explanatory gap between physical

structures and functions and consciousness” (223). And yet, “mental life is also bodily life and is

7 See also London et al., 2005 and 2012, Meyer et al., and Pearce et al.

xxii

situated in the world” (ix). “The roots of mental life lie not simply in the brain,” he asserts.

Rather, they “ramify through the body and environment.” “Our mental lives involve our body

and the world beyond the surface membrane of our organism, and therefor cannot be reduced

simply to brain processes inside the head,” adds Thompson (ix). What we call interiority then, in

his words, “comprises the self-production of an inside that specifies and outside to which that

inside is constitutively and normatively related” (225). I echo Thompson’s sentiment that we

must dismiss these dualisms that pit consciousness and life—or mind and environment—against

one another, and “go beyond the idea that life is simply an ‘external’ phenomenon in the usual

materialistic sense” (224).

Reconceiving of the mind as situated in the material world positions us to remedy

ecological destruction. In Gregory Bateson’s opinion, we must come to some understanding

about how to motivate individuals to act in ways conducive to achieving this goal. We can’t

change our actions, that is, without first changing how we think. In his Steps to an Ecology of

Mind (1972), Bateson calls for an interdisciplinary approach to investigating how consciousness

changes and influences individual and social patterns. Thinking of the mind as an ecosystem of

sorts is crucial to this endeavor, he suggests (xxiii). His interest in systems theory (xxxii) leads

him to consider the mind as part of a broader network. Bateson revisits his central thesis in Mind

and Nature: A Necessary Unity (1979), in an attempt to “give the ecology of mind a more

explicit, coherent, and articulated form than the one elaborated in Steps” (Manghi xi). Here, he

delivers what Sergio Manghi calls a “precious lesson” for the twenty-first century: “After the

rapid globalization of the liberal economy and the overwhelming progress of technologies of life,

weapons, and communications, for good as well as for evil, there is an increasing necessity for

an awareness of being part of relational contexts, both great and mysterious…” (xii). Bateson’s

xxiii

interests in the ways that the world shapes human consciousness and understanding, and

humanity’s systematic relationship to the living world—or what he calls the “unity of biosphere

and humanity” (Mind 16)—lay the foundations for this project.8

Despite the existence of the kind of anthropological and philosophical work conducted by

Bateson and Preston, and sociological and psychological research that suggests that ecological

stressors can alter the human mind, ecocriticism stands to account for these interdisciplinary

advancements more fully. For instance, in her 2010 work Bodily Natures: Science, Environment,

and the Material Self (2010), Stacy Alaimo re-conceives of human corporeality and materiality

via the concept of “transcorporeality.” Alaimo focuses almost entirely on the human body as it is

traditionally understood: as an entity separate from the human mind. 9 Alaimo does so by

highlighting the extent to which the human body is “‘intermeshed’ with the more-than-human-

world” (2). Humans and nonhumans are materially interconnected, Alaimo argues. Human

“selves” are not sealed off entities, but are rather beings undergoing constant change in relation

8 Preston’s work, which the philosopher professes takes as its central interest “the connections

between place and mind” (xi), builds on the tradition of research Bateson initiated. Preston’s

main argument is that our physical environment comes to play an important role in structuring

the way we think,” for humans—like all other “organisms that know things about the world”—

are “situated beings, beings cognitively grounded in the worlds from which they speak” (xi). The

material realities of place shape mental activity, Preston argues, and constitute some of the most

important factors relevant to the study of “how we know.”

9 Alaimo does, however, note that some dismiss Multiple Chemical Sensitivity as a

psychosomatic or hysterical condition (114), and “[fix] the blame” for MCS on an afflicted

individual’s psyche (119), which of course sheds a great deal of light on how we as a culture

view mental disorders, generally. Additionally, she echoes this dissertations claims to the

materiality of the mind, explaining, “the debate over whether MCS is a psychological or medical

condition is, of course, an argument about whether or not this illness is ‘real.’ Those who argue

that MCS is psychosomatic not only conceive of the mind as strangely immaterial, but they sever

the psyche, as well as the rest of the person, from the broader environment” (128). However, on

a whole, her work focuses on the materiality of the “body,” and thus she leaves room for the

work I enact in this dissertation.

xxiv

to our interactions with other human and nonhuman life. Neither the human body nor the

nonhuman world are self-referential, Alaimo insists. Instead, both are simultaneously made at all

times. The material world, then, as she explains, is actually the very substance of our human

selves. Additionally, this means that, like humans, nonhuman environments, which are “too often

imagined as inert, empty space or as a resource for human use,” constitute material entities with

their own needs and requirements for survival (2). Although Alaimo has developed the

invaluable premise that underlies this dissertation, her work nonetheless invites the kind of

complication this dissertation will undertake.

Like Alaimo’s material ecocritical study, Heather Houser’s Ecosickness in Contemporary

U.S. Fiction: Environment and Affect (2014) calls for complication as well. Houser’s work

theorizes the emerging literary tradition of “ecosickness fiction,” or post-1970—and post Silent

Spring—American fiction and memoir that interweaves the human material self and its material

environs by way of environmental illnesses. However, despite its professed interest in

transcorporeal ecological harm to both environment and human, Houser’s work, too, overlooks

an opportunity to incorporate the human mind into her analysis. While affect, she argues,

“designates body-based feelings that arise in response to elicitors as varied as interpersonal and

institutional relations, aesthetic experience, ideas, sensations, and material conditions in one’s

environment” (3, my italics), she underplays the psychological and neurological aspects of affect

and perpetuates the dualism that separates human body and mind. Nonetheless, Houser’s work,

like Alaimo’s, is invaluable to my own, for she introduces an analytic framework for

investigating the trope of sickness in literary works, using particular affects that determine

degrees of ecological investment or disengagement, and situating affect as a narrative mode that

advances environmental consciousness amongst its readership.

xxv

While Nash, Alaimo, Houser, and others have complicated our understanding of human

materiality by exploring the interconnectedness of human bodies and nonhuman environments as

codeterminative, these critical analyses need to be pushed even further.10 Discussions of

environmental illness abound in this tradition of material ecocriticism, but these critics and

theorists have yet to consider environmentally induced mental illness and trauma. With the Earth

in Mind broadens the concept of transcorporeality by situating the human mind as part of this

material network. Although, as David Chalmers notes in his well-known essay, “Facing Up to

the Problem of Consciousness,” we must consider the mind to be more than mere matter, it is a

material facet of the human body, nonetheless. In other words, the mind functions as both mind

and brain, a mass of tissue, neurons, and other material components that are susceptible to the

same environmental stressors impacting the material ecosystem of which it is a part.

Understanding the mind thusly allows us to expand our conception of the full complexity of

humanity’s relationship to environment.

Reconditioning the ways in which we conceive of our selves materially in relation to the

environment is often regarded as a posthumanist endeavor but ecocriticism stands to gain a great

deal from advancing this ethic as well. It is my hope that this project will aid the ethical

advancement of the field of ecocriticism by extending the work of material ecocriticim to effect

ecocritical theories, methodologies, and activisms. The material ecocritics whose work I draw on

herein—Nash, Alaimo, Houser, et al.—account in numerous, conscientious and inspiring ways

for how the material world acts upon and affects human bodies, behaviors, and knowledges.

10 See also Priscilla Wald’s Contagious (2008), which informs these critical approaches via its

invaluable contributions to twentieth-century medical literature. Herein, Wald outlines a tradition

of twentieth-century “outbreak narratives” that utilize public health discourse and methods of

infection and treatment.

xxvi

Furthermore, these critics propose environmental ethics that deny the human subject a

centralized, privileged position, instead repositioning it as part of a larger and equally agential

material network. In other words, these theorists show how the human material self effects and is

affected by the material environment in such a way that primes us to begin conceptually

reconfiguring the human-environment relationship in light of a new sense of responsibility and

morality. Reimagining human corporeality and materiality by highlighting the extent to which

the human body is “‘intermeshed’ with the more-than-human-world” (Alaimo 2) is an inherently

ecological endeavor. While many see this as a posthumanist ethic, I establish its suitability as an

ecocritical one as well. If ecocriticism is to effectively enact a spirit of activism, as it has

expressed interest in doing, it is only “natural” that it actively promotes transcorporeal

understandings of the human self holistically in relation to the material environment.

Beyond these contributions to the practice of ecocriticism, the argument this dissertation

poses—that a tradition of postwar and contemporary American novels support philosophical and

epistemological claims that the human mind is a part of a larger ecological and material network,

and indicates that environmental degradation can, accordingly, impact the human mind—

represents a key intervention into the study of contemporary American literature. It does so by

showing how, in light of postwar writings that revealed to Americans the effects on the human

body of environmental pollution, toxins, and fallout, various authors have highlighted a critical

element of the relationship between human beings and their environments. By reimagining a

network of mutuality between earth, body, and mind, these authors suggest that humans and their

environments not only interact with but also co-constitute one another. Through their fictional

treatments of ecological grief, these authors help their readership to understand the need for

alternative modes of ecologically ethical conduct.

xxvii

This dissertation’s close readings present an overall picture of a literary tradition that

contends with dominant ideologies that insist upon separating the human and the environment,

and thus has the potential to advance a suitable ideology and/or environmental ethic. This

ideology/ethic a) recognizes that the environment is the substance of the human, and vice versa,

and b) reconsiders the material world as neither an inactive resource for human consumption,

nor, in Alaimo’s words, “a deterministic force of biological reductionism” (2). Specifically, the

literary representations of psychoterratic illness that this dissertation features collectively

exemplify the extent to which human health relies on environmental health. These readings

ultimately suggest that contemporary American literature’s recognition and treatment of trans-

corporeality and environmentally induced mental illness demonstrates the crucial nature of

material beings’ interconnectedness to material environments and calls for the appropriate,

ecologically ethical behavior from its readership.

Chapter Outline

The postwar and contemporary American novels I examine in the following chapters

represent the complex nature of ecological grief by creatively representing the psychological

consequences of a systematic denial of humans’ evolutionary need to connect with a healthy

natural environment. That is, they portray instances of environmental degradation that negatively

impact not only the bodies of the humans who are intertwined with threatened ecological

communities, but these individuals’ minds as well. These novels position acts of environmental

degradation and injustice—from damming to logging, and from nuclear contamination to

mountaintop removal—as harmful to the human mind. Moreover, they not only supplement

emerging scientific, neurocognitive, and ecopsychological studies that suggest the reality of

xxviii

pyschoterratic illness, but stand to give prominence to the exigency of this phenomenon.

Furthermore, these novels reimagine earth, body, and mind as interwoven components of an

ecological tapestry, and make clear that humans and their environments not only interact with

but also affect and shape one another. While these novels cannot, in themselves, suggest a

distinct chain of causality, nor enact a therapeutic response to psychoterratic illness, they

nonetheless vividly represent environmental harm, and stand as a call to action against the

damage done to both environments and humans simultaneously. The novels I examine in the

following chapters are Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), Edward Abbey’s

The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975), Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony (1977), Don DeLillo’s

White Noise (1985), and Ann Pancake’s Strange as This Weather Has Been (2007). Additionally,

I incorporate into these readings the work of nonfiction writers, who cannot utilize fictional, and

more specifically, novelistic methods as they take issue with the same instances of environmental

degradation that their fictional counterparts critique. Nonetheless, pairing the novels in this study

with nonfiction works like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), Katie Lee’s All My Rivers Are

Gone: A Journey of Discovery Through Glen Canyon (1998), Terry Tempest Williams’s Refuge:

And Unnatural History of Place (1992), and Eric Reece’s Lost Mountain: A Year in the

Vanishing Wilderness (2007) at once allows me to outline the extra-literary context of these

instances of environmental degradation, and to illuminate the phenomenon of ecological grief

more broadly.

With the Earth in Mind interweaves a narrative history of twentieth-century American

environmental thought with a more detailed account of a distinct literary tradition that speaks to

the nature of human-environment interaction, and that emerged in complex relation to dominant

environmental attitudes. Throughout these chapters, I trace the ways in which literary treatment

xxix

of ecological grief has developed since 1962, when Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s

Nest and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring were both published. In chapter , I examine how

Cuckoo’s Nest situates the embodied human mind as vulnerable to various forms of

environmental degradation and displacement by illustrating the emergence of environmental

grief in its narrator, Chief Bromden, as a result of his tribe’s ecological dispossession. I also

argue that Kesey anticipates and presents in narrative terms a core insight of ecopsychology that

is critical to this project’s overall argument: that humans possess an “ecological unconscious,” or

an evolutionary need to stay connected to their natural environments, and that a repression of this

need has damaging psychological effects.

Chapter interrogates Edward Abbey’s intervention into the twentieth-century

American wilderness debate with his 1975 novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang. Abbey’s novel

further develops a psychoterratic literary tradition by exploring the ecological grief his characters

suffer in the face of their exile from the wilderness spaces that sustain them. In a postwar

moment that sent American flocking to wilderness areas and national parks in numbers greater

than ever before—a moment wherein the parks came under threat of “being loved to death”

(Nash 316) as a result of littering, overcrowding, and pollution—Abbey’s novel attributes his

characters’ psychological damage to the destruction of wilderness associated with this boom.

That is, as Abbey declares unadulterated wilderness a “psychiatric refuge,” or a requirement for

human beings’ mental health, he concurrently indicates the psychological effects of denying

humans access to such sites (whether by physically banning them from wilderness, or by

despoiling the ecological integrity of it).

Chapter turns to Don DeLillo’s White Noise (1982), which presents the aftermath

of the industrialization that Kesey and Abbey sought to preempt, and thus provides a new angle

xxx

from which to interpret the environmentally embodied mind. DeLillo’s novel contends with a

subtler, more insidious form of environmental degradation, which has already eradicated any

possibility for unmediated ecological interaction between humans and the environment, let alone

reciprocity: toxic contamination. White Noise suggests that the conditions of a “risk society”—

with its emphasis on perpetuated ecological threat—can be understood in themselves as

contributing to psychoterratic illness, as they in fact awaken ecological awareness, and thus

contribute not to ecological grief, per se, but rather to ecological anxiety. This chapter argues that

DeLillo’s novel calls upon the U.S.’s history of nuclear anxiety and fear of contamination—

which led Americans to perceive their own entanglement with material ecological networks, and

generated ecological awareness—to advance a new form of psychoterratic illness that emerged

during the Cold War: ecological anxiety.

Chapter shows how Ann Pancake’s Strange as This Weather Has Been (2007)

conceives of the slow violence (Nixon 2) associated with mountaintop removal as a contributor

to both ecological grief and anxiety. Pancake’s novel then suggests that psychoterratic illness can

be a multifaceted condition. As Pancake deliberately identifies the human mind as one of the

many casualties of prolonged ecological destruction, she calls for an overhaul in common

conceptions of what constitutes violence. Ecological destruction, that is, and other forms of

environmental injustice, ought to be regarded as violence, her novel suggests, with devastating

psychological consequences. It provides an apt point of closure for my project, for it asserts that

despite loss, there is hope for not only ecological restoration, but for psychic restoration as well.

If we continue to tell the stories of ecological loss, the novel and this project as a whole suggest,

we afford this kind of loss the urgency it deserves. In so doing, we also render ecological objects

of loss as grievable, and thus inherently valuable.

xxxi

These novels illuminate the profound connections between humans and their

environments and reveal the tremendous stakes, for both humans and their environments, of

developing an environmental ethic wherein individuals might conceive of themselves as entities

that affect and are affected by the places they inhabit. In hopes of providing an answer of sorts to

the damage that the dualism between humans and environments advances even still, this

dissertation will question and deconstruct the human/environment dualism, which still plagues

much contemporary American environmental thought. The sort of environmental ideology that

delineates human from environment is evident as early as the Old Testament, wherein which

God grants man dominion over nature. American environmental thought has been dominated by

a conception of human and nature as separate entities since the U.S.’s imperialist, colonial

beginnings. For early Americans settling the frontier, “wilderness” was distinctly separate from

civilization. These early Americans did not consider themselves a part the natural world but

rather as what Roderick Nash calls “masters and not members of the life community” (xii). This

“ecological superiority complex” led to the conception of wilderness as adversary, target, or

object ripe for exploitation, rather than an entity of which humans were a part (Roderick Nash

xiii). Aldo Leopold’s 1949 commentary on the overarching, national understanding of the human

relationship to the environment in A Sand County Almanac points to this dualism’s persisitence

over time. He notes that Americans regarded nature “as a commodity belonging to us” (vii)

rather than as a community to which we belonged. However, when Carson illuminated the way

that environments can affect human prosperity, Americans began to conceive of their

relationship to the environment in new ways. Suddenly, Americans began to understand the

environment as more than a resource, playground, or a space in need of taming. Rather, they

began to see themselves as connected to it in some way and understand their own well-being as

xxxii

reliant on its welfare. This dissertation will show how contemporary American literature

deepened this conception of the material and psychological connections between human and

environment.

With the Earth in Mind ultimately underscores literature’s ability to precipitate a

decentering of the human, or a removal of the human from the privileged yet self-destructive

position humanism has afforded our species. An engagement with the literary tradition I trace

herein asks that humans interrogate their practices of thinking and being in the world, which

elevate them above other nonhuman animals and living organisms. Engagement with this

literature can prompt its readership to recognize the interdependent relationship between humans

and the ecosystems they inhabit, and thus stands to aid in the eradication of what remains of the

dangerous dualism that pits human against environment, and stands in the way of a sustainable

environmental ethic. This dualism allows humans to skirt environmental responsibilities—most

notably the responsibility to sustain the material environments of which we are a part. This

tradition of postwar and contemporary American novels enables a greater understanding of earth

and self as interconnected, and promotes alternative epistemologies. Moreover, it positions the

humanities, and literature in particular, as a critical mode of ecological inquiry that is crucial to

the advancement of alternative modes of sustainable and ethical ecological conduct.

xxxiii

CHAPTER

THE WOUNDS OF DISLOCATION: NATIVE AMERICAN DISPLACEMENT AND

ENVIRONMENTALLY-INDUCED MENTAL ILLNESS IN KEN KESEY’S ONE FLEW

OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST

I can see all that and be hurt by it, the way I was

hurt by seeing things in the Army, in the war. The

way I was hurt by seeing what happened to papa

and the tribe. I thought I’d get over seeing those

things and fretting over them. There’s no sense in

it. There’s nothing to be done.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

In 1962, Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, a narrative that emphasizes the

interconnectedness of human and environment as it sheds light on the slow and continuous

poisoning of both entities by the pesticide DDT, among other toxins and chemicals. Since its

release, Silent Spring has been lauded as one of the most influential environmental works of the

twentieth century, and is often credited with prompting the environmental movement in the

United States. Carson’s illumination of the horrifying processes by which human bodies

ultimately ingest toxins introduced into the environment gave way to the concept of ecological

health and ultimately engendered a new way of understanding the human relationship to the

environment as reciprocal and interdependent.

Published the same year as Carson’s invaluable work, Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the

Cuckoo’s Nest similarly posits a human interconnectedness to place and suggests that the

devastating effects of damage to one entity—either environment or human—wreak havoc on the

other. And yet Kesey’s novel nuances and even augments Carson’s thesis as it illuminates

environmental degradation’s potential to adversely affect not only the human body, but the

human mind as well. While Carson conceives of environmental contaminants permeating the

material human body, she makes no mention of the effects of such environmental assaults on

1

mind, which we can at once interpret as matter and at the same time must recognize as something

more complicated. Furthermore, she overlooks how the damage done to one’s environment

might affect one’s psychological health, perpetuating the mind/body binary that drives a majority

of Western master narratives. Cuckoo’s Nest deconstructs this binary as it suggests that

environmental degradation perpetuates mental degradation. The novel extends traditional

concept of environmental illness as impacting more than just the corporeal body as it presents

characters that experience the degradation of their homeplace, as well as ultimate displacement

from it, and as a result suffer from significant psychological harm.

Specifically, the novel evidences the experience of environmentally-induced trauma

through the mental breakdown and eventual death of narrator Chief Bromden’s father, Tee Ah

Millatoona, or “The-Pine-That-Stands-Tallest-on-the-Mountain” (Kesey, Cuckoo’s Nest 188)—I

will refer to him henceforth as “the elder Chief”—as well as the traumatic flashbacks of

homeplace degradation and environmental exploitation that Chief Bromden himself experiences

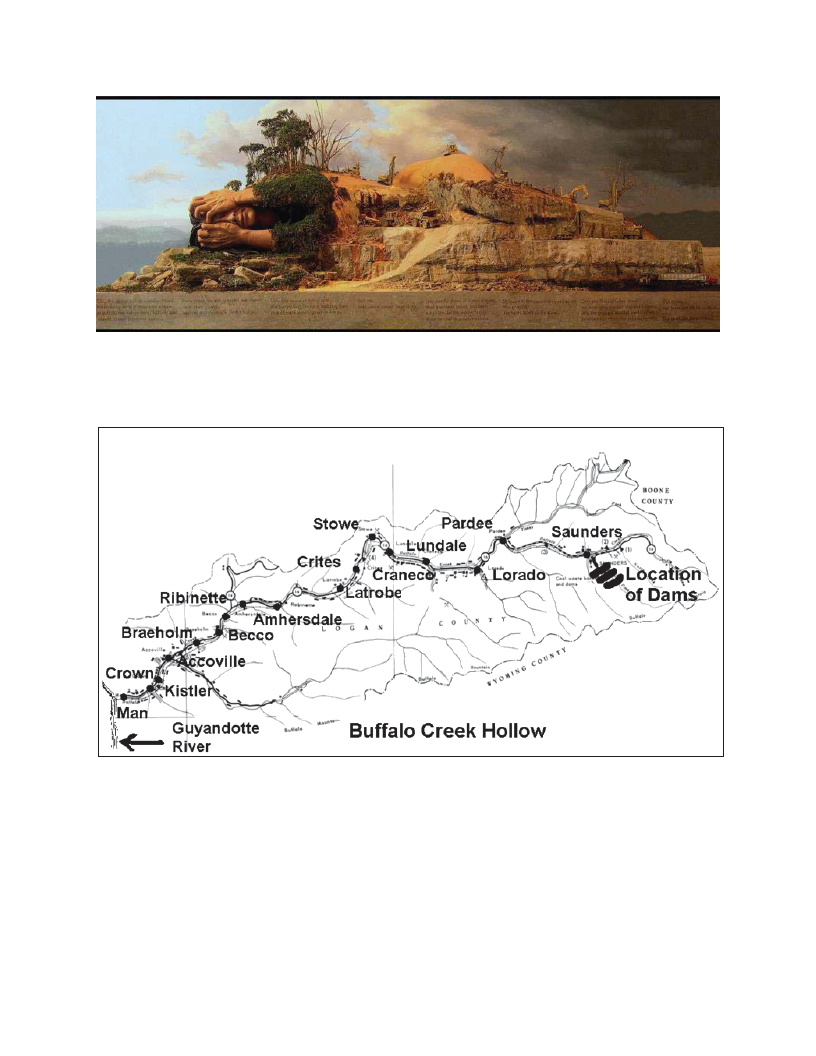

while on the Ward. The elder Chief’s demise coincides with the damming of Celilo Falls on the

Columbia River, an historical American event that occurred in 1957. The novel depicts the

environmental and cultural degradation that results as traumatic for the elder Chief, and

presumably the other members of the tribe.

The Chief, too, experiences the damaging psychological impacts of his homeplace’s

degradation and his displacement from it. He at once witnesses his father’s breakdown, and is

moreover disassociated from his homeplace by way of his time serving in the war and living on

the ward. The amalgamation of these experiences, the novel suggests, lead to his mental decline.

In fact, the Chief’s flashbacks mirror the kind of episodes a veteran might experience as a result

of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, yet these moments force the Chief to re-live not his wartime

2

exposures but the incidents surrounding he and his tribe’s dispossession and displacement.

During one of these episodes he explains, “It—everything I see—looks like it sounded, like the

inside of a tremendous dam. Huge brass tubes disappear upward in the dark. Wires run to

transformers out of sight. Grease and cinders catch on everything, staining the couplings and

motors and dynamos red and coal black” (77). “There’s a rhythm to it,” says the Chief, “like a

thundering pulse” (78). The thundering, pulsing rhythm of the machine the Chief recalls in this

flashback suggests the overpowering and routine reality of postwar industrialism, which is

endemic and inescapable, and has the power to destroy both the natural world and its inhabitants.

As the novel presents the concurrent breakdown of environmental and human mental health

among these prominent Native figures in Cuckoo’s Nest, it ultimately positions the state of one’s

homeplace and environmental surroundings as fundamental to human well-being, and suggests

more broadly that the effects of environmental degradation on the human are more extensive

than we have traditionally imagined.

Chapter Overview

This chapter will position Cuckoo’s Nest historically as complicating Carson’s invaluable

argument and thus as a text that deserves examination alongside the environmental luminary

Silent Spring as it complicates and contributes to conceptions of ecological health and material

connections between humans and their environments. First, this chapter will provide an overview

of Silent Spring and the ways in which this text reconstituted Americans’ understandings of

environmental degradation as extending consequentially beyond the material environment to

affect the material self. By historicizing the state of environmental affairs in the postwar United

States, an understanding of the moment into which Kesey introduced his Native figures becomes

clear, as do the stakes of his textual argument, which I will suggest lends to a similar project to

3

that of Carson. Kesey’s novel, I will furthermore assert, has the potential to advance Carson’s

project. Following the overview of Carson’s celebrated work, this chapter will postulate the state

of affairs among Native, Columbia River Gorge inhabitants whose home and sacred fishing

grounds were submerged when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed the Dalles Dam

on the Columbia River. In doing so, this chapter will illustrate the events Kesey witnessed

firsthand as child growing up in Oregon, which influenced Cuckoo’s Nest as they laid the

foundation for the novel’s underlying conflicts. In order to explain how and why an event like

the damming of Celilo Falls occurred, this chapter will advance an explanation of the state of

federal land management at the time the U.S. Department of the Interior proposed and undertook

the project. A reading of the text will follow, which will demonstrate how the novel deals with

Native American displacement and dispossession, along with the subsequent traumas that result,

all which come to bear on the novel’s larger argument that humans are connected to their

environments by way of not only their bodies, but moreover, by way of their minds. Finally, a

discussion of the field of Ecopsychology’s emergence in the late 1960’s will follow, as the field

specifically addresses the connections between the human mind and the natural environment.

Moreover, it provides a call to action that addresses the likelihood to repress and failure to attend

to what ecopsychologist Theodore Roszak calls a “defining feature of human nature”:

“[humans’] sympathetic bond with the natural world—the ecological unconscious’” (Voice of the

Earth 328).

Rachel Carson’s Ecology of Health

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring brought the truth about DDT to the attention of

uninformed Americans. An insecticide first used to treat malaria and typhus at the end of WWII,

4

the U.S. government later used DDT as a contact poison to combat the defilement of agriculture

by insects and arthropods. The U.S. government’s interest in preserving agricultural production

following the war’s end led to indiscriminate dissemination of the chemical, and it is this practice

with which Carson takes issue in Silent Spring. Carson’s concern for DDT’s potential harm to

not only the targeted environment but the entire biota inspired her to alert the public to the

presence of this environmental pollutant and its potential effects on the ecosystem. Of course, as

an integral part of any ecosystem, human beings were at risk. Carson’s text illuminates the

dangers that these newly introduced and widely disseminated chemicals posed to human bodies,

situating humans as not only agents, but also objects of change (Nash 7).

Carson’s argument situates her as an early progenitor of the environmental movement. In

the introduction to Silent Spring’s fortieth anniversary edition, Carson’s biographer Linda Lear

notes that Carson’s background in biology and ecology prepared her to describe to a more

general public what had up until the text’s publication had only been talked about in scientific

circles. For instance, Carson makes accessible such biological processes as “how chlorinated

hydrocarbons and organic phosphorous insecticides altered the cellular process of plants,

animals, and, by implication, humans” (Lear xv). Carson furthermore explains how “DDT

applied to a lake in northern California (to control gnats) was taken up by plankton, passed from

plankton to plant-eating fish, from plant-eating fish to carnivorous fish, from carnivorous fish to

grebes and gulls” (Nash 157). Ultimately, the chemicals that effected these grebes and gulls

affect humans who inhabit this landscape, Carson suggests. She thus argues that human bodies

are permeable and as a result are just as vulnerable to toxins as the rest of the targeted

environment’s non-human inhabitants are.

5

As she enlightened her audience, Carson situated the interrelationship between human

and environment as an exigent issue that required immediate action. She writes,

The central problem of our age has become the contamination of man’s total

environment with such substances of incredible potential for harm—substances

that accumulate in the tissues of plants and animals and even penetrate the germ

cells to shatter or alter the very material of heredity upon which the shape of the

future depends. (Carson 8)

At a time when the environment was excluded from the political agenda in the United States,

what famed Biologist E.O. Wilson calls “the Carson Ethic” became a worldwide political force

(361). Despite voicing her apprehensions at a moment when few wanted to hear them, Carson

sounded an audible alarm and positioned the conservation of natural environments as a serious

national—and even international—concern. Carson sought to remedy the “limited awareness of

the nature of the threat” during an “era dominated by industry, in which the right to make a

dollar at whatever cost is seldom challenged” (Carson 13). Of course, the government spent a