This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-ND 4.0 International) license

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0

2022, 20, 1: 25-37

p-ISSN 1733-1218; e-ISSN 2719-826X

DOI http://doi.org/10.21697/seb.2022.05

Ecophilosophical and Ecopsychological Aspects of Sustainable Consumption

and Lifestyle

Ekofilozoficzne i ekopsychologiczne aspekty zrównoważonej konsumpcji i stylu życia

Mikołaj Niedek

National Institute of Rural Culture and Heritage, Poland

ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5241-5150 • mikolaj.niedek@nikidw.edu.pl

Received: 28 Feb, 2022; Revised: 10 Apr, 2022; Accepted: 13 Apr, 2022

Abstract: The aim of the article is to outline the philosophical and psychological dimensions of a sustainable lifestyle

based on responsible consumption. In the author’s opinion, moderate consumption and an ecologically balanced way

of living should, for their durability, have a broader mental and worldview background. The article will present and com-

pare the concepts of the eco-philosophy of Henryk Skolimowski and the ecopsychology of Theodore Roszak in terms

of cognitive, ideological, and axiological propositions of these concepts that can form the motivating basis for respon-

sible living on Earth. In the author’s opinion, apart from the economic dimension, the adoption of ecological ethics and

of ecological sensitivity is crucial for the permanent rooting of sustainable consumption patterns in people’s attitudes.

Ecophilosophical and ecopsychological concepts can significantly help in this, contributing to human sensitivity to envi-

ronmental issues related to the contemporary ecological crisis. The ecophilosophical and ecopsychological approach, in

the author’s opinion, need each other because they use complementary perspectives and methods of building ecological

awareness. In the process of environmental education and shaping sustainable life attitudes, they are equally necessary

for the effectiveness of achieving the goals of education for sustainable development and promoting an environmentally

responsible lifestyle in society.

Keywords: sustainable consumption, sustainable lifestyle, ecophilosophy, ecopsychology, eco-ethics, frugalism

Streszczenie: Celem artykułu jest zarysowanie filozoficznego i psychologicznego wymiaru zrównoważonego stylu życia

opartego na odpowiedzialnej konsumpcji. Zdaniem autora, umiarkowana konsumpcja i ekologicznie zrównoważony styl

życia powinny mieć, o ile mają być trwałe i stabilne, szersze podstawy mentalne i światopoglądowe. Artykuł porównuje

koncepcje ekofilozofii Henryka Skolimowskiego i ekopsychologii Theodore Roszaka pod kątem ich propozycji poznaw-

czych, ideowych i aksjologicznych, które mogą stanowić motywującą podstawę dla praktyki odpowiedzialnego życia ludzi

na Ziemi. Zdaniem autora, dla trwałego zakorzenienia wzorców zrównoważonej konsumpcji w postawach, oprócz wymiaru

ekonomicznego, kluczowe jest przyjęcie etyki ekologicznej i kształtowanie wrażliwości środowiskowej. Koncepcje eko-

filozoficzne i ekopsychologiczne mogą w tym znacząco pomóc, przyczyniając się do zwiększania wrażliwości człowieka na

kwestie związane ze współczesnym kryzysem ekologicznym. Zdaniem autora, podejścia ekofilozoficzne i ekopsycholog-

iczne potrzebują się nawzajem, ponieważ wykorzystują uzupełniające się perspektywy i sposoby budowania świadomości

ekologicznej. W procesie edukacji ekologicznej i kształtowania zrównoważonych postaw życiowych są one w równym stop-

Mikołaj Niedek

26

niu niezbędne dla skuteczności osiągania celów edukacji na rzecz zrównoważonego rozwoju i upowszechniania w społec-

zeństwie odpowiedzialnego ekologicznie stylu życia.

Słowa kluczowe: zrównoważona konsumpcja, zrównoważony styl życia, ekofilozofia, ekopsychologia, ekoetyka,

frugalizm

Introduction

Consumption is a complex phenomenon,

process and system that can be charac-

terized in economic terms but go beyond

strictly economic aspects. The economic

base of consumption is formed by the struc-

ture of the consumer’s income and savings;

the type and quantity of goods and services

available on the market and purchased

by the consumer; the existing infrastruc-

ture and logistics of consumption (supply

chains, enterprises, sales points); as well as

general conditions, such as the level of eco-

nomic development and the rate of inflation.

The non-economic determinants of con-

sumption include broader social and cultural

factors: prevailing habits, fashions, trends,

value systems and ideologies functioning in

society. In the era of global challenges and

contemporary ecological crisis caused by

the dominant (industrial) economic model,

normative goals for consumption are formu-

lated by the concept of sustainable develop-

ment. Within the Millennium Sustainable

Development Goals adopted by the United

Nations in 2015 and set to be achieved by

2030, it is directly related to goal no. 12:

Ensure sustainable consumption and pro-

duction patterns. A durable pattern of con-

sumption that meets the sustainability

criteria can be defined conjunctively as

(Niedek 2009, 31):

a. consumption of a sufficient number

of goods and services to meet real needs

and achieve a high quality of life, with-

out unnecessary waste of products, ma-

terials, and energy;

b. consumption with a preference towards

ecologically and socially sustainable

products;

c. dematerialising (minimising and saving)

the use of natural resources and prefer-

ring the consumption of services rather

than things.

The opposite of sustainable consumption

is unsustainable consumption, which can be

characterized as:

a. consumption of goods to an extent

which is excessive in relation to the nec-

essary needs and on a larger scale than

required by an adequate quality of life,

resulting in a waste of resources and

energy;

b. consumption of unsustainable prod-

ucts – directly or indirectly harmful

to the environment and to the health

of the people producing and consuming

them;

c. excessive use of resources, raw materials,

water and energy in relation to the pro-

ductive capacity of the environment and

its ability to assimilate pollution and

waste.

Unsustainable patterns of consumption

dominate the modern economy and West-

ern societies and are responsible for the deg-

radation of the natural environment. Along

with the widening scale and manifestations

of the ecological crisis – the global loss

of biodiversity, increasing pollution of wa-

ters, soil, air, and food, as well as the climate

crisis – the need to change the unsustaina-

ble consumption patterns is becoming more

and more urgent. The formulated directions

of the necessary changes are becoming rad-

ical and they are formulated in an increas-

ingly alarmist tone (Skubała and Kulik 2021).

Analyzes summarizing the activities aimed

at sustainable consumption so far show that

most of them are ineffective and require

adopting new approaches and implementing

Ecophilosophical and Ecopsychological Aspects…

27

innovations in the functioning of societies

and people’s lifestyles (Cohen 2019).

Dariusz Kiełczewski and others dis-

tinguish three psychological dimensions

of consumption: cognitive, emotional, and

behavioural, which are interconnected.

A responsible consumer is the one who has

specific consumer competencies defined

as “the theoretical knowledge and practi-

cal skill, distinguishing a given person with

easiness of an efficient, effective, respond-

ing to qualitative expectations, fulfilment

of needs of lower and higher rank while

maintaining responsibility for the choices

being made” (Kiełczewski et al. 2017, 107).

The essence of competences as regards sus-

tainable consumption is “an optimal recon-

cilement of personal, social and ecological

roles by the consumer. It is about setting

up a synthesis – to make that the proper

fulfilment of the social and ecological role

was for the consumer a source of their per-

sonal satisfaction and something that raises

the general state of satisfaction with the liv-

ing quality and standard they have reached”

(Kiełczewski et al. 2017, 106). In this psy-

chological aspect, sustainable consumption

contributes to an increase in the quality

of life, i.e., establishment of an optimal bal-

ance between material consumption and

satisfaction of intangible needs (Kiełcze-

wski 2004, 58). The dividing line in this

sphere is marked by Fromm’s life attitudes:

“to have” and “to be” (Kiełczewski 2007, 38).

It is important, because “behaviours aimed

at sustainable consumption are in great con-

flict with the hitherto adopted lifestyles and

purchasing preferences, so, they require

a complete change of behaviour and mental

habits” (Kiełczewski et al. 2017, 106). Paral-

lel to the necessary changes in the economic

system of production-consumption, changes

are needed in the systems of values, world-

view, and culture.

A comprehensive study of the determi-

nants of sustainable consumption leads

to its broader aspects and to the concept

of a sustainable lifestyle. This category cov-

ers a) external conditions: social, cultural,

economic, political, and environmental; b)

internal conditions: cognitive, ideological,

axiological; c) psychological: personal, emo-

tional and subjective. So, the lifestyle based

on sustainable consumption is conditioned

by many different factors and can be ana-

lyzed from many perspectives; it also has

fairly extensive literature (Lubowiecki-Vikuk

et al. 2021). According to Jensen, an analy-

sis of lifestyle in the context of sustainable

consumption requires an inquiry into values,

motives, personality traits, behaviours, hab-

its, and identification of socio-cultural rela-

tions (Jensen 2007). An adequate approach

to the analysis and implementation of a sus-

tainable lifestyle requires therefore human-

istic, in particular philosophical (including

axiological and ethical) as well as psycholog-

ical insights. The quality of life and well-be-

ing are the central categories that mediate

the economic, philosophical and psycho-

logical approach to sustainable consump-

tion and lifestyle. From the psychological

perspective, the sensitivity and emotional

dimension, related to well-being, is of par-

ticular importance.

From a narrow economic perspective,

to change consumer behavior and attitudes

towards a more environmentally friendly

one, it is enough to have access to informa-

tion on the environmental effects of a given

consumption pattern and to better inform

the consumer about the quality parameters

of the purchased products and their envi-

ronmental impact. According to ecologi-

cally oriented philosophy and psychology,

the following are necessary a) a deeper di-

agnosis of the causes of consumerism and

excessive human interference with nature;

b) deeper rooting of pro-ecological attitudes,

motivations, and behaviors in the structure

of human consciousness and mentality – in

the consumer’s value system and in his eth-

ics. Otherwise, pro-ecological behavior will

be shallow and will be a passing phenome-

non, susceptible to ideologies and fashions.

Broader concepts of ecological philosophy

and environmental ethics were formed

in the West from the 1970s. A little later,

Mikołaj Niedek

28

psychological propositions began to emerge,

arguing that the condition of ecological

change should be a change at the personal-

ity level, noting a deep connection between

the nature of man and Nature. An example

of comprehensive eco-philosophical propos-

als relating to the issue of consumption and

postulating ethical regulations are the deep

ecology of a Norwegian philosopher, Arne

Naess (1912-2009) and the eco-philoso-

phy of the Polish philosopher working in

the USA, Henryk Skolimowski (1930-2018).

The works of Paul Shepard (1925-1996) and

Theodore Roszak (1933-2011) are an example

of parallelly formulated ecological proposals

reaching fundamental worldview and axio-

logical changes, on the basis of broadly and

holistically understood psychology, which

will be outlined below.

1. Ecophilosophical foundations

of a sustainable lifestyle

The important stimulus for the development

of ecological reflection in philosophy and

other fields of social sciences and human-

ities was the growing awareness of threats

related to the development of technical civ-

ilization and its negative impact on the bio-

sphere (Waloszczyk 1996, 200). Ecological

issues were taken up on the basis of many

humanities and social sciences, leading

to the emergence of their pro-ecological

trends and fields (Kiełczewski 2001). In

terms of philosophy, one of the most popu-

lar and widespread concepts is deep ecology,

created in the early 1970s by Arne Naess and

later developed by Bill Devall and Georges

Sessions. This philosophy is characterized

by eight principles formulated by its authors,

four of which concern the need to change

consumption and production patterns

to more ecologically sustainable (Devall and

Sessions 1985):

• Humans have no right to reduce the rich-

ness and diversity of life forms except

to satisfy their vital needs.

• Policies must therefore be changed.

The changes in policies affect basic eco-

nomic, technological, and ideological

structures. The resulting state of affairs

will be widely different from the present

situation.

• The ideological change is mainly that

of appreciating life quality (dwelling in

situations of inherent worth) rather than

adhering to an increasingly higher stand-

ard of living. There will be a profound

awareness of the difference between big

and great.

• Those who subscribe to the foregoing

points have an obligation directly or indi-

rectly to participate in the attempt to im-

plement the necessary changes.

The educational process should, according

to Naess, result in resistance to the forces

of consumerism: advertising, mass culture,

and hyperconsumption (Naess 1992). Ac-

cording to A. Neale, the main goal of the cre-

ators and practitioners of ecophilosophy was

to change the awareness of people. Exces-

sive consumption was perceived as a lack

of well-educated eco-awareness, which in

turn resulted in a lack of the need to make

more environmentally friendly choices

(Neale 2015, 150). Henryk Skolimowski in

his first manifesto of eco-philosophy, en-

titled Ecological Humanism, formulated

the general idea of “The World as Sanctu-

ary” (Skolimowski 1974). According to him,

the basis of any worldview, be it mytholog-

ical, philosophical or scientific, is Cosmol-

ogy – understood as the basic assumptions

and the most general knowledge and beliefs

about the world – what exists and the pos-

sibility of getting to know it. The core

of any cosmology is the main metaphor on

which the most general assumptions about

the world are based. In the case of modern

cosmology, it was a Newtonian-Cartesian vi-

sion of the world as a great clock, operating

according to mechanistic and deterministic

laws. From a given cosmology, a specific phi-

losophy emerges, postulating certain values,

and these mainly affect the directions of ac-

tivities undertaken by man (Skolimowski

1992, 12).

Ecophilosophical and Ecopsychological Aspects…

29

Cosmology Philosophy Values Action

Fig. 1. Relationships between Cosmology, Philosophy, Values and Action according to Henryk

Skolimowski.

The eco-cosmology postulated by Skoli-

mowski is based on a vision of the World

as a place endowed with the sanctity of Life,

opposite to mechanicism and determinism.

It is the basis of the eco-philosophy, which

Skolimowski understood metaphorically as

the tree of life, and practically as a system-

atic drawing of consequences from the very

assumption that the world is a sanctuary

(Skolimowski 1999). In this concept, man

and mind, as well as their spirituality, are

a natural result of cosmic evolution, under-

stood as a process of increasing complexity

aimed at the emergence of biological and

psychical life, and then noetic (mental) life.

In terms of eco-cosmology, the Cosmos

(the Universe) is an ontological extension

of Oikos, being the place and home of man

and other living creatures1.

A feature that distinguishes humans from

other species is the mind, awareness, and

self-awareness as well as creativity, and

the ability to take responsibility for one-

self and one’s surroundings. Skolimowski

considered the emergence of ecological

consciousness – symbiotic towards the to-

tality of life and the world, which opposes

the exploitative and dominant mechanistic

consciousness, alienating, dividing, and fo-

cused on the particular interests of the indi-

vidual, group, and species – as the key stage

of noetic evolution. Man’s realization of be-

longing to a larger whole, which is the eco-

logical environment, sensitivity to its state,

and taking responsibility for its well-being

and future, is a turning point in the process

of evolution of the human species. The eco-

logical transformation of our mentality, cul-

ture, and civilization is the condition for

human survival, which he often expressed in

1 A science that develops an interdisciplinary,

natural and humanistic view of the environment

and the Cosmos as a place of human existence is

Cosmoecology (Korpikiewicz 2020).

the statement that “the 21st century will be

an ecological century, or it will not be at all”.

The ecological awareness emerging at

the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries is part

of a new, holistic, and ecological paradigm,

which is also participatory. New values

emerge from it, which should guide an eco-

logical man (Homo ecologicus) in his actions.

Ecological and ethical behavior is a form

of human participation in the world, which

is conducive to both physical and mental

health, as well as to maintaining the balance

and sustainability of the environment. Skoli-

mowski sees the sources of mental disorders

in disorders of the participation of the natu-

ral part, which is man, in the whole of the bi-

otic community (community of life): “Our

modern times are afflicted with all kinds

of mental diseases and disorders because

human beings have been denied the right

to participation. An outburst of various

forms of therapy in our times is a hidden re-

sponse of life to reestablish the right to par-

ticipation. All therapy is an attempt to bring

the person back to meaningful forms of par-

ticipation” (Skolimowski 1994, 182).

Participation is a way of restoring a dis-

turbed balance and healing damaged rela-

tions between a person and his environment.

It makes possible to overcome pathological

individualization and alienation of man from

the community of being and Life on Earth.

In the cosmological dimension, the holis-

tic participation means conscious presence

of the mind in the world (Cosmos) and par-

ticipation of the world in the mind, without

which it is inconceivable. The world is not

only passively reflected in the mind as in

a mirror but is created by the mind through

its sensitivities: sensual, emotional, cognitive,

spiritual. It is through us, beings endowed

with mind and various sensitivities, that

the Cosmos gets to know and contemplate

itself. This shows the fundamental, organic

Mikołaj Niedek

30

unity of man with the place of his birth and

life – the World. Forgetting about this rela-

tionship, man alienates himself from Nature

and himself, suffering enormous spiritual

losses, which he wants to compensate for

with excessive consumption. In this ap-

proach, the world is treated as a collection

of exchangeable resources, and development

is understood as progress in their appropri-

ation and commercialization, in the name

of never-ending growth and consumption.

As Ignacy S. Fiut sums it up: “How-

ever, a quick pace of life causes a drop in

its quality, namely the occurrence of mass

stress, civilisational, mental and spiritual

diseases, cultural de-rooting and social al-

ienation, mainly due to the media that keep

false euphoria among people, which, as

a consequence, has unleashed on the mass

scale existential fear that is concealed under

the enhanced and redundant consumption.

(…) In Skolimowski’s assessment, the main

cause of this is the lack of spiritual balance

in people. It is well reflected in modern

art, and which results in loss of awareness

of the need for responsible self-limitation

in action, self-development, and therefore

the ability of creative self-realisation, thus

as a consequence they resolve to unlimited

freedom of choice, realised in the unlimited

forms of consumption” (Fiut 2009, 39, 42).

By analyzing the causes of the disturbing

relationship between humans and the envi-

ronment, Skolimowski identified the source

of this disorder, like many other ecophilos-

ophers, in a mechanistic paradigm, founded

at the beginning of the modern era by F. Ba-

con, Galileo, Descartes, and Newton. This

paradigm resulted in a reductionist image

of the world, implying an instrumental, ma-

nipulative and exploitative attitude towards

nature and people, as well as towards knowl-

edge and cognition (scientia est potentia),

promoting such values as: effectiveness, ef-

ficiency, controllability, instrumentalization,

use and progress. According to Skolimowski,

these values are embodied in modern tech-

nology, in which the instrumental and con-

quering approach to the world, treated as

a collection of things to be used, reaches its

apogee.2 They stimulate the materialistic

economy of continuous production and con-

sumption growth, at the expense of the envi-

ronment (consumerism) and at the expense

of spiritual development, culture, and au-

totelic values. It results in an ecological,

social, psychological, and cultural crisis

manifested in the relativism and nihilism

of the postmodern era. Although he created

eco-ethics as practical guidelines for respon-

sible and committed behavior in the era

of the ecological crisis, Skolimowski did not

develop the psychological and therapeutic

threads of his eco-philosophy. Therefore, it

is worth considering the main assumptions

of pro-ecologically oriented psychology

(ecopsychology) against this background.

2. Ecologically sensitive psychology

The authorship of the term ecopsychology

and the creation of its main concept is at-

tributed to Theodore Roszak, an Ameri-

can historian of ideas who became famous

for his analysis of youth movements in

the 1960s as Counter Culture. However,

the first systematic reflections on psycho-

logical grounds on the causes of the contem-

porary ecological crisis were carried out in

the 1970s by Robert Greenway, postulating

the concept of psychoecology (Greenway

1995) and Paul Shepard. A comprehensive

interpretation of green psychology was also

presented by an American psychologist

Ralph Metzner (Metzner 1999)3. According

2 In this perspective, Skolimowski would also

criticize the so-called transhumanism aiming at

human cyborgization and the maximum technici-

zation of life.

3 The name “ecological psychology” was already

used in the 1950s – 1960s for research on human

perception and behavior in natural surroundings

(outside the laboratory) by researchers such as Ja-

mes Gibson, Roger Barker, and Urie Bronfenbren-

ner. Although their approach was characterized

by a departure from behaviorism, a systemic and

holistic approach, and emphasizing the importance

of the environment for human and his development,

strictly ecological themes were essentially absent in

their research and works (Bańka 2002).

Ecophilosophical and Ecopsychological Aspects…

31

to Shepard, the key issue of ecopsychology is

the question of why man destroys his habi-

tat – the environment of his life at all. In his

opinion, in order to understand destructive

human behavior, it is not enough to know

the history of ideas, although we are cur-

rently dealing with the largest gap in his-

tory between the dominant philosophy and

the Earth (Shepard 1998, 2-3).

However, Shepard did not see the sources

of the contemporary crisis in the relation-

ship between man and the environment in

the modern dualism, but several thousand

years earlier, on the threshold of the Neo-

lithic era, when an agricultural civilization

emerged, and the lifestyle of the human spe-

cies changed from hunter-gatherer to sed-

entary. The increasing scale of nature’s

transformation over time has led to the cre-

ation of a completely artificial environment,

that does not correspond to human nature

or our biological and psychological needs.

According to Shepard, this prevents natu-

ral development and maturity, resulting in

the structural alienation of man from nature

and psychological consequences in the form

of mental disorders and diseases. Civili-

zation madness (title of Shepard’s book) is

the opposite of natural order and ecological

balance.

According to Shepard, the expression

of the childhood immaturity of mankind is

fantasizing about omnipotence and eternal

expansion, narcissism, and egocentrism, not

distinguishing between reality and fiction,

illusions, inconsistency, and irresponsibil-

ity. These features have become a perma-

nent element of the personality of modern

man. Civilization and its institutions have

created systems to sustain this immaturity.

An example is an economic system based on

compulsive consumption. It is supported by

the Western mentality (especially, as Shep-

ard emphasizes, the American), which is

characterized by obsessive overconsumption,

waste and a desire to achieve immediate

gratification here and now. The psycho-

logical effects of immaturity are, accord-

ing to Shepard: escape into addiction and

escapism, violence and destruction, depres-

sion, indiscriminate use of psychotherapy,

susceptibility to manipulation. The ecolog-

ical effect is the destruction of the natu-

ral environment, unprecedented in history.

The overeating the world becomes an un-

conscious, desperate substitute for self-de-

velopment. Contemporary man is plunged

into insane helplessness, unaware of his own

and ecological boundaries and the possibil-

ities of his internal development, destroying

himself, the world, and his future (Roszak,

Gomes and Kanner 1995, 32).

Contrary to P. Shepard, Theodore Roszak

did not see the causes of the contemporary

ecological crisis until the agrarian revolution,

but like the vast majority of ecophilosophers

in expansive western culture and in dualism

that has dominated the western cognitive

paradigm from the second half of the 17th

century. According to Roszak, the Western

system of values aims at control, domina-

tion, manipulation, and effectiveness that is

responsible for the destructive attitudes and

actions of humans towards the environment,

people, communities and other cultures.

The aim of his project of ecopsychology is

to build a bridge between the Person and

the Planet, between the external (world)

and the internal (soul), between ecology and

psychology. The division into internal (men-

tal) and external (physical) reality negates

the obvious fact that the mental is also in-

side the world (in the world), and the world

is reflected in our mind.

At the deep level that ecopsychology tries

to reach, human nature is connected with

the nature of the world – Nature. There-

fore, the suffering of nature caused by hu-

man interference, and on a global scale

by the expansion of civilization, mani-

fests itself through us in the form of suf-

fering of the soul, which are various kinds

of mental disorders and diseases. It follows

that without healing the environment, it

will not be possible to eliminate the causes

of the modern epidemic of mental disor-

ders and diseases resulting from an increas-

ingly degraded environment. The voice and

Mikołaj Niedek

32

scream of the Earth, in the title of Roszak’s

main opus, manifests itself through us, hu-

mans, through our sensitivity and conscious-

ness, and through the suffering of the Earth

through the diseases that affect us as a result

of a polluted and unhealthy environment.

According to Roszak, the source of many

contemporary mental disorders is the patho-

logical relationship between humans and na-

ture. The psychopathology of our everyday

life is created by ecological problems: global

warming, increasing environmental pollu-

tion, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, etc.

Roszak draws attention to the fundamen-

tal pathology of urban-industrial culture

and, at the same time, to the ineffective-

ness of the actions based on the “shock and

shame” strategy and rational argumentation,

taken so far to counteract the destruction

of the environment. This, in his opinion, is

similar to admonishing a pyromaniac “that

he sets fire”. Roszak explains environmen-

tally destructive consumerism in psychologi-

cal terms as compensation for the alienation

of man from the Whole, Meaning and Na-

ture. He also notices, like Skolimowski,

the basic ties between the adopted vision

of a person’s place in the world (in the Cos-

mos) and the fundamental sense of existen-

tial meaning.

According to Roszak, ecopsychology is

a science, which will help us to understand

both the deep meaning of our mental suf-

fering related to experiencing the ecological

crisis and destroying the diversity of Life on

Earth, as well as designing effective ways

of overcoming this crisis. To do this, ac-

cording to Roszak, culture must change,

because the mere awareness of the sources

of the contemporary crisis and reflection on

its causes and effects is not enough. Roszak,

therefore, sees the causes of the present cri-

sis in human relations with the environment,

and its prospective cure, in culture.

Unlike Skolimowski, he sees the key role

in the transformation of our culture into

a more pro-ecological one, not in philoso-

phy, but precisely in psychology, although

it sets goals and tasks similar to those

of Skolimowski: “The great changes our

runaway industrial civilisation must make if

we are kept the planet healthy will not come

about by the force of reason alone or the in-

fluence of the fact. Rather, they will come by

way of psychological transformation. What

the Earth requires will have to make itself

felt within us as if it were our own most pri-

vate desire. Facts and figures, reason and

logic can show us the errors of our present

ways; they can delineate the risks we run.

But they cannot motivate, they cannot teach

us a better way to live, a better way to want

to live. Thus, must be born from inside our

own convictions (…) A modern science

of the soul that is adequate to its task must

minister to that discontent as something

that is more and other than sexuality-based,

family-based, or socially-based. In our time,

the private psyche in its search for sanity

needs a context that embraces all that sci-

ence has to tell us about the evolution of life

on Earth, about the stars and the galaxies

that are the distant origin of our existence.”

(Roszak 1992, 47).

In the need of this invigorating cosmo-

logical and ecological knowledge as the ba-

sis for the ecological transformation of our

mind (metanoia), Roszak converges essen-

tially with the vision of Skolimowski, who

believed that we are the eyes of the Cos-

mos, through which the Cosmos knows it-

self. According to Roszak, we are the voice

of the Earth, through which our planet

obtains its awareness and self-knowledge.

By getting to know our planet and the en-

tire cosmos more broadly, we get to know

ourselves and our genesis. The awareness

of the beauty and wonder of existence

and the world builds our strength to resist

the destruction that ecological (and cosmo-

logical) ignorance causes in our environ-

ment. Roszak notices that the needs of our

soul are analogous to the needs of nature;

we need mental health, the balance of mind,

and peace of the soul, just as natural eco-

systems need undisturbed functioning (ho-

meostasis). A summary of the differences

and common elements of Skolimowski’s

Ecophilosophical and Ecopsychological Aspects…

33

eco-philosophy and Roszak’s ecopsychology

is presented in Table 1.

In addition to extensive analyzes of the

genesis of the contemporary crisis in the re-

lationship between Man and Nature, Roszak

included a synthetic interpretation of his

ecopsychology in eight principles. They say

that the path to ecological awareness leads

through awareness of the content of the eco-

logical unconscious, which includes the nat-

ural history of the evolution of the Cosmos,

Earth, and Man. Just as the aim of earlier

therapies was to discover the repressed con-

tents of the human unconscious, the aim

of ecopsychology is to awaken the innate

sense of interdependence with nature, hid-

den in ecological ignorance. Ecopsychology

seeks to heal the more fundamental alien-

ation between the recently formed urban

psyche and the centuries-old natural en-

vironment. Roszak recommends a return

to children’s and women’s sensitivity to na-

ture – creating an ecological Self from child-

hood, through sensitizing children to nature.

Shaping ecological responsibility for the en-

vironment should be a function of an eco-

logical Self. In his opinion, anything that

contributes to the development of small so-

cial forms and the acquisition of personal

power strengthens the ecological Self, and

anything that leads to large-scale dominance

and suppression of personal power under-

mines the ecological Self.

Breaking unity and harmony with nature

is traumatic, making modern man sus-

ceptible to all addictions, the most telling

example of which, according to C. Glend-

inning, is the dependence on technology:

a technocentric, technocratic and addictive

psycho-socio-economic system embodies

the mechanistic principles of standardi-

zation, linearity, efficiency, fragmentation

(Glendinning 1995, 45). Artificial and driven

by an obsessive rule of consumption and

a continual increase in productivity, the so-

cio-economic environment produces

an “All-Consuming Self ” that eats away at

the planet Earth and its future. The unre-

strained and unsatisfied rule of consump-

tion is proportional to the inner, spiritual

emptiness that results from the unfulfilled

natural and deep needs of belonging, union,

and love. It is the absorbing and dominant

Self that M.E. Gomes and A.D. Kanner re-

fer to as “Separative Self ” – separated from

the wider social and ecological context

(Gomes and Kanner 1995, 115).

Since its initiation by Roszak, ecopsy-

chology has developed both towards a bi-

ocentric radicalization inspired by deep

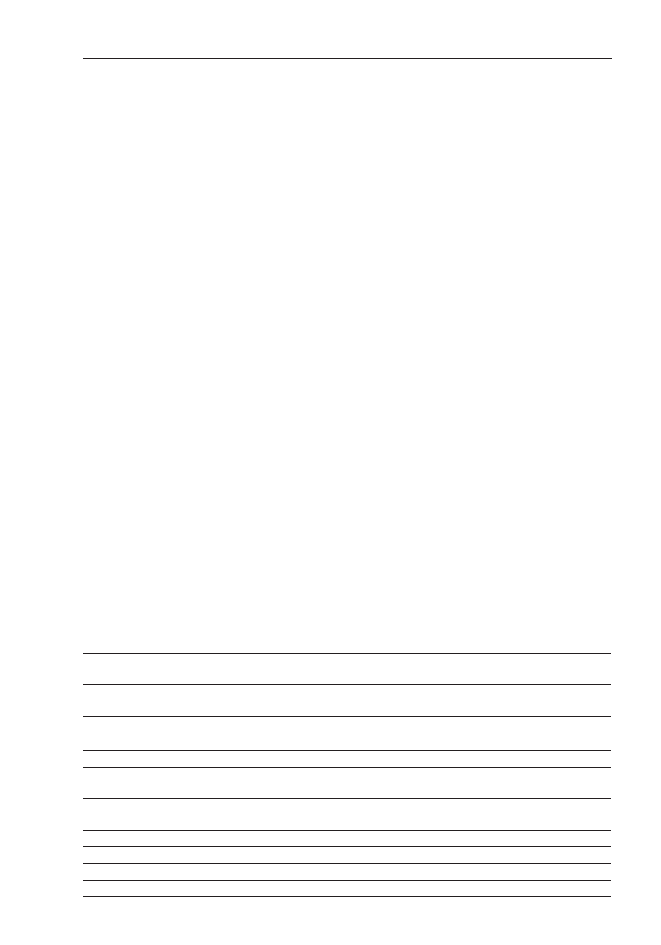

Table 1. Summary of sources and main assumptions of the eco-philosophy of H. Skolimowski and

the ecopsychology of Th. Roszak (elaborated by the author)

Sources and assumptions of Roszak’s ecopsychology

Sources and assumptions of Skolimowski’s eco-

philosophy

S. Freud: the concept of the individual unconscious (human K. R. Popper; T. Kuhn: philosophy of science, evolution

biologicality, instincts)

of paradigms

C. G. Jung: the concept of the collective unconscious as a species Teilhard de Chardin: evolutionary theology A.N.

evolutionary heritage

Whitehead, A. Schweitzer, M. Gandhi

Deep ecology biocentric egalitarianism

Holistic eco-ethics, moderate anthropocentrism

Criticism and rejection of: mechanicism, dualism, materialism, scientism, positivism, reductionism, existentialism,

pessimism.

The meaning of the non-intellectual dimensions of the mind (sensitivity, feelings, values, care, trust, love). Epistemological

equality of science, art, and religion

Socio-cultural revolutions of the 1960s: rejection of consumerism (urban-industrial culture), pacifism, Holism, ecofeminism

Processual, systemic, and evolutionary perspective; New Physics and Cosmology: Anthropic principle, Gaia hypothesis

Ecological Self rooted in Ecological Unconscious

The Participatory Mind

Psychological transformation

Metanoia

Mikołaj Niedek

34

ecology (Fischer 2002) and towards a broad

approach to the psychology of sustainability

(Scott et al. 2021). The practical direction

of the development of ecopsychology – its

operationalization in the form of practi-

cal applications is ecotherapy. Its first defi-

nition was coined by an American pastor,

Howard Clinebell and relates to a reciprocal

form of healing whereby personal healing

is initiated through mindful immersion in

nature, which in turn empowers a person

with an invigorated capacity to conserve

the Earth (Clinebell 1996).

Conclusion

The proposal that integrates the philosoph-

ical-ethical and psychological-existential

approach in the form of a sustainable life-

style pattern and a responsible consump-

tion attitude based on H. Skolimowski’s

eco-ethics is frugalism. The English word

frugality reflects all three values: economy,

moderation, modesty. Recognizing frugal-

ity as the central and general determinant

of the sustainability attitude, its dissemi-

nation and practice in everyday life can be

described exactly as frugalism. Frugality is

understood by Skolimowski as follows: “Fru-

gality is a vehicle of responsibility, a mode

of being that makes responsibility possible

and tangible, in the world in which we rec-

ognize natural constraints and the symbiotic

relationships of a connected system of life.

To understand the right of others to live is

to limit our unnecessary wants. The motto

in one of the Franciscan retreat houses

reads: “Anything we have that is more than

we need is stolen from those who have less

than they need”. (…) Frugality is an opti-

mal model of living vis-à-vis other beings.

A true awareness of frugality and its right

enactment is born out of the conviction that

things of the greatest values are free: friend-

ship, love, inner joy, the freedom to develop

within. (…) On a higher level still, frugality

is grace without waste. (…) frugality is not

a prohibition, not a negative command-

ment (be frugal or be doomed), but a posi-

tive precept: be frugal and shine with health

and grace. (…) Aristotle was already aware

of the beauty of frugality when he wrote

that the rich are not only the ones who own

much but also the ones who need little. (…)

You cannot be truly reverential towards life

unless you are frugal, in this present world

of ours in which the balances are so delicate

and so easy to strain” (Skolimowski 1992,

213-214).

In the context of the above-characterised

balanced pattern of consumption, sustain-

able lifestyle, and ethics of consumption,

frugalism can therefore be defined as a per-

manent ethical disposition of the character

of a human being aimed at satisfying con-

sumption needs in a moderate, economical,

and modest manner, opposing the con-

sumption of excess and wastage, and

aware of wider social and environmental

consequences of the acts of consumption

(Niedek and Krajewski 2021). The condi-

tion for this attitude is therefore recognition

of real and genuine consumer needs, having

ecological awareness and knowledge, and

directing life energy towards more spiritual

than material development (deconsumption

and dematerialisation of consumption). Ta-

ble 2 presents a comparative comparison

of the features of the consumerist (overcon-

sumption) attitude with the frugalistic one.

Frugalism is one of many possible forms

of practicing a sustainable lifestyle, next

to the increasingly popular minimalism,

freeganism, and the Voluntary Simplicity

movement (Niedek and Krajewski

2021). The authors cited earlier also

qualify and characterize as sustainable

lifestyles: Fair Trade, Values and Lifestyles

Segmentation, Lifestyle of health and

sustainability, Wellness, Hygge, Lagom,

Slow living, Smart living, Low-carbon

lifestyles (Lubowiecki-Vikuk et al. 2021,

97). In the ecopsychological perspective,

as well as in the light of the assumptions

of positive psychology, a balanced lifestyle

can perform (psycho)therapeutic and

prophylactic functions both in the area

of human impact on the environment

and the sphere of negative psychological

Ecophilosophical and Ecopsychological Aspects…

35

Table 2. Comparison of the characteristics of consumerist and frugalistic attitudes (elaborated by

the author).

Features of a consumerist consumer attitude

Features of a frugalistic (sustainable) consumer attitude

Satisfying egoistic desires and whims

Satisfying real needs

Ostentatious and snobbish consumption

Modesty

Waste

Recovering

Compulsive consumption

Consumption resulting from real needs

Overconsumption

Sustainable and moderate consumption

Consumption of cheap and perishable goods (low- Consumption of durable and high-quality goods (in particular

quality products, junk food)

of ecological quality)

Predominance of consumption of material goods

Consumption of intangible goods (knowledge, art, beauty, services)

– focussing on personal, spiritual, and interpersonal development

Self-centred consumption, without awareness

of ecological and social effects and costs

Consumption aware of the social and environmental impact

Hedonistic consumption

(aimed at instant gratification “here and now”)

Consumption aware of the pre-consumption stage (origin,

way of producing products) and post-consumption stage (way

of managing post-consumer waste)

effects of the progressing ecological

crisis. Changing the lifestyle to more

sustainable and taking practical actions for

the environment may be an element and

a positive effect of the eco-therapy process,

through its links with the client’s everyday

life (Buzzell 2009).

From a psychological perspective, the is-

sue of sustainable consumption focuses on

identifying the consumer’s real needs, de-

sires and motivations, as well as broad psy-

chological and psycho-social factors of his

consumption choices and consumer behav-

iour. From the ecopsychological perspective,

particular attention is paid to such patholog-

ical phenomena in the behaviour of society

like compulsivity, compensation, narcissism,

and addiction – the features of consumerism.

This is a valuable complement to the charac-

teristics conducted from the philosophical,

axiological, and ethical perspective, which

may be of key importance for increasing

the effectiveness of the practical implemen-

tation of the pattern of sustainable lifestyle

and responsible consumption in society, in-

cluding designing effective activities and

projects in informal and formal education

for sustainable development and in pro-eco-

logical pedagogy.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applica-

ble.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflict

of interest.

References

Bańka, Augustyn. 2002. Społeczna psychologia

środowiskowa. [Social environmental psychology]

Warszawa: Scholar.

Buzzell, Linda. 2009. “Asking different questions:

Therapy for the human animal.” In Ecotherapy:

Healing with nature in mind, edited by Linda

Buzzell, 46-54. New York: Haworth Press.

Clinebell, Howard. 1996. Ecotherapy. Healing

Ourselves, Healing the Earth. New York: Haworth

Press.

Cohen, Maurie J. 2019. “Introduction to the Special

Issue: Innovative Perspectives on Systems

of Sustainable Consumption and Production.”

Sustainability. Science, Practice and Policy 15(1):

104-110.

Devall, Bill, and Georg Sessions. 1985. Deep Ecology.

Living as if nature mattered. Salt Lake City:

Peregrine Smith.

Fisher, Andy. 2002. Radical Ecopsychology. Psychology

in the Service of Life. Albany: Sunny Press.

Fiut, Ignacy S. 2009. “The idea of Sustainable

Development in the Perspective of Henryk

Skolimowski ’s Philosophy.” Problems

of Sustainable Development 2: 25-48.

Mikołaj Niedek

36

Glendinning, Chellis. 1995. “Technology, Trauma,

and the Wild.” In Ecopsychology: Restoring

the Earth/Healing the Mind, edited by Theodore

Roszak, Mary E. Gomes, and Allen D. Kanner,

41-54. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Gomes, Mary E., and Allen D. Kanner. 1995. “The Rape

of the Well-Maidens: Feminist Psychology and

the Environmental Crisis.” In Ecopsychology:

Restoring the Earth/Healing the Mind, edited

by Theodore Roszak, Mary E. Gomes, and Allen

D. Kanner, 111-121. San Francisco: Sierra Club

Books.

Greenway, Robert. 1995. “The Wilderness Effect

and Ecopsychology.” In Ecopsychology: Restoring

the Earth/Healing the Mind, edited by Theodore

Roszak, Mary E. Gomes, and Allen D. Kanner,

122-135. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Jensen, Mikael. 2007. “Defining lifestyle.”

Environmental Sciences 4:(2): 63-73.

Kiełczewski, Dariusz, Felicjan Bylok, Anna

Dąbrowska, Mirosława Janoś-Kresło, and Irena

Ozimek. 2017. “Consumers’ Competences as

a Stimulant of Sustainable Consumption.” Folia

Oeconomica Stetinensia 20(2): 97-114.

Kiełczewski, Dariusz. 2001. Ekologia społeczna.

[Social ecology]. Białystok: Wydawnictwo

Ekonomia i Środowisko.

Kiełczewski, Dariusz. 2004. Konsumpcja

a perspektywy trwałego i zrównoważonego rozwoju.

[Consumption and the prospects of sustainable

development]. Białystok: Wydawnictwo

Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku.

Kiełczewski, Dariusz. 2007. “Struktura pojęcia

konsumpcji zrównoważonej.” [Structure

of the concept of sustainable consumption].

Ekonomia i Środowisko 2(32): 37-50.

Korpikiewicz, Honorata. 2020. Wszechświat Twoim

Domem. Kosmoekologia. [The universe is your

home. Cosmoecology]. Poznań: Wydawnictwo

Nauk Społecznych i Humanistycznych UAM.

Lubowiecki-Vikuk, Adrian, Anna Dąbrowska, and

Aleksandra Machnik. 2021. “Responsible consumer

and lifestyle: Sustainability insights.” Sustainable

Production and Consumption 25: 91-101.

Metzner, Ralph. 1999. Green Psychology. Transforming

our Relationship to the Earth. Rochester: Park

Street Press.

Naess, Arne.1992. Rozmowy. [Conversations].

Bielsko-Biała: Pracownia na Rzecz Wszystkich

Istot.

Neale, Agata. 2015. “Zrównoważona Konsumpcja.

Źródła koncepcji i jej zastosowanie.” [Sustainable

consumption. Sources of concept and

implementation]. Prace Geograficzne 141: 141-158.

Niedek, Mikołaj, and Karol Krajewski. 2021.

“Frugalizm w kontekście ekonomicznych

i aksjologicznych uwarunkowań zrównoważonego

wzorca konsumpcji.” [Frugalism in the context

of economic and axiological determinants

of a sustainable pattern of consumption]. In

Antropologiczne i przyrodnicze aspekty konsumpcji

nadmiaru i umiaru, [Anthropological and

natural aspects of consumption of excess and

moderation], edited by Ryszard F. Sadowski, Agata

Kosieradzka-Federczyk, and Agnieszka Klimska,

40-58. Warszawa: Krajowa Szkoła Administracji

Publicznej.

Niedek, Mikołaj. 2009. Determinanty rozwoju

partnerstwa międzysektorowego na rzecz

równoważenia wzorców konsumpcji i produkcji

[Determinants of the development of cross-sector

partnership for the sustainability of consumption

and production patterns]. Doctoral dissertation.

University of Bialystok, Faculty of Economics and

Management.

Roszak, Theodore, Mary E. Gomes, and Allen

D. Kanner (eds). 1995. Ecopsychology: Restoring

the Earth/Healing the Mind. San Francisco: Sierra

Club Books.

Scott, Brian A., Elise L. Amel, Susan M. Koger,

and Christie M. Manning. 2021. Psychology for

Sustainability. New York: Routledge.

Shepard, Paul. 1998. Nature and Madness. Athens:

University of Georgia Press.

Skolimowski, Henryk. 1974. Ecological Humanism.

Lewes: Gryphon Press.

Skolimowski, Henryk. 1992. Living Philosophy. Eco-

Philosophy as a Tree of Life. New York: Arkana.

Skolimowski, Henryk. 1994. The Participatory Mind.

A new theory of knowledge and of the universe.

London: Arkana Penguin Books.

Skolimowski, Henryk. 1999. Wizje nowego Millenium.

[Visions of the new millennium] Kraków:

Wydawnictwo EJB.

Skubała, Piotr, and Ryszard Kulik. 2021. Dlaczego

brak nam umiaru w eksploatacji zasobów planety?

Ecophilosophical and Ecopsychological Aspects…

37

[Why do we lack moderation in the exploitation

of the planet’s resources?]. In Antropologiczne

i przyrodnicze aspekty konsumpcji nadmiaru

i umiaru, [Anthropological and natural aspects

of consumption of excess and moderation], edited by

Ryszard F. Sadowski, Agata Kosieradzka-Federczyk,

and Agnieszka Klimska, 5-19. Warszawa: Krajowa

Szkoła Administracji Publicznej.

Waloszczyk, Konrad. 1996. Kryzys ekologiczny

w świetle ekofilozofii. [Ecological crisis in

the light of ecophilosophy]. Łódź: Wydawnictwo

Politechniki Łódzkiej.