EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

1

Running Head: EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

Educating for Belonging: Place-based Education for Middle School Students.

Nancy Metzger

Submitted in partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the degree of

Master of Arts from Prescott College

in Education: Place-Based Education]

May 2013

Beverly Santo, Ed.D.

Graduate Mentor

Suzanne Dhruv, M.A.

Second Reader

Lloyd Sharp, M.A.

Third Reader

UMI Number: 1538942

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript

and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

UMI 1538942

Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author.

Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

All rights reserved. This work is protected against

unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code

ProQuest LLC.

789 East Eisenhower Parkway

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

2

Copyright © 2013 by Nancy Metzger.

All rights reserved.

No part of this thesis may be used, reproduced, stored, recorded, or transmitted in any form or

manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder or her agent(s), except

in the case of brief quotations embodied in the papers of students, and in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Requests for such permission should be addressed to:

Nancy Metzger

nancymetzgercarter@gmail.com

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

3

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank my thesis committee: Bev, Suzanne, and Lloyd.

I have the deepest gratitude for my husband, Blair, for supporting this endeavor physically,

intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually. Finally, for my beautiful children Baila and Bodhi,

thank you for your constant lessons in being in the present moment and continuing to inspire me

to make the world a better place.

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………7

Chapter One- Introduction................................................................................................................8-14

Background and Context…………………………………………………………….......8

Statement of Purpose and Research Questions……………………………………...…12

Research Approach……………………………………...…………………………..….12

Assumptions……………………………………………..……………………………..13

The researcher …………………………………………………………………………14

Rationale and Significance ………………………………………………………….....15

Definitions of Key Terminology Used in This Study………………………………..…15

Chapter Two- Review of the Literature...........................................………………………….16-37

Introduction………………………………………………………………………………16

Place Attachment, Sense of Place, Sense of Belonging………………………………….17

Placelessness……………………………………………………………………………...18

Ecopsychology, The Biophilia Hypothesis, and a Sense of Belonging…………………..19

Cosmology and a Sense of Belonging…………………………………………………….21

Place-based Education and a Sense of Belonging………………………………………...24

Access to Nature for Students………………………………………………………27

Place-based Education Benefits Struggling Students………………………………28

Curriculum Design Theory………………………………………………………………..30

A Culture of Construction…………………………………………………………..30

Critiques of the Constructivist Theory……………………………………………...32

A Culture of Self and Spirit…………………………………………………………33

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

5

Understanding by Design: A Method for Curriculum Development……………...35

Concluding Thoughts on the Literature…………………………………………………..36

Chapter Four- Methods........................................................................................……….…..37-46

What is qualitative research? How is quantitative research different?..............................37

Case study as a form of qualitative research……………………………………………...38

Methods: A mixed approach to qualitative research……………………………………..40

Method #1: pre and post surveys…………………………………………………..41

Method #2: participant observations……………………………………………….42

Method #3: large class interview…………………………………………………..44

Limitations and bias in my case study……………………………………………...46

Chapter Five- Results.........................................................................………………………..47-69

Pre- and Post-Survey Results………………………………………………………..….48

Summary and analysis of survey results…………………………………….…..53

Participant observations………………………………………………………………....54

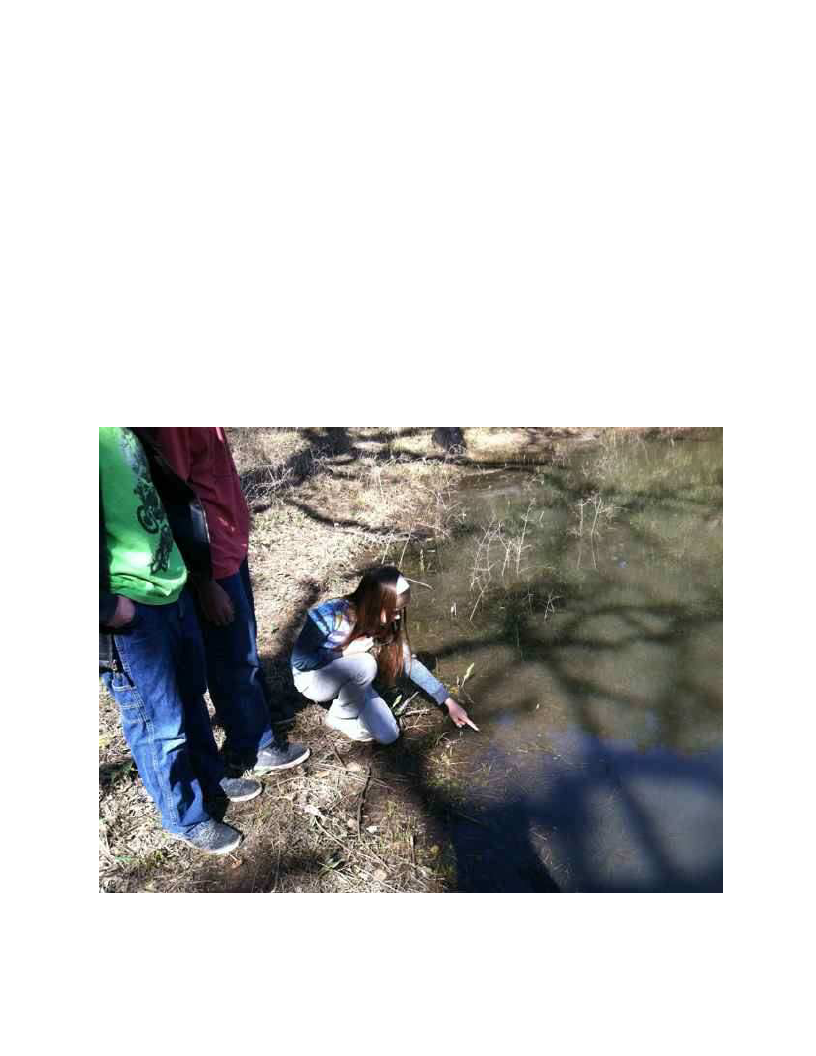

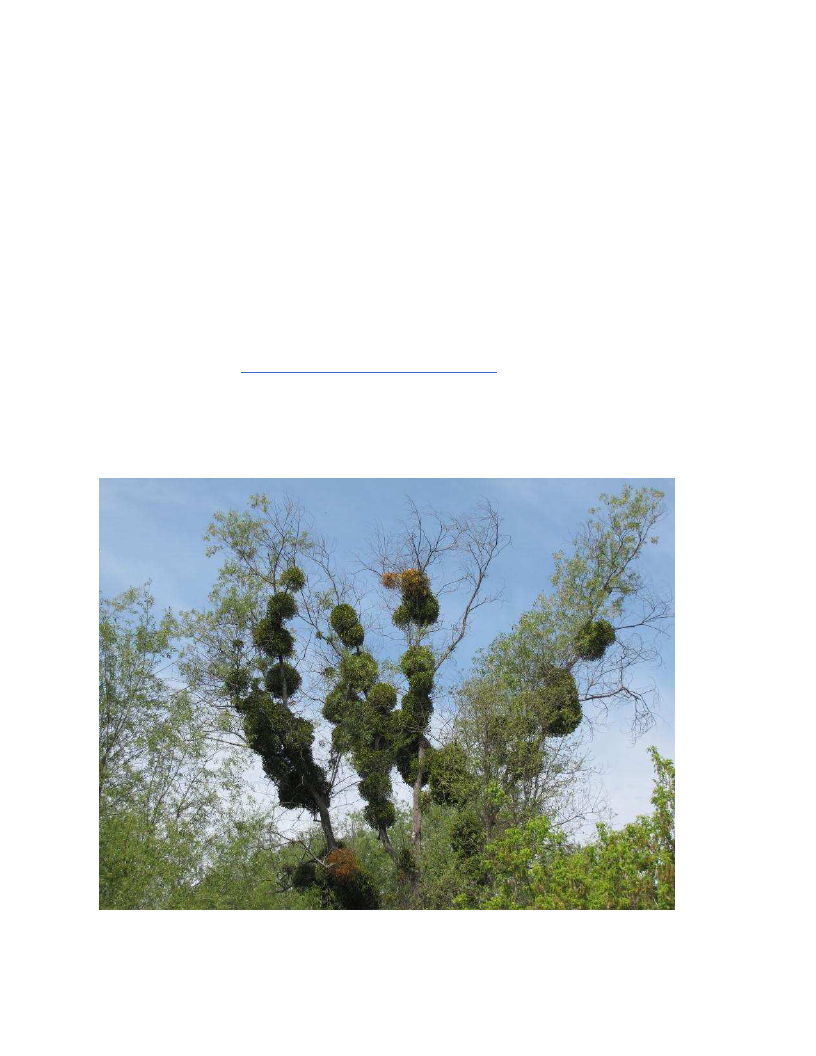

In the field at Pepperwood Preserve…………………………………………….54

In the classroom………………………………………………………………....61

Summary of observations and emerging themes………………………………..63

In-class Interview………………………………………………………………………..65

Summary and analysis of interview results……………………………………..68

Chapter Six- Discussion and Conclusion......................................................………………..70-79

A Framework for Educating for Belonging……………………………………………..72

Challenges for the PBE Educator ……………………………………………………….74

Further Research ………………………………………………………………………..77

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

6

Final Thoughts on the Research Questions………………………………………….78-79

References......................................................................................………………….……….80-86

Appendix A ......................................................................................………………………..…..87

Appendix B………………………………………………………………………………….88-121

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

7

Abstract

This case study examines the effect of a yearlong place-based educational project on a single

class of middle school students aged 11-14 at a public charter school in Santa Rosa, California.

Of particular interest in this case study was the development of the concept of belonging through

the perceptual lens of the middle school student and through the vehicle of place-based

education. This study utilizes qualitative methods including participant observation, interviews

and pre and post surveys. The findings of this study suggest that the outdoor environment was

very engaging for learning, students felt a sense of stewardship toward the land after the project,

and that sense of stewardship characterized a feeling of belonging. In addition, the introduction

of the study of cosmology was a factor in understanding how these young adults came to define

what it means to feel a sense of belonging to their local natural place.

Keywords: place-based education, sense of belonging, sense of place, stewardship, cosmology

or new cosmology, community action, alienation or isolation, ecopsychology, biophilia

hypothesis, placelessness, and constructivist curriculum-culture model.

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

8

Educating for Belonging: A case study of place-based education for middle school

students.

This chapter begins with a background that will provide the context for the study.

Following is the problem statement, purpose statement, and research questions. There is a brief

discussion of the methodology and research approach and my perspective as the researcher.

Then I will discuss some key assumptions made in this study and then conclude this section with

a definition of terms.

Background and Context

There is a large gap between children and nature. Richard Louv has gathered research

highlighting this gap and has coined the term “nature-deficit disorder” (2008). It seems that an

increased amount of media and urbanization have taken the place of the experience children once

used to enjoy in nature (Pyle, 2008). One study found a decrease in outdoor childhood play in

one generation by 73% (Planet Ark, 2011). Louv (2008) writes that poorly designed

subdivisions, overscheduled lives, and an irrational fear of nature strip children from the

opportunity to deeply experience the place in which they live. Now, most 11-14 year olds spend

at least 8 hours and 40 minutes a day with media (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010). The same

study showed that the students in this age group who spent more time with media were more

likely to report feelings of sadness or unhappiness (Rideout, et al., 2010). Increased television

and media exposure in adolescents has been linked to an increased predisposition to depression

(Primack, Swanier, Georgiopoulos, Land & Fine, 2009). About 11 percent of adolescents have a

depressive disorder by age 18 (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2013). The

proportion of 15/16 year olds reporting that they frequently feel anxious or depressed has

doubled in the last 30 years (Hagel, 2012). The new field of ecotherapy has emerged to help

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

9

people reconnect to nature, addressing some the these psychological concerns from an ecological

point of view (See Buzzell & Chalquist, 2009). Similarly, there are eco-therapeutic

developments occurring in education.

Place-based education (PBE) has emerged as an educational pedagogy to address the gap

between children and nature and to ground learning in the local natural and human communities

as a way to educate children as compassionate and engaged citizens. Sobel (2004) was the first

to define PBE completely:

Place-based education is the process of using the local community and environment as a

starting point to teach concepts in language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and

other subjects across the curriculum. Emphasizing hands-on, real-world learning

experiences, this approach to education increases academic achievement, helps students

develop stronger ties to the community, enhances students’ appreciation for the natural

world, and creates a heightened commitment to serving as active, contributing citizens.

Community vitality and environmental quality are improved through the active

engagement of local citizens, community organizations, and environmental resources in

the life of the school. (p. 7)

Place-based education (PBE) offers not only a relevant, engaging formula for educating youth,

but it also aims to foster a deep sense of belonging in natural and human communities. Students

who are taught using a PBE paradigm have the advantage of experience with their local place

and community members.

However, I believe place-based education alone does not address the entirety of the

situation many young people are experiencing today. For instance, the biophilia hypothesis

examines the idea that because humans have evolved with nature for thousands of years, the

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

10

current lack of connection and embodied experience with nature causes an innate desire for

reunification with nature (Wilson and Kellert, 1993). Educating for belonging attempts to

include the human-nature psychic connection discussed by Wilson and Kellert (1993) by seeking

to foster a sense of belonging when educating students in nature. A sense of belonging has often

been used in psychology settings, but not in discussions regarding educational pedagogy.

The concept of a sense of belonging has been used and studied in the field of psychology

and human well-being. Hagerty, Williams, Coyne and Early (1996) defined a sense of

belonging as a psychological experience of valued personal involvement in a system. A sense of

belonging is defined further as “the experience of personal involvement in a system or

environment so that persons feel themselves to be an integral part of that system or environment”

(Hagerty, et al., 1996, p. 172). Haggerty and Williams (1999) concluded that a lack of sense of

belonging is a strong indicator in the development of depression. I expand upon these definitions

to include nature as the “system or environment” where the individual is seeking to become an

integral piece.

Place-based education can be a vehicle for educating for belonging. Because the emphasis

of PBE is on the local natural and human communities, students are deepening their relationships

with their surroundings, and this will reduce a sense of alienation some students may experience.

“Alienation is often the consequence of the absence of experiences that confirm our value to the

people with whom we share our lives. Efforts to induct students into their communities in a

manner that allows them to perform important tasks or to share their perspectives about local

issues can provide exactly this kind of communication” (Smith, 2002, p. 593). I expand upon

Smith’s definition of alienation to include the natural world and suggest that alienation from the

natural world occurs when there is an absence of experiences that orient people within the

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

11

natural patterns of ecology in their local place. One goal of place-based education is to provide

these orienting experiences.

Woodhouse and Knapp (2000) completed an extensive survey of the literature on place-based

education to discover what makes this educational pedagogy distinctive:

• It emerges from the particular attributes of a place. The content is specific to the

geography, ecology, sociology, politics, and other dynamics of that place. This

fundamental characteristic establishes the foundation of the concept.

• It is inherently multidisciplinary.

• It is inherently experiential. In many programs this includes a participatory action or

service learning component; in fact, some advocates insist that action must be a

component if ecological and cultural sustainability are to result.

• It is reflective of an educational philosophy that is broader than "learn to earn."

Economics of place can be an area of study as a curriculum explores local industry and

sustainability; however, all curricula and programs are designed for broader objectives.

• It connects place with self and community. Because of the ecological lens through which

place-based curricula are envisioned, these connections are pervasive. These curricula

include multigenerational and multicultural dimensions as they interface with community

resources (Woodhouse & Knapp, 2000, pp. 2-3).

Before I had heard of the term place-based education, I was employing it as an educational

philosophy in my classroom. An example is from a group of seventh graders that were studying

classification of living things. We took a field trip to Duxberry Reef, a protected area in the

Point Reyes National Seashore. I had arranged for marine biologists from the national park to

meet us there and to include us in their project. My students received training on how to set up

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

12

transects and how to identify and record the number of sand crabs. Their findings were compiled

into a report that was presented the Marine Institute. Students then researched specific creatures

that have relationships to sand crabs and created interpretive materials that they then donated to

the Marine Institute’s educational program. Students reported that they felt a sense of

importance by participating in what they called “real” research creating a “real” product that

would be used by professional naturalists to teach other children. It was during this project that I

started to see how important a sense of belonging was to my students.

Another example was from a group of my students that wanted to “green” their school

campus. Students chose categories to address including waste, grounds, food, and energy. Each

student group then researched how to create change in each area and creatively presented his or

her idea to members of the school community including the principal, school board members,

and a member from the Marin County Board of Supervisors. I videotaped the student

presentations, and students followed up on their proposed changes throughout the year. Fueled

in part from this project, the school initiated a major overhaul of operational systems with a new

focus on sustainability. Students were impressed and heartened that their passionate voice could

drastically impact the school community.

Little did I know that these projects and their similar themes (authentic, real-world and

place-based) exemplified the emerging field of place-based education. My graduate study at

Prescott College in place-based education grounded my experiences as an educator with

scholarly study and research. After receiving a solid framework of research design instruction I

felt I was ready to undertake this case study research project with a group of my own students.

Statement of Purpose and Research Questions

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

13

This case study examines the effect of a place-based educational project on middle

school students and seeks to create an understanding of how students come to experience a sense

of belonging to the natural world. The sample population is a group of 16 students aged 11-14

from a multiage, middle school classroom at a public charter school in Santa Rosa, California.

Learning occurred in the field at a local nature preserve as well as in the classroom.

Questions posed in this research are:

o How do these students define a sense of place and a sense of belonging?

o Does understanding local flora affect students’ sense of belonging?

o Can learning about place through experience in nature, research into ethno-

botanical usages of local plants, basic botany, service learning and photography

incite a sense of belonging in my students?

Research Approach

After approval from my university’s institutional review board I studied 16 middle school

students through a mixed method approach. In order to answer these questions, I incorporated

qualitative research methods including pre- and post-surveys, participant observations, and large

class interviews. I used the case study as a methodology for contextualizing my data. The limits

of this study lie within the methodology and sample size. A case study is a stand-alone example

that does not necessarily represent a general population of middle school students. In addition,

my sample size is very small—only 16 students. Also, the case study is descriptive in nature, not

explanatory, so it is impossible to make casual conclusions from case study results.

Assumptions

This study assumes that urbanization and the extinction of nature experience has a

negative effect on young adolescent students. Research indicates that the absence of nature

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

14

experiences can affect a student’s sense of place and belonging. Some of the more obvious

assumptions in this text come from my own personal worldview, which is primarily ecological. I

believe a connection to nature is vitally important for all ages. That being said, this study

assumes the absence of nature experience is detrimental to human well-being, if not also,

ecological well-being.

The researcher

I played many roles in this project: researcher, teacher, participant and project designer.

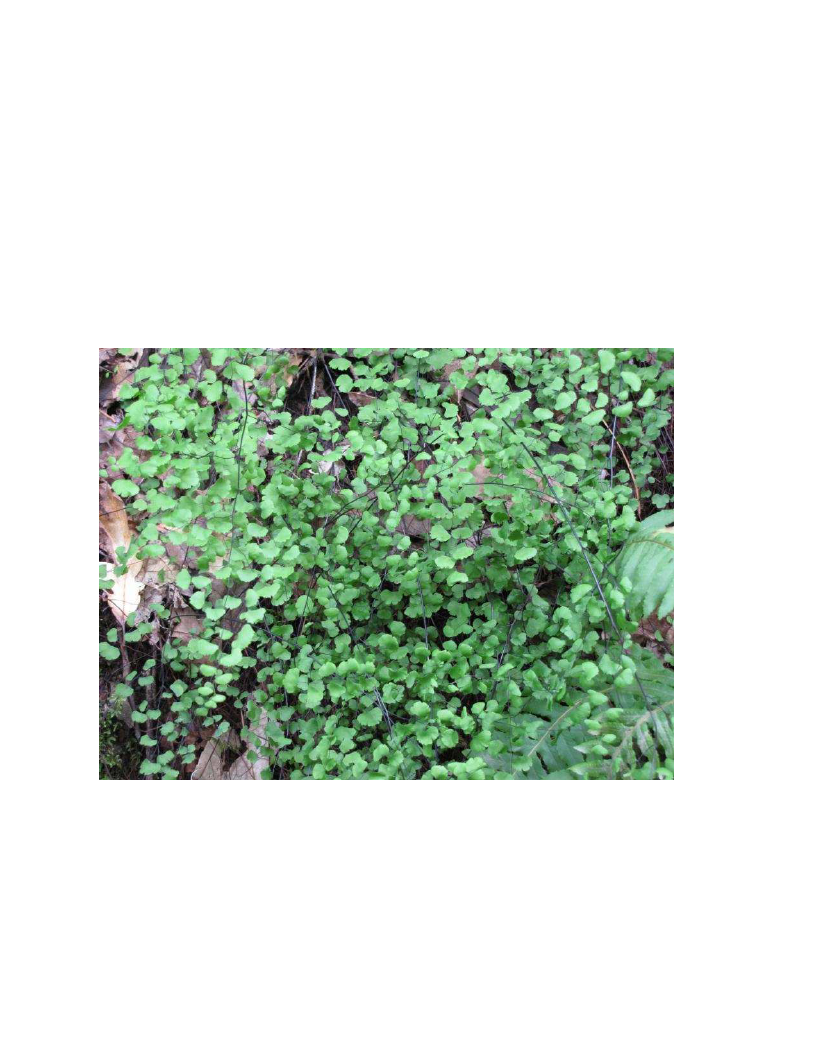

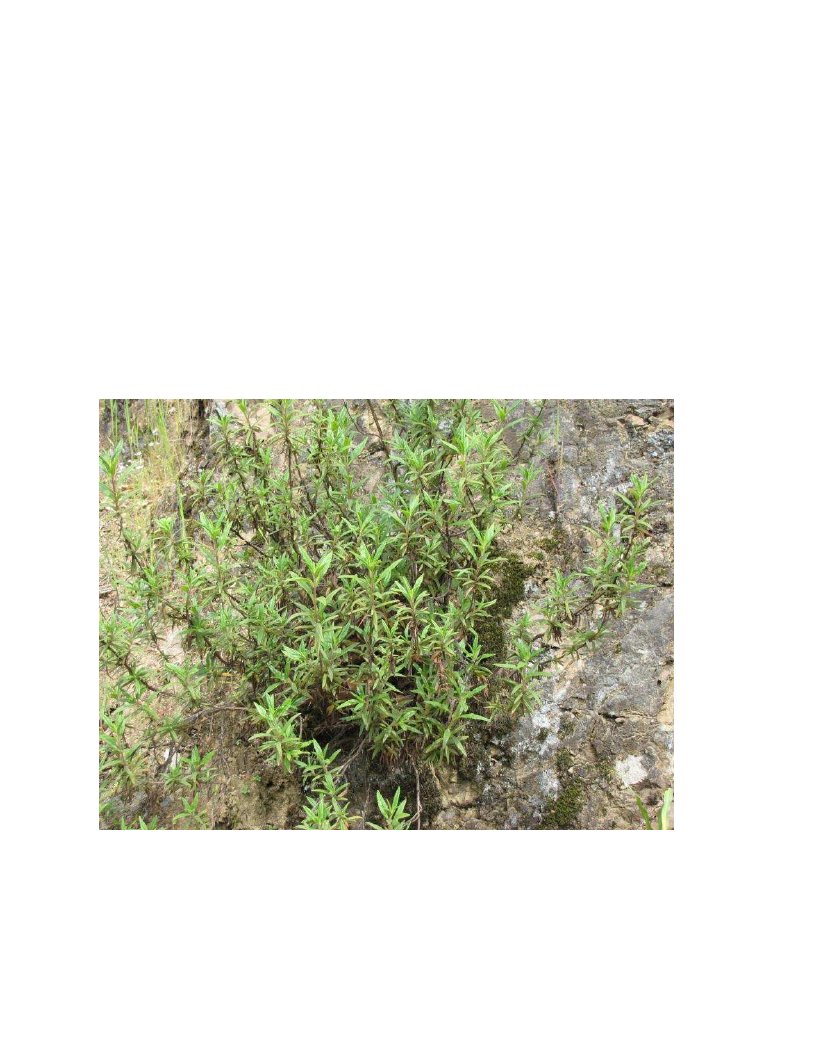

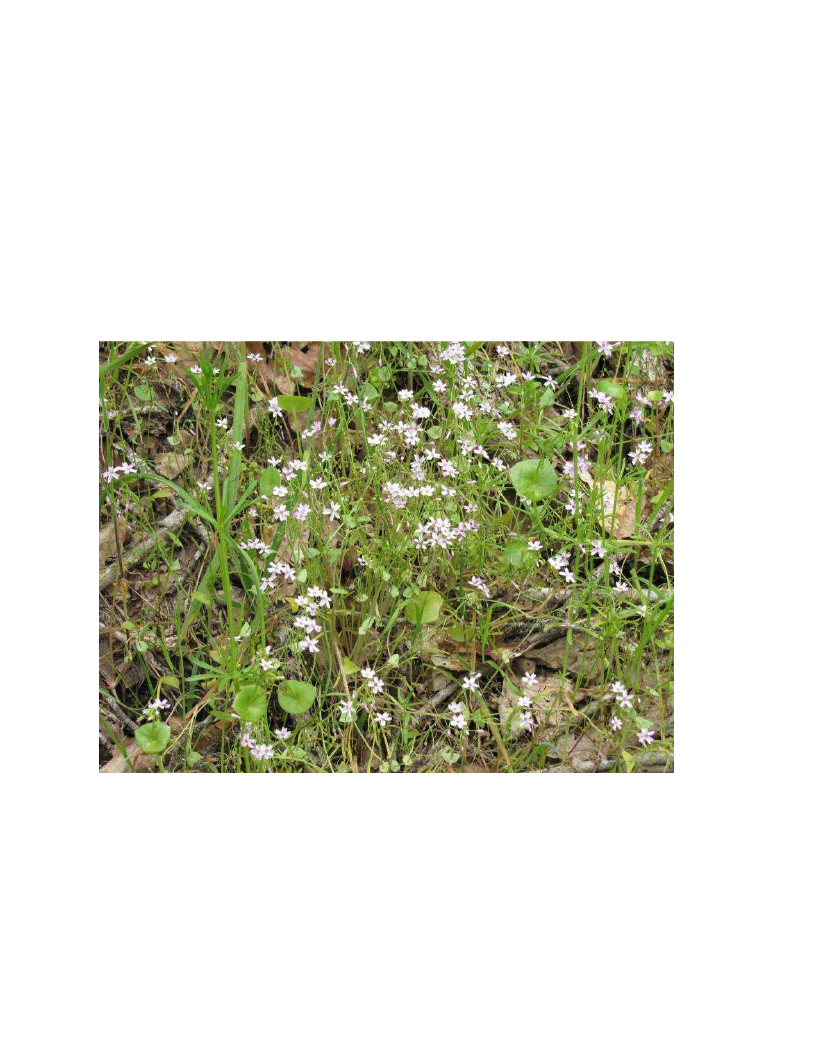

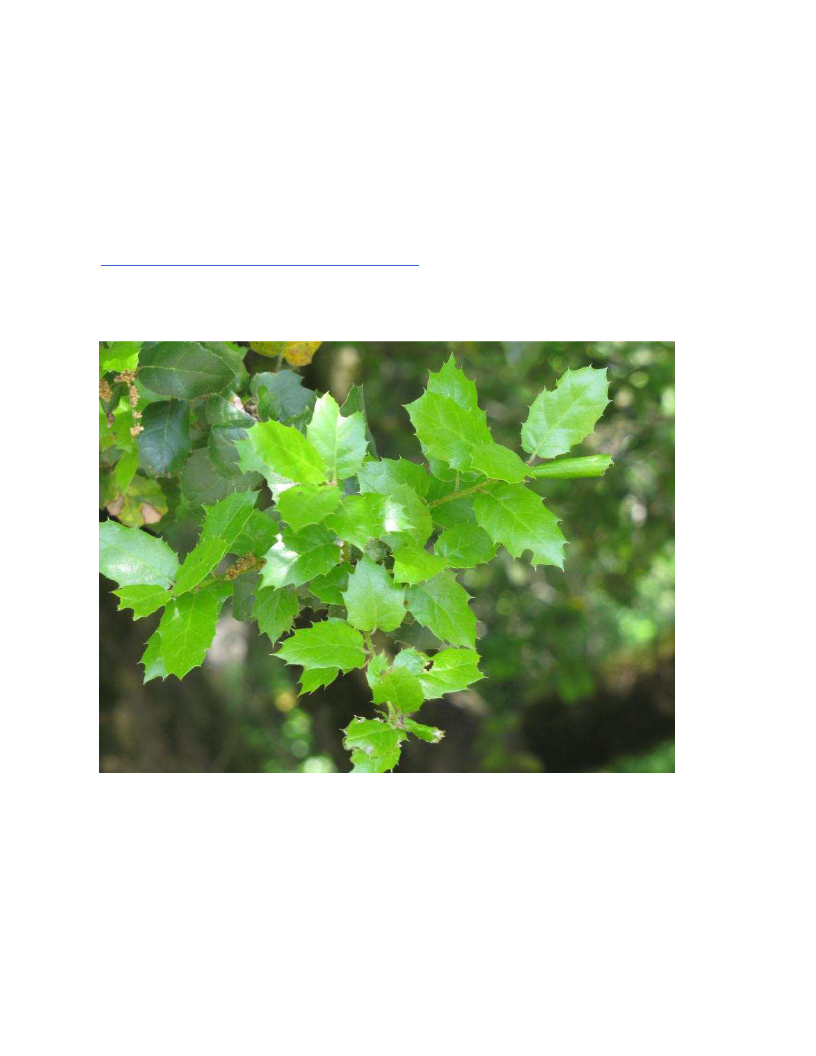

I created the experiential curriculum for students in the form of a student-generated field guide to

a local natural preserve. The goal of the curriculum was to steep the students in knowledge of

the preserve through botany and ethnobotanical knowledge. In addition, I created a higher

purpose for the final product of the students’ project. The final project -- a student-generated

field guide to the plants of Pepperwood Preserve -- was donated to the preserve’s library so that

other student groups could utilize it while visiting. This is a common practice amongst place-

based educational projects that are relevant and purposeful for students.

In order to understand the conceptual framework for the development of a sense of

belonging through place, I drew from my personal perspective as a place-based educator, the

biophilia hypothesis, the ecopsychology movement, and the New Cosmology teachings of

Thomas Berry and Brian Swimme to articulate a sense of belonging to the natural world. Sense

of belonging is the term that I chose as the focus in this investigation because I wanted to explore

how interactions with a place can incite the feeling or emotion of belonging. A sense of

belonging is defined as “the experience of personal involvement in a system or environment so

that persons feel themselves to be an integral part of that system or environment” (Hagerty, et

al., 1996, p. 172). I expand upon these definitions to include nature as the “system or

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

15

environment” where the individual is seeking to become an integral piece. A sense of belonging

can be experienced when an individual experiences feeling interconnected to nature, where she

or he is an integral piece of the natural world, and is personally involved in that world.

Rationale and Significance

This study contributes to the field of place-based education. There is a growing body of

research that shows when students engage with their local natural community, and develop a

sense of place, they feel more connected to their community. This connection can manifest in

many positive ways for students, including an enhanced desire for preservation of natural spaces,

more time spent outdoors exercising, and choosing careers focused on service in the future. This

study sought to examine the concept of a sense of belonging as the result of a place-based

educational project. This study specifically adds to numerous other case studies examining the

effect of place-based programs. In addition, this research informs the educator who looks to

deepen student connection to natural areas while at the same time engaging in meaningful

curriculum. This study solely focuses on middle school students, but the project and resulting

theoretical framework can be examined to fit other ages.

Definitions of Key Terminology Used in This Study

Cosmology is the study of the universe as a whole and the story that results from the study of the

universe. Cosmological questions include: Why am I here? What is my purpose? How did the

universe form? What is my creation story? Cosmology, in its very nature, is a science of

belonging. By using science, myth, mathematics, religion, philosophy, art and history the field

of cosmology seeks to reconnect humans to every thing around them. Cosmology addresses the

entire universe as an integral web of the human experience.

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

16

Place-based education (PBE) is the process of using the local community and environment as a

starting point to teach concepts in language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and other

subjects across the curriculum. Emphasizing hands-on, real-world learning experiences, this

approach to education increases academic achievement, helps students develop stronger ties to

the community, enhances students’ appreciation for the natural world, and creates a heightened

commitment to serving as active, contributing citizens. Community vitality and environmental

quality are improved through the active engagement of local citizens, community organizations,

and environmental resources in the life of the school (Sobel, 2004, p. 7).

Sense of belonging is defined as “the experience of personal involvement in a system or

environment so that persons feel themselves to be an integral part of that system or environment”

(Hagerty, et al., 1996, p. 172). I expand upon this definition to include nature as the “system or

environment” where the individual is seeking to become an integral piece.

Sense of place: “A sense of place is not intrinsic to the physical setting itself, but resides in

human interpretations of the setting which are constructed through experience with it”

(Steadman, 2003, p. 672). This definition relies less on the physical land itself, and brings

awareness to the human interpretation of the landscape as prime importance for a sense of place.

Stewardship is the careful and responsible management of something entrusted to one's care.

“stewardship of natural resources” (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stewardship)

Review of the Literature

This literature review examines the relevant theories and theorists that informed this

investigation. My research was unique because I created a place-based educational curriculum

project and then used the project to examine the students’ knowledge, beliefs and attitudes for a

sense of belonging to the natural world. I used the term “sense of belonging” and “educating for

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

17

belonging” in this investigation to include place-based education, cosmology, sense of place

education, stewardship and connectedness to nature. Because I wanted to use the concept of a

sense of belonging as a new holistic goal of education that was my own conceptual creation, I

needed to include theorists who informed the creation of the concept of educating for belonging.

The premise of educating for belonging is examined, including ecopsychology and the biophilia

hypothesis. The concepts of sense of place, place-attachment and placelessness are explored and

differentiated. Cosmology is explored in the context for educating for belonging. Place-based

education is studied as a method for educating for belonging. In addition, because of the

curriculum design piece of my research, the theory of constructivist curriculum design is

discussed and critiqued. Finally, a method for curriculum development, Understanding by

Design, is discussed as a method employing curriculum design tactics to inform this project.

Place attachment, sense of place, and a sense of belonging

The terms sense of place, place attachment, and place satisfaction have been used by

scholars in the environmental field to demonstrate one of the goals of place-based education: a

deep connection with nature. These terms are similar in meaning, but can sometimes be used

without clear differentiation. The term place attachment “is a positive emotional bond that

develops between people and their environment” (Steadman, 2003, p. 672). Ryden (1983)

articulates the concept of sense of place as “grounded in those aspects of the environment which

we appreciate through the senses and through movement: color, texture, slope, quality of light,

the feel of wind, the sounds and scents carried by that wind” (p. 38). This physical, objective

account of sense of place differs from other authors that have expressed that a sense of place

includes interpretation. “A sense of place is not intrinsic to the physical setting itself, but resides

in human interpretations of the setting which are constructed through experience with it”

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

18

(Steadman, 2003, p. 672). This definition relies less on the physical land itself, and brings

awareness to the human interpretation of the landscape as prime importance for a sense of place.

Developing a sense of place for youth appears to be linked to environmental stewardship

and positive social action later in adulthood (Sobel, 2004; Chawla, 1998; Chawla, 2006). One

study suggests that children who have frequent experiences in wild nature may become more

environmentally responsible adults (Wells & Lekies, 2006).

Sense of belonging is defined as “the experience of personal involvement in a system or

environment so that persons feel themselves to be an integral part of that system or environment”

(Hagerty, et al., 1996, pg. 172). I expand upon this definition to include nature as the “system or

environment” where the individual is seeking to become an integral piece. Sense of belonging is

the term that I use as the focus in this investigation because I want to explore how interactions

with a place and its inhabitants can incite the feeling or emotion of belonging. The antithesis of

belonging is alienation that “is often the consequence of the absence of experiences that confirm

our value to the people with whom we share our lives” (Smith, 2002, p. 593). I expand upon

Smith’s definition of alienation to include the natural world; alienation from the natural world

occurs when there is an absence of experiences that orient people within the natural patterns of

ecology in their local places.

Placelessness

An important phenomenon to mention in the context of this discussion is the emerging

idea of placelessness. Relph, in his 1973 book Place and Placelessness describes what he saw

then as “the casual eradication of distinctive places and the making of standardized landscapes

that results from an insensitivity to the significance of place” (Relph 1976, Preface). Relph

(1973) wrote distinctively for his time about how the authentic elements of a place were being

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

19

eroded away for efficiency over culture. Another author, building upon Relph’s conceptual

framework, describes that “the roots of placelessness lie deep in globalization, which generates

standardized landscapes and ‘inauthenticity’” (Arefi, 1999, p. 184). This concept has grown out

of emergent suburban landscapes or “edge cities” as they have been called. In these edge cities

history, geography, and cultural elements are packaged as consumable commodities (Arefi,

1999). National chain stores, mini-malls, highways, manufactured homes, parking lots, and car

dealerships— all these things characterize edge cities in places all over the US. Often these

cities are indistinguishable from similar edge cities in other parts of the country, because of the

presence of the same businesses, advertisements, logos, and architecture. These contrived

landscapes often offer so-called invented traditions, like amusement parks and theme parks.

Many of these places contain contrived cities like Universal Studios in an attempt to distinguish

themselves from other suburban areas (Arefi, 1999).

These edge cities characterize the concept of placelessness. Because the physical, natural

environment is not considered or incorporated, the result is a manufactured and prepackaged

sense of place. This leaves an interesting dynamic for the children growing up in these

environments. How do people come to experience a sense of belonging in a places where

advertising and corporate business characterize the landscape? In these places, people seek a

consumer lifestyle that may lead to a feeling of discontent.

Ecopsychology, the biophilia hypothesis and a sense of belonging

Adolescents in the United States are experiencing an unprecedented amount of isolation

and alienation manifesting in the form of depression and other emotional illnesses (Hagel, 2012),

and the earth herself is struggling through a time where a peak point in environmental

degradation is occurring. Sarah Conn, a Cambridge clinical psychologist, said, “the world is

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

20

sick; it needs healing; it is speaking through us; and it speaks the loudest through the most

sensitive of us” (as cited in Roszak, 1995, p. 13). This understanding -- that the earth can speak

through us -- characterizes the field of ecopsychology. Ecopsychology is defined as the

convergence of psychology and ecology, and the exploration the emotional bond between human

and the planet. (Roszak,1995). Theodore Roszak (1995) maintains “the self-regulating biosphere

‘speaks’ through the human unconscious, making its voice heard even within the framework of

modern urban human culture”(p. 14). So, according to ecopsychologists, it is possible that the

suffering of the natural world may cause the alienation and depression that humans are

experiencing because we cannot separate ourselves from it. Because the natural world is made

of up the same things as humans (molecules, elements, atoms) it is possible that they are

inextricably psychically linked.

Pretty (2002) estimates that for 350,000 generations humans lived close to the land as

hunter–gatherers, and that a sense of belonging, place, and feeling embedded within the broader

natural world characterizes these cultures. The biophilia hypothesis depends on genetically

based tendencies to appreciate and identify with the natural world (Wilson and Kellert, 1993). E.

O. Wilson maintains that humans remain linked physically, mentally and emotionally to having

contact with the natural world, and this contact is necessary for effective maturation and well

being (Wilson & Kellert, 1993). Biophilia addresses the need for contact with the natural

environment on a genetic level and could explain how emotional well being of some individuals

is disturbed now that human culture spends an increasing amount of time indoors and otherwise

isolated from natural places. One consequence of industrialization and urbanization is that

Americans characteristically spend increasing amounts of time indoors in both leisure and work

life. In fact, Evans and McCoy (1998) estimate that the average American spends 90% of life

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

21

within buildings. The biophilia hypothesis encourages me to believe that a sense of belonging

cannot be achieved unless a relationship to the natural world is cultivated. Kellert (1998) shows

that long, deep experiences in nature for adolescents through programs like Outward Bound

results in so-called life-changing feelings of self-confidence, independence, and an overall sense

of connectedness to nature.

The biophilia hypothesis encourages me to believe that a sense of belonging cannot be

achieved unless a relationship to the natural world is cultivated. The biophilia hypothesis and the

field of ecopsychology offer the idea that because some people have separated themselves from

the natural world through an industrialized and consumer society there is a part of the national

psyche that craves a reunification with it. Some suggest (Buzzell & Chalquist, 2009; Roszak,

1995) when that part of the psyche feels fulfilled, through experience with the natural world and

a holistic understanding of place, feelings of isolation and alienation can be overcome. In fact,

an entire new field of therapy called Ecotherapy is emerging in response to individuals who

experience deep senses of isolation and alienation. Robinson (2009) writes: “Most people in our

culture have been treated like objects their entire life…. Because people have come to experience

themselves as objects they in turn objectify other people and commodify the world. They feel

alienated, isolated and empty believing their lives hold no meaning” (pg. 25). A sense of

belonging emerges through the understanding of place within the natural cycles of the world.

E.O. Wilson and his biophilia hypothesis, and ecopsychologist Theodore Rozak address the

intrinsic need for educating for belonging. They raise the possibility that humans possess a

capacity of essential and emotional connection to other living organisms (Wilson & Kellert,

1993).

Cosmology and a sense of belonging

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

22

The field of cosmology surfaced during my research in relationship to the experience of

belonging and place. According to one of the most prominent scholars in the field of cosmology

today, Brian Swimme (1996), cosmology is “a wisdom tradition drawing upon not just science

but religion and art and philosophy. Its principal aim is not the gathering of facts and theories,

but the transformation of the human” (p. 31). Another cosmology scholar, Drew Dellinger,

explains: “When I tell people what ‘cosmology’ means, I say, ‘first it means the study of the

universe as a whole, and secondly, it means the story that a people tell themselves about how the

world came to be and how they fit into it’” (Dellinger, 1997, p. 92).

Thomas Berry, who developed the concept of the New Cosmology, remarks that

cosmology is important to people “because it’s the story of their own structure and their own

being. To explain themselves, people need to explain the universe, because everything that’s

happened has conspired to produce in sequence the solar system, to produce the planet earth,

produce life, produce consciousness. So we are integral to the process. To understand ourselves

we need to understand the process” (Berry, as cited by Dellinger, 1997, p. 26). He goes further

to explain, “When we look at trees, stars, the ocean… we are integral to this process, not in some

extrinsic relationship, but with the inner process of emergence. In seeing these realities we are

seeing things that are intimately related to ourselves, and that’s why we rejoice. We’re ecstatic”

(Berry, in Dellinger, 1997, p. 26). Cosmology, in its very nature, is a science of belonging. By

using science, myth, mathematics, religion, philosophy, art and history the field of cosmology

seeks to reconnect humans to every thing around them. Cosmology addresses the entire universe

as an integral web of the human experience.

But cosmology as a practice is not new. In fact, all classical civilizations had means to

pass down the world-view of their people onto the youth of their culture. Our culture continues

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

23

this tradition, utilizing advertisements to teach consumerism to our youngest members. Swimme

remarks about the effect of this cosmological paradigm on our culture:

Consumerism is based on the assumption that the universe is a collection of dead

objects. It is for this reason that depression is a regular feature in every consumer

society. When humans find themselves surrounded by nothing but objects, the

response is always one of loneliness, and here at the end of the second millennium

we are swamped by a vast loneliness that has soaked into every stratum of our

society. It is a sad though arguable fact that in the history of civilization there has

never been so much loneliness in any society anywhere compared to that in

contemporary industrial consumer society. (Swimme, 1996, p. 34)

Here, Swimme explains how the idea of belonging is manifested in the U.S. culture. A

possible result of the cosmological teachings provided to youth through advertising is loneliness

and depression. Young people spend more and more hours inside watching television and

surfing the Internet—two major sources of advertising. According to a 2009 study, adolescents

who watched television for a substantial period daily were more likely to develop depression

later in life (Bakalar, 2009). The message from our culture through advertisements is clear:

One’s purpose in life is to work, earn money, and buy things. Swimme discusses this message

further:

I am particularly sensitive to the way in which the advertising world is constantly feeding

our children meaning, so the average American child doesn’t have to ask the

cosmological questions. They can, of course, but if they don’t then they assume the

meaning given them by 10,000 ads a year. The ads all say the same thing: The meaning

of life is to get a job, so that you can have the money to buy stuff. And it’s great stuff!

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

24

The way it’s advertised is like, “wow, this is so great!” So all young kids want various

things and know they have to get some kind of job to get them. (Swimme, 1996, p. 93)

It is understandable how this consumer paradigm can lead to isolation, alienation and

depression. It may seem that the predominant way a consumer society is teaching children about

belonging is through buying. The concept of place in relationship to belonging is non-existent.

Swimme (1996) postulates: “Our natural genetic inheritance presents us with the possibility of

forming deeply bonded relationships throughout all ten million species of life as well as

throughout the nonliving components of the universe” (p. 34). Similar to the biophilia

hypothesis, Swimme is saying that humans are biologically created in order to develop a

relationship with the natural world and the universe itself.

The New Cosmology of Brian Swimme and Thomas Berry offer the invitation to

reinvigorate how youth come to create their cosmological paradigm. When cosmology is alive

in a culture, it “evokes in the human a deep zest for life, a zest that is satisfying and revivifying,

for it provides the psychic energy necessary to begin each day with joy. In the process of

cosmological initiation as practiced by humans for three hundred thousand years, the pain of

loneliness and isolation is replaced by the joy of bonded relationship” (Swimme, 1996, p. 36).

A holistic understanding of the universe through cosmology eliminates the sense of alienation

and isolation that youth are experiencing by providing a context for the exploration of the natural

world. This exploration puts humans in an integral role in the unfolding of the universe, and

fosters the understanding that each life plays a role in the web of relationships that comprise the

physical world. Humans fit right in. People belong.

Place-based education and a sense of belonging

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

25

Place-based education (PBE) seeks to ground learning in the local natural and human

communities as a way to educate children as compassionate and effective citizens. PBE offers

not only a relevant, engaging formula for educating youth; it aims to foster a deep sense of

belonging in natural and human communities. Students who are taught using a PBE paradigm

have the advantage of experience with their local place and community members. Supporters of

the concept of place-based education believe that “an education that orients children and adults

to the values and opportunities that inhere in the places where they live could provide the

dispositions, understandings, and skills required to restore and democratize humanity’s adaptive

capabilities” (Gruenewald & Smith, 2008, p. xx). The aim of this educational pedagogy is to

guide students to recognize the assets found in the human and natural environments closest to

them, and to accentuate restraint in the use of natural resources and support for social practices

informed by mutuality (Grunewald & Smith, 2008).

Some research shows that students are naturally motivated learners when they are

engaged in real-world problem solving that sparks their individual interest by exploring issues

that impact their lives (Pranis & Duffin, 2009). By providing an opportunity for students to

explore what they are passionate about, educators are helping to create motivated learners in

classrooms. Studies show that when students are faced with real life problems in school that

directly are affecting their community, they tend to build stronger connections to those places

(Cargo, Grams, Ottoson, Ward & Green, 2003; Duffin, Powers, Tremblay & PEER Associates,

2004 as cited in Pranis & Duffin, 2009). I believe that making learning projects relevant by

addressing a current or local phenomenon creates a deep sense of learning that fosters self-

confidence, expands self-concept, and incites a sense of belonging in students. These traits

cannot be measured nor induced by any standardized test or multiple-choice assessment. It is a

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

26

specific process of learning that carries with it a sense of accomplishment and importance. By

addressing a current question in their local ecosystem, students themselves feel a sense of

belonging and begin to believe that they can make a difference in their world, now and in the

future.

Place-based education can be the framework for educating for belonging. Because the

emphasis of PBE is on the local natural and human communities, students are deepening their

relationships with their surroundings, which can incite feelings of belonging and possibly reduce

the experience of alienation. “Alienation is often the consequence of the absence of experiences

that confirm our value to the people with whom we share our lives. Efforts to induct students into

their communities in a manner that allows them to perform important tasks or to share their

perspectives about local issues can provide exactly this kind of communication” (Smith, 2002, p.

593). PBE provides an appropriate avenue for students to be inducted into their communities as

integral, respected members.

Educating for belonging can thrive utilizing the ideology of place-based education, but I

believe incorporating a holistic view of the universe through cosmology is paramount. Not only

will students come to understand their local bioregion and its functioning parts, but also the

student will be able to understand his or her place within the network of systems that is her or his

bioregion. From the earliest years of education students can learn about how relationships, both

human and not, define their role in the universe. Charlene Spretnak wrote about educating in this

manner:

The littlest children would start with the most basic relationships; between the body and

the sun, and the body and water; and then they would look at the relationships in their

backyard, and with their family, and in the school yard and school neighborhood; and

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

27

next their bioregion and nation and all. The same emphasis on relationships should be

applied to the various disciplines. What is mathematics? It’s teaching us a way to

understand relationships. What is literature? It’s relationship among words. Every

subject could be taught that way so the student would gain an increasingly nuanced

understanding of relationship. That would create in a child a very different sense of how

to go out into the world, then, after the years of school are finished. (as cited in Dellinger,

1997, p. 78)

Using cosmology as a teaching tool through an emphasis on relationships and re-invigorating the

study of local place in education can help students to develop a sense of belonging.

Access to nature for students

Author and biologist Robert Michael Pyle (2008) has elegantly expressed the phenomenon

of “the extinction of experience” to be at the root cause of many children’s sense of alienation

from the places in which they live (p. 157). Richard Louv, in Last Child in the Woods (2008),

has expertly gathered shocking research into the loss of childhood play in nature and coined the

result “nature deficit disorder” (p. 10). Both authors call to educators and designers to examine

how children have access to nature areas for instruction in natural phenomenon and for play

space at their schools and in their communities. This outdoor space is the foundation for place-

based education. “Place-based education, no matter how topographically or culturally informed,

cannot fully or even substantially succeed without reinstating the pursuit of natural history as an

everyday act” (Pyle, 2008, p. 156). Natural history (the flora, fauna, geology, meteorology, and

human history of an area) is best taught in nature, and the opportunities that schools provide

every day are paramount for the success of place-based educational programs. Some schools and

communities have responded to this need by building outdoor classrooms, school gardens,

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

28

reclaiming adjacent natural lots near schools, and providing access to local forests, farms,

wetlands, rivers, oceans and other natural playgrounds.

Place-based education benefits struggling students

Place-based education has been shown in research to boost test scores, increase positive

feelings about school and incite a sense of stewardship in students (Louv, 2008; Smith, 2002;

Pranis & Duffin, 2009; Sobel, 2004; Chawla, 1998; Chawla, 2006). But what about students

who struggle with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD)? ADD and ADHD currently impacts 9% of

children ages 4-17 years old (NICHCY, 2010). While the actual cause of the disorder(s) is

unknown, it has seen a dramatic rise in children in the last decade. As a result, scientists have

looked to study different environments and curricular strategies that can best support students

with ADD/ADHD. Some of the most intriguing studies involve place-based education and

nature based learning as a method to support students with this disorder.

The aspect of this pedagogy that gets students outside, engaged in a natural setting, has

been studied for benefits for ADD/AHHD students. A study in The Journal of Attention

Disorders in 2008 showed that a 20-minute walk in nature is associated with better concentration

in children with ADHD (Taylor & Kuo, 2008). Even more important, these results were found

across various community sizes, household income levels, and geographic areas, showing how

the benefit of experiences and exposure to nature hold despite the wide variation of green

settings in diverse urban spaces (Taylor & Kuo, 2008). In analyzing the data, Taylor & Kuo

(2008) found the following: that children concentrated better after walking in a park setting as

compared to either a downtown or residential setting; that the effect of walking in a park on

concentration helped close the gap between children with ADHD and those without ADHD with

regard to the concentration measure used; and that the effect was similar to that of two common

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

29

types of ADHD medication (Taylor & Kuo, 2008). This study received media attention

(Patterson, 2004) and educators began to take notice of this growing phenomenon of the impact

of natural, outdoor green spaces on ADD/ADHD students.

A 2001 study found that a children had greater so-called attentional functioning when they

were playing outside vs. indoors. This study found that the greener the setting, the fewer

symptoms of ADD surfaced (as cited in Patterson, 2004). One study of attentional skills focused

on children with attention-deficit disorder. Parents of the 7- to 12-year-olds in that study reported

less severe attention difficulties when their children had spent playtime in a natural area rather

than other settings (Pastor & Reuben, 2008). The greener a child's play area, the less severe the

attention problems, the data showed (Patterson, 2004, p. 12).

In an evaluative study of four place-based education programs, Powers (2004) found that

special education aides noted the content and format of place-based education was well-suited to

their students:

Throughout the evaluation process, the respondents noted that special education

students performed better during the place-based learning activities. Preliminary (and

unsolicited) reports of benefits included students working more independently than they

did in seated or lecture-based formats, engaging more enthusiastically with adult

community mentors, and gaining the respect of their "nonspecial education" peers as they

thrived in the general school setting. (Powers, 2004, p. 26)

Many place-based programs offer curricula that can benefit all students and provide an inclusive

environment for all types and abilities of learners. In order to create curricula that can benefit all

students using place-based education, educators must consider some elements of curriculum

design.

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

30

Curriculum design theory

Curriculum theory today is a complex, polarized and often heated and emotional subject

for educators. According to Schnuit (2006), approaching the curriculum as classroom “culture”

teachers can find “ways to satisfy state curricular objectives as minimal accomplishment, with

student-created understandings far surpassing that level as the norm” (para 4). Here I discuss

two different ways teachers can use the curriculum-as-culture model: as a culture of self and

spirit and as a culture of construction. I also explore a critique of constructivist curriculum-

culture model, provided by place-based educational advocate, C. A. Bowers. In addition to the

student-centered, curriculum-as-culture model, I explored and utilized the concepts in the

Understanding by Design (UbD) curriculum planning program. The resulting project embodied

aspects of my own curriculum philosophy- bridging a culture of construction, a culture of self

and spirit and backwards planning focusing on student understandings into a place-based

educational project for this case study.

A culture of construction.

“Constructivism is an epistemological view of knowledge acquisition emphasizing

knowledge construction rather than knowledge transmission and the recording of information

conveyed by others” (Applefield, Huber & Moallem, 2001, para. 9). This method grew partially

from many of the teachings of John Dewey, who said the role of student interest and imagination

was a strong factor in choosing the curriculum topics, but teachers must deliver the curriculum in

an organized and coherent facilitation (Dewey, 1938). According to Dewey, teachers are meant

to build upon past learning, know the children well, be organized, and have a plan (1938). Some

constructivist classrooms seem to take Dewey’s concepts further, almost eliminating the concept

of the teacher as the so-called deliverer of curriculum. According to Schnuit (2006), the culture

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

31

of construction “functions as a metaphor that describes a total environment where teachers share

the responsibility for what is learned with students” (para. 4). This particular culture deviates

from the current trend in education where the teacher acts as the purveyor of information and the

students are solely the recipients. The culture of construction relies on prior knowledge of a

subject matter and interest based on student background, culture, and family life and experience

at home. “For the learner to construct meaning, he must actively strive to make sense of new

experiences and in so doing must relate it to what is already known or believed about a topic”

(Applefield, et al., 2001, para. 15). In the constructivist culture, learning in the classroom grows

from student interest, class discussions and group interactions. According to Applefield et al.,

(2001) in a constructivist learning environment, “dialogue is the catalyst for knowledge

acquisition. Understanding is facilitated by exchanges that occur through social interaction,

through questioning and explaining, challenging and offering timely support and feedback”

(para. 16). Schnuit (2006) describes how the end result of constructed learning “demonstrates

new and complex understandings in students and becomes the object of assessment, rather than

the standard test model” (para. 4).

It is possible that when students have some control of what subject matter is being

presented and how they will be assessed, they react with less defiance. Young adolescence is

often met with adults asking students to be more responsible, yet the opportunities for students to

exert responsibility in their daily lives at school are still limited. Having students become a part

of curriculum planning in a cooperative, group-based learning environment is an organic answer

to this common power battle. As anyone who teaches in the middle grades understands, there is

an inherent need for students to interact with one another. Teachers often waste classroom time

trying to manage chatty students during a traditional, non-constructivist lecture format.

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

32

Allowing for small group discussion on a daily basis, as part of the structure, or culture of the

learning environment, could have enormous positive benefits when teaching the middle grades.

A study in Korea suggests that after a national constructivist approach to learning science was

instituted, 14-year-old students perceived their learning environments more positively (Kim &

Fisher, 1999).

Critiques of the constructivist theory of curriculum design.

C. A. Bowers, a co-founder of many of the principles of place-based education, maintains

an ardent opposition to the concept of constructivist culture classrooms. In his book, The False

Promise of Constructivist Theories of Learning (2005), he outlines how a constructivist

classroom can fail to fully meet the educational needs of the present time, based on a

multicultural and ecological point of view. Bowers (2005) draws from the fathers of the

constructivist movement -- Dewey, Freire, and Piaget -- to show that these thinkers and the

movement that has swelled in the last forty years is flawed in the current context of ecological

sustainability. Bowers (2005) argues that because constructivist classrooms are child-centered

and thus the curriculum content of these classrooms can be determined by student interest, there

is a large influence from consumer media. Bowers (2005) argues that in order to create a culture

of education that places natural systems and their conservation at its core, as he argues people

must do for human survival, how do ecological questions get asked and answered in an

constructivist environment? The ecological question that Bowers (2005) believes must be

addressed in education settings in order for our species to survive is: “What needs to be

conserved in the face of incessant technological and market driven change?” (p. xii) Bowers

(2005) addresses the ability of educators to answer this question in a constructivist classroom:

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

33

If acquiring this knowledge is viewed as irrelevant in a constructivist classroom and even

viewed as yet another resource of adult oppression, students are not likely to acquire a

knowledge of such hard-won traditions as the gains made in the areas of workers’ and

women’s rights, the separation of church and state, the right to a fair trial, the importance

of an independent judiciary rather than one packed with political ideologies that support

the classic liberal agenda of universalizing the idea of unrestricted market forces, and the

right to privacy and free expression- even when it differs from the antidemocratic forces

that are being nurtured by neoliberal think tanks such as the CATO Institute and talk

show hosts such as Rush Limbaugh. And if other traditions, such as those connected

with ethnic approaches to the growing and preparation of food, healing and mentoring in

the art of how to live lightly off the land, are also replaced by the student’s own

construction of knowledge—including their subjective decisions about what they want to

learn—they will lack the knowledge needed to resist the changes now being promoted by

the forces of industrial culture. (p.xi)

Bowers (2005) presents this case against constructivist curriculum design from his lens as a

place-based educational leader and forces other PBE educators to consider this present-day

challenge when incorporating constructivism in programs.

The culture of self and spirit.

This concept of culture was recently introduced by Bravmann (2000), but its ideals and

principles lie in the teachings of Montessori, Steiner, Dewey, Thoreau, Parker and Emerson

(Schnuit, 2006). Another way of approaching this kind of culture in theory is through the

concept of holistic teaching, a concept that acknowledges that students are more than test scores,

curriculum standards and future employees (Schnuit, 2006). The individual student is the center

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

34

of learning in this model, and students are encouraged to express their individuality through

interdisciplinary assessments. For example, a student may express the scientific concept of

electricity through an art project, or a student interested in writing may write a story about how a

certain superhero uses electricity. The core concept -- electricity -- and the state standard

prescribing this knowledge is reached, but the individual student can utilize his or her creative

faculties to demonstrate this knowledge. As with a constructivist classroom, here students are

self-driven to discover their own knowledge in a unique way, but they are also supported by peer

groups and materials provided by the teacher.

A holistic classroom may resemble what educators have come to understand as

interdisciplinary studies (Wineburg & Grossman, 2000) or curriculum integration (Beane, 1997).

In general, both curriculum integration and interdisciplinary studies infer that teachers

collaborate across what is normally a subject-specific approach in a classroom. Both integration

and interdisciplinary approaches create an environment where science teachers can draw upon

what would normally be segregated to social studies class. For example, students are posed the

question in science class: What was life like for early native peoples in our area? Students

explore this question through the aspect of scientific content standards (plate tectonics, geologic

time) and, at the same time, approach native peoples from an anthropological view in reading

and writing that is often segregated to social studies classroom. In this example, the disciplines

of science and social studies are utilized to compliment each other. By understanding a multi-

dimensional concept like the daily life of native peoples through a multi-disciplinary curriculum

approach, students are encouraged to put their learning together to form a holistic picture of early

Native American life.

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

35

Place-based education at its core is interdisciplinary in nature. Many PBE programs

combine disciplines for a holistic understanding and experience of place: science with writing,

art with science and math with writing. PBE programs use the environment as an integrating

context (EIC) for use across subject areas (Chawla & Escalante, 2007). Studies have found

using EIC successful for increasing test scores and grades, greater critical thinking skills, greater

motivation for achievement, and increasing the tendency toward environmental stewardship

(Chawla & Escalante, 2007).

Understanding by Design: A method for curriculum development.

Understanding by Design is a method for curriculum development that focuses on

designing content to target student understanding. Wiggins and McTighe (2005) suggest that

educators must make a shift when considering how to approach teaching and “thinking a great

deal, first, about the specific learnings sought, and the evidence of such learnings before thinking

about what we, as the teacher, will do or provide in teaching and learning activities” (p. 14). The

authors call this approach backward design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). In backward design a

teacher is beginning with the desired student understanding outcome (state standards, for

example) and then developing a unit based on big ideas or understandings (Wiggins & McTighe,

2005). This design suggests that teachers should not build their units from “the methods, books

and activities with which they are most comfortable” (2005, p. 15) but instead begin with “what

the learner will need in order to accomplish the learning goals” (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, p.

15). The proponents of the design suggest that when planned correctly, a curricular unit should

be able to create the answers to these questions by the students:

What’s the point?

What’s the big idea here?

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

36

What does this help us understand or be able to do?

To what does this relate?

Why should we learn this? (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, p. 16)

These questions can baffle some students in a more traditional way of curriculum planning,

where the teachers are using activities they feel comfortable with but lose student understanding

when it comes to relating the experience of the activity to a big idea that’s driving the unit. Or,

students who spend their time marching through textbooks and covering as much content in the

shortest period of time to fulfill content standards.

One of the major critiques of the constructivist classroom is that students will create their

own understandings, but their process can often be misguided or unduly influenced by the media

(Bowers, 2005). As place-based educators it is the goal to educate students to be engaged global

and local citizens with a strong sense of place. The backward design that the UbD process

proposes could function as a way to steer student learning and interest to place in order to

achieve the goals of the PBE educator. However, at the same time, PBE educators can use the

environment as an integrating context to utilize a constructivist approach to the creation of a

sense of place through a flexible interdisciplinary curriculum.

Concluding thoughts on the literature

There is a large gap between some children and nature. Richard Louv, in his highly

successful book Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-deficit Disorder

coined the term Nature-Deficit Disorder to discuss the negative aspects of this phenomenon

(2008). Ecopsychologists and Wilson’s biophilia hypothesis believe that this gap may have

many negative consequences for today’s children—specifically a feeling of alienation. I propose

to seek to educate students for a sense of belonging in their place. Place-based education can be

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

37

used as a vehicle to reconnect children to nature and educate for belonging in their place.

Including cosmology in the conversation of place-based education provides a more holistic

approach to educating for belonging. The current state of the educational system, with its focus

on standardized testing, provides challenges for educators to incorporate meaningful and place-

based educational content into curricular design. Curriculum theory suggests that a

constructivist approach to design combined with careful planning and guidance by the PBE

educator can be effective to educate students about their place. Research shows that students

engaged in meaningful, authentic tasks at school feel better about their education and are more

likely to participate in community stewardship (Zelezny, 1999). Stewardship is an indicator of

an engaged, active participant in the community, thus alleviating alienation and fostering a sense

of belonging.

Methodology

What is qualitative research? How is quantitative research different?

Qualitative research is a research design paradigm that uses words instead of numbers

(Creswell, 2009). Qualitative research also tends to ask more open-ended research questions

versus quantitative research (Creswell, 2009). While quantitative research is generally

concerned with numbers and statistics, qualitative research is more interested in perspectives of

humans in relation to a social phenomenon. Creswell (2009) offers a definition for these two

types of research:

Qualitative research is a means for exploring and understanding the meaning individuals or

groups ascribe to a social or human problem. The process of research involves emerging

questions and procedures, data building from particulars to general themes, and the

researcher making interpretations of the meaning of the data. Quantitative research is a

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

38

means for testing objective theories by examining the relationship among variables. These

variables, in turn, can be measured, typically on instruments, so that numbered data can be

analyzed using statistical procedures. (p. 4)

Due to the subjective and interpretive nature of my research questions -- the ability to

measure a sense of belonging in students as a result of a place-based educational project -- (see

Introduction) I chose to use qualitative methods. Merriam (1998) indicates that the product of

qualitative research is a descriptive body of information and the researcher is the primary data

collector and also analyzes the data. Patton (2002) explains the three types of ways to gather

qualitative findings: “1) in-depth, open-ended interviews, 2) direct observation and 3) written

documents” (p.4). These three elements make up the methods to gather qualitative data, but

there are numerous ways to interpret the data (Creswell, 2009). The interpretation of qualitative

data is called methodology. Methodology acts as the lens or world-view through which data is

interpreted, and theory is constructed. I chose to use a case study as my methodology.

Case study as a form of qualitative research

Case studies can be used to study a “single instance, phenomenon or social unit” (Merriam,

1998, p. 27). Patton (2002) describes the use of case studies as “a specific way of collecting,

organizing, and analyzing data; in that sense it represents an analysis process. The purpose is to

gather comprehensive, systematic and in-depth information about each case of interest” (p. 447).

In summary, the purpose of the case study in qualitative research is to create descriptive data

about a specific “case” and then display the findings in a product: the case study. Patton (2002)

identifies three steps in the process of creating a case study. After a researcher collects raw,

descriptive data it can then be compiled into a case record (Patton, 2002). In the case record,

“information is edited, redundancies are sorted out, parts are fitted together, and the case record

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

39

is organized for ready access chronologically and/or topically” (Patton, 2002, p.449).

Information is then organized into a narrative (the product) directed at a specific audience.

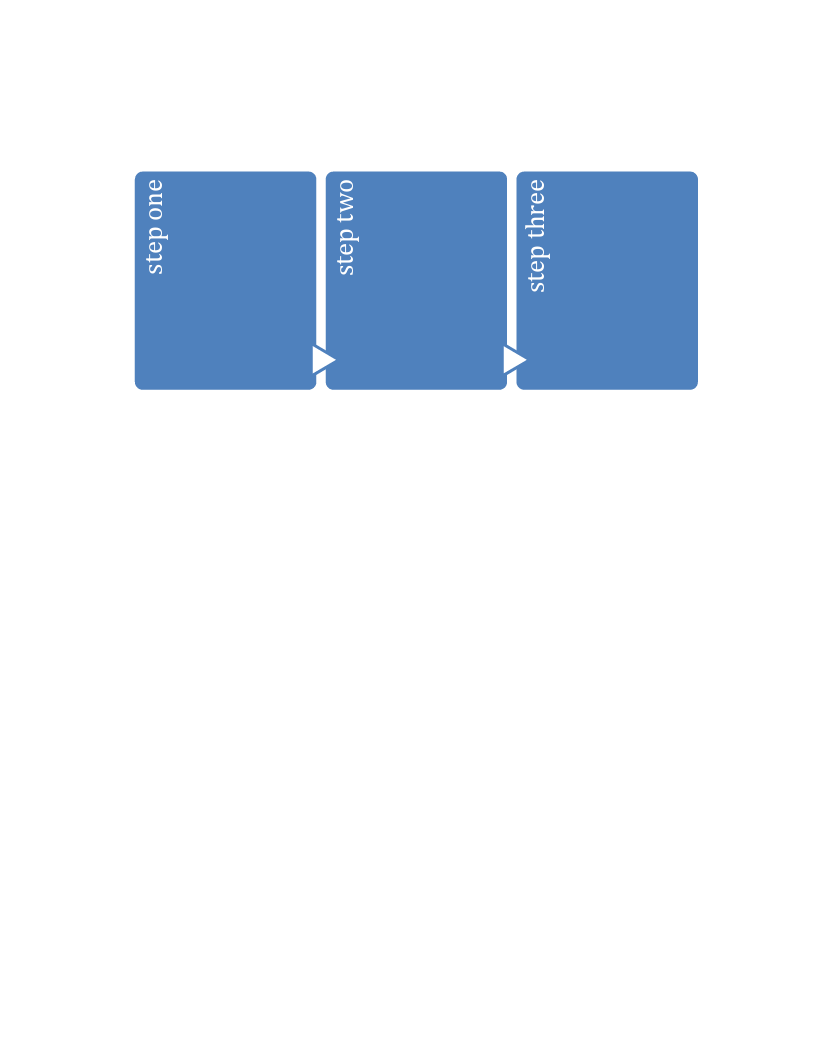

Gather the raw

descriptive

data from

surveys,

interviews and

participant

observation

field notes.

synthesize

data to form a

case record

compile the

case record

and raw data

into a case

study

narrative

Diagram 1: The three steps to creating a case study. (Adapted from Patton, 2002, p. 450).

According to Creswell (2013) the hallmark of a good case study is that it uses a multitude of

data-gathering techniques to gather in-depth information about a specific case. These techniques

include documents, observations and interviews conducted over an extended period of time. Yin

(2009) recommends collecting six types of information: archival records, direct observations,

participant observations, artifacts from the process, and interviews. Once the data is collected,

and the researcher is preparing a case record, the researcher can then choose whether to use

holistic analysis or embedded analysis of the data. Holistic analysis involves looking at the case

as a whole, and embedded analysis involves singling out a specific aspect of the case as a focus

(Yin, 2009). As a part of the case study record and ultimately the case study narrative (see

diagram on previous page) the researcher outlines a history of the case, the timeline or

chronology of the case study (Creswell, 2013). After the description, then the researcher can

then look at themes that emerged from the case or a few key issues that arose (Creswell, 2013).

Finally, the researcher addresses the meaning of the case and implications the case may have the

specific issue studied (Creswell, 2013).

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

40

I chose the case study as my methodology because it is the best choice for “variables that

are so embedded in the situation as to be impossible to identify ahead of time” (Merriam, 1998,

p. 32). I also only had access to a very small sample size, 16 students, thus making some other

methodologies unreliable. My sample population was a group of middle school students from

the Village Charter School in Santa Rosa, CA. Village Charter is a public, independent charter

school. The students ranged in age from 11 to 14. The population was also composed different

levels of 6th through 8th graders. These are my students that I teach in an interdisciplinary middle

school classroom. All but three students had attended this school for more than two years. A

large part of the mission statement of the school includes a connection to nature. These students

have had access to weekly hiking trips and outdoor camping trips from previous classes. Many

parents in class also value the importance of experiences in nature. There were six boys and ten

girls.

Again, because my sample size was so small, it was impossible to use many other

methodologies or to gain statistical significance in my data. However, my small sample size and

my direct, unobstructed access to them allowed me to deepen my study to gather much

descriptive data, whereas a larger sample would have limited the amount of time spent with the

group of students.

Methods: A mixed approach to qualitative research

I used a mixed-method approach of qualitative methods for my case study research. Patton

(2002) refers to the mixed method qualitative approach as triangulation, which is a term taken

from land surveying. According to Patton (2002), “knowing a single landmark only locates you

somewhere along a line in a direction from the landmark” (p. 247). Metaphorically speaking,

using triangulation in qualitative research helps strengthen the results because it can provide

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

41

more than one anchoring point of descriptive information. Studies that use only one method are

vulnerable to errors or bias that can be inherent in that method (Patton, 2002). Creswell (2013)

and Yin (2009) also address the need for multiple methods when collecting data for a case study.

Method #1: pre and post surveys.

It is important to consider how to carefully craft surveys and the questions therein to

eliminate bias (Henderson & Baileschki, 2002). Creating good survey questions is paramount to

creating objective data (Henderson & Baileschki, 2002). I thought it was interesting to consider

how some questions can be leading, or otherwise influence the participants because of the actual

wording of questions. Short and concise questions are the most effective for survey design

(Henderson & Baileschki, 2002). Including directions on the survey can help to clarify the

intent of a researcher. It is important to state the purpose of the survey -- what one is trying to

determine -- so that people feel more inclined to answer. The title of the survey can provide this

same purpose. Instead of titling the survey, I explained verbally to students during the pre- and

post-test that the survey was my way of knowing what they thought about their place, the

importance of plants and the ethno-botanical knowledge associated with them. In addition, I was

looking to gain insight to their knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors related to being in nature. I

emphasized to students that their answers were not for credit and that their participation was

completely voluntary.

First, I used a pre and post survey that asked students about the number of local plants they

can identify and how they feel about their connection to their local land. The survey also asks if

students can identify uses for local plants. I asked the question about whether or not students

feel “connected” to their local place and whether they feel it is important to know about local

plants. Finally I asked in the survey if they feel inclined to work in a profession that may help

EDUCATING FOR BELONGING

42

“save the earth.” I used the same survey pre and post to determine the change in beliefs,

knowledge and behaviors after the place-based educational project (See Appendix A). The