International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Article

The Effects of a Health Promotion Program Using

Urban Forests and Nursing Student Mentors on the

Perceived and Psychological Health of Elementary

School Children in Vulnerable Populations

Kyung-Sook Bang 1 , Sungjae Kim 1, Min Kyung Song 2,* , Kyung Im Kang 2 and

Yeaseul Jeong 2

1 Faculty of College of Nursing, The Research Institute of Nursing Science, Seoul National University,

Seoul 03080, Korea; ksbang@snu.ac.kr (K.-S.B.); sungjae@snu.ac.kr (S.K.)

2 College of Nursing, Seoul National University, Seoul 03080, Korea; fattokki@snu.ac.kr (K.I.K.);

Jeongfm1@snu.ac.kr (Y.J.)

* Correspondence: mk0408@snu.ac.kr; Tel.: +82-2-740-8467

Received: 3 July 2018; Accepted: 9 September 2018; Published: 11 September 2018

Abstract: As problems relating to children’s health increase, forest therapy has been proposed

as an alternative. This study examined the effects of a combined health promotion program,

using urban forests and nursing student mentors, on the perceived and psychosocial health of

upper-grade elementary students. The quasi-experimental study ran from June to August 2017,

with 52 upper-grade elementary students from five community after-school centers. With a purposive

sampling, they were assigned to either an experimental group (n = 24), who received a 10-session

health promotion program, or to a control group (n = 28). Seven undergraduate nursing students

participated as mentors. Running over 10 weeks, each weekly session consisted of 30 min of

health education and 60 min of urban forest activities. Data were analyzed by independent t-test,

Mann-Whitney U-test, paired t-test, or Wilcoxon signed rank test. General characteristics and

outcome variables of both groups were homogeneous. The experimental group showed significant

improvement in self-esteem (p = 0.030) and a significant decrease in depressive symptoms (p = 0.020)

after the intervention, compared to the control group. These results suggest that forest healing

programs may contribute to the spread of health promotion programs that make use of nature.

Keywords: forests; mentors; health promotion; school-aged children

1. Introduction

In Korea, even school-aged children experience a high level of stress, anxiety, depression,

and mental health problems [1]. In addition, the lack of physical activity due to sedentary lifestyles

causes physical health problems such as an increase in obesity and decrease of physical strength [2].

Meanwhile, school violence has been increasing annually, and one possible cause of this problem is

the lack of social interaction and emotional connection in modern society, caused by the increase in

individualistic activities and computer use, and the decrease of contact and interaction with nature [3].

Kaplan and Kaplan [4] emphasized that the natural environment may be the best place to regain

our attention and focus, and these benefits have also been shown to occur in children. Nature helps

children to improve their psychological functioning [5], to cope with their problems, to think clearly,

and to feel free and relaxed [6].

Recently, there has been considerable and increasing global attention towards using the forest

environment as a place for recreation and health promotion. It has been noted that activities in the

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977; doi:10.3390/ijerph15091977

www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

2 of 11

forest contribute to promoting physical and emotional well-being [7]. Forest healing refers to actions

that enhance the health of the human body by utilizing various elements of the forest such as the

landscape, phytoncide, water, wind, scent, and sound [8].

Countries such as the United Kingdom, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland are highly interested

in situating children’s education in nature. Learning outside the classroom takes place in a variety

of forms, including Forest School programs, outdoor sports, activities on school grounds, and visits

to beaches and parks in the local community. The purpose and benefits of these experiences are

also varied. Some focus on raising self-esteem and confidence; some on social skills, communication,

and teamwork; and others on physical development and health [9,10]. Based on a systematic review,

McCormick [11] reported that access to green space was associated with improved mental well-being,

overall health, and cognitive development in children. Although some previous studies have reported

positive effects of forest therapy on children’s mental health [12,13], nature-based intervention or

education in Korea is still very limited.

In another aspect, a global trend shows differences in health status according to socioeconomic

level, and various policies are being tried to reduce the gap. In Korea, one of the child welfare policies

provides after-school care-giving at public “community centers for children” for low-income families

with elementary- or middle-school students. However, the main services provided to children in

these centers focus on educational or nutritional support, which does not provide integrated care

in terms of the child’s physical, mental, and social aspects. In particular, there are no professional

health-related services.

Therefore, in this study, we developed an integrated health promotion program including outdoor

activities in a forest or urban park for the children attending community centers. The program was also

expected to promote perceived health status and self-esteem, to reduce the symptoms of depression,

to improve concentration through exposure to various resources of nature, and to enhance sociality

through the use of group activities.

In addition, a special component of this study was that nursing students participated as mentors.

When considering the developmental characteristics of school-aged children, it is possible to promote

more active participation through forming relationships with college student mentors, who are more

likely to encourage friendship and admiration. For the nursing students, participating in health

promotion programs for children in vulnerable populations will be an opportunity to enhance their

understanding of children’s developmental characteristics, and to form therapeutic relationships.

Purpose of Study and Hypotheses

The purpose of this study was to develop a combined health promotion program using urban

forests and nursing student mentors for vulnerable school-aged children and to evaluate the effects of

this program on the perceived and psychological health of elementary school students in vulnerable

populations. Specific hypotheses in this study were as follows:

1. The improvement in the perceived health status of children between pre- and post-program

will be greater in the experimental group than in the control group.

2. Gains in self-esteem, peer relationships, and of sympathetic to parasympathetic autonomic

balance and reductions in depression, attention deficit, and hyperactivity (ADHD) between pre- and

post-program will be greater in the experimental group than in the control group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This quasi-experimental study, based on a control group pre-test–post-test design, was planned to

develop a 10-session health promotion program using urban forests and nursing student mentors and

to investigate its effects on elementary-school students in grades 4 to 6 at five community centers for

children in Seoul. These community centers for children are public social welfare facilities that provide

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

3 of 11

cInatr.eJ.sEenrvviriocne.sRfeos.rPvubulilcnHeeraaltbhle20c1h8,i1ld5,rxen. The children who use these centers are mostly from low-inc3oomf 1e1

families. Community child centers for children perform various important roles in community welfare,

iinncclluuddiinngg ooffffeerriinngg pprrootteeccttiioonn aanndd aafftteerr--sscchhooooll eedduuccaattiioonn pprrooggrraammss,, pprroovviiddiinngg hheeaalltthhyy rreeccrreeaattiioonnaall aanndd

ffrreeee--ttime programs, and linking chhiillddrreenn’’ssppaarreennttsswwiitthhtthheeccoommmmuunnitiyty[1[144].].

TThhee ssttuuddyy wwaass aapppprroovveedd bbyy tthhee EEtthhiiccss CCoommmmiitttteeee ooff tthhee IInnssttiittuuttiioonnaall RReevviieeww BBooaarrdd aatt SSeeoouull

NNaattiioonnal UUnniivveerrssiittyy ((IIRRBB NNoo.. 11770077//000033--000011)).. BBeefoforerebbeeggininnniningg tthhee ssttuuddyy, participants and tthheeiirr

ppaarreennttsswweerreepprroovviiddeeddwwiitthhaa thoroouugghh descripttiioonn of the study’s objectives, experimental procedure,

aanndd measuremenntt ttoooollss..OfOtfhethcehiclhdirlednreanndanpdarpenatrsenwtshowdheocidecdidtoedpatroticpiaprattieciipnatehisinsttuhdisy,sthuodsye,

twhohsoe swuhbomsiuttbedmithteedirthweriirttwenritcteonnsceonntsewnetrwe eirnecilnucdleuddeidn itnhtehestsutduyd.y.CChhilidldrerennwwhhoo had mmeeddiiccaall

ccoonnttrraaiinnddiiccaattiioonnsstotoexeexrecricsiesebybyselsfe-rlfe-preoprto(ret.g(e.,.ga.s,thamstha,mpaa,inpfauilnofustleosatrethorairttihs)riwties)reweexrceluedxecdlu. dAetdo.taAl

otof t5a9l sotfud59ensttsuidnegnrtasdiensg4rtaod6esat4fitvoe6coamt fmivuencitoymcmenutenristypacertnicteiprsatpeadritnicitphaistesdtuidny.thWisitshtuadpyu.rWpoistihvea

spaumrppolisnivge, tshaemypwlinerge, tahsesyigwnedretaosesigthneerdatno exitpheriamneenxtpalergirmouenptathl gatrowuapstphraotvwidasedprwovitihdead1w0-istehsasi1o0n-

hsesaslitohnphroeamltohtipornomprootgiornamprwogitrhamnuwrsitihngnustrusidnegnsttmudeennttomrse(nnto=r2s7(n) o=r2a7)corntarocol ngtrrooul pgr(onu=p3(n2)=. O32f).thOef

5th9ech5i9ldcrheinldirnengriandgesra4dteos64attot6heatcothmemcoumnimtyucneinttyercsenfoterrcshfioldrrcehni,ld57reang,r5e7edagtorepeadrtiocippaartteiciniptahte sintutdhye.

Tsthueddya. tTahoefd5a2tachoifld5r2ecnhwilderenfiwnaelrley fainallyyzeadn,alwyzitehdt,hweitehxctehpeteioxnceopftionnsinofceinresirnecseproenrseesspothnasteswtehraet

iwdeenretifiidedenbtyifibeedinbgymbaeriknegdmwaitrhkethdewsaimthetnhuemsbamerse onnuamllbieterms os nofatlhleitqeumestioofnnthaeirequeveestniothnonuagirhe tehveeren

wtheoruegrhevtehresree qwueersetiroenvser(sne=qu3e),sptiaorntsic(inpa=t3io),npianrtfiecwipeartitohnainnfifevwe eserstshiaonnsfiv(ne =se1s)s,ioannsd(nth=o1se), tahnadt twheorsee

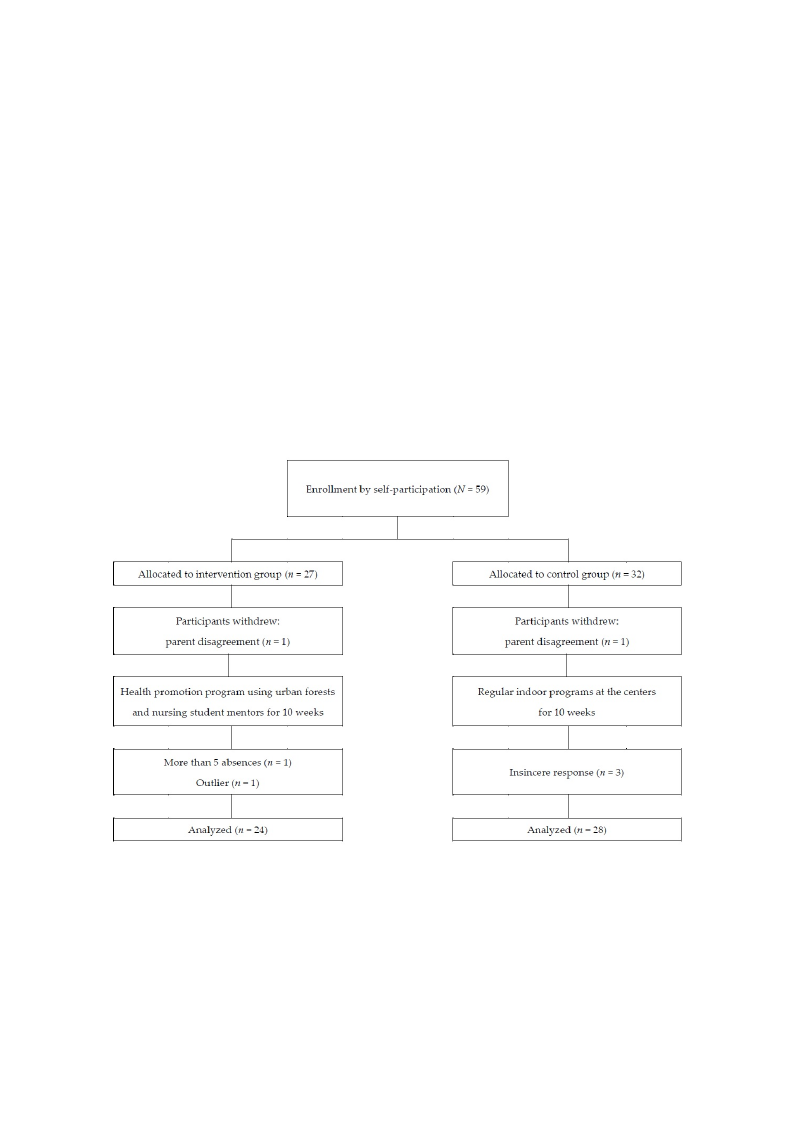

othuatltiewrseraenoduptlrieesresnatned pasreasnenetxetdreamseavnaelxutereomn ethveadluaetaodnitshtreibduattiaondi(sntr=ib1u;tFioignu(rne=1)1.; Figure 1).

FFiigguurree 11.. RReeccrruuiittmmeenntt ooff ppaarrttiicciippaannttss..

22..22.. IInntteerrvveennttiioonn

tocoloc3heonno0necmmmtpaluamehmAiArcsnyseutyuysucscnfsinosoroctoitiemtreametnymyltambhbacpnaieaeincndhntntedlieyieenc6tcdsdecp0tirrtercsh.huemreyaeTv.ervlciaeaihnihTaeleleatontwhwfhhnso1deodp0rp[[cp-1r1t16rsihos5o0a05eyme]-lm]smscshfaeoahiooeniostnontraisndiedosloifstoonhonhtancarepaipaanatcnrnhhrlletotoeideehehgvegadferidfprlotoaastaisrhrmrelmoeteasahmssspsuittusnasrosaeeseontisctxisnimhdnstopsigmegmnveofouirutuepetiirrrnieronreebbbnotntssaaacgt[nin[ne1rnpe1a6ffax6rftmoo]oocph]rrtrgweeeeiweuvrrssusaasititatetirsssmssninb,eagadwacsdnnenu.euehddsEsasfriiioicbancgnnghtrcaunguinehnvrwersesidssutfdtieseioinrnr,esrfbegfwsgsoeoa.is1rsorhnstE0ttsnicuucacmhfchdachdooihlieilrellwnndnoednssrstcearetietasermwsmsntetnseeaeie1cddoaynano0nttto3nttfmtoeor0feasronrnillismsmselnddotcbbieiacitnnaenaduawsagsgtrfeceeaoeodhaddysraf

cforommmeuancihtyccoemnmterunfoitrychceilndtreernf.oTrhcehsiltdurdeyn.dTevheelostpueddyadwevrietltoenpepdroagwrarmittmenanpuroagl rfoamr thmeainnutearlvfeonrtitohne

pinrotevrivdeenrstitoonenpsruorveitdheersadthoereennscue rteo tthheeinatedrhveernetniocne ptroottohceol ianntdercvoennstiisotenncpyrothtorocuolghaonudt thcoenpsriosgternamcy

throughout the program implementation. The program was provided once a week for 10 weeks, from

June to August 2017. The control groups attended only the routine programs (e.g., supplementary

learning such as math or English, reading, art) at their community center for children.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

4 of 11

implementation. The program was provided once a week for 10 weeks, from June to August 2017.

The control groups attended only the routine programs (e.g., supplementary learning such as math or

English, reading, art) at their community center for children.

The program was conducted by the research team, all of whom were registered nurses whose

majors were either child health or psychiatric nursing. One of them was a certified forest therapist,

and one had completed the approved training course for forest therapy. During the sessions, two forest

day camps were included; those were run by an external forest therapist. A total of seven nursing

student mentors were involved in activities to facilitate the program and to promote the participation of

children. The orientation was conducted before the start of the health promotion program to minimize

any differences between the mentors. The major content of the orientation included an introduction of

forest therapy, the specific contents and activities of the program, and the roles of mentors. Each mentor

was responsible for three to four children, and two research team members supervised the mentors. In

addition, the mentors shared significant matters that occurred during the program through the closed

social network service (Kakao group talk), and their activities, feelings, and opinions were submitted

anonymously through the Google questionnaire. The feedback from the forest therapist of the research

team was provided and shared with all mentors. A social worker working at the community center for

children accompanied the activities as an assistant for child safety. Table 1 shows the topics, contents,

and time duration of each session.

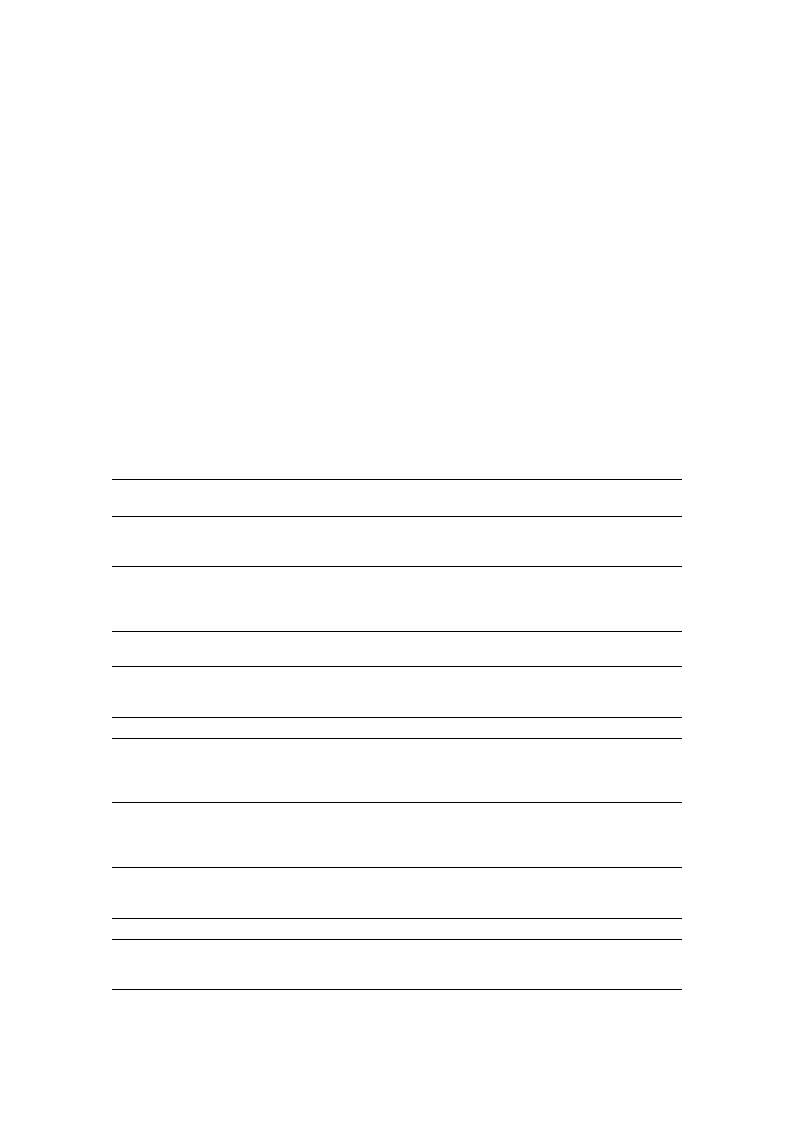

Table 1. The topics of program sessions.

Session

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Lecture

Forest Therapy

Program orientation

Meeting with mentors

Pre-test

Understanding the

relationship between physical

and psychosocial health

Making a nickname for natural

objects that resemble me

Five senses experience in

urban forest

Personal hygiene and

eating habits

Physical activities in forest (I)

-Forest walking and exercise

Internet overdependence

Playing with natural materials (I)

-Making a paper fan with dry

flowers and leaves

Forest day camp (I)

Self-emotion awareness and

expression

Playing with natural materials (II)

-Rock-paper-scissors game with

natural materials

-Water carrying using leaves

Self-esteem

Self-expression activities with

natural materials

Making a bracelet of

retinispora beads

Communication and peer

relationships

Physical activities in forest (II)

-Cloth volleyball

-Traditional play

Forest day camp (II)

Completion ceremony

Discussion with mentors

Post-test

Program Duration

(hours)

2

2

2

2

4

2

2

2

4

2

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

5 of 11

2.3. Measurements

Participants’ height and weight were measured using an automatic stadiometer (BSM 370,

Inbody Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). Heart rate variability (HRV) was also measured using a portable

electrocardiograph (LXC3203, LAXTHA Inc., Daejoen, Korea). To minimize changes in autonomic

nerves, HRV was performed after stabilization for at least 5 min, taking 5 min to complete the

measurement. In this study, the HRV parameters were measured by a frequency domain analysis.

The ratio of low frequency to high frequency (LF/HF ratio) in HRV was used to represent a measure of

sympathetic to parasympathetic autonomic balance of the participants [17].

A pilot test using a self-report questionnaire was administered to elementary school students in

grades 4–6 who did not participate in this research. As a result, it was confirmed that the students in

upper grades did not have any difficulty in completing the questionnaire, which took about 20 min to

complete at each time point. The specific instruments provided on the questionnaire were as follows.

Perceived health status. Perceived health status of participants was assessed by a single-sentence

question: “How do you feel about your overall health condition?” It was rated as “very good (5 points),”

“good (4 points),” “moderate (3 points),” “bad (2 points),” or “very bad (1 point).”

Self-esteem. Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) [18] which

includes 10 statements. Each statement is rated on a 4-point Likert scale with 4 = “strongly agree,”

3 = “agree,” 2 = “disagree,” and 1 = “strongly disagree.” The negative items were scored in reverse

order. All items were added together with scores ranging between 10 and 40; a higher score means a

higher level of self-esteem. At the time of tool development, the Cronbach’s alpha was reported as

0.88; the Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.85.

Depression. The Korean version of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [19] was selected for

assessment of the participants’ depressive symptoms. There are 27 items quantifying depressive symptoms

such as depressed mood, hedonic capacity, vegetative functions, self-evaluation, and interpersonal

behaviors. Each item has a 3-point Likert scale as 0 = “absence of symptoms,” 1 = “mild or probable

symptom,” and 2 = “definite symptom,” and a higher CDI score means a higher level of depressive

symptoms. Han and Yoo [19] reported the Cronbach’s alpha as 0.81 for CDI in elementary and middle

school students; the Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.87.

Peer relationships. The peer relationship instrument [20] consisted of 20 questions for

measuring the presence and reliability of friends, persistence of and adaptation to peer relationships,

and communal life with friends. This instrument uses a 5-point Likert scale 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “very

much,” and the higher the total score, the higher the level of the peer relationships. Kim [20] reported

the Cronbach’s alpha as 0.94 for peer relationships for elementary school students, and the Cronbach’s

alpha in the present study was 0.90.

Attention deficit and hyperactivity. The Korean version of Conners-Wells Adolescents Self-Report

Scales (CASS-S, short form) [21] was used to assess the level of attention deficit and hyperactivity of the

participants. This instrument includes 27 statements that evaluate behavior and cognitive problems,

the level of hyperactivity, and ADHD indicators of respondents using a 4-point Likert scale from

1 = “not at all” to 4 = “it really is.” Higher scores indicate greater hyperactivity. As a result of the

reliability test of CASS (S), the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77; the Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.88.

2.4. Statistics

After normality tests using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Shapiro-Wilk test, an independent

t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test was used to determine any differences in pre-test data between the

experimental and control groups. Post-test data analyses were conducted using an independent t-test

or Mann-Whitney U-test for comparison between groups, and a paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank

test was employed for intragroup comparisons. The effect size was calculated using the effect size d

for the parametric data and the effect size r for the non-parametric data [22]. Interpretations of d and r

are as follows: d = 0.2 (small effect size), d = 0.5 (moderate effect size), d = 0.8 (large effect size), r = 0.1

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

6 of 11

(small effect size), r = 0.3 (moderate effect size), r = 0.5 (large effect size) [23,24]. SPSS for Windows

Version 22.0 was used for all data analyses, and the statistical significance was set at p = 0.05.

3. Results

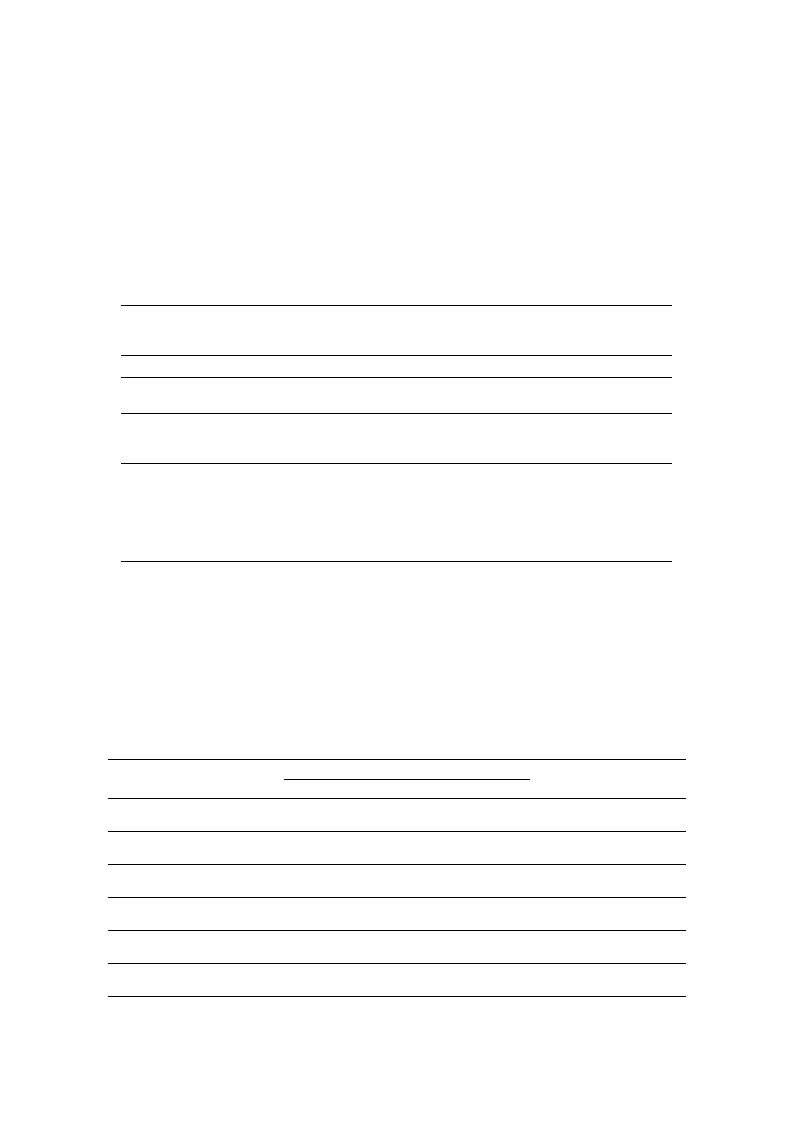

There was no significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the

homogeneity test of general characteristics and outcome variables. The demographic characteristics

and outcome variables of the groups are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Homogeneity test of participants’ demographic characteristics and outcome variables during

the pre-test (N = 52).

Exp. (n = 24) Cont. (n = 28)

Characteristics/Variables Categories

n (%)

n (%)

χ2/t/Z

p

M ± SD

M ± SD

Age (years)

11.83 ± 0.82

11.75 ± 0.97

0.33

0.741 †

Gender

Male

Female

8 (33.3)

16 (66.7)

14 (50.0)

14 (50.0)

1.47

0.225 ‡

Grade

4th

10 (41.7)

11 (39.3)

5th

8 (33.3)

9 (32.1)

0.09

0.958 ‡

6th

6 (25.0)

8 (28.6)

Perceived health status

Self-esteem

Depression

Peer relationships

Attention deficit and hyperactivity

LF/HF ratio

4.04 ± 0.95

31.42 ± 5.48

12.26 ± 7.99

79.27 ± 12.34

15.09 ± 9.26

1.02 ± 0.58

3.68 ± 1.12

31.86 ± 5.06

9.39 ± 7.27

78.54 ± 13.77

14.85 ± 11.57

1.67 ± 1.38

−1.31

−0.04

−1.33

0.20

−0.66

−1.83

0.191 §

0.971 §

0.184 §

0.845 †

0.507 §

0.068 §

Exp.: experimental group; Cont.: control group; LF: low frequency; HF: high frequency; M: mean; SD: standard

deviation; † t-test; ‡ χ2 test; § Mann-Whitney U-test.

Table 3 shows the comparison of pre- and post-test mean scores for the experimental and control

groups. In the experimental group, self-esteem was significantly increased (p = 0.030, d = 0.47),

and depression was significantly decreased (p = 0.020, r = −0.48) after the intervention. No statistically

significant changes were found in the control group. This means that this program was partly effective

in improving children’s psychological health.

Table 3. Comparisons of changes in outcome variables between the experimental and control groups

(N = 52).

Variables

Group

Pre-Test

Post-Test

M ± SD

Difference

t or Z

p

ES

d/r

Perceived health

status

Exp.

Cont.

4.04 ± 0.95

3.48 ± 1.12

4.21 ± 0.83

3.86 ± 0.97

0.17 ± 0.96

0.18 ± 1.22

0.76

0.449 ‡ 0.15

0.62

0.538 ‡ 0.12

Self-esteem

Exp.

Cont.

31.42 ± 5.48

31.86 ± 5.06

33.21 ± 4.35

30.43 ± 5.03

1.79 ± 3.79

−1.43 ± 4.73

2.32

−1.12

0.030 †

0.265 ‡

0.47

−0.21

Depression

Exp.

Cont.

12.26 ± 7.99

9.39 ± 7.27

9.67 ± 6.44

8.57 ± 6.86

−2.74 ± 5.55

−0.82 ± 4.44

−2.32

−0.63

0.020 ‡

0.531 ‡

−0.48

−0.12

Peer relationships

Exp.

Cont.

79.27 ± 12.34 78.96 ± 11.11 −0.43 ± 12.34

78.54 ± 13.77 80.36 ± 13.40 1.82 ± 9.10

−0.16

1.19

0.875 †

0.236 ‡

−0.03

0.22

Attention deficit

and hyperactivity

Exp.

Cont.

15.09 ± 9.26 15.58 ± 11.99

14.85 ± 11.57 14.14 ± 9.77

0.22 ± 7.50

−0.48 ± 9.85

0.14

−0.25

0.891 †

0.802 †

0.03

−0.05

LF/HF ratio

Exp.

Cont.

1.02 ± 0.58

1.67 ± 1.38

1.05 ± 0.61

1.45 ± 0.95

0.03 ± 0.71

−0.22 ± 0.98

0.19

−1.20

0.849 †

0.241 †

0.04

−0.23

Exp.: experimental group; Cont.: control group; LF: low frequency; HF: high frequency; M: mean; SD: standard

deviation; ES: effect size; † paired t-test; ‡ Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

7 of 11

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a combined health promotion program

using urban forests and nursing student mentors on the perceived and psychological health of

elementary-school students. Previous studies have performed forest activities or green activities [25–30]

or mentoring programs [31–34], but we expected positive reinforcement by not only using forest

activities but also mentors in this study. As a result, self-esteem and depression were significantly

improved in the experimental group, who participated in the health promotion program.

Previous forest activity studies conducted with children and adolescents reported that forest

activities had positive effects on mental and physical health, including conditions such as ADHD,

anxiety, depression, high blood pressure, and the lack of physical activity [11,35,36]. Also, a previous

systematic review has reported that urban green space can increase physical activity levels, and access

to urban green space also reduces stress and improves mood and the quality of life for people of all

ages [37].

It has also been reported that green exercise has a positive effect on self-esteem and social

interaction for adults [26]. Further studies that have examined the effectiveness of forest activity

programs for children in community centers for children in Korea also reported improved children’s

self-esteem [12,27]. In this study, after participating in the program, the self-esteem of the experimental

group increased by 1.79 ± 3.79, whereas that of the control group decreased by 1.43 ± 4.73, indicating

that the program improved self-esteem. However, some studies have reported that playing in nature

has no significant effect on children’s self-esteem [25,30,38]. These researchers argue that children

and adolescents may not receive the benefits of nature-friendly interventions because they do not

experience the same level of connection with the natural environment as adults. Studies on the effects

of forest camps and forest schools on improving psychological health outcomes, including self-esteem,

have commented on the necessity of the direct use of the natural environment and suggested activities

that use natural environments such as camping and horticulture [39]. In his book Last Child in the

Wood, Louv [40], who had earlier attracted the attention of the world by emphasizing the need for

contemporary children to be in contact with nature, has accumulated the positive effects of nature on

children’s relaxation, self-worth, and self-esteem. He especially emphasized the importance of nature

itself and did not focus on the structured program, but instead focused on giving them a chance to

connect with and have free play in nature. Also, it was revealed that children who participated in

camp demonstrated improved initiative and self-direction that transferred to their lives at home and

in school. Therefore, children may need more time for direct interaction with or exploration in nature,

as well as further structured interventions beyond simply playing in the forest, to have a more positive

effect on self-esteem. In this study, the positive effect on self-esteem may be attributed to the direct

interaction with nature activities and nursing student mentors in the intervention.

Also, by spending more time in and feeling the benefits of nature in a calm and natural

environment, children’s nervous systems can relax from the resulting increase in parasympathetic

nerve activation. While not found in this study, several previous studies with adults reported that

forest activity leads to an activated parasympathetic nervous system, enhanced HF components of

HRV, and lower LF/HF as a positive relaxation effect of forest therapy [41–43]. In previous studies

that provided forest-based interventions, assessments of the effect were made immediately after the

intervention. But in the present study, a post-test was performed one week after the last program was

provided, which may have increased confounding factors. Therefore, further research is needed to

consider the timing of measurement.

The differences in depressive symptoms within the group decreased in the experimental group

(2.74 ± 5.55) and the control group (0.82 ± 4.44) in this study, but only that of the experimental group

was statistically significant. In a systematic review of the effects of forest therapy on depression,

forest therapy has been reported to be a new and effective intervention in reducing depression in

elementary-school students as well as adults [15,44]. According to the meta-analysis, which evaluated

the effectiveness of the forest-related programs, forest-related programs showed the greatest effect

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

8 of 11

on depression (ES = 1.358) among psychological outcome variables, and self-esteem (ES = 1.269) and

sociality (ES = 1.281) showed high effect sizes [45].

In this study, mentors seemed to function as an effective intervention tool, in addition to the forest

activities. There was a positive effect of self-understanding, confidence, and achievement through the

participants’ relationships with the mentors, which might reinforce the participants’ internal factor.

This result shows a similarity to the results of previous studies that explored the effect of mentoring

programs [31,34], in which the relationship between mentors positively affected the psychological

health of vulnerable youths. According to the qualitative study of Akrimi, et al. [46], which explored

the experience of school-aged children participating in a charity mentoring program with volunteer

university-student mentors, the unconditional and supportive relationship between the children and

mentors were commonly experienced. The developments of social-emotional, cognitive, and identity

of the youth are accomplished based on their emotional connectedness with mentors and result in

positive outcomes for the youth [33].

Previously, Kim [32] explored the competence of mentors using the Delphi analytic approach.

Interpersonal skills, observation ability, and communication ability are necessary competencies for the

mentors. With these skills, mentors can consider and respect themselves and others, sense mentees’

changes, and make accurate communication. These skills are emphasized in the field of nursing. For

example, the Nursing and Midwifery Council [47] suggested communication and interpersonal skills

as one of the standards for competence of registered nurses; therefore, educational nursing institutions

should focus on educating their students to foster these abilities through the program. Thus, through

the nursing students’ participation as mentors, they spontaneously formed supportive relationships

with youth and educed children’s psychological and emotional development. An online survey and

interviews were conducted for a qualitative study about the experiences of seven nursing students

participating in this health promotion program. The qualitative study of the nursing students was

undertaken at the same time as the evaluation of the children, but that the results have been reported

separately [48]. As a result of qualitative research, this program was helpful for nursing students, as it

provided opportunities for them to interact with and understand children.

Meanwhile, the peer relationship questionnaire item, used as an indicator of sociality, includes

questions about the presence of friends, reliability, and continuity of friendship; it showed no significant

difference between the groups. The questions about peer relationships mainly focus on the relationships

with school friends, and thus the improvement of relationships with other children at the community

center may not be reflected.

This study has some limitations. First, it was not possible to confirm whether the effect

of the intervention was due to the mentoring or the urban forest activities because the health

promotion program in this study utilized both urban forest activities and mentoring. Therefore, future

studies will be required using a design to identify the individual effects of the forest activities and

mentoring, and advanced analyses, such as mediation analyses. Such analyses will provide a clearer

understanding of each component on the intervention. Second, it was a quasi-experimental study in

which randomization was not used in place of intervention or assignment of the study participants.

Community centers for the children participating in the study were selected based on accessibility

and preference, which could lead to an imbalance or bias between study conditions and may have

influenced subsequent analyses. Third, though both groups did not significantly differ at the baseline

(as a result of lack of power), there seems to be a substantial difference in gender distribution among

intervention and control condition. Particularly since girls might be more “vulnerable” to psychosocial

health outcomes than boys [49,50], the influence of gender on the effectiveness of intervention cannot

be ruled out. Fourth, consideration should be given to more diverse outcome variables such as

emotions, which have been the most studied responses to green exercise [51]. As the health promotion

program consisted of 60 min of activity after 30 min of lecture, there was not enough time allocated to

being active in the forest, except for the time to move to the urban forest. It is also possible that the

participants felt less interested in the program because they felt that the indoor lectures formed part of

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

9 of 11

the classroom. Future research with a structured outdoor activity-focused program is recommended,

and consideration should be given to encouraging the interest of the research participants. Also,

more appropriate outcome measures might be required to identify the benefits of the program across

multiple outcomes.

Despite these limitations, this program has visible strengths incorporating the feasibility of forest

therapy as a health promotion program, which makes use of readily accessible urban forest parks,

and the participation of nursing students as mentors, which might strengthen the psychological

support for the participating children.

5. Conclusions

Our study showed that a combined health promotion program using urban forests and nursing

student mentors significantly improved self-esteem and depression of elementary-school students in

community centers for children. It is important that the forest healing program, which is growing in

worldwide interest, has been applied to Korean children and that the perceived and psychological

health effects have been grasped, which will contribute to the spread of health promotion programs

using nature in the future.

Author Contributions: K.-S.B. contributed toward the research design, intervention, data collection, analyses,

and writing of the paper. S.K. contributed toward the intervention, data collection, and writing of the paper.

M.K.S., K.I.K., and Y.J. contributed toward the intervention, data collection, and writing of the paper.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the

Korea government (Reference number: NRF-2016R1A2B4007767).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design

of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the

decision to publish the results.

References

1. Choi, I.; Mo, S.; Lee, S. A Study on Mental Health Improvement Policy for Children and Adolescents II; National

Youth Policy Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2012.

2. Carson, V.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Gray, C.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Chaput, J.-P.; Saunders, T.J.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.;

Okely, A.D.; Connor Gorber, S.; et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in

school-aged children and youth: An update. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S240–S265. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

3. Son, J.W.; Ha, S.Y. Examining the influence of school forests on attitudes towards forest and aggression for

elementary school students. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2013, 17, 49–57.

4. Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press:

New York, NY, USA, 1989.

5. Corraliza, J.A.; Collado, S.; Bethelmy, L. Nature as a moderator of stress in urban children. Procedia-Soc.

Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 253–263. [CrossRef]

6. Korpela, K.; Kyttä, M.; Hartig, T. Restorative experience, self-regulation, and children’s place preferences.

J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 387–398. [CrossRef]

7. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of nature therapy: A review of the research in Japan.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 781. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

8. The National Law Information Center Forestry Culture and Recreation Act. Available online: http://www.

law.go.kr/main.html (accessed on 20 March 2017).

9. Howard, J. Integrating Outdoor Experience with Curricular Learning. Available online: https://www.wcmt.

org.uk/sites/default/files/report-documents/Howard%20J%20Repor%202015%20Final.pdf (accessed on

10 March 2017).

10. Muñoz, S.-A. Children in the Outdoors; Sustainable Development Research Centre: London, UK, 2009.

11. McCormick, R. Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: A systematic review.

J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 37, 3–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

10 of 11

12. Kim, S.A.; Joung, D.; Yeom, D.G.; Kim, G.; Park, B.J. The effects of forest activities on attitudes toward forest,

stress, self-esteem and mental health of children in community child centers. J. Korean Inst. For Recreat. 2015,

19, 51–58.

13. Kim, J.Y.; Shin, C.S.; Yeoun, P.S.; Yi, J.Y.; Kim, M.R.; Kim, J.K.; Yoo, Y.H. Forest healing program impact on the

mental health recovery of elementary school students. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2013, 17, 69–81. [CrossRef]

14. Choi, J.-H.; Kim, K.-E. Eating attitude of children using community child center: A structural equation

modeling approach. Adv. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2014, 47, 351–356.

15. Song, M.K.; Bang, K.-S. A systematic review of forest therapy programs for elementary school students.

Child Health Nurs. Res. 2017, 23, 300–311. [CrossRef]

16. Kang, K.; Kim, S. Health problems and related factors of socially vulnerable school-age children in Seoul.

J. Korean Soc. School Health 2017, 30, 181–193.

17. Taelman, J.; Vandeput, S.; Spaepen, A.; Van Huffel, S. Influence of Mental Stress on Heart Rate and Heart

Rate Variability. In Proceedings of the 4th European Conference of the International Federation for Medical

and Biological Engineering (IFMBE), Antwerp, Belgium, 23–27 November 2008; pp. 1366–1369.

18. Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015.

19. Han, E.; Yoo, A.-J. Children’s and adolescents’ depression, attributional style and academic achievement.

J. Korean Home Econ. Assoc. 1994, 32, 147–157.

20. Kim, Y.-J. Effects of Solution-Focused Brief Group Counseling Program on the Isolated Elementary School

Children’s Peer Relationship and Self-Esteem. Master’s Thesis, Korea National University of Education,

Cheongju, Korea, 2005.

21. Bahn, G.-H.; Shin, M.-S.; Cho, S.C.; Hong, K.-E. A preliminary study for the development of the assessment

scale for ADHD in adolescents: Reliability and validity for cass(s). Korean J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 12,

218–224.

22. Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4rd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013.

23. Gignac, G.E.; Szodorai, E.T. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personal. Individ.

Differ. 2016, 102, 74–78. [CrossRef]

24. Wolf, T.J.; Spiers, M.J.; Doherty, M.; Leary, E.V. The effect of self-management education following mild

stroke: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2017, 24, 345–352. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

25. Reed, K.; Wood, C.; Barton, J.; Pretty, J.N.; Cohen, D.; Sandercock, G.R. A repeated measures experiment of

green exercise to improve self-esteem in UK school children. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69176. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

26. Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health?

A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

27. Choi, S.-J.; Koh, Y.-S. Effect of combined program of horticultural therapy and forest therapy on self-esteem,

social competence, and life respect of low-income family children at community children’s center. J. School

Soc. Work 2014, 29, 671–699.

28. Cho, Y.M.; Shin, W.S.; Yeoun, P.S. The influence of forest experience program length on sociality and

psychology stability of children from low income families. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2011, 15, 97–103.

29. Kim, M.H. A study on the positive effects of forest activities for children from economically underprivileged

households on their emotional state, life satisfaction, and ego-resilience. Korean J. Child Stud. 2014, 35,

223–247. [CrossRef]

30. Wood, C.; Gladwell, V.; Barton, J. A repeated measures experiment of school playing environment to increase

physical activity and enhance self-esteem in UK school children. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108701. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

31. Karcher, M.J. The study of mentoring in the learning environment (SMILE): A randomized evaluation of the

effectiveness of school-based mentoring. Prev. Sci. 2008, 9, 99–113. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

32. Kim, N.S. Designing youth mentoring for disadvantaged family. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2011, 18, 355–380.

33. Rhodes, J.E. Stand by Me: The Risks and Rewards of Mentoring Today’s Youth; Harvard University Press:

Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009.

34. Yadav, V.; O’Reilly, M.; Karim, K. Secondary school transition: Does mentoring help ‘at-risk’ children?

Community Pract. 2010, 83, 24–28. [PubMed]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977

11 of 11

35. Duncan, M.J.; Clarke, N.D.; Birch, S.L.; Tallis, J.; Hankey, J.; Bryant, E.; Eyre, E.L. The effect of green exercise

on blood pressure, heart rate and mood state in primary school children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health

2014, 11, 3678–3688. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

36. Sharma-Brymer, V.; Bland, D. Bringing nature to schools to promote children’s physical activity. Sports Med.

2016, 46, 955–962. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

37. Lee, A.C.; Maheswaran, R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: A review of the evidence. J. Public

Health 2011, 33, 212–222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

38. Barton, J.; Sandercock, G.; Pretty, J.; Wood, C. The effect of playground-and nature-based playtime

interventions on physical activity and self-esteem in UK school children. Int. J. Environ. Health Res.

2015, 25, 196–206. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

39. O’Brien, L.; Murray, R. Forest School and its impacts on young children: Case studies in Britain. Urban For.

Urban Green. 2007, 6, 249–265. [CrossRef]

40. Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin books of Chapel

Hill: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008.

41. Tsunetsugu, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, B.-J.; Tyrväinen, L.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological

effects of viewing urban forest landscapes assessed by multiple measurements. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013,

113, 90–93. [CrossRef]

42. Bang, K.-S.; Lee, I.; Kim, S.; Lim, C.S.; Joh, H.-K.; Park, B.-J.; Song, M.K. The Effects of a Campus

Forest-Walking Program on Undergraduate and Graduate Students’ Physical and Psychological Health.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 728. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

43. Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku

(taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across

Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2009, 15, 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

44. Lee, I.; Choi, H.; Bang, K.-S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Lee, B. Effects of forest therapy on depressive symptoms

among adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 321. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

45. Cho, Y.M.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, H.E.; Lee, Y.J. A study on effect of forest related programs based on the

meta-analysis. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2015, 19, 1–13.

46. Akrimi, S.; Raynor, S.; Johnson, R.; Wylie, A. Evaluation of SHINE—Make every child count: A school-based

community intervention programme. J. Public Ment. Health 2008, 7, 7–17. [CrossRef]

47. Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards for Competence for Registered Nurses. Available

online: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/standards/nmc-standards-for-competence-

for-registered-nurses.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2017).

48. Kim, S.; Bang, K.-S.; Kang, K.; Song, M.K. Mentoring experience of nursing students participating in a health

promotion program for elementary school students. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2018, 24, 137–148.

49. Leventhal, K.S.; DeMaria, L.M.; Gillham, J.E.; Andrew, G.; Peabody, J.; Leventhal, S.M. A psychosocial

resilience curriculum provides the “missing piece” to boost adolescent physical health: A randomized

controlled trial of Girls First in India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 161, 37–46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

50. Rubenstein, L.M.; Hamilton, J.L.; Stange, J.P.; Flynn, M.; Abramson, L.Y.; Alloy, L.B. The cyclical nature of

depressed mood and future risk: Depression, rumination, and deficits in emotional clarity in adolescent

girls. J. Adolesc. 2015, 42, 68–76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

51. Han, K.-T. The effect of nature and physical activity on emotions and attention while engaging in green

exercise. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 24, 5–13. [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access

article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution

(CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).