THE EFFECT OF ECOSYSTEM CONSCIOUSNESS ON

OVERPOPULATION AWARENESS – A CASE STUDY

A dissertation presented to

the Faculty of Saybrook University

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Psychology

by

Susan H. Peacock

Oakland, California

February 2017

ProQuest Number: 10285148

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript

and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

ProQuest 10285148

Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author.

All rights reserved.

This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code

Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

ProQuest LLC.

789 East Eisenhower Parkway

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346

© 2017 by Susan H. Peacock

Approval of the Dissertation

THE EFFECT OF ECOSYSTEM CONSCIOUSNESS ON

OVERPOPULATION AWARENESS – A CASE STUDY

This dissertation by Susan H. Peacock has been approved by the committee members below,

who recommend it be accepted by the faculty of Saybrook University in partial fulfillment of

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology

Dissertation Committee:

______________________________

Alan G. Vaughan, Ph.D., J.D., Chair

______________________________

Robert McAndrews, Ph.D.

______________________________

Marc Pilisuk, Ph.D.

_______________________

Date

_______________________

Date

_______________________

Date

ii

Abstract

THE EFFECT OF ECOSYSTEM CONSCIOUSNESS ON

OVERPOPULATION AWARENESS – A CASE STUDY

Susan Henshaw Peacock

Saybrook University

The purpose of this research was to investigate how knowledge of biological ecosystems

affects individual recognition of humanity as part of and subject to the laws of nature. This

dissertation interrogated the question of how awareness of the impact of human overpopulation

on the environment was perceived by research participants. That expanding human population

growth, and its inherent consumption patterns, is a root cause of virtually every human-related

environmental threat is documented in the existing literature but awareness and accountability

for this remain limited. Using ecopsychology and analytical psychology as a theoretical

framework, this multiple case study investigated how and whether environmental awareness

might be impacted by personal knowledge of how ecosystems function in nature.

A multiple case study design was used to interview 10 adults on their perspectives of the

environmental impact of human population growth. The participants were purposefully selected

creating two five-person groups. Group S had life-science academic training and work

experience; Group NS had none. A researcher-generated instrument of 30 open-ended questions,

with recorded interviews were used to ascertain participant understanding of ecological laws and

iii

population biology concepts and how they might relate to personal worldviews on the cause(s) of

environmental issues.

Thematic analysis was used to code data and identify response patterns. Findings

suggested participants with working knowledge of ecosystems demonstrated more extensive

understanding of the impact of human actions, including population growth, on the environment.

Although widespread awareness existed in both groups that human alienation from nature is

prevalent and is having environmental consequences, Group S subjects more often recognized

the systemic environmental effects of human activity. They were inclined to advocate for

individual responsibility and consciousness-raising.

Support for core concepts of ecopsychology is suggested by the findings. Strengthening

the human-nature bond to one of inclusiveness using experiential education is a viable option to

promote greater ecological awareness and personal accountability. Additional data-driven

research is needed to investigate the effects of life science literacy and holistic systems thinking

on pro-environmental awareness.

iv

Acknowledgments

This dissertation journey was one requiring much effort and steadfastness, and it

represented a significant part in the fulfillment of a long-term personal dream – to bring my

education to a postdoctoral level on a subject that is very important to me. There are those who

helped and supported me along the way, and I want to express my appreciation to them here.

I would like to recognize and thank my chair, Alan Vaughan, and the committee

members, Bob McAndrews and Marc Pilisuk, for their guidance and support. They were

available and kind and offered both creative ideas and encouragement. I was fortunate to have

them as my committee. I also want to express my gratitude to the ten individuals who agreed to

be interviewed for this study. They shared their thoughts and feelings with me, and I was

continually amazed at their insights and wisdom.

My sister, Courtney Holmes, deserves my deep appreciation as well. She encouraged and

supported me throughout the process and did much more than her share of family responsibilities

so that I could concentrate on my studies. She is a thoughtful and caring individual, and our

bond is very special.

Finally, I wish to acknowledge my dear husband, Al, for his love and help over the last

40 years, especially during this journey. Sharing my passion for education, he was my

unrelenting cheerleader – always willing to listen, offer encouragement, insights, and

suggestions. He never let me get discouraged - using his great sense of humor and tough love to

keep me going. He supported my dream, as he always does, to help me grow as a person.

v

Table of Contents

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... viii

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1

Purpose............................................................................................................................................ 2

Background ..................................................................................................................................... 3

Rationale ......................................................................................................................................... 6

Research Question ......................................................................................................................... 6

Researcher....................................................................................................................................... 6

CHAPTER 2: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ......................................................................... 8

Overpopulation as an Environmental Issue .................................................................................... 8

Awareness of Overpopulation....................................................................................................... 27

Barriers to Awareness ................................................................................................................... 32

Knowledge Barriers ...................................................................................................................... 33

Social Barriers............................................................................................................................... 38

Individual and Psychological Barriers .......................................................................................... 43

Theoretical Models ....................................................................................................................... 52

Interventions: Past and Future ...................................................................................................... 52

Ecopsychology.............................................................................................................................. 53

Ecopsychological Perspectives on Ecological Threat................................................................... 60

Historical Perspective of Jung’s Interest in Overpopulation as an Environmental

Problem Found His Collective Works and Other Sources....................................................... 65

Post-Jungian Interest and Scholarship on Overpopulation and

Ecological Problems ................................................................................................................ 71

vi

Core Concepts in Analytical Theory and Jung’s Writing Important to

Ecological Study ....................................................................................................................... 74

Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 86

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................ 89

Research Method and Rationale ................................................................................................... 89

Participant Selection and Demographics ...................................................................................... 91

Data Collection Methods .............................................................................................................. 94

Data Analysis ................................................................................................................................ 94

Research Ethics ............................................................................................................................. 96

Limitations and Research Issues ................................................................................................... 97

Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 97

CHAPTER 4: FINDINGS ............................................................................................................ 98

Summary of Themes ..................................................................................................................... 98

Summary of Individual Findings .................................................................................................. 99

Case Study Profiles ..................................................................................................................... 101

Discussion of Individual Findings .............................................................................................. 115

Identified Patterns or Themes ..................................................................................................... 127

Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 129

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION...................................................................................................... 130

Findings in Context to Existing Literature.................................................................................. 130

Conclusions and Recommendations ........................................................................................... 134

Limitations and Delimitations..................................................................................................... 135

Researcher Reflections and Summary ........................................................................................ 136

vii

REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................... 138

APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................ 147

Appendix A. World Populations and Regions ............................................................................ 147

Appendix B. Top 20 Largest Countries by Population as of October 31, 2016 ......................... 148

Appendix C. World Population Growth J-curve......................................................................... 149

Appendix D. Study Participant Demographics ........................................................................... 150

Appendix E. Saybrook University Informed Consent Form ...................................................... 151

Appendix F. Interview Questions ............................................................................................... 153

Appendix G. Interview List of Environmental Issues ................................................................ 155

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Participant Sample Demographic Information ................................................................93

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1A: World Populations and Regions ............................................................................... 147

Figure 2A: Top 20 Largest Countries by Population as of October 31, 2016 ............................ 148

Figure 3A: World Population Growth J-curve............................................................................ 149

Figure 4A: Study Participant Demographics .............................................................................. 150

1

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

This research study is a result of my lifelong interest in the exquisite natural environment

that has served as a home and resource for us as a species throughout our history. Intuitively, I

have always sensed that the complexity and the endurance of life were possible when supported

by a balanced ecological system. It is through an infinite number of diverse small parts, each

performing but not exceeding its individual role, that the whole is maintained and able to

survive.

Although many species have fallen fate to the effects of damaging the system that

sustains them, humans seem to be unique in their ability to consciously consider their thoughts

and behaviors. From a distant perspective, the lack of a coherent effort on our part to live in

harmony with the rest of nature seems unimaginably short-sighted and completely

counterproductive to our survival. Despite many warnings along the way, ranging from cultural

myths to scientific data, that we are consuming and populating far beyond sustainability levels,

we have been largely unable to develop the awareness and make the changes needed to live as

integrated parts of a world system with ecological limits.

This project is also an outgrowth of the training and knowledge I have been grateful to

receive in the biological and behavioral sciences. It is through these lenses that I have developed

a worldview that sees life as an ecological tapestry in which all parts must be respected. I

believe using psychology in conjunction with ecology to realize ourselves as parts of, not

separate from, the natural world, can only help awaken us to a higher consciousness of who we

really are. Because I believe strongly in the principles of ecosystems as synonymous with the

principles of life, my interest was in beginning an investigation into how an understanding of

these principles might affect one’s perceptions of the environmental challenges we face.

Interviewing a small group of individuals trained and experienced in one of the biological

2

sciences, and a second group who was not, allowed me to consider the similarities and

differences this type of education might make.

This chapter begins with a statement of purpose for this multiple case study supported by

a description of relevant background information. The rationale for this research and the

resulting research question are presented as well. Researcher information and identified

limitations and delimitations are discussed. Subsequent chapters present an in-depth review of

the literature including definitions of key terms, a detailed description of the methodology and

design, findings of the study, and a concluding discussion.

Purpose

The purpose of this qualitative research is to explore how a worldview shaped by training

and experience in the biological life systems impacts awareness of overpopulation as an urgent

environmental concern. Despite the amplifying effect that rapid and doubling human population

growth has on virtually every human-related environmental threat, discussions on the subject

have been strikingly absent, both in public arenas and in academic literature.

Failure to address this even while solutions are within our grasp has been attributed to a

massive number of psychological and social barriers to awareness, not a lack of scientific

knowledge. Mainstream psychology with its almost exclusive focus on personality, and not on

person-in-environment, has been ineffective in offering a theoretical framework for study. As a

new subfield, ecopsychology takes a holistic perspective that understanding at a systemic level is

necessary to transform one’s perspective of the self and one’s place in the world (Merritt,

2012b). Ecopsychology shares core concepts with both analytic theory and ecosystem theory.

All of these view the world as a living system that relies on diversity and balance to maintain

3

resilience. If the parts of the system are not mutually beneficial in interdependent relationships,

the system will not be sustained.

This research investigates a sample of persons who have a background in understanding

how natural ecosystems work as well as a sample who do not have this background to determine

if these differing perspectives affect ability to comprehend the environment threats directly

related to a species whose consumption and proliferation patterns are seriously taxing the planet.

This could contribute to general knowledge about the effects of a living system perspective.

Secondly, ecopsychology is seeking to develop and refine its purpose, to move beyond its

countercultural, Romantic, and experiential beginnings into an academically focused psychology

with empirically-based research (Snell, Simmonds, & Webster, 2011). With its emphasis on the

more subjective aspects of human relationships with the natural environment, ecopsychology is

well suited to qualitative research and the scholarship of teaching This study aims to contribute

to these goals.

Background

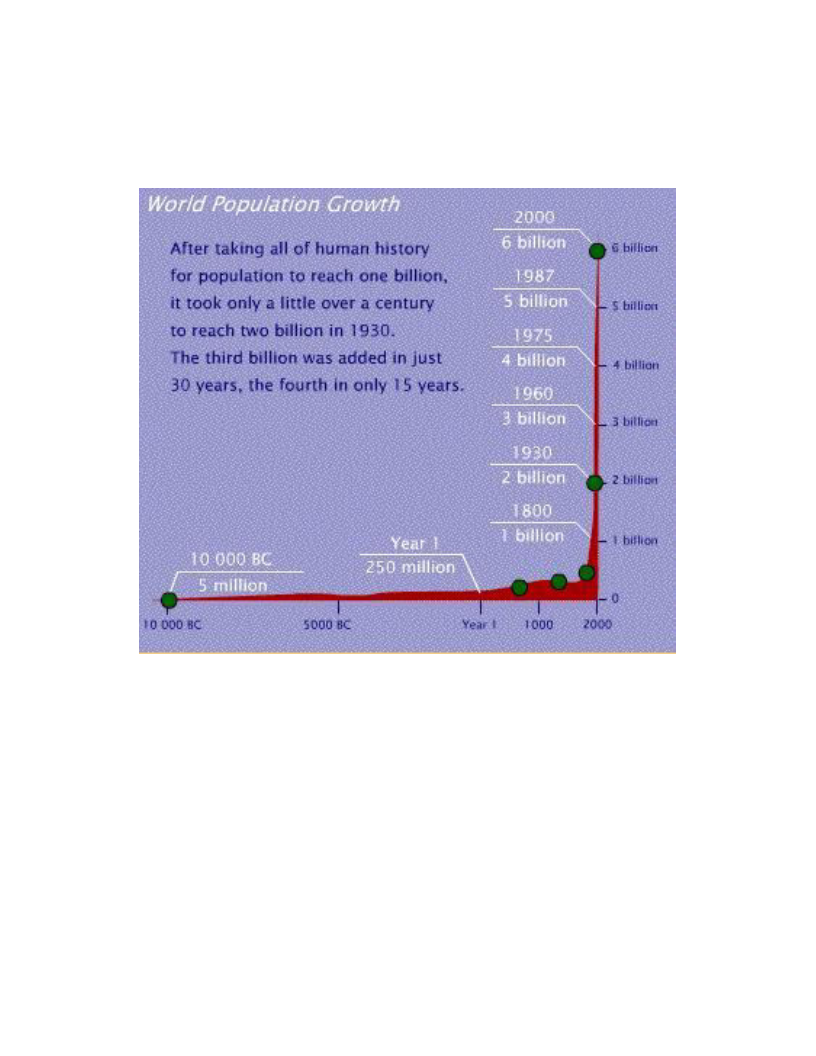

Anthropologists believe that the ancestors of Homo sapiens may have walked the Earth

as early as several million years ago while modern Homo sapiens may have appeared about

50,000 B.C. (Haub, 2011). According to the Population Reference Bureau (2015), world

population was around 5 million in 8000 B.C., the dawn of agriculture. In the 8,000-year period

until 1 A.D., world population grew slowly to 300 million people, reaching only 500 million by

1650 A.D. By 1800, however, after the start of the Industrial Revolution, living standards

changed and population numbers began to skyrocket, climbing from 760 million in 1750 to one

billion around 1800 (Haub, 2011).

4

Since that time, world population has grown explosively, especially in less developed

countries, doubling again and again. Due to the nature of exponential growth accelerated by

more changes leading to longer life spans and lower death rates, the world population has

exploded, with each addition of another billion people occurring in progressively shorter times.

A billion people were added between 1960 and 1975; a second billion between 1975 and 1987.

The current population of 7.4 billion has increased by a billion people just since 2004 and is

projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 A.D. (Population Reference Bureau, 2015).

In a landmark warning, more than 20 years ago, the Union of Concerned Scientists, an

international group of 1700 of the world’s leading scientists, many Nobel laureates in their fields,

issued a public statement entitled “The World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity” (Union of

Concerned Scientists, 1992). The report expressed their explicit concern that human beings were

on a collision course with the natural world and if many current human practices were not

fundamentally and urgently changed, the living world would be irreparably altered and unable to

sustain life in the world as we know it.

In addition to listing the atmosphere, water resources, oceans, soil, forests, and living

species as areas under critical stress, the warning statement identified the unrestrained world

population growth as an underlying cause in all of the world’s impending ecological disasters. In

their recommendations to humanity, the scientists urged the immediate stabilization of

population growth to prevent the catastrophic results of exceeding the earth’s finite limits (Union

of Concerned Scientists, 1992). Since that time, many other groups of scientists have issued

reports to try to bring attention to the mounting evidence that the world’s ecosystems are coming

under greater and greater stress.

5

Despite predictions about the dire effects of unrestrained growth on the world ecosystem

by Paul Ehrlich and others, the human population has continued to grow at an accelerated rate in

virtually every part of the world (Ehrlich, 2011). Tragically, after a brief time in the public arena

in the 1960s, the subject of overpopulation as an environmental concern all but disappeared from

the press and academia. It is theorized that the subject of overpopulation, as an easily

misunderstood and emotionally charged subject involving sex, reproduction, religion, culture,

human inequities, and freedom, is so sensitive and overwhelming that it is subject to being

ignored (Campbell, 2012).

There is a growing realization that the failure of any significant behavioral response to

the population crisis as well as other environmental issues has its roots in human emotional and

psychological factors, including political and economic ones (Metzner, 1999). In addition, many

writers in the field recognize that the efforts of mainstream psychology with its individualistic

and capitalistic perspectives have failed to suggest solutions for greater awareness and change.

What is especially ironic about overpopulation is that, unlike many of the issues that

confront us, solutions to this problem are already within our abilities. Martin Luther King (1966)

was a strong supporter of population control efforts and stated:

Unlike plagues of the dark ages or contemporary diseases we do not yet understand, the

modern plague of overpopulation is soluble by means we have already discovered and

with resources we possess. What is lacking is not sufficient knowledge of the solution

but universal consciousness of the gravity of the problem and education of the billions

who are its victims and the will to change. (Quotes)

Framed in Jungian core concepts and analytical theory, ecopsychology is uniquely

situated to offer help to humanity to move towards this universal consciousness. Ecopsychology,

as a developing field, focuses on resolving the alienation of humans from the nonhuman world

and even nature itself. Writers and psychologists in the field view re-education of humans to see

6

themselves as part of the world ecosystem, and therefore responsible to it and for it, as the only

viable way to produce transcending awareness.

Rationale

My rationale for conducting this study stemmed from my personal concern with what I

perceive to be an understudied and poorly understood source of environmental damage: human

population growth and its effect on the Earth’s ecosystems. Despite the efforts of the biological

sciences and the environmental psychologies, public consciousness and knowledge about the

impact of human-related activities on the environment remain low.

Ecopsychology, as an emerging field, takes its approach at a different level. Using a

foundation of analytical theory core concepts, ecopsychology focuses efforts on a conscious-

raising process where humans will see themselves as part of a larger world system, one to which

they are obligated and responsible. I believe the holistic concepts common to this discipline and

the ecological principles of ecosystems could be contributory to greater understanding of the

environmental issues. My rationale for this research was to determine how knowledge and

experience in the life sciences might affect awareness and understanding about human-related

environmental threat, especially human population growth.

Research Question

Based on my interest and rationale, my research question was formulated as follows:

How is awareness of human population growth as an underlying environmental threat affected

by understanding of the holistic principles of ecosystems?

Researcher

As is generally acknowledged in qualitative research, the skills and perspective of the

researcher affect the study in various ways (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Creswell, 2013; Robson,

7

2011). I would like to disclose my own background as it relates to the conduction of this study.

I have an undergraduate degree in biology and have had over 30 years of experience in

biologically-related fields. During these experiences, I acquired a thorough and working

knowledge of biological life systems and ecosystem functioning. In addition, I am a long-time

member of numerous ecology-related organizations and stay informed on current environmental

issues. I also have a master’s degree in social work and have practiced in this field for

approximately 10 years with a diverse client base. In this work, I learned interviewing techniques

and good listening skills. My present efforts in studying psychology reflect my interest in the

human psyche and soul. Each of the elements of this background offer something that I was able

to use in this work.

At the same time, I acknowledge that these same experiences could bias my judgment

regarding the questioning of interviewees and interpretation of findings. To address bias that I

might have, I tried to construct questions that were non-biased and asked the same questions to

two different groups of interviewees. In interpreting the results, I performed an extensive

analysis of responses that considered all responses, not just averages. Finally, I engaged in

critical self-reflection by journaling and discussing my approach with a colleague.

8

CHAPTER 2: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

In order to develop a rationale for this study, it was necessary to review the published

literature for what is known about the topic of human overpopulation as a global environmental

and social problem. The review examined the psychological literature to identify reasons for the

known gaps between knowledge of an ecological threat and failure to act in proenvironmental

ways. Literature studying the barriers to awareness of overpopulation as a common denominator

to many human-related ecological problems, and the reasons for scarcity of the subject as a topic

of discussion and research were also included as part of this review.

A review of the literature describing the course of ecopsychology as an evolving field

was also performed. Because of the incorporation of many analytical theory core concepts into

ecopsychology, Jungian and post-Jungian literature is an integral part of the literature. Holistic

principles common to both analytical thought and laws of ecosystems were identified.

Overpopulation as an Environmental Issue

Definitions

The term overpopulation, as it is generally used, refers to the situation occurring when

the needs of the group members living in an area that they depend on to provide essential

resources exceed that area’s ability to provide these resources and to replenish itself. There must

be a balance between the two entities for the system to remain in equilibrium and support the

population on a sustained basis.

In order to define human overpopulation, scientific attempts to quantify the impact of

human activities on the whole ecosystem have been made. Ecologists have developed the terms

ecological footprint and biocapacity to describe the two sides of the balance sheet (Global

Footprint Network, 2003). Biocapacity is the ability of earth areas to be biologically productive

9

as well as handle the waste generated. Areas that are barren, lack fresh water, stripped of

resources or built-up are not described as having this capacity. The ecological footprint of an

individual, a nation, or humanity is derived by comparing the demand that a species places on

nature’s resources to its ability to supply that demand. Measurements like this are inexact at best

and subject to criticism by those demanding exactness. However, in systems as complex as

human activities, trends are sometimes more important than precise measurements. The trends

of increased consumption by more people and the progressive depletion of resources are

undeniable. In one study examining data since 1961, Toth and Szigetti (2015) compared

population growth rates, gross domestic products (GDP), and ecological footprints (EF) of

different countries and the world and found that while world population tripled between 1950-

2006, GDP, as an indicator of consumption, increased nine-fold. In addition to monitoring the

individual and collective footprints, which are rightly focused on consumption, ecologists remind

us that the footprint of any individual can never be zero as every individual is a consumer.

Another term used in calculating human population and consumption impact is earth overshoot.

According to scientists at the Global Footprint Network (GFN) (2003), in the mid-1970s, a

critical threshold was crossed where human consumption began outstripping what the Earth

could provide. The overshoot model uses a budget analogy to illustrate the growing deficit of

our ecological spending and the data collected tells us that it would take 1.5 Earths to provide the

current level of demand for its resources and services. This deficit is maintained by liquidating

Earth’s resources. GFN (2003), representing 62 countries, calculated a calendar date each year

when humanity has used up the resources it takes the Earth a full year to regenerate. This date,

called Earth Overshoot Day, has moved from early October in 2000 to August 13th in 2015.

10

Global Demography and Trends

Although concern about overpopulation is ancient, for most of history human population

increases have always been kept in relative balance by corresponding death rates (Population

Reference Bureau, 2015). Beginning approximately in the 18th century, however, advances in

industrialization, agricultural technologies, and disease control have gradually lowered death

rates worldwide, while birth rates remained nearly the same overall. At the same time the

population was growing, resource consumption in industrialized nations began to skyrocket.

Population growth trends and demographic data are compiled by a number of

organizations. Data extracted from the recently published 2015 report, 2015 Revision of World

Population Prospects, are presented in a table format in Appendix A (Zlotnik, 2015). In this

report, the United Nations (U.N.) revised its future world population projections upward and

higher than previously predicted. Now, according to its projections, the current world population

of 7.3 billion is expected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030, 9.7 billion by 2050, and 11.2 billion by

2100. The table in Appendix A also shows the higher population densities occurring in the

developing countries and especially the least developed countries. These trends are expected to

continue while populations of developed countries expected to remain at a more consistent level.

A breakdown of population and population predictions by continent shows the greatest growth

rates continuing in Africa and Asia.

Population growth by countries is also tracked by world population organizations, often

with a live feed. Appendix B lists the 20 top largest countries by population growth.

(worldometers reference??) In 2015, China, India, and the United States were the world’s most

populous nations. Growth between 2015 and 2050 is expected to be most concentrated in nine

countries: India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, the

11

United States, Indonesia, and Uganda (Mirkin, 2014). China’s population growth rate is

predicted to slow, removing it from the list of fastest growing countries. The rapidly changing

positions of the most populous countries reflect the widespread nature of population growth.

The current U.N. report (as cited in Mirkin, 2014) represents a significant shift from its

previous reports on the issue of global population. Higher than expected growth prompted the

U.N. to alter its degree of concern and focus on human population growth as a primary

environmental concern. At the beginning of the new millennium, the U.N. released a list of

millennium development goals (MDGs) in September 2001. These were eight critical areas that

needed to be addressed by 2015; all of these targets were adopted by all 189 member states

(Redding, 2007). The MDGs included areas such as eliminating poverty, reducing child

mortality, and empowering women. Despite its integral relationship with the stated goals,

reducing population growth was not even mentioned as part of the agenda. Critics and analysts

of the MDGs speculated that feminist and human-rights factions centered on women’s rights

worked actively to prevent talk of stopping growth or reducing average family size (Foreman,

2012). Ironically, many feminists and social activists have served to undermine population

stabilization efforts by negatively associating it with reproductive health and ethical violations

(Weeden & Palomba, 2012).

The report also released data confirming the continuation of long-term global population

demographic trends. Although fertility rates are in decline in some developed countries, this is

most often off-set by a decrease in mortality, altering the balance between births and deaths that

is necessary for a population to stabilize. In these countries, those aged 60 or above are often the

fastest-growing demographic segment. In the least developed countries without basic services,

12

including family planning and women’s rights, there has been a larger than expected increase in

the number of unanticipated births.

Another continuing trend described in the U.N. report (as cited in Mirkin, 2014) is the

world’s increased urbanization. The more than half of the world population currently living in

urban areas is expected to rise to two-thirds by mid-century, most of which will be concentrated

in the poorer countries. In addition, the amount and patterns of immigration from less to more

stable countries are expected to increase as people are displaced or relocate. For example,

political upheavals in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia are reshaping migration trends in

Europe. Writing for the Council for Foreign Relations, Park (2015) stated that the International

Organization for Migration has estimated that more than 464,000 migrants and refugees have

crossed into Greece and Italy by sea in the first nine months of 2015, creating a crisis in the

social systems of the receiving countries. Due to the population numbers of the migrating

countries, this crisis is expected to continue without resolution.

In the report conclusion, the U.N. warned that these population dynamics will have

developmental consequences. Most of the direct consequences described such as provision of

housing, education, medical care, and food and water, involve inadequate or unequal resources

for larger numbers of people. More indirect consequences of the increased population trends

include effects to the labor force, human rights, immigration pressures, and failed government

states.

Overpopulation Impact

In the 2000 U.S. Geological Survey, released by the U.S. Department of the Interior,

geological scientists outlined 10 global challenges documented by research that had been directly

linked to human population activity (Groat, 2000). These included: inadequate and contaminated

13

water, hazardous weather, uncontrolled urban growth, emerging diseases, invasive species,

adverse climate change, exceeded natural material lifecycle, obsolete infrastructure, damaged

oceans, and poor air quality. The growth of global population was cited in this report as the

underlying cause impacting all these environmental threats.

Perception of the scope of population’s impact is affected by the false debate over

whether overpopulation or overconsumption is the real problem. Crist & Cafaro (2012) stated

the reality clearly, “The ecological crisis is the consequence of the consumption patterns of a

huge and growing human population” (p. 5). In a game of projection and blame, little attention

has been given to the fact that both the rich and the poor have different kinds of environmental

impact. One view contends that overconsumption in the global North is largely responsible for

the biosphere’s degradation, and certainly the destructive reach of high consumption patterns is

global in scope. The exclusive focus on this ideology masks the detrimental effects of

population growth itself, especially in the global South where population is growing most

rapidly. The destructive reach of the poor tends to be more local in its effect. Deforestation,

rampant extermination of animals, overgrazing, overfishing, unchecked pollution, and birth rates

are a few of the environmental issues related to mass numbers of people consuming (Crist &

Cafaro, 2012). While it is important to recognize and reduce consumption, it does not negate the

impact of population as a multiplier of consumption (Campbell, 2012).

The explosion of humanity’s numbers dramatically affects many other nonhuman species

as well. Recent quantitative research studies at Brown University concluded current extinction

rates are 1,000 times higher than natural background rates of extinction, and future rates are

likely to be 10,000 times higher (De Vos, Joppa, Gittleman, Stephens, & Pimm, 2015).

Environmental changes due to human actions are considered the major source of these patterns.

14

Endangered species biologist Wintrop Staples III is among those questioning the

anthropomorphic perspective of seeing the Earth as a resource only for humanity without

acknowledging other species’ right to exist (Staples & Cafaro, 2012).

Scientific Evidence

Most of the evidence that overpopulation exists is documented in the scientific literature

of the physical sciences. Research consistently supports the view that the world is overpopulated

and that humankind as a species has dangerously overconsumed natural resources to the extent

that other parts of the ecosystem are affected. In November 1992, a scientific statement from

1,700 of the world’s leading scientists, including many Nobel laureates, issued a landmark public

statement (World Scientists’ Warning) to humanity that the current course, if unchecked, places

the living world as we know it and the survival of human society and plant and animal kingdoms

at risk (Union of Concerned Scientists, 1992).

Since then, other groups of scientists have continued to try to deliver the message to the

world that the Earth’s ecosystems are being stressed to the point that a state shift is imminent.

State shifts are biological events that occur when ecological systems reach critical transitions

caused by threshold effects (Barnosky et al., 2012). In 2012, Barnosky and other integrative

biologists published another alert that these shifts are known to shift abruptly and irreversibly

and have global-scale impact. The scientists urgently suggest concentrating all efforts on the

true root causes of the mounting ecological crises: human population growth and consumption

rate.

Most recently, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) (2016) published their Living

Planet Report 2016 with the most comprehensive analysis to date on biodiversity loss. The data

indicates that the world is on track to lose two-thirds of its wild animals by 2020. According to

15

the report, this is part of a mass extinction of the natural world caused by the destruction of wild

habitats, hunting, and pollution related to population pressure. In the report, WWF Director

General Marco Lambertini (2016) spoke to this relationship when he stated:

The evidence has never been stronger and our understanding has never been clearer. Not

only are we able to track the exponential increase in human pressure and the constant

degradation of natural systems, but we also now better understand the interdependencies

of earth’s life support systems and their limits. Lose biodiversity and the natural world

including the life support systems as we know them will collapse. We depend on nature

for the air we breathe, water we drink, the food and materials we use and the economy we

rely on, and not least, for our health, inspiration and happiness. (p. 6)

Physicist Kuo (2012) has published more than 70 articles in international research

physics professional journals explaining why overpopulation is the source of other global

problems. In her field, she has explained that there is evidence to show that food and water

resources are already insufficient to meet the needs of the present global population of seven

billion. To illustrate the unsustainable path of resource usage, Kuo explained that, according to

the World Water Council, more than 11 million people have died from drought alone since 1900,

1.1 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, and more than one billion are going hungry

across the world today. These conditions are most pervasive in the countries where the

population is densest and resources are limited. Rapidly increasingly consumption by industrial

nations is an inseparable twin to the increasing population dilemma. As an energy systems

specialist, Kuo has explained that for a continuous growth system based on capitalism to

function, the system must use more and more energy and resources, continually expanding its

markets by persuading more and more customers that they need more and more products and

services. When this model is occurring in a bounded system, like the Earth, the growth cannot

grow indefinitely.

16

Evolutionary Trends

Evolutionary scientists have also studied the increase in human population growth. In

their research, Toth and Szigeti (2015) calculated humanity’s ecological footprint from 10,000

B.C. until 1960 using historical statistics to correlate growth rates using per capita GDP with

ecological footprint (EF). By all indicators, growth patterns have dominated not only since the

Industrial Revolution but also throughout humanity’s development. Interestingly, however, they

found that rates of growth and environmental degradation, although both trending upward, were

not always linear with population numbers. Asymmetric jumps and leaps in the GDP/EF ratio

during economic paradigms legitimizing growth, especially from the late 18th century, led the

researchers to conclude that population growth is a less important driver of EF than

consumption.

Offering another evolutionary perspective, Woolfson (1999) studied the past thousand

years of human development and believes that human worldviews have created the ecological

problems, and only changes in worldview can restore what has been lost. He concluded that

humankind is at an evolutionary crossroads for human survival and changes in societal world

views, value systems, and beliefs could likely lead to human long-term survival. Woolfson

noted that the emerging worldview must recognize and incorporate that man’s human nature is

both good and evil, man is the guardian of nature, man is motivated by self-interest as well as

altruism, man is a part of life, not separate from it, and earth’s resources are limited and finite.

Woolfson’s research does not address suggestions for changing world views.

Other researchers have proposed ways that human population growth and technology, in

addition to altering global ecology, is affecting future evolutionary trajectories. Evolutionary

change accelerated by human-induced growth patterns is being observed in other species around

17

us, especially disease organisms and pests. With the ability to evolve and mutate quickly,

bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms adapt to the use of drugs and chemicals in such a

way as to render the substances ineffective. The effects of this change can be seen economically

as well in exposure to uncontrollable outbreaks of pests or disease. Palumbi (2001) theorized

that larger numbers of humans, especially living in crowded conditions, are significantly

affecting the natural selection process of evolution. David Attenborough (2013), a naturalist and

wildlife commentator, has been harsh in his words for humanity’s oversized effect on other

species that have less ability to adapt, thereby affecting evolution: “We are a plague on the Earth

and either we limit population growth or the natural world will do it for us, and the natural world

is doing it for us right now” (p.1). Attenborough cited climate changes and drug-resistant

diseases as examples.

Other writers see the extinction of the human species as consistent with the laws of

nature. In her book, The Sixth Extinction, Kolbert (2014) described her work with eminent

scientists who are tracking humanity’s transformation of our globe. She described a clear pattern

of mass extinctions throughout the earth’s history where the diversity of life on earth suddenly

and dramatically contracted. Each time, massive weather or geological events triggered

extinctions that destroyed 60-70 percent or more of the living species. During the end-Permian

event, about 250 million years ago, more than 90 percent of marine, insect, and ancestors of

mammals perished through an inability to adapt to the changed conditions.

This time the catalyst for the mass extinction is the human race with its pollution,

predation, and habitat destruction, and scientists are already monitoring its course by rapid

extinction of other species (Kolbert, 2014). Though the present rate of biodiversity loss is far

below these numbers, scientists estimate the present extinction rate in the tropics to be about

18

10,000 times greater than the naturally occurring rate. If die-offs continue at this rate, some

scientists estimate the current extinction event could reach previous magnitudes in 240 to 540

years. In the case of the human species, Kolbert wrote, the path to extinction is fast-forwarded

by our restlessness, intellect, and appetites, but it is an inevitable path.

Political Influence

Anthropologists and archaeologists who have studied the success and failures of past

civilizations have contributed to the current study of overpopulation and overconsumption. The

evidence of what has happened to previous societies when presented with environmental

challenges can be instructive. In his book, Collapse, Diamond (2005) stated that when

civilizations fall, they share a sharp and sudden curve of decline. He found in his research that a

society’s demise may begin only a decade or two after it reaches its peak population and power.

He suggested the full-fledged collapses of the Anasazi and Cahokia in the United States, the

Maya cities in Central America, Moche and Tiwanaku societies in South America, Mycenean

Greece and Minoan Crete in Europe, Great Zimbabwe in Africa, Angkor Wat and the Harappan

Indus Valley cities in Asia, and Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean were due at least in part to a

fatal inability to deal with environmental crises. Diamond (2005) listed deforestation, soil and

water problems, overhunting and overfishing, human population growth, and increased per-

capita impact as some of the factors involved.

In many cases, Diamond (2005) believed the society’s demise was accelerated when the

leaders of these civilizations failed to practice long-term thinking and make courageous decisions

even after problems had become perceptible. When driven by personal interests over courage,

the leaders became more and more myopic and moved to crisis-management of small problems,

while simultaneously overlooking the larger picture until it was past the point of no return.

19

Other scientists in this field questioning the reasons for these collapsed societies have identified

resource overshoot by the population and demands by the elite that exceeded peasant tolerance or

capacity to produce (Tainter, 2006).

Political historians have observed the impact of overpopulation and overconsumption on

a society as well. Public policy researcher Goldstone (2006) noted that there are numerous

examples in history where increased crowding and lack of resources were the cause of

population-related conflict. The need for lebensraum or living space was a justification for

Adolf Hitler’s expansion campaign, which resonated with the growing and resource-deprived

German population. Japan, an island nation with high population density and limited resources,

adopted a strong history of imperialism, such as invading China and other parts of the Pacific, as

a result of its need for additional resources (Redding, 2007).

In recent years, the term fragile/failed states has been used by the World Bank and other

international organizations to describe those countries that lack the capacity or the will to deliver

core state functions (Redding, 2007). These states are said to have similar problems and

common among nearly all failed political states is high population growth. In 2007, the World

Bank listed 34 countries as fragile states with an average total fertility rate (TFR) of 5.1 percent.

Many such as Afghanistan, Angola, Burundi, Chad, D. R. Congo, and Sierra Leone have a TFR

of more than 6.5 percent. Fragile states also tend to have younger populations, and political

stability is at risk when population growth creates a spike in the number of young adults who

lack jobs and cannot meet their basic needs. Globalization has increasingly created a world

where stable countries are no longer isolated from unstable neighbors, and conflict can easily

spread across borders, threatening global security.

20

Foreman (2015) confronted some of the political issues that perpetuate population

problems in his book, Man Swarm. He believed, despite the far-ranging political ramifications

of overpopulation, it is a subject that many politicians avoid discussing. Politicians from both

sides of the political spectrum ignore overpopulation to pander to their bases, avoid cries of

discrimination by failing to consider immigration patterns, and retreat from ideas that certain

religious and cultural beliefs may be incongruous with our survival as a species.

Population itself can become a political issue. Governments may support higher birth

rates as a means of accessing more land, political power, or votes. Religious and cultural

institutions can also have an agenda in promoting more population growth in a world that is

already bursting at the seams. In his book, Countdown, Weisman (2013) stated, “Like Yasser

Arafat’s womb-weapon and the overbreeding of Israel’s haredim, the Church has a fundamental

vested interest in bodies” (p.133).

Economic Influence

The population dynamics of a single country can vary independently of global population

dynamics. A nation’s population size must also be considered in relation to its environmental

impact. Although the fertility rate in the United States is lower than many countries, the average

rate of 2.06 births per woman plus a high level of migration to the United States make it the third

most populous country in the world (Bish, 2012). What is perhaps more significant is the

excessive ecological footprint of America. Bish (2012) described the endless growth economy

that has been packaged and exported throughout the world by the United States. This brand of

capitalism relies on greater and continuous consumption and produces unsustainable amounts of

waste.

21

The capitalist economy is fueled by population growth. In order to maintain its existence,

production is dependent on the demand of more consumers needing more things and services to

be produced by more people involved in the production process. It is intrinsic to the

contemporary brand of capitalism to promote rapid population growth, both by increasing births

and encouraging immigration. Throughout the world, transnational corporate powers

subscribing to this economic system support that which promotes increased marketability.

Environmental and moral concerns for the earth and other people become collateral damage in

this pursuit.

Population Organizations

An increasing number of governmental and private non-governmental organizations

(NGOs) have come on-line to study and report on population issues. The U.S. Census Bureau is

a leading source of U.S. and international population statistics and research (U.S. Department of

the Census, 2015). Current and past population numbers are maintained along with breakdowns

into many demographically distinct characteristics. The site also posts population projections up

until 2050 based on historical trends. The United Nations (U.N.) global website has much less

extensive population data, possibly reflecting the degree of attention the organization gives to the

issue. It is telling that in September 2001, when the U.N. adopted its MDGs, outlining critical

areas to be addressed in the upcoming millennium, population growth was not included

(Redding, 2007).

The Population Institute (PI) is an example of a very active international non-profit

organization studying population. Their focus is on gender equality and family planning

promotion. The Institute conducts research on the known effects of overpopulation and writes

literature targeted towards increasing awareness in policy makers and journalists. By monitoring

22

trends, the researchers there have observed the ability of some countries to lower their rapidly

rising population growth. Tunisia, Egypt, Indonesia, and Mexico are some of the successful

countries that by implementing family planning as a routine part of health care have stabilized

their populations and seen increased stability and economic security as a result (Redding, 2007).

PI also corrects and revises earlier models as new data are received. For example, earlier

predictive models anticipating a decrease in African fertility rates have been discredited by a

large increase in the continent’s population (Fischetti, 2014). PI and others like it also report on

literacy rates, poverty levels, and maternal and infant mortality in countries with different rates

of population growth.

Other researchers use statistics for predictive purposes. With the population level

growing by 1.3 percent per year and industrial activity by 3 percent, Barter (2000) is a researcher

agreeing with World Bank projections for the future. He considered that, despite lower fertility

levels in a few countries, global human population will increase by another 50 percent in the next

40 years. Each nation is making its own contribution to the problem. Although birth rates in the

United States fell for several years, population growth now soars by three million a year, due

mainly to immigration and the higher birth rates of immigrants. All nations are increasing their

economic activity while China and India are joining the United States as the major industrial

polluters. If this path continues, Barter has predicted a catastrophic nuclear-age war will be

inevitable. He believes there is ample historical precedent that the politics of envy will continue

to grow among the have-nots, some of which have the means and the desire to destroy those who

have what they envy.

Leading conservationist and global visionary at the Rewilding Institute, Dave Foreman

(2015) cast a dim look at the effects to the world order that overpopulation of the human species

23

is having on Earth’s wildlife. He has taken a cautiously optimistic view that humans will be

resourceful enough to reverse this world order as more and more understanding develops.

Despite the unknowability of the future, I believe that the direr predictions and the historical data

based on trending are more likely than those requiring leaps of faith.

The United States

I want to devote a section of this chapter specifically on the United States to focus on its

unique problems. Though far from true for everyone, many people in the United States have

enough to eat and a place to live. Other than traffic and crowded stores, overpopulation seems

more like a concern for other countries. I have spoken with many people in this country who

respond to a question about overpopulation with a comment like, “A lot of third world countries

have that issue but it’s not something we have to worry about here.” The United States is unique

in its pattern of continued population growth. Demographically, the nation’s population has

grown from 76 million in 1900 to 325 million in 2014, making it the third most populous country

in the world after China and India. In 2000, 40 percent of that growth consisted of post-1900

immigrants and their descendants. (Population Reference Bureau, 2015).

Lindsey Grant, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Environment and

Population Affairs and a foreign-service officer to China, has written extensively about how the

population growth rate in the United States will drive its future. He explained that the United

States, being sparsely populated until well into the twentieth century, had more space to absorb

the damage of population and consumption (Grant, 1996). Looking at three vital areas, Grant

(1996) explained why the American position of confidence may be short-lived. Whereas U.S.

agriculture is still self-sufficient in meeting its own needs, its continued role as the residual

granary for the world for the near future is less assured. The amount of arable land per American

24

is on the decline, being lost to development; grain yields have been stagnant for more than a

decade requiring more chemical fertilization; top soil is being lost to erosion at a deficit; and

sustainable farming practices are unrewarded, favoring gross output of monocultures and

subsidies. U.S. supplies of water are diminishing with drought and greater use, especially in the

agricultural states of California and the plains (World Water Council, 2012). Finally, the United

States is the world’s major consumer of fossil fuels. Oil, gas, and coal are non-renewable energy

sources, and the government struggles to develop alternate and sustainable sources.

With an increasing population, U.S. society and its infrastructure are under increased

stress. The costs of needed infrastructure repair related to usage in this country are estimated to

be more than three trillion dollars (Grant, 1996). As urban areas grow, competition for housing

and services grow, and these conditions are frequently in decline. We console ourselves about

joblessness by watching the government’s unemployment rate but this number does not begin to

tell the whole story. This percentage measures only active job applicants, not the discouraged

job-seekers who have stopped looking. People who have become alienated or defeated may not

appear in the unemployment rolls but may appear on the crime rolls instead. The costs in ruined

lives are incalculable. Grant (1996) also observed that when the push for productivity is being

driven upward but demand does not meet supply, more people lose their jobs. This pattern

results in the familiar unstable economic pattern of the rich-getting-richer, the poor-getting-

poorer, and the middle class feeling increasingly strained.

Opposing Viewpoints on Overpopulation

There are, of course, opposing opinions not only on the risk of overpopulation itself but

on what should or can be done. The two major dissenting viewpoints that I found in the

literature were from (a) a religious perspective and (b) a technological perspective.

25

Austin Ruse is the president of the Center for Family and Human Rights, a research

organization dedicated to the defense of the family at international institutions, monitoring of

socially radical policies at the U.N., and fidelity to the teachings of the Catholic Church. Ruse

has written on a variety of social topics, including his belief that overpopulation is a myth. He

maintains there is plenty of food and resources for the world’s population and that the

overpopulation myth was created by those who would selectively promote one race over another

and coerce birth control or abortion. He has said that world population is in decline and the real

danger is in the aging of populations. Ruse has conducted no research of which I am aware but

has stated that his theory can be tested by looking outside an airplane window when one is

flying: “What you will see is a remarkably empty planet straining to be made a garden by more

of us” (as cited in Balkin, 2005, p.31). As a scientific observer, I am only able to assume that

these are the views of a person so enmeshed in his beliefs that objectivity is lost. Certainly, there

have been those who agree with overpopulation as a problem that have drawn erroneous

conclusions and proposed unethical solutions but the evidence is overwhelming that the

environment is being destroyed by the overburdening of its resources. Humans are unique in

many ways, but they do not defy the laws of nature.

The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a center-right pro-business think tank whose

research is dedicated to issues of government, politics, economics, and social welfare. One of

the AEI scholars, Nicholas Eberstadt (2007) shared his viewpoint by writing that scientific

discoveries and technological developments will allow human beings to solve the problem of

overpopulation. He denied that the idea of exceeding the Earth’s carrying capacity will be a

problem for humans because humans are unlike all other species and can use their problem-

solving techniques to escape the fates of other species. He selectively cited higher life

26

expectancies and lower infant mortality in some countries as his proof that this is true. Further,

he has said that fears about overpopulation have been disproven repeatedly in the past. He does

not mention what he means by disproven but he may be referring to more catastrophic

predictions.

As an example of human ingenuity and technological optimism being able to solve any

problems, Eberstadt (2007) referred to the Green Revolution where the development of new

wheat grains and agricultural practices like pesticides are said to have prevented one billion

people from starvation. A better perspective on this comes from Dr. Norman Borlaug, the actual

father of the Green Revolution. At the acceptance of his Nobel Prize in 1970, Borlaug stated,

“we are dealing with two opposing forces, the scientific power of food production and the

biologic power of human reproduction. There can be no permanent progress in the battle against

hunger until the [two forces] unite in a common effort” (as cited in Weisman, 2013, p. 57-58).

Borlaug further explained that his work had merely bought the world another generation or so to

solve the overpopulation problem. He maintained this perspective and served on the boards of

population organizations for the rest of his life.

A prominent conservative political writer, Wallace (2009) posted a blog for CentreRight,

a conservative British website, in response to the release of a United Kingdom public opinion

poll favoring a smaller world population. He denounced organizations that study population

growth and its effects as “having open contempt for human beings and advocating for the

removal of real human beings who live, love and laugh (para. 2). Wallace reported that people

are perfectly happy with the status quo and want to “continue breeding (para. 9). His views, as

well, are not based on any research.

27

Awareness of Overpopulation

History

Dating back to 1798, Thomas Malthus, British clergyman and intellectual, warned

society of the exponential growth of population that, if unchecked, he felt would inevitably result

in massive food shortages. Malthusian theory has been criticized and largely discredited by those

who believe his ideas were pessimistic and socially biased. Malthus was simply not aware of all

the impacting factors that would influence his predictions; however, his “Essay on the Principle

of Population” brought forward the connection between resource supply and population growth

(Brown, Gardner, & Halweil, 1999), and we have expanded our awareness of how a myriad of

resources such as water, forests, disease, and air quality are impacted by population growth.

Modern neo-Malthusians, like Paul Ehrlich and Thomas Keynes, based their ideas on the

theories of Thomas Malthus but expanded their beliefs to include other resources besides food as

being vulnerable to unabated population growth (What is the definition, 2016). The neo-

Malthusians are enthusiastic proponents of birth control.

Since the publication of Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, in 1962, scientists have

been documenting worsening threats to all aspects of the biosphere (Koger & Winter, 2010).

Population as an environmental stress has been considerably less discussed or even

acknowledged. In the 1960s and 1970s, after Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb was published,

increased attention was paid to the world’s rapidly growing human population. In 1960, global

population stood at three billion. By the end of the century, this number had doubled to six

billion and, if following the growth pattern of exponential growth, could double again later this

century. But in spite of this astronomical growth, media and policy attention all but disappeared

in the 1980s and 1990s. The silence on overpopulation was deafening and resulted both from

28

neglect and open hostility towards raising the issue. Population and the need to control its

growth touch every sensitive human subject. Sex, reproduction, culture, religion, morality, and

global inequities are just a few of the areas that contribute to its controversial nature and why

awareness about it is so compromised.

In 1993 in New Delphi, a summit of representatives from the world’s scientific

academies met and concluded that humanity was reaching a crisis point of irreversible

degradation of the natural environment if zero population growth were not reached within the

lifetime of the children currently living. The following year, the International Conference on

Population and Development (ICPD) met to discuss related issues but was sidetracked into

alternate agendas and did not even address overpopulation (Weeden & Palomba 2012).

Family planning funding was recommended by both groups but has not kept up with the

need. The proposed 2005 budget of $5.2 billion to be collected from developing country and

developed country donors yielded $0.5 billion instead. As always, poorest families suffer most.

In 1998, the African rich found ways to limit family size but the fertility rate of the poor

remained unchanged at 20 percent, with an increase of unwanted pregnancies rising from 11

percent to 21 percent (Potts, 2007). The population of 870 million in sub-Saharan Africa is

expected to grow to 1.8 billion in the next 39 years (Ehrlich, 2011).

Population Silence

Population has a long history of being notably absent from the discussion table of

environmental threats. Using a random sample of 150 articles on urban sprawl, water shortages,

and endangered species, Maher (1997) showed that only about one in 10 articles framed

population growth as an ecological stressor and source of the problem. Further, only one story

mentioned stabilizing population among the realm of possible solutions. The discussion of

29

population growth also seemed to be missing from concern about housing prices, energy

shortages, and oil exploration efforts and other topics related to the law of supply-and-demand.

Behind the taboo of discussing overpopulation, sensitive factors, such as race, birth control,

religion, and individual freedom, have been identified (Campbell, 2012).

For example, most Americans do not want to feel that they are prejudiced against people

of another race and because a global overpopulation discussion invariably includes the subject of

race, the discussion is avoided. The fact is that birthrates have little to do with race and rather

reflect economic opportunity, shortage of resources, and loss of land but, nevertheless, this topic

is also avoided. Currently, immigration to the United States is the highest in its history – 1.5

million per year or 44 percent of the annual growth rate. The United States is already

overcrowded with diminishing resources, and this level of immigration cannot help but diminish

the standard of living for all. In fact, it is more often the affluent and educated persons of other

countries who are capable of immigrating to the United States. This leaves those in the country

of origin still struggling with their problems while creating a brain and resource drain that makes

matters worse. Many Americans want to avoid this discussion, too, as it interferes with their

cultural perception of America as open and fair to all.

The sensitive topic of birth control also contributes to the silence on overpopulation.

Many religious Americans perceive using birth control as an act against the word of God. Others

equate discussing the freedom to use birth control as synonymous with abortion. One of the

world’s largest religions, the Catholic Church, has played a substantial role in perpetrating the

silence on overpopulation.

The first mission of virtually every population organization is to aid in the prevention of

pregnancies, not in their termination, but this is not distinguishable to some people. Nothing in

30

the Bible specifically prohibits birth control and preventing pregnancies, rather than their

termination, is the first mission of virtually every active population organization. For some, the

Biblical statement attributed to God to “go forth and multiply” is often quoted as divine intent

that humans should multiply without reserve. This is placing the statement out of context

because this phrase was a standard greeting of the time to wish others abundance. It also fails to

take into account the many statements present in the Bible that direct man to care for the earth

and all its inhabitants.

Discussing overpopulation also touches on concern about the loss of personal freedoms.

Fears of coercive population control are triggered with memories of dark events in our history

when population control efforts were selectively based on certain populations. These were tragic

abuses of power assuming the form of concern for overpopulation. In 1979, China imposed a

political decision on families to limit reproduction to one child without addressing related

individual health and women’s issues. As with many politically-mandated decisions, there have

been many unforeseen consequences such as demographic imbalances, violence, and female

infanticide. Many studies have shown that when people have better education and control over

their lives, they tend to have fewer children voluntarily which is ethically sound (Guttmacher

Institute, 2015). It is also a legitimate perspective to consider that personal freedoms can be

seriously curtailed under conditions of greater population density.

Campbell (2012) has studied the history of population growth in the last 200 years and

what she has identified as the reasons for the silence is creating what she calls the perfect storm

for public inattention. First is the visibility of birth rate declines in some countries. Since

increased survival rates have driven growth far more than higher fertility rates, the current

declines are of minimal consequence in the total picture. Another factor for a lack of public

31

awareness on overpopulation is focus on the patterns of overconsumption, a more visible factor.

While it is important to recognize and reduce consumption, it does not negate the impact of

population as a multiplier of consumption. For example, the waters of the Nile River are

becoming seriously depleted; this is due to the booming population growth in the countries

surrounding it. Thirdly, anti-abortion activists, religious leaders, and conservative think tanks

have been actively diverting attention from population growth as a problem. Campbell believed

that the AIDS epidemic and other urgent threats also reduced attention on the need to reduce

births and provide family planning.

Many feel that the turning point in removing the subject of population from policy

discourse was the 1994 United Nations International Conference on Population and

Development in Cairo. The strategy adopted at Cairo to focus on women’s reproductive health

counterproductively associated family planning with government-driven coercive population

control and avoided drawing any attention to environmental destruction. This position

effectively destroyed any meaningful global discussion on the empowerment of women to reduce

fertility by choice. The opportunity to understand family planning as a means of liberating

women from domestic and cultural coercion and a means to escape poverty, prevent death from

unintended pregnancies and induced abortions, and strengthen their own and their children’s

well-being, was lost (Campbell, 2012).

Psychology’s Role in Raising Awareness

In many ways, our environmental problems, including overpopulation, are human

behavior problems (Takács-Sánta, 2007). The role of science is to observe and describe the

natural events that are occurring. Substantial scientific evidence has been collected and

distributed. But we know that information only serves a purpose if it is heard and used, and there

32

is even more evidence that the public is not hearing this message and using it for behavior

change. Working as an anthropologist in water resource management, Anderson (2001) believed

that environmentalists often focus exclusively on economic self-interest as the only human factor

involved in retarding pro-environmental behavior. Because humans are as much moved by

emotion and mood as reason and frequently distort information in predictable ways, Anderson

stated that environmentalists need all the help possible from psychologists.