International Journal of

Environmental Research

and Public Health

Article

Six-Step Model of Nature-Based Therapy Process

Kyung Hee Oh 1 , Won Sop Shin 1 , Tae Gyu Khil 1 and Dong Jun Kim 2,*

1 Department of Forest Therapy, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Chungbuk 28644, Korea;

okh7864@hanmail.net (K.H.O.); shinwon@chungbuk.ac.kr (W.S.S.); ktg0704@hanmail.net (T.G.K.)

2 Department of Forest Science, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Chungbuk 28644, Korea

* Correspondence: kdj63@chungbuk.ac.kr; Tel.: +82-43-261-2532

Received: 5 December 2019; Accepted: 18 January 2020; Published: 21 January 2020

Abstract: Several studies have confirmed that the natural environment has psychophysiological

healing effects. However, few studies have investigated the healing process involved in the effect

of the natural environment. To date, no theoretical model on the nature-based therapy process

has been clearly established. Thus, the aim of this study was to develop a theoretical model of

the nature-based therapy process by analyzing individual empirical data. Research materials were

180 self-reported essays on “Forest Therapy Experiences” submitted to the Korea Forest Service.

This study was conducted based on grounded theory. Data were analyzed through open coding.

A total of 82 concepts, 21 subcategories, and six categories were derived. Results revealed that

the nature-based therapy process contained six categories: Stimulation, acceptance, purification,

insight, recharging, and change. When in the natural environment, participants first experienced

positive emotional change, followed by cognitive and behavioral changes. Based on these results,

a nature-based therapy process model was derived. This study revealed that the nature-based therapy

process did not consist of just a single element or step, but involved an integrated way of healing

with emotional and cognitive changes. This study is significant in that it derives a theoretical model

of the nature-based therapy process with comprehensive mechanisms. Further research is needed to

establish more systematic theoretical model.

Keywords: natural environment; forest therapy; theoretical model; stress; public health

1. Introduction

Modern people are exposed to various problems and diseases due to rapid social and lifestyle

changes. In particular, stress is a major threat to the quality of life and health. It is strongly associated

with psychological and physical diseases [1]. Stress is caused by the stimulus of any object or situation

we encounter [2].

When the body is exposed to external stimuli, the brain recognizes them as threats and activates

the autonomic nervous system inducing a “flight-or-fight” response [3]. Stress can be divided into

distress and eustress [4]. Moderate stress in daily life plays a positive role by providing energy,

stimulation, and motivation in life. Hormones associated with stress can protect the body in the

short-run and promote adaptation. However, if stress hormones are built up in the body without being

released, they can lead to chronic stress which might destroy the immune system and cause various

ailments [3]. Stress that continues for a prolonged period has negative effects on health [3,5].

Responses to stress and coping strategies vary from person to person [6]. Failure to cope with

negative and chronic stress can lead to mental and physical illnesses [7] including mental disorders

(such as depression) and physical disorders (such as angina).

Relieving stress has emerged as an important issue to improve health and quality of life. Interest in

nature-based therapy is increasing because having contact with nature can relieve stress with a positive

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685; doi:10.3390/ijerph17030685

www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

2 of 16

psychophysiological effect. Many studies have reported the positive effect of natural environments.

There are several major theories related to nature-based therapy. Ulrich’s psycho-evolution theory

(PET) [8] and Kaplan & Kaplan’s attention restoration theory (ART) [9] are two core theoretical models

on nature’s ability to relieve stress in humans. Ulrich et al. [8] have suggested that humans have evolved

psychologically and physiologically so that they can function well in the natural environment. Thus,

humans can relieve their stress much faster when they are in nature rather than in cities. According to

the ART [9], the natural environment can rapidly recover human attention by restoring and renewing

the capacity depleted by fatigue and stress. Continued attention and fatigue can degrade our ability

to solve problems and cause various negative emotions. Kaplan & Kaplan [9] have suggested that

the natural environment can resolve health problems of modern people’s daily lives caused by stress

and fatigue.

These two theories are related to Wilson’s ‘biophilia’ hypothesis [10]. ‘Biophilia’ means ‘love for

life’. The hypothesis assumes that humans have attachments to nature with a nature-returning instinct

because humans have lived in nature for a long time. In other words, since the physiological function

of human beings is suited to nature, they can instinctively feel relaxed and bonded when they have

contact with nature. Thus, stress may be reduced, leading to positive psycho-physiological responses.

The ‘topophilia’ hypothesis expands the idea beyond the ‘biophilia’ hypothesis [11]. ‘Topophilia’

means ‘love for places’ formed by experiences. This means that humans can form an affiliation with

the natural environment through acquired learning. This hypothesis explains human interests and

positive feelings about nonliving components (such as water and stones) and living elements in the

biophilia hypothesis.

Many studies support these nature recovery theories in various ways. Ulrich [12] compared

the number of hospital stays, patient records, and analgesic doses from 1972 to 1982 at a hospital

in Pennsylvania for patients undergoing operations. He assigned patients to two different groups:

A group with window view rooms where patients could see trees and another group with windows

facing a brick wall. Results showed that the group with a tree view through the window had fewer

days of hospitalization and took less analgesic than the group with a brick wall view, indicating that a

view of the natural environment could influence the postoperative recovery of patients.

Hartig et al. [13] conducted a comparative study on stress levels and attention recovery with

112 adults in natural and urban surroundings by repeatedly measuring subjects’ blood pressure

and emotional factors to test how human restoration values are associated with nature and urban

environments. They found that walking in a natural environment could reduce negative emotions,

increase positive emotions, and improve work performance. Shin [14] has examined how the forest

around the workplace affects job satisfaction and stress of workers. Results showed that workers

with a forest around their workplace had higher job satisfaction with lower levels of stress and lower

turnover rates than those without forest surroundings.

Validation studies about the physiological effect of forest baths have been actively conducted

in Japan. Park et al. [15] assigned 280 subjects in their twenties to 12 groups and had them walk

around forests and urban areas. Their cortisol levels, blood pressures, pulses, and heart rates were

then measured. Their results showed that forests lowered cortisol concentration, pulse rate, and blood

pressure, suppressed sympathetic nerves, and activated parasympathetic nerves compared to urban

surroundings. Li [16] has investigated the effects of forest bathing on human immune function.

After male and female subjects traveled in the forest for two nights and three days, their blood and

urine samples were collected on the second and third day during the trip and at seven and 30 days

after the trip. Results showed that the number of NK (Natural Killer) cells was significantly higher

than usual while cortisol concentrations were lower than those from their usual daily life for both

men and women. The increase in NK cells lasted up to 30 days after the trip, confirming that forest

bathing could lead to the maintenance of high levels of NK cell activity. Morita et al. [17] measured

and compared the effects of forest baths on 498 participants. They reported decreases in hostility and

depression with increases in vitality when they visited the forest, suggesting that forests might be

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

3 of 16

particularly effective in reducing chronic stress and acute emotions and that forest baths could help

reduce the risk of diseases associated with psychosocial stress.

Studies on stress and cognitive recovery in natural environments have also been performed in

various ways. Tryvainen et al. [18] surveyed 77 participants about their recovery after visiting urban

buildings, urban parks, and urban forests in Helsinki. They reported that visiting urban forests had a

positive effect on stress relief and cognitive recovery as compared to visiting a man-made environment.

Hansman [19] assessed the recovery effect of urban forests and urban parks in Zurich, Switzerland.

The results revealed that suffering from headaches and stress decreased significantly while feelings of

being well-balanced increased significantly. The recovery ratio for stress was 87% and the reduction

ratio for headaches was 52%.

These findings confirmed that a green environment could promote health and recovery in humans.

In addition, activities in a natural environment can significantly improve self-esteem and reduce overall

negative feelings [20]. Kuo & Sullivan [21] have reported that people living in desolate buildings

of an inner city have higher mental fatigue, aggression, and violence than residents living in rural

areas. Their results indicated that having contact with nature could reduce mental fatigue and mitigate

aggression and violence. Kuo [22] has found that residents without a natural environment tend to be

lazier and regard problems more seriously than residents with a natural environment. In addition,

the natural environment can reduce mental fatigue in residents, improve their efficiency, and enhance

their problem-solving abilities in everyday life [22].

It has also been reported that green environments have positive effects on cognitive abilities of

children. Wells [23] investigated the relationship between the natural environment and the cognitive

functions of children from families with low-incomes in urban areas and reported that cognitive

function can be improved to a high level after children move to a house with a green environment.

In addition, forests can affect spiritual aspects and enhance well-being [24]. Previous studies

have also reported that forests can provide an experience of transcendent moments [25]. Mackerron &

Mourato [26] have used GPS to study the relationship between subjective well-being and personal

environment and found that participants are happier in a green or natural living environment than

in an urban environment, further emphasizing the relationship between the natural environment

and happiness.

Previous studies [13–26] have shown that having contact with nature is psychologically and

physiologically effective in relieving stress, reducing depression and negative emotions, and increasing

positive emotions. Nature also has a cognitive recovery effect. It can improve concentration and

daily problem-solving abilities. Recovery in nature is cumulative. The more it is repeated and the

greater the number of visits to a green space, the less likely the incidence of stress-related diseases [27].

The higher the ratio of greenery and access to greenery, the greater the physical health and mental

well-being [28–31] and the less the health disparity caused by income differences [32].

These results suggest that the natural environment has positive effects on public health, indicating

that nature-based therapy can be utilized as a strategy to prevent diseases. Despite these positive effects

of the natural environment, it is currently unclear why and how recovery occurs in nature. Previous

studies were mostly effect-oriented. Only a few studies have determined how physiological, mental,

and social changes proceed in natural environments. To date, there is no theoretical model to explain

the nature-based therapy process. For nature-based therapy to be recognized and further developed for

use in the field of public health, it is necessary to develop theoretical models of nature-based therapy

processes and mechanisms. Thus, the aim of this study was to develop a theoretical model of the

nature-based therapy process by analyzing empirical data.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

4 of 16

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Data collected for this study were 180 self-reported essays entitled “forest therapy experiences”

that were submitted to the Korea Forest Service from 2014 to 2015. The Korea Forest Service has

hosted an annual public essay contest on forest therapy experiences in order to promote and draw

public attention to the importance of forests and natural recovery effects. Topics of essays used in

this study were all related to forest therapy, such as overcoming diseases (cancer, depression, etc.),

recovering from various addictions, and resolving family problems. Those without an experience

of natural recovery effects were excluded. The text format was free prose which was about 3–4 A4

sheets in length. The Korea Forest Service stated that “all submitted essays will not be returned and

may be used for public interest.” Among these works submitted, excellent ones were selected and

published in a book. Data used for this study were not raw data. They were edited and compiled.

The 180 essays collected were reconstructed with all personal information (national resident numbers,

names, phone numbers, etc.) removed and assigned serial numbers. Therefore, data of this study did

not include any information disclosing personal identity. Essays cited were taken from those already

published in a book from 2014 to 2015. This study did not directly observe or interview individuals.

Their essays used in this research were open to the public. All personal information was removed

during the editing process. In principle, the use of materials that are open to the public does not require

Institutional Review Board (IRB) review. Therefore, this study was not reviewed by the Institutional

Review Board (IRB).

2.2. Composition and Contents of Study Data

Study data were composed of stories of experience of individuals who visited the natural

environment on their own and experienced a recovery. Participants described their own natural

recovery experience in a free format. Data included information about what participants felt and how

they were moved when they first visited the natural environment, where they visited, main symptoms,

causes of stress, changes in body and mind, and the healing process. In addition, these essays

specifically described motives for changing one’s perspectives and thoughts while subjects were in the

natural environment, the state of psychological change, and changes in life and values after the recovery.

This study identified some patterns and common phenomena in the healing process. These patterns

and phenomena were then developed into concepts that could infer the nature-based therapy process.

2.3. Methods

Because nature-based therapy proceeds through a very complex mechanism, existing quantitative

research methodologies alone are limited in developing a theory encompassing multiple aspects of

the nature-based therapy process. To develop a theory on the nature-based therapy process, there

should be sufficient investigations on nature-based therapy phenomena. Therefore, qualitative studies

are needed to complement quantitative studies. The research method was based on the grounded

theory of Strauss & Corbin [33], a qualitative methodology. Grounded theory is a systematic way of

developing a theory from empirical data [33]. The analysis was carried out in four stages of open

coding with one forest therapy consultant and one qualitative researcher to eliminate possible biases

from researchers and increase the objectivity (Table 1).

Table 1. Four stages of the open coding process.

Coding Stage

Open coding

Analysis Process

1st analysis

2nd analysis

3rd analysis

4th analysis

Contents

Derive overall feeling and experiences

Coding

Derive a concept

Derive subcategory, category

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

5 of 16

The sequence of analysis was as follows. First, the overall feeling and perceptions of healing

experiences were derived by repeatedly reading the data. Second, using line-by-line analysis,

each sentence was read line-by-line. In each case, all sentences containing words or contents related

to mental, physiological, social, and relational recovery were coded. Third, focusing on recurring

themes of recovery, concepts were derived by grouping similar themes. “Theme” was found according

to contents of recovery. “Concepts” were obtained by extracting and combining common themes

from experiences related to recovery. Fourth, by continuous comparing, concepts, subcategories,

and categories were derived. These concepts, subcategories, and categories derived from open coding

were restructured according to the flow and order of time.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Individuals

As a result of analysis, ages of those who experienced nature-based therapy ranged from teenagers

to the elderly in their 80s. There were 77 men, 83 women, and 20 miscellaneous cases in which the

gender was not identified or classified as other. These participants had various mental, physiological,

and social symptoms (stress, depression, cancer, recovering patient, metabolic diseases, neurosis,

addiction, rare and intractable disorder, interpersonal conflict, suicidal ideation, cognitive impairment,

etc.). Among these symptoms, depression and stress coexisted the most (102 cases).

3.2. Place and Type of the Experience

Forests and parks near the place of residence were the most commonly experienced place (67.6%),

followed by recreational forests, arboretums, close mountains, and remote mountain life. In this

study, the park was a wooded forest and the arboretum was a national forest designed for forest

healing. Remote mountain life meant that participants with diseases lived in deep mountains to recover.

The duration of the recovery experience in the natural environment differed by disease and individual.

In some cases, participants experienced a healing effect with just one visit. In others, participants

experienced recovery with multiple visits over a long term.

It was difficult to accurately analyze the number and the duration of the visit to the natural

environment. Data on the frequency of visits included daily visits, two to three times a week, irregular

visits, and regular visits for more than 20 years. Experiences in the natural environment included

walking, staying in a quiet place and resting, forest bathing, talking with trees, observing trees, hiking,

observing animals and plants, and contemplation and meditation. As for the motivation for the visit,

individuals with cancer or atopic dermatitis mentioned that they actively visit forests for the purpose

of a cure. However, most people visited natural environments by chance or simply visited forests and

parks just because they were near their homes. Once they had a positive experience, they visited the

natural environment more actively. In particular, those who lived close to forests visited forests more

frequently (almost daily) and continuously. Results indicate that frequent trips to parks or forests near

one’s home are more effective for health promotion than occasional trips to distant mountains.

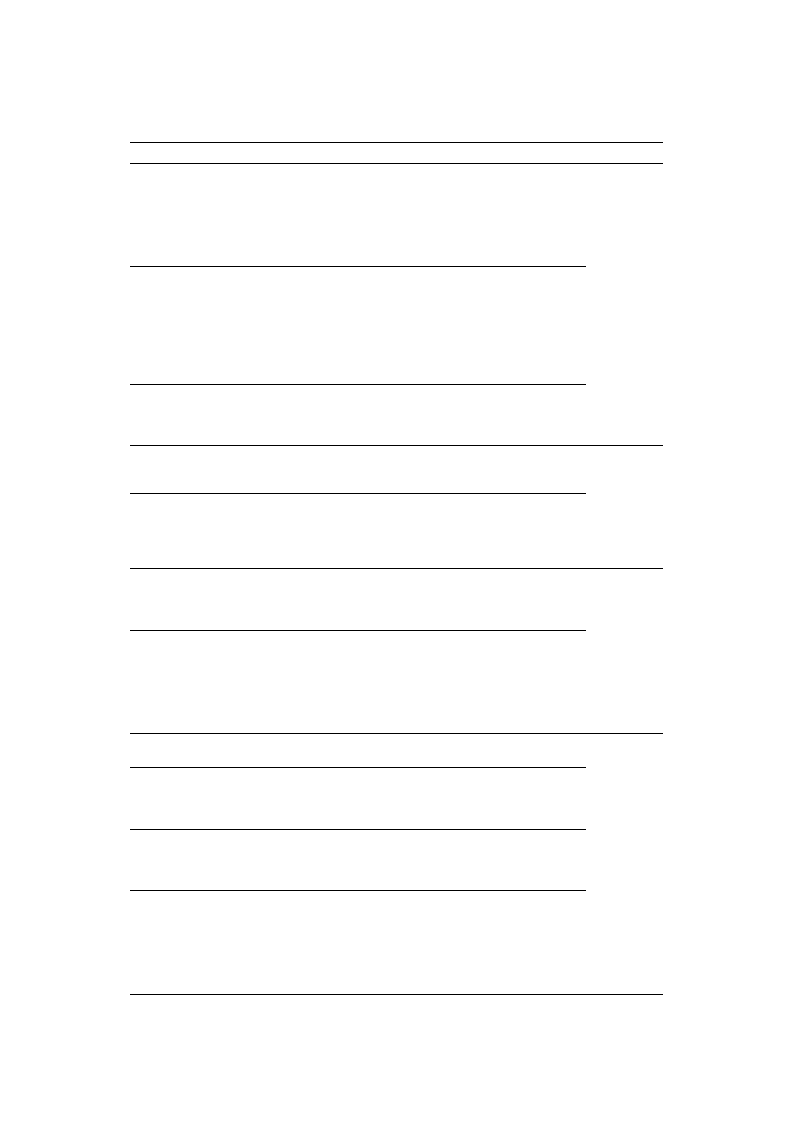

3.3. Derivation of Concepts and Categories

Through open coding, 82 concepts, 21 subcategories, and six categories were derived (Table 2).

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

6 of 16

Table 2. Concepts and categories.

Concept

Feeling better

Happiness

Enchantment, feeling beauty

Fluttering, delight, fascination

Joy and pleasure

Feeling moved, impressed

Awe, mystery, novelty

Cool and refreshing mood

Stress relief

Headache disappears and clear head

Fatigue disappears

Feeling of clear body and mind

Deep sleep

Feeling peace

Physical changes

Curiosity, interest, and attention begin to develop

Feeling alive

Emotion has been rich and survives

Feeling freedom and liberation

Unconditional acceptance and welcome

Embrace and hug

Feeling of peace of mind and comfort

Healing of wounds

Consolation and serenity

Become a friend and companion

Just listen silently and encourage

Open mind

Releasing anger

Reveal innermost feelings

Have honest conversation

Tears come out

Emptying and washing mind

Hate and resentment disappear

Releasing greed

Less worry and concern

Generous heart

Distraction disappears

Lightened mind

Deep reflection and meditation

Concentration occurs

Looking back on one’s life

Reflection occurs

Enlightenment as to the cause and solution of the

problem

Realizing life’s wisdom and reason from the

providence of nature

Learn lessons from the survival strategies for plants

and animals

Search for one’s inner self

True meeting with oneself

Have an inner conversation with oneself, including

dreams

Know one’s preciousness

Restoration of self-confidence and self-esteem

Finding real self

Subcategory

Positive emotions

Change of mind and body

Recovery of emotions and senses

Peace of mind

Consolation and empathy

Eject suppressed feelings and

emotions

Relieve negative emotions

Reflection and meditation

Self-awareness and reflection

Realizing the wisdom of life

Identity recovery

Category

Stimulation

Acceptance

Purification

Insight

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

7 of 16

Table 2. Cont.

Concept

Recognize and accept reality and limitations

Accept pain as part of life

Finding the meaning of life

Finding meaning in pain

New interpretations of life

Increase love and understanding of others

Recognize and accept children as independent

beings

Have a forgiving heart

Control over life

Rise from the past

Willingness to change and choice for new life

Determined to overcome difficulties

Have good ideas and inspiration

Filled with positive thoughts

Filled with good energy

Have strength

Have confidence

Increased courage and willingness to rehabilitate

Hope and will of life

Have motivation and vitality in life

Improve mental and physical health

well-being life

Recovery of family relationships

Have a healthy social life and interpersonal

relationships

Get a new job or career

Challenges and accomplishments for wanted life

Move to action

Overcome adversity and difficulties

Live a thankful life

To live an altruistic, shared life

Subcategory

Acceptance of reality

Discover and reinterpret the

meaning of life

Promotion and growth of

self-awareness

Category

Willingness to change and choice

Creative thinking and inspiration

Filled with positive energy

Recharging

Recovery of physical and mental

health

Relational recovery

Active and self-directed life

Change

Changes in attitudes and values in

life

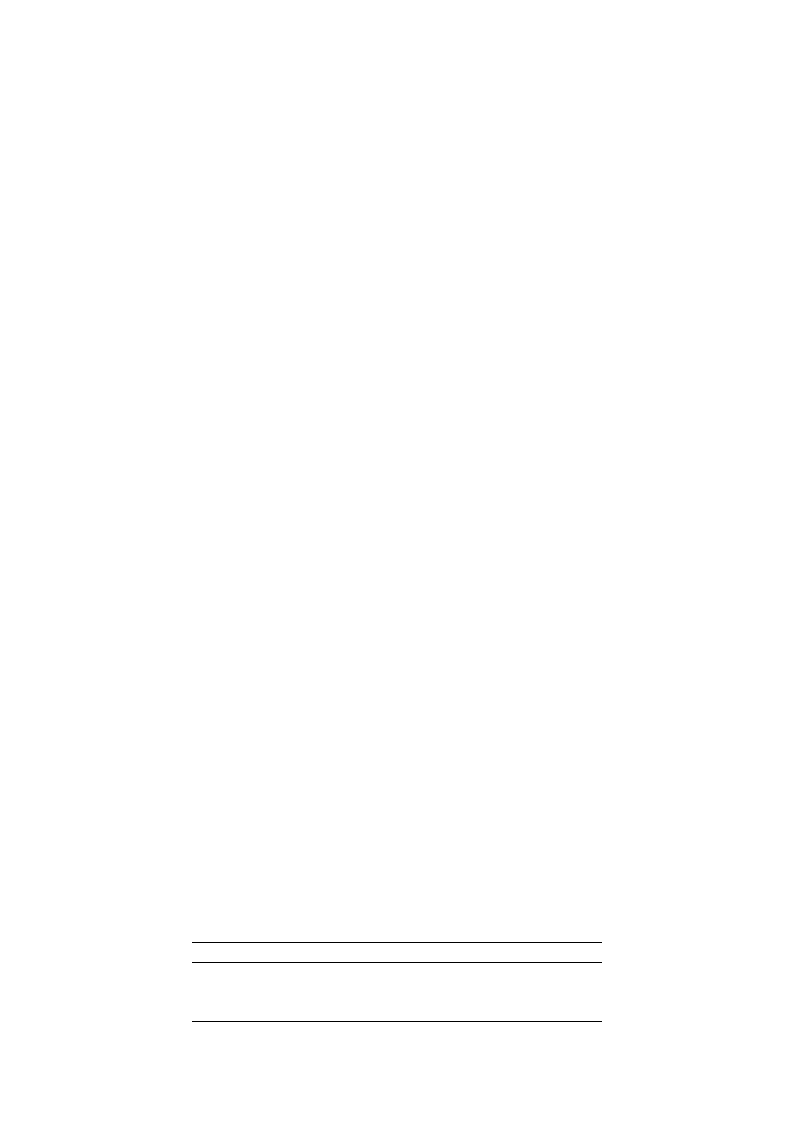

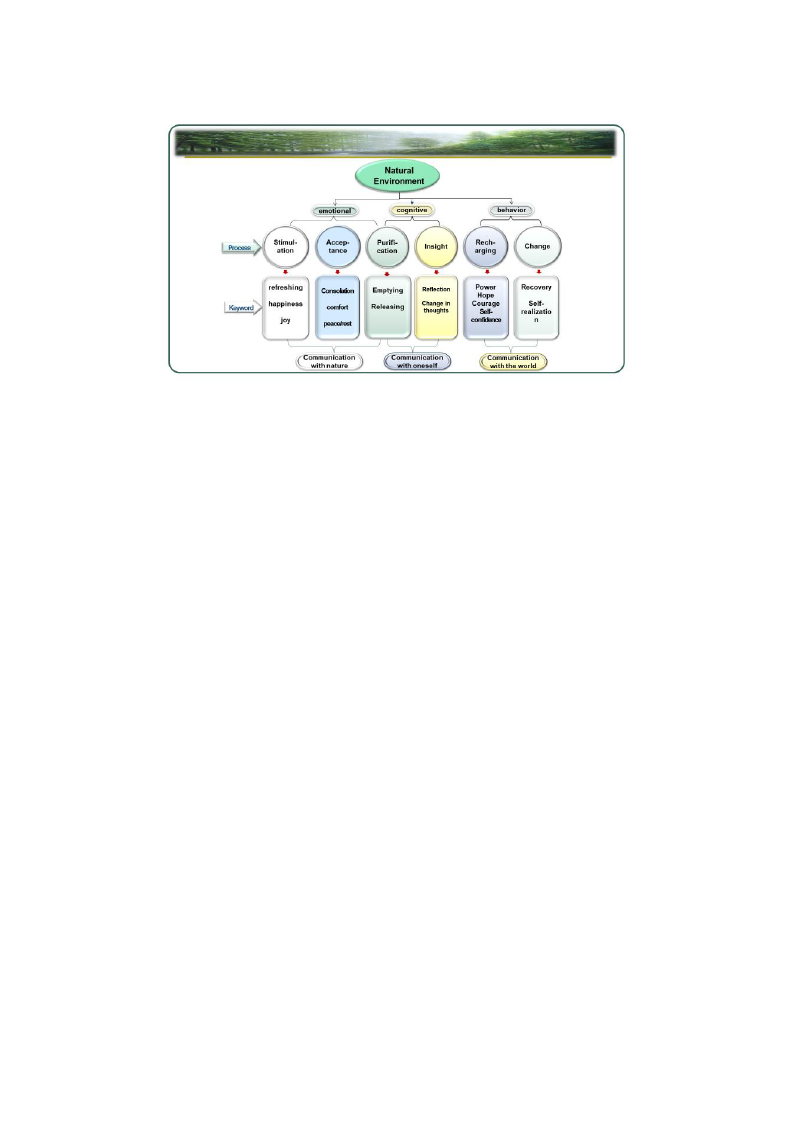

3.4. Nature-Based Therapy Process

The nature-based therapy process is a systematic connection of healing phenomena in the

natural environment. In this study, the nature-based therapy process was developed by analyzing

the progress of healing according to time among the content described by people who experienced

nature-based therapy. It was found that the nature-based therapy process was composed of six

categories: Stimulation, acceptance, purification, insight, recharging, and change. Based on these

results, a comprehensive six-step model of the nature-based therapy process was developed (Figure 1).

natural environment. In this study, the nature-based therapy process was developed by analyzing

the progress of healing according to time among the content described by people who experienced

nature-based therapy. It was found that the nature-based therapy process was composed of six

categories: Stimulation, acceptance, purification, insight, recharging, and change. Based on these

rInets.uJ.lEtsn,vairocno. mReps.rPeuhbelinc Hsievaleths2ix02-0s,t1e7p, 6m85odel of the nature-based therapy process was developed (Fi8goufr1e6

1).

Figure 1. Six-Step Model of Nature-Based Therapy Process.

3.4.1. Stimulation

On visiting the forest, participants felt better and refreshed by five sensory effects of the forest.

They also experienced emotions such as happiness, fascination, curiosity, and joy. Their senses and

sensibilities were recovered. Participants who had experienced such positive stimulation tended

to visit natural environments more actively and frequently. Therefore, the experience of positive

stimulation in the natural environment is an important starting point for healing and change. In the

stimulus stage, words related to positive emotions such as mood, beauty, refreshment, pleasure, joy,

and fascination appeared.

“Seeing the green trees, listening to the sounds of all kinds of birds and insects in my ears,

and falling into the imagination as if I was in heaven when faced with the cool wind blowing

from the forest.” (2015, alcoholism)

“I climbed the mountain and walked through the forest, and I liked the sounds of the wind

blowing. In particular, the sounds of the leaves striking and the sunlight shining between

the green forest felt so fresh and beautiful.” (2015, depression and stress)

“First, my ears were cleared by the birdsong. The bird sang deep enough to penetrate my

lungs through my ears and stimulate my mood. ” (2015, depression and stress)

“When I went to the forest, various fragrances, birdsongs, trees, and small pretty grass made

me happy. Fresh air enters my whole body and clears my mind ... At home, it was difficult to

breathe because of cancer cells, but in the forests, it was like magic because I could breathe

comfortably like using an oxygen respirator.” (2015, cancer patient)

3.4.2. Acceptance

In this stage, participants experienced receptive feelings in the forest, including the sense of

consolation and comportment. The forest is a place where participants could rest and relax at any

time. Participants felt that the forest accepted everything about them. They felt consolation and

comfort in the forest as if they were in their mother’s arms. Their tiring and exhausting lives were

relieved when they communicated emotionally with the nature. Their minds were opened. In the

acceptance stage, words such as friends, mother, comfort, relax, and hug gave emotional stability and

consolation appeared.

“As I walked along the forest, I felt as if I was at a party invited to happiness, and I felt

precious and special. ” (2015, alcoholism)

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

9 of 16

“Walking through the forest, I feel like I’m in my mother’s arms. The forest comforts the

tired and exhausted me and accepts my everything.” (2014, depression and stress)

“I told the forest of my troubles, greed, and many heartfelt stories. The forest listened to me

silently. The forest was my mother, my friend, my mentor, and myself.” (2014, stress)

“The oxygen and phytoncide of the forest became my friend and touched my tired and

painful body and mind ... Sometimes like a friend, sometimes as a mother who accepts

everything, it comforted me, saying, ‘okay, okay’.” (2015, patient)

“Holding a pine tree, which was my friend, seemed to make me lean and listen to my heart.

The forest seemed to comfort me every time I visited.” (2015, cancer patient)

3.4.3. Purification

In the purification stage, participants overcame and dissolved their negative feelings. They vented

and released their negative energy in a quiet forest. Their minds and emotions were then lightened

and cleansed. This led them to experience relief from stress. Their pain and anger then disappeared.

They also forget worries while they walked through the forest. They could honestly recognize their

own feelings of avoidance in the tranquil forest alone. They confided stories from their heart that they

usually could not tell others. They communicated with nature, emptying and washing away their

mind and emotions. They became relaxed and generous so they could afford to look back and reflect

on themselves. Purification is an important mediator that can lead to insight. Words used frequently at

this stage were release, dissolve, tear, disappear, and forget.

“My mind was generous when I came down from the mountain and everything was forgiven”

(2015, alcoholism)

“When I climbed a steep mountain road . . . all my worries disappeared and I felt refreshed.

When I climbed the mountain, my thoughts were cleared up and my head felt lighter.” (2015,

depression and stress)

“I have told the forest my worries, greed, and inner feelings . . . I drop the manager’s title

and the dream of promotion; I started emptying everything one-by-one ... and after a year

and a half, I started to feel comfortable.” (2014, stress)

“As I visited the forest every day, my mind began to empty. Greed, hatred, and resentment

in my heart disappeared ... As I walked through the forest, my resentment for the doctor

disappeared and was forgiven.” (2015, cancer patient)

“Drinking the clear night air in the forest, my body was feeling completely clean. Surprisingly,

it seemed that the disease of heart that weighed me heavily was disappearing in the forest.

The forest fairies seemed to blow the stress away. When I was in the forest, I forgot my

anxiety, my worries disappeared, and my stress disappeared.” (2015, mental illness)

3.4.4. Insight

Insight is the most important and meaningful stage in the nature-based therapy process.

Participants experienced awakening through self-reflection and meditation in nature. They then

communicated with themselves and talked with their inner self. They knew what they really wanted.

They found a new way of life. They regained their identity. They also discovered the meaning and

purpose of their life and reinterpreted the meaning of their pain. The most important phenomenon

at this stage was “change of thought”. “Change of thought” is a core phenomenon of nature-based

therapy. Participants could make a choice for new life through “change of thought.” Factors that could

promote insight in nature are survival methods of animals and plants, strong vitality, and the order of

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

10 of 16

nature. Frequently used words at this stage were thinking, reflection, enlightening, finding a dream,

and understanding.

“It was alcohol that destroyed my family, and it was alcohol that was dropped me in

depression and despair. I started to think about how to live well. If I had to give up and go

as I expected, my remaining life was so pitiful and unfair.” (2015, alcoholism)

“While walking through the forest, I could talk to myself . . . I thought my life was the way I

had to climb up myself ... Rather than waiting for someone to change me, I thought I had to

change myself. While those thoughts filled my mind, I wanted to study. It’s still a difficult

family environment, but in the end I felt that I had to change. I wanted to achieve the results

myself.” (2015, depression and stress)

“Communicating with the forest, I realized that all my conflicts and worries came from vain

greed ... The forest was a mentor to me.” (2014, stress)

“I enjoyed thinking naturally as I walked through the forest. As a result, I began to realize

precious things. It was my family and the dream of my youth.” (2015, stress)

“The old trees, the stones worn out over time, the grass that knows when they were bloomed

became my teacher ... I realized that the mind should be healed first, not the body. I gained

wisdom from many of the teachers in the forest.” (2015, cancer patient)

3.4.5. Recharging

The fifth stage is recharging. It fills participants with positive energy such as hope, courage,

and confidence. Recharging involves both psychological and physiological aspects. In the natural

environment, participants developed the will and desire for life. Hope, courage, confidence, and

positive thoughts became energy that could overcome difficulty and create a new life. Recharged with

positive energy, participants could go back into the world they were once afraid of and avoided. Words

often used at this stage were power, hope, energy, courage confidence, positive, vigor, and vitality.

“Before that, I struggled with guilt for my family, I was filled with the courage and willingness

to start again” (2015, alcoholism)

“The time to stay in the mountains has increased. As I grew in strength, I grew a confident

and gradually began to think positively. The mountain gave me a good energy . . . I certainly

felt as I was going up the mountain and my lack was filling up and my mind was refreshing

. . . The good feelings and positive energy I felt as I climbed the mountain changed me.”

(2015, depression and stress)

“As I started to go to the mountains, many negative thoughts disappeared and positive

thoughts were filled. I felt good thoughts springing up like fountains.” (2014, stress)

“I didn’t want to do anything and it was painful ... As this thought diminished, I began to

desire to do something ... When I come to the mountain, my desire for life springs up.” (2015,

cancer patient)

3.4.6. Change

The last stage is change. In this stage, participants recovered and changes occurred mentally

and physically. Participants could now live a life with changes such as relationship restoration,

re-employment, advancement, new challenges, and accomplishments. In addition, the value of

life could be changed. They described having a more positive attitude, leading to a satisfying life.

These changes ultimately led to self-realization. They described this life as rebirth, reproduction, and

rejuvenation. Words that appeared frequently at this stage were improvement, happiness, health,

healing, treatment, recovery, love, lightening, and positive.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

11 of 16

“Since then, I have not drunken alcohol at all. Of course, there are days when I want to

drink alcohol depending on my mood, but I did not even go to the supermarket to escape

the temptation. For me, the best prescription was to go to a mountain where cool oxygen is

emitted.” (2015, alcoholism)

“And time went by and I took a second SAT. I just want to achieve what I want to do. There

was only one thing and I passed one of the colleges I wanted. At the end of the challenge I

started to get out of the dark tunnel, I achieved what I wanted to do. My personality has

become much more cheerful since then, and I have the courage and mental power to boldly

challenge and overcome hard work. And I’m walking hard on my way to my dream. It was

unimaginable before.” (2015, depression and stress)

“For me, forests have given me psychological stability, peace of mind, and health that I can’t

get anywhere else in the world. Forests gave me a great life affordability and happiness that

I can’t get or feel in gold.” (2014, stress)

“My depression and popular avoidance were cured by 90%. Even without the psychiatric

treatment ... 3–4 days in the mountains are so happy that the rest of the day has no time to

depress.” (2014, depression)

“Now I am happy every day. The ordinary daily life is special, and every day is coming up

anew.” (2014, stress)

“I became more humble. I am generous with people and things and feel grateful for the little

things.” (2014, depression and stress)

4. Discussion

4.1. Emotional, Cognitive, and Behavioral Change Process

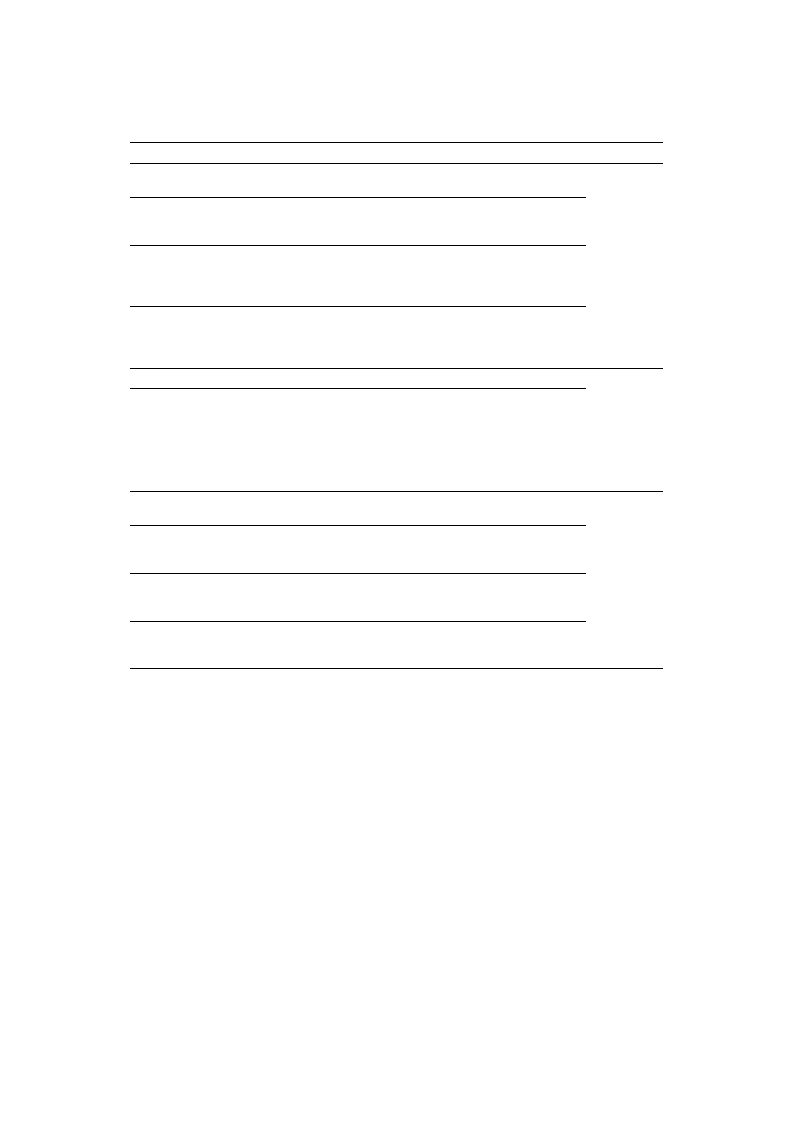

This study found that nature-based therapy process had six categories: Stimulation, acceptance,

purification, insight, recharging, and change. These six steps of nature-based therapy could be

categorized into three aspects: Emotional change, cognitive change, and behavioral change (Table 3).

Table 3. Example case of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral change processes.

Categories

Emotional

Cognitive

Behavior

Description

“I climbed the mountain and walked through the forest, and I liked the sounds of

the wind blowing. In particular, the sounds of the leaves striking and the sunlight

shining between the green forest felt so fresh and beautiful ... My worries

disappeared and I felt refreshed. The feeling was so good.”

“When I climbed the mountain, my thoughts were cleared up and my head felt

lighter... I gradually got positive thoughts ... In the mountains I could talk with

myself alone ... I thought I should change myself rather than waiting for someone

to change me ... As those thoughts filled my mind, I wanted to study ... It’s still a

difficult family environment, but I thought that I should change. I wanted to get

results through hard work ...”

“The good feelings and positive energy I felt as I climbed the mountain changed me

... And time went by and I took a second SAT.... I passed one of the colleges I

wanted. It was so lonely and hard days, but I did not give up and overcome it. At

the end of the challenge I started to get out of the dark tunnel, I achieved what I

wanted to do. My personality has become much more cheerful since then, and I

have the courage and mental power to boldly challenge and overcome hard work.

And now I’m walking hard on my way to my dream. It was unimaginable before.”

In the psycho-evolution theory (PET), Ulrich et al. [8] have emphasized that the natural recovery

effect is associated with a shift to a more positive emotional state. Kaplan & Kaplan [9] have recognized

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

12 of 16

four stages (clearing thoughts from the mind, regaining focus and attention, reducing distractions from

the mind while paying attention to thoughts in silence, and setting priorities, possibilities, actions,

and goals in life including reflection on one’s life) of the natural recovery experience in the attention

restoration theory (ART) and emphasized aspects of attention recovery. Although results of this study

seemed to differ from these previous theories, they could be considered as essentially an integration of

the two previous theories. This study confirmed that recovery in the natural environment progressed

through continuous interactions of emotional and cognitive changes.

The first change that participants experienced in the natural environment was a shift from negative

to positive emotions. Negative emotions such as tension, anxiety, and anger were reduced while

positive emotions were increased. These findings are consistent with studies showing that positive

emotion is the first to appear when humans encounter a natural environment [34]. They are also

consistent with previous findings showing that when humans are in a natural environment, negative

emotions will decrease while positive emotions will increase [13,17,20,27,35–38].

Next, participants’ experiences in the natural environment evolved into cognitive changes.

Participants changed into having positive emotions in the natural environment. Then, they began

to reflect on themselves in a more relaxed and stable state. They changed their perspectives about

themselves and their problems while they were in the nature. They moved on to the next stage of

planning and preparing for the future.

The reason for cognitive changes in the natural environment is related to positive emotions.

Positive emotions can help individuals relax psychologically and restore resources depleted by

stress [39]. Positive emotions can also promote thinking and creativity to help solve daily life problems

more flexibly [40]. The cognitive changes in this study are consistent with previous studies showing

that the natural environment can improve one’s ability to solve daily life problems and self-regulation

by reducing fatigue and improving efficiency [22,41,42]

Sonntag-Öström [43] has reported that when his patients can relax in the forest and find peace of

mind, they can reflect on their feelings and lives, leading to ambitions to change circumstances of their

lives. Such result shows that ‘positive emotions’ and ‘peace of mind’ in the natural environment can

bring about ‘reflection’ and ‘will for change in life’, consistent with results of the present study.

The third change that participants experienced in the natural environment was their behavioral

change. Those who had experienced emotional and cognitive changes were found to be healthier in

body and mind than they were before. They lived healthy and happy lives with positive attitudes

and behaviors. In other words, positive emotional experiences in the natural environment promoted

changes in thinking and cognitive systems. Cognitive changes then brought about changes in behavior.

Most participants had stress along with various mental and physical diseases. Their emotional and

cognitive changes caused their body and mind to interact with each other, resulting in recovery and

leading to restorations of interpersonal relationships and social life.

4.2. Psychological Mechanisms and Nature-Based Therapy Factors

Psychological mechanisms that cause emotional and cognitive changes in the nature-based therapy

process are as follows. Sense of beauty, wonder, and freshness in the natural environment could

provide psychological and emotional stimulation, evoking positive emotions and awe. Participants

were immersed in various charms of the nature. They built emotional rapport with various creatures

of nature. As they experienced a sense of unity with nature, their negative emotions such as rage and

anxiety disappeared. When they were deeply immersed in nature, they went one step further and

had a chance to reflect on themselves. Deep communication with nature took participants deeper

into themselves. At this time, they could fully focus on themselves and look into their feelings and

thoughts (i.e., communicate with themselves). By communicating with themselves, participants could

realize the cause of their problem and decide to change. Such experience occurred mainly through

reflection in silence when they were alone in the nature.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

13 of 16

Factors triggering emotional changes in their interactions with nature were found to result

from stimulation of five main senses coming from forest, such as pleasant smell, landscape, beauty,

and fresh air. Factors that could promote cognitive changes were various elements of the nature,

such as the natural order, the survival and robustness of animals and plants, and plants rooting and

surviving in a harsh environment. Participants reflected on themselves as they observed animals,

plants, and insects that exerted their utmost in a given environment, seeing trees grow their leaves,

watching flowers blooming according to the time and season, and observing grass and trees surviving

the cold. In addition, they develop a new perception of the situation and themselves, away from

negative perspectives of their reality.

Another important element in this reflection process was that participants could discover the

meaning and purpose of their life through their observations of the nature. Many participants, unable

to find meaning in their hopeless lives, had the feeling of frustration and depression, addiction,

and suicide attempts. However, they found their new meanings for life in the natural environment.

Participants began to accept their negative and destroyed situations and self-image through their

observations of trees managing to grow in a harsh environment. They saw creatures conforming to

the order of nature and accepted their own painful reality. Seeing various creatures in nature finding

their own ways of survival and living, people came to accept their own values. Their self-esteem

was recovered. Their helpless body and mind were recovered through their changes of perspectives

even in difficult circumstances. Psychological changes led to physical changes because body, mind,

and emotion acted as an one system. Improved body and mind brought hope and confidence for

new life, leading to better mental and physical improvements. As a result, participants who had

experienced natural recovery effects described in their essays that they were living healthier and

happier than before.

At this time, the initiator and driver of such changes were oneself, indicating that their mind and

body were recovered through reflection on their own. In this regard, the natural environment can be a

place that provides a transcendence to overcome difficulties of reality and a place of “self-therapy” that

promotes finding the cause of the problem and resolving the issue by oneself.

4.3. Comprehensive Analysis of the Nature-Based Therapy Process

A comprehensive finding of this study was that the nature-based therapy process proceeded with

a very complex and multidimensional mechanism, in which the body, mind, and emotional cognitive

behaviors interacted with the nature (Table 4). Results of this study are summarized as follows.

• The nature-based therapy process consisted of six categories.

• The six-step process proceeded through emotional, cognitive, and behavioral changes.

• The psychological mechanism for nature-based therapy consisted of “communication with

nature”, “communication with oneself”, and “communication with the world”. In other words,

“communication with nature” could promote participants’ changes into positive emotions while

“communication with oneself” could trigger cognitive changes. Participants who had experienced

emotional and cognitive changes in the natural environment changed to lead a life with more

intensive and healthy “communication with the world” in terms of daily activities, social lives,

and interpersonal relationships.

The results of this study are consistent with Wilson’s “biophilia” hypothesis [10]. In addition,

the six-step model of the nature-based therapy process presented in this study supports Ulrich’s PET

theory [8] emphasizing positive emotions in nature and Kaplan’s ART theory [9] emphasizing aspects

of attention recovery. Results of this study can also be considered to be an integrated linkage of many

previous studies on the theory of human recovery in nature.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

14 of 16

Table 4. Comprehensive analysis of nature-based therapy mechanisms.

Phase

Stimulation

Acceptance

Purification

Insight

Recharging

Changing

Phenomenon

Interaction

Mechanism

Positive stimulation survives

feelings and emotions

Experience receptive feelings

from the forest

Open mind/comfort/stable

Eruption and resolution of

negative emotion

Awareness and reflection

Filled with positive energy

Healing and recovery

Healthy and happy life

Emotional change

Cognitive change

Behavioral change

Communication

with nature

Communication

with oneself

Communication

with the world

Psychological

Physiological

Changes

Recovery through

mind and body

interaction

5. Conclusions

The nature-based therapy process is composed of six stages: Stimulation stage, acceptance stage,

purification stage, insight stage, recharging stage, and change stage. The nature-based therapy process

does not comprise a single element or step. Instead, it is an integrated way of healing through emotional

and cognitive changes. In other words, in the nature-based therapy process, self-healing progresses as

the mind and body interact with various elements of the nature. Natural environments are not only

healing places where physical symptoms and psychological problems are healed, but also healing

places where holistic healing, including oneself and others as well as social and relational recovery,

can take place. In addition, natural environment, such as a forest, can serve as a place that provides a

transcendence to overcome difficulties of reality and a place of “self-therapy” that can help one find

the cause of the problem and resolve the issue by oneself.

This study was significant in that it derived a theoretical model of the nature-based therapy

process and mechanisms. It was also meaningful in that it explored changed lives and long-term

effects of participants after experiencing natural recovery. However, it has limitations in generalization

since this study is based on self-reported “forest therapy experiences”. Further research is needed

to establish a more systematic theoretical model through the development of nature-based therapy

programs based on results of this study and structured interviews.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, K.H.O.,W.S.S., and D.J.K.; methodology, K.H.O., W.S.S. and D.J.K.;

validation, W.S.S. and D.J.K.; formal analysis, K.H.O. and T.G.K.; investigation, K.H.O. and T.G.K.; resources,

K.H.O.; data curation, K.H.O. and T.G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H.O.; writing—and editing,

K.H.O.; review, W.S.S. and D.J.K.; visualization, K.H.O.; supervision, W.S.S. and D.J.K.; project administration,

W.S.S. and D.J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984.

2. Selye, H. The Stress of Life; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1956.

3. McEwen, B.S. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol. Rev.

2007, 87, 873–904. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. Selye, H. Confusion and controversy in the stress field. J. Hum. Stress 1975, 1, 37–44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

5. Hockey, R. Stress and the Cognitive Component of Skilled Performance. In Human Stress and Cognition:

An Information Processing Approach; Hamilton, V., Warburton, D.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK,

1979; pp. 141–177.

6. Bell, J.M. Stressful life events and coping method in mental illness and illness behavior. Nurs. Res. 1977, 26,

136–141. [CrossRef]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

15 of 16

7. Korte, S.M.; Koolhaas, J.M.; Wingfield, J.C.; McEwen, B.S. The Darwinian concept of stress: Benefits of

allostasis and costs of allostatic load and the trade-offs in health and disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005,

29, 3–38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

8. Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to

natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [CrossRef]

9. Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Oxford University Press: New York,

NY, USA, 1989.

10. Wilson, E.O. Biophilia and Conservation Ethic. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, S.R., Wilson, E.O., Eds.;

Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 31–41.

11. Beery, T.; Jönsson, K.I.; Elmberg, J. From environmental connectedness to sustainable futures: Topophilia

and human affiliation with nature. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8837–8854. [CrossRef]

12. Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421.

[CrossRef]

13. Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field

settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [CrossRef]

14. Shin, W.S. The influence of forest view through a window on job satisfaction and job stress. Scand. J. Res.

2007, 22, 248–253. [CrossRef]

15. Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku

(taking in the forest atomosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across

Japan. Environ. Health. Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [CrossRef]

16. Li, Q. Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 9–17.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

17. Morita, E.; Fukada, S.; Nagana, J.; Hamajima, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwai, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Ohira, H.;

Shirakwa, T. Psychological Effects of Forest Environments on Healthy Adults: Shinrin-yoku (Forest-air

Bathing, Walking) as possible Method of Stress Reduction. Public Health 2007, 121, 54–63. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

18. Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T. The influence of urban green

environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 1–9. [CrossRef]

19. Hansmann, R.; Hug, S.M.; Seeland, K. Restoration and stress relief through physical activities in forests and

parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 213–225. [CrossRef]

20. Pretty, J.; Peacock, J.; Hine, R.; Sellens, M.; South, N.; Griffin, M. Green exercise in the UK countryside: Effects

on health and psychological well-being, and implications for policy and planning. J. Environ. Plan. Manag.

2007, 50, 211–231. [CrossRef]

21. Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Aggression and violence in the inner city effects of environment via mental fatigue.

Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 543–571. [CrossRef]

22. Kuo, F.E. Coping with poverty impacts of environment and attention in the inner city. Environ. Behav. 2001,

33, 5–34. [CrossRef]

23. Wells, N.M. At home with nature effects of greenness on children’s cognitive functioning. Environ. Behav.

2000, 32, 775–795. [CrossRef]

24. Kamitsis, I.; Francis, A.J. Spirituality mediates the relationship between engagement with nature and

psychological wellbeing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 136–143. [CrossRef]

25. Williams, K.; Harvey, D. Transcendent experience in forest environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 249–260.

[CrossRef]

26. MacKerron, G.; Mourato, S. Happiness is greater in natural environments. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23,

992–1000. [CrossRef]

27. Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G. Psychological restoration in nature as a source of motivation forecalogical behavior.

Environ. Conserv. 2007, 34, 291–299. [CrossRef]

28. Thompson, C.W.; Roe, J.; Aspinall, P.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A.; Miller, D. More green space is linked to less

stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Lands. Urban Plan. 2012, 105,

221–229. [CrossRef]

29. Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.A. Landscape planning and stress. Urban For. Urben Green 2003, 2, 1–18. [CrossRef]

30. Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space

andstress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [CrossRef]

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 685

16 of 16

31. Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Vries, S.D.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health:

How strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [CrossRef]

32. Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: An observational

population study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1655–1660. [CrossRef]

33. Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory,

2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998.

34. Zajonc, R.B. Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. Am. Psychol 1980, 35, 151–175. [CrossRef]

35. Ulrich, R.S. Human Responses to Vegetation and Landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1986, 13, 29–44. [CrossRef]

36. Tsunetsugu, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Tyrväinen, L.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological

effects of viewing urban forest landscapes assessed by multiple measurements. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013,

113, 90–93. [CrossRef]

37. Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Igarashi, M.; Miwa, M.; Takagaki, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological

responses of young males during spring-time walks in urban parks. J. Physiol. Anthr. 2014, 33, 8. [CrossRef]

38. Curtin, S. Wildlife tourism: The intangible, psychological benefits of human–wildlife encounters. Curr. Issues

Tour. 2009, 12, 451–474. [CrossRef]

39. Lazarus, R.S. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

40. Moskowitz, J.T. Emotion and Coping. In Emotions: Current Issues and Future Directions; Mayne, T.J.,

Bonanno, G.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001.

41. Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.; Bruehlman-Senecal, E.; Dolliver, K. Why is nature Beneficial?: The Role of

Connectedness to Nature. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 607–643. [CrossRef]

42. Kopela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, P.G.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative experience and self-regulation in favorite places.

Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 572–589. [CrossRef]

43. Sonntag-Öström, E.; Stenlund, T.; Nordin, M.; Lundell, Y.; Ahlgren, C. Nature’s effect on my mind:

patients’qualitative experiences of a forest-based rehabilitation programme. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015,

14, 607–614. [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access

article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution

(CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).